-

Aquatic ecosystems are critical components in maintaining ecological security and human health. Aquatic ecological risk assessment generally requires a comprehensive understanding of exposure and effect information, such as regional geographic characteristics, pollutant occurrence, migration, and transformation in the aquatic environment, exposure routes, toxicological endpoints, and modes of action. In the era of environmental big data, making full use of related knowledge is expected to efficiently identify and prioritize the primary risk-driven pollutants in the environment, and support scientific decision-making in aquatic risk management. Although much retrospective knowledge has been curated in various databases as structured data, for example, the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard[1], PubChemLite[2], and the Adverse Outcome Pathway Wiki[3], these databases are mainly associated with chemical and toxicological data. Little is available to index field-measured exposure and effect data in aquatic environments, such as reported concentrations in surface water in a given river, detected toxicity potencies in sediment samples, or mixture risks in aquatic environments of certain regions. These types of knowledge are often scattered and unstructured across multiple heterogeneous sources, such as scientific literature, monitoring reports, and policy documents[4]. In addition, this information is commonly characterized by highly specialized terminology, implicit entity relationships, and multimodal mixing. Developing technologies to extract such text data would supplement existing knowledge of ecological risks in real environments.

Natural language processing (NLP) is an important area in artificial intelligence (AI) applications that aims to build linguistic pipelines to understand, learn, and produce human language content[5]. Named entity recognition (NER), which regards the rule-based terms (like terminologies) as entities, is designed to extract key information from context[6]. Research on NER has been conducted to collect various information, including chemical names[7−9], and disease records[10,11]. Statistics on term frequency can provide descriptive insights, such as research interests, temporal trends, and the average of the observed values. Furthermore, explaining scientific data often relies on the explicit relationships between terms, for example, chemical reaction equations, genomes and phenotypes, and geographic coordinates of the maps, which require developing the relation extraction (RE) technique in NLP[12]. Currently, models used for NER and RE tasks are mostly deep learning models. These models are often designed with recurrent neural network (RNN) architectures, and further modified to use long short-term memory (LSTM), gated recurrent unit (GRU), or their bidirectional variants[13,14]. Through manual feature engineering and task-specific optimization, these deep learning models have shown strong performance in extracting lexicon-guided terms and linguistic relations, and in highlighting symbols from the literature[15,16].

