-

Zoysia spp. are warm-season perennial turfgrass species well adapted for turfgrass across the southern United States and extending into the transition zone. This genus, native to the coastal Pacific Rim[1], comprises 11 species[2], of which only three have economic importance in the turfgrass industry (Zoysia japonica Steud.; Zoysia matrella [L.] Merr.; and Zoysia pacifica [Goudswaard][3] Hotta and Kuroki, previously known as Z. tenuifolia). Zoysiagrass establishes via above-ground stolons and underground rhizomes, creating a dense turfgrass stand that is able to outcompete weeds and has lower input requirements than cool-season turfgrasses. Additionally, zoysiagrass has good tolerance to heat and drought in combination with excellent winter hardiness, which allows it to thrive across a wide variety of environmental conditions[4]. However, when compared to other species, zoysiagrass is slow to establish. Additionally, this species is susceptible to multiple fungal diseases, nematodes, and insects[5]. Furthermore, under severe heat and drought conditions, zoysiagrass can go dormant or die from desiccation[6]. Developing new cultivars with enhanced traits to address these limitations is necessary to strengthen the sustainability and economic gain of the turfgrass industry[7,8].

As is the case for most warm-season turfgrasses, conventional breeding is the main methodology used by breeders to develop new zoysiagrass cultivars[9−12]. Traditional breeding approaches are inherently limited to the use of genetic variability within the species of interest and closely related species[13,14]. Therefore, genetic gains achieved for traits such as stress tolerance and disease resistance through conventional breeding are typically incremental[4,15]. Genetic modification (GM) and gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR-Cas9, have revolutionized plant breeding by enabling the precise introduction of novel genetic variation that is not possible via conventional plant breeding approaches[16,17]. However, successful application of these new breeding approaches usually depends on the availability of effective tissue culture protocols, which provide the necessary framework for plant transformation, selection, and regeneration[18−20].

Limited studies have been conducted on protocol optimization for tissue culture of zoysiagrass. In 1986, in vitro callus induction and plant regeneration from mature caryopses were reported for the first time in zoysiagrass[21,22]. Asano[22] reported early attempts to induce callus from immature leaves and inflorescences, which were characterized as non-embryogenic or necrotic. This research also explored protoplast culture, successfully generating colonies measuring 1–2 mm in diameter. However, these calli did not regenerate into whole plants. Later, Inokuma et al.[23] reported successful regeneration of Z. japonica plantlets from protoplasts. Asano et al.[24] found that the incorporation of cytokinin, thiamine, and α-ketoglutaric acid into the culture medium significantly enhanced the induction of embryogenic callus from seed-derived tissues. Liu et al.[25] indicated that plant regeneration of seed-derived callus occurs via organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis in Z. japonica. Their study assessed the role of Murashige and Skoog (MS) media supplemented with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and kinetin as growth regulators for callus culture. However, their research primarily focused on plant regeneration success rates following long-term callus cultures maintained for 18 months. While these findings provide valuable insights into extended tissue culture protocols, they may not be directly applicable to research applications in which rapid plant regeneration is desired. Consequently, further research is needed to optimize subculturing and regeneration protocols for experiments with shorter timeframes. Wang et al.[26] developed an efficient system for callus induction and plant regeneration by utilizing Z. japonica mature embryos. However, this research included a wide range of 2,4-D and 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) concentrations, and a subculturing medium for callus proliferation was not evaluated. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to assess the effects of varying concentrations of the auxin 2,4-D and the cytokinin 6-BA on both callus induction and its subculture process over time in order to determine the optimal conditions for effective callus formation and successful subculture with the ultimate goal of establishing a highly efficient tissue culture protocol for zoysiagrass using mature seeds as the primary explant.

-

Mature seeds of Z. japonica cultivar 'Zenith'[5] were obtained from Super Sod, a division of Patten Seed Company (Lakeland, GA, USA). Mature seeds of breeding line XZ 14015 were obtained from the Turfgrass Breeding and Genetics Program at North Carolina State University. Seeds were placed in a 50 ml nonsterile centrifuge tube (Cat 21-421 Olympus plastic) and rinsed with running tap water for 5 min, followed by submersion in a 70% (v/v) ethanol solution for 1 min. Seeds were then rinsed twice with sterile water for 2 min under a laminar flow hood (The Barker company, Edgegard 19672. Sanford, Maine 04073 USA). Sodium hypochlorite at 4.5% concentration v/v was added to the tube, and the contents were shaken for 10 min. This was followed by rinsing with sterile water three times for 5 min each. Seeds were then placed on a plate to dry for 10 min under sterile conditions.

