-

Strawberries and other crops cultivated in hydroponics in greenhouse environments typically exhibit enhanced mineral profiles and additional nutritional advantages compared to those grown in soil-based settings[1−3]. Hydroponics is the most intensive cultivation method that makes efficient use of water, minerals, and space. It enables precise control over plant growth conditions, which facilitates the investigation of specific parameters[4]. However, abundant nutrient supply in hydroponics may cause plants to uptake excessive nutrients[5]. In addition, over uptake of these expensive nutrient solutions can significantly increase the production cost. Thus, optimization of nutrient use in hydroponics is crucial for its sustainability[6].

Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill., an insect pathogenic fungus of the Clavicipitaceae family, serves as a biocontrol agent against a broad range of insect pests[7]. They can also live in soil as a saprophyte and colonize the plant rhizosphere as a plant symbiont. The symbiotic interaction with plants results in multiple benefits for plants, including improved growth, insect pest protection, and improved nutrient uptake[8,9]. Previous studies demonstrated that inoculating plant roots with B. bassiana significantly improves plant health[10,11]. Treated cotton[12,13], cabbage[14], common bean[15], maize[16], and rice[17] plants exhibit higher dry biomass, advanced developmental stages, increased flower production, improved growth, prolonged flowering periods, and enhanced stress tolerance. B. bassiana stimulates root growth, enabling the plant to absorb more nutrients from distant soil regions[18−20]. This Hypocrealean fungus also produces secondary metabolites such as phenolic acids, benzopyranones, steroids, and quinones, which contribute to the promotion of plant growth[21].

The potential of B. bassiana for improving strawberry cultivation has been explored by several researchers. While primarily used for pest management due to its pathogenic effects on mites and insects, B. bassiana also exhibits endophytic behavior by colonizing strawberry plants. Research has shown that B. bassiana can persist in various plant tissues for up to nine weeks, potentially aiding plant health through mycorrhizal activity and improving water and nutrient absorption[22,23]. In a study comparing B. bassiana with a soil-based microbial commercial product, the fungus-treated strawberry plants consistently exhibited better health ratings than untreated controls or those treated with the commercial product. Although not statistically significant, these observations highlight the potential positive impact of B. bassiana on strawberry plant growth and health[22]. Additionally, the dual action of B. bassiana as both a biocontrol agent against pests and a plant growth bio-stimulant in strawberry has been demonstrated[24,25]. In a previous study by the same authors, it was revealed that seed priming with B. bassiana increased antioxidants and secondary metabolites in rice leaves and induced root proliferation[17]. However, no comprehensive study is available regarding the effect of B. bassiana inoculation on strawberry growth, yield, and nutritional and biochemical traits of strawberry fruits. It has many positive impacts on plants, and may be useful as a bioinoculant to improve important physiological and biochemical traits of strawberries, making the hydroponic system more efficient at utilizing nutrients. Therefore, the present research aimed to evaluate the efficacy of B. bassiana on growth, yield, fruit nutritional quality, and nutrient use of strawberry in a coconut substrate-based soilless hydroponics.

-

Thai strawberry plantlets (Fragaria × ananassa Duch. Var. Sonata) were used as a model plant for this study. The pure culture of B. bassiana isolate BeauA1 was obtained from our culture collection. This isolate was originally recovered from local agricultural soil samples and was molecularly characterized, with ITS and TEF sequence data deposited in GenBank under Accession Nos OP784783 and OP785285, respectively[26].

Hydroponic cultivation of strawberry

Cleaning and sterilization of the roots of strawberry plantlets

-

Roots of the strawberry plantlets were first cleaned with running water and then sterilized by immersing them in 5% (v/v) Clorox solution (0.375% NaOCl final concentration) for 3 min, and 0.1% (w/v) Dithane M-45 (Bayer CropScience Ltd., Dhaka, Bangladesh) fungicide solution for 3 min, respectively. Then, plantlets were again washed three times with sterile distilled water. A volume of 100 µL of the last washed water was plated on agar to check for any contamination.

Fungal inoculum preparation

-

Spores of B. bassiana were collected from a 14-day-old fungal culture and diluted in Tween-80 (0.05%) solution to achieve 1 × 108 conidia/mL and stored at 4 °C for 3 weeks prior to use.

B. bassiana treatment of strawberry plantlets

-

After root sterilization, a nursery was prepared in 32 plastic pots (7.62 cm diameter) using 500 g of a mixture of coco dust and perlite (3:1 ratio in v/v) in each pot. Then strawberry plantlets were transferred to the pots (one plantlet/pot). To ensure the appropriate and uniform development of the plantlets, 800 mL of water was provided to each pot, divided into two equal splits (morning: 400 mL, afternoon: 400 mL), starting on the day of potting, and continuing for up to one week. Then the plantlets were removed from the pots, and the root zones were gently cleaned with running water. Roots of half of the total plantlets (16 plantlets) were dipped into 500 mL (@ 108 spores/mL) B. bassiana spore suspension at a time for colonization purposes, and the remaining half (another 16 plantlets) into 500 mL Tween-80 solution for 24 h. After 24 h, plantlets were potted again in the same nursery pots by following the same nursery preparation procedure. This activity was carried out once during the nursery periods, and then the strawberry plantlets were transplanted into large plastic pots (15 L). The 1/4th strength of standard Enshi-shoo solution[27] is recommended for growing strawberry plants hydroponically[28−29]. In this study, four different concentrations viz. 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% of the recommended concentration of Enshi-shoo nutrient solution were used for the nutrition of the plants treated with and without B. bassiana (BB). There were eight treatments: (a) 100% NS – BB (100% nutrient solution (NS); (b) 100% NS + BB; (c) 75% NS – BB; (d) 75% NS + BB; (e) 50% NS – BB; (f) 50% NS + BB; (g) 25% NS – BB, and (h) 25% NS + BB. One liter of nutrient solution (NS) as per treatment condition was applied at the base of the plants twice a day (morning: 500 mL, afternoon: 500 mL), and 250 mL of water was applied in each pot at 7 d intervals regularly from the day of potting up to transplanting into a large pot.

Transplantation of strawberry plantlets into large pots and management of nutrients and water

-

After 15 d, the plants were transferred into larger plastic pots (15 L) (one plantlet/pot) for better growth and yield. The individual pot was filled with 4.0 kg of potting mixture of coco dust and perlite (3:1 ratio in v/v), and placed in a greenhouse with a prevailing temperature of about 25 °C/18 °C (day/night). The light intensity inside the greenhouse ranged from 1,000 to 1,200 lux. A volume of 2.0 L of each concentration of solution was applied in each pot in two equal splits (morning: 1.0 L, afternoon: 1.0 L), and 1.5 L of water was applied in each pot at 7 d intervals from the day of potting up to harvesting.

Harvesting strawberry fruits

-

Strawberry fruits were harvested individually throughout the growing season when they became ripe. After nine weeks, on the day of final harvesting, the fruits were harvested, followed by the removal of the entire plant from the potting mixture. Two young lateral roots (approx. 1–2 g) from each plant were immediately separated carefully without causing any damage to the plants and preserved in zipper bags for further assessment of B. bassiana colonization in roots. After that, shoots and roots of plants were separated and washed with distilled water three times, and air dried.

Confirmation of B. bassiana colonization in strawberry roots

-

The collected roots were surface sterilized, and a 3 cm long root segment from the middle portion was taken and cut into 6 × 6 mm segments. The root sections were placed in SDAY medium supplemented with antibiotics (2 mg/L of each antibiotic: penicillin, streptomycin, and tetracycline) as described by Parsa et al.[30]. Fungal growth was checked daily for 5 d, and B. bassiana was identified by its characteristic, compact, and white-colored mycelium, and percent colonization was calculated.

Determination of growth parameters of strawberry plants

-

Shoot and root length, plant height, crown diameter, number of leaves, maximum leaf length, maximum leaf width, and shoot and root fresh weight were determined immediately after harvesting. For the determination of dry weight, all the samples (shoots and roots) were oven-dried at 80 °C for 72 h, and then weighed. The number of flower clusters/plant was assessed through a manual counting process before the arrival of fruits. The number of fruits and fruit weight were determined immediately after every harvest using a digital weighing scale throughout the season up to the final harvest. Then, fruit quality was assessed in the laboratory.

Soil-Plant Analysis Development (SPAD) value estimation of strawberry plant leaf

-

The SPAD value was recorded by a SPAD meter (SPAD-502, Minolta Co. Ltd., Japan) on the day of final harvesting. The SPAD value was measured from each replication of treatments from the third leaflet.

Calculation of the insect infestation percentage in strawberry plants

-

Strawberry plants were mainly infested by spider mite and also leaf rollers were observed in the greenhouse conditions. The overall insect infestation percentage was determined manually at the third week of plant growth by counting the total number of insect-affected leaves and dividing them by the total number of leaves, followed by multiplying the results by 100, both in the control and treated plants.

