-

The dictyostelids (also called cellular slime molds) are a group of eukaryotic microorganisms whose primary microhabitat is the soil/humus layer of forests, although they also occur in other types of terrestrial ecosystems such as grasslands[1,2]. Dictyostelids occur worldwide and are known from the Arctic and subantarctic to the tropics[3−5]. The most comprehensive treatments of their biology and ecology are those provided by Raper[6] and Liu et al.[7].

The dictyostelids belong to the Eumycetozoa, a taxonomic group in which the members have an amoeboid stage in their life cycle. About 200 species of dictyostelids have been formally described, but recent investigations in understudied areas and habitats indicate that there are numerous species as yet unknown to science[8−10]. For reproduction, dictyostelids produce fruiting bodies called sorocarps, and at the apex of each sorocarp, the spores occur in a thick, sticky, rounded mass known as a sorus (plural: sori)[11,12]. Dictyostelids exhibit motility during their amoeboid vegetative phase, though the actual distance they traverse in this state is extremely limited. Once these amoeboid cells aggregate to form a pseudoplasmodium, the latter can migrate over a greater distance in certain species; even so, this migration only reaches a maximum of a few centimeters, even when conditions are optimal.

-

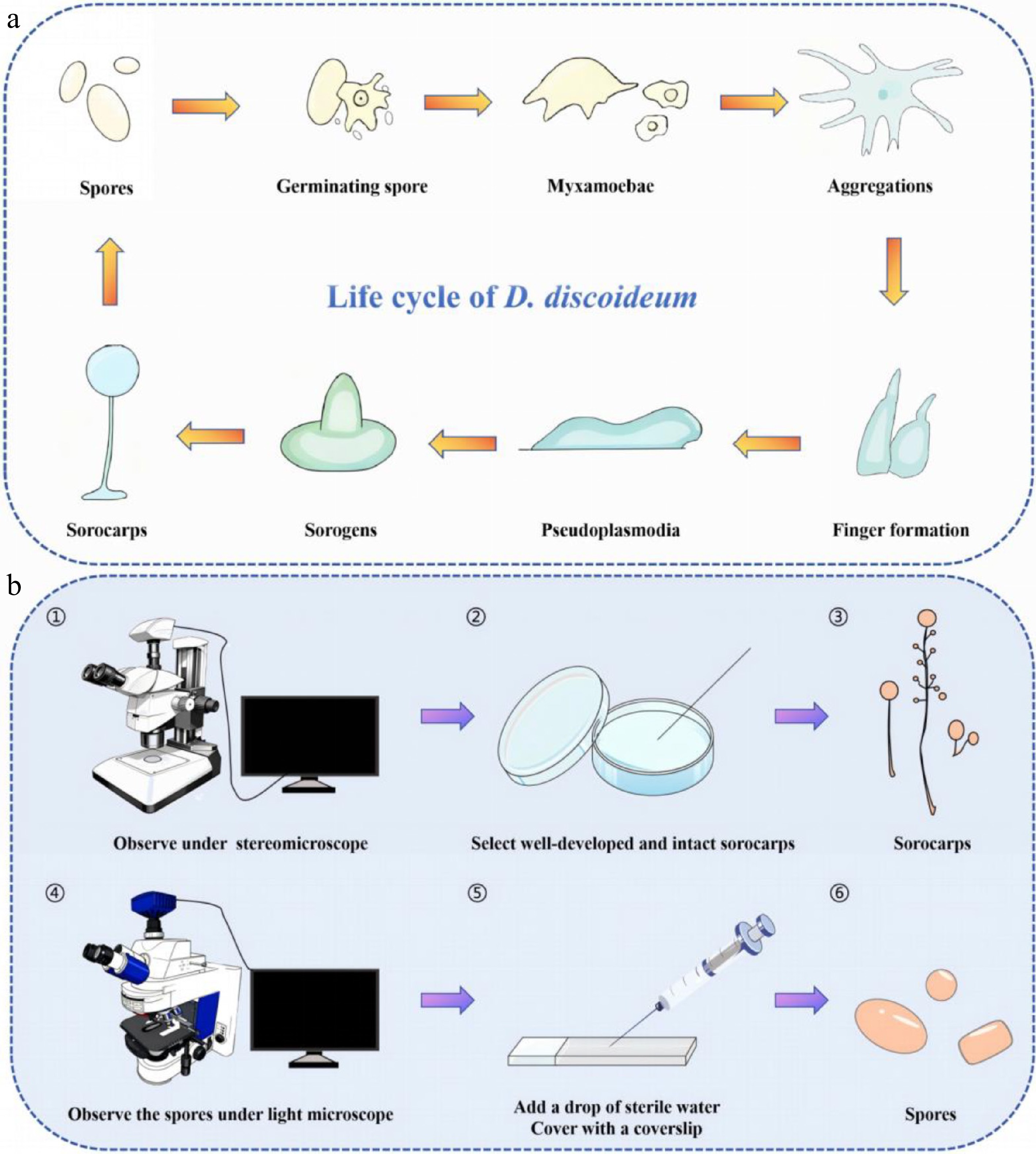

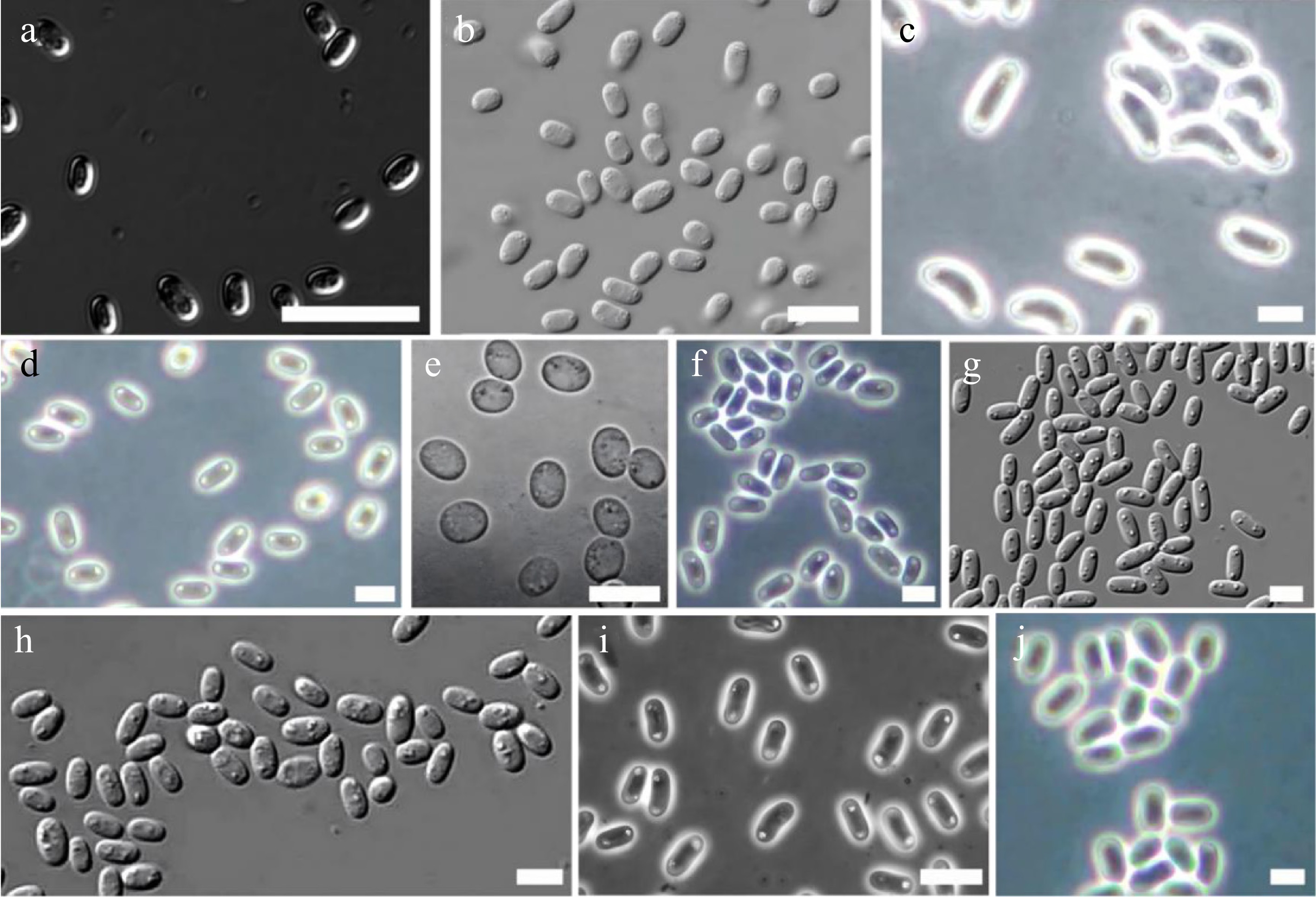

The morphological features of spores are an important criterion for the classification and identification of dictyostelids. Once spores reach maturity, they germinate when environmental conditions are favorable, giving rise to amoeboid cells referred to as either 'myxamoebae' or simply 'amoebae'[7] (Fig. 1a). When studying spores, well-developed and intact fruiting bodies (sorocarps) should be selected from a culture as viewed with a stereomicroscope. These should be placed on a glass slide, a drop of sterile water added, covered with a coverslip, and the slide sealed. The spores can then be