-

With the accelerated global push for ecological civilization and the rapid growth of the green economy, wild flowers, which have both ecological and economic value, are increasingly deemed as a key link between biodiversity conservation and sustainable development[1]. Among them, Melastoma species attract attention due to their wide distribution in tropical and subtropical regions, distinctive traits such as heteromorphic stamens, and diverse uses in ornamental horticulture, traditional medicine, and ecological restoration[2−4].

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing, multi-omics integration, and gene-editing technologies have shifted research on Melastoma from basic taxonomy and resource surveys to molecular studies of evolution and functional genes. Analyses of nuclear, mitochondrial, and chloroplast genomes clarified how genetic diversity forms and evolves in the genus[5−8]. They have also revealed molecular networks controlling key traits, including heteromorphic stamen differentiation and aluminum hyper-accumulation[9,10].

This review summarizes the distribution, phenotypic and functional diversity, medicinal and edible potential, and genomic research progress of Melastoma. It also examines how morphological traits co-evolve with ecological adaptation and highlights current research challenges. Finally, future directions for breeding and applications are proposed. These efforts aim to support targeted improvement, sustainable utilization, and practical use of Melastoma in ecological restoration, horticulture, and medicine. They will also contribute to ecological civilization and the green economy.

-

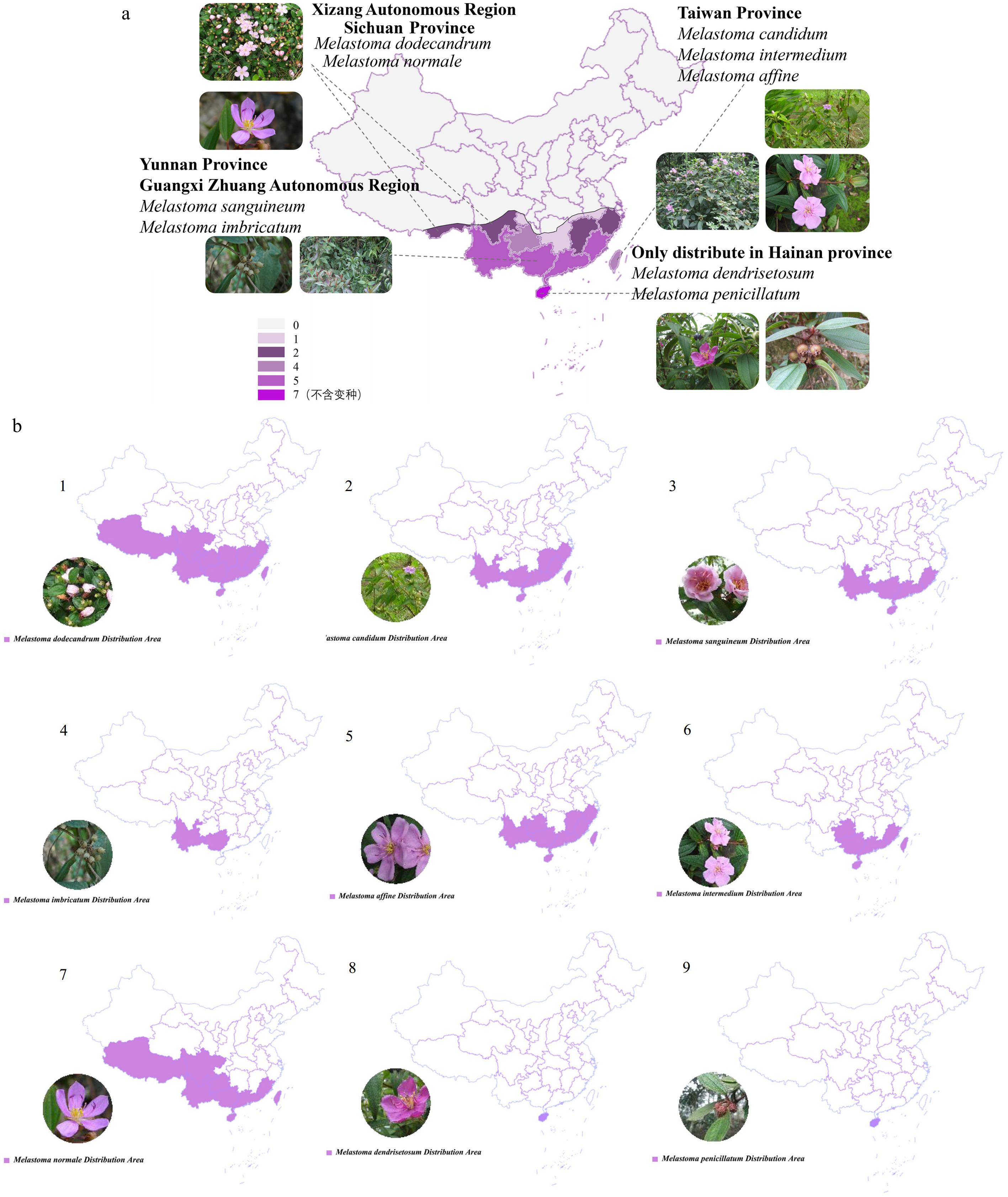

The Melastomataceae family, comprising approximately 5,857 species across 176 genera, is divided into three subfamilies: Kibessioideae (15 species), Olisbeoideae (556 species), and Melastomatoideae (5,287 species). These species are primarily found in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide[11−13]. Approximately 100 species are distributed from southern Asia to northern Oceania and the Pacific islands. In China, around nine native species are distributed in regions south of the Yangtze River[14]. Among them, Melastoma dodecandrum is widely distributed in regions south of the Yangtze River, excluding Hainan and Taiwan. Melastoma dendrisetosum and Melastoma penicillatum are found only in Hainan, while Melastoma imbricatum is restricted to Yunnan in China. In terms of vertical distribution, the distribution of Melastoma species varies with altitude, geographical location, and terrain. M. imbricatum, M. candidum, M. dendrisetosum, M. sanguineum, and M. sanguineum var. latisepalum grow at lower altitudes, while the other five species are found at altitudes above 1,000 m[7,15,16] (Figs. 1, 2).

Figure 1.

Quantity distribution maps. (a) Species of Melastoma in various provinces of China. (b) The specific distribution of nine species of Melastoma plants. 1: Melastoma dodecandrum, 2: Melastoma candidum, 3: Melastoma sanguineum, 4: Melastoma imbricatum, 5: Melastoma affine, 6: Melastoma intermedium, 7: Melastoma normale, 8: Melastoma dendrisetosum, 9: Melastoma penicillatum.

