-

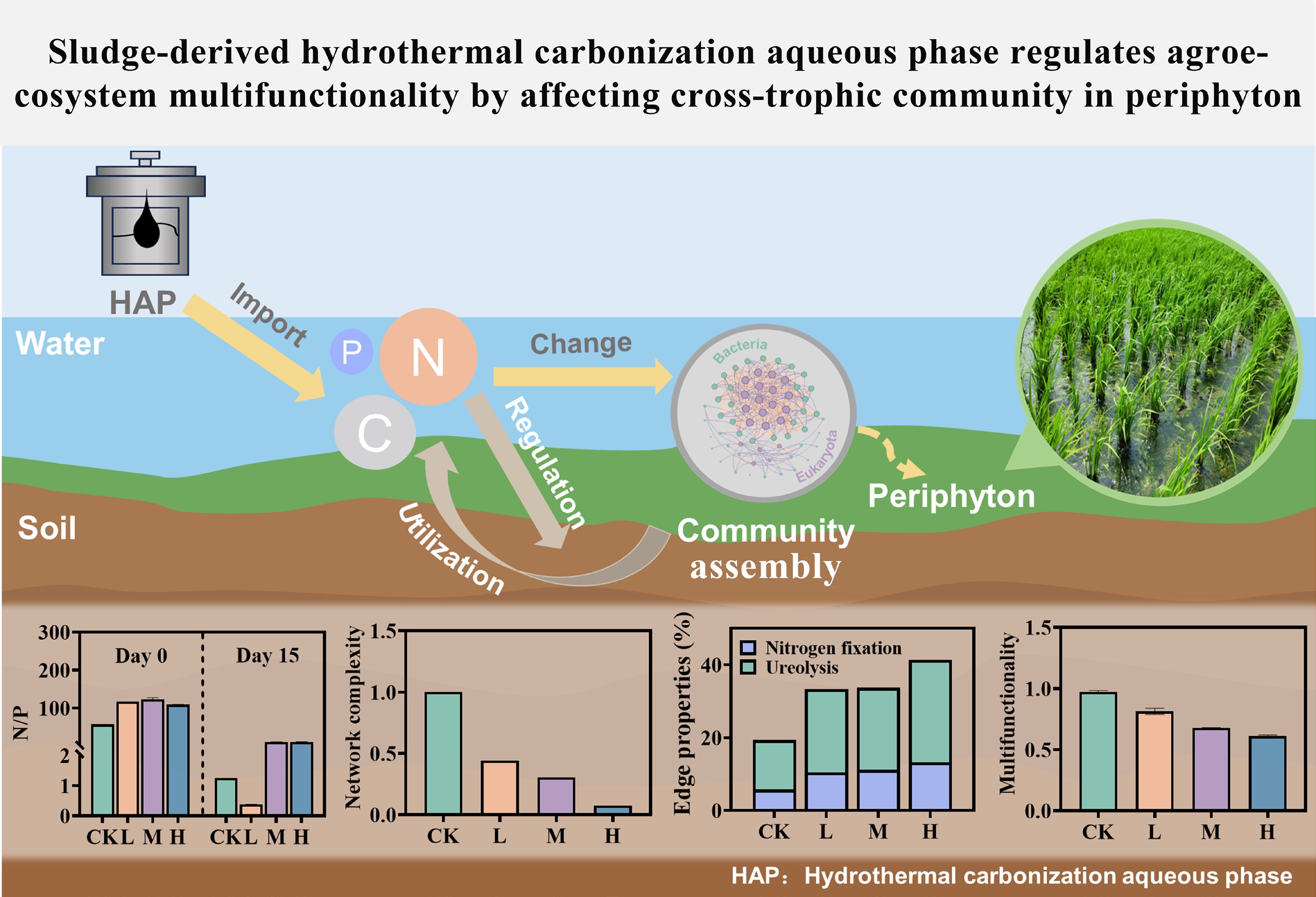

Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) has emerged as a highly efficient technology for treating high-moisture organic waste, such as sludge from municipal wastewater treatment, due to its ability to bypass feedstock drying, operate under mild conditions, and produce hydrochar suitable for use as fuel or soil conditioner[1,2]. With increasing practical implementation, HTC technology is increasingly recognized as a viable solution to the growing challenge of sludge management in wastewater treatment[3−5]. However, a major byproduct of the process is the hydrothermal carbonization aqueous phase (HAP), into which 20%–50% of the organic matter, and 60%–80% of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) are solubilized during the reaction[6]. The effective utilization of this nutrient-rich HAP remains a challenge to the full industrialization of HTC.

Despite this challenge, HAP exhibits significant potential for agricultural reuse. Its high organic matter content and N richness enable its use as a soil amendment, with studies demonstrating that appropriate application can reduce fertilizer usage and ammonia volatilization, while improving crop yield and quality[7−9]. Additionally, HAP serves as a valuable nutrient source for microalgae cultivation[10], offering a sustainable pathway for nutrient recovery and contaminant removal strategies, widely regarded as promising for circular resource management[11]. Nevertheless, HAP may exert both beneficial and adverse effects on agroecosystems, necessitating a thorough evaluation of its environmental implications. To date, however, a comprehensive understanding of HAP's impact on agroecosystems remains limited and fragmented[12−14].

Periphyton, a complex and multi-trophic assemblage of autotrophic and heterotrophic microorganisms (e.g., algae, bacteria, and fungi), forms structured biofilms where these organisms are interconnected and thrive within a matrix of extracellular polymeric substances, organic matter, and debris[15]. Ubiquitous in aquatic environments such as paddy fields and lakes, this biofilm ecosystem is not only a key driver of primary production but also plays essential roles in nutrient cycling, food web dynamics, and the removal of contaminants from the water column[16]. Moreover, periphyton exhibits high sensitivity to environmental perturbations, dynamically adjusting its biomass, community structure, and metabolic activity in response to stressors. As such, it is widely employed as a sensitive bioindicator in environmental monitoring, ecotoxicological assessments, and ecological remediation[17−19]. In particular, periphyton biomass serves as a reliable bioindicator for assessing dissolved organic matter content and nutrient characteristics within shallow water bodies[20]. Previous studies have shown that periphyton can facilitate the degradation of HAP in paddy systems, concurrently undergoing structure reorganization of its microbial network, thereby demonstrating adaptive responses to HAP exposure[21−23]. These findings position periphyton as a sensitive and ecologically relevant model system for assessing the impacts of HAP. Crucially, there is still insufficient systematic evidence connecting HAP-driven shifts in periphyton community structure to broader shifts in ecological multifunctionality, microbial network interactions, and metabolic pathways.

To address these knowledge gaps, a microcosm experiment was conducted to systematically examine the effects of gradient HAP inputs on periphyton, with a focus on the following primary objectives: to quantify the reshaping of taxonomic and trophic structure; to evaluate the resulting alterations in interdomain microbial networks; and to assess the ultimate impact on agro-ecosystem multifunctionality. By integrating high-throughput sequencing, network analysis, and metabolic prediction, this study aims to elucidate the mechanistic links between HAP exposure and ecological functional outcomes, providing a scientific basis for risk assessment and sustainable application of HAP in agriculture.

