-

Rice is one of the most important economic and ecological crops, supporting food production while having a well-reported impact on environmental conditions. Like other crops, rice underwent a major domestication over the last thousand years. Domestication of wild plants for agricultural purposes is one of the most fundamental processes shaping the history of human civilization[1]. This domestication process, and subsequent genotype evolution, largely alter rice traits, exerting multiple unintended effects on the way in which crop plants interact with microbes and ultimately on plant health and soil functioning[2−6]. Strikingly, while the impact of domestication on rice traits and functioning is well-documented, much less is known about the overall contribution of rice genotype diversity to supporting microbial diversity and function in both modern crops and their wild progenitors[7−9]. It is still not clear how, and to what extent, to which plant-microbe interactions and environmental filtering of microbial communities were affected by crop domestication and evolution under cultivation. Indeed, this ambiguity is reflected in literature, which is replete with idiosyncratic findings. While numerous studies have indicated a decrease in microbial diversity with domestication[10,11], others have reported no discernible impact or an increased diversity[12−14].

It is proposed that this inconsistency stems from conceptualizing domestication as a simple binary, a view that obscures the often more powerful effects of intraspecific genetic variation within both wild and cultivated populations. This oversight is a key reason why there is a lack of studies considering multiple genotypes of cultivars and wild progenitors simultaneously. Previous studies have demonstrated that intraspecific host genetic identity regulates the microbial community assembly in plants[15,16]. Diverse genotypes of the same crop species could exhibit wide variations in morphological and chemical traits and recruit distinct plant-associated microbiomes, thereby significantly contributing to crop adaptation to climate change and environmental stresses and fostering agricultural productivity[4,17,18]. Different crop genotypes can also have various specific effects on plant-soil interactions and soil processes, such as the stabilization of rhizodeposition-derived C and soil organic matter mineralization[19]. Additionally, community genetics posits that intraspecific genetic variation can scale up processes from the individual to the ecosystem level[20]. Hence, studies using multiple genotypes and wild species are required to better understand the role of host plant genotypes and domestication status in shaping the plant-associated microbiomes and their functions. Beyond the genetic drivers, microbiomes are diverse and have been found to vary across distinct plant compartments[21]. However, unlike the rhizosphere, little is known about the influence of domestication on the phyllosphere microbiome and elemental composition of leaf tissue, which is a key compartment responsible for plant health and ecosystem functions, such as plant productivity and crop residue decomposition[22,23]. Advancing our knowledge of the contributions of crop genotypes is the first step in explaining the effects of domestication on the microbial diversity and functions in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere, two key plant compartments for sustainable agriculture[24,25]. This knowledge is critical to better understanding how future crop genotypes can promote key ecosystem services such as food security, carbon sequestration, and soil fertility.

Additionally, crop domestication and cultivation have always been accompanied by resource inputs altered by management practices compared with the natural ecosystems where wild progenitors thrive[26]. Although nitrogen is an essential nutrient for plant growth and productivity, its excessive use as a fertilizer can lead to soil degradation and environmental deterioration[27,28]. Previous studies using different crop varieties have revealed the crucial role of genetic variants in facilitating the adaptation to specific local environments, particularly by causing the variation in the nitrogen-use efficiency of crop plants[29,30]. Nevertheless, a significant reduction in alleles conferring advantageous traits related to nitrogen-use efficiency has been observed in modern cultivars compared to their wild progenitors due to high nitrogen inputs during crop cultivation[29,31]. Thus, advancing our understanding of the effects of nitrogen fertilization, genotype identity, domestication status, and their interactions in plant and soil compartments with the microbiome and its functions are vital for harnessing genetic diversity to develop strategies for sustainable crop production.