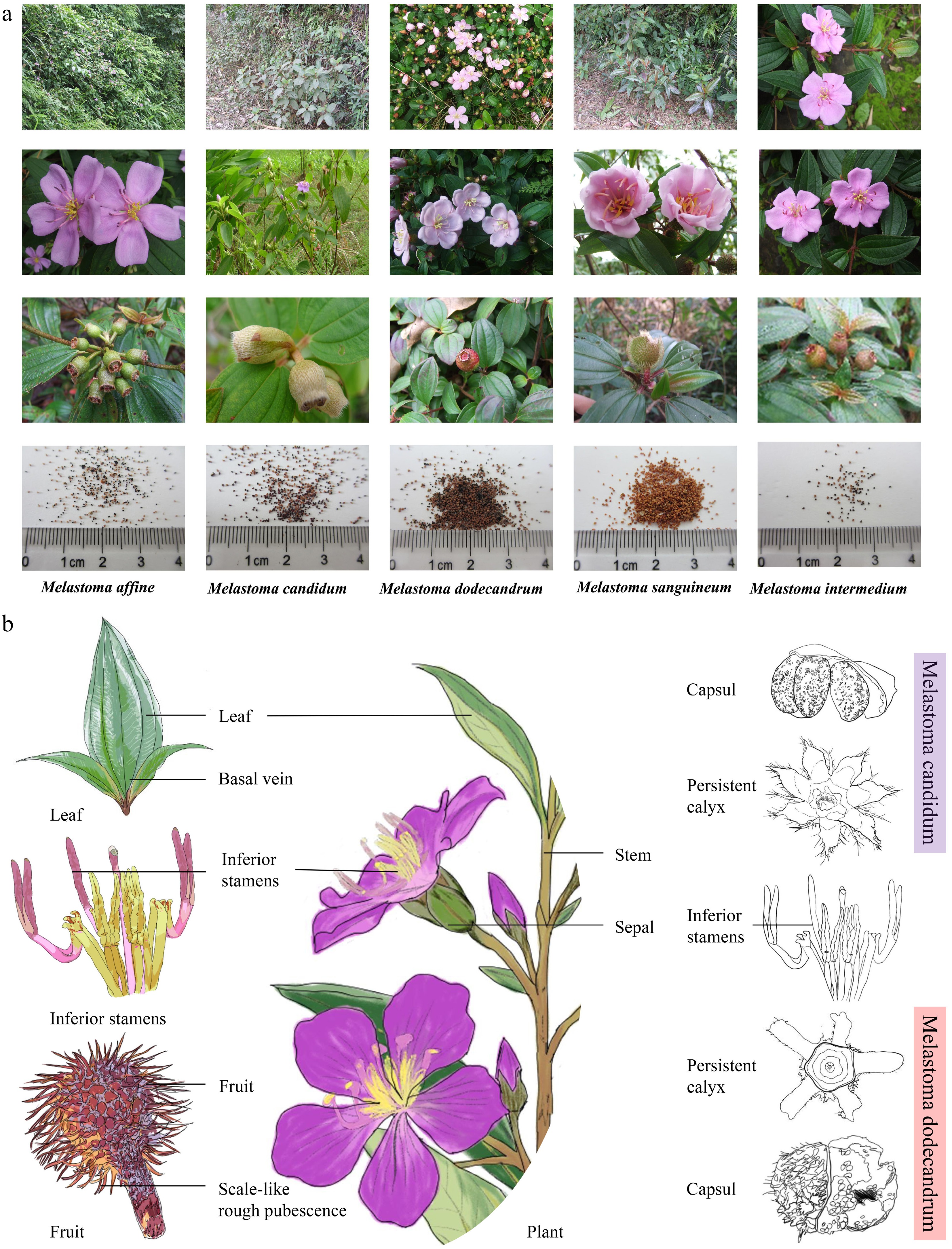

Figure 2.

(a) Characteristic images of five Melastoma species; the seed images were published in the monograph[19]. (b) Schematic diagram of plant structure of Melastoma represented by Melastoma dodecandrum and Melastoma candidum, including leaves, flowers, and fruits.

For a long time, there have been significant disagreements in the classification of the Melastoma genus in China. To clarify the relationships among species, Chinese researchers conducted scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations of the leaf surface morphology of six Melastoma species and performed cluster analysis on these characteristics. The results showed that, except for the upper surface of the leaves of M. dodecandrum, the upper and lower surfaces of the leaves of the other five species were covered with epidermal hairs. Both M. candidum and M. malabathricum had conical and scale-shaped surface hairs on the mid-vein of the lower surface, with M. candidum having long conical hairs and M. malabathricum having short conical hairs. The surface hairs on the mid-vein of both M. intermedium and M. dodecandrum were conical, but the base of the hairs in M. intermedium extended backward, while in M. sanguineum, it did not. The epidermal hairs on the mid-vein of M. normale were long and scale-like. Cluster analysis revealed that M. intermedium, M. normale, and M. malabathricum were closely related and grouped together, while M. candidum, M. sanguineum, and M. dodecandrum formed another, more distantly related group. Based on flowering period observations, it was inferred that M. candidum and M. malabathricum are two distinct species. These findings suggest that leaf surface characteristics can serve as a reliable basis for the classification and identification of Melastoma species[16−18].

-

The genus Melastoma exhibits remarkable morphological diversity, with most species being shrubs or sub-shrubs that vary greatly in stature, from the low, creeping M. dodecandrum to the tall, upright M. sanguineum. Their leaves are highly variable in shape, ranging from ovate to lanceolate or elliptical. Leaf margins may be smooth and satin-like or serrated with ciliate edges, while some surfaces are densely covered with strigose hairs, imparting a distinctive texture. Leaf coloration also ranges widely, from vivid emerald green to purplish red, and even within the same individual, color can shift with light intensity and developmental stage[18,19]. Morphological variation is especially pronounced in the flowers of Melastoma, reflecting close associations with pollination strategies, reproductive functions, and ecological adaptations. Research on floral traits largely focused on the interplay between phenotype and function, including the co-evolution of floral morphology with pollinators[20], and the ecological significance of floral symmetry in tropical environments[21]. Here, the evolutionary importance and adaptive functions of stamen heteromorphism are the focus.