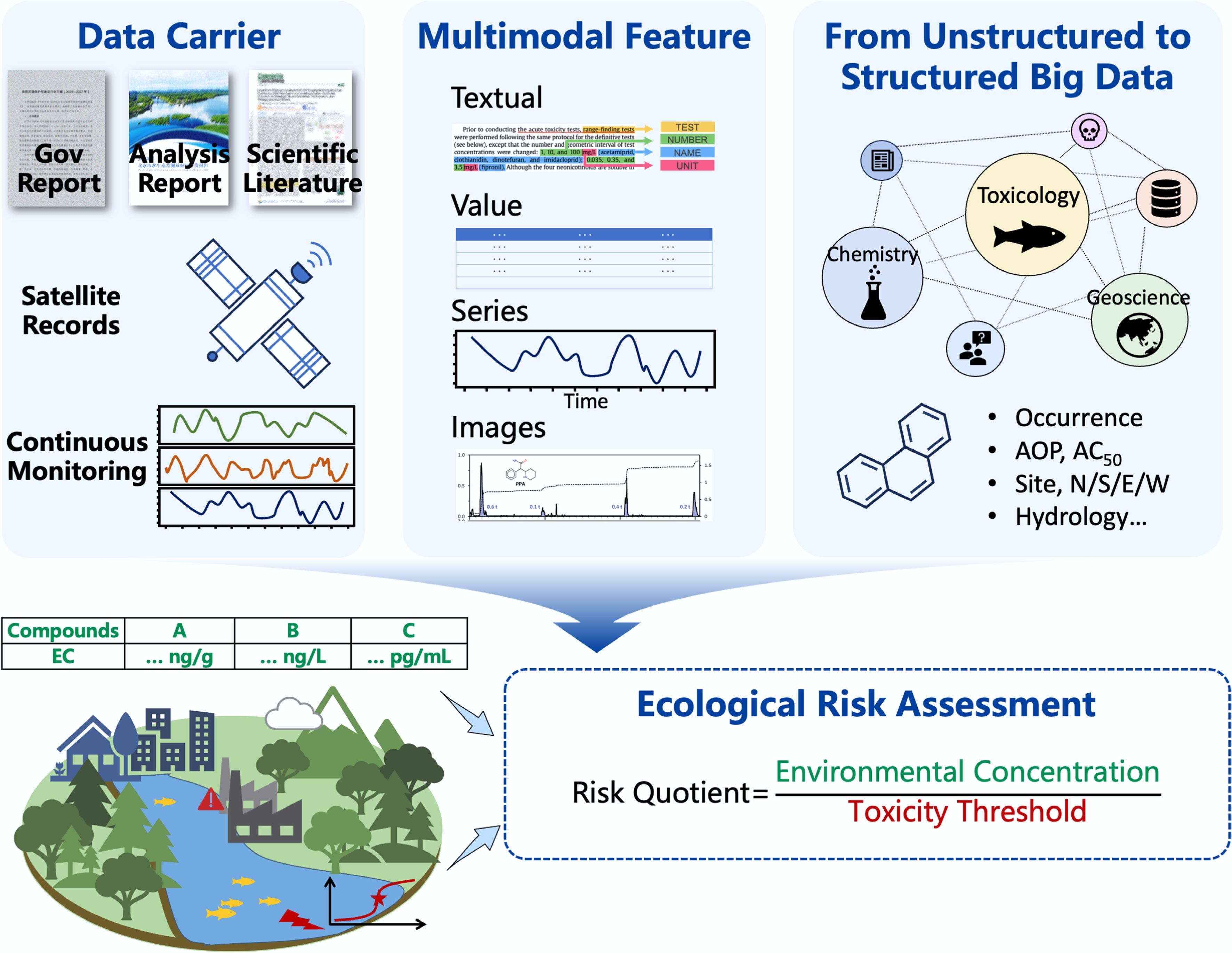

However, these traditional NLP methods generally relied on manual feature engineering and task-specific modeling, and performed poorly on information extraction (IE) tasks when the contexts involved complex terminology, implicit entity relationships, and multimodal data. As a consequence, there are three significant limitations of traditional NLP methods for processing unstructured data in environmental science, including poor generalization, high migration costs, and limited relation-extraction capabilities. In recent years, large language models (LLMs), based on the Transformer architecture, have demonstrated powerful capabilities for long-distance semantic understanding and context reasoning, offering a new framework for environmental IE tasks[17]. Notably, GPT-3.5 became publicly accessible in November 2022[18], and since then, there has been an explosion of publications on cutting-edge LLM applications across research fields. Beyond AI copilots, agents, and question-and-answer robots, LLM applications have greatly expanded the use of AI in science. With significant breakthroughs in NER, RE, and a new semantic generation (SG) function, LLMs are also anticipated to address the challenge of data fragmentation by integrating multi-source unstructured environmental data and to develop an end-to-end strategy for accomplishing NLP tasks in aquatic ecological risk assessments (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Potential use of large language models (LLMs) in aquatic ecological risk assessment. The LLMs are expected to transform unstructured multimodal environmental data into structured data and then serve aquatic ecological risk assessment.

