-

Industrial development serves as the cornerstone of economic advancement; however, the escalating consumption of industrial chemicals has precipitated severe environmental issues that fundamentally undermine sustainable development[1,2]. Since 2010, the inventory of registered synthetic chemicals has surged from 150,000 to over 350,000 compounds[3]. These substances are released through value chains (from upstream production to downstream emissions)[4,5], posing persistent environmental exposure risks while generating complex contaminant mixtures throughout their life cycle[6,7]. This multi-pollutant synergy critically constrains accurate environmental risk assessments[8].

In response to these challenges, China issued the Action Plan for New Pollutants Treatment in 2022[9], which mandates life-cycle environmental risk management with emphasis on source control. Despite this policy imperative, current risk assessment methodologies remain static and endpoint-oriented[10], targeting end-of-life environmental emissions while neglecting pollutant formation pathways during industrial and environmental transformation. This methodological disconnect impedes source-downstream linkages, and fundamentally constrains life-cycle chemical governance[11]. Establishing quantitative connections between upstream industrial inputs and downstream pollutants, therefore, constitutes the pivotal scientific pathway toward holistic risk management.

The intricate distribution and transformation behaviors of industrial chemicals during production and environmental cycling present formidable barriers to establishing such source-emission linkages[12]. Within industrial processes, chemicals undergo complex reactions yielding intermediates, products, by-products, and unintended pollutants[13]. These transformations operate as a 'black box' due to poorly characterized material flows, hindering efforts to link emissions to their sources. While the resulting intermediates and by-products are discharged into environmental systems via wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs, the primary defense designed for contaminant reduction before effluent discharge), extensive research confirms that WWTPs lack sufficient efficacy in removing emerging contaminants[14,15]. Moreover, residual trace pollutants subsequently undergo further environmental transformations (e.g., speciation, degradation, and recombination) exponentially complicating the association between precursor chemicals and terminal environmental pollutants[16].

Compounding these challenges, mixture pollution permeates every life-cycle stage of industrial chemicals, introducing critical uncertainties into the overall risk. Dynamic industrial processes and environmental transformations generate transient contaminant combinations with emergent properties[17]. While existing methods capture instantaneous risks, they fail to identify high-risk components within complex mixtures or elucidate cumulative risk progression across the chemical life cycle[18]. Crucially, effective risk management requires quantification of risk flux, tracking hazard evolution from chemical synthesis through usage to environmental release, to pinpoint critical risk substances and life cycle hotspots. Without such dynamic profiling, targeted risk intervention remains unattainable.