observed using a light microscope equipped with a 10× eyepiece and a 100× oil immersion objective, and the features of the spores determined. These include spore shape and size, spore length-width ratio, and the presence or absence of polar or other granules (Fig. 1b). After capturing images with a color camera on the microscope, these images can be uploaded to a specimen identification archive database. Aspects of spores to be considered in a full description are color, shape, polar granules, inclusion vacuoles, vesicles, substances, stickiness, cell wall, and spore germination rate.

Figure 1.

(a) The amoebae of D. discoideum persist across the organism's complete life cycle. (b) The steps involved for observing spores.

Spore color

-

The spores of most dictyostelids are hyaline and colorless, but some species produce spores with some color. For example, the spores of Dictyostelium annularibasimum are sometimes colorless or pale purple[13], those of D. dichotomum are yellow[14], and the spores of Polysphondylium acuminatum range from hyaline to vinaceous[15]. The smaller spores (2−4 µm) of Acytostelium aggregatum are opaque[16]. Spore color tends to fade over time. This is especially true for those with a yellow tint.

Spore shape

-

Spores of species of dictyostelids exhibit significant morphological diversity, with variations in shape, size, and specific morphological features among different genus and species. The characteristics can be summarized from four dimensions: common morphology, special morphology (Fig. 3), size variation, and length-breadth (L/B) ratio, as outlined in the sections that follow.

Common morphology

-

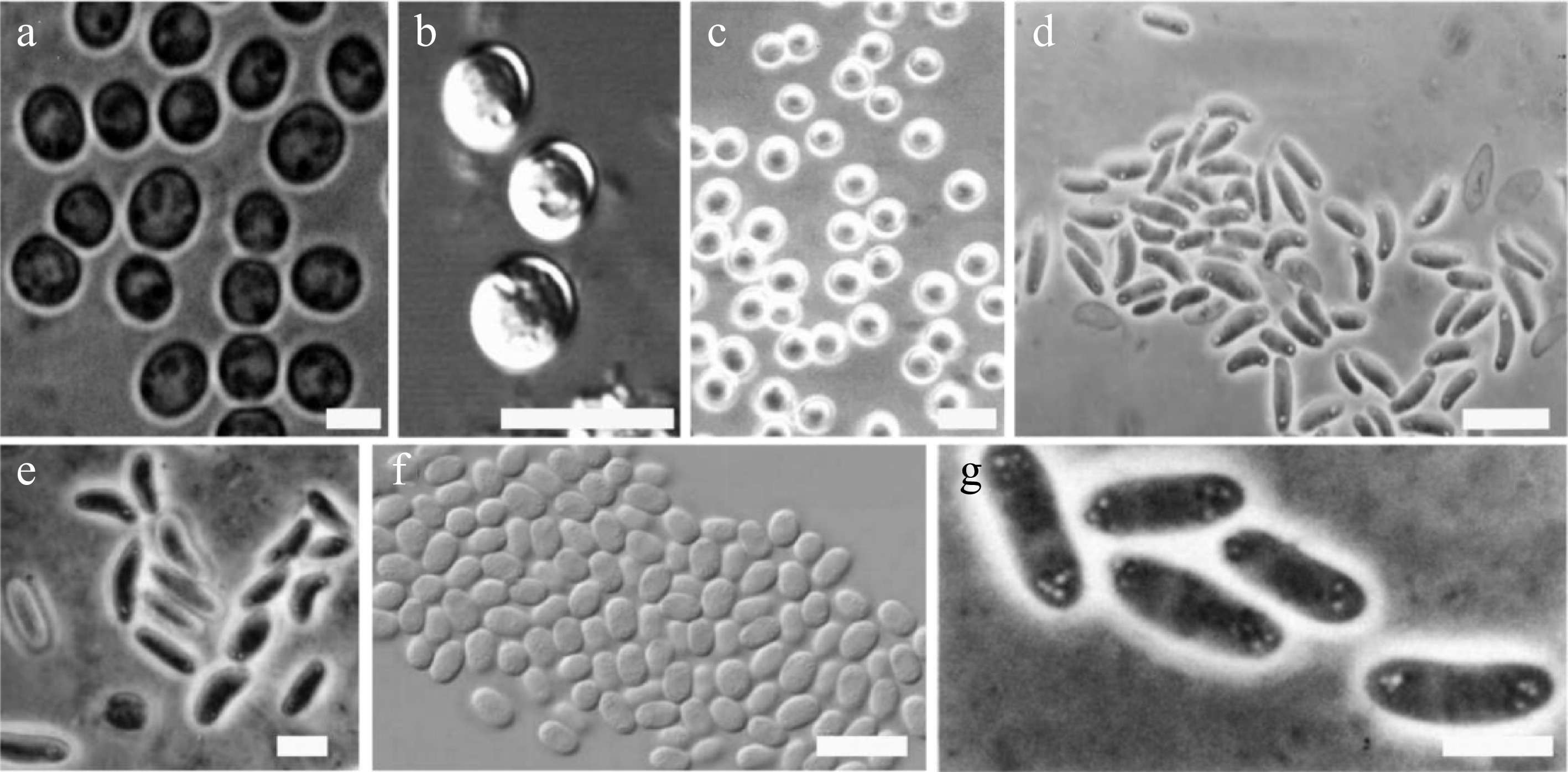

The predominant spore morphologies in dictyostelids are elliptical or oblong. Only a few species produce spherical spores, including Dictyostelium rosarium, D. globisporum, D. minimum, Heterostelium equisetoides, and Tieghemostelium lacteum[17−21]. In addition, spores of most species in the genus Acytostelium are mainly globose to subglobose (Fig. 2a–c).

