-

Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.), an ancient and highly valued fruit crop, is extensively cultivated in arid and semi-arid regions worldwide. Referred to as the 'fruit of paradise' for its ethnomedicinal significance, it belongs to the family Punicaceae and the genus Punica. In India, it is commonly known as 'Anar'[1], with nearly 90% of global production occurring in the northern hemisphere.

Among the diseases limiting pomegranate production, anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) is one of the most destructive[2]. In India, the first record of anthracnose in pomegranate was reported in earlier studies, highlighting its significance as an emerging disease of economic importance[3]. The disease manifests as small, circular leaf spots with yellow halos, leading to chlorosis and premature defoliation. Fruits develop sunken brown lesions, sometimes covered with gray to orange spore masses, resulting in decay at both unripe and ripe stages[4−7]. Yield losses range from 10% to 80%, depending on disease severity[8].

Current management largely relies on synthetic fungicides; however, their indiscriminate use contributes to fungicide resistance, environmental contamination, and health risks. This underscores the need for eco-friendly and sustainable alternatives. Botanicals offer a viable option, as their antifungal potential has been demonstrated in managing plant diseases[9]. Nevertheless, their efficacy can be inconsistent under field conditions, indicating the need for improved delivery and stability.

Nanotechnology provides an opportunity to enhance the effectiveness of plant-derived bioactives. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are particularly notable for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, including antifungal[10] and antibacterial[11,12] effects. Their nanoscale size enables close interaction with microbial cells, disrupting membrane integrity, impairing respiration, and binding to essential biomolecules such as DNA and proteins, thereby causing cellular dysfunction.

AgNPs can be synthesized via physical, chemical, or biological routes. Among these, biological (green) synthesis using plant extracts is considered cost-effective, non-toxic, and environmentally benign[13,14]. While green synthesis of AgNPs has been reported against several phytopathogens, limited research exists on their application against C. gloeosporioides in pomegranate. Addressing this gap could contribute to the development of effective, sustainable strategies for anthracnose management in organic and integrated farming systems.

-

Pomegranate leaves and fruits exhibiting typical anthracnose symptoms were collected and used for isolation. The pathogen was isolated using the standard tissue isolation method[15] by placing surface-sterilized (1% sodium hypochlorite for 30–60 s) tissue bits (3 mm) from lesion margins on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubating them at 28 ± 2 °C for 5–7 d. Emerging colonies were sub-cultured, and pure cultures were obtained through single-spore isolation. The purified isolates were maintained on PDA slants at 4 °C.

Pathogenicity was confirmed on mature fruits by following Koch's postulates. A 14-day-old culture was used to prepare a conidial suspension (1 × 104 conidia mL−1) using a hemocytometer. Healthy plants were sprayed with the suspension using a hand atomizer, while detached fruits were surface sterilized, wounded with sterile toothpicks, and inoculated with 20 µL of the suspension. Control plants and fruits were sprayed with sterile water. All inoculated samples were maintained at 28 ± 2 °C with 80% relative humidity, and observed for symptom development.

Genomic DNA of the isolated pathogen was extracted using the modified CTAB method[16], where 100 mg of mycelium was ground in liquid nitrogen and mixed with pre-warmed 2% CTAB extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA, and 1.4 M NaCl) and incubated at 60 °C for 30 min. The mixture was extracted with phenol : chloroform : isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and the aqueous phase was re-extracted with chloroform : isoamyl alcohol (24:1). DNA was precipitated by adding 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate, and 0.6 volume of chilled isopropanol, incubated at −20 °C for 1 h, centrifuged, washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and dissolved in 1 × TE buffer. DNA concentration and purity were checked using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer at 260/280 nm, and samples with a ratio of 1.8–2.0 were used for PCR amplification[17]. PCR was performed using C. gloeosporioides-specific primers in a 20 µL reaction containing 2 µL template DNA (50 ng·µL), 10 µL 2 × PCR master mix, 1 µL of each primer, and 7 µL nuclease-free water. The thermal cycling conditions were: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s, annealing at 63 °C for 60 s, and extension at 72 °C for 60 s; followed by final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. The amplified product was sequenced (Juniper Life Sciences, Bangalore), analyzed through BLASTn in NCBI for homology confirmation, aligned using ClustalW, and subjected to phylogenetic analysis using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 11 software with 500 bootstrap replicates. The primer details used in the study are depicted in Supplementary Table S1.

Preparation of plant extracts

-

Plant extracts from D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. juliflora were selected based on efficacy, availability, cost-effectiveness, and medicinal value. The plant materials were thoroughly washed with sterile water and air-dried at room temperature under aseptic conditions. The dried materials were ground using a clean grinder and stored in airtight containers at 4 °C for future use. For extract preparation, 20 g of powdered plant material was mixed with 200 mL of deionized water and heated at 95 °C for 30 min with intermittent stirring. The mixture was filtered twice through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the filtrates were stored for further use[18].

Synthesis of AgNPs

-

The green synthesis of silver nanoparticles was carried out by adding 10 mL of the plant extract filtrate to 90 mL of deionized water, followed by the addition of 1 mM AgNO3. The mixture was then heated at 80 °C for 15 min. A color change in the solution during this heating process indicates the formation of AgNPs[18].

Characterization of AgNPs

-

The characterization of silver nanoparticles was performed using UV–vis absorbance spectroscopy and a zeta particle size analyzer, utilizing the facilities available at the Centre for Nanotechnology in Raichur. For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), the samples were sent to the Centre for Nano and Soft Matter Sciences (CeNS) in Bengaluru.

