-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are persistent environmental contaminants primarily from anthropogenic activities such as fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes[1]. Among them, benzo[a]pyrene is a prototypical compound, detected in aquatic environments at concentrations typically ranging from ng/L to sub-μg/L, and up to mg/L at extreme pollution scenarios[2,3]. Benzo[a]pyrene exerts its toxicity mainly through metabolic activation. As a potent aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, it is converted by cytochrome P450 enzymes into reactive intermediates. This process can lead to DNA adduct formation, mutagenesis, and oxidative stress, magnified as diverse adverse outcomes[4,5].

The toxicological profile of benzo[a]pyrene is extensive, encompassing carcinogenicity, immunotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and notably, profound developmental and reproductive toxicity[3,6,7]. In fish models, waterborne or dietary benzo[a]pyrene exposure causes severe developmental defects, including increased mortality, premature or delayed hatching, growth reduction, cardiac dysfunction, pericardial and yolk sac edema, and craniofacial and spinal deformities[8−14]. Crucially, these effects are not confined to the directly exposed generation. It has been demonstrated that a parental dietary benzo[a]pyrene exposure (10, 114, and 1,012 μg/g food for 21 d) in zebrafish induced prominent body morphology deformities and premature hatching in the F1 generation, with craniofacial defects emerging prominently in the F2 generation, despite these offspring never being directly exposed[10]. Ancestral benzo[a]pyrene exposure (1 μg/L for 21 d) caused bone impairments in larvae and adult male medaka of F1–F3 generations[11−13].

A key target of benzo[a]pyrene toxicity is the skeletal system. Osteotoxicity, manifested as spinal curvature and craniofacial defects, is a well-documented phenotype in fish exposed to benzo[a]pyrene[5]. In medaka (Oryzias latipes), embryonic exposure to benzo[a]pyrene (0.01, 0.1, and 1 mg/L for 2 h with a nanosecond-pulsed electric field) induces teratogenic effects, including cardiovascular abnormalities and a characteristic curvature of the backbone[14]. The molecular underpinnings of this osteotoxicity may involve the dysregulation of genes critical for bone formation. For instance, in marbled rockfish (Sebastiscus marmoratus), embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure (0.05, 0.5, and 5 nmol/L) for 7 d caused skeletal deformities and altered the expression of genes involved in osteogenesis[15]. Transcriptomic analyses in zebrafish further reveal that benzo[a]pyrene exposure disrupts pathways related to extracellular matrix organization and collagen synthesis, essential for skeletal integrity[16]. Furthermore, embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure (0.25, 0.5, 0.6, and 0.8 μmol/L for 72 h) induces severe morphological and skeletal deformities in zebrafish embryos, delays hatching by structurally altering the zebrafish hatching enzyme, and accumulates primarily in the yolk sac[17]. At the molecular level, benzo[a]pyrene exposure triggers oxidative stress, leads to the downregulation of critical bone-related genes (e.g., sox9a, spp1/opn, and col1a1), and induces apoptosis in the head, backbone, and tail regions[17].

While the phenotypic consequences of benzo[a]pyrene exposure are well-characterized, the fundamental metabolic disruptions that drive these multigenerational developmental and osteotoxic effects remain unclear. Transcriptomic studies have provided invaluable insights, identifying dysregulated pathways such as xenobiotic metabolism signaling, NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response, glutathione-mediated detoxification, and arachidonic acid metabolism[13,14,16,18]. These pathways are intrinsically linked to cellular metabolism, which suggests that benzo[a]pyrene induces a profound metabolic reprogramming. However, a comprehensive metabolomic profile that connects these molecular initiations to the phenotypic endpoints across generations is lacking.

Metabolomics, the systematic study of small-molecule metabolites, offers a powerful tool to decipher the functional outcome of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic changes. It can reveal metabolic pathway disruptions—such as in energy metabolism, amino acid synthesis, lipid peroxidation, and antioxidant defense—that are the direct cause of observed toxicity[19,20].

In this study, it is hypothesized that embryonic exposure to benzo[a]pyrene induces persistent metabolomic perturbations that underlie the observed multigenerational developmental toxicity and osteotoxicity in medaka fish. These perturbations likely involve pathways related to oxidative stress, energy metabolism, inflammation, and bone matrix formation. This metabolomic perspective is critical as it moves beyond the transcriptional potential revealed by prior studies to directly identify the functional biochemical dysregulations—the altered metabolic fluxes and effector molecules—that are the proximate cause of phenotypic damage. Using medaka as a model, this study aims to: (1) characterize the multigenerational impacts of embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure on developmental malformations and skeletal integrity; and (2) employ an untargeted metabolomics approach to identify the key metabolic pathways disrupted in directly exposed (F0) and subsequent (F2) generations. By integrating phenotypic data with metabolomic profiles, this study elucidates the mechanistic metabolic links between early-life benzo[a]pyrene exposure and adverse health outcomes that persist across generations, providing a deeper understanding of its long-term ecological risks.

-

Sexually mature medaka (Oryzias latipes, 4 months old) were maintained under conditions approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shantou University (Shantou, China). Embryos were collected within 30 min of the light cycle beginning. Each of 15 pairs of fish was randomly allocated to 10 cube tanks (30 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm; 20-L volume) containing filtered tap water. Stock fish were maintained at optimal conditions (26 ± 0.5 °C, pH 7.3 ± 0.1, 7.2 ± 0.2 mg O2 L−1, and a light : dark cycle of 14:10), and fed Artemia nauplii twice per day[7,21].

Chemical treatment and multigenerational experimental design

-

Collected embryos were rinsed, cleaned, and sorted (stages 8–9) before being distributed into glass Petri dishes (diameter = 7 cm). Each dish contained benzo[a]pyrene exposure solutions (CAS No. 57–63–6; purity ≥ 98%; dissolved in DMSO) at nominal concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 80 μg/L, with 30 embryos per replicate and four replicates per treatment. The solvent control (0.4‰ DMSO) contained no detectable benzo[a]pyrene, while the measured exposure concentrations were 2.2 ± 0.4, 17.0 ± 5.0, and 73.0 ± 10.0 μg/L for the respective treatment groups[7]. Embryos were incubated at 26 ± 0.5 °C, and the exposure solution was renewed daily. Owing to the limited volume of the exposure solution, benzo[a]pyrene concentrations were not ascertained during the 24-h interval before medium renewal.

The embryonic exposure period concluded near the time of hatching at 8 d post fertilization. From day 9 post-fertilization onwards, the benzo[a]pyrene solution was replaced with a clean embryonic culture medium. Upon hatching, the F0 generation larvae were transferred to clean water, and raised to adulthood to produce the F1 and F2 generations[7,12], and 15 pairs of adult medaka were randomly assigned and reared in each replicate tank. For F0–F2 embryos, mortality and hatching rates were recorded twice daily over a 20-d period. However, mortality rates were not recorded over the course of the multigenerational studies. Newly hatched larvae from each generation were observed and imaged using an inverted stereo microscope (Zeiss Stemi 305, Germany). Morphometric analysis was performed on these images using ImageJ software to measure total body length (mm), eye pit area (mm2), yolk sac area (mm2), pericardial cavity area (mm2), and swim bladder area (mm2). A larva was scored positive for a craniofacial deformity if the head morphology was abnormal or the head and trunk were not aligned, for a spinal deformity if the trunk exhibited clear curvature (e.g., lordosis, kyphosis, or scoliosis), and for a fin/tail deformity if the fin structures showed a distinct bend or malformation. To minimize bias, all morphometric and deformity assessments were conducted by the same observer who was blinded to the treatment groups.

Untargeted metabolomics analysis

Sample preparation and metabolite extraction

-

To ensure that the observed metabolic disruptions specifically reflect mechanisms underlying developmental defects such as spinal curvature, rather than acute, nonspecific stress responses or lethality, metabolomic profiling was only conducted on F0 and F2 embryos ancestrally exposed to environmentally relevant, sublethal concentrations of benzo[a]pyrene (2.5 and 20 μg/L). F0 medaka embryos, with or without benzo[a]pyrene exposure, were sampled on day 8 and stored at −20 °C for metabolomics analysis. Medaka embryos (100 embryos × four replicates) were homogenized in 500 μL of 80% methanol (prechilled to −20 °C) using a grinder with steel beads. A small aliquot (20 μL) of the homogenate was retained, dried under vacuum, and redissolved. The protein content of this aliquot was then quantified using a BCA assay, which was used for subsequent normalization of metabolite abundances. The homogenate was incubated at −20 °C for 30 min to precipitate proteins and subsequently centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then recentrifuged for 5 min under the same conditions. The final supernatant was collected for analysis. A quality control (QC) sample was generated by pooling equal aliquots of all sample supernatants.

Liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry

-

Metabolite separation was performed using UPLC, followed by detection on a TripleTOF 6600 mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source operating in both positive and negative ionization modes. Key source parameters included temperature, 500 °C; curtain gas, 30 psi; sheath and auxiliary gas, 60 psi each; and ion spray voltage, ±5,000 V/−4,500 V. Data were acquired in an information-dependent acquisition mode. Each cycle consisted of a high-resolution TOF-MS survey scan (m/z 60–1,200, 150 ms) followed by MS/MS scans on the top 12 most intense ions (m/z 25–1,200, 30 ms/scan), with a 4-s dynamic exclusion.

Data processing and metabolite annotation

-

Raw data files were converted to mzML format and processed using XCMS and MetaboAnnotation toolbox in R for peak picking, alignment, and annotation of adducts and isotopes. Metabolites were annotated by matching accurate mass (with a tolerance of < 10 ppm) against the KEGG and HMDB databases. Putative identifications were further validated by isotopic distribution patterns and comparison to an in-house MS/MS spectral library. A feature intensity matrix was generated for statistical analysis.

Quality control and statistical analysis

-

Data quality was ensured by rigorous preprocessing: metabolic features (with confirmed MS/MS spectra) not detected in > 50% of QC samples or > 80% of biological samples were removed. Missing values were imputed using the k-nearest neighbor algorithm. Signal intensity drift was corrected using the MetNormalizer algorithm on the QC samples. Features with a relative standard deviation > 30% in the QC samples were excluded. Differential analysis was performed using Student's t-tests with FDR adjustment for multiple comparisons, and supervised Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) was employed for group separation. A permutation test was executed 200 times to assess the risk of overfitting for the applied model (Supplementary Figs S1–S10 & Supplementary Table S1). Features with a Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) score > 1.0, p < 0.05 in the Student's t-test, and ratio ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67 were considered as differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs). The DAMs identified in both modes were combined and subjected to KEGG pathway enrichment analysis.

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 10.4. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from four independent replicates (n = 4). Differences between the solvent control and benzo[a]pyrene treatments across F0–F2 generations were assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test (for morphometric data) or a χ2 test (for survival, hatching, and deformity data). Results were considered statistically significant at * p < 0.05.