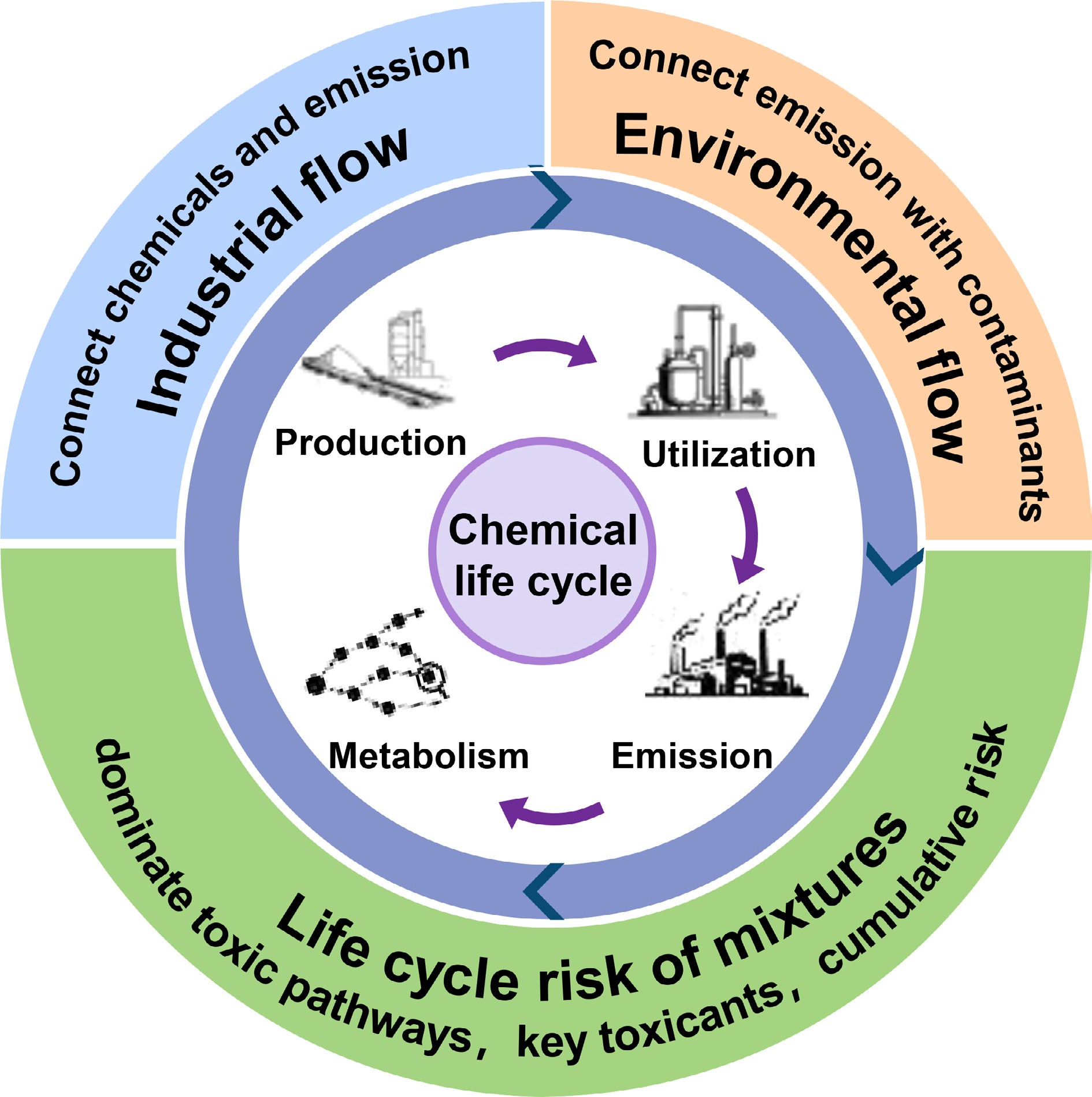

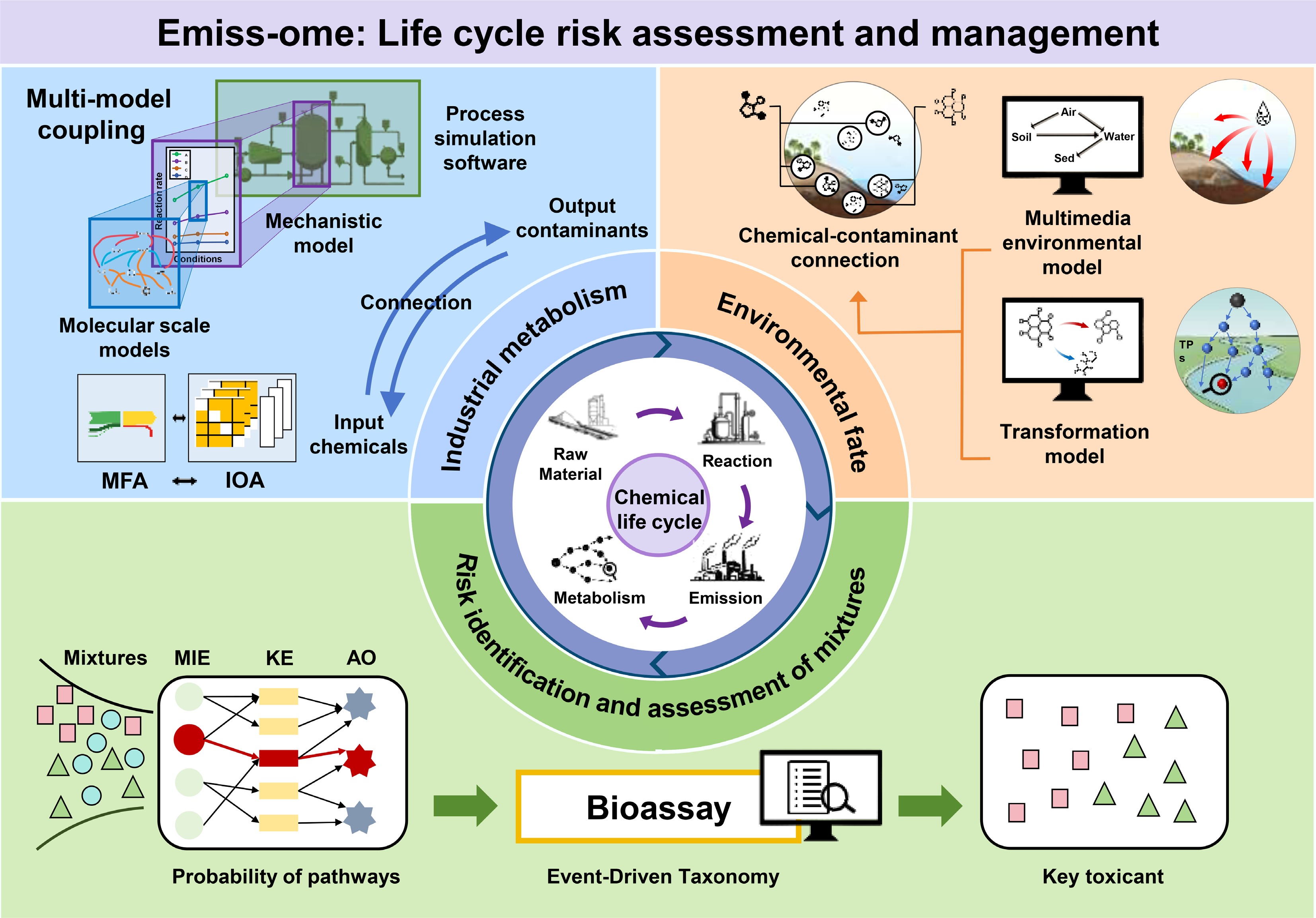

An emergent 'emiss-ome' paradigm has been previously proposed, which offers a transformative framework to address these limitations[19]. This approach conceptualizes chemical flows from industrial synthesis to environmental fate as a dynamic input-output network, enabling systematic tracking of chemical-pollutant relationships and establishing continuous life-cycle risk assessment[19]. The present perspective aims to synthesize advances in elucidating industrial-environmental pollutant linkages, examine critical knowledge gaps in complex transformation pathways, and propose an integrated 'emiss-ome' framework for dynamic risk assessment (Fig. 1). The present objective is to catalyze a paradigm shift from terminal risk identification toward proactive life-cycle risk governance.

-

To systematically reveal the life cycle impacts of individual chemicals, the first step is to clarify the dynamic linkages between inputs and output emissions during upstream industrial processes. Complex chemical reactions and transformations within industrial systems obscure relationships between input chemicals and emissions. Mapping these connections requires deciphering the 'black box' of material metabolism during industrial processing. Multiple analytical models and approaches have been developed to address this challenge by revealing intrinsic substance relationships between industrial inputs and outputs.