The primary objective of this perspective is to clarify the potential of LLMs to mine, integrate, and reason over data from diverse sources for aquatic ecological risk assessment. The technical approaches of LLMs in NLP were systematically reviewed, and the current research status in aquatic risk IE was summarized, with particular attention given to advances in NER, RE, and SG tasks. Published studies on the application of LLMs in scientific research were systematically collected, and the information extraction capabilities of LLMs were examined. Current limitations, such as insufficient reasoning capabilities for multimodal data fusion and complex environmental challenges, were identified, and a prospective architecture for intelligent decision-making platforms were proposed. By integrating multi-disciplinary case studies and highlighting similarities in IE tasks across chemistry, toxicology, and earth science, this perspective evaluates the feasibility of mining aquatic ecological data using LLMs, and aims to provide environmental scientists and stakeholders with practical solutions for LLM-based data mining, thereby advancing the application of AI in aquatic risk assessments.

-

The goal of NLP is for computers to understand, process, and generate human natural language, thereby achieving human-computer interaction. As a core subfield of NLP, IE aims to automatically extract structured, valuable information (such as entities, relationships, and events) from massive, complex natural language texts that contain unstructured or semi-structured data, such as articles, academic papers, and social media posts. IE can identify and extract the information users need from massive information sources. This task requires identifying and extracting entities and their complex relationships, learning patterns, and predicting missing data in corpora. To accomplish the task, a typical IE workflow is performed in three steps: corpus preprocessing, feature engineering, and modeling and training.

The first step is corpus preprocessing. As shown in Fig. 2, this step includes tokenization, text normalization, NER, and RE. Tokenization is the premise for IE, and it is splitting the text into smaller but meaningful units called 'tokens', which are words or phrases with substantive connotations. Sometimes, depending on the entity naming rules and application scenarios, tokens can be further split into unary, binary, and ternary words. For instance, by splitting IUPAC-named compounds into ternary word dictionaries, the accuracy of compound recognition in scientific literature can be significantly improved[19].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of a workflow for ecological risk assessment (ERA) based on natural language processing (NLP). Left panel shows a workflow of NLP, which converts unstructured text into structured data through sequential stages, including Data Curation, Named Entity Recognition (NER), Relation Extraction (RE), and Semantic Generation (SG). Middle panel shows structured output content. Taking texts from a publication in the field of ERA as an example, this section illustrates the NLP corpus preprocessing step. Right panel presents a case in ERA to explain a proposed end-to-end process, in which an environmental risk assessment of emerging contaminants (e.g., neonicotinoids) in the Pearl River was conducted. Through data extraction and information correlation, aquatic risk baselines, including occurrence and toxicity features of these contaminants, were obtained. Subsequent risks were profiled in the region, ultimately leading to the prioritization of a high-risk inventory.

Text normalization is further applied to standardize tokens, reduce variability, and improve computational efficiency, including lowercasing, stemming, lemmatization, part-of-speech tagging (POS tagging), and stop-word removal. Stemming and lemmatization reduce words to their root forms by converting related or similar variants into their lemmas or stems. The POS tagging assigns a specific 'part-of-speech' label to each token in a text based on the token's grammatical function, meaning, and context within the sentence. Subsequently, these preprocessed words, in their root form, are used to construct corpora and word embeddings, allowing computers to understand the semantic connotations of natural language. The quality of the corpus will directly affect the performance of the model. In addition, assigning weights based on different word embedding vectors can make it easier to extract keywords.

The main tasks of IE include NER, RE, and event extraction (EE). NER detects entities and assigns them to predefined categories (such as compound names, modes of toxic action, and geographic locations), serving as the most basic and widely used IE subtask. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks[13], and gated RNNs[14] have been established as state-of-the-art approaches in sequence modeling, and have significantly improved the accuracy of entity recognition[20]. RE aims to identify the semantic relationships between two or more entities extracted in the NER step, and to transform isolated entities into meaningful pairs. Therefore, it is expected to identify contexts where compound names and toxicological terms co-occur, and to relate pollutant names to their environmental concentrations. EE is a more complex subtask that extracts structured information about specific events from the text and involves identifying event triggers and their associated arguments.

