-

Aquatic ecosystem health is crucial to public health safety and proper ecosystem function. However, this health is increasingly threatened by a variety of biocontaminants in water bodies, such as pathogenic microorganisms[1], parasites[2], algal bloom-associated toxins[3], and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs)[4]. These biocontaminants can directly cause waterborne disease outbreaks[5] and disrupt aquatic biodiversity, leading to persistent ecological and health risks. Unlike persistent chemical pollutants, biocontaminants are not static; they are biologically active and capable of proliferation, evolution, and dissemination. Consequently, their behavior is governed by temperature, nutrient levels, and hydrological conditions[6]. For instance, ARGs can spread among bacterial populations via horizontal gene transfer (HGT)[7]. This process continuously reshapes the environmental resistome, thereby increasing pollution unpredictability and complicating long-term control efforts[8].

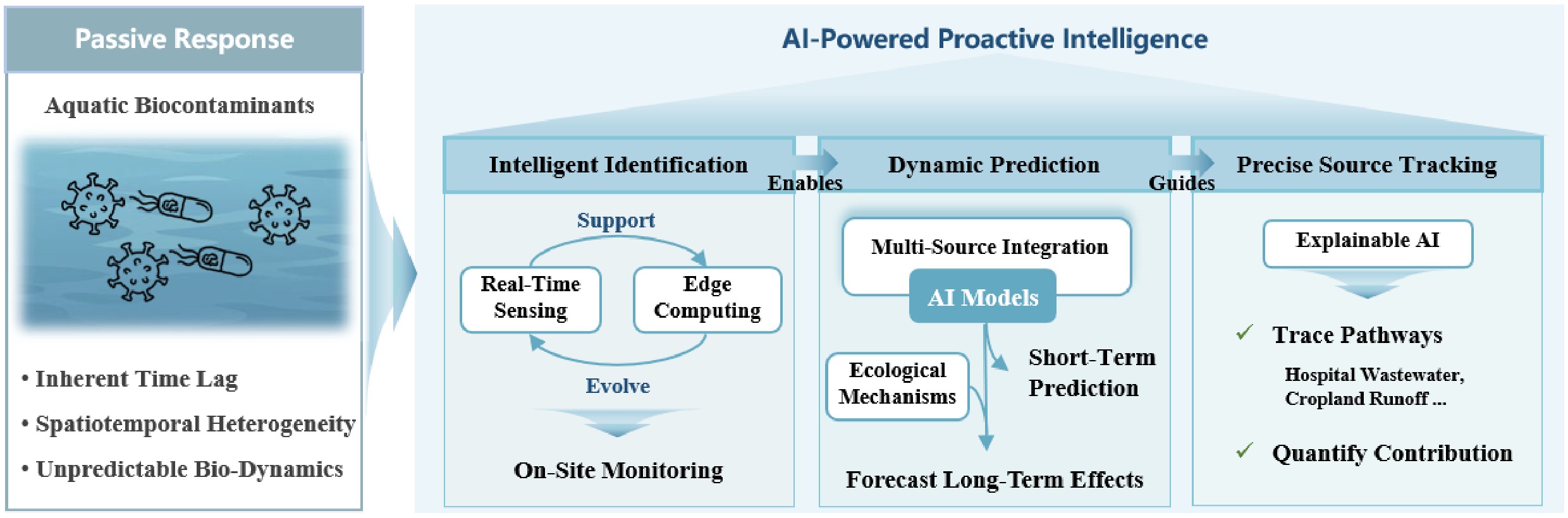

Conventional approaches, which rely on static, lagging technical methods, struggle to cope with the dynamic nature of biocontaminants. Specifically, these approaches cannot achieve real-time perception, enable nonlinear prediction, and perform precise source tracking[9]. In contrast, artificial intelligence (AI), with its powerful capabilities in pattern recognition, complex nonlinear fitting, and multi-source heterogeneous data fusion, is positioned to address this systemic challenge, and is driving a paradigm shift from passive response to proactive intelligence[10]. As Fig. 1 illustrates, AI empowers the entire management chain. For instance, during identification, the synergy of intelligent sensing and edge computing enables on-site, real-time monitoring[11]. For prediction, models that integrate multi-source data can provide dynamic early warnings of events such as algal blooms[12]. In the domain of source tracking, explainable AI (XAI) helps quantify pollution source contributions and clarify transmission pathways[13].

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration contrasting the traditional passive response paradigm (left) with the artificial intelligence (AI)-driven proactive intelligence framework (right) for managing biocontaminants in water environments. The passive approach is characterized by static identification with lagged detection and low sensitivity, prediction reliant on linear assumptions resulting in ineffective warnings, and traceability limited to qualitative inferences and snapshot analyses. In contrast, the AI-driven paradigm integrates intelligent identification using multi-source data (e.g., environmental DNA, water quality, and meteorological parameters) for real-time, high-accuracy monitoring; dynamic prediction models for early warning and multi-scale forecasting; and accurate traceability through mechanistic analysis and quantitative apportionment. This visual emphasizes the shift from disjointed, reactive methods to an integrated, data-driven system that enhances precision and responsiveness in pollution control.

Against this backdrop, this review synthesizes and critically evaluates the latest advances in AI-driven management of aquatic biocontaminants. Structured around the core workflow of intelligent identification, dynamic prediction, and precise source tracking, it provides an in-depth analysis of how AI promotes technological innovations at each stage, along with a discussion of current challenges and prospects. The primary aim of this study is to provide a framework and conceptual basis for developing an intelligent, proactive risk management system for aquatic environments.

-

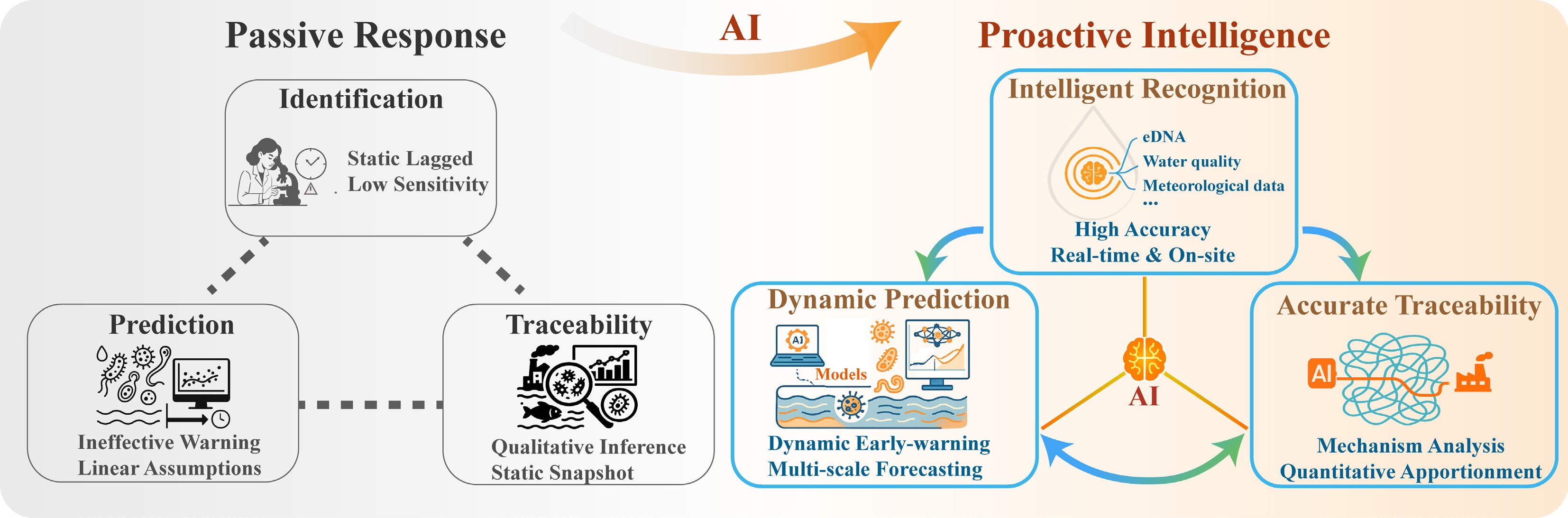

As the foundational, critical first step in building an intelligent management system for aquatic biocontaminants, accurate identification lays the groundwork for all subsequent processes. As shown in Fig. 2, it examines how AI systematically improves the timeliness, accuracy, and robustness of identification. These advances focus on three key areas: sensing innovation, algorithmic analysis, and generalization enhancement. The technological evolution is no longer limited to the optimization of a single algorithm, but has shifted to a complete system that spans data acquisition, feature learning, and scene adaptation.