Material flow analysis (MFA) serves as a foundational methodology for tracking material movements within industrial systems. Anchored in the law of conservation of matter, MFA establishes input-output balances for individual processes or nodes to trace substance pathways and identify flow directions[20]. For instance, current research using dynamic MFA has systematically reconstructed ethylene production material flows from naphtha, coal, and ethane feedstocks[21]. By disaggregating production into process-based nodes and establishing precise input-output balances at each node, it can systematically quantify material fluxes from raw materials and energy inputs through primary products to by-products. However, conventional MFA typically focuses on linear flows of single or limited substances. It encounters limitations when analyzing multi-directional pathways, quantitative fluxes, and interactions within complex systems involving feedstocks, intermediates, primary products, by-products, and emissions[22,23].

To address these constraints, Input-Output Analysis (IOA) offers a systematic framework for examining intricate multi-substance, multi-node interconnections. Its core methodology constructs matrices representing intersectoral transactions, capturing direct and indirect dependencies across economic sectors[24]. When applied to industrial systems, a physical input-output table (PIOT) can be constructed to systematically characterize material flow relationships between different sectors within the industrial system[25]. The strength of this approach lies in the computational derivation of the Leontief inverse matrix, enabling calculation of 'total material requirements' and revealing input-output linkages across complete inter-industry supply chains[26].