-

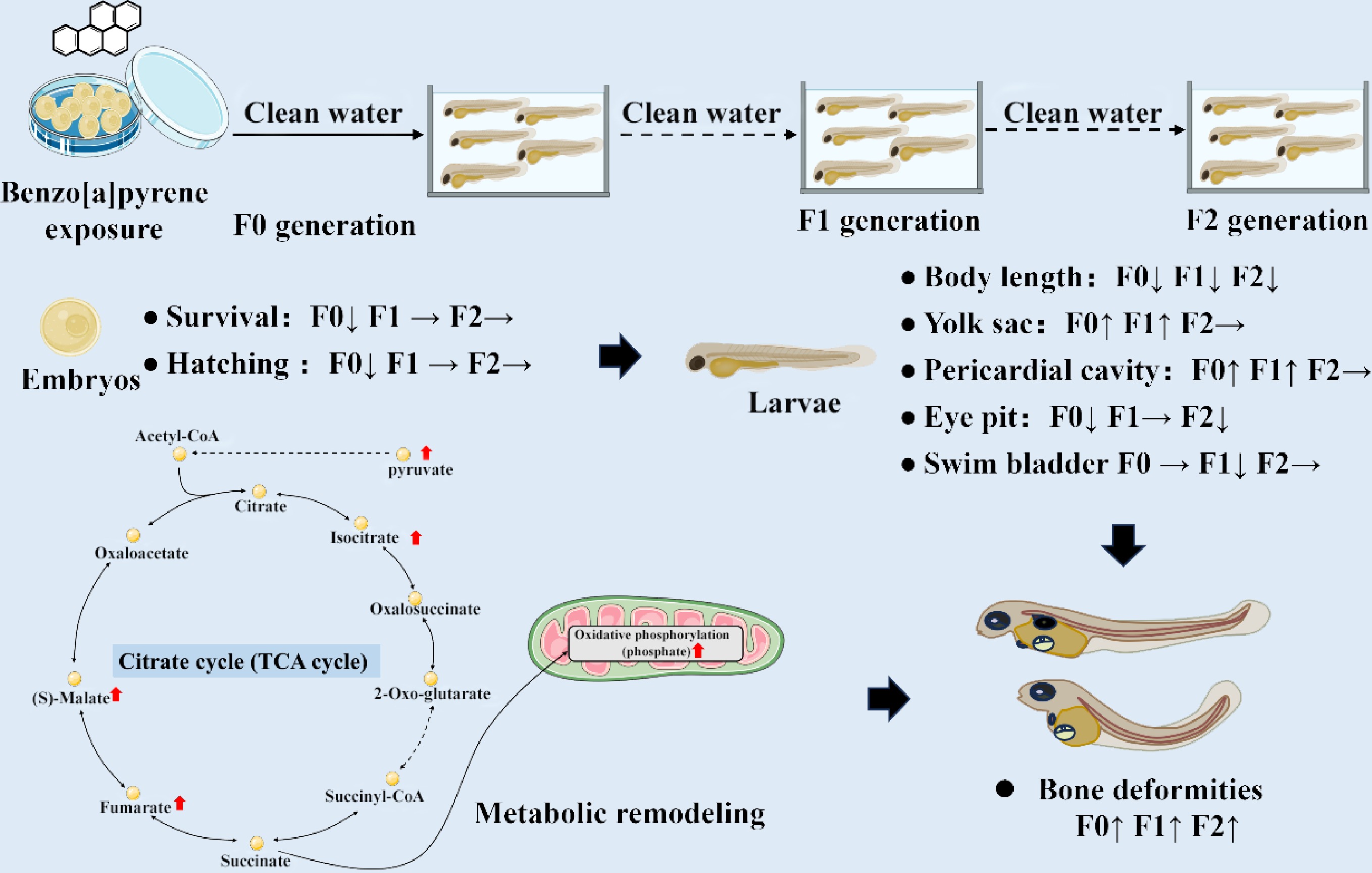

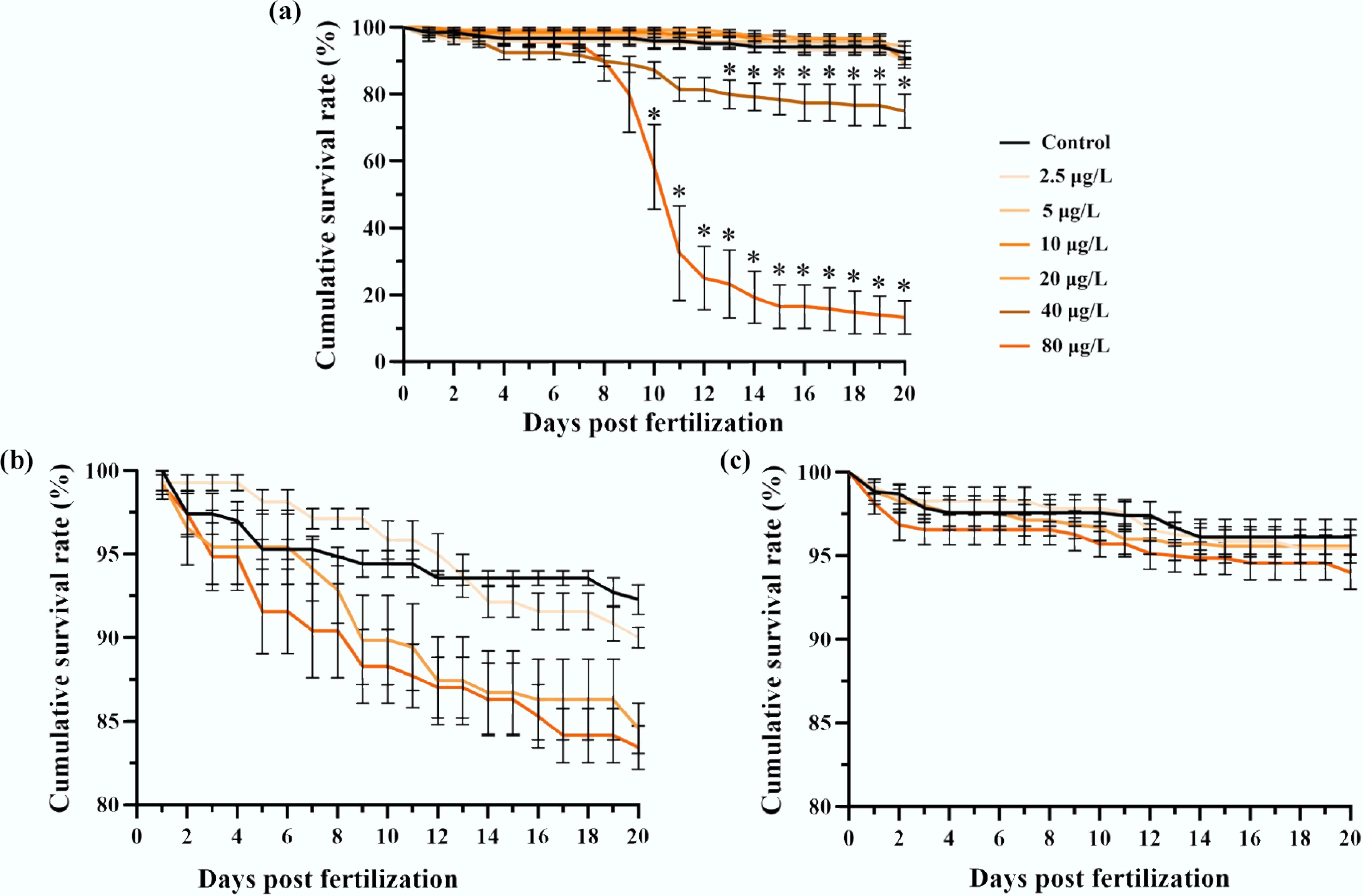

In the F0 generation, benzo[a]pyrene exposure significantly suppressed embryonic development, delayed hatching, and reduced hatching success in medaka. A profound, concentration-dependent increase in mortality was observed, becoming significant from day 10 (80 μg/L) and day 13 (40 μg/L) onward (p < 0.05, χ2 test; Fig. 1a). At 20 dpf, the cumulative survival rate dropped from 92.5% ± 1.8% for the F0 control to 90.0% ± 1.2%, 89.3% ± 1.4%, and 13.3% ± 4.9% for the 2.5, 20, and 80 μg/L treatments, respectively. In contrast, descending F1 and F2 generations from exposed ancestors showed non-significant reduction in survivorship at 2.5, 20, and 80 μg/L concentrations compared to the control (Fig. 1b, c).

Figure 1.

Multigenerational survivorship of medaka embryos affected by F0 embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure. The exposure lasted for 8 d, after which all individuals of F0–F2 generations were reared in clean water. Cumulative survival rates are shown for the (a) F0, (b) F1, and (c) F2 embryos with or without ancestral benzo[a]pyrene exposure (n = 4; data are presented as mean ± SEM). A comparison of the mean values is provided, and * indicates p < 0.05, according to a χ2 test.

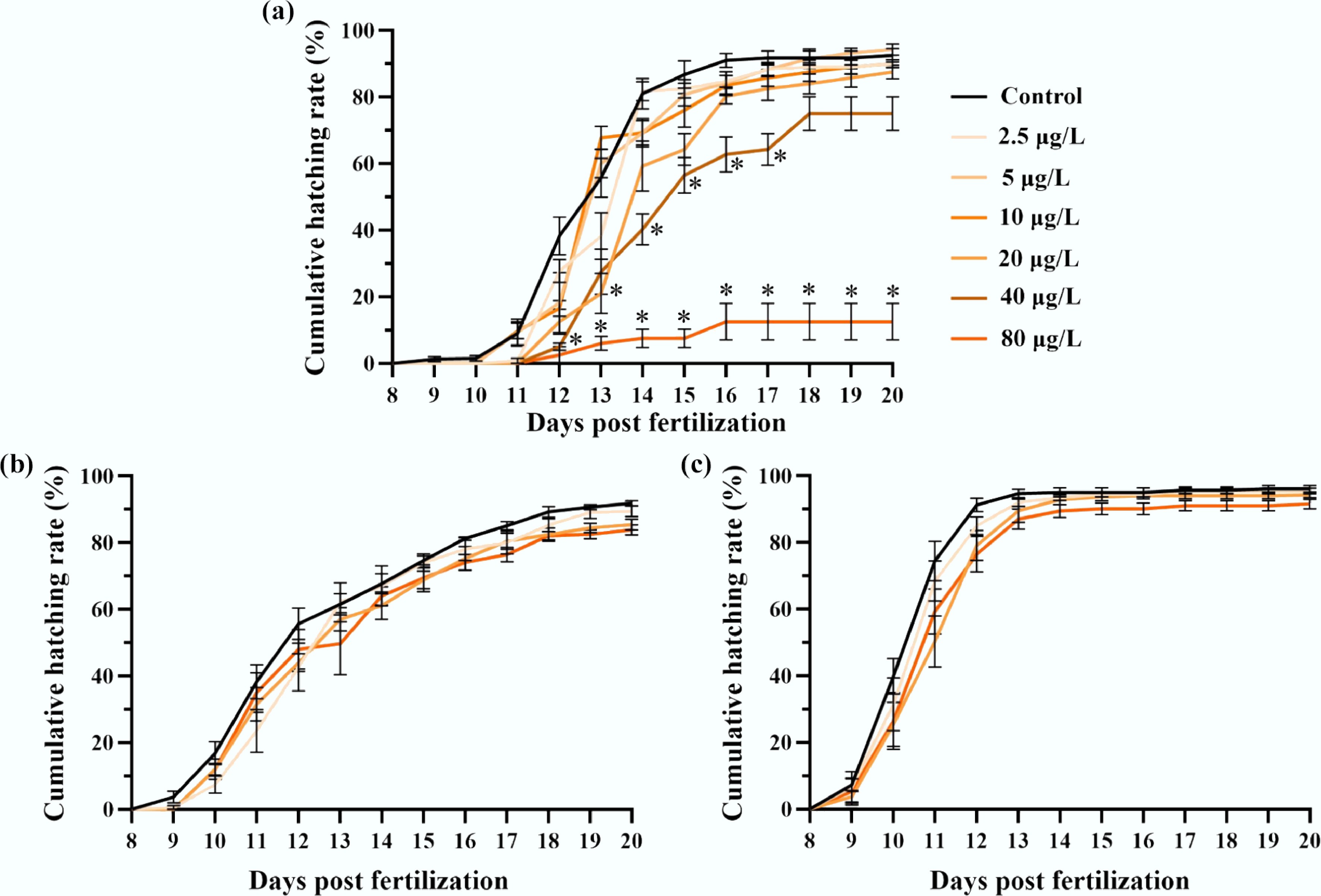

In the F0 generation, benzo[a]pyrene exposure induced a delay in the onset of hatching, with a 2-d delay at concentrations ≤ 10 μg/L, and a 3-d delay at higher concentrations compared to the solvent control (Fig. 2a). At 20 dpf, the cumulative hatching rate decreased from 92.5% ± 2.1% for the F0 control to 90.0% ± 1.2%, 87.5% ± 2.0%, and 12.5% ± 5.5% for the 2.5, 20, and 80 μg/L treatments, respectively. Significant reductions (p < 0.05, χ2 test) in cumulative hatching rates were observed at 40 and 80 μg/L. While a 1-d hatching delay persisted in the F1 generation at 20 and 80 μg/L, the reductions in hatching success were largely recovered (Fig. 2b). In the F2 generation, both hatching timing and success were comparable to the control (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Multigenerational hatching success of medaka embryos affected by F0 embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure. The exposure lasted for 8 d, after which all individuals of F0–F2 generations were reared in clean water. Cumulative hatching rates are presented for the (a) F0, (b) F1, and (c) F2 medaka embryos with or without ancestral benzo[a]pyrene exposure (n = 4; data are presented as mean ± SEM). A comparison of the mean values is provided, * indicates p < 0.05, according to a χ2 test.

