-

The increasing global expansion of the automotive industry has led to a concomitant rise in the generation of waste tires worldwide. According to the European Tyre and Rubber Manufacturers' Association, more than 3.1 million tons of tires are used annually in the European Union (EU)[1]. Due to their high durability and resistance to biodegradation, the disposal and recycling of end-of-life tires present considerable environmental and technical challenges[2]. The majority of used tires are stockpiled in open environments or landfills, which poses significant environmental hazards[3,4]. Tires not subjected to stockpiling are predominantly disposed of via incineration, a process that releases substantial quantities of toxic gases requiring advanced emission control systems[5].

A promising alternative to conventional disposal methods is the recycling of tires into rubber granulate. This granulate, after minimal processing, is employed in various applications, including sports facilities and synthetic turf systems. One of the most widespread uses of rubber granulate is as a surface material in children's playgrounds. Owing to its advantageous physicochemical properties and cost-effectiveness, this recycled material has seen increased adoption in such applications[6].

Rubber derived from tire recycling contains fillers such as aromatic oils, which may harbor polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) at concentrations up to 700 mg/kg[7]. However, quantitative data on PAH concentrations in recycled rubber granulate are scarce. It is hypothesized that PAHs persist in the granulate matrix and that, under natural environmental processes and upon contact with soil or water, they may be gradually released. Consequently, the use of rubber granulate in applications involving human contact, particularly with children, presents a potential exposure pathway to PAHs. Moreover, PAHs may leach from the granulate into soil and water matrices, serving as a non-negligible source of environmental contamination. Existing investigations report PAH concentrations on rubber surfaces, including playgrounds and pavements, ranging from 23.4 mg/kg to as high as 5,744 mg/kg[6].

Recent literature[8−11] highlights the environmental and health risks associated with PAHs leaching from rubber materials, underscoring the critical need to evaluate this phenomenon in relation to the raw recycled materials used in rubber surface production. Of particular importance is the determination of the bioavailable fraction of PAHs, as this fraction directly correlates with toxicological effects. Measurements of total PAH content alone may overestimate risk if PAHs are strongly adsorbed within the rubber matrix. These contaminants can exert acute and chronic effects on microorganisms, invertebrates, and plants, with several works demonstrating size-dependent differences in leaching potential and toxicity. Over the past few years, growing attention has been given to the ecotoxicological effects of tire-derived materials, as their complex chemical composition makes them a potential source of multiple contaminants. While studies have quantified selected pollutants[12,13], far fewer have combined chemical analysis with biological testing to capture the actual ecological impact of rubber granulates. Such integration is essential, since the presence of contaminants like PAHs or metals does not always directly reflect their bioavailability or toxic potential[14]. A combined chemical–ecotoxicological approach therefore provides a more realistic assessment of environmental risk and is particularly needed in the case of rubber granulates used in public spaces. Complementary ecotoxicological assays provide a functional assessment of potential environmental hazards. To date, such comprehensive studies have not been reported. Considering the extensive application of rubber granulate in artificial turf for sports fields, playground surfaces, running tracks, noise barriers, and impact-absorbing underlays, a systematic investigation is warranted. Smaller particles, in particular, provide a larger reactive surface area and thus may enhance the mobility and bioavailability of hazardous compounds. This size-dependent behavior exerts a direct influence on both the total concentrations and the bioavailable fraction of PAHs, as finer particles with greater surface reactivity facilitate enhanced leaching and thereby increase the potential for biological uptake[15]. Nevertheless, most available studies have either focused on tire wear particles in road runoff or on chemical characterization of recycled granulate, with far fewer works integrating chemical analyses with ecotoxicological testing across different particle size fractions.

The objective of the present study was to quantify both total and bioavailable PAH concentrations in rubber granulate of varying particle sizes derived from recycled vehicle tires, which directly correlates with toxicological effects, and the use of complementary ecotoxicological assays that provide a functional assessment of environmental hazard. To date, however, systematic evaluations of both chemical contamination and ecological toxicity of tire granulate across particle sizes are lacking. Addressing this need, the present study investigates how particle size influences contaminant content, leaching behavior, and toxicity, with a focus on the potential environmental and human health risks arising from the use of tire-derived granulate in public spaces.

-

Granulate was collected from the Tire Recycling Plant in Poniatowa (Poland). Three size fractions of the granulate (< 1.5, 1–3, and 3–6 mm) were taken from different storage areas, placed into plastic bags, and subsequently transported to the laboratory for further chemical and ecotoxicological assessments. The physico-chemical characteristics of rubber granulates were determined by standard methods. The pH was determined potentiometrically after 24 h of equilibration in 1 M KCl, using a liquid-to-biochar ratio of 10:1. The contribution of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and nitrogen (N) was determined using a CHN analyzer (Perkin–Elmer 2400). Sulphur (S) content was measured by X-ray fluorescence (XRF). Low-temperature nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (77.4 K) were obtained to determine the textural parameters of rubber granulates (Micromeritics ASAP 2405 N). The BET method was applied to calculate the specific surface area (SBET). The physico-chemical characteristics of the granulate are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Physicochemical properties and elemental composition of studied rubber granulate fractions

Parameter Granulate size (mm) < 1.5 1–3 3–6 C (%) 74.66 A 81.65 A 77.25 A H (%) 6.88 A 6.74 A 7.61 A N (%) 2.57 A 0.67 B 0.68 B O (%) 5.65 A 4.42 B 8.07 C S (%) 0.44 A 0.46 A 0.30 B ASH (%) 9.80 A 6.06 B 6.09 B H/C 1.11 A 0.99 A 1.18 A O/C 0.06 A 0.04 B 0.08 A (O + N)/C 0.09 A 0.05 B 0.09 A C/N 33.89 A 142.17 B 133.19 B SBET (m2/g) 0.07 − − Vmicro (cm3/g) 0.000033 − − Smicro (m2/g) 0.0860 − − pH 5.87 A 7.42 B 7.48B Different letters in rows mean statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between rubber granulate fractions. Total (Ctot) polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) content

-

Approximately 10 g of dry rubber granulate were placed into extraction thimbles. To each thimble, 0.5 g of anhydrous sodium sulfate (VI) and powdered metallic copper were added. The samples were then spiked with a deuterated internal standard (Σ16 PAHs in cyclohexane, 100 ng/mL of each PAHs, Dr. Ehrenstorfer, Germany) and extracted with ethyl acetate at 100 °C for 24 h using a Soxhlet apparatus (BEHR, Germany). After extraction, the solvent was evaporated to a final volume of 1 mL using a rotary vacuum evaporator (RVC 2-25 CD plus, Martin Christ, Germany). The concentrated extracts were purified with an open micro glass column (150 mm × 7 mm ID) packed, from bottom to top, with quartz wool, activated silica gel (activated for 5 h at 350 °C, containing 10% Milli-Q water, 3 cm bed height), and anhydrous sodium sulfate. The column was prewashed with 5 mL of heptane prior to sample loading. The concentrated extract was applied to the column to separate PAHs from other polar interfering compounds. Elution was performed with 10 mL of heptane. The eluted fractions were again concentrated to 1 mL using a rotary evaporator (RVC 2-25 CD plus, Martin Christ, Germany) and transferred to a vial sealed with a Teflon-lined septum for PAH analysis.

Qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted using a gas chromatograph (Trace 1300) coupled with a mass spectrometer (ISQ LT) (GC–MS, Thermo Scientific), operating in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode with a single quadrupole detector. Separation was achieved using an Rxi®-5ms fused silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm film thickness, Restek, USA) with helium (He) as the carrier gas (flow rate of 1 mL/min). The GC oven temperature program was as follows: initial hold at 50 °C for 2 min, ramp to 100 °C at 20 °C/min, then to 200 °C at 5 °C/min, followed by an increase to 300 °C at 20 °C/min, with a final hold at 300 °C for 12 min. Injector and detector temperatures were set at 280 and 300 °C, respectively. Mass spectral data were acquired in electron ionization (EI) mode, with SIM performed using molecular ions specific to each PAH.

Freely dissolved PAHs fraction (Cfree)

-

The freely dissolved PAHs (Cfree) content was determined using the polyoxymethylene (POM) method according to Hale et al.[16]. Briefly, two POM strips were placed into a flask containing 1 g of rubber granulate and 40 mL of 0.2 g/L sodium azide (NaN3) solution. Samples were mixed for 30 d, after which strips were removed, cleaned in Milli-Q water, and dried with some lint-free tissue (Kleenex). The POM strips were then extracted with 20 mL of acetone/heptane (20:80 v/v) for 48 h by horizontal shaking. Before the extraction, samples were spiked with deuterated standards (Σ16 PAHs in cyclohexane, 100 ng/mL of each PAHs, Dr. Ehrenstorfer, Germany). The extracts were concentrated to 1 mL. The final extract was analyzed by GC–MS following the procedure described above.

Collembolan test

-

Folsomia candida (obtained from the Department of Ecotoxicology, Institute of Environmental Protection – National Research Institute in Poland) was cultured in plastic containers filled with plaster of Paris enriched with charcoal, and maintained under controlled conditions (T = 20 °C; 12/12 h light/dark photoperiod). The cultures were maintained by weekly feeding and watering, as well as the removal of spoiled food and dead individuals. Ecotoxicity tests were conducted using juvenile F. candida individuals aged 11–12 d, which were obtained by synchronizing egg laying by F. candida adults. The ISO guideline number 11,267 for testing chemical effects on the reproduction of springtails was followed[17]. The tests were carried out in Petri dishes containing 30 g of moist OECD soil (control) or OECD soil amended with granular rubber at concentrations of 1%, 5%, or 10%. Three replicates were prepared for each treatment. To ensure the accuracy of the test, F. candida juveniles were first examined under a microscope to confirm their healthy appearance. Subsequently, ten randomly selected juveniles were transferred into each test Petri dish. The dishes were incubated under controlled conditions at 20 °C with a 12/12 h light/dark photoperiod. Soil moisture was monitored weekly by weighing the dishes, and any loss of moisture was replenished with Milli-Q water as needed. The animals were also fed with yeast during the test. After four weeks, the test dishes were processed to assess springtail mortality and reproduction. Each dish was emptied into a 200 mL beaker, and 100 mL of Milli-Q water was added. The mixture was gently stirred to allow all springtails to float to the surface. The numbers of adults and juveniles were then counted manually after photographing the water surface using a digital camera.

Phytotoxkit F test

-

The toxicity of rubber granulate was evaluated using the plant-based Phytotoxkit F bioassay[18]. This test assesses the reduction or inhibition of seed germination and early root growth after 72 h of exposure of selected higher plant seeds (Lepidium sativum in this study) to the test material, compared to control samples in reference OECD soil. Each bioassay was conducted in triplicate. Rubber granulate was incorporated into the reference OECD soil at concentrations of 1%, 5%, and 10%. Then distilled water was evenly applied across the soil surface, and ten Lepidium sativum seeds were placed at equal distances (1 cm) along the central ridge of each plate on filter paper over the hydrated reference soil. After closing, the plates were positioned vertically in a holder and incubated at 25 °C for 72 h. At the end of the incubation, digital images of the germinated plants were captured. Root lengths and germination rates were analyzed using Image Tool 3.0 for Windows (UTHSCSA, San Antonio, USA). The percent inhibition of seed germination (SG) and root growth inhibition (RGI) were calculated according to Eq. (1).

$ \mathrm{S}\mathrm{G}\;\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\;\mathrm{R}\mathrm{G}\mathrm{I}=\rm\left(\dfrac{X-Y}{X}\right)\times 100{\text{%}}$ (1) where, X represents mean seed germination or root length in the control OECD soil; Y represents mean seed germination or root length in OECD soil amended with granulate rubber.

Leachates toxicity

-

Leachates from rubber granulates were obtained according to the standard EN 12457-2 protocol[19]. The Microtox® assay (Microtox M500 analyzer) was employed to assess the inhibition of bioluminescence in the bacteria Aliivibrio fischeri, following the standard test protocol[20]. The luminescence emitted by bacteria exposed to the rubber granulate extract was compared to that of a control. Inhibition of bioluminescence was evaluated over a 15 min exposure period using the 81.9% basic screening test protocol (MicrotoxOmni software).

Additionally, a similar test—the Phytotestkit F test—was performed on the samples. The procedure was identical in all but one aspect: a water extract from rubber granulate was used instead of the raw material. Briefly, OECD soil was replaced by a sponge covered with a thick filter. Then, 20 mL of extract was evenly applied to the surface of the filter. A thin filter paper was placed on top of the thick one. Finally, ten plant seeds were positioned at equal distances near the center ridge of the test plate on a filter paper positioned over the hydrated sponge. Incubation conditions were the same as in the Phytotoxkit F test. The analysis and length measurements followed the same procedure as for the Phytotoxkit test. This test was performed in three replicates for raw (100% extract concentration) and diluted extracts (10% and 50% extract concentrations).

An iCAP 7000 Series model (radial viewing mode) ICP OES instrument (Thermo, USA) was used to determine the potentially toxic elements contents (Zn, Cu, Cr, Ni, Cd, Pb, Co) in granulate rubber leachates. Leachates for analysis were prepared as described above. The operational conditions of the ICP OES were optimized to achieve the maximum signal-to-noise ratio.

Data analysis

-

The concentration of PAHs on POM passive samplers (CPOM) was calculated according to the Eq. (2):

$ {\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{P}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{M}}\left(\mathrm{ng/kg}\right)=\dfrac{{\mathrm{m}}_{\mathrm{P}\mathrm{A}\mathrm{H}}\left(\mathrm{n}\mathrm{g}\right)}{{\mathrm{m}}_{2\mathrm{P}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{M}}\left(\mathrm{k}\mathrm{g}\right)}$ (2) where, mPAH is the mass of PAHs (ng) determined via GC-MS and m2POM is the mass of two POM passive samplers (kg).