Figure 2.

Architectural framework of an AI-integrated intelligent perception and decision-making system for water environment management, depicted as a house-like structure to symbolize a holistic and stable infrastructure. The system features a hierarchical design with a central AI core that manages a closed loop of perception, decision-making, and automated response. This architecture is designed to ensure real-time interactivity and adaptive control. The middle layer integrates advanced machine learning approaches, including few-shot learning, to address data scarcity, and a diverse suite of models spanning deep learning and traditional algorithms for robust analysis. The base level illustrates the acquisition of multimodal data from intelligent sensing networks and edge computing devices, enabling capabilities such as real-time monitoring, on-site analysis, system integration, and autonomous operation. This visual underscores how AI synergizes data, models, and actions to evolve the biocontaminants management framework towards a dynamic, end-to-end intelligent system.

On-site rapid monitoring enabled by synergistic intelligent sensing and edge computing

-

A core bottleneck in conventional monitoring of aquatic biocontaminants lies in the lag between data acquisition and analysis. AI is driving a fundamental shift in monitoring paradigms to address this challenge. The key to this transformation is a fully integrated system that combines intelligent sensing with edge computing, enabling the shift from lagging analysis to real-time sensing and decision-making.

The primary breakthrough of this paradigm is the integration of intelligence at the sensing front-end. By embedding specific machine learning (ML) models into sensor hardware, these devices evolve from passive data collectors to intelligent terminals that can perform in-situ identification and preliminary judgment[14,15]. For instance, sensors based on the fluorescence characteristics of tryptophan (an amino acid) can incorporate classification models to transition from simple threshold-based alarming to intelligent multi-level risk discrimination[16]. Similarly, integrating surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) with deep learning (DL) empowers low-cost paper-based chip platforms to accurately identify multiple pathogens (≥ 98.6%) without complex pretreatment[17,18]. The core innovation of these technologies lies in the deep fusion of AI algorithms with the sensing hardware, which are no longer just backend analysis tools. Through the co-optimization of hardware design and recognition algorithms, they achieve a leap from mere signal acquisition to intelligent on-site diagnosis[19]. This dramatically compresses the spatiotemporal delay from sensing to cognition by shifting data analysis to the monitoring site[20]. Nevertheless, the performance and generalization capability of these intelligent sensors depend on the quality and quantity of the training data, posing a risk of false results when faced with novel contaminants or complex background interference[21].

Building on intelligent sensing, the challenge then becomes processing the resulting data streams promptly. Edge computing presents a promising solution by deploying lightweight AI models on field computing nodes (e.g., edge gateways) located close to the sensors[22,23]. Given the constraints on computational power, energy consumption, and bandwidth of field-deployed devices, model lightweighting and efficient deployment are essential[22,24,25]. For example, a lightweight deep neural network specifically designed for algae identification (e.g., an algal monitoring deep neural network) can be integrated with low-cost edge AI chips to achieve real-time, online classification of 25 harmful algal bloom species with an accuracy of up to 99.87%[26]. Similarly, a deeply compressed object detection model for algae based on the You Only Look Once (YOLO) architecture, known as MobileYOLO-Cyano, achieves high accuracy while reducing computational resource consumption by 50%, enabling response times within seconds[11]. This integrated edge computing approach provides significant system-level benefits. By coupling the Internet of Things with edge computing, it substantially reduces data transmission latency and bandwidth usage[24], supporting instant decision-making in resource-limited environments. However, model compression and lightweighting improve efficiency at the cost of a precision-robustness trade-off, which must be carefully balanced against performance requirements[27].

Ultimately, the deep integration of intelligent sensing and edge computing has facilitated an on-site intelligent closed-loop system that unifies perception, decision-making, and response. By seamlessly connecting smart sensing, local computing, and automated control, these systems significantly reduce reliance on external networks and manual intervention. For instance, an AI-powered biosensing framework using a rapid object-detection model (faster region-based convolutional neural networks) allows for fully automated pathogen detection from sample input to final results[28]. Meanwhile, a cyber-physical system that integrates paper-based biosensors, edge computing, and a low-power wide-area network has enabled remote, real-time assessment and management of contaminants across extensive water bodies[25]. The high degree of automation in such integrated systems, while powerful, raises critical questions about accountability and the need for human oversight, especially in scenarios involving system errors or failures[29].

DL-based analysis of morphological and spectral features of biocontaminants

-

Accurate identification of biocontaminants in complex aquatic environments has long been constrained by several challenges, including their small size, morphological variability, interspecies feature similarity, and complex environmental conditions[30]. DL offers a systematic solution to these challenges through its powerful hierarchical feature extraction and pattern recognition capabilities. The technical pathway follows a clear hierarchical structure, starting with precise target localization and segmentation, progressing to fine-grained classification based on morphological and spectral features, and ultimately increasing decision confidence in complex scenarios through multimodal fusion.

Accurate localization and segmentation form the foundational step for subsequent analysis. Despite interference from complex aquatic backgrounds, DL-based object detection and instance segmentation models have demonstrated exceptional performance. For example, Tao et al.[11] developed the MobileYOLO-Cyano model, which integrated multi-scale convolutional modules and attention mechanisms to achieve high-precision recognition of subtle structural variations among filamentous cyanobacterial genera. Lightweight models explicitly developed for biocontaminant detection, such as an improved YOLOv8 algorithm[31], greatly increased detection efficiency and average precision for low-contrast targets by optimizing network structure to maintain low computational costs, thereby enabling embedded deployment[32]. While these models effectively solve the problem of target localization, their performance is intrinsically tied to the availability of high-quality, pixel-level annotated training data. The acquisition of such data remains costly and time-consuming, potentially limiting the models' broad application[33].

Based on precise localization, the main strength of DL lies in its ability to acquire highly discriminative features autonomously. This allows for robust classification of biocontaminants that are morphologically or spectrally similar[34]. Subtle interspecies or intergenerational differences are challenging to distinguish with traditional methods, whereas they can be effectively resolved using deep features extracted by deep convolutional networks. For instance, a platform integrating light-sheet microscopy and hyperspectral imaging, along with DL algorithms, has successfully classified fluorescence spectra from microalgal cells and their mixtures, with accuracy significantly outperforming that of conventional approaches[35]. Wang et al.[36] integrated the U-Net (a U-shaped convolutional network) architecture with an attention mechanism to enable high-precision analysis of Raman spectra, offering a potential solution for distinguishing different foodborne pathogens. These advances demonstrate that DL models not only accomplish target localization but also decode the discriminative biological information embedded within the data.

To further enhance discriminative confidence and stability in extremely complex scenarios, multimodal learning integrating multiple sources of information represents a significant solution. When uncertainty exists in single-modal data (e.g., images or spectra), the integration of complementary information can substantially enhance a model's decision-making capabilities. For instance, an algal identifier that combined convolutional neural network (CNN)-based image analysis with Artificial Neural Network (ANN) based physical parameter analysis can simultaneously examine micro-morphological features and physical parameters (e.g., particle size distribution). This significantly enhanced its ability to distinguish between challenging algal phyla, such as diatoms and dinoflagellates[37].

Enhancement strategies for identifying biocontaminants in low-abundance and few-shot scenarios

-

A key challenge in real-world aquatic biological monitoring is the long-tailed distribution characteristic of target contaminants. This refers to a situation in which data on common species are abundant, while data on rare species and low-abundance pathogens are scarce[38]. This data imbalance readily leads to overfitting and generalization failure in conventional data-driven models. To address these challenges, AI has developed systematic solutions spanning data augmentation, knowledge transfer, and innovations in model architecture.

