-

The means by which individuals consume nicotine have shifted with the introduction of electronic cigarettes, a change observed with particular frequency among younger cohorts[1−3]. These devices were initially positioned within the public sphere as a less harmful alternative to combustible cigarettes, and perhaps an aid for smoking cessation, a framing that held significant appeal for adolescents and young adults[4,5]. It is within this same demographic that a concurrent and well-documented increase in mental health difficulties, including depressive and anxiety-related conditions, has been observed[6,7]. The possibility that these are merely parallel non-related trends warrants careful consideration, and the subject has indeed attracted international research efforts with studies, for example, exploring the various determinants of e-cigarette uptake in settings as diverse as Turkey[8]. Existing reviews have certainly explored this area[9−11], yet the rapid pace of scientific inquiry suggests that a more current analysis is needed. Building upon earlier work that established a preliminary link between these phenomena, this particular review differentiates itself by concentrating strictly on the most recent body of literature spanning from 2019 to 2024, in an effort to map not only the correlational data, but also the proposed mechanisms and moderating factors that shape this complex association.

The initial harm-reduction narrative for e-cigarettes is being challenged by evidence pointing to an intricate, reciprocal relationship with mental health. This evidence suggests that e-cigarette use may trigger or intensify psychological distress, while individuals with pre-existing vulnerabilities appear more disposed to using them[5,12,13]. It is in response to this complex and evolving landscape that the present scoping review undertakes a systematic mapping of the existing research. The specific focus is a comprehensive overview of this connection derived from literature published between the beginning of 2019 and the close of 2024, sourced from the Scopus and Web of Science databases with the intention of synthesizing the most recent findings into a lucid evidence map designed to inform public health policy, clinical practice, and the direction of future inquiry in a timely fashion.

The matter gains additional weight because the developmental stages of adolescence and young adulthood constitute a crucial window for brain maturation, a period where the still-developing brain shows a pronounced susceptibility to both substance use and the initial presentation of mental illness[14,15]. A central concern therefore, relates to how nicotine, the principal addictive constituent found in most e-cigarettes, might adversely affect the nervous system during its formation[12]. The introduction of nicotine during these formative years could plausibly alter normative neurodevelopmental processes, a disruption that may contribute to long-standing cognitive and emotional challenges, and elevate the vulnerability for subsequent psychiatric disorders.

The wide availability of e-cigarettes, alongside youth-centric marketing, has fostered a general belief of reduced harm[16]. This perception is particularly significant for individuals with psychological difficulties who may vape as a form of self-medication to manage unpleasant emotional states[17−19], because the immediate albeit temporary relief the behavior provides can act as a powerful reinforcer for its use, which in turn encourages a pattern of dependence with the potential to worsen the underlying conditions it was initially used to soothe.

The analysis is further complicated by the frequent co-occurrence of e-cigarette use with other substances such as alcohol, cannabis, or even traditional cigarettes[20,21], a pattern of polysubstance use which is consistently linked to more pronounced mental health challenges and less favorable treatment results[22−25]. It is useful to distinguish here between 'dual use', a term reserved for the combined use of electronic and combustible cigarettes, and the broader category of 'polysubstance use', which encompasses the use of e-cigarettes with other psychoactive agents like cannabis because the specific mixture of substances can yield distinct and possibly amplified effects on psychological well-being. This fact highlights the importance of discerning precisely what is being aerosolized, whether nicotine, cannabis, or another substance, as this variable significantly modifies the observed mental health correlates[19], and thus requires an analytical framework that carefully considers the specific substances and behaviors involved, instead of treating 'vaping' as a single uniform activity.

It is also important to identify which groups are most affected, and some research points to sexual and gender minorities (SGM) as a population at a disproportionately higher risk for both vaping and certain mental health conditions[24,26,27], making an understanding of the specific stressors and risk factors that these communities experience an essential consideration for the development of effective interventions. Other life circumstances, from immigration status[28] to the stress of food insecurity[29], also appear to be significant factors in the observed relationship between substance use and mental wellness, and there is also a finding from some studies suggesting that individuals with mental illness can sometimes fully grasp the risks of vaping[18], a point that complicates simple assumptions about their vulnerability.

The existing research on this relationship is distributed across a variety of studies that focus on different populations, use disparate methods, and measure diverse outcomes, and so this scoping review represents an effort to draw these separate findings into a more coherent picture. The goal is to identify where the research aligns, where it conflicts, and to point out the gaps in our current understanding that require more investigation as effective public health policies, prevention strategies, and clinical guidelines must be based on this kind of evidence. By systematically mapping the current knowledge, this review aims to provide a useful resource for researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and educators, and the whole review will address four research questions that give structure to the results, exploring a relationship that is likely due to a mix of neurobiological, psychological, and social factors, and is influenced by key variables like age, and co-occurring substance use.

(1) What are the rates of e-cigarette use among individuals with various mental health disorders, and, reciprocally, what are the rates of mental health disorders among individuals who use e-cigarettes?

(2) What is the body of evidence supporting a reciprocal link between e-cigarette use and mental health?

(3) What are the proposed neurobiological, psychological, and social processes that might account for the association between e-cigarette use and mental health?

(4) Which variables are identified as moderators that alter the magnitude and directionality of the association between e-cigarette use and mental health?

-

The methodological direction for this scoping review drew upon the framework established by Arksey & O'Malley[30], a foundational approach that was considered alongside later modifications proposed by Levac et al.[31], and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)[32], with the reporting itself adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Supplementary Table S1). A protocol was intentionally not registered in advance, given that the primary aim was to map the existing literature broadly instead of testing a specific hypothesis. The work unfolded over five stages, which began by framing the research questions, and this led to the identification of relevant studies which were then selected for inclusion, followed by the charting of data and the process concluded with the synthesis and reporting of the results.

Stage 1: identifying the research questions: The inquiry was structured from the outset by four primary research questions which were established in advance to maintain a clear investigative focus, and as previously detailed in the introduction, these questions explored the prevalence of both e-cigarette use and mental health conditions, the evidence for bidirectional links, the potential mechanisms connecting them, and the significant moderating variables within this dynamic.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies: A systematic search strategy was constructed to identify publications released between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2024, with the search itself being undertaken on January 15, 2025, across two primary electronic databases, Scopus and Web of Science. These particular databases were chosen for their comprehensive indexing of peer-reviewed literature across the health, social, and psychological sciences, which provided a suitably broad interdisciplinary perspective on the research topic, and the potential for bias stemming from the exclusion of other databases is noted and will be discussed in the limitations section. This search strategy, which was designed in consultation with a research librarian, combined keywords and subject headings related to both electronic cigarettes (using terms like 'vaping', 'e-cigarette*', and 'ENDS'), and mental health (including 'mental health', 'depression', 'anxiety', and 'psychological distress') (Supplementary File 1).

