-

With the rapid development of society and technology, the issues of energy shortage are increasingly acute. Renewable energy and improving energy utilization are the key approaches to addressing the above issues[1,2]. However, a large amount of energy is dissipated as thermal energy during energy conversion and utilization. Thus, thermal storage technology is crucial for promoting energy development[3].

Latent thermal storage has received much attention in recent years owing to its high thermal storage density and constant temperature. Among them, organic phase change materials (PCM) are the typical medium with a low supercooling degree, non-toxicity, and chemical stability[4]. Despite these advantages, melting leakage is a common problem for all PCMs, leading to device pollution and a loss of thermal storage capacity, which restricts their practical application. This drawback could be resolved by encapsulating PCMs into porous materials to obtain shape-stabilized PCMs (SSPCMs)[5,6]. In this context, porous materials, such as expanded graphite, metal foam, metal organic frameworks (MOFs), and so on, act as supports that absorb PCMs through interactions (capillary force, surface tension, hydrogen bonds) to prevent melting leakage and provide shape stability for PCMs[7]. For instance, Nguyen et al.[8] prepared an SSPCM using expanded graphite and stearic acid (SA). The expanded graphite prevented melting leakage when SA was 80 wt% in the SSPCM. Ma et al.[9] combined MOF-199, carbon nanotubes, and SA to synthesize an SSPCM (SA/CM-X), and SA/CM-2 showed a maximum encapsulating capacity of 70 wt% SA without leakage. Whereas, the above-mentioned supports are unfavorable strategies for the preparation of SSPCMs owing to their high cost and unsustainability. It is urgent to explore a support with low cost that is also eco-friendly.

Biomass-derived carbon has the characteristics of extensive sources and diversity. Importantly, its high specific surface area, abundant functional groups, and excellent chemical stability are favorable features to prevent the melting leakage[10,11], so biomass-derived carbon is an ideal candidate as a support for PCMs. Atinafu et al.[12] explored biochar derived from food waste to prevent the leakage of octadecane, and the synthesized SSPCM exhibited a high phase change enthalpy of 103.4 kJ/kg, which has huge potential for use in thermal storage at low temperature. Liu et al.[13] encapsulated polyethylene glycol (PEG) into corn straw biochar (CSBC) for resolving melting leakage. Results showed that CSBC could prevent leakage with a PEG content of no more than 50 wt%. Those SSPCMs originated from biomass waste reflect unique advantages for cost-efficient, high-value applications.

In a myriad of biomass, chitin (β-(1,4)-2-acetylamino-2-deoxy-D-glucose), widely distributed in crustaceans, fungi, and microorganisms, has abundant N content with regular distribution[14]. This feature can be inherited by chitin-derived carbon and can induce hydrogen bonds with organic PCMs. In our previous research[15], chitin-derived carbon with abundant N on the surface induces intensive hydrogen bonds with stearic acid (SA), enhancing the shape stability of the SSPCM, where the melting leakage of SA is suppressed efficiently. However, the undesirable pore structure in chitin-derived carbon makes it difficult to achieve high PCM encapsulating capacity. This is attributed to two reasons: (1) the tight arrangement of molecule chains in chitin is adverse to generating a pore structure during carbonization[16]; (2) the small particle size of chitin-derived carbon makes it difficult to provide enough storage space for PCM. It is critical to resolve these drawbacks for achieving an ideal shape stability and thermal property in SSPCM. Therefore, an effective strategy is further proposed in this study to improve the pore structure of chitin derived carbon and enhance its encapsulating capacity for SA.

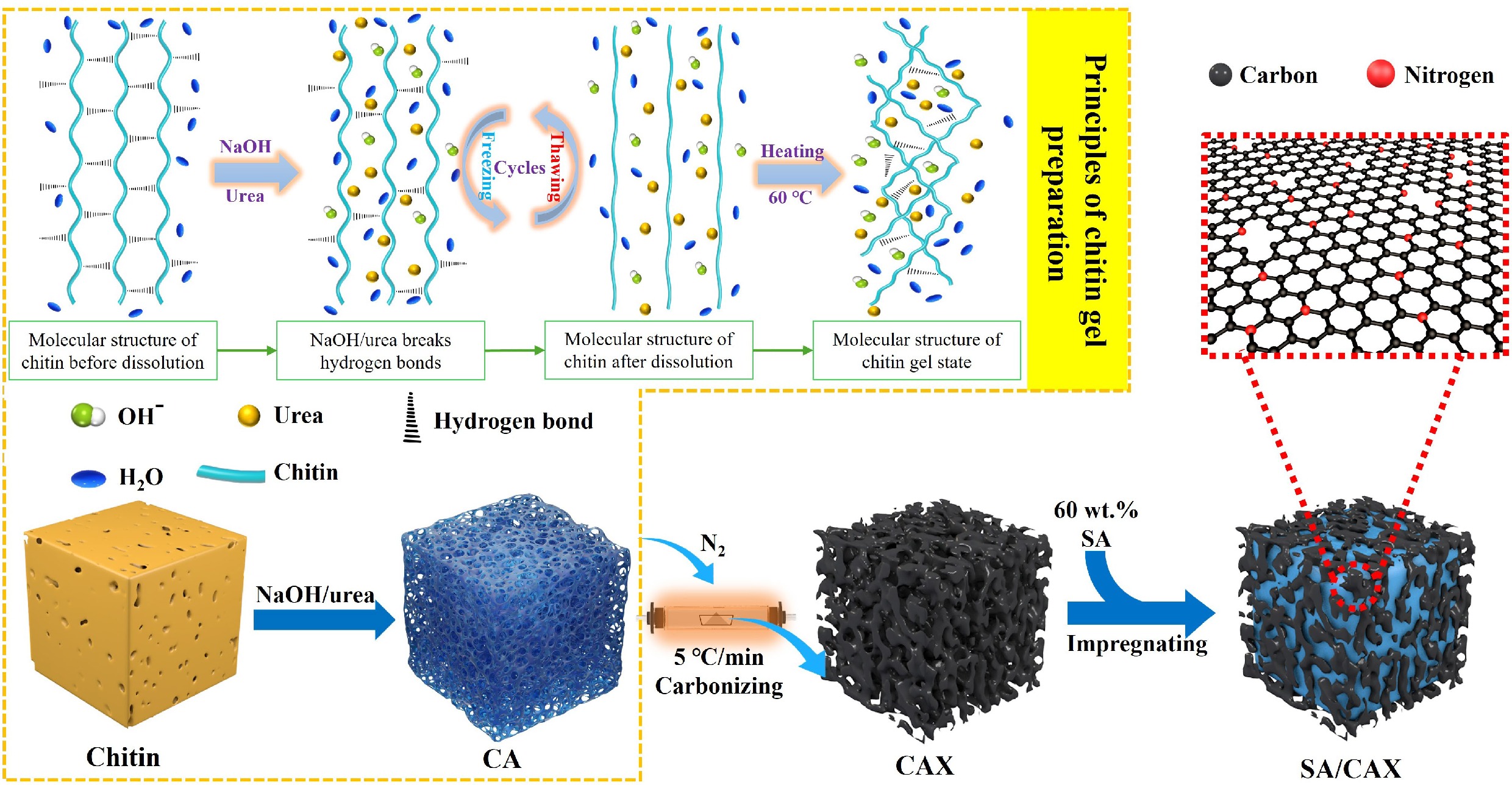

Aerogels have ultrahigh porosity, low density, high total pore volume, prominent mechanical property, and high chemical stability[17]. Compared with other porous materials, aerogel can encapsulate PCMs at a higher capacity[18]. Based on this advantage, a chitin aerogel-based SSPCM (SA/CAX) is prepared in this study. Chitin aerogel was synthesized by dissolving chitin in NaOH/urea solution, followed by dialysis and freeze-drying[19]. Then, SA was immersed in porous carbon derived from chitin aerogel (CAX) to obtain SA/CAX. The thermal storage performance of SA/CAX was investigated at different carbonization temperatures of CAX, and its influence mechanism from the physicochemical properties of CAX was revealed by characterizations and comparative experiments. This work not only provides a feasible approach to prepare SSPCMs but also contributes to revealing the influence mechanism of aerogel on the thermal storage performance of PCMs.

-

Chitin, stearic acid (SA, C18H36O2), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China), Urea (CH4N2O) was acquired from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Preparation of chitin aerogel

-

Chitin was dissolved according to the reported literature[20], where 2 g chitin was dispersed in an 8 wt% NaOH/4 wt% urea aqueous solution and stirred for 0.5 h. The obtained suspension was frozen at –30 °C for 4 h, subsequently being thawed at room temperature. This freezing/thawing process was repeated two times until chitin dissolved completely. The transparent solution was transferred into chitin hydrogel at 60 °C for 2 h; after that, it was dialyzed until a neutral pH was reached. Finally, the hydrogel underwent freeze-drying to collect chitin aerogel.

Preparation of supports

-

To investigate the influence of porous carbon on thermal storage performance, chitin aerogel was carbonized at different temperatures of 500, 600, 700, 800, and 900 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C/min and was maintained for 2 h. The obtained porous carbon was labeled as CAX, where X represented the carbonization temperature. As a comparison, chitin without gelation was directly carbonized at 500 °C according to the reported literature[15] to obtain a support named as CN500, which was used to analyze the different physicochemical properties of the support impacting the PCMs.

