-

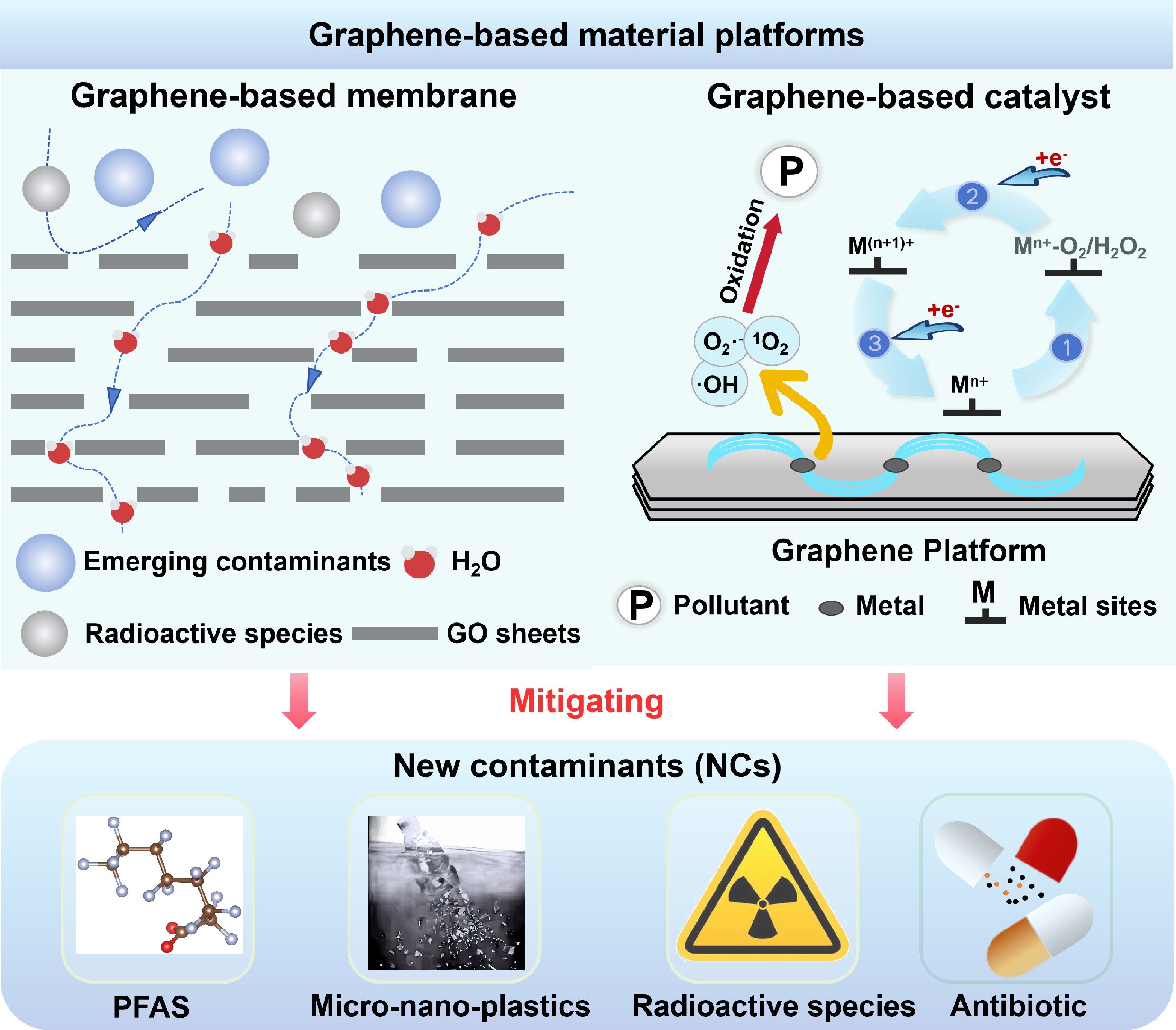

New contaminants (NCs), as defined by international environmental and health agencies, refer to substances of emerging concern that are not yet adequately regulated or monitored under current frameworks, despite their potential risks to human and environmental health[1−4]. With the acceleration of industrialization and urbanization, the widespread presence of NCs in the environment has garnered significant global attention[5−8]. Specifically, NCs originate from a wide range of sources, including industrial sectors such as pharmaceuticals, fertilizers, personal care products, and the nuclear industry, as well as diverse chemical and consumer groups. Key contributors encompass pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, surfactants, antibacterial agents, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), cleaning solvents, cosmetics, beauty formulations, and various packaged foods and beverages[9]. Several studies have reported that the concentration of NCs in wastewater typically ranges from ng L−1 to μg L−1 levels[10]. They are collectively defined by a suite of characteristics, including complex provenance, elevated toxic potency at trace concentrations, and pronounced environmental persistence and mobility, which fundamentally distinguish them from traditional pollutants[11−13].

