-

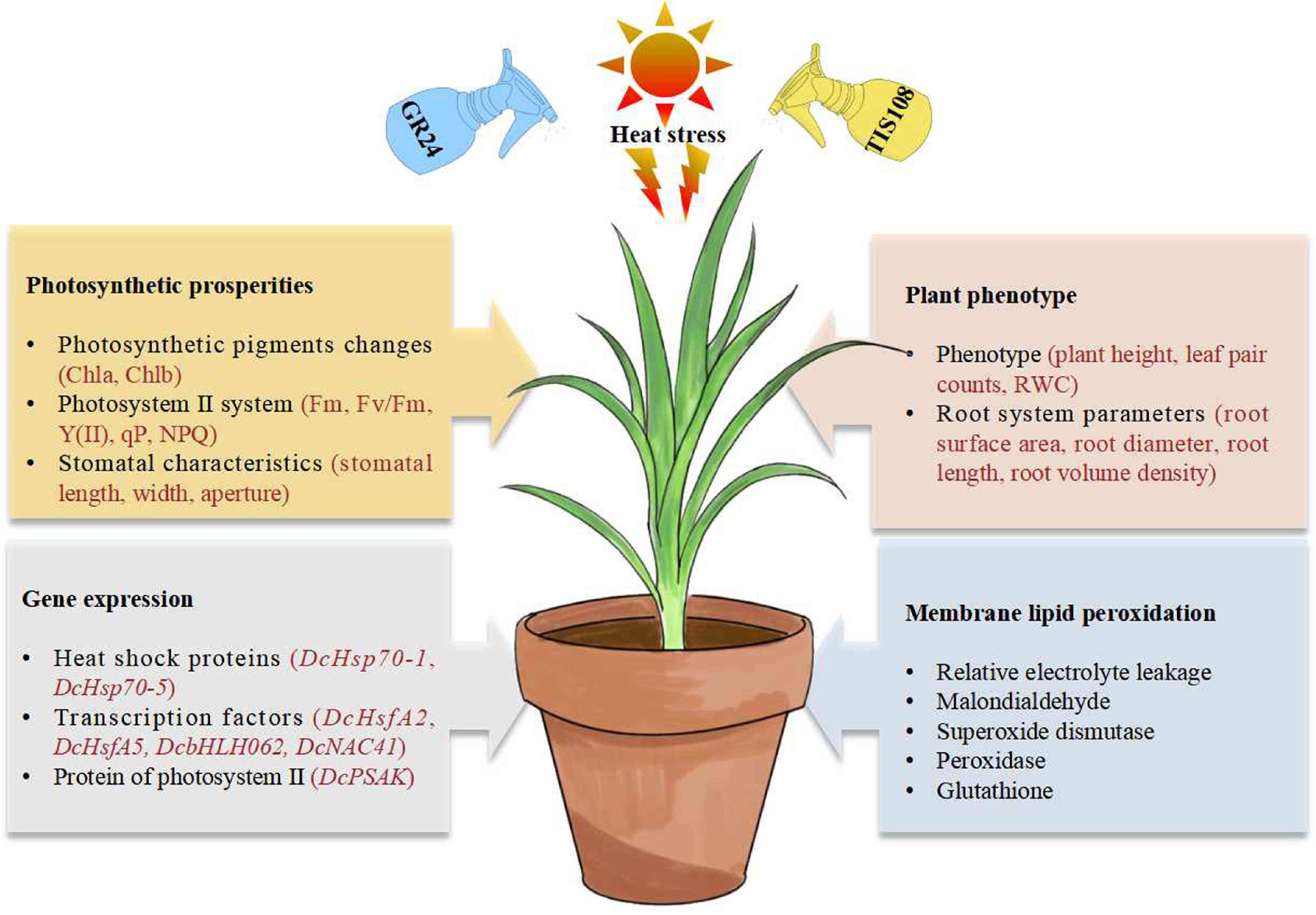

The intensification of global warming and the urban heat island effect are exposing plants to unprecedented thermal stress. Heat stress (HT) elicits a complex cascade of physiological and biochemical responses, including wilting symptoms due to cellular dehydration, disruption of plasma membrane integrity and function, imbalance in antioxidant defense systems, decline in photosynthetic efficiency, and changes in gene expression[1].

HT significantly hampers plant growth and development. It accelerates leaf senescence and abscission while altering root structure by inhibiting the elongation of primary roots and decreasing the formation of lateral roots, which in turn limits water and nutrient acquisition[2]. Concurrently, HT induces metabolic dysfunction. Excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide, disrupts membrane systems. HT also adversely impacts photosynthetic electron transport in both photosystem I (PS I) and II (PS II), exacerbating heat-induced damage. Key manifestations of heat-impaired photosynthesis include reduced photosynthetic pigment content and diminished stomatal opening. The latter restricts CO2 uptake, thereby impairing carbon fixation capacity and reducing net photosynthetic rate. Within the plant heat stress response (HSR) network, heat shock proteins (HSPs) are vital as molecular chaperones that stabilize protein folding, repair denatured proteins, and maintain cellular homeostasis[3]. The expression of HSPs is directly controlled by heat shock transcription factors (HSFs), such as HsfA1 and HsfA2. The activity of these HSFs is regulated by post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and ubiquitination, in response to HT signals[4].

Strigolactones (SLs), carotenoid-derived plant hormones, play crucial roles in plant development and abiotic stress responses[5−7]. SLs improve thermotolerance through multiple mechanisms: strengthening antioxidant defenses, modulating osmolyte accumulation, preserving photosynthetic efficiency and chloroplast integrity, improving root structure and function, regulating stress-related gene (e.g., HSPs) expression, and interacting with other hormone signaling pathways[5,7]. For instance, applying the SL analog GR24 mitigated heat damage on lupine (Lupinus angustifolius) seed germination and PS II function while activating defense responses[8]. Thermoinhibition studies highlighted the key role of SLs in seed germination by regulating gibberellin (GA) and abscisic acid (ABA) levels. GR24 was able to rescue germination defects in mutants, with similar hormonal regulation observed in Arabidopsis secondary dormancy and the parasitic plant Striga hermonthica[9]. SLs promoted root tip elongation in tall fescue under HT and interacted with auxin, positively regulating root development by interfering with auxin transport and cell division[10]. Extreme temperatures could induce the expression of SLs biosynthetic genes and increase SL accumulation in tomato roots[11]. Mutants deficient in SL synthesis or signaling exhibited heightened sensitivity to temperature stress, whereas treatment with GR24 enhanced tolerance. This protective effect correlated with the activation of the ABA pathway, HSP70 chaperones, CBF1 transcription factor, and antioxidant enzymes[11]. The strigolactone inhibitor TIS108 could significantly disrupt SL function by interfering with their biosynthesis, thereby affecting plant branching and root structure[12−14], and exacerbating stress sensitivity[15,16].

Carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus), a flower that thrives in cool seasons, experiences reduced growth and flowering quality when exposed to HT. Researchers have conducted various studies to understand its thermotolerance mechanisms, identify crucial genes, and explore exogenous protectants to address challenges in summer cultivation[17,18]. In this study, a range of GR24 concentrations was tested to determine the optimal dose for mitigating HT effects in carnations. Employing GR24 and SLs inhibitor TIS108, the physiological basis of SL-mediated heat stress relief was investigated by evaluating traits such as plant appearance, membrane stability, antioxidant activity, photosynthesis efficiency, stomatal characteristics, and gene expression. The results contribute mechanistic insights into SL roles under heat stress in carnations, and highlight the practical potential of GR24 foliar application for reducing energy consumption and economic costs in protected cultivation.

-

Seedlings of the carnation variety 'Carimbo', obtained from Brighten Horticulture Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China), were transplanted into pots. The plants were allowed to acclimate prior to experimentation. The strigolactone analog GR24 and its biosynthesis inhibitor TIS108 were purchased from Coolaber Technology (Beijing, China). They were initially dissolved in a small volume of acetone before being diluted with distilled water to their final working concentrations.