Preparation of SSPCM

-

The SSPCM was prepared by the method of vacuum-assisted infiltration. In detail, 3 g SA was heated at 90 °C until it melted completely, and then 2 g CAX was immersed in the melted SA for 1 h. The mixture was sonicated at 90 °C for 30 min, and then cooled to room temperature. To ensure homogeneity, the aforementioned process was repeated twice. Ultimately, the mixture was infiltrated under vacuum conditions (–0.1 MPa) with 90 °C for 6 h, acquiring the SSPCM of SA/CAX. Similarly, CN500 was immersed in SA by the same process to synthesize SA/CN500.

Characterizations

-

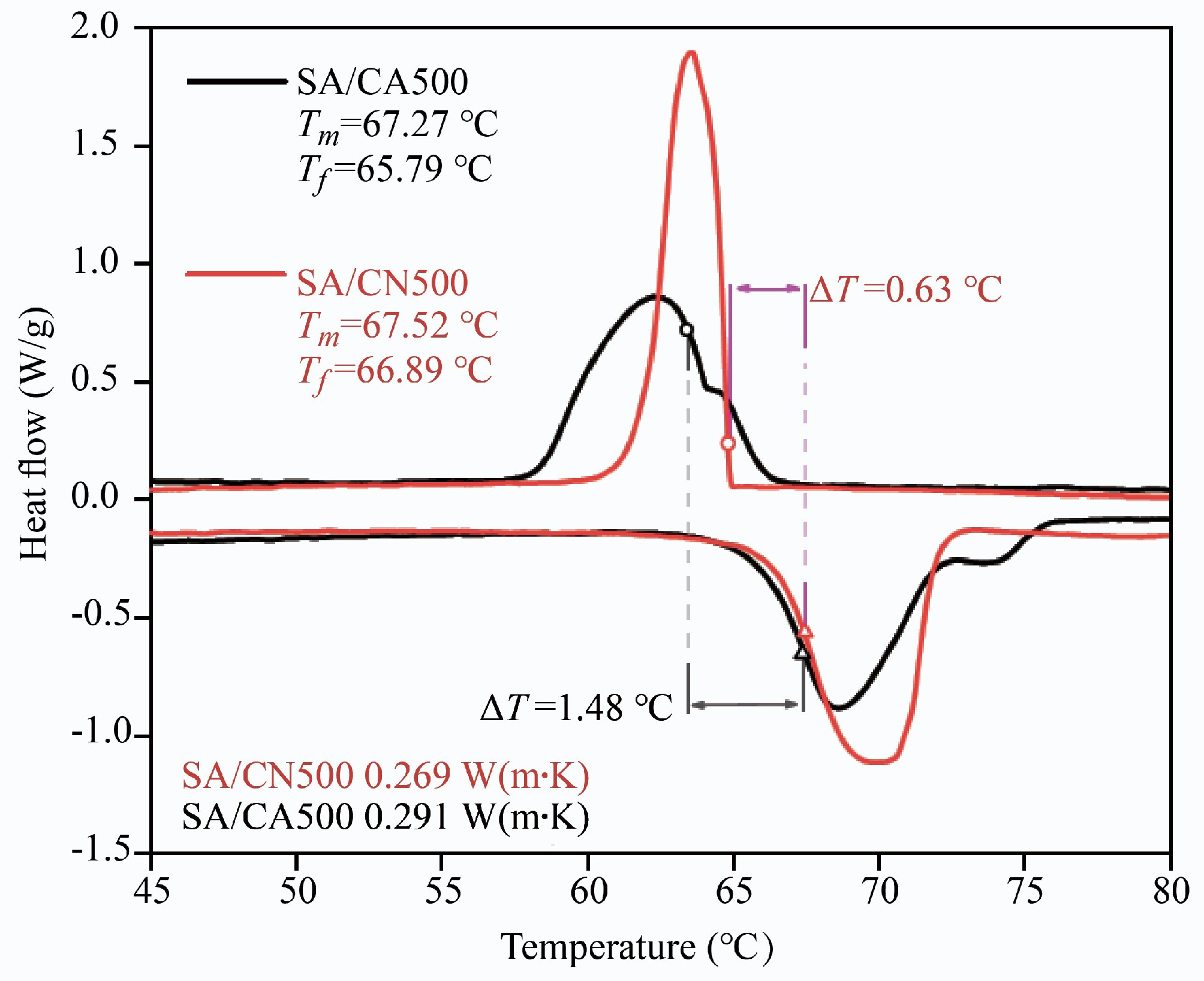

Thermal properties of SSPCM were evaluated by a differential scanning calorimeter (TGA/DSC 3+, Mettler Toledo Co., Ltd, Switzerland), where a 10 mg sample was placed in a platinum crucible and was linearly heated/cooled at 2 °C/min in the range of 30 to 90 °C under a N2 atmosphere. Phase change temperature (Tm/Tf), phase change enthalpy (ΔHm/ΔHf), and supercooling degree (ΔT) were calculated based on DSC curves. Wherein, the phase change temperature was defined as the onset temperature of the endothermic/exothermic peak in DSC curves[21,22]. Herein, the supercooling degree was the difference between the melting and freezing temperatures (ΔT = Tm − Tf).

Thermal conductivity was evaluated by a thermal constant analyzer (TPS2500, Hot Disk Co. Ltd, Sweden) at 25 °C, where the test time and power were set as 20 s and 20 mW, respectively.