-

Sludge was collected from a municipal wastewater treatment plant (Nanjing, China). The solid-to-liquid ratio was adjusted to 1:10, and the mixture was treated in a 10 L hydrothermal reactor at 220 °C for 1 h. After cooling to room temperature, solid-liquid separation was performed. The liquid product, designated as sludge-derived HAP, was stored in a cool place for subsequent use. The fundamental physicochemical properties of the HAP are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Experimental design for periphyton incubation

-

Periphyton was collected from a lake in Nanjing (China). Periphyton inoculum was prepared and pre-cultured according to the method described in a previous study[23]. As outlined in Supplementary Table S2, HAP and water were mixed at different ratios to form three treatments labeled H, M, and L. The concentration gradient was established based on methodologies reported in previous studies[24]. Periphyton inoculum was then added to each group. A control group (CK) containing only pond water was also established. Each treatment was conducted in triplicate.

The cultivation process was carried out in an illuminated incubator at 28 °C under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. During cultivation, water samples were periodically collected and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. The pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) of the filtered water were measured using a pH meter and a DO meter, respectively. Total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and chemical oxygen demand (COD) were determined following standard methods[25]. The concentration of NH4+-N was measured using Nessler's reagent spectrophotometry. At the end of the incubation period, periphyton samples were collected, dried at 105 °C, and weighed to determine biomass.

DNA extraction and sequencing

-

Periphyton samples were sent to Personalbio Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China) for microbial community diversity profiling and library construction. The V5–V7 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified using primers 799F (AACMGGATTAGATACCCK) and 1193R (ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC). The V9 region of the eukaryotic 18S rRNA gene was amplified using primers Euk1391f (GTACACACCGCCCGTC) and EukBr (TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC).

DNA fragments from the microbial communities were subjected to paired-end sequencing on the Illumina platform. The Good's coverage index for all samples exceeded 99.5%, indicating high sequencing coverage and reliability. QIIME2 (2019.4) was used for annotation, analysis, clustering, and taxonomic classification of species at consistent sequencing depths. Relative abundance and diversity indices were calculated using the Greengenes database for bacteria and a customized database for eukaryota. Fungal trophic modes and bacterial ecological functions were annotated using the FUNGuild and FAPROTAX databases, respectively. Metabolic pathways of bacterial and eukaryotic communities were predicted using PICRUSt2 (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States).

Microbial community profiling

-

The microbial α-diversity was calculated using the 'vergan' package. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis distance was applied to assess changes in microbial community structure across groups. Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) was also performed based on Bray-Curtis distance using the 'microeco' package. Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis was conducted with the 'microeco' package. The influence of various environmental factors on community composition was quantified using the 'rdacca.hp' package. To obtain a single index reflecting multitrophic diversity (multidiversity), the biodiversity characteristics were combined by averaging the standardized scores [using minimum-maximum (min-max) normalization] of Chao1 indices across bacterial and eukaryotic species[26].

Statistical and ecological network analyses

-

The normalized stochasticity ratio (NST) was used to estimate the relative importance of stochastic processes in community assembly. The NST value for each treatment was computed with the 'NST' package[27]. An NST value of 0.5 served as the threshold to distinguish between more deterministic (< 0.5), and more stochastic (> 0.5) assembly processes. Niche breadth was measured using Levins' index, implemented via the 'spaa' package[28].

Interdomain bipartite networks were constructed for each group using the 'ggClusterNet' package, and visualized in Gephi 0.10.1 to assess cross-trophic microbial interactions. Topological properties of the networks—including average degree, connectivity, average path length, and network density—were computed with the 'igraph' package. To reflect overall network complexity, a composite index was derived by averaging the normalized scores (ranging from 0 to 1) of these topological metrics. Notably, the average path length (reflecting network sparsity) was inverted before normalization[29].

Ecosystem multifunctionality calculation

-

To emphasize the influence of the incubation process on ecosystem functioning, an ecosystem multifunctionality (MF) index was constructed based on processes related to nutrient cycling and growth metabolism, including the concentrations of DO and NH4+-N, the nitrogen-to-phosphorus (N/P) ratio, the concentration of COD, and biomass. These metrics are widely used to evaluate ecological quality in natural aquatic ecosystems[30]. Notably, to characterize the balance between periphyton nitrogen-phosphorus demand and environmental supply, the stoichiometric ratio of N/P was employed instead of absolute N and P concentrations. Following recommendations in the literature, pH was excluded from the MF calculation as it is not a strong proxy for ongoing ecosystem processes[31]. Furthermore, to avoid interference from nutrients inherently present in HAP, the MF index was computed using the relative change ratio, rather than absolute concentrations, for water physicochemical properties. An exception was made for DO, which was treated separately due to its distinct response pattern characterized by photosynthesis-driven increases. This procedure was implemented using the 'multifunc' package.

All statistical analyses were performed in R 4.3.2. Data visualization was carried out using GraphPad Prism 9.5 and Adobe Illustrator 2025.

-

The addition of HAP rapidly altered the physicochemical properties of the water. Throughout the periphyton incubation, water quality indicators exhibited distinct dynamics. The introduction of HAP influenced the initial DO and pH levels of the system. DO was sharply suppressed, especially in the H group (minimum: 0.19 mg/L), while pH remained around 8 (Supplementary Fig. S1a, S1b). During incubation, DO levels gradually increased due to natural re-aeration and oxygen production from periphyton photosynthesis. However, the recovery of DO was slower in treatments with higher HAP content. After day 9, both DO and pH in all treatments recovered to levels comparable to those in the CK.

In contrast to the stable, low N levels in the CK group, the addition of HAP introduced a substantial initial load of N, as evidenced by the sharp rise in both NH4+-N and TN concentrations. These nitrogen concentrations decreased progressively over time (Supplementary Fig. S1c, S1d). By day 15, NH4+-N concentrations had decreased by 90.7% (L), 51.6% (M), and 38.7% (H) compared to their initial values. TN concentrations showed similar intergroup variation patterns to NH4+-N. TP trends and concentrations in the HAP-treated groups were similar to those in CK, with values peaking on day 9 before declining to levels comparable to or even lower than those in CK (Supplementary Fig. S1e).

COD levels showed a fluctuating downward trend (Supplementary Fig. S1f). The COD in the CK, L, and M groups decreased to low values on day 3, while the H group reached its lowest value on day 6. All groups peaked on day 9 before declining again. By day 15, COD had decreased by 76.9% (CK), 56.9% (L), 64.0% (M), and 55.7% (H), respectively.