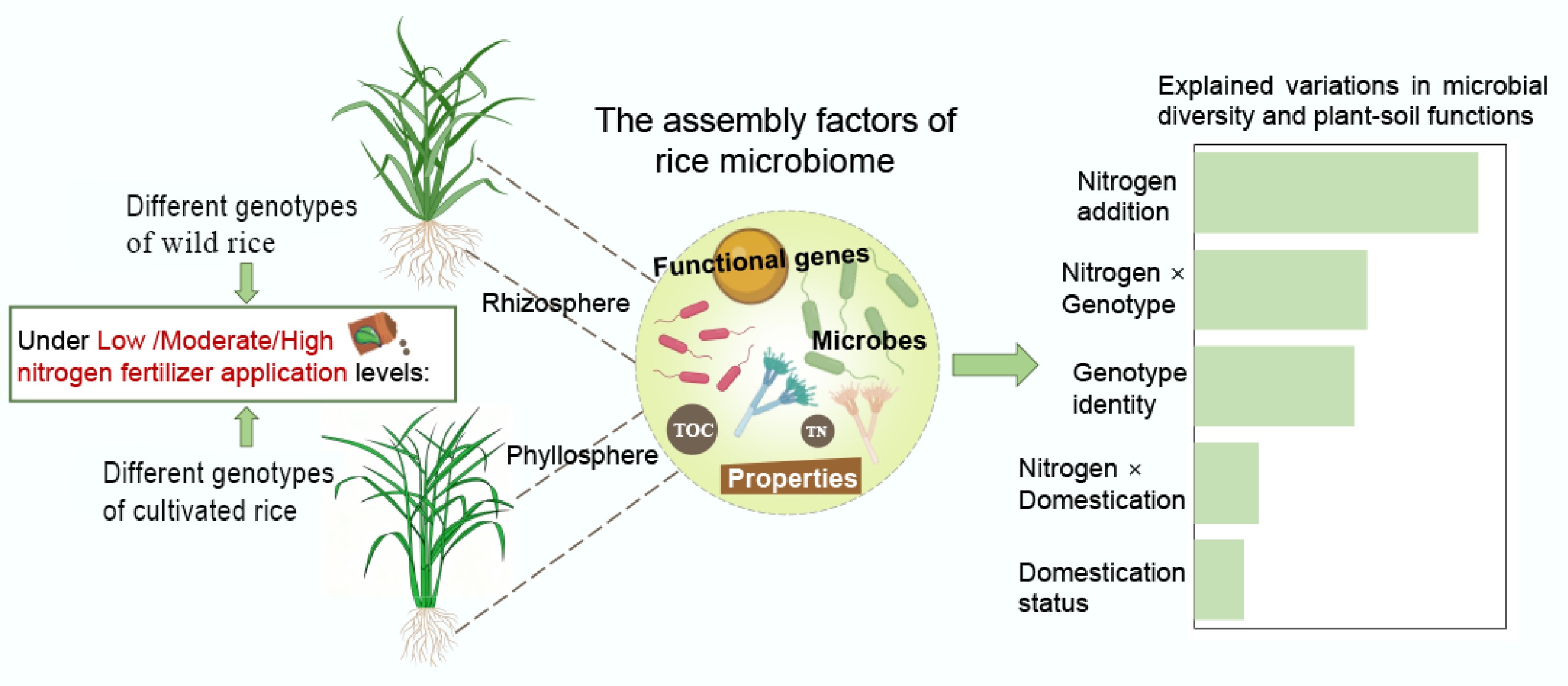

Here, rice (Oryza sativa L.) was used as the model plant as it is one of the top five food crops produced worldwide, and plays a vital role in the global food supply[32]. A glasshouse experiment was conducted using three different genotypes of domesticated rice and four different genotypes of its wild progenitors to investigate the roles of domestication and genotype identity in driving microbial diversity and biogeochemical cycling in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere, as well as in host plant chemistry and soil properties and functions under contrasting levels of nitrogen fertilization. The following questions were addressed: (1) Which factors primarily drive the variation in microbial communities and functions in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of cultivated rice varieties and their wild progenitors? (2) How do the interactions among nitrogen fertilization levels, the identity of rice genotypes, and domestication status affect the microbiome and its functions in plant and soil compartments?

-

A pot experiment was carried out in a greenhouse at Jiaxing Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Zhejiang Province, China (30°50' N, 120°42' E). The soils used in the experiment were collected from a relatively oligotrophic field in Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province, China, which had not been cultivated or treated with fertilizers for 20 years (Supplementary Table S1). Soils were air dried and sieved through a 2-mm mesh to remove impurities, and then thoroughly mixed and stored at room temperature before planting the rice. As plant materials, genotypes of cultivated Asian rice and its wild progenitor were used. The two major varietal groups in Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.), indica and japonica, arose from a common wild ancestor, Oryza rufipogon[33]. Hence, based on the geographic provenances, four varieties of common wild rice (O. rufipogon) collected from the Natural Conservation Region for Wild Rice in Jiangxi (JXFZ and JXYD), Guangxi (GXLP), and Guangdong (GDYD) Provinces in China (Supplementary Table S2) were selected. Seeds of three domesticated rice varieties, which are representative of common cultivars of indica (IR24), japonica (Nipponbare, RBQ), and indica-japonica hybrid rice (YongYou1540, YY1540) grown in China, were obtained from the Jiaxing Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

A total of 100 pots for seven rice genotypes, and three nitrogen addition levels, with 3–7 replicates (pots) for each genotype-treatment combination, were laid out in a completely randomized design (Supplementary Fig. S1). Urea was used as the nitrogen source and applied as aqueous nitrogen solutions, with net nitrogen application rates of 0.005, 0.015, and 0.03 kg m−2 for low, moderate, and high nitrogen loading, respectively[29]. Nitrogen fertilizer was applied at the seedling stage. Each pot (top diameter of 16 cm, bottom diameter of 11 cm, and height of 16 cm) contained two seedlings and 2.5 kg of air-dried soil. All rice seeds were soaked in 70% alcohol for 5 min and washed three times with sterile deionized water for microbial disinfection. Then, the seeds were treated with 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for 10 min and rinsed thoroughly with sterilized water. The seeds were subsequently placed in Petri dishes containing the wet filter paper and allowed to germinate in the dark at 25 °C for 3 d. Finally, seedlings germinated from the seeds were transplanted into pots in the greenhouse (30°50' N, 120°42' E), and grown for three months under natural light conditions. Deionized water was added to pots, with water being kept at a constant level of about 4–5 cm above the soil surface in each pot during the experiment.

Plant and soil sampling

-

After three months of growth, the tiller number of plants was measured manually. Soil and rice samples were collected at the flowering stage in July 2022. To obtain the rhizosphere soil samples, the soil remaining tightly bound to the root surface was scraped off with a small brush after the loose root-adhering soil was removed by shaking[34]. To obtain phyllosphere soil samples, 5–6 leaves were cut from around the stem in each pot. Leaves were selected from the middle and upper parts of the plant, which showed no visible signs of diseases, damage by insect pests, or senescence. All plant and soil samples were stored on dry ice and immediately transported to the laboratory. After measuring the fresh above-ground plant biomass, half of the leaf samples were oven-dried at 70 °C for 48 h and then stored at 4 °C for chemical analysis, and the other half (fresh samples) were stored at –20 °C for the analysis of phyllosphere microbes. Soils were further divided into subsamples, which were air-dried, sieved through a 2-mm mesh, and homogenized, and then, half of the subsamples were stored at 4 °C for physicochemical analysis, while the remaining ones were stored at –80 °C for DNA extraction.

Soil properties and elemental composition of rice leaves

-

Soil pH was measured using a glass electrode pH meter at a soil/water ratio of 1:2.5. Soil NO3−-N was extracted with 2 M potassium chloride (KCl) in a soil/KCl solution ratio of 1:5 on a rotary shaker for 60 min, and then determined using a continuous flow analyzer (Skalar, Breda, Netherlands). Total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (TN) were determined with a Shimadzu total organic carbon analyzer (TOC-VCPH) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The concentrations of aluminum (Al), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn), sodium (Na), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and phosphorus (P) in soils and leaves were measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES; Optima 8300, PerkinElmer, USA) and mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Agilent 7500, Agilent Technology, USA)[35].

