-

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale Weber ex F. H. Wigg.), a perennial herb from the Asteraceae family, is widely found in the warm regions of the Northern Hemisphere and has long been recognized for its medicinal and nutritional value[1]. Dandelion is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries due to its proven health benefits[2], including anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antibacterial, and immunomodulatory effects, along with tumor suppression, cancer prevention, and blood sugar regulation[3−8].

With the advancement of research in natural products and phytochemistry, the chemical composition and biological activities of dandelion have gained widespread attention. Its major constituents, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, polysaccharides, and quinones, have been shown to exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antitumor activities, with varying health benefits among different components[9,10]. Among them, phenolic acids are widely recognized for their capacity to neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative stress, contributing to both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory responses[11]. Flavonoids inhibit the synthesis and activity of pro-inflammatory mediators, improving endothelial function[12,13]. For instance, research has shown that triterpenoids can inhibit the expression of iNOS and COX-2 enzymes, reduce the production of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, NO, PGE2, IL-6, and IL-1β, and suppress inflammatory responses by blocking signal transduction in the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and MAPK pathways[14]. Huwait et al. found that quercetin inhibits atherosclerotic inflammation by reducing ICAM1 and MCP-1 expression in THP-1 macrophage models[15]. Another study by Yoo et al. observed that rutin inhibits HMGB1-induced inflammation in human endothelial cells by inhibiting HMGB1 release, decreasing TNF-α and IL-6 production, and reducing NF-κB and ERK1/2 activity[16]. This research has proven that polyphenol-rich dandelion extracts primarily exhibit strong antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory properties.

Dandelion contains various bioactive compounds, but conventional mass spectrometry-based identification and functional evaluation methods have not fully clarified its anti-inflammatory components or their dose–response relationships when these compounds coexist. To address this, this study used a network pharmacology approach to screen anti-inflammatory components of dandelion and identify potential inflammatory signaling pathways[17−21]. Based on the screening results, selected polyphenols were further evaluated in cell-based assays. To explore underlying mechanisms, proteomic and transcriptomic analyses, together with integrative multi-omics, were conducted to characterize the expression patterns of pathway-related proteins and transcription factors after treatment with the identified compounds. Additionally, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), and Western blot (WB) analyses were used to verify key molecular targets and validate gene and protein expression changes. Computational chemistry tools were also applied to investigate the molecular interactions and binding characteristics of the active compounds with their targets. This study provides theoretical insights and empirical evidence, laying a scientific foundation for the industrial application of dandelion in functional foods and pharmaceuticals targeting inflammatory and metabolic disorders.

-

Tissue culture human monocyte-like cell line 1(THP-1) cells were obtained from the ATCC cell bank (Rockville, Maryland, USA). Quercetin (97.3%, A10009), and caffeic acid (99.8%, A10056) were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) were obtained from the Cayman Chemical Company (Michigan, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and penicillin-streptomycin solution (100×) were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (PMA) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All chemicals and reagents used in the study were of analytical grade, with a purity of more than 99%.

Function factor screening

Network pharmacology analysis

-

Data were integrated from high-throughput experiments, the reference-guided traditional Chinese medicine database (HERB)[22], the traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology database and analysis platform (TCMSP)[23], and the Chinese Natural Product Chemical Constituents Database, to identify bioactive components of dandelion and their targets. The molecular structures of the compounds were confirmed by the PubChem database. Additionally, inflammation-related gene information was collected from the gene-disease association database (DisGeNET), and the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) to obtain disease targets. Through the Universal Protein (UniProt) database, the targets associated with inflammation and dandelion components were standardized at the gene level. A Venn diagram tool was used to intersect these targets, and an active component–disease–target network was initially constructed. To explore relationships among target proteins, the anti-inflammatory targets were imported into the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database to extract interaction data, which were then visualized as a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network in Cytoscape (Version 3.7.2). The network was rendered in Cytoscape with the Generate style from statistics tool, mapping node degree to visual attributes to obtain the final PPI graph. Hub genes were ranked using the cytoHubba plugin with the maximal clique centrality (MCC) method, and the top 10 genes were selected. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the anti-inflammatory targets was performed using Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID)[24], while Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)[25] pathway analysis was conducted to predict the enriched pathways and key anti-inflammatory active components.

Molecular docking validation

-

The Ledock docking software was employed to facilitate the docking of anti-inflammatory compounds with target proteins identified by the network pharmacology analysis (CCL2, CXCL8, F3, ICAM1, IL1A, IL1B, IL6, SELE, PAI-1, THBD, TNF). Subsequently, the docking parameters for binding sites and binding methods were set to default values, and the 20 poses with the lowest binding energy were generated for further analysis. The minimum binding energies for various anti-inflammatory components with their corresponding targets were calculated, allowing for the preliminary screening of combinations exhibiting optimal binding affinity based on these energy values. Following this analysis, the docking poses of active component-target complexes were opened using Discovery Studio 4.5, and 2D schematic diagrams were generated to illustrate the binding sites and interactions of dandelion anti-inflammatory components with their corresponding targets.

Cell culture and treatment with screening for functional factors

THP-1 cell culture

-

The human monocytic cell line THP-1 was selected because it can be differentiated into macrophage-like cells that express RAGE and show reproducible inflammatory responses to AGEs. Macrophages differentiated from THP-1 cells are commonly used as a human in vitro model of AGE-RAGE signaling and to assess the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of experimental interventions[26]. During the revival and subculture of THP-1 cells, the cryopreserved cells were first removed from liquid nitrogen and rapidly thawed in a 37 °C water bath for approximately 2 min. The thawed cells were then transferred to a centrifuge tube containing 84% RPMI-1640 medium, 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. After gentle pipetting to mix, the cells were centrifuged at 1,000 r/min for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The cell pellet was resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and seeded into a culture flask. The cells were incubated in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 48 h, with cell growth monitored during the process. For subculture, the cells were gently pipetted to disperse, the old medium was partially removed, and fresh medium (89% RPMI-1640, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) was added. The culture was continued for another 48 h before the next subculture.

Function factor treatment

-

In the induction and viability assay of THP-1 cells, cells in good growth condition and logarithmic phase were selected, and their concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/mL with complete medium. A total of 2 mL of cell suspension was added into each well of a six-well plate and treated with PMA at final concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 ng/mL for 48 h, and successful induction was confirmed by microscopic observation of cell adherence and pseudopodia formation[27]. The MTT assay was then used to assess cell viability, as described by Ayele et al.[28]. MTT, upon entering the cells, is reduced by mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase in viable cells to form insoluble formazan, which accumulates in the cells. After 2 h, formazan was dissolved in DMSO, and absorbance was measured at 490 nm to calculate cell viability. For polyphenol treatments, THP-1 cells were exposed to quercetin and caffeic acid mixtures at five discrete total-polyphenol concentrations: 0.004, 0.04, 0.08, 0.16, and 0.32 mg/mL.

Measurement of exosomal factor expression

-

THP-1 cells in good growth condition were seeded into six-well plates at 2 mL per well. After 48 h of PMA induction, polyphenols were added for 1 h of incubation, after which the polyphenol solution was discarded. Subsequently, 100 μg/mL of AGEs were added, and the cells were cultured for 24 h. After incubation, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube[14,29]. The concentrations of cytokines were then measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit[30], and data analysis was performed using ELISAcalc software, with a four-parameter logistic model used for standard curve fitting.