Figure 2.

Examples of different dictyostelid spore shapes (drawn from the corresponding references). (a) Dictyostelium globisporum spores. Bar = 5 μm[18]. (b) D. minimum spores. Bar = 10 µm[19]. (c) Heterostelium equisetoides. Bar = 10 μm[20]. (d) Cavenderia boomerangispora, long and frequently curved PG+. Bar = 10 μm[23]. (e) H. naviculare, elongated navicular spores with consolidated polar granules. Bar = 5 μm[27]. (f) H. flexuosum, relatively small spores, note the widely distributed, numerous unconsolidated granules. Bar = 10 μm[23]. (g) D. polycarpum, group of spores with polar spore granules PG. Bar = 5 μm[30].

Special morphology

-

Spores of some species possess highly distinctive special morphologies. Some species of dictyostelids exhibit spore deformation. Deformed spores are usually larger than normal ones and mostly appear reniform or sigmoid. This characteristic was documented in early studies and represents an important aspect of morphological variation in dictyostelid spores[6,22]. For example, spores of Cavenderia boomerangispora are long, elliptical, and often curved into a boomerang shape (Fig. 2d), a feature that is particularly prominent in older cultures[23]. Spores of species such as Heterostelium pallidum and Raperostelium tenue can be reniform (kidney-shaped)[24,25]. Spores of Dictyostelium dimigraforme and Polysphondylium laterosorum may also exhibit sigmoid (S-shaped) or recurved forms[26].

Other special morphologies

-

Spores of Heterostelium naviculare are elliptical to navicular, with some individuals being sharply pointed or reniform (Fig. 2e)[27]; spores of Hagiwaraea coeruleostipes and H. lavandula have a capsule shape, with only occasional slightly reniform spores observed in larger examples; spores of H. rhizopodium are narrowly elongated[28]; and spores of Coremiostelium polycephalum are elliptical or reniform[29].

Size variation

-

In terms of size, spores of most species are relatively stable. For example, spores of Heterostelium flexuosum are very small and broad, mostly measuring 4.5 × 3 μm (Fig. 2f)[23]; spores of H. pallidum are oval, ranging from 2.5−3 μm × 5−6.5 μm, with spherical individuals having a diameter of approximately 7−8 μm[24]. However, a few species show extreme size variation. For example, in Dictyostelium dimigraforme, the spores exhibit extremely wide size variation, mostly measuring 7.0−12.0 × 2.5 μm, with some reaching up to 26 × 5 μm; Polysphondylium laterosorum also displays a wide size variation, ranging from 6.0−13.0 × 2.5−4.0 μm[26]. Acytostelium aggregatum produces two sizes of spores. Most spores measure 5−8.5 μm (average 5.76 μm), while smaller spores are 2−4 μm. The smaller spores have a more regular shape, are opaque, and some are oblong (7 × 5 μm)[16]. The spores of Raperostelium tenue fall into two distinct size ranges, with smaller spores averaging 3.0 × 6.0 μm and larger spores averaging 4.5 × 8.5 μm[25].

Hagiwara conducted studies on the effect of temperature on spore size, which showed that the spores of some species of dictyostelids (e.g., Dictyostelium firmibasis, Cavenderia delicata, Raperostelium minutum, Heterostelium pseudocandidum, and Polysphondylium violaceum) increased in size to a certain extent at lower temperatures (5 or 10 °C)[22]. Liu et al. found that in environments above 2,000 m elevation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China, the spore length of dictyostelids and the ratio of sori to spores were positively correlated with increasing elevation. However, there was little difference in spore size at 15, 20, or 25 °C. Nevertheless, available data on dictyostelids suggest that they should be cultured under the temperature conditions of 15 to 25 °C[19].

Length-breadth (L/B) ratio

-

Slender spores in some species. The L/B index of Dictyostelium polycarpum spores is 2.9, showing a distinct slender feature (Fig. 2g)[30]. In D. flavidum, the spores are hyaline and long elliptical, with an L/B index of approximately 2.4−2.8[31]. The spores of Raperostelium filiforme are 1.8−2.3 times longer than they are broad, presenting a slender shape[32].

Spore polar granules (including vacuoles, vesicles, and substances)

-

Spores of some species of dictyostelids contain plasmids, commonly called 'polar granules'. These are usually located at both ends or the center of the spores in which they are present. Species of dictyostelids with polar granules do not show a chemotactic response to the aggregating factor cAMP, whereas species without polar granules do respond to cAMP (which serves as their aggregating factor). Polar granules are important in the identification of dictyostelids, and their presence or absence can be easily determined under a light microscope[22].

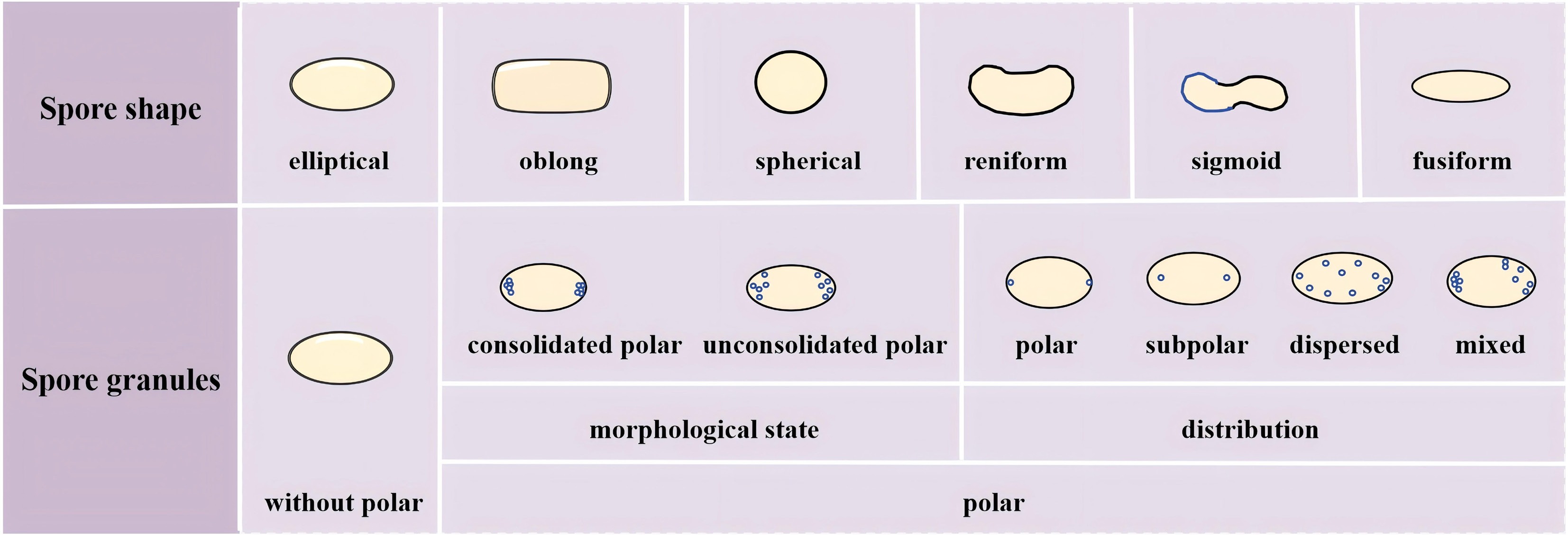

To comprehensively understand the taxonomic significance of polar granules in various species of dictyostelids, their characteristics across multiple dimensions including morphological state (consolidated vs unconsolidated), distribution (polar, subpolar, dispersed, mixed), visibility (conspicuous vs inconspicuous), and special structures (e.g., halos, refractive features) need to be considered (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Microscopic features (shape and granules) of spores used in the identification of dictyostelid species.