Strawberry fruit quality determination

pH and Brix determination

-

The pH and the soluble solids of strawberry fruit samples were determined using a pH meter (LE pH Electrode LE438-IP67, Mettler Toledo, Hong Kong) and by refractometry in a digital refractometer (Reichert AR200), respectively.

Total sugar determination

-

For total sugar, total reducing sugar, titratable acidity, and ascorbic acid determination, 50 mL stock solutions were prepared from 10 g of each fruit sample of each replication. After that, stock solutions were centrifuged (2,817 × g at 4 °C for 20 min), and supernatants were transferred to 100 mL conical flasks and sealed with aluminum foil paper. Total sugar was estimated following the method of Pavlović et al.[31] using Bertrand A, Bertrand B, and Bertrand C solutions. At first, 5 mL of sample solution from each 50 mL stock solution was taken into a 50 mL conical flask, and two drops of concentrated HCl were added to each sample solution. Then, all 50 mL conical flasks were heated in a sand bath at 125 °C for 15 min, and left to cool at room temperature. After cooling, 10 mL of each Bertrand A (0.16 mol/L CuSO4.5H2O) and Bertrand B (1.09 mol/L of NaOH and C4H4O6KNa.4H2O mixture) solutions were added to each 5 mL sample solution. Then, flasks were heated again in a sand bath at 125 °C for 30 min and kept overnight to cool to room temperature. The next day, 10 mL of Bertrand C (0.33 mol/L of Fe2[SO4]3 and H2SO4 mixture) solution was added to each solution, and then titrated with 0.03 mol/L KMnO4 solution. After titration, results were documented and calculated.

Total reducing sugar estimation

-

Total reducing sugar was estimated following the method of Bertrand[32] using Bertrand A, B, and C solutions. Ten mL sample solutions from each 50 mL stock solution, each of 10 mL Bertrand A (0.16 mol/L CuSO4.5H2O) and Bertrand B (1.09 mol/L of NaOH and C4H4O6KNa·4H2O mixture) solutions were taken into each 50 mL conical flask. After that, all 50 mL conical flasks were heated in a sand bath at 125 °C for 30 min, and kept overnight to cool and precipitate nutrients in the conical flasks. The next day, the supernatants were discarded carefully, keeping the precipitations. Each precipitation (accumulated nutrients under flask conditions) was rinsed three times with distilled water to prevent chemical adherence to the sample. Then, Bertrand C (0.33 mol/L of Fe2[SO4]3 and H2SO4 mixture) solution was added to each sample and titrated with 0.03 mol/L KMnO4 solution. After titration, results were documented and calculated as g/100 g FW.

Titratable acidity determination

-

Titratable acidity determination was carried out following the method of Cardwell et al.[33]. Three drops of phenolphthalein indicator were added to each 10 mL of sample solution in a 50 mL conical flask, mixed well, and titrated with 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution, and the results were recorded and calculated.

Ascorbic acid (Vit-C) determination

-

Ascorbic acid content was determined following the method of Dioha et al.[34] with slight modifications. 5 mL KI (0.3 mol/L), 2 mL CH3COOH (98.99%), and 2 mL C12H22O11 (0.06 mol/L) were added to each 10 mL stock solution (0.05 g of ascorbic acid in 100 mL of water) was taken into a 100 mL acetic acid-washed conical flask. Finally, samples were titrated with 0.02 mol/L KIO3 solution, and results were recorded (mg/100 g FW) and calculated using the following equation:

$ \mathrm{Vitamin\; C}\ \left(\mathrm{mg}/100\mathrm{g}\right)=\frac{\mathrm{Volume}\ \text{iodine}\left(\text{mL}\right)\times\ 0.88\ \mathrm{Dilution}\ \mathrm{factor\times\ 100}\ }{10\ \mathrm{g}\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{fresh}\ \text{sample}} $ Total phenolic content estimation

-

A sample of 0.5 g strawberry fruit from each replication was homogenized with 12.5 mL (100%) CH3OH, followed by water bath treatment at 30 °C for 2.5 h. Then, centrifugation was carried out at 2,817 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were collected in glass tubes, and sealed with aluminum foil paper and preserved in a refrigerator at −20 °C for further determination of total phenolics, flavonoids, and antioxidant content following different methods. Total phenolic content was determined following the method of Singleton et al.[35]. To estimate total phenolics, 0.5 mL of 10% (0.2 N) Folin-Ciocalteu's reagent was added to each standard and sample tube of 1 mL supernatant, and was then vortexed for 10 s, covered, and incubated for exactly 15 min at room temperature. Next, 2.5 mL of 700 mM Na2CO3 solution was added to each solution, and the mixture was again vortexed, covered, and incubated at room temperature for 2 h in the dark room. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 765 nm against a blank sample using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–Vis, Japan). The measurements were compared to a standard curve of gallic acid (C6H2[OH]3CO2H) solutions (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 100 µg/mL) and expressed as micrograms of gallic acid equivalents per gram ± standard deviation (SD).

Total flavonoid content determination

-

Total flavonoid content was determined following the methods of Pourmorad et al.[36], and Nyangena et al.[37]. Initially, 0.4 mL of 100% CH3OH, 0.1 mL of 10% AlCl3·6H2O, and 0.1 mL 1.2 mol/L CH3COONa were added with 0.1 mL of supernatant. Then the mixture was vortexed, covered, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in a dark room. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 420 nm against a blank sample using spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–Vis, Japan). The measurements were compared to a standard curve of quercetin (C15H10O7) solutions prepared by serial dilutions using methanol (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 µg/mL) and expressed as micrograms of quercetin equivalents per gram ± standard deviation (SD).

Total antioxidant activity (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, DPPH radicle scavenging assay) determination

-

Total antioxidants were assessed following the method of Nyangena et al.[37]. Initially, 1.0 mL supernatant from each replication and standard was taken in test tubes. A volume of 1.0 mL of methanol (instead of plant extract) was taken in another test tube. Then, 3 mL of 0.2 mM DPPH solution was added to each test tube (the DPPH solution with corresponding solvents [i.e., without plant material] served as the control, and methanol as the blank). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 5 min. Then, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm wavelength using spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–Vis, Japan). The measurements were compared to a standard curve of ascorbic acid (C6H8O6) solutions (0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL), and expressed as percentage ± standard deviation (SD).

β-carotene determination

-

β-carotene was estimated spectrophotometrically according to the method of Nagata & Yamashita[38]. At first, 10 mL of mixed solution of acetone:hexane (4:6) (v/v) was added to each 1 g of fruit tissue, ground with a mortar pestle, and the supernatant was filtered in a test tube, followed by sealing the tube with aluminum foil paper (this process was followed for every replication). Then, absorbances were measured with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–Vis, Japan) (calibrated with acetone: hexane solution) at 663, 645, 505, and 453 nm wavelengths.

Anthocyanin estimation

-

Anthocyanins were estimated spectrophotometrically according to the methods of Murray & Hackett[39], and Hughes & Smith[40]. Initially, 1.0 g of fruit tissue from each replication was taken in an ice-cold glass vial. 5 mL extraction solution (methanol : 6M HCl : water = 70:7:23 (v/v/v)) was added to each fruit tissue vial, and only the extraction solution was added to another vial. This extraction solution without fruit tissue was used as a blank. Then vials were made airtight and kept at 4 °C in the dark for 24 h. After 24 h, 2 mL of solution from the vial was taken into a centrifuge tube, and 2 mL of distilled water was added to each tube. Then, 2 mL chloroform was added to each vial to separate anthocyanin (insoluble in chloroform) from chlorophylls. After that, mixtures were centrifuged for 15 min at 1,957 × g at 4 °C. After centrifugation, 3 mL of the top layer (containing anthocyanin) was taken in a glass cuvette. Then, absorbance was measured at a 530 nm wavelength using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–Vis, Japan).

Mineral content determination

-

The contents of K, Ca, Fe, and Zn were determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS) (PinAAcle 900H; PerkinElmer, USA), following the method of Tee et al.[41].

Experimental design and statistical analysis

-

An experiment was conducted following completely randomized design (CRD) with four replications, in the greenhouse. There were two groups of strawberry plants, one with and one without BB inoculation. The collected data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the significant variations among the treatments were analyzed according to the least significant difference test at p < 0.05 using RStudio (v 1.1.383). Four biological replicates (n = 4) were used to obtain the values (mean ± SEs) for each treatment, and are presented in the figures and tables. Multivariate analysis was carried out using the hierarchical clustering method to reveal the treatment-variable interactions using the 'pheatmap' package in RStudio.