Freely dissolved PAHs concentrations (Cfree) were calculated according to Eq. (3):

$ \rm{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{f}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{e}}\left(\mathrm{ng/L}\right)=\dfrac{{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{P}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{M}}\left(\mathrm{ng/kg}\right)-{\mathrm{C}}_{control}\left(\mathrm{ng/kg}\right)}{{\mathrm{K}}_{\mathrm{P}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{M}-\mathrm{w}}\left(\mathrm{L/kg}\right)} $ (3) where, Cfree is the aqueous phase concentration (the pollutant concentration that is considered bioavailable) (ng/L), CPOM is the measured concentration in the sample (ng/kg) , Ccontrol is the measured concentration in the control (ng/kg), and KPOM-w is the predetermined POM-water partitioning coefficient (L/kg) specific to each PAH compound obtained from Hawthorne et al.[21]. Absolute recoveries from a POM spiking experiment were 64.8%–92.6% for all 16 PAHs.

The solid-water distribution coefficient calculation (Kd) was calculated using the following Eq. (4):

$ \rm{\rm{Log}}\; {K}_{d}\left(L/kg\right)=\dfrac{{C}_{total}\left({\text μ}g/kg\right)}{{C}_{free}\left({\text μ}g/L\right)}$ (4) where, Ctotal is the PAH concentration in solid samples (μg/kg), and Cfree is the freely dissolved concentration in water (μg/L).

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical analyses were conducted using OriginPro 2024 (OriginLab Corporation, USA). All mean values represent triplicate measurements. Pearson's correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationships between ecotoxicological endpoints and PAH concentrations, with significance set at p ≤ 0.001. In addition, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used to evaluate differences among the tested groups, considering p ≤ 0.05 as statistically significant.

-

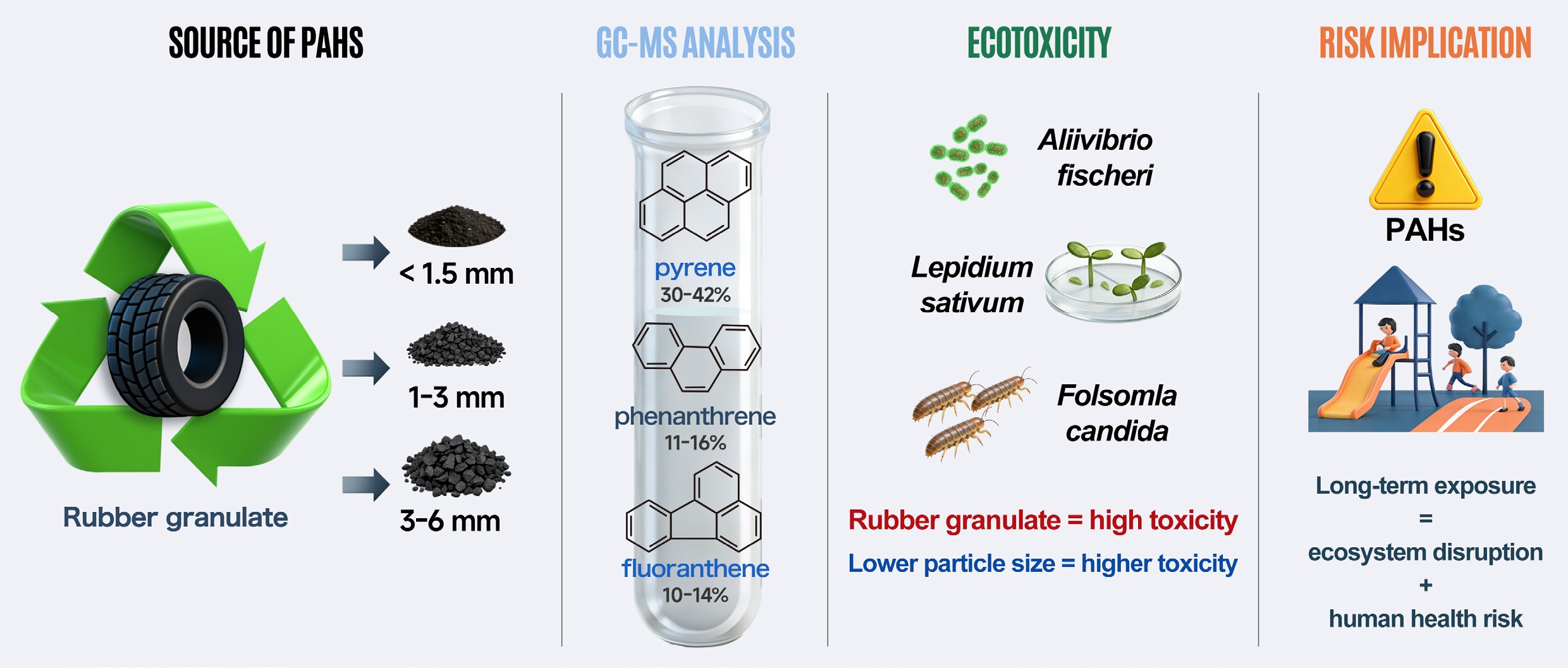

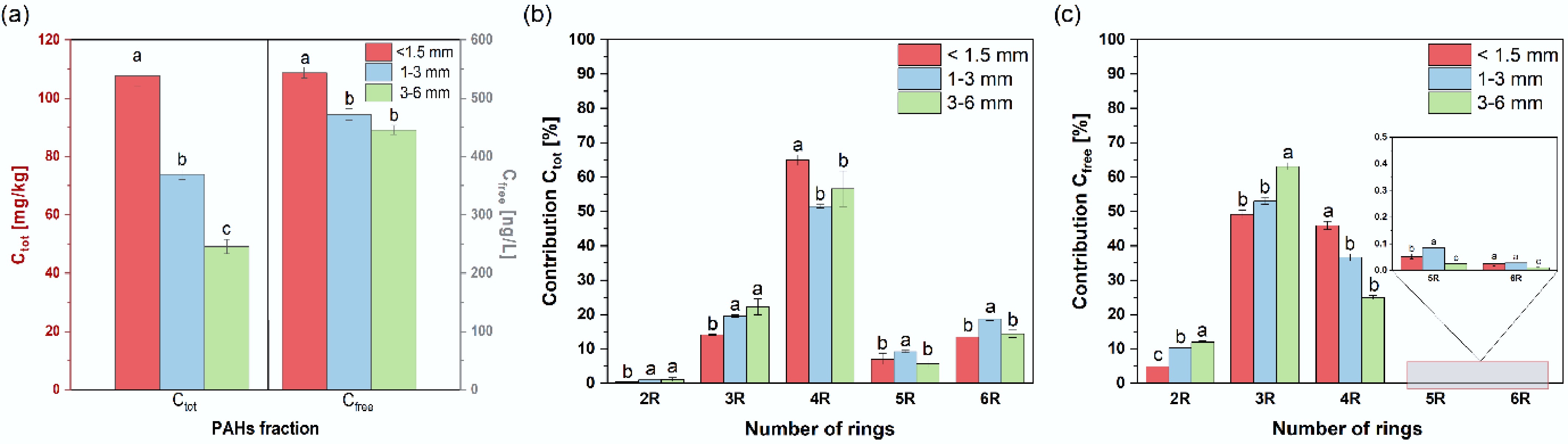

The total content of 16 PAHs (Σ16 PAHs) varied depending on the particle size of the granulate (Fig. 1a). The highest Σ16 PAH concentration was observed in the smallest granulate fraction, with a measured value of 107.6 mg/kg. As the granulate diameter increased, the PAH content in the tested material decreased. In fact, the smallest-size granulate had more than twice the PAH content of the largest-size fraction.