The stark disparity between the approximately 500–1,000 contaminants regulated under existing frameworks and the proliferation of NCs, which remain largely undefined and unmonitored, has led to substantial socioeconomic and health burdens associated with unregulated NCs[1]. For example, PFAS, owing to their extreme environmental persistence and historically unregulated use, bioaccumulate in humans, and a substantial body of research links early-life exposure to deficits in key developmental domains, including cognition, language, motor skills, and socio-emotional performance[14]. The ability of plant leaves—a fundamental unit of the food chain—to directly absorb atmospheric micro-/nano-plastics poses a significant pathway for these particles to enter the food web; they have been detected in the human bloodstream and various tissues, consequently disrupting normal organ function[15]. Additionally, recent studies have found that the average microplastic (MP) abundance in marine fish was measured at 3.5 ± 0.8 particles per specimen, whereas in highly polluted waters, oysters exhibited the highest contamination level, reaching 99.9 particles per individual[16].

Moreover, radioisotope contamination represents a growing global nuisance, driven by the development of the nuclear industry[17]. Cesium-137 (137Cs) from the Fukushima accident, with its 30.1-year half-life, represents a long-term threat to environmental and human health, primarily due to persistent contamination of agricultural systems. Furthermore, its classification as an NC does not stem from its novelty as a radioactive substance, but rather from the growing recognition of its risks and the regulatory challenges it presents—illustrating how NCs transcend traditional categories based on their emerging profile of concern[18]. While present at lower concentrations in Fukushima's wastewater, tritium also constitutes a potential long-term environmental hazard. As the prevalence of such NCs increases in the environment, they significantly impede the efficacy of conventional treatment technologies.

