-

Low-temperature stress is a key environmental factor limiting the yield of solanaceous crops. Plants respond to low temperatures via intricate regulatory networks[1], in which hormone signaling pathways, including ABA[2], and transcription factor pathways, such as CBF and MYB[3−5], play pivotal roles. ABA, as a key stress-response hormone, not only regulates stomatal closure and osmotic balance but also enhances cold resistance by activating cold-responsive genes[6]. Concurrently, the ICE-CBF pathway serves as a conserved cold adaptation route, driving the expression of downstream cold-responsive proteins (e.g., Cold-Regulated genes, COR)[7]. However, the cross-talk between these two major systems, particularly how transcription factors integrate hormone signaling with transcriptional cascades, remains relatively understudied. Elucidating this regulatory network holds significant theoretical value for designing cold-tolerant crops with synergistic multi-pathway regulation.

MYB transcription factors exhibit remarkable functional polymorphism in diverse plant processes, including secondary metabolism, cell differentiation, and abiotic stress responses[8−10]. Studies indicate that Subgroup 2 R2R3-MYB proteins participate in low-temperature responses through various modes, enhancing plant cold tolerance by mediating the ABA signaling pathway. For instance, oil palm EgMYB111 enhances cold tolerance by controlling the transcription of key ABA regulatory genes EgSnRK2.1, EgSnRK2.3, and EgSnRK2.5[11]. Tomato SlMYB15 binds to upstream regulatory elements of ABA biosynthesis and signaling transduction genes SlNCED1 and SlABF4, leading to their upregulation and increased tomato cold tolerance[12]. Additionally, MYB transcription factors form heterodimers with bHLH transcription factors to activate the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, alleviating photo-inhibition damage. For example, the citrus R2R3 MYB transcription factor CsRuby1 is activated by two ethylene response factors, subsequently increasing citrus cold tolerance by upregulating anthocyanin synthesis[13]. Apple MdMYB308L interacts with MdbHLH33, acting as a positive regulator in apple cold tolerance and anthocyanin accumulation[14].

SmMYB113 is a key transcription factor responsible for compositional variation of anthocyanin and color diversity among eggplant peels[15]. Current evidence establishes that SmMYB113 participates in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in eggplant[15]. Under low-temperature conditions, SmCBFs proteins interact with SmMYB113, thereby indirectly activating key anthocyanin biosynthesis genes including chalcone synthase (CHS), and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), which consequently enhances anthocyanin production[16]. Based on our previous findings, SmMYB113-OE lines exhibited enhanced cold tolerance under low-temperature conditions, coupled with a marked upregulation of SmMYB113 expression and a significant increase in anthocyanin accumulation. These collective observations led to the selection of SmMYB113 as the primary focus of this study.

As a key signaling molecule in plant stress responses, ABA dynamically regulates stomatal movement, osmolyte synthesis, and stress memory formation by activating the SnRK2 (SNF1-related protein kinase 2) kinase cascade[17−20]. Low-temperature stress significantly induces endogenous ABA accumulation[21], while exogenous ABA application enhances cold tolerance[22], suggesting a profound interaction between ABA signaling and cold adaptation mechanisms. Studies show that ABI1 enhances ICE1 protein stability by regulating OST1 (Open Stomata 1) kinase-mediated phosphorylation, promoting CBF expression[23]. On the other hand, the ICE-CBF pathway, as a conserved axis for cold response, has been extensively validated in model plants such as Arabidopsis and tomato[24,25]. Upon cold exposure, ICE acts upstream in the cold response cascade as one of the earliest signals[26], driving the expression of CBF transcription factors by binding to the canonical MYC cis-element (CANNTG) in the CBF3/DREB1A promoter, thereby activating downstream cold-responsive genes like COR and RD (responsive to dehydration)[27,28].

Eggplant is an important protected vegetable crop. Its year-round production mode ensures a stable food supply but poses the challenge of maintaining normal growth under low-temperature conditions. In this study, it was found that SmMYB113 likely enhances eggplant cold resistance through a dual regulatory mode: directly activating ABA biosynthesis and interacting with core components of the ICE-CBF pathway, forming a synergistic hormone-transcription network. Therefore, SmMYB113 plays a crucial role during cold stress in eggplant, providing novel insights for improving low-temperature-tolerant eggplant varieties through molecular breeding.

-

The eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) materials used were the inbred line '108' (wild-type, WT) and T2 generation seeds of SmMYB113 overexpression lines, maintained by self-pollination in our laboratory. Eggplant seeds were surface-sterilized, soaked in warm water for 6–8 h at room temperature, and germinated in darkness at 28 °C until radicle emergence. Germinated seeds were sown in plug trays filled with a peat moss : vermiculite (3:1, v/v) substrate mix and cultivated in a glass greenhouse at Shandong Agricultural University (Shandong, China) under natural light. Seedlings at the two-true-leaf stage were transplanted into pots containing the same substrate mix. Plants were irrigated with Yamazaki eggplant nutrient solution for water and nutrient management; other cultivation practices followed standard protocols.

When seedlings reached the 5–6 true-leaf stage, uniform and robust plants were selected and subjected to low-temperature treatment in a growth chamber. Low-temperature conditions were set at a constant 5 °C with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod. Samples were collected at 0, 1, and 9 d after the initiation of low-temperature treatment. For exogenous ABA treatment, eggplant seedlings were sprayed with 200 μM ABA solution, one day before low-temperature exposure and then transferred to the growth chamber for cold treatment. Samples were collected at 0, 1, and 9 d after cold treatment initiation. All samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Determination of physiological and biochemical indices

-

The physiological and biochemical indices were determined as follows. Electrolyte leakage (EL) was measured by sampling leaves from the same position. Uniform leaf discs were punched, weighed to 0.2 g, and completely immersed in 50 mL centrifuge tubes containing 20 mL of deionized water. The samples were shaken at 200 rpm and 28 °C for 1–2 h. The initial electrical conductivity (EC0) of the deionized water and the conductivity after shaking (EC1) were recorded using a digital conductivity meter. Subsequently, the samples were boiled at 95 °C for 15–20 min, cooled to room temperature, and the final conductivity (EC2) was measured. Relative electrolyte leakage (REL, %) was calculated as [(EC1 – EC0) / (EC2 – EC0)] × 100%, with three biological replicates performed and the mean value reported. Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was determined using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content was quantified with a Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Superoxide anion (O2·−) content was assessed using the hydroxylamine oxidation method. Histochemical staining for H2O2 was carried out using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), and for O2·− using nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT); representative images of DAB and NBT staining in wild-type leaves under low-temperature conditions are provided for reference in Supplementary Fig. S1. ABA content was measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. Antioxidant enzyme activities were evaluated as follows: superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined by the NBT reduction method, peroxidase (POD) activity by the guaiacol method, catalase (CAT) activity by the ammonium molybdate colorimetric assay[29], and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity according to the method described by Nakano & Asada[30].

