-

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is a common complication of diabetes mellitus, and is a major cause of vision loss in the working-age population worldwide[1]. The severe stage of diabetic retinopathy includes vitreous hemorrhage (VH), tractional retinal detachment (TRD), and neovascular glaucoma, which is caused by the abnormal growth of new retinal blood vessels. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) is the routine treatment for diabetic patients, especially in eyes with vitreoretinal pathologies such as vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, and epiretinal membrane (ERM)[1−3]. However, whether the internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling was performed or not during the surgery remains controversial. As is known, the ILM comprises the basement membranes of Müller cells and is located on the vitreous surface of the retina. Peeling of the ILM at the posterior vitreous has been reported to reduce the frequency of macular edema in diabetic retinopathy patients. Meanwhile, macular pucker could be prevented after the ILM peeling in patients with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy[4−10]. Conversely, some drawbacks, including changes in the configuration and structure of the macula and retinal thinning, have been reported, as ILM peeling may damage Müller cells, and other cells[11,12].

The leading cause of vision loss in patients with diabetic retinopathy is diabetic macular edema (DME), even if the vitreous hemorrhage was removed after the vitrectomy[13]. Apart from PPV, several treatments have been proposed to manage DME, including focal laser photocoagulation[14,15], photobiomodulation treatment[16], intravitreal or subtenon injection of triamcinolone[17], sustained-release corticosteroids implant[18], and intravitreal injection (IVI) of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)[19,20]. Currently, anti-VEGF is considered the first-line treatment of choice for DME, but the cost of the treatment is high, making it unaffordable for many people. Recently, vitrectomy combined with ILM peeling has shown favorable anatomical and functional outcomes. Peeling of the ILM has been reported to accelerate the resolution of hard exudates in DME patients and reduce the incidence of secondary ERM development[21,22].

Thus, it was hypothesized that PPV, combined with ILM peeling, may facilitate the resolution of DME and represents a favorable treatment for DME with vitreous hemorrhage in patients with PDR. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the one-year anatomical and functional outcomes of DME with vitreous hemorrhage managed by PPV with ILM peeling and compare them with those managed PPV without ILM peeling.

-

This was a retrospective study approved by the Institutional Review Board of Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine in January 2023 and conducted in compliance with guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants in this study provided written informed consent. Patients who underwent PPV for PDR at Eye Center, the Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, from October 2017 to July 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. Inclusion criteria were as follows: PDR patients with the presence of vitreous hemorrhage and/or epiretinal membrane (ERM) and/or macular-involved tractional retinal detachment; a history of PPV surgery; postoperative follow-up period of >12 months. Since this was a retrospective observational study, all data were derived from anonymized medical records that existed prior to the conception of the research protocol. According to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines, clinical trial registration was not required as this study did not involve any prospective intervention or assignment of participants.

Eyes fulfilling the aforementioned criteria were divided into two groups. Group A: The patients underwent PPV with ILM peeling. Group B: The patients underwent PPV without ILM peeling. Some of the patients also received combined phacoemulsification and intraocular lens (IOL) implantation surgery if the cataract met the operation indication at the same time. The following data were extracted from medical records for each patient, including demographic data (gender, age, and systemic disease), diagnosis, surgical records, panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) completion or not before the surgery, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), and intraocular pressure (IOP) before and after surgery, the times of postoperative anti-VEGF injection, and other relevant parameters. Postoperative BCVA at 12 months was marked.