More than half of all species of dictyostelids lack polar granules. Species with conspicuous polar granule includes Dictyostelium polycarpum, D. recurvibasicum, D. robusticaule (Fig. 4a), D. globisporum, Raperostelium gracile, Heterostelium stolonicoideum (Fig. 4b), Cavenderia aureostipes, and C. exigua[23,25,30,33−35]. Other species containing polar particles have been summarized in Table 1. The latest classification system of dictyostelids is shown in Fig. 5[36].

Figure 4.

Examples of different dictyostelid spore granules (drawn from the corresponding references). (a) Dictyostelium robusticaule. Bar = 20 μm[34]. (b) Heterostelium stolonicoideum, oblong spores note the conspicuous unconsolidated polar granules. Bar = 10 μm[23]. (c) Raperostelium cymosum, large elliptical, mostly reniform spores with conspicuous consolidated polar to subpolar granules. Bar = 6 μm[37]. (d) Cavenderia fulva, elliptical spores with prominent refractive consolidated granules at their poles. Bar = 5 μm[37]. (e) R. ibericum. Bar = 10 μm[38]. (f) C. minima, small elliptical irregular spores with polar to subpolar consolidated granules, generally the cluster of granules appears larger at one of the poles. Bar = 6 μm[37]. (g) D. capillare, elliptical spores with conspicuous, consolidated polar granules. Bar = 5 μm[32]. (h) C. bhumiboliana, rather large, elliptical spores with consolidated polar granules. Bar = 10 μm[39]. (i) Hagiwaraea irregularibrachiatum, elliptical short spores with small unconsolidated polar to subpolar granules. Bar = 6 μm[37].

Table 1. Species of dictyostelids containing polar particles along with their sources and original literature descriptions.

Species Morphological state (consolidated vs unconsolidated) Distribution

(polar, subpolar,

dispersed)Visibility (conspicuous vs inconspicuous) Special structures

(e.g., halos, refractive features)Others Ref. Dictyostelium ammophilum ! ++ (Occasionally +) Romeralo et al.[40] D. capitatum + – Hagiwaia[41] D. dichotomum Mostly + ++ to + + Vadell & Cavender[14] D. gargantuum – On the surface Vadell et al.[42] D. germanicum Mostly – + On the surface Cavender et al.[43] Polysphondylium violaceum + + Vadell and Cavender[15] P. aureum + + + Hodgson & Wheller[44] P. fuscans – + Perrigo[45] P. patagonicum + Mostly + + Vinaceous Vadell et al.[42] Raperostelium ibericum Mostly +, some – – + One or more relatively

large granulesRomeralo et al.[38] R. australe Polar to subpolar/

dispersed+ Cavender et al.[46] R. cymosum + ++ to + + Cavender et al.[37] R. maeandriforme + ! + Some with a heterogeneous content Cavender et al.[32] Acytostelium anastomosans Central + Cavender et al.[27] *A. subglobosum Distinctively different

from other species due to inconsistently scarce,

minute granulation and clearly recognizable zonationCavender & Vadell[16] Heterostelium anisocaule – + Cavender et al.[46] H. luridum – Mostly throughout

the cytoplasmKauffman et al.[47] H. migratissimum Median + ++ and + + Cavender et al.[8] H. parvimigratum Mostly + Not consistently ++ or +, – Cavender et al.[8] H. radiatum ++ – Perrigo et al.[48] H. rotatum Mostly – – (the largest at

the poles)Landolt et al.[23] H. stolonicoideum Mostly – ++ Landolt et al.[23] H. tikalense – ++ Vadell & Cavender[15] Cavenderia ungulata + ++ + Often surrounded by

a clear narrow haloLarge Cavender et al.[49] C. pseudoaureostipes + Mostly ++, sometimes +

or with – smaller granulesSurrounded by clear halos Many rounded Vadell et al. [39] C. antarctica + ++ to + + Sometimes unipolar, smallest individuals lack granules Cavender et al.[46] C. nanopodia + + Irregular in shape and size Vadell & Cavender[14] C. fasciculata ++ or + + Traub et al.[30] C. fasciculoidea + ++ + Surrounded by a clear halo Visible as angular units Vadell et al.[42] C. fulva 1–2 large + ++ to +,

sometimes –Cavender et al.[37] C. macrocarpa + ++ to + Vadell & Cavender[14] *C. minima Heterogeneous content (often one much larger cluster of granules at one pole with halos, plus tiny dispersed granules) Cavender et al.[37] *C. subdiscoidea + ++ Dense, round, with clear halos Duringdormancy—spores enlarge when in contact with humid substrate, making the spore body heterogeneous and granules larger Vadell et al.[39] C. helicoidea – ++ Cavender et al.[49] Special cases are indicated by an asterisk '*', consolidated '+', unconsolidated '−'; polar '++', subpolar '+', dispersed '−'; conspicuous '+', inconspicuous '−'; concurrence '!'.