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

-

Total RNA was extracted using TaKaRa MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). cDNA synthesis was performed using the TransScript® One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis Super Mix kit (TRANSGEN, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using Vazyme® AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Without ROX) on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). The SmACT7 (Actin 7) gene was used as the internal reference gene for normalization. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method[31].

Transcriptome sequencing and analysis

-

Total RNA was extracted using an RNA extraction kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). RNA quality was assessed using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. mRNA library construction, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis were performed following the methods described by Li et al.[32].

Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) and yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays

Y1H

-

The SmMYB113 coding sequence was fused into the pGADT7 vector. The SmAAO4-1 promoter sequence was fused into the pABAi vector. Both constructs were sequentially co-transformed into the yeast strain Y1H Gold. Similarly, the SmICE2 coding sequence was fused into pGADT7, and the SmCBF1 and SmCBF2 promoter was fused into pABAi, then co-transformed into Y1H Gold. Positive clones were selected on SD/-Leu medium with or without Aureobasidin A (AbA, 100 ng·mL−1).

Y2H

-

SmMYB113 and SmICE2 coding sequences were cloned into pGADT7 and pGBKT7 vectors, respectively. Empty vectors served as controls. Recombinant plasmids were co-transformed into the yeast strain Y2H Gold. Transformants were plated on SD/-Trp/-Leu (-T/-L) medium and incubated at 28 °C for 2 d. Single colonies were then streaked onto SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp (-T/-L/-H/-A) medium (Clontech, Palo Alto, USA) and incubated at 28 °C for 2 d to identify positive interacting clones.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay

-

The BiFC assay was performed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains harboring the relevant constructs were grown to an optical density of 600 (OD 600) ≈1.5, centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min, and the pellets were resuspended in infiltration buffer (MS salts + 1.5% sucrose + 10 mM MES pH 5.6 + 10 mM MgCl2 + 150 μM acetosyringone). Suspensions were infiltrated into the abaxial side of tobacco leaves using a 1.5 mL syringe. Infiltrated plants were grown under normal conditions for 2 d. Lower epidermal peels were then examined for fluorescence signals using confocal microscopy.

Firefly luciferase complementation imaging (LCI) assay

-

Healthy N. benthamiana plants were prepared. Agrobacterium cultures were grown, pelleted, and resuspended in infiltration buffer as described for BiFC. Suspensions were infiltrated into the abaxial side of tobacco leaves using a 1.5 mL syringe. Plants were grown under normal light conditions for 2 d. Luminescence signals at the infiltration sites were detected and imaged using a low-light cooled CCD imaging apparatus (NightOWL II LB983, Berthold).