Semantic similarity calculation and text classification are important for these IE subtasks. Semantic similarity can be computed using cosine similarity applied to word embeddings, or through knowledge-based techniques such as WordNet, which can provide semantic distances between sentences. These approaches are commonly used in tasks such as text clustering and deduplication. On the other hand, text classification involves assigning documents to predefined categories. Traditional classification techniques, including Naive Bayes (NB), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and logistic regression, typically use bag-of-words or TF-IDF features to extract patterns from labeled data and predict categories for unseen texts. For example, an NB classifier incorporating adverse outcome pathways (AOP) has been developed to enhance the mechanistic interpretation of toxicity endpoints[21].

However, the aforementioned traditional machine learning models can handle only numerical vectors and require numerical inputs rather than raw text. Therefore, engineers need to manually define rules to convert text into structured features, a process known as feature engineering. Traditional NLP feature engineering is not a single step but a series of complex processes that require repeated trial-and-error, and are highly dependent on experience. In the field of environmental science, NER and RE have been used to extract structured information from heterogeneous multi-source data. The NER task relies on manually screened features (e.g., tokens, POS tags) for sequence labeling, whereas text classification often uses manually selected features, such as n-grams or TF-IDF, with classifiers such as SVMs. Both tasks are time-consuming and require continuous trial and error. The RE technique, dealing with deeper semantics, is even more challenging. In addition, these task-specific models with dedicated feature pipelines and annotated data suffer from poor cross-task and cross-lingual transferability, considerably limiting their adaptability and generalization. In contrast, LLMs present a promising alternative through end-to-end learning, long-context understanding, and vast parameter scales, potentially overcoming these long-standing limitations.

-

While promising, studies using LLMs in aquatic risk assessment are limited. A literature search in the Web of Science Core Collection's SCI-EXPANDED database (2000-present) using the keywords 'water', 'ecological risk', and 'large language models', limited to the research areas of Environmental Sciences and Ecology, yielded only four relevant publications, including one review article. These studies primarily focused on using LLMs to analyze ecological risk data related to the aquatic environment, such as policy documents[22,23], monitoring reports[24], and social media data[22], with the aim of developing more intelligent, dynamic risk assessment and management models.

Before the emergence of Transformers, RNNs and their variants, such as LSTMs and the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), were the mainstream models for handling sequential tasks. In environmental science, LSTM models have been combined with other models to address spatiotemporal problems, such as air quality prediction[25−27], precipitation estimation[28], and groundwater quality prediction[29]. Although RNNs' sequential computation makes it easy to process text, it prevents parallelization and limits their ability to model long-range context, resulting in a complex training process and lower computational efficiency[25,27].

While there have been improvements in RNN efficiency, the increased model complexity has hindered their practical application. For example, Srivastava & Kumar[20] optimized the air pollution prediction system by improving the activation function (Swish-Tanh), and introducing the Xavier Reptile search algorithm, which alleviated gradient issues in the traditional model to a certain extent, but it also increased the difficulty of model development and parameter tuning, limiting the transferability and application of the model.

The introduction of the Transformer architecture has effectively addressed the aforementioned bottlenecks of RNNs. Transformers can achieve parallel token processing and global context modeling, making Transformer-based LLMs more efficient for most NLP tasks[17]. Transformers adopts a split encoder-decoder architecture, with each component containing key sub-layers, such as multi-head self-attention layers, which can simultaneously focus on information from multiple positions, and feed-forward networks that perform non-linear transformations. Meanwhile, each sub-layer also combines residual connections and layer normalization techniques, enabling training to be more stable and effective.