Developmental toxicity and osteotoxicity in F0–F2 medaka larvae

-

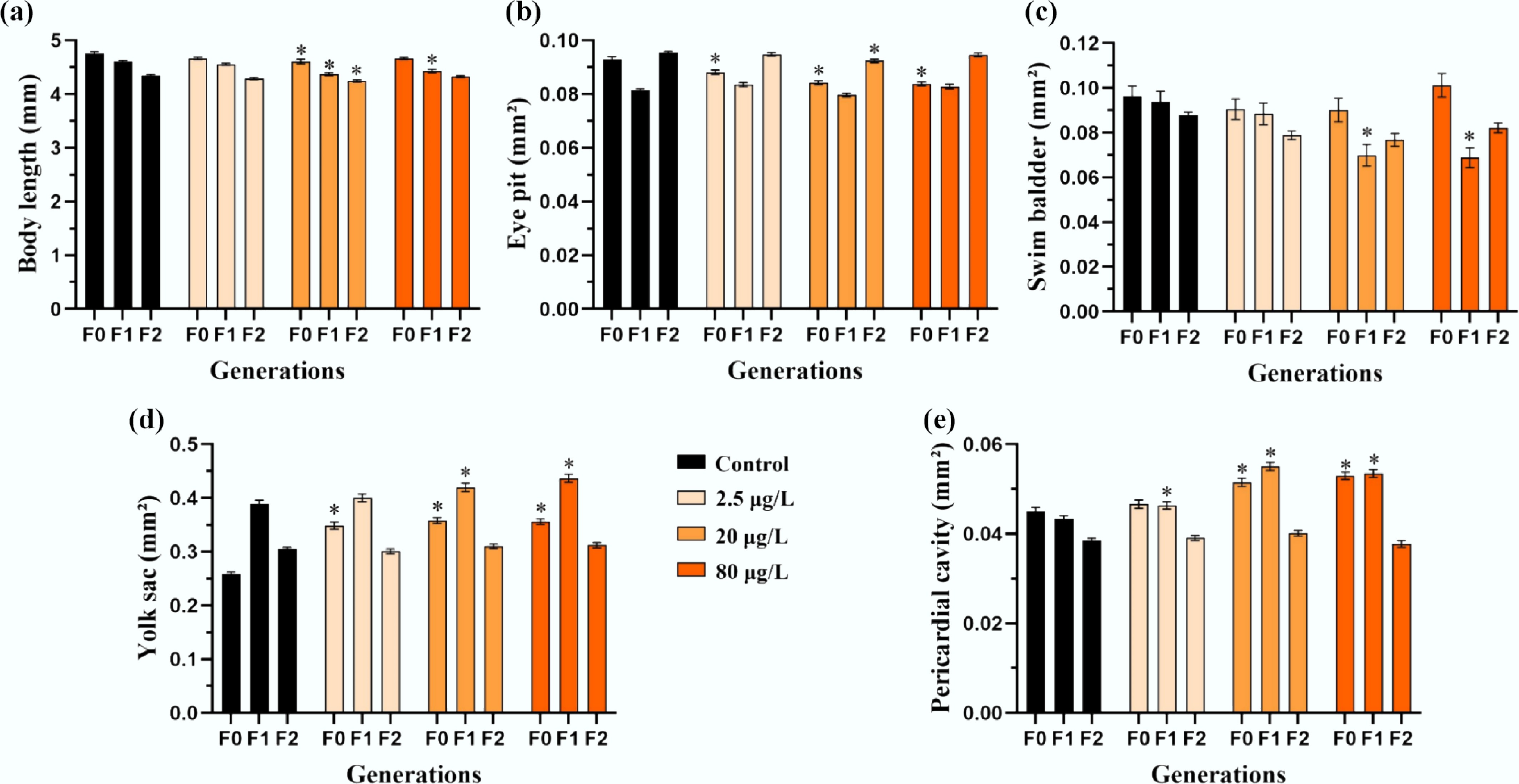

Ancestral benzo[a]pyrene exposure induced multigenerational developmental and osteotoxic effects in medaka F0–F2 larvae. Significant, concentration-specific alterations were observed: body length was reduced in the 20 μg/L treatment across all three generations (4.608 ± 0.061 mm compared to 4.751 ± 0.039 mm in F0 control; 4.360 ± 0.043 mm compared to 4.627 ± 0.026 mm in F1 control; 4.260 ± 0.032 mm compared to 4.352 ± 0.021 mm in F2 control). Eye pit size decreased in F0 (0.0883 ± 0.0010, 0.0833 ± 0.0011, and 0.0832 ± 0.0010 mm2 for 2.5, 20, and 80 μg/L treatment compared to 0.0919 ± 0.0011 mm2 for the control, respectively) and F2 (0.0918 ± 0.0010 mm2 for the 20 μg/L treatment compared to 0.0952 ± 0.0009 mm2 for the control) larvae. Swim bladder size was reduced only in F1 larvae (0.0718 ± 0.0082 and 0.0715 ± 0.0074 mm2 for the 20 and 80 μg/L treatment compared to 0.0995 ± 0.0083 mm2 for the control, respectively). In contrast, yolk sac edema was induced in all F0 treatments and in F1 larvae (0.417 ± 0.010 and 0.436 ± 0.011 mm2 for the 20 and 80 μg/L treatment compared to 0.385 ± 0.009 mm2 for control, respectively), while pericardial cavity size was significantly larger in F0 (0.0514 ± 0.0011 and 0.0527 ± 0.0012 mm2 for the 20 and 80 μg/L treatment compared to 0.0451 ± 0.0008 mm2 for the control, respectively) and F1 (0.0462 ± 0.0012, 0.0551 ± 0.0014, and 0.0531 ± 0.0013 mm2 for the 2.5, 20, and 80 μg/L compared to 0.0428 ± 0.0009 mm2 for the control, respectively) treatments (p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA; Fig. 3a–e).

Figure 3.

Multigenerational developmental toxicity of freshly hatched medaka larvae induced by F0 embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure. Morphometric parameters including (a) total body length, (b) eye pit, (c) swim bladder, (d) yolk sac, and (e) pericardial cavity are presented for freshly hatched larvae from the F0–F2 generations (n = 4; data are presented as mean ± SEM). A comparison between each benzo[a]pyrene treatment and the corresponding control is provided, and * indicates p < 0.05, according to a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

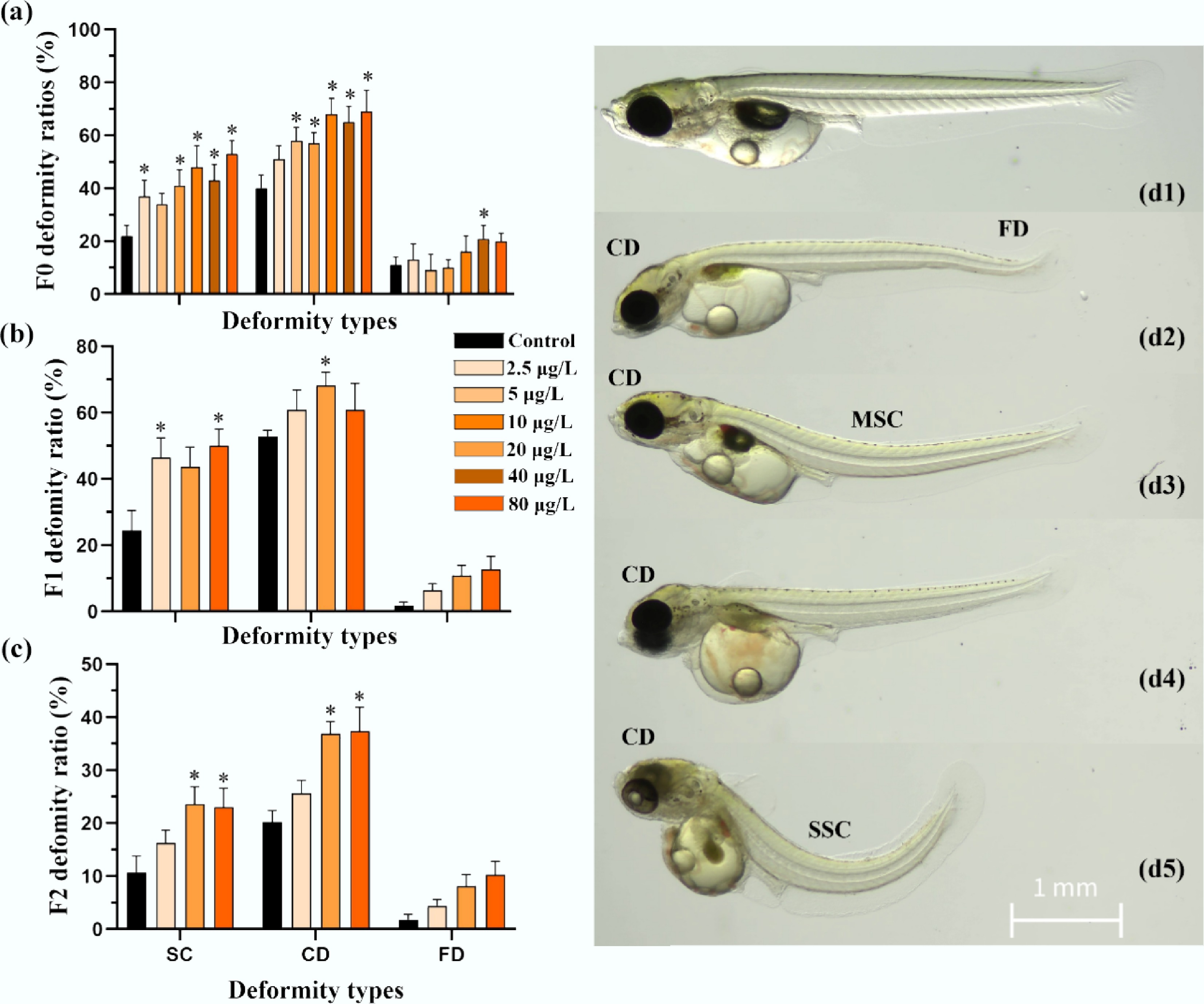

Ancestral benzo[a]pyrene exposure induced body deformities—including craniofacial, spinal, and fin deformities—in F0–F2 larvae (Fig. 4). In the F0 generation, craniofacial deformity (spinal deformity) elevated significantly (p < 0.05, χ2 test) from 39.9% ± 5.1% (22.1% ± 4.0%) for the control to 51.1% ± 5.1% (36.9% ± 6.1%), 68.1% ± 5.9% (48.2% ± 8.1%), and 69.2% ± 7.8% (53.3% ± 4.9%) for the 2.5, 20, and 80 μg/L treatments, respectively. These effects persisted transgenerationally, and significantly higher incidences of spinal curvature were observed in the F1 and F2 generations at 20 and 80 μg/L (43.6% ± 5.8% and 50.1% ± 5.0% compared to 24.5% ± 5.9% for F1 control; 23.6% ± 3.3% and 23.0% ± 3.6% compared to 10.7% ± 3.1% for F2 control, respectively), while craniofacial deformity persisted at 20 μg/L (68.2% ± 3.8% compared to 52.7% ± 1.9% for F1 control; 36.9% ± 2.3% compared to 20.2% ± 2.2% for F2 control). In contrast, fin deformity was only significantly increased at 40 μg/L in the F0 generation (21.1% ± 4.8% compared to 11.0% ± 2.8% for F0 control).