Transcriptomics analysis

-

THP-1 cells (2 mL per well) were seeded into a six-well plate, induced with PMA for 48 h, and treated with 100 μg/mL AGEs for 24 h. After removing the medium, cells were washed twice with PBS, lysed with TRIzol, and stored at -80 °C. Following RNA extraction, eukaryotic transcriptome sequencing and subsequent genome alignment were performed, with RNA concentration and purity measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and integrity assessed via RNA agarose gel electrophoresis or an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., California, USA). Total RNA (≥ 1 µg) was used to construct a library using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs Inc, Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA). Poly (A) mRNA was enriched using Oligo (dT) magnetic beads and fragmented by divalent cations, serving as the template for cDNA synthesis. The resulting library underwent amplification and purification, followed by quality assessment with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, employing the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit. The overall library concentration was determined using the PicoGreen assay, while the effective concentration was accurately quantified through qPCR.

Proteomics analysis

-

THP-1 cells were seeded at 2 mL per well in a six-well plate, induced with PMA for 48 h, incubated with polyphenols for 1 h, and then treated with 100 μg/mL AGEs for 24 h. The supernatant was collected into centrifuge tubes for further analysis. The cells were washed twice with 1 mL PBS, and the liquid was discarded. Protein extraction was performed using the SDT lysis buffer (4% (w/v) SDS, 100 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.6, 0.1 M DTT), and protein quantification was conducted using the BCA method. Proteomic analysis, including peptide digestion, mass spectrometry, and bioinformatics analysis, was subsequently carried out. Raw data from all samples underwent quality assessment before proceeding with further screening and analysis.

PCR analysis

-

The mRNA sequences of ICAM1, IL1B, CXCL8, and THBD from human monocytic leukemia cells were obtained from GenBank. Primers were designed and synthesized based on these sequences, dissolved in ddH2O to 100 µM, and stored at −20 °C. Cells were treated as described in transcriptomics analysis, then the culture medium was removed, cells were washed twice with PBS, lysed, and total RNA was extracted and quantified. Total RNA was treated with the EvoM-MLV reverse transcription kit (Aikere Biotechnology) following the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was removed using 5X gDNA Clean Reaction Mix, and the total RNA volume was adjusted to the reaction volume with RNase-free water. The mixture was incubated at 42 °C for 2 min, and then cooled to 4 °C. The mixture was used for reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA by adding 5X Evo M-MLV RT Reaction Mix, following the kit protocol. The PCR cycling conditions were 37 °C for 15 min, 85 °C for 5 s, then 4 °C. The resulting cDNA was used as a template for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). A 2× SYBR Green Pro Taq HS Premix was used for amplification in a 20 µL reaction in a 96-well plate, containing 10 µL 2× SYBR Green Pro Taq HS Premix, 3 µL cDNA template, 0.4 µL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM), and RNase-free water to 20 µL. The qPCR program was set as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. The relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method.

WB analysis

-

Protein lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, after which the supernatant containing proteins was collected, and the protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein quantification kit[31]. Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto and separated on precast gels, then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes and blocked with skim milk at room temperature for 2 h. The membranes were then incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C for 10 h, followed by a 2 h incubation with the secondary antibody and subsequently visualized.

Molecular docking and semi-empirical calculation of quercetin, caffeic acid, and receptor proteins

-

PDB files of quercetin, caffeic acid, AGEs (pyrrole, Carboxymethyl lysine [CML], and Carboxyethyl lysine [CEL]), and target proteins such as Receptor of Advanced Glycation Endproducts (RAGE) were downloaded from PubChem and RCSB PDB, respectively. AutoDock was used to perform single-ligand and multi-ligand docking of quercetin, caffeic acid, and AGEs with structurally optimized RAGE, obtaining binding sites and binding energies. Multi-ligand simultaneous docking was carried out using Vina software (v1.2, Molecular Graphics Lab) to analyze the structure and binding energy of the common binding site, to which the phenolics all tended to bind. Water molecules were removed from the protein structures, and polar hydrogen atoms, along with Gasteiger partial charges, were added. Input files for both proteins and phenolic compounds were prepared using MGL Tools, keeping all docking parameters at their default values. The pose exhibiting the lowest binding energy was chosen for further analysis. Semi-empirical calculations were performed using MOPAC with the PM6-D3H4 method under an implicit water model (dielectric constant EPS = 78.4), optimizing only atoms within 10 Å of the ligand while fixing the others to reduce computation time, and calculating binding energies before and after ligand binding. The change in the standard heat of formation (kcal/mol) before and after ligand binding was then used to estimate the variation in binding energy between the target protein and its downstream interaction partners, allowing assessment of whether ligand binding affected protein-protein interactions.

Statistical analysis

-

All the experiments were repeated three times, and the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The data were processed and analyzed using Origin 8.0 software (OriginLab, Northampton, USA), and statistical analysis was carried out by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Duncan's multiple range test was used to determine the significance of the differences among the means (differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05).

-

A total of 56 bioactive components from dandelion were collected from multiple public databases, including HERB (Supplementary Table S1). The potential targets of these compounds were predicted using the TCMSP platform, resulting in 243 targets involved in biological processes such as inflammation, cancer, cell cycle control, and neural regulation. These targets were annotated in UniProt to obtain their corresponding gene information (Supplementary Table S2). All data were then used to construct a bioactive component-target network using Cytoscape 3.7.2 (Supplementary Fig. S1). To identify inflammation-related targets, data from DisGeNET and CTD databases were integrated. After removing duplicates, 185 unique genes associated with inflammatory processes were retained (Supplementary Table S3), forming the basis for the inflammation-specific target network (Supplementary Fig. S2). This figure (Supplementary Fig. S2) illustrates the overall interaction network of inflammation-related targets. By comparing the predicted targets of dandelion bioactive compounds with targets associated with inflammation, eight compounds were identified as potentially modulating inflammatory responses. These included quercetin, caffeic acid, rutin, luteolin-7-O-glucoside, mythl p-hydroxyphenylacetate, palmitic acid, beta-sitosterol and 4-hydroxy-4-methyl-2-pentanone, with a total of 29 corresponding targets (Table 1). The selection of these compounds is further supported by existing studies, which have shown that quercetin, caffeic acid, and rutin can suppress inflammatory signaling, reduce oxidative stress, and offer protective effects against inflammation-induced cellular damage[16,32,33].

Table 1. Dandelion active component-inflammatory target-gene information and AGE-RAGE pathway enrichment of target-effective fraction.