-

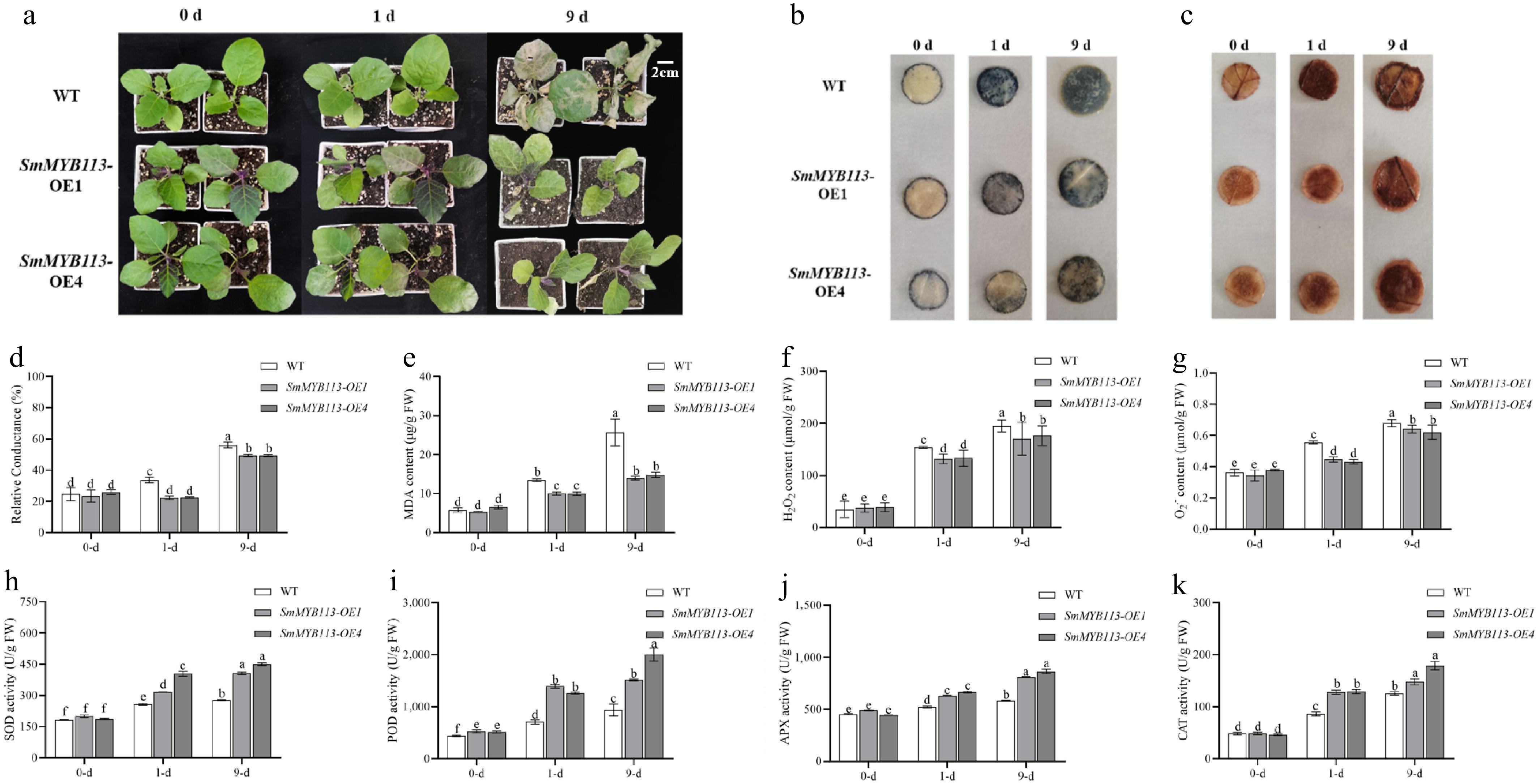

To investigate the relationship between SmMYB113 and eggplant cold tolerance, SmMYB113 overexpression (OE) lines were generated via Agrobacterium-mediated leaf disc transformation. Positive transgenic seedlings (Supplementary Fig. S2) were identified, and T2 seeds were harvested. Two OE lines (OE1, OE4) and WT seedlings were subjected to low-temperature (5 °C) treatment. Results (Fig. 1a) showed that after 1 d of cold treatment, no significant differences were observed between lines. However, after 9 d, WT seedling growth points died, while OE line seedlings maintained intact upper leaves and growth points without wilting. Metabolic characteristics are key indicators of stress resistance. Measurements of electrolyte leakage (REL) (Fig. 1d), and malondialdehyde (MDA) content (Fig. 1e) revealed that both were significantly lower in OE lines compared to WT after cold treatment. Furthermore, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Fig. 1f), and superoxide anion (O2·−) (Fig. 1g) contents were significantly lower in OE lines than in WT after cold treatment. Consistent results were obtained from NBT and DAB staining (Fig. 1b, c). Additionally, antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, POD, CAT, APX) were significantly higher in OE lines than in WT after cold treatment (Fig. 1h–k). These findings indicate that SmMYB113 overexpression confers stronger cold tolerance compared to WT.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic and physiological differences between WT and SmMYB113-OE plants under low-temperature stress. (a) Phenotypic differences under 5 °C (16 h light/8 h dark) at 0, 1, and 9 d. (b) DAB staining for H2O2 localization. (c) NBT staining for O2·− localization. (d) Relative electrolyte leakage (REL). (e) MDA content. (f) Colorimetric quantification of H2O2 content. (g) Hydroxylamine oxidation assay for O2·− content. (h)–(k) Activities of antioxidant enzymes SOD, POD, APX, and CAT. Values represent means ± SD of three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (p < 0.05). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Transcriptomics reveals a synergistic pathway network

-

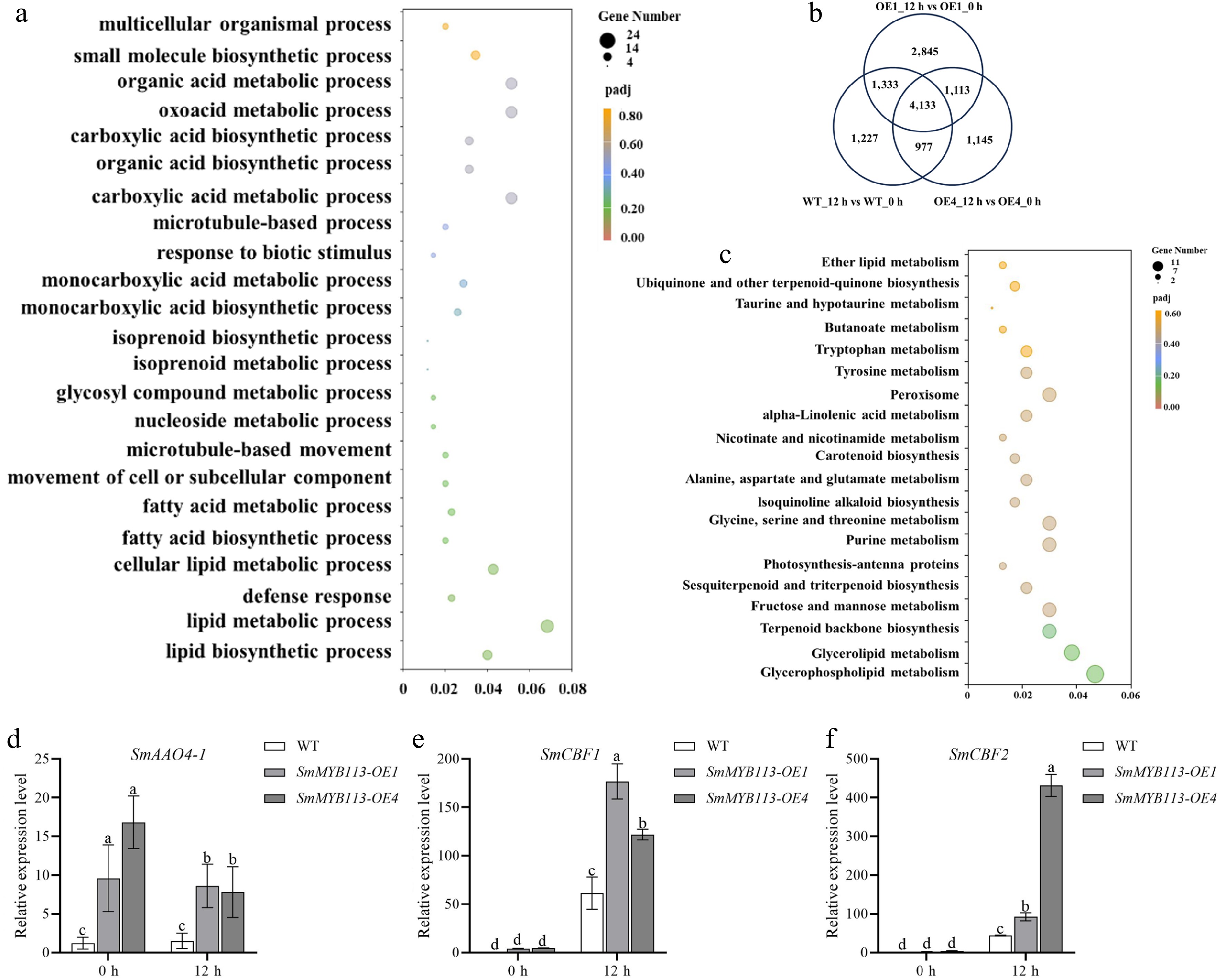

Through PCA and correlation analysis, it was detected that the three biological replicates within the same group exhibited tight clustering, confirming the reliability of the data for downstream analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in leaves of OE1, OE4, and WT plants at 0 h and 12 h after cold treatment initiation, using thresholds of FDR ≤ 0.001 and |log2FC| ≥ 2. The selection of 0 h and 12 h was based on the observation that the expression of SmMYB113 in WT plants peaked at 12 h under low-temperature treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 2b, 7,670, 9,424, and 7,368 DEGs were identified in the WT, OE1, and OE4 groups, respectively. A total of 4,133 DEGs were common to all three groups. For focused analysis, DEGs present in both OE1 and OE4 groups but absent in the WT group were selected, yielding 1,113 DEGs potentially involved in eggplant low-temperature stress response.