To determine the optimal GR24 concentration under heat stress, and to validate the involvement of SLs in thermotolerance, uniformly grown six-week-old seedlings with approximately five pairs of leaves were allocated to different treatment groups. For the concentration screening experiment, six groups (30 plants per group) were established: (1) distilled water under control temperature (CK); (2) distilled water under heat stress (HT); (3) 5 μM GR24 under heat stress (5 μM); (4) 10 μM GR24 under heat stress (10 μM); (5) 15 μM GR24 under heat stress (15 μM); and (6) 20 μM GR24 under heat stress (20 μM). The control temperature was set at 23/18 °C (day/night). Plants were foliar-sprayed daily at 19:00 for three consecutive days before the start of heat stress, applying the solution until droplets formed without dripping. Subsequently, plants were subjected to heat stress at 40/35 °C (day/night) with a 16/8 h light/dark cycle, and 70% relative humidity for 10 d[2,19]. Plant phenotypes were recorded, and samples were collected to analyze photosynthetic pigments, relative electrolyte leakage (REL), malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and antioxidant enzyme activities. For the validation experiment involving GR24 and the biosynthesis inhibitor TIS108, plants were treated with the optimal GR24 concentration or TIS108 under both control and heat stress conditions. The groups included: (1) CK; (2) CK+GR24; (3) CK+TIS108; (4) HT; (5) HT+GR24; and (6) HT+TIS108. Prior to HT, plants received a foliar spray once daily for three consecutive days. Following the onset of HT, sprays were applied every three days throughout the 12 d stress period. Plant samples were collected at three time points: immediately before HT (0 d), and after 0.5 d and 12 d of HT. To evaluate the effects of GR24 and TIS108 on carnation flowering, exogenous spray treatments were conducted for three consecutive days at the pre-flowering stage, followed by a two-day HT period to observe flowering performance. Evaluated parameters included plant morphology, photosynthetic pigments, indicators of membrane integrity, photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidant system activity, stomatal traits, and expression of genes related to stress and SL biosynthesis and signal transduction. A minimum of three replicates was included per experiment.

Growth parameter assessment

-

Plant height was measured vertically from the base up to the apical meristem. The number of fully expanded leaf pairs was counted starting from the base. Leaf and root relative water content (RWC) was determined following the method described by Yang et al.[20]. Samples were weighed immediately after collection to obtain fresh weight (FW), then dried in an oven until reaching a constant weight, cooled, and weighed again to determine dry weight (DW) for RWC calculation. Roots were gently washed to remove soil, spread evenly in a transparent scanning tray to avoid overlap, and scanned using an EPSON Expression 12000 XL root scanner (USA). Root surface area, average root diameter, root length, and volume density were analyzed from the scanned images using WinRHIZO software.

Physiological parameter analysis

-

The amounts of chlorophyll a and b were measured spectrophotometrically after extracting 0.1 g of fresh carnation leaf tissue in 95% ethanol in the dark, until the tissue was fully bleached, with absorbance readings taken at 649 and 665 nm[21]. REL was evaluated by incubating 0.1 g of finely chopped leaves in deionized water with shaking for 2.5 h, recording the initial conductivity, then boiling the sample for 30 min, cooling it down, measuring the final conductivity, and calculating REL[21]. MDA content was determined using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) assay[17]. Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were recorded using a Pocket PEA fluorometer (Hansatech, Germany) and an Imaging-PAM system (Walz, Germany) after 30 min of dark adaptation[19]. For enzyme activity assays, 0.3 g of leaf tissue was homogenized in ice-cold phosphate buffer (NaH2PO4·2H2O/Na2HPO4·H2O), centrifuged, and the supernatant collected. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was assessed by measuring nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) photoreduction[22], while peroxidase (POD) activity was determined through guaiacol oxidation[23]. The content of glutathione, superoxide anion (O2.−), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was measured using a commercial assay kit (Solarbio, BC1170, BC1290, BC3590).

Stomatal observation

-

The abaxial epidermis was gently peeled from the leaves, placed flat in water on a microscope slide, covered with a coverslip, and observed using an optical microscope (Leica DM 500, Germany). Images of the stomata were captured, and parameters were measured using ImageJ software.

Gene expression analysis

-

Total RNA was extracted from 0.1 g of leaf tissue, quantified, and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA following the method described by Sun et al.[24]. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1), with DcGAPDH serving as the reference gene. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method.

Comprehensive evaluation and data analysis

-

A comprehensive evaluation of all measured parameters across different treatment groups was conducted employing membership function analysis in conjunction with principal component analysis (PCA)[17,19]. Data processing and visualization were carried out with Photoshop 2023, Origin 2024, GraphPad Prism 10, and Adobe Illustrator 2021. Statistical significance was determined through one-way ANOVA using SPSS 27.0. Each experiment was performed with a minimum of three replicates.