-

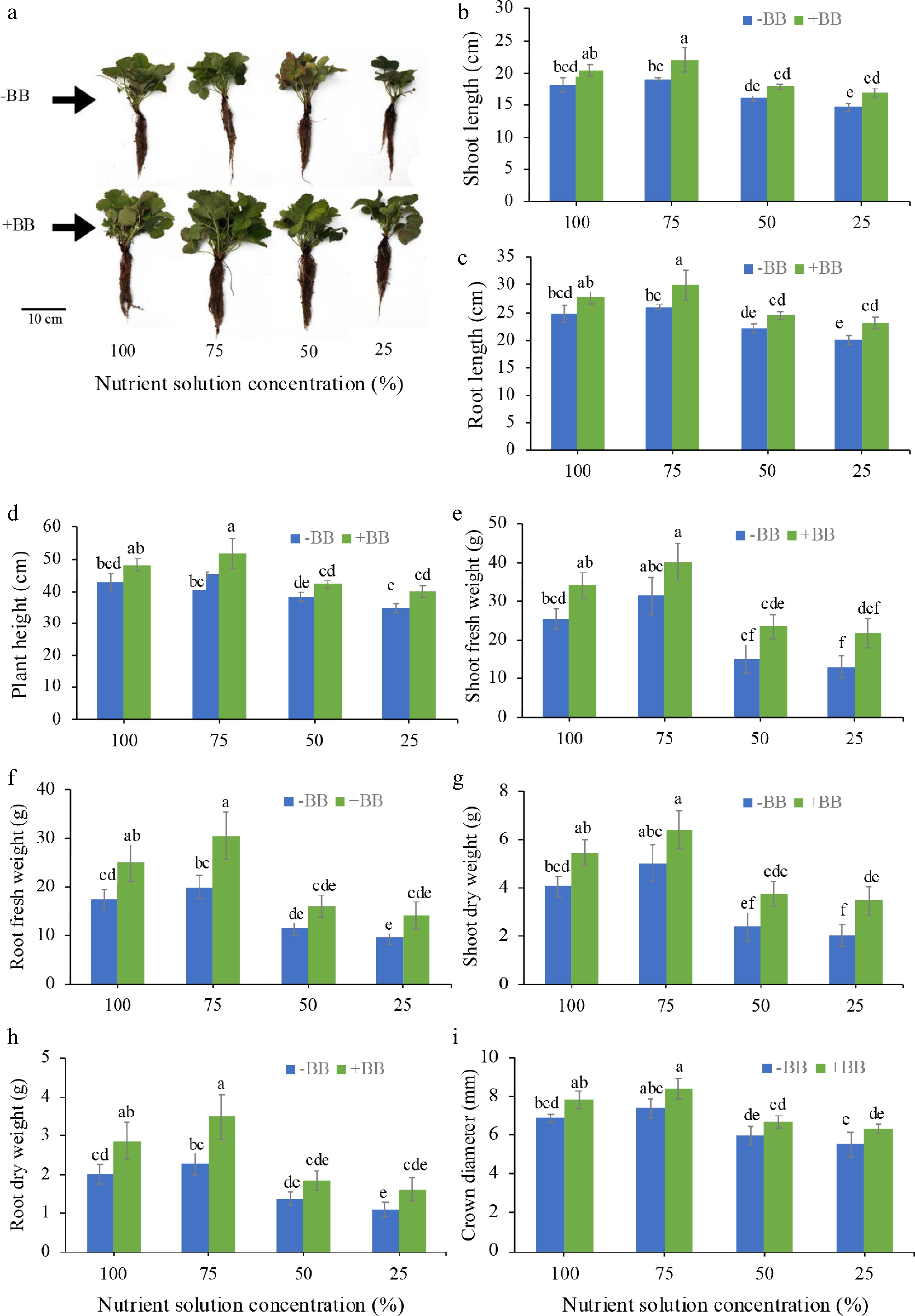

B. bassiana-inoculated plants showed improved phenotypic appearance and greater canopy coverage compared to uninoculated plants at all applied nutritional solution concentrations (Fig. 1a). Though statistical analysis revealed that only 75% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB treatments showed significant differences in shoot length, root length, and plant height when compared to their respective NS controls, whereas 100% NS + BB and 100% NS shared a common statistical group ('b'), and 50% NS + BB and 50% NS shared a common statistical group ('d'). In comparison with the untreated plants however, 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB improved shoot length (by 12.1%, 15.2%, 10.2%, and 15.5%) (Fig. 1b), root length (by 12.2%, 15%, 10.3%, and 15.5%) (Fig. 1c), and plant height (by 12.2%, 15.1%, 10.2%, and 15.5%) (Fig. 1d). For shoot fresh weight, none are significantly different from their respective controls statistically, but shoot fresh weight actually increased by 34.3%, 27.9%, 55.3%, and 67.7%, compared to their respective control plants (Fig. 1e). In the case of root fresh weight, statistically only 100% NS and 75% NS were different from the same strength with B. bassiana inoculation, but actually root fresh weight increased by 42.9%, 52.5%, 37.3%, and 47.5%, compared to their respective controls (Fig. 1f). For shoot dry weight, statistically only 25% NS is different from the same strength with BB inoculation, but they increased by 33.6%, 27.8%, 56.3%, and 69.8%, compared to their control plants (Fig. 1g). For root dry weight, only 100% NS and 75% NS are different from the same strength with BB inoculation, but they actually increased by 41.9%, 52.2%, 34.1%, and 48.2%, compared to their respective controls (Fig. 1h). For crown diameter, none are significantly different statistically, but they increased by 14.1%, 13.8%, 11.7%, and 14.5% (Fig. 1i) in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB plants compared to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% NS, respectively. Among all treatments, '75% NS + BB' plants showed increased root, shoot, and crown characteristics.

Figure 1.

Effects of B. bassiana on the morphological growth characters of strawberry plants grown in hydroponics at different nutrient concentrations. (a) Representative photographs of strawberry plants with and without BB at 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution concentration, (b) shoot length, (c) root length, (d) plant height, (e) shoot fresh weight, (f) root fresh weight, (g) shoot dry weight, (h) root dry weight, and (i) crown diameter, subjected to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution respectively. Only bars with different letters are significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; +BB, plant treated with B. bassiana; NS, nutrient solution.

Confirmation of B. bassiana colonization in the before root section of strawberry plant

-

Colonization of B. bassiana was confirmed by estimating the percentage of root sections with characteristic B. bassiana growth onto semi-selective agar medium. One main root was cut from each plant, and a 3 cm section was cut from the middle of the root and surface sterilized. Each 3 cm root section was trimmed into six sections of 0.5 cm each, and placed on a petri dish with selective medium. The mean colonization (n = 4) was 45.8% ± 4.17%, 58.4% ± 4.81%, 41.7% ± 4.81%, and 37.5% ± 4.17%. in root section of strawberry plants grown in 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution, respectively inoculated with B. bassiana. The control plants did not exhibit any fungal colony in root sections (Table 1).

Table 1. Strawberry root colonization percentage by B. bassiana.

Nutrient solution concentration BB inoculation % root colonization 100% NS −BB Not detected +BB 45.83 ± 4.17a 75% NS −BB Not detected +BB 58.34 ± 4.81ab 50% NS −BB Not detected +BB 41.67 ± 4.81b 25% NS −BB Not detected +BB 37.50 ± 4.17b Means ± SEMs with the same letter are not significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). NS, nutrient solution; −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; +BB, plant treated with B. bassiana. Effect of B. bassiana on leaf traits of strawberry plant