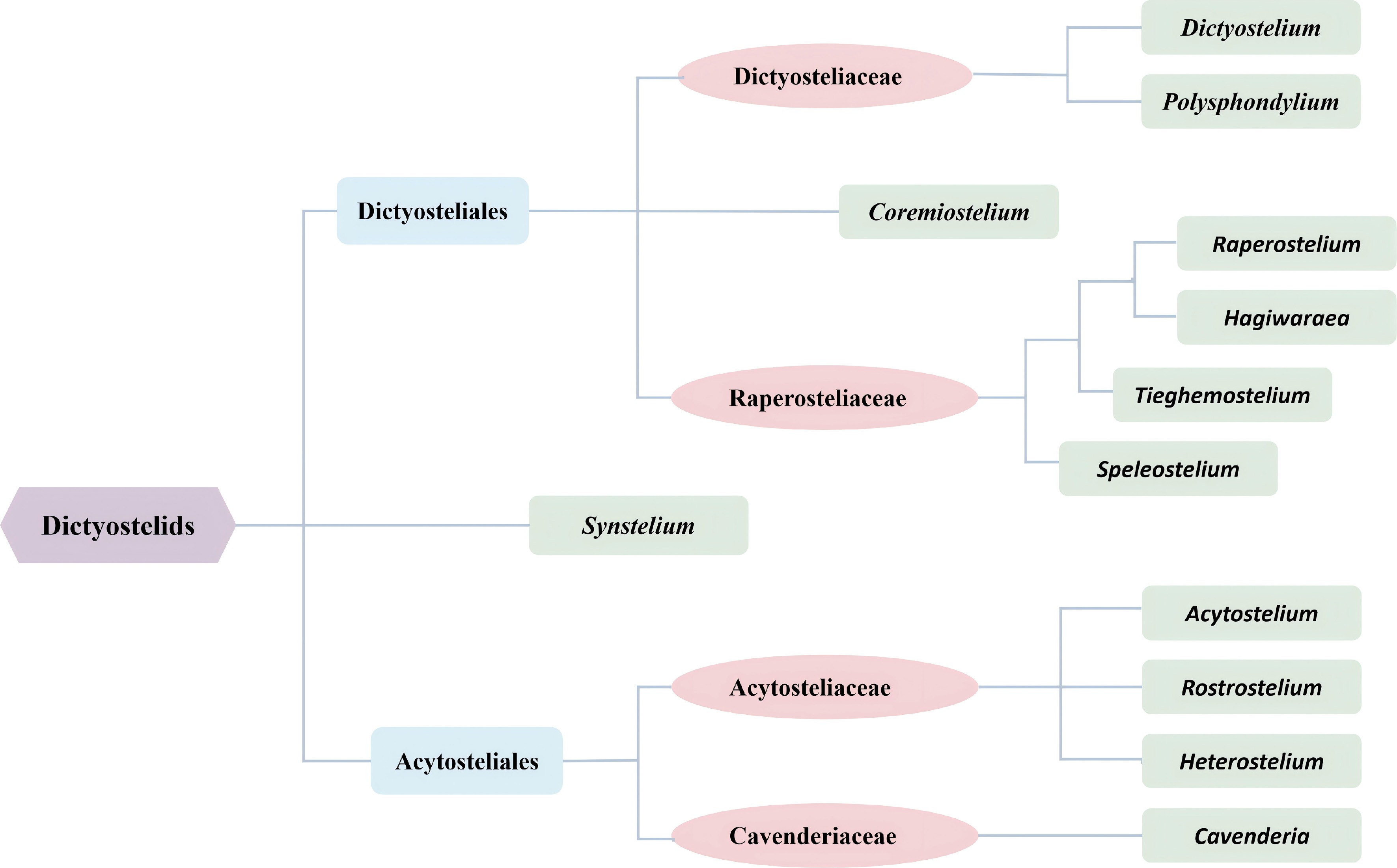

Figure 5.

The current classification used for dictyostelids[36] (drawn from Sheikh et al. 2018).

Morphological state and distribution: consolidated polar granules

-

Consolidated polar granules, as a dominant morphological type, exhibit distinct patterns in both visibility and spatial distribution across species. A large number of species, such as Dictyostelium dichotomum, Polysphondylium violaceum, P. aureum, P. patagonicum, Raperostelium australe, R. cymosum (Fig. 4c), R. maeandriforme (in part), and multiple members of the genus Cavenderia (e.g., C. ungulata, C. pseudoareostipes, C. antarctica, C. fasciculoidea, C. fulva (Fig. 4d), C. macrocarpa, and C. subdiscoidea during dormancy), possess these granules in a consolidated state. They are conspicuous and predominantly localized in polar or subpolar regions, serving as a key diagnostic feature. Moreover, some species within this group display additional structural modifications. For example, C. ungulata, C. pseudoareostipes, and C. subdiscoidea are noted for clear halos surrounding their granules, while C. fasciculoidea features angular, visually distinct granular units.

Notably, a subset of species with consolidated granules deviates from the 'polar/subpolar concentration' pattern. For example, Heterostelium luridum disperses consolidated granules throughout the cytoplasm, Raperostelium ibericum distributes them across the entire spore body (not limited to poles) (Fig. 4e). Cavenderia minima presents a heterogeneous profile, with a large cluster of consolidated granules (with halos) at one pole alongside tiny dispersed granules, further highlighting the diversity within this morphological category (Fig. 4f).

Morphological state and distribution: unconsolidated polar granules

-

Unconsolidated polar granules, by contrast, are characterized by their dispersed or less-organized structure. Dictyostelium germanicum has numerous unconsolidated granules on the surface. Polysphondylium fuscans, Heterostelium stolonicoideum, and H. tikalense (with 'polar-like' unconsolidated granules) exhibit this state in the polar/subpolar regions. Heterostelium rotatum extends this dispersion across the entire spore body, with the largest granules concentrated at the poles.

In some cases, unconsolidated granules coexist with consolidated ones. Raperostelium ibericum is a representative example, encompassing both morphological types. Moreover, Acytostelium subglobosum stands out due to its scarce, minute, unconsolidated granules and recognizable zonation, distinguishing it markedly from other taxa.

Visibility and special structural variations

-

The visibility of polar granules further differentiates species. Dictyostelium dichotomum, Polysphondylium patagonicum, Raperostelium australe, and Cavenderia ungulata possess conspicuous granules that are easily identifiable in morphological or distributional aspects. Conversely, Dictyostelium capitatum and Heterostelium radicum have inconspicuous granules, making their identification more challenging.

Beyond these general patterns, several species exhibit unique structural features. Cavenderia helicoidea has irregularly shaped consolidated granules, Acytostelium anastomosan features prominent central granules, Heterostelium anisoctale displays highly refractile unconsolidated granules, and H. parvimigratum has tiny granules that are not consistently restricted to polar or subpolar regions.

Taxonomic implications

-

The combination of polar granule characteristics—including consolidation state, distribution, visibility, and special structures—serves as a critical set of markers for species differentiation and taxonomic research. These morphological and spatial variations not only reflect the evolutionary divergence of dictyostelids but also provide tangible criteria for their identification and classification. Some species of dictyostelids have vacuoles, vesicles, or specific contents other than polar granules in their spores. Other species have vacuoles, vesicles, or specific contents. Dictyostelium leptosomopsis has tiny vacuoles[42]; D. quercibrachium often has large scattered vesicles[46] D. brevicaule has vesicles[14]; Heterostelium equisetoides has small refractile vesicles[20]; and H. unguliferum has small vacuoles[8].

Spores of these species contain polar granules and inclusions such as vacuoles, which can be classified by genus as follows: Dictyostelium valdivianum spores have small to medium vacuoles and small to medium granules (spaced within the spore body, mostly at the poles), and D. chordatum has some dispersed granules and many vacuole-like inclusions[42]. Raperostelium capillare has heterogeneous contents, including consolidated polar or subpolar granules (often with one visible granule, not always at the poles), small dispersed granules, and vacuoles; smaller spores sometimes lack granules (Fig. 4g)[32]. Raperostelium crispum has variable unconsolidated polar/subpolar granules in addition to tiny dispersed granules, vacuoles, and heterogeneous contents[37]. R. filiforme is characterized by distinct, consolidated polar (or occasionally subpolar) granules — often a single polar granule encircled by a clear halo — and hyaline contents with heterogeneous properties. Tieghemostelium dumosum has consolidated polar granules (along with subpolar or dispersed granules) and small vacuoles with heterogeneous contents, while T. unicornutum has vacuoles with heterogeneous contents and crowded consolidated granules (not consistently polar)[32]. Spores of Cavenderia protodigitata are hyaline to vacuolated or have variable heterogeneous contents, with two unequal medium-to-large consolidated regular polar granules (one with an evident halo) and other smaller dispersed granules[39]; The spores of C. basinodulosa have prominent consolidated polar granules (PG+) (not consistently polar but sometimes dispersed near the poles) and many small vacuoles while those of C. bhumiboliana have polar to subpolar granules (sometimes dispersed, irregular in size and shape; often surrounded by a clear halo), plus other small dispersed granules, vacuoles, and heterogeneous content (Fig. 4h)[39,48]. Spores produced by Acytostelium aggregatum have granules, nuclear vacuoles, and vesicles within the spore (surrounded by a dense slime matrix)[16]. Spores of Heterostelium lapidosum have minute polar to subpolar granules, small vacuoles, and some individuals have more evident consolidated polar to subpolar granules[8]. H. irregularibrachiatum has unconsolidated polar/subpolar small granules and tiny dispersed vacuoles (Fig. 4i)[37]; and H. perasymmetricum has consolidated large and small polar to subpolar granules (sometimes dispersed) and small vacuoles[8].