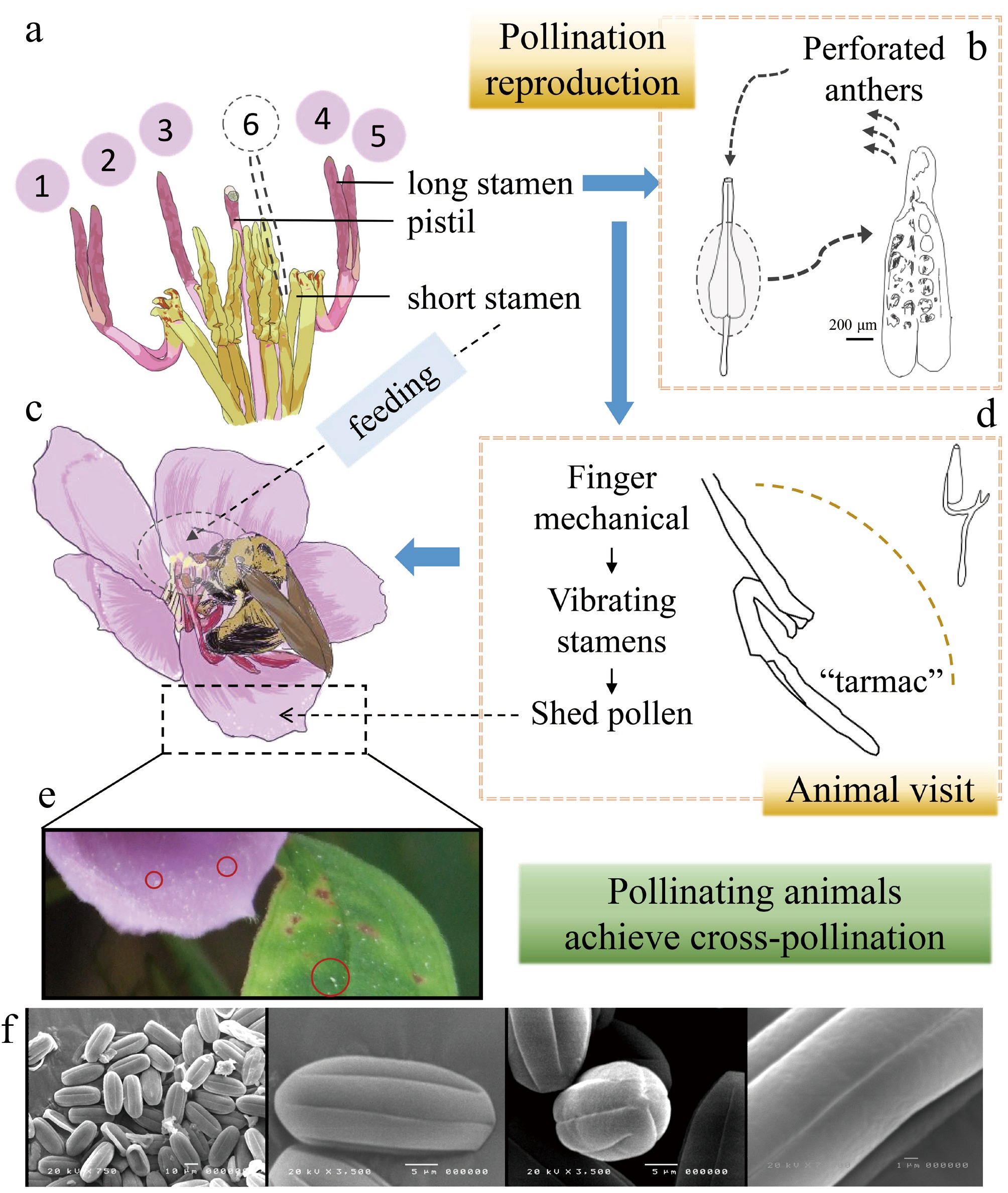

Stamen diversity and functional differentiation are characteristic features of Melastomataceae. They exhibit extensive variation in size, shape, color, dehiscence mode, and accessory structures[22]. Among these traits, heteranthery provides a solution to the 'pollen dilemma' through a division of labor: pollen must function both as a nutritional reward for pollinators and as the plant's gametes to ensure reproduction[23−25]. In Melastoma, stamens are typically dimorphic, consisting of long and short stamens. Pollens from long stamens primarily serve a reproductive role, adhering to 'safe sites on pollinators' bodies where it is less likely to be groomed off. In contrast, pollen from short stamens primarily serves as a food reward, and flowers of Melastoma are frequently visited by carpenter bees (Xylocopa)[26]. Similarly, in Macairea radula, heteromorphic stamens are preferentially visited by Centris aenea[27]. This division of labor is achieved through the alignment of stamen length with pollinator body size and the adjustment of style length to match pollinator morphology. The long stamens extend beyond the bee's abdomen, depositing pollens on their dorsum, a region that is difficult for the bee to groom, whereas the short stamens contact the ventral abdomen, where pollen can be easily collected and utilized (Fig. 3). In some species, stamen coloration further reinforces this division of function. Short stamens are often bright yellow, which attracts pollinators to forage on them first, while long stamens typically resemble the petal color or background, thereby reducing disturbance and ensuring effective transfer of reproductive pollen[19,25,28,29]. Pollen release in Melastoma is closely linked to pollination strategy. Most species possess poricidal anthers, which release pollen only through apical pores when vibrated by pollinators. This dehiscence mode regulates pollen dispensing, prevents wastage, and excludes non-vibrating visitors, ensuring efficient transfer. For example, the anthers of Rhynchanthera grandiflora possess rostrate appendages that guide directional pollen release during vibration, thereby enhancing pollen deposition on pollinators[24]. In a few species, the anthers are polythecous, with septa dividing them into multiple thecae. This condition may alter the timing of pollen release and allow adaptation to a wider diversity of pollinators[21,30,31]. Stamen appendages, including connective extensions, glands, and trichomes, also play important roles in functional adaptation. In some species, extended connectives or dorsal appendages serve as 'mechanical grips' for pollinators, stabilizing anther vibrations and enhancing pollen release efficiency. The reproductive system has co-evolved with floral morphology. Most species rely on pollinators to achieve out-crossing, but some exhibit partial self-compatibility. This mechanism ensures reproductive assurance under pollinator scarcity while balancing reproductive efficiency and genetic diversity[32]. For example, M. candidum possesses typical heteromorphic stamens and is strictly entomophilous. Its breeding system is predominantly out-crossing with partial self-compatibility. However, reproduction still depends on pollinators, and its relative reproductive success is very low, indicating significant limitations in the process of sexual reproduction[24,33].

Figure 3.