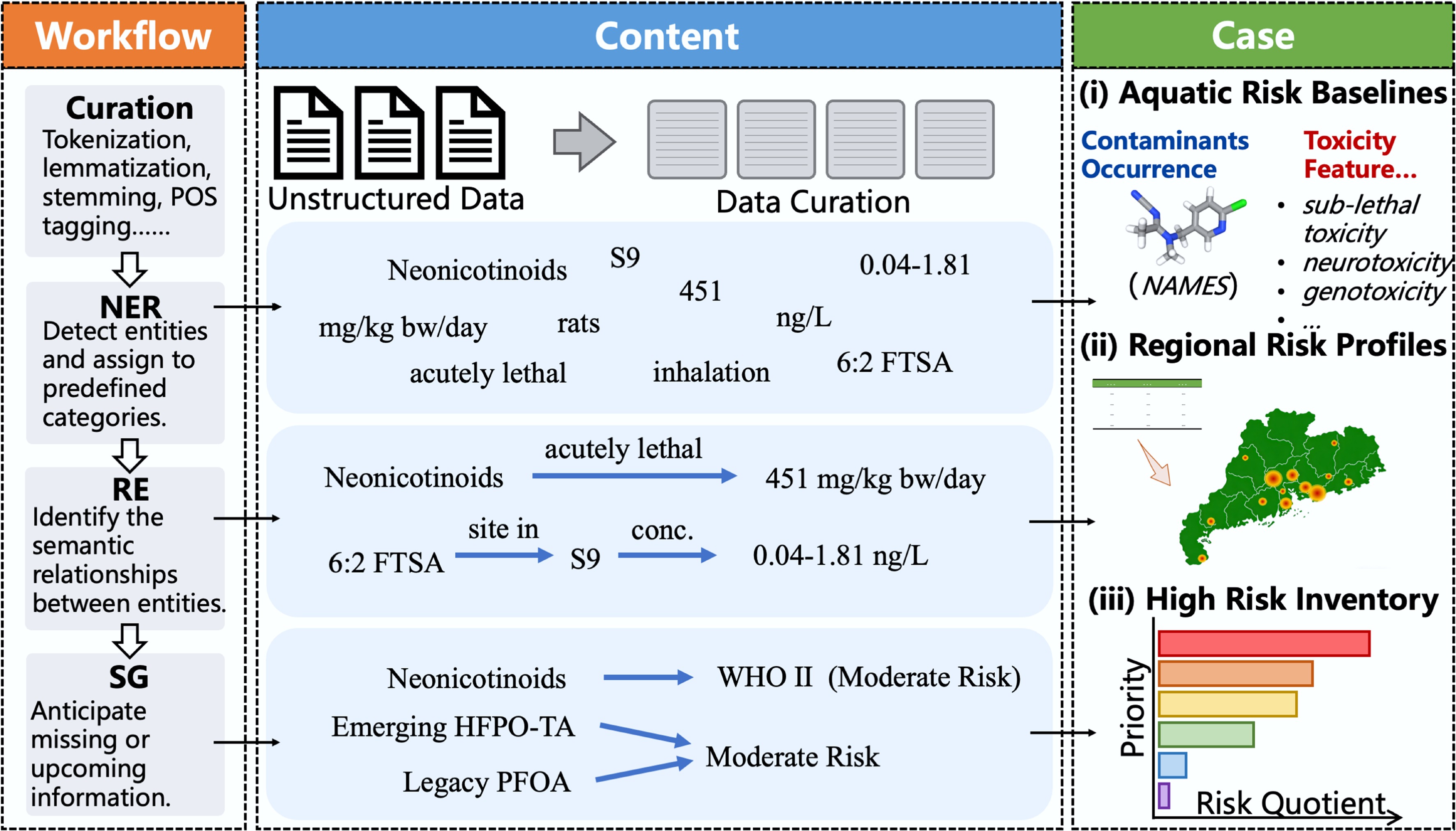

The core of Transformers is multi-head self-attention, which excels at capturing relationships between tokens and long-distance context dependencies, while positional encoding is used to retain their positions in the sequence. By replacing sequential recurrence in RNNs with parallelizable self-attention and feed-forward networks, Transformers drastically reduce training time, especially for long sequences. Landmark NLP models such as BERT[30] and GPT have been developed based on Transformers, which have extended context windows from hundreds, to hundreds of thousands of tokens, contributing substantially to progress in text understanding and generation. Furthermore, the extensive pre-training corpora and billions of parameters warrant LLMs with broad real-world knowledge (Fig. 3). This suggests a huge potential for LLMs to extract environmentally relevant information for aquatic risk assessment, and the related applications of LLMs are detailed in NER, RE, and SG below (Table 1).