Spore stickiness

-

The stickiness of dictyostelid spores varies considerably among species. Those of Acytostelium aggregatum are surrounded by a dense slime matrix, while the spores of Heterostelium versatile are strongly adherent[16,48]. In Cavenderia amphispora, the spores generally stick to one another[27]; they are sticky within the sorus of C. bhumiboliana[39], and this is also the case for C. parvibrachiata as well as C. ungulata[49]. In some species of dictyostelids, the stickiness is less apparent.

Spore cell wall

-

All dictyostelids produce spores with smooth cell walls containing cellulose. The spores of Dictyostelium rosarium have a finely granular surface and comparatively thin walls[17]. In contrast, Acytostelium irregularosporum has thin cell walls compared to other species[16]. However, the cell wall is always prominent enough to be readily apparent.

Spore germination rate

-

The germination rate of spores also varies among species. A number of species have spores that germinate immediately. Examples include Dictyostelium austroandinum, Polysphondylium patagonicum, Cavenderia protodigitata, C. pseudoaureostipes, C. subdiscoidea, C. basinodulosa, C. helicoidea, C. nanopodia, Tieghemostelium simplex, Heterostelium cumulocystum, H. irregularibrachiatum, H. lapidosum, H. parvimigratum, H. plurimicrocystogenum, H. pseudocolligatum, H. pseudoplasmodiofascium, H. pseudoplasmodiomagnum, H. radiatum, and H. unguliferum[8,14,32,37,39,42,48,49].

More specifically, the spores of Cavenderia amphispora germinate immediately when the sorocarp collapses, while those of C. stellata show immediate germination upon the collapse of the sorus[27]. For C. bhumiboliana, most spores germinate immediately, although some do not[39]. In C. canoespora and C. subdiscoidea, most spores germinate immediately[39,48]. In contrast, the spores of Heterostelium perasymmetricum germinate after a short period of dormancy, but the spores of Acytostelium leptosomum do not germinate immediately after the sorus collapses on the substratum, and the spores of H. racemiferum and H. violaceotypum also fail to germinate immediately[8,16].

Spore adhesion and resistance

Size (likelihood of being preyed upon)

-

The size and shape of spores may affect their biological adaptability, especially in their ability to resist predation pressure. Small spores usually have stronger resistance to digestion. Due to their smaller size, certain predators (such as protozoa or nematodes) may have more difficulty in effectively ingesting these spores, thereby increasing the survival rate of the spores. The size of spores significantly affects their distribution and predation under spore size screening conditions, indicating that spores of specific sizes can limit predation through their physical characteristics[50]. Compared to smaller spores, large spores often exhibit stronger adhesion ability on surfaces with natural adhesive properties (such as host plants or moist soil), thereby gaining a survival advantage in specific environments[51,52]. Studies have found that although the size of spores significantly improves their ability to resist external physical stimuli, the cost is that the predation risk may increase due to their larger size. However, this trade-off is still considered an important selection pressure for population evolution and ecological adaptation[50].

Cell wall thickness (anti-digestibility)

-

The spore cell wall of dictyostelids plays a crucial protective role throughout its life cycle, and its thickness and structure are closely related to the spore's resistance to digestion. The spore cell wall is composed of multiple layers, including a cellulose core, an inner layer consisting of closely bound polysaccharides, and an outer protein layer. This multi-layered composite structure provides mechanical strength and forms a barrier that allows gas exchange but prevents digestive enzymes from reaching the living protoplast. The spore cell wall of dictyostelids are rich in glycoproteins such as SP96 and SP85, which form a further protective membrane through glycosylation and can effectively resist degradation by extracellular enzymes such as cellulase and chitinase. Cellulose is the main structural component of the spore's cell wall, and the arrangement of its fibers gives the spore resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis[51,53,54]. Studies have shown that spores with thicker cell walls have a higher survival rate after treatment with digestive fluids such as pepsin. This indicates a significant positive correlation between cell wall thickness and spore resistance[51].

Adhesive matrix (adhesion mechanism)

-

The adhesion and attachment properties of their spores play a crucial role in the multicellular growth and differentiation of dictyostelids. The spore cell wall of dictyostelids exhibits significant adhesion characteristics, mainly composed of SP70 and other glycoproteins, as well as a cellulose matrix. These substances enhance the anti-detachment ability of spores through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding. Adhesion proteins, such as gp24 and gp80, are expressed on the spore cell membrane surface, mediating surface attachment of spores in the environment and mutual aggregation among spores[55−57]. Dictyostelium discoideum can induce cell movement towards specific targets through cAMP signaling and form intercellular junctions by binding adhesion molecules such as DdCAD-1. This mechanism may affect the efficiency of spore attachment to the substrate and is a key step in maintaining the structure of the fruiting body[56,58]. During spore formation, the adhesion properties of the outer wall may enhance its stability, helping mature spores adhere to the surrounding substrate and reducing mechanical detachment caused by water flow or wind[52].

-

Like many other microorganisms, such as fungi and myxomycetes, dictyostelids reproduce by means of spores. Unlike most other microbial taxa, dictyostelid spores possess relatively constrained dispersal potential. Within the sorus of a sorocarp, these spores are embedded in a mucilaginous matrix that undergoes desiccation and subsequent hardening. This physical trait severely limits the likelihood of wind-mediated dispersal for the spores, a finding supported by Cavender's research[59]. While water-based dispersal of dictyostelids is theoretically feasible, such an event is thought to occur only under exceptional environmental conditions, such as intense flooding. Given these constraints on common dispersal pathways, a key question emerges: through what specific mechanisms do dictyostelid spores accomplish successful dispersal in their natural habitats? Available data suggest that it takes place through the activities of other organisms that serve as vectors of dispersal.

