-

Nitrogen (N) is a fundamental nutrient that limits agricultural productivity, yet its utilization efficiency in global cropping systems remains relatively low[1]. Despite significant advancements in fertilizer technology and nutrient management, global assessments by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations report that, on average, only approximately half of the applied nitrogen is assimilated by crops. The remainder is lost through various pathways, such as ammonia volatilization, surface runoff, denitrification, and leaching[2,3]. These losses frequently occur simultaneously and interact, resulting in inefficient fertilizer use and higher production costs. More importantly, the release of reactive nitrogen into nearby water bodies accelerates eutrophication and promotes recurrent algal blooms, which ultimately destabilize aquatic ecological structures and functions[4]. The generation of nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas with a warming potential nearly 298 times that of carbon dioxide, adds dimension to the environmental burden associated with nitrogen mismanagement[5,6]. Methane (CH4), another potent greenhouse gas, is also emitted in considerable quantities from flooded rice systems, making paddy fields a primary anthropogenic source of CH4 on a global scale[7]. Although the presence of aquatic animals has been hypothesized to influence CH4 production and oxidation by altering sediment oxygenation, organic matter distribution, and microbial community composition, available studies report divergent outcomes across climatic zones and management practices, suggesting that the underlying mechanisms remain insufficiently resolved[8]. Thus, improving nitrogen use efficiency and mitigating nitrogen losses and greenhouse gas emissions, while maintaining global food security, have become central objectives in agricultural ecology and environmental sciences[9]. Taken together, these findings highlight the need to simultaneously improve nitrogen-use efficiency and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions to achieve environmentally sound, productive agricultural systems.

Across much of Asia, paddy fields function as representative agro-wetland ecosystems in which dynamic hydrological regimes interact with complex biogeochemical processes to regulate nutrient cycling[10]. The cyclic flooding and draining that typify rice cultivation create fluctuating redox environments that strongly shape nitrification and denitrification processes[4]. Despite extensive work on nitrogen cycling in rice monocultures, substantial knowledge gaps persist, particularly regarding how fine-scale environmental gradients modulate nitrogen transformation pathways under increasingly variable climatic and hydrological pressures[11]. Under conventional monocropping conditions, excessive nitrogen fertilizer inputs are common, leading to diminished fertilizer-use efficiency and enhanced redistribution of nitrogen among soil, water, and the atmosphere. This redistribution intensifies the risk of ecological degradation and contributes to pollution at watershed scales[12]. Emerging studies argue that current management recommendations often overlook the inherent micro-scale heterogeneity of paddy soils, such as discontinuities in redox potential or uneven distributions of organic carbon, resulting in oversimplified nutrient-management frameworks and underestimation of actual nitrogen losses[13]. Understanding the micro-level mechanisms governing nitrogen transformations in these systems is therefore essential for developing ecologically robust strategies that simultaneously sustain crop yields and minimize environmental impacts.

Rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, which have persisted for millennia in various regions of Asia, have gained renewed interest in recent decades as part of global efforts to implement climate-responsive, resource-efficient, and ecologically restorative agricultural systems[14]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that these co-culture systems can lower fertilizer and pesticide requirements, improve soil physicochemical properties, enhance rice productivity, and promote more efficient internal nitrogen cycling[15]. Furthermore, the activities of aquatic animals, such as sediment disturbance, grazing on algae and detritus, and the excretion of nitrogen-rich metabolites, can substantially reshape the redox environment and carbon availability in both the rhizosphere and the overlying water column[16]. These changes, in turn, stimulate microbial processes including nitrification and the mineralization of organic nitrogen, thereby enhancing nitrogen transformation and reutilization efficiency. Synergistic interactions between rice plants, aquatic animals, and microbial communities further accelerate nitrogen recycling: oxygen released from rice roots forms localized micro-oxic zones favorable for aerobic nitrifiers, whereas animal-derived carbon substrates provide electron donors for heterotrophic denitrifiers and anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing microbial groups[17−18]. Through these multiple pathways, nutrient redistribution is enhanced, and the risks of ammonia volatilization and nitrate leaching are reduced[19]. As a result, rice-aquatic animal co-culture is increasingly regarded as a promising nature-based strategy for limiting agricultural non-point-source pollution and achieving coordinated carbon–nitrogen cycling[20].

Despite advancements in system-level nitrogen budgeting, many studies have devoted limited attention to the rhizosphere-water-soil interface, a micro-scale zone that often functions as a biochemical hotspot[21,22]. This interface is characterized by steep oxygen gradients, abundant organic substrates, and intense microbial activity, all of which interact to drive rapid nitrogen transformations. Even subtle alterations to micro-environmental conditions can profoundly influence the direction and rate of nitrogen cycling[23,24]. However, the tiny spatial scale and heterogeneity of this interface pose significant technical obstacles for conventional sampling and monitoring methods, which are typically designed for bulk-soil resolution rather than fine-scale ecological gradients[25]. Previous work has indicated that aquatic animal bioturbation, root-derived oxygen, and organic carbon inputs act as primary regulators of microbial community composition and redox potential at this interface[26]. For instance, movement of fish and other aquatic organisms enhances oxygen transfer between the overlying water and soil matrix, thereby elevating redox potential (Eh), while organic acids and carbonaceous compounds released by rice roots serve as key substrates for heterotrophic microbial processes such as denitrification and nitrogen fixation[27]. Still, empirical results on these biological and chemical interactions, particularly their influence on gaseous nitrogen emissions, remain contradictory, suggesting that current conceptual models may underestimate the complexity of these interactions. The synergistic and spatiotemporally dynamic effects of these processes on gaseous nitrogen fluxes remain poorly quantified[28]. Moreover, microbial responses differ considerably depending on the species and density of aquatic animals and the specific management approaches applied, thus limiting the predictability and controllability of nitrogen cycling in such systems[29]. Collectively, these unresolved uncertainties underscore the importance of studying the micro-interface as a pivotal yet insufficiently characterized domain governing nitrogen transformations in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems.

To address these shortcomings, this review consolidates recent progress in understanding nitrogen cycling within rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, with particular attention to the rhizosphere-water-soil interface as a core zone of nitrogen transport and transformation. The review draws upon perspectives from microbial ecology, environmental chemistry, and ecological engineering to elucidate how root oxygen release, aquatic-animal bioturbation, and feed-derived carbon sources regulate redox conditions, enzyme activities, electron-transfer pathways, and microbial community structure. Moreover, advancements in in situ microprofiling, isotopic tracing, high-throughput omics, and sensor-based monitoring now provide unprecedented opportunities to investigate fine-scale processes that remain underrepresented in the literature. The review further outlines recent developments in understanding functional genes associated with nitrification, denitrification, nitrogen fixation, and ammonium oxidation. Finally, it identifies current gaps in monitoring methodologies, microbial functional analysis, and model integration, and discusses future directions for multi-scale and interdisciplinary research.

-

To obtain a comprehensive overview of the intellectual landscape and evolving research priorities related to nitrogen cycling in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using VOSviewer (v1.6.19). Unlike conventional literature reviews, which rely primarily on qualitative synthesis, the bibliometric approach enables visualization of structural linkages among publications through co-occurrence, clustering, and citation network algorithms. These analytical features allow VOSviewer to reveal not only the dominant research clusters but also the latent associations among scientific concepts that may otherwise remain obscured in manual analyses. The dataset used in this study was compiled from the Web of Science Core Collection on October 27, 2025, using a targeted search query: 'rice' AND 'nitrogen' AND ('animal' OR 'fish' OR 'shrimp' OR 'crayfish' OR 'crab' OR 'duck'). The search covered all publications from 2016 to 2025. After careful screening, 233 articles were identified as directly relevant and subsequently imported into VOSviewer for keyword co-occurrence assessment. A minimum threshold of five keyword occurrences was applied, yielding 103 keywords that formed six clusters, 1,729 linking relationships, and a total link strength of 2,795 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 presents the resulting keyword co-occurrence network, with node size representing total link strength and node color denoting the average publication year of the associated research. Warm-toned nodes reflect emerging topics, whereas thicker connecting lines indicate strong associative relationships among keywords. The dataset shows that, although publication numbers have remained generally stable over the past decade, the thematic focus has undergone pronounced shifts. Before 2021, research predominantly focused on crop yield, nutrient management, and macro-scale nutrient budgets in rice-based co-culture systems. Since 2021, however, attention has progressively shifted toward microbial community dynamics, nitrogen transformation pathways, and greenhouse gas emissions. Excluding the high-frequency terms 'rice' and 'nitrogen, ' the top-ranked keywords by total link strength include yield, growth, aquaculture, productivity, diversity, management, soil, culture, methane, and water. The total link strength, number of links, and occurrence frequency of these keywords are summarized in Table 1. These keywords highlight the multi-dimensional nature of nitrogen cycling studies, spanning agronomy, ecology, and biogeochemistry. Taken together, these patterns reveal not only temporal diversification in research directions but also the emergence of process-oriented investigations that extend beyond traditional agronomic outcomes.