A limitation persists, however, as conventional IOA relies on aggregated industry-level statistics and cannot resolve detailed material connections between specific process nodes within industrial systems[27]. Integrating MFA with IOA provides an effective solution: treating each process node as an independent sector and using MFA flow data to construct high-resolution PIOTs[28]. This hybrid approach preserves MFA's process-level quantification accuracy while leveraging IOA's matrix framework to uncover direct and indirect material relationships across multiple pathways and nodes, enabling comprehensive analysis of complex industrial material flows[29]. A demonstration exists in an integrated framework tracking material flows, environmental burdens, and industrial linkages. In their work, MFA-derived flow data constructed a PIOT that quantitatively mapped material interdependencies among all process nodes in regional building material systems, identifying 'demolition' as the key node driving material circulation[30]. Nevertheless, while MFA-IOA integration establishes macro-level associations between industrial chemicals and known emissions, it still cannot fully capture potential chemical transformations during industrial processes, limiting precise substance correlation.

To further capture and clarify potential chemical transformations during industrial processes, Molecular Scale Models (MSMs) provide a potential pathway to elucidate chemical transformations and establish precise linkages for industrial chemicals. In this model, all possible transformation pathways from reactants to products and by-products are predicted based on the structures of chemicals and known reaction rules[31]. Next, kinetic parameters, such as reaction activation energies, are determined using quantum chemical methods like density functional theory or by applying linear free energy relationships (LFER)[32,33]. These parameters are then used to identify the dominant reaction pathways. Finally, the integration of pathway and kinetic analysis enables the elucidation of chemical bond cleavage and reorganization mechanisms, as well as the identification of potential transformation products[34,35].

A critical limitation, however, is MSMs' reliance on idealized reaction conditions that fail to accurately predict outcomes under actual operating parameters[36]. Bridging this gap, mechanistic models, typified by the Intrinsic Kinetic Model, can utilize reaction pathways derived from MSMs as a foundation. They provide a quantitative description of how actual operating conditions, including temperature and pressure, affect reaction rates and product distributions using physical kinetics and mathematical formulations[37−39]. For instance, Chen et al. exemplifies this integration by connecting idealized pathway predictions with real process simulations[31]. They first utilized MSMs and constructed a hydrocarbon catalytic cracking network with 74 molecules and 469 reactions, revealing all decane/hexene co-conversion pathways. The dominant pathways were then identified using a modified LFER. Furthermore, by integrating the intrinsic kinetic model and introducing catalyst acidity (including Bronsted acid and Lewis acid) as a key parameter, they developed a hybrid model capable of simultaneously reflecting molecular conversion pathways and actual process conditions, which enabled the prediction of the effects of different acid catalysts on gasoline yield and composition[31]. This previous study demonstrated both the capability of molecular-scale models to deduce complex reaction pathways and their potential to bridge idealized pathway predictions with actual process simulations through integration with mechanistic models.

It should be noted that mechanistic models typically analyze isolated reaction units, whereas actual industrial production involves sequential/parallel reaction steps where inter-stage material losses impact overall yields[37]. Further integration with process simulation software (e.g., Aspen Plus, CHEMCAD) enables system-level simulation of complete industrial processes encompassing reaction, separation, and recycling units. This quantifies material flows and losses throughout production chains, clarifying comprehensive input-output relationships[40,41]. Tripodi et al. operationalized this for methanol production[42]. They embedded methanol synthesis kinetics into Aspen Plus' plug-flow reactor module, integrating separation, recycle, and other operations to simulate the complete process[42]. This configuration enabled precise quantification of concentrations and flows of CO/CO2/H2 reactants, CH3OH product, H2O by-product, and unreacted feedstocks across reactors, separators, and recycle streams.

Herein, we believe multi-model coupling provides a robust strategy to resolve industrial process 'black boxes', and establish systematic chemical-emission linkages (Fig. 1). Specifically, the hierarchical methodology is implemented as follows: First, integrating MFA and IOA enables the quantification of material flows and inter-node linkages at the macro level. Next, integrating MSMs reveals key chemical reaction pathways and potential transformation products. Furthermore, utilizing mechanistic models clarifies the quantitative reaction-scale relationships between reaction rates and actual process conditions. Finally, integrating with system-scale software allows the systematic simulation of industrial processes, thereby constructing a complete upstream industrial chemical metabolism network. This hierarchical methodology provides foundational support for linking process-level industrial chemical associations and life-cycle risk assessment.