Microbial taxonomic diversity in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of rice

-

Soil genomic DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of the rhizosphere soil samples using a FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedical, Santa Ana, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. The microbial DNA from the phyllosphere samples was extracted by the washing method[11]. Thereafter, the leaves were weighed, and around 1 g of rice leaf tissue, cut into pieces with a sterile scissor, was placed into a 50-mL sterile centrifuge tube containing 30 mL of 0.01 M sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH = 7.4), and then mixed. The centrifuge tubes were sonicated in an ultrasonic cleaning bath (KQ-3200DE, Ultrasonic Instruments Co., Ltd, Kunshan, China), with a frequency of 40 kHz and an ultrasonic power of 150 W for 5 min, followed by shaking at 180 rpm at 30 °C for 2 h. The obtained mixture was initially filtered through a sterilized nylon gauze, followed by filtration through a 0.22-µm cellulose membrane and then subjected to DNA extraction using the FastDNA® Spin Kit. The quality and concentration of extracted DNA were determined using a Qubit™ dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, USA). The primer sets 515F/907R and ITS1F/ITS2R were used to amplify the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the fungal ITS region, respectively[36,37]. The Illumina Miseq2500 platform (Majorbio, Shanghai, China) was used to sequence the PCR products after they were purified and pooled. The detailed methods used for bioinformatic analysis and standard PCR conditions were those previously reported[11]. The taxonomic identity and relative abundance of bacterial and fungal amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were assigned using SILVA v138 and UNITE v8.0 databases[38,39], respectively.

Microbial functional diversity in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of rice

-

The functional genes involved in carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur (CNPS) biogeochemical cycling in bacterial communities in soil and phyllosphere samples were quantified using QMEC based on HT-qPCR[40]. QMEC is a developed qPCR-based chip, which was performed on the WaferGen SmartChip Real-time PCR platform (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), containing 71 bacterial CNPS gene primers, including 35 C-cycling genes, 22 N-cycling genes, nine P-cycling genes, five S-cycling genes, and one 16S rRNA gene primer (Supplementary Table S3). The relative abundance of detected genes was calculated as described by Zheng et al.[40]. The assignment of fungal taxa to functional guilds was based on the FungalTraits database[41].

Statistical analysis

-

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Development Core Team, 2021). Significant differences in means for all variables among nitrogen fertilization levels, identity of genotypes, and domestication status were tested by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) under 999 permutations based on Bray-Curtis distance using the R 'vegan' package. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), partial canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP), and PERMANOVA based on Bray-Curtis distance were performed with 999 permutations using the 'labdsv' and 'vegan' packages to assess the differences in microbial communities and quantify the contribution of the identity of genotypes, domestication status, nitrogen fertilization levels, and their interactions to microbial community variation[42]. Box plots were created using the 'reshape2' and 'ggplot2' packages in R software 4.2.3. Bar charts were created using Origin 2022. Heatmaps were plotted using the 'pheatmap' package in R 4.2.3.