Callus induction

-

Dried, sterilized, mature seeds were placed on paper plates and, using a scalpel under a stereoscope (WF 10×/20 mm with block screw VE-S1, VELAB Co., Kingwood, TX, USA) and without removing glumes or embryos, each seed was bisected transversely through the midsection, ensuring that both embryo-containing and endosperm-containing halves were exposed to allow direct contact with the medium. Treatments for callus induction consisted of different combinations of auxin (2,4-D) and cytokinin (6-BA) concentrations (Table 1).

Table 1. Success rate and number of large calli means for 16 MS media treatments supplemented with different 2,4-D and BA concentrations for callus induction from zoysiagrass seeds.

Treatment Hormone concentration (mg·L−1) Callus induction rate (%) LSD

groupNo. of callus larger than

0.5 cm2,4-D 6-BA T1 1.00 0.00 33.3 bcd 3 T2 1.00 0.01 22.2 cd 3 T3 1.00 0.05 33.3 bcd 5 T4 1.00 0.10 11.1 d 2 T5 1.50 0.00 27.8 bcd 5 T6 1.50 0.01 55.6 ab 9 T7 1.50 0.05 66.7 a 7 T8 1.50 0.10 44.4 abc 4 T9 2.00 0.00 16.7 cd 3 T10 2.00 0.01 22.2 cd 4 T11 2.00 0.05 22.2 cd 3 T12 2.00 0.10 22.2 cd 2 T13 3.00 0.00 44.4 abc 6 T14 3.00 0.01 44.4 abc 5 T15 3.00 0.05 44.4 abc 4 T16 3.00 0.10 38.9 abcd 5 * Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different at p = 0.05 according to Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Means in the top group of significance are highlighted in bold. Treatments consisted of a total of 18 seeds, divided in three replications. * mg·L−1 = milligrams per liter. * 2,4-D = 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. * 6-BA = 6-benzylaminopurine. * Number of callus larger than 0.5 cm = Total number in all three repetitions. MS basal medium[27] was prepared using 4.43 g·L−1 of M519 (PhytoTechnology Laboratories, LLCTM. 106th St Lenexa, KS 66215, USA) with 50 g·L−1 sucrose, phytohormone concentration treatment of auxin 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid Solution (2,4-D), cytokinin N6-Benzyladenine; (6-BAP), and gellan gum powder G3251 (PhytoTechnology Laboratories, LLCTM. 106th St Lenexa, KS 66215, USA). For tracking purposes, a different food dye color was added to each auxin treatment and then the pH was adjusted to 5.8. Treatments were autoclaved, and then 1 mg·L−1 of plant preservative mixture PPM (Plant Cell Technology, Washington, DC 20009, USA) was added to the media. Approximately 30 mL of media was poured into 100 mm × 25 mm slippable Petri dishes (sterile polystyrene, non-autoclavable) (D2493, PhytoTechnology Laboratories, LLCTM. 106th St Lenexa, KS 66215, USA). Four different concentrations of 2,4-D (1 mg·L−1 = clear coloring, 1.5 mg·L−1 green coloring, 2 mg·L−1 = yellow coloring, and 3 mg·L−1 blue coloring) were combined with four concentrations of 6-BA for a total of 16 treatments.

For the callus induction experiments, each treatment consisted of a Petri dish containing six different seeds, and treatments were replicated three times. Plastic parafilm was used to seal Petri dishes. Treatments were covered with aluminum foil and stored in dark conditions at 22 ± 2 °C temperatures for 18 d. A Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was conducted to identify differences among the various treatments.

Callus culture

-

To assess the effect of plant growth regulators on callus culture, calli was generated from a single seed of zoysiagrass breeding line XZ 14015. Generated calli were transferred to an MS basal medium supplemented with 1 mg·L−1 2,4-D and cultured under controlled conditions for one week at 21 °C in dark conditions. This stage aimed to stabilize the callus and promote uniform growth before further experimentation. Treatments consisted of four different concentrations of 2,4-D (1, 1.5, 2, and 3) combined with four concentrations of 6-BA (0 mg·L−1 =, 0.01 mg·L−1, 0.05 mg·L−1 =, and 0.1 mg·L−1). Each treatment was composed of seven Petri dishes, with each containing nine cuttings (measuring 2 mm along its largest dimension), serving as an experimental replicate.