Figure 2.

Transcriptomic analysis reveals synergistic cold response pathways. (a) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the 1,113 DEGs common to OE lines but absent in WT. (b) Venn diagram of DEGs identified in WT, OE1, and OE4 plants under cold stress. (c) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of the 1,113 DEGs. (d)–(f) Expression levels of key genes in OE and WT plants under 5 °C (16 h light/8 h dark) at 0 and 12 h: (d) ABA biosynthetic gene SmAAO4-1, and cold response factors (e) SmCBF1, and (f) SmCBF2. Values represent means ± SD of three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (p < 0.05). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

GO enrichment analysis of the 1,113 DEGs (Fig. 2a) revealed significant enrichment in processes including 'lipid metabolic process', 'organic acid metabolic process', 'carboxylic acid metabolic process', 'oxoacid metabolic process', and 'lipid biosynthetic process'. KEGG pathway analysis (Fig. 2c) showed enrichment in 20 pathways, primarily 'glycerophospholipid metabolism', 'glycerolipid metabolism', 'terpenoid backbone biosynthesis', 'fructose and mannose metabolism', 'sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis', 'photosynthesis-antenna proteins', 'glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism', 'isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis', 'alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism', and 'carotenoid biosynthesis'.

Key DEGs of interest (Supplementary Table S1) included genes involved in ABA synthesis (SmAAO4-1, SMEL4.1_12g014560.1), cold response factors (SmICE2, SMEL4.1_03g029410.1), and CBF transcription factors (SmCBF1, SMEL4.1_12g001770.1; SmCBF2, SMEL4.1_03g007630.1; SmCBF3, SMEL4.1_10g023430.1). qRT-PCR confirmed that SmAAO4-1 and SmCBFs were upregulated in OE lines, consistent with transcriptomic trends (Fig. 2d−f). Further analyses investigated the interaction between SmMYB113 and these genes.

SmMYB113 enhances cold adaptation via ABA biosynthesis

-

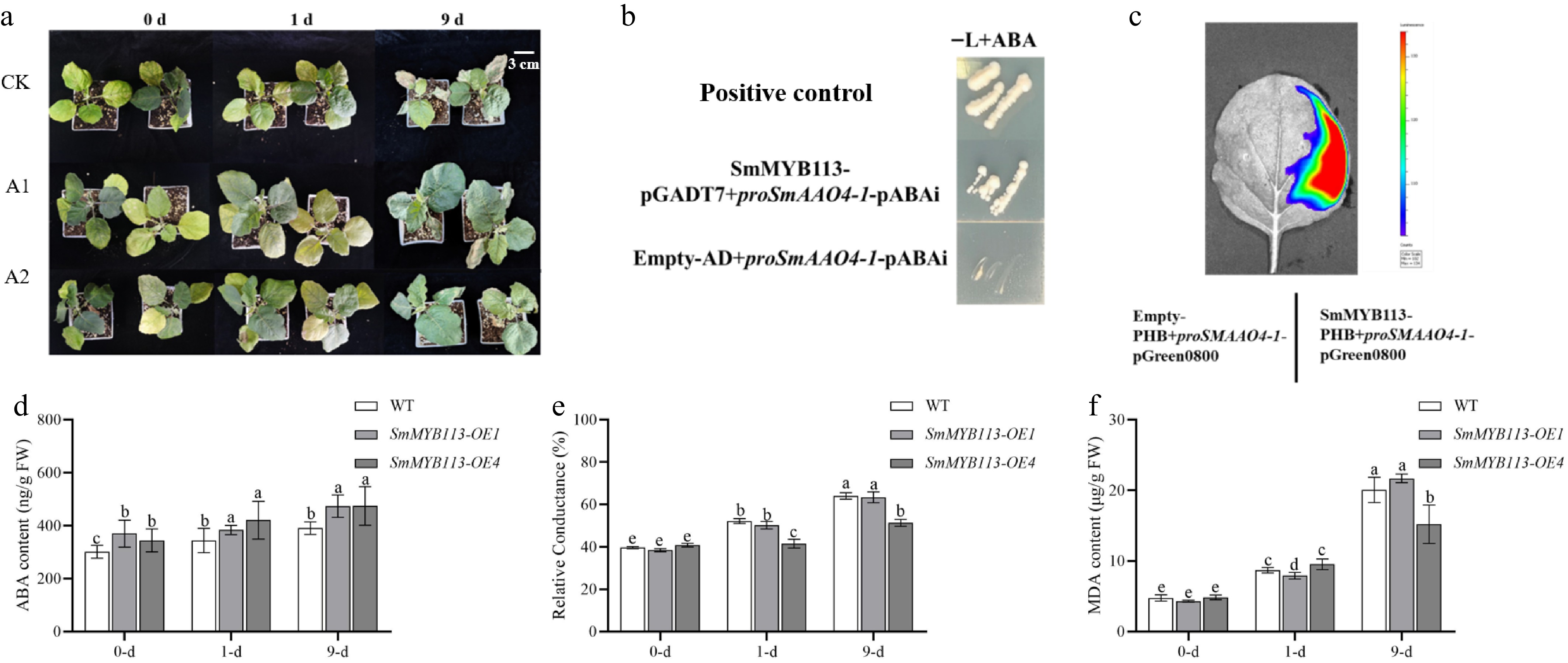

To study the regulatory relationship between SmMYB113 and ABA, ABA content was measured in OE1, OE4, and WT leaves at 1 and 9 d post-cold treatment. As shown in Fig. 3d, ABA content was significantly higher in OE1 and OE4 than in WT at 0 d. ABA levels increased in all lines at 1 and 9 d, but the increase was greater in OE lines. Compared to WT, ABA content in OE1 increased by 22.59%, 11.51%, and 21.26% at 0, 1, and 9 d, respectively. In OE4, it increased by 14.0%, 22.36%, and 21.56%. This indicates that SmMYB113 overexpression enhances ABA synthesis in transgenic lines.

Figure 3.

