-

Natural products are compounds synthesized by plants, animals, and microorganisms in nature, including active small-molecule compounds, and some large-molecule compounds. While they do not directly participate in the growth and development of organisms, they hold high value due to their complex and diverse structures, which allow them to interact with biological targets, and even exhibit a certain adaptive potential under adverse conditions[1]. Consequently, they have long served as a crucial source for drug development. A number of compounds such as terpenoids, alkaloids, and polysaccharides found in plants, offer antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune-regulating, and antibacterial functions[2]. Compared with other sources, plant-derived natural products are extensively used in various fields, and their significance is becoming increasingly prominent. Common plant-derived drugs include morphine, artemisinin, and paclitaxel, which have made significant contributions to human health, and have driven advances in modern medicine[2]. Less common or underutilized plant-derived natural products, such as Sapindaceae and Anacardiaceae families, also have a wide range of antioxidant capacity[3], and an even higher tolerance to stress[4]. As functional ingredients, plant-derived natural products have garnered increasing attention, and their mechanisms of action can be applied across industries, offering promising market prospects.

Although plant-derived natural products are widely utilized in various fields, their production process faces numerous challenges that hinder further research and application development. Currently, the production of most plant-derived natural products relies on direct extraction from plants, a traditional method that presents several significant issues. Firstly, large-scale cultivation of plants consumes valuable arable land and requires a relatively long growth period. Additionally, the concentration in plants is typically low, and the extraction process is time-consuming and cumbersome, often requiring large amounts of organic solvents and water, which raises costs and increases environmental impact. Chemical synthesis offers an alternative, but the synthesis of natural products often involves multi-step reactions, and some steps require toxic chemical reagents that can be harmful to the environment. In recent years, the rise of microbial synthesis has introduced a new approach to producing natural products. Using microbial cell factories, scientists can synthesize complex natural products quickly and with precision. In contrast, microbial methods provide a more abundant source of raw materials and allow for greater control over the production process. This approach also offers environmental benefits, being low-carbon and more sustainable, as it minimizes the use of organic solvents, and reduces the environmental burden. Consequently, microbial cell factory synthesis of plant-derived natural products has become a significant research focus, offering a sustainable production method while promoting further practical applications in medicine, agriculture, and other fields.

A deeper understanding of the structures and mechanisms of these compounds can facilitate their application in modern medicine. As a result, this paper reviews the progress made in the biosynthetic pathways of alkaloids, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, and polysaccharides—common plant-derived natural product compounds. It explores the mechanisms of key enzymes involved in the synthesis process, using specific examples of microbial factory-based production of natural products. Additionally, it summarizes the functional and activity mechanisms of these compounds to better inform their practical application.

-

In recent years, scientists have discovered a wealth of active natural products derived from plants with diverse structural properties, leading to their classification into several broad categories. They offer abundant resources for humans across industries such as food, agriculture, cosmetics, and even flavors. For example, anthocyanins and carotenoids serve as natural pigments in food and cosmetics, providing coloring effects[5,6]. Phenylpropanoids like rosmarinic acid and chlorogenic acid are commonly used as feed additives to support animal health[7,8]. Patchouli alcohol and terpineol, derived from terpenoids, are extracted to produce essential oils used in perfumes for health and beauty applications[9]. An overview of common natural products of different classes in food and their functional applications is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Sources of various common natural products in food and their functional applications.

Kinds Compounds Sources Effects Applications Ref. Alkaloids Tomatidine Solanum lycopersicum Antibacterial, anticancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective Foods, drugs [10] Piperine Piper nigrum Anticancer, antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective Food flavorings, drugs [11] Berberine Phellodendron Bark Antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral Drugs [12] Caffeine Coffee, tea, chocolates Analgesic, anticancer, antioxidant, antibacterial Meals and beverages [13] Trigonelline Eggplant Anti-tumor, neuroprotective Foods, drugs [14] Betaine Wheat bran, wheat germ, spinach Anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant Dietary supplement [15] Morphine Poppy heads Pain relief, sedation, euphoria, respiratory depression Agonists [16] Theobromine Cocoa tree Neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory Obesity treatment drugs or formulations [17] Terpenoids Carvacrol Origanum compactum Antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory Food preservative [18] Menthol Peppermint leaves Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant Additive, essential oils [19] Thymol Thymus pectinatus Antimicrobial, antioxidant Food flavorings, mouthwashes [20,21] Caryophyllene Piper nigrum Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-neurodegenerative The essential oils of spices and food plants [22] Nerolidol Citrus sinensis Antioxidant, anti-microbial, anti-biofilm, anti-parasitic, insecticidal Essential oils, flavor enhancer [23] Perillyl alcohol Cymbopogon caesius Anticancer, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory Aroma, natural additives in food [24] Camphene Piper cernuum Anti-tumor, antioxidant Food flavorings, fragrances, plasticizers [25] Stevioside Stevia rebaudiana Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant Sweetener, immunomodulator [26] Patchouli alcohol Pogostemon cablin Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor Medicine, flavouring and food industries, essential oils [9] Ginsenoside Panax ginseng Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, immunity-improving Antibiotics, drugs [27] Corosolic acid Lagerstroemia speciosa Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, Medicines, health products [28] β-carotene Medicago sativa Anticancer, anti-disease Pigment [6] Lutein NuMex LotaLutein Antioxidant, photoprotective Dietary supplements, pigment [29] Capsanthin Capsicum annuum Antioxidant, anticancer Nutrients, pigment [30] Lycopene Amaranthus gangeticus Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer Food additive, jelly [31] phenylpropanoids Eugenol Eugenia caryophyllata Antimicrobial, antifungal Food preservative and colorant [32] Umbelliferone Fruits, vegetables, and plants Antioxidant, anticancer Nutraceuticals, functional foods, drugs [33] Ferulic acid Sorghum straw Antioxidant, antiviral, anticancer Beer production [34] Chlorogenic acid Higher dicotyledonous plants and ferns Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antioxidant Feed additive [7] Caffeic acid Plant-based lignocelluloses Antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic Food, drugs [34] Vanillin Vanilla planifolia Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial Sweetener, food additive [35] Rosmarinic acid Perilla frutescens Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial Food flavoring, and preservative [8] Polysaccharides Lentinan Lentinus edodes Antitumor, immune potentiating Food supplement, biological response modifier [36] Lycium barbarum polysaccharide Lycium barbarum Antioxidant, anti-fatigue, anti-diabetic, neuroprotection Food, medicine, dietary supplements [37] Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide Ganoderma lucidum Antitumor, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antioxidant Functional foods, and pharmaceuticals [38] Longan polysaccharide Dimocarpus longan Antioxidant, anticancer, immunomodulatory, hypoglycemic, antibacterial Herbs, foods [39] Pumpkin polysaccharide Pumpkin Antidiabetic, antioxidant, anticancer, immunomodulation,antibacterial Foods, Chinese medicine [40] Tea polysaccharide Tea Antioxidant, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, Beverages [41] Alkaloids

-

Alkaloids are one of the earliest classes of biologically active natural organic compounds studied by scientists. They generally refer to organic cyclic compounds containing oxidized nitrogen atoms found in living organisms and are often the active ingredients in many medicinal plants. Alkaloids are abundant in nature; common alkaloids found in food can be classified based on their structure, such as purine alkaloids, quinoline alkaloids, and ergot alkaloids. For example, morphine and codeine, derived from the opium poppy, are potent analgesics and cough suppressants[16,42]. Berberine, found in Coptis chinensis, has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties and is commonly used to treat diarrhea[12]. Tomatidine, present in tomatoes and potatoes, not only plays an antibacterial role but can also be used as a vaccine adjuvant to enhance drug delivery[43].