The selection process was guided by specific eligibility criteria. Studies were required to be empirical in nature, which could include quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method designs, and they had to be primarily focused on the relationship between e-cigarette use and mental health. All studies involved human subjects and were published in English within the specified timeframe. To capture a wide spectrum of evidence from both general and clinical populations, no restrictions were applied based on participant age or clinical status. Studies were included if they examined the vaping of any substance, for instance, nicotine or cannabis, so long as the connection to mental health was a central theme of the research. Measures of e-cigarette use, whether recent (past-30-d), or over a lifetime, were both considered eligible. Conversely, materials such as literature reviews, conference abstracts, editorials, and any studies that did not use human subjects were excluded.

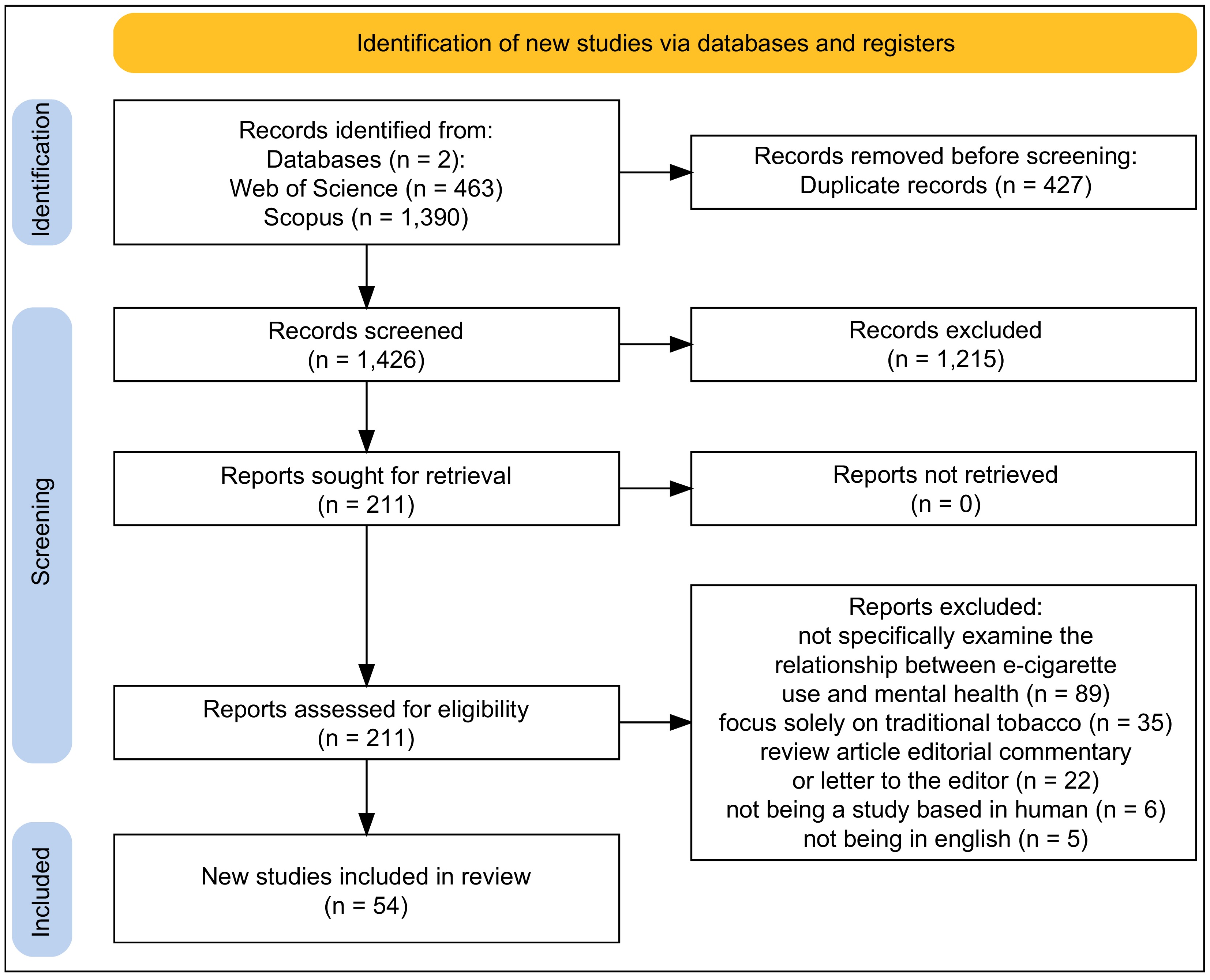

Stage 3: study selection: The selection of studies was conducted through a two-stage screening procedure where initially two authors (ML and MA) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all records identified by the search, a process which resulted in each record being classified as 'include', 'exclude', or 'unsure'. To ensure a thorough review, all records marked as 'include' or 'unsure' by at least one reviewer were advanced to the full-text assessment phase. Methodological rigor was maintained by verifying inter-rater reliability on a 10% sample of abstracts, which yielded a Cohen's kappa of 0.85, indicating strong agreement. In the second stage, the same two authors independently assessed the full text of the remaining articles against the final eligibility criteria, and any disagreements that emerged at this point were resolved through discussion, or if necessary, by consulting a third senior author for a final decision, a complete depiction of which is documented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1)[33].

Stage 4: data charting: To systematically extract information from the included studies, a data extraction form was developed by the authors. The form was based on a JBI template for scoping reviews. and was piloted on five of the included articles to ensure it was suitable for the research questions. The form was made to capture key information, including: author, publication, year, country of origin, study design, population characteristics, definitions of e-cigarette use, measures of mental health, core findings, and the author-stated limitations. The data extraction was performed independently by two authors (ML and MA). Following the charting, the reviewers met to compare their entries and resolve any differences through discussion.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results: Following the data extraction the process of bringing the results together began first with a descriptive numerical summary to provide a general overview of the included studies (fully detailed in Table 1), showing their design, geographic location, and population characteristics, this was then followed by a thematic analysis which served to organize the main findings into a narrative shaped by the review's research questions. A formal risk-of-bias assessment was not performed, which is in keeping with scoping review methodology but an informal appraisal of study design, looking at things like whether a study was cross-sectional or longitudinal, and its sample size, was still a part of the synthesis to help provide some context for the strength of the evidence. This inductive approach revealed several recurring themes that touched on prevalence bidirectionality, the underlying neurobiological, psychological, and social mechanisms, key moderating factors, and the synthesis also incorporates a discussion of the limitations observed within the primary studies, and the constraints of the scoping review method itself.

Table 1. Characteristics and Key Findings of Included Studies.