-

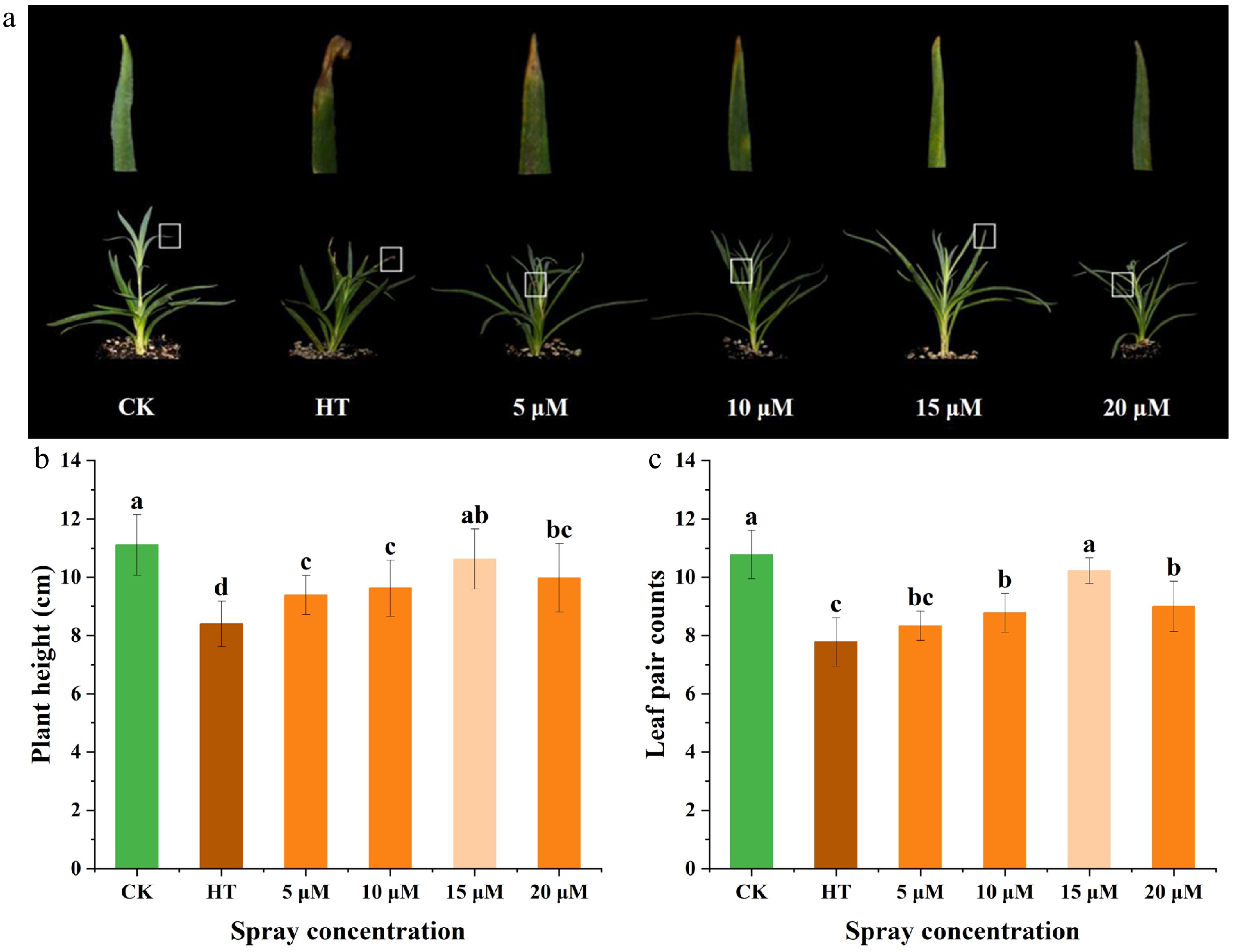

To assess the impact of GR24 pre-treatment on carnation phenotypes subjected to heat stress, seedlings were pre-sprayed with varying concentrations of GR24. Observations revealed that CK plants exhibited dark green foliage and a more extensive canopy spread, whereas HT plants displayed symptoms including leaf tip necrosis, yellowing, and wilting. Pre-treatment with different concentrations of GR24 conferred varying degrees of mitigation against heat damage. Notably, the 15 μM GR24 treatment conferred the most effective protection, preserving large, well-expanded canopies with minimal leaf injury (Fig. 1a). Analysis of plant height revealed that HT significantly inhibited seedling height by 24.4% compared to CK, while exogenous GR24 pre-application alleviated this inhibitory effect. Specifically, plant heights in the 5, 10, 15, and 20 μM GR24 treatment groups increased by 11.77%, 14.55%, 26.45%, and 18.78%, respectively, relative to the HT group (Fig. 1b). Additionally, the number of leaf pairs decreased by 27.83% under HT compared to CK. Pre-treatment with GR24 at concentrations of 5, 10, 15, and 20 μM resulted in increases of 7.14%, 12.86%, 31.43%, and 15.71%, respectively, in leaf pair counts relative to the HT group (Fig. 1c). Collectively, these findings indicated that heat stress inhibited carnation seedling growth and caused thermal injury, whereas pre-application of GR24 mitigated these effects in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

Effects of pre-spraying with different concentrations of GR24 on the phenotype and growth of carnation seedlings under HS. (a) Phenotype. (b) Plant height. (c) Leaf pair counts. CK: distilled water under control temperature, HT: distilled water under heat stress, 5 μM: 5 μM GR24 under heat stress, 10 μM: 10 μM GR24 under heat stress, 15 μM: 15 μM GR24 under heat stress, 20 μM: 20 μM GR24 under heat stress. Data shown as mean ± SD, and different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Physiological responses of carnation seedlings to heat stress following GR24 treatment at varying concentrations

-

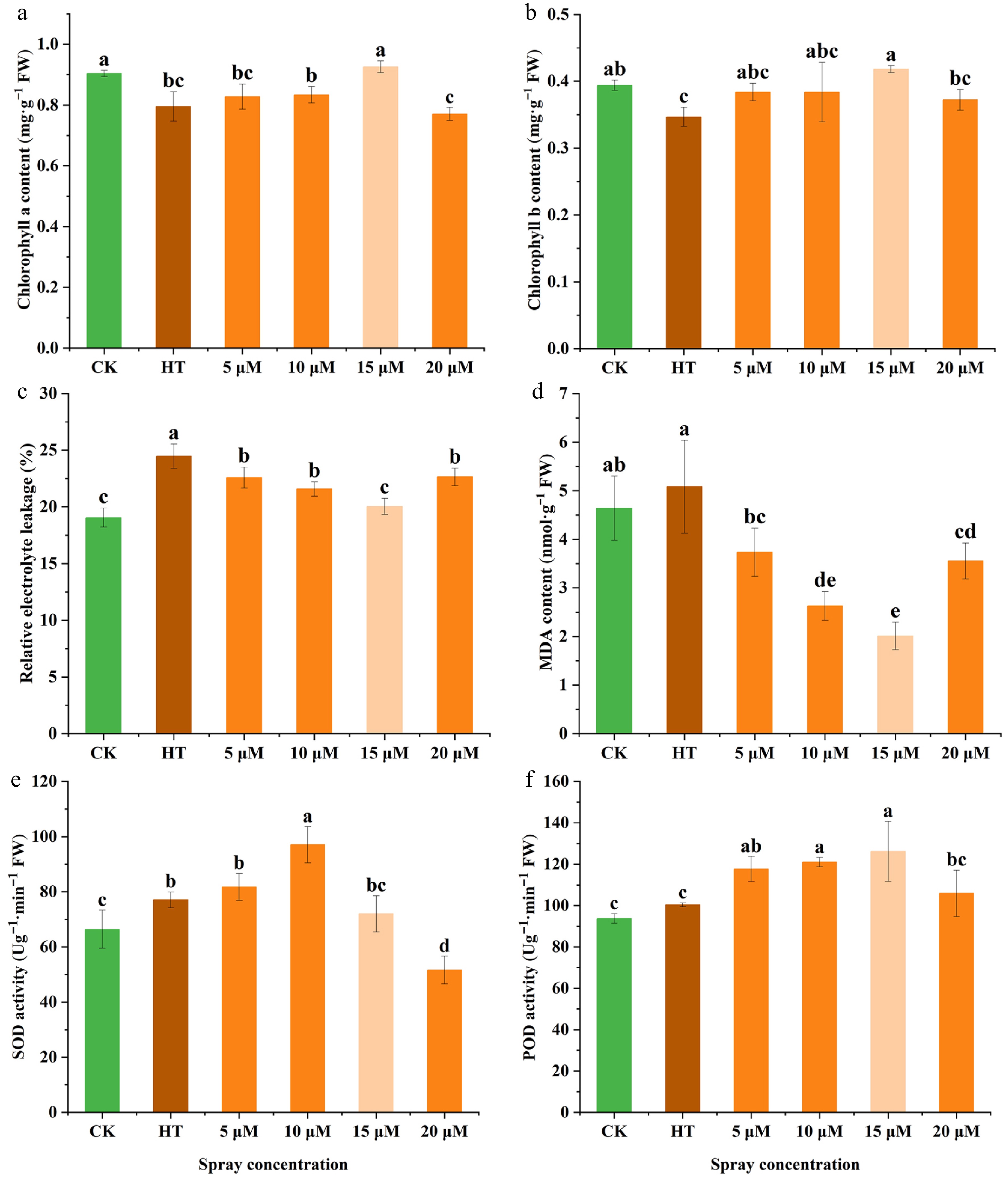

HT adversely affected photosynthetic efficiency, membrane stability, and antioxidant defense mechanisms in carnation seedlings. Relative to CK, HT significantly suppressed the levels of chlorophyll a and b. Pre-treatment with GR24 counteracted this reduction, with 15 μM concentration producing the most pronounced increases of 14.09% and 20.66% in chlorophyll a and b content, respectively, compared to HT alone (Fig. 2a, b). HT also elevated REL, indicative of membrane damage; however, pre-spraying of GR24 at various concentrations significantly decreased REL under HT conditions. Notably, the 15 μM GR24 treatment restored REL to near CK level, achieving a 33% reduction relative to HT (Fig. 2c). MDA contents exhibited a similar pattern, with the 15 μM GR24 pre-treatment group showing a 60.48% decrease compared to HT (Fig. 2d). These results collectively demonstrated that GR24 treatment at different concentrations mitigated membrane system damage in carnation seedlings subjected to elevated temperatures. Further examination of antioxidant enzyme activities revealed that SOD activity varied among treatment groups, with the 10 μM GR24 treatment eliciting a 25.90% increase relative to the HT (Fig. 2e). Regarding POD activity, the 15 μM GR24 group exhibited the most substantial enhancement, increasing by 25.70% compared to HT, followed by the 10 μM group with a 20.55% increase (Fig. 2f). These results demonstrated that treatment with varying concentrations of GR24 modified the physiological parameters in carnation seedlings under heat stress, thereby contributing to improved stress tolerance.