-

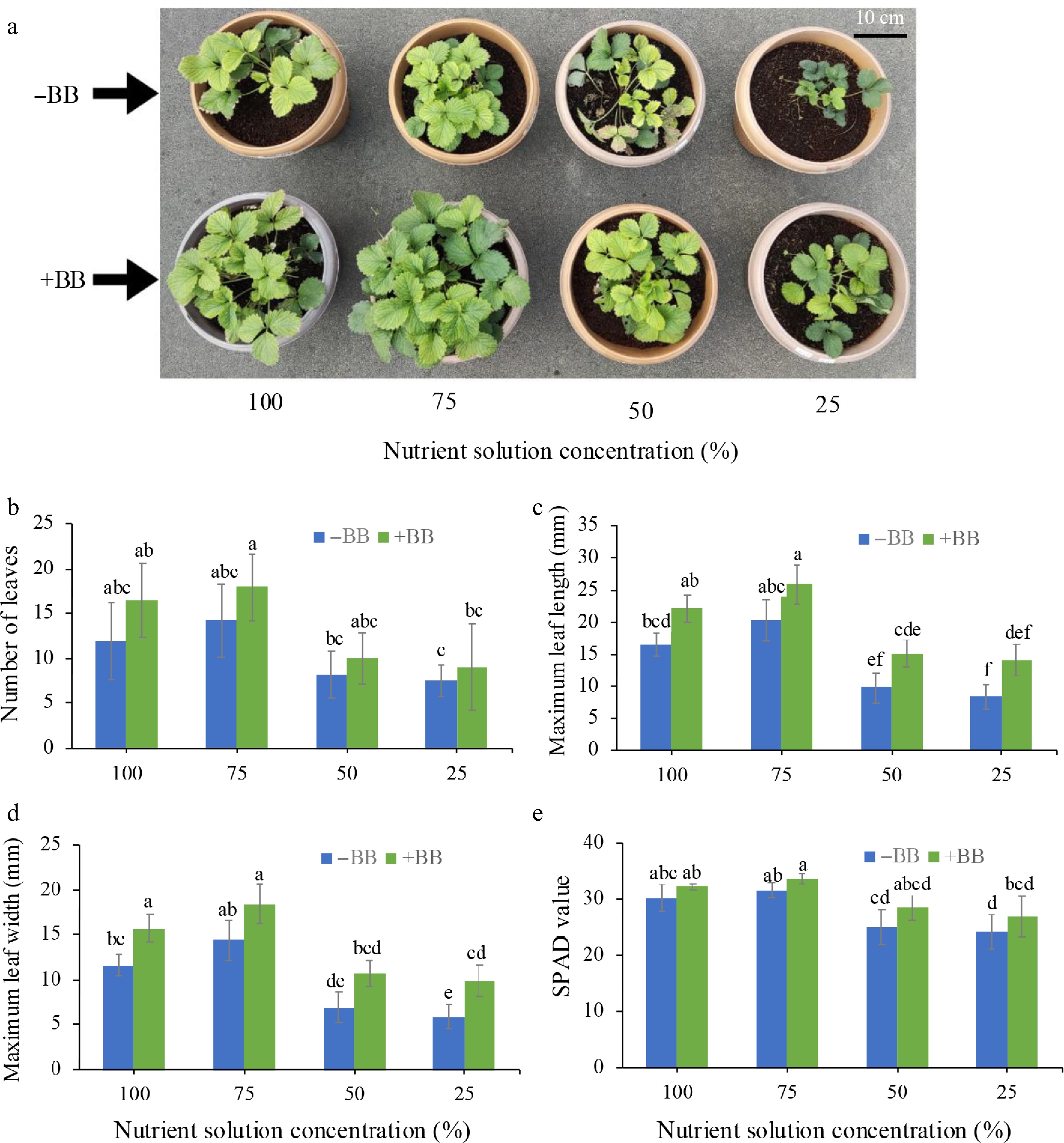

The leaf traits of B. bassiana-treated plants showed significant effects on the leaf traits of strawberry plant. Though the improvements weren't statistically significant in the case of leaf length and SPAD value, but only significant for leaf width in 100% NS + BB and 25% NS + BB treated plants, 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB treatments improved leaf number per plant (by 37.5%, 26.3%, 21.2%, and 20%) (Fig. 2a), maximum leaf length (by 33.9%, 27.6%, 55.9%, and 68%) (Fig. 2b), maximum leaf width (by 34.4%, 27.8%, 55.6%, and 67.8%) (Fig. 2c), and SPAD value (by 6.6%, 6.5%, 14.1%, and 10.6%) (Fig. 2d), compared to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% NS, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effects of B. bassiana on strawberry leaf growth-associated attributes at different nutrient concentrations. (a) Representative photographs of strawberry leaf growth with and without BB at 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution concentration. (b) Number of leaves per plant, (c) maximum leaf length, (d) maximum leaf width, and (e) SPAD value, subjected to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution respectively. Only bars with different letters are significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; +BB, plant treated with B. bassiana; NS, nutrient solution.

Effect of B. bassiana on the before insect infestation of strawberry plant leaf

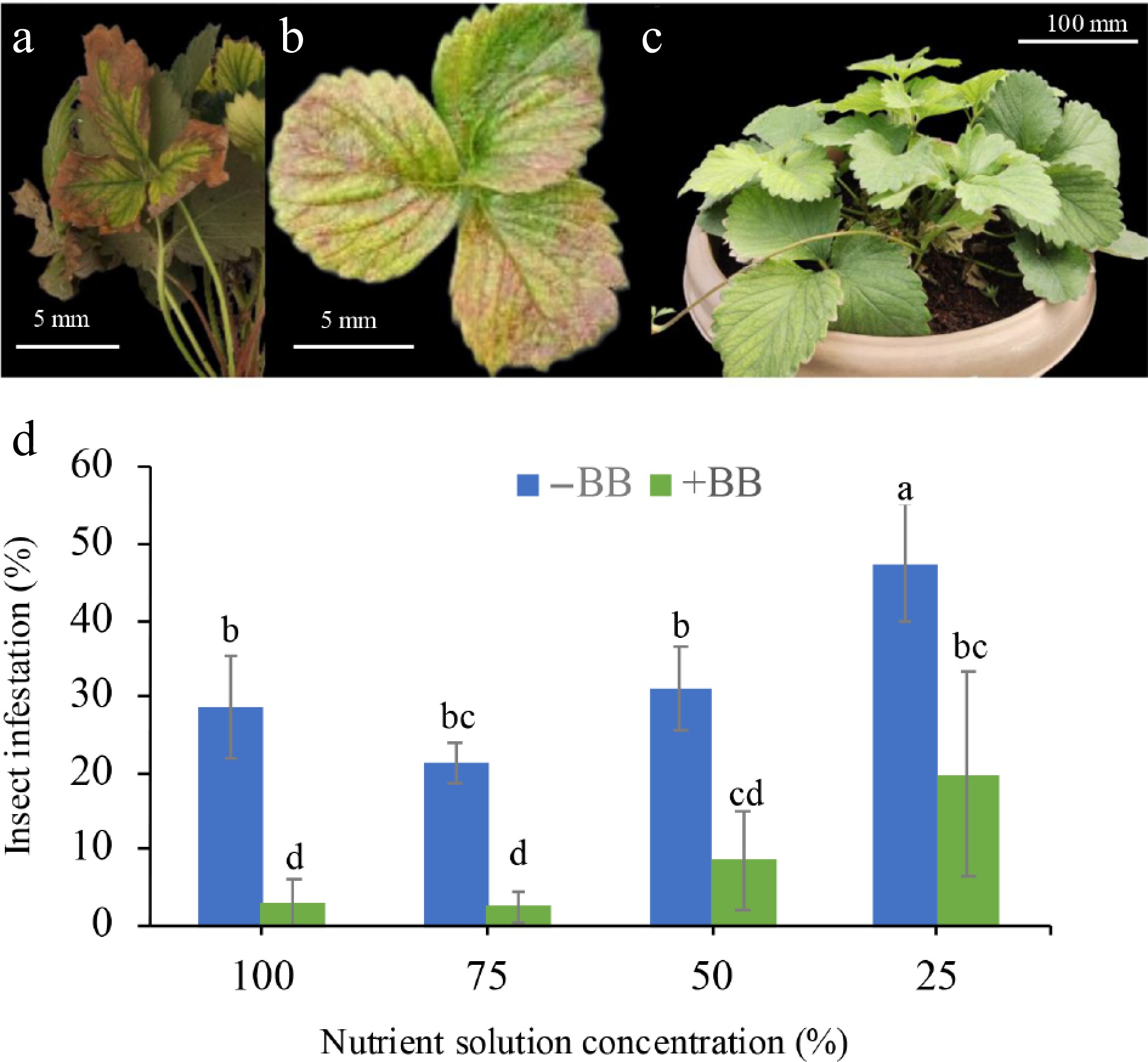

-

Infestation symptoms of spider mites (Fig. 3a) and leaf rollers (Fig. 3b) were observed in affected strawberry leaves compared to the fresh, unaffected strawberry leaves (Fig. 3c). In comparison with the untreated plants, 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB reduced insect infestation by 88.8%, 88%, 72.3%, and 58.3%, respectively, when compared with 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% NS plants (Fig. 3d). However, the abundance and diversity of insects in strawberry plants were not counted in this experiment.

Figure 3.

Different insect infestations in strawberry leaves in comparison with fresh leaves. (a) Spider mite infestation, (b) leaf roller-infested leaves, (c) non-infested fresh leaves, and (d) effects of B. bassiana on insect infestation as percent of infested leaves of strawberry plants at 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution concentrations. Only bars with different letters are significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; + BB, plant treated with B. bassiana.