Figure 4.

Multigenerational osteotoxicity of medaka freshly hatched larvae induced by F0 embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure. Skeletal deformities in craniofacial, trunk, and tail fin are presented for medaka freshly hatched larvae from the (a) F0, (b) F1, and (c) F2 generations with and without ancestral benzo[a]pyrene exposure (n = 4; data are presented as mean ± SEM). A comparison of the mean values is provided, and * indicates p < 0.05, according to a χ2 test. Representative images of control fish with (d1) normal body shape, and (d2–d5) larvae with craniofacial deformity (CD), spinal curvature (mild and severe spinal curvature are labeled using MSC and SSC, respectively), and fin deformity (FD) in the benzo[a]pyrene treatment groups are shown.

Metabolomic alterations in F0 and F2 embryos

-

Metabolomic analysis of F0 and F2 embryos demonstrated good stability, as shown by the quality control total ion chromatograms (Supplementary Figs S1, S2). We confidently identified 812 (positive mode) and 736 (negative mode) metabolites in F0 embryos, and 1,051 (positive) and 1,041 (negative) in F2 embryos. In principal component analysis (PCA), PC1 and PC2 explain 32% and 20.9% of the total variance in metabolites detected for the F0 embryos, respectively. By contrast, PC1 and PC2 explain 50.1% and 10.2% of the total variance in metabolites detected for the F2 embryos, respectively (Supplementary Figs S3, S4).

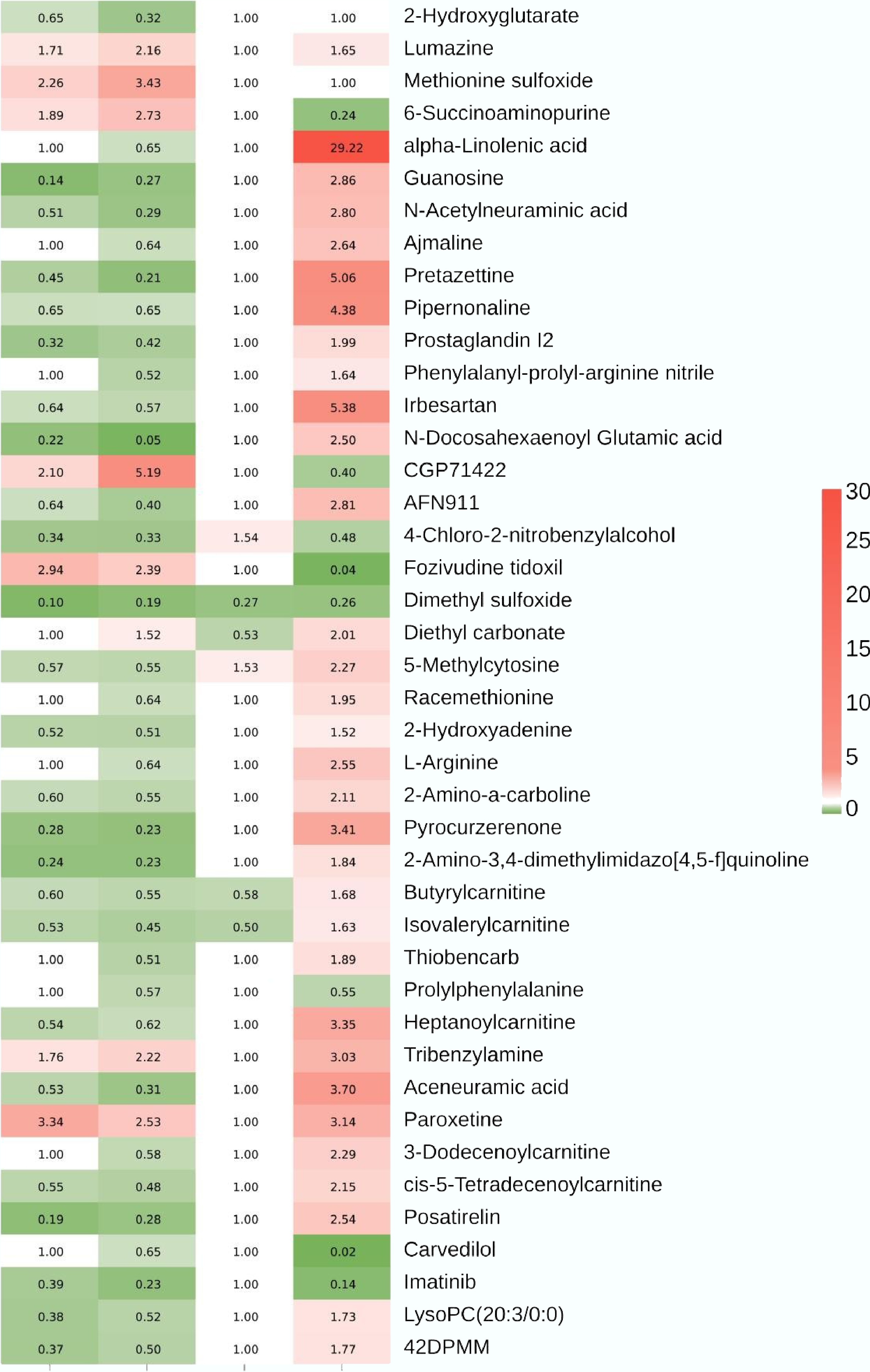

The high-quality metabolomic data are evidenced by good repeatability and strong correlation of QC samples (Supplementary Figs S3–S6). In PCA score plots, replicates were clustered by treatment in both F0 and F2 generations. A clear separation was observed between the control and the 2.5 and 20 μg/L treatments in F0 embryos. In contrast, F2 profiles showed proximity between the control and 2.5 μg/L group, while the 20 μg/L treatment remained distinct. OPLS-DA models for F0 and F2 generations showed a clear separation in metabolomic profiles between control and benzo[a]pyrene treatment groups (Supplementary Figs S7–S10), with high model reliability (R2: 0.994–0.999, Q2: 0.644–0.98; Supplementary Table S1). Based on a threshold of VIP > 1.0, p < 0.05, and a fold change ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67, 233 and 254 DAMs were identified in F0 embryos exposed to 2.5 and 20 μg/L benzo[a]pyrene, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S11). In the F2 generation, ancestral exposure resulted in 86 and 752 DAMs at the same concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S12). Notably, 42 DAMs were shared between the 20 μg/L treatments across both generations (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

A heat map showing alterations in metabolomic profiles in F0 and F2 medaka embryos following F0 embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure. A total of 42 differentially abundant metabolites are shared by the 20 μg/L benzo[a]pyrene treatment of F0 and F2 generations, alongside their corresponding profiles in the 2.5 μg/L benzo[a]pyrene treatment of F0 and F2 embryos. The column from left to right represents F0 2.5 μg/L treatment, F0 20 μg/L treatment, F2 2.5 μg/L treatment, and F2 20 μg/L treatment, respectively. 42DPMM: 42. 2-(4,4-Difluoro-1-piperidinyl)-6-methoxy-N-[1-(1-methylethyl)-4-piperidinyl]-7-[3-(1-pyrrolidinyl)propoxy]-4-quinazolinamine.

For each generation, all DAMs from positive and negative ionization modes were pooled for KEGG pathway analysis. This revealed distinct multigenerational disruption: in the F0 generation, 20 and 26 pathways were significantly (p < 0.05) altered at 2.5 and 20 μg/L benzo[a]pyrene, respectively (Supplementary Tables S2, S3). These pathways spanned four key functional categories: (1) detoxification (e.g., ABC transporters); (2) metabolic homeostasis (e.g., taurine and hypotaurine, purine, and pyrimidine metabolism); (3) cell signaling and development (e.g., VEGF, PI3K-Akt, mTOR, FoxO, and cAMP signaling pathways); and (4) neurological and sensory functions (e.g., neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, GABAergic and serotonergic synapses). Conversely, the F2 generation showed a more pronounced concentration-response, with only three pathways altered at 2.5 μg/L compared to 71 at 20 μg/L (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S4–S6). A notable feature in F2 was the significant enrichment of pathways governing oxidative balance, including the sulfur relay system, thiamine metabolism, and sulfur metabolism. Multiple metabolomic pathways related to energy metabolism were identified in the 20 μg/L treatment of the F2 generation. Cross-generational analysis identified a core signature of 10 pathways consistently disrupted by the 20 μg/L treatment in both F0 and F2 generations, including mTOR signaling, purine metabolism, ABC transporters, and neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, underscoring their role as persistent targets of toxicity (Supplementary Tables S3, S5).