No. Component Inflammation target UniProt ID AGE-RAGE pathway 1 Tyranton Prostaglandin G_H synthase 1 COX1 No 2 Tyranton Ornithine carbamoyltransferase, mitochondrial OTC No 3 Caffeic acid Beta-2 adrenergic receptor ADRB2 No 4 Caffeic acid Tumor necrosis factor TNF Yes 5 Luteolin-7-o-glucoside Nitric oxide synthase, inducible NOS2 No 6 Methyl 5-hydroxyphenylacetate Thrombin F2 No 7 Palmitic acid Interleukin-10 IL10 No 8 Palmitic acid Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate 3-phosphatase and dual-specificity protein phosphatase PTEN PTEN No 9 Quercetin Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit, gamma isoform PIK3CG No 10 Quercetin Interleukin-6 IL6 Yes 11 Quercetin Heme oxygenase 1 HMOX1 No 12 Quercetin Tissue factor F3 Yes 13 Quercetin Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 ICAM1 Yes 14 Quercetin Interleukin-1 beta IL1B Yes 15 Quercetin C-C motif chemokine 2 CCL2 Yes 16 Quercetin E-selectin SELE Yes 17 Quercetin Interleukin-8 CXCL8 Yes 18 Quercetin Thrombomodulin THBD Yes 19 Quercetin Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 SERPINE1 Yes 20 Quercetin Interferon gamma IFNG No 21 Quercetin Interleukin-1 alpha IL1A Yes 22 Quercetin Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 NFE2L2 No 23 Quercetin Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 3 NR1I3 No 24 Quercetin C-reactive protein CRP No 25 Quercetin Osteopontin SPP1 No 26 Beta-sitosterol Glucocorticoid receptor NR3C1 No 27 Rutin C5a anaphylatoxin chemotactic receptor C5AR1 No 28 Rutin C5a anaphylatoxin chemotactic receptor C5AR2 No 29 Rutin Integrin beta-2 ITGB2 No Note: The AGE-RAGE pathway column indicates whether the inflammatory target is involved in the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway (Yes = involved, No = not involved). The 29 intersecting targets were submitted to STRING for PPI analysis and subsequently visualized (Supplementary Fig. S3). The resulting network comprised 26 nodes and 169 edges. Edge colors indicated evidence types: green, gene adjacency; red, putative gene fusions; purple, gene co-occurrence; black, gene co-expression; and light purple, protein homology. Taken together, these interaction categories suggest that the targets are functionally connected and may influence one another's expression or activity through regulatory or structural links.

Further GO enrichment analysis was performed on the 29 intersecting targets, resulting in the identification of 217 enriched terms, which were classified into three main categories: Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF) and Cellular Component (CC). Among these, 15 key biological processes were selected for further analysis based on p <0.05, and the number of enriched genes (Supplementary Table S4), leading to visualization in a GO enrichment plot (Supplementary Fig. S4), which highlights the major biological processes most closely related to the anti-inflammatory activity of dandelion. Fifteen genes were enriched in the inflammatory response process, accounting for 53.5% of all enriched genes, with the lowest p-value and highest statistical significance.

KEGG enrichment of the 29 intersecting targets identified 65 significant pathways. Based on the p < 0.05 and the number of enriched genes, the top 10 were selected for visualization (Supplementary Fig. S5). Among them, the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications contained 11 enriched targets, including F3, ICAM1, IL1A, IL1B, CXCL8, SERPINE1, CCL2, SELE, THBD, and TNF (Supplementary Fig. S6), all of which were influenced by quercetin and caffeic acid (Table 1). The AGE-RAGE pathway is crucial in many pathological processes, with its core mechanism involving AGE accumulation and binding to RAGE. AGEs are generated through non-enzymatic reactions between reducing sugars and proteins or amino acids, accumulating in the body and affecting physiological functions[34,35]. Binding of AGEs to RAGE activates signaling that triggers NF-κB and MAPK pathways, enhancing signal transduction, promoting inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress, and contributing to disease pathogenesis[36−38]. Based on these findings, further experimental investigations will be conducted to explore the regulatory effects of quercetin and caffeic acid on the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway.

Molecular docking results for quercetin and caffeic acid with their target proteins are summarized in Supplementary Table S5. Binding energy was used as the primary indicator of interaction stability and affinity, with lower values reflecting stronger binding and more stable conformations. For THBD, nine docking poses of quercetin showed binding energies below –4.0 kcal/mol, indicating stable, high-affinity binding. Among all targets, IL1A and IL1B displayed the lowest and identical binding energies, suggesting the strongest affinity, followed by PAI-1, CXCL8, and ICAM1. For SELE, ten docking poses had binding energies below –2.5 kcal/mol, indicating detectable but weaker binding. Caffeic acid also exhibited strong binding to TNF, with nine conformations showing binding energies below –4.0 kcal/mol, consistent with stable, high-affinity interactions.

Molecular docking further clarified the interaction mechanisms between ligands and protein targets (Supplementary Fig. S7), showing that both quercetin and caffeic acid mainly engage through hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Quercetin formed multiple hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts with IL1A and IL1B, PAI-1, CCL2, CXCL8, ICAM1, F3, and IL6, and in some complexes also participated in metal coordination (e.g., with CCL2 and SELE). Caffeic acid showed stable binding to TNF through hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and salt bridges. Overall, both quercetin and caffeic acid exhibited strong binding to their target proteins, supporting their potential inhibitory effects and anti-inflammatory activity, and providing a basis for further studies on their combined use as anti-inflammatory agents.

Screening of quercetin and caffeic acid combinations for anti-inflammatory activity in THP-1 cell

-

As shown in Supplementary Fig. S8, the differentiation of THP-1 cells varied depending on the concentrations of PMA. At 25 ng/mL, cells exhibited low density and poor adhesion, with no obvious pseudopodia formation. Possibly due to incomplete differentiation, most cells remained suspended or weakly attached, resulting in cell loss during medium removal or washing. When the PMA concentration was increased to 50 ng/mL, a marked improvement in cell attachment and morphology was observed. Cells adhered well to the surface and extended pseudopodia, indicating effective differentiation and favorable growth conditions at this concentration. At 75 ng/mL, although pseudopodia formation remained apparent in most cells, the overall cell density declined compared to the 50 ng/mL group. The reduction was likely caused by the higher concentration, reducing adhesion, and causing cell loss during washing. When the concentration reached 100 ng/mL, the number of cells observed was markedly reduced, likely due to increased cytotoxicity at this concentration, causing cell death and detachment during washing.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. S9, MTT assay results indicated that different ratios of quercetin and caffeic acid solutions influenced cell viability. Within the range of 0.004–0.08 mg/mL, all tested solutions significantly promoted cell survival, suggesting that polyphenols offered protective effects against AGEs-induced macrophage injury when applied at appropriate concentrations. At concentrations above 0.08 mg/mL, the viability of cells treated with 100% caffeic acid decreased significantly, likely due to cytotoxic effects at high concentrations. Statistical analysis showed significant differences in cell viability among different quercetin/caffeic acid ratios at each concentration. Considering these results, the quercetin and caffeic acid mixed solution at a concentration of 0.08 mg/mL was chosen to ensure that different ratios did not cause cellular damage while maintaining optimal protective effects for further investigation of their anti-inflammatory potential.