Effect of B. bassiana on flower and fruit production of strawberry

-

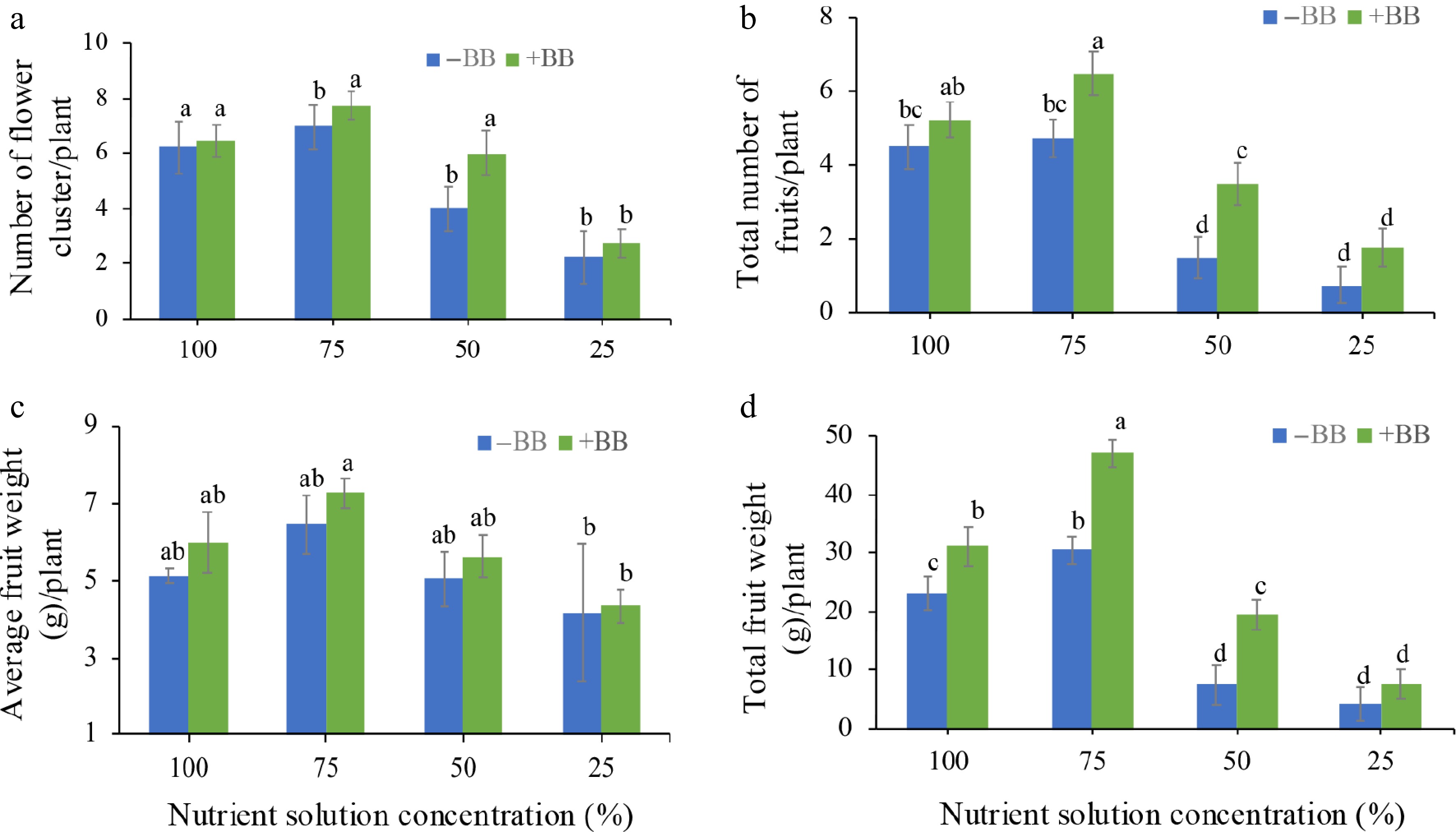

In comparison with the non-treated plants, 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB treated plants' improvement in number of flower clusters per plant, total number of fruits per plant, average fruit weight per plant, and total fruit weight per plant are statistically partially significant (only 50% NS + BB in number of flower clusters per plant, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB in average fruit weight per plant, and 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, and 50% NS + BB in total fruit weight per plant). But in comparison with the non-treated plants, 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB improved in number of flower clusters per plant (by 12%, 19.2%, 50%, and 22.2%) (Fig. 4a), total number of fruits per plant (by 16.7%, 36.8%, 133.3%, and 133.3%) (Fig. 4b), average fruit weight per plant (by 34.3%, 27.9%, 55.3%, and 67.7%) (Fig. 4c), and total fruit weight per plant (by 34.8%, 54.3%, 156.4%, and 83%) (Fig. 4d), respectively, when contrasted with the corresponding 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% NS plants, respectively.

Figure 4.

Effects of B. bassiana on strawberry flower and fruit production-associated attributes at different nutrient concentrations. (a) Number of flower clusters per plant, (b) total number of fruits per plant, (c) average fruit weight per plant, and (d) total fruit weight per plant subjected to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution respectively. Only bars with different letters are significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; +BB, plant treated with B. bassiana.

Effect of B. bassiana on the before nutritional quality of strawberry fruit

-

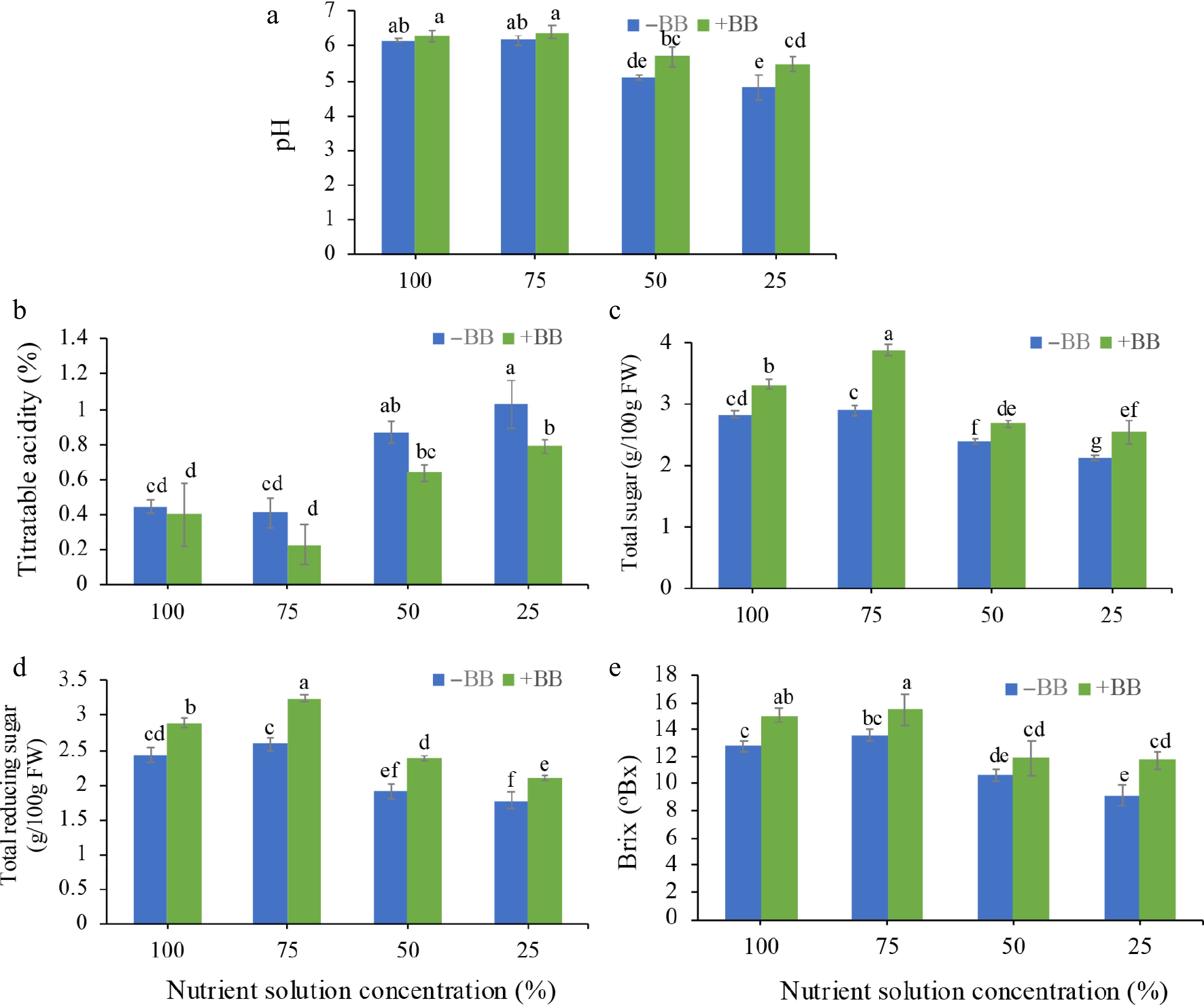

Various important fruits' nutritional quality parameters, including pH, titratable acidity, total sugar, total reducing sugar, and Brix, were analyzed to evaluate the effect of B. bassiana on strawberry fruits harvested from different nutrient solution concentrations. In the case of pH, strawberry fruits grown under 50% NS + BB and 25% NS + BB showed statistically significant improvement, whereas pH actually increased by 2%, 3.6%, 11.5%, and 13.9% (Fig. 5a) in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB, respectively. In the case of titratable acidity, there is only a statistically significant difference in 25% NS + BB, but actually, titratable acidity was reduced by 11.1%, 43.9%, 26.4%, and 23.3% in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB, respectively (Fig. 5b). In the case of total sugar and total reducing sugar, all are statistically significantly different, and total sugar increased by 17.3%, 33.7%, 12.6%, and 19.7% (Fig. 5c), and total reducing sugar (by 18.9%, 25.1%, 24.5%, and 18%) (Fig. 5d) in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB, respectively. In the case of Brix, all are statistically significant except 50% NS + BB, but it increased by 18%, 13.8%, 11.2%, and 28.7% in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB (Fig. 5e), compared to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% NS plants, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effects of B. bassiana acidity and sugar content of strawberry fruits at different nutrient concentrations. (a) pH, (b) titratable acidity, (c) total sugar, (d) total reducing sugar, and (e) Brix subjected to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution respectively. Only bars with different letters are significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; +BB, plant treated with B. bassiana; FW, Fresh weight.