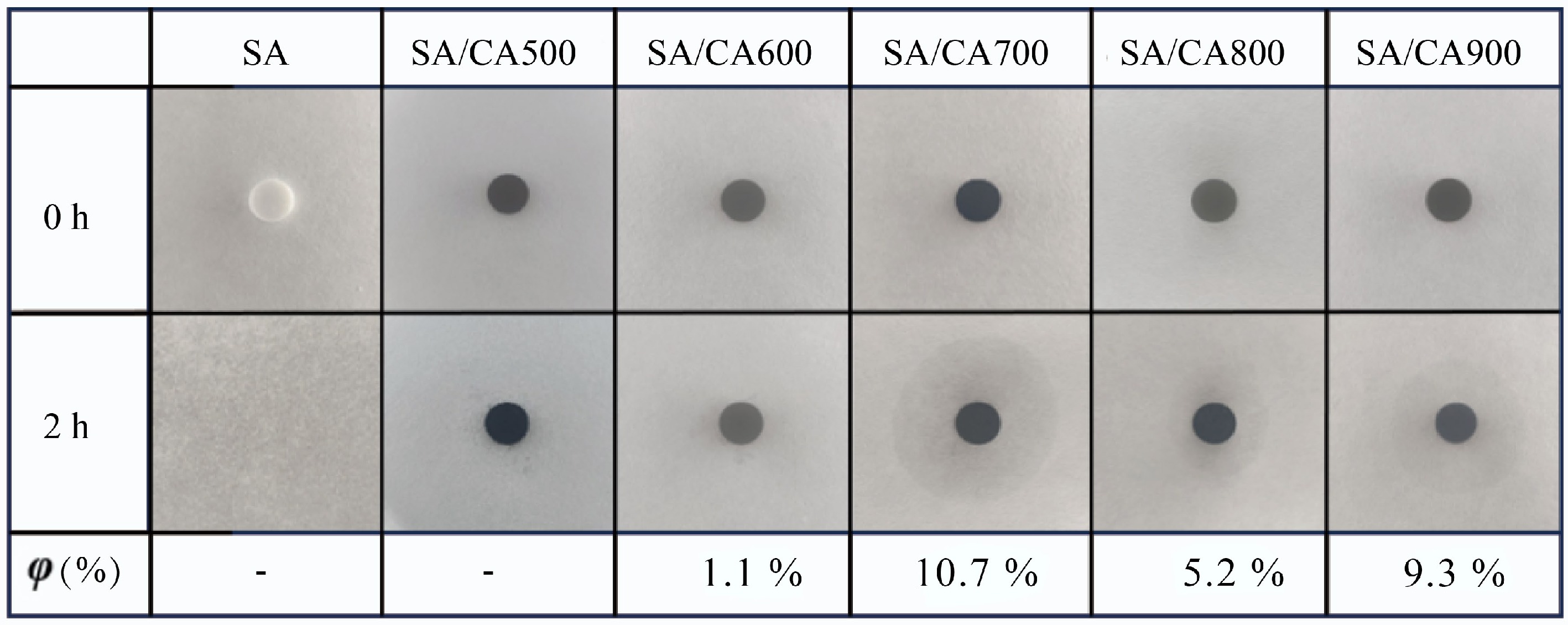

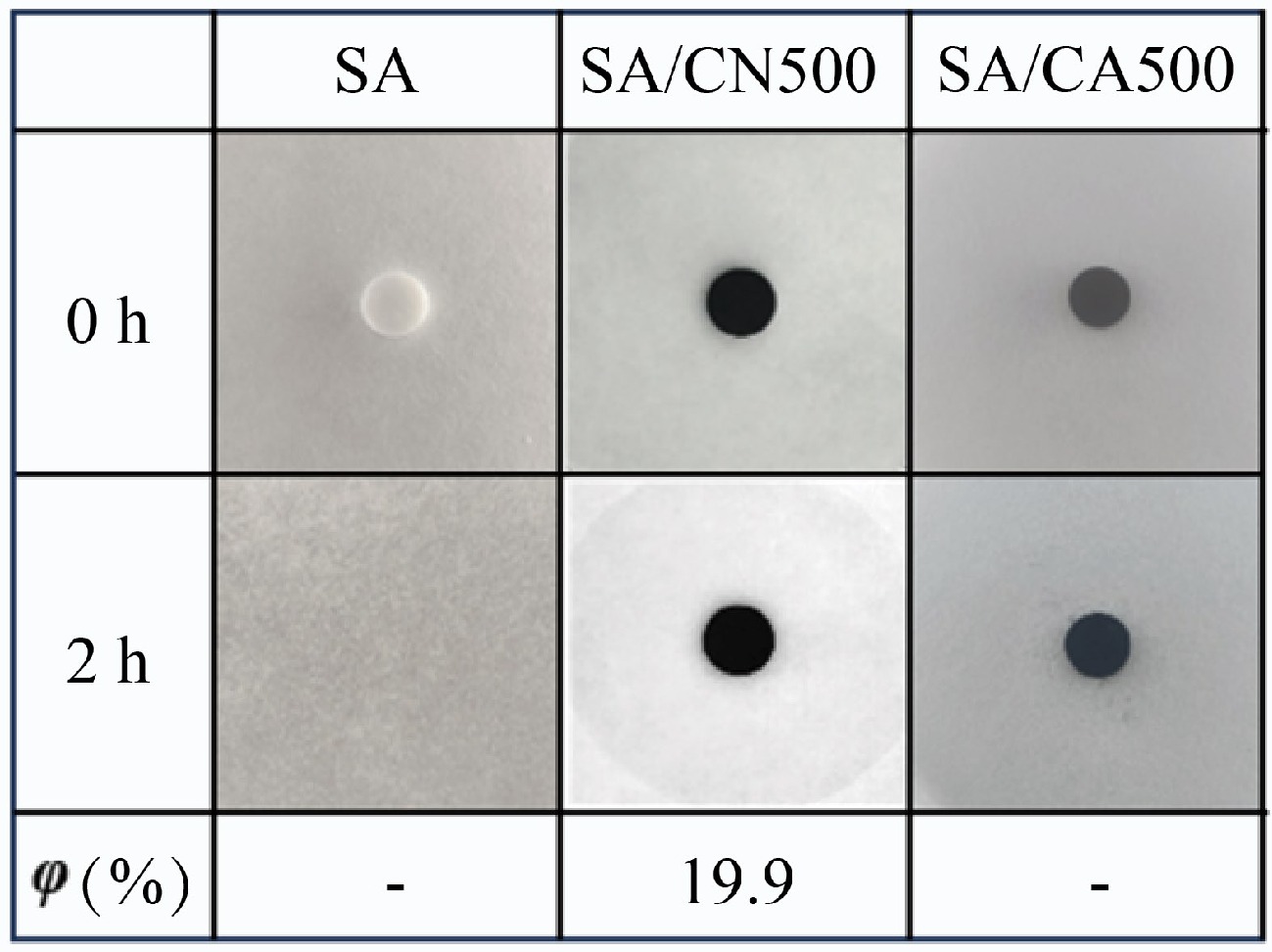

Shape stability was examined through the heating test. Samples were shaped into a tablet and placed on a filter paper, and heated at 90 °C for 2 h. The shaded area on the filter paper and the leakage ratio (φ) of SA/CAX were used to estimate shape stability. The leakage ratio represented the leakproof ability of the supports; it was calculated using Eq. (1),

$ \varphi = \frac{{{m_3} - {m_1}}}{{{m_2} \cdot \eta }} $ (1) where, m1 and m2 are the mass of the filter paper and SSPCM, respectively, in g; m3 means the mass of the filter paper after the leakage test, in g; η is the SA mass fraction in SSPCM, in %.

The structure and morphology of the samples were examined by a scanning electron microscope (Gemini SEM 300, Carl Zeiss Co., Ltd, Germany) with an acceleration voltage of 5 kV.

Pore structure, including specific surface area (SBET), total pore volume (Vtotal), and average pore diameter (Da), was determined by an automatic specific surface area analyzer (BELSORP-max, Microtrac Co., Ltd, Japan) at 77.3 K. Prior to the measurement, the samples were degassed at 150 °C for 24 h. Additionally, the pore diameter distribution of the micron pore structure (from 0.1 to 350 μm) was depicted by a mercury porosimeter (MicroActive AutoPore V 9600, Co., Ltd, USA). The samples were treated under vacuum conditions before testing.

Surface functional group was revealed through Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Tensor 27, Bruker Co., Ltd, Germany) in the range of 500 to 4,000 cm–1 with a 16-s scanning speed.

Crystal phase was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (SmartLab SE, Rigaku Co., Ltd, Japan) with a scanning rate of 5°/min in the angle range of 3° to 90°; the Cu kα radiation source was operated at 40 kV and 40 mA.

Phase change kinetics were analyzed by a differential scanning calorimeter to investigate the phase change behavior and thermal stability. Samples were heated at different rates (1, 3, 6, and 12 °C/min). The activation energy (E) was calculated via the Kissinger formula (Eq. [2]) based on the DSC curves,

$ \ln \left[\dfrac{\beta}{T_p^2}\right]=\ln \dfrac{AR}{E}-\dfrac{E}{R}\dfrac{1}{T_p} $ (2) where, β is the heating rate, in K/min; Tp means the peak temperature during the phase change process, in K; E is the activation energy of the phase change process, in kJ/mol. A is the pre-exponential factor, in min–1; R is the gas constant, in J/(kg·K).

-

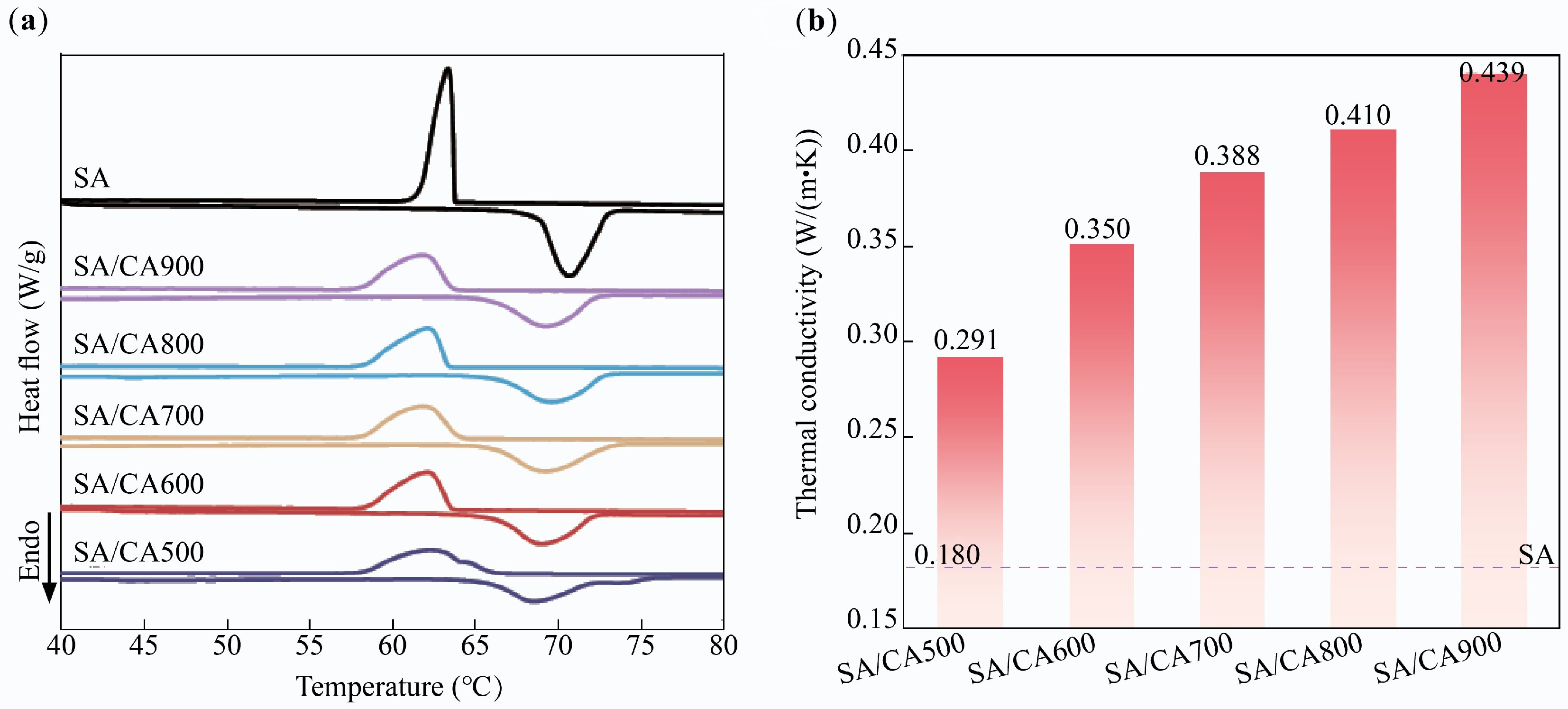

Figure 1a depicts the DSC curves of SA and SA/CAX. SA showed a single endothermic/exothermic peak, with the melting and freezing temperatures at 68.53 and 65.01 °C, respectively. SA/CAX had similar curves compared with SA, but its phase change temperatures were shifted. Specifically, SA/CAX demonstrated a lower melting temperature (67.21–67.51 °C) and a higher freezing temperature (65.79–66.99 °C). This is attributed to CAX promoting heterogeneous nucleation via an efficient thermal transfer path and a huge surface area[23,24]. As a result, the supercooling degree of SA/CAX was reduced to below 1.48 °C, which was lower than that of SA by 3.52 °C. A low supercooling degree is of beneficial for achieving more precise temperature control in practical applications.