Figure 2.

Effects of pre-spraying with different concentrations of GR24 on the physiological properties of carnation seedlings under HS. (a) Chlorophyll a content. (b) Chlorophyll b content. (c) Relative electrolyte leakage. (d) MDA content. (e) SOD activity. (f) POD activity. Data shown as mean ± SD, and different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Evaluation of the optimal GR24 concentration for alleviating heat damage in carnation

-

The preceding data demonstrated that pre-spraying of GR24 at varying concentrations could alleviate heat-induced damage in carnation seedlings, albeit with differential efficacy. To determine the most effective GR24 concentration for pre-spray treatment, a correlation analysis was conducted on the measured parameters. The analysis revealed significant positive correlations between plant height and both the leaf pair counts and chlorophyll b content (Supplementary Fig. S1), as well as significant negative correlations between REL and plant height, leaf pair counts, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b (Supplementary Fig. S1). Furthermore, evaluation of membership function values ranked the treatments in the following order: 15 μM > 10 μM > 5 μM > 20 μM (Supplementary Table S2). Based on these findings, 15 μM GR24 was selected for subsequent experimental investigations.

Effects of GR24 and TIS108 on growth and physiological characteristics in heat-stressed carnation

-

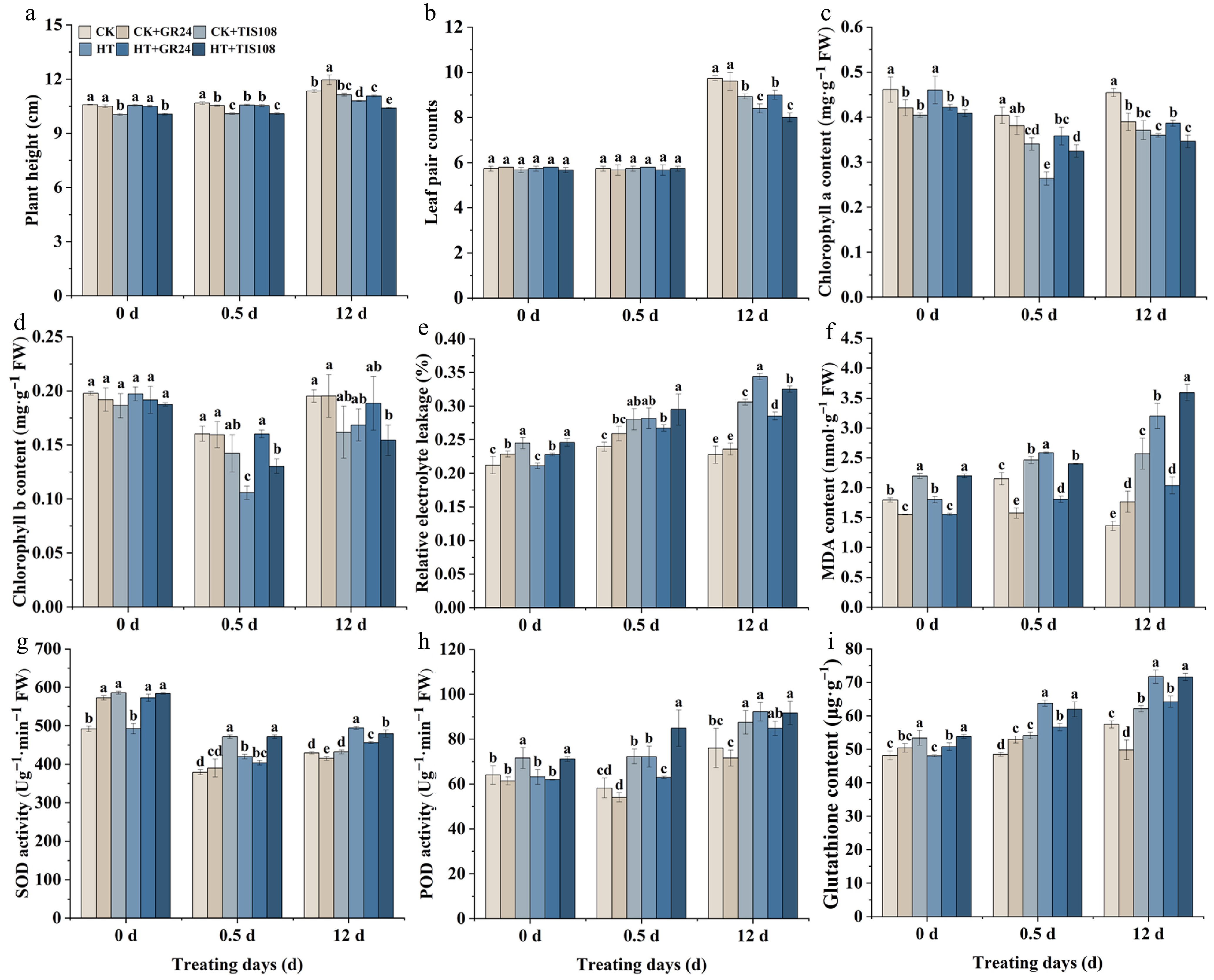

Pre-application of 15 μM GR24 or TIS108 was employed to analyze their impacts on the growth and physiological responses of carnation seedlings subjected to heat stress durations of 0, 0.5, and 12 d. The findings indicated that pretreatment with TIS108 significantly decreased plant height across all stress intervals, whereas GR24 alleviated this inhibitory effect. Notably, after 12 d of heat exposure, plant height in the HT+GR24 group was 3.01% higher than that in the HT group, while the HT+TIS108 group exhibited a 3.58% reduction relative to HT (Fig. 3a). No significant differences of leaf pair counts were detected among treatment groups under control conditions or after 0.5 d of heat stress. However, following 12 d of heat stress, the HT group exhibited a significant 13.70% decline compared to the CK. This reduction was further intensified by TIS108 treatment, with the HT+TIS108 group demonstrating an additional 4.76% decrease relative to HT. Conversely, exogenous application of GR24 significantly increased leaf pair counts by 7.14% in the HT+GR24 group compared to HT (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on the growth and physiological properties of carnation seedlings under HS. (a) Plant height. (b) Leaf pair counts. (c) Chlorophyll a content. (d) Chlorophyll b content. (e) Relative electrolyte leakage. (f) MDA content. (g) SOD activity. (h) POD activity. (i) Glutathione content. Plants were subjected to foliar sprays once daily for 3 d prior to the heat stress (HT) treatment and subsequently every three days during the 12 d HT period, with sampling conducted at 0 (pre-HT), 0.5, and 12 d of HT. Data shown as mean ± SD, and different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Assessment of chlorophyll content in seedlings from CK, CK+GR24, CK+TIS108, HT, HT+GR24, and HT+TIS108 treatments at 0, 0.5, and 12 d of heat stress demonstrated that elevated temperature inhibited the synthesis of both chlorophyll a and b. GR24 pretreatment mitigated this elevated (Fig. 3c, d). REL in the HT+GR24 group decreased by 5.11% and 17.06% after 0.5 d and 12 d of heat stress, respectively, compared to the HT group. In contrast, the HT+TIS108 group consistently exhibited higher REL than HT+GR24, suggesting that the strigolactone inhibitor TIS108 aggravated heat-induced cellular damage in carnation (Fig. 3e). Heat stress also induced MDA accumulation. Relative to CK, MDA content in the HT group increased by 20.40% at 0.5 d, and 135.00% at 12 d. GR24 treatment reduced MDA contents by 30.22% and 36.34%, compared to HT at these respective time points, whereas TIS108 pretreatment exhibited the opposite effect, promoting MDA accumulation (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, heat exposure elicited antioxidant responses. Compared to CK, the HT group exhibited exhibited SOD activity (10.67% at 0.5 d; 15.02% at 12 d), POD activity (24.00% at 0.5 d; 21.29% at 12 d), and glutathione content (31.41% at 0.5 d; 24.87% at 12 d). GR24 treatment suppressed these increases under heat stress conditions, while TIS108 restored their activity levels (Fig. 3g−i). These results demonstrated that GR24 effectively alleviated heat damage in carnation seedlings, while the strigolactone inhibitor TIS108 exacerbated heat stress injury.