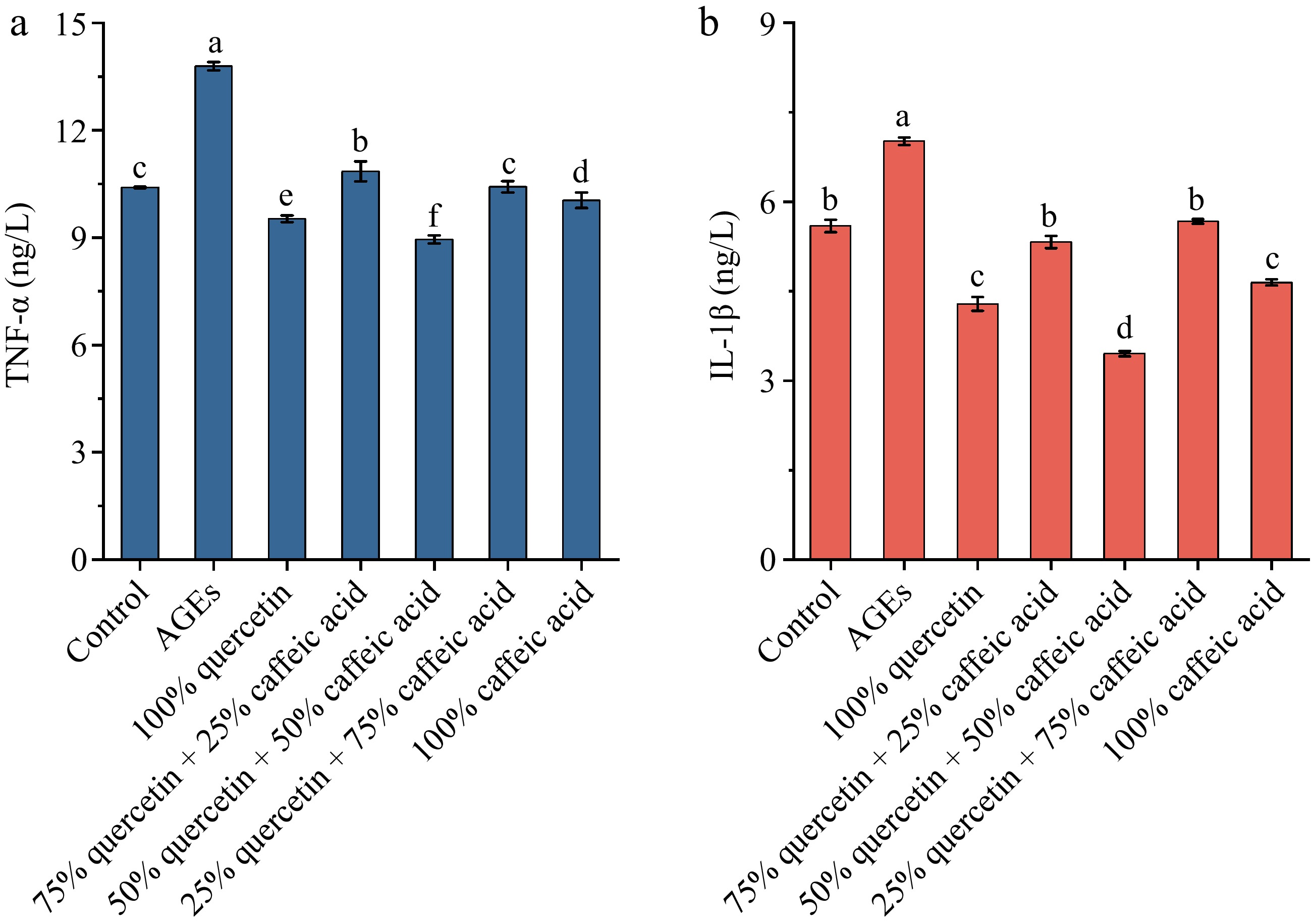

TNF-α is a key inflammatory cytokine secreted by macrophages upon stimulation and plays a central role in promoting the transcription of inflammation-related genes. Through interactions with membrane receptors that activate inflammatory signaling pathways, ultimately triggering an inflammatory response[39]. IL-1β, another major pro-inflammatory cytokine released by macrophages, is capable of inducing inflammatory responses across a wide range of tissues and organs[40]. Due to their pivotal roles in inflammation, the inhibition of TNF-α and IL-1β secretion is widely used as an indicator for evaluating the anti-inflammatory efficacy of bioactive compounds[41]. As shown in Fig. 1, different ratios of quercetin and caffeic acid exhibited varying inhibitory effects on TNF-α and IL-1β secretion in macrophages stimulated by AGEs. In the control group, the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β were 10.40 ng/L and 5.59 ng/L, respectively. Exposure to AGEs led to a marked increase in both cytokines, with levels rising to 13.79 ng/L for TNF-α and 7.01 ng/L for IL-1β, confirming the successful establishment of the inflammatory cell model. Following treatment with different compound ratios, the observed TNF-α levels were 9.52 ng/L in the 100% quercetin group, 10.85 ng/L in the 75% quercetin + 25% caffeic acid group, 8.94 ng/L in the 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid group, 10.42 ng/L in the 25% quercetin + 75% caffeic acid group, and 10.04 ng/L in the 100% caffeic acid group. Corresponding IL-1β levels were 4.28, 5.32, 3.45, 5.67, and 4.64 ng/L, respectively. All treatments significantly reduced cytokine secretion compared to the AGEs group. As shown in Supplementary Table S6, one-way ANOVA indicated significant group effects for TNF-α (F(6,14) = 276.77), and IL-1β (F(6,14) = 613.82). Among the five groups, the 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid mixture showed the most pronounced inhibitory effect on both TNF-α and IL-1β secretion, followed by the 100% quercetin and 100% caffeic acid treatments.

Figure 1.

The effect of different ratios of quercetin and caffeic acid on the expression of inflammatory factors (a) TNF-α, and (b) IL-1β. Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

These observations suggest that quercetin and caffeic acid act cooperatively in modulating inflammatory responses, with the 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid mixture exerting the strongest inhibitory effect on TNF-α and IL-1β secretion among the tested ratios. This is in line with previous reports in which combinations of polyphenolic compounds showed enhanced anti-inflammatory effects compared with single compounds[42,43]. Moreover, the enhanced effect of the quercetin–caffeic acid co-treatment could be due to their complementary mechanisms in modulating different inflammatory pathways. Quercetin, a flavonoid, has been reported to inhibit NF-κB signaling, thereby reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. On the other hand, caffeic acid, a phenolic acid, has been shown to suppress the activation of the MAPK pathway, which is also involved in the production of inflammatory mediators[44]. Together, these compounds may target multiple inflammatory pathways, resulting in a more potent anti-inflammatory effect than when used alone.

This study has limitations. Because of experimental and resource constraints, transcriptomic and proteomic profiling were restricted to the 100% quercetin, 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and 100% caffeic acid groups. Although the cytokine data suggest that the 50:50 mixture has the strongest anti-inflammatory effect among the tested ratios, further omics analyses of additional combinations are needed to define the optimal ratio and confirm true pharmacological synergy.

Omics data analysis

-

Transcriptomics and proteomics are essential omics technologies for investigating gene expression regulation and functional dynamics in biological systems. In the research of related inflammation, these approaches enable a systematic elucidation of molecular mechanisms underlying inflammatory responses, identifying key regulatory factors and discovering potential therapeutic targets, thereby providing a theoretical basis for developing strategies to treat inflammatory diseases.

Transcriptomic analysis

-

Across all groups, a total of 20,036 transcript samples were detected. Correlation in gene expression among biological replicates within each group served as a primary measure of data reliability and sample consistency, where higher correlation indicates greater similarity among samples. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S10, the distribution pattern of gene expression changes is uniform, and expression variations across different experimental groups are stable, with no anomalies or systematic bias, indicating high sample quality and good reproducibility.