Diversity and species composition of periphyton

-

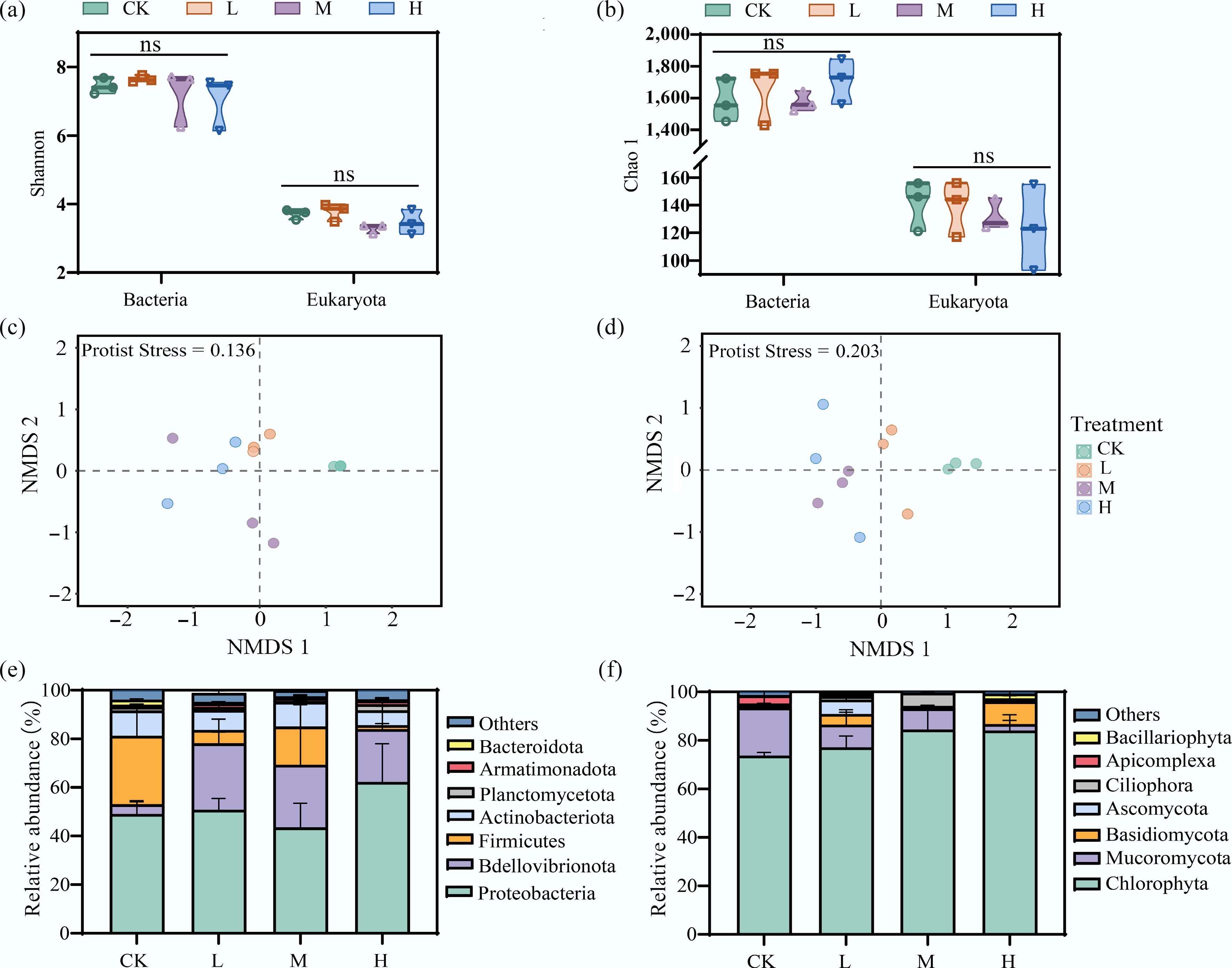

Periphyton biomass decreased with increasing HAP concentration, indicating that HAP significantly inhibited periphyton growth and reproduction (Supplementary Fig. S2). The α-diversity of bacterial and eukaryotic species in periphyton samples was reflected using the Shannon and Chao1 indices. Bacterial diversity indices were higher than those of eukaryotes. However, no significant differences were observed in the diversity indices of either bacteria or eukaryotes among treatment groups at the end of the incubation period (p > 0.05), suggesting that periphyton α-diversity was not affected by HAP during incubation (Fig. 1a, b). Therefore, subsequent analyses focused on β-diversity. NMDS analysis revealed that both bacterial and eukaryotic communities clustered according to HAP treatment, with clear separations observed between treatment groups and the control (Fig. 1c, d). Higher HAP concentrations resulted in greater distances between sample points and lower similarity, indicating that HAP concentration was a key factor altering the β-diversity of periphyton species.

Figure 1.

HAP alters the community structure but not the alpha diversity of periphyton. (a), (b) Alpha diversity indices (Shannon and Chao1) of bacterial and eukaryotic communities across treatments. 'ns' indicates no significant difference. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination showing changes in the (c) overall bacterial, and (d) eukaryotic community structure. Relative abundance of dominant (e) bacterial, and (f) eukaryotic phyla.

To further analyze the impact of HAP on periphyton species composition, highly abundant taxa (relative abundance > 1% for bacteria and > 0.7% for eukaryotes) were compared (Fig. 1e, f). At the phylum level, the dominant bacterial groups included Proteobacteria, Bdellovibrionota, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Planctomycetota, Armatimonadota, and Bacteroidota. Among these, Proteobacteria remained the most abundant phylum across all treatments, with no significant difference induced by HAP addition (p > 0.05). The abundance of Bdellovibrionota increased under HAP influence (p < 0.05), rising from 4.0% (CK) to 27.4% (L), 25.8% (M), and 21.7% (H), respectively. The abundance of Firmicutes decreased with HAP input, particularly in the H group, where it declined significantly from 28.2% (CK) to 1.6% (p < 0.05). The overall relative abundance of Actinobacteria was less affected by HAP.

As shown in Fig. 1f, the main eukaryotic taxa included Chlorophyta, Mucoromycota, Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, Ciliophora, Apicomplexa, and Bacillariophyta. Chlorophyta was the absolutely dominant group across all treatments, consistent with previously reported periphytic algal community structures in freshwater systems[32]. HAP addition further increased its relative abundance. The abundance of Mucoromycota decreased significantly under HAP influence (p < 0.05), declining from 19.7% (CK) to 9.4% (L), 8.7% (M), and 2.7% (H), respectively. The abundance of Basidiomycota increased significantly under high HAP input, rising from 0.4% (CK) to 9.4% (H) (p < 0.05), while Ascomycota responded positively only to low-level HAP input. LEfSe analysis showed that at a threshold of 4, HAP addition led to the emergence of biomarker species in both bacterial and eukaryotic communities that were distinct from those in the CK group, further demonstrating the capacity of HAP to reshape the relative species composition of periphyton (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Community assembly and differentiation of periphyton