Table 1. Significantly enriched KEGG metabolic pathways in F2 medaka embryos ancestrally exposed to benzo[a]pyrene at 20 μg/L

Pathway Level 2 Pathway ID p-value Up-DAMs Down-DAMs Central carbon metabolism in cancer Cancer: overview ko05230 1.16E-15 Pyruvic acid; L-Alanine; Serine; Fumaric acid; Leucine; Isocitric acid; Isoleucine; Methionine; Malic acid;

L-Arginine; L-Tyrosine; L-Tryptophan; Lactic acidGlutamine Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism Amino acid metabolism ko00260 7.26E-10 Pyruvaldehyde; Glyoxylic acid; Pyruvic acid; Serine; Phosphoserine; Sarcosine; Choline; Guanidoacetic acid; Ectoine; L-Tryptophan Glyceric acid D-Amino acid metabolism Metabolism of other amino acids ko00470 4.32E-06 Pyruvic acid; L-Alanine; Serine; 5-Aminopentanoic acid; Ornithine; Lysine; Methionine; L-Arginine Glutamine Efferocytosis Transport and catabolism ko04148 3.25E-05 Ornithine; Methionine; L-Arginine; LysoPC

(P-18:1(9Z)/0:0); LysoPC(P-18:0/0:0); LysoPC(18:3(6Z,9Z,12Z)/0:0); LysoPC(22:6(4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)/0:0); Lactic acid− Arginine and proline metabolism Amino acid metabolism ko00330 4.47E-05 Glyoxylic acid; Pyruvic acid; 5-Aminopentanoic acid; Sarcosine; Creatinine; Guanidoacetic acid; Ornithine; L-Arginine − Tyrosine metabolism Amino acid metabolism ko00350 8.84E-05 Pyruvic acid; Fumaric acid; Beta-Tyrosine;

4-Hydroxycinnamic acid; 5,6-Dihydroxyindole;

L-Tyrosine; DOPAHomovanillic

acidGlyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism Carbohydrate metabolism ko00630 0.000165 Glyoxylic acid; Pyruvic acid; Serine; Isocitric acid; Malic acid Glyceric acid; Glutamine Cysteine and methionine metabolism Amino acid metabolism ko00270 0.000242 Pyruvic acid; L-Alanine; Serine; Phosphoserine;

5'-Methylthioadenosine; Methionine; S-Adenosylhomocysteine− Pyruvate metabolism Carbohydrate metabolism ko00620 0.000273 Pyruvaldehyde; Pyruvic acid; Lactic acid; Fumaric acid; Malic acid − Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) Carbohydrate metabolism ko00020 0.000434 Pyruvic acid; Fumaric acid; Isocitric acid; Malic acid − Arginine biosynthesis Amino acid metabolism ko00220 0.000759 Fumaric acid; Ornithine; L-Arginine Glutamine Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis Amino acid metabolism ko00290 0.000759 Pyruvic acid; alpha-Ketoisovaleric acid; Leucine; Isoleucine − Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism Amino acid metabolism ko00250 0.001635 Pyruvic acid; L-Alanine; Fumaric acid Glutamine Lysine degradation Amino acid metabolism ko00310 0.003631 5-Aminopentanoic acid; Glutaric acid; L-Pipecolic acid; Lysine; N6-Acetyl-L-lysine − Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation Amino acid metabolism ko00280 0.007321 alpha-Ketoisovaleric acid; 3-Hydroxyisovaleric acid; Leucine; Isoleucine − Oxidative phosphorylation Energy metabolism ko00190 0.019938 Phosphate; Fumaric acid − -

F0 embryonic exposure to environmental benzo[a]pyrene induced multigenerational developmental toxicity and transgenerational osteotoxicity in medaka. The effects include reduced survivorship and hatching success in the F0 generation, alterations in morphometric parameters (e.g., body length, eye pit, swim bladder, yolk sac, and pericardial cavity) in the F0–F1 generations, and an increased frequency of skeletal malformations (e.g., craniofacial and spinal deformities) in the F0–F2 generations. Novel metabolomic data from F0 and F2 embryos linked these phenotypic changes to disruptions in four major biological processes: (1) metabolic activation and initial stress; (2) energy metabolism and oxidative balance; (3) cell signaling and developmental programming; and (4) neurological and sensory functions.

Metabolic activation and initial stress

-

The overall toxicity of the procarcinogen benzo[a]pyrene is determined by the critical balance between its metabolic activation and detoxification[1,4]. Upon cellular entry, benzo[a]pyrene is primarily activated via the drug metabolism–other enzymes pathway by enzymes like cytochrome P450 (e.g., CYP1A1) and epoxide hydrolase. This metabolism generates the highly reactive, ultimate carcinogen BPDE and ROS, leading to genetic damage, oxidative stress, and epigenetic modifications[5]. The developmental toxicity observed in F0 embryos and larvae following embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure was attributable to this molecular and cellular damage, which is supported by benzo[a]pyrene-induced cellular dysfunction and apoptosis in skeletal tissues of fish embryos and larvae reported previously[14,17,22,23]. Concurrently, ABC transporters function as cellular efflux pumps to expel benzo[a]pyrene and its metabolites, serving as a key defense mechanism, and their efficiency may modulate the intracellular concentration of these compounds[24−26]. An overload or inhibition of this system consequently exacerbates all downstream toxic effects. The resulting DNA adducts and oxidative damage can induce genetic mutations, aberrant epigenetic modifications, and cell death in embryos[5,14,17], forming the probable molecular basis for the observed embryonic lethality, delayed development, reduced hatching success, and organ dysmorphogenesis—such as craniofacial deformity, spinal curvature, and fin deformity—in the F0 generation.

Supporting this mechanism, metabolomic analysis revealed enrichment of the drug metabolism-other enzymes and ABC transporters pathways in F0 embryos, indicating active benzo[a]pyrene metabolism and detoxification after exposure. Notably, in the unexposed F2 generation, ABC transporters remained significantly enriched, suggesting their potential role in transporting substances across pericellular membranes in a transgenerational context. While survivorship and development in the F1–F2 generations were comparable to the control levels, alterations in morphometric parameters were largely present in F1 larvae and mostly alleviated in F2 larvae. These findings partially align with previous work[10], where dietary benzo[a]pyrene administration to F0 adult zebrafish induced multigenerational toxicity, albeit with effects manifesting differently across generations. A key distinction in the present study is the persistence of shortened body length, craniofacial deformity, and spinal curvature into the F1–F2 generations. This finding on transgenerational osteotoxicity in freshly hatched medaka larvae is novel and distinct from the transgenerational vertebral deformity reported in older (17 d post-hatch) F1–F3 medaka larvae descended from benzo[a]pyrene-exposed ancestors[11,12].

Energy metabolism and oxidative balance

-

Energy metabolism and oxidative balance are fundamental to successful embryo development, as they fuel and protect the complex process of morphogenesis[27]. The embryo, dependent on a finite yolk supply, requires efficient energy production through glycolysis and beta-oxidation to generate the necessary ATP for cell division, tissue differentiation, and morphogenesis[28,29]. This high metabolic rate inherently produces ROS, which in controlled amounts act as vital developmental signals but in excess cause oxidative stress, damaging DNA, proteins, and lipids[27,28]. Such disruption can lead to failed organ formation, skeletal deformities, and improper fin development, making the harmonious interplay between energy production and antioxidant defense essential for accurate execution of the genetic blueprint[29,30].

In F0 embryos, benzo[a]pyrene exposure induced widespread metabolic dysregulation, directly impairing core pathways including C5-branched dibasic acid metabolism, butanoate metabolism, and purine and pyrimidine metabolism. A characteristic triad of metabolite changes—elevated 3-hydroxybutyric acid, increased oxoglutaric acid (α-KG), and decreased 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG)—was identified as a core mechanism of toxicity. This triad may collectively disrupt energy metabolism, redox balance, and epigenetic regulation[20,31]. The rise in 3-hydroxybutyric acid possibly suggests a compensatory shift toward ketogenesis, while the high α-KG/2-HG ratio possibly activates α-KG-dependent dioxygenases[32,33]. This may lead to the suppression of HIF-1α, disrupting hypoxic signaling[34], and cause epigenetic dysregulation, corrupting the genetic blueprint for morphogenesis and manifesting as severe body malformations[20,35,36]. Indeed, benzo[a]pyrene exposure has been shown to induce both global and gene-specific DNA hypomethylation in developing zebrafish embryos[37]. Most recently, it was found to alter histone methylation and acetylation patterns in twist-positive and col10a1-positive osteoblasts of medaka[38]. Building on these epigenetic findings, a hypothetical model is proposed that links metabolomic dysregulation (e.g., an altered α-KG/2-HG ratio) to the observed spinal curvature and reduced body length (Supplementary Fig. S13). Further experimental validation is required to confirm the mechanistic role of this pathway.