Response of callus was assessed based on lateral growth measured 28 and 50 d after transfer. Measurements were collected on the largest dimension of each callus using a digital caliper (model H-7352, Uline company, Pleasant Prairie, WI, USA). To maintain sterile conditions within the Petri dish, callus measurements were taken without opening the lid or removing the parafilm. After measurement, Petri dishes were stored in dark conditions at 22 ± 2 °C until the next measurement. To assess differences among the treatments, a Fisher's Protected LSD test was conducted on the following parameters: callus growth after 28 d, net callus growth after 28 d (calculated as callus growth after 28 d minus the initial callus size of 2 mm), callus growth after 50 d, and net callus growth after 50 d (calculated as callus growth after 50 d minus the initial callus size of 2 mm).

Plant regeneration

-

Seeds of XZ14015 were cultured with induction media containing 2,4-D = 1.5 mg·L−1 + 6-BA = 0.05 mg·L−1, and subcultured in media containing 2,4-D = 2 mg·L−1 + 6-BA = 0.01 mg·L−1 for plant regeneration experiments. Calli from a single seed were transferred to three different regeneration media treatments that consisted of MS basal medium supplemented with 1 mg·L−1 6-BA, 0.2 mg·L−1 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), and 0, 0.1, or 0.5 mg·L−1 of gibberellic acid (GA3). Each treatment included four calli, each with a diameter of 6–8 mm, that were broken into 4–5 smaller subcalli, for a total of 16 subsamples per Petri plate. A total of six repetitions were included in this experiment. Callus exhibiting differentiated shoots developed from somatic embryos was considered regenerated callus. For consistency in data collection and analysis, each piece of callus was recorded as a single regeneration unit, regardless of the number of shoots or somatic embryos present on the callus. This approach ensured uniformity in quantifying regeneration outcomes across samples and treatments, enabling a standardized comparison of regeneration efficiency. For this study, we were interested in the total regenerated plants per treatment. When plantlets were transferred to rooting media, those that naturally separated from the main callus were regarded as individual, distinct plants. Plantlets were transferred to MS basal medium prepared with 4.33 mg·L−1 M524, 25 g·L−1 sucrose, 4 mg·L−1 gellan gum powder (G3251 PhytoTechnology Laboratories, LLCTM, 106th St Lenexa, KS 66215, USA), and pH adjusted to 5.8. About 75 mL of root media was poured into 372 mL magenta vessels (length 75 mm, width 75 mm, and height 98 mm) (PhytoTechnology Laboratories, LLCTM, 106th St, Lenexa, KS 66215, USA). A maximum of five individual plantlets derived from the same media treatment were transferred to each Magenta box for root development. Rooted plantlets were transferred to 50 cells trays (10 in by 20) containing soil (Sun Gro® Horticulture Metro-Mix® [2020]. 830-F3B 2.8 cu ft, 770 Silver Street, Agawam, MA 01001, USA), and trays were placed in the greenhouse for further growth.

-

Across treatments, a total of 288 transversally cut zoysiagrass seeds were placed in culture media for evaluation of callus formation. After four days of inoculation, seed tissues presented swelling around the perimeter, indicating callus formation. A final count of callus formation on seed tissue was conducted 21 d after inoculation. The LSD test identified treatment seven (T7 = 1.5 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.05 mg·L−1 6-BA=) as the most effective treatment for callus induction (67%) in zoysiagrass seed tissue, indicating that an optimal balance of auxin and cytokinin is crucial for promoting effective tissue dedifferentiation. Several other treatments, including T6 (1.5 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.01 mg·L−1 6-BA), T13 (3 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0 mg·L−1 6-BA), T14 (3 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.01 mg·L−1 6-BA), T15 (3 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.05 mg·L−1 6-BA), T8 (1.5 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.1 mg·L−1 6-BA), and T16 (3 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.1 mg·L−1 6-BA=) with a range from 55.6% to 38.9% induction, were not statistically different from T7. This suggests that while a moderate 2,4-D concentration is generally beneficial, some callus induction can still occur at higher auxin concentrations when 6-BA is minimal. Conversely, T4 (1 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.1 mg·L−1 6-BA) exhibited the lowest callus induction (11%), indicating that lower auxin levels may be insufficient for effective induction, particularly when combined with higher cytokinin concentrations. Although the number of explants per treatment used in this study was modest, our design resulted from practical constraints related to seed availability, low germination rates, and contamination risks during large-scale in vitro handling. Despite these limitations, the observed treatment differences were consistent across replications and statistically supported, suggesting that the experimental size was sufficient to detect meaningful biological responses. Future studies using larger populations and additional genotypes could further validate these findings and enhance their broader applicability.