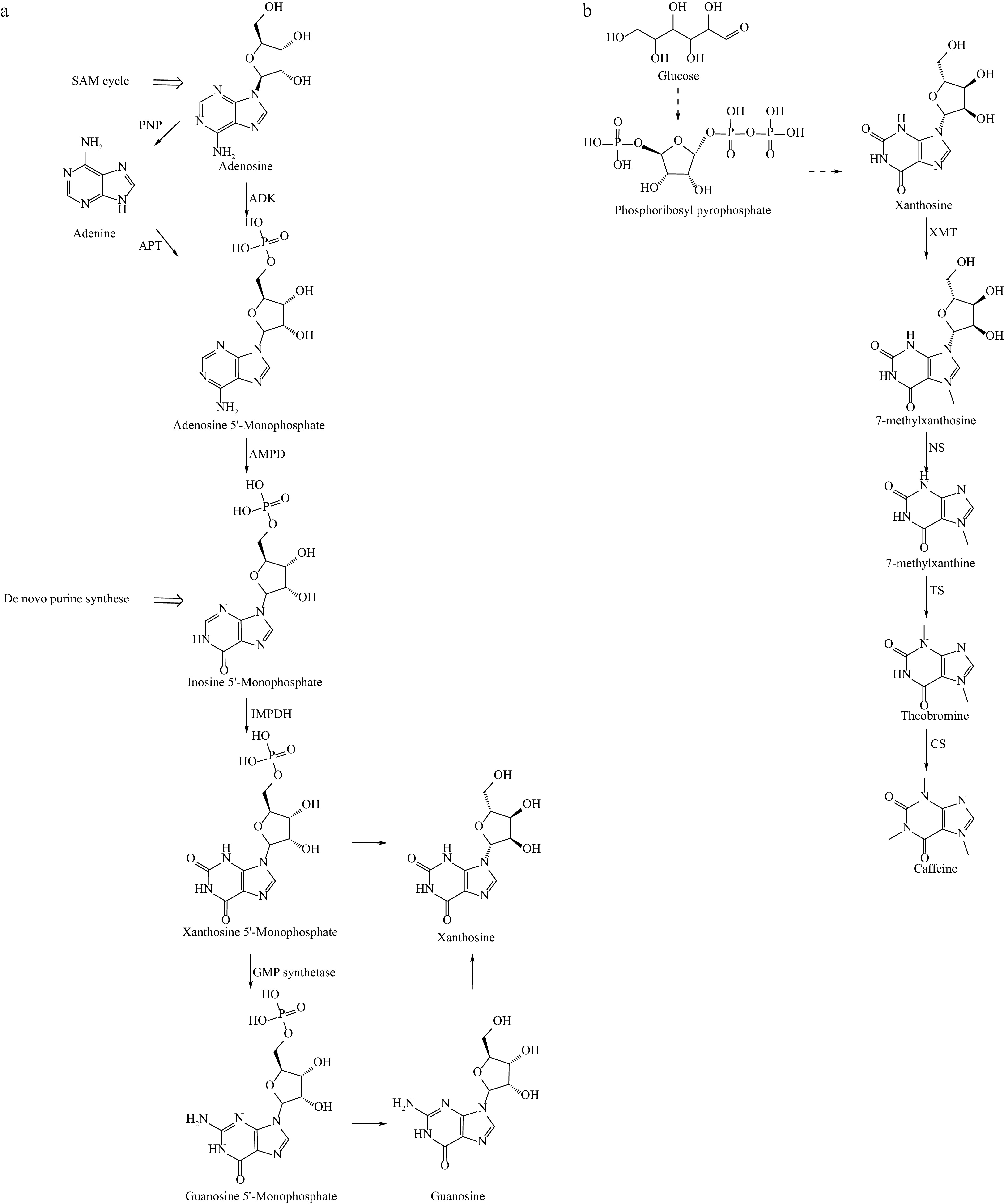

Unlike other natural products, alkaloids have a wide structural diversity, which gives rise to different synthetic precursors and pathways. Caffeine, one of the most popular alkaloids, is widely consumed in foods such as tea, coffee, and chocolate. It is also used as a common prescription drug for its analgesic effects. Additionally, caffeine's antioxidant properties contribute to its use in beauty products, and even as an athletic supplement[13]. In nature, caffeine synthesis occurs in two main phases: the donor phase and the main synthesis phase. As shown in Fig. 1, xanthosine, the starting substrate for purine base synthesis, can be synthesized through at least four different pathways: the de novo purine synthesis pathway, the AMP degradation pathway, the GMP degradation pathway, and the S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) cycle. The purine ring is synthesized from precursors such as CO2, glycine, glutamine, and 5-phosphorylribose-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) to form purine nucleotides. These nucleotides undergo a two-step reaction to generate xanthosine from inosine 5'-Monophosphate (IMP). SAM acts as a methyl donor for the three-step methylation process, converting into S-adenosylhomocysteine(SAH), which is hydrolyzed to produce homocysteine and adenosine. The homocysteine then re-enters the SAM cycle to regenerate SAM, while adenosine participates in xanthosine production. This is followed by a series of N-methylation reactions that ultimately result in the synthesis of caffeine.

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic pathway of caffeine. (a) Synthesis of the precursor substance guanosine. (b) The Synthetic Pathway from guanosine to caffeine. ADK: adenosine kinase; PNP: purine nucleoside phosphorylase; APT: adenine phosphoribosyltransferase; AMPD: adenosine 5'-monophosphate deaminase; IMPDH: inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase; XMT: xanthosine methyltransferase; NS: N-methylnucleosidase; TS: thymidylate synthase; CS: caffeine synthase.