Phase change enthalpy is a pivotal parameter for assessing the thermal storage density. Based on the mass fraction of SA, the theoretical enthalpy of SA/CAX was calculated as 132.99 and 132.07 J/g. It is easy to observe that the phase change enthalpy of SA/CAX was lower than its theoretical value (Table 1), which indicates that CAX restricts the thermal behavior of SA through interaction, resulting in enthalpy loss[25]. With the increased carbonization temperature of CAX, the melting enthalpy of SA/CAX rose from 117.66 to 125.42 J/g, illustrating that higher temperature weakens the interaction between CAX and SA. Although SA/CAX had a better phase change enthalpy at high carbonization temperature, the weakened interaction may lead to more serious leakage.

Table 1. Thermal properties of SA and SA/CAX

Sample Tm/Tf (°C) ΔHm/ΔHf (J/g) ΔT (°C) SA 68.53/65.01 221.65/220.11 3.52 SA/CA500 67.27/65.79 117.66/116.77 1.48 SA/CA600 67.21/66.80 119.47/117.03 0.41 SA/CA700 67.51/66.47 122.03/119.46 1.04 SA/CA800 67.22/66.99 123.11/118.07 0.23 SA/CA900 67.42/66.07 125.42/121.71 1.35 The influence of CAX on the thermal conductivity of SA was also investigated, and the results are listed in Fig. 1b. The thermal conductivity of SA was merely 0.180 W/(m·K), but it was increased significantly when encapsulated by CAX, where an efficient path accelerates the thermal transfer of SA inside[26]. Moreover, the thermal conductivity of SA/CAX elevated from 0.291 to 0.439 W/(m·K) as the carbonization temperature increases from 500 to 900 °C. This enhancement is attributed to the fact that higher temperature enhances the graphitization degree of CAX[27].

As a critical property in preventing the melting leakage of PCM, the shape stability of SA and SA/CAX is reflected by the heating test (Fig. 2). After heating for 2 h, the pure SA melted completely, while SA/CAX leaked less SA and maintained its original shape, proving the improved shape stability. However, SA/CAX exhibited leakage to different degrees as observed in the shaded area. Herein, the leakage ratio is utilized to estimate the leakproof ability of CAX. SA/CA500 exhibited no visible leakage, followed by SA/CA600 with a leakage ratio of 1.1%. With the increased carbonization temperature of CAX, the leakage ratio peaked at 10.7% for SA/CA700. This may be attributed to the collapse of the pore structure.

In summary, SA/CA500 possesses ideal shape stability, a reduced supercooling degree, and enhanced thermal conductivity; it was selected to compare with SA/CN500 for further assessing thermal storage performance.

Performance comparison of SA/CN500 and SA/CA500

-

From Fig. 3, a higher freezing temperature was measured in SA/CN500 (66.89 °C) than in SA/CA500 (65.79 °C), leading to a lower supercooling degree of 0.63 °C in SA/CN500. Nevertheless, the melting/freezing enthalpy of SA/CN500 was 114.26/112.58 J/g (Table 2), which was lower than that of SA/CA500 (117.66/116.77 J/g). This demonstrates that CA500 induces a relatively weakened restriction on the thermal behavior of SA. To sum up, despite a low supercooling degree in SA/CN500, a high thermal storage density was achieved in SA/CA500.

Table 2. Thermal properties of SA/CN500, SA/CA500, and reported SSPCM

Sample SA ratio

(wt%)Tm/Tf (°C) ΔHm/ΔHf

(J/g)ΔT (°C) Ref. SA/CN500 60 67.52/66.89 114.26/112.58 0.63 This study SA/CA500 60 67.27/65.79 117.66/116.77 1.48 This study cSA/PSC 30 50.20/51.00 70.60/67.00 − [28] SA/MFC 58 61.00/51.00 100.00/99.00 10.00 [29] SA/CSC15 35 52.52/52.05 76.69/76.00 0.47 [30] SA/CF − 67.80/67.30 99.6/101.5 0.50 [31] SA/CMS 40 68.2/64.5 84.91/67.71 3.70 [32] To further illustrate the advantage of thermal properties in SA/CA500, it is compared with the reported SSPCM based on SA-biomass-derived carbon in Table 2. It can be found that the phase change enthalpies of reported SSPCMs are concentrated below 100 J/g, while the synthesized SA/CA500 is as high as 117.66 J/g. This is owing to the high encapsulating capacity of CA500. The phase change enthalpy of SA/CA500 is over 17.6% higher than that of other samples, indicating its superior thermal storage density.

As shown in Fig. 3, the thermal conductivities of SA/CN500 and SA/CA500 were 0.269 and 0.291 W/(m·K), respectively. Both CN500 and CA500 could enhance the thermal conductivity of SA efficiently. Nevertheless, the thermal conductivity of SA/CA500 was 8.2% higher than that of SA/CN500. This suggests that CA500 with an aerogel structure constructs a more efficient path for the thermal transfer of SA. In practical application, the higher thermal conductivity of SA/CA500 makes it have an enhancement of thermal response[33].

Shape stability is compared in Fig. 4, the specific feature is that SA/CA500 maintained a stable shape, and SA/CN500 had an obvious leakage. The synthesized chitin aerogel exhibited a favorable structure; its derived carbon could prevent the melting leakage of SA well. Meanwhile, the test temperature was greater than the melting temperature of SA, that is to say, SA/CA500 showed excellent shape stability within the operating temperature range.

Characterization analysis of supports

-

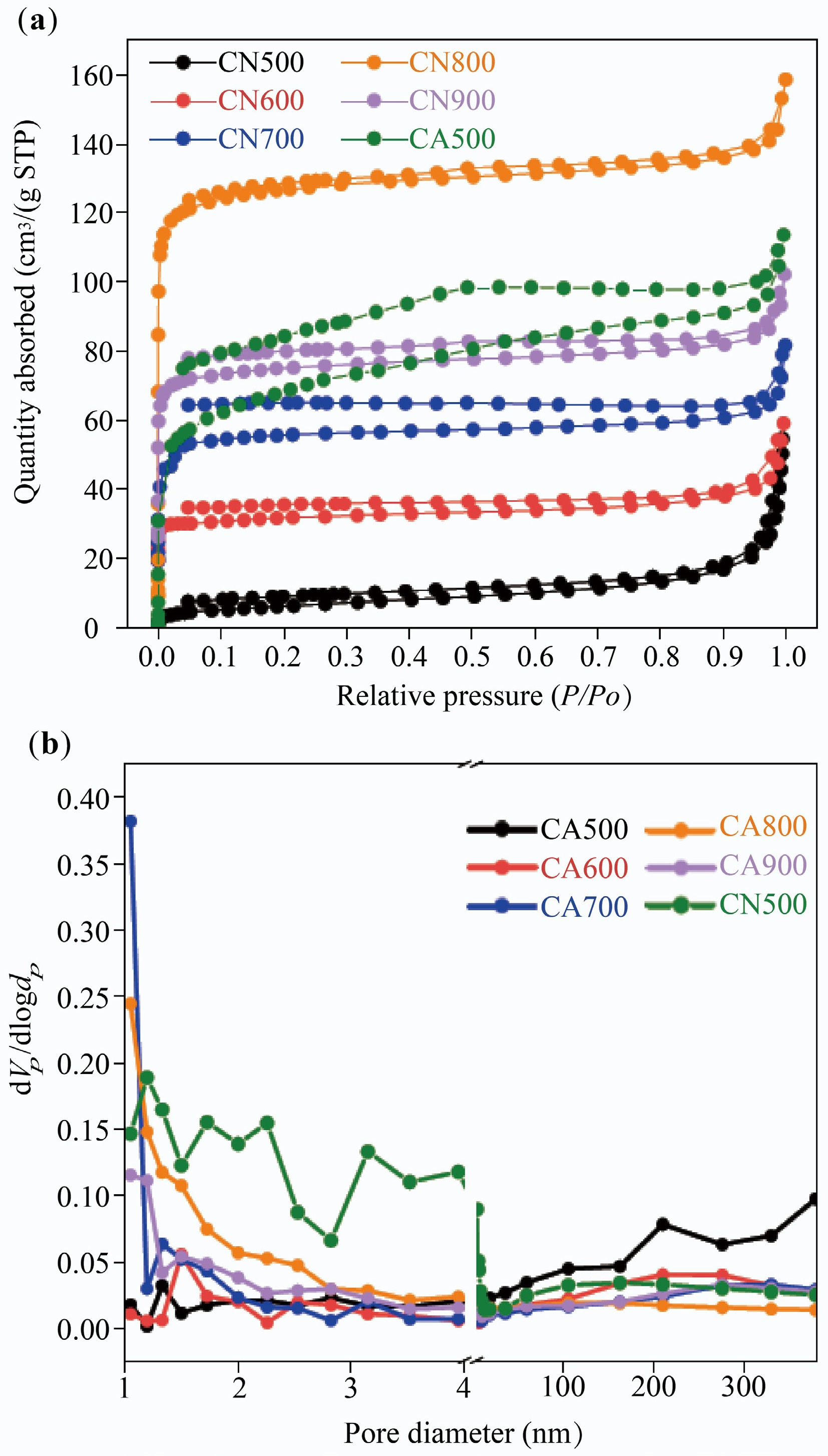

The N2 absorption-desorption isotherms of CN500 and CAX are described in Fig. 5a. It can be seen that the isotherms of CAX change from type II to type IV with increased carbonization temperature, illustrating the generation of micropores and mesopores. This phenomenon is also verified by pore diameter distribution (Fig. 5b), where the micropores and mesopores (below 5 nm) are increased gradually with temperature. As the carbonization temperature increased from 500 to 800 °C, the specific surface area and total pore volume of CAX (Table 3) increased from 20.97 to 470.98 m2/g and from 0.059 to 0.215 cm3/g, respectively. This is due to the decomposition of the oxygenated functional group in chitin[34].