Study (year) Country Design Sample size Population Measures of e-cigarette use Measures of mental health Key findings related to e-cigarette use and mental health Lilly et al. (2024)[55] USA Longitudinal 1,349 Middle and high school students Past-year e-cigarette use School as a Protective Factor-Brief (SPF-Brief) survey (school climate, anxiety, depression, quality of life) A school environment perceived as more positive as indicated by higher SPF-Brief scores was associated with fewer reported symptoms of anxiety and depression and this climate appeared to function as a protective element against substance use including e-cigarettes. Ormiston et al. (2024)[28] USA Longitudinal 1,060 Alternative high school students Past-year e-cigarette and other substance use Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) A more pronounced association between psychosocial distress and the use of substances like e-cigarettes was observed in first- and second-generation immigrant students when compared to their third-generation counterparts. Liu et al. (2024)[16] USA Cross-sectional 1,547 Adults reporting past 30-d tobacco use Past 30-d vaping of nicotine, cannabis, CBD, or other substances Self-rated anxiety The concurrent vaping of nicotine with cannabis or CBD in the preceding month was a behavior reported by 26.1% of participants and its likelihood was significantly greater among males and individuals reporting higher anxiety. Thepthien et al. (2024)[20] Thailand Cross-sectional 5,740 High school students Past 12-month prevalence of conventional cigarette (CC), electronic cigarette (EC), and dual use Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), psychological distress (PD), depression, anxiety, and problem gambling (PG) scales Other substance use mental health difficulties and peer or family smoking were correlates for CC EC and dual use with exclusive EC and dual use being linked to more depressive symptoms and exclusive EC use also associated with greater anxiety. Yimsaard et al. (2024)[21] International Longitudinal 3,709 Daily smokers Vaping status at follow-up, quit attempts, 1-month quit success Validated screening tools for depression, anxiety, and regular alcohol use (baseline) Smokers who reported depressive symptoms were found to be more likely to make a quit attempt but had lower rates of success while successful quitters with depression or anxiety had a higher likelihood of vaping at the follow-up assessment. Mantey et al. (2024)[40] USA Longitudinal 2,605 Youth and young adults Transitions in cannabis vaping (never, ever, current) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression; Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety Alcohol use was predictive of cannabis vaping across all racial and ethnic groups and depression was a predictor for the initiation of cannabis vaping among Hispanics and for experimentation among non-Hispanic Black participants. Pitman et al. (2024)[29] USA Cross-sectional 1,024 Young adults Current cigarette, ENDS, cannabis, and alcohol use; binge drinking Food insecurity measure (Hunger Vital Signs), perceived stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and insomnia After accounting for demographics economic factors mental health and discrimination food insecurity remained associated with elevated odds for all types of substance use which included ENDS. Klein et al. (2024)[39] USA RCT 981 Young adult exclusive e-cigarette users E-cigarette use behaviors, previous quit attempts, nicotine dependence Self-reported stress, anxiety, and depression Among young adults who were seeking treatment to stop vaping a high prevalence of nicotine dependence a history of unsuccessful quit attempts and co-occurring stress anxiety and depression was observed. Cai & Bidulescu (2024)[12] USA Cross-sectional 56,734 US adults Current, former, and never e-cigarette use; dual use with cigarettes National Health Interview Survey measures for anxiety, depression, serious psychological distress (SPD), and cognitive impairment Compared to never-use current e-cigarette use former use and dual use were each associated with greater odds of experiencing anxiety depression SPD and cognitive impairment. Vaziri et al. (2024)[36] USA Cross-sectional 226 People with cystic fibrosis (pwCF) Past 12-month use of marijuana, CBD, e-cigarettes, and cigarettes Abnormal mental health screen In this population substance use including e-cigarettes was found to be more common than previously documented and those who used e-cigarettes were significantly more likely to have an abnormal mental health screening outcome. Phetphum et al. (2024)[5] Thailand Cross-sectional 3,424 Youth Past 30-d cigarette, e-cigarette, and dual use Depression and anxiety symptoms scales Both current e-cigarette users and dual users showed higher odds of depression and e-cigarette users also had higher odds of anxiety whereas smokers of only cigarettes had lower odds of anxiety compared to non-users. Kang & Malvaso (2024)[42] UK Longitudinal 19,706 UK general sample E-cigarette use status (at two time points) General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) measuring general mental health, social dysfunction & anhedonia, depression & anxiety, and loss of confidence Participants who took up e-cigarette use between the two waves showed poorer mental health greater social dysfunction and anhedonia and more loss of confidence when compared to their own status from a year earlier. Adzrago et al. (2024)[1] USA Cross-sectional 4,766 Adults Exclusive e-cigarette use, exclusive cannabis use, and dual use Anxiety/depression While anxiety/depression was correlated with a higher risk for exclusive cannabis use and dual use irrespective of immigration status its link to exclusive e-cigarette use was only significant for the immigrant population. Zvolensky et al. (2024)[13] USA Cross-sectional 297 Latinx adult daily cigarette smokers Current dual use of e-cigarettes with combustible cigarettes A battery of scales measuring anxiety, depression, emotional dysregulation, anxiety sensitivity, and distress tolerance. When compared with those who exclusively smoked combustible cigarettes Latinx adults who were dual users showed significantly higher levels of anxiety depression and emotional dysregulation which was also coupled with lower distress tolerance. Evans et al. (2024)[14] USA Cross-sectional 316 Young adults Vape use (unspecified) Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), Rumination scale, reduced Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (rMEQ), Self-compassion scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) In comparison to non-users individuals who vaped reported lower mindfulness and self-compassion alongside higher rumination and anxiety poorer sleep quality and a stronger inclination toward an evening chronotype. Trigg et al. (2024)[18] Australia Cross-sectional 3,002 South Australian adults (+15 years) Vaping, smoking Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) for anxiety and depression Individuals with depression who also vaped tended to perceive greater health risk barriers related to accessing nicotine vaping products (NVPs) through a prescription for the purpose of smoking cessation. Han et al. (2024)[15] USA Longitudinal 5,114 Young adolescents E-cigarette use Internalizing problems (Profile of Mood States anxiety subscale; Centers for Epidemiology Studies of Depression (CES-D) scale) and externalizing problems (Current Symptoms Scale for ADHD; Brief Sensation Seeking Scale) The availability of tobacco in the home increased the odds of e-cigarette use whereas home rules against non-combustibles decreased them and the protective effect of these rules was stronger for adolescents with internalizing problems but weaker for those with externalizing problems. Dabravolskaj et al. (2023)[6] Canada Longitudinal 24,274 High school students Adherence to substance use recommendations (including e-cigarettes) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R-10); Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Following healthy lifestyle recommendations which included abstaining from e-cigarettes was associated with lower depression and anxiety scores at a one-year follow-up point. Salinas et al. (2024)[17] USA Cross-sectional 492 Adults who vape nicotine, cannabis, or both Nicotine, cannabis, and dual vape use behaviors Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression; Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7); Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) Those who engaged in dual use of cannabis and nicotine vapes reported a greater severity of mental health symptoms when compared to individuals who vaped only one of the substances. Azagba et al. (2024)[54] USA Cross-sectional 23,445 Youth Past-30-d e-cigarette use Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) for anxiety and depression; time on social media The association between the amount of time spent on social media and the likelihood of past-30-d e-cigarette use was mediated by symptoms of anxiety and depression. Leung et al. (2024)[2] Australia Cross-sectional 716 University students Lifetime and past-month vaping (flavor, nicotine, other drugs) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression; Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Vaping was found to be correlated with being male smoking cigarettes binge drinking and using cannabis and it was also noted that a significant percentage of students were not informed about the legal status or potential health risks of vaping. Bataineh et al. (2023)[7] USA Longitudinal 60,072 Adolescents and young adults Lifetime cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use Depressive and anxiety symptoms Based on the observed associations it was recommended that mental health screening should occur earlier for tobacco and cannabis users especially for individuals aged 18 and younger. Arterberry et al. (2023)[52] USA Cross-sectional 1,244 Young adults Increased vaping, drinking, and marijuana use to cope with COVID-19 isolation Depression and anxiety symptoms Stress related to social distancing during the COVID-19 period was associated with an increase in vaping to cope for those with higher depression symptoms and an increase in drinking to cope for those with higher anxiety symptoms. Tildy et al. (2023)[45] International Cross-sectional 11,040 Adults Discussing and receiving recommendations for NVPs from a health professional (HP) Self-reported current depression and/or anxiety Individuals with anxiety and/or depression who smoked were more likely to visit an HP but it was only those with depression who were more likely to get advice to quit. Adzrago et al. (2023)[26] USA Cross-sectional 6,267 Black/African American Adults E-cigarette use status (never, former, current) Symptoms of anxiety/depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-4, PHQ-4) Within sexual minorities lesbian/gay individuals showed higher rates of former e-cigarette use whereas bisexual individuals reported higher rates of current e-cigarette use. Oliver et al. (2023)[57] USA Cross-sectional 474 Adolescents and Young Adults Prior 12-month substance use, including vaping Symptoms of depression (Patient Health Questionnaire – 2 item, PHQ-2) In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic vaping was linked to depressive symptoms and lower adherence to non-pharmaceutical mitigation measures among adolescents and young adults. Keum et al. (2023)[43] USA Cross-sectional 338 Racially Minoritized Emerging Adults Recent cigarette smoking, marijuana use, and vaping Depressive (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) symptoms Experiences of racism both online and offline were indirectly associated with recent marijuana use a relationship that was mediated by depressive and anxiety symptoms. Leung et al. (2023)[4] Australia Cross-sectional 855 High School Students E-cigarette use (flavor-only and nicotine) Depression and anxiety Risky drinking and smoking cigarettes were identified as strong predictors of concurrent e-cigarette use which points to a high-risk polysubstance use profile. Hanafin et al. (2023)[3] Ireland Cross-sectional 5,190 Young adults Ever and current smoking; ever and current e-cigarette use Self-reported professional diagnosis of a mental health problem (MHP) The association between mental health problems and the use of e-cigarettes was found to be similar in its nature and magnitude to the well-documented association between MHP and smoking. Hahn et al. (2023)[35] USA Cross-sectional 7,431 People with HIV Vaporized Nicotine (VN) and Combustible Cigarette (CC) use Depression (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10) and Panic Symptoms (Panic Symptomatology) The observed associations between VN/CC use and symptoms of depression or panic suggest that VN may play a potential role in both self-medication and as a substitute for CC in this specific population. Clendennen et al. (2023)[22] USA Longitudinal 2,148 Youth and young adults Cigarette, e-cigarette, and marijuana use Anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, perceived stress The study's findings indicated a bidirectional relationship where elevated mental health symptoms were predictive of future increases in the use of cigarettes e-cigarettes and marijuana. Oyapero et al. (2023)[23] Nigeria Cross-sectional 898 Residents E-cigarette (EC) use Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7); Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) Smoking cigarettes consuming alcohol being susceptible to future smoking and depression were all identified as strong predictors of e-cigarette use. Salazar-Londoño et al. (2023)[49] Colombia Cross-sectional 3,850 Young Colombians Consumption of Electronic Nicotine/Non-nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS/ENNDS) Self-reported history of mental/emotional pathology; symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and loneliness Symptoms of anxiety and loneliness were found to be more common among participants who had risky ENDS/ENNDS consumption patterns when compared to those who did not. Adzrago et al. (2023)[26] USA Cross-sectional 6,268 Black/African American Adults E-cigarette use behaviors (never, former, current) Anxiety/depression symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-4, PHQ-4); perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes E-cigarette use behaviors were found to be significantly associated with anxiety/depression the perceived harmfulness of the product and the interaction between these two variables. Bista et al. (2023)[53] USA Cross-sectional 4,634 Students Cigarette or e-cigarette use Psychological distress An observable increase in nicotine use which included e-cigarettes was noted in the period immediately after the implementation of campus closures for public health safety reasons. Adzrago et al. (2022)[60] USA Cross-sectional 5,065 Adults Past 30-day frequent use of e-cigarettes Anxiety/depression, alcohol use, cannabis use, COVID-19 impact The probability of frequent e-cigarette use was higher among individuals with certain risk factors which included frequent consumption of alcohol or cannabis a diagnosis of depression or anxiety and stress related to social distancing. Azagba et al. (2022)[27] USA Cross-sectional 16,065 Youth Current e-cigarette use Self-reported anxiety and depression It appears that sexual minority males who have co-occurring mental health conditions represent a particularly vulnerable population with respect to e-cigarette use. Striley et al. (2022)[19] USA Cross-sectional 47,016 College students Past 30-day use of a vaping product (nicotine or marijuana) Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) A positive association between past 30-d vaping and NSSI was identified although more research is needed to confirm this finding and to examine any potential confounding variables. Wade et al. (2022)[50] USA Cross-sectional 201 Emerging Adults Past 6-month nicotine and tobacco product (NTP) use patterns Depression and stress symptoms Users of combustible tobacco seem to be qualitatively different from non-combustible users when considering mental health correlates which suggests the existence of distinct user profiles. Schuler et al. (2022)[37] USA Cross-sectional 16,699 Armed forces active duty service members Current e-cigarette use, smoking, and other substance use Probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety The differences observed in substance use and mental health between the various service branches were not fully accounted for by demographic or deployment/combat experience variables. Adzrago et al. (2021)[24] USA/Texas Cross-sectional 1,103 Sexual and gender minorities Recent tobacco use, including e-cigarettes Diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or PTSD; hazardous alcohol use; illicit substance use There is an existing need for tailored tobacco cessation interventions to be implemented within substance use treatment facilities to address the high rates of use among SGM individuals. Williams et al. (2021a)[25] Canada Cross-sectional 51,767 Secondary school students Alcohol, cannabis, cigarette, and e-cigarette use Anxiety and depression symptoms Dual and polysubstance use were found to be common among Canadian secondary students and anxiety and depression were significantly associated with these use patterns. Williams et al. (2021b)[44] Canada Longitudinal 738 Secondary school students Alcohol, cannabis, cigarette, and e-cigarette use Anxiety and depression The findings highlight the need for comprehensive programming that addresses multiple substance uses and is also aware of co-occurring mental illness symptoms particularly depression. Mayorga et al. (2021)[48] USA Cross-sectional 566 Adult e-cigarette users Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS) use patterns Anxiety sensitivity, anxious arousal, general distress, and anhedonia The results underscore the necessity of incorporating anxiety-related constructs into etiological models to achieve a better understanding of e-cigarette use patterns and behavior. Wattick et al. (2021)[51] USA Cross-sectional 3398 College students E-cigarette use and motivations for use Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), mental health Efforts aimed at reducing e-cigarette use should also address the co-use of alcohol co-occurring mental health disorders and the social motivations for use. Jones et al. (2021)[56] USA Cross-sectional 872 College Students E-cigarette use Self-efficacy, knowledge, depression, and anxiety symptoms Modifiable factors such as knowledge about harmful effects and having the self-confidence to refuse use were associated with a lower prevalence of e-cigarette use. Spears et al. (2020)[47] USA Cross-sectional 5878 Adults Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS) use patterns Serious psychological distress (SPD), mental health conditions (MHC), reasons for use It seems that individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions may be particularly inclined to use ENDS for the purposes of relaxation and managing stress. Wamamili et al. (2021)[38] New Zealand Cross-sectional 1293 University Students Vaping and smoking History of mental illness (HMI): diagnosis/treatment for depression, anxiety, or other mental health condition in past 12 months A strong association was found where students who reported a history of mental illness also showed significantly higher prevalence rates for both smoking and vaping. Pham et al. (2020)[58] Canada Cross-sectional 53,050 General population E-cigarette use PHQ-9, self-reported mood/anxiety disorders, perceived mental health, suicidality E-cigarette use is associated with adverse mental health outcomes and this association was observed to be particularly strong among non-smokers and women. Bianco et al. (2019)[34] USA Cross-sectional 631 Adults Lifetime and current e-cigarette use Chronic mental illness (depression, anxiety, emotional disorder, ADD, bipolar, schizophrenia, etc.) The findings lend support to previous research by indicating an increased likelihood of both lifetime and current e-cigarette use among individuals who have a chronic mental illness. Hefner et al. (2019)[59] USA Cross-sectional 631 College Students Past 30-day e-cigarette and other tobacco use Self-reported diagnosis of psychiatric and substance use disorders Additional research is needed to clarify the relationships between risky alcohol and nicotine use and mental illness in order to guide intervention efforts for college students. Versella et al. (2019)[41] USA Cross-sectional 264 Adult ENDS Users ENDS and Combustible Cigarette use Internalizing symptoms (stress, anxiety) and vulnerabilities (Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3, Distress Intolerance Index, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale) The way internalizing pathology and vulnerabilities present among nicotine users appears to be influenced by both their current use and their past history of nicotine product use. Li Lin et al. (2019)[46] International Cross-sectional 11,344 Smokers and Quitters Vaping activities and use as a quitting strategy Medical diagnosis for nine health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and alcohol problems The study did not find any systematic evidence to suggest that having a poor health condition related to smoking increased the probability that an individual would turn to vaping as a method for cessation. Source: Developed by the authors based on data extracted from the included studies. -