The production of caffeine involves three N-methylation reactions, each requiring SAM as a donor, highlighting the importance of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase 1 (SAMS) and N-methyltransferases. Hu et al.[44] enhanced SAMS activity in Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Streptomyces spectabilis through DNA rearrangement techniques, resulting in a doubling of intracellular SAM accumulation. Similarly, Ravi Kant et al.[45] overexpressed the SAM synthase gene, SAM2, in Pichia pastoris, leading to increased SAM production. In Camellia sinensis, tea caffeine synthase 1 (TCS1) is the first reported N-methyltransferase responsible for catalyzing methylation reactions, and is the rate-limiting enzyme in caffeine synthesis. In Camellia ptilophylla, a close relative of tea plants, a natural deficiency in caffeine synthesis was observed. Transcriptome analysis revealed that TCS1 expression levels in C. ptilophylla were significantly lower than in conventional tea plants, suggesting a high correlation between TCS1 and caffeine synthesis. Researchers have also explored microbial production of caffeine. In a previous study by McKeague et al.[46], caffeine synthesis genes were introduced into a eukaryotic system, leading to the production of 270 μg/L of caffeine through the overexpression of target genes. Li et al.[47] improved N-methyltransferase expression through codon optimization and strong promoter modification of TCS1 in E. coli, achieving a caffeine yield of 21.46 mg/L from glucose as the sole carbon source. Caffeine has also been used in genetically modified plants to increase pest resistance. The introduction of three N-methyltransferases into tobacco leaf discs through Agrobacterium-mediated transformation significantly enhanced resistance to pests, such as tobacco cutworms, and improved the plants' growth and survival[48].

Alkaloids are secondary metabolites produced by plants in response to habitat stress, due to their rich anti-inflammatory mechanisms, alkaloids play a crucial role in the treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD). Piperine, an alkaloid commonly found in black pepper, is widely used as a food condiment due to its pungent flavor. Beyond its culinary use, piperine also exhibits significant pharmacological activity. In AD mouse models, piperine treatment significantly reduced the infiltration of inflammatory factors in ear cells and inhibited cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α during a Type 2 helper T cell (Th2)-mediated immune response[49]. Fenugreek, a spice commonly used in Indian cuisine to impart a nutty flavor, contains the active ingredient trigonelline, which is important for neuroprotection. Over time, the body's ability to clear free radicals may diminish, leading to oxidative stress and damage to nerve cells. Feng et al.[14] investigated the protective effects of trigonelline on PC12 nerve cells subjected to hydrogen peroxide-induced damage. The results demonstrated that trigonelline treatment increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px, while reducing the levels of lipid peroxide MDA, thereby mitigating oxidative stress in nerve cells.

Terpenoids

-

Terpenoids are a broad class of compounds and their derivatives, which are usually classified according to the number of isoprene units in their specific structures, including categories such as monoterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, diterpenoids, and others. Monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids are the primary components of volatile oils in plants, such as menthol[19], and caryophyllene[22], and are commonly used in the production of various flavors and fragrances. Diterpenoids and triterpenoids are key components in the formation of resins, while tetraterpenoids, such as carotenoids, are primarily fat-soluble pigments widely used as natural colorants in food[6]. Additionally, triterpenoids can form various saponins, which are utilized in drug therapies[27].

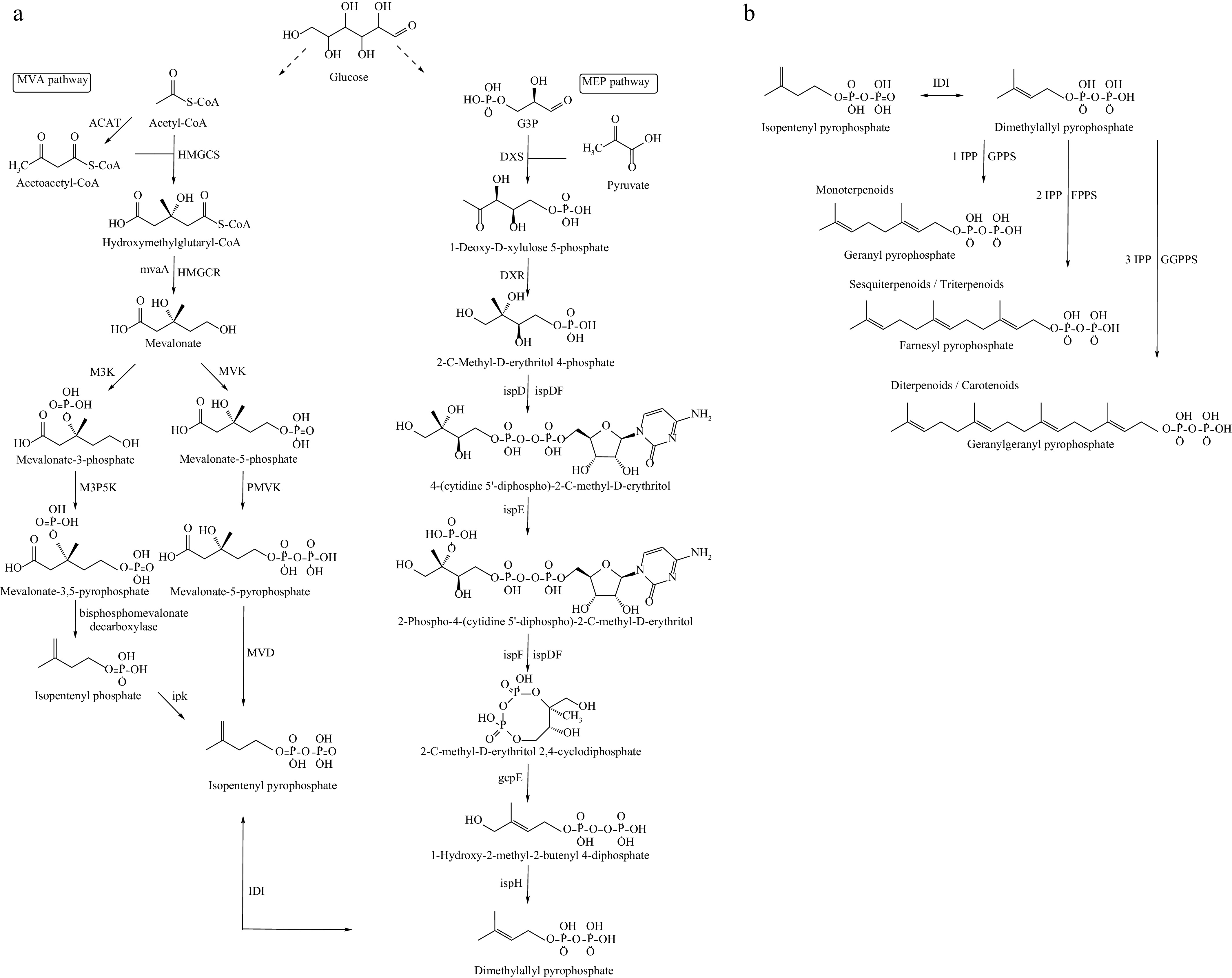

The synthesis of terpenoids is a complex process, as illustrated in Fig. 2. First, the basic precursor substances—acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P)—are derived from glucose through the upstream metabolic pathway. These precursors then form the basic building blocks of terpenoids, isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), via the mevalonate (MVA), and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways. Next, a molecule of DMAPP binds with varying numbers of IPP molecules to synthesize the precursors of different terpenoid compounds, including geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP), catalyzed by isopentenyltransferase enzymes geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPPS). Finally, these precursor molecules are modified by cytochrome P450(CYP450) enzymes to generate a wide variety of terpenoids.