UV–Vis spectroscopic analysis

-

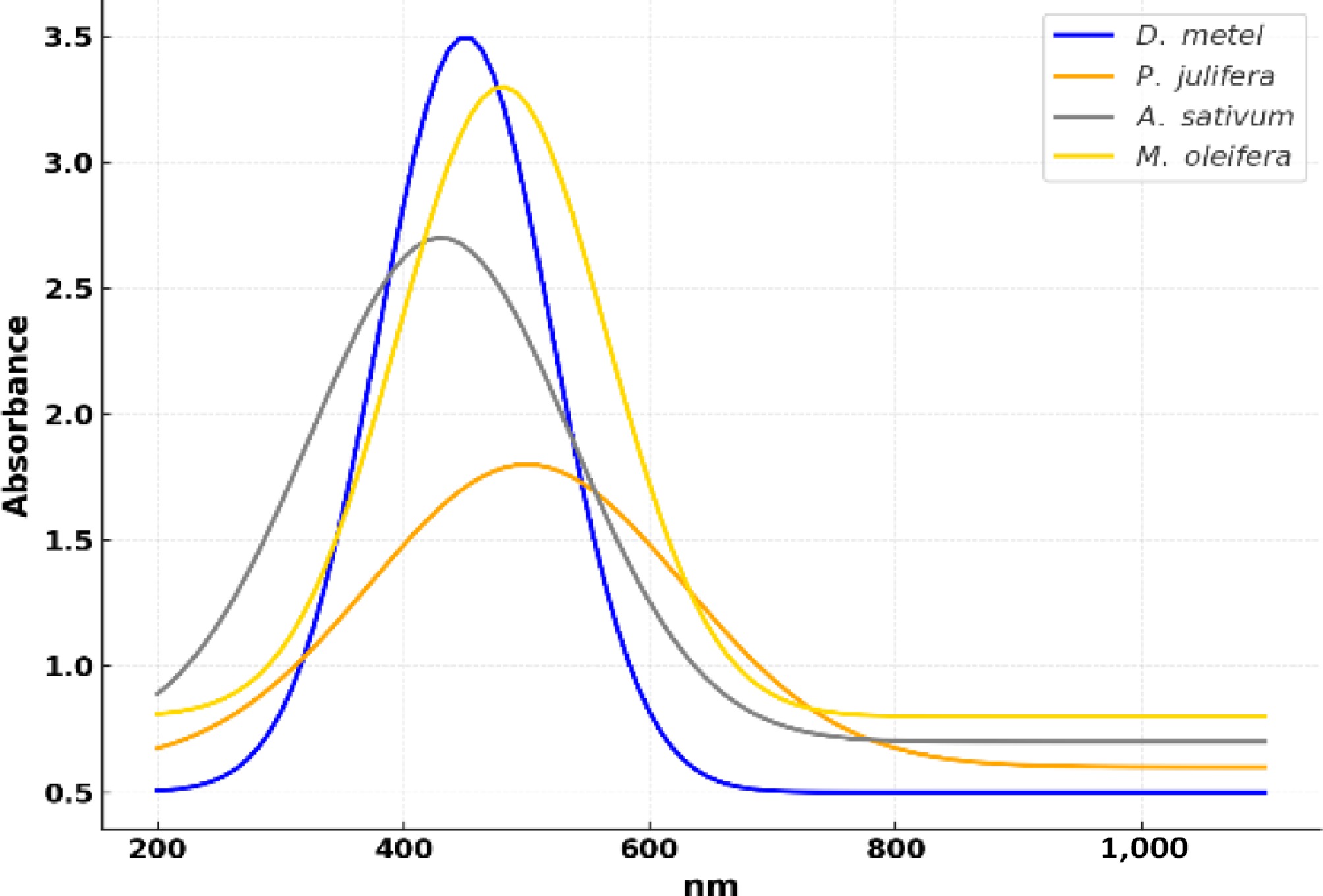

The bioreduction of silver nitrate (AgNO3) to silver nanoparticles was monitored using UV–Vis spectroscopy (UV-1800) after diluting the samples with deionized water[19]. The UV–Vis spectrograph of the silver nanoparticles was recorded using a quartz cuvette, with water serving as the reference. Spectra were obtained within the wavelength range of 350 to 600 nm.

Zeta particle size analysis

-

The particle size, distribution, and zeta potential of the nanoparticles were analyzed using a zeta Sizer (Malvern Instruments). Prior to measurement, an aliquot of the nanoparticles was diluted with pure water and sonicated for 10 min[20].

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) analysis

-

The morphology of the silver nanoparticles was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with the MIRA 3 model. The powdered AgNPs were uniformly spread on carbon-coated aligned stubs and subsequently subjected to gold sputtering. The morphology of the AgNPs was examined under field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). Additionally, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was employed to assess the purity of the AgNPs[21].

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis

-

The suspension containing silver nanoparticles was prepared for TEM analysis using the Talos F200 S model 1200 EX electron microscope. Initially, the TEM samples were sonicated for 10 min, after which they were deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid to dry completely. The shape and size of the AgNPs were assessed from the TEM micrographs by using software originpro[21].

Nanoparticle based formulation of potent botanicals in growth of the pathogen in vitro

-

The antifungal activity was assessed using the poison food technique. Centrifuged and oven-dried silver nanoparticles from D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. julifera were dissolved in sterile water to create a stock solution at a concentration of 10 mg·mL−1. Using sterile water as a dilution agent, final concentrations of AgNPs at 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg·mL−1 were prepared by adding 5 mL of the diluted stock solution to 45 mL of potato dextrose agar medium, at approximately 55 to 60 °C. The control set included 5 mL of sterile water without silver nanoparticles. The inoculated plates with varying concentrations of AgNPs were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C until full growth was observed in the control plates. Each control and experimental treatment was performed in triplicate, and data on fungal radial growth were recorded. The percentage of mycelial growth inhibition was calculated according to the method of Vincent[22].

Statistical analysis

-

The experiment followed a completely randomized design (CRD) with three replications. Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and differences among means were tested using critical difference (CD) at a 1% significance level (p = 0.01). Percentage data were angular-transformed prior to analysis to ensure homogeneity of variance.