A standard three-port, 23-gauge PPV was performed by two retinal specialists (JM and YW). The non-contact wide-angle vitreous surgery system was used during the PPV surgery. The corneal entry site was sutured with Nylon 10–0, and the scleral wound was repaired with Vicryl 8–0. If the view for performing the PPV surgery was obstructed by the age-related cataract, a phacoemulsification and IOL implantation procedure was also done during the surgery. Firstly, the vitreous hemorrhage was removed. Then epiretinal proliferative membranes of PDR patients were also separated and eliminated. The ILM was also peeled in the meantime if there was the ERM or macular pucker. The ILM peeling was standardized. Indocyanine green (ICG) was applied to enhance ILM visualization, and an initial flap was created at the edge of the macular area. Then, the ILM was peeled circumferentially or radially in a tangential direction. PRP was completed during the operation if the PRP was not finished before the surgery. Retinal holes were secured by endolaser photocoagulation. Either gas or silicone oil was used for the intraocular tamponade. The patients were reviewed at regular intervals postoperatively by the retinal experts of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Anti-VEGF therapy was regularly carried out 3−7 d before the PPV surgery. If DME occurs after surgery, we also routinely recommend anti-VEGF therapy. Another surgery was performed if the recurrent vitreous hemorrhage was not absorbed more than one month and vision-impairing macular ERM was found during the follow-up.

The decimal visual acuities were converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) units for statistical analysis. LogMAR values of 2.6, 2.7, 2.8, and 2.9 were assigned to visual acuity of count fingers, hand motion, light perception, and no light perception, respectively[23]. The sample size was determined using PASS 2021 (v21.0.3, NCSS LLC, Utah, USA). In the present study, the primary outcome was the change in postoperative visual acuity (logMAR) from baseline. A prior study reported a mean change of −0.05 ± 0.14 in the ILM peeling group, and −0.19 ± 0.27 in the non-peeling group[24]. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05, and the statistical power at 0.80. PASS estimated that a minimum total of 78 patients would be required to detect this difference with the specified power. Continuous variables were presented as means ± SDs, or medians and quartiles, as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 24.0). For numerical data, the t-test was used if the variables were normally distributed; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Frequency differences in categorical data were compared using the chi-squared test. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to assess the relationship between postoperative parameters and potential risk factors. The odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using a 95% confidence interval. In the multivariate logistic regression analyses, the ILM peeling was the primary variable, and all models were adjusted for age, gender (basic demographic confounders), and preoperative PRP, which may affect postoperative visual outcomes. Preoperative visual acuity was not included because most patients had very poor vision (hand motion or light perception), preventing precise quantification. Combined cataract surgery was also considered, but the literature suggests it does not significantly affect postoperative vision or most complications[25].

-

According to the eligibility criteria described in the methods, a total of 88 eyes from 88 patients were enrolled in the present study. There were 44 eyes in group A with ILM peeling, and 44 in group B without ILM peeling. The baseline clinical characteristics of all patients are listed in Table 1. There were no significant differences in patients' age, sex, BCVA, percentage of PRP completion, and IOP between the two groups before surgery. The data revealed no significant difference between the two groups with regard to the incidence of VH, VH + TRD, and VH + TRD + ERM. In contrast, a significant difference was noted in the presence of VH + ERM.

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients.