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic pathway of terpenoid skeletons. (a) The synthesis of the common precursors of all terpenoids, isopentenylpyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). (b) The pathway for IPP and DMAPP to synthesize terpenoid skeletons through terpene synthases. ACAT: acyl coenzyme A-cholesterol acyltransferase; HMGCS: 3-Hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase; HMGCR: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase; M3K: mevalonate-3-kinase; MVK: mevalonate kinase; M3P5K: mevalonate-3-phosphate-5-kinase; PMVK: phosphomevalonate kinase; MVD: diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase; IPK: isopentenyl phosphate kinase; IDI: isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase; DXS: 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase; DXR: 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase; ispD: 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; ispDF: 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; ispE: 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase; ispF: 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase; gcpE: (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase; ispH: (E)-4-Hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase.

In the biosynthesis of the terpenoid backbone, IPP and DMAPP are synthesized through two key pathways: the MVA and MEP pathways, both of which have critical regulatory points. HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) is the rate-limiting enzyme in the MVA pathway and a key regulatory site in terpenoid metabolism. In S. cerevisiae, overexpression of a truncated form of HMGCR is widely recognized as a crucial step for enhancing terpene synthesis efficiency. Lu et al.[50] screened various HMGCRs from different sources and achieved a production of 4.94 g/L of squalene using the most active truncated form, E. faecalis mvaE, in combination with cofactor engineering. Ye et al.[51] synthesized β-elemene in the unconventional microbe Ogataea polymorpha by transforming HMGCR into its more stable truncated form within the cytoplasm, regulating its overexpression with a strong constitutive promoter, which resulted in a slight increase in yield. In the MEP pathway, the enzymes DXS and DXR play crucial roles as branching points in carbon flow, making them important targets for regulation, particularly DXS. DXS is a thiamin diphosphate (ThDP)-dependent enzyme, and IDP has similar polar interactions with ThDP, allowing it to bind to DXS. Site-specific mutation and overexpression of the Populus trichocarpa DXS gene led to selective binding of ThDP and IDP, effectively regulating feedback inhibition of DXS and increasing its catalytic activity[52]. Overexpression of the DXS and DXR genes from Bacillus subtilis in E. coli resulted in approximately a two-fold increase in isoprene production[53]. In cyanobacteria cell factories, DXS regulation similarly controls carbon flux in the MEP pathway. Kudoh et al.[54] utilized the psbA2 promoter to introduce an additional copy of the DXS gene, leading to a 1.5-fold increase in β-carotene production in the improved strain.

After the synthesis of the basic building blocks IPP and DMAPP, their balanced expression becomes another critical factor influencing terpenoid biosynthesis. Following the modification of HMGCR, researchers also overexpressed the isomerization gene IDI, which catalyzes the interconversion of IPP and DMAPP, leading to a significant increase in β-elemene production[51]. When IDI was further overexpressed under the control of a strong promoter, β-carotene production in modified E. coli increased by 1.4-fold[55]. Chen et al.[56] employed error-prone PCR and site-directed saturation mutagenesis to evolve IDI, resulting in three mutant strains with significantly enhanced activity. This led to a 1.8-fold increase in lycopene production, reaching 1.2 g/L compared to the wild type. Additionally, three types of isoprenyltransferases—GPPS, FPPS, and GGPPS—catalyze the head-to-tail condensation of IPP and DMAPP, leading to the elongation of the C5 carbon chain and the subsequent synthesis of various terpenoids. Xie et al.[57] improved the expression of GGPPS (CrtE) through directed evolution, which increased lycopene production in S. cerevisiae by 2.2-fold, reaching 9.67 mg/g DCW. Chen et al.[58] further explored and compared the catalytic properties of GGPPS enzymes from different sources (CrtE, CrtI, and CrtB), optimizing their expression levels in combination.

Carvacrol and thymol are two common monoterpenoids widely found in plants such as Origanum compactum and Thymus pectinatus[18,21]. They are often used as flavoring agents in the food industry due to their distinctive odors, and they also exhibit antimicrobial properties. Poultry patties containing carvacrol and thymol showed a reduction in the number of viable bacteria after 7 d of storage at different temperatures, with more pronounced inhibition at lower temperatures[59]. Similarly, Shemesh et al.[60] used halloysite nanotubes encapsulated with carvacrol in an active antimicrobial packaging system, demonstrating antifungal efficacy against a wide range of fungi, and slowing the spoilage of raw fruits such as cherry tomatoes, lychees, and table grapes. Terpenoids also play a role in neuroprotection. Nerolidol, a sesquiterpenoid commonly found in Citrus sinensis, has a rose or orange blossom aroma and is used in cosmetics and detergents. It is approved as a safe food flavoring agent by the US Food and Drug Administration[23]. In terms of biological activity, Iqubal et al.[61] monitored neurotransmitter levels in a mouse model of cyclophosphamide-induced neuroinflammation, administering nerolidol via a nanolipid carrier. The treatment significantly reduced the levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholinesterase in the head, demonstrating significant neuroprotective effects.

Phenylpropanoids

-

Phenolic compounds with a natural composition containing one or more benzene rings linked by three-carbon chains, known as phenylpropanoids, are widely found in fruits, vegetables, tea, and other plants. These compounds exhibit various physiological functions, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and neuroprotective properties[62]. Due to their antioxidant properties and ability to protect against ultraviolet radiation, phenylpropanoids are commonly used as ingredients in cosmetics. For example, resveratrol has been shown to provide significant protective and antioxidant effects against cellular oxidative stress caused by diabetes[63]. Salidroside, besides being used in traditional medicine, can also serve as a supplement in fish farming to promote healthy fish reproduction[64].