At the data level, generative AI effectively bridges sample gaps by synthesizing highly realistic, diverse training data, directly mitigating data scarcity at the source[39]. For instance, Chan et al.[40] employed the StyleGAN2-ADA generative model to create synthetic algal images with high biological fidelity, which significantly increased the overall F1 score of a MobileNetV3 model for identifying 20 algal species from 88.4% to 96.2%. In spectral analysis, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) generate augmented samples through adversarial training, producing data that maintain structural and distributional consistency with original biological spectra, thereby significantly enhancing detection sensitivity[41]. For example, synthetic spectra generated by GANs increased classification accuracy for Influenza A virus from 83.5% to 91.5%[42]. In contrast, high-resolution spectral data generated by the Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty model improved classification accuracy for pathogenic bacteria to 99.3%[43]. These methods require the generated data to represent the full spectrum of natural target variations accurately. Otherwise, they risk amplifying biases and compromising real-world performance. When labeled data is limited, transfer learning offers an efficient indirect solution by reusing generalizable knowledge from pre-trained models. This strategy employs deep CNNs pre-trained on large-scale general datasets (e.g., ImageNet) as feature extractors. Through fine-tuning, the universal visual features learned by these networks, such as edges, textures, and shape patterns, are adapted for identifying biocontaminants in aquatic environments. For example, the CNN-Support Vector Machine (SVM) cascade model developed by Sonmez et al.[44] achieved 99.66% accuracy with limited annotated algal data. More advanced frameworks, such as Transformer-based deep transfer learning (based on the Transformer architecture known for its self-attention mechanism)[45], and cyclical fine-tuning transfer learning[46], further enable the perception of temporal dependencies in biological features and the adaptive transfer of cross-domain knowledge. Nevertheless, the efficacy of this approach depends on the relevance between the source domain (e.g., natural images) and the target domain (aquatic microorganisms). Excessive domain disparity can lead to limited benefits or even negative transfer, which degrades model performance.

Furthermore, self-supervised learning reduces reliance on manual annotation by autonomously learning feature representations from unlabeled data. This approach designs pretext tasks tailored to the characteristics of biocontaminants[47], enabling models to learn meaningful visual feature representations autonomously from large volumes of unlabeled aquatic microorganism images[48]. The learned general features provide a robust foundational representation for downstream few-shot identification tasks. In the field of biological network data analysis, self-supervised learning, through frameworks such as contrastive learning[49], offers a novel methodology for deciphering complex microbial community structures. It is important to note that while self-supervised learning reduces the need for annotations, it still requires substantial unlabeled data for pre-training, and the design of maximally practical pretext tasks remains an open research challenge.

At the model architecture level, targeted optimizations aim to maximize the efficiency of information extraction from sensing data while operating within the fundamental physical detection limits of the hardware. On the one hand, the core function of attention mechanisms is to weight the importance of different regions in the data, allowing the model to autonomously focus computational resources on subtle pathogen features while suppressing complex background noise. This significantly improved the detection capability for low-abundance targets[50]. On the other hand, when combined with ultra-high-sensitivity detection technologies such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), the algorithm's role evolves from a passive analyzer to an active interpreter. DL methods, particularly CNN, are trained to recognize the unique, amplified spectral fingerprints of pathogens and effectively filter out stochastic noise inherent in the physical sensing process. This synergy between algorithms and hardware enables the early identification of biocontaminants at extremely low concentrations[51].

In summary, AI is systematically advancing the real-time performance, accuracy, and adaptability to complex scenes in biocontaminant identification through intelligent sensing and edge computing synergy, DL-based feature analysis, generative enhancement, and transfer learning strategies. This marks a significant evolution from offline, manual operations toward online, automated intelligent detection (Table 1). The core progress lies in the preliminary establishment of a hierarchical technical framework addressing the challenges of real-time sensing, precise interpretation, and scenario adaptation. However, substantial challenges still remain, such as limited model generalization due to complex optical backgrounds and variable contaminant viability, compounded by inadequate capabilities for detecting low-abundance contaminants and for adaptively identifying emerging contaminants[52]. These challenges have shifted from the mere pursuit of algorithmic accuracy to higher demands for environmental robustness and evolutionary tracking in models.

Table 1. Landscape of AI-driven detection technologies for aquatic biocontaminants

Biocontaminants Detection category Data type AI model Key performance Timeliness Ref. Harmful algal bloom eDNA, remote sensing,

water quality parametersMultimodal (sequence, image, numerical) Gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) MAPE = 11.20% Laboratory [53] Water quality data Numerical/tabular Supervised ML Accuracy = 98.09% Real-time [54] Microscopy images Image CNN, CNN-SVM Accuracy = 99.66% Laboratory [44] Pathogens Optical sensors Spectral CNN Accuracy ≥ 95% Real-time [55] Signal/spectral Naive bayes (NB), decision tree (DT) Accuracy ≥ 95% Real-time [56] Image SVM, random forest (RF), ANN, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) Accuracy ≈ 99.9% Real-time [57] Fluorescence sensors Spectral K-nearest neighbors (KNN), principal component analysis (PCA) Accuracy = 100% Real-time [58] Raman spectroscopy Spectral CNN Accuracy = 98% Laboratory [59] Electrochemical aptasensor Numerical/tabular GAM, ridge, partial least squares (PLS), GBDT RMSE = 0.19 Real-time [60] Electrochemical sensors Numerical/tabular Multilayer perceptron (MLP), gradient boosting (GB), RF Accuracy = 97% Real-time [61] Parasites Microbial, water quality, meteorological parameters Multimodal RF, XGBoost Accuracy =

80.3% (Crypto),

82.6% (Giardia)Laboratory [62] Microscopy images Image YOLOv4 Accuracy = 100% Laboratory [63] Image DenseNet, ResNet Accuracy = 100% Laboratory [64] ARGs Metagenomics Sequence RF AUC ≈ 0.99 Laboratory [65] qPCR Numerical DT R2 = 0.87 Laboratory [66] -