Effects of GR24 and TIS108 on chlorophyll fluorescence phenotypes and parameters in heat-stressed carnation

-

Analysis of chlorophyll fluorescence phenotypes in carnation seedlings revealed no significant differences in Fv/Fm, Fm, or Y(NO) among the treatment groups at 0 d. However, at 0.5 d, leaf tip damage was observed in the HT and HT+TIS108 groups, as reflected by changes in Fv/Fm phenotypes. At 12 d, all groups exhibited signs of photosynthetic impairment; nevertheless, the HT+GR24 group maintained significantly better leaf morphology compared to the HT and HT+TIS108 groups (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Examination of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters demonstrated significant alterations in PSII function under prolonged heat stress. Compared to CK, Fv/Fm decreased by 10.12% at 0.5 d, and 11.64% at 12 d, with Y(II), qP, and Fm exhibiting similar declining trends, while NPQ and Fo progressively increased. Application of GR24 effectively mitigated these heat-induced alterations. In contrast, treatment with TIS108 intensified changes in Y(II), Fo, and Fm relative to the HT group (Supplementary Fig. S2b–g). Collectively, these results demonstrated that strigolactones played a critical role in regulating photosynthesis responses under heat stress conditions.

Effects of GR24 and TIS108 on the phenotype and RWC in heat-stressed carnation

-

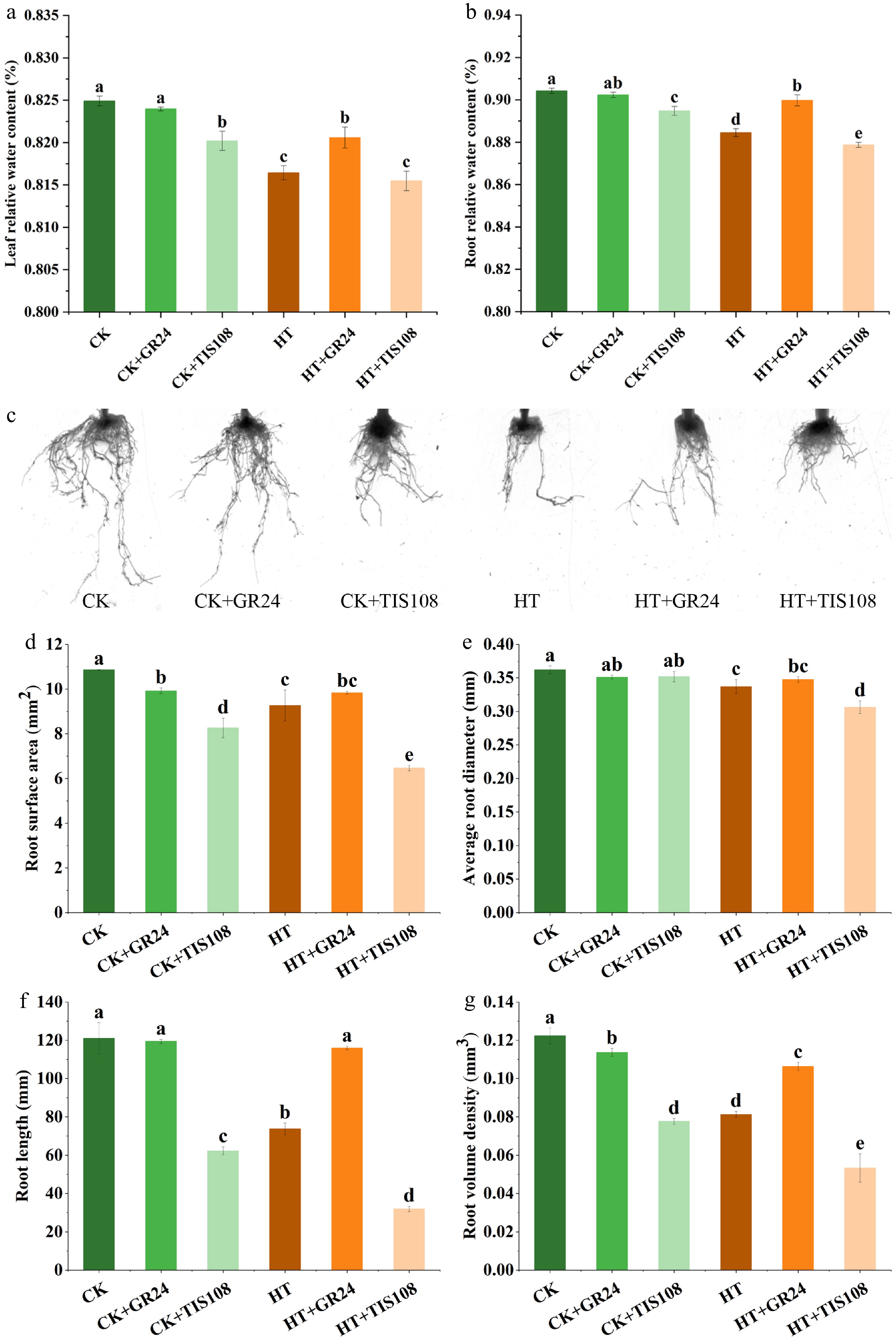

In light of the pronounced effects observed at 12 d, the phenotype and the RWC in carnation leaves and roots subjected to heat stress for 12 d following pre-application of GR24 and TIS108 were analyzed. The results showed that under control temperature, pre-treatment with GR24 or TIS108 had no significant effect on the phenotype of carnation. However, pre-spraying with GR24 provided a certain mitigating effect on carnation seedlings under heat stress (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, GR24 pretreatment had no significant effect on the RWC of leaves and roots in carnation seedlings maintained at control temperature, while TIS108 treatment resulted in a significant reduction of RWC in both tissues. After 12 d of heat stress, the RWC of leaves and roots in the HT group decreased by 1.03% and 2.18%, respectively, compared to the CK. Notably, the RWC levels in the HT+GR24 group were significantly increased compared to the HT group. Conversely, no mitigation of HT-induced RWC reduction was detected in the HT+TIS108 group (Fig. 4a, b).

Figure 4.

Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on relative water content and root systems of carnation seedlings under HS. (a) Leaf relative water content. (b) Root relative water content. (c) Root phenotype. (d) Root surface area. (e) Average root diameter. (f) Root length. (g) Root volume density. Data shown as mean ± SD, and different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Effects of GR24 and TIS108 on flowering and ornamental quality of carnation

-

To explore the role of SL in carnation flowering under heat stress, the effects of GR24 and TIS108 application on flowering traits under both CK and HT conditions were analyzed. The results showed that under CK condition, neither GR24 nor TIS108 treatment significantly affected overall flowering quality compared to the CK group. However, HT caused noticeable wilting and color fading in the HT group, while the HT+GR24 group maintained relatively better flowering quality (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Further assessment of oxidative stress indicators revealed that HT significantly aggravated oxidative damage. Compared to CK, the HT group had notably higher levels of MDA, O2·−, and H2O2. In contrast, GR24 pretreatment effectively alleviated heat-induced oxidative damage, reducing these indicators by 24.24%, 39.07%, and 23.77%, respectively, compared to the HT group. Conversely, TIS108 treatment worsened the negative effects of heat stress. The HT+TIS108 group showed greater accumulation of MDA and ROS, with levels rising by 15.64%, 32.82%, and 13.74%, respectively, compared to the HT group (Supplementary Fig. S4b–d).