-

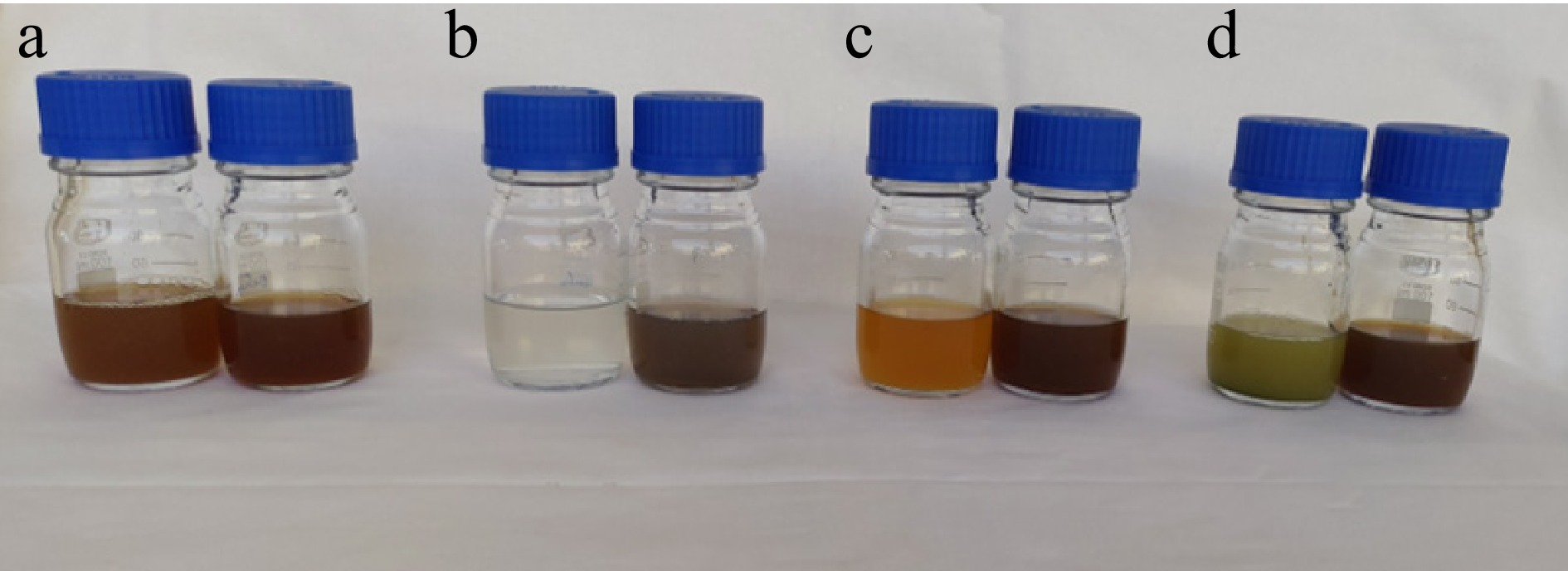

Fungal colonies isolated from anthracnose-infected pomegranate tissues were initially white and cottony, turning grey with pink to orange spore masses after 7 d on PDA. Microscopic examination revealed hyaline, aseptate, falcate conidia measuring 12–18 × 4–6 µm, typical of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides[23,24]. Upon inoculation, typical anthracnose symptoms appeared on pomegranate leaves and fruits within 7–10 d, while control samples remained symptomless. The pathogen was successfully re-isolated from symptomatic tissues, and its morphological and cultural characteristics were identical to the original isolate, thereby confirming C. gloeosporioides as the causal agent and satisfying Koch's postulates. Molecular confirmation further validated these findings, with high-quality genomic DNA exhibiting an A260/A280 ratio of 1.87. PCR amplification using C. gloeosporioides-specific primers produced a single distinct band of the expected size (~380) on a 1.5% agarose gel. The sequence obtained showed 99% homology with C. gloeosporioides reference sequences in the NCBI GenBank database, and phylogenetic analysis confirmed clustering of the isolate with known C. gloeosporioides accessions (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Symptoms on fruit. (b) Pure culture of pathogen. (c) Pathogenicity on mature fruit. (d) Acervuli. (e) ~380 band size on agarose gel. (f) Phylogenetic analysis.

Biosynthesis of AgNPs

-

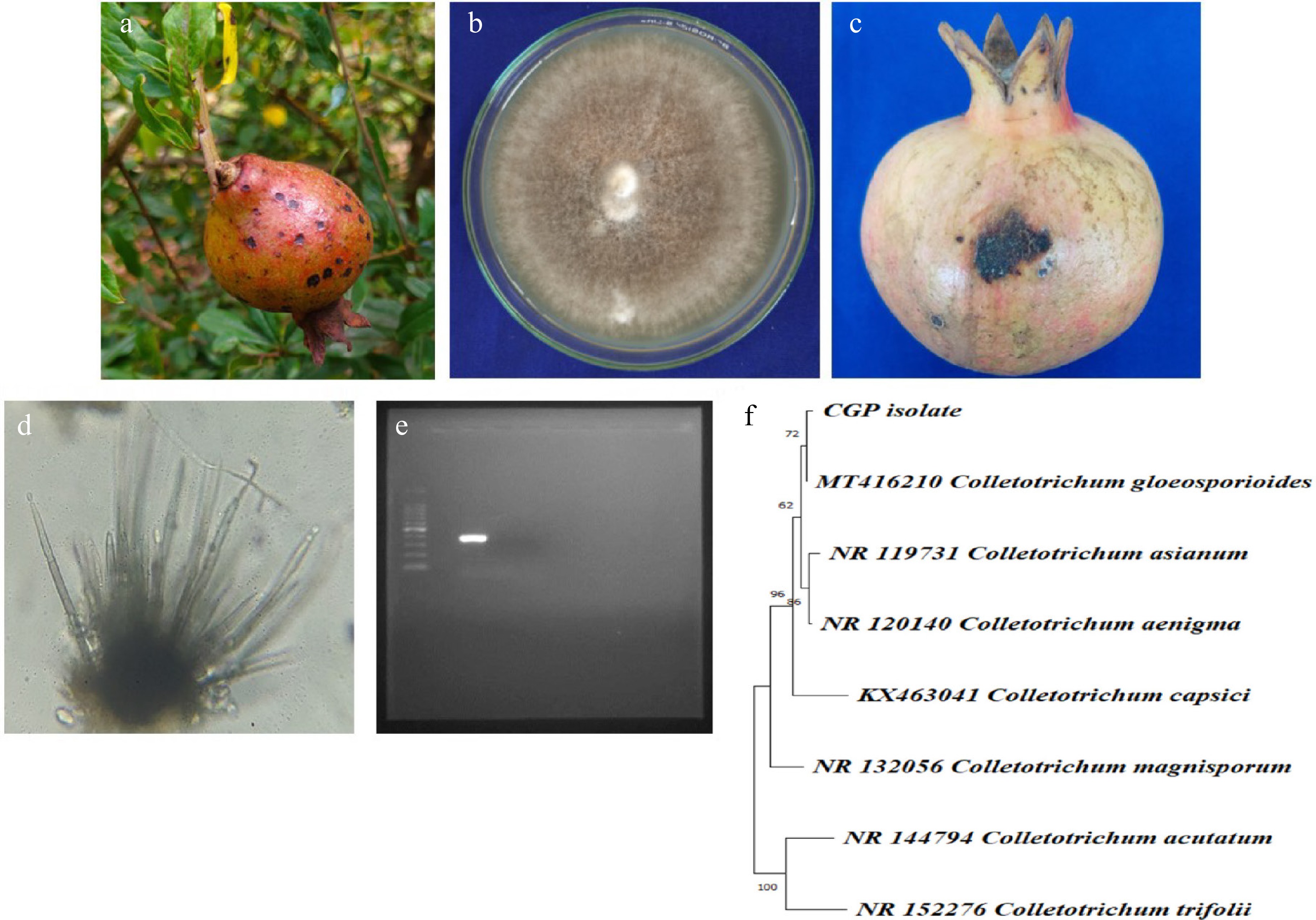

In the present experimental study, silver nanoparticles were synthesized using extracts from D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. julifera. These extracts served as both reducing and stabilizing agents in the green synthesis of AgNPs. The reduction of silver nitrate ions (Ag+) to silver nanoparticles (Ag0) was achieved after 30 min of heating at 95 °C in the presence of 1 mM AgNO3. Consequently, the extracts underwent noticeable color changes: D. metel transformed from light brown to dark brown, A. sativum from white to dark gray, M. oleifera from sandy color to dark brown, and P. julifera from green to dark brown during the nanoparticle synthesis process, indicating the formation of silver nanoparticles. These color changes morphologically indicate the presence of AgNPs (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Change of colour as an indication of silver nanoparticles synthesis. (a) D. metel extract and AgNPs, (b) M. oleifera extract and AgNPs, (c) A. sativum extract and AgNPs, (d) P. julifera extract and AgNPs.