-

Following industrial operations, chemical emissions are typically discharged into WWTPs. Extensive research demonstrates that WWTPs frequently fail to remove emerging organic contaminants, allowing persistent and poorly degradable compounds to enter the environment, thereby posing risks to human health and ecosystems[43,44]. Upon release, contaminants undergo transport and transformation across multiple environmental media[45], further intensifying challenges in linking downstream pollutants to upstream industrial sources[19]. To overcome these challenges, research should explicitly elucidate the environmental transport and transformation pathways of contaminants, enabling the establishment of robust life cycle material linkages that connect industrial emissions with downstream pollutants (Fig. 1).

Environmental transport

-

Currently, multimedia environmental models (MEMs) have been widely utilized to characterize chemical distribution and transport across environmental media and regions[46,47]. By integrating chemical physicochemical properties with environmental parameters, these models quantify partitioning, degradation, and diffusive/non-diffusive behaviors, serving as crucial tools for contaminant source identification and fate analysis[48]. Existing MEMs divide broadly into fugacity and non-fugacity models.

Fugacity models utilize the thermodynamic concept of fugacity to describe chemical migration tendencies between environmental compartments[49]. The foundational equilibrium criterion (EQC) model, derived from fugacity theory, simulates pollutant distribution among air, water, soil, and sediment, providing a simplified yet universal theoretical framework for understanding chemical transport[50]. Subsequently, various fugacity models have been developed and tailored to different spatial scales and applications[51].

At regional scales, the quantitative water-air-sediment interaction (QWASI) model targets lake/river environments[52]. Recognizing fugacity equilibrium limitations for low-vapor-pressure chemicals, Diamond et al. extended QWASI using an equivalent equilibrium criterion[53]. The multicompartment urban model (MUM) characterizes semi-volatile organic compound (SVOC) transport across urban compartments (air, soil, vegetation, surface water, sediment, impervious surface films). For global scales, the Berkeley-Trent (BETR) model incorporates GIS-derived hydrometeorological data to simulate interregional transport[53], requiring high-resolution climatic/geographic inputs that limit applicability in data-scarce regions. CliMoChem uses latitudinal zones with defined temperature gradients to capture thermal influences but excludes ice/snow compartments, impairing polar-region accuracy[53]. Fugacity models include biological modules simulating contaminant uptake/metabolism in organisms[54], and WWTP modules analyzing WWTPs' behavior[55].

Alternatively, non-fugacity models employ mass-transfer coefficients and chemical activity. SimpleBox uses concentration-based 'piston velocity' coefficients to assess neutral chemical transport globally and continentally[56]. The multimedia activity model for ionics (MAMI) introduces chemical activity, pH, and ionic strength to model ionizable compound dissociation and transport under variable acidity/salinity[57].

Building on these frameworks, the Sino Evaluative SimpleBox-MAMI (SESAMe) model incorporates China-specific parameters for regional multi-media transport simulation. However, its lack of directional advective exchange mechanisms between regional and continental scales prevent spatial pathway analysis[58]. Critically, fugacity models excel for neutral/SVOC transport, while non-fugacity approaches better accommodate ionic compounds.

Collectively, MEMs systematize post-release transport, spatial distribution, and equilibrium exposure, enabling quantitative links between industrial emissions and environmental contaminants for risk assessment. Given industrial emission diversity, including VOCs, SVOCs, heavy metals, and ionics, a single MEM is difficult to universally capture transport behaviors of various synthetic chemicals. Optimal model selection must therefore align with both emission properties and regional environmental characteristics to maximize predictive accuracy.

Environmental transformation

-

During environmental transport, contaminants undergo physical, chemical, and biological transformations, generating transformation products (TPs) with distinct structures and properties. This complexity impedes contaminant source tracing[59], and complicates pollution characterization due to TPs' diversity, and the frequent lack of reference standards[60]. Therefore, transformation models are applied to address these challenges by simulating pathways and predicting TPs to establish critical material linkages[17].

Existing environmental transformation models can be categorized into three types. The first biotransformation models employ reaction rules to predict chemical metabolites. The classic rule-based model EAWAG Biocatalysis/Biodegradation Database-Pathway Prediction System (EAWAG BBD-PPS) predicts TPs based on contaminant functional groups and a known reaction database, thereby ensuring strong interpretability[61]. However, rule-based systems are prone to combinatorial explosion during multi-step reaction prediction, resulting in an exponential increase in potential pathways[61]. This challenge is more severe for multi-substituted compounds, which exhibit high false positive outcomes. To overcome these limitations, the enviPath integrates a machine learning model that assigns a probability of occurrence to each potential reaction[62]. This framework employs Bayesian updating to evaluate multi-generation transformation pathways, thereby effectively pruning redundant routes, and reducing false positive rates by nearly an order of magnitude[63]. In addition, PathPred leverages Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enzymatic reaction templates but remains limited by database coverage[64]. The Biochemical Network Integrated Computational Explorer (BNICE) uses graph algorithms to predict novel pathways, yet its predictions requires expert validation in the absence of experimental confirmation[65].