Effects of GR24 and TIS108 on the root system in heat-stressed carnation

-

Analysis of root system responses revealed that both heat stress and chemical treatments exerted significant impacts on carnation root development (Fig. 4c). Specifically, in comparison to the CK group, the HT group exhibited marked reductions in root surface area (14.70%), average root diameter (6.91%), root length (39.05%), and root volume density (33.52%). Application of GR24 mitigated the detrimental effects of heat stress on carnation roots. Relative to the HT group, the HT+GR24 treatment resulted in significant increases of 6.15%, 3.17%, 57.28%, and 30.74% in the respective parameters. Conversely, application of TIS108 exacerbated root growth inhibition, as evidenced by decreases of 30.21%, 9.10%, 56.66%, and 34.43% in these root system metrics in the HT+TIS108 group compared to HT (Fig. 4d–g). These results demonstrated that an optimal concentration of GR24 effectively mitigated heat-induced root damage, while TIS108 exerted antagonistic effects.

Effects of GR24 and TIS108 on stomatal characteristics in heat-stressed carnation

-

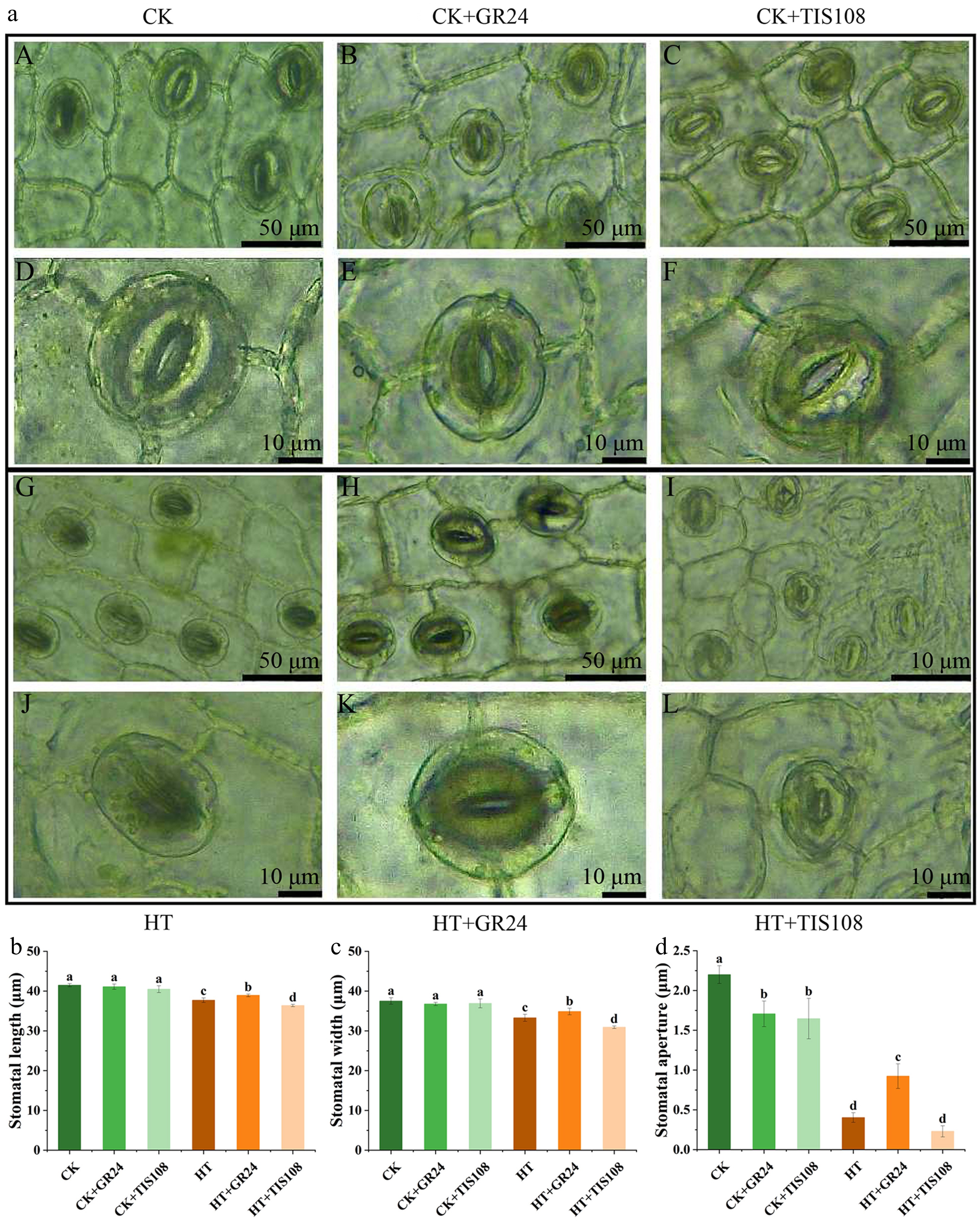

Heat stress markedly influenced stomatal morphology in carnation leaves (Fig. 5a). Compared to CK, the HT group exhibited reductions in stomatal length, width, and aperture by 9.10%, 11.23%, and 81.67%, respectively (Fig. 5b–d). Under normal conditions (CK), exogenous application of GR24 (CK + GR24) or inhibitor TIS108 (CK+TIS108) did not produce significant changes in stomatal characteristics compared to CK. However, pretreatment with GR24 under heat stress (HT+GR24) significantly increased stomatal length, width, and aperture by 3.24%, 4.78%, and 128.93%, respectively, relative to HT alone. Conversely, TIS108 treatment under heat stress (HT+TIS108) further decreased stomatal length, width, and aperture by 3.56%, 7.11%, and 42.97%, respectively, compared to HT (Fig. 5b–d). These results demonstrated that GR24 and TIS108 modulated stomatal adaptation to heat stress.

Figure 5.

Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on stomatal characteristics of carnation seedlings under HS. (a) A, D: CK; B, E: CK+GR24; C, F: CK+TIS108; G, J: HT; H, K: HT+GR24; I, L: HT+TIS108. (b) Stomatal length. (c) Stomatal width. (d) Stomatal aperture. Data shown as mean ± SD, and different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Effects of GR24 and TIS108 on gene expression in heat-stressed carnation