Group A with

ILM peeling

(n = 44)Group B without ILM peeling

(n = 44)p value Age (years)* 50.66 ± 11.27 52.41 ± 11.12 0.465† Sex (Male: Female) 26:18 27:17 0.828‡ Preoperative logMAR BCVA (Snellen equivalent)# 2.6 (1.2, 2.7), FC 2.6 (1.5, 2.7), FC 0.844§ Preoperative IOP, mmHg# 13.0 (12.0, 16.4) 14.0 (11.5, 18.3) 0.549§ Preoperative PRP (%) 14 (31.82%) 15 (34.09%) 0.821‡ Number and rate of pathologies VH 18 (40.91%) 19 (43.18%) 0.829‡ VH + TRD 19 (43.18%) 25 (56.82%) 0.201‡ VH + ERM 7 (15.91%) 0 0.018& VH + TRD + ERM 0 0 NA * Mean ± SD. # Medians and quartiles. ILM: internal limiting membrane; logMAR: logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution; BCVA: best-corrected visual acuity; IOP: intraocular pressure; PRP: panretinal photocoagulation; VH: vitreous hemorrhage; TRD: tractional retinal detachment; ERM: epiretinal membrane; FC: finger count; NA: not available; SD: standard deviation. † t-test. ‡ Chi-square test. § Mann-Whitney U test. & Fisher's exact test. Compared with preoperative logMAR BCVA 2.6 (interquartile range, 1.4–2.7) of all patients, the postoperative logMAR BCVA of all patients was 1.3 (interquartile range, 0.7−2.6), which was statistically significantly different (p < 0.001). The median postoperative logMAR BCVA was 0.8 (interquartile range, 0.5−1.3) in group A with ILM peeling, and 1.7 (interquartile range, 1.0−2.6) in group B without ILM peeling. Both the ILM peeling and ILM non-peeling groups had significant improvement statistically (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively) compared to preoperative BCVA. The comparison of visual outcomes at 12 months follow-up between the two groups is shown in Table 2. At 12 months follow-up, in the ILM peeling group, the logMAR BCVA was statistically better than in the ILM non-peeling group (p < 0.001). Group A with ILM peeling, had better visual improvement of −1.18 (interquartile range, −1.7 to −0.2) logMAR compared to group B without ILM peeling of −0.1 (interquartile range, −1.3 to 0) logMAR (p = 0.003). In the ILM peeling group, the BCVA improved in 37 patients (37/44, 84.1%) while only 24 patients (24/44, 54.5%) in the ILM non-peeling group, which was a significant difference (p < 0.01). The proportion of patients with a BCVA > 0.52 logMAR (20/67 Snellen equivalents) at the 12-month follow-up showed no significant difference between the two groups.

Table 2. Comparison of visual outcomes at 12 month follow-ups.

Group A with

ILM peeling

(n = 44)Group B without

ILM peeling

(n = 44)p value Postoperative logMAR BCVA (Snellen equivalent)# 0.8 (0.5, 1.3), 20/400 1.7 (1.0, 2.6), 20/1000 < 0.001§ The improvement of

logMAR BCVA#−1.18 (−1.7, −0.2) −0.1 (−1.3, 0) 0.003§ The improvement of BCVA (%) 37/44 (84.1%) 24/44 (54.5%) < 0.01‡ Postoperative BCVA > 0.52 logMAR (20/67 Snellen equivalents) (%) 9/44 (20.5%) 4/44 (9.1%) 0.133‡ # medians and quartiles. logMAR: logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution; BCVA: best-corrected visual acuity; ‡ Chi-square test. § Mann-Whitney U test. The postoperative details for both groups are presented in Tables 3, 4. Early vitreous hemorrhage, secondary macular ERM and IOP elevation were the main postoperative complications. Both groups did not differ in terms of the postoperative early vitreous hemorrhage, and IOP for each time period. However, compared with patients in the ILM peeling group, patients in the ILM non-peeling group had a higher incidence of secondary ERM (47.7% vs 4.5%; p < 0.001). Some patients of both groups received anti-VEGF therapy within one year after the surgery. 10 patients in the ILM peeling group (10/44, 22.7%) and 16 patients in the ILM non-peeling group (16/44, 36.4%) underwent anti-VEGF therapy (p = 0.161). Of those, nine patients in the ILM peeling group (9/44, 20.5%), and 10 patients in the ILM non-peeling group (10/44, 22.7%) received one injection for anti-VEGF (p = 0.568). One patient in the ILM peeling group (1/44, 2.3%), and six patients in the ILM non-peeling group (6/44, 13.6%) received two or more treatments of anti-VEGF therapy (p = 0.049). In addition, one patient in the ILM peeling group (1/44, 2.3%), and nine patients in the ILM non-peeling group (9/44, 20.5%) underwent the second PPV surgery (p = 0.007).

Table 3. Postoperative complications of patients.