Concurrently, the significant dysregulation of purine and pyrimidine metabolism, evidenced by an imbalance in key nucleotides, directly impedes embryonic development[39]. Benzo[a]pyrene-induced DNA damage activates repair systems that massively consume the nucleotide pool, while oxidative stress likely disrupts both de novo and salvage synthesis pathways[40,41]. During rapid embryonic cell division, this insufficient nucleotide supply may impede genome replication and transcription, leading to arrested cell division, which manifests as developmental delay, reduced body size, and organ hypoplasia[42]. Furthermore, reduced L-arginine content may disrupt the vital nitric oxide signaling pathway. The resulting nitric oxide deficiency may impair cardiovascular development, neural communication, and angiogenesis, contributing to the observed axial and skeletal malformations[36,43,44].

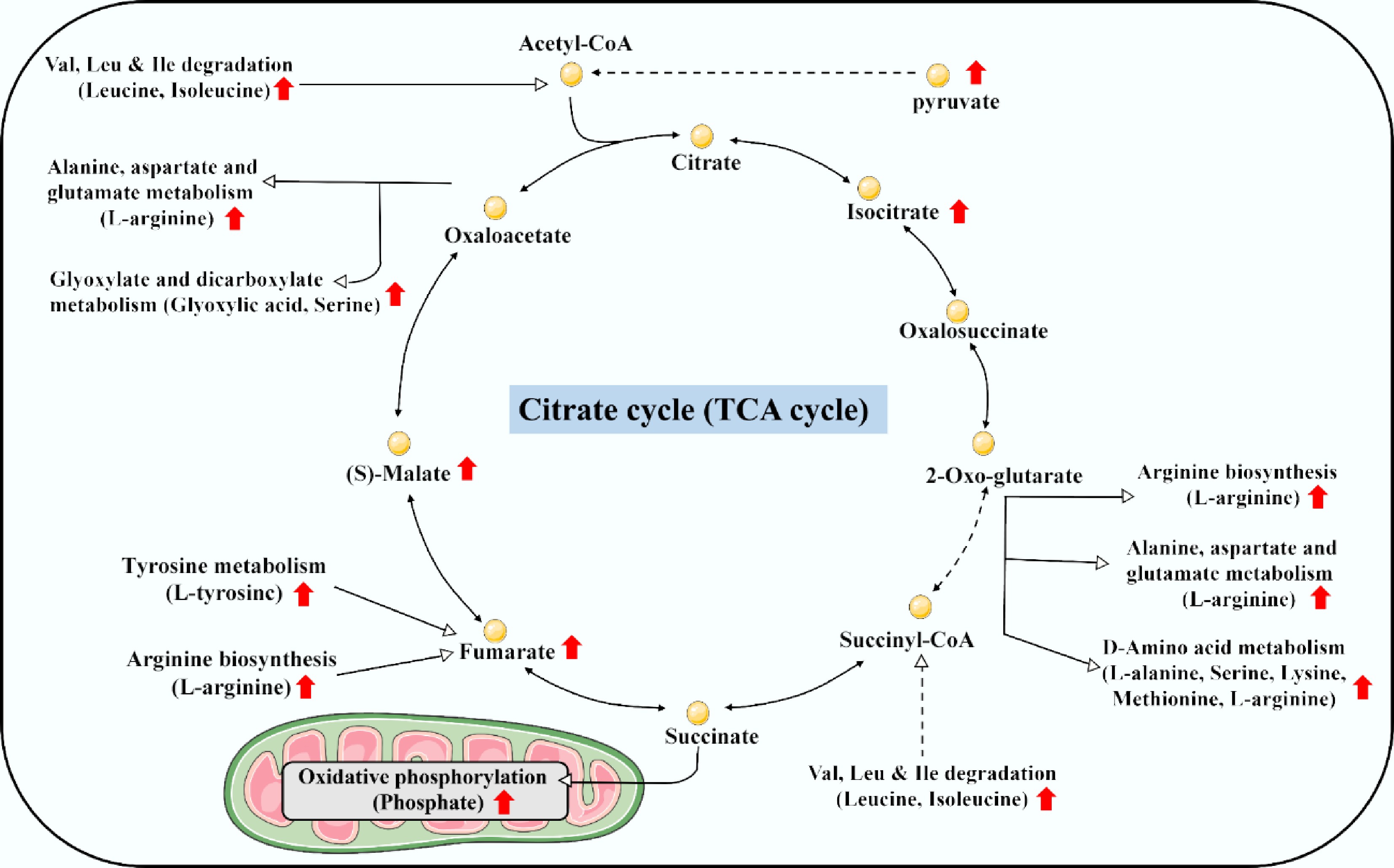

In the unexposed F2 generation, broader metabolic remodeling and compensatory responses were observed (Table 1 & Fig. 6). Pathways including the citrate cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and multiple amino acid metabolisms were dysregulated, with key metabolites like pyruvic acid, isocitric acid, α-KG, fumaric acid, malic acid, lactic acid, and various amino acids (L-alanine, serine, leucine, isoleucine, methionine, lysine, D-valine, D-phenylalanine, L-arginine, L-tyrosine, and L-tryptophan) being exclusively elevated. This pattern suggests an overwhelming compensatory regulation aimed at boosting energy production and biosynthetic precursor supply. The accumulation of taurine further supports this response, possibly by enhancing antioxidant defense and cellular osmotic balance[45,46]. This metabolic compensation underpins the observed recovery in phenotypic endpoints such as survivorship, hatching success, and most morphometric parameters.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram showing an overwhelming elevation of energy metabolism and supply in F2 medaka embryos descended from F0 ancestors with embryonic exposure to benzo[a]pyrene at 20 μg/L.

Despite this general recovery, skeletal deformities persisted transgenerationally. Based on the F0 and F2 embryo metabolomic data, the massive metabolic shift in F2 larvae might not represent a successful compensatory regulation but rather a maladaptive establishment of a pathological steady state, aligning with the 'energy debt' hypothesis[47,48]. This reprogramming might fail to rescue skeletal development when resources are misallocated, where the reversal of acylcarnitine profiles from suppression in F0 to sharp elevation in F2 indicates a high-cost shift toward catabolic energy mobilization, thereby continuously depriving skeletogenesis of necessary anabolic substrates. Importantly, these metabolic changes possibly operated within an immutable epigenetic landscape: the normalization of 2-hydroxyglutarate in F2 alongside elevated 5-methylcytosine seemingly supports a 'hit-and-run' mechanism[49], where the initial exposure durably locked in erroneous epigenetic programs (e.g., dysregulation of osteogenic genes) during a sensitive early developmental window[5,50]. The F2 metabolic profile possibly reflects a costly survival trade-off: basic homeostasis was prioritized and likely redirects metabolic resources toward essential organogenesis (e.g., brain, heart, and eyes) at the direct and sustained expense of skeletal development. Nonetheless, these hypotheses represent critical avenues, and future research is required to fully elucidate the underlying genetic and epigenetic mechanisms.

Cell signaling and developmental programming

-

Cell signaling and developmental programming are the fundamental architects of fish embryo development, directly responsible for establishing and maintaining a normal body shape[51]. Any disruption to this intricate signaling can hijack these essential pathways, leading to organogenesis dysfunction and malformations such as skeletal deformities[52]. Benzo[a]pyrene exposure may induce such disruptions through multiple interconnected signaling pathways.

A primary mechanism involves an energy crisis triggered by benzo[a]pyrene metabolism. The observed increase in adenosine monophosphate (AMP) in F0 embryos, a critical biomarker of metabolic stress, signals ATP depletion[53]. This depletion results from benzo[a]pyrene-induced oxidative stress, cellular damage repair, and mitochondrial dysfunction[6,54]. Elevated AMP directly inhibits the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), a central coordinator of anabolic processes and a known energy sensor[55]. The consequent suppression of mTORC1 activity might dysregulate its downstream effectors, including the PI3K-Akt and FoxO signaling pathways, which are essential for cell growth, proliferation, and survival during morphogenesis[56]. This cascade of energy-sensing failure likely underlies critical developmental defects such as failed neural tube closure, impaired organ development, and skeletal malformations.

Additionally, benzo[a]pyrene toxicity impairs cardiovascular and tissue morphogenesis, possibly through the suppression of prostaglandin I2 (PGI2) within the VEGF signaling pathway[57,58]. As a potent vasodilator and inhibitor of platelet aggregation, diminished PGI2 levels may compromise the establishment of the embryonic circulatory system, leading to impaired vessel formation, inadequate blood flow, and localized hypoxia[57,59]. This is evidenced by underdeveloped cardiovascular systems and enlarged pericardial cavities in benzo[a]pyrene-exposed embryos[60,61]. Furthermore, the role of PGI2 as a guide for cell differentiation and migration means its deficiency disrupts precise morphogenetic processes, resulting in failed organogenesis and body shape deformities. The recovery of embryonic development in the F2 generation alongside PGI2 accumulation may further underscore its critical role; however, function validation in a subsequent study is required to ascertain this hypothesis.