-

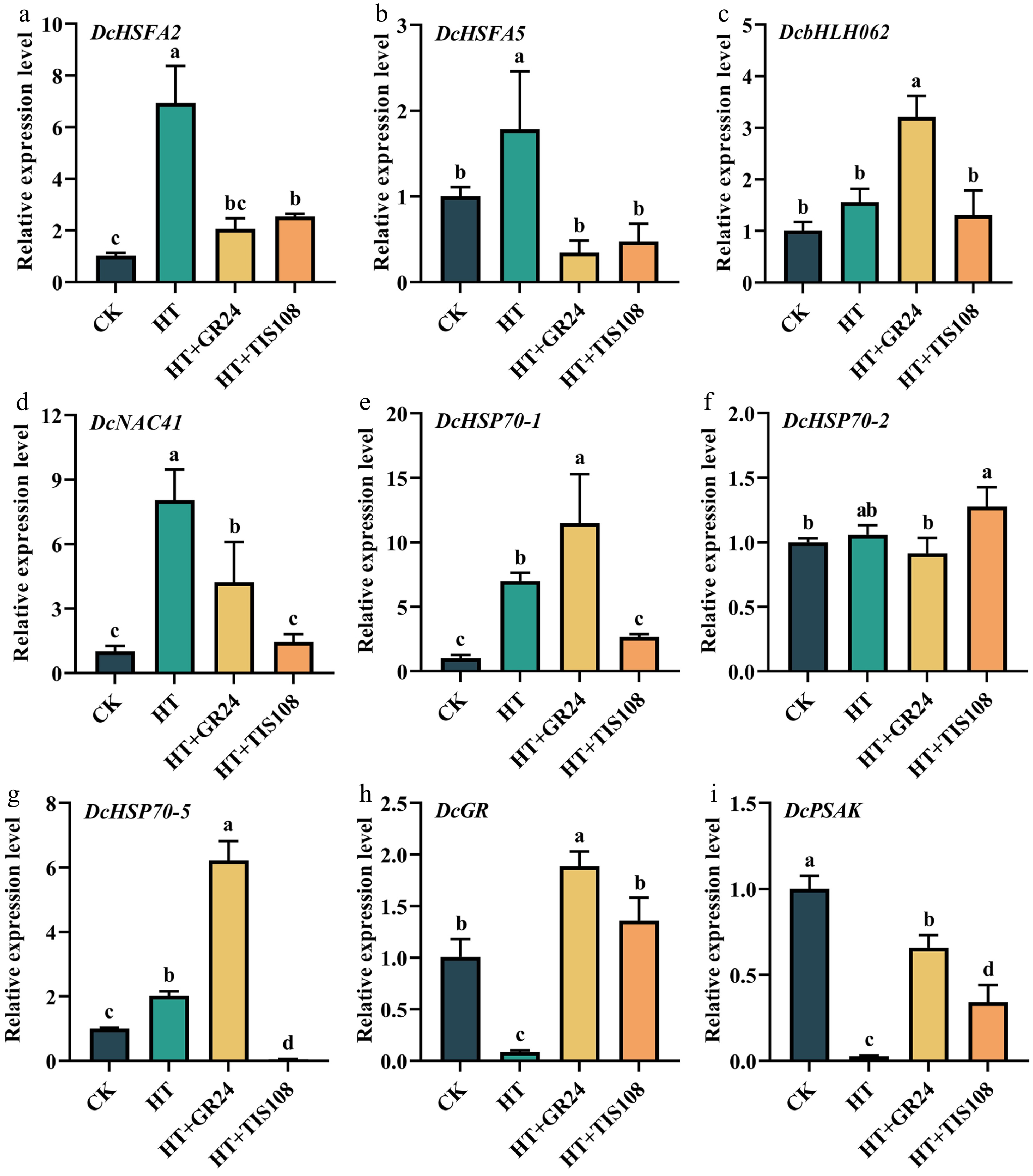

Molecular-level investigations were conducted to elucidate the effects of GR24 and TIS108 on carnation seedlings subjected to HT. The results indicated that both HT and exogenous applications significantly modulated the expression of genes associated with stress response and photosynthesis (Fig. 6). Specifically, HT significantly upregulated the expression of heat shock transcription factors (DcHSFA2, DcHSFA5), the NAC transcription factor (DcNAC41), and heat shock protein genes (DcHSP70-1, DcHSP70-5), while concurrently downregulating the glutathione reductase gene (DcGR) and PS II gene (DcPSAK). Treatment with GR24 under HT conditions (HT+GR24) notably suppressed the HT-induced upregulation of DcHSFA2, DcHSFA5, and DcNAC41, yet enhanced the expression of DcbHLH062, DcHSP70-1, and DcHSP70-5, and attenuated the HT-induced repression of DcGR and DcPSAK. Conversely, TIS108 treatment (HT+TIS108) showed a comparable inhibitory effect on DcHSFA2 and DcHSFA5 expression as observed in the HT+GR24 group, but aggravated the inhibition of DcbHLH062, DcNAC41, DcHSP70-1, and DcHSP70-5 under HT. Notably, HT+TIS108 treatment resulted in significantly elevated expression of DcHSP70-2 compared to all other groups. Although TIS108 treatment maintained significantly higher expression levels of DcGR and DcPSAK compared to the HT group, these levels remained significantly lower than those observed in the HT+GR24 group (Fig. 6). Furthermore, we designed and conducted an analysis to examine the expression levels of key genes involved in the SL biosynthesis and signal transduction pathways. The results showed that HT and exogenous applications had no significant effect on the expression of the SL biosynthesis-related gene DWARF27 (DcD27, Supplementary Fig. S5a). However, pre-treatment with GR24 notably increased the expression of the cytochrome P450 MORE AXILLARY GROWTH 1 (DcMAX1) under HT (Supplementary Fig. S5b). Heat stress stimulated the expression of the SL signaling gene DcD14 (DWARF14), but suppressed the expression of DcSMXL8 (SUPPRESSOR OF MAX2 1-LIKE 8), while it did not significantly impact DcMAX2 expression. Pre-treatment with GR24 under HT (HT+GR24) significantly elevated the expression levels of DcD14, DcMAX2, and DcSMXL8 (Supplementary Fig. S5c–e). Conversely, treatment with TIS108 modified the expression of these genes, with expression levels showing no significant difference compared to those under HT alone (Supplementary Fig. S5c–e). Collectively, these results suggest that GR24 and TIS108 contribute to the thermotolerance of carnation seedlings by exerting differential regulatory effects on stress-responsive genes and the SL biosynthesis and signaling network.

Figure 6.

Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on gene expression of carnation seedlings under HS. (a) DcHSFA2. (b) DcHSFA5. (c) DcbHLH062. (d) DcNAC41. (e) DcHSP70-1. (f) DcHSP70-2. (g) DcHSP70-5. (h) DcGR. (i) DcPSAK. Data shown as mean ± SD, and different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

-

Heat stress typically inhibits plant morphological development, diminishes growth rates, induces membrane lipid peroxidation damage, and compromises photosynthetic efficiency as well as gene transcription levels[25,26]. Exogenous compounds have been recognized as crucial agents in alleviating stress-induced damage in plants[27−29]. SLs serve not only as independent defense signaling molecules but also as key integrators that coordinate morphological plasticity, physiological and biochemical defense responses, symbiotic relationship establishment, and intricate hormonal signaling networks, thereby synergistically enhancing plant adaptation to environmental stresses[5,7,30]. Empirical evidence has demonstrated that the SL analog GR24 can effectively enhance plant tolerance to various abiotic stresses[8−11]. To address the limitations inherent in single-parameter evaluations, the present study implemented a comprehensive assessment framework incorporating both phenotypic characteristics and physiological parameters. This integrated approach identified 15 μM GR24 as the optimal concentration for alleviating heat-induced damage in carnation seedlings (Figs. 1, 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Importantly, prior research has indicated that the optimal concentration of GR24 varies depending on species and environmental conditions, with reported effective doses including 0.01 μM for tall fescue[10], 3 or 15 μM for tomato[11,16], and 10 μM for cucumber[15]. These findings highlight the necessity for precise calibration of GR24 application tailored to specific plant species and stress contexts.

The SL inhibitor TIS108 specifically targets carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 8 (CCD8), a key enzyme in the SL biosynthesis pathway, thereby disrupting SL synthesis and providing reverse genetic evidence of SLs' role in stress responses[31]. The effective dose of this inhibitor varies depending on the plant species, type of stress, and treatment duration[16,32,33]. Under stress conditions, plants treated with TIS108 typically exhibit more severe reductions in stress tolerance compared to untreated controls. In this study, pre-treatment with TIS108 negated the protective effects of GR24, resulting in further impairment to root architecture, dysregulated of stomatal conductance, inhibited photosynthesis, and altered gene expression (Figs. 3−6, Supplementary Fig. S2). Similar inhibitory effects of TIS108 were observed in cucumber, tomato, and tall fescue, including decreased germination rates, significant biomass loss, aggravated oxidative damage[15,16], and suppressed development of lateral roots and root hairs[15,16,33].