Table 1. Top 12 keywords ranked by total link strength

Keyword Total link strength Links Occurrences Nitrogen 272 87 61 Yield 208 80 39 Growth 184 72 39 Aquaculture 164 65 31 Productivity 152 73 22 Diversity 136 64 30 Management 136 70 26 Soil 133 67 24 Culture 132 57 23 Rice 128 68 26 Methane 107 56 19 Water 97 55 19 Beyond descriptive mapping, the clustering configuration and temporal gradients reveal an ongoing conceptual transition in the field. Earlier studies largely centered on optimizing nitrogen fertilizer application, maintaining grain yield, and quantifying whole-system nitrogen budgets in rice-aquatic animal systems. More recent publications, however, show an increasing emphasis on micro-scale processes such as microbial functional gene expression, anaerobic ammonium oxidation, dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium, and nitrogen-driven greenhouse gas formation. This trend is consistent with global bibliometric evaluations of nutrient cycling in wetland soils, which similarly report a shift from 'black box' nitrogen accounting toward mechanistic, multi-process frameworks that better integrate microbial ecology with environmental chemistry[30,31]. Nevertheless, a critical examination of the literature indicates that many recent studies rely on short-term sampling, limited replication, or insufficient spatiotemporal resolution, thereby limiting the robustness of conclusions about microbially mediated nitrogen transformations. Thus, while the field is clearly transitioning toward mechanistic explanations, the methodological depth required to resolve these micro-scale processes remains underdeveloped.

Simultaneously, the heightened visibility of terms such as methane, greenhouse gas, and carbon–nitrogen coupling underscores increasing interest in the interconnections among multiple biogeochemical cycles within paddy ecosystems. Rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems provide a particularly compelling platform for such research due to the strong influence of animal bioturbation on soil aeration, root development, and oxygen diffusion. Numerous recent studies have shown that these modifications can reduce methane and nitrous oxide emissions and enhance the stability of soil-water interface processes[32]. However, a growing body of evidence also points out discrepancies among studies, especially regarding the magnitude of greenhouse gas mitigation effects, suggesting that system performance is susceptible to animal density, hydrological regimes, and organic matter inputs. This inconsistency signals the need for more standardized methodologies and cross-site synthesis to validate proposed mechanisms[33]. Building on these observations, the present review develops its central theme—'Promotion of nitrogen accumulation through enhanced soil-water interface activity'—as a conceptual foundation for understanding the micro-scale interactions that regulate nitrogen retention and loss suppression in co-culture systems. In summary, the bibliometric evolution, coupled with the rising emphasis on multi-element coupling, underscores the need for integrative, cross-scale frameworks that connect physical disturbance, redox restructuring, and microbial functional networks to system-level nitrogen outcomes.

-

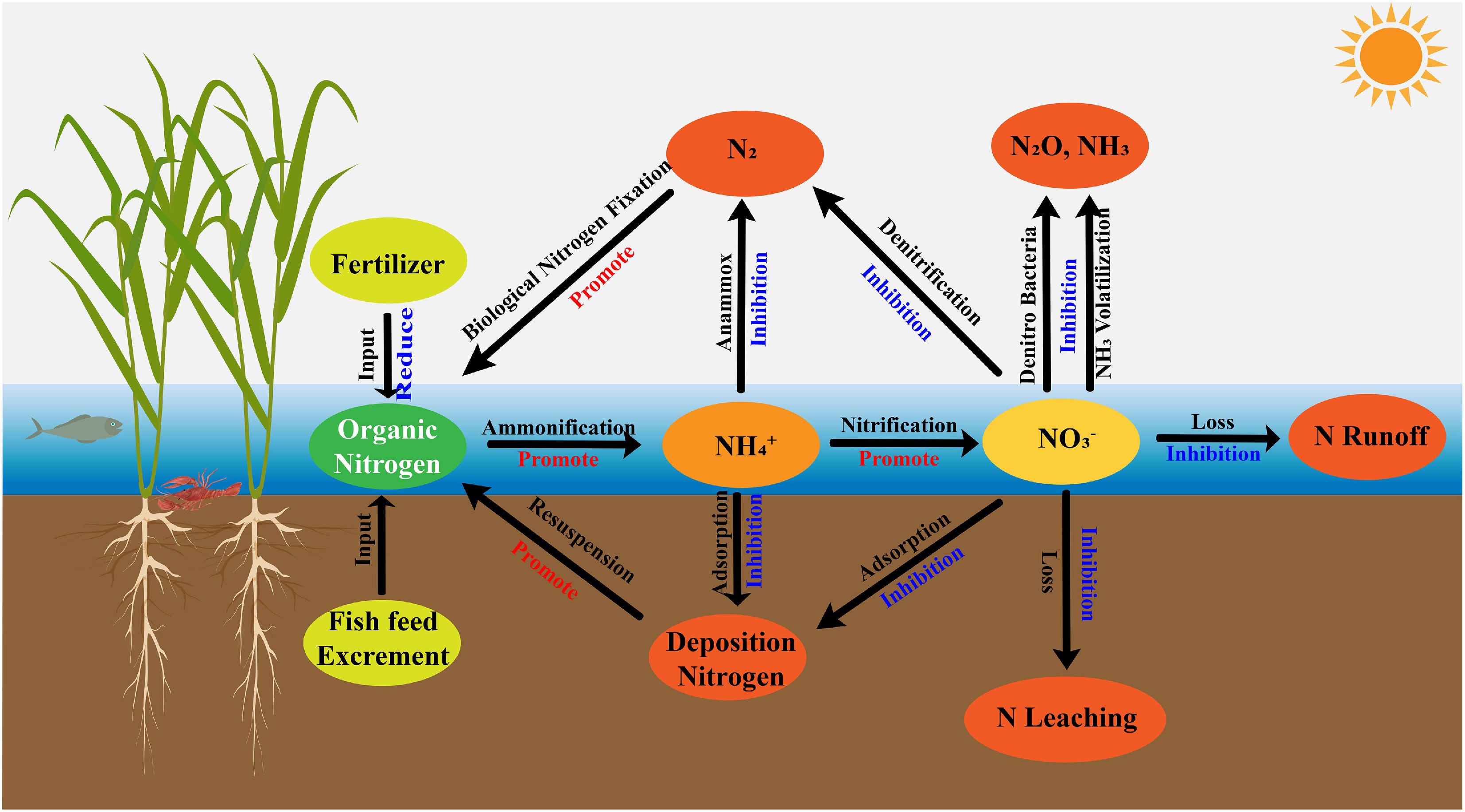

The rice-aquatic animal co-culture system is a representative land–water interactive eco-agricultural model that integrates two complementary functional units: a rice cultivation zone and an aquaculture zone. The spatial and functional coupling between these subsystems underpins a relatively continuous and closed nitrogen cycle within the broader ecosystem[10]. In the rice cultivation unit, rice plants act as the primary photosynthetic producers, fixing carbon and assimilating essential nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. In parallel, the aquaculture unit, typically stocked with fish, shrimp, crabs, or other aquatic organisms, relies not only on external feed inputs but also on the consumption of organic detritus and algae, thereby facilitating the internal recycling of nutrients and energy flows[34]. According to Qi et al.[35], such co-culture systems exhibit greater structural and functional complexity than conventional monoculture paddy fields, forming a tightly coupled web of energy transfer and material cycling. Zhang et al.[36] further observed that oxygen released from rice roots can generate micro-oxic zones that enhance nitrification, while the movement and foraging activities of aquatic animals disturb sediments and enhance water exchange, accelerating the transfer of oxygen and organic matter and promoting nitrogen transformations. Within this framework, nitrogen cycling processes are diverse and include ammonia volatilization, organic nitrogen mineralization, nitrification, denitrification, nitrogen fixation, and anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Ahmed et al.[37] emphasized that the high biodiversity characteristic of these integrated systems tends to strengthen nitrogen cycling capacity and confer considerable self-regulatory potential. Under conditions of excessive external nitrogen input, microorganisms and algae assimilate inorganic nitrogen from soil and water, while the bioturbation and feeding activities of aquatic animals stimulate nitrogen exchange between biota and sediments, increasing nitrogen retention and attenuating downstream nitrogen export[38,39].