Characteristics of heteromorphic stamens of Melastoma candidum and their co-evolution with pollinating animals. (a) Characteristics of heterosexual stamens. (b) The process of pollen release from long stamens. (c) The synergy between the heteromorphic stamen structure and the feeding behavior of Xylocopa aeratus. (d) The structure of long stamens. (e) After the Xylocopa aeratus feed, their pollen scatters on the flowers and leaves. (f) Electron microscope scanning image of M. candidum pollen[19].

Morphological variation in Melastoma, particularly in floral traits, represents fine-scale adaptations to the pollination environment. Through strategies such as functional division of labor, visual signaling, and mechanical matching, these plants optimize pollen utilization and reproductive success. This makes them a typical example of co-evolution between plants and their pollinators.

-

Advances in horticultural techniques have enabled the introduction and domestication of wild Melastoma species, leading to the development of artificial cultivars[34−36]. Selective breeding and hybridization are the main strategies for resource utilization and cultivar innovation. Several ornamental cultivars have been successfully developed, including Melastoma 'Tianjiao', 'Xinyuan', 'Zishan', and 'Hongfei'[37,38]. Melastoma 'Tianjiao' was bred by crossing female M. candidum with male M. sanguineum. It has a compact form with dense branches and bears abundant light purple flowers, blooming from June to October and fruiting from June to November. Melastoma 'Xinyuan', developed from a cross between female M. sanguineum, and male M. intermedium, bears fuchsia flowers with petaloid stamens coiled into inner petal rings, flowering from June to August and fruiting from July to October. Both cultivars thrive in warm, humid climates with full sun and prefer acidic loam or sandy loam[37]. Melastoma 'Zishan' was bred by crossing female M. ultramaficum from Malaysia with male M. penicillatum from China. It has a compact habit with glossy dark green leaves and flowers nearly year-round, peaking from April to September. The cultivar is vigorous, low-maintenance, and slightly tolerant of weakly alkaline soils. Melastoma 'Hongfei', obtained from a cross between female M. penicillatum and male M. normale, shows an open crown, bright red flowers, and red-glossed young leaves, flowering from April to May under warm, humid, sunny conditions[38]. All four cultivars are suitable for tropical and subtropical regions and are commonly propagated through tissue culture or stem cuttings. Pruning after flowering and fruiting improves branching and canopy shaping, while careful water management enhances growth performance.

Native Chinese Melastoma species such as M. candidum, M. normale, M. affine, and M. sanguineum are predominantly propagated by seeds. In contrast, artificial cultivars are mainly propagated by stem cuttings or tissue culture[16,39,40]. For cutting propagation, healthy, pest-free semi-lignified or tender shoots about four to six centimeters long are preferred. Half of the two upper leaflets are retained, with the upper cut made flat and the lower cut oblique. Cutting should be completed on the same day. After planting, maintain 65%–70% shading, 70%–85% relative humidity, and a temperature of 24–35 °C. Water twice daily (morning and evening) to sustain moisture, and disinfect with 0.1% carbendazim every 7–10 d while removing diseased branches and fallen leaves[34]. Peat soil is considered an ideal substrate, or alternatively, a 1:1 mixture of peat and perlite disinfected with carbendazim. Exogenous rooting treatments significantly improve success rates. Soaking cuttings in 500 mg/L IBA, NAA, or ABT rooting regulators for 15 min enhances rooting efficiency. Optimal conditions for M. sanguineum cuttings include a substrate of yellow soil : sand (1:2), pretreatment with 5 mg/L NAA, and exposure to a blue : red light ratio of 2:1 during rooting[41].

-

Aluminum (Al3+) hyper-accumulation has been reported in approximately 45 plant families, most of which are tropical or subtropical woody taxa, including Melastomataceae and Symplocaceae. Within Melastomataceae, species of the genus Melastoma represent an important group of Al hyper-accumulators[42,43]. Among them, M. malabathricum is a representative Al3+ hyper-accumulating species that thrives in tropical acidic soils, where root mucilage plays a specific role in Al uptake[44]. Under Al-deficient conditions, the concentrations of water-soluble calcium, magnesium, and oxalate in the plant decline significantly, indicating that Al3+ acquisition mechanisms are essential for sustaining normal growth[45]. Moreover, hydroponic experiments have shown that the application of Al3+ promotes the growth of M. malabathricum, possibly by alleviating Fe toxicity or maintaining organic acid metabolic balance[45]. These findings highlight the unique dependence of Melastoma species on Al in strongly acidic environments and reveal their specialized physiological mechanisms for Al3+ hyper-accumulation.

In addition to adaptation to acidic soils, Melastoma species exhibit ecological potential for remediation under polluted or stressful environments. Experiments on six Melastoma species under cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) stress demonstrated that with increasing metal concentrations, seed germination rates and root growth were progressively inhibited. However, M. malabathricum, M. candidum, and the cultivar Melastoma 'Tianjiao' exhibited stronger Cd and Pb tolerance, suggesting their potential as pioneer species for the remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soils[46−48]. Similarly, salt stress experiments on six Melastoma species revealed significant inter-specific differences in morphological and physiological responses, with M. malabathricum displaying the strongest salt tolerance, thereby demonstrating its suitability for cultivation in coastal regions or saline–alkali soils[47]. Collectively, these studies indicate that Melastoma species not only rely on Al3+ to promote growth in acidic soils but also possess resilience to heavy metal and salt stress, underscoring their potential applications in soil improvement and ecological restoration of degraded environments.