Abiotic stress conditions frequently inhibit photosynthetic activity in plants. Chlorophyll, a critical pigment involved in photosynthesis, exhibits markedly reduced levels in grape and sunflower plants subjected to stress. However, exogenous application of GR24 has been shown to counteract these reductions[34]. Moreover, treatment with GR24 mitigated heat-induced impairment of photosystem II in lupin (Lupinus angustifolius) seedlings[8]. In the present study, pre-treatment with GR24 alleviated the heat-induced suppression in chlorophyll a and b contents in carnation seedlings and enhanced chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Figs. 3c, d and Supplementary Fig. S2). SLs were found to inhibit enzymes responsible for chlorophyll degradation while activating key enzymes involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis, thereby attenuating stress-induced pigment loss[35]. Additionally, stress adversely affected the root system architecture, whereas the GR24 treatment optimized it by promoting root length and suppressing adventitious root formation[7,10]. Here, HT significantly inhibited root surface area, average diameter, length, and volume density in carnation seedlings; these inhibitory effects were alleviated by GR24 pre-treatment but exacerbated by TIS108 application (Fig. 4). Investigations involving SL-deficient mutants and GR24 application has confirmed that SLs positively regulate primary root elongation, overall root growth, and lateral branching, while inhibiting lateral root initiation and adventitious root development[35−37]. This regulatory effect is mediated through GR24-induced modulation of genes governing cell division at the root tip[10].

Under abiotic stresses such as elevated temperature, plants reduce transpirational water loss by closing stomata. SLs have been demonstrated to induce stomatal closure independently of the abscisic acid (ABA) pathway, activating a cascade involving RBOH-mediated H2O2 production and nitrate reductase (NR)-dependent nitric oxide (NO) generation within guard cells, as evidenced in Arabidopsis mutants deficient in SL biosynthesis and signaling[7,34,38]. Furthermore, SLs regulated stomatal reopening during recovery from drought stress via the miR156-SPL9 regulatory module[39]. In the current study, GR24 significantly alleviated the heat-induced suppression in stomatal aperture (Fig. 5). Under heat stress conditions, GR24 maintained stomatal opening to balance heat dissipation and photosynthetic efficiency by activating protective mechanisms, including the antioxidant defense system. This protective effect was associated with ABA signaling pathways and the induction of stress-responsive genes[11].

Heat stress strongly upregulated the expression of HSFAs and HSPs[40,41]. Among these, HSFA2 functions as a central regulator that enhances thermotolerance by activating downstream HSPs[42]. Additionally, NAC and bHLH transcription factors participated in heat stress signaling pathways[42,43]. The present study demonstrated that GR24 modulated the expression of these transcription factors and HSPs to maintain proteostasis by suppressing stress responses and enhancing molecular chaperone activity. Mechanistically, SLs might regulate stress-responsive gene expression by promoting the MAX2-D3 ubiquitin ligase complex-mediated degradation of transcriptional repressors[35,44]. Furthermore, GR24 alleviated the suppression of DcPSAK (Fig. 6i), a critical component of PS II, suggesting its role in safeguarding the photosynthetic apparatus against thermal damage[7,35]. Conversely, inhibition of stress-related transcription factors and protective enzymes by TIS108 implied that SL deficiency compromised heat stress tolerance mechanisms[15].

The expression of key genes in the SL biosynthesis and signaling pathways can be regulated by stress conditions. In rice, sulfur deficiency stress was shown to induce the expression of the SL biosynthesis gene D27, but had no effect on the expression of D10, D17, or OsMAX1[45]. Under phosphorus-deficient conditions, exogenous GR24 application upregulated the expression of various stress-responsive genes, including those related to oxidoreductase activity[46]. Similarly, in soybean and cucumber, stresses such as low light and salt have been reported to alter the expression of biosynthesis genes such as D27 and MAX1, as well as signaling genes such as D14 and MAX2[47,48]. Exogenous SL application can enhance plant stress resistance by modulating endogenous hormone homeostasis and gene expression. In grapevine, GR24 treatment alleviated drought-induced imbalances in endogenous hormones such as IAA, ABA, ZR, and MeJA, restoring them to near-normal levels. Concurrently, GR24 upregulates the expression of D14 and antioxidant enzyme genes (e.g., POD), while downregulating the expression of certain transcription factors such as MYBs and WRKYs, thereby mitigating stress-induced damage[49]. Furthermore, experiments using TIS108, along with GR24 treatment, confirmed that these chemicals significantly affect the expression of SL pathway-related genes (Supplementary Fig. S5), underscoring the central role of the SL signaling pathway in stress responses[32].

-

This research clarified the function of SLs in the heat stress response of carnation. A thorough assessment combining phenotypic and physiological measurements identified 15 μM GR24, a synthetic SL analog, as the optimal concentration to alleviate heat-induced damage in carnation seedlings. Pre-treatment with GR24 effectively preserved cell membrane integrity, enhanced leaf chlorophyll content, and restored the photochemical efficiency of PS II under heat stress. Additionally, GR24 reduced heat-induced growth inhibition, optimized root system architecture, and improved leaf stomatal traits. Concurrently, GR24 significantly modulated the expression levels of key heat-responsive genes, collectively helping to reduce heat damage. Antagonistic experiments using TIS108 further confirmed that SLs play a crucial role in enhancing thermotolerance in carnation seedlings (Fig. 7). These findings provide a scientific foundation for applying SL regulation strategies to improve thermotolerance and enable cost-effective cultivation of carnations.

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32271940), College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2024-1696), and Postgraduate Innovation Program of Qingdao Agricultural University (Grant No. QNYCX24071).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wan X, Jiang X, Xu J, Wang G; data collection: Guo D, Xu J, Wang G, Jing Y, Liu Z, Zhang XH; analysis and interpretation of results: Xu J, Wang G; draft manuscript preparation: Guo D, Xu J, Wang G, Zhang XN, Wan X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Dandan Guo, Jinxin Xu, Guopeng Wang

- Supplementary Table S1 Primer sequences of the analyzed genes.

- Supplementary Table S2 Subordination function evaluation of alleviating effects of different concentrations of GR24 under HS.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Correlation analysis of indexes of carnation treated with different concentrations of GR24 under HS.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of carnation seedlings under HS.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on phenotype of carnation seedlings under CK and HS.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on flowering and ornamental quality of carnation.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Effects of pre-spraying with GR24 and TIS108 on gene expression of SL biosynthesis and signal transduction under HS.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Guo D, Xu J, Wang G, Jing Y, Liu Z, et al. 2026. Strigolactone enhance thermotolerance in carnation seedlings. Ornamental Plant Research 6: e001 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0045

Strigolactone enhance thermotolerance in carnation seedlings

- Received: 15 August 2025

- Revised: 29 September 2025

- Accepted: 20 October 2025

- Published online: 13 January 2026

Abstract: High temperatures significantly hinder the cost-effective cultivation of carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) by negatively affecting its growth and flowering quality. Strigolactones (SLs), plant hormones derived from carotenoids, are vital for plant development and responses to abiotic stresses. In this study, 15 μM was identified as the optimal concentration of the SL analog GR24 to alleviate heat damage (40/35 °C) in carnation seedlings, based on a thorough evaluation of morphological and physiological indicators after pretreatment with varying GR24 concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20 μM). Using 15 μM GR24 and the SL biosynthesis inhibitor TIS108, changes in phenotype, physiological traits, photosynthetic performance, root architecture, stomatal morphology, and expression of stress-related genes under heat stress (HT) were then examined. After 12 d of HT, GR24 pre-spraying significantly mitigated HT-induced reductions in plant height and leaf pair counts by 3.01% and 7.14%, respectively, while decreasing relative electrolyte leakage (REL), and malondialdehyde (MDA) content by 17.06% and 36.34%, compared to HT. Additionally, GR24 helped preserve photosynthetic efficiency by mitigating HT-related declines in parameters such as Fv/Fm and improving stomatal structure. It also supported root growth, increasing root length by 57.28% and root volume density by 30.74% relative to HT. Furthermore, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that GR24 modulated gene expression, promoting transcripts of DcbHLH062, DcHSP70s, DcMAX1, DcD14, DcMAX2, and DcSMXL8 under HT, while alleviating the suppression of DcGR and DcPSAK expression. Treatment with TIS108 provided reverse validation. These findings offer valuable insights into applying GR24 to enable energy-saving carnation cultivation under heat-stress conditions.

-

Key words:

- Carnation /

- GR24 /

- Heat stress /

- Strigolactone /

- Thermotolerance