Figure 1.

The Ctot Σ16 PAHs and Cfree Σ16 content in (a) granular rubber, (b) contribution of Ctot Σ16 PAHs, and (c) Cfree Σ16 PAHs based on the number of rings. Dashed bars represent n-BC amendment. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). The letters indicate significant differences among particle sizes (p ≤ 0.05).

Regardless of granulate size, 4-ring PAHs consistently dominated the composition of granulate (Fig. 1b), accounting for 51.5% to 65.0% of total PAHs depending on the fraction. The next most abundant groups were 3-ring PAHs (14.1% to 22.2%), followed by 6-ring (13.5% to 18.7%) and 5-ring PAHs (5.8% to 9.2%). Naphthalene was present at the lowest levels, constituting less than 1.1% of Σ16 PAHs in all samples. Among individual PAHs, pyrene (29%–42%), phenanthrene (11%–16%), and fluoranthene (10%–14%) were predominant (Supplementary Table S1). The proportion of benzo(a)pyrene, regarded as a representative PAH, ranged from 2.4% to 3.1% (Supplementary Table S1). The high PAH content in rubber waste is mainly due to the presence of highly aromatic oils in the material. The results of this study are consistent with those reported by other authors[22,23] regarding PAH levels in rubber, rubber granulate, and tires. Previous studies found Σ16 PAH concentrations ranging from 77 to 82 mg/kg. The PAH profiles observed here also align with earlier research[6,23]. The higher PAH concentrations seen in some granulate fractions in this work may be because the material was fresh and had not undergone aging or use, which likely affected PAH levels. Of course, differences in material composition can also significantly influence PAH content in rubber products.

Depending on granulate size, the distribution of individual PAHs varied. As the granulate diameter increased, the percentage of 3-ring PAHs also increased (Fig. 1b). The trends for other PAH groups were less obvious. For example, the highest contribution of 4-ring PAHs was in the finest fraction (< 1.5 mm), while the highest levels of 5- and 6-ring PAHs appeared in the mid-sized granulate (1–3 mm).

Recent investigations into recycled rubber (CR) and tire-derived rubber granulate underscore significant environmental and human health concerns related to their chemical composition and behavior under environmental stressors. Skoczyńska et al.[24] developed a comprehensive analytical method capable of detecting a wide array of organic compounds in CR, including previously undetected heterocyclic and methylated PAHs, as well as aromatic amines. Their findings revealed that PAH concentrations surpassed EU regulatory thresholds, emphasizing the necessity for more expansive chemical screening and long-term degradation studies. Lu et al.[25] further demonstrated the dynamic nature of contaminant release, showing that ultraviolet (UV) irradiation dramatically increases the leaching of PAHs and metals like Zn—up to 24-fold—which resulted in heightened ecotoxicity to Daphnia magna. This aligns with findings from Grynkiewicz-Bylina et al.[13], who documented excessive PAH concentrations and detectable levels of Pb, Cd, and Hg in sport field granulate, reinforcing concerns about both human exposure and environmental contamination. These studies highlight that while human health risks from direct contact with rubber granulate under typical use conditions appear limited, the environmental impacts—particularly under conditions of UV exposure and weathering—are substantial. The presence of persistent toxic substances warrants both precautionary regulation and the exploration of safer alternative materials, especially for widespread applications such as playgrounds and sports fields.

Freely dissolved (Cfree) PAHs content

-

To assess the environmental risk of the analyzed samples, the concentration of freely dissolved PAHs (Cfree) was determined (Fig. 1a). Over the past decade, several studies have shown that Cfree represents the bioavailable fraction of hydrophobic organic contaminants (HOCs)—that is, the portion available for biological uptake[26−28]. Additionally, Cfree allows for the estimation of potential contaminant leaching (i.e., the strength of PAH binding to the matrix, represented by the Kd coefficient) into the environment.

In rubber granulate, Cfree concentrations ranged from 445.4 to 542.5 ng/L. Similar to the Ctot PAH content, the highest Cfree values were observed in granulate with the smallest particle size, and Cfree decreased as particle size increased. Notably, Cfree PAH concentrations did not vary proportionally with Ctot PAH concentrations, indicating different affinities of the various granulate fractions for the target compounds.

To date, no studies have examined Cfree PAHs concentrations in rubber granulate; existing data pertain to other environmental and anthropogenic matrices, such as soils[26], sediments[29], biochars and nano-biochars[16,30], sewage sludge[31,32], and biogas plant residues[33]. However, to provide context, these results can be compared with Cfree PAH levels reported for various environmental matrices. For example, Arp et al.[26] found that in historically contaminated soils from Sweden, France, and Belgium, Cfree levels ranged from 0.02 to 460 µg/L, largely depending on Ctot PAH content. Sediments from uncontaminated sites typically contain 0.08 to 342 µg/L Cfree PAHs, while highly contaminated sediments can contain 0.1 to as high as 10,867 µg/L[29]. Previous research on sewage sludge[31,32] and biogas plant residues[33] showed that Cfree concentrations in sewage sludge range from 13.2 to 59.2 ng/L, and from 262.1 to 293.5 ng/L in biogas residues. The lowest Cfree PAHs content is typically found in biochars (< 126.4 ng/L), although Cfree PAHs content in this material depends on the feedstock used to produce the biochar[16, 34]. The Cfree concentrations observed in this study for rubber granulate (> 445.43 ng/L) are high compared to other environmental matrices, notably exceeding those in uncontaminated soils and sediments.

The distribution of PAH groups within the Cfree fraction (Fig. 1c) differed significantly from that in the Ctot PAH content (Fig. 1b), reflecting the compounds' affinities for water. Regardless of granulate size, 3-ring PAHs dominated the Cfree fraction (49%–63%), followed by 4-ring PAHs (25%–46%). The 2-ring PAHs, represented by naphthalene, accounted for 4%–12% (Supplementary Table S1). The contributions of 5- and 6-ring compounds did not exceed 0.08% and were less than 0.03%, respectively. These results suggest that heavier PAHs bind more strongly to the granulate, while 2- to 4-ring PAHs are the most likely to leach from the material. Comparing these findings with previous studies on other environmental matrices[26,29,31,32], it is clear that, regardless of the matrix—whether sediments, sewage sludge, historically contaminated soils, or rubber granulate—the dominant PAHs among the 16 priority compounds are phenanthrene, pyrene, and fluoranthene.