The expression profiles of the 11 target genes are shown in Supplementary Fig. S11, where the color scale from red to blue represents high to low gene expression levels. Genes with FPKM > 1 were considered effectively expressed, whereas IL6 and SELE, with FPKM < 1, were regarded as not effectively expressed. The results showed that F3, ICAM1, IL1A, IL1B, SERPINE1, CCL2, THBD, and TNF exhibited markedly higher expression in the AGE group, but lower expression in the C1 and C2 and relatively low expression in the C3. In contrast, CXCL8 displayed low expression in the control group but higher expression in the C1, C2, and C3 groups.

Based on a screening threshold of p < 0.05, 11 genes involved in the AGE–RAGE signaling pathway were identified through network pharmacology analysis. As shown in Table 2, the AGE group exhibited significantly increased expression of IL1A, IL1B, CXCL8, and TNF compared to the control group. In the group treated with 100% quercetin, transcript levels of F3, ICAM1, IL1A, IL1B, SERPINE1, CCL2, and THBD were significantly downregulated, while CXCL8 was significantly upregulated. The group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid displayed a similar trend, with F3, ICAM1, IL1A, IL1B, SERPINE1, CCL2, and THBD significantly downregulated, and CXCL8 and SELE upregulated. In contrast, cells treated with 100% caffeic acid exhibited a different response, with significant upregulation of ICAM1, IL1A, IL1B, CXCL8, CCL2, THBD, and TNF. The expression patterns of the 11 genes were nearly identical between 100% quercetin treatment and a combination of 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, except for SERPINE1, which was expressed at lower levels in the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, while 100% caffeic acid treatment displayed greater variability and a distinct trend compared to the group treated with 100% quercetin and the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid.

Table 2. Differential expression trends of target genes in the AGE-RAGE pathway.

Gene ID Gene Name Control vs AGE AGE vs C1 AGE vs C2 AGE vs C3 C1 vs C2 C1 vs C3 C2 vs C3 ENSG00000117525 F3 Nodiff Downregulation Downregulation Nodiff Nodiff Upregulation Upregulation ENSG00000090339 ICAM1 Nodiff Downregulation Downregulation Upregulation Nodiff Upregulation Upregulation ENSG00000115008 IL1A Upregulation Downregulation Downregulation Upregulation Nodiff Upregulation Upregulation ENSG00000125538 IL1B Upregulation Downregulation Downregulation Upregulation Nodiff Upregulation Upregulation ENSG00000136244 IL6 − − Nodiff Nodiff Nodiff Nodiff Nodiff ENSG00000169429 CXCL8 Upregulation Upregulation Upregulation Upregulation Nodiff Downregulation Downregulation ENSG00000106366 SERPINE1 Nodiff Downregulation Downregulation Nodiff Downregulation Upregulation Upregulation ENSG00000108691 CCL2 Nodiff Downregulation Downregulation Upregulation Nodiff Upregulation Upregulation ENSG00000007908 SELE − Nodiff Upregulation Nodiff Nodiff Nodiff Downregulation ENSG00000178726 THBD Nodiff Downregulation Downregulation Upregulation Nodiff Upregulation Upregulation ENSG00000232810 TNF Upregulation Nodiff Nodiff Upregulation Nodiff Upregulation Upregulation Control is the untreated control group, AGE refers to the group treated with AGEs, C1 represents the group treated with 100% quercetin, C2 represents the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and C3 represents the group treated with 100% caffeic acid. Proteomic analysis

-

Proteomic analysis identified a total of 4,572 proteins across all samples. From these, 11 target proteins were selected for further investigation. As shown in Table 3, significant intergroup differences were observed in intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), interleukin 1 beta (IL1B), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8), and thrombomodulin (THBD), though their fold changes and significance levels varied across comparisons. Further pathway analysis revealed that ICAM1, IL1B, and CXCL8 are key components of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, both of which are critical in mediating inflammatory responses[45]. These pathways are activated during cellular stress, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, which contribute to chronic inflammation.

Table 3. Differential expression of target proteins in the AGE-RAGE pathway.

Protein Protein name Gene name AGE/

controlp

valueC1/AGE p

valueC2/AGE p

valueC3/AGE p

valueC2/C1 p

valueC3/C1 p

valueC3/C2 p

valueENSP00000264832 Intercellular adhesion

molecule 1ICAM1 1.07 0.3359 0.76 0.0036 0.84 0.0164 1.31 0.0024 1.11 0.0240 1.71 0.0001 1.54 0.0002 ENSP00000263341 Interleukin 1 beta IL1B 1.18 0.5024 0.34 0.0293 0.43 0.0493 1.46 0.0881 1.28 0.0987 4.28 0.0001 3.33 0.0002 ENSP00000385908 C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand 8CXCL8 1.25 0.4547 5.59 0.0007 6.24 0.0007 1.71 0.0735 1.11 0.3910 0.30 0.0013 0.27 0.0012 ENSP00000366307 Thrombomodulin THBD 0.83 0.0762 0.71 0.0041 0.73 0.0126 1.13 0.2486 1.02 0.7265 1.57 0.0105 1.53 0.0162 Control is the untreated control group, AGE refers to the group treated with AGEs, C1 represents the group treated with 100% quercetin, C2 represents the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and C3 represents the group treated with 100% caffeic acid. Compared to the control group, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, interleukin 1 beta, and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 were upregulated, while thrombomodulin was downregulated. This observation indicates that quercetin and caffeic acid may regulate the expression of these key proteins by altering the activation of the pathway and reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of quercetin and caffeic acid[46]. In contrast, treatment with 100% quercetin and 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid resulted in decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1, interleukin 1 beta, and thrombomodulin, while C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 expression was elevated relative to the AGE group. While all four proteins were upregulated in 100% caffeic acid treatment. The absence of significant differences in the remaining target proteins may be due to their lack of expression or low abundance in the analyzed cells.

Integrated analysis

-

Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data was conducted to identify the intersection of differentially expressed genes and proteins, as well as their expression trends. As shown in Table 4, IL1B and CXCL8 were consistently upregulated in both datasets when comparing the Control-AGE group, confirming a concordant inflammatory response at both the transcript and protein levels. In samples treated with 100% quercetin and 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, ICAM1, IL1B, and THBD were downregulated, while CXCL8 expression increased relative to the AGE group. These trends were aligned across both transcriptomic and proteomic analyses, suggesting coordinated regulation at the gene and protein levels. Similarly, in the AGE-100% caffeic acid comparison, ICAM1, IL1B, THBD, and CXCL8 were all upregulated, with matching expression patterns in both datasets. These findings indicated that 100% quercetin and 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid treatments suppressed inflammation by downregulating ICAM1, IL1B, and THBD, whereas the group treated with 100% caffeic acid primarily inhibited inflammation by suppressing the extracellular secretion of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-1β.

Table 4. Omics joint analysis of the differential expression of targets in the AGE-RAGE pathway.