Role of ABA in cold tolerance and regulation of SmAAO4-1 by SmMYB113. (a) Phenotype of WT plants under 5 °C (16 h light/8 h dark) at 0, 1, and 9 d after pretreatment: CK (no pretreatment), A1 (water spray), A2 (ABA spray). (b) Y1H assay showing interaction of SmMYB113 with the SmAAO4-1 promoter. Yeast growth on SD/-Leu medium with AbA (100 ng·mL−1). (c) LCI assay in tobacco leaves confirming SmMYB113 binding to the SmAAO4-1 promoter and activating luciferase expression. Physiological indices in WT, OE1, and OE4 leaves under 5 °C (16 h light/8 h dark) at 0, 1, and 9 d: (d) ABA content, (e) Relative electrolyte leakage (REL), (f) MDA content. Values represent means ± SD of three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (p < 0.05). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

To confirm ABA's role in enhancing cold tolerance, WT plants were sprayed with water or exogenous ABA (200 μM). Results (Fig. 3a) showed that after 9 d of cold treatment, untreated (CK) and water-sprayed (A1) plants exhibited yellowing of lower leaves and wilting of growth points. In contrast, ABA-sprayed (A2) plants maintained intact leaves and healthy growth points. Measurements of REL and MDA content (Fig. 3e, f) showed no significant differences among treatments before cold stress. At 1 d post-stress, MDA content differences were non-significant, but REL was significantly lower in ABA-treated plants. By 9 d, both REL and MDA were significantly lower in ABA-treated plants compared to controls. This demonstrates that exogenous ABA application alleviates cold damage and enhances cold tolerance in eggplant. Furthermore, the phenotype of ABA-treated WT plants closely resembled that of SmMYB113-OE plants, indirectly supporting that SmMYB113 enhances cold adaptation by upregulating ABA synthesis.

SmAAO4 is a key gene for ABA biosynthesis in eggplant. To verify if SmMYB113 enhances ABA biosynthesis, Y1H assay showed that yeast co-transformed with SmMYB113-pGADT7 and proSmAAO4-1-pABAi grew on SD/-Leu medium containing AbA (100 ng·mL−1) (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, LCI assay confirmed that SmMYB113 binds to the SmAAO4-1 promoter and activates luciferase expression in tobacco leaves (Fig. 3c). Meanwhile, evidence was obtained that SmMYB113 forms homomultimers (Supplementary Fig. S5). These results demonstrate that SmMYB113 binds to the SmAAO4-1 promoter and activates its expression. In summary, SmMYB113 increases ABA content and enhances cold tolerance by activating SmAAO4-1 expression.

Physical interaction between SmMYB113 and SmICE2

-

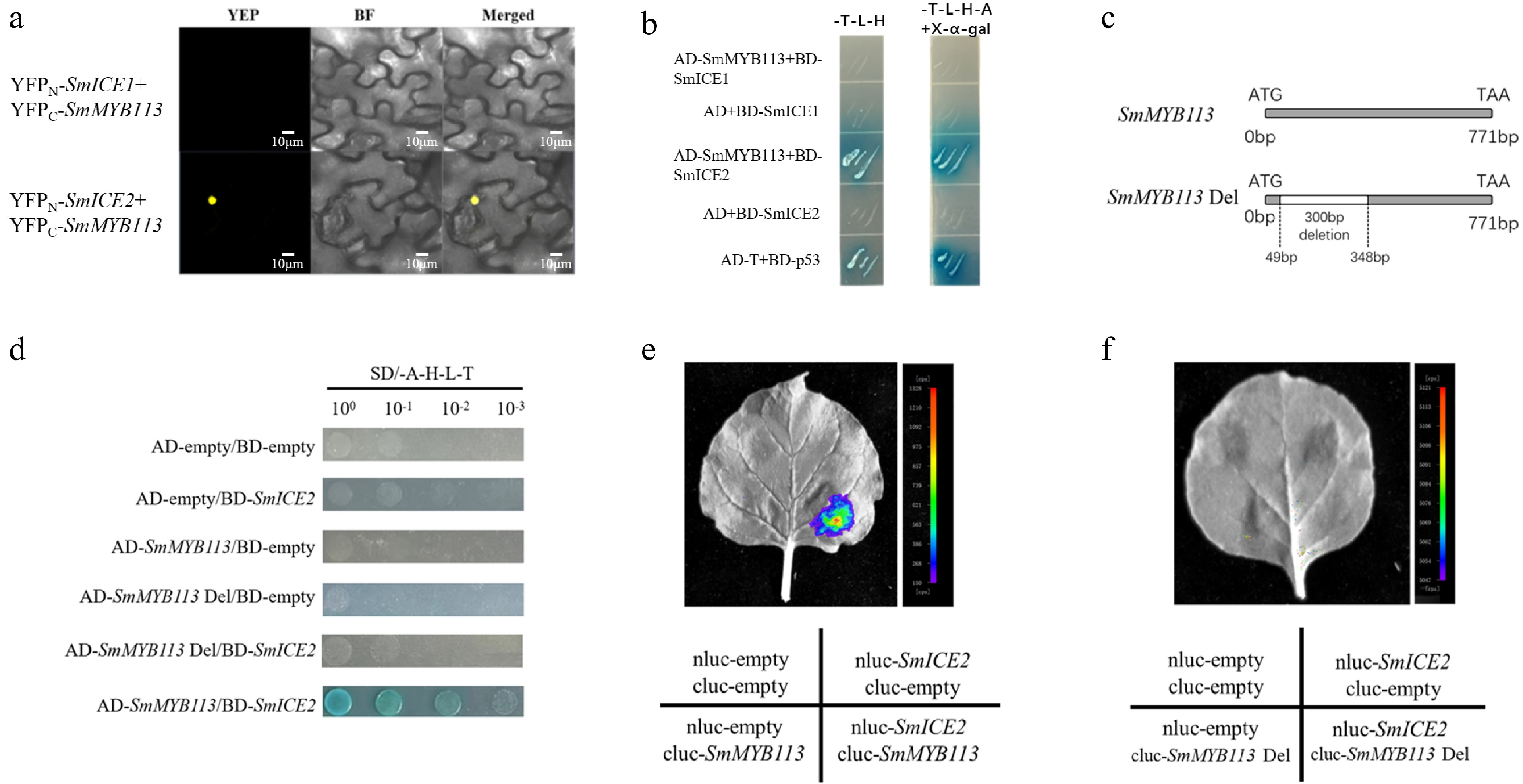

The interaction between SmMYB113 and SmICE proteins was investigated. BiFC assay, with SmMYB113 fused to YFPC and SmICE2 fused to YFPN, showed fluorescence signal in the nucleus of tobacco leaf cells (Fig. 4a), indicating interaction. Y2H assay (Fig. 4b) demonstrated that only yeast co-transformed with SmMYB113 and SmICE2 grew on stringent SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade (-T/-L/-H/-A) medium, while controls did not, confirming interaction in yeast. These results collectively demonstrate that SmMYB113 directly interacts with SmICE2.