Table 3. Specific surface area, pore volume, and average pore diameter of supports

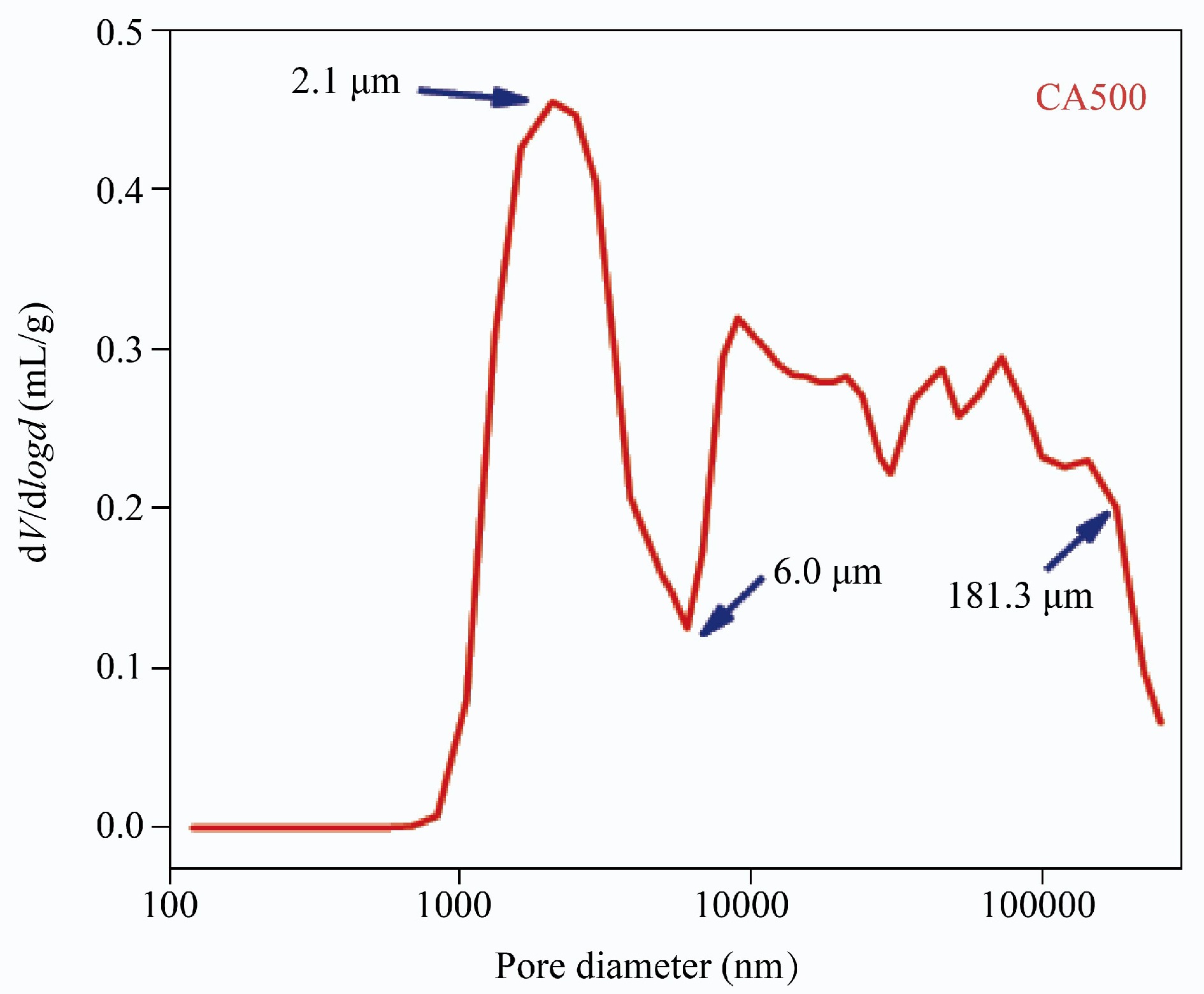

Sample SBET (m2/g) Vtotal (cm3/g) Da (nm) CA500 20.97 0.059 11.29 CA600 37.60 0.044 4.64 CA700 138.21 0.077 4.88 CA800 470.98 0.215 1.81 CA900 186.03 0.102 2.20 CN500 240.59 0.162 2.70 It is worth noting that the evolution of pore structure in CAX did not match the leakage of SA/CAX. For instance, CA800 displayed a higher specific surface area and total pore volume compared with CA500, but the leakage ratio of SA/CA800 was larger than that of SA/CA500. This may be ascribed to the fact that CA500, with an interconnected structure, had numerous macropores, providing a large storage space for encapsulating SA. To further quantify the macropores of CA500, the MIP test was performed in Fig. 6. Herein, CA500 presented a wide distribution in a range of 1.0 to 181.3 μm, with focus on 2.1 μm. The pore volume was calculated as 0.651 cm3/g, which proved a large storage space in CA500. However, this characteristic may collapse at high temperature; thus, CA800 showed a poorer encapsulating capacity than CA500.

Moreover, the pore structures of CN500 and CA500 are also compared in Fig. 5. CN500 exhibited a type I–IV isotherm equipped with an H3 hysteresis loop, meaning a micro-mesopore structure, and the pore diameter distribution concentrates at 1.19 nm. Its specific surface area and total pore volume were 240.59 m2/g and 0.162 cm3/g (Table 3), which were larger than those of CA500 (20.97 m2/g and 0.059 cm3/g). This is attributed to the fact that sublimated ice crystals during freeze-drying generate macropores in chitin aerogel, and reduce the specific surface area[35]. Although a huge specific surface area provides nucleation sites for enhancing heterogeneous nucleation, a small pore diameter impedes the infiltration of the SA molecule (2 nm)[36,37]. Therefore, a large amount of SA leaked from in SA/CN500.