-

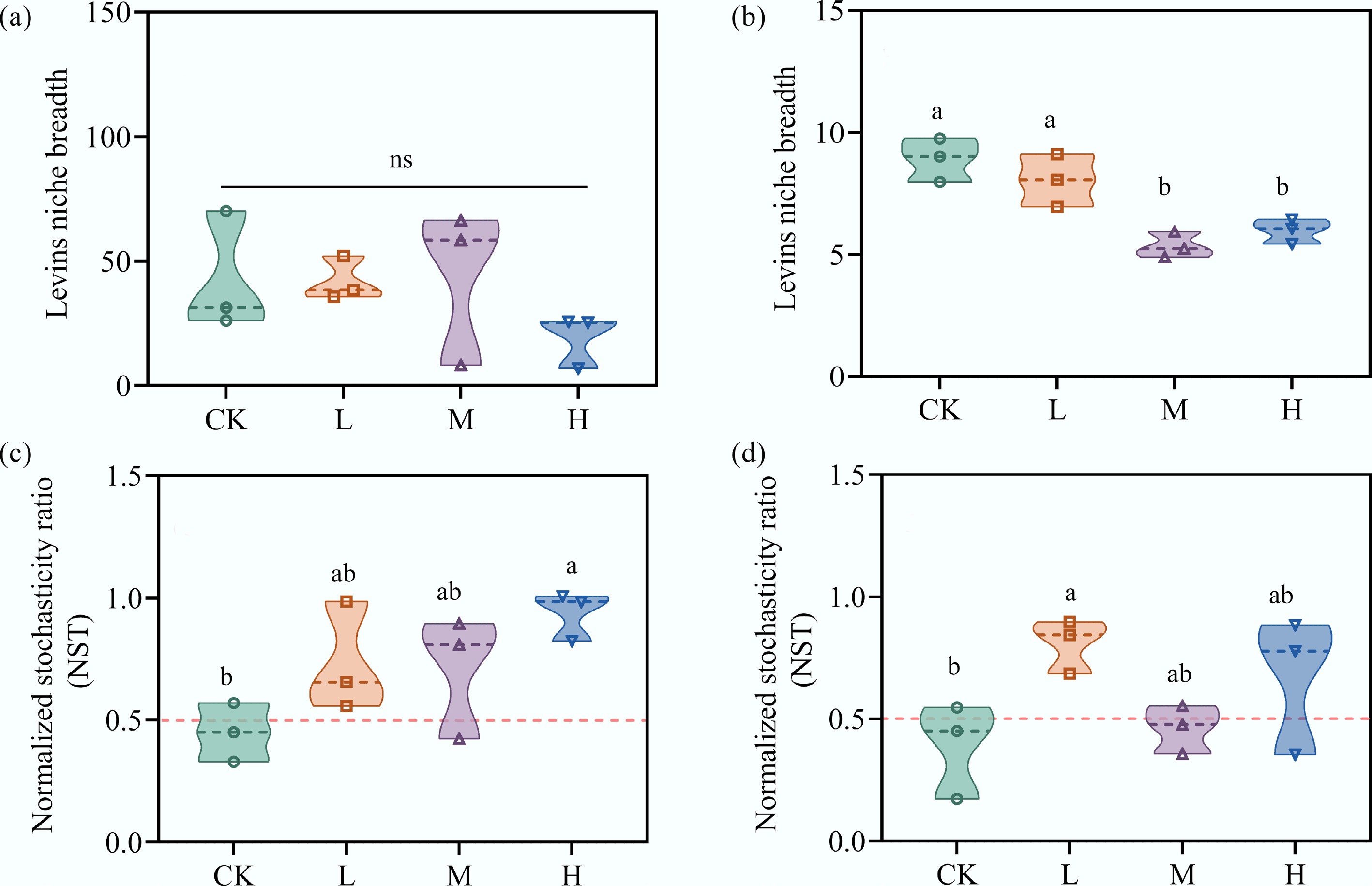

Niche breadth varied among species and across treatment groups (Fig. 2a, b). The niche breadth of eukaryotic species in the periphyton ranged between 4.90 and 9.8, while bacterial species exhibited a broader range. With increasing HAP concentration, the niche breadth of both eukaryotic and bacterial species decreased to varying degrees, with eukaryotic species showing a significant difference compared to CK (p < 0.05). This observation indicates that eukaryotes exhibited a narrower niche breadth, which aligns with the established ecological principle that reduced niche breadth limits resource access and increases susceptibility to environmental stressors[33,34]. NST was used to characterize the response of bacterial and eukaryotic community assembly to HAP stress. In CK, the mean NST value for bacterial communities was 0.45, indicating that deterministic processes dominated. As HAP concentration increased, the NST values of bacterial communities gradually rose above 0.5, reflecting an increased importance of stochastic processes (Fig. 2c). Similarly, low and high HAP inputs led to elevated NST values in eukaryotic communities, although the addition of medium HAP concentration appeared to reduce the role of deterministic processes (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

HAP narrows species' niche breadth and increases stochasticity in community assembly. The average Levins' niche breadth of (a) bacterial, and (b) eukaryotic communities. The normalized stochasticity ratio (NST) of (c) bacterial, and (d) eukaryotic communities. An NST > 0.5 indicates the dominance of stochastic processes.

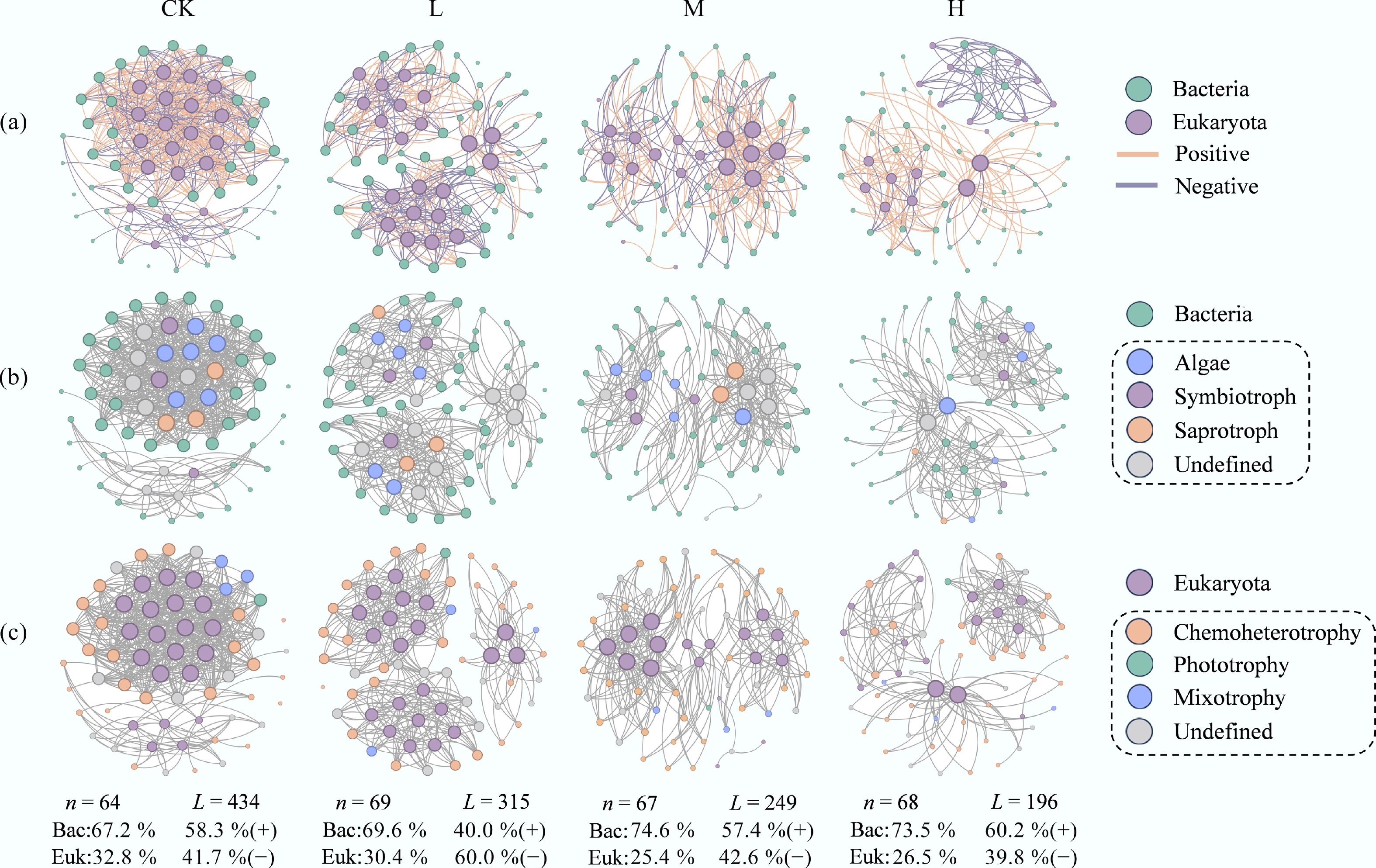

To further clarify the impact of HAP on interactions across trophic levels within the periphyton network, interdomain bipartite networks of bacteria and eukaryota were constructed for each group, and their structural and topological indices were computed (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Table S3). Low to medium HAP inputs increased the proportion of negative connections in the network, indicating enhanced competition between bacteria and eukaryotes. The proportion of eukaryotic nodes decreased with increasing HAP concentration. Moreover, in HAP-addition groups, network connectivity, average degree, and network density were all lower than those in CK. These results imply poorer adaptability of eukaryotes to HAP, reduced resistance of bacterial-eukaryotic interactions to external stress, and a decline in network complexity.