The primary nitrogen sources in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems include chemical fertilizers, feed inputs, biological nitrogen fixation, and external water inflows such as irrigation and rainfall[40]. Feed residues and animal excreta introduce substantial amounts of organic and ammoniacal nitrogen; these compounds are decomposed and transformed by microbial communities and can subsequently be absorbed by rice roots, thereby improving overall nitrogen use efficiency. As a result, many studies report that co-culture systems can reduce chemical fertilizer application rates by approximately 20%–40% compared with monoculture rice systems[41]. Hu et al.[42] further noted that nitrogen-fixing bacteria and cyanobacteria in the rhizosphere contribute additional nitrogen through biological fixation, while irrigation and precipitation provide additional external inputs[43]. Nitrogen outputs, in contrast, occur primarily through plant uptake, animal assimilation, gaseous losses via denitrification and ammonia volatilization, surface runoff, and leaching from the soil profile[19]. Liu et al.[44] showed that the relatively deeper water layer and lower pH often found in co-culture fields can suppress ammonia volatilization. At the same time, animal disturbance and the accumulation of organic matter modify conditions at the soil-water interface, potentially partially inhibiting denitrification and thereby reducing gaseous nitrogen losses. Nitrogen released from the decomposition of feces, uneaten feed, and plant litter can be reused via root uptake, forming a 'feed-animal-soil-rice' loop that enhances nitrogen recycling and reduces dependence on external fertilizers[45]. However, although this nutrient cycle appears to be nearly 'closed', considerable heterogeneity across regions and management regimes suggests that the extent of fertilizer savings and nitrogen retention is strongly context-dependent and should not be generalized without rigorous consideration of local conditions.

Compared with the conventional monoculture rice systems, rice-aquatic animal co-culture generally demonstrates higher nitrogen use efficiency and significant ecological benefits[46]. Within these systems, plant nutrient uptake, animal feeding, and microbial nitrogen transformations jointly establish a coordinated nitrogen cycling network that supports nutrient balance and environmental sustainability[47]. Co-culture systems often possess more complex interfacial environments and more diverse microbial communities than monoculture paddies. In such environments, nitrogen fixation, nitrification, denitrification, and nitrate reduction processes are tightly coupled in both space and function, resulting in more stable and efficient nitrogen transformations. This coordinated cycling mechanism enhances nitrogen retention and substantially reduces nitrogen losses through volatilization, runoff, and leaching, thereby alleviating agricultural non-point source pollution[48]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that many of these conclusions are derived from short-term plot experiments or case studies; long-term, multi-site datasets are still scarce, and the resilience of these benefits under climate variability and intensifying management has yet to be thoroughly tested. Overall, the available evidence indicates that co-culture systems can improve nitrogen use efficiency and reduce nitrogen losses, but the strength and stability of these benefits depend on system design and management intensity.

Rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems also play an important role in regulating greenhouse gas emissions. In flooded paddy ecosystems, CH4 emissions are typically much higher than N2O emissions and constitute a dominant component of the overall greenhouse gas footprint of rice fields[49]. Bioturbation by aquatic animals enhances aeration and oxygen diffusion at the soil-water interface, reduces the extent of sediment anoxia, and stimulates methanotrophic microorganism activity, collectively suppressing CH4 production and accumulation[50]. This reduction in anaerobic microsites weakens the ecological advantage of methanogenic archaea and is widely regarded as one of the principal mechanisms by which co-culture systems mitigate CH4 emissions[51]. However, under conditions of high organic carbon loading from uneaten feed and animal excreta, increased substrate availability for methanogenesis can stimulate CH4 production and potentially create trade-offs between CH4 and N2O emissions[52]. Dai et al.[32] demonstrated that bioturbation by aquatic animals enhances oxygen diffusion at the soil-water interface and suppresses the production and accumulation of CH4 and N2O. Similarly, Du et al.[53] reported that increased organic carbon inputs can promote complete denitrification and enhance the reduction of N2O to N2. Field measurements indicate that N2O emissions from rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems are 2.4%–56% lower than those from conventional monoculture systems[33,54]. Rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems demonstrate synergistic effects on nutrient cycling and greenhouse gas mitigation. These systems optimize nitrogen transformation pathways, enhance nitrogen conversion efficiency, and represent a promising agroecosystem model that reconciles high agricultural productivity with ecological protection[55]. Even so, inconsistencies in field measurements and uncertainties regarding system-level trade-offs between CH4 and N2O underscore the need for more standardized experimental designs, longer monitoring periods, and integrated assessments that jointly consider nutrient cycling and greenhouse gas dynamics. The nitrogen cycling pathways within rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems are illustrated in Fig. 2.

-

The root system of rice plants penetrates extensively into the soil profile, and its growth, respiration, and exudation profoundly reshape the physical structure and moisture conditions of the surrounding soil. As roots expand into dense soil matrices, they create pores, cracks, and micro-channels that enhance porosity, hydraulic conductivity, and gaseous diffusivity[56]. At the same time, root-mediated alterations in the chemistry of rhizosphere pore water create preferential pathways that facilitate bidirectional exchange of solutes and gases between the soil matrix and the overlying floodwater[57]. The proliferation of root hairs, the development of root sheaths, and the stratification of rhizosphere microhabitats further intensify the spatial heterogeneity of pore-size distribution, soil moisture, and diffusion properties across depths and orientations. These characteristics collectively produce a micro-scale spatial configuration that is highly distinctive of paddy ecosystems and strongly determines their biogeochemical behavior[58].

In rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, the influence of aquatic animals introduces an additional layer of structural complexity to the soil-water interface. Behaviors such as burrowing, sediment reworking, grazing, and swimming disturb otherwise static sediment surfaces, promoting stronger coupling between soil and water and allowing oxygen and dissolved substances to reach deeper sediment horizons[59]. This bioturbation expands the redox transition zone, enhances organic matter resuspension, and redistributes fine particulates, thereby elevating interfacial reactivity and creating physicochemical conditions conducive to nitrogen transformations[23]. Furthermore, Sun et al.[60] showed that steep microscale gradients of oxygen, pH, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and ionic composition exist across the interface, forming a mosaic of micro-niches that support the coexistence and metabolic complementarity of diverse microbial guilds. Although these findings collectively underscore the importance of biological disturbance in shaping interface structure, most studies rely on short-term observations, leaving considerable uncertainty about the persistence of such modifications under long-term cultivation or high-intensity aquaculture practices.

The transport and transformation of oxygen and nitrogen compounds in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems are jointly controlled by pore architecture, sediment permeability, and the hydrodynamic environment of the overlying water[61]. Root-derived aerenchyma and rhizosphere channels enable both axial and radial diffusion of oxygen into surrounding soil, forming micro-oxic zones that play critical roles in nitrification and coupled transformation pathways[62]. In monoculture paddy fields, dissolved nitrogen species typically migrate downward with percolating water and undergo mineralization; however, in co-culture systems, animal-induced sediment disturbance and root oxygenation intensify interfacial activity, promoting nitrogen transport and internal nitrogen recycling[63]. This bidirectional material exchange arises from the interplay between molecular diffusion and convective flow, maintaining a dynamic equilibrium of oxygen and nitrogen species at the interface and providing a continuous substrate for microbial transformations[64]. Sediment texture also strongly regulates solute mobility: silty sediments with high porosity facilitate diffusion and infiltration, whereas compact clayey sediments create diffusion barriers that impede solute exchange[65,66]. In addition, localized disturbances by aquatic animals continually modify pore geometry and flow paths, generating microcirculation zones that significantly increase the efficiency of mass transfer across the interface[67]. Despite these advances, there remains limited consensus regarding the relative importance of physical versus biological drivers in regulating nitrogen mobility, especially given the diversity of animal species, stocking densities, and sediment types found in co-culture systems.