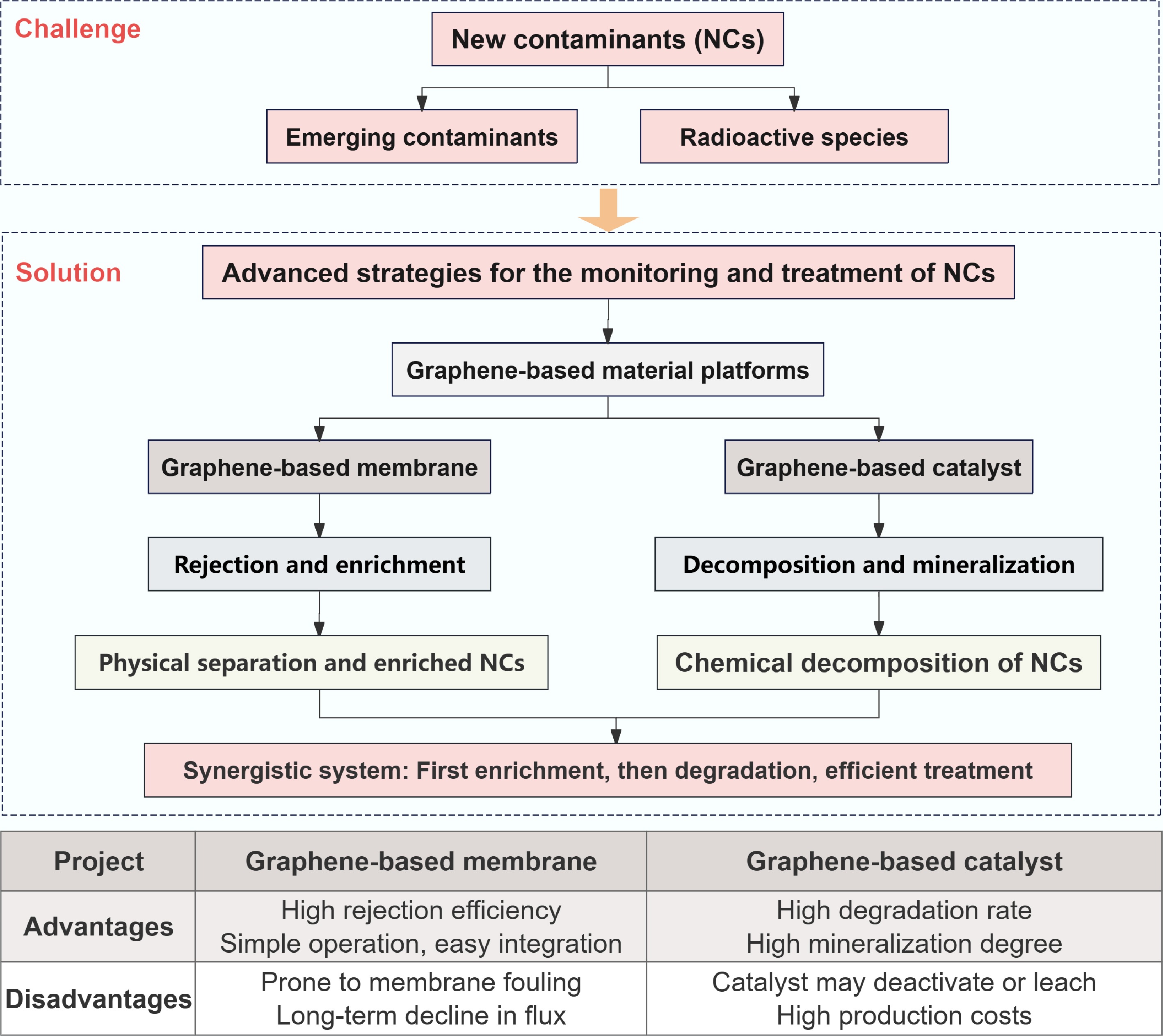

Graphene-based materials have garnered significant attention due to their tunable surface chemistry, high capacity, and multifunctional capabilities[19−23]. These properties position graphene-based materials as versatile solutions for environmental remediation, catalysis, and energy sectors, and they are equally critical for targeted applications in advanced water treatment membranes. Leveraging a research foundation built over decades, which confirms the remarkable effectiveness of graphene-based materials against traditional pollutants (e.g., heavy metals, dyes), substantial promise is anticipated for graphene-based membranes and catalytic technologies in addressing NCs. This perspective reviews the application of graphene-based membranes in the separation of NCs and the efficacy of graphene-based materials in catalytic degradation, proposing strategic avenues for future water treatment technologies.

A perspective is outlined that categorizes NCs as emerging contaminants and radioactive species, focusing on the progress of graphene-based membrane separation and catalytic platforms for their remediation (Fig. 1).

-

Graphene membranes demonstrate revolutionary advantages in water treatment, leveraging precise nanoscale pores and surface chemistry for exceptional efficiency and selectivity, while their atomic thinness enables high flux with minimal energy input[19]. Impermeable by nature, perfect monolayer graphene requires the deliberate introduction of nanopores to allow the transit of water, ions, and gases—a concept established in early theoretical research[24]. However, the experimental fabrication of large-area graphene sheets with uniform pore sizes remains a formidable challenge. Alternatively, graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets, known for their excellent dispersibility in various solvents and high aspect ratio, can be readily deposited onto porous substrates via spin-coating or vacuum filtration[19−21]. This process facilitates the formation of well-ordered laminates, making GO membranes highly effective for removing diverse contaminants. Excitingly, the structural versatility of graphene-based membranes gives rise to distinct transport paths, allowing their deployment in processes like pervaporation, reverse and forward osmosis, and opening new avenues for treating environmental pollutants[19].

To date, graphene-based membranes have shown great promise as an advanced barrier for the targeted removal of various contaminants. For conventional contaminants, the graphene-based membrane separation process based on the size exclusion effect of the two-dimensional nanochannels within the GO membrane has proven highly efficient and well-established for the removal of heavy metal ions and organic dyes. Techniques including thermal reduction[25], cross-linking[26], and intercalation[27] allow for the control over the interlayer spacing of GO membranes. Among them, thermal reduction offers procedural simplicity, but often leads to concomitant structural densification and the generation of uncontrolled defects. While the cross-linking approach significantly enhances the stability of GO membranes and allows for precise tuning of the interlayer spacing, the final d-spacing is inherently constrained by the molecular dimensions of the cross-linker employed. The intercalation method also enables precise interlayer control; however, the long-term operational stability is compromised by the gradual leaching of intercalants, resulting in performance attenuation. This leaching issue remains a pivotal bottleneck hindering the practical application of intercalated graphene-based membranes. For instance, the GO membrane cross-linked with amino acids achieved a water permeance of 191.0 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 and a high FeCl3 rejection rate of 98.2%, alongside enhanced operational stability[26]. Meanwhile, recent studies reported that the reduced GO membranes treated by electron beam irradiation can be used for dye and heavy metal ion removal. Remarkably, the membranes exhibited ultrahigh water permeance, ranging from 92.7 to 267.1 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, while simultaneously maintaining effective rejection rates for various dyes, as well as for multivalent heavy metal ions[28]. Interestingly, further studies demonstrated that utilizing GO nanosheets of a smaller lateral size can significantly improve the membrane's separation performance. Notably, the optimal membrane exhibited a water permeance as high as 819.1 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, coupled with a 99.7% rejection rate for FeCl3, an outcome attributed to the shortened and less tortuous transport pathways that facilitate rapid water permeation[29].