Figure 3.

The architecture and optimized strategies of LLMs. Compared to original NLP methods, LLMs were trained on extensive corpora, feature parameter scales in the billions, and were capable of deep semantic understanding, multi-task handling, and long-context retention. To adapt LLMs to domain-specific tasks, three primary optimization techniques are commonly employed, including prompt engineering, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and fine-tuning.

Table 1. The applications and performance of large language models (LLMs) in data mining and information extraction tasks

Tasks Category Performance Ref. Oxidative stress inventory extraction NER Through optimization of prompt engineering on GPT-4, the values of 0.91, 0.81, and 0.86 were achieved for precision, recall, and F1 score, respectively. [9] Host-dopant extraction NER, RE Llama-2 (precision = 0.836, recall = 0.807, F1 = 0.821) outperforms MatBERT-Proximity (precision = 0.377, recall = 0.403, F1 = 0.390) in terms of overall performance. [8] Note information extraction NER, RE GENIE (F1 = 0.837, accuracy = 0.912) outperforms cTAKES (F1 = 0.182, accuracy = 0.748). [11] Object detection and waterbody extraction RE, SG WaterGPT achieves an accuracy of 0.96 on simple tasks and 0.90 on complex tasks. [24] MOFs prediction and generation SG The accuracy analysis reports 96.9% and 95.7% for the search and prediction tasks, respectively. [31] Expert-level question answering SG GPT-4 achieves a relevance of 0.644 and a factuality of 0.791. [36] Molecular property prediction SG In classification tasks within the field of physiology, the AUC-ROC improved from the previous state-of-the-art of 74.53% to 76.60%; in biophysics classification tasks, the average AUC-ROC reached 79.10; for regression tasks in physical chemistry, the average RMSE was 1.54; and in quantum mechanics tasks, the average MAE was 5.8233, representing a 48.2% improvement over the baseline. [39] Modeling complex toxicity pathways and predicting steroidogenesis SG In the classification task for target inhibitors, MolBART achieved an AUC above 0.85 and an F1 score over 0.7; in the task of predicting IC50 values, it attained an R2 over 0.7, with an MAE below 0.5 and an RMSE under 0.8. [40] Information extraction task 1: named entity extraction

-

The first step in extracting environmental information from unstructured text is NER, which identifies specific entities, and classifies them into predefined categories. Aquatic ecological risk assessment involves multi-disciplinary knowledge such as chemistry, toxicology, and hydrology. In this field, the entities to be identified typically include the types and sources of pollutants, their physicochemical properties, toxicity threshold data, and modes of toxic action. However, current NER tasks in this field face two significant challenges. Firstly, its interdisciplinary nature, and the complexity of terminology, significantly increase the difficulty of entity recognition. Secondly, the lack of a systematic taxonomic framework in toxicology makes it challenging to construct standard lexicons. Methods based on manual coding and large annotated datasets are often too complex and time-consuming, posing significant challenges for accomplishing the word segmentation task due to complex rules or insufficient labeled data. This issue is particularly pronounced when dealing with a chemical IUPAC name.