Values of log Kd for investigated granulate

-

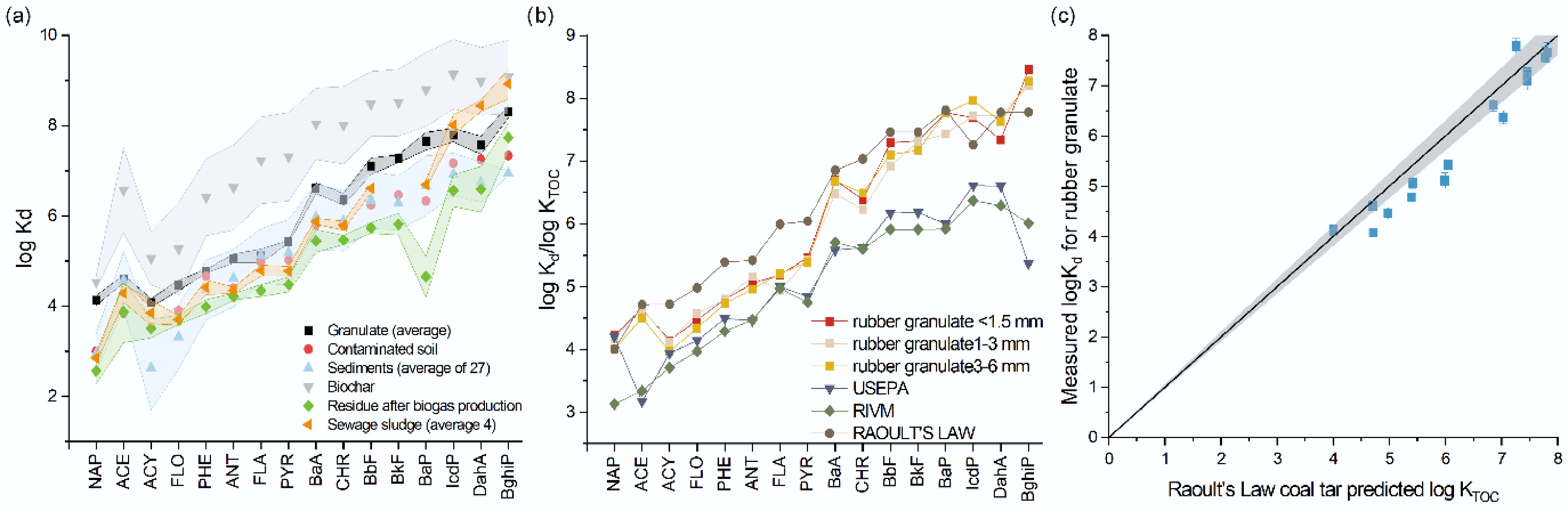

Supplementary Table S1 shows the calculated partition coefficients (Kd) for the tested materials. The highest log Kd values for most PAHs were found in the granulate with the smallest particle size, confirming previous findings that the finest granulate has the strongest affinity for the studied compounds. Comparing the obtained log Kd values to those reported for other environmental matrices and anthropogenic adsorbents (such as biochar, activated carbon, and sewage sludge) (Fig. 2a), it is clear that the tested material has a high affinity for PAHs. The log Kd values for the granulate exceeded those reported for historically contaminated soils by an order of magnitude[26] and were three orders of magnitude higher than those for sediments[29, 35]. Activated carbon was the only material that exhibited log Kd values between one and four orders of magnitude higher than those observed for the granulate[35] (Fig. 2a). To evaluate environmental risk, the Kd values obtained in this study were compared with guideline-recommended partitioning constants (USEPA, RIVM, coal tar KTOC) (Fig. 2b). As shown in Fig. 2b, the Kd values for PAHs in the rubber granulate measured here are significantly higher than those recommended by USEPA[36] and RIVM[37], but they closely match coal tar KTOC values. Therefore, the risk associated with the granulate is lower than that posed by contaminated soils or sewage sludge introduced into soils. However, due to the level of PAH contamination in the granulate, there remains a tangible risk to organisms, especially considering the aging of the granulate under environmental conditions. Figure 2c compares measured log Kd values for all PAHs in this study with the Raoult's Law coal tar model[38,39]. The coal tar model is a method used to understand and predict the behavior of coal tar—a complex, multi-component, non-aqueous phase liquid (NAPL)[38]. The model is significant for assessing groundwater contamination and human health risks at sites historically contaminated with coal tar, such as former manufactured gas plants[40]. As shown in Fig. 2c, the Kd values calculated for rubber granulate in this study align well with the predictions from the coal tar model. This strong agreement is primarily due to the high content of pyrogenic residues present in the rubber materials.

Figure 2.

(a) Distribution coefficients (log Kd) of selected PAHs in various materials. Shaded areas represent standard errors of the mean (n = 3). (b) Comparison of normalized sorption coefficients (log Kd/log KTOC) of selected PAHs for rubber granulate fractions (< 1.5, 1–3, and 3–6 mm) with standard partitioning models (USEPA, RIVM, Raoult's Law). (c) Correlation between measured log Kd values for rubber granulate and log KTOC values predicted using Raoult's Law for coal tar. Shaded area represents 5% confidence area.

Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) content and toxicity of leachates

-

Table 2 presents the concentrations of PTEs in leachates obtained from granulate samples. The PTEs content in the leachates decreased as the granulate particle size increased. Notably, the differences in concentrations of individual PTEs between the smallest granulate fraction and the 1–3 and 3–6 mm fractions were several-fold, reaching even an order of magnitude (Table 2). Zn exhibited the highest concentration in the leachates, ranging from 13 to 103 mg/L, followed by Cu (0.006 to 27.5 mg/L) and Cr, detected primarily in the smallest fraction at 1.5 mg/L. Ni, Cd, and Pb concentrations were below 0.08 mg/L. This trend suggests that finer fractions have a greater surface area-to-volume ratio, which enhances the leaching potential of metals such as Zn, Cu, and Cr. Similar observations were reported by other researchers[41,42], who found that smaller particle sizes of waste-derived materials leached significantly higher concentrations of metals due to increased surface reactivity and permeability. Elevated Zn and Cu levels are consistent with previous studies on industrial waste and recycled aggregates[41], in which Zn was frequently identified as the most mobile and bioavailable PTE due to its high water solubility and weak retention by mineral matrices.

Table 2. Potentially toxic elements concentration in studied granulate rubber

Element Concentration (mg/L) < 1.5 mm 1–3 mm 3–6 mm Zn 103.447 ± 0.8 18.119 ± 0.1 13.078 ± 0.1 Cu 27.573 ± 0.2 0.009 ± 0.000 0.006 ± 0.0 Cr 1.459 ± 0.3 nd nd Ni 0.080 ± 0.0 0.005 ± 0.0 0.004 ± 0.0 Cd 0.048 ± 0.0 nd nd Pb 0.02 ± 0.0 0.02 ± 0.0 nd Co 0.380 ± 0.0 0.079 ± 0.0 0.073 ± 0.0 For all PTEs regulated by legal standards, the concentrations exceeded drinking water limits several times, according to both European[43] and US EPA[44] regulations. Regardless of particle size, contact between the granulate and water results in the release of PTEs at levels hazardous to human health and aquatic organisms. This observation is supported by ecotoxicological test results.