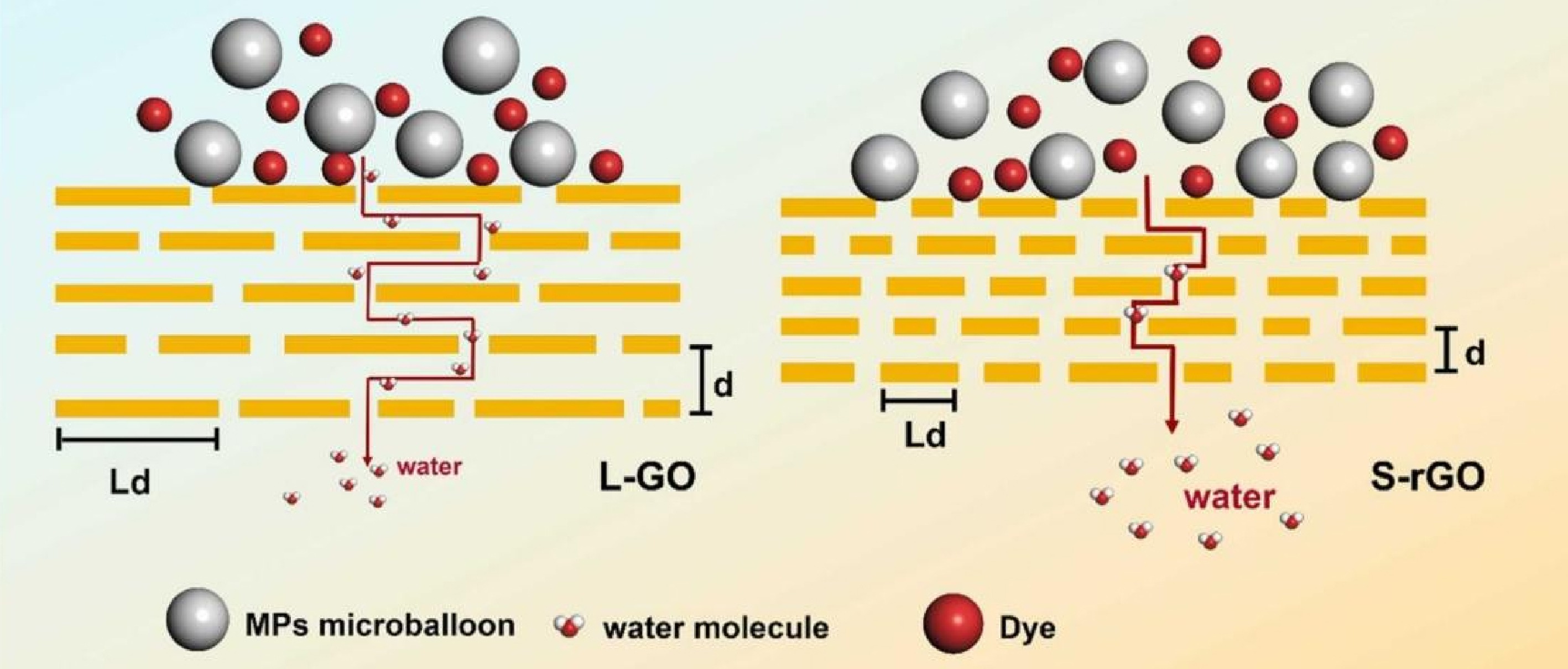

Recently, the GO membranes have also demonstrated excellent separation performance for the NCs. Yan et al. reported a reduced GO membrane with short Z-type water transport for the MP removal (Fig. 2), which demonstrated an outstanding performance by simultaneously delivering a water permeance as high as 236.2 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 and an MP rejection rate of 99.9%[30]. Notably, the removal of PFAS from water has received significant attention as a critical environmental challenge. A β-cyclodextrin-modified GO (GO-βCD) membrane was designed to separate PFAS in surface water and groundwater, which showed a permeance of 21.7 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 with a retention of over 90%[31]. Theoretical calculations confirmed that the mass transfer of PFAS molecules encounters a significantly higher energy barrier in the GO-βCD membrane compared to the pristine GO membrane. Recent relevant studies on NC removal using GO membranes have been systematically reviewed, as summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Water transport pathways and rejection mechanisms of graphene-based membrane[30].

Table 1. Separation performance of various graphene-based membranes

Membrane

typeContaminant Concentration (mg L−1) Rejection (%) Water permeance

(L m−2 h−1 bar−1)GO-βCD membrane[31] PFAS 0.1 90.0 22 NaOH-rGO membrane[32] MPs 10 99.9 484.2 LGO membrane[33] MPs 1 99.9 3,396 GO/ZrT-1-NH2 membrane[34] Antibiotics 100 99.0 10 G10(1)/P1.5-F100µL

membrane[35]Pendimethalin 10 99.9 20.7 GO-M-PhA-30

membrane[36]Pendimethalin 50 99.4 19.0 rGO membrane[37] Co2+ 22.7 99.9 72.4 CE7@ membrane[38] Cs+ 20 94.4 15.8 G/D/Z/P membrane[39] Cs+ 0.2 21.8 15,371 Currently, reports on the application of graphene-based membranes for treating NCs in water remain relatively scarce. This scarcity can be attributed to several intertwined challenges. The separation mechanisms for NCs in real water matrices involve intricate synergy between electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic effects, π-π conjugation, and hydrogen bonding, which are difficult to deconvolute and engineer. Furthermore, laboratory performance evaluations often fail to adequately simulate complex real-world conditions, creating a significant bench-to-application gap. Finally, the lack of scalable, reproducible fabrication and module integration techniques for graphene-based membranes further constrains both fundamental research and practical exploration.