The second category comprises biotic and abiotic transformations. Integrated biotic-abiotic models incorporate photolysis, hydrolysis, and reduction pathways. For instance, BioTransformer combines rule-based and machine learning approaches to predict transformations across eight categories (e.g., human metabolism, microbial degradation), directly linking outputs to validation databases like NORMAN Suspect List Exchange[66]. Furthermore, the EPA's Chemical Transformation Simulator integrates multiple reaction libraries, including PFAS-specific data, and ranks TPs by literature-derived transformation rates to prioritize dominant pathways[67]. Based upon reaction rules, Catalogic software incorporates a two-tier screening mechanism using probabilities and thresholds[68]. It adjusts reaction probabilities according to molecular fragments, reactive sites, and environmental parameters, and constrains major pathways using rate thresholds, improving the plausibility of predictions. These integrated models go beyond purely biotransformation models by not only covering more transformation types but also considering how environmental conditions affect pathway occurrence, thereby enhancing the environmental relevance of their predictions.

The third category is the integrated computational and experimental models, which combine predictions with empirical data to enhance the accuracy of transformation pathway identification. For instance, patRoon embeds transformation modules within high-resolution mass spectrometry workflows, matching predicted TPs against PubChem and NORMAN datasets for annotation/validation[69]. It bridges the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental validation. Together, transformation modeling has thus evolved from rule-based systems to integrated computational-experimental frameworks requiring further development. Future advances should incorporate multi-source experimental data, mechanistic insights, and unified validation protocols to enhance robustness.

Collectively, integrating industrial emission sources with environmental transport/transformation processes enables complete life cycle tracing of high-risk chemicals. These models collectively establish quantifiable linkages between industrial chemicals, their emissions, and resulting environmental contaminants, offering holistic insights into industrial chemical life cycles. Future progress will hinge on developing next-generation, interoperable modeling frameworks capable of dynamically coupling emission, transformation, and transport processes, ultimately delivering the life cycle-level elucidation required for chemical management.

-

Tracking chemical transport and transformation can determine the types and quantities of chemicals released into the environment, which serves as an essential basis for understanding environmental risks throughout the life cycle of industrial chemicals. However, from the effects perspective, since transient mixture risks arise from the co-occurrence of multiple chemical contaminants at each life cycle stage, effectively identifying cross-stage high-risk chemicals can ultimately define the cumulative life cycle risks of industrial chemicals. Consequently, efforts should additionally focus on systematically identifying high-risk substances and elucidating cumulative risks from diverse chemicals (including transformation products) across all life cycle stages, so as to pinpoint life cycle risk hotspots and clarify targeted management priorities. This process requires identifying key toxicants within transient mixture pollution to enable risk-directed life cycle chemical management.

Current identification of key toxicants in mixture pollution relies primarily on the toxic unit (TU) approach, which quantifies relative toxicity by dividing environmental concentrations by toxicity thresholds[70,71]. This method estimates toxic contributions and identifies high-impact toxicants[72]. However, it assumes all contaminants share similar mechanisms of action (MoA), neglecting potential MoA variations that may cause synergistic or antagonistic effects among co-occurring chemicals[73], thereby potentially underestimating or misjudging mixture toxicity and compromising risk assessment accuracy[74,75]. Consequently, elucidating pollutant toxicity pathways is critical for robust assessment of industrial chemical mixture pollution.

Advancing assessment through toxicity pathway frameworks

-

The adverse outcome pathway (AOP) conceptualizes causal chains from molecular initiating events (MIE) through key events (KEs) to adverse outcomes (AO), linking molecular interactions to toxicological effects[76]. For instance, Knapen et al.[77] integrated multiple AOPs involving fatty acid uptake, synthesis, oxidation, and efflux to construct an AOP network (AOPN) for hepatic steatosis, revealing how contaminants induce liver damage through distinct toxicity pathways. Nevertheless, unknown probabilities of AO occurrence across different pathways limit the quantitative applicability of AOPs in risk assessment[78,79].