Characterization of AgNPs

-

The pellets were blackish brown after centrifugation of the biosynthesized silver nanoparticles, and they were then formed into powder and used for characterization. Characterization is performed using a variety of different techniques, such as transmission and scanning electron microscopy (TEM, SEM), and UV Vis spectroscopy.

UV-vis absorbance spectrophotometry

-

The successful synthesis of silver nanoparticles was confirmed through UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometric analysis. All four plant extract-mediated AgNP samples exhibited strong absorption peaks in the range of 420 to 500 nm, which is characteristic of the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of silver nanoparticles. This optical property arises from the collective oscillation of free electrons on the nanoparticle surface in response to light excitation, confirming the formation of AgNPs in the colloidal suspension. Specifically, the UV–Vis spectra revealed distinct peaks at approximately 444 nm for D. metel-AgNPs, 432 nm for A. sativum-AgNPs, 453 nm for M. oleifera-AgNPs, and 446 nm for P. juliflora-AgNPs (Fig. 3). The slight variation in peak positions among the different extracts may be attributed to differences in particle size, shape, and surface chemistry influenced by the phytochemical composition of each botanical.

Particle size measurement

-

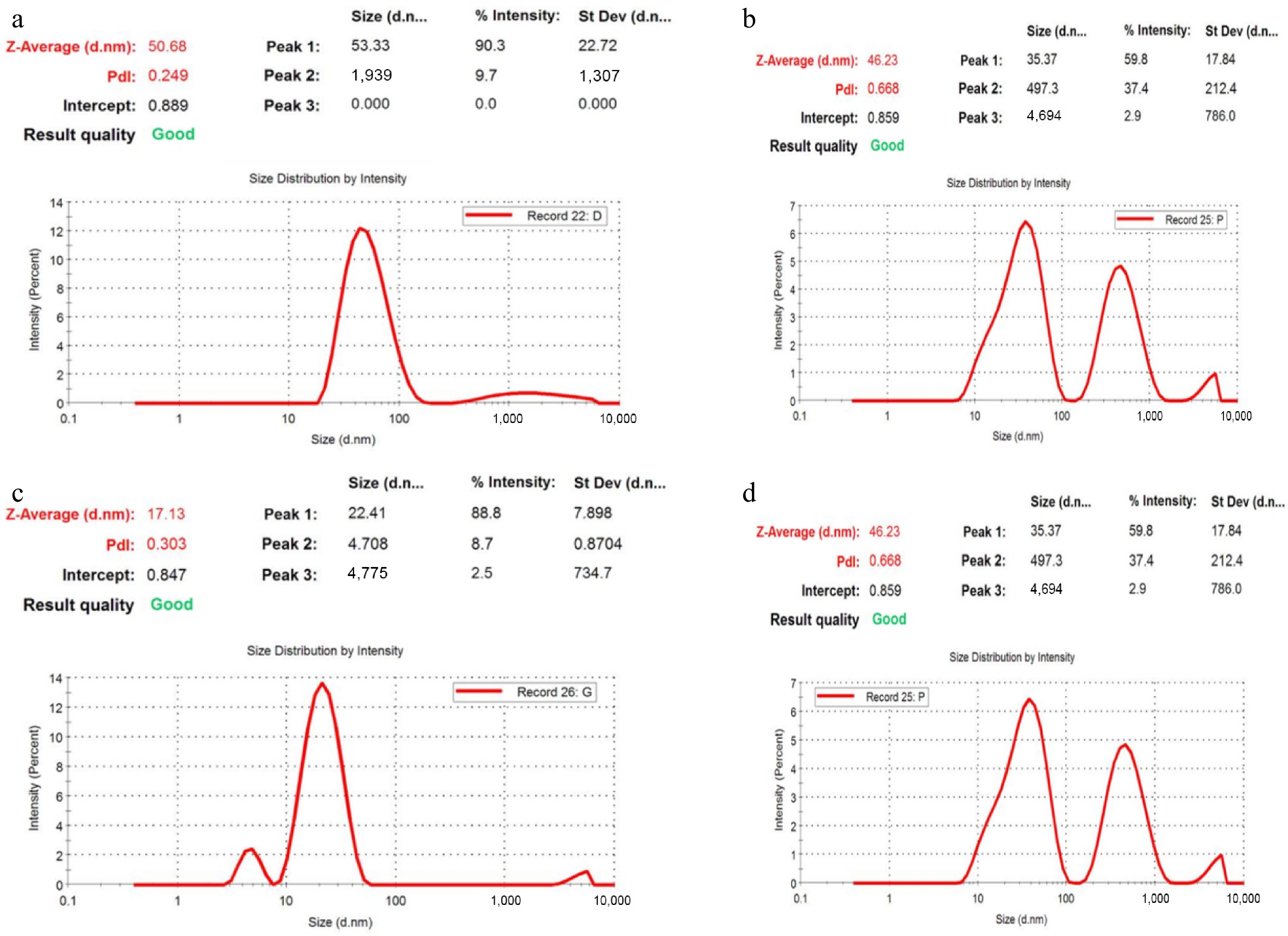

The size distribution and stability of the green-synthesized silver nanoparticles were analyzed using dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a zeta particle size analyzer. The average particle sizes of AgNPs synthesized from D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. juliflora were found to be 50.68, 17.13, 43.90, and 46.23 nm, respectively (Fig. 4). Among the four botanicals, A. sativum-derived nanoparticles exhibited the smallest size, indicating a more efficient nucleation process possibly influenced by the specific phytochemicals present in the garlic extract. In contrast, the largest particle size was recorded for AgNPs synthesized using D. metel, suggesting a slower reduction process or differences in the capping and stabilizing abilities of the extract.

Figure 4.

Zeta analysis of green synthesized AgNPs. (a) D. metel-AgNPs, (b) A. sativum AgNPs, (c) M. oleifera-AgNPs, (d) P. julifera AgNPs.