On the other hand, the unique quantum effects and structural properties of graphene make it a promising candidate for the separation of radioactive species. Conventional processes for hydrogen isotope separation, such as cryogenic distillation, chemical exchange, centrifugation, thermal diffusion, and adsorption, are often plagued by high energy consumption and low efficiency. In this context, graphene-based membranes present a promising alternative for hydrogen isotope separation. Lozada-Hidalgo et al discovered that while atoms and molecules cannot permeate monolayer graphene, hydrogen ions can penetrate it[40]. Since deuterons experience a higher energy barrier than protons, their permeation through the graphene crystal is significantly slower. This phenomenon enables the development of a graphene-based electrochemical pump for hydrogen isotope separation, achieving a proton-deuteron separation factor of up to eight—far exceeding that of conventional cryogenic distillation (< 1.8)—while also being more energy-efficient, safe, and environmentally benign[41]. Recent studies also revealed that GO membranes assembled from nanosheets with lower oxidation degrees and larger lateral sizes exhibited both high rejection of deuterated water (HDO and D2O) and high water permeance[42]. Furthermore, functionalized GO membranes have also exhibited potential for application in the enrichment of Cs+ within complex aquatic systems[38].

-

Graphene-based membrane separation and graphene-derived catalytic degradation technologies serve complementary functions in the management of NCs. The former enables efficient enrichment and rejection of contaminants, facilitating their monitoring and subsequent advanced treatment. The latter promotes complete mineralization and elimination of contaminants, effectively preventing secondary pollution. By integrating these two approaches, a continuous technological framework is established from 'concentrative separation' to 'complete transformation', allowing for precise and comprehensive control throughout the entire contaminant management process.

Graphene-based materials possess unique properties such as ultra-high electron mobility, high specific surface area, high surface functional group density, and wide-spectrum absorption capacity, making them an ideal platform for catalytic degradation of pollutants[43−46]. Their two-dimensional structure not only facilitates the construction of efficient multi-heterojunctions but also significantly enhances the catalytic degradation efficiency by promoting interfacial charge separation and providing abundant adsorption sites, thereby achieving a synergistic effect. Graphene-based materials serve as versatile catalytic platforms, offering novel pathways for the remediation of NCs.

Previous studies have extensively investigated their application in degrading conventional dyes and other organic pollutants. Recently, a T-shaped Fe2O3@FeOCl@graphene composite catalyst was developed[47]. Based on the cation-π interaction between graphene and the metal precursor, this catalyst enables the confined growth of Fe2O3 nanosheets and the vertical assembly of FeOCl nanosheets. This unique configuration overcomes the traditional trade-offs among adsorption, activation, and desorption processes involving •OH radicals. As a result, the catalyst achieved a degradation conversion rate of 1.65 × 10−3 min−1 for bisphenol A, which is more than an order of magnitude higher than that of traditional materials. Furthermore, a graphene-controlled all-solid-state synthesis route was developed to construct atomically dispersed FeOX alongside Fe2O3 nano-islands at low temperature, a structure tailored to enhance the three critical steps in peroxydisulfate-driven Fenton-like oxidation: reactant adsorption, O–O bond activation and reactive species desorption[48]. Meanwhile, the graphene material platform can also serve as a highly versatile platform in photocatalysis, demonstrating exceptional performance across a variety of reaction systems. The ZnO-reduced graphene oxide (ZnO-rGO) nanocomposites displayed a degradation efficiency of approximately 99% for high-concentration methylene blue (200 mg L−1) within 60 min through the synergistic photogenerated charge separation and free radical oxidation pathways[49]. Compared with pure ZnO and rGO, the ZnO-rGO composite showed an improvement of 25% and 43%, respectively.

Owing to their high C–F bond energy and stability, NCs like PFAS exhibit marked environmental recalcitrance, resulting in a persistent threat to both ecosystem integrity and public health[50]. Traditional advanced oxidation processes have limited efficiency in breaking the C–F bonds and achieving complete mineralization of PFAS. Therefore, advanced catalytic systems based on graphene have attracted extensive attention and have demonstrated a common C–F bond breaking mechanism in various advanced oxidation processes. In electrochemical oxidation systems, the graphene-based anode initiates the decarboxylation or desulfonation of PFAS through direct electron transfer, generating perfluoroalkyl radicals that subsequently undergo a continuous 'CF2 unit sequential removal-defluorination' process, ultimately mineralizing into F−, CO2, and SO42−[51]. In photocatalytic systems, the hydroxyl radicals (•OH) photogenerated on the surface of TiO2-rGO composites attack the carbon site adjacent to the carboxyl group of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), triggering decarboxylation and generating perfluoroalkyl radicals, which then undergo a 'hydration-elimination-hydrolysis' cycle to sequentially remove CF2 units and release F−, ultimately achieving complete mineralization of PFOA into CO2 and H2O[52]. Although electrochemical oxidation initiates PFAS degradation via direct electron transfer and photocatalytic systems through •OH radical attack, both processes share a common reaction pathway: 'decarboxylation or desulfonation to form perfluoroalkyl radicals, followed by sequential elimination of CF2 groups and progressive C−F bond cleavage', ultimately leading to complete mineralization of the perfluorocarbon chain.