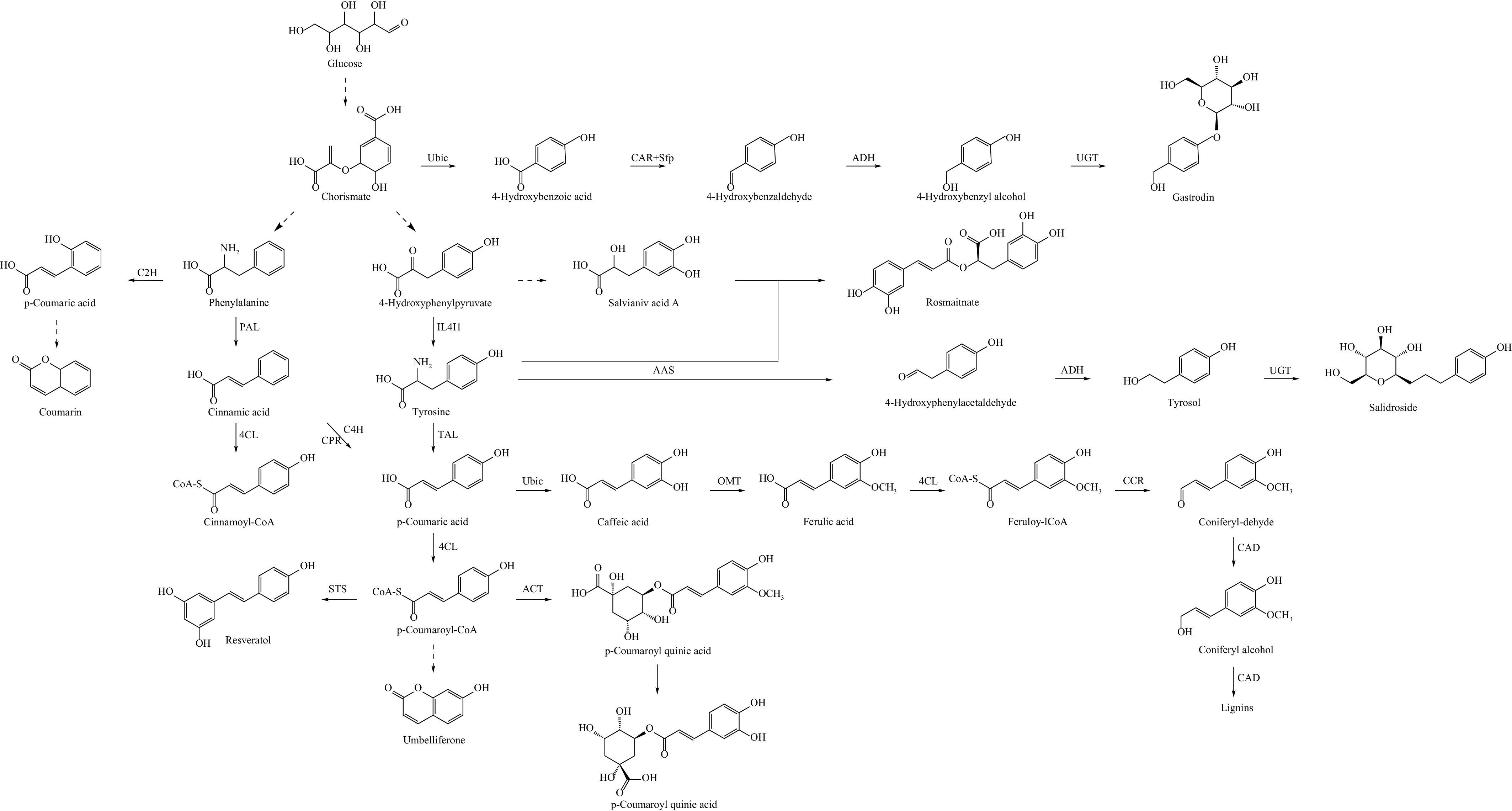

The synthesis of phenylpropanoids originates from the shikimic acid pathway, a secondary metabolic process unique to plants. In this pathway, shikimic acid is converted into aromatic amino acids through reactions like deamination, hydroxylation, and coupling. Phenylalanine aminolyase (PAL) is a crucial bridge between primary and secondary metabolism in plants and plays a significant role during plant growth and development. Overexpression of the endogenous PAL gene in sweet potato stimulated secondary xylem cell growth and increased chlorogenic acid accumulation in the leaves[65]. C4H was the first plant CYP450 enzyme identified, and it is highly active in various plant tissues. During the irreversible reaction catalyzed by C4H, the redox chaperone CPR is needed to supply electrons, facilitating the conversion of cinnamic acid to p-coumaric acid. In the subsequent synthesis step, using cinnamic acid as a substrate, competition may arise between C4H and 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligase (4CL) enzymes. Karlson et al.[66] silenced the C4H gene in tobacco cells using the CRISPRi system, which not only upregulated the expression of 4CL but also redirected metabolic flux toward the cinnamate glucosyltransferase (UGCT) pathway. This shift improved chlorogenic acid production by converting cinnamic acid to cinnamoyl D-glucose. Among the many enzymes involved, 4CL is central to various branches of the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway and exhibits high substrate specificity. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the isoenzymes encoded by At4CL1 and At4CL2 are closely related to lignin monomer synthesis[67], while At4CL3 activates p-coumaric acid as a substrate for chalcone synthase, which is involved in flavonoid biosynthesis. The effect of 4CL activity on lignin accumulation was investigated in Ganoderma lucidum using RNAi interference and overexpression experiments. The results showed a positive correlation between 4CL enzyme activity and lignin production, which is essential for the structure of G. lucidum cell walls and substrate formation[68]. Xiong et al.[69] constructed a mutant library of 4CL enzymes and used a specific resveratrol biosensor to screen for 4CL variants with high yields, achieving a 4.7-fold increase in resveratrol production.

The subsequent synthesis pathways of phenylpropanoid compounds vary, and the synthesis pathways of common phenylpropanoids are illustrated in Fig. 3. Chlorogenic acid, for instance, is a natural phenylpropanoid widely found in plant-derived foods, and is known for its numerous health benefits. However, the concentration of chlorogenic acid in plants is typically low, making it important to regulate its synthesis effectively. Hydroxycinnamoyl transferase (HCT) is a versatile acyltransferase, in addition to being a key enzyme in chlorogenic acid synthesis, HCT is involved in lignin monomer biosynthesis. Su et al.[70] conducted a metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis of over 200 mature peach cultivars and found a positive correlation between HCT expression levels and chlorogenic acid content. Another enzyme, hydroxycinnamate-CoA quinate hydroxycinnamoyl transferase (HQT), which belongs to the same family of transferases as HCT, significantly increased chlorogenic acid levels in tobacco leaves when HQT were overexpressed in Globe artichoke. Conversely, down-regulation of HQT1 resulted in a reduction in chlorogenic acid production, highlighting the key regulatory role of HQT[71]. In addition to structural genes, various transcription factors, such as WRKY, MYB, and bHLH, play significant roles in regulating chlorogenic acid synthesis. For example, overexpression of the TaWRKY14 transcription factor from Taraxacum antungense led to transgenic lines with increased chlorogenic acid content and higher expression of TaPAL1. This interaction was confirmed through a yeast one-hybrid assay, which demonstrated that TaWRKY14 binds to the W-box element of the TaPAL1 promoter[72]. In contrast, Zha et al.[73] found that overexpression of LjbZIP8, a transcription factor from Lonicera japonica, in transgenic tobacco suppressed the expression of PAL, resulting in reduced levels of neochlorogenic acid, chlorogenic acid, and cryptochlorogenic acid. This suggests that different transcription factors have distinct roles in regulating chlorogenic acid synthesis across various plants, and further analysis is needed to fully understand these specific regulatory mechanisms.

Figure 3.

Biosynthesis pathways of some common phenylpropanoids, which are synthesized through the tyrosine pathway and the phenylalanine pathway. C2H: coumarate-2-hydroxylase; PAL: phenylalanine ammoniase; 4CL: 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligase; C4H: cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase; CPR: cytochmme P450 reductase; IL4I1: Interleukin-4-Induced-1; TAL: tyrosine aminolyase; STS: Stilbene synthase; Ubic: chorismate--pyruvate lyase; CAR: carboxylic acid reductase; Sfp: phosphopantetheinyl transferase; ADH: alcohol dehydrogenase; UGT: uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferase; TYRDC-2: 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde synthase; OMT: o-methyltransferase; CCR: cinnamoyl-CoA reductase; HCT: hydroxycinnamoyl transferase; C3'H: p-Coumaroyl-shikimic acid/quinic acid 3′-hydroxylase.