Invertebrates

-

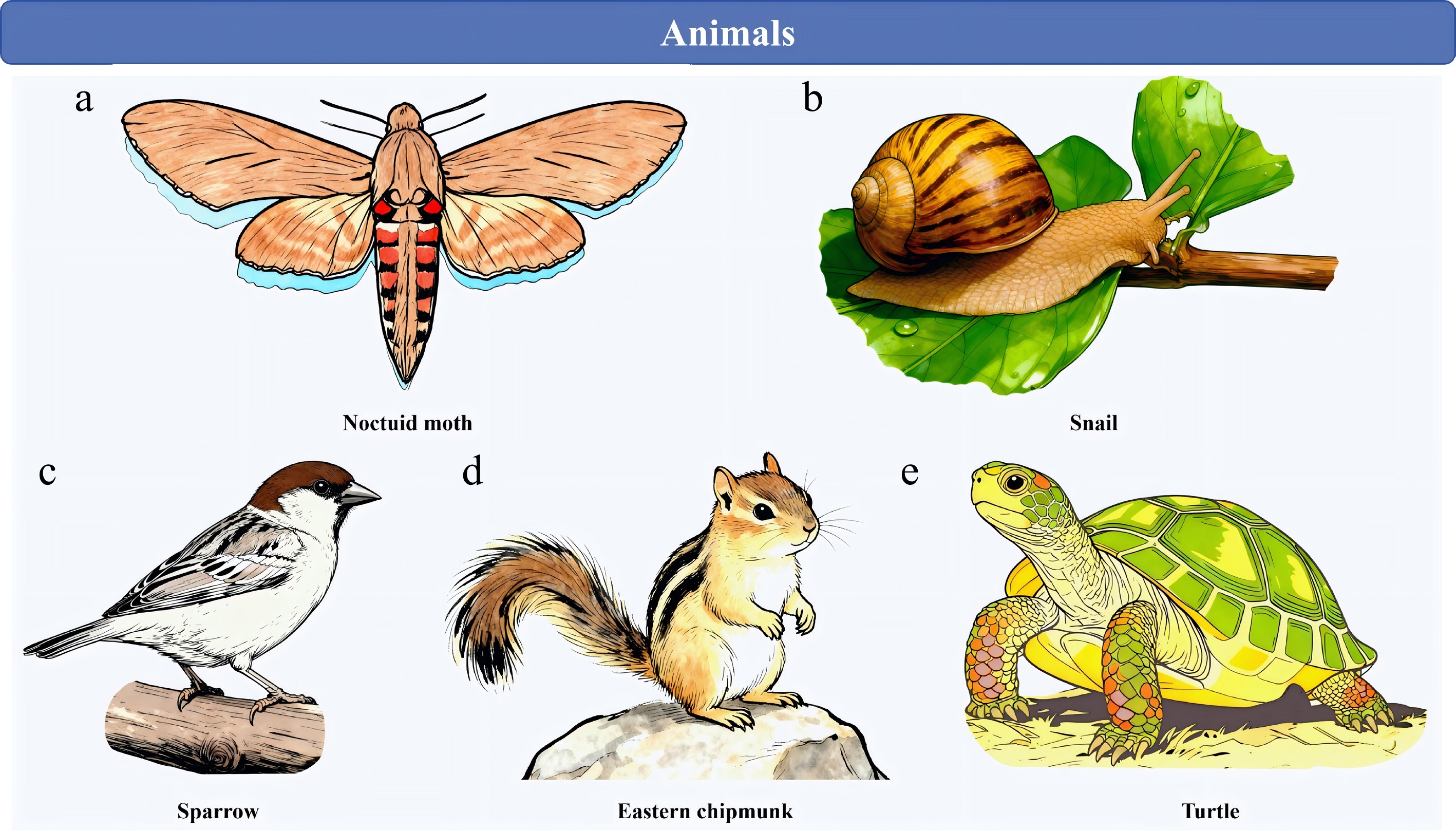

The soil/humus layer of forests—acknowledged as the primary habitat for dictyostelids—also sustains a diverse assemblage of small invertebrates, which possess the full capacity to facilitate the dispersal of dictyostelid spores[59,60]. In most scenarios, this dispersal process involves no more than the simple adhesion of spores to the body surfaces of the corresponding invertebrates; however, an ingestion-defecation pathway can also mediate such dispersal. As evidence, Huss successfully isolated dictyostelids from the gut contents of earthworms and pill bugs collected directly from natural field settings, further supporting the role of invertebrates in this ecological process[61]. These organisms move only short distances during their entire lives. This is not the case for vertebrate animals, some of whom move over considerable distances. The spores of dictyostelids have been isolated from insects. Stephenson & Landolt recovered dictyostelids from a noctuid moth (Fig. 6a)[62], and Stephenson et al. demonstrated that cave crickets could carry dictyostelid spores both internally and externally[63]. Landolt & Stephenson successfully recovered three dictyostelid species — specifically Dictyostelium purpureum, D. sphaerocephalum, and Polysphondylium pallidum — from the fecal samples of three large terrestrial snail individuals collected in Puerto Rico's Luquillo Experimental Forest (Fig. 6b). Notably, field observations at this study site revealed that these snails were commonly encountered both on the forest floor and on tree trunks located at significant heights above ground level[64].

Figure 6.

Dictyostelids rely on animal vectors for spore dispersal in many instances. (a) Noctuid moth. (b) Snail. (c) Sparrow. (d) Eastern chipmunk. (e) Turtle.

Vertebrate

Migratory songbirds

-

Suthers conducted research that confirmed ground-foraging migratory songbirds facilitate the transcontinental transport of dictyostelids, specifically between eastern North America and the Neotropics. In her study, eleven distinct dictyostelid species were isolated from the fecal samples of ground-foraging migratory birds native to eastern North America—including thrushes, finches, sparrows, and warblers—with samples collected both in the birds' breeding habitats and their wintering grounds (Fig. 6c). Given that ground-foraging birds regularly interact with the litter layer covering forest floors, they have a high likelihood of encountering dictyostelid spores in this microhabitat. This ecological interaction creates conditions that enable the long-distance dispersal of dictyostelids. Building on these observations, Suthers proposed a hypothesis: this bird-mediated dispersal mechanism likely explains, at a minimum, in part, why certain dictyostelid species exhibit an almost global distribution[65].

Terrestrial microvertebrates

-

In 1992, Stephenson & Landolt analyzed fecal samples obtained from nine vertebrate species. These species are prevalent and widely distributed within the temperate forests of eastern North America, and they include the red-backed salamander, white-footed deer mouse, eastern chipmunk, pine vole, Carolina wren, slate-colored junco, and big brown bat (Fig. 6d). All fecal samples were processed promptly after collection to ensure sample integrity. Through their analysis, the researchers isolated nine dictyostelid species, including Dictyostelium discoideum, D. sphaerocephalum, and Polysphondylium violaceum. Notably, each of these dictyostelid species was retrieved from fecal material of no fewer than three distinct vertebrate species. High probability, terrestrial microvertebrates possess the ability to transport dictyostelid spores, analogous to the capacity of birds.[62].

Reptiles

-

Tremble & Stephenson demonstrated that some reptiles, which have a dry scaly skin to which spores would seem unlikely to adhere, were also capable of transporting the spores of dictyostelids. Four dictyostelid species were isolated by the researchers using wet sterile swabs that had been applied to the ventral surfaces of multiple snake, lizard, and turtle species (Fig. 6e). There is no doubt that these reptilian animals come into contact with the litter and humus layer on the forest floor during their movement[66].

Large mammalian herbivore species

-

Sathe et al. gathered fresh dung samples from several large mammalian herbivore species within the Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary in South India (11º N), including the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), spotted deer (Axis axis), barking deer (Muntiacus muntjae), sambar (Cervus unicolor), and gaur (Bos gaurus). Processing of these specimens for dictyostelids yielded the identification of at least eight species[67]. Notably, multiple dictyostelid species were occasionally isolated from a single dung sample, a phenomenon that had previously been documented by Stephenson & Landolt[62]. Of particular interest, Sathe et al. successfully retrieved dictyostelids from yak (Bos grunniens) dung collected at a Himalayan Mountains site (34º N) situated at an altitude of 5,300 m[67].

Humans

-

Another animal vector likely to contribute significantly to dictyostelid dispersal is humans. To investigate human footwear as a potential dictyostelid vector. Perrigo et al. collected samples of soil adhering to the soles of eighteen boot pairs. Dictyostelids were isolated from almost all samples with a mass exceeding 5.0 g, and four different species were recovered, including one species new to science[45]. This unequivocally implies that there is a considerable potential that individuals engaging in hiking activities in natural environments are prone to dispersing the spores of dictyostelids, either over short distances or (if the soles of the boots or other footwear are not cleaned) even considerable distances.