Several turfgrass species, including St. Augustinegrass (Stenotaphrum secundatum [Walt.] Kuntze),[28,29] bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon [L.] Pers.) × Cynodon transvaalensis Burtt Davy[30], creeping bentgrass (Agrostis palustris Huds[31], zoysiagrass (Z. japonica)[32], and Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratenesis L.[33]) exhibited enhanced regeneration rates when exposed to callus induction media containing low concentrations of cytokinins in combination with 2,4-D. Chai et al.[34] studied the application of tissue culture for the long-term maintenance of embryogenic cultures derived from node explants in Z. matrella and observed a clear distinction between embryogenic and non-embryogenic callus. In the present study, embryogenic calli were successfully identified, while the development of non-embryogenic callus was observed to be minimal (less than 5%, data not shown). This could be attributed to the use of seed-derived callus. Seeds typically possess a greater proportion of totipotent or embryogenically capable cells, which can promote the formation of embryogenic callus while reducing the occurrence of non-embryogenic tissue[34,35]. In addition, the unique physiological and biochemical characteristics of seed tissues, combined with their developmental stage, may provide optimal conditions for the induction of embryogenic callus[36].

After 21 d of incubation, treatments T6, T7, T13, and T14 generated a higher number (9, 7, 6, and 5, correspondingly) of large callus (> 0.07 cm) (Table 1). The higher number of large calluses in these treatments could be attributed to an increased rate of cell division and expansion, indicating a potential enhancement in tissue responsiveness. Additional parameters such as callus texture, color, and overall viability should also be considered to assess the quality and developmental stage of the calli formed under these conditions. Chai et al.[32] studied seed-derived zoysiagrass callus and its efficiency for plant regeneration. The authors concluded that the quality and ratio of embryogenic callus vary across different genotypes. However, they also observed that adding high concentrations (10×–500× more than the basal MS) of copper or modifying the culture environment (temperature, light conditions, or pH concentration) can lead to easy identification of embryogenic callus. The findings of the present study, along with results from Chai et al.[32], suggest that the treatments used here selectively promoted embryogenesis while suppressing pathways leading to non-embryogenic tissue formation.

Callus subculture

-

The subculture experiment further emphasized the influence of hormonal concentrations on callus growth dynamics over time. The significant variation observed among treatments highlights the importance of carefully optimizing plant growth regulator concentrations for effective callus proliferation. Fisher's LSD test at a significance level of p = 0.05 revealed differences across treatments for all parameters (Table 2).

Table 2. Callus growth rates 28 and 50 d after inoculation means for 17 MS media treatments supplemented with different 2,4-D and BA concentrations to evaluate zoysiagrass callus subculture.

Treatment Hormone concentration (mg·L−1) Initial

measure

(mm)CGA28D NCGA28D CGA50D NCGA50D 2,4-D 6-BA Mean

(mm)LSD group Mean

(mm)LSD group Mean

(mm)LSD group Mean

(mm)LSD group T1 1.00 0.00 2 4.8 efg 2.8 efg 5.0 bcde 2.2 cd T2 1.00 0.01 2 4.7 fgh 2.7 fgh 3.9 i 1.2 ef T3 1.00 0.05 2 5.2 cde 3.2 cde 4.0 hi 0.8 f T4 1.00 0.10 2 5.6 abc 3.6 abc 5.0 cdef 1.3 ef T5 1.50 0.00 2 5.4 bcd 3.4 bcd 5.3 abcd 1.9 de T6 1.50 0.01 2 5.6 abc 3.6 abc 4.2 ghi 0.6 f T7 1.50 0.05 2 5.2 cde 3.2 cde 4.3 efghi 1.1 ef T8 1.50 0.10 2 5.4 bcd 3.4 bcd 4.6 efghi 1.2 ef T9 2.00 0.00 2 5.8 ab 3.8 ab 5.5 abc 1.7 de T10 2.00 0.01 2 6.0 a 4.0 a 5.8 a 1.8 de T11 2.00 0.05 2 5.1 def 3.1 def 4.0 hi 0.9 f T12 2.00 0.10 2 5.1 def 3.1 def 4.3 fghi 1.2 ef T13 3.00 0.00 2 3.6 j 1.6 j 4.7 defgh 3.1 ab T14 3.00 0.01 2 4.4 ghi 2.4 ghi 5.7 ab 3.3 a T15 3.00 0.05 2 4.3 hi 2.3 hi 4.8 defg 2.5 bcd T16 3.00 0.10 2 4.1 i 2.1 i 4.9 cdef 2.8 abc * Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different at p = 0.05 according to Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Means in the top group of significance are highlighted in bold. A total of 63 calli divided in seven replications. * 2,4-D = 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. * 6-BA = 6-benzylaminopurine. * CGA28D = callus growth after 28 d. * NCGA28D = net callus growth after 28 d minus the initial callus size of 2 mm. * CGA50D = callus growth after 50 d. * NCGA50D = net callus growth after 50 d minus the initial callus size of 2 mm. At 28 d, T10 demonstrated the highest callus proliferation (6.0 mm) and net callus growth (4.0 mm), reinforcing the hypothesis that an intermediate auxin concentration, when paired with minimal cytokinin, supports optimal early-stage callus expansion. A similar performance in callus proliferation (5.8 mm) and net growth (3.8 mm) was observed for T9, suggesting that cytokinin at 0.01 mg·L−1 does not significantly alter early-stage callus development in comparison to auxin alone. In contrast, a higher 2,4-D concentration (3 mg·L−1) without 6-BA resulted in significantly lower callus growth (3.6 mm), indicating potential inhibitory effects of elevated auxin levels at early stages. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that high auxin concentrations may trigger stress responses or disrupt the metabolic balance, ultimately hindering initial cell proliferation[37].