-

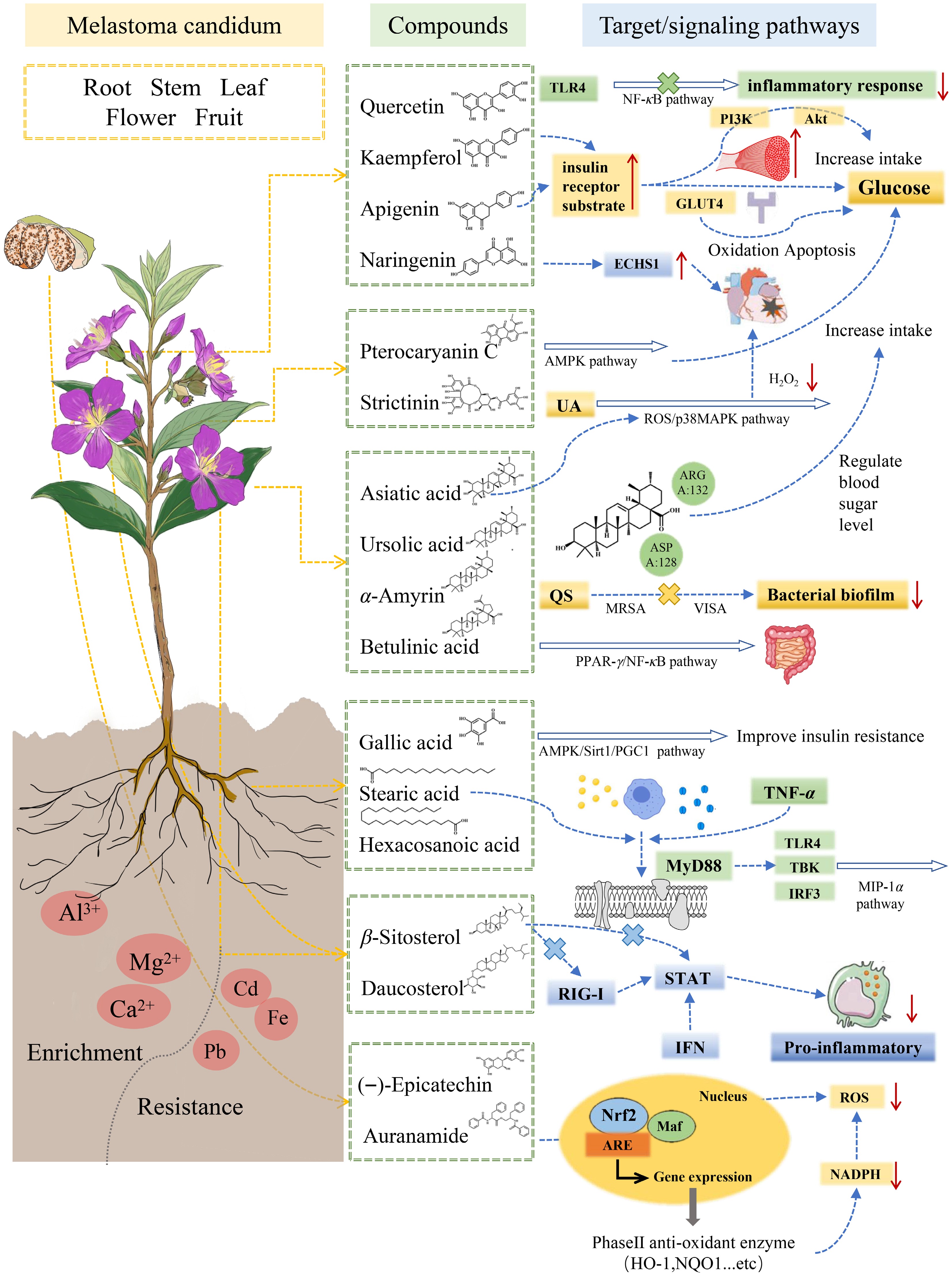

Plants of the genus Melastoma (Melastomataceae) possess diverse pharmacological activities attributable to their rich repertoire of bio-active compounds, including flavonoids, tannins, phenolic acids, and triterpenoids. M. malabathricum is particularly notable for its anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anti-tumor properties, which are primarily mediated by quercetin, ursolic acid, and related constituents. Traditionally, it has been employed in Southeast Asia to treat diarrhea, wound infections, and postpartum inflammation[4, 49,50]. Melastoma dodecandrum, widely used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and ethnic medicine, exhibits a broad spectrum of therapeutic effects. Its flavonoids and polysaccharides confer anti-inflammatory activity by suppressing mediators such as nitric oxide (NO) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and anti-diabetic effects through modulation of the PI3K/Akt and AMPK signaling pathways, improving insulin sensitivity. Additionally, M. dodecandrum demonstrates lipid-lowering, hepatoprotective, hemostatic, and wound-healing activities, partly mediated by luteolin and xanthylium pyran derivative, which also contribute to its anticoagulant and antioxidant effects[51,52]. These multi-component, multi-target properties underpin its clinical relevance in treating postpartum hemorrhage, gastric ulcers, and snakebites[53]. Other species, including M. affine, M. normale, and M. sanguineum, display complementary pharmacological profiles. M. affine, rich in gallic acid, primarily exerts antibacterial and hemostatic effects, supporting its use in wound repair[54,55]. The roots and whole plant of M. normale are rich in polyphenols and tannins (including ellagitannins) and have shown notable anti-inflammatory activity in vitro. These compounds, together with the general antioxidant effects of flavonoids and tannins, theoretically support cardiovascular protective effects. Traditionally, plants of the genus Melastoma have been used to treat dysentery, diarrhea, bleeding, and traumatic hemorrhage, which may be related to their hemostatic and anti-inflammatory actions; however, specific in vivo evidence for the hemostatic or cardiovascular protective mechanisms of M. normale is still lacking[56,57]. Seeds of M. saigonense, which are rich in phenolic acids (e.g., gallic and caffeic acids) and flavonoids, exhibit pronounced in vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, underscoring their potential hypoglycemic properties. Nevertheless, direct evidence for the inhibition of advanced glycation end-product formation or the stimulation of bile secretion by M. saigonense, as well as for analogous effects of M. sanguineum attributed to afzeloside, has yet to be substantiated[58] (Fig. 4, Table 1) .

Figure 4.

Medicinal components of the tissues and organs of plants of Melastoma and their functional signaling pathways.

Table 1. Types, representative compounds, and mechanisms of action of bioactive compounds in the genus Melastoma.

Types Representative compounds Chemical structural Target/signaling pathway Mechanism of action Species Ref. formula Flavonoids Quercetin

The nf-kappa B Inhibition of the NF-κB pathway reduces TNF-α expression in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells M. candidum

M. dodecandrum

M. malabathricum

M. normale

M. villosum[53, 59−62] Kaempferol

PI3K/Akt/GLUT4 Up-regulate the gene and protein expression of PI3K, Akt, and GLUT4 in skeletal muscle, promote glucose transport and utilization, and reduce blood glucose M. candidum

M. dodecandrum

M. malabathricum

M. normale

M. villosum[55, 62,63] Naringenin

ECHS1–PPARα/AMPK Reduces doxorubicin-induced myocardial oxidative stress and apoptosis by upregulating ECHS1 protein M. malabathricum [64,65] Apigenin

PI3K/Akt/GLUT4 Up-regulated the expression of GLUT4 and improved glucose consumption and glycogen synthesis in IR-HepG2 cells. Slightly increased expression of PI3K and p-Akt M. candidum

M. dodecandrum

M. candidum[63, 66] Tannins Strictinin

ROS/p38MAPK Provide hydrogen atoms to remove ROS and reduce oxidative stress; UA regulates the p38MAPK pathway and inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis M. malabathricum