Figure 3.

HAP simplifies the architecture of bacteria-eukaryota interdomain networks. (a) Bipartite networks for each treatment. Node color represents taxonomy at the genus level, and size is proportional to node degree. Edges represent significant positive (green) and negative (red) correlations. (b), (c) Major trophic modes of (b) eukaryota, and (c) bacteria are annotated by the FUNGuild and FAPROTAX databases, respectively.

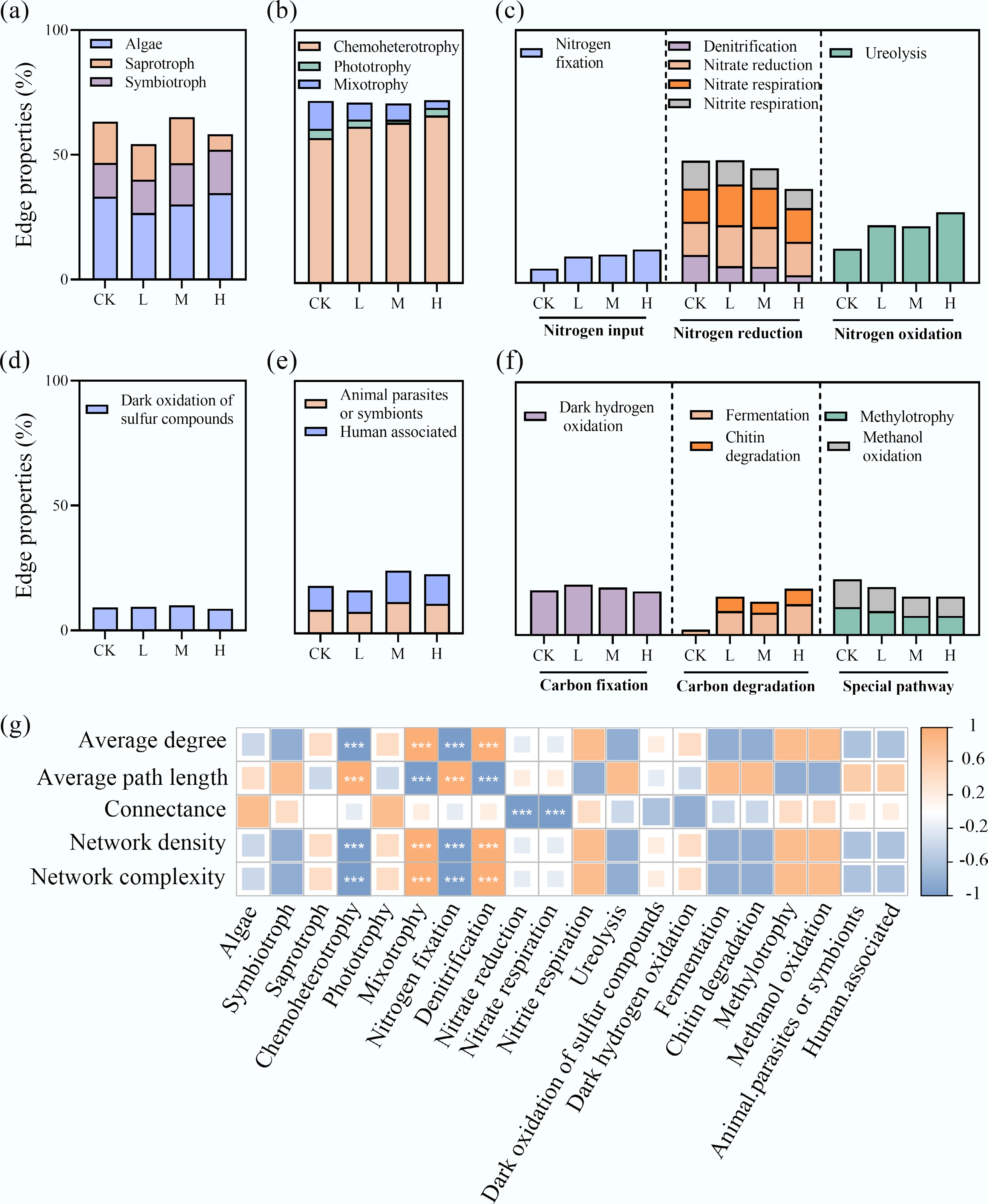

FUNGuild and FAPROTAX tools were used to annotate the trophic modes and ecological functions of eukaryotic and bacterial nodes within the networks, respectively (Fig. 3b, c). The proportions of connections associated with different trophic types differed among groups (Fig. 4a–f). Specifically, at 'highly probable' and 'probable' confidence levels, HAP addition increased the proportion of symbiotic nutrition in eukaryotes, while reducing the weight of saprotrophic modes. Chemoheterotrophic bacteria dominated across all networks, and HAP treatment further strengthened this dominance while reducing the connection weight of mixotrophic species. Additionally, HAP increased the connection proportion of nitrogen-fixing bacteria but decreased those involved in nitrate reduction, nitrogen respiration, and denitrification. The weights of fermentative bacteria and chitin-degrading bacteria also declined. Correlation analysis revealed that the connection weights of these functional groups were significantly correlated with interdomain network complexity (p < 0.001), indicating that bacterial trophic types and ecological patterns play crucial roles in periphyton network interactions (Fig. 4g).

Figure 4.

HAP induces a functional reorganization of the periphyton network. The proportion of connections (edges) associated with different (a) bacterial ecological functional groups, and (b)–(f) eukaryotic trophic modes in the interdomain networks. (g) Correlation analysis between the connection proportions of key functional groups and overall network complexity indices.