Group A with

ILM peeling

(n = 44)Group B without

ILM peeling

(n = 44)p value Secondary macular ERM (%) 2 (4.5%) 21 (47.7%) < 0.001‡ Early vitreous hemorrhage (%) 6 (13.6%) 10 (22.7%) 0.269‡ IOP elevation (%) 5 (11.4%) 11 (25.0%) 0.097‡ ERM: epiretinal membrane. IOP: intraocular pressure; ‡ Chi-square test. Table 4. Comparison of postoperative characteristics for patients.

Group A with

ILM peeling

(n = 44)Group B without

ILM peeling

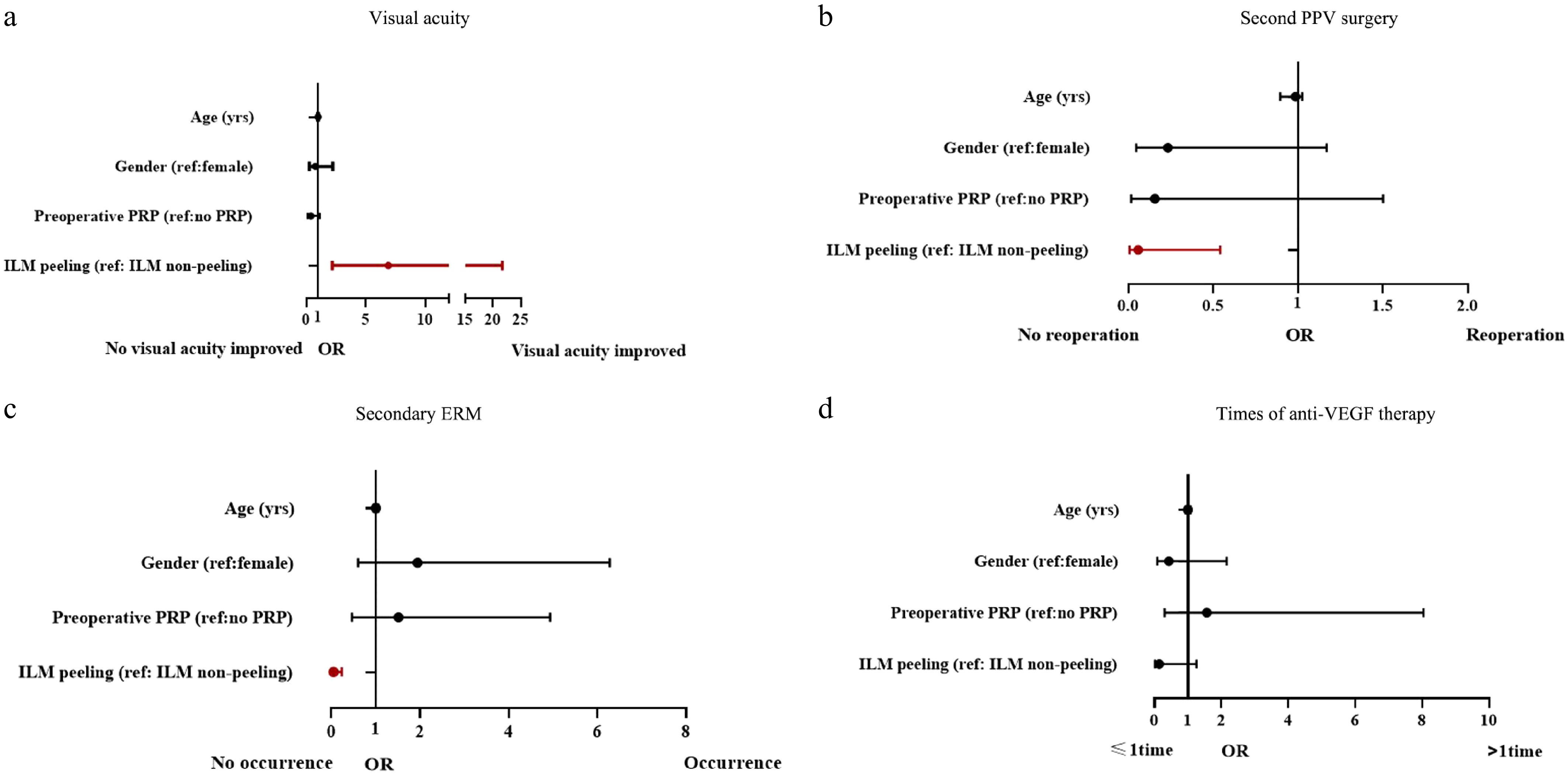

(n = 44)p value Anti-VEGF injection (%) One or more times 10 (22.7%) 16 (36.4%) 0.161‡ One time 9 (20.5%) 10 (22.7%) 0.568‡ Two or more times 1 (2.3%) 6 (13.6%) 0.049‡ Postoperative IOP, mmHg# One week postoperatively 15.5 (11.6, 18.4) 15.0 (13.0, 18.7) 0.726§ One month postoperatively 14.8 (12.0, 16.5) 13.5 (12.0, 16.9) 0.604§ Six months postoperatively 15.5 (13.0, 17.7) 15.3 (13.0, 18.0) 0.805§ Another PPV surgery (%) 1 (2.3%) 9 (20.5%) 0.007‡ # Medians and quartiles. IOP: intraocular pressure. ‡ Chi-square test. § Mann-Whitney U test. In the multivariate logistic regression model (Table 5, Fig. 1), the ILM peeling was significantly correlated with better visual acuity (OR = 6.90 [2.20–21.69], p < 0.001), secondary ERM (OR = 0.05 [0.01–0.24], p < 0.001), and second PPV surgery (OR = 0.06 [0.01–0.54], p = 0.013). But the correlation between the ILM peeling and two or more treatments of anti-VEGF therapy did not reach statistical significance (OR = 0.14 [0.02–1.26], p = 0.08).

Table 5. Multivariate logistic regression for postoperative parameters.

Postoperative parameters Factor OR, 95%CI p value Second PPV surgery Age 0.96 (0.90–1.03) 0.212 Gender 0.23 (0.05–1.17) 0.077 Preoperative PRP 0.16 (0.02–1.50) 0.108 ILM peeling 0.06 (0.01–0.54) 0.013 Visual acuity Age 0.98 (0.94–1.03) 0.453 Gender 0.76 (0.26–2.23) 0.623 Preoperative PRP 0.39 (0.13–1.14) 0.085 ILM peeling 6.90 (2.20–21.69) < 0.001 Secondary ERM Age 