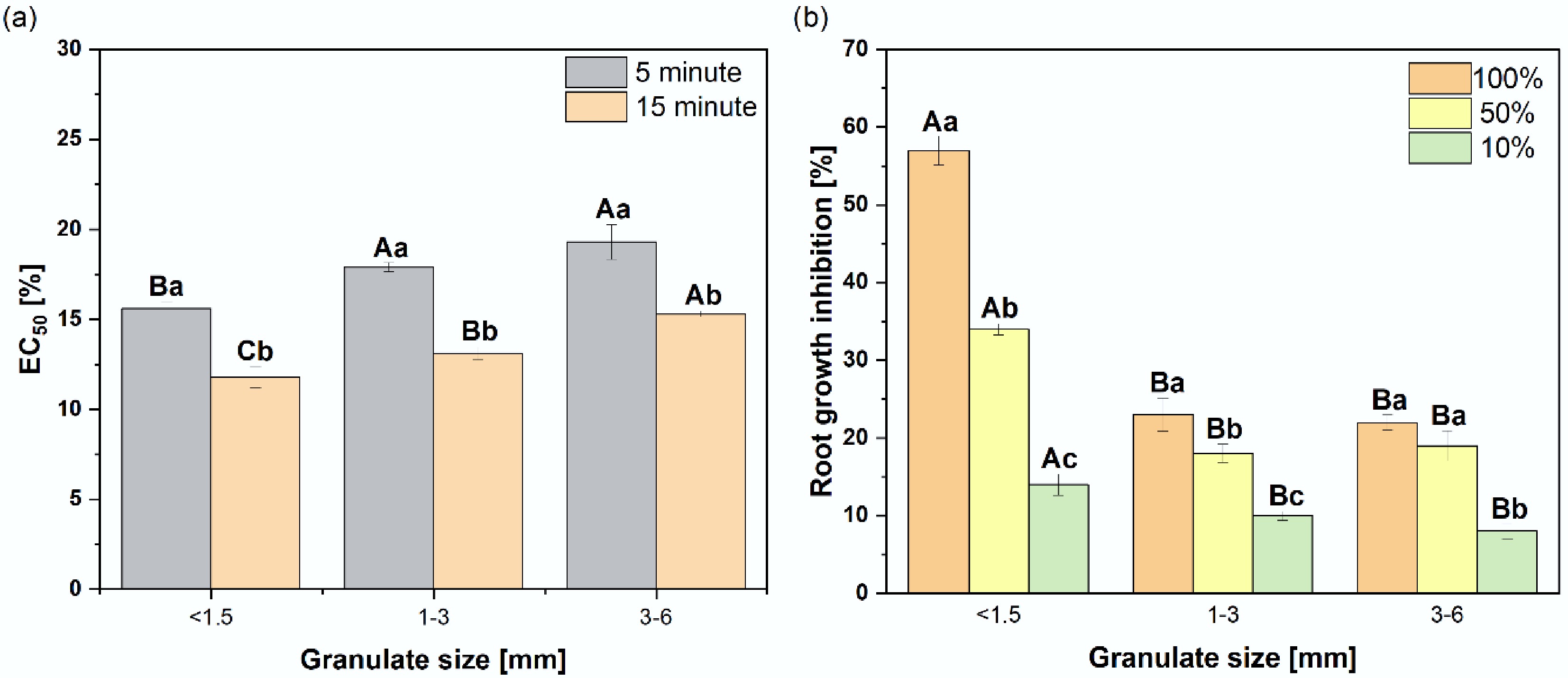

Figure 3 shows the calculated EC50 values for the obtained extracts relative to Aliivibrio fischeri and Supplementary Table S2 for Lepidium sativum. The leachates were more toxic to bacteria than to plants. Untreated aqueous extracts from the granulate caused complete inhibition (100%) of bacterial luminescence (Supplementary Table S3). Plants demonstrated notably higher tolerance to the leachates, with raw leachates inhibiting root growth by 22% to 57% (Fig. 3b). It is important to emphasize that the calculated EC50 values for both bacteria and plants (Supplementary Tables S2 & S3) were well correlated with granulate size, and consequently with the PTEs (Supplementary Figs S1 & S2) and PAHs content (Fig. 4), suggesting the critical role of these contaminants in the observed toxicity. Furthermore, increasing the exposure time of A. fischeri to the leachates from 5 to 15 min decreased the toxic effect (Fig 3a). This effect is likely due to organic contaminants because PTEs need time to fully interact with the target organisms. Figure 3b also illustrates the toxicity of the leachates toward L. sativum. Consistently, the finest granulate fraction exhibited the highest toxicity (root growth inhibition = 55.8%). Extracts from the 1–3 mm and 3–6 mm fractions showed relative growth inhibition (RGI) values of –5.4% and 7.5%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Ecotoxicity of leachates from rubber granulate of different size fractions. EC50 values for Aliivibrio fischeri after 5 and 15 min of (a) exposure and (b) root growth inhibition of Lepidium sativum exposed to three leachate concentrations (100%, 50%, 10%). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). Capital letters indicate significant differences among particle sizes for a given exposure time or extract concentration, whereas lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different exposure times or concentrations within the same particle size (p ≤ 0.05).