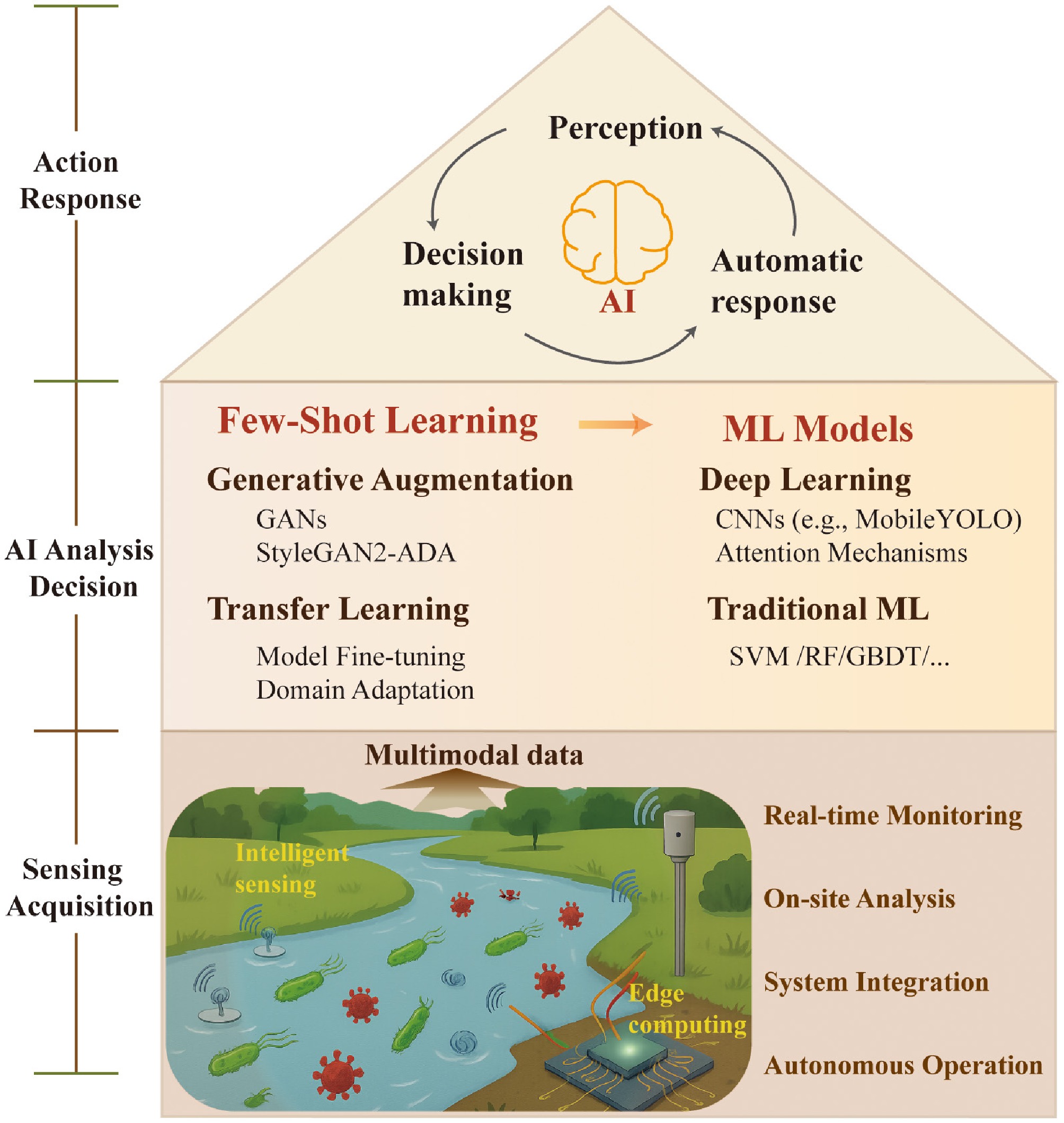

Building upon accurate identification, predicting the dynamic processes of biocontaminants is crucial for risk assessment and proactive intervention. While identification focuses on the current state, the core challenge of prediction is to describe the complex, nonlinear spatial and temporal evolution of biocontaminants in the context of environmental factors. This section summarizes key prediction models and methodologies, framing their applications into two interconnected dimensions: (1) short-term dynamic forecasting for emergent risks, to provide early-warning windows on hourly to daily scales for events such as algal blooms and pathogen outbreaks; and (2) long-term trend simulation for ecological management, focusing on the cumulative and delayed impacts of contaminants on ecosystem structure and function. This multi-scale perspective helps clarify the applicable scenarios and decision-making value of different AI models (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A conceptual framework illustrating the integration of core AI models with multi-scale forecasting applications for water biocontaminants. The left panel (Core AI Model) categorizes foundational algorithmic approaches into three synergistic pillars: temporal models (e.g., LSTM, GRU, Transformer) for capturing dynamic patterns; feature-driven analytics (e.g., XGBoost, GAM) for identifying key influencing factors; and mechanism integration (e.g., Kalman filter, microbial growth dynamics) for incorporating domain knowledge. The right panel (Forecast Application) demonstrates how these models are deployed across temporal scales. Short-term forecasting uses real-time sensor and meteorological data, along with pattern recognition models, to generate immediate outputs such as alerts and edge intelligence. Long-term forecasting leverages historical, eDNA, and remote sensing data through trend analysis and mechanism simulation to predict ecological thresholds and enable transdisciplinary risk assessment. The schematic underscores the critical role of selecting and integrating appropriate AI architectures to allow precise, scalable predictions from operational warnings to strategic planning.

Core prediction models and methodologies

-

To accurately predict the dynamic processes of biocontaminants in the water environment, the core challenge is to build a model that effectively quantifies the complex, nonlinear relationships between them and environmental factors. Traditional mechanism-based models, while grounded in physical principles, still face inherent limitations in quantifying many complex ecological processes. In contrast, early purely data-driven models were often constrained by interpretability and extrapolation capabilities. In recent years, AI has provided a suite of powerful modeling tools, offering new, effective pathways to bridge the gap and advance the prediction paradigm toward a deep integration of mechanisms and data. This evolution follows a clear methodological progression, moving from time-series forecasting to feature-driven modeling and finally to the integration of mechanistic principles. The goal of this progression is to develop next-generation models that combine predictive accuracy, physical plausibility, and robust generalization capability[12]. Table 2 summarizes the scope of prediction and the performance of AI models for different biological pollution events.

As the foundation for dynamic prediction, temporal prediction models mainly focus on the patterns of biocontaminant concentration evolution over time, including periodic fluctuations, long-term trends, and sudden changes. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their enhanced variants, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), have become essential tools for dealing with scenarios that have strong temporal correlation, such as short-term proliferation of algal blooms, due to their ability to capture dependencies within time series data[67] effectively. For instance, by integrating historical phytoplankton data with ocean current time series, LSTM models can accurately predict the accumulation of shellfish toxins[68]. When addressing longer-term temporal dependencies, the Transformer architecture, based on self-attention mechanisms, demonstrates distinct advantages by identifying cross-temporal influences of environmental parameters, such as total phosphorus, on algal growth[69]. A significant challenge for these temporal models, however, lies in their high sensitivity to missing data and noise in input sequences, compounded by their 'black-box' nature, which obscures the reasoning behind predictions and limits their credibility in critical decision-making.

While temporal models capture data evolution patterns, they offer limited insight into the key driving factors behind pollution events and the mechanisms of their interactions. Therefore, the prediction method gradually shifts to a feature-driven ML model. The core advantage of this model is to identify key features that affect the dynamics of contaminants from multidimensional environmental parameters and to quantify their contributions. Gradient boosting decision trees, such as XGBoost and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), employ ensemble learning strategies to deliver both high predictive accuracy and feature importance rankings, thereby revealing the relative influence of different environmental variables[70,71]. Meanwhile, Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) fit nonlinear relationships among variables using smooth functions, offering an interpretable framework for pollution risk analysis[72]. Despite enhancing understanding of pollution causation, these methods remain fundamentally based on statistical correlations and struggle to be reliable under extreme conditions or in unobserved scenarios, where physical mechanisms may dominate.

To improve predictive robustness precisely in such challenging scenarios, the integration of physical mechanisms and data-driven methods has become the forefront of current research. Current integration strategies fall into two main types. The first involves mechanism-guided, data-driven modeling, which includes using data assimilation algorithms such as Kalman filtering to calibrate traditional models, while another method embeds mechanistic knowledge directly into ML frameworks to improve predictive accuracy[12,73]. For example, integrating algal growth dynamics with a Logistic model to estimate algal growth potential can accurately simulate algal growth trends (NSE ≈ 0.58)[74]. The second strategy involves inferring mechanisms from data, such as using optimization algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) to identify key model parameters or learn unspecified ecological processes[75]. A deeper level of integration is embodied in coupled modeling frameworks. For instance, combining the data-fitting capability of statistical models with the mechanistic reasoning of process-based models to achieve a leap from predicting biocontaminant concentrations to assessing ecological risks[76].

Table 2. Prediction horizon of AI models for aquatic biocontaminant outbreaks

Biocontaminants AI model Best key performance Prediction horizon Ref. Harmful algal bloom CNN NSE = 0.84 3, 7 d [77] General RNN, SVM R2 ≈ 0.82 1, 2 weeks [78] ANN, SVM R2 ≈ 0.97 7 d [79] CNN R2 ≈ 0.93 1 week [80] ANN Accuracy = 89% 1 month [81] LSTM R2 ≈ 0.821 3 months [82] MLP R2 = 0.26 1 week [83] Support vector regression (SVR), MLP, RF R2 = 0.78 1 d [84] GBM Accuracy ≈ 90% 10 d [85] GBDT R2 = 0.97 1, 2 week [86] ANN, SVM Accuracy = 81% 1 week [87] ANN and SVM Accuracy = 100% 1 week [88] Pathogens RF Accuracy = 97% Summer months [89] ANN, RF Accuracy = 81% Several hours [90] LASSO, RF R2 = 0.62 1 d [91] Boosted regression trees (BRT) R2 = 0.67 1–2 weeks [92] Viruses PLS, XGBoost, categorical boosting, GRU, LSTM R2 = 0.97 Several hours [73] ANN, MLP R2 = 0.89 Several hours [93] Short-term dynamic prediction for early warning of sudden risks

-

The core task of short-term dynamic forecasting is to provide hour-to-day warning for sudden biological pollution events, such as the rapid release of algal toxins and pathogen outbreaks. Its fundamental goal is to shift the paradigm from 'passive post-event disposal' to 'proactive pre-event intervention'[92]. Given the high time-sensitivity of these events, which demands greater capabilities from models in real-time identification, critical threshold recognition, and immediate decision-making support. AI enables the integration of real-time data with efficient algorithms, creating a rapid cycle of perception, prediction, decision, and response[94].