M. dodecandrum

M. normale[67−69] Terpenoids Asiatic acid

MAPK/STAT3 Activation of ERK and p38 MAPK pathways induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells; Inhibition of STAT3 and Claudin-1 M. dodecandrum [65, 70] Ursolic acid

AMPK /PPARα Hypoglycemic mechanisms M. malabathricum

M. dodecandrum

M. intermedium[61, 71] Betulinic acid

PPAR-γ/NF-κB Improvement of intestinal inflammation through the PPAR-γ/NF-κB pathway M. malabathricum

M. dodecandrum

M. intermedium[68, 72] Organic acids Gallic acid

AMPK/Sirt1/PGC1 Promotes mitochondrial function and improves insulin resistance M. candidum

M. intermedium

M. malabathricum

M. polyanthum

M. normale

M. affine[73,74] Stearic acid

TLR4/TBK/IRF3 Enhance MIP-1α expression and promote inflammatory response; Activates the lactate-HIF1α pathway at high concentrations, upregulating VEGF and pro-inflammatory cytokines M. dodecandrum [62, 75] Others (-)-Epicatechin

Nrf2 Promote the expression of antioxidant enzymes (HO-1, NQO1), inhibit NADPH oxidase activity, and reduce ROS production M. dodecandrum [65, 73] Auranamide

NF-κB/Nrf2 Provide hydrogen atoms to remove ROS and reduce oxidative stress; UA regulates the p38MAPK pathway and inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis M. malabathricum [75] Collectively, these findings indicate that Melastoma species represent a rich source of bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, and tannins, which exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities. Some species have also demonstrated hepatoprotective and hypoglycemic effects in limited in vivo or in vitro studies, suggesting their potential for the development of natural therapeutics.

-

The nuclear genome of Melastoma underpins its morphogenesis, physiological adaptation, and ecological traits, providing essential information for functional studies and resource utilization[76]. Chromosome-level reference genomes for M. dodecandrum and M. candidum have been generated using PacBio long-read sequencing combined with Hi-C technology, enabling investigations into evolutionary mechanisms and functional associations within the genus (Table 2).

Table 2. The nuclear genome of Melastoma candidum and Melastoma dodecandrum.

Species Genome size

(Mb)Anchored

pseudo-chromosomesScaffold/contig N50 (Mb) Repetitive sequence Protein-coding genes Functional annotation (%) ncRNAs M. candidum 256.2 12 20.5 (scaffold) 31.5% 40,938 91.3 1,818 M. dodecandrum 299.81 12 3.00 (contig) 40.9% 35,681 98.98 1,818 (miRNA 105, tRNA 633) The M. candidum genome is 256.2 Mb, with 98.0% of sequences anchored to 12 pseudo-chromosomes, a scaffold N50 of 20.5 Mb, and an LTR Assembly Index (LAI) of 25.5. BUSCO analysis recovered 96.9% of core eukaryotic genes, indicating high assembly completeness. Repetitive sequences constitute 31.5% of the genome, predominantly long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs), including Ty3/Gypsy (11.7%) and Ty1/Copia (7.8%). A total of 40,938 protein-coding genes were predicted, 91.3% of which are functionally annotated, with an average length of 2,387.2 bp and 5.2 exons per gene. Additionally, 1,818 non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) were identified[77].

M. dodecandrum genome spans 299.81 Mb, with a contig N50 of 3.00 Mb, and 90.8% of sequences anchored to 12 pseudo-chromosomes. Repetitive sequences account for 40.9%, with LTR transposons contributing 33.5%, substantially higher than in related species such as Eucalyptus grandis (21.9%) and Punica granatum (18.9%). Gene annotation identified 35,681 protein-coding genes (functional annotation rate: 98.98%) and 1,818 ncRNAs, including 105 microRNAs and 633 tRNAs[76].

Mitochondrial genome

-

The mitochondrial genomes of Melastoma species exhibit a circular structure, ranging in size from 391,595 bp in M. candidum to 411,944 bp in M. dodecandrum, with GC contents of approximately 44.2%–44.4%. They contain a relatively low proportion of repetitive sequences (3.52%–3.81%), which are predominantly short repeats of 30–34 bp, while long repeats (more than 100 bp) rarely undergo recombination. This feature is similar to that observed in Nymphaeaceae but markedly lower than in parasitic plants[5, 78]. Notably, chloroplast-derived DNA insertions, also referred to as intra-cellular DNA transfer (IDT) events, have been detected in several Melastoma species, including M. candidum, M. sanguineum, and M. malabathricum. A shared region of approximately 5.1 kilobases contains pseudogenes such as ψrbcL, ψatpB, ψatpE, and ψtrnM-CAU. This region is conserved across species but exhibits nucleotide substitutions and insertions/deletions, suggesting an origin from a common ancestor. Furthermore, in species such as M. penicillatum, nearly intact rbcL and partial atpB sequences were identified, indicating the occurrence of recent IDT duplication events[79] (Table 3).

Table 3. The mitochondrial genome of M. dodecandrum, M. candidum, and M. sanguineum.

Species Genome size

(bp)GC content Structure Repetitive

sequenceM. dodecandrum 411,944 44.18% Circular 3.52% M. candidum 391,595 44.36% Circular 3.52%–3.81% M. sanguineum 395,542 44.37% Circular 3.52%–3.81% IDT events exist in the mitochondrial genomes of eight species, reflecting a common ancestral origin. Chloroplast genome

-

The chloroplast genomes of Melastoma species encode a broad spectrum of genes, including protein-coding genes, transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. Among protein-coding genes, those directly associated with photosynthesis are conserved, such as psbA (encoding the D1 protein of photosystem II), psaA (photosystem I reaction center), and rbcL (the Rubisco large subunit). Genes essential for chloroplast gene expression are also well represented, including ribosomal protein genes (rpl, rps) and RNA polymerase subunit genes (rpo). In addition, functional genes related to pigment synthesis and lipid metabolism, such as chlB, involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis, are consistently present[80]. Comparative analyses of complete chloroplast genomes across 20 species of the family Melastomataceae revealed a typical quadripartite structure, comprising large single-copy (LSC), small single-copy (SSC), and two inverted repeat (IR) regions. Genome sizes ranged from 153,311 to 157,216 base pairs (bp), with an average of 155,806 bp. Most species harbored 84 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes, and 8 rRNA genes (129 in total, including duplicates). Gene content and arrangement were highly conserved across species in the order Myrtales, although rps16 and rpl2 were identified as pseudogenes in some lineages. The overall GC content averaged 37%, with the highest GC content in the IR regions and the lowest in the SSC regions. Seventeen genes were found to contain introns, and some intergenic spacers and introns have been identified as highly informative phylogenetic markers. Phylogenetic analyses based on complete chloroplast genomes provided strong resolution of relationships within Melastomataceae, underscoring both the evolutionary conservation of chloroplast genomes and their utility for taxonomic and phylogenetic studies[6,81−83] (Table 4). Comparative analyses underscore the structural and functional conservation of Melastomataceae plastomes, while complete chloroplast genome data significantly improve phylogenetic resolution and support, providing a robust genomic resource for evolutionary, taxonomic, and phylogenetic studies[6, 81].