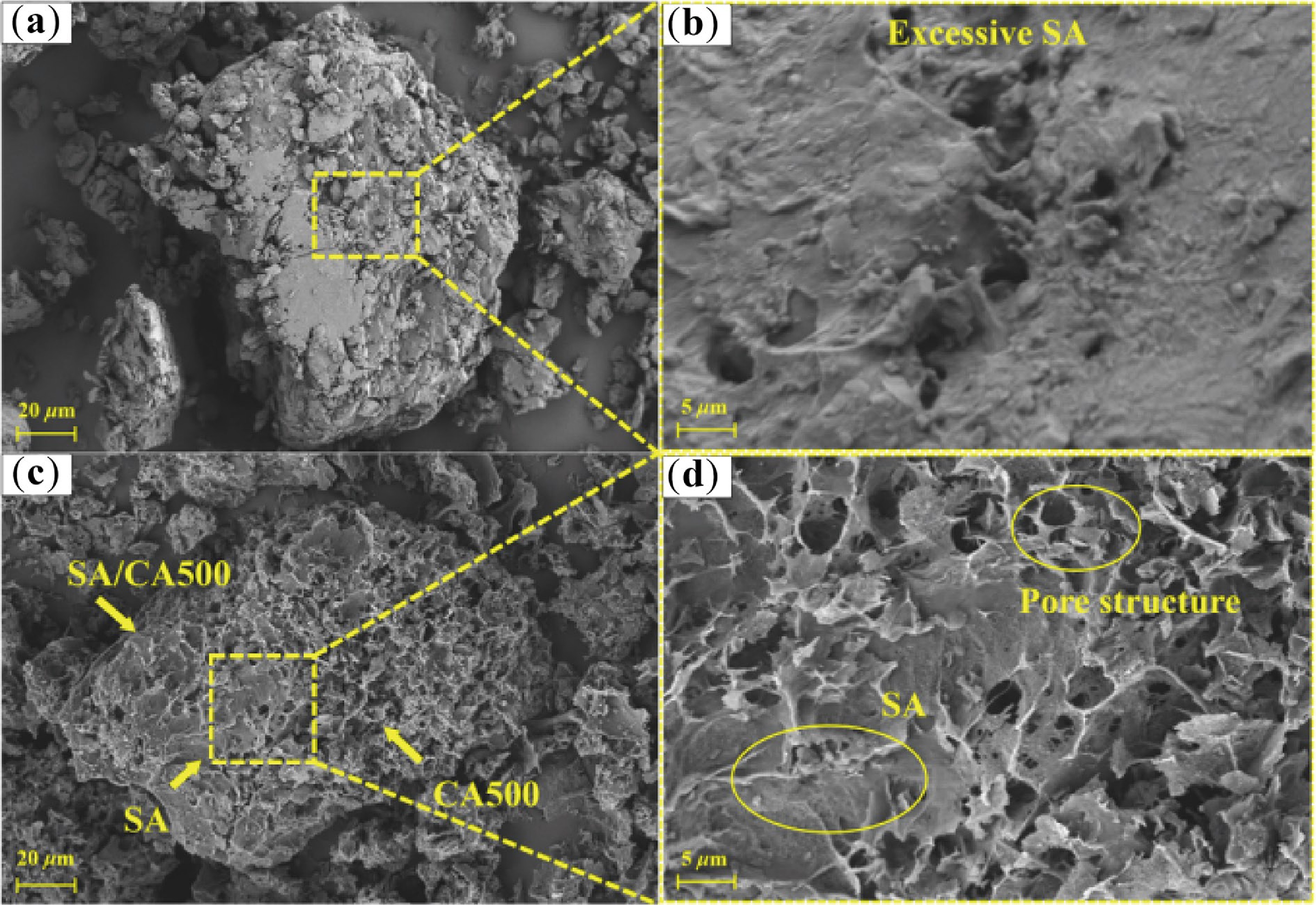

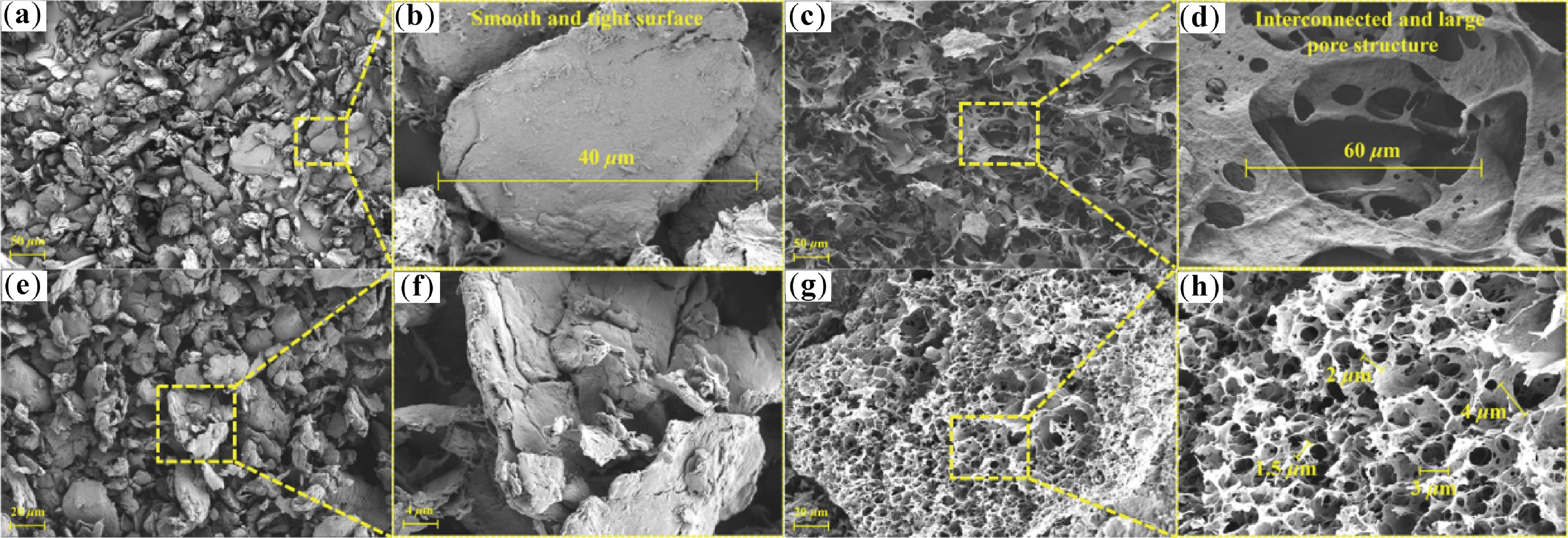

Based on the results from N2 absorption-desorption, CN500 and CA500 were characterized via SEM images to further analyze the difference in the physicochemical properties of the supports. Pure chitin in Fig. 7a, b is composed of discontinuous particles with smooth and tight surfaces; the particle size is about 40 μm. It can be seen from Fig. 7c, d that the synthesized chitin aerogel presented an interconnected pore structure with flat fibers randomly distributed within it and a large pore size of around 60 μm. This is ascribed to the fact that hydrogen bonds between chitin molecules are broken by NaOH at low temperature, and the dispersed molecules restructure the framework through hydrogen bonds after dialysis. Subsequently, ice crystal acts as the template and is removed to generate pore structure[38].

Figure 7.

(a), (b) SEM images of chitin, (c), (d) chitin aerogel, (e), (f) CN500, and (g), (h) CA500.

After carbonization, the particle of CN500 in Fig. 7e, f shrank, and showed slit-like pore structure. This was due to the decomposition of acetamido and oxygenated functional groups during carbonization[7]. By contrast, CA500 from Fig. 7g, h inherited the original structure of chitin aerogel, with abundant micron pores generated on the surface, but the pore size was reduced to 2 μm. This reduction in pore size enhances the capillary force of CA500 to prevent SA leakage[39]. According to the morphology of both supports, CA500 has more prominent merits: (1) the interconnected pore structure constructs a continuous thermal transfer path, thus improving the thermal conductivity of SA/CA500[40]; (2) the massive pore structure provides a large cavity to enhance the shape stability of SA[41].

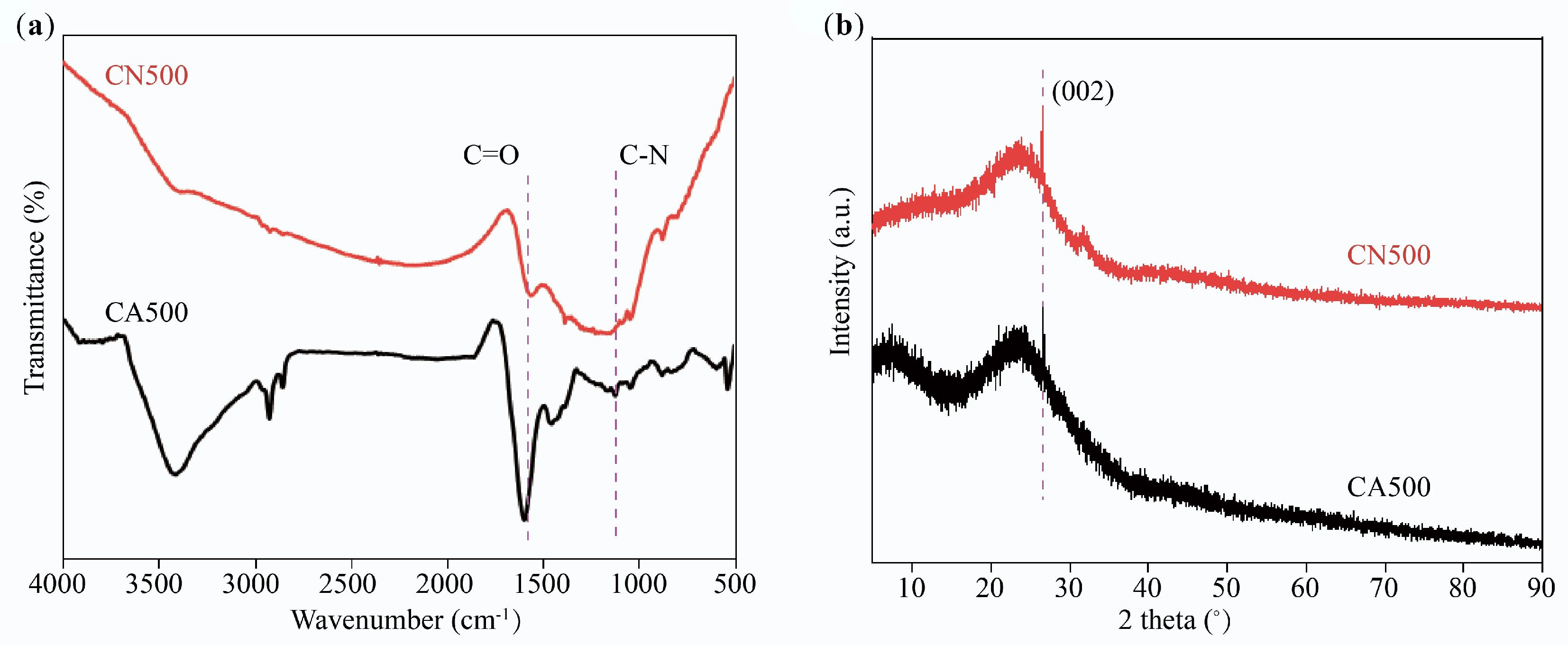

FTIR spectra and XRD patterns were employed to analyze the functional group and crystal phase of CN500 and CA500. As shown in Fig. 8a, CN500 and CA500 present the significant absorption bands at 1,135 cm and 1,577 cm–1, which are attributed to the C–N and C=O from the acetamido (CH3CONH-), which could induce the hydrogen bonds with the SA molecule[42]. In Fig. 8b, CN500 and CA500 have a broad amorphous structure peak within the scope of 16° to 28°, and a weakened diffraction peak at 26.7°, meaning the (002) facet of the graphite structure[43,44]. Thus, both supports mainly contain amorphous carbon equipped with a certain graphitization degree, and contribute to an enhancement in the thermal conductivity of SA/CN500 and SA/CA500.