Quantitative AOPs (qAOPs) overcome this limitation by integrating experimental data with statistical models (e.g., linear regression, Bayesian networks) to establish probabilistic relationships among KEs, and identify dominant toxicity pathways contributing to AO[80,81]. A demonstration exists in an AOPN initiated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (MIE) leading to Daphnia magna mortality (AO)[82]. Bayesian network modeling quantified individual AOPs within this network, identifying the dominant pathway: ROS overproduction causing oxidative DNA damage (KE9), DNA double-strand breaks (KE10), apoptosis (KE11), and ultimately organism death[82]. This quantitative approach established the mechanistic basis for key toxicant identification.

Event-driven framework for toxicant identification

-

Upon clarifying dominant toxicity pathways, the previously constructed event-driven taxonomy (EDT) methodology could potentially link pathways to bioassays by treating the latter as event drivers (EDs) that trigger risks[83]. By comparing contaminant concentrations against ED-specific toxicity thresholds, this framework quantifies risks and identifies high-risk toxicants. For instance, Cheng et al. analyzed more than 14,000 aquatic ecotoxicology publications and the AOP-Wiki database using natural language processing (NLP), and thus established linkages between toxicity pathways and bioassays, identifying the corresponding EDs and mapping their spatial distribution across China[83]. This study revealed nationwide ED distributions, identifying aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), and antioxidant response element (ARE) as dominant EDs in the Pearl River Delta. With these bioassays, regional risks were calculated by combining concentrations of contaminants with their toxicity thresholds, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were identified as the high-risk toxicants in the region. This EDT framework represents a paradigm shift that turns to mechanism-driven toxicity pathway elucidation and enables high-risk contaminant identification[84]. It should be noted that current limitations in AOP data coverage, particularly regarding contaminant interactions and pathway comprehensiveness, remain significant barriers to risk assessment of mixtures. Future efforts should expand toxicity pathway mechanisms through data integration to enhance AOP's applicability in risk evaluation for mixtures, thereby strengthening the scientific foundation for holistic risk assessment[83,85].

Since industrial chemicals generate transient risks at each life-cycle stage, by dynamically analyzing and aggregating these phase-specific risks, we can derive cumulative life cycle risk metrics to comprehensively reveal chemical risk profiles and provide integrated management insights (Fig. 1). First, combining AOPNs and qAOP for mixture contaminants under transient exposure to clarify toxicity pathway probabilities, enables quantification of transient composite pollution risks. Subsequent comparison of risk variations across stages elucidates industrial chemicals' dynamic behavior, identifying life cycle risk hotspots and key contaminants. Synthesizing these outcomes with material flows traces pollutants back to source chemicals, enabling life cycle risk control.

-

Industrial chemical life cycle risk encompasses the dynamic evolution of contaminants from initial synthesis through utilization to environmental fate. Despite persistent knowledge gaps across life cycle stages, this work establishes an integrated dual-flow framework that synchronizes material tracking with risk profiling to enable scientifically grounded life cycle governance of industrial chemicals (Fig. 1). Current limitations and tentative solutions for enabling life cycle management are systematically summarized in Table 1. Through material flow analysis, we suggest reconstructing chemical transfer pathways across production, use, and emission stages. This industrial metabolism network quantifies source-to-receptor relationships while enabling backward contamination tracing to specific chemical precursors. Complementarily, the risk flow perspective employs toxicity pathway analysis to: (1) quantify stage-specific instantaneous hazards; (2) identify mixture-critical toxicants; and (3) integrate cumulative risk trajectories across life cycle phases.