The critical first step toward accurate short-term prediction is to quickly identify the key drivers of sudden events and make instant judgments. This type of task focuses on quickly classifying pollution probabilities or making determinations based on real-time data. Models such as gradient boosting decision trees excel in these scenarios due to their superior feature selection capabilities and high computational efficiency[95]. For instance, by analyzing early biomarkers such as algal volatile organic compounds, the XGBoost model can achieve early prediction of algal density surges (R2 ≥ 0.95), with response speeds significantly surpassing those of traditional physicochemical parameter-based models[96]. Similarly, feature-driven models can reveal interactions among environmental factors; for example, when lake turbidity exceeds 25 NTU, the probability of Escherichia coli outbreaks increases sharply by 80%, providing minute-level decision support for beach closures[96,97]. The effectiveness of these rapid judgments, however, is contingent upon high-quality feature engineering and requires causal validation of the identified drivers with domain knowledge to avoid the risks inherent in acting upon spurious correlations.

Based on the identified key factors, the prediction model needs to further quantify the nonlinear effects between factors and their critical thresholds, and to transform the predicted results into actionable intervention strategies. XAI plays a pivotal role in this phase. Methods such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and partial dependence plots (PDPs) can clearly reveal the contributions of different environmental variables to prediction results and their interaction mechanisms[98]. For example, by analyzing monitoring data, XAI techniques have identified water temperature > 23 °C and dissolved oxygen < 6 mg/L as critical water quality thresholds for total coliform outbreaks (accuracy 97%), providing clear intervention targets for ecological management[89]. While giving these crucial insights, the practical utility of XAI can be moderated by the computational intensity required to generate explanations, their inherent complexity, and the potential for inconsistent results across different methods, which together may create a significant interpretation barrier for non-expert decision-makers.

The ultimate value of short-term prediction is its ability to form an intelligent, self-operating closed loop that acts from prediction to response. Leveraging edge computing architecture, lightweight models can be integrated with sensing systems to achieve real-time decisions that are made directly at the monitoring site[99]. For example, data from just one or two online sensors (e.g., free chlorine) can enable real-time classification and prediction of microbial safety in reclaimed water at the edge (false alarm rate ≤ 2%). These results can be directly linked to disinfectant dosing systems for adaptive control[100]. This signifies that short-term prediction is evolving from an auxiliary decision-making tool into the core of autonomous, real-time, responsive intelligent control systems. Yet, the reliability of such autonomous loops is intrinsically linked to overcoming the earlier challenges of robust feature identification and interpretable decision pathways.

Long-term trend simulation for ecological risk management

-

Long-term assessment of ecological effects aims to reveal the cumulative, delayed, cascading, and even irreversible impacts of biocontaminants (such as persistent pathogenic microbial communities, recurrent algal blooms and their residual toxins, and continuously disseminating ARGs in aquatic networks) on ecosystem structure and function over monthly, annual, or longer timescales[101]. The core challenge is to decipher how these active contaminants, through complex biological interactions (e.g., HGT, host-pathogen dynamics) and nonlinear ecological processes, ultimately lead to crossing ecological thresholds and the degradation of ecosystem service functions[102]. By integrating long-term observation series, such as eDNA metabarcoding and remote sensing monitoring, with mechanistic models, AI enables a predictive leap from assessing instantaneous contaminant concentrations to evaluating long-term risks to ecosystem health[103].

The primary step in long-term assessment involves identifying the key drivers of changes in ecosystem structure and ecological thresholds influenced by biological pollution processes. AI models can extract patterns from long-term sequential data that govern community succession and system-state transitions under pollution stress[104]. For example, integrating eDNA metabarcoding with ML algorithms enables high-precision spatial positioning of key algal driver taxa and quantification of their contribution to long-term variation in the phytoplankton index, thereby identifying priority targets for ecological restoration[53]. The fusion of supervised learning with alternative stable state theory further allows the identification of critical conditions for ecosystem regime shifts. For instance, research has revealed biostability control thresholds for turbidity and eukaryotic plankton community stability (17 NTU and 24 NTU), providing a quantitative basis for precise ecological restoration[105]. However, the predictive power of these identified thresholds is fundamentally challenged by ecosystem complexity and feedback mechanisms, which means that such critical thresholds are likely not fixed values[106], but may shift with the system's historical state and external stressors[107], thereby constraining the early-warning capabilities of AI models trained predominantly on historical data.

Building on the understanding of structural evolution, AI further advances the long-term simulation and prediction of key ecological processes and service functions[108]. Dynamic simulation of ecological processes constitutes a core step in assessing functional degradation. For example, within a thermally stratified reservoir, a DL model successfully deciphered the vertical distribution patterns of dissolved organic matter-associated microorganisms, quantified their assembly processes across depth gradients, and constructed a stability index for the co-occurrence network, thereby accurately predicting the attenuation of carbon sink function resulting from hypoxic zone expansion[109]. However, the development of such high-fidelity models for simulating complex processes is critically dependent on the availability of exceptionally large-scale, long-term, multidimensional observational data, where the cost and difficulty of acquisition pose a significant bottleneck to their widespread application.

The ultimate value of long-term assessment is to translate ecological predictions into quantifiable risk assessments and support management decision-making. AI models show great potential by transforming ecological changes into specific socio-economic impact indicators, thereby providing a scientific basis for strategic planning[110]. For example, multi-agent simulation technology has been employed to convert the negative correlation between algal bloom duration and tourism revenue into actionable decision metrics, quantifying the potential economic losses to regional economies from increased algal coverage[99]. While these approaches indicate that AI can enhance the scientific rigor and foresight of long-term ecological assessments, making them an indispensable component of scientific decision-making, the reliability and applicability of such socio-economic outcomes still require comprehensive evaluation within specific local contexts and alongside field observations before they can be confidently operationalized.

In summary, through temporal analysis, feature-driven approaches, and preliminary integration with ecological mechanisms, AI models have demonstrated strong potential to capture the nonlinear characteristics of aquatic environmental systems, significantly enhancing dynamic, multi-scale early-warning capabilities for predicting biological pollution processes. Their value lies in providing decision support for risk management, spanning from short-term emergency response to long-term assessment. However, the full realization of this potential is currently constrained by several pronounced limitations. Their heavy reliance on data correlations results in significant 'black-box' characteristics. This problem is further compounded by an inadequate representation of intrinsic ecological mechanisms, such as microbial growth dynamics and HGT, which constrains both the scientific value and predictive reliability of these models in new scenarios. Furthermore, the scope of current predictive efforts remains somewhat narrow, confined mainly to forecasting contaminant concentrations and often overlooking the critical quantification of transmission risks.