-

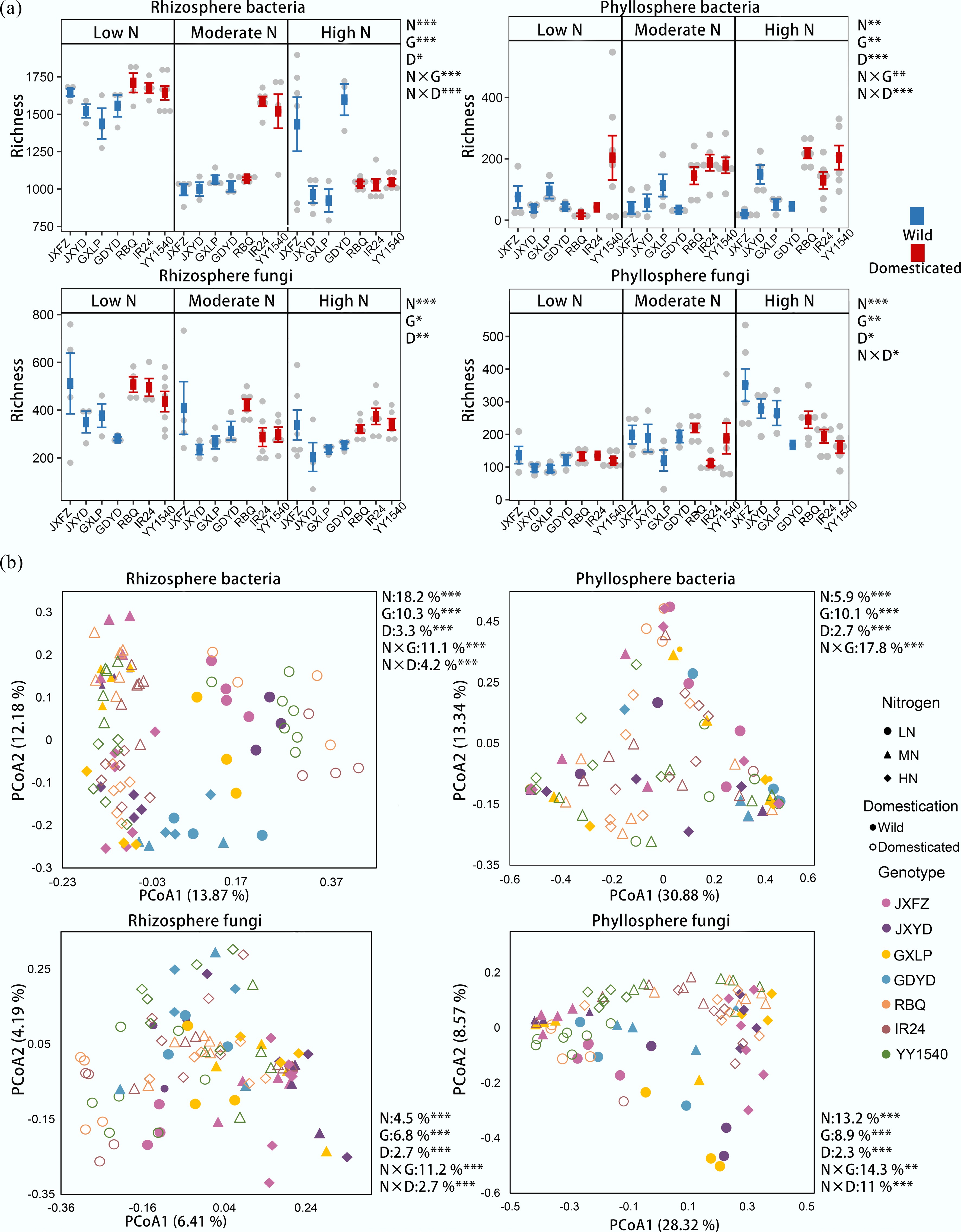

Nitrogen addition explained most of the variation in microbial alpha diversity of the rhizosphere (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S4). The identity of rice genotypes explained a larger proportion of variance in the richness of rhizosphere bacteria and fungi than did the domestication status (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Table S4). The significant interaction between nitrogen addition levels and the identity of rice genotypes also explained a larger percentage of variance (15.1%) in the richness of rhizosphere bacteria than did the interaction between nitrogen addition levels and domestication status (13.2%) (Supplementary Table S4). For rhizosphere bacteria, wild rice samples had lower richness than the domesticated ones under low and moderate nitrogen treatments. However, at the higher dose of nitrogen application, the richness of bacterial communities in domesticated rice decreased, while JXFZ and GDYD of wild rice exhibited higher richness than the domesticated rice varieties (Fig. 1a). The richness of rhizosphere fungi decreased with increasing nitrogen level. Most wild rice genotypes showed lower fungal richness than domesticated genotypes, but the opposite trend was observed for the genotype JXFZ. The significant interaction between nitrogen addition levels and the identity of rice genotypes explained a larger percentage of variance (14%) in the richness of phyllosphere bacteria than did the interaction between nitrogen addition levels and domestication status (8.3%) (Supplementary Table S4). Nitrogen addition explained most of the variation in phyllosphere fungal richness, followed by the identity of genotypes and domestication status. When considering microbial beta diversity, the effect of the rice genotype on bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere was stronger than that of the domestication status (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table S4). Nitrogen fertilization also explained most of the variation in the rhizosphere bacterial community. The interaction between nitrogen treatments and the identity of genotypes comprised the largest proportion of variation in each evaluated microbial community except for rhizosphere bacteria, whereas domestication status accounted for the lowest proportion of variation in each microbial community. Consistent with these findings, CAP analysis revealed significant separations among nitrogen treatments, domestication status, and identity of genotypes for both bacterial and fungal communities in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere (Supplementary Figs S3−S5).

Figure 1.

Comparison of microbial communities in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of different rice genotypes under three nitrogen fertilizer application levels. (a) Bacterial and fungal community richness. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). (b) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of bacterial and fungal community composition based on Bray-Curtis distances. The PERMANOVA results reveal the relative contributions of nitrogen addition (N), the identity of rice genotypes (G), and domestication status (D), as well as their interactions to bacterial and fungal richness and community composition. Significance levels of 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 are represented by *, **, and ***, respectively.