The structural and functional dynamics of the sediment–water interface are further modulated by environmental factors such as temperature and water level[31]. Deep and prolonged submergence buffers daily fluctuations in soil temperature, preventing overheating during summer months and maintaining stable thermal conditions that balance molecular motion and pore-water viscosity, thereby stabilizing gas and solute diffusion rates[68]. Thermal stability also reduces density-driven convection and limits temperature-induced disturbances at the interface, helping maintain sediment integrity and preserving diffusion gradients[69]. Water level similarly plays a pivotal role in regulating interface stability and exchange intensity. Co-culture systems are generally maintained at higher water levels and longer flooding durations, creating a stable hydraulic gradient and a low-energy hydrodynamic regime[24]. Extended submergence reduces the influence of external disturbances such as wind shear, rainfall, and inflow variability, lowering overall shear stress and decreasing the frequency of large-scale sediment resuspension. This stabilizes the interface while extending diffusion distances, making molecular diffusion the dominant mode of solute transport and minimizing turbulence-driven variability[70]. Moreover, lower water exchange frequency enhances nutrient retention and reduces nitrogen loss through drainage, thereby improving nutrient conservation and overall ecological stability[71,72]. However, recent studies highlight that prolonged flooding may also induce trade-offs such as increased methane production or reduced root oxygenation capacity, suggesting that the hydrological management of co-culture systems requires more refined optimization strategies. Overall, the structural characteristics and exchange mechanisms at the soil-water interface in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems reflect a complex interplay of plant roots, aquatic animal disturbance, sediment properties, and hydrological regimes. While current evidence clearly demonstrates that these interactions enhance nitrogen mobility and biogeochemical functionality, substantial uncertainties remain regarding their long-term stability, scalability, and sensitivity to intensified management and climate variability.

-

In rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, Eh at the soil-water interface functions as a central chemical indicator governing nitrogen mobility, speciation, and ultimate transformation outcomes. Unlike monoculture paddies where Eh patterns tend to be relatively predictable, the Eh landscape in co-culture systems is shaped by a multilayered interplay among rice roots, sediment constituents, and aquatic fauna, resulting in more complex and dynamically shifting gradients[73]. Oxygen diffusing from rice roots generates discrete oxidative microzones within the rhizosphere, whereas reduced compounds such as organic carbon, Fe2+, and Mn2+ rapidly consume oxygen, producing steep Eh gradients at the millimeter scale. Although alternating oxidized 'hotspots' and reduced 'patches' are common features of flooded soils, their spatial extent and temporal variability are markedly amplified in co-culture systems due to persistent animal disturbance and the presence of deeper water layers[74,75]. Together, these interactions create a heterogeneous and continually reorganized redox mosaic that distinguishes co-culture systems from typical rice monocultures[76,77]. However, despite a consensus on the presence of intensified redox heterogeneity, quantitative assessments of how animal species, stocking density, or sediment type individually modulate Eh remain limited, reflecting an important knowledge gap in recent literature. The major nitrogen loss pathways and their redox-mediated linkages at the soil–water interface in rice–aquatic animal co-culture systems are summarized in Fig. 3.

Daily oscillations in Eh are especially pronounced in these systems. During daylight hours, oxygen released by photosynthetic activity in rice and algae, combined with water-column mixing driven by the movement of aquatic animals, elevates dissolved oxygen levels and increases Eh near the soil surface. At night, photosynthesis ceases, and oxygen demand rises due to respiration and the decomposition of organic matter. However, continued swimming and sediment reworking by fish, shrimp, or crabs stimulate convective transport and gas exchange, maintaining a partial oxygen supply near the interface[78−81]. This combination of deep-water conditions and continuous biophysical disturbance produces rhythmic cycles of oxidation and reduction, generating a temporally overlapping and spatially diffuse redox environment characterized by non-steady-state fluctuations[82]. Such bidirectional oxygen inputs allow nitrification, anaerobic ammonium oxidation, and other redox-sensitive nitrogen processes to occur concurrently without external aeration[21].

Within these dynamic redox environments, nitrogen follows multiple interconnected transformation pathways involving frequent transitions among ammonium, nitrite, nitrate, and organic or gaseous forms[83]. The oxygenated upper microzone provides the dominant site for nitrification, where ammonium is sequentially oxidized to nitrite (NO2−) and then to nitrate (NO3−). Disturbance caused by aquatic animals enhances oxygen penetration and substrate supply, often resulting in higher nitrification rates relative to monoculture paddies[84]. As oxidized intermediates migrate downward, they encounter reduced sediment layers rich in organic carbon. In contrast to conventional paddies, where a significant proportion of nitrate is lost through gaseous emissions, co-culture systems enhance nitrate retention and recycling. In these systems, a portion of NO3− and NO2− is reabsorbed by rice roots, while another fraction is either reduced to ammonium or incorporated into organic nitrogen pools via heterotrophic pathways[85]. These redox-mediated reactions are tightly interconnected: nitrification generates oxidized substrates that support subsequent reduction processes, while reductive reactions regenerate plant-available nitrogen, forming a positive feedback loop. Although anammox does not dominate nitrogen removal in these systems, it complements heterotrophic denitrification by modulating nitrogen speciation and mitigating N2O accumulation[86]. Overall, the co-culture system achieves high nitrogen cycling efficiency and reduced nitrogen loss through a network of carbon-driven multi-pathway transformations[87].

Organic carbon acts as both an energy source for microbial metabolism and a major electron donor for nitrogen redox reactions within these systems[88]. Inputs from animal excreta, uneaten feed, and root exudates collectively generate a highly dynamic carbon pool at the interface. The spatial distribution of organic carbon influences reaction kinetics: animal-derived carbon often accumulates at the sediment surface, where it degrades rapidly, whereas root exudates provide a more gradual, sustained carbon supply along root channels. This dual carbon-supply mechanism offers both short-term reactivity and long-term electron availability[89,90]. The oxidation of organic carbon releases electrons, which are subsequently accepted by oxidized nitrogen species such as NO3− and NO2−, thereby facilitating nitrogen reduction and transformation[91]. The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N) strongly influences the terminal products of reduction pathways: high C/N ratios favor complete denitrification to N2, whereas low C/N ratios may promote the accumulation of intermediates such as N2O due to electron scarcity[92,93]. The high abundance of soluble organic carbon in co-culture systems reduces the likelihood of incomplete reduction, supporting sustained and reversible redox cycling across the interface[94]. Together, continuous organic carbon inputs and dynamic C/N regulation establish an electron-flow-centered energy loop that enables efficient nitrogen cycling and environmentally sustainable nitrogen transformation[95]. Such trade-offs remain an active area of investigation requiring more nuanced experimental designs. Overall, current research demonstrates that rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems exhibit a uniquely heterogeneous and dynamically shifting redox landscape that strongly facilitates nitrogen transformations. However, substantial uncertainties remain regarding how specific biological and environmental drivers regulate these processes over longer timescales, under variable management intensities, and across different sediment types. Future studies should integrate quantitative redox monitoring with high-resolution analyses of microbial and carbon dynamics to better evaluate the stability, efficiency, and environmental trade-offs of nitrogen cycling within these complex systems.