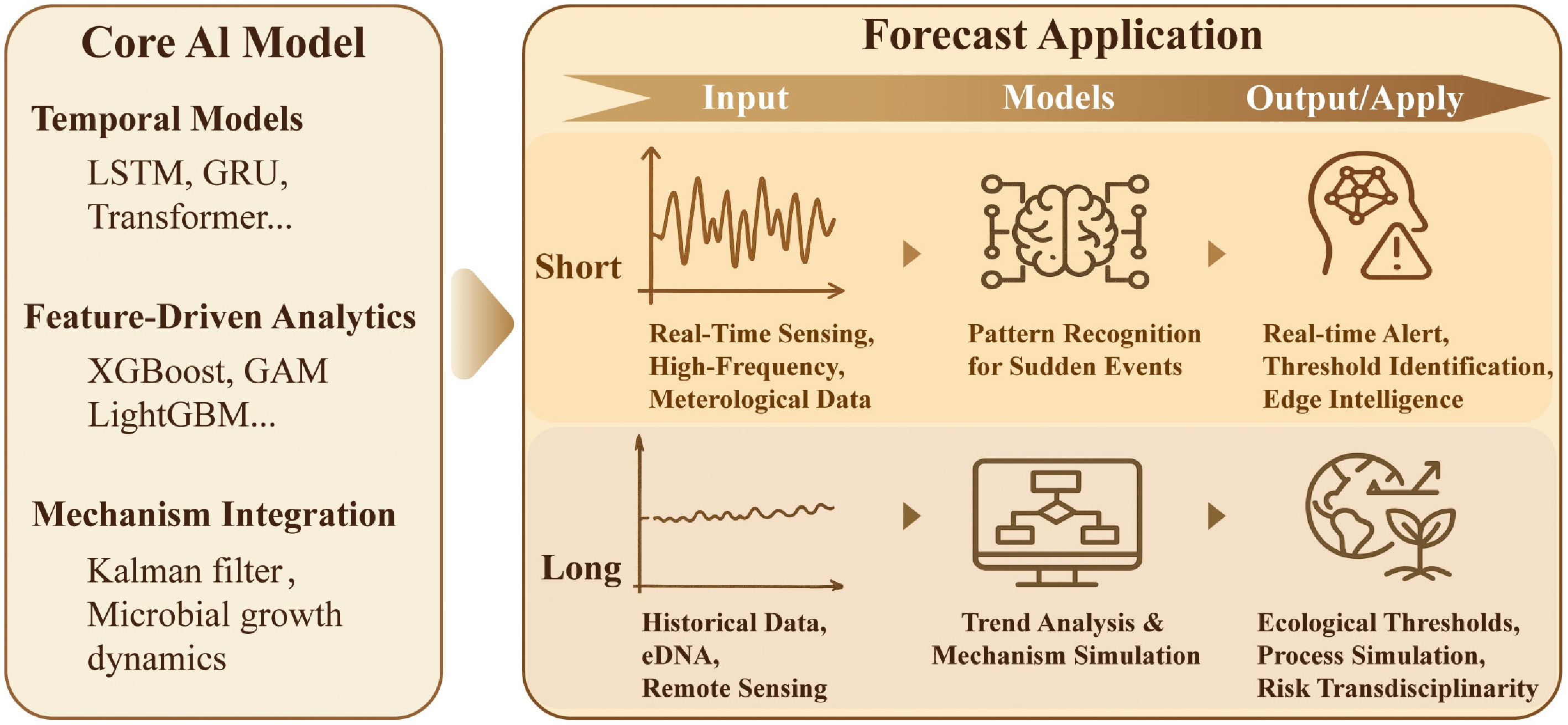

-

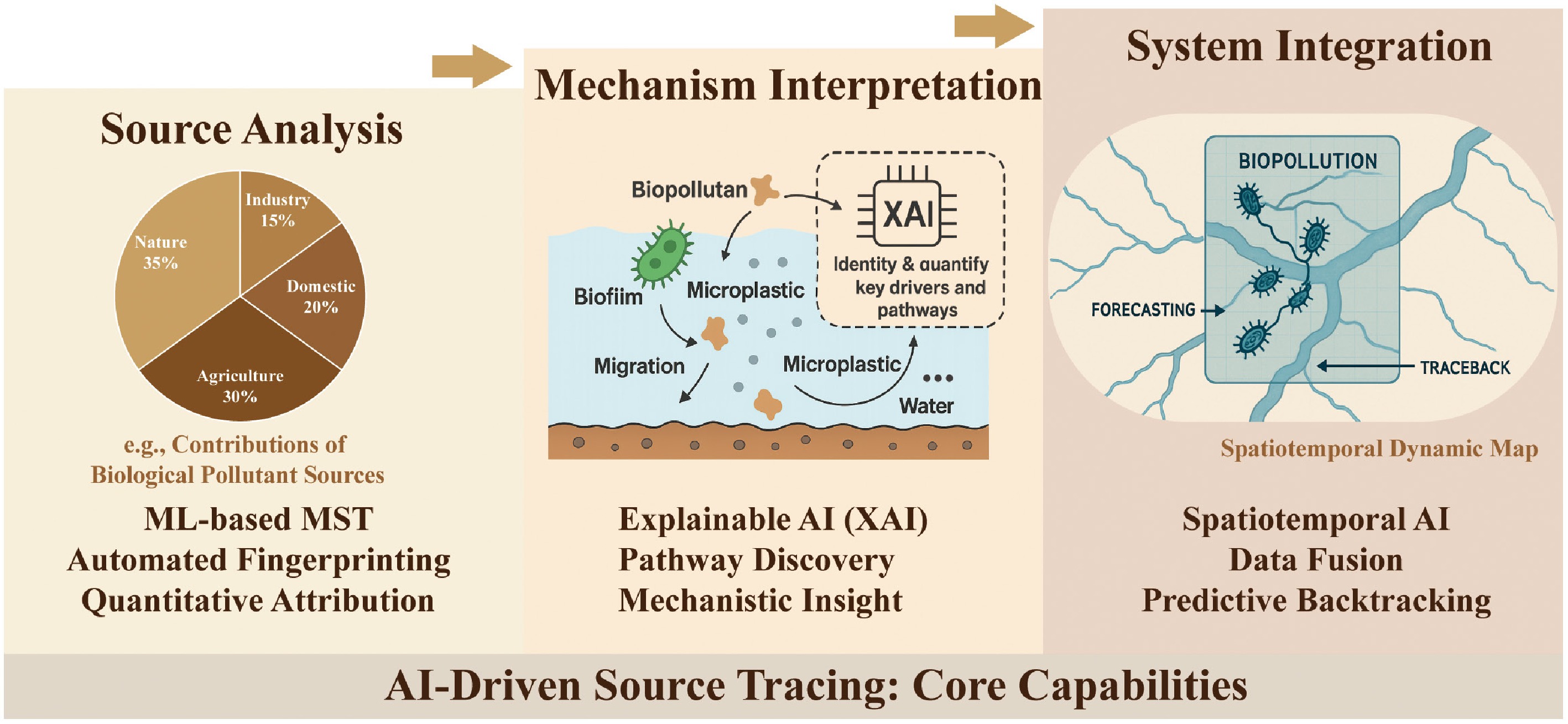

Accurate source tracing serves as a critical bridge linking pollution phenomena to control measures, and its technical complexity is continually increasing. The AI-driven tracing paradigm discussed in this chapter has moved beyond traditional qualitative inference, showing a clear progression from quantification through interpretation to simulation. This progression begins with innovations in Microbial Source Tracking (MST) algorithms, enabling precise quantification of the proportional contributions from different sources in mixed pollution. It then advances as XAI elucidates the transmission pathways and driving mechanisms of contaminants, such as ARGs, across multiple media environments. Ultimately, by integrating multi-source spatiotemporal data, dynamic tracing models capable of reconstructing historical contamination events and predicting future diffusion trends are emerging (Fig. 4). This technological evolution is advancing tracing capabilities, moving beyond static, qualitative approaches toward dynamic, quantitative, and mechanism-based methodologies.

Figure 4.

A tripartite framework of AI-driven source tracing capabilities for biocontaminants in water environments. The framework progresses from source apportionment to mechanistic interpretation and culminates in spatiotemporal integration. The left panel (Source Analysis) demonstrates the application of ML-based MST for automated fingerprinting and quantitative attribution, as shown in a pie chart that decomposes the relative contributions of domestic, agricultural, industrial, and natural sources. The central panel (Mechanism Interpretation) highlights the role of XAI in identifying and quantifying key drivers and pathways, including interactions among microplastics, biofilms, and contaminants during migration, thereby uncovering causal mechanistic insights. The right panel (System Integration) illustrates the synthesis of these capabilities via spatiotemporal AI, which fuses multi-source data to create a dynamic map enabling predictive backtracking of contamination events and forecasting of their dispersal. Collectively, this figure demonstrates how AI transforms source tracing from a static, descriptive exercise into a dynamic, interpretable, and predictive system essential for proactive risk management.