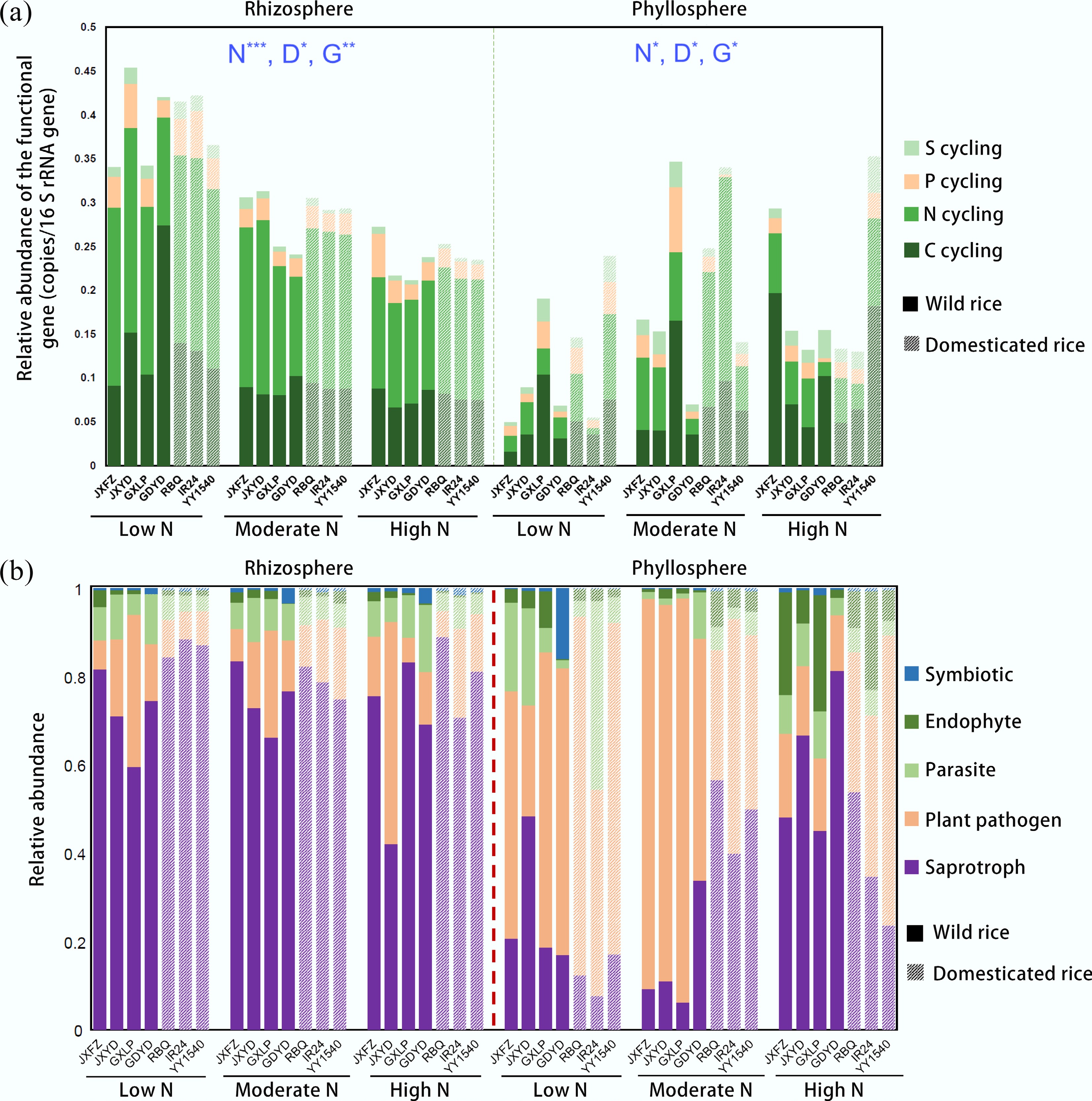

The abundance and diversity of the functional genes involved in C, N, P, and S cycling in bacterial communities of the rice rhizosphere and phyllosphere varied among domestication status, the identity of genotypes, and nitrogen treatments (Fig. 2; Supplementary Figs S6 & S7, Supplementary Table S5). With the increase in nitrogen addition level, the abundances of functional genes in bacterial communities of the rhizosphere of all genotypes decreased, while there was no consistent trend for phyllosphere bacterial communities (Fig. 2a). Nitrogen treatments were the dominant factor shaping bacterial functional gene composition in the rhizosphere (19.1%), whereas genotype identity explained most of the variation in the phyllosphere (6.7%) (Supplementary Table S5). In contrast, domestication contributed only a minor fraction of the explained variation in both compartments (2.4% and 2.1%, respectively). For N cycling genes, the rice genotype consistently explained a larger proportion of variance in both the rhizosphere and phyllosphere compared to domestication status (Supplementary Table S5). Furthermore, significant interactions between nitrogen addition and rice genotype profoundly influenced N and S cycling genes, particularly within the rhizosphere. These interactions led to genotype-specific variations in the relative abundances of key functional genes under different nitrogen addition levels (Supplementary Figs S6 & S7). Compared to moderate and high nitrogen levels, the rhizosphere had a greater abundance of saprotrophic fungi under the low nitrogen treatment (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. S8). The identity of genotypes explained most of the variation in endophytes, parasites, plant pathogens, and symbiotic fungi in the rhizosphere, while nitrogen addition explained most of the variation in phyllosphere endophytes and plant pathogens (Supplementary Table S6). The interactions among nitrogen addition levels, identity of genotypes, and domestication status also significantly influenced parasites, plant pathogens, saprotrophs, and symbiotic fungi in the phyllosphere. Intriguingly, in the phyllosphere of wild rice, moderate nitrogen treatment showed the highest abundance of fungal plant pathogens, followed by the low nitrogen treatment, while under the high nitrogen treatment, plant pathogens had their lowest abundance (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. S9).

Figure 2.

Shifts in functional genes and fungal traits in the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of different rice genotypes under three nitrogen fertilizer application levels. (a) Relative abundance of functional genes. (b) Relative abundance of fungal traits among the total identified traits. PERMANOVA analysis reveals significant differences in functional genes between nitrogen addition (N), the identity of rice genotypes (G), and domestication status (D); Significance levels are represented as follows: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; and *** p < 0.001.