At 50 d, the trends observed in early-stage growth were partially maintained, with T10 remaining one of the most effective treatments for callus proliferation (5.8 mm). However, T14 exhibited comparable callus expansion (5.7 mm), and T9 also showed strong growth (5.6 mm). This suggests that higher auxin levels may enhance late-stage tissue development, possibly by prolonging cell division or delaying differentiation. Net callus growth over time further confirmed this hypothesis. The highest net callus growth between 28 and 50 d (3.3 mm) was observed in T14, followed closely (3.1 mm) by T13. This indicates that the presence of low cytokinin levels does not negatively impact late-stage callus development at high auxin concentrations. However, treatments with increased cytokinin concentrations (e.g., T8, 1.5 mg·L−1 2,4-D + 0.1 mg·L−1 6-BA) exhibited significantly reduced net growth, reinforcing the hypothesis that excessive cytokinin may shift the balance toward differentiation rather than sustained proliferation.

The dynamic interaction between these hormones appears to be stage-dependent, with intermediate auxin concentrations (2 mg·L−1) favoring early-stage growth and higher concentrations (3 mg·L−1) enhancing late-stage proliferation. The minimal cytokinin requirement for sustained callus development suggests that its primary role may be to fine-tune cell division rather than drive initial callus induction. The observed reduction in growth at higher cytokinin levels is consistent with previous findings in other plant species[28,29,32,38−40], which found cytokinin promotes organogenesis and differentiation at the expense of undifferentiated cell proliferation[35,41]. These findings underscore the importance of optimizing hormone ratios to balance sustained callus growth with differentiation potential. To further refine callus induction protocols for Zoysia spp., future studies should explore additional growth regulators such as kinetin or gibberellic acid, which may modulate the observed auxin-cytokinin dynamics. Although the current level of replication was sufficient to detect significant treatment effects, future studies with larger sample sizes and additional genotypes would be valuable to confirm these results and broaden their applicability across diverse zoysiagrass germplasm.