Characterization analysis of SSPCM

-

The SEM images of SA/CN500 and SA/CA500 are shown in Fig. 9. It can be observed that SA/CN500 exhibited spherical particles with a size of 140 μm (Fig. 9a, b), which is larger than the CN500 particles (40 μm). This indicates that CN500 aggregates due to excessive SA coverage. On the other hand, CN500 was not prominently visible on the surface of SA/CA500, with only a layer of SA observed. Consequently, the dispersibility and small pore diameter of CN500 hindered its ability to encapsulate SA effectively, leading to leakage in SA/CN500. In contrast, since the interconnected pore structure can provide capillary force and storage space, SA is firmly filled into CA500. The framework of CA500 was observed clearly in SA/CA500 (Fig. 9c, d), and the major pores in CA500 are occupied by SA with only a few cavities. In summary, CA500 has the advantages of pore structure in comparison to CN500, making an improvement in the shape stability of SA.

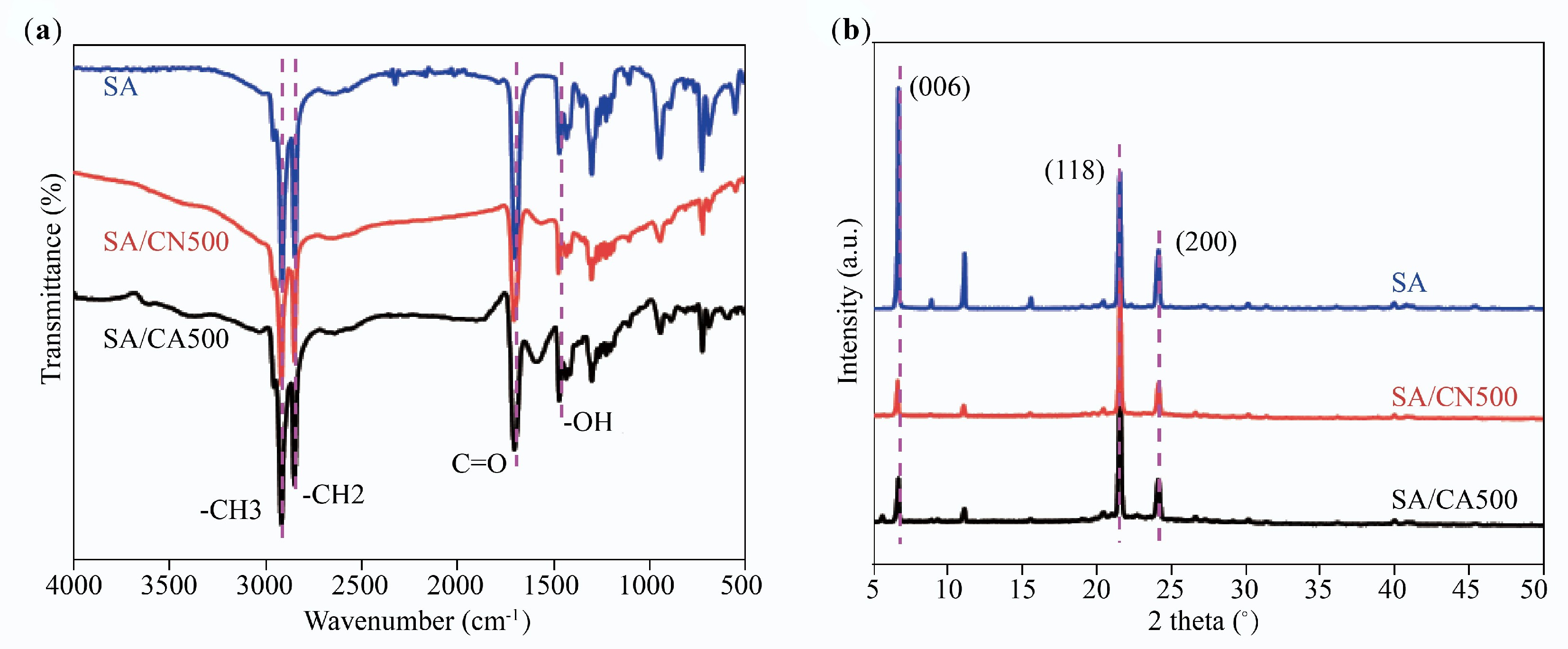

FTIR spectra from Fig. 10a were used to investigate the chemical compatibility between SA and the support. SA shows absorption bands at 2,911, 2,848, and 1,702 cm–1, representing the stretching vibration of –CH3, –CH2–, and C=O, respectively[8]. The absorption band at 1,469 cm–1 is assigned to the –OH bending vibration. As for SA/CN500 and SA/CA500, their spectra are composed of the absorption bands of each component; no additional bands are detected, proving a good chemical compatibility between SA and the support[45]. It is noted that the C=O bands of SA at 1,702 shift to 1,693 cm–1 in SA/CN500 and SA/CA500, this is caused by the hydrogen bond between SA and supports with N-doped surface[21]. The crystal phase of SA, SA/CN500, and SA/CA500 is revealed by XRD patterns, as illustrated in Fig. 10b. SA shows diffraction peaks at 6.7° for the (006) facet, 21.6° for the (118) facet, and 24.1° for the (200) facet[46]. These peaks are observed in SA/CN500 and SA/CA500, explaining that there is only a physical interaction between SA and the support. This is the reason why SA/CN500 and SA/CA500 maintain superior crystallinity and high phase change enthalpy after compositing.