With their deep semantic understanding, LLMs can directly extract complex relationships among multiple entities, offering new solutions for entity extraction in challenging scenarios. In NER, LLMs have shown great potential for accurately identifying both complex and straightforward chemical entities. Liang et al.[9] extracted 17,780 records containing multi-dimensional information, such as chemicals, markers, and experimental conditions, from 7,166 documents in a single pass. Subsequently, they compiled a list of 1,416 pro-oxidants, and 1,102 antioxidants, supplementing these with data from chemical and pharmaceutical databases such as ChEMBL[9]. In another study, Dagdelen et al.[8] fine-tuned an LLM for material chemistry, and achieved accuracy and recall rates both exceeding 80% in NER tasks. The model successfully identified complex entities such as metal-organic frameworks using only 20 samples[8]. In addition, LLMs have demonstrated zero-shot entity recognition capabilities in materials science. For instance, ChatMOF can transform complex material entities into forms that LLMs can interpret, thereby intelligently aligning users' query intents with database records, facilitating accurate entity extraction without training for specific entities[31].

For the NER in the biological and toxicological field, Duan et al.[32] applied the protein language models to develop a standardized entity extraction pipeline and systematically identified 19 categories of protein-related entities, which covered multiple dimensions such as molecular function, taxonomic information, attribute descriptions, and formed the largest and most diverse protein entity dataset to date. Similarly, clinical text structuring tools like GENIE[11] (F1 = 0.837, accuracy = 0.912) are capable of accurately extracting medical entities along with their attributes (e.g., status, value, unit), and outputting the results in a structured format, outperforming traditional tools like cTAKES (F1 = 0.182, accuracy = 0.748) and MetaMap (F1 = 0.172) in IE tasks such as phrase extraction and assertion classification.

Collectively, these achievements indicate that LLMs not only possess strong domain transferability and adaptability in data-poor scenarios but also have the potential to accomplish environmental entity recognition tasks efficiently and accurately. This is expected to provide a reliable, scalable new approach to IE tasks in aquatic ecological risk assessment.

Information extraction task 2: relation extraction

-

To acquire environmentally relevant data for aquatic risk assessments, it is essential to associate pollutant entities with their quantitative attributes, rather than merely extracting entities. The second IE task is RE, which aims to identify semantic relationships between entities from unstructured text and construct structured knowledge. However, entity relationships in environmental literature are often characterized by sparse co-occurrence and implicit coupling, and these relationships are frequently distributed across multiple modalities such as text, tables, and figures. Traditional machine learning methods generally rely on manually designing features that transform text into structured vectors, and on extracting relationships based on lexical, syntactic, or semantic features. As a consequence, traditional machine learning methods struggle with extracting relationships from multimodal texts in the context of environmentally relevant data. Alternatively, advanced LLMs enable automated extraction of complex environmental relationships with their abilities of contextual reasoning and multimodal understanding.

For chemical RE, LLMs have demonstrated high accuracy, high efficiency, and strong generalization in a few-sample setting. Dagdelen et al.[8] used GPT-3 and Llama-2 with few-shot fine-tuning and human-AI collaborative annotation, and these LLMs enabled highly accurate and efficient extraction of complex relationships from scientific literature with only 100 to 500 samples. The F1 score of the host-dopant relationship extraction by Llama-2 reached 0.821, and the F1 score of the formula-application relationship extraction by GPT-3 was 0.537, and improved to 0.832 after manual correction. In the meantime, the annotation time was reduced by 57%, demonstrating a strong few-shot performance.

In the field of toxicology, AOP describes a typical multi-level chain relationship, i.e., molecular initiating event → key event → adverse outcome. For example, an AOP from 'protein alkylation' to 'liver fibrosis' (protein alkylation - cellular stress - release of inflammatory factors - recruitment and activation of hepatic stellate cells - excessive production of extracellular matrix proteins - accumulation of scar tissue and formation of fibrotic lesions - liver fibrosis) involves multiple intermediate key events. Such AOPs are characterized by sparse co-occurrence and implicit coupling across the literature. For instance, key events such as 'cellular stress', and 'release of pro-inflammatory cytokine' may be reported separately across studies. Their interconnections require inference based on additional toxicological mechanisms, such as 'cell damage triggering an immune response'. To address this challenge, Zhao used GPT-4 to automatically annotate and reconstruct five established AOPs in the AOPWiki. They found that the model-generated AOPs were consistent with the expert-validated versions in terms of event association and structural consistency[33], further validating LLMs' capability to extract complex multi-level implicit relationships.