Plant regeneration

-

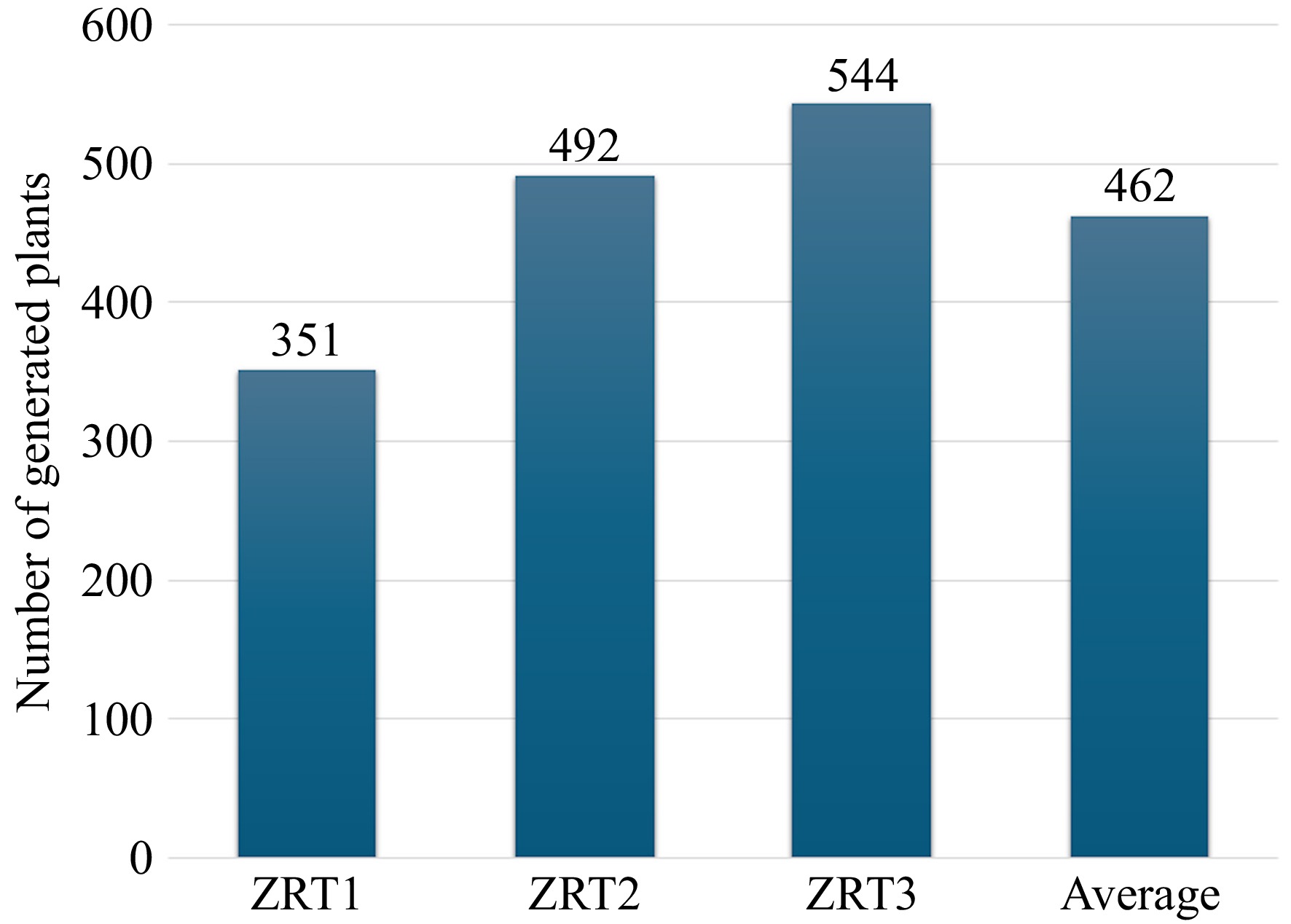

Differences in plantlet formation were observed among the three treatments of MS basal medium supplemented with 1 mg·L−1 6-BA, 0.2 mg·L−1 1-NAA, and varying concentrations of GA3 (Fig. 1). Among the tested treatments, ZRT1, which lacked GA3, exhibited the lowest regeneration efficiency, producing 351 plants with an average of 15 plants per callus. In contrast, the addition of 0.1 mg·L−1 GA3 in ZRT2 resulted in a 40% increase in regeneration, yielding 492 plants and an average of 21 plants per callus. The highest regeneration efficiency was observed in ZRT3, supplemented with 0.5 mg·L−1 GA3, which produced 544 plants with an average of 23 plants per callus, reflecting a 55% increase compared to ZRT1. Furthermore, our findings indicate that GA3 plays a critical role in enhancing organogenesis and shoot elongation, likely by promoting cell division and differentiation. The observed trend suggests that while cytokinin (6-BA) and auxin (1-NAA) contribute to callus initiation and early development, the addition of GA3 is essential for maximizing regeneration efficiency. The increasing trend in plant regeneration with higher GA3 concentrations suggests that fine-tuning hormonal ratios can further optimize shoot induction and plantlet formation.

Figure 1.

Number of zoysiagrass plants regenerated from seed-derived callus at different gibberellic acid (GA3) levels. ZRT1 = 1 mg·L−1 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) + 0.2 mg·L−1 1 naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) + 0 mg·L−1 GA3 ZRT2 = 1 mg·L−1 6-BA + 0.2 mg·L−1 1 NAA + 0.1 mg·L−1 GA3, and ZRT3 = 1 mg·L−1 6-BA + 0.2 mg·L−1 1 NAA + 0.5 mg·L−1 GA3.