Figure 4.

Validation of SmMYB113-SmICE2 interaction and identification of the interaction domain. (a) BiFC assay showing SmICE2-SmMYB113 interaction in tobacco leaf nuclei. SmICE1/YFPN and SmICE2/YFPN were paired with SmMYB113/YFPC. (b) Y2H assay confirming SmICE2-SmMYB113 interaction on SD/-T/-L/-H/-A medium. (c) Schematic diagram of SmMYB113 deletion mutant (SmMYB113Del, lacking residues 49−348). (d) Y2H assay showing loss of interaction between SmMYB113Del and SmICE2. (e) LCI assay showing strong fluorescence signal upon co-expression of full-length SmMYB113 and SmICE2. (f) LCI assay showing loss of fluorescence signal upon co-expression of SmMYB113Del and SmICE2.

To identify the key interaction domain in SmMYB113, online prediction indicated that residues 49-348 are crucial. Deletion of this 300 bp region (SmMYB113Del, Fig. 4c) abolished the interaction in Y2H assay (Fig. 4d). Consistently, LCI assay showed no fluorescence signal when SmMYB113Del and SmICE2 were co-expressed in tobacco leaves (Fig. 4f), unlike the strong signal observed with full-length SmMYB113 and SmICE2 (Fig. 4e). This confirms that the 49–348 bp region is essential for SmMYB113-SmICE2 interaction.

SmMYB113-SmICE2 interaction enhances SmICE2-mediated transcriptional activation of SmCBF2

-

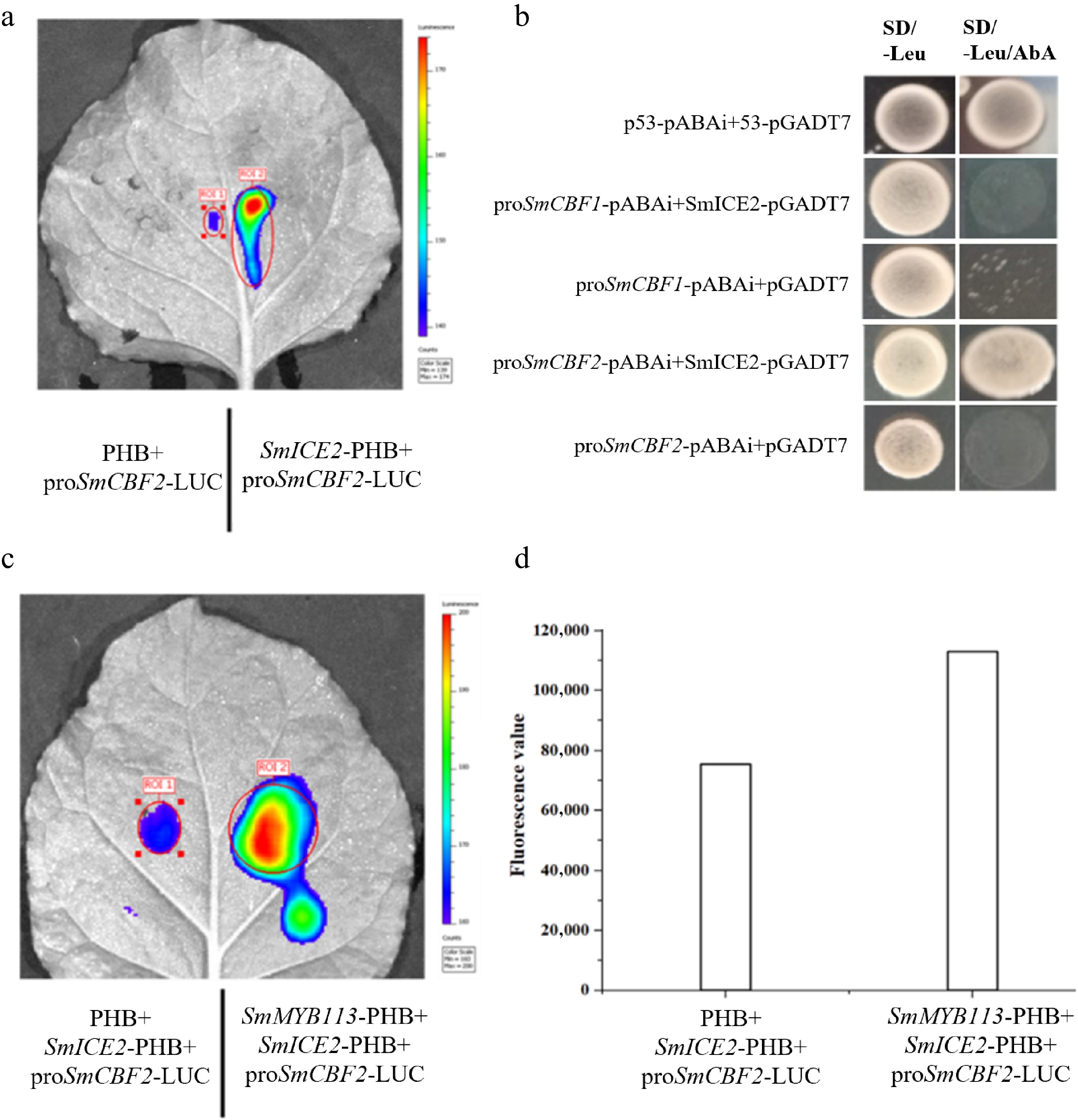

To validate SmICE2's ability to activate SmCBF transcription, SmICE2 was fused to the effector vector (pGreenII 62-SK), and the SmCBF2 promoter was fused to the reporter vector (pGreenII 0800-LUC). LCI assay (Fig. 5a) showed that SmICE2 binds the SmCBF2 promoter and activates luciferase expression. Y1H assay (Fig. 5b), with SmICE2-pGADT7 and proSmCBF2-pABAi, confirmed that SmICE2 activates SmCBF2 expression.

Figure 5.

SmMYB113-SmICE2 interaction enhances SmICE2-mediated transcriptional activation of SmCBF2. (a) LCI assay showing SmICE2 binding to and activating the SmCBF2 promoter. (b) Y1H assay confirming SmICE2 activation of SmCBF2 expression. (c) LCI assay demonstrating that co-expression of SmMYB113 and SmICE2 synergistically enhances luciferase activity driven by the SmCBF2 promoter compared to SmICE2 alone. (d) Quantification of luminescence intensity from (c).