Phenylpropanoids are well known for their antioxidant capacity, a common biological activity shared by many compounds in this group. Vanillin, a natural sweetener widely used in desserts and beverages, has strong antimicrobial properties, making it useful as a food preservative. It can even be incorporated into active packaging films to extend the shelf life of various foods, including fresh fruits and vegetables, frozen meats, and pasta[35]. Chlorogenic acid, a yellowish compound, can be prepared as a green or red pigment by reacting with different amino acids, making it a potent colorant in food matrices. Beyond its color properties, chlorogenic acid also exhibits strong antioxidant activity. For example, it slows the degradation of anthocyanins in blackberry juice through a co-pigmentation mechanism, allowing the juice to be stored at 4°C for 90 d when protected from light[74], making it an excellent food additive. Song et al.[7] assessed the free radical scavenging ability and iron ion reduction capacity of chlorogenic acid and its isomers in vitro, all of which showed varying degrees of antioxidant activity. Furthermore, animal cell experiments revealed that adding chlorogenic acid significantly reduced oxidative stress damage in broilers, improving their production performance. Gastrodia elata Blume, a traditional medicinal herb, is used in health foods, and gastrodin is one of its active ingredients. Wang et al.[75] demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of gastrodin in a mouse model of atopic dermatitis. Gastrodin reduced microglial activity by modulating the TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway in BV-2 cells.

Polysaccharides

-

Polysaccharides are a class of macromolecular compounds found widely in nature, consisting of monosaccharides linked by glycosidic bonds. In mushrooms, polysaccharides are the most active components, and exhibit various physiological functions, including anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral properties. Notable examples include lentinan and ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides, which have shown remarkable efficacy. Fruits are also rich sources of polysaccharides, such as longan and pomegranate polysaccharides, which possess natural antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. These polysaccharides are often added to nutritional health products as functional ingredients[39,76].

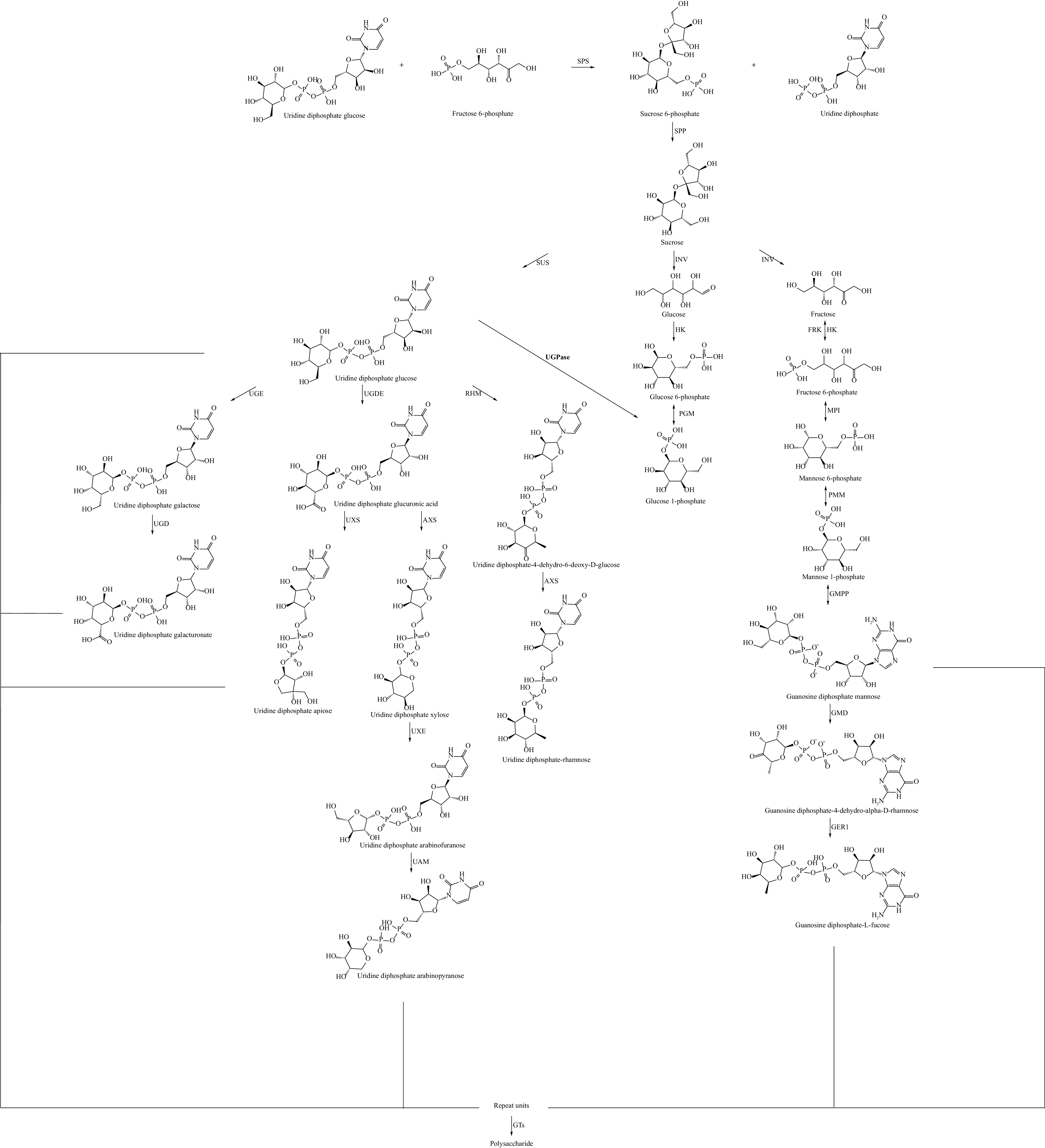

Polysaccharides exhibit diverse biochemical structures, with around 40–50 types of monosaccharides serving as their building blocks. In plants, polysaccharide synthesis begins with sucrose, produced via photosynthesis, which is converted into UDP-glucose through three pathways (Fig. 4). The first involves the direct generation of UDP-glucose via the action of the enzyme sucrose synthase (SUS). The second and third pathways are catalyzed by invertase (INV), where sucrose is broken down into glucose and fructose. These are then converted into their hexose phosphate forms (G6P and F6P) through hexokinase (HK) activity. F6P can be further converted into G6P, and together they are transformed into G1P with the involvement of phosphoglucomutase (PGM), ultimately forming UDP-glucose through UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UDPase). In the UDP-arabinose synthesis pathway, UDP-glucose is catalyzed into UDP-glucuronic acid by UDP-glucose dehydrogenase (UGDH). This intermediate can be used to synthesize UDP-xylose through UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase (UXS) or be further converted to UDP-apiose by UDP-D-xylose synthase (AXS), expanding the diversity of polysaccharide synthesis. After the formation of various UDP- and GDP-monosaccharides, these units are transferred to the growing polysaccharide chain through the action of glycosyltransferases (GTs), where they undergo dehydration and condensation, resulting in polysaccharide formation.