The polydispersity index (PDI) values were also assessed to determine the uniformity and dispersity of the nanoparticles. The PDI values for AgNPs synthesized from D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. juliflora were 0.249, 0.303, 0.351, and 0.668, respectively. A lower PDI indicates a more uniform particle size distribution, and values below 0.3 are generally considered acceptable for monodisperse formulations. In this study, the AgNPs synthesized from D. metel, A. sativum, and M. oleifera demonstrated relatively narrow size distributions, suggesting better colloidal stability and lower aggregation potential. However, the AgNPs derived from P. juliflora exhibited a higher PDI, indicating moderate polydispersity and potential for particle agglomeration.

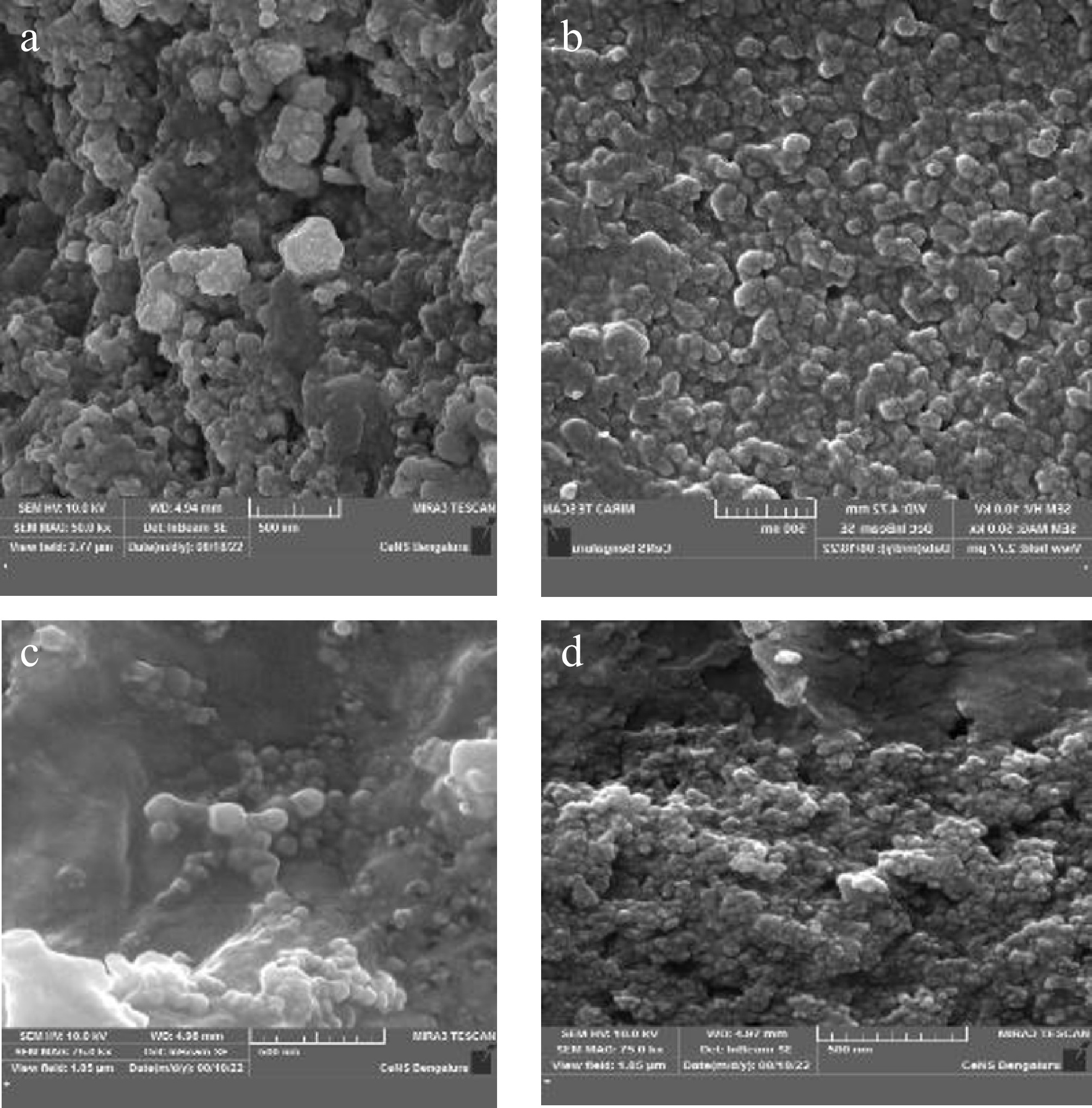

The morphology and elemental composition of the green-synthesized silver nanoparticles were examined using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). FESEM images revealed that the AgNPs synthesized from all four plant extracts exhibited relatively uniform shapes, predominantly spherical or near-spherical in morphology. The nanoparticles appeared well-dispersed with minimal signs of agglomeration, suggesting effective capping and stabilization by phytochemicals present in the botanical extracts (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) image of green synthesized silver nanoparticles. (a) D. metel, (b) A. sativum, (c) M. oleifera, (d) P. julifera.