Crucially, co-expression of SmMYB113 and SmICE2 significantly enhanced the luciferase activity driven by the SmCBF2 promoter compared to expression of SmICE2 alone (Fig. 5c, d). Quantitative analysis of luminescence intensity confirmed this synergistic enhancement (Fig. 5d). These results indicate that the SmMYB113-SmICE2 interaction enhances SmICE2's binding capability and transcriptional activation potential on the SmCBF2 promoter.

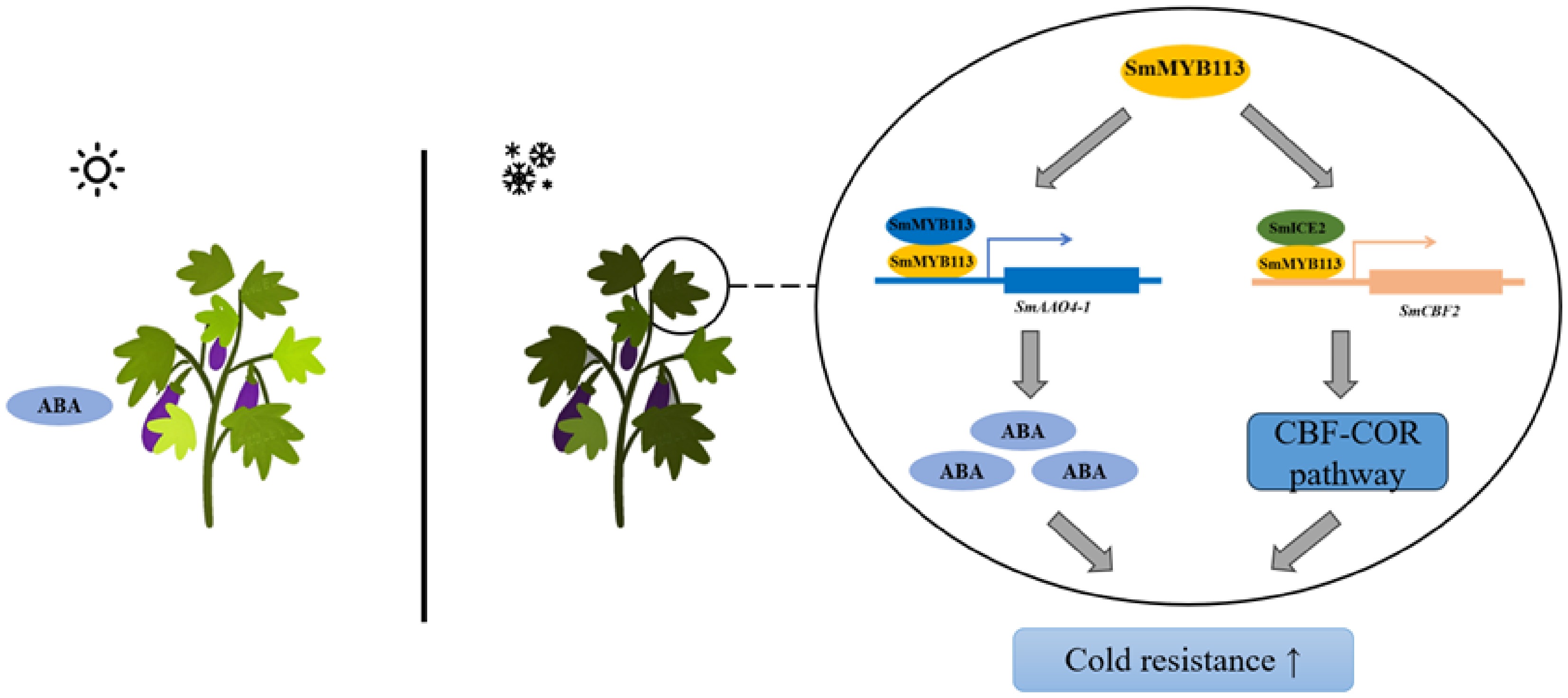

Figure 6.

Proposed model of SmMYB113-mediated cold tolerance in eggplant. Upon exposure to low temperature, SmMYB113 enhances cold tolerance through two mechanisms: (1) Transcriptional activation of SmAAO4-1, promoting ABA biosynthesis; (2) Physical interaction with SmICE2, enhancing SmICE2's transcriptional activation of SmCBF2, thereby participating in the ICE-CBF pathway.

-

This study demonstrates that overexpression of SmMYB113 in the eggplant cultivar '108' significantly enhances cold tolerance. Y1H and LCI assays revealed that SmMYB113 transcriptionally activates SmAAO4-1 expression, promoting ABA biosynthesis and thereby enhancing cold tolerance. Furthermore, Y2H and BiFC assays showed that SmMYB113 physically interacts with SmICE2, enhancing SmICE2's transcriptional activation of SmCBF2, thus participating in the ICE-CBF pathway to boost cold tolerance. This synergistic regulatory mode ensures enhanced cold tolerance under low-temperature stress while amplifying cold stress signaling efficiency through the integration of hormone and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms.

Anthocyanins, as important secondary metabolites, function as effective antioxidants that mitigate oxidative damage by utilizing their hydroxyl groups to neutralize free radicals and scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby maintaining osmotic balance and cellular redox homeostasis. Consequently, plants often synthesize anthocyanins to reduce oxidative injury induced by low-temperature stress[33]. Overexpression of the MYB transcription factor Rosea1 in tobacco has been demonstrated to enhance anthocyanin accumulation and significantly improve cold stress tolerance[34]. Interestingly, SmMYB113 has been previously reported to regulate anthocyanin accumulation[15]. Following low-temperature treatment, it was observed that the ROS content in eggplant leaves of the SmMYB113-OE lines was significantly lower than in WT lines. This indicates that anthocyanins accumulated in SmMYB113-OE eggplant leaves effectively scavenge cold-induced ROS, thereby conferring enhanced tolerance to low-temperature stress.