-

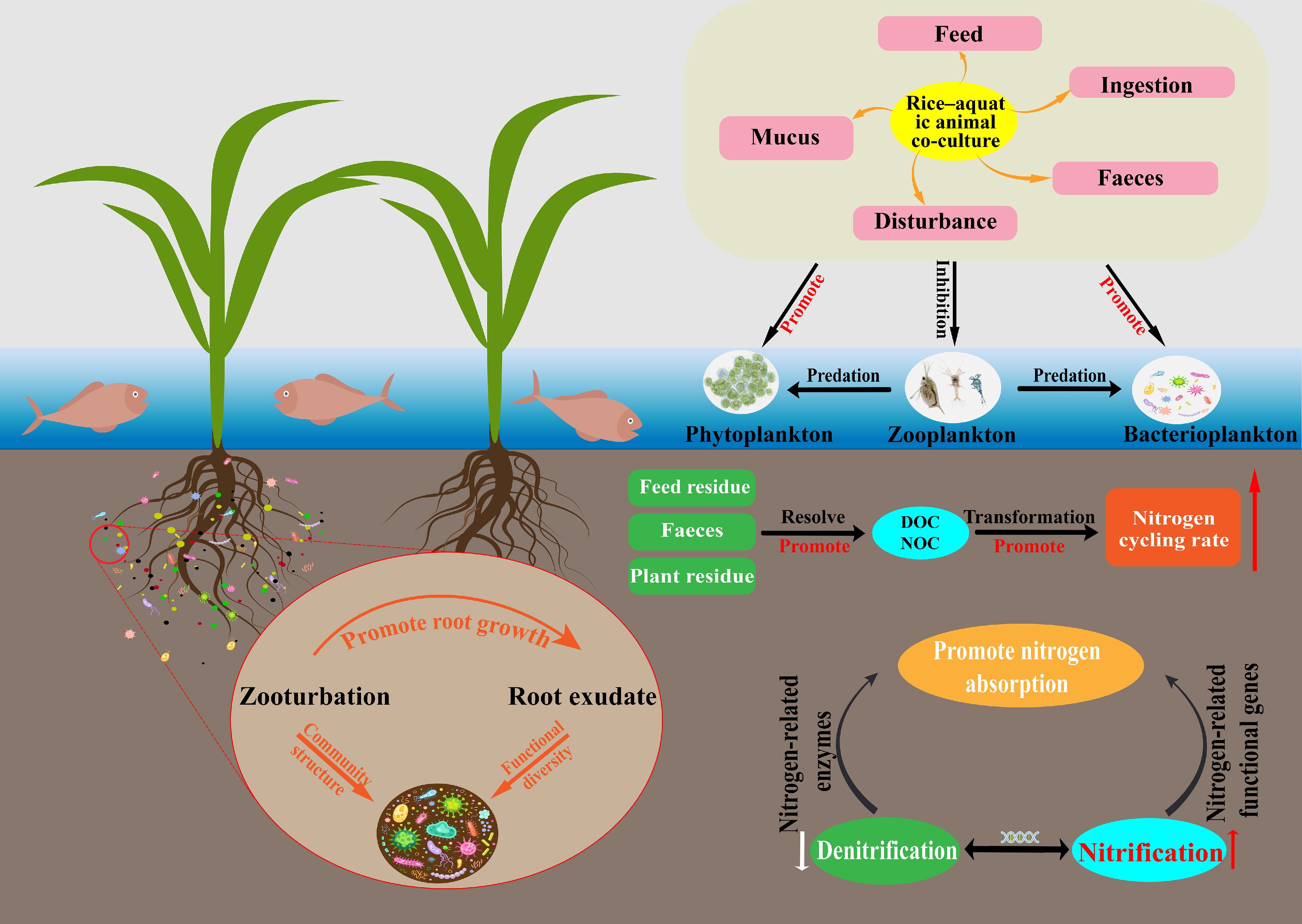

At the soil-water interface of rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, a highly intricate microbial assemblage develops, and its taxonomic composition, along with its metabolic potential, fundamentally shapes the pathways and efficiency of nitrogen cycling[96]. Wang et al.[97] reported that these co-culture systems exhibit markedly higher microbial richness, enhanced metabolic functional diversity, and greater modularity within microbial networks than conventional monoculture paddies. Such structural complexity also supports the persistence of keystone taxa that connect otherwise independent nitrogen transformation pathways. The formation of this microbially diverse environment is driven by the combined effects of root respiration, faunal bioturbation, and continuous organic carbon input, all of which generate heterogeneous microhabitats. Among the various functional groups, ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms constitute the principal drivers of nitrification[74]. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria as shown by Yang et al.[98], thrive mainly in oxygenated rhizosphere zones where they rapidly oxidize ammonium during brief oxygenation pulses. In contrast, ammonia-oxidizing archaea remain metabolically active under microoxic or mildly reducing conditions, which expands the range of redox environments suitable for nitrification. Denitrifying bacteria dominate reduced sediment layers and use diverse electron acceptors to sustain continuous nitrate reduction. Anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing and nitrogen-fixing microorganisms inhabit deeper strata, where they facilitate nitrogen re-transformation and biological nitrogen input, ultimately supporting internal nitrogen closure within the system[90].

Microbial communities within co-culture systems also display substantial functional redundancy and high network robustness, enabling multiple taxa to maintain overlapping metabolic roles and stabilize nitrogen transformations even when oxygen, carbon, or nitrogen availability fluctuates[99]. Bioturbation by aquatic animals further enhances this stability by promoting solute transport among microzones, generating alternating oxidized and reduced patches that vertically stratify microbial functional groups, and mitigating competitive exclusion[100]. Meanwhile, animal mucus and excreta both rich in soluble organic carbon, act as readily accessible substrates for heterotrophic microbes, fostering metabolic complementarity and facilitating niche diversification[101]. However, recent studies warn that excessive aquaculture intensification can trigger sediment eutrophication, reduce microbial diversity, and suppress critical nitrogen-transforming populations, ultimately diminishing the overall nitrogen cycling efficiency of the system[102]. Thus, moderate biological disturbance and ecologically rational stocking densities are essential to support micro-ecosystem stability and sustain the high performance of nitrogen transformation pathways[103]. A more critical issue is that current guidelines for 'optimal' disturbance thresholds remain poorly defined, as most empirical studies are system-specific and lack cross-site verification.

The efficiency of nitrogen cycling in these systems is not solely determined by microbial community structure but also by the activity of key metabolic enzymes and the physicochemical conditions that regulate their function[104]. Enzymes such as urease, ammonia monooxygenase, nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, and nitrous oxide reductase mediate the successive steps of nitrogen transformation at the interface. Urease hydrolyzes organic nitrogen to ammonium, providing substrates for nitrification; ammonia monooxygenase acts as the rate-limiting catalyst initiating nitrification and is profoundly influenced by root-derived oxygen and dissolved oxygen concentrations; nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase regulate the rate and completeness of denitrification, while nitrous oxide reductase determines the terminal reduction of nitrous oxide to dinitrogen gas, thereby modulating N2O emissions[105−107]. At the genetic level, functional genes associated with nitrogen cycling including amoA, nirK, nirS, nosZ, and nifH exhibit both high abundance and clear spatial heterogeneity in co-culture systems. The amoA shows elevated copy numbers within the rhizosphere, reflecting enhanced nitrification potential; nirS and nosZ are upregulated in deeper soil layers, indicating strong denitrification capacity; while nifH enrichment near zones of active animal disturbance suggests intensified biological nitrogen fixation[108]. Bioturbation enhances nutrient diffusion and substrate availability, stimulating metabolic gene activation and increasing overall nitrogen turnover[109].

Within co-culture systems, carbon–nitrogen coupling driven jointly by aquatic animal activity and rice root exudation serves as the central engine sustaining microbial metabolism at the interface[110]. Herlambang et al.[111] found that animal feces and feed residues provide highly degradable carbon and nitrogen substrates that rapidly mineralize into organic acids and ammonium. Combined with the more stable and prolonged carbon flux derived from root exudates, these inputs establish a dual carbon-supply mechanism that maintains long-term microbial energy flow. Root-derived carbon supports nitrification and mineralization under micro-oxic conditions, whereas animal-derived carbon promotes the formation of reduced microzones in upper sediment layers, creating spatial complementarity in carbon and nitrogen fluxes[43]. Bioturbation additionally restructures sediment pore networks, enhancing the diffusion of organic carbon and inorganic nitrogen and generating micro-scale 'reaction hotspots' characterized by simultaneous carbon oxidation and nitrogen reduction, thereby markedly increasing nitrogen transformation efficiency[84,112]. Furthermore, faunal disturbance reorganizes microbial niches, enabling nitrifiers, denitrifiers, and anammox bacteria to occupy stratified ecological layers, thereby reducing metabolic interference and facilitating cooperative nitrogen cycling[113]. Over extended periods, this biologically regulated carbon–nitrogen coupling mechanism not only accelerates nitrogen cycling but also enhances system-level energy efficiency, metabolic resilience, and ecological stability[114].

Given the central importance of microbial communities in mediating these processes, Table 2 synthesizes the major nitrogen-cycling microbial guilds identified in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, summarizing their functional genes, ecological niches, and specific roles within the nitrogen cycle. This table highlights how distinct guilds including ammonia oxidizers, nitrite oxidizers, denitrifiers, anammox bacteria, DNRA performers, nitrogen fixers, and multifunctional taxa, occupy complementary habitats and jointly sustain the multi-pathway nitrogen transformations observed in co-culture systems. The interrelationships among microbial community dynamics, enzymatic activities, and nitrogen transformation pathways in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems are illustrated in Fig. 4. Yet, long-term empirical evidence remains sparse, and current models seldom account for shifts in microbial interactions under climate variability or intensifying disturbances, underscoring the need for deeper mechanistic research. In summary, biological and enzymatic processes at the soil-water interface form an interconnected regulatory network governing nitrogen transformations in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems. Although substantial advances have been made in elucidating microbial diversity, enzyme functions, and carbon–nitrogen coupling, key uncertainties remain regarding the stability, scalability, and environmental sensitivity of these processes. Future work should integrate molecular analyses with real-time biochemical monitoring to better quantify functional redundancy, disturbance thresholds, and long-term metabolic adaptability within these complex ecological systems.