Table 4. The chloroplast genome of melastomataceae.

Species GenBank accession number Plastome length (bp) LSC (bp) SSC (bp) IR (bp) GC content (%) Allomaieta villosa KX826819 156,452 85,914 16,975 26,781 36.9 Bertolonia acuminata KX826820 156,045 85,571 17,011 26,733 37.0 Blakea schlimii KX826821 155,862 85,370 16,998 26,747 37.1 Eriocnema fulva KX826822 155,994 85,431 16,953 26,805 37.0 Graffenrieda moritziana KX826823 155,733 85,341 16,924 26,734 37.0 Henriettea barkeri KX826824 156,527 85,991 17,036 26,750 36.9 Merianthera pulchra KX826825 156,168 85,621 17,001 26,773 37.0 Miconia dodecandra KX826826 157,216 86,609 16,999 26,804 37.0 Nepsera aquatica KX826827 155,110 84,644 17,066 26,700 37.1 Opisthocentra clidemioide KX826828 156,352 85,866 16,942 26,772 37.0 Pterogastra divaricata KX826829 154,948 84,718 17,156 26,537 37.2 Rhexia virginica KX826830 154,635 84,459 16,924 26,626 37.2 Rhynchanthera bracteata KX826831 155,108 85,093 16,729 26,643 37.0 Salpinga maranoniensi KX826832 153,311 85,128 16,653 25,765 37.4 Tibouchina longifolia KX826833 156,789 86,297 17,124 26,684 37.1 Triolena amazonica KX826834 156,652 86,200 16,970 26,741 36.9 Melastoma candidum KY745894 156,682 86,084 17,094 26,752 37.17 Tigridiopalma magnifica MF663760 155,663 85,161 16,932 26,785 37.11 Melastoma dodecandrum MH748092 156,611 86,014 17,097 26,750 37.1 Scorpiothyrsus erythrotrichus MZ434958 160,731 85,482 17,007 26,780 36.9 -

The remarkable morphological plasticity and ecological adaptability of Melastoma species arise from the interplay of multi-level genomic variations. A central driver of this diversification is the combination of gene functional differentiation and whole-genome duplication (WGD). In M. dodecandrum, transferase genes and plant hormone signaling pathways collectively modulate environmental adaptability, facilitating survival across heterogeneous habitats. Members of the MADS-box gene family exemplify functional diversification: the expansion of AP1-like genes (eight members) underpins floral meristem regulation and floral organ development, while four LAZY1-like genes contribute to the prostrate growth habit through negative regulation of branch angles. At the genomic level, Melastoma shares two ancient WGD events with its sister genus Osbeckia: the relatively recent σ event (Ks: 0.256–0.280) and the older ρ event (Ks: 0.927–1.022). Both events occurred after the γ whole-genome triplication common to core eudicots, providing the substrate for lineage-specific gene family expansion and functional innovation[76].

Transcription factor families further illuminate the links between genomic changes and morphological outcomes. The WOX (WUSCHEL-related homeobox) family in M. dodecandrum comprises 22 members, grouped into three evolutionary clades (ancient, intermediate, and WUS) and nine structural types, all harboring a conserved Homeodomain (Helix-Loop-Helix-Turn-Helix motif). These genes are distributed across ten chromosomes and shaped by 15 pairs of segmental duplications, with no tandem duplications observed. Promoter analyses revealed enrichment of cis-elements responsive to light (e.g., G-box), stress (LTR), and growth (CAT-box). Expression profiles show strong tissue specificity: MedWOX4 is stem-specific expressed, whereas MedWOX13 is broadly expressed across roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Such diversification, reinforced by WGD-driven duplications, indicates that WOX genes play a pivotal role in regulating stem development and the evolution of prostrate growth forms[84].

Organelle genomes also contribute to evolutionary insights by revealing patterns of functional adaptation and phylogenetic placement. In M. dodecandrum and M. candidum, substantial intracellular DNA transfer (IDT) from chloroplast to mitochondria has been detected, including an ~8 kb chloroplast-derived region containing both intact and pseudogenized genes[5,6].

-

The core characteristics of Melastoma species arise from the coordinated action of multiple regulatory layers, encompassing growth and developmental control, secondary metabolite production, trait optimization, and hormone-mediated signaling. Within this framework, transcription factor families such as ARF and WOX form the regulatory backbone of trait specification. In M. dodecandrum, 27 ARF genes orchestrate auxin signaling, with MedARF6C and MedARF7A responding to exogenous auxin to drive organogenesis. More than half of the ARF family shows elevated expression in stems, thereby contributing to the formation of species-specific stem architectures[85]. Complementarily, the 22 WOX family members predominantly regulate meristem activity and stem development: stem-specific MedWOX4 and broadly expressed MedWOX13 collectively maintain meristem function, supporting the prostrate growth habit characteristic of M. dodecandrum[84]. These core regulators operate within hierarchical networks, modulated by upstream factors such as AP2/ERF and bHLH, and their functional capacity is amplified through gene duplication events driven by whole-genome duplications (WGDs). For instance, expansion of MedWOX4 enhances stem developmental regulation, distinguishing prostrate growth from erect forms.