Algorithmic innovations in MST and quantification of contaminant contributions

-

The core principle of AI-driven source analysis is based on a fundamental hypothesis: different pollution sources (e.g., human/animal feces, sewage, soil) possess unique microbial community structures, termed microbial community fingerprints[111]. This fingerprint information is embedded within the complex data generated by high-throughput sequencing. The key breakthrough of AI algorithms lies in their ability to automatically learn and identify distinctive fingerprint features from massive microbial datasets, thereby accurately quantifying the proportional contributions of different sources in mixed pollution, and providing precise targets for prioritized management[112]. The accuracy of this powerful approach, however, depends on high sequencing depth and standardized bioinformatics analysis, and methodological discrepancies can complicate the direct comparison of results across studies.

A series of bioinformatics algorithms has been developed to analyze these fingerprints and perform source tracking. Bayesian statistics-based algorithms, such as SourceTracker, estimate the proportional contributions of different sources by comparing microbial community fingerprints of target water bodies with those of known source samples[113]. While powerful, the reliability of these Bayesian methods can be compromised by inaccurate or biased prior distribution assumptions. This is illustrated by a global study of 95 household drinking water systems, which analyzed microbial fingerprints of ARGs and quantified that anthropogenic sources contributed an average of 37.1% to ARG pollution. While providing scientific evidence for prioritizing the control of human-derived pollution, the robustness of this finding is inherently contingent on the quality of the prior data and model assumptions[114].

For complex scenarios with low-concentration pollution or high similarity among source fingerprints, more sophisticated algorithms have been developed to improve resolution. For instance, the Fast Expectation-Maximization for Microbial Source Tracking algorithm employs an optimized computational framework to more sensitively discriminate between rivers exposed to low-intensity fecal inputs (e.g., poultry vs livestock manure). Its performance surpasses that of traditional methods, demonstrating a more substantial capacity to capture subtle fingerprint signals[115]. Furthermore, unsupervised ML algorithms such as Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) can decompose latent, source-specific fingerprint profiles directly from complex community data without relying on a predefined source library, offering a new paradigm for more accurate, library-independent microbial source tracking[116]. The advantage of unsupervised methods in discovering unknown sources is counterbalanced by the challenge that the biological significance of the mathematically decomposed sources requires cautious interpretation, supported by field surveys and domain knowledge, to avoid mistaking mathematical abstractions for accurate pollution sources.

Analysis of transmission pathways and driving mechanisms of ARGs

-

Building upon the accurate identification of pollution sources, tracing research advances to a deeper level by revealing the transmission pathways and driving mechanisms of contaminants in the environment. The value of AI at this stage lies in its ability to decipher the complex networks of pollutant dissemination, such as ARGs[117]. Models like Random Forest can quantify the migration pathways of ARGs across multi-media environments (e.g., water–sediment–biofilm), identify key host genera such as Bacteroides and Clostridium, and locate diffusion hotspots, such as wastewater treatment plant outlets, thereby providing precise targets for blocking transmission routes[118]. XAI techniques, such as SHAP, elucidate the micro-scale driving mechanisms of ARG co-contamination with microplastics. For instance, SHAP analysis revealed that hydrophobic interactions dominate the facilitation of HGT by microplastics and unexpectedly indicated that biodegradable plastics may pose a higher transmission risk[13]. Furthermore, research combining exposure to microplastics and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) showed that their combined stress synergistically increased HGT risk by 27.6%. The integration of molecular dynamics simulations with ML allowed the study to identify key hydrogen-bond interactions between proteins and active sites. This revealed a 1.38-fold increase in HGT frequency caused by long-chain PFASs[119]. These correlation-based findings provide critical clues but underscore a fundamental principle: mechanistic insights generated by AI and modeling still require validation of causal relationships through controlled experiments (e.g., microcosm experiments), as models themselves cannot directly prove causation.

AI's innovation in long-term risk management is further demonstrated by its evolution from mechanistic inference to closed-loop decision support. For instance, the Maximum Entropy model can integrate climate change scenarios to predict the ecological niche vacancy trajectories of invasive species (e.g., zebra mussels), facilitating the early construction of biological barriers[53]. It is crucial to recognize that the predictive utility of models like MaxEnt is highly sensitive to the selection and correlation of input environmental variables, and their predictions carry spatial transfer uncertainty, necessitating careful uncertainty quantification in practical applications[120]. Meanwhile, Bayesian networks can incorporate cost-benefit analyses of restoration plans, quantifying the efficiency gains of wetland reconstruction for biodiversity recovery (e.g., 35% cost reduction and 22% increase in species recovery rates), thereby providing economic assessments to guide management decisions[105].

Multi-source information fusion and spatiotemporal dynamic tracing models

-

Building on advances in source analysis and mechanistic understanding, the highest level of tracing technology involves the systematic integration of multiple sources to construct spatiotemporal dynamic tracing capabilities[121]. Cutting-edge research is advancing the AI-driven tracing paradigm from static source-contribution analysis toward dynamic simulation of spatiotemporal migration pathways[122]. The core of this advancement lies in the efficient fusion of multi-source heterogeneous data. By integrating hydrometeorological data (flow velocity, flow direction, rainfall)[123,124], land use information (agricultural areas, drainage outlets)[125,126], real-time biosensing data, and metagenomic information[127,128], AI enables the development of spatiotemporal dynamic tracing models[129,130]. Such models can not only reconstruct the migration routes of contaminants to locate emission sources accurately but also predict the dispersion dynamics of contamination plumes, providing proactive decision support for pollution prediction and emergency response. The power of these integrated models, however, comes with substantial computational demands and stringent requirements on the spatiotemporal resolution and quality of input data, as any missing or erroneous data in the processing chain may be amplified during simulation, ultimately affecting tracing accuracy. Ultimately, this establishes a closed-loop analytical system capable of modeling the whole process of occurrence, diffusion, and source identification.

The practical value of spatiotemporal dynamic tracing technology is particularly prominent in public health, especially in wastewater-based epidemiology[131]. This methodology involves monitoring pathogen genetic signals (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 RNA fragments) in wastewater systems and integrating ML models. It enables the retrospective tracking of community infection hotspots and the modeling of viral transmission pathways and trends. A recognized limitation of this approach is its spatial imprecision, compounded by uncertainties from viral degradation and dilution in sewage, which make quantitative back-calculation of community infection numbers a persistent challenge. Despite this, it provides proactive and objective support for public health strategies, such as targeted lockdowns and resource allocation[132]. This methodology is not only applicable to viruses like COVID-19 but also offers a novel technical pathway for monitoring the transmission risks of traditional waterborne diseases, such as those caused by parasites[133]. Thereby, it can fully demonstrate the potential of integrated multi-source dynamic tracing models to enable targeted public health nterventions.

In summary, by empowering the complete chain of source analysis, mechanism interpretation, and system integration, AI has substantially enhanced the precision and depth of tracing techniques. Source tracing is evolving from quantifying source contributions based on microbial fingerprints to mechanistic elucidation of contaminant behavior in the environment, and then to initial attempts at dynamic simulation. While it is becoming increasingly accurate and predictive, providing critical targets for precise management, most current tracing analyses still provide largely static snapshots. The field has not yet fully overcome the challenge of simulating dynamic transmission processes within complex biological networks or quantifying cascading ecological risks, which means source tracing has not yet fully realized its potential for proactive risk early warning.

-

While AI holds considerable promise for advancing the management of aquatic biocontaminants, several persistent challenges must be overcome to transition these technologies from experimental tools to operational solutions[134]. The dynamic, evolving, and ecologically complex nature of biocontaminants introduces difficulties that extend beyond those associated with traditional chemical pollutants[135]. These challenges can be organized into four interrelated categories: data limitations, interpretability constraints, deployment barriers, and the divergence between data-driven correlations and ecological mechanisms.