Effect of B. bassiana on the before mineral content of strawberry fruit

-

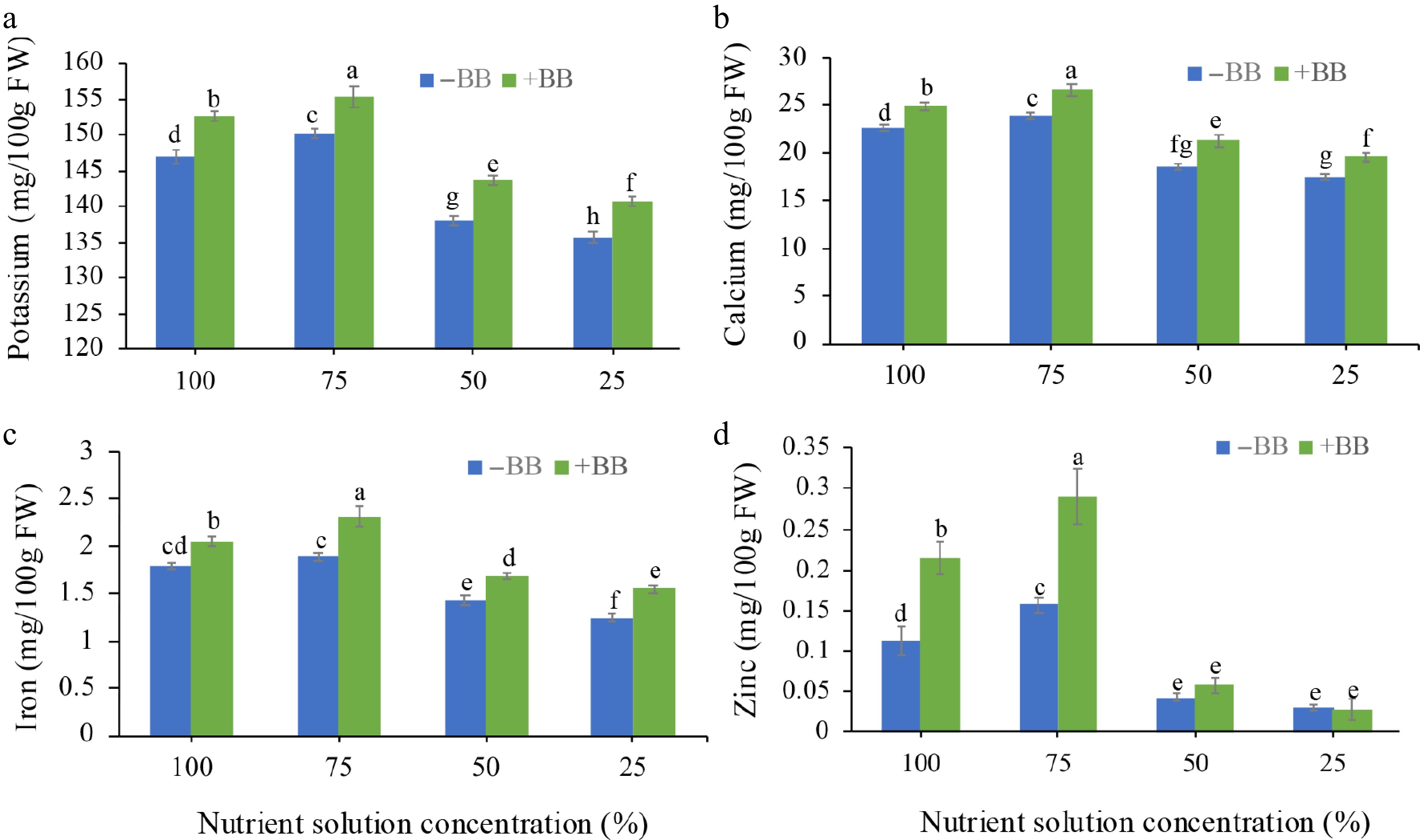

B. bassiana-treated plants also increased fruits' mineral contents, especially K (by 3.9%, 3.4%, 4%, and 3.8%) (Fig. 6a), Ca (by 10.2%, 11.5%, 14.7%, and 11.2%) (Fig. 6b), and Fe (by 15%, 21.6%, 19%, and 24%) (Fig. 6c), respectively, compared to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% NS plants, respectively. Notably, increased amounts of zinc were detected in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, and 50% NS + BB-treated plants' fruits (by 100%, 81.3%, and 50%), compared to their non-treated plants' fruits (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

Effects of B. bassiana minerals content of strawberry fruits at different nutrient concentrations. (a) Potassium, (b) calcium, (c) iron, and (d) zinc subjected to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution respectively. Only bars with different letters are significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; +BB, plant treated with B. bassiana; FW, Fresh weight.

Effect of B. bassiana on phytochemical levels of strawberry fruit

-

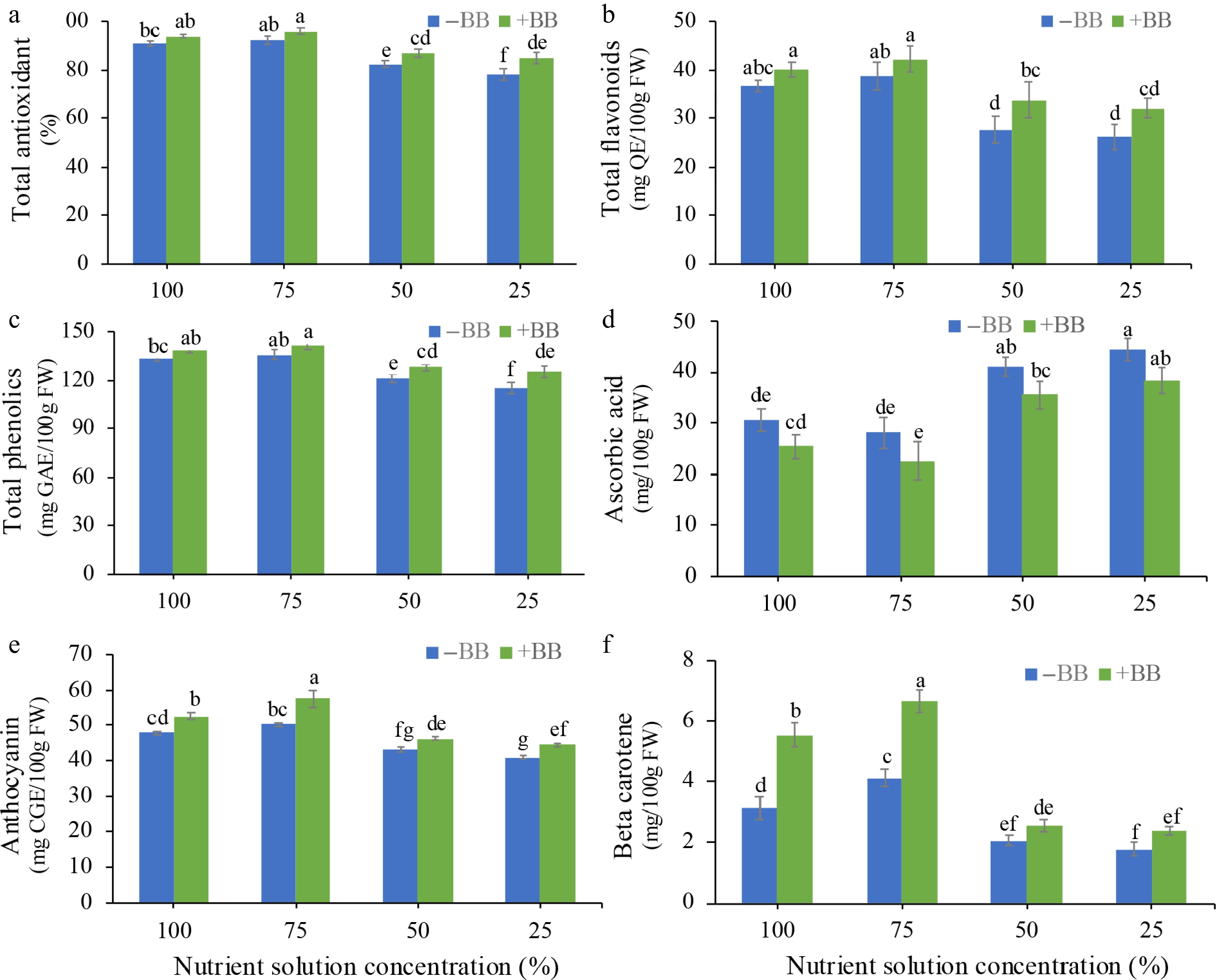

In the case of antioxidant content and phenolic content, only 50% NS + BB and 25% NS + BB are statistically significant, but actually, B. bassiana-treated strawberry plants increased fruits' total antioxidant content by 3.6%, 3.9%, 5.5%, and 8.9% (Fig. 7a), and total phenolic content by 3.6%, 3.9%, 5.5%, and 8.9% (Fig. 7b) in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB treatments, respectively. In the case of total flavonoid content, only 50% NS + BB showed statistical significance, but actually they increased by 9%, 9.2%, 22.2%, and 22.1% in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB treatments compared to their uninoculated counterparts (Fig. 7c). B. bassiana-treated plants reduced ascorbic acid by 16.9%, 19.8%, 13.7%, and 13.8%, but there is no statistical significance (Fig. 7d). In the case of anthocyanin, all are statistically significant, and anthocyanin increased by 9.6%, 14.7%, 7.4%, and 8.6% (Fig. 7e). In the case of β-carotene, only 100% NS + BB and 75% NS + BB showed statistical significance, but they increased by 77.3%, 61%, 22.6%, and 33.7% (Fig. 7f) in 100% NS + BB, 75% NS + BB, 50% NS + BB, and 25% NS + BB treatments compared to corresponding uninoculated plants.