-

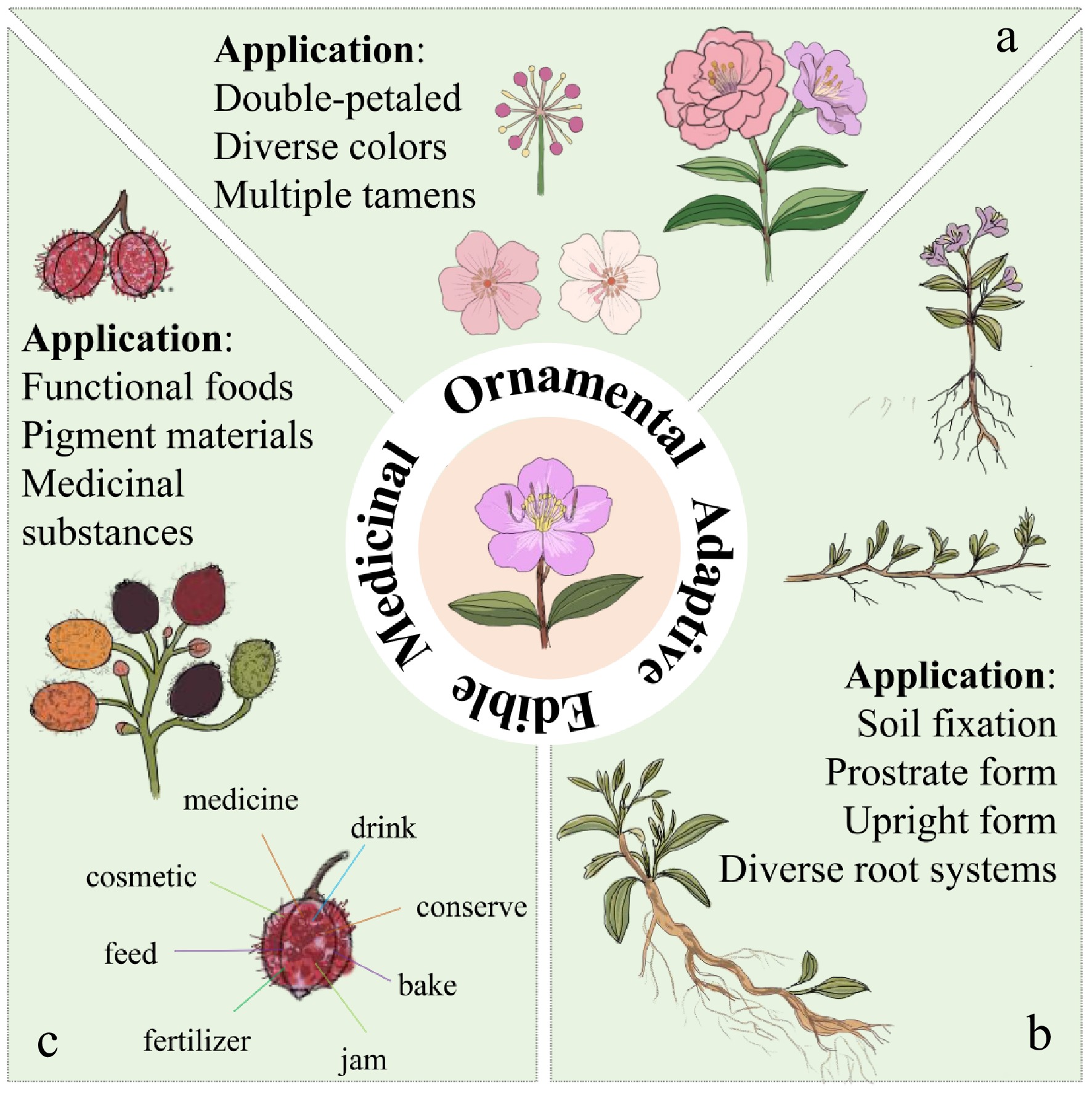

Future research on Melastoma is expected to advance through integrated genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analyses, enabling systematic elucidation of the molecular networks governing stem architecture, flower pigmentation, stamen heteromorphism, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis[86]. High-quality, chromosome-level genome assemblies will facilitate identification of key transcription factors (e.g., ARF, WOX, MYB) and hormone signaling components, providing targets for precise molecular breeding and genome editing, including CRISPR/Cas9-mediated modulation of anthocyanin synthesis and other trait-specific pathways. Concurrently, the ecological resilience of Melastoma manifested in aluminum hyper-accumulation, heavy metal tolerance, and salt stress adaptation (Fig. 5). This supports its potential applications in soil remediation, ecological restoration, and sustainable landscaping[87]. Further phytochemical and pharmacological investigations are needed to characterize bio-active compounds and their multi-target mechanisms, informing the development of medicinally and nutritionally valuable cultivars[88]. Integrating germplasm evaluation, optimized propagation techniques, and standardized cultivation systems will enhance both conservation and commercial utilization. Collectively, these approaches will bridge fundamental research and applied innovation, promoting the rational exploitation of Melastoma species for ecological, ornamental, and therapeutic purposes.

Figure 5.

Breeding directions of Melastoma. (a) In terms of ornamental applications, it includes the double-petal morphology of flowers, the diversity of flower colors, and the multiple stamens of heteromorphic stamens. (b) The aspects of adaptive application include the diversity of root systems and the upright/creeping forms of plants. (c) In terms of food and medicinal applications, it includes functional foods, fruit color, and medicinal substances such as alkaloids rich in fruits.

We would like to thank the editor and reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript. The Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2023J01283, 2022J01639), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 32101583, 31901353), Forestry Bureau Project of Fujian Province of China (2022FKJ12, 2025FKJ04, 2025FTG02).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing, review and editing: Zhao K, Peng D, Zhou Y; data curation, writing−original draft preparation: Tang F, Zhao Y, Zhan S, Huang R; resources: Li X, Peng Y, Su Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The relevant data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Tang F, Zhao Y, Li X, Zhan S, Huang R, et al. 2026. Resource characteristics and genomic advances in Melastoma species: progress and perspectives. Ornamental Plant Research 6: e002 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0046

Resource characteristics and genomic advances in Melastoma species: progress and perspectives

- Received: 30 June 2025

- Revised: 06 September 2025

- Accepted: 30 September 2025

- Published online: 14 January 2026

Abstract: Melastoma species, widely distributed across tropical and subtropical areas, exhibit remarkable morphological diversity and environmental adaptability, with significant horticultural, ecological, and medicinal value in China. Recent genomic and multi-omics advances have made an initial contribution to the molecular bases of key traits, including hetero-morphic stamen regulation, aluminum hyper-accumulation, stress tolerance, and growth habit determination. The application of chromosome-level reference genomes, integrated with metabolomic and transcriptomic, have provided candidate genes and regulatory networks underpinning these traits. However, challenges remain, including limited sequenced species, insufficient functional validation, and the absence of robust breeding systems. Future efforts can focus on pan-genome construction, multi-omics integration, and functional studies to enable targeted molecular breeding, elite germplasm improvement, and sustainable utilization. These advances will facilitate the rational exploitation of Melastoma species for horticultural, medicinal, and ecological applications.

-

Key words:

- Melastomataceae /

- Morphological variation /

- Edible and medicinal functions /

- Genome source /

- Breeding