Similarly, for the catalytic degradation of polymer-based pollutants like MPs, the core lies in achieving oxidative cleavage of the polymer backbone. This process is initiated by photoexcitation-induced charge separation and migration, driving the continuous generation of reactive oxygen species. When graphene and semiconductors form heterojunctions, graphene, as an efficient electron-conducting medium, can significantly suppress the recombination of photogenerated carriers, thereby enhancing the yield and reactivity of reactive oxygen species. These highly oxidative species attack the C−H and C−C bonds on the surface of MPs, triggering chain oxidative cleavage, which is manifested as an increase in the carbonyl index, surface erosion, and the expansion of microscopic cracks, ultimately leading to the fragmentation and mineralization of the polymer. Research indicates that the graphene/TiO2 heterojunction can effectively accelerate this cleavage process by enhancing the efficiency of charge separation[53]. It should be noted that if graphene is not integrated in the form of a heterojunction but coexists with MPs as a dispersed phase, it may inhibit the photocatalytic reaction due to physical shielding and chemical quenching effects[54]. Therefore, the structural configuration of graphene and its interface interactions with pollutants and catalysts are key to regulating its catalytic degradation performance.

To effectively achieve the above reaction pathway, a variety of graphene-based catalytic degradation systems have been designed and optimized. In electrochemical cooperative technologies, reduced graphene oxide aerogel (rGA) modified by Fe3O4 or Cu nanoparticles was used as the cathode, coupled with boron-doped diamond (BDD) anode to construct an efficient heterogeneous Fenton-like system[55]. XPS and XRD analyses confirmed that the metal nanoparticles were stably loaded onto the three-dimensional rGA framework through chemical bonding, forming numerous catalytically active sites. Under the action of current, the rGA cathode can effectively activate H2O2 to generate a large amount of •OH radicals, while the BDD anode directly oxidizes the pollutants. The combined effect of both achieves the efficient degradation and fluorine removal of PFOA. UPLC-MS/MS analysis of the intermediate products revealed the degradation pathway of PFOA through sequential defluorination, providing direct evidence for the mineralization process. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy indicated that the loading of metal nanoparticles significantly enhanced the electron conductivity of the cathode, thereby improving the catalytic efficiency; the SEM images after the cyclic experiments proved the good stability of the catalyst structure.