Table 2. Major nitrogen-cycling microbial guilds in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems

Microbial guild Key functional genes Dominant habitat Ecological function Characteristics in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems Representative references Ammonia-oxidizing archaea amoA Weakly oxidized microzones; surface sediment; rice rhizosphere Carry out ammonia oxidation under low-oxygen conditions and expand the spatial niche of nitrification Stable micro-oxic environments created by rice roots and aquatic animal bioturbation substantially increase the abundance of the amoA gene, making this group the dominant driver of ammonia oxidation and enhancing the conversion of ammonium to nitrite. [99] Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria amoA, hao Oxidized rhizosphere; root oxygen-release patches Initiate nitrification; respond rapidly to oxygen pulses; regulate nitrite supply In rice-crayfish and rice-fish systems, intensified redox gradients caused by root oxygen release and animal disturbance promote the enrichment of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Nitrospira-related clusters increase markedly and exhibit strong sensitivity to pH variation. [98] Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria nxrA, nxrB Rhizosphere micro-oxic layers; redox transition zones Oxidize nitrite to nitrate, completing the nitrification pathway and preventing nitrite toxicity In co-culture systems, both the abundance and diversity of nxrA and nxrB increase. Members of the genus Nitrospira accumulate in rhizosphere micro-oxic bands and in paddy-ditch transition areas, accelerating nitrite oxidation and reducing its toxic buildup. [108] Denitrifying bacteria narG, nirS, nirK,

norB, nosZReduced sediment layers; DOC-rich zones Reduce nitrate to nitrogen gas; complete N2O reduction through nosZ, mitigating greenhouse gas emissions Rice-crayfish co-culture systems strongly enhance the abundance of denitrification genes and overall denitrification capacity. Ditch zones show particularly high activity, contributing 40%–70% of system-level nitrate removal and greatly reducing N2O emissions. [115] Anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria hzsA, hzsB, hzo Deep anoxic sediment Remove nitrogen efficiently by converting ammonium and nitrite directly to nitrogen gas; complement heterotrophic denitrification In rice-crayfish co-culture systems, anaerobic ammonium oxidation constitutes one of the most important nitrogen removal pathways, accounting for 76%–97% of potential ammonium–nitrite conversion within irrigation–drainage units. Activity peaks during transplanting, accounting for approximately 70% of total nitrogen removal. [114] Microorganisms performing dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium nrfA High carbon-to-nitrogen ratio zones; strongly reduced microenvironments Retain nitrate within the system by reducing it to ammonium, sustaining internal nitrogen pools Feed residues and animal excreta stimulate the accumulation of nrfA-harboring microorganisms, promoting nitrate retention as ammonium and reducing dependency on external fertilizer inputs. [90] Nitrogen-fixing bacteria nifH Organic matter-rich hotspots; animal disturbance zones Introduce new reactive nitrogen into the ecosystem and reduce fertilizer dependence Rice-fish, rice-crayfish, and rice-snail co-culture modes consistently enhance the nifH gene abundance and nitrogen fixation potential, increasing endogenous nitrogen inputs, and reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers. [84] Urea-degrading bacteria ureC Rhizosphere; zones of fecal deposition Accelerate urea hydrolysis and increase the supply of readily available ammonium In rice-fish systems, urease activity is strongly enhanced, and ureC-bearing bacteria become enriched in the rhizosphere and surface sediment, promoting rapid urea decomposition and supplying ammonium for both rice and aquatic animals. [110] Microorganisms responsible for organic nitrogen mineralization chiA, apr, pepA Zones with accumulated residual feed; fecal hotspots; humus layer Degrade organic nitrogen compounds and enhance nitrogen regeneration The continuous input of residual feed and fecal matter increases degradable organic substrates, enriching organic nitrogen-mineralizing microbes and strengthening extracellular enzyme activities, thereby accelerating nitrogen regeneration in co-culture soils. [116] Iron-oxidizing bacteria cyc2 Oxidized rhizosphere layers Modify the structure of oxidized soil layers; influence oxygen diffusion and nitrification kinetics Aquatic animal disturbance enlarges redox transition zones, facilitating the aggregation of iron-oxidizing bacteria. These bacteria form iron plaques that alter micro-scale oxygen diffusion and regulate nitrification efficiency. [43] Multifunctional microbial taxa involved in plant growth promotion, nitrogen fixation, ammonia oxidation, denitrification, and nitrate reduction nif, amo, nirS,

nosZ, nrfA, etc.Rhizosphere hotspots; surface sediment Improve nitrogen availability; promote plant uptake; regulate nitrogen retention and loss Rice-fish and related co-culture systems enhance bacterial diversity and enrich multifunctional microbial groups, strengthening rhizosphere nitrogen fixation and denitrification, promoting plant growth, and enhancing overall nitrogen-cycling multifunctionality. [117] -

Research on nitrogen cycling regulation in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems has undergone a notable conceptual transition, shifting from traditional experience-based management toward coordinated multi-factor regulation supported by mechanistic insights and technological innovation[118]. Earlier investigations primarily evaluated how fertilization schemes and water-level manipulation influenced whole-system nitrogen retention and loss[119]. More recent studies, however, increasingly emphasize quantitative characterization of soil-water interface processes and the establishment of integrated regulatory frameworks. On one front, researchers have examined how adjustments in nitrogen application rate, timing, and chemical-to-biological nitrogen input ratios promote complementary interactions between synthetic fertilizers and biological nitrogen fixation[120]. On another front, the interplay among hydrological disturbance, animal-driven sediment mixing, and redox dynamics has gained considerable attention. Bioturbation by aquatic animals has emerged as a key mechanism, mediating oxygen exchange and shaping nitrogen migration across the interface in ways not captured by traditional monoculture models[121].

Given the intrinsic complexity of these systems, recent work has increasingly incorporated coupled biophysical models and multi-scale monitoring techniques to dynamically represent fluctuations in redox potential, dissolved nitrogen transport, and microbial community succession. These integrative approaches aim to identify dominant nitrogen transformation pathways, quantify their relative importance under varying environmental drivers, and ultimately reveal how biophysical processes interact to regulate system-level nitrogen cycling[122,123]. Collectively, such research reflects a paradigm shift from focusing on isolated biogeochemical processes to developing multi-factor, system-level regulatory frameworks that provide a foundation for precision nitrogen management in co-culture systems.

At present, optimization strategies are moving beyond single-species production models toward diversified, fine-tuned, and region-specific configurations that strengthen nitrogen cycling resilience by modifying system architecture and biological composition[124,125]. Multi-species co-culture has emerged as a promising approach for enhancing nitrogen cycling efficiency through ecological niche complementarity[126]. Compared with conventional rice-fish, rice-shrimp, rice-crab, or rice-duck systems, integrated multi-species arrangements more effectively utilize spatial and trophic resources, thereby improving nutrient conversion efficiency and stabilizing nitrogen flows[127]. Lokuhetti et al.[128] demonstrated that a rice-carp-tilapia system improved both rice grain yield and fish survival relative to the traditional rice-fish model. Concurrently, breeding and selection of high-performing rice varieties and aquatic animals have become a central focus for regulatory optimization[129]. Rice varieties with strong root oxygen-release capacity and high nitrogen uptake efficiency help stabilize oxidized microzones, while aquatic animals with low nitrogen excretion and high nitrogen utilization efficiency reduce nitrogen losses and enhance feed-to-nitrogen conversion[130,131].

Building on these developments, regional adaptation has increasingly become a focal direction for optimizing co-culture systems[82]. Researchers have observed that the ecological behavior of rice-aquatic animal systems changes noticeably across different climatic, hydrological, and soil conditions[132]. Because of this variability, adjusting the co-culture model and choosing species combinations that match local environments often leads to clear improvements in both overall productivity and nitrogen-use efficiency[34]. Recent optimization efforts, therefore, have tended to move away from uniform production models and toward more diversified and synergistic configurations that can better accommodate local ecological constraints, a shift that also aims to enhance nitrogen transformation efficiency, resource utilization, and ecological performance across a wide range of conditions[133,134].