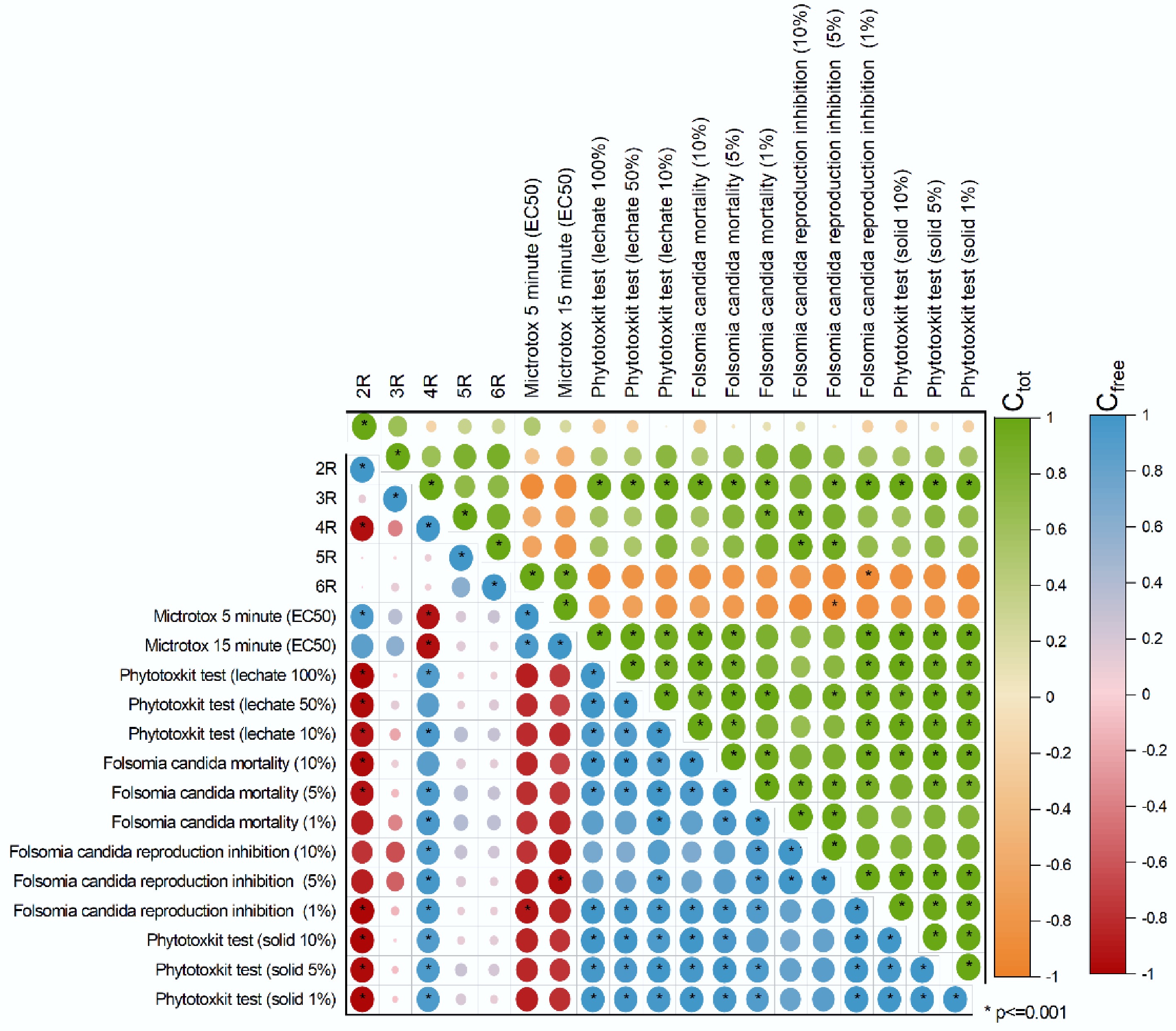

Figure 4.

Correlation matrix between Ctot (top green–orange panel) and Cfree (bottom blue–red panel) PAH concentrations, grouped by number of aromatic rings, and endpoints of ecotoxicity tests. Ecotoxicological responses include Microtox (EC50), Phytotoxkit (root growth inhibition of Lepidium sativum), and Folsomia candida mortality and reproduction inhibition for both leachate and solid-phase tests. Significant correlations (p ≤ 0.001) are marked with *.

Evaluation of leachates toxicity from complex environmental matrices such as rubber granulate is most effectively achieved through risk analysis based on the presence of numerous contaminants using biological assays. Due to the limited knowledge about the chemical composition of waste tire leachate, the optimal approach for toxicity evaluation is not to assess individual factors but rather to consider all potential contributors to the toxicity of the granulate under study. Therefore, in this work, a portion of the ecotoxicological tests was conducted on aqueous extracts containing all water-leachable contaminants (both organic and inorganic). Previous studies on rubber waste[45,46] and whole tires[47] showed that the toxicity of these materials toward the bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri is comparable (luminescence inhibition ranging from 40% to 92%) to that observed in the granulate tested here. The findings confirm that contaminants present in leachate from rubber granulate may pose a moderate risk to aquatic organisms, particularly when concentrated. Moreover, the reduced toxicity observed in extracts from granulate with larger particle sizes may also be influenced by the pH of the extracts. Higher pH values limit Zn leaching[48] from the granulate, thereby reducing the toxicity of the extract. This is supported by the results obtained in this study (Tables 1 & 2), where significantly lower Zn concentrations were observed in granulate characterized by higher pH values (granulate with particle diameters of 1–3 and 3–6 mm), contributing to their decreased toxicity. Additionally, toxic activity is expected to diminish rapidly due to natural processes, such as the transformation of toxic compounds into non-toxic products through interactions with salt ions present in water, as previously reported[46].

Results confirm that both chemical contamination and toxicity are strongly dependent on the physical characteristics of the material, particularly particle size. The finer fractions pose a disproportionate environmental hazard, emphasizing the need for size-specific assessment and regulatory control of such materials before their use in environmental applications.

Toxicity of solid phase

-

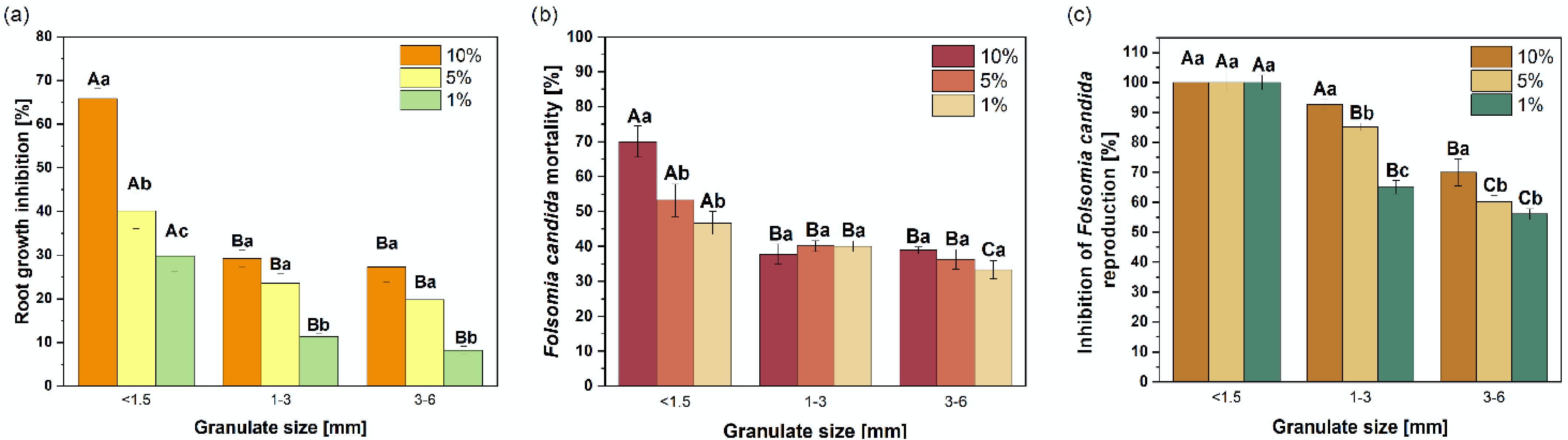

Similar to the extract tests, a clear relationship was observed between the toxic effect and the size of the granulate. All granulate fractions inhibited the growth of L. sativum in the solid phase test (Fig. 5a). The highest toxicity was exhibited by the finest granulate, followed by the medium and the largest fractions. No significant (p > 0.05) differences in root growth inhibition were found between the 1–3 and 3–6 mm granulate. Depending on the dose, root growth inhibition of L. sativum ranged from 29.8% to 65.9% (< 1.5 mm), 11.4% to 29.2% (1–3 mm), and 8.2% to 27.2% (3–6 mm). For each dose, the toxic effect of the finest granulate was more than twice as high as that observed for the other two granulate sizes.

Figure 5.

Ecotoxicity of the solid phase of rubber granulate with different size fractions. Root growth inhibition of (a) Lepidium sativum, (b) mortality, and (c) reproduction inhibition of Folsomia candida in soils amended with rubber granulate at three amendment levels (1%, 5%, 10%). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). Capital letters indicate significant differences among different particle sizes for a concentration, whereas lowercase letters indicate significant differences between different concentrations within the same particle size (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5b, c shows the impact of the granulate on mortality and reproduction of Folsomia candida, respectively. Similar to the L. sativum assay, this effect was strongly dependent on granulate size. The highest mortality rates were observed following exposure to the finest granulate fraction (46.7% to 70%) (Fig. 5b). Notably, an increase in mortality with increasing granulate concentration in OECD soil was observed only for this fraction. Larger granulate size also caused significant mortality of F. candida (33.3% to 38.9%), but no dose-dependent mortality relationship was detected in these cases.