First, there is a fundamental mismatch between the data requirements of AI models and the dynamic behavior of living contaminants. Bacteria, algae, and viruses grow, decay, and evolve genetically, meaning that practical AI training requires datasets that capture these population dynamics rather than static snapshots[136]. This issue is further compounded by the 'long-tail' data problem, where information on emerging pathogens, mutant strains, and low-abundance ARGs is extremely scarce[137]. As a result, models often fail to generalize to new or evolving biological threats. Moreover, the inherent heterogeneity of microbial community data means that source-tracking results are susceptible to sequencing depth and bioinformatic methodologies, raising concerns about the reliability of quantitative estimates[138].

Beyond data, the limited interpretability of complex AI models poses a significant barrier to their adoption in critical environmental decision-making[139]. The spread of biocontaminants is influenced by stochastic ecological events, yet most AI models produce deterministic outputs without clear confidence intervals. For decision-makers, the inability to understand model uncertainty makes it difficult to act on predictions. This lack of probabilistic reasoning undermines trust in alerts related to pathogen transmission or toxin risks. Although XAI methods can identify influential variables, they often fall short of elucidating the underlying biological mechanisms of interest[140].

On the practical front, deploying AI systems faces significant challenges related to resource constraints and adaptive capacity. Real-time outbreak response using edge devices must operate within limited processing and energy budgets, yet the most accurate models for complex biological data are often computationally intensive[139]. This creates a tension with sustainability goals and long-term integration into fixed infrastructure. Furthermore, enabling continuous model adaptation remains a critical hurdle. Given that biocontaminants evolve rapidly, even well-performing static models can quickly become obsolete. Implementing continuous learning on resource-limited hardware remains exceptionally challenging[141].

Perhaps the most profound challenge, however, lies in the disconnect between AI's data-driven approach and established ecological principles. AI models can identify correlations that may conflict with mechanistic understanding[142]. Yet, it has proven difficult to successfully incorporate prior knowledge (e.g., microbial growth kinetics, population competition, and HGT) into AI frameworks[143]. Without such mechanistic constraints, models exhibit poor extrapolation capability, rendering them unreliable for applications in new environments or for long-term risk assessment.

In summary, these challenges collectively point to a fundamental systemic issue. AI systems must be as adaptable as the ecosystems they monitor. The optimal solution will not be a static model but an adaptive intelligence able to incorporate real-time sensor data, learn from mispredictions, and evolve with the biocontaminants. Building such a sustainable intelligent system is the ultimate goal for the future of the field. This system must be capable of responding to climate change, human activities, and ongoing biological adaptation, which represent the most significant challenge ahead.

-

This review systematically examines the potential and limitations of AI in reshaping the management paradigm for biocontaminants in aquatic environments. The analysis demonstrates that AI is transforming the field from a 'passive response' model reliant on static, lagging data toward a 'proactive intelligence' paradigm based on real-time sensing, dynamic simulation, and accurate traceability, by driving the end-to-end intellectualization of identification, prediction, and source tracking. At the technical level, the integration of intelligent sensing and DL has initially enabled on-site, precise identification. The fusion of multi-source data with ML models has enhanced the timeliness and multi-scale capability of dynamic prediction. Furthermore, XAI, coupled with microbial source-tracking algorithms, has improved the quantitative accuracy and mechanistic depth of source analysis.

However, as critically discussed below, current research overall remains at an early stage of tool empowerment, facing three core bottlenecks that hinder the paradigm shift toward systematic cognition. First, the weak adaptive capacity of models to real-world environmental complexity constrains the universality of identification technologies. Second, the inadequate representation of intrinsic ecological mechanisms limits the accuracy and reliability of predictive models. Third, the lack of computability for transmission dynamics and cascading risks in multi-media environments impedes the advancement of tracing technologies toward proactive early warning. These challenges are compounded by data scarcity, model interpretability, and hardware constraints in real-world deployment.

To overcome these bottlenecks, future research needs to focus on three closely interconnected frontier directions:

(1) Developing adaptive and proactive intelligent sensing frameworks. To move beyond the current reliance on fixed datasets for identification, future efforts should focus on constructing foundational models for aquatic microbiomes that integrate real-time sensor data with metagenomic information. By incorporating continuous learning and anomaly detection algorithms, these systems can acquire the capability to actively scan for emerging contaminants, such as novel pathogens and ARGs, and to predict their evolutionary trends. This shifts the strategic emphasis from post-incident identification to pre-emptive early warning.

(2) Promoting deep integration of mechanism-based and data-driven approaches. Future predictive models must transcend pure data fitting by exploring frameworks such as physics-informed neural networks. These frameworks can internalize key ecological mechanisms as model constraints, including microbial growth dynamics, population competition, and HGT. Efforts must focus on employing XAI techniques to infer the mechanisms underlying driving factors, thereby shifting the paradigm from phenomenon prediction to mechanism simulation. This will provide a more solid theoretical foundation for ecological regulation.

(3) Constructing dynamic network-based risk assessment systems. This entails elevating the research perspective from analyzing single contaminants to understanding complex interaction networks at the ecosystem level. Future frameworks should leverage tools such as Graph Neural Networks to integrate multi-omics and environmental factor data, then construct pathogen-host-environment interaction network models. These models will simulate the dynamic transmission pathways of contaminants across various environmental compartments, identify critical risk nodes and ecologically vulnerable links, thereby enabling truly systematic risk assessment and precise intervention.

Through coordinated innovation in the directions outlined above, AI is poised to become the cornerstone of a predictive framework for aquatic ecosystems and provide a solid scientific and technological basis for aquatic ecological security and public health protection.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to this review as follows: study conception and design: Qinling Wang, Bing Wu; literature search, data analysis, and interpretation: Qinling Wang, Yiran Zhang, Wenze Wang; writing−original draft: Qinling Wang; writing−review and editing: Yiran Zhang, Wenze Wang, Xinyi Wu, Hailing Zhou, Ling Chen; supervision: Bing Wu; funding acquisition: Bing Wu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52388101).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

-

AI is transforming the management of aquatic biocontaminants from reactive to proactive.

Synergy of intelligent sensing and edge computing enables real-time and on-site monitoring.

AI delivers multi-scale forecasting from short-term warnings to long-term simulations.

Explainable AI quantifies pollution sources and deciphers transmission.

Future work focuses on self-learning AI and network-based risk assessment systems.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang Q, Zhang Y, Wang W, Wu X, Zhou H, et al. 2025. A review of AI-driven monitoring, forecasting, and source attribution of aquatic biocontaminants. Biocontaminant 1: e025 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0025

A review of AI-driven monitoring, forecasting, and source attribution of aquatic biocontaminants

- Received: 20 October 2025

- Revised: 18 November 2025

- Accepted: 26 November 2025

- Published online: 25 December 2025

Abstract: Biocontaminants in aquatic environments exhibit high viability, proliferative capacity, and spatiotemporal heterogeneity, posing a fundamental challenge to traditional static and lagging monitoring paradigms. Artificial intelligence (AI) is driving a paradigm shift from 'passive response' to 'proactive intelligence'. This review systematically elaborates the latest advances in the full-chain technical system powered by AI, including intelligent identification, dynamic prediction, and precise source tracking of aquatic biocontaminants. In the identification phase, intelligent sensing and edge computing synergize to enable on-site and real-time monitoring. The application of deep learning and generative AI-based augmentation enhances identification accuracy and robustness in complex scenarios. For prediction, AI involves integrating multi-source data for dynamic early warning of algal blooms, as well as coupling with ecological mechanisms to simulate long-term effects. Regarding source tracking, explainable AI can quantify the contribution rates of pollution sources and trace the transmission pathways of biocontaminants across multi-media environments. However, the deployment of AI faces challenges such as data scarcity, model interpretability, and integration with ecological mechanisms, which are critically examined. Finally, this article concludes by outlining future directions, including AI-based adaptive identification techniques for emerging biocontaminants, the deep integration of data-driven approaches with ecological mechanisms, and the establishment of AI-driven risk assessment frameworks. The AI-driven capabilities in sensing, prediction, and source tracking pave the way for a next-generation, precise management and control system for aquatic biocontaminants.