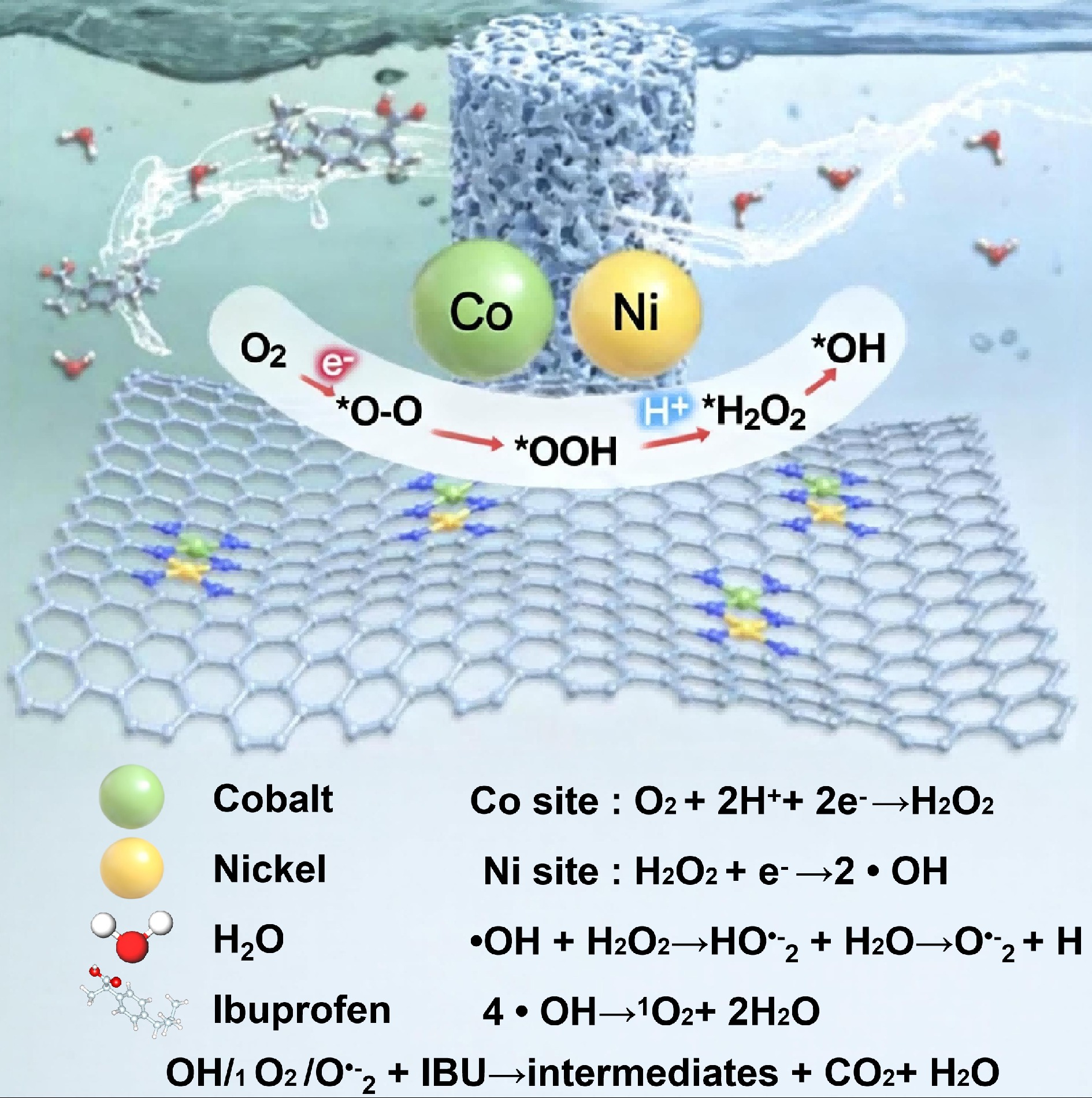

Additionally, the atomically engineered NiCo/GO aerogel functioned as an efficient cathode for in-situ H2O2 generation[56], achieving the degradation of ibuprofen (IBU) in water (2 mg L−1) at an energy consumption of approximately 0.660 kW h m−3. Theoretical calculations indicated that the Co sites preferentially adsorb O2 molecules to promote H2O2 generation, whereas the Ni sites serve as active centers for H2O2 dissociation and activation (Fig. 3). The catalytic activity in single-atom systems is governed by the electronic interaction between the graphene support and the metal center. X-ray absorption spectroscopy confirms that MN4 structures anchor Ni, Co, or Fe atoms at graphene double vacancies, forming atomically dispersed active sites. Coordination-induced charge transfer and orbital coupling modulate the metal d-band center, which influences intermediate adsorption and yields the oxygen evolution activity trend: Ni > Co > Fe. This demonstrates an atomic-level electronic structure-function relationship. Through spectroscopy and theoretical calculations, charge distribution between carbon and the metal site and its effect on the d-band center are quantified, clarifying how adsorption energies and reaction barriers in oxygen electrocatalysis are optimized. Thus, the high efficiency of the NiCo/GO system arises from graphene’s precise electronic tuning of the metal center, enabling concerted thermodynamic and kinetic optimization of the catalytic cycle beyond a single active site.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of the electro-Fenton process for the treatment of emerging contaminants[56].

Interestingly, integrating cobalt-doped g-C3N4 nanosheets into a membrane yields a nanoconfined environment that combines catalytic and separation functions[57]. The system demonstrates exceptional performance due to confinement-enhanced mass transfer and an optimized reaction pathway, leading to the rapid degradation of pollutants. In the field of photocatalysis, the MoS2/rGO composite exhibits outstanding perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) degradation performance under indoor fluorescent light irradiation. In this system, rGO serves as an efficient electron-transfer medium, significantly enhancing the separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs in MoS2 while suppressing their recombination[58]. This synergistic interaction increases the yield of reactive oxygen species, leading to efficient decomposition and mineralization of PFOA. In addition, recent advances in the degradation of NCs using graphene-based materials have been systematically summarized, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Catalytic performance of various graphene-based catalysts