Control vs AGE Transcriptomics Proteomics AGE/control p value IL1B Upregulation IL1B 1.18 0.502 CXCL8 Upregulation CXCL8 1.25 0.455 AGE vs C1 Transcriptomics Proteomics C1/AGE p value ICAM1 Downregulation ICAM1 0.76 0.004 IL1B Downregulation IL1B 0.34 0.029 CXCL8 Upregulation CXCL8 5.59 0.001 THBD Downregulation THBD 0.72 0.004 AGE vs C2 Transcriptomics Proteomics C2/AGE p value ICAM1 Downregulation ICAM1 0.85 0.016 IL1B Downregulation IL1B 0.44 0.049 CXCL8 Upregulation CXCL8 6.24 0.001 THBD Downregulation THBD 0.73 0.013 AGE vs C3 Transcriptomics Proteomics C3/AGE p value ICAM1 Upregulation ICAM1 1.31 0.002 IL1B Upregulation IL1B 1.46 0.088 CXCL8 Upregulation CXCL8 1.71 0.074 THBD Upregulation THBD 1.13 0.249 C1 vs C3 Transcriptome Proteomics C3/C1 p value ICAM1 Upregulation ICAM1 1.71 0.000 IL1B Upregulation IL1B 4.28 0.000 CXCL8 Downregulation CXCL8 0.30 0.001 THBD Upregulation THBD 1.57 0.011 C2 vsC3 Transcriptomics Proteomics C3/C2 p value ICAM1 Upregulation ICAM1 1.54 0.000 IL1B Upregulation IL1B 3.33 0.000 CXCL8 Downregulation CXCL8 0.27 0.001 THBD Upregulation THBD 1.53 0.016 Control is the untreated control group, AGE refers to the group treated with AGEs, C1 represents the group treated with 100% quercetin, C2 represents the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and C3 represents the group treated with 100% caffeic acid. Validation experiments

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction validation

-

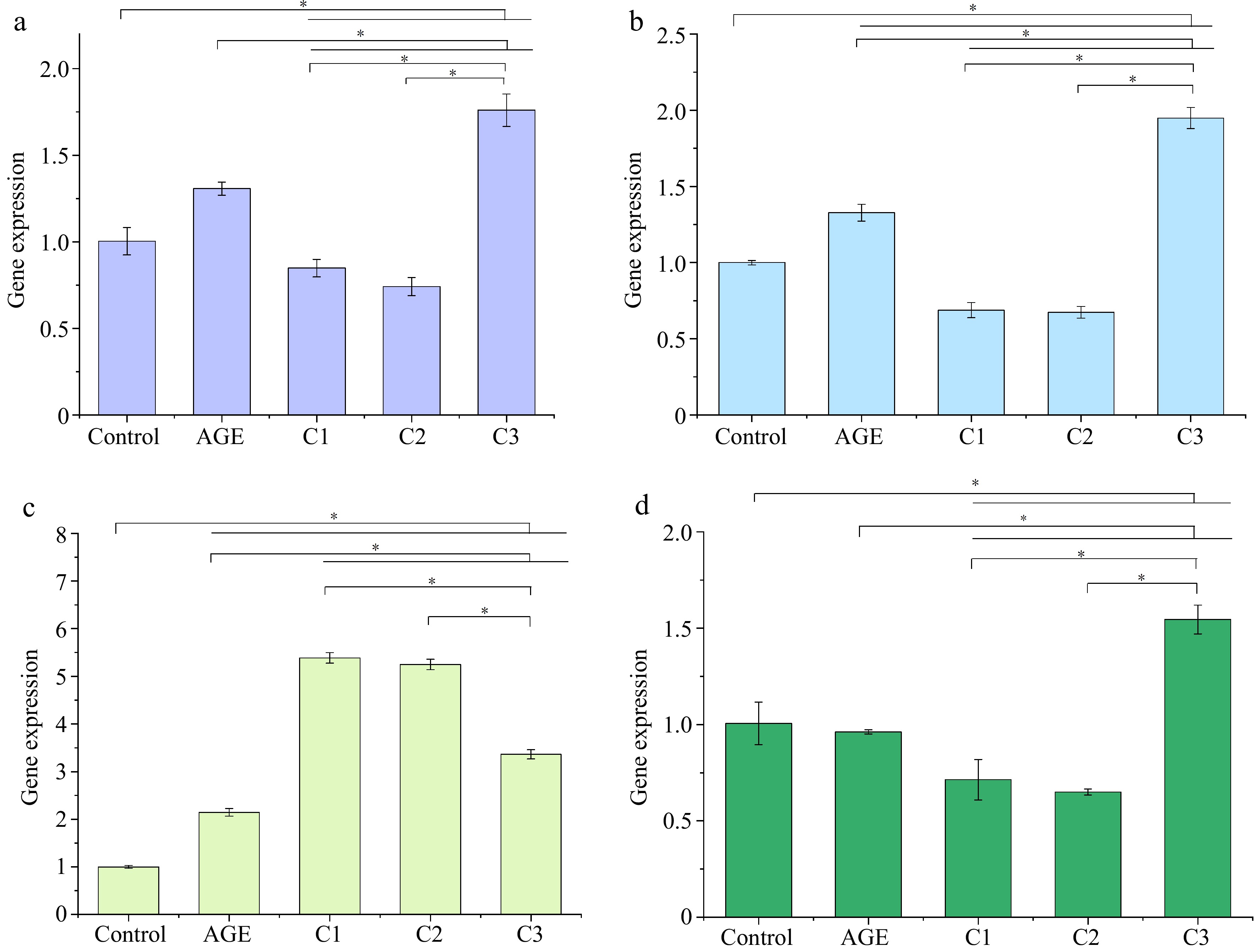

To validate the transcriptomic results, the relative expression levels of ICAM1, IL1B, CXCL8, and THBD were measured by qPCR, as shown in Fig. 2. In the AGE group, IL1B and CXCL8 expressions were significantly upregulated compared to the Control group. Although ICAM1 expression showed an upward trend, the difference was not statistically significant. THBD expression appeared reduced but similarly did not reach significance, suggesting that AGEs induce inflammation primarily through the upregulation of IL1B and CXCL8. In the groups treated with 100% quercetin and 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, the expression levels of ICAM1, IL1B, and THBD were reduced relative to the AGE group, whereas CXCL8 was further elevated. This pattern indicates that quercetin, either alone or in combination with caffeic acid, may alleviate AGE-induced inflammation by downregulating these key inflammatory genes. By contrast, treatment with 100% caffeic acid led to increased expression of ICAM1, IL1B, and THBD, while CXCL8 expression decreased, displaying a pattern more closely resembling that of the Control-AGE comparison. Overall, the qPCR results were consistent with the transcriptomic data, confirming the reliability of the experimental findings.

Figure 2.

Effects of different ratios of polyphenols on the gene expression of (a) ICAM1, (b) IL1B, (c) CXCL8, and (d) THBD. Gene expression was assessed by qPCR. * p < 0.05 indicates significant differences between groups. Control is the untreated control group, AGE refers to the group treated with AGEs, C1 represents the group treated with 100% quercetin, C2 represents the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and C3 represents the group treated with 100% caffeic acid.