The initial database searches identified 1,853 records. After removing duplicates, the screening of 1,426 unique titles and abstracts produced 211 potentially relevant articles for full-text review. An independent assessment by two reviewers followed, and any discrepancies were settled through consensus or, when necessary, consultation with a third reviewer, leading to the exclusion of 157 articles. Articles were removed if they did not examine the relevant relationship, focused solely on traditional tobacco, were non-empirical, or otherwise failed to meet inclusion criteria. This process resulted in a final group of 54 studies for this scoping review. The whole study selection procedure is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1), and the characteristics and core findings of each included study are detailed in Table 1.

Geographical distribution of included studies

-

The 54 studies included in this review showed an unbalanced geographical representation. A large portion, nearly half (n = 26) came from the US. Further studies were from Canada (n = 6), the UK (n = 2), and Australia (n = 3). A smaller set of studies came from Thailand (n = 2), New Zealand (n = 1), Nigeria (n = 1), and several multi-country collaborations. This distribution, which spans North America, parts of Europe, Asia, and Oceania, provides a degree of generalizability. However, the unique cultural and regulatory contexts of each country must be considered when evaluating the results. The concentration of work in the US suggests a need for more research from other global regions.

Prevalence of e-cigarette use and mental health conditions: detailed findings

-

The key characteristics and findings of the 54 included studies are systematically summarized in Table 1. One of the most consistent observations, was a higher prevalence of e-cigarette use among individuals with mental health conditions, and the connection was also present in the other direction, with a higher occurrence of mental health conditions found among individuals who use e-cigarettes. The strength of this association did vary across the literature. These differences can be linked to variations in sample population, measurement approaches, or the specific definitions used for 'e-cigarette use', and 'mental health conditions', yet the general direction of the finding remained constant across the studies.

Specific mental health conditions

-

Depression and anxiety were the most examined conditions, but several investigations also included post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[24], attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)[34], and substance use disorders[35]. Generally, these studies reported higher rates of e-cigarette use across these populations. Hahn and colleagues[35], for instance, found that among individuals with HIV, depression, and panic disorder were more frequent in those with a history of vape use. Similarly, Vaziri et al.[36] noted that substance use was more common than expected in cystic fibrosis patients with abnormal mental health screens, while Schuler et al.[37] found significant associations between e-cigarette use and PTSD, depression, and anxiety among active-duty military personnel. In university settings, Wamamili et al.[38] confirmed that students with a history of mental illness had significantly higher prevalence rates for both smoking and vaping.

Severity of mental health symptoms

-

Some studies went beyond diagnostic categories to examine the association between the severity of mental health symptoms and e-cigarette use[22,27]. A consistent 'dose-response' relationship was observed, greater symptom severity was associated with a higher likelihood and frequency of using e-cigarettes.