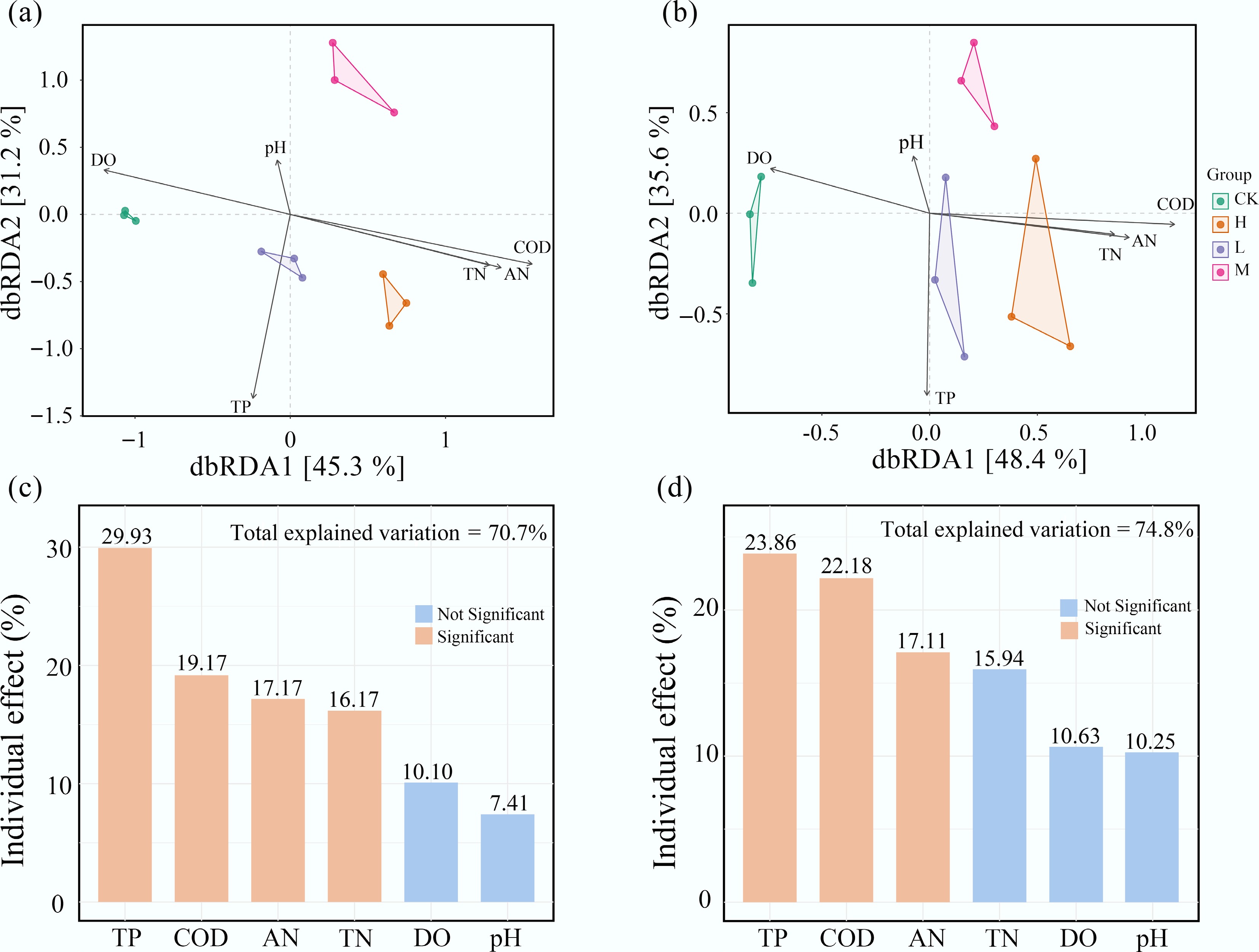

Environmental factors, including TP, COD, TN, and AN, also explained a considerable portion of the phylogenetic variation in the periphyton community. Hierarchical partitioning analysis showed that these environmental factors accounted for over 70% of the variance in both eukaryotic and bacterial communities. HAP-induced differences in periphyton composition were significantly correlated with changes in water nutrient levels (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Water nutrient levels are the primary environmental drivers of periphyton community composition. Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) of (a) bacterial, and (b) eukaryotic communities. The individual impact of each environmental factors on (c) bacteria, and (d) eukaryota is calculated based on the 'rdacca.hp' package.

Changes in periphyton multifunctionality

-

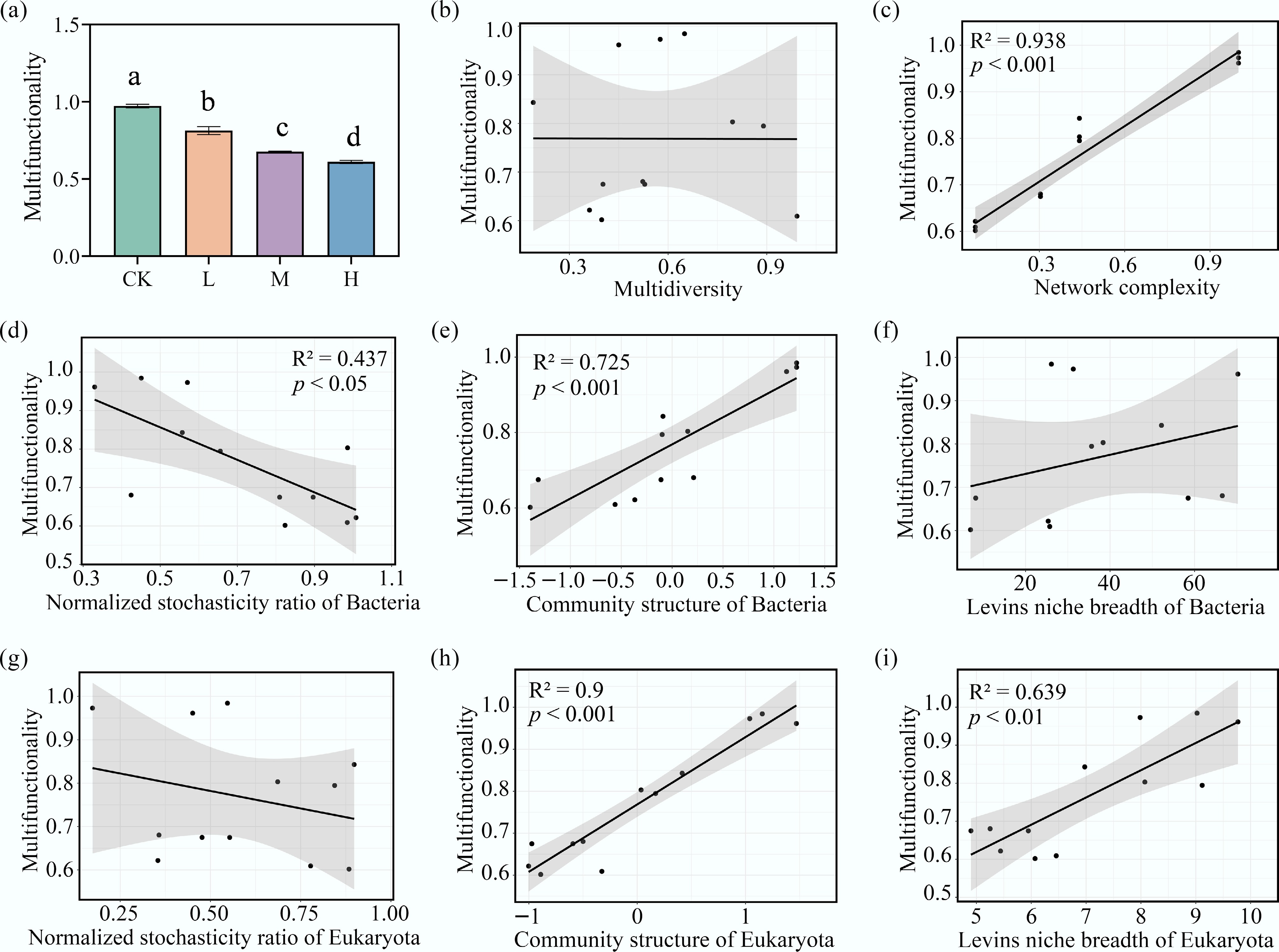

The mean multifunctionality (MF) of periphyton was calculated. Compared to the CK, HAP addition significantly reduced periphyton MF (p < 0.05), with greater reductions observed at higher HAP concentrations (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Key microbial properties driving the decline of ecosystem multifunctionality under HAP stress. (a) The ecosystem multifunctionality (MF) index across treatments. Linear relationships between MF and the (b) multidiversity, (c) the network complexity, the normalized stochasticity ratio (NST) of (d) bacteria, and (g) eukaryota, the community structure (PCoA axis1) of (e) bacteria, and (h) eukaryota, and the Levins' niche breadth of (f) bacteria, and (i) eukaryota.