The multigenerational dimension of this toxicity and its recovery is elucidated by contrasting metabolic profiles during efferocytosis. In F0 embryos, benzo[a]pyrene may induce excessive apoptosis, overloading the efferocytic machinery and depleting key signaling metabolites[62]. Reductions in pro-resolving LysoPCs (e.g., LysoPC(22:6)) may impair phagocyte recruitment and inflammation resolution, while a concurrent drop in L-arginine cripples the production of nitric oxide and polyamines, which are essential for vascularization and osteochondral development[62,63]. This failure possibly leads to accumulated apoptotic debris, secondary necrosis, and a persistent pro-inflammatory state that disrupts skeletal patterning, manifesting as severe malformations[14,17,18].

On the contrary, the F2 generation exhibits a powerful, coordinated shift towards metabolic compensation and tissue repair. Elevated levels of ornithine, methionine, L-arginine, specific pro-resolving LysoPCs (including LysoPC[P-18:0]), and lactic acid indicate a restored capacity for efficient efferocytosis and anabolic support. Restored methionine levels may facilitate crucial epigenetic reprogramming, the rise in LysoPCs promotes inflammation resolution, and increased lactic acid may fuel aerobic glycolysis to generate ATP and biosynthetic precursors. Collectively, these changes create a favorable anabolic and anti-inflammatory milieu that rectifies the developmental errors of the F0 fish, enabling the substantial phenotypic recovery observed in the F2 offspring.

Neurological and sensory functions

-

Fish possess a sophisticated suite of neurological and sensory functions that are exquisitely adapted to their aquatic environment. Their brains feature highly developed regions, such as the optic tectum for visual processing and a large cerebellum for coordinated movement, which efficiently interpret a constant stream of sensory data[64]. The proper formation of the head, with sufficient brain space and correctly sized eye pits, is a structural prerequisite for these normal neurological and sensory functions, which are in turn critical for survival[65].

In F0 embryos, benzo[a]pyrene exposure disrupts this crucial development by dysregulating key neuro-specific metabolomic pathways, including neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, GABAergic synapse, serotonergic synapse, and pathways of neurodegeneration. This molecular disruption is phenotypically manifested as a smaller eye pit and a malformed head. The toxicity is driven by a confluence of metabolic disturbances: elevated AMP signals a severe cellular energy deficit (ATP depletion) that may halt energy-intensive morphogenetic processes, while increased 5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan suggests aberrant serotonin synthesis that can lead to defective neural and vascular patterning[53]. Simultaneously, decreased L-arginine impairs nitric oxide production, possibly compromising vasodilation and angiogenic signaling, and a reduction in PGI2 disrupts pathways essential for vascular integrity and tissue remodeling[43,59], warranting functional validation in a future study.

This multifaceted failure in energy supply, neurotransmitter balance, and circulatory signaling synergistically might have caused widespread errors in organogenesis and axial patterning. The structural deformities incurred during embryonic development can also lead to neurobehavioral toxicity in post-hatch larvae, manifesting as abnormal motor behaviors and learning deficits[5]. Conversely, the observed accumulation of L-arginine and PGI2 in the F2 generation is likely a key factor to contribute to the alleviation of these neurological and sensory dysfunctions, facilitating a partial developmental recovery.

Limitations and implications

-

This study provides metabolomic insights into the multigenerational toxicity of benzo[a]pyrene in fish, yet several limitations should be acknowledged. First, while metabolomic perturbations suggest epigenetic involvement (e.g., altered α-KG and 2-HG levels), direct epigenetic measurements, such as DNA methylation or histone modifications, were not performed. Future work integrating multi-omics approaches will be essential to validate epigenetic inheritance as a mechanistic pathway. Second, the exposure was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, which may not fully capture the complexity of natural aquatic environments where mixtures of pollutants and environmental stressors coexist. Finally, the observed phenotypic recovery in F2 larvae, interpreted here as a survival trade-off, warrants further investigation into long-term fitness consequences, such as reproductive success and disease susceptibility in later life stages or generations.

Despite these limitations, the findings carry clear environmental implications. Benzo[a]pyrene is a widespread persistent pollutant, and the demonstration of its multigenerational effects—even after exposure ceases—highlights a latent ecological risk that could compromise population resilience over time. The metabolomic shifts identified here, particularly in energy and redox metabolism, may serve as early warning biomarkers for assessing multigenerational toxicity in wild fish populations. From a regulatory perspective, these results underscore the need to consider long-term and multigenerational impacts in ecological risk assessments, rather than relying solely on acute or single-generation toxicity data. Ultimately, this work reinforces the importance of mitigating benzo[a]pyrene emissions to protect aquatic ecosystems and the biodiversity they support.

-

This study demonstrates that embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure at environmentally relevant concentrations induces multigenerational developmental and skeletal toxicity in medaka. The observed impairments, including elevated skeletal malformations and altered morphometrics across the F0–F2 generations, are mechanistically linked to widespread metabolomic dysregulation. Key perturbations in energy metabolism, redox balance, and cellular signaling pathways (e.g., the triad of 3-hydroxybutyric acid, α-KG, and 2-HG) provide a functional basis for the observed transgenerational phenotypes. The partial morphological recovery in the F2 generation suggests a potential survival trade-off, wherein metabolic resources are prioritized for essential functions at the expense of skeletal development. These findings underscore the value of metabolomics in revealing the latent and inherited physiological costs of early-life toxicant exposure.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/newcontam-0025-0022.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Yinhua Chen: investigation, methodology, data curation, visualization, writing − original draft; Huiju Lin, Jiangang Wang, Feilong Li, Rim EL Amouri, Jack Chi-Ho Ip, Wenhua Liu: visualization, writing − review and editing; Jiezhang Mo: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing − original draft, funding acquisition, supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42207318), and Shantou University STU Scientific Research Initiation Grant (Grant No. NTF23010).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests.

-

Benzo[a]pyrene exposure induced multigenerational developmental toxicity in medaka.

Reduced body length and elevated bone deformities were observed in F0–F2 larvae.

Novel metabolomic data were linked to developmental and skeletal impairment.

Benzo[a]pyrene exposure disrupted energy metabolism and oxidative balance.

Energy remodeling and compensation contributed to the developmental recovery.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files newcont-s2025-0030-File001

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen Y, Lin H, Wang J, Li F, Amouri REL, et al. 2026. Multigenerational developmental and skeletal toxicity from benzo[a]pyrene exposure in F0 and F2 medaka: metabolic trade-offs and survival costs. New Contaminants 2: e002 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0022

Multigenerational developmental and skeletal toxicity from benzo[a]pyrene exposure in F0 and F2 medaka: metabolic trade-offs and survival costs

- Received: 11 November 2025

- Revised: 16 December 2025

- Accepted: 26 December 2025

- Published online: 19 January 2026

Abstract: Benzo[a]pyrene is a ubiquitous emerging contaminant; however, whether and how it disrupts fish development and skeletal health across multiple generations, particularly at the metabolomic level, remains unclear. The latent effects of embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure at environmentally relevant levels (2.5–80 μg/L) on developmental toxicity and skeletal integrity were assessed over three generations (F0–F2) of medaka. The F1 and F2 offspring were reared in clean water to isolate the inherited impacts. Untargeted metabolomic analysis (Variable Importance in Projection > 1.0, p < 0.05 in Student's t-test, and ratio ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67) of F0 and F2 embryos identified 233 (86) and 254 (752) differentially abundant metabolites in the F0 (F2) embryos exposed ancestrally to benzo[a]pyrene at 2.5 and 20 μg/L. Benzo[a]pyrene exposure induced multigenerational impairments, including reduced survivorship and hatching success in F0 embryos, altered morphometrics (e.g., reduced body length, smaller eye pit, and larger pericardial cavity) in F0–F1 larvae, and elevated skeletal malformation frequency (e.g., craniofacial and spinal deformities) in F0–F2 larvae. Metabolomic perturbations were linked to four major biological processes: (1) metabolic activation and oxidative stress; (2) disruption of energy metabolism and redox balance, evidenced by a triad of elevated 3-hydroxybutyric acid, oxoglutaric acid, and depleted 2-hydroxyglutarate; (3) dysregulation of cell signaling and developmental programming, including energy crisis (elevated AMP), impaired vascular development (reduced prostaglandin I2), and disrupted efferocytosis; and (4) impairment of neurological and sensory functions. These findings demonstrate that F0 embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure induces lasting multigenerational toxicity by disrupting metabolic, signaling, and sensory pathways, ultimately leading to developmental impairment and osteotoxicity. While F2 larvae showed partial morphological recovery, this may represent a survival trade-off, where metabolic resources were redirected from skeletal development to support the formation of essential organs. This study identifies the metabolomic basis for the multigenerational developmental and skeletal toxicity induced by embryonic benzo[a]pyrene exposure.

-

Key words:

- Emerging contaminant /

- Fish /

- Multigenerational impact /

- Skeletal malformation /

- Metabolome /

- Biomarker