1.00 (0.95–1.06) 0.894 Gender 1.95 (0.60–6.28) 0.266 Preoperative PRP 1.51 (0.46–4.93) 0.493 ILM peeling 0.05 (0.01–0.24) < 0.001 Times of anti-VEGF therapy Age 1.00 (0.93–1.08) 0.979 Gender 0.43 (0.09–2.16) 0.304 Preoperative PRP 1.57 (0.31–8.04) 0.591 ILM peeling 0.14 (0.02–1.26) 0.08 ILM: internal limiting membrane; PPV: pars plana vitrectomy; PRP: panretinal photocoagulation; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval -

Vitrectomy is now routine therapy for patients with advanced PDR, including vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, and ERM[26]. Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of anti-VEGF before and after surgery. Increasing surgeons would recommend anti-VEGF therapy 3–7 d before the vitrectomy for the DR patients[27], which is also a common practice in China[28]. However, no consensus has been reached on the ILM peeling during vitrectomy. As is known, the incidence of macular edema may be lower with ILM peeling during the vitrectomy surgery. However, the thinning of the retina and destruction of microstructure in the retinal nerve fiber layer are the main disadvantages of this procedure[11]. There is also concern that ILM peeling may affect the final BCVA of the PDR patients. However, in consideration of possible favorable anatomical and functional outcomes and reduced frequency of DME, vitrectomy combined with ILM peeling could be an option for diabetic retinopathy patients. However, previous research primarily concentrated on patients with persistent DME, and assessed the impact of ILM peeling. There is limited investigation into the effectiveness of PPV with ILM removal in patients with PDR[29]. Rush et al. found the ILM peeling group had better visual acuity, a lower incidence of receiving one or more DME treatments in PDR patients[29]. The present findings aligned with their results, albeit with an extended follow-up duration.