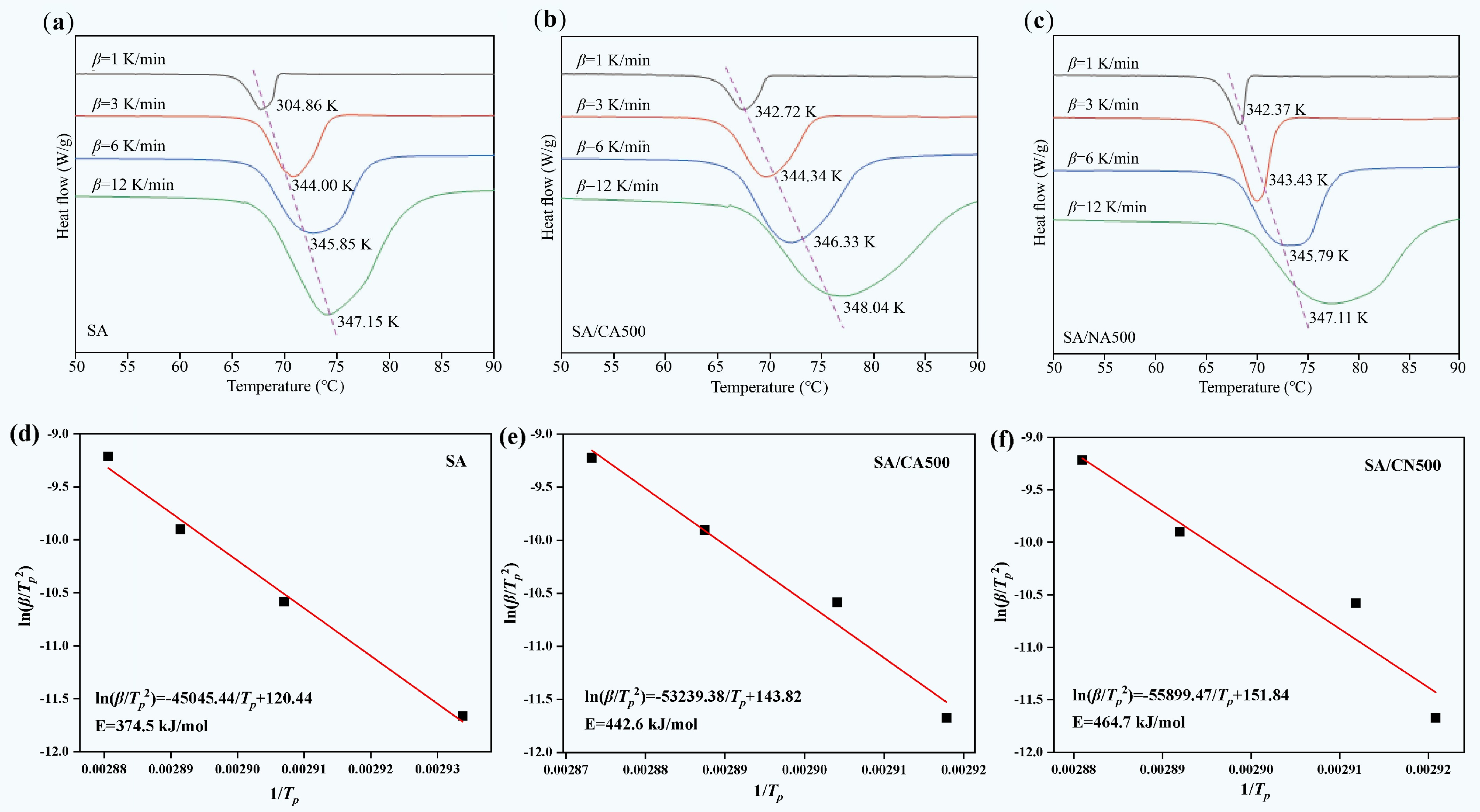

Figure 11a−c provides the DSC curves of SA, SA/CA500, and SA/CN500 at different heating rates. The endothermic peak became broader and shifted to a higher temperature with increasing heating rate, which is caused by the fact that the thermal behavior of SA needs more time to respond at a higher heating rate[47]. The linear fittings between ln(β/Tp2) and 1/Tp were estimated via the Kissinger equation Fig. 11d−f, and the activation energy (E) was calculated based on the fitting curves. The obtained values are listed in Table 4, with ESA = 347.5 kJ/mol; ESA/CA500 = 442.6 kJ/mol; ESA/CN500 = 464.7 kJ/mol, namely ESA/CN500 > ESA/CA500 > ESA.

Figure 11.

(a)−(c) DSC curves with different heating rates, and (d)−(f) linear fitting of Kissinger equation for SA, SA/CA500, and SA/CN500.

Table 4. Values of E and R2 of SA, SA/CA500, and SA/CN500

Sample SA SA/CA500 SA/CN500 E (kJ/mol) 347.5 442.6 464.7 r2 0.9915 0.9784 0.9435 Activation energy means the energy barrier for SA to undergo the phase change process, while the ESA/CA500 and ESA/CN500 are larger than ESA, indicating that SA/CA500 and SA/CN500 need more energy to cross the barrier[48]. This is attributed to the fact that the thermal behavior of SA is confined by CA500 and CN500; on the one hand, the SA is affected by the nanoconfinement originating from the micropore structure[49], and on the other hand, it is restricted through hydrogen bonds induced by the N-doped surface[50]. Moreover, it is noticed that the activation energy of SA/CN500 is higher than that of SA/CA500, describing an intensive restriction from CN500 with micropore structure on SA. This conforms to the result in thermal property that the phase change enthalpy of SA/CN500 is lower than that of SA/CA500. In conclusion, CA500 elevates the activation energy of SA; thereby, SA/CA500 possesses better thermal stability than SA during the phase change process.

Thermal reliability of SA/CA500

-

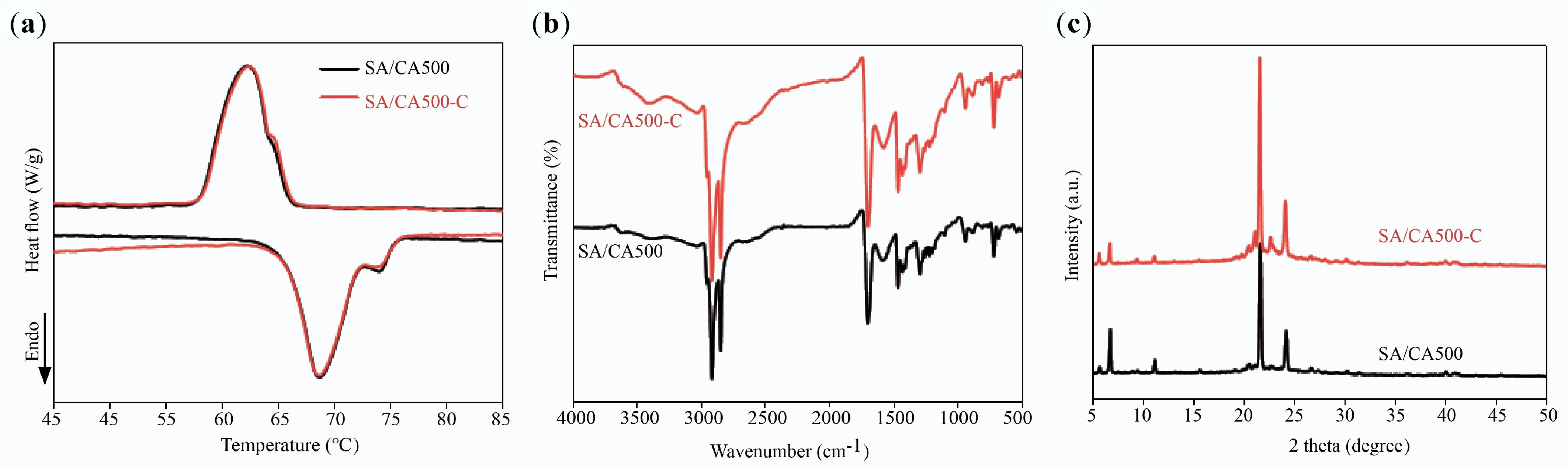

SA/CA500 displays more potential owing to its ideal thermal storage performance; its thermal reliability was assessed by subjecting it to 100 thermal cycles. Figure 12a depicts the DSC curves of SA/CA500 before and after thermal cycling, in which the curve for SA/CA500-C is almost the same as that for SA/CA500. More importantly, the melting temperature retains its original value, only the freezing temperature slightly shifts down by 0.3 °C, and the phase change enthalpy decreases by 3%. Figure 12b, c show FTIR spectra and XRD patterns after treatment with no apparent difference in diffraction peaks and absorption bands, demonstrating that the crystal and chemical structure of SA/CA500 remains undamaged during the repeated melting/freezing process. Therefore, SA/CA500 possesses desirable thermal reliability, or so-called cycling durability.

-

Chitin aerogel was constructed via NaOH/urea solution and freeze-drying; it was carbonized to encapsulate SA for preparing SA/CA500. In comparison to CN500, the aerogel structure in CA500 exhibits an interconnected pore structure and a huge pore size, which provides a large storage space and capillary force to prevent the melting leakage of SA. The N-doped surface of CA500 also induces hydrogen bonds with SA, further improving the shape stability of SA/CA500. The prepared SA/CA500 contains 60 wt% SA without leakage, and exhibits a high thermal storage density with a melting enthalpy of 117.66 J/g, a low supercooling degree of 1.48 °C, and a comparatively higher thermal conductivity of 0.291 W/(m·K). Meanwhile, CA500 and SA maintain favorable chemical compatibility; SA/CA500 maintains stable phase change temperature and a low variation in phase change enthalpy with 3% loss, even after 100 thermal cycles. From a phase change kinetics perspective, CA500 elevates the activation energy of SA from 347.5 to 442.6 kJ/mol, indicating an improvement in thermal stability for SA/CA500. Therefore, SA/CA500 has potential applications in thermal storage or can be used in electronic thermal management.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: all authors contributed to the study conception and design; material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Hengdi Li, Junchi Wang, Lingbin Kong; the first draft of the manuscript was written by Hengdi Li, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work is supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2025YFE0101500), Taishan Scholars Project Special Fund (tsqn202408225), Excellent Youth Science Fund in Shandong Province (ZR2023YQ046), and Development Plan of Youth Innovation Team of Shandong Provincial Colleges and Universities (2022KJ209).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Chitin was transformed into aerogel state and carbonized to prepare aerogel derived carbon.

Interconnected pore structure and huge pore volume of CA500 could provide ample storage space and capillary force.

The activation energy of SA during phase change was increased with CA500.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li H, Wang J, Kong L, Guo H, Xiao Q, et al. 2025. Chitin aerogel-derived carbon for shape-stabilized phase change materials with enhanced thermal energy storage. Sustainable Carbon Materials 1: e010 doi: 10.48130/scm-0025-0010

Chitin aerogel-derived carbon for shape-stabilized phase change materials with enhanced thermal energy storage

- Received: 10 October 2025

- Revised: 17 November 2025

- Accepted: 26 November 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: The practical application of organic phase change materials (PCMs) is normally restricted by their melting leakage. To address this issue, the chitin was transformed into an aerogel state and carbonized into carbon aerogel (CA) for stabilizing the typical PCMs of stearic acid (SA). Characterizations indicate that CA500 has an interconnected pore structure and a huge pore volume (0.651 cm3/g), which provide ample storage space and capillary force to encapsulate SA and prevent leakage. Meanwhile, the hydrogen bonds induced by the N-doped surface between SA and CA500 are also a crucial reason for the enhanced shape stability of SA/CA500. The prepared SA/CA500 possesses superior shape stability without leakage when encapsulating 60 wt% SA, and exhibits a higher thermal storage density with a melting enthalpy of 117.66 J/g. CA500 and SA exhibit ideal chemical compatibility; SA/CA500 maintains its thermal property after 100 thermal cycles, illustrating good thermal reliability. From a phase change kinetic perspective, CA500 elevates the activation energy of SA from 347.5 to 442.6 kJ/mol, indicating an improvement in thermal stability for SA/CA500.

-

Key words:

- Thermal storage /

- Phase change materials /

- Chitin aerogel /

- Porous carbon