Several microbial indicators showed significant correlations with periphyton MF (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6). The community structures of both eukaryotes and bacteria exhibited highly significant positive effects on MF (p < 0.001). Bipartite network complexity was also significantly positively correlated with MF (R2 = 0.938, p < 0.001). The niche breadth of eukaryota had a significant positive impact on MF. Eukaryotic NST was not linearly related to MF, whereas bacterial NST was significantly negatively correlated with MF (R2 = 0.437, p < 0.05). Multidiversity, calculated based on the richness (Chao1) of bacterial and eukaryotic species, showed no linear relationship with periphyton MF.

Prediction of metabolic pathways in periphyton

-

Metabolic pathways of bacterial and eukaryotic species in the periphyton were predicted using the MetaCyc database, with significantly different pathways (p < 0.05, ANOVA) across groups being selected for further analysis (Supplementary Figs S4, S5). Bacterial biosynthetic pathways exhibited the highest relative abundance in all treatments. Specifically, the relative abundances of pathways related to nucleoside and nucleotide biosynthesis, metabolic regulators, and secondary metabolite synthesis decreased with HAP addition. These pathways generally showed significantly positive correlations with bacterial niche breadth and periphyton multifunctionality, and were negatively correlated with the normalized stochasticity ratio (NST) of bacteria (p < 0.05). A similar trend was observed in other metabolic categories, such as inorganic nutrient metabolism, C1 compound assimilation and utilization, formaldehyde oxidation I, and isopropanol biosynthesis. The reduction in the relative abundance of these pathways may reflect enhanced inhibitory effects of HAP on bacteria, directly influencing species turnover and functional expression within the bacterial community. Notably, HAP addition appeared to enhance the expression of certain bacterial metabolic pathways, including the glyoxylate cycle and amino acid degradation.

In eukaryotic communities, pathways for the generation of precursor metabolites and energy ranked second in relative abundance after biosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. S5). HAP addition reduced the expression of respiratory and electron transfer pathways, while promoting increased relative abundance in glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway. These significant alterations indicate that HAP also profoundly affects metabolic processes in eukaryotic species within the periphyton, thereby influencing community assembly. Correlations between eukaryotic NST values and metabolic pathways were generally weak, suggesting that stochastic processes play a minor role in shaping the metabolic functional expression of eukaryotes.

-

Physicochemical properties of water are critical indicators for assessing periphyton responses to external stressors and are essential for understanding the interactions between periphyton and the ecosystem. Among them, pH is an important factor regulating nutrient availability and may serve as one of the driving forces for microbial communities in ecosystems[35]. The results indicate that metabolic and reproductive activities of periphyton led to a noticeable increase in water pH during cultivation. This effect can be primarily attributed to the phototrophic algae that dominate periphytic biofilms, whose intense photosynthetic activity consumes dissolved CO2 and releases oxygen, thereby elevating the pH of the water[36,37]. Consistent with this mechanism, Lu et al.[38] observed a marked increase in pH in periphyton-containing waters, which promotes the co-precipitation of phosphorus. In another homothermal incubation experiment, Beheshti et al.[39] observed increased soil pH after 50 d of periphyton treatment. In the present study, no significant differences in pH were observed among treatment groups at the end of the cultivation period (Fig. 1a). A possible explanation is that HAP addition did not significantly affect the intensity of photosynthesis in periphyton.

In this study, the TP content in water increased initially and then decreased. During the early incubation stage, P limitation may have led to the decomposition of periphyton, releasing assimilated and stored soluble P back into the water[40]. Over time, the elevated pH will accompany the precipitation and fixation of P in nutrient-rich water, which is considered an important mechanism by which periphyton mitigates P loss[38]. Across different HAP concentrations, periphyton demonstrated certain N removal capabilities from the sludge-derived HAP. A previous study has shown that periphyton plays a key role in the biogeochemistry of N in aquatic environments, exhibiting potential for intercepting and accumulating N[41]. Due to the stress effects of HAP on periphyton, the percentage reduction in TN and NH4+-N decreased with increasing HAP concentration. Similarly, high concentrations of HAP also adversely affected the removal of COD by periphyton. Nevertheless, within the incubation period, all treatment groups achieved reduction rates of over 45% for both TN and COD, indicating considerable short-term tolerance and adaptability of periphyton to HAP. A previous study has suggested that the functional diversity of periphyton is an important factor enabling its rapid adaptation to and efficient utilization of nutrients in high-nutrient water[42]. In summary, the tolerance of periphyton to HAP across concentration gradients can buffer the environmental risks posed by HAP to the ecosystem, yet it is insufficient to fully counteract them.

HAP addition leads to differences in periphyton species composition

-

Understanding the species composition and community differences of periphyton is crucial for studying its ecological functions. The observed decrease in periphyton biomass with increasing HAP concentration indicates strong inhibitory effects of HAP on periphyton growth. After incubation, no significant differences in the α-diversity of bacterial and eukaryotic species were detected among groups, possibly due to the high diversity of species within periphyton, particularly rare taxa[43]. However, significant dissimilarities in community composition between samples suggest that HAP induced community reassembly and shifts in dominant species, likely attributable to altered ecological niches[44]. For bacteria, HAP promoted an increase in Bdellovibrionota, which are obligate predators known to prey on other bacteria for growth[45]. For eukaryotic species, HAP suppressed the activity of Mucoromycota, a group of saprophytic fungi that typically occupy nutrient-rich niches and utilize nutrients efficiently[46]. Under HAP stress, both bacterial and eukaryotic species exhibited specialized resource use strategies, leading to an increase in the abundance of specialist taxa. This may represent an adaptive response to harsh conditions, resulting in reduced metabolic flexibility at the taxonomic level and a consequent decrease in overall niche breadth for both bacteria and eukaryotes. Narrow niche breadth may also increase the vulnerability of interspecific relationships within periphyton[28]. For instance, HAP addition reduced interdomain network complexity (Supplementary Table S3), consistent with findings by Yang et al., who reported a significant decline in prokaryotic network density in periphyton under anthropogenic nutrient enrichment[47]. Given the naturally low nutrient levels in the water, periphyton's reliance on HAP as a singular nutrient source may exacerbate community homogenization, undermining community stability and the maintenance of complex systems (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Multi-factor induced assembly processes in periphyton communities

-

HAP also induced differences in cooperation among species of different trophic types within periphyton, which is an important factor altering community assembly processes. At the taxonomic level, high functional redundancy resulting from vast species diversity may interfere with the interpretation of community differences[48]. Groupings based on trophic modes and ecological functions are often more sensitive to environmental changes, providing deeper insights into how HAP concentration gradients drive community assembly. Ureolysis and biological N fixation are considered major pathways for periphyton to assimilate external N sources and achieve N accumulation[41]. In this study, the connection weights of these functional nitrogen-accumulating bacteria in the interdomain network increased with higher HAP concentrations. Meanwhile, chitin-degrading bacteria facilitate the conversion of nitrogenous organic matter into nitrate[49]. These enhanced interdomain cooperative relationships may help maintain relatively stable N accumulation pathways in periphyton, offering clear adaptive advantages under high-nutrient HAP inputs. Despite overall constraints on interdomain cooperation under HAP stress, periphyton may achieve functional compensation by altering the weight distribution of trophic guilds within the network. This allows periphyton to sustain nutrient uptake and fixation capacities under environmental pressure, avoiding community collapse.