In this study, we reviewed medical records of patients who received PPV combined with ILM peeling or not for PDR in our center from October 2017 to July 2022. To confirm the effect of ILM peeling for diabetic retinopathy, the patients were divided into two groups depending on ILM peeling or not. The distribution and rates of the pathologies in the two groups were also considered essentially identical. Predictably, there's no difference in the IOP elevation and vitreous hemorrhages before and after surgery between the two groups. Most patients had anti-VEGF therapy after the surgery in both groups. More patients had two more injections in the group without ILM peeling. Conversely, only one patient got second anti-VEGF therapy in the ILM peeling group. As is known, the DME always persisted, though the vitreous hemorrhage was removed by the surgery. The patients warrant further anti-VEGF therapy in case of the vision-impairment by DME. It is reported that ILM peeling will cause retina thinning and reduce the incidence of DME after surgery[30−33]. That explained that the ILM peeling group needs fewer injections for anti-VEGF. Some people may worry that the BCVA would worsen because of the retina thinning caused by ILM peeling. Interestingly, the present results found that 84.1% patients showed vision improvement after the ILM peeling procedure, compared to 54.5% in the group without ILM peeling. It seemed that ILM peeling was safe and effective for the PDR patients. Although the preoperative visual acuity of the ILM peeling group was slightly better than that of the non-ILM peeling group, there was no statistical difference. In addition, the preoperative visual acuity of both groups of patients was very poor (20/2500 vs 20/3333), and this difference was almost negligible. So we believe the difference in preoperative visual acuity between the two groups did not play a role in the postoperative results.

The IOP elevation was often seen in the PDR patients after vitrectomy. There were multiple factors, including hemorrhages in the anterior chamber, pupillary block by the intraocular lens, topical treatment of dexamethasone, neovascular glaucoma, and so on[34,35]. No statistical difference could be found in the two groups regardless of whether ILM peeling was performed or not. Similarly, there was no difference for the early hemorrhages after surgery. That means ILM peeling had nothing to do with the IOP elevation and vitreous hemorrhages in the present study. The incidence of ERM was lower in the ILM peeling group. Only two out of 44 patients were found to be inflicted with ERM after PPV surgery. In contrast, 21 out of 44 patients were found to have suffered ERM without ILM peeling. It is very important that ILM peeling not only removes the ILM, but also helps to find the vitreous cortex or ERM above the retinal surface. Achieving total posterior vitreous detachment is the most critical step in PPV surgery for the PDR patients.

Only a few PDR patients require a second surgery due to unresolvable vitreous hemorrhages, epiretinal membrane, or retinal detachment[36−38]. Early vitreous hemorrhages post-surgery will disappear quickly, usually after one or two weeks. The patients will be referred to receive air-fluid exchange or PPV surgery again with unresolvable vitreous hemorrhages for more than one month[39]. Sometimes anti-VEGF therapy was also an option for patients who refused to undergo a second surgery, especially for those patients warrant additional photocoagulation. Anti-VEGF therapy will reduce the incidence of neovascular glaucoma, in addition to expediting the absorbance of the vitreous hemorrhages[40]. However, from the present results, there is no statistical difference for early vitreous hemorrhages regardless of whether the ILM peeling was performed or not. Some patients underwent a second surgery because of the metamorphopsia or refractory DME afflicted by ERM[41]. Based on the present data, the ILM peeling group had a lower reoperation rate than the non-ILM peeling group. The ILM peeling procedure had more favorable effects in PDR patients.