The detrimental effects of all tested granulate were more pronounced for F. candida reproduction (Fig. 5c). Consistent with mortality results, the finest granulate caused complete (100%) inhibition of reproduction. Granulate with larger particle sizes inhibited F. candida reproduction in a dose-dependent manner, with reductions ranging from 65% to 92.7% for the 1–3 mm fraction and from 56.1% to 70% for the 3–6 mm fraction. A significant dose-response relationship between granulate concentration and reproductive inhibition was confirmed for these fractions (Fig. 5c).

Root growth inhibition values obtained from the solid-phase test were higher than those from the equivalent liquid-phase test. This indicates that the toxicity of the investigated granulate, regardless of particle size, is associated with contaminants bound to the granulate that are not leached easily from the matrix. It has been shown[49] that organic compounds are most effectively leached at extreme pH values (2 and 11) and least at near-neutral pH. Therefore, despite the high Ctot PAH content in the granulate, the Cfree PAH fraction exhibits a low PAH level, resulting in a less toxic extract. Additionally, the small difference in toxic effects observed between the two tests for the finest fraction may be attributed to more efficient leaching of contaminants.

To date, this studies represents the first assessment of granulate toxicity toward F. candida. Previous research[50] demonstrated that F. candida tests are suitable for evaluating the toxicity of various waste materials. The rubber granulate tested exhibited higher toxicity than soils heavily contaminated with PAHs (2,634 mg/kg)[51]. Mortality and reproduction inhibition of F. candida reported by Eom et al.[51] ranged from 20% to 68% and 22% to 98%, respectively. Other matrices such as sewage sludge, dried pig slurries[52], and biogas residues[53] also showed lower toxicity to F. candida compared to the rubber granulate.

Literature indicates that juvenile F. candida prefer substrates with a high C/N molar ratio[54], which aligns with the findings showing approximately 4-fold higher C/N ratios in granulate with larger particle sizes (fractions 1–3 and 3–6 mm) relative to the finest fraction (< 1.5 mm) (Table 1). Studies by Droge et al.[55] identified a specific adverse effect of pyrene on the reproduction of F. candida in soil. These results support this observation, as evidenced by the high pyrene content (up to 45 mg/kg in the granulate) and the strong to complete inhibition of springtail reproduction. Similar effects were observed in studies on sexually reproducing F. fimetaria[56], indicating that pyrene's impact on reproduction is independent of reproductive mode. The negative effect on reproduction may be caused not solely by pyrene itself but also by its toxic metabolites such as 1-hydroxypyrene[57]. Higher pyrene concentrations correlate with increased levels of metabolic products, including 1-hydroxypyrene, which adversely affect reproductive capacity. The toxicity observed in this study, alongside PAHs present in the granulate, may also stem from other toxic compounds such as zinc and its oxide[12], benzothiazole and its derivatives, plasticizers (e.g., phthalates), and antioxidants[6, 58], which are commonly found in rubber waste and whose toxic effects have been repeatedly documented[59].

-

This study provides a comprehensive, integrated assessment of recycled tire rubber granulate across particle sizes, combining chemical measurements (Ctot and Cfree PAHs content) with solid- and liquid-phase bioassays. Particle size emerged as a decisive driver of hazard. The smallest fraction (< 1.5 mm) contained the highest levels of total and freely dissolved PAHs and elevated PTEs (notably Zn), which translated into the strongest adverse effects on soil invertebrates, plants, and aquatic microorganisms. Larger fractions showed lower contaminant levels and reduced biological impact, underscoring the role of surface area in contaminant release and bioavailability.

These results demonstrate that rubber granulate is not only a reservoir of PAHs but an active source of bioavailable contaminants, and that concentration data alone are insufficient for risk evaluation without ecotoxicological context. Given the widespread use of tire-derived granulates in public spaces (e.g., playgrounds and sports fields), fine particle fractions present a disproportionate environmental and potential health risk. The findings support the need for stricter, size-aware regulatory oversight and the development of safer alternative materials to mitigate long-term ecological and public health impacts. Future research should also address the release of other contaminants beyond PAHs and metals, and include advanced toxicological endpoints such as mutagenicity or chronic exposure assays, to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of risks associated with rubber granulate.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/ebp-0025-0016.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Monika Raczkiewicz: study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis, preparation of the first draft; Agnieszka Tkacz: study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis, preparation of the first draft; Jarosław Madej: study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis; Patryk Oleszczuk:study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis, draft editing. All authors reviewed the data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

-

All authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

-

Recycled rubber granulate contains high PAH levels, with smaller particles showing the highest total and bioavailable fractions.

Granulate toxicity affects invertebrates, plants, and microorganisms, decreasing with increasing particle size.

Fine particles pose disproportionate environmental and potential health risks, especially in playgrounds and sports fields.

Findings highlight the need for size-aware regulations and safer alternatives for tire-derived granulate.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Raczkiewicz M, Tkacz A, Madej J, Oleszczuk P. 2025. Toxicity and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons bioavailability in recycled tire rubber granulate of varying particle sizes. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e016 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0016

Toxicity and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons bioavailability in recycled tire rubber granulate of varying particle sizes

- Received: 04 August 2025

- Revised: 31 October 2025

- Accepted: 05 December 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: This study aimed to determine the total (Ctot) and bioavailable (freely dissolved, Cfree) concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as well as the toxicity of rubber granulate (three particle size fractions: < 1.5, 1–3, and 3–6 mm) derived from recycled used car tires. Ecotoxicological analysis was conducted using both solid-phase and liquid-phase (leachate) tests. The solid-phase tests included the Collembolan Test (using Folsomia candida) and the Phytotoxkit F Test (using Lepidium sativum), while the liquid-phase tests involved Microtox® (using Aliivibrio fischeri) and the Phytotestkit F Test (using Lepidium sativum). The rubber granulate contained very high PAH levels, ranging from 49 to 108 mg/kg, depending on the granulate particle size. The Cfree fraction ranged from 445 to 543 ng/L. PAH content decreased as the granulate particle size increased. Phenanthrene, fluoranthene, and pyrene dominated in all granulate fractions, representing 10.8%–16.0%, 10.3%–14.1%, and 29.5%–42.1% of the total PAHs, respectively. The rubber granulate was toxic to all tested organisms. Larger granulate particles caused a reduction in toxic effects on the organisms studied. These findings suggest that using rubber granulate in the environment, especially in public areas such as playgrounds, sports fields, and running tracks, may lead to the release of toxic organic compounds into soil and surface waters. Prolonged exposure could disrupt soil ecosystem functions and pose potential health risks, particularly for children who come into direct contact with the granulate. The results highlight the need for cautious use of tire-derived granulate and the development of guidelines to ensure its safe application.