Dual use and polysubstance use

-

The practice of dual-use (e-cigarettes with combustible cigarettes), and polysubstance use (e-cigarettes with alcohol, cannabis, or other substances) was common in cohorts with mental health conditions[20−22]. Zvolensky et al.[13] provided an example, showing that Latinx 'dual users' reported significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, and other psychological distress markers compared to those who only used combustible cigarettes.

Vaping cessation

-

A randomized controlled trial by Klein et al.[39] focused on young adults (18–24) using e-cigarettes for cessation. This group exhibited substantial nicotine dependence and a history of unsuccessful quit attempts, with 29.4% having tried NRT, and also presented with concurrent stress, anxiety, and depression.

Sexual and gender minorities

-

Research on sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations consistently showed elevated rates of e-cigarette use co-occurring with mental health conditions[24,26,27]. This suggests specific vulnerabilities within this demographic.

Bidirectional associations

-

A bidirectional relationship between e-cigarette use and mental health is supported by several longitudinal studies, where each can influence the other. For the purposes of this review, 'bidirectionality' refers to evidence where: (a) baseline mental health symptoms predict future e-cigarette use; and (b) baseline e-cigarette use predicts future mental health symptoms, even if not always within the same study. However, the precise patterns and strength of this connection varied.

Mental health predicting e-cigarette use

-

A common theoretical view is that vaping is used for self-medication, or as a maladaptive coping strategy[7,8,40]. People experiencing negative affect, stress, or other mental health symptoms may use e-cigarettes for the calming or mood-altering effects of nicotine. This perspective is supported by research that connects psychological vulnerabilities, such as anxiety sensitivity, to increased e-cigarette use[13,41].

E-cigarette use predicting mental health

-

When viewed from the opposite direction, some work suggests that e-cigarette use might itself be a predictor of later mental health difficulties, with the primary line of inquiry focusing on the neurobiological consequences of nicotine exposure, particularly within the context of the still-maturing adolescent brain[26,42,43], where the central idea is that sustained nicotine intake could potentially disrupt the very neurotransmitter systems responsible for mood regulation, thereby leaving an individual more susceptible to conditions like depression and anxiety, a line of reasoning that is not unlike the extensive evidence linking traditional cigarette smoking to similar outcomes in mental well-being.

Reciprocal relationships

-

A more intricate reciprocal model is also found within a few studies in which e-cigarette use and mental health problems are viewed as reinforcing one another over time[44], a dynamic from which it follows that effective interventions would probably need to address both issues simultaneously.

Mental health and vaping cessation

-

The issue is complicated further by factors related to cessation. Smokers with depression are often motivated to quit but may have more difficulty staying abstinent. Regarding professional support, Tildy et al.[45] found that while smokers with depression often visited healthcare professionals, they were not always more likely to receive advice to quit. For those who do stop smoking combustible cigarettes, a high likelihood of switching to vaping instead of stopping nicotine entirely seems to exist[21]. However, Li Lin et al.[46] noted that having a poor physical or mental health condition did not necessarily increase the probability that an individual would specifically turn to vaping as a method for cessation.

Underlying mechanisms: detailed findings

Neurobiological mechanisms

-

While most included studies did not directly measure neurobiological changes, a few (e.g., Kang et al.[42], Keum et al.[43]) offered plausible mechanisms derived from adjacent literature. They implicate specific brain regions in the connection between e-cigarette use and mental health, including areas central to reward processing (the ventral striatum), the stress response (amygdala), and cognitive control (the prefrontal cortex). However, this review found a lack of studies with direct mapping of these neural correlates through advanced neuroimaging in e-cigarette users. The potential role of other constituents in e-cigarette liquids, such as flavorings or solvents, on brain function also warrants investigation.

Psychological mechanisms

-

Several psychological constructs were identified as potential mediators or mechanisms explaining the link. Spears et al.[47] observed that adults with serious psychological distress were particularly inclined to use e-cigarettes for relaxation and stress management. The fear of anxiety-related bodily sensations, or Anxiety Sensitivity, showed a consistent link with both greater e-cigarette use, and more pronounced mental health difficulties[13,48]. This connects to findings on Distress Tolerance, which was found to be lower among dual users when compared to individuals who only used combustible cigarettes[13]. Salazar-Londoño et al.[49] similarly linked risky consumption patterns to symptoms of anxiety and loneliness. Emotion Dysregulation, the difficulty in managing emotional states, was similarly implicated[41]. Separately, one study found that vape users reported diminished scores on mindfulness, which was inversely related to higher rumination and less self-compassion[14]. Additionally, Wade et al.[50] suggested that distinct user profiles exist as users of combustible vs non-combustible products exhibited different mental health correlates. Wattick et al.[51] further emphasized that social motivations often drive use among college students, acting alongside adverse childhood experiences. Using vaping to manage negative emotions, what we call Coping Motives, proved to be a strong predictor for both continued e-cigarette engagement and poorer mental health trajectories[52,53].

Social mechanisms

-

Social factors, such as peer influence, prevailing social norms, and exposure to e-cigarette marketing, were often found to be associated with both e-cigarette use and mental health outcomes, with adolescents and young adults appearing particularly responsive to these external pressures[54]. Protective factors also play a role, Lilly et al.[55] found that a positive school climate was associated with fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression, functioning as a protective element against substance use. Similarly, Jones et al.[56] highlighted that higher self-efficacy and knowledge of risks were associated with a lower prevalence of vaping. The experience of social isolation and loneliness also emerged as a significant element that seemed to amplify both vaping and mental distress, and this relationship became especially pronounced during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic[52,53,57].

Moderating factors: detailed findings

Age

-

Of the various moderating factors considered, age stood out as particularly significant, as adolescents and young adults consistently demonstrated a heightened vulnerability, a finding that seems to be a product of both the unique sensitivity of the developing brain to the neurobiological effects of nicotine, and the powerful influence of social dynamics and peer groups that characterize this life stage, and in studies that specifically examined younger adolescent cohorts the role of parental practices concerning tobacco use was also identified as a relevant factor[15].

Gender

-

The role of gender as a moderating factor presented a less clear picture across the literature because while some investigations did report differences related to gender, the specific patterns were often inconsistent, with some findings suggesting that females might have a greater vulnerability to the adverse mental health effects of e-cigarettes[58], even as other studies reported stronger associations among males[27]. This divergence indicates that more research is certainly needed to clarify these gender-specific dynamics.

Co-occurring substance use

-

A very strong, and nearly ubiquitous finding across the reviewed studies, was the connection between e-cigarette use and the use of other substances, particularly alcohol and cannabis[2,23,25]. Hefner et al.[59] emphasized the need to clarify the relationships between risky alcohol use, nicotine consumption, and mental illness to guide intervention efforts. Adzrago et al.[60] further identified that frequent e-cigarette use was significantly associated with concurrent alcohol and cannabis consumption, as well as stress related to social distancing. This pattern of polysubstance use was consistently linked to more significant mental health problems, a reality that naturally raises questions about whether specific combinations of substances might produce unique or synergistic effects on an individual's psychological well-being.