To give a broader picture of how different co-culture arrangements perform, Table 3 brings together quantitative data from several production models. These comparisons illustrate how changes in species composition, fertilizer strategies, and biological interactions can affect nitrogen-use efficiency, economic outcomes, and environmental benefits. Taken together, the accumulated evidence suggests that nitrogen regulation in co-culture systems is gradually evolving toward multi-factor and region-specific optimization. Even so, several important gaps remain. For example, current models still struggle to represent the feedback loops linking animal disturbance, microbial processes, and hydrological variation. Likewise, the long-term stability of optimized systems has not been adequately tested, and the balance between productivity gains and ecological risks remains unclear. Moving forward, it will likely be essential to combine fine-scale monitoring with adaptive modeling and cross-regional comparisons, so that the regulatory frameworks guiding nitrogen management become more reliable and broadly applicable.

Table 3. Nitrogen utilization in different rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems

Culture model Nitrogen fertilizer application Nitrogen-use efficiency Economic benefits Environmental benefits Ref. Rice-duck-crayfish system Nitrogen fertilizer reduced by 50% Total nitrogen loss decreased by 24.3%; soil total nitrogen content increased by 8.54% to 28.37%; plant-available nitrogen increased by 6.93% to 22.72% Rice yield increased by 7.9%; net economic profit increased by 136.61% Reduced dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides; substantial enhancement of overall ecosystem services [135] Rice-fish system and rice-duck system Same nitrogen fertilizer rate as in rice monoculture The Rice-fish system reduced the total nitrogen loss by 4.3%; rice-duck system reduced total nitrogen loss by 6.5% Rice yield showed no significant difference; additional fish and duck biomass increased by 205.93 and 567.88 kg/ha, respectively Presence of ducks and fish reduced nitrogen loss through ammonia volatilization and nitrogen leaching pathways [136] Rice-fish system (yellow catfish) and rice-shrimp system (freshwater shrimp) Same nitrogen fertilizer rate as in rice monoculture Nitrogen-use efficiency increased relative to monoculture Rice grain yield remained unchanged; fish and shrimp biomass increased Rice-fish system reduced N2O by 85.6% and ammonia emissions by 26.0%; rice-shrimp system reduced N2O by 108.3% and ammonia emissions by 22.6% [126] Rice-crab system No chemical nitrogen fertilizer applied; nitrogen input from feed slightly exceeded fertilizer nitrogen input in monoculture 59.1% of the crab diet originated from naturally occurring organisms in the paddy field; rice plants utilized 7.6% of the nitrogen originating from aquatic animal feed Crab production increased by

730 kg/ha; rice yield slightly

increasedTotal nitrogen concentration in floodwater significantly decreased [118] Rice-carp system, rice-crab system, and rice-soft-shelled turtle system Same nitrogen fertilizer rate as in rice monoculture Apparent nitrogen-use efficiency significantly higher; 16.0% to 52.2% of

the aquatic animal diet originated from natural paddy biota; rice plants utilized13.0% to 35.1% of nitrogen is derived from aquatic animal feedIncreased rice yield; aquatic animal production increased by 520 to

2,570 kg/haReduced risk of agricultural non-point source pollution [137] Rice-carp system (Cyprinus carpio) and rice-shrimp system (Penaeus monodon) Same nitrogen fertilizer rate as in rice monoculture Nitrogen concentration in rice straw increased by 134% Rice yield unaffected; increased fish and shrimp biomass — [138] Rice–fish system (yellow finless eel and loach) Same nitrogen fertilizer rate as in rice monoculture Nitrogen-use efficiency improved compared with monoculture Economic value increased by 10.33% relative to rice monoculture Herbivorous insect abundance decreased by 24.70%; weed abundance, weed species richness, and weed biomass decreased by 67.62%, 62.01%, and 58.8%, respectively; invertebrate predator abundance increased by 19.48%; pesticide use decreased by 23.4% [139] Rice-crayfish system Nitrogen fertilizer reduced by 33.3% Nitrogen-use efficiency and nitrogen accumulation showed no significant difference compared with monoculture Rice yield remained unchanged; crayfish yield increased Reduced nitrogen surplus and lower risk of surface-runoff nitrogen pollution [140] Rice-fish system (Cyprinus carpio and Oreochromis niloticus) and rice-shrimp system (Macrobrachium species) Same nitrogen fertilizer rate as in rice monoculture The presence of aquatic animals enhanced nitrogen cycling processes Rice yield increased by 16%; additional aquatic animal biomass produced Water quality and soil fertility significantly improved [141] Rice-carp system 37% of nitrogen input originated from fertilizer; 63% from feed input Nitrogen-use efficiency showed no significant change Rice yield stable; fish production increased significantly Water nitrogen concentration reduced significantly [142] Rice-carp system and rice-tilapia system Urea application reduced by 220 kg/ha Nitrogen-use efficiency increased relative to monoculture Net economic profit increased by 50% to 60% — [143] Rice-fish system Same nitrogen fertilizer rate as in rice monoculture Nitrogen-use efficiency increased relative to monoculture Rice grain yield increased by 20%; fish biomass produced was 345 ± 92 kg/ha Overall, water quality remained similar to monoculture; however, densities of floating macrophytes, zooplankton, and benthic invertebrates declined [144] -

This review develops an integrated framework for understanding nitrogen cycling in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems by examining how physical disturbance, chemical restructuring, and biologically driven processes jointly shape nitrogen migration, transformation, and retention. Drawing on a broad set of empirical studies and micro-scale mechanistic evidence, this study proposes that enhanced interface activity is a central driver of nitrogen accumulation within these systems. This concept is unpacked as a multi-process synergy created by animal disturbance, oxygen released from rice roots, and the continuous influx of organic carbon. In practice, bioturbation markedly thins the diffusive boundary layer and accelerates the movement of oxygen, nitrogen species, and organic carbon across the interface. The micro-oxic zones formed by rice roots intersect with the reducing patches generated by animal activity, producing a layered redox mosaic that supports nitrification, denitrification, anaerobic ammonium oxidation, nitrogen fixation, and related pathways. At the same time, gradients of organic carbon availability regulate electron flow and reinforce the continuity and completeness of these transformations. By synthesizing findings on interface architecture, solute transport characteristics, the dynamics of Eh and DOC, and the regulatory roles of temperature and water level, this review emphasizes that the interface should not be viewed merely as a reaction zone but rather as a regulatory platform that determines both the direction and efficiency of nitrogen cycling. This cross-scale perspective extends beyond conventional whole-field nitrogen budgeting and provides a refined analytical lens for interpreting nitrogen dynamics in multi-species co-culture systems.

From the biological perspective, the review consolidates advances in the study of functional microbial guilds, key functional genes (including amoA, nirS, nosZ, and nifH), and enzyme-mediated reaction networks to clarify how microorganisms underpin nitrogen cycling stability at the interface. Table 2 illustrates that distinct microbial groups occupy complementary positions along redox gradients and collectively form a closed nitrogen cycle that links nitrification, denitrification, anaerobic ammonium oxidation, DNRA, and nitrogen fixation into a coordinated metabolic chain capable of maintaining nitrogen balance under fluctuating environmental conditions. The bibliometric analysis further reveals the evolution of research themes in this field from early emphases on yield and fertilizer use efficiency to a growing focus on interface microenvironments, microbial functional dynamics, and greenhouse-gas-related nitrogen pathways. Meanwhile, the enhanced nitrogen-cycling performance of multi-species co-culture models (e.g., rice-soft-shelled turtle-shrimp, rice-fish-duck) is systematically summarized and embedded within a unified framework that links interface processes, functional responses, and system-level ecological benefits. The evidence synthesized in this review demonstrates that the combined effects of animal disturbance, root-mediated regulation, and microbial feedback promote more frequent internal nitrogen cycling, reduce nitrogen losses, increase nitrogen-use efficiency, and lower greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, this review clarifies the principal material and energetic pathways that structure nitrogen cycling in rice-aquatic animal systems and establishes a multilayered, process-coupled theoretical foundation to advance ecological understanding and support the sustainable management of these integrated agroecosystems.