Plant hormones play vital roles in abiotic stress responses. Transcriptomic analysis of SmMYB113-OE and WT plants after cold stress revealed that DEGs were primarily enriched in secondary metabolite pathways and hormone synthesis/signaling pathways, with significant changes in ABA synthesis and signaling genes. ABA is one of the most important stress hormones, crucial in various physiological processes including seed dormancy, germination, stomatal movement, fruit development, and responses to biotic/abiotic stresses. Cellular ABA levels fluctuate dynamically in response to physiological and environmental cues, and these concentration changes determine ABA's role in plant physiology and development[35−37]. As a primary hormone in stress response, ABA is induced by multiple abiotic stresses like drought, salinity, and cold. Cold treatment induces ABA accumulation in plants like Arabidopsis and tomato[38]. The present measurements showed significantly higher ABA levels in OE lines compared to WT at the same time points under cold stress. Y1H and LCI assays proved that SmMYB113 binds to the SmAAO4-1 promoter, activating its expression. To cope with stress, plants accumulate more ABA in leaves, promoting stomatal closure, enhancing water balance, and inducing antioxidant defense systems to mitigate oxidative damage. Moreover, ABA can activate numerous cellular responses through signaling pathways and induction of HSPs and CBFs, promoting stress tolerance[39,40]. The present results collectively indicate that SmMYB113 overexpression increases ABA biosynthesis and accumulation in eggplant, positively regulating cold tolerance.

Exogenous ABA application enhances cold adaptation in various plants[41]. To further verify ABA's positive role in eggplant cold tolerance, exogenous ABA was applied. Cold stress duration increased membrane damage, reflected in rising REL and MDA. However, exogenous ABA application slowed this increase in REL compared to controls. ABA-treated plants also exhibited significantly lower O2·− and H2O2 levels than WT, indicating ABA reduces membrane damage and improves low-temperature stress tolerance.

Numerous studies have identified MYB transcription factors regulating plant cold tolerance via interaction with ICE to modulate downstream CBF expression. For example, AtMYB15 in Arabidopsis negatively regulates cold tolerance by repressing CBF expression; AtMYB15 mutants show elevated CBF expression and enhanced cold tolerance. AtMYB15 also interacts with ICE1 to regulate CBF expression[42]. The ICE-CBF-COR transcriptional cascade is the primary pathway for cold response in plants. Upon cold induction, upstream ICE transcription factors activate CBF expression, which in turn regulates downstream COR genes, enabling the plant to respond to cold stress. In Arabidopsis, AtICE2 overexpression induces downstream cold-responsive genes AtCBF1/2, enhancing cold tolerance by increasing proline content, SOD, and CAT activity[43]. The present results are consistent: transcriptomic analysis showed significant changes in ICE and CBF expression in OE lines. Investigation of how SmMYB113 participates in the ICE-CBF cascade revealed its interaction with SmICE2 and confirmed that SmICE2 activates SmCBF2 expression. Further study demonstrated that the SmMYB113-SmICE2 interaction enhances SmICE2's transcriptional activation of SmCBF2.

In summary, this study reveals a novel mechanism by which SmMYB113 enhances low-temperature adaptation in eggplant through the synergistic regulation of ABA biosynthesis and the ICE-CBF transcriptional cascade, forming a multi-layered network (Fig. 6). SmMYB113 enhances cold tolerance by upregulating endogenous ABA, an effect effectively mimicked by exogenous ABA application. This provides a theoretical basis and application prospects for developing low-temperature tolerance stimulants based on ABA analogs or ABA signaling activators (e.g., for protected seedling production or early spring transplanting). For instance, Cao et al.[44] reported an ABA analog named AMF that significantly improved plant drought resistance. Future research could focus on screening highly efficient, low-cost active substances, and their optimal application protocols. Furthermore, plant stress responses often involve multiple signaling pathways. Future studies could explore whether the SmMYB113-mediated cold tolerance pathway interacts with other hormone signals (e.g., jasmonic acid, ethylene) or second messengers (e.g., Ca2+, ROS), which would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the regulatory network underlying eggplant adaptation to low-temperature stress.

-

This study demonstrates that SmMYB113 significantly enhances low-temperature tolerance in eggplant through a dual regulatory mechanism. First, SmMYB113 transcriptionally activates the ABA biosynthetic gene SmAAO4-1, increasing endogenous ABA accumulation. Second, SmMYB113 physically interacts with the transcription factor SmICE2, enhancing its ability to bind and activate the promoter of SmCBF2. Our findings reveal a multilayered regulatory role for SmMYB113 in coordinating phytohormone signaling and transcriptional reprogramming to enhance cold adaptation. This mechanism provides valuable targets for molecular breeding of cold-tolerant eggplant varieties.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFD2300702), the Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. tsqnz20240804), the Taishan University Introduced Talent Scientific Research Startup Fund Project (101025KZ4019), the Special Fund of Vegetable Industrial Technology System of Shandong Province (SDAIT-05-11) and the National Natural Sciences Foundations of China (Grant No. 31672169).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yang F, Ji T, Li J; data collection: Yang G, Hu W, Li L, Liu W, Gao Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Yang G, Hu W, Ji T; draft manuscript preparation: Hu W, Yang G; draft review and editing: Yang F, Ji T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The raw data of the sequence during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Guobin Yang, Wenhao Hu

- Supplementary Table S1 Partial list of differentially expressed gene IDs.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Effects of cold stress on superoxide anion (O2•-) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation in eggplant leaves.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Identification of SmMYB113 overexpression lines.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation analysis of transcriptome data.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Expression pattern of SmMYB113 in WT plants under cold stress.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 SmMYB113 forms a homomultimer.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yang G, Hu W, Li L, Liu W, Gao Y, et al. 2026. SmMYB113 integrates ABA signaling with ICE-CBF transcriptional synergy to enhance low-temperature adaptation in eggplant. Vegetable Research 6: e003 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0046

SmMYB113 integrates ABA signaling with ICE-CBF transcriptional synergy to enhance low-temperature adaptation in eggplant

- Received: 24 June 2025

- Revised: 24 October 2025

- Accepted: 06 November 2025

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: The MYB transcription factor family represents the largest class of transcription factors in plants, playing crucial roles in regulating plant growth, development, and stress defense responses. This study demonstrates that overexpression of SmMYB113 in eggplant cultivar '108' significantly enhances cold tolerance. The results showed that SmMYB113 enhances cold tolerance through a dual regulatory mode: it binds to the promoter of the ABA biosynthetic gene SmAAO4-1, upregulating its expression and significantly increasing ABA content; meanwhile, it physically interacts with SmICE2, enhancing SmICE2's transcriptional activation capability on SmCBF2, thereby elevating the expression of downstream cold-responsive genes to combat low-temperature stress. These results indicate that SmMYB113 regulates eggplant cold tolerance through a multi-layered cold resistance mechanism integrating hormone signaling and transcriptional cascades.

-

Key words:

- Eggplant /

- MYB113 /

- Cold tolerance