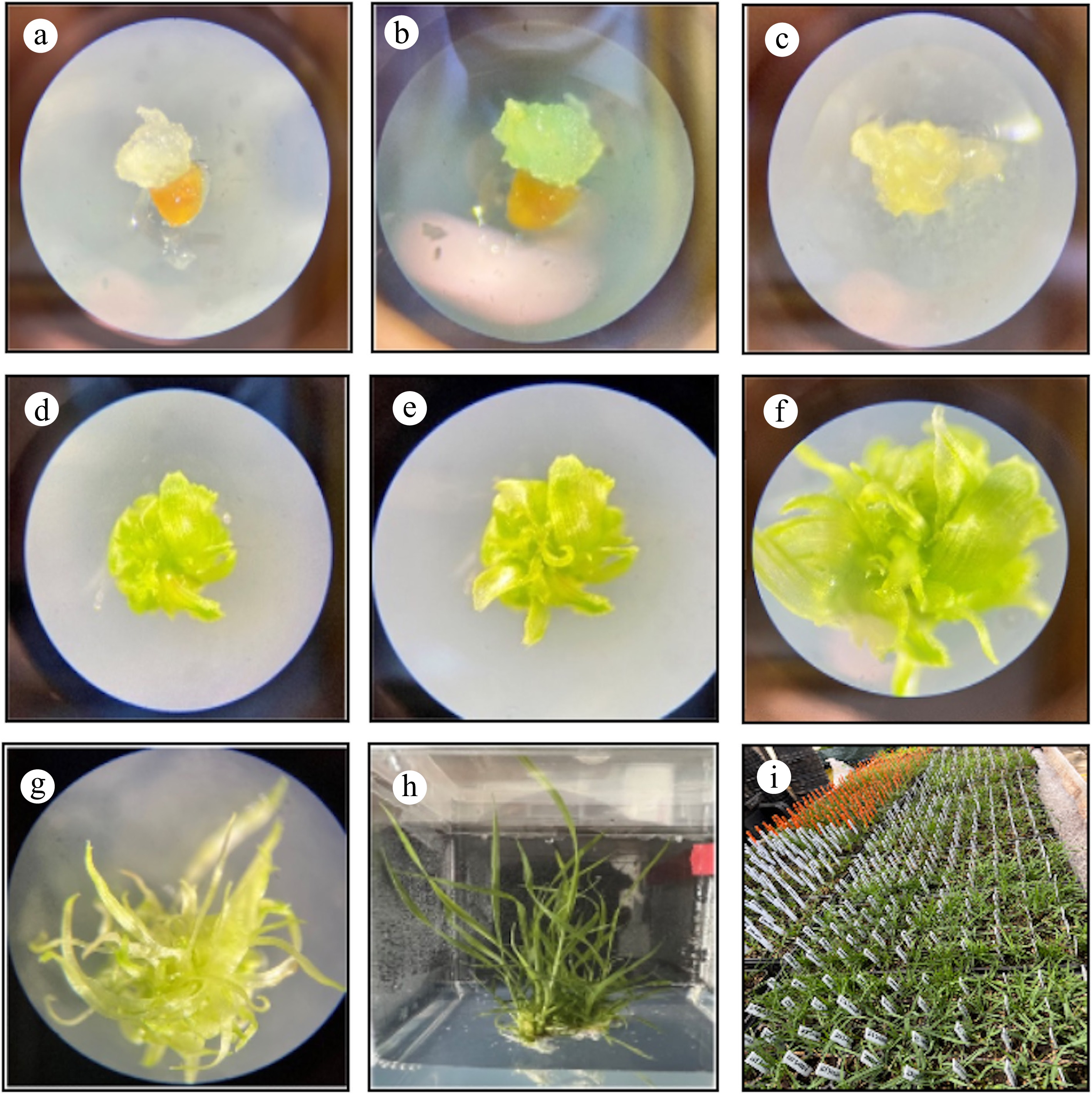

Figure 2 provides a visual timeline for zoysiagrass plant regeneration from seed-derived callus in less than five months. In this study, initial callus formation was observed 14 d after inoculation with plant hormones (T7: 2,4-D at 1.5 mg·L−1 + 6-BA at 0.05 mg·L−1), resulting in compact, embryogenic masses exhibiting a whitish to yellowish appearance. After 20 d, the callus was subcultured onto a medium supplemented with 2 mg·L−1 2,4-D and 0.01 mg·L−1 6-BA to promote further developmental growth. When calli were transferred to a medium containing 1 mg·L−1 6-BA, 0.2 mg·L−1 NAA, and 0.5 mg·L−1 GA3 after 25 d of inoculation, the embryogenic calli gradually developed into organized structures, leading to the formation of shoot primordia. After 10 d in the same medium (30 d post-inoculation), leaf initiation was observed, and by day 25 (50 d post-inoculation), shoot elongation became evident as the callus transitioned from a compact mass to differentiated structures. Following 95 d in plant regeneration media (120 d after inoculation), well-developed plantlets were transferred to a rooting medium, where root proliferation was successfully induced. The rooted plantlets were then acclimated in a growth chamber for 15 d before being transferred to greenhouse conditions for further studies. These findings establish a reproducible and efficient protocol for zoysiagrass propagation, which may have applications in breeding and genetic engineering. Future studies should focus on assessing the morphological quality, genetic stability, and field performance of regenerated plants. Additionally, future work should explore a broader range of genotypes and hormonal interactions to further refine tissue culture protocols for Zoysia spp. breeding programs.