Type of substance vaped

-

The specific substance being vaped seems to matter quite a bit. Studies that made a distinction between nicotine and cannabis often discovered stronger links between vaping cannabis and later mental health issues[17,40]. This suggests THC's psychoactive properties likely have a considerable, and maybe even separate, role beyond the impact of nicotine alone.

Dual vaping

-

The behavior of vaping both nicotine and cannabis, often called 'dual vaping', was reported to be quite widespread. In one study, for instance, more than a quarter (26.1%) of the participants said they had done this in the last 30 d[16]. Two notable predictors were associated with increased odds of dual-vaping: identifying as male, and reporting self-rated anxiety[16].

-

The findings from this scoping review indicate a significant relationship between e-cigarette use and mental health conditions. It seems to be a two-way connection. Each issue appears to elevate the risk of the other. Because of this reciprocal nature, it is quite clear that interventions focusing on just one of these areas would probably not be effective.

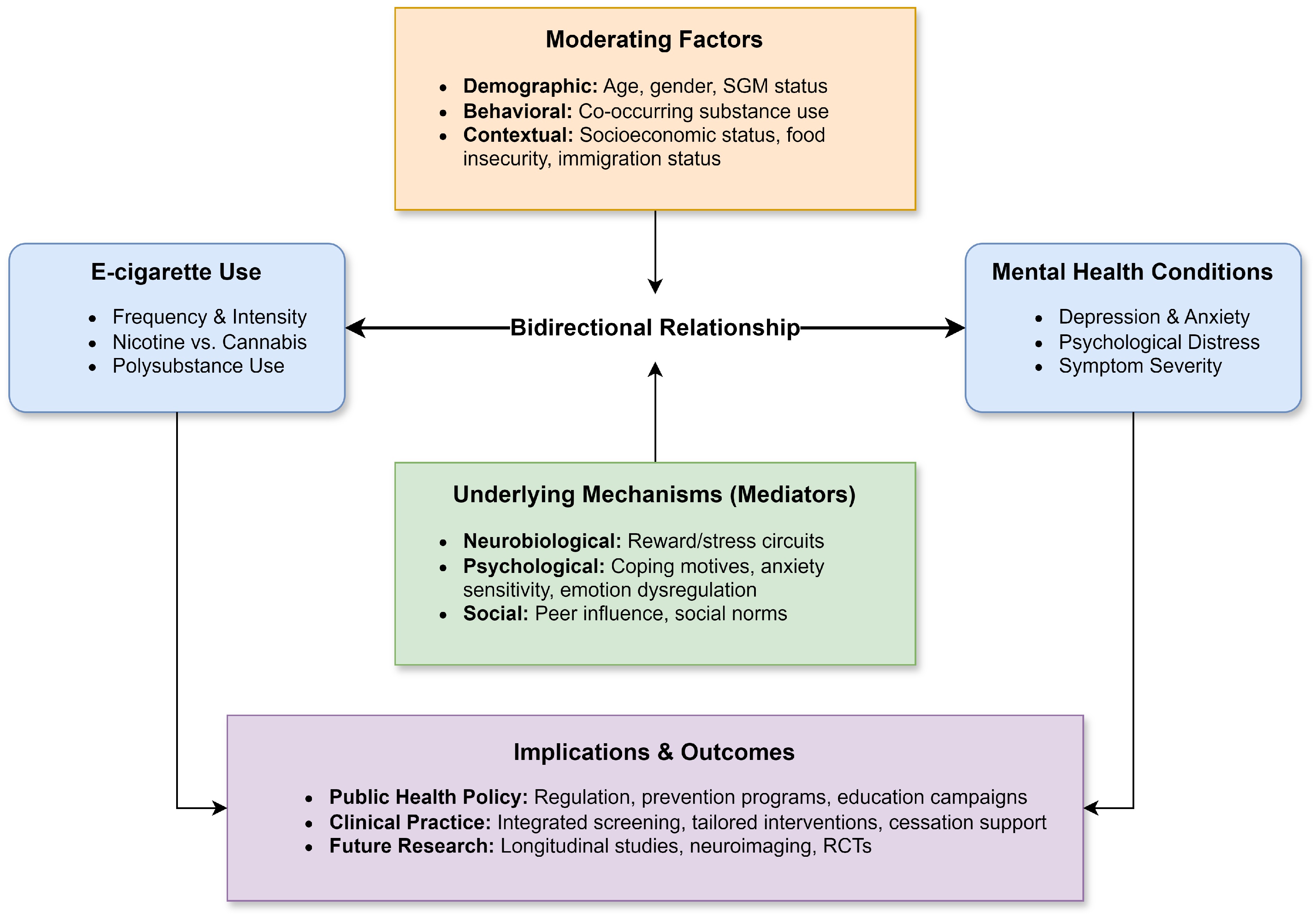

The complex interplay of factors identified in this review can be synthesized into a conceptual framework (Fig. 2), which depicts the bidirectional association between e-cigarette use and mental health, its underlying mechanisms, moderating factors, and related implications.

Implications for public health policy

-

The results of this review point toward several potential directions for public health policy and practice.

First, the association between youth vaping and psychological distress should inform regulatory frameworks, which might include modifying advertising, restricting flavored products, or adjusting the legal age of purchase. Because the evidence is largely correlational, these policies can be framed as precautionary measures to mitigate potential harm while research on causality continues.

Second, a further implication is the potential utility of public education initiatives that disseminate information concerning the mental health correlates of e-cigarette use, not just the established physical risks, and the effectiveness of such campaigns may depend on their design, which would need to be tailored for specific demographic groups such as SGM individuals who appear to be disproportionately affected by these co-occurring issues[26].

Third, educational settings represent another important venue for prevention where integrated programs could simultaneously address both e-cigarette use and mental wellness, with a focus on promoting adaptive coping strategies, building resilience, and reducing barriers to help-seeking for mental health support.

Finally, the evidence underscores the importance of integrating mental health and substance use services given that the high prevalence of co-occurring conditions documented in this review[13,22] lends credence to models of care that address these issues concurrently a model which would logically include routine screening for both e-cigarette use and mental health concerns across diverse settings such as primary care mental health clinics and educational institutions.

Implications for clinical practice

-

The findings also have equally significant implications for clinical practice.

The findings have direct implications for clinical practice. It would appear that incorporating routine screening for e-cigarette use is a logical component of intake and ongoing assessment, especially when working with adolescent and young adult populations, a screening that would need to move beyond a superficial level to explore the specifics of use, including frequency and product type, alongside any co-occurring substance use.