Western blot validation

-

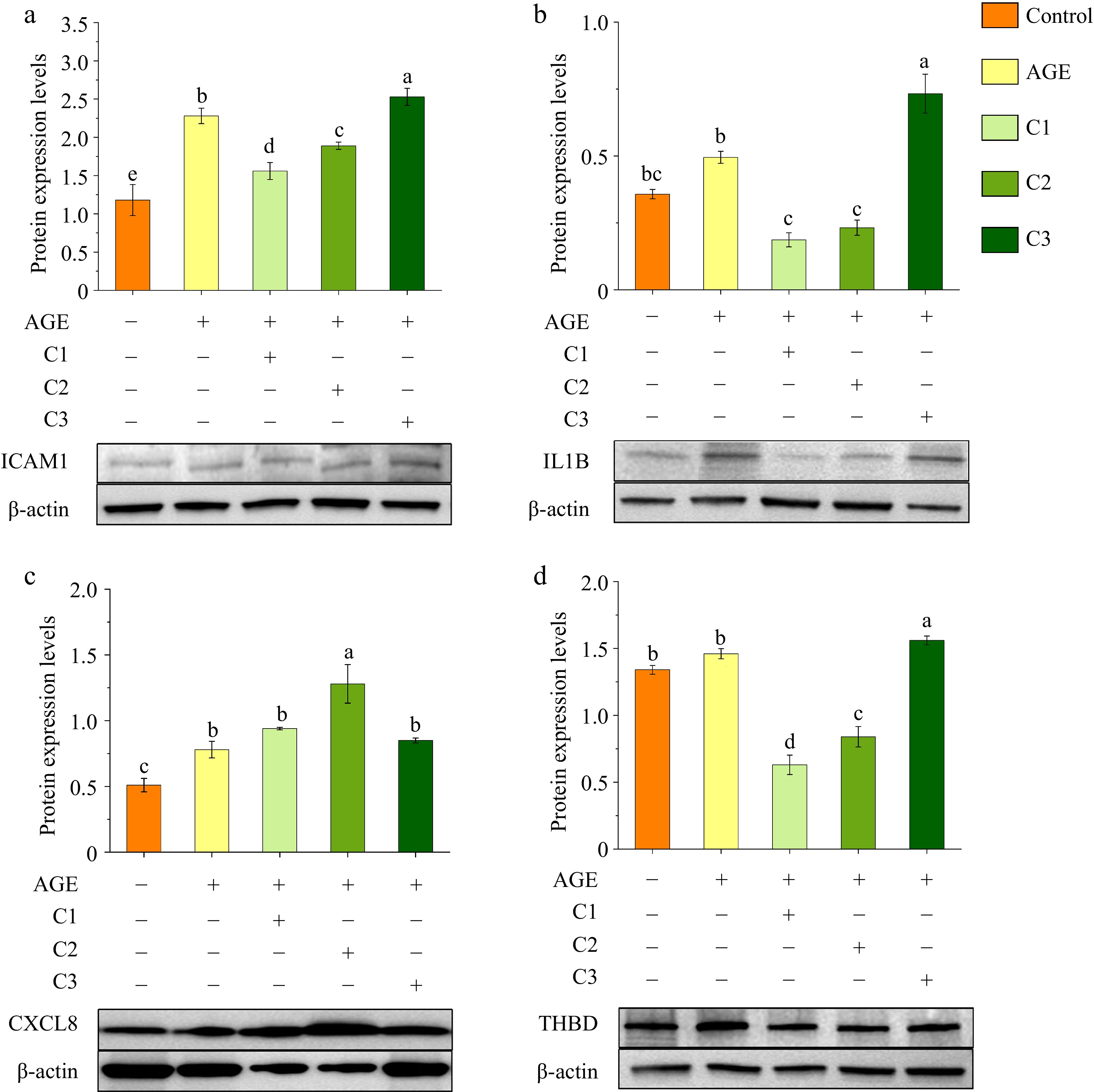

WB analysis was conducted to verify the proteomic findings by examining the effects of different polyphenol treatments on the expression of ICAM1, IL1B, CXCL8, and THBD in AGE-stimulated macrophages. As shown in Fig. 3, upon AGEs stimulation, the expression levels of ICAM1 increased from 1.18 to 2.28, IL1B from 0.35 to 0.49, and CXCL8 from 0.51 to 0.88. Although THBD expression showed a slight increase (from 1.34 to 1.46), the change was not statistically significant. Compared to the AGE group, treatment with 100% quercetin reduced the expression levels of ICAM1, IL1B, and THBD to 1.56, 0.18, and 0.63, respectively, while CXCL8 increased to 0.94. A similar pattern was observed in the 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid group, where ICAM1, IL1B, and THBD levels dropped to 1.89, 0.23, and 0.84, respectively, and CXCL8 rose to 1.28. In contrast, treatment with 100% caffeic acid resulted in elevated expression of ICAM1, IL1B, CXCL8, and THBD. The experimental results aligned with proteomic expression trends, confirming the reliability of the study.

Figure 3.

Effects of different ratios of polyphenols on the protein expression of (a) ICAM1, (b) IL1B, (c) CXCL8, and (d) THBD. Protein expression levels were analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin used as a loading control. Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). Control is the untreated control group, AGE refers to the group treated with AGEs, C1 represents the group treated with 100% quercetin, C2 represents the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and C3 represents the group treated with 100% caffeic acid.

These results were consistent with proteomic trends, supporting the reliability of the data. Furthermore, validation at both the transcriptional (qPCR) and translational (WB) levels confirmed the regulatory effects of 100% quercetin and 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid on ICAM1, IL1B, THBD, and CXCL8. The observed expression changes also aligned with previous findings from cytokine secretion assays, thereby enhancing the reliability of the results.

Compared to quercetin-containing treatments, 100% caffeic acid showed weaker regulatory effects on target protein expression. This suggests that caffeic acid may primarily act by modulating secreted inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, rather than directly altering intracellular protein expression linked to the AGE-RAGE pathway. Additionally, a potential synergistic effect between quercetin and caffeic acid was observed, as their combined application demonstrated superior anti-inflammatory efficacy compared to caffeic acid alone[47].

Proteomic and Western blot readouts primarily reflect intracellular protein abundance. In contrast, whereas IL-1β release requires a second inflammasome dependent activation. Therefore, caffeic acid alone may permit or mildly enhance priming but dampen activation, leading to lower extracellular IL-1β despite higher intracellular ICAM1/IL1B. Moreover, the effect of caffeic acid depends on both dose and ratio: higher proportions show pro-inflammatory signatures. At the working concentration, the overall effect is anti-inflammatory, especially when combined with quercetin

Binding interaction characteristics analysis

-

To further investigate whether quercetin and caffeic acid affect the binding of AGEs (pyrrole, CML, CEL) to RAGE, molecular docking was performed to evaluate binding sites and energies, assessing their potential for competitive inhibition. Each ligand (pyrrole, CML, CEL, quercetin, caffeic acid) was docked individually with RAGE to examine conformation, energy, and stability. As shown in Supplementary Table S7, pyrrole had the lowest binding energy with RAGE (−3.81 kcal/mol), indicating the strongest binding and highest stability, followed by CML and CEL, suggesting that pyrrole is most likely to bind RAGE and initiate signal transduction. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S12, all three AGEs bound RAGE through hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and salt bridges. Pyrrole acted as both a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor with ARG, formed hydrophobic interactions with LEU, and salt bridges with LYS. CML and CEL mainly acted as hydrogen bond acceptors, interacting with GLN, forming salt bridges with ARG, and hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with ILE, with CEL also acting as both donor and acceptor with ILE.

Caffeic acid showed strong binding to RAGE, with multiple conformations exhibiting binding energies below −4.0 kcal/mol. Quercetin also showed good binding, with ten conformations below −3.0 kcal/mol, seven of which were below −4.0 kcal/mol, indicating stable binding, and overall slightly weaker affinity than caffeic acid. Quercetin bound RAGE via hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, forming hydrogen bonds with ILE and LYS, hydrophobic interactions with GLN, and hydrogen bonds and other interactions with GLU. Caffeic acid interacted with RAGE through salt bridges, hydrophobic forces, and hydrogen bonds, acting as both donor and acceptor with CYS and ASN, and forming salt bridges and hydrophobic interactions with LYS.