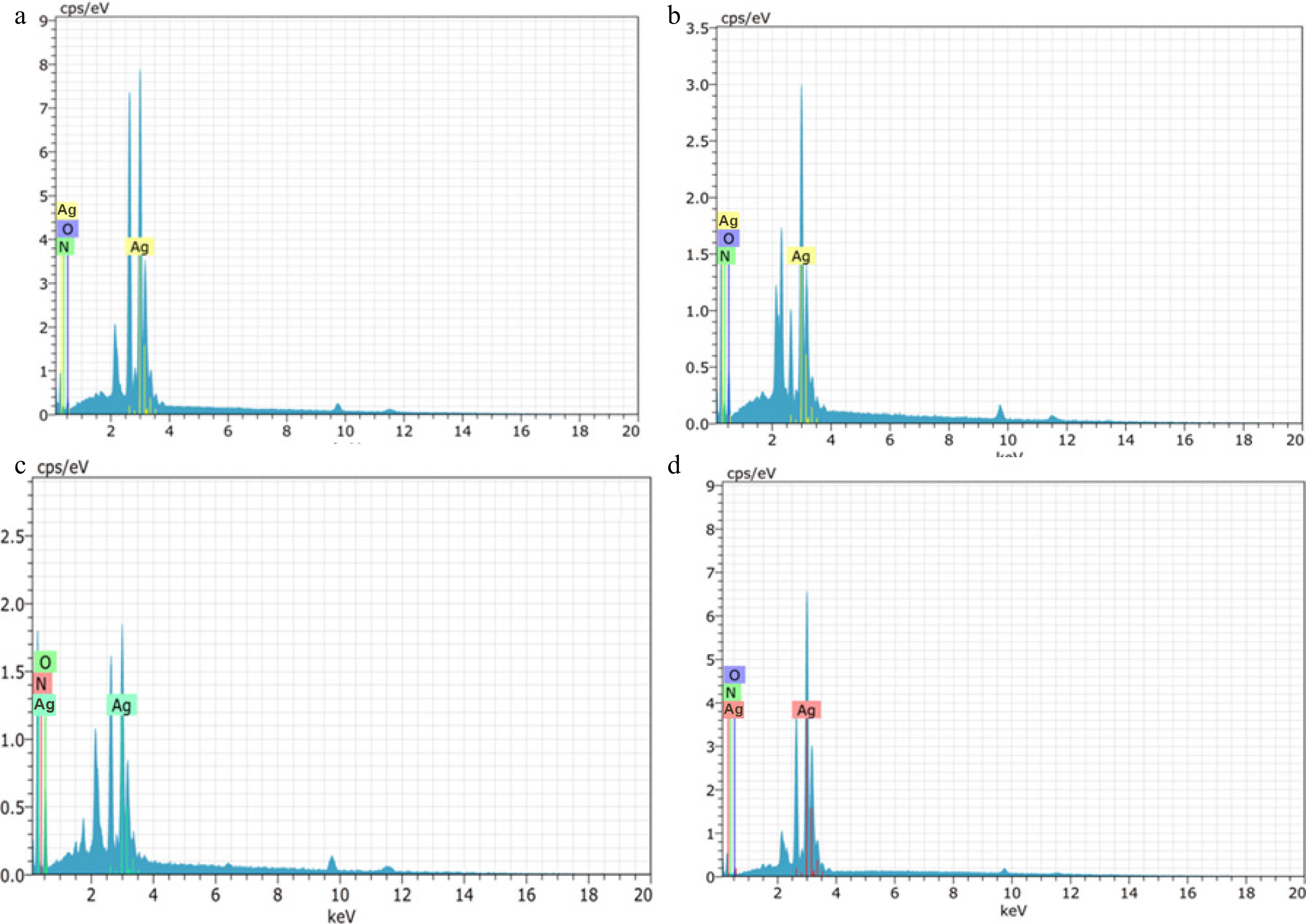

Elemental analysis through EDX further confirmed the presence and purity of silver in the synthesized nanoparticles. Prominent silver (Ag) signals were observed in the 3 keV region of the EDX spectra for all samples, which is a characteristic peak for elemental silver. The weight percentages of elemental silver detected in AgNPs synthesized from D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. juliflora were 92.41%, 73.75%, 96.75%, and 61.63%, respectively (Fig. 6). These results indicate a high level of silver incorporation, especially in the M. oleifera-derived sample. Additionally, minor peaks corresponding to oxygen and nitrogen were also detected, likely originating from plant-derived organic compounds that acted as reducing and stabilizing agents during nanoparticle synthesis.

Figure 6.

Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDX) spectra of green silver nanoparticles synthesized from (a) D. metel, (b) A. sativum, (c) M. oleifera, (d) P. julifera.

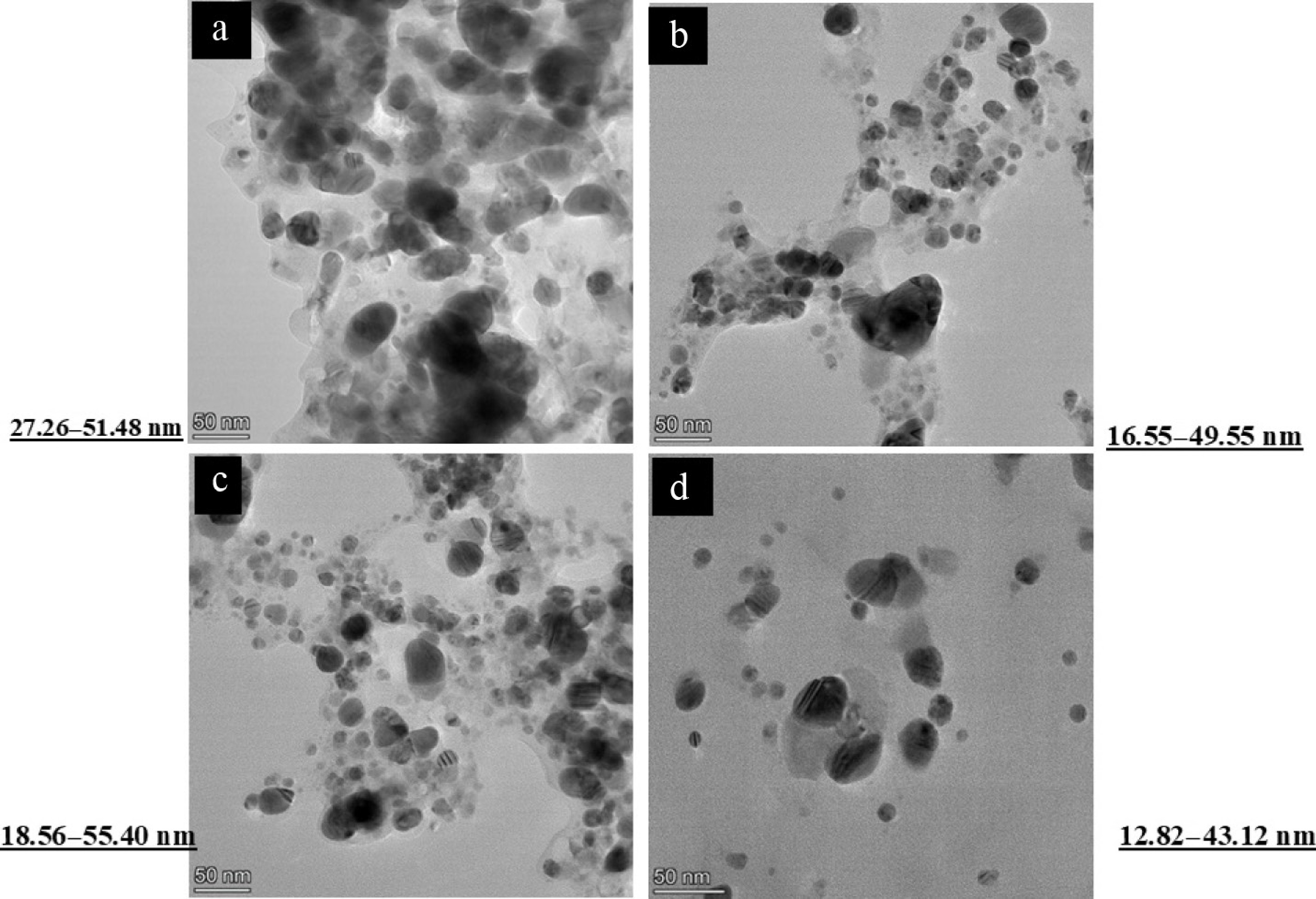

Transmission electron microscopy

-

The size, shape, and structural characteristics of the synthesized silver nanoparticles were further examined using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM). TEM images revealed that the AgNPs synthesized from all four plant extracts D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. juliflora, were predominantly spherical to ovoid in shape (Fig. 7). The nanoparticles appeared well-dispersed, with smooth surfaces and consistent morphology across different botanical sources, supporting the observations made under FESEM.