Variation in rhizosphere soil properties

-

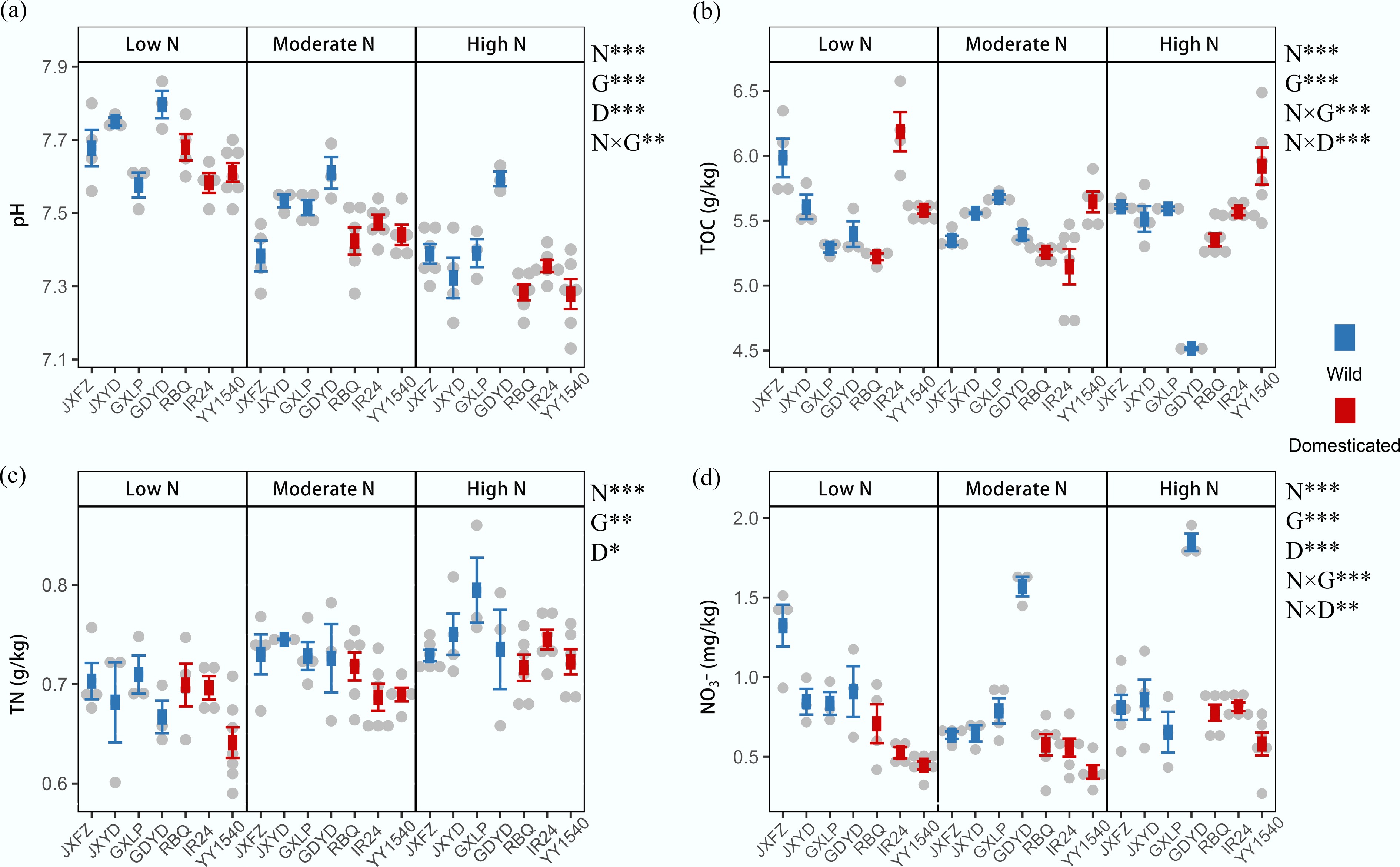

Nitrogen addition levels, identity of rice genotypes, and domestication status significantly affected different rhizosphere soil properties (Fig. 3). Nitrogen treatments explained the highest proportion of the variation in soil pH and TN (Supplementary Table S7). With the increase in nitrogen fertilizer level, the pH decreased, but TN increased. Domestication status also significantly influenced TN, with higher TN content generally observed in wild rice than in domesticated rice samples under the same nitrogen treatment. Notably, the identity of genotypes and the interaction between nitrogen addition levels and identity of genotypes exerted significantly strong influences on carbon sequestration compared to the domestication status alone, whose effect was statistically non-significant, totally accounting for 68% of the observed variation (Supplementary Table S7). The NO3– content was significantly affected by domestication status (R2 = 25.3%, p = 0.001), identity of genotypes (R2 = 22.2%, p = 0.001), and nitrogen addition (R2 = 5.5%, p = 0.001), and there were significant interactions between the three factors, with especially a highly significant interaction between nitrogen addition levels and identity of genotypes (R2 = 14.5%, p = 0.001). The NO3– content was higher in most wild rice samples than in domesticated rice under the same nitrogen treatment. In addition, genotype identity and its interaction with nitrogen addition levels explained the largest variance in the contents of aluminum, magnesium, manganese, sodium, zinc, iron, and phosphorus (Supplementary Fig. S10, Supplementary Table S7).

Figure 3.

Effects of nitrogen addition (N), domestication status (D), and identity of rice genotypes (G) on rhizosphere soil properties. (a) Soil pH. (b) Total organic carbon (TOC). (c) Total nitrogen (TN). (d) Nitrate nitrogen (NO3–-N). The data are presented as mean ± SD. PERMANOVA results indicate significant differences between treatment groups; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; and *** p < 0.001.