Figure 2.

Developmental stage of zoysiagrass regeneration from seed-derived callus. (a) Initial callus formation 14 d after inoculation (DAI). (b) Callus subculture growth (20 DAI). (c) Callus growth and transference to regeneration media (25 DAI). (d) Appearance of organized structures (30 DAI). (e) Leaf initiation (40 DAI). (f) Leaf growth (50 DAI). (g) Leave elongation (70 DAI). (h) Shoot transference to rooting medium (120 DAI). (i) Transfer into soil and greenhouse acclimation (150 DAI).

Recent findings by Wang et al.[42] demonstrated that Zoysia japonica regeneration after mechanical injury involves extensive transcriptional reprogramming and hormone cross-talk between auxin- and cytokinin-responsive pathways, highlighting their central role in regulating cellular reorganization during organ renewal. Our optimized in vitro protocol complements these molecular insights by providing a reproducible system that mimics these hormone-mediated responses under controlled conditions. The ability to induce callus formation, somatic embryogenesis, and plant regeneration through specific auxin–cytokinin combinations offers a practical framework to investigate and manipulate the same regulatory networks identified in vivo.

In conclusion, these findings indicate that optimizing plant growth regulator combinations is essential for enhancing callus induction, growth, and regeneration. Specifically, moderate auxin levels (1.5–2 mg·L−1 2,4-D) with minimal cytokinin (≤ 0.01 mg·L−1 6-BA) support robust callus formation and expansion, while high GA3 concentrations favor effective regeneration by promoting somatic embryo development. This balance is particularly important in refining protocols for plant species known for poor tissue culture responses, such as zoysiagrass. Additionally, the interplay between auxin and cytokinin concentrations during the subculture phase can influence not only callus size but also their overall regenerative potential, suggesting that precise adjustments at different developmental stages can maximize desirable outcomes. Although this protocol was optimized using specific genotypes ('Zenith'), it provides a robust foundation for tissue culture in zoysiagrass.

This work was supported by the North Carolina State University Center for Turfgrass Environmental Research and Education. An award number is not applicable, and Susana Milla-Lewis is the recipient.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing−original draft, writing−review and editing: Carbajal EM, Milla-Lewis SR; data curation, visualization: Carbajal EM; funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision: Milla-Lewis SR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the inclusion of breeding lines that are not yet patented or protected. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Carbajal EM, Milla-Lewis SR. 2026. Influence of auxin and cytokinin concentrations on callus induction, subculture growth, and somatic embryogenesis for plant regeneration in zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.). Grass Research 6: e001 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0034

Influence of auxin and cytokinin concentrations on callus induction, subculture growth, and somatic embryogenesis for plant regeneration in zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.)

- Received: 09 April 2025

- Revised: 22 November 2025

- Accepted: 26 November 2025

- Published online: 19 January 2026

Abstract: Genetic engineering and gene editing present transformative opportunities for turfgrass improvement by permitting the introduction of genetic variation that does not naturally exist within a species. However, the successful application of these approaches depends on the generation of efficient and reproducible tissue culture protocols. Optimizing these methodologies for warm-season turfgrass species is essential to ensure the scalability and reliability of genetic modification efforts. In this study, parameters affecting the efficiency of callus formation, growth, and somatic embryogenesis were studied in zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.). Seeds were evaluated under four auxin and four cytokinin concentrations for callus induction and subculture. The combination of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) = 1.5 mg·L−1 and 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) = 0.05 mg·L−1 was identified as the most effective treatment for callus induction with a 67% success rate. Results demonstrated that a moderate concentration of 2,4-D combined with minimal 6-BA significantly enhanced callus formation and net callus growth over time. Additionally, plant regeneration trials revealed that gibberellic acid (GA3) concentrations influenced somatic embryo development, with high levels yielding the highest regeneration efficiency. A total of 1,387 plants were recovered from 1,536 calli. The optimized protocol described here provides a foundation for potential advancements in zoysiagrass breeding, enabling research on somaclonal variation, plant transformation, and genome-editing tools that will contribute to creating genetically modified turfgrasses with improved agronomic traits.

-

Key words:

- Tissue culture /

- Zoysiagrass /

- Callus /

- Somatic embryogenesis /

- Plant growth regulators