In multi-ligand docking, three complexes consisting of pyrrole-caffeic acid-quercetin, CML-caffeic acid-quercetin, and CEL-caffeic acid-quercetin were docked with RAGE, and all three exhibited low binding energies, indicating strong binding capability. Structural interaction analysis (Supplementary Fig. S13) revealed that quercetin, caffeic acid, and AGEs did not simultaneously bind to the same site on RAGE, suggesting that they do not compete for the same binding site. This finding indicates that quercetin and caffeic acid do not inhibit AGE-RAGE signaling by directly competing for AGE binding sites on RAGE.

Semi-empirical calculations were performed to analyze the enthalpy changes before and after quercetin and caffeic acid binding to the target proteins, assessing their impact on the target Supplementary Table S8, the enthalpy difference (ΔH) before and after ligand binding ranged from 180.60 to 303.42 kcal/mol. In general, a larger ΔH reflects stronger binding interactions and a more pronounced effect on protein and receptor interactions, suggesting that quercetin and caffeic acid affected the binding of target proteins CCL2, CXCL8, F3, ICAM1, IL6, SELE, and TNF to their respective receptors and thereby interfered with inflammatory signal transduction. Among them, quercetin exhibited the strongest effect on the binding between SELE and its corresponding receptor. This was followed by its effect on CCL2 binding to its receptor. Caffeic acid showed a marked influence on the interaction between TNF and its receptor, while quercetin also affected the binding of IL6 to its receptor to a considerable degree.

-

In this study, network pharmacology and molecular docking identified eight bioactive compounds in dandelion species with anti-inflammatory potential, with quercetin and caffeic acid targeting 11 key proteins involved in the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway. Further analysis revealed that 100% quercetin and a combination of 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid exhibited the strongest inhibitory effects on TNF-α and IL-1β expression, suggesting enhanced anti-inflammatory effects when used in combination. Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis confirmed that quercetin and caffeic acid regulated the expression of ICAM1, IL1B, CXCL8, and THBD, modulating inflammatory signaling through the AGE-RAGE pathway. qPCR and WB validation confirmed that these gene and protein expression changes were consistent with omics data and cytokine secretion patterns, reinforcing the reliability of the findings. Molecular docking and computational analyses provided the binding interaction details showing that quercetin and caffeic acid bind RAGE without competing with AGEs and modulate target protein and receptor interactions, thereby interfering with AGE-RAGE inflammatory signaling. The results highlight the potential of quercetin and caffeic acid as promising bioactive ingredients for functional foods or nutraceuticals targeting AGE-RAGE-mediated, diet-induced inflammation, with their combination demonstrating enhanced anti-inflammatory efficacy.

This work was supported by the Innovation Project of Shandong Province Agricultural Application Technology (Grant No. 2130106), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2021QC049).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Data curation and writing − original draft: Gao L; Conceptualization and methodology: Gao L, Li G; Investigation: Li G; Validation: Liu T; Visualisation: Gao L, Li G, Liu T, Zou H, Chen Y; Writing − review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: Zou H, Chen Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Lu Gao, Guoqing Li

- Supplementary Table S1 Bioactive components of dandelion.

- Supplementary Table S2 Bioactive component-target-gene in dandelion.

- Supplementary Table S3 Inflammation-target gene information.

- Supplementary Table S4 GO functional enrichment analysis.

- Supplementary Table S5 Molecular docking results of quercetin, caffeic acid and target proteins.

- Supplementary Table S6 ANOVA Summary for TNF-α and IL-1β.

- Supplementary Table S7 Binding energy of AGEs, quercetin, and caffeic acid to RAGE.

- Supplementary Table S8 Standard system formation enthalpy difference before and after ligand binding.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Bioactive component-target network relationships in dandelion.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Inflammation-target network relationships.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Network diagram of dandelion intervention on inflammatory target protein interaction (PPI).

- Supplementary Fig. S4 GO enrichment analysis plot.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 KEGG enrichment analysis plot.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 AGE-RAGE signaling pathway.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Binding interaction analysis of quercetin, caffeic acid and target proteins.

- Supplementary Fig. S8 Effect of induction of PMA on the morphology of THP-1 cells.

- Supplementary Fig. S9 Effect of different concentrations of quercetin and caffeic acid on cell viability.

- Supplementary Fig. S10 Genome circle diagram. Control is the untreated control group, AGE refers to the group treated with AGEs, C1 represents the group treated with 100% quercetin, C2 represents the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and C3 represents the group treated with 100% caffeic acid.

- Supplementary Fig. S11 Cluster analysis of the expression of target genes in the AGE-RAGE pathway. Control is the untreated control group, AGE refers to the group treated with AGEs, C1 represents the group treated with 100% quercetin, C2 represents the group treated with 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid, and C3 represents the group treated with 100% caffeic acid.

- Supplementary Fig. S12 Analysis of the interaction between quercetin, caffeic acid, pyrrole, CML, CEL and RAGE.

- Supplementary Fig. S13 Analysis of the interaction between Pyrrole-caffeic acid-quercetin, CML-caffeic acid-quercetin, CEL-caffeic acid-quercetin and RAGE.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Gao L, Li G, Liu T, Zou H, Chen Y. 2026. Anti-inflammatory potential of dandelion polyphenols through modulation of AGE–RAGE signaling: key bioactive compounds and implications for functional foods. Food Innovation and Advances 5(1): 26−36 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0053

Anti-inflammatory potential of dandelion polyphenols through modulation of AGE–RAGE signaling: key bioactive compounds and implications for functional foods

- Received: 18 July 2025

- Revised: 08 December 2025

- Accepted: 19 December 2025

- Published online: 27 January 2026

Abstract: Dandelion, a widely used traditional medicinal and edible plant in China, is known for its anti-inflammatory properties, primarily attributed to polyphenols. Although the underlying mechanisms have yet to be fully clarified, in this study, a network pharmacology approach was combined with molecular docking to identify key bioactive polyphenols, followed by validation of their anti-inflammatory effects using cell-based assays, transcriptomics, proteomics profiling, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), Western blot, and computational analysis. A total of 29 protein targets were identified for dandelion-derived polyphenols, among which quercetin and caffeic acid were found to regulate 11 key proteins within the advanced glycation end products-receptor for advanced glycation end products (AGE-RAGE) signaling pathway, a central route linking dietary AGEs to chronic inflammation. Inflammatory cytokine assays showed that both 100% quercetin, and a combination of 50% quercetin + 50% caffeic acid exhibited the strongest inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) expression. This effect was primarily associated with the downregulation of ICAM1, IL1B, and THBD, while caffeic acid reduced IL-1β secretion. Calculation results revealed that both compounds strongly bound to receptors for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) without competing with advanced glycation end products (AGEs), disrupting protein and receptor interactions, and impeding inflammatory signal transduction. Overall, quercetin and caffeic acid effectively regulate AGE-RAGE-mediated inflammation, with their combination showing enhanced anti-inflammatory potential, and supporting the development of dandelion-based functional foods aimed at mitigating diet-induced inflammation.

-

Key words:

- Dandelion /

- Functional food /

- Polyphenols /

- Anti-inflammatory activity /

- Quercetin /

- Caffeic acid