Microhabitats

-

One of the more unusual microhabitats in which dictyostelids are known to occur is what has been referred to as 'canopy soil.' This is the layer of organic material that develops beneath epiphytes (both vascular and nonvascular) on the larger branches of trees in tropical rainforests. The occurrence of dictyostelids in this microhabitat was first reported by Stephenson & Landolt for a study site in Puerto Rico[64]. They later reported data for a number of other regions of the tropics[68]. One may question how dictyostelids are introduced to canopy soil — an environment that can be tens of meters above their primary ground-based habitat. In tropical forests, various animal types (including small mammals, lizards, salamanders, insects, and snails) possess the ability to travel from the forest floor up to the canopy layer. Presumably, these transport dictyostelid spores, either internally or externally, from the primary habitat for dictyostelids (on the forest floor) to the secondary microhabitat represented by canopy soil. The relative abundance of dictyostelids in canopy soil suggests that this happens on a regular basis. Interestingly, there are species of dictyostelids known from canopy soil that have not yet been recovered from samples collected from the ground.

Reproduction

-

Like most other organisms in which reproduction occurs by means of spores, the individual spores (or more often a mass of spores) are elevated above a substrate by a stalk/stipe or the morphological equivalent of this structure. This is the case for the sorus in dictyostelids. Presumably, this places the sorus in a more favorable position not to have spores carried away by air currents, which are probably very minimal for the situations in which dictyostelids occur, but to enhance their chances of contact with a passing vector. It is known that the sorophore of the dictyostelid fruiting body is very flexible and can bend in the direction of something to which it is attracted. Presumably, those species of dictyostelid in which the fruiting body is branched would have a better opportunity for a sorus to come into contact with a possible vector. It is well-established that the case for species in the traditional genus Polysphondylium, in which the fruiting body has whorls of branches, with each branch ending in a sorus. This would extend the effective space within which contact of a sorus with a vector is possible.

-

It is worth emphasizing that animals play a crucial role in the transmission of microorganisms, plant seeds, and other organisms. This role is not limited to Trametes versicolor but is widespread in various ecosystems[69−71]. Long-lived and continent-crossing or ocean-crossing migratory birds, such as warblers, in the process of spreading, maturing, and recruitment, their long-distance migration behavior itself constitutes a potential biological transmission vector[72,73]. Similarly, wild vertebrates play a key role in the seed dispersal and protection of the unique palm tree Butia odorata in southern Brazil, revealing the importance of animals in maintaining the structure of plant communities and biodiversity[69]. Mammals also have a dual role in the transmission of aquatic plants and micro-invertebrates between isolated wetlands[70]. Although these studies do not directly target dictyostelids, they confirm the universality of vertebrates as effective disseminators from an ecological perspective.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) technology has shown great potential in biodiversity monitoring and tracking of transmission routes. For example, eDNA is the genetic material released by organisms from the environment and can be sampled and analyzed through water bodies, soil, and even air[74,75]. In the freshwater ecosystem of Sicily, eDNA has been used to preliminarily assess the vertebrate biodiversity, and its rapid and non-invasive characteristics make it an effective alternative to traditional monitoring methods[75]. In the open grassland habitats of Queensland, Australia, eDNA from soil and air samples successfully detected terrestrial vertebrates, including Sminthopsis douglasi, so the eDNA technology can effectively detect vertebrates existing in the environment and provide clues for tracking their activities and potential microbial transmission. Although these studies mainly focus on vertebrates themselves, the principle of eDNA technology is also applicable to detecting the genetic material of microorganisms carried or transmitted by animals. Future research can attempt to detect the DNA of Trametes versicolor from eDNA samples of soil or water in the animal activity areas to assess the contribution of animals to the transmission of this species. The sampling methods of eDNA include water filtration, surface swabs, automatic or remote sampling, and sediment collection etc. Subsequently, eDNA is processed through purification, PCR amplification, or isothermal amplification, and species detection is carried out through lateral flow tests, qPCR/ddPCR tests, or metagenomic sequencing[74]. This process provides strong technical support for tracking the microbial transmission by animal vectors.

Microbial biogeography studies focus on the distribution patterns of microorganisms in space and time and the factors influencing them. A metagenomic assembly genome catalog study on microbial decomposers in vertebrate environments aims to enhance the understanding of microbial metabolism and ecological succession during vertebrate decomposition processes. In the land restoration research in the semi-arid region of Brazil, the nature of soil microbial communities is considered a key factor, and their diversity, resilience, and metabolic capacity are closely related to land management practices. These studies emphasize the importance of detailed analysis of microbial community composition and function, which is closely related to the tracking of the transmission mechanism of dictyostelids[76,77].

Apart from vertebrates, other animals also play important roles in the transmission of microorganisms. Insects are widely regarded as effective carriers of various pathogens. In medical settings, insects may serve as key hosts for multidrug-resistant bacteria[78]. Flies spread foodborne pathogens, including antibiotic-resistant and multidrug-resistant bacteria, in animal production systems, posing risks to food safety and public health[79]. Certain insect-specific viruses can affect the vector ability of mosquitoes for vector-borne viruses[80]. In addition, microorganisms can manipulate host location strategies to influence the behavior of arthropod vectors, thereby facilitating their transmission[81]. Although these studies do not directly involve dictyostelids, they provide extensive evidence regarding animals as microbial carriers and indicate the complex interactions between microorganisms and animal vectors.

In summary, although the evidence is not conclusive, the studies described in this paper strongly suggest that dictyostelids rely on animal vectors for spore dispersal in many instances. The animal vectors involved encompass a wide range of taxonomic groups and sizes, with one of the largest (humans) possibly having a greater role than generally appreciated. Evidently, spore dispersal in dictyostelids is a subject that warrants additional study.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: figure drawing and legend writing, Writing – original draft: Guo S; writing – review & editing: Guo S, Vlasenko AV, Vlasenko VA, Liu P, Stephenson SL; conceptualization: Guo S; data curation, formal analysis: Guo S, Li J, Li X, Wang Z, Sun D; funding acquisition: Li Y, Liu P; project administration: Liu P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32370020), the Science and Technology Development Program of Jilin Province (No. 20250205020GH), and the Program of Creation and Utilization of Germplasm of Mushroom Crop of "111" Project (No. D17014).

-

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Jilin Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Guo S, Li J, Li X, Wang Z, Sun D, et al. 2026. Morphological diversity and dispersal mechanisms of dictyostelid spores. Panfungi 1: e003 doi: 10.48130/panfungi-0025-0004

Morphological diversity and dispersal mechanisms of dictyostelid spores

- Received: 03 November 2025

- Revised: 18 December 2025

- Accepted: 19 December 2025

- Published online: 28 January 2026

Abstract: The dictyostelids (also called cellular slime molds) are a group of spore-producing eukaryotic microorganisms. Unlike other eukaryotic microorganisms, such as fungi and myxomycetes, in which spores appear to be largely dispersed by air currents, the spores produced by dictyostelids appear to have a rather limited potential for dispersal. The purpose of this paper is to consider the evidence of spore dispersal in dictyostelids by animal vectors, both vertebrates and invertebrates. Furthermore, the morphological characteristics of spores are elaborated upon herein. This review is intended to elucidate the relationship between the morphological traits of dictyostelid spores and their dispersal mechanisms, thereby offering a novel perspective for a more comprehensive understanding of the ecological functions and evolutionary adaptations of dictyostelids.

-

Key words:

- Slime molds /

- Amoebozoa /

- Morphological traits /

- Dispersal strategies /

- Transmission method