The variation in the functional traits of rice genotypes

-

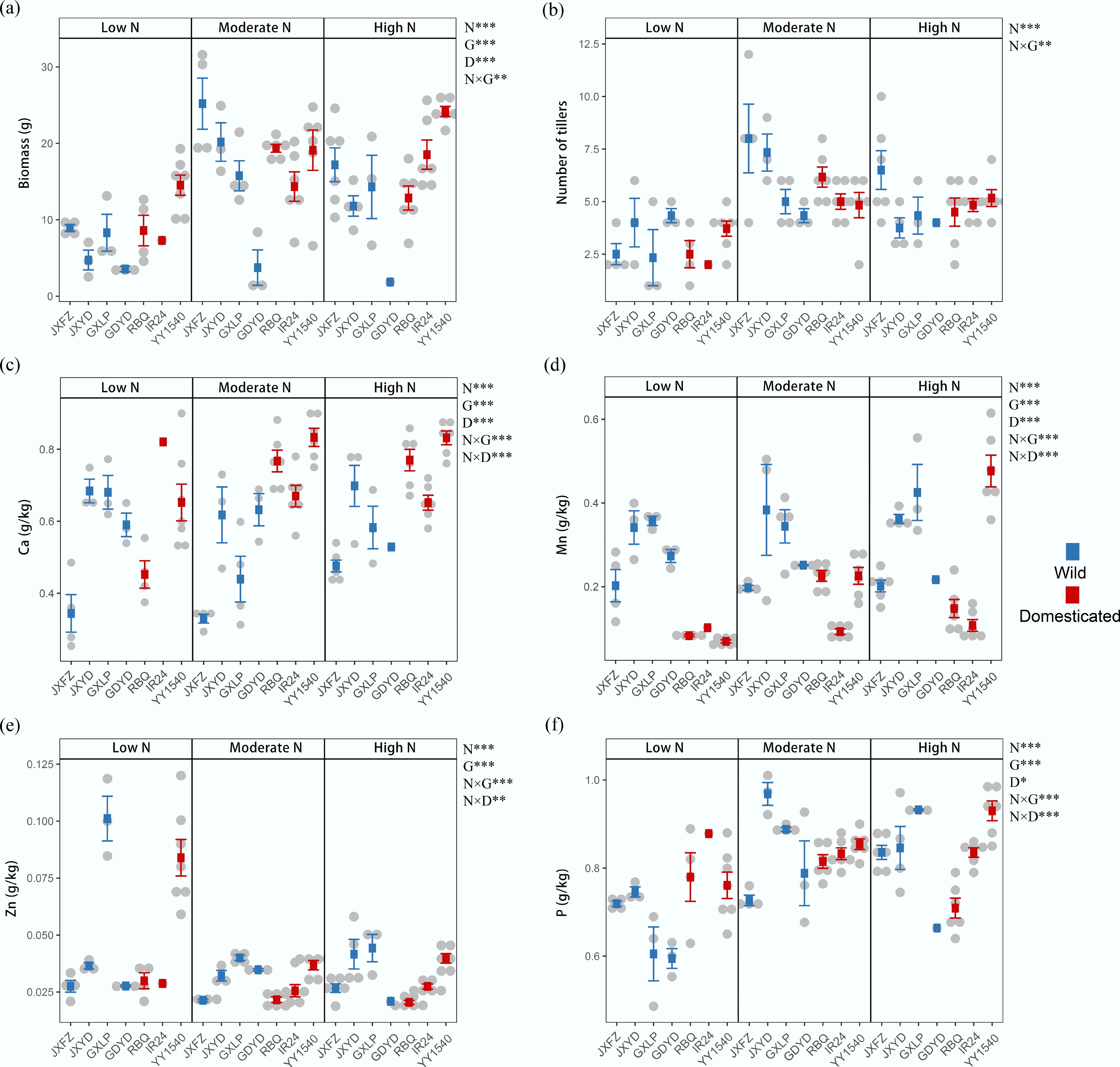

The fresh aboveground biomass and tiller number varied among different rice genotypes under different nitrogen treatments (Fig. 4). The identity of rice genotypes exerted the strongest significant effects on rice fresh biomass, explaining 29.8% of the variation, followed by nitrogen addition (R2 = 20.5%, p = 0.001) and domestication status (R2 = 7.3%, p = 0.001) (Supplementary Table S8). A significant interaction was also found between nitrogen addition and the identity of genotypes on rice biomass (R2 = 11.6%, p = 0.003) and tiller number (R2 = 17.5%, p = 0.006). For example, biomass and tiller numbers increased in different rice genotypes with increasing nitrogen addition, except for the genotype GDYD. The samples of genotype JXFZ under the moderate nitrogen treatment showed the highest biomass and tiller number compared to other genotype samples. Moreover, there were significant differences in concentrations of calcium, manganese, zinc, phosphorous, aluminum, magnesium, and sodium in rice leaves among different treatments, while iron was affected but not significantly (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. S11). PERMANOVA analysis showed that the identity of genotypes had the significantly greatest impacts on the concentrations of Ca, Mg, Mn, and Zn, explaining 29%, 32.3%, 28.5%, and 49.1% of the variation, respectively, whereas domestication status significantly affected the contents of Ca (R2 = 24.8%, p = 0.001), Mn (R2 = 24.6%, p = 0.001), and P (R2 = 1.5%, p = 0.041) (Supplementary Table S8). The interactions among nitrogen addition, identity of genotypes, and domestication status also explained large variations in the contents of Ca, Mn, Zn, and P.

Figure 4.

Effects of nitrogen addition (N), domestication status (D), and identity of rice genotypes (G) on rice functional traits. (a) Aboveground biomass. (b) Tiller number. Leaf concentrations of mineral elements: (c) calcium (Ca), (d) manganese (Mn), (e) zinc (Zn), and (f) phosphorus (P). Data are presented as mean ± SD. PERMANOVA results reveal significant differences between treatment groups; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; and *** p < 0.001.

-

The present results demonstrated a major role of the genotype identity of plant species in understanding the plant-soil microbiome and its functions. Several previous studies comparing plant rhizosphere microbial communities in modern cultivars and their wild ancestors have revealed the importance of domestication, while the effects of agricultural management, plant genotype, and their interactions with domestication status on microbial communities remain unexplored[10,13,43]. Moreover, plant rhizosphere and phyllosphere have unique structural and biochemical properties, but a clear picture of how domestication status and plant genotype influence the diversity and the functions of the plant-associated microbiome are lacking. The present study revealed that nitrogen addition significantly influenced the rhizosphere microbiome, while the identity of rice genotypes and their interaction with nitrogen addition could drive the microbiome and its functions in both the plant and soil compartments. In addition, the present results provide solid empirical evidence that genotype identity has a stronger influence on the structure and functions of the rhizosphere and phyllosphere microbiota than that found when comparing modern crops with their wild progenitors. Crucially, the present work broadens the perspective on crop improvement via plant breeding, while previous studies on domestication may have oversimplified the real effect of intraspecific trait variability in plants.

In this study, genotype identity emerged as a pivotal factor influencing the diversity and functions of plant-associated microbiomes. The plant-associated microbiota plays essential roles throughout the plant life cycle in modulating physiological processes, transmitting signals, providing essential nutrients, and promoting systemic resistance against pathogens and environmental stresses[44]. The present results revealed that different genotypes exhibited distinct rhizosphere and phyllosphere microbiomes, explaining significant variations in microbial diversity and functions in both of these two plant regions. After persistent directional selection, different provenances of the same plant species often exhibit remarkable dissimilarity and distinctive traits, thus recruiting specific plant-associated microorganisms[45]. The assembly of the plant microbial community is notably influenced by both plant morphology and chemical modification of the host-environment interface[46]. Plant genes control the external structures of roots and leaves, form the host-environment interface, and profoundly impact the plant microbial community[47]. Crucially, our findings extend this genotype-driven influence on specific functional groups, encompassing nitrogen and sulfur cycling genes, alongside potential plant pathogens. These findings suggest that intrinsic genetic factors not only dictate the overall microbial structure but also fine-tune specific microbial functions critical for nutrient cycling and host defense. Therefore, the present results underscore that plant microbial communities differed significantly among different genotypes of the same host species.

The present findings also emphasize that genotype identity consistently explained more variation in rhizosphere soil properties and plant functional traits than did domestication status. This indicates that while domestication is a critical evolutionary event, the vast spectrum of intraspecific genetic variation remains the more powerful driver of plant-soil ecosystem functions. For instance, an extremely stronger influence of the identity of rice genotypes on soil organic matter compared to that of the domestication status was observed. Although the rate of carbon sequestration was reported to diminish along a domestication gradient[48], the present results suggest that leveraging specific high-performing genotypes, rather than focusing solely on the domestication gradient, could be a more effective strategy for enhancing ecosystem services and mitigating climate change. This pattern extended from the soil to the plant itself. It is well-established that the chemical traits of a plant are indispensable to its evolution and fitness, as all species compete for essential elements for growth and development[49]. The present study provides a new layer of insight into this principle, demonstrating that the concentrations of key elements in rice leaves—including Ca, Mg, Mn, Zn, and P—were overwhelmingly dictated by genotype identity rather than domestication status. This finding is particularly significant for the phyllosphere, as it suggests that the host ionome acts as a key, genotype-dependent filter that governs the assembly and functional capacity of its microbial inhabitants. The substantial impact of genotype identity on rice microbiota, soil properties, and plant chemical traits observed in our study is ultimately rooted in the extensive genetic diversity within the Oryza genus. This diversity manifests as a wide array of root architectures, exudation profiles, and physiological characteristics, creating distinct ecological niches for microbial colonization[50]. Domestication, acting as a powerful selective filter for agronomic traits, has inevitably captured only a limited portion of the total genetic reservoir. This evolutionary trade-off has a direct statistical consequence. The present results consistently show that while domestication is a statistically significant driver, the vast underlying genetic diversity accounts for a much larger fraction of the total variance. Consequently, the largely untapped genetic reservoirs preserved in wild progenitors and landraces represent a critical resource for sustainable agriculture. Unlocking this rich genotypic diversity holds transformative potential for developing next generation crops capable of harnessing beneficial microbiomes to improve yield and soil health while reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers.