Previous studies have categorized the core mechanisms of microbial community assembly into deterministic and stochastic processes[50]. Due to their larger body size, eukaryotic communities exhibit lower stochasticity in assembly than bacteria, as reflected in their lower NST values. Under HAP addition, stochastic processes gradually dominated bacterial community assembly. The imbalanced nutrients and potential toxic substances introduced by HAP may stress the environment and act as a filter during periphyton community assembly. The remaining species face reduced competition, potentially enhancing their ability to cope with environmental stress and increasing the relative importance of stochasticity in shaping the final community composition. Moreover, the introduction of additional carbon sources may promote community homogenization and enhance bacterial dispersal capacity[51,52]. A previous study has also reported that increased nutrient availability can introduce greater stochasticity into microbial community assembly[53].

The assembly of bacterial and eukaryotic communities in periphyton is also influenced by various environmental factors. Previous research has shown that the physicochemical properties of the growth substrate can lead to differences in community assembly[54]. However, the characteristics of the overlying water should not be overlooked, particularly the availability of N and P, which may determine periphyton community composition[55]. In this study, TP and TN had the highest explanatory power for both bacterial and eukaryotic communities, supporting the important role of N and P in shaping periphyton community structure. The extremely high TN content in HAP may cause an imbalance in N/P ratios. In the absence of substrate-mediated regulation, periphyton may experience P limitation[56].

In summary, the assembly of the periphyton community was co-driven by cross-trophic collaborations and nutrient characteristics of the overlying water. Throughout this process, the compensatory reorganization of the community to safeguard core functions, such as N metabolism, was a key factor in its adaptability to HAP.

HAP leads to reduced periphyton multifunctionality through simplified community interactions

-

The results indicate significant positive correlations between community structure, interdomain network complexity, and periphyton multifunctionality (Fig. 6, p < 0.01), highlighting the importance of community assembly and interspecies cooperation in expressing multifunctionality[57]. Furthermore, eukaryotic niche breadth had a more pronounced impact on multifunctionality, suggesting that the resource acquisition capacity of eukaryotes is closely linked to the maintenance of community functions. Broader niche breadth may serve as a predictor of core species involved in expressing diverse traits[29]. Under HAP stress, broad-niche species may disproportionately influence periphyton multifunctionality[58]. Numerous studies have identified species diversity as a key driver of multifunctionality in many terrestrial ecosystems, with increased diversity enhancing ecosystem multifunctionality[59]. Although this linear relationship was not significant in the present study, the contribution of species diversity to multifunctionality should not be overlooked, as such relationships may be modulated by abiotic factors such as environmental conditions. Additionally, the contribution of protists within periphyton was not considered in this study and should be addressed in future research.

HAP also influenced multifunctionality by reshaping the metabolic pathways of periphyton. Significant suppression of bacterial biosynthetic pathways—particularly those related to nucleotides, secondary metabolites, and inorganic nutrient metabolism—weakened core functions generally associated with broad niche breadth. The decline in the abundance of these pathways was closely linked to reduced ecological multifunctionality, indicating an overall loss of functional regulation. In contrast, the suppression of respiratory pathways and enhancement of glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathways in eukaryotes suggest a compensatory yet less efficient energy maintenance strategy. Notably, the relative abundance of amino acid degradation pathways was negatively correlated with multifunctionality in both bacteria and eukaryotes. One possible explanation is that HAP inhibited bacterial synthetic capacity while forcing eukaryotes into a metabolically simplified state. This may reflect a commonly adopted strategy to adapt to environmental stress.

Overall, the complexity of community interactions, rather than species diversity alone, served as the primary driver of multifunctionality. Moreover, metabolic pathways appear to provide a robust predictive framework for assessing the ecological multifunctionality of periphyton.

-

This study demonstrates that when sludge-derived HAP serves as a potential nutrient source, it may also act as a significant environmental stressor to periphyton. Periphyton's adaptability and nutrient removal capacity make it promising for cleaning HAP-input water. However, the environmental risks of using HAP in agriculture must be carefully assessed because HAP impairs ecosystem functioning by altering species composition, narrowing niche breadth in key taxa, and simplifying interdomain ecological networks. These changes directly reduce ecosystem multifunctionality. Under the anthropogenic stress posed by HAP, microbial community structure and interactions are more reliable predictors of function than species richness alone. Although periphyton adapts by reorganizing trophic guilds and shifting its metabolism, this response cannot fully offset the functional losses under high HAP levels.

The microcosm experiment, while controlled, may not fully capture the complexity of natural agricultural systems; therefore, the long-term effects of repeated HAP application on periphyton and agriculture ecosystem stability should be investigated more deeply in future research.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/aee-0025-0012.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Huifang Xie: writing−review and editing, supervision; Xudong Zhong: writing−original draft, visualization, methodology, investigation, data curation; Bingyu Wang: writing−review and editing, supervision, conceptualization, funding acquisition, software, resources, project administration, methodology; Ke Sun: investigation; Wenlu Tian: methodology, investigation; Yanfang Feng: writing−review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFD1700300), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42107398 and 42277332). Yanfang Feng thanks the support of the '333' High-level Talents Training Project of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. 2022-3-23-083).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

HAP reduces the ecosystem multifunctionality of periphyton by simplifying interdomain network architecture.

Cross-trophic community interactions are the primary driver of periphyton multifunctionality under HAP stress.

Periphyton exhibits functional compensation to HAP by reorganizing trophic guilds and shifting metabolic pathways.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Xudong Zhong, Bingyu Wang

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong X, Wang B, Sun K, Xie H, Tian W, et al. 2025. Sludge-derived hydrothermal carbonization aqueous phase regulates agro-ecosystem multifunctionality by affecting cross-trophic community in periphyton. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e011 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0012

Sludge-derived hydrothermal carbonization aqueous phase regulates agro-ecosystem multifunctionality by affecting cross-trophic community in periphyton

- Received: 31 October 2025

- Revised: 28 November 2025

- Accepted: 05 December 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) is an efficient sludge conversion technology that generates a nutrient- and dissolved organic matter-rich aqueous phase (HAP) with potential for agricultural reuse. Given its intended application, evaluating the ecological effects of HAP on soil-water interface bio-processes in agroecosystems is critically important. This study employed periphyton as a model system to assess its functional responses to sludge-derived HAP at different concentrations, innovatively investigating the role of cross-trophic interactions as a central mediator. Physicochemical parameters were systematically monitored throughout the cultivation, as well as the bacterial and eukaryotic communities. The results demonstrate that periphyton maintained notable nutrient removal capacity even under high HAP stress, with removal rates remaining up to 55% for COD, and 35% for NH4+-N at the highest HAP input level. However, this capacity decreased with increasing HAP concentration. While microbial α-diversity remained stable, HAP significantly reshaped the species composition and community structure of both bacteria and eukaryota (p < 0.05), primarily driven by shifts in trophic guilds and environmental factors. It was found that HAP reduced the periphyton's ecological multifunctionality by narrowing its niche breadth and simplifying the interdomain network architecture, highlighting a previously underappreciated mechanism. Notably, the findings also reveal that HAP induced adaptive regulatory and functional compensation strategies in periphyton, maintaining nutrients removal through reorganization of trophic guilds and functional groups. This study provides novel insights into the ecological risk assessment of HAP and supports the development of sustainable management strategies for its agricultural application.