Figure 7.

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) image of green silver nanoparticles synthesized from (a) D. metel, (b) A. sativum, (c) M. oleifera, (d) P. julifera.

Particle size analysis was performed by selecting 100 nanoparticles at random from multiple TEM micrographs for each botanical source. The particle sizes ranged from 27.26 to 51.48 nm for D. metel, 16.55 to 49.55 nm for A. sativum, 18.56 to 55.40 nm for M. oleifera, and 12.82 to 43.12 nm for P. juliflora. These results confirmed the nanoscale dimensions of the particles and were in strong agreement with the data obtained from dynamic light scattering (DLS) using the zeta size analyzer. The relatively smaller particle sizes observed in A. sativum and P. juliflora-mediated AgNPs may account for their enhanced antifungal efficacy, given the greater surface area and better interaction with fungal cell walls and membranes, facilitating improved adhesion, penetration, and subsequent disruption of cellular integrity.

In vitro evaluation of plant-extract-mediated silver nanoparticles against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

-

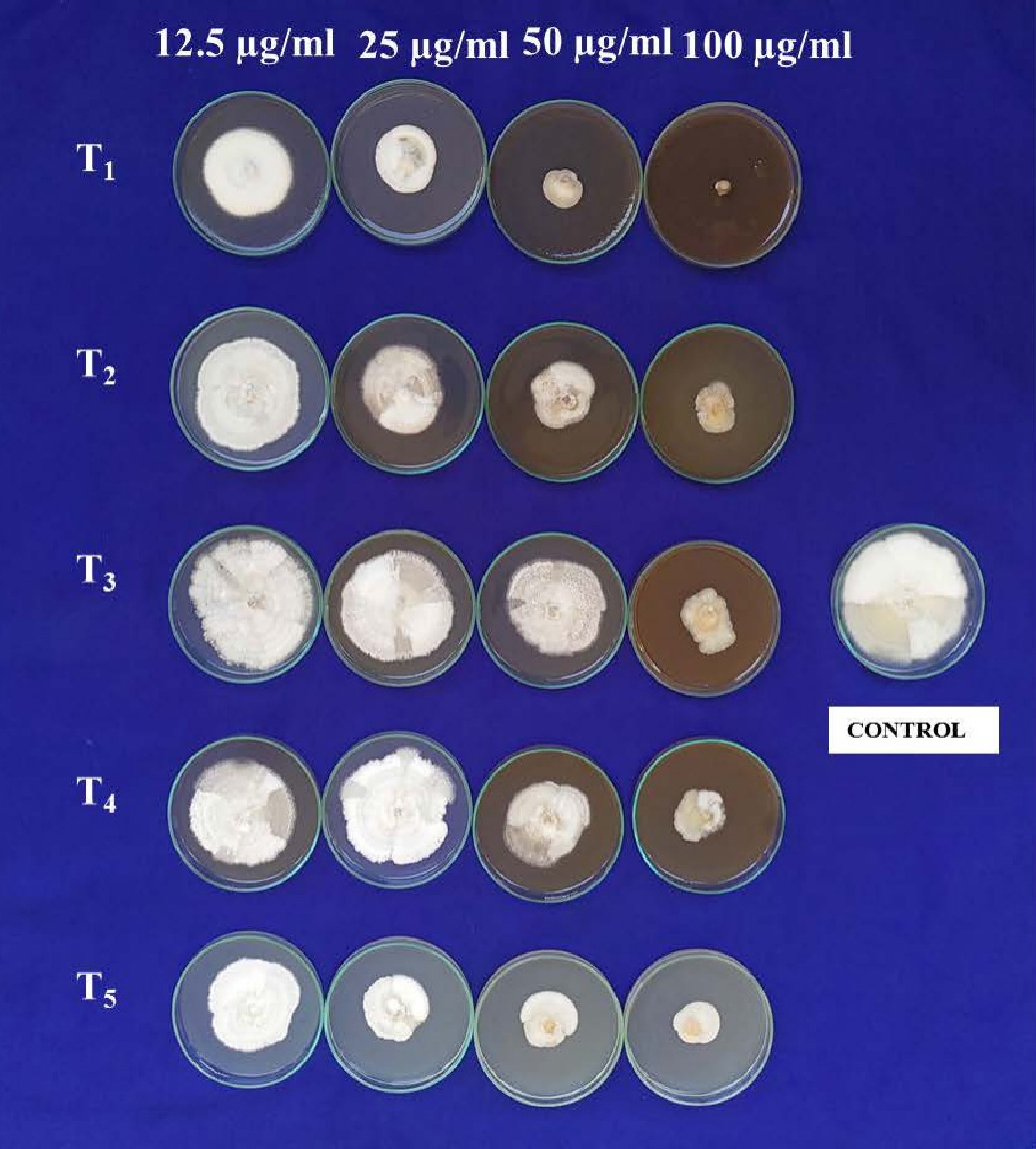

The antifungal potential of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles derived from D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. juliflora was assessed against C. gloeosporioides using the poison food technique at concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µg·mL−1 (Fig. 8, Table 1). All treatments significantly reduced mycelial growth compared to the control, with inhibition generally increasing in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 8.

Antifungal bio assay AgNPs against C. gloeosporioides. T1: D. metel, T2: A. sativum,T3: M. oleifera, T4: P. julifera.

Table 1. In vitro evaluation of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides using the poison food technique.

Sl.

No.Treatment Concentrations 12.5 µg·mL−1 25 µg·mL−1 50 µg·mL−1 100 µg·mL−1 MG MI #Sporulation MG MI Sporulation MG MI Sporulation MG MI Sporulation 1 D. metel-AgNPs 54.93 (47.81) 38.96 ++ 30.00 (33.20) 66.67 + 25.00 (29.99) 72.22 _ 0.01 (0.54) 99.99 _ 2 A. sativum-AgNPs 64.90 (53.65) 27.89 ++ 53.11 (46.76) 40.99 + 44.03 (41.56) 51.07 _ 23.00 (28.65) 74.44 _ 3 M. oleifera-AgNPs 78.31 (62.22) 12.99 ++ 67.00 (54.92) 25.56 ++ 57.33 (49.20) 36.30 + 35.00 (36.26) 61.11 _ 4 P. julifera-AgNPs 74.66 (59.76) 17.04 ++ 68.00 (55.53) 24.45 + 54.00 (47.28) 40.00 _ 29.66 (32.99) 67.04 _ 5 AgNO3 78.96 (62.67) 12.27 ++ 59.33 (50.36) 34.07 + 54.67 (47.66) 39.26 _ 27.67 (31.72) 69.26 _ 6 Copper oxy