Graphene-based catalyst Contaminant Concentration

(mg L−1)Degradation efficiency (%) CMCD-TiO2@

Fe3O4@rGO[59]Tetracycline 20 83.3 MnFe2O4@

Bi2WO6-GO[60]Tetracycline 10 99.3 rGO-TiO2[61] Diclofenac 10 85.5 rGO-CNCF[62] Sulfamethazine 10 99.9 Ti/TiO2-rGO[63] PFOA 50 70 AgBr/GO/Bi2WO6[64] Tetracycline / 84 GO/SCN[65] Bisphenol A 20 89.5 Pt/TiO2@NRGO[66] Tetracycline 27 81 Fe/g-C hybrid[67] PFOA 1 > 85 The research on graphene-based catalytic systems for the degradation of NCs has made significant progress, but their practical application still faces challenges. Key challenges in catalyst preparation, such as high synthesis costs, poor stability of nanomaterials, and potential environmental risks, currently hinder the practical deployment of graphene-based catalysts. Future efforts should prioritize the development of low-cost, scalable fabrication routes to enable economically viable production. Simultaneously, a deeper investigation into the long-term operational stability of these nanocatalysts in complex, real-world matrices is essential. Furthermore, a comprehensive and proactive assessment of their potential environmental fate and long-term ecological impacts must be integrated into the design process. Addressing these fundamental issues—cost, stability, and safety—will be critical to unlocking the full application potential of graphene-based catalysis in environmental remediation.

-

In conclusion, graphene-based materials represent a transformative platform with unparalleled potential to address the complex challenge of NCs. Their tunable surface chemistry, high capacity, and multifunctional capabilities position them not merely as incremental improvements but as foundational elements for next-generation remediation technologies. Moreover, the remediation of NCs in aquatic environments using graphene-based materials necessitates the integration of multidisciplinary expertise, including materials science, environmental engineering, chemistry, and toxicology, to establish a systematic research framework. This integrated approach is essential for effectively addressing current challenges posed by NCs and for building robust technical foundations to mitigate future environmental risks. Several meaningful outreach priorities about graphene-based materials are outlined below:

(1) Rational design of short-range mass-transfer nanochannels in graphene-based membranes. Future efforts should prioritize the construction of well-defined, stable nanochannels to fundamentally overcome the permeability-selectivity trade-off. This requires precise control over interlayer spacing, pore functionality, and structural durability under operational conditions, thereby significantly enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of NCs removal.

(2) Preconcentration and detection integration using graphene-based molecular sieves. Exploiting the precise molecular/ionic sieving properties of graphene-based membranes to enrich trace-level NCs and radioactive nuclides presents a promising avenue for enabling rapid, sensitive environmental monitoring. Research should focus on coupling selective capture with in situ detection platforms to develop continuous sensing systems.

(3) Development of graphene-based single-atom catalytic membranes. Integrating selective separation with catalytic degradation via single-atom catalysts embedded in graphene membranes represents a critical step toward energy-efficient, coupled remediation processes. Future studies should aim at designing stable, active, and selective catalytic interfaces that allow simultaneous separation and degradation of NCs in a single unit operation.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Junjie Chen: conceptualization, methodology, visualization, writing − original draft, writing-review & editing, data curation, funding acquisition; Yichi Zhang: visualization, writing − original draft, writing − review & editing, data curation; Shirui Wang: visualization, writing − original draft, writing − review & editing, data curation; Xing Liu: visualization, methodology, data curation; Chaoqi Ge: data curation, funding acquisition; Lin Shi: data curation, funding acquisition; Zetao Wang: data curation, funding acquisition; Yongchun Wei: supervision, writing − review & editing, funding acquisition, project administration; Guosheng Shi: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing − review & editing, funding acquisition, project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data used in this article are derived from public domain resources.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12574227), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 24010700200), the Thousand Talents Plan of Qinghai Province, the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 25ZR1402157), the Natural Science Foundation of Qinghai Province of China (Grant No. 2023-ZJ-940J), the Independent Research Project of Seventh Research and Design Institute of China National Nuclear Corporation (Grant No. KY202306), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (Grant No. GZC20252186 and 2025M783410).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

New contaminants challenge conventional treatment and graphene offers solutions for their remediation.

Recent advances in graphene-based membrane separation and catalytic degradation systems are critically reviewed.

Perspectives: rational nanochannel design, membrane preconcentration and integrated separation-oxidation systems.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen J, Zhang Y, Wang S, Liu X, Ge C, et al. 2026. A perspective on graphene-based material platforms for mitigating new contaminant. New Contaminants 2: e004 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0026-0002

A perspective on graphene-based material platforms for mitigating new contaminant

- Received: 10 November 2025

- Revised: 23 December 2025

- Accepted: 06 January 2026

- Published online: 29 January 2026

Abstract: The increasing prevalence of new contaminants in the environment severely limits the efficacy of conventional pollution control technologies. Graphene and graphene-based materials show significant potential for the remediation of new contaminants due to their tailorable and versatile physicochemical characteristics. Here, recent advances in graphene-based platforms for treating new contaminants are systematically summarized, which are categorized here as newly identified emerging contaminants and radioactive species. The discussion focuses on two key applications: the current status of graphene-based membrane separation for removing both conventional and new contaminants, and progress in graphene-based catalytic systems for degrading contaminants in aquatic environments. Future efforts should therefore prioritize the rational design of mass-transfer nanochannels, the application of graphene membranes in contaminant preconcentration for detection, and the development of integrated separation-oxidation catalytic systems, collectively paving the way for next-generation water purification technologies.