Figure 7.

Effects of B. bassiana phytochemical levels of strawberry fruits at different nutrient concentrations. (a) Total antioxidant, (b) total flavonoid content, (c) total phenolic content, (d) ascorbic acid, (e) anthocyanin, and (f) beta carotene subjected to 100%, 75%, 50%, and 25% nutrient solution respectively. Only bars with different letters are significantly different (lsd, p < 0.05). −BB, plant treated without B. bassiana; +BB, plant treated with B. bassiana; FW, Fresh weight; GAE, gallic acid equivalent; QE, quercetin equivalent; CGE, cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalent.

Visualization of data with a clustered heatmap and unveiling the treatment-variable interaction

-

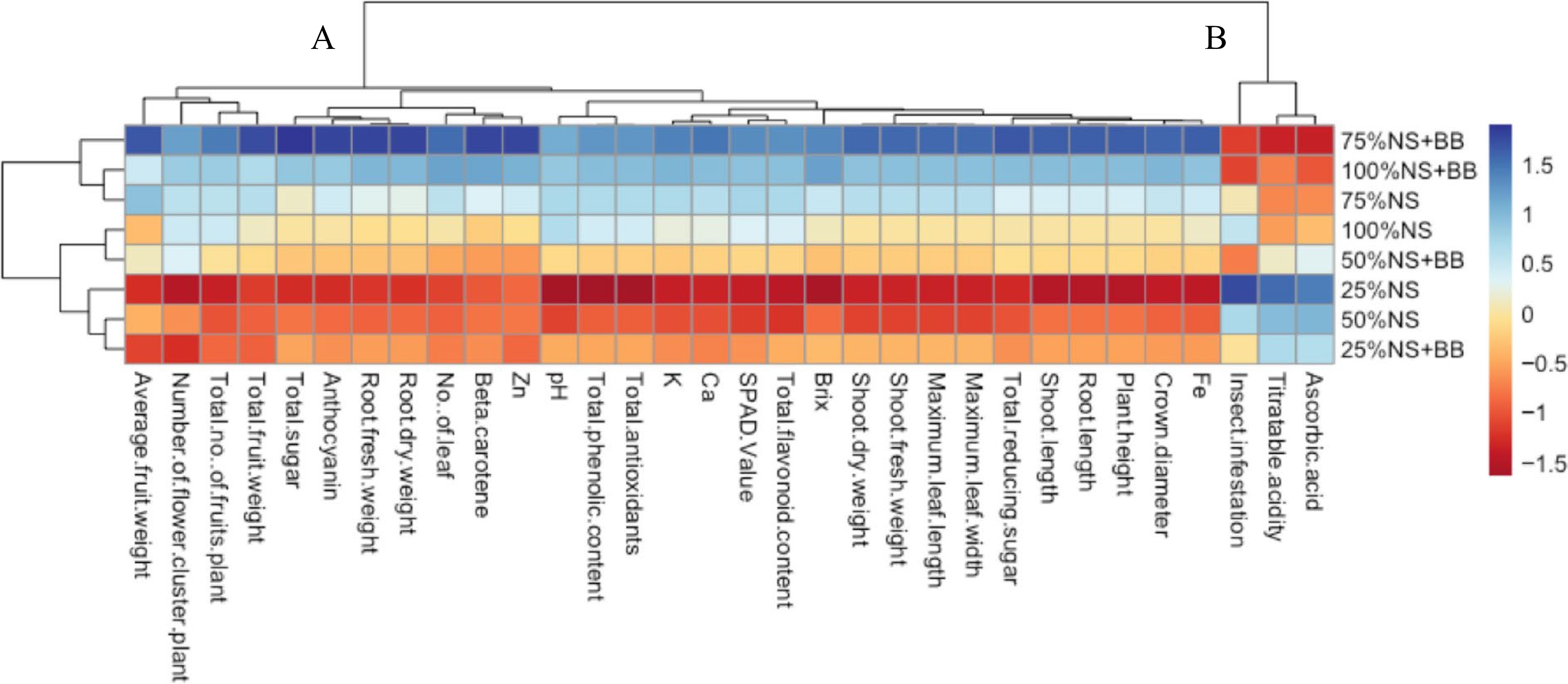

A heatmap was constructed to visually represent the performance of diverse parameters under varying treatment conditions, with color intensity serving as an indicator (Fig. 8). The hierarchical clustering method segregated these parameters into two distinct clusters. Cluster-A comprised all parameters related to the growth, yield, and biochemical and nutritional characteristics of high-quality strawberry fruits. These parameters included SPAD value, shoot length, root length, plant height, crown diameter, number of leaves per plant, maximum leaf length, maximum leaf width, shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, shoot dry weight, root dry weight, number of flower clusters per plant, total number of fruits per plant, total fruit weight per plant, average fruit weight per plant, fruit pH, brix, total sugar, total reducing sugar, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, total antioxidants, β-carotene, anthocyanin, and mineral contents (K, Ca, Fe, and Zn). On the other hand, Cluster-B encompassed the percentage of insect infestation and undesirable traits of fruit quality, including titratable acidity and ascorbic acid content. Among the various treatment combinations, the application of B. bassiana with a 75% nutrient solution demonstrated a stronger positive association with Cluster A, and a stronger negative association with Cluster B than other treatment combinations.

Figure 8.

Clustering heatmap visualizing treatments-variable interaction at a glance. Normalized mean values of different parameters were used to prepare the heatmap. The parameters were grouped into two (A and B) distinct clusters. The color scale indicates the relationship of the normalized mean values of different parameters with different treatments.

-

Endophytes, especially root colonizers, are beneficial for plant growth and yield by improving nutrient acquisition in plants[42−45]. The Hypocrealean fungus B. bassiana is widely used as an entomopathogen and has been identified as an endophyte of plants[46]. This research elucidated the roles of B. bassiana on hydroponically cultivated strawberries, with a particular focus on aspects such as plant growth and development, fruit nutritional quality, and nutrient use efficiency, which are discussed below.

B. bassiana improved the before growth of strawberry plant

-

In this study, it was found that B. bassiana-treated strawberry plants showed the highest plant growth attributes, especially shoot and root length, fresh weight, dry weight, crown diameter, leaf number, and maximum leaf length and width, in varying nutrient concentrations (Figs 1, 2). Recent studies have shown that B. bassiana colonization in plant roots increases nutrient uptake and improves plant growth in onion and lettuce grown under soilless conditions[47,48]. In addition, in different growth media, some promising results have also been reported for B. bassiana-inoculated crops, including increased plant height, leaf number, highest survival rate, and fastest shoot growth in cucumber, cabbage, common bean, cotton, maize, and cowpea[13−16,43,45,49,50]. In the present study, strawberry plant growth improvement was evident in 75% nutrient solution, and BB inoculated conditions. Earlier research also suggested that the molecular mechanisms involved in plant growth promotion by B. bassiana are the upregulation of calcium transporters, enhancement of molecular pathways linked to protein/amino acid turnover, and biosynthesis of energy compounds in plants[51]. Nutrient bioavailability and iron and phosphorus solubilization in B. bassiana also contribute to plant growth[52]. In addition, microbial synthesis of phytohormones by Hypocrealean endophytes, which contributes to root elongation and facilitates nutrient uptake, is another possible mechanism for plant growth promotion[53].