chloride63.2 (52.7) 30.00 ++ 45.6(42.5) 49.30 + 32.4(35.0) 63.99 + 19.7 (26.2) 78.11 − SE ± m CD (p = 0.01) Treatment 0.15 0.42 Concentration 0.13 0.37 Treatment × Concentration 0.29 0.83 Data represent mean mycelial growth (MG, mm), angular-transformed values in parentheses, and mycelial inhibition over control (MI, %). Sporulation scoring: ++ = good (5–10 spores/microscopic field, 40×); + = poor (1–5 spores/microscopic field, 40×); – = no sporulation. Mean of three replications. CD = critical difference at p = 0.01; SE = standard error. Across all concentrations, D. metel-AgNPs produced the greatest inhibition, reaching complete suppression (99.99%) at 100 µg·mL−1. A. sativum-AgNPs showed the second-highest inhibition, followed by P. juliflora and M. oleifera. AgNO3 displayed moderate activity, while copper oxychloride, included as a chemical control, exhibited strong inhibition but was consistently less effective than D. metel-AgNPs.

Sporulation was generally reduced at ≥ 25 µg·mL−1 and was absent in most treatments at 50 and 100 µg·mL−1, except for occasional poor sporulation in M. oleifera-AgNPs. These results indicate that green-synthesized AgNPs, particularly those derived from D. metel, exhibit strong in vitro antifungal activity against C. gloeosporioides, with efficacy surpassing that of the conventional fungicide control.

-

The present study demonstrates that green-synthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), particularly those derived from D. metel, exhibit strong antifungal activity against C. gloeosporioides. The superior performance of D. metel-AgNPs compared to other plant-based AgNPs, AgNO3, and copper oxychloride can be attributed to several factors.

Firstly, variations in antifungal efficacy among plant-derived AgNPs are likely due to differences in the phytochemical profiles of the source extracts, which influence nanoparticle size, morphology, and surface chemistry[13]. Alkaloids, phenolics, and flavonoids in D. metel may act as both reducing and capping agents, producing smaller, more stable nanoparticles with higher surface reactivity[14]. Smaller AgNPs have been reported to possess enhanced antimicrobial properties due to their greater surface area-to-volume ratio, which facilitates increased contact with fungal cell walls and membranes[18,25].

The inhibitory effect of AgNPs on C. gloeosporioides likely involves multiple mechanisms. AgNPs can adhere to the fungal cell wall and membrane, causing structural disintegration and increased permeability[26]. Penetration into the cytoplasm may lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disruption of mitochondrial function, and interference with key enzymes and DNA replication[27]. The binding of silver ions to sulfur- and phosphorus-containing biomolecules can further inhibit protein synthesis and nucleic acid function[28]. Such multifaceted modes of action reduce the likelihood of resistance development compared to single-target fungicides.

The concentration-dependent increase in inhibition observed in this study aligns with previous findings where higher AgNP doses led to greater antifungal efficacy[20,29]. The complete growth suppression achieved by D. metel-AgNPs at 100 µg·mL−1 highlights their potential as an alternative to conventional fungicides. Copper oxychloride, while effective, was consistently outperformed by D. metel-AgNPs, suggesting that AgNPs may provide superior control, possibly due to their ability to disrupt multiple cellular targets simultaneously.

Reduced sporulation at higher AgNP concentrations, particularly ≥ 50 µg·mL−1 indicates that AgNPs not only inhibit vegetative growth but may also impair reproductive structures, thus limiting disease spread. Similar sporulation inhibition has been reported in Alternaria solani and other phytopathogens treated with green-synthesized AgNPs[29].

These results support the potential of plant-extract-mediated AgNPs, especially those synthesized using D. metel, as eco-friendly antifungal agents. However, further work on nanoparticle characterization, phytotoxicity assessment, and field-level validation is essential to establish their practical applicability in integrated disease management systems.

-

The present investigation successfully demonstrated the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extracts of D. metel, A. sativum, M. oleifera, and P. juliflora. The synthesized nanoparticles were characterized by their nanoscale size, spherical morphology, and crystalline nature. Among the tested botanicals, D. metel-derived AgNPs exhibited the most potent antifungal activity, achieving complete inhibition of C. gloeosporioides at a concentration of 100 µg·mL−1. The antifungal efficacy of these green-synthesized nanoparticles was found to be comparable to, and in some cases superior to, conventional fungicides such as copper oxychloride and silver nitrate. These findings highlight the potential of plant-mediated AgNPs as eco-friendly alternatives to synthetic chemical fungicides in the management of anthracnose disease in pomegranate.

However, the study did not determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), which is essential for defining the lowest effective dose. Future research should focus on establishing MIC values, evaluating in vivo efficacy, and assessing phytotoxicity and environmental safety to facilitate field-level application and regulatory acceptance of green nanotechnology in crop protection.

This research received no external funding.

-

No ethical rules were violated while conducting this research work.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: experimental work and data collection: Archana AM, Lokesha MS; drafting and revision: Archana TS, Kumar D; contributed equally to the conception, design, execution, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript: Archana AM, Lokesha MS, Archana TS, Kumar D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 The primer sequences used are depicted below.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Archana AM, Lokesha MS, Archana TS, Kumar D. 2026. Exploring the antifungal potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in pomegranate. Studies in Fungi 11: e002 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0031

Exploring the antifungal potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in pomegranate

- Received: 25 January 2025

- Revised: 28 October 2025

- Accepted: 04 November 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: The green synthesis of nanoparticles offers an eco-friendly alternative to conventional chemical and physical methods for plant disease management. In this study, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were synthesized using aqueous extracts of Datura metel, Allium sativum, Moringa oleifera, and Prosopis juliflora. The synthesized AgNPs were characterized using UV−Vis spectroscopy, zeta size analysis, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These techniques confirmed the formation of pure, crystalline nanoparticles ranging from 15 to 50 nm. The antifungal activity of the AgNPs was evaluated in vitro using the poison food technique on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µg·mL−1. AgNPs synthesized from D. metel showed complete inhibition (100%) of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides at 100 µg·mL−1, followed by A. sativum (74.44%), P. juliflora (67.04%), and M. oleifera (61.11%). These findings indicate that green-synthesized AgNPs, particularly those derived from D. metel, exhibit significant antifungal activity against C. gloeosporioides and may serve as potential alternatives to synthetic fungicides.

-

Key words:

- Green synthesis /

- Silver nanoparticles /

- Antifungal activity /

- Pathogen /

- Colletotrichum gloeosporioides