Figure 4.

Biosynthetic pathway of plant polysaccharides.Various sugar nucleotides form different repeating units, which are synthesized into polysaccharides under the action of GTs. SPS: sucrose phosphate synthase; SPP: sucrose phosphate phoshatase; SUS: sucrosesynthase; UGPase: UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase; UGE: UDP-glucose-4-epimerase; UGD: UDP-D-galactosedehydrogenase; UGDH: UDP-glucose dehydrogenase; UXS: UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase; GAE: UDP-glucoseA-4-epimerase; UXE: UDP-D-xylosel-4-epimeras; UAM: UDP-arabinopyranosemutase; AXS: UDP-D-Xylose synthase; RHM: UDP-rhamnose synthase; INV: invertase; HK: hexokinase; PGM: phosphoglucomutase; FRK: fructokinase; MPI: mannose-6- phosphate isomerase; PMM: phosphomannose isomerase; GMPP: GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase; GMD: GDP-D-mannose-4,6-dehydratase; GER1: GDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-mannose-3,5-epimerase-4-reductase; GT: glycosyltransferase.

The enzymes involved in polysaccharide synthesis are primarily categorized into three groups: synthetases, isomerases, and transferases. Among these, sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) is recognized as the key rate-limiting enzyme in the polysaccharide synthesis pathway. SPS catalyzes the formation of sucrose 6-phosphate, which subsequently leads to the production of sucrose. Seger et al.[77] demonstrated that overexpression of the SPS enzyme from corn in tobacco resulted in a significant increase in sucrose accumulation, which in turn promoted plant growth and development. Cyanobacteria, as photosynthetic organisms, can rapidly accumulate sucrose under salt stress. In an engineered strain of Cyanobacteria, the co-overexpression of SPS, sucrose phosphate phosphatase (SPP), and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGP) doubled the sucrose production[78]. UGPase is a critical enzyme in glucose metabolism across plants, animals, and fungi. It catalyzes the reaction between glucose 1-phosphate and uridine triphosphate (UTP) to form UDP-glucose and pyrophosphate, a key precursor in the synthesis of many polysaccharides. Peng et al.[79] investigated the synthesis of exopolysaccharides in G. lucidum using various medium components. They found that in cells synthesizing higher amounts of G. lucidum exopolysaccharides, the expression levels of key enzymes involved in the synthesis process were significantly elevated. Not only were the PGM and PGI genes that catalyze galactose and mannose upregulated, but the UGPase activity was also markedly enhanced compared to the control group. This demonstrates a strong correlation between mycelial polysaccharide content and the activity of key genes involved in the synthesis pathway, such as PGM, UGPase, and PGI. Similarly, in the synthesis of Lentinus edodes polysaccharides, the addition of sodium and calcium ions enhanced polysaccharide content by upregulating the expression of PGM, UGPase, and PGI[80]. Additionally, GTs are essential enzymes that catalyze the assembly of repeating monosaccharide units and the formation of glycosidic bonds. During the synthesis of G. lucidum polysaccharides, the overexpression of α-1,3-glucosyltransferase has been shown to regulate sugar donor synthesis, thereby increasing polysaccharide yield[81].

Polysaccharides, abundant in nature and both non-toxic and harmless, have a wide range of applications in the food industry, like jelly, jam, and yogurt. Due to their biodegradability and renewability, polysaccharides are also excellent candidates for use in food packaging. They can encapsulate target products when combined with nanomaterials, gels, or films. Furthermore, the rich physiological activity of polysaccharides allows them to serve as functional ingredients in nutraceuticals. For instance, Athmouni et al.[82] discovered that Periploca angustifolia polysaccharides reduce the production of reactive oxygen species by chelating cadmium ions, thereby protecting HepG2 cells from cadmium chloride-induced damage. Similarly, You et al.[83] isolated three polysaccharide components from edible fungi, which exhibited potent antioxidant activity by scavenging DPPH and hydroxyl radicals. In addition to their antioxidant properties, polysaccharides from Poria cocos have immunomodulatory effects. Pu et al.[84] found that P. cocos polysaccharides modulate the immune response by elevating calcium ion levels in macrophages, promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as NO, TNF-α, and IL-1β.

-

Currently, the production of corresponding plant natural products by introducing natural synthetic pathways into microorganisms represents a relatively advanced trend, though it remains in its developmental stage. After achieving the production target, the biosafety and practical application of the recombinant products are rarely described. These involve multidisciplinary comprehensive consideration, but also face challenges in various aspects.

Mining of key regulatory elements

-

The synthesis of plant-derived natural products is inseparable from special bioparts, but resources with known functions and availability for genetic modification are very limited. In addition to promoters and terminators that regulate gene expression during fermentation, CYP450 enzymes play a crucial role in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. However, there has been limited research on the crystal structure analysis of plant CYP450 enzymes. Since the functional activity and catalytic mechanisms of CYP450 enzymes are closely tied to their crystal structures, HMMTOP and TMHMM can be used to predict transmembrane regions and hydrophobicity to achieve soluble expression of target genes. Subsequently, secondary and tertiary structure modeling of the target enzyme is performed using computational tools such as AlphaFold, PSIPRED, and SWISS-MODEL, thereby obtaining a complete protein structural model. If possible, a database summary was established to compare and analogize with the similar structures from various angles, thus laying the foundation for the molecular modification and functional expression of CYP450 enzymes. In the heterologous production of plant-derived natural products, expressing plant CYP450 enzymes in bacterial hosts presents challenges, due to the absence of essential redox partners and electron transfer organelles in bacteria. Addressing this issue will require the development of new protein structure prediction tools, as well as the integration of bioinformatics approaches to expand the crystal structure analysis of plant CYP450 enzymes and other key biosynthetic enzymes. By clarifying the structure-activity relationships of these enzymes, researchers can tackle the electron transfer limitations in bacterial hosts. This remains a key challenge for future research in the field.

Optimization of cell factory performance

-

In addition to the modifications made around key enzymes, the optimization of microbial cell factory performance is also an angle that cannot be ignored. There are many important organelles in cells; by regulating and fully utilizing their space, it is possible to effectively mitigate spatial effects between proteins. This compartmentalization strategy—one that involves localizing related biological components to specific organelles—is increasingly being adopted. Thodey et al.[85] anchored codeinone reductase, a key gene for morphine synthesis, to the endoplasmic reticulum via a localization peptide, which not only increased the rate of morphine production, but also decreased the synthesis of by-products. While there are advantages to this strategy in terms of increased synthesis efficiency as well as product stability, it may also lead to a more complex distribution of products inside the cell, which increases the difficulty of products that accumulate inside the cell for substances with longer synthetic paths. Similarly, the targeted modification of cell factories cannot be achieved without efficient gene editing techniques. By removing some of the unnecessary internal metabolic pathways, it is possible to provide more energy for strain production, or more binding space for the target enzyme to function. Arendt et al.[86] used CRISPR/Cas9 method to knockout phosphatidic acid phosphatase-encoding PAH1 gene in S. cerevisiae, which expanded the space of endoplasmic reticulum and increased the production titers of various terpenoids. This may be due to the fact that CYP450 enzymes located in the endoplasmic reticulum have more room to attach.