The ILM is the structural boundary between the retina and the vitreous, with the collagenous vitreous cortex on one side, and the Müller cells' endfeet on the other. As to why ILM peeling could accelerate the resolution of the macular edema and avoid the formation of the ERM, there are several possible explanations. First, after the initial surgical posterior vitreous separation, residual cortical vitreous may remain attached to the macula and contribute to the subsequent edema. In addition, the ILM of patients with diabetes is thickened, and various cells are adhered to the vitreous side of the ILM[42,43]. Therefore, the removal of residual cortical vitreous and tangential traction exerted by the ILM may have a beneficial effect in PDR patients. Second, it is well known that VEGF is produced within Müller cells[44], and a previous study revealed that the ILM peeling could cause the rupture of Müller cells at their basal membrane side[45]. Thus, there is a possibility that this disrupts Müller cell physiology in some way, possibly causing decreased VEGF synthesis, and accelerating the edema resorption process. Third, since the ILM serves as a scaffold for proliferating astrocytes, its removal could inhibit their proliferation and prevent ERM formation[4].

There were some limitations in the present study. First, the weakness of this study was the retrospective study design and small sample size. Second, the patients included in this study were diverse, vitreous hemorrhage and/or epiretinal membrane (ERM) and/or macular-involved tractional retinal detachment, and the decision to perform ILM peeling may have been influenced by baseline patient conditions, introducing potential selection bias. Third, due to practical limitations, some potential confounders (e.g., diabetes duration, disease stage) could not be included in the multivariate logistic regression analyses. Fourth, the lack of long-term follow-up on retinal thickness changes precluded assessment of the potential long-term effects of ILM peeling on retinal microstructure.

In conclusion, in the present study, PPV with ILM peeling appeared to be more effective for PDR patients. It contributed to better visual acuity, lower incidence of receiving anti-VEGF therapy, presence of secondary ERM, and undergoing second PPV surgery, compared with the ILM non-peeling group.

Project supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant No. LY21H120002).

-

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Ethics approval number: 2023(0048); Date: January 12, 2023.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: methodology, formal analysis, data curation: Wu S; data analysis: Wu S, Zeng Y; investigation: Ye P, Wang Y, Zhang L, Su Z, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Fang X; writing − original draft preparation: Wu S, Ma J; writing − review and editing: Zhang X, Ma J; supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: Ma J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Shijing Wu, Yiyun Zeng

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wu S, Zeng Y, Ye P, Wang Y, Zhang L, et al. 2026. Effect of vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling on the patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Visual Neuroscience 43: e001 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0029

Effect of vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling on the patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- Received: 28 June 2025

- Revised: 07 November 2025

- Accepted: 19 November 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: This study evaluated the effect of internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling during pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). A retrospective analysis was conducted on the medical records of 88 PDR patients, 88 eyes, who underwent PPV for vitreous hemorrhage and/or epiretinal membrane (ERM) and/or macular-involved tractional retinal detachment. Patients were divided into two groups: Group A (PPV with ILM peeling), and Group B (PPV without ILM peeling), with a minimum 12-month follow-up. Outcomes were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression. All models were adjusted for age, gender (basic demographic confounders), and preoperative PRP in the multivariate analyses. Both groups showed significant BCVA improvement, with the peeling group demonstrating better final visual acuity (p < 0.001). The peeling group also had lower incidences of anti-VEGF therapy (p < 0.05), secondary ERM (p < 0.001), and repeat PPV (p = 0.007), with no significant difference in other complications. Multivariate analysis confirmed ILM peeling was strongly associated with improved visual acuity (OR = 6.90 [2.20–21.69], p < 0.001), reduced secondary ERM (OR = 0.05 [0.01–0.24], p < 0.001), and fewer reoperations (OR = 0.06 [0.01–0.54], p = 0.013). In conclusion, while both procedures improved BCVA, PPV with ILM peeling provided superior outcomes, suggesting potential benefits of ILM peeling for PDR patients undergoing vitrectomy.

-

Key words:

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy /

- Pars plana vitrectomy /

- ILM peeling