B. bassiana increased plant growth and fruit attributes of strawberry

-

This research revealed that strawberry plants treated with B. bassiana demonstrated enhanced fruit production characteristics. It significantly enhanced strawberry yield attributes excluding average fruit weight by increasing flowering clusters (50% increase at 50% nutrients), fruit number (up to 133.3%), and total fruit weight per plant (up to 156.4%) at most nutrient levels (Fig. 4). The present research findings align with those of Gana et al.[48], demonstrating a significant enhancement in both bulb circumference and maximum bulb weight in onion plants inoculated with B. bassiana in a hydroponic environment. Additional studies have reported numerous successful outcomes related to flower and fruit production, including accelerated flowering time, increased spike production, and higher flower number, culminating in high-quality fruit production in maize and cucumber as a result of B. bassiana application[16,43]. It has been shown that the production of methyl cellulose in root zones fosters a long-term symbiotic relationship with B. bassiana, thereby enhancing the acquisition of beneficial nutrients essential for spike development and subsequent grain production in maize[16]. The proliferation of flower and fruit production in cucumber has been attributed to the secretion of specific phytochemicals and hormones by B. bassiana, which confer benefits to plant health[43].

B. bassiana reduced insect infestation in strawberry plants grown in coconut substrate-based soilless hydroponics

-

In the present research, a decrease in insect infestation in plants inoculated with B. bassiana at varying nutrient concentrations was observed. Significant reduction in insect infestation symptoms from spider mites and leaf rollers in strawberry plants by up to 88.8% across all nutrient levels with its inoculation (Fig. 3). This observation aligns with recent research demonstrating the efficacy of this fungus in reducing infestations of various pests across different plant species. For instance, B. bassiana has been shown to mitigate Myzus persicae infestation in lettuce[47], Aphis gossypii infestation in cucumber[43,44], Planococcus ficus infestation in grapevine[54], Lipaphis erysimi infestation in Chinese kale[46], and Tetranychus urticae infestation in bean[55]. The reduction of insect infestation in plants colonized by B. bassiana is associated with the induction of plant defense enzymes like superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, and protease[56]. In addition, upon root colonization by this fungus, there is an observed augmentation in the myrosinase content within the plant tissue[57]. This elevation in myrosinase content acts as a deterrent to insects, thereby safeguarding the host plants from potential infestations. These phenomena underscore the integral role of B. bassiana in enhancing plant defense mechanisms against insect threats.

B. bassiana enhanced strawberry fruit quality attributes in hydroponics

-

This research has demonstrated that strawberry plants treated with B. bassiana exhibited enhanced fruit quality attributes. Its inoculation significantly improved the nutritional quality of strawberry fruits by increasing pH, total and reducing sugars, and brix content (up to 28.7%), while reducing titratable acidity, particularly under reduced nutrient levels (Fig. 5). It also significantly enhanced mineral nutrient content in strawberry fruits, increasing K (3.4%–4.0%), Ca (10.2%–14.7%), and Zn (50.0%–100.0%) at most nutrient levels, while Fe decreased under reduced nutrient conditions (Fig. 6). Furthermore, a reduction in titratable acidity and ascorbic acid content was observed at different nutrient concentrations. Notably, the fruits of the '75% NS + BB' plants exhibited the highest performance across all treatment combinations. In particular, the higher sugar content in terms of brix and total sugar content in '75% NS + BB', compared to other treatments indicate desirable strawberry fruit quality. Moreover, lower acidity indicates higher brix content having a less sour taste, which is also a desirable attribute of strawberry fruit. B. bassiana application significantly increase the total antioxidants (3.6%–8.9%), phenolics (3.6%–8.9%), anthocyanins (7.4%–14.7%), β-carotene (22.6%–77.3%), and flavonoids (9.0%–22.2%) across most nutrient levels, while decreasing ascorbic acid content (13.7%–19.8%), except at 75% (Fig. 7). Previous studies also showed that B. bassiana application significantly enhanced total phenol and flavonoid content, antioxidants, and mineral contents in onion bulbs and lettuce in hydroponic conditions[47,48,58]. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi have also been found to increase anthocyanin and β-carotene in treated plants grown in greenhouse-hydroponics[59]. These improvements are attributed to increased nutrient uptake by the roots of B. bassiana treated plants, the release of various enzymes and secondary metabolites by it during fruit formation[47,48,58], and the formation of different colour pigments by endophytes through distinct metabolic pathways[60]. Recent research has also revealed that pear fruit juice treated with partially purified polygalacturonase from B. bassiana has increased total antioxidants and phenolics while reducing titratable acidity, thereby offering potential health benefits[61]. However, this study underscores the need for further research to explore the potential of this fungus in enhancing strawberry nutrition and its implications for human health.

B. bassiana enhanced the efficiency of nutrient use in hydroponics

-

Plants treated with a combination of 75% nutrient solution and B. bassiana (75% NS + BB) exhibited the most significant improvements across all plant growth, yield, and fruit biochemical and nutritional qualities of strawberry plants grown in hydroponics. It also noticed that the 100% nutrient dose reduced plant attributes compared with the 75% dose in both B. bassiana-treated and non-treated plants, which was validated by multivariate analysis (Fig. 8). The possible reason is raising phytotoxicity in the highest nutrient concentration due to excessive nutrients for plants results in lower growth and fruit quality[62,63]. The root traits boosted by the studied fungus increased the nutrient foraging activities of strawberries and thus increased nutrient efficiency. This result will contribute to dose optimization in a cost-effective manner, with increased strawberry production and nutrient-use efficiency of hydroponics.

-

This study revealed that B. bassiana colonization significantly enhanced the growth, yield, and fruit quality traits of strawberry plants in a hydroponic growing environment. The improvement in strawberry plant growth, productivity, and fruit quality induced by it was achieved through a comprehensive strategy. This strategy involved enhancements in root and shoot morphology, photosynthetic efficiency, leaf characteristics, antioxidant levels, secondary metabolite production, β-carotene content, anthocyanin levels, and mineral content. Concurrently, it also resulted in a reduction in insect infestation rates, titratable acidity, and ascorbic acid content. The study further suggests that a 75% concentration of the commercial "Enshi-shoo" nutrient solution, in combination with B. bassiana, was the optimal dosage for the strawberry variety under investigation, thereby reducing the nutritional requirement by 25%. Consequently, the application of B. bassiana to strawberry plants in a hydroponic system emerges as an effective strategy for high-quality strawberry production and nutrient use efficiency.

This research was supported by the Bangladesh Academy of Science through the U.S. Department of Agriculture Endowment Program (4th Phase BAS–USDA BSMRAU CR 13), which provided funding for the isolation and characterization of local Beauveria bassiana isolates.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Islam SMN; data curation: Zinan N, Mim MF, Bhuiyan AUA, Sultana R, Asaduzzaman M; formal analysis: Chowdhury MZH, Mim MF, Bhuiyan AUA; fund acquisition: Islam SMN; investigation: Zinan N, Mim MF, Bhuiyan AUA, Asaduzzaman M; methodology: Chowdhury MZH, Sultana R, Asaduzzaman M; resource: Islam SMN; software: Chowdhury MZH, Islam SMN; supervision: Haque MA, Islam SMN, Asaduzzaman M; validation: Asaduzzaman M; visualization: Islam SMN; writing − original draft: Zinan N, Islam SMN, Asaduzzaman M; writing − review and editing: Chowdhury MZH, Haque MA, Sultana R, Islam SMN, Asaduzzaman M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zinan N, Chowdhury MZH, Mim MF, Bhuiyan AUA, Haque MA, et al. 2025. Endophytic Beauveria bassiana enhances plant growth, yield, and fruit nutritional quality in strawberry and improves nutrient use efficiency in hydroponics. Technology in Horticulture 5: e043 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0040

Endophytic Beauveria bassiana enhances plant growth, yield, and fruit nutritional quality in strawberry and improves nutrient use efficiency in hydroponics

- Received: 19 August 2025

- Revised: 12 November 2025

- Accepted: 20 November 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: Symbiotic plant-microbe interactions hold significant potential for improving crops and enhancing efficient nutrient uptake by plants. This research investigated the effects of the endophytic fungus Beauveria bassiana (B. bassiana) on strawberry growth, production, fruit nutritional quality, and nutrient use efficiency in hydroponics. Strawberry plants were grown on a coconut substrate-based hydroponic system with different levels of deficiency in commercial 'Enshi-shoo' nutrient solution (NS) at 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of the recommended concentration. Comparing B. bassiana -inoculated plants to corresponding non-treated plants at varying NS concentrations indicated that B. bassiana-inoculated plants exhibited higher biomass, leaf features, photosynthetic pigments, and reduced insect infestation. These traits resulted in improved flower clusters, fruit quantity, and fruit fresh weight. The B. bassiana inoculation significantly improved the quality and mineral content of strawberry fruits. All morphological, yield, and fruit nutritional and biochemical characteristics were significantly higher in the 75% NS + B. bassiana treatment compared to the 100% NS treatment, indicating that B. bassiana treatment reduced the NS requirement. The present research demonstrates that B. bassiana has potential for promoting strawberry plant growth and productivity, fruit nutritional quality, plant protection, and improved nutrient use efficiency of hydroponics.

-

Key words:

- Beauveria bassiana /

- Strawberry /

- Fruit quality /

- Hydroponics /

- Nutrient use efficiency