Table 1. Limitations, solutions, and challenges identified for enabling the life cycle management of industrial chemicals

Life cycle stage Current limitations Tentative solutions Remaining challenges Industrial metabolism • Complex industrial reactions and transformations obstruct linkage of source chemicals to terminal pollutants

• Models assume idealized conditions, ignoring operational variability• Multi-model integration to quantify material flows across sector transformations

• Coupling molecular-scale models with intrinsic kinetics and process simulation to resolve industrial 'black boxes'• Limited industrial reaction data causes prediction-reality discrepancies

• Validation challenges in cross-scale model integrationEnvironmental fate and transport • Coupled environmental transport/transformation impedes quantitative tracking of terminal pollutants

• Existing models treat transport and transformation as separate processes• Application-specific multimedia models to clarify chemical transport

• Apply transformation models integrating reaction rules, machine learning, and experimental data for environmental metabolites• No integrated frameworks for simultaneous transport-transformation modeling

• Limited joint assessment of dynamic environmental processesRisk of mixtures • Traditional key toxicant identification ignores contaminant interactions, failing to capture mixture effects • Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) network construction for toxicity pathway elucidation

• Quantitative AOP for key event relationships and dominant pathway probability

• Event-driven taxonomy (EDT) for high-risk toxicant identification• Limited AOP data (incomplete pathway coverage and lack of quantitative interaction data)

• Constrained cumulative risk evaluation for complex mixturesThe convergence of material and risk flows generates valuable insights into dynamic risk propagation mechanisms. By mapping toxicant pathways to source chemicals through established industrial-environmental linkages, this framework fundamentally transforms life cycle management, shifting from terminal mitigation to proactive prevention. It enables precision interventions at critical control points (e.g., process engineering or emission treatment) where strategic actions maximize risk reduction. Furthermore, this integrated paradigm redirects regulatory interventions upstream through sustainable feedstock transitions and a priori molecular design. Simultaneously, it facilitates a strategic transition from reactive measures to proactive prevention by dynamically tracking chemical fate and risks across technological, process, and ecological scales. Achieving this requires cross-sector collaboration among industrial ecology, green and environmental chemistry, ecotoxicology, and data science. We therefore urgently advocate establishing interdisciplinary frameworks featuring harmonized terminology and standardized research outputs to systematically enhance life cycle risk assessment and management.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Keshuo Zhang: study conception and design, writing − draft manuscript preparation; Xiaohan Ruan: data curation; Liyang Wan: data curation; Yucong Lu: data curation; Hao Wang: data curation; Fan Wu: study conception and design, writing − draft manuscript preparation; Huizhen Li: conceptualization; Jing You: study conception and design, writing − manuscript editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data used in this study are derived from public domain resources.

-

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42477284 and 42377270), and the Innovative Research Team of the Department of Education of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2020KCXTD005).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

-

Develop an 'emiss-ome'-based risk assessment framework for industrial chemicals, enabling dynamic characterization of chemical risks across the life cycle.

Couple industrial metabolism with environmental process models to quantitatively link upstream chemical sources with downstream environmental pollutants.

Integrate mixed-pollutant risks as a critical component to enhance the completeness and accuracy of life-cycle environmental risk assessment.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang K, Ruan X, Wan L, Lu Y, Wang H, et al. 2026. Life cycle risk assessment and management of industrial chemicals: synergizing material metabolism and risk flow by 'emiss-ome'. New Contaminants 2: e005 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0026-0001

Life cycle risk assessment and management of industrial chemicals: synergizing material metabolism and risk flow by 'emiss-ome'

- Received: 10 November 2025

- Revised: 24 December 2025

- Accepted: 06 January 2026

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: Industrial chemicals are released throughout their life cycle (from upstream production to downstream emission), causing pervasive pollution of new contaminants and posing substantial risks to ecosystems and human health. The complex transfer and transformation of these chemicals during industrial and environmental processes necessitate dynamic risk assessment approaches. However, current methodologies remain predominantly static and endpoint-oriented, emphasizing instantaneous risks after emission while overlooking pollutant formation dynamics across the chemical life cycle, particularly for chemicals with transformation potentials. This disconnection impedes effective contaminant source tracing, identification of high-risk mixture components, and evaluation of cumulative life cycle risks. Based on the concept of emiss-ome, we attempt to establish mechanistic linkages between industrial chemicals, and end-of-life pollutants. We demonstrate how industrial metabolism analysis, coupled with environmental fate and transport models, elucidates material flows across the chemical life cycle, establishing quantitative source-pollutant relationships. To identify key contaminants and address mixture toxicity, the application of adverse outcome pathway frameworks are examined to reveal dominant toxicity pathways, enabling identification of key toxicants, and risk evaluation of chemical mixtures. Ultimately, the integration of chemical metabolism and risk flow is expected to establish a novel framework to trace key toxicants back to their source chemicals and assess cumulative life cycle risks, facilitating a paradigm shift from terminal risk identification toward proactive life cycle risk assessment and management.