In addition to exogenous means, it is also crucial to improve the toxicity tolerance of the microbial cell factory itself. Differences in the metabolic fitness of many plant-derived natural products and microorganisms may result in cell growth restriction. In addition to the currently commonly used cell factories, mining and developing more tolerant microbial cell chassis can alleviate the toxicity of the accumulation of intermediary products to the cells on the one hand, and on the other hand, it also has a certain benefit to the cell's ability to resist contamination, especially the synthesis of products with longer pathways.

Industrial large-scale production

-

After the optimal performance of the recombinant microorganism is constructed in the laboratory, it may produce different effects from shake flask to large-scale production fermenter. Due to the larger volume of industrial fermenters, the precise control over conditions such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH is somewhat reduced. For microbial cells, the shear forces generated by faster stirring rates and excessively high concentrations of substrates or products may also inhibit the strains. These variations result in certain differences between fermenters and shake flask culture systems in growth and production performance. Therefore, further condition optimization may be needed[87]. During the synthesis of hispidin, the addition of the precursor caffeic acid triggers a sudden pH shift. In shake flasks, pH stabilization relies solely on the medium's inherent buffering capacity. However, real-time pH sensors installed in the fermenter enable precise pH control, thereby preventing damage to enzyme activity[88]. To obtain a sufficient number of organisms and maintain the continuity of production, strains in industrial production may undergo multiple generations, which poses a risk to the production performance of the strain and even to the integrity of the genes carried. Therefore, before large-scale production, the researchers can conduct a medium-sized pilot experiment; at the same time, the more suitable directional evolution of strains for industrial production can appropriately reduce the risk and cost loss of large-scale production. Researchers utilized the synergistic effect of air aeration, stirring, and vegetable oil as the oxygen carrier in a 5 L fermenter to precisely regulate dissolved oxygen levels, optimizing the metabolic flow of the strain in a targeted manner. Ultimately, this resulted in a 34.3% increase in the total triterpenoid yield of Sanghuangporus vaninii YC-1[89]. In addition, advanced bioreactor designs should also be updated to facilitate more stable control of production conditions.

Biosafety and application of recombinant products

-

In recent years, the microbial synthesis of plant-derived natural products has gained momentum. However, the practical applications of these microbially synthesized products remain underexplored. For instance, Denby et al.[90] constructed a synthetic pathway in S. cerevisiae for producing linalool and geraniol, which are key contributors to the 'hoppy' flavor and aroma in beer. To test its feasibility, the engineered yeast strain was used in large-scale brewery production, and sensory evaluations revealed that the flavor and fragrance it produced were superior to those from traditional Cascade hop preparations. Due to the lack of guarantee of biosafety of the strain, its application in industrial production is limited. Self-cloning technology is a genetic improvement method of yeast without introducing any exogenous DNA, and its biosafety can be directly applied to the food industry. By constructing the self-cloning module of S. cerevisiae, the alcohol dehydrogenase II gene locus was damaged, and the GSH1 and CUP1 gene were overexpressed, which significantly reduced the acetaldehyde level and inhibited beer aging. Sensory evaluation also confirmed that the recombinant brewed beer was more palatable[91]. The edible nature of yeast simplifies the practical application of microbial recombinant products in such cases. However, significant challenges remain, particularly in the purification and safety of recombinant products. For example, in the production of anthocyanins, a water-soluble natural pigment, there is a lack of effective separation and extraction methods for this substance. Furthermore, the use of anthocyanins as food colorants raises additional concerns related to food safety, thus restricting their broader application. Future approaches may focus on strategies such as encapsulation or stacking complexes to assist in the separation of water-soluble compounds like anthocyanins.

Additionally, horizontal gene transfer may occur in modified microorganisms carrying exogenous genes. Thorough activity evaluations and clinical safety tests of these synthetic products will be essential to ensure their practical applications in food, nutrition, and health care products. On the regulatory side, it is crucial to establish comprehensive and stringent standards for the market entry of recombinant products. Such as the safety and sustainability of the microorganisms themselves, the impact of by-product and waste post-treatment on the ecology, and whether the destination after entering the market and the health status of users are within the ideal range, and so on. This will not only streamline the approval process but also help researchers design microbial cell factories that align with regulatory requirements.

-

Plant-derived natural products hold immense potential, with many anticancer and antitumor drugs derived from specific natural compounds. Due to problems such as growth restrictions, resource consumption, and environmental pollution, relying on direct extraction from plants or chemical synthesis is limited. The rapid growth and controlled reaction conditions of microorganisms make it the most potential plant-derived natural products replacement production plant.

Research into the mechanisms underlying the activity of natural products spans multiple fields. At the molecular biology level, alterations in gene or protein expression related to cell cycle regulation, or signaling pathways can be investigated using transcriptomics, real-time quantitative PCR, and mass spectrometry. From a cellular perspective, techniques such as Western blotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are employed to detect changes in activity, or expression of key molecules involved in cellular signaling pathways. On the biochemical level, targeted, and untargeted metabolomics analyses are used to reveal the effects of natural products on metabolic regulation within organisms. It is believed that in the future, through continued research on modified bioparts and biotechnology, improving the corresponding laws and regulations, it can further enhance the practicality of microbial cell factories, and is of great significance to reduce environmental pollution, improve production efficiency, and even improve human health.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472368), the organization Department of Liaoning Province 'Xingliao Talent Project' (XLYC2202023), and the Zhejiang Province Leading Wild Goose Project (2023C02046).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, writing-original draft: Li L; writing-review and editing: Shu C, Li B; investigation: Wang L, Zeng W; resources: Tian J; software: Wang Z; supervision: Zhao Q; funding acquisition: Li B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li L, Shu C, Tian J, Zeng W, Wang L, et al. 2026. Synthesis, function, and application of plant-derived natural products in food. Food Innovation and Advances 5(1): 13−25 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0052

Synthesis, function, and application of plant-derived natural products in food

- Received: 22 July 2025

- Revised: 28 September 2025

- Accepted: 12 November 2025

- Published online: 27 January 2026

Abstract: Natural products are widely distributed across various organisms, and exhibit potent physiological activities. Among these, plant-derived natural products are extensively utilized in the food, pharmaceutical, and healthcare industries. Traditional extraction methods primarily rely on plant extraction but suffer from drawbacks such as low yield, long growth cycles, and high resource consumption. Consequently, microbial fermentation technology has emerged as an alternative solution, offering advantages including the ability to utilize abundant raw materials and its environmentally friendly and sustainable characteristics. This review summarizes recent advances in the biosynthesis and functional mechanisms of four classes of plant-derived natural products—alkaloids, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, and polysaccharides—while also examining the challenges and future prospects for their practical applications.