Furthermore, the present results showed that the nitrogen treatments had the most significant impact on the diversity and functions of rice rhizosphere bacteria and phyllosphere fungi, underscoring the sensitivity of plant-associated microorganisms to agricultural management practices. At a higher dose of nitrogen application, the richness and abundance of functional genes present in the rhizosphere microbiome were reduced in most of our evaluated rice genotypes, indicating the negative effects of excess nitrogen. The high dose of nitrogen application also exerted effects on biodiversity similar to those of long-term nitrogen fertilization, leading to biodiversity loss and subsequently compromising nitrogen cycling and soil multifunctionality[51,52]. However, wild rice genotypes exhibited no consistent patterns, e.g., a higher diversity under the high nitrogen treatment for certain genotypes was observed. These results highlight the greater sensitivity of microbial communities to nitrogen addition in rice cultivars than in their wild progenitors. This finding also implies the higher adaptability of wild rice to environmental fluctuations compared to domesticated rice, since plant domestication and cultivation often involve changes in habitat and agricultural management practices. This disparity underscores the vital need for understanding and integration of the adaptive traits of wild rice genotypes into agricultural practices. Furthermore, under different nitrogen treatments, distinct rice genotypes exhibited significant differences in the structure and functions of the rhizosphere and phyllosphere microbiome, as well as in plant functional traits and soil properties. The rice genotypes may adapt to different nitrogen levels through the regulation of gene expression. Previous research has demonstrated that host genetic variation can impact microbial communities in consistent ways across environments, playing a crucial role in determining disparities in the fitness among host genotypes[53]. Moreover, significant interactions among nitrogen fertilization, genotype identity, and domestication status, were found which profoundly influenced the microbiome and its functions in both plant and soil compartments. Notably, the interaction between nitrogen fertilization and rice genotype explained a larger variance in multiple aspects of soil and plant microbiomes and their functions than did that between the former and domestication status. Overall, the present findings suggest the potential for genotype selection tailored to specific environmental conditions, like soil fertility, bridging the realms of breeding and agronomy in agricultural practices. Such insights are indispensable for optimizing crop management strategies and ensuring sustainable agricultural production. It is also acknowledged that there are certain limitations in the present study. Firstly, the present glasshouse-based pot experiment, due to its controlled nature, may not fully replicate the intricate conditions of natural field ecosystems, particularly concerning soil structure, native microbial diversity, and environmental variability. Secondly, despite the present findings robustly highlighting the dominant role of genotype, the relatively limited number of rice genotypes examined may constrain the broad generalizability of these conclusions. Consequently, future research is crucial to validate these key findings under diverse field conditions and across a wider range of genotypes, thereby solidifying our understanding of plant-microbe interactions in agricultural settings.

-

The present study emphasizes the significant impact of genotypic variation on the structure and functions of the rhizosphere and phyllosphere microbiomes, soil properties, and plant functional traits, which was more pronounced than that of domestication status. It was also found that the effects of nitrogen fertilization on plant-associated microbiomes and their traits are highly dependent on genotype identity. Different genotypes exhibit different functions, opening up a potential avenue for breeding, which can use phytogenetic resources from both cultivars and their wild progenitors to promote ecosystem services. This knowledge is critical for optimizing crop management strategies, selecting future crop genotypes, and harnessing plant-associated microbiomes to promote key ecosystem services such as food security and soil fertility.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/aee-0025-0013.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Yue Yin: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing−original draft. Manuel Delgado-Baquerizo: conceptualization, writing−review and editing. Pablo García-Palacios: writing−review and editing. Hong-Mei Zhang: investigation, formal analysis. Wang-Da Cheng: investigation, formal analysis. Gui-Lan Duan: conceptualization, methodology, writing−review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All the data that support the present findings are available as Supplementary information, and the sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject ID No. PRJNA1054742.

-

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U23A2041). We are grateful to Professor Yong-guan Zhu for his helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

-

Plant genotype is a stronger driver of microbiome assembly than domestication status.

Cultivated rice microbiomes show greater sensitivity to nitrogen inputs than wild relatives.

Intraspecific genetic variation governs microbiome-mediated soil carbon dynamics.

Targeting host genetic diversity opens a new avenue for developing microbiome-assisted crops.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yin Y, Delgado-Baquerizo M, García-Palacios P, Zhang HM, Cheng WD, et al. 2025. Genotype identity overrides domestication status in shaping microbial diversity and functions in the rice rhizosphere and phyllosphere. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e013 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0013

Genotype identity overrides domestication status in shaping microbial diversity and functions in the rice rhizosphere and phyllosphere

- Received: 14 October 2025

- Revised: 17 November 2025

- Accepted: 11 December 2025

- Published online: 31 December 2025

Abstract: Rice is one of the major staple foods supporting human populations worldwide. This crop holds a vast amount of genetic variability resulting from the domestication process and the subsequent genotype evolution. Unfortunately, the contribution of genotype identity in explaining microbial diversity and plant-soil functions remains poorly understood in both cultivated rice and its wild progenitors. Here, a glasshouse experiment was conducted to evaluate the influence of three genotypes of domesticated rice and four genotypes of its wild progenitors on soil and plant microbiomes and their functions under contrasting levels of nitrogen fertilization. It was found that the genotype identity of rice had a stronger influence on the structure and functions of the rhizosphere and phyllosphere microbiomes than did the domestication status on the microbial community, nitrogen- and sulfur-cycling genes, and plant pathogens. The interactions between nitrogen fertilization levels and rice genotypes explained a higher variance in multiple aspects of soil and plant microbiomes and their functions than that explained by nitrogen fertilization or domestication status alone. In addition, it was observed that the microbial communities of cultivated rice genotypes were more sensitive to nitrogen fertilization than those of their wild progenitors. The present study reveals the importance of genotypic diversity for the rice microbiome and its functions, which leaves room for microbial-assisted crop improvement for sustainable agriculture.

-

Key words:

- Domestication /

- Genetic variation /

- Wild rice /

- Microbial community /

- Rhizosphere microbiome /

- Phyllosphere microbiome