It follows then that interventions would need to be adapted to the specific needs and context of the individual, which might involve a multi-faceted approach, one that could integrate cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to enhance coping skills with motivational interviewing to build intrinsic motivation for change, while also considering the appropriateness of pharmacological options like nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or medications for any co-occurring mental health conditions.

Given the complexity that often surrounds these issues, interprofessional collaboration becomes a key element of effective care, where coordinated efforts involving school counselors', social workers, or addiction specialists can address the multiple facets of an individual's situation, and in those cases, where individuals present with severe or complex co-occurring disorders, a referral to a specialized treatment program is often the indicated clinical pathway.

Limitations of the review

-

Several limitations inherent in this scoping review warrant acknowledgment. First the search strategy, although robust within the confines of Scopus and Web of Science, did not extend to other significant databases like PsycINFO and Embase, nor did it include a search of grey literature or preprints, a decision that might have resulted in the omission of some relevant studies, particularly from the psychological sciences, and could have introduced a publication bias favoring English-language evidence from high-income countries. Another limitation is tied to the nature of a scoping review itself which, by design does not include a formal appraisal of the methodological quality of the included articles, a key distinction from a systematic review, and this leaves open the possibility that biases within the primary studies could exert an unexamined influence on the overall synthesis. The findings are also shaped by the geographical distribution of the source material, as nearly half of the studies (n = 26) originated from the US, a factor that could limit the generalizability of these findings to other cultural or regulatory contexts. Finally, a substantial portion of the reviewed literature relied on cross-sectional designs, which by their nature preclude causal inference, and many of the individual studies had their own specific limitations, such as small sample sizes or significant heterogeneity in the measurement of both vaping behaviors and mental health outcomes, which made direct comparisons across studies a challenging endeavor.

Addressing the research gaps

-

While the present analysis clarifies several facets of the connection between e-cigarette use and mental health, it also throws into sharp relief the areas where knowledge is lacking, a primary unresolved issue being one of directionality that is whether an individual's mental health status predisposes them to using e-cigarettes, or if the use of these products contributes to the onset or worsening of such conditions, a question that can only be answered through studies that follow individuals over several years. A significant part of this effort must also involve expanding the geographical scope of research, because the current evidence base is heavily skewed towards North American samples, which limits the generalizability of findings, as the interplay of substance use, mental health, and policy is deeply influenced by local contexts, a point underscored by studies examining these factors in countries like Turkey[8]. It is also an open question whether research that uses much larger samples, or perhaps methods that involve in-depth interviews with individuals experiencing addiction, would provide a different understanding of the matter.

Beyond the sequence of events, the underlying mechanisms are not well understood, and while neurobiological work, particularly through neuroimaging would be helpful for identifying the specific neural systems involved in this relationship, a purely biological explanation is not likely to be sufficient because a complete picture requires capturing the lived experiences of individuals, and qualitative methods are uniquely suited to exploring their personal motivations, their perceived barriers, and the facilitators for behavioral change. It is worth speculating that the high concentration of US-based studies may be due to factors such as higher research funding from institutions like the NIH, higher prevalence rates of e-cigarette use, making it a public health priority, or a specific regulatory environment that has drawn scientific scrutiny.

This entire line of inquiry must ultimately serve a clinical purpose, and so the development of sound prevention and treatment approaches is a clear priority that requires more intervention research, with strong designs like randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to determine which strategies are actually effective. Evaluating integrated interventions that address both substance use and mental health at the same time, is a critical next step, and these studies must include long-term follow-up to assess if outcomes are maintained over time.

Looking further into the future, research could also investigate novel adjunctive therapeutic pathways for depression. For instance it could be productive to explore treatments that target underlying biological factors like oxidative stress, which substance use might exacerbate, but this is, of course, a speculative proposal and would require its own dedicated program of investigation.

-

The association between e-cigarette use and mental health appears to be a significant public health issue, and this scoping review has organized the evidence for what is a strong association, and a potential feedback loop between chemical dependence and psychological distress. It follows from this that addressing one without confronting the other is an incomplete strategy. The clear implication is the need for an integrated approach, one that binds policy to prevention and clinical practice, which would seem to be less an aspirational goal and more a remedial necessity, an approach that requires a working coalition between researchers, clinicians', educators, and policymakers. Given the consistency of these findings, especially for adolescents and young adults, continued research can and should be paralleled by pragmatic action, and while more evidence is certainly needed to establish causality, the current data present a substantial case for moving forward with coherent and decisive public health interventions.

-

This study constitutes a review of previously published literature and does not involve any new research with human participants or animals. Consequently, formal ethical approval from an Institutional Review Board or ethics committee was not required for this work.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: initial conceptualization, design of the review, and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript: Looti M; literature search, study selection, data extraction, and contributed to critical revision of the manuscript: Looti M, Abd-alazim M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this review are available within the article and from the original publications cited. Additional details regarding the study selection process can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors wish to express their gratitude to their colleagues at the University of Kerbala for their insightful contributions during the development of this manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Completed PRISMA-ScR Checklist.

- Supplementary File 1 Detailed search string used for database selection.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Looti M, Abd-alazim M. 2025. The interplay of electronic cigarette use and mental health: a scoping review of bidirectional associations, underlying mechanisms, and moderating factors. Journal of Smoking Cessation 20: e012 doi: 10.48130/jsc-0025-0012

The interplay of electronic cigarette use and mental health: a scoping review of bidirectional associations, underlying mechanisms, and moderating factors

- Received: 17 June 2025

- Revised: 27 October 2025

- Accepted: 11 December 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: The concurrent rise in e-cigarette use and mental health challenges among youth necessitates a clear synthesis of evidence. This scoping review systematically maps recent literature on their relationship. Following the Arksey and O'Malley framework, and PRISMA-ScR guidelines, Scopus and Web of Science were searched for studies published between 2019 and 2024, yielding 54 studies from 1,853 records. The present analysis revealed a consistent co-occurrence, with higher rates of e-cigarette use among individuals with mental health conditions and vice versa. Several longitudinal studies reported prospective associations in both directions, suggesting a bidirectional link, though causal inference remains limited. Implicated mechanisms include neurobiological pathways (reward/stress circuits), psychological factors like using vaping to cope, and social influences, with age, gender, substance use, and socioeconomic factors acting as moderators. These findings underscore the need for integrated public health strategies combining prevention, regulation, and clinical care for vulnerable populations. Further longitudinal research is crucial to elucidate causal pathways and underlying mechanisms.

-

Key words:

- Electronic cigarettes /

- Vaping /

- Mental health /

- Depression /

- Substance use /

- Anxiety /

- Dual use