-

Research on nitrogen cycling in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems is gradually shifting from macro-scale nutrient balance assessments toward micro-scale process analysis and system integration modeling. Although substantial progress has been made in elucidating the coupling mechanisms among physical, chemical, and biological processes at the interface, a systematic quantification of spatiotemporal dynamics, energy-coupling efficiency, and the ecological regulatory potential of multi-process interactions remains limited. Future research should focus on integrating multi-omics approaches, in situ observation technologies, dynamic interface modeling, climate impact assessment, and ecological management optimization to deepen scientific understanding of nitrogen cycling and promote the development of precision regulation and sustainable management in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems.

(1) Integration of multi-omics approaches

Future studies should integrate metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to investigate molecular-level functional gene expression and metabolic flux variations in interface microorganisms. By combining microbial community data with physicochemical parameters, researchers can unravel the synergistic metabolic networks of nitrogen-transforming functional groups such as ammonia-oxidizing, denitrifying, anammox, and nitrogen-fixing bacteria and evaluate their responses to changes in Eh, DOC, and pH. Multi-omics integration will help elucidate the signal transduction and energy transfer pathways linking physical, chemical, and biological processes at the interface, providing molecular ecological evidence for constructing system-level nitrogen regulation frameworks.

(2) Advancement of in situ observation techniques

The interface reaction zones in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems exhibit pronounced micro-scale heterogeneity, making traditional sampling techniques insufficient to capture transient reaction dynamics. Future research should advance in situ analytical methods utilizing microelectrodes, optical fiber sensors, NanoSIMS, and confocal microscopy to achieve high-resolution monitoring of Eh, dissolved oxygen, and nitrogen species diffusion. Integrating spatial imaging with temporal sequence analysis will enable direct visualization of material migration and microbial spatial distributions, revealing the micro-scale coupling of nitrification, denitrification, and anammox processes. The development of in situ observation systems will establish a robust experimental foundation for understanding interface evolution and reaction zone differentiation.

(3) Development of dynamic interface nitrogen cycling models

Future studies should develop dynamic, data-driven models of interface nitrogen cycling that integrate multiple data sources. By combining high-resolution sensors, stable isotope tracing, and metabolic flux analysis, simultaneous quantification of material, energy, and electron fluxes across the interface can be achieved. Parameterizing the relationships among disturbance intensity, Eh fluctuations, and enzyme kinetics will facilitate the establishment of nonlinear dynamic frameworks that accurately represent multi-process coupling. These models will not only predict spatiotemporal patterns of nitrogen migration and transformation but also elucidate mechanisms of energy allocation and feedback stability under varying disturbance conditions, providing theoretical guidance for quantitative regulation and optimization of nitrogen cycling.

(4) Climate change impact assessment

Climate change poses significant risks and alters nitrogen cycling in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems. A systematic assessment of the effects of rising temperatures, elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations, and extreme precipitation events on interface structure and reaction dynamics is necessary. Global warming may increase the diffusion rates of oxygen and nitrogen compounds, while also potentially accelerating denitrification and N2O emissions. Similarly, extreme rainfall may modify hydrological regimes, influencing water levels, sediment disturbance frequencies, and redox balance. Combining controlled experiments with process-based modeling can elucidate the bidirectional effects of climate variables on dynamic Eh and microbial community responses, thereby providing scientific support for climate-resilient and sustainable operation of rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems.

(5) Integration of nitrogen cycling mechanisms with ecological management

Future research should bridge the gap between nitrogen cycling mechanisms and ecological management practices, developing targeted strategies for aquaculture and fertilization based on interface regulation. By precisely adjusting stocking density, water level, and fertilization frequency and formulation, disturbance intensity and Eh variation can be effectively managed to maintain a balance between nitrification and denitrification while minimizing nitrogen losses. Additionally, ecological engineering interventions, such as enhancing organic carbon input and microbial activity, can strengthen the system's self-purification and regeneration capacity. This integrated approach will offer scientific support for developing low-emission, high-efficiency rice-aquatic farming systems, achieving synergistic benefits in productivity and environmental protection.

(6) Long-term monitoring and model validation

Long-term, continuous observation is essential for validating and refining nitrogen cycling models in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems. Future efforts should establish regional experimental and monitoring networks that integrate sensor-based field observations, remote-sensing data assimilation, and environmental big-data analytics to track nitrogen migration, transformation, and emission processes at multiple spatial and temporal scales. Coupling experimental data with model simulations will enable the quantification of interannual variations and long-term stability of system performance, providing insights into the spatiotemporal evolution of nitrogen use efficiency and N2O emissions. This long-term perspective will bridge the gap between experimental understanding and management application, supporting the ecological optimization and regional scaling of rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Kui Li: conceptualization, investigation, resources, and writing − original draft; Chanyuan Qin: resources, data curation, and writing − review and editing; Ziheng Pang: resources, data curation, and writing − review and editing; Zhiyong Liu: formal analysis and visualization; Jin Zhou: formal analysis and visualization; Jianping He: resources, and writing − review and editing; Yelan Yu: resources, and writing − review and editing; Zeheng Li: resources, and writing − review and editing; Hua Wang: conceptualization, supervision, and funding acquisition. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, reviewed the results, and approved the final version.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42377319), the Department of Ecology and Environment of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. HBKYXM-2024017), the Key Technologies Research and Development Program, China (Grant No. 2021YFD1700804), the earmarked fund for HARS (Grant No. HARS-07), and the Hunan Provincial Postgraduate Research and Innovation Project (Grant Nos LXBZZ2024133 and CX20251065).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Co-culture enhances complete denitrification, N mineralization, and N recovery, lowering leaching, NH3 loss, and N2O.

Bioturbation by aquatic animals thins the diffusive boundary layer, enhancing nutrient cycling and improving N migration.

Periodic Eh and DOC shifts regulate nitrification, denitrification, and NH4+ oxidation, improving energy efficiency.

Co-culture boosts N-cycle microbial activity and gene expression, enabling coupled N transformations and closed cycling.

Disturbance–reaction–metabolism feedback improves N-use efficiency and strengthens the stability of co-culture systems.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li K, Qin C, Pang Z, Liu Z, Zhou J, et al. 2026. Promotion of nitrogen accumulation through enhanced soil-water interface activity in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems: a review. Nitrogen Cycling 2: e007 doi: 10.48130/nc-0025-0019

Promotion of nitrogen accumulation through enhanced soil-water interface activity in rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems: a review

- Received: 31 October 2025

- Revised: 07 December 2025

- Accepted: 23 December 2025

- Published online: 20 January 2026

Abstract: Rice-aquatic animal co-culture systems, as a representative ecological agriculture model, substantially reshape nitrogen migration, transformation, and retention through interactions among rice plants, floodwater, and soil interfaces. Although numerous studies have reported improved nitrogen-use efficiency and reduced environmental losses, the micro-scale regulatory mechanisms have not yet reached a unified understanding, and many key influencing factors remain insufficiently integrated. This review synthesizes current understanding of nitrogen cycling in such systems from physical, chemical, and biological perspectives. Physically, bioturbation by fish, shrimp, and crabs thins the diffusive boundary layer and enhances solute exchange, facilitating oxygen and nitrogen transport across the soil-water interface. Oxygen released from rice roots further forms micro-oxic zones that intersect with reduced patches created by animal disturbance, generating dynamic redox gradients. Chemically, periodic shifts in redox potential and dissolved organic carbon regulate the spatial dominance and rates of nitrification, denitrification, anaerobic ammonium oxidation, and nitrogen fixation. Abundant carbon inputs strengthen electron flow, enabling more complete nitrogen reduction and lowering N2O emissions. Biologically, ammonia-oxidizing, denitrifying, anammox, and nitrogen-fixing microorganisms establish complementary metabolic networks that drive efficient cycling among ammonium, nitrite, nitrate, and organic nitrogen, supporting sustained internal nitrogen regeneration. Enhanced interface activity ultimately increases nitrogen accumulation in rice plants, sediments, and microbial biomass, while reducing volatilization, leaching, and greenhouse gas emissions. Comparative studies indicate that optimizing water levels, animal density, and nitrogen inputs can enhance nitrogen-use efficiency by 20%–40% and improve ecosystem stability. This review highlights the pivotal role of interface processes in nitrogen cycling and provides scientific guidance for advancing efficient, low-emission, and sustainable rice-based agroecosystems.