Specialized hydrological LLMs like WaterGPT[24], designed for environmental multimodal data, outperformed general models like ChatGPT by a significant margin, with Dice and mIoU metrics exceeding 90% and maintaining data stability over a decade. In addition, using the constructed EvalWater evaluation dataset, the accuracy of RE by the WaterGPT reached 83.09%, which was 17.83% higher than that of the general model GPT-4. These results demonstrated significant advantages of the domain-adapted LLMs in terms of accuracy and stability.

Despite the great potential of LLMs for RE tasks, caution remains necessary due to the risk of unreliable associations in their outputs. This risk is particularly elevated when processing data from non-peer-reviewed literature sources such as preprints, where spurious relationships may be more likely to occur[34]. Therefore, the LLM-generated results should be validated against domain knowledge. Moreover, recent research indicates that domain-fine-tuned models usually excel at RE tasks compared to zero-shot and few-shot LLMs[35]. As a result, a hybrid strategy integrating domain adaptation with human-in-the-loop is proposed to be a key direction for future environmental relationship extraction.

Knowledge extraction task 3: semantic generation

-

Semantic generation is the process of anticipating missing or upcoming information based on available context. In the environmental field, such tasks often involve understanding and inferring the behaviors of complex environmental systems, for example, predicting future changes of water quality based on historical data, revealing pollutant dispersion patterns, or generating environmental policy recommendations. LLMs, with their deep semantic understanding, contextual reasoning, and multimodal integration offer a viable option for these applications.

Although general-purpose pre-trained LLMs, such as GPT-4 and Llama, have already learned general language rules from massive unlabeled corpora, their performance in environmental domains remains limited due to insufficient coverage of environmental knowledge, and relatively weak domain-generalization ability in environmental professional tasks. Under these circumstances, fine-tuning can adjust the model using labeled data to enhance semantic generation performance in environmental tasks[36]. Furthermore, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) technology combines information retrieval with LLM text generation, effectively mitigating hallucinations while enhancing transparency and trustworthiness. The combined use of fine-tuning and RAG enables LLMs to achieve performance close to that of domain experts in environmental semantic generation tasks.

In terms of chemical reasoning, LLMs have demonstrated remarkable potential to advance scientific discovery by conducting chemical research autonomously. AI agent systems, such as Coscientist[37], demonstrated (semi-)autonomous experimental design, planning, and multi-step execution by leveraging web search and code generation. The intelligent agent ChemCrow[38] has not only successfully automated the synthesis of target compounds such as DEET and thiourea-based organocatalysts, but also contributed to the discovery of new chromophores. Meanwhile, LLM4SD[39] is capable of automatically integrating knowledge in the field of chemistry and inferring new knowledge from prior knowledge. For example, using the extracted information that 'molecules under 500 Da are more likely to cross the blood-brain barrier', and SMILES codes, it can be inferred that 'molecules containing halogens are more likely to cross the blood-brain barrier'.

In terms of toxicological reasoning ability, Lane et al.[40] constructed a MoIBART model, and simultaneously predicted all steroid-related endpoints under sparse co-occurrence conditions, achieving an AUC above 0.85, and a F1 score over 0.7. In geoscience, after pre-training on extensive Earth system data, and fine-tuning for specific tasks, the Aurora Earth system model[41] can forecast a range of global phenomena, including global air pollution, ocean wave dynamics, tropical cyclone tracks, and climate change patterns. For biological reasoning, the ESM3 model[42] reasons over protein sequence, structure, and function and has simulated a novel fluorescent protein (esmGFP) at a distant evolutionary distance (58% identity) from known fluorescent proteins. This degree of difference is equivalent to simulating over 500 million years of natural evolution. Finally, MedTsLLM[43] provides insights into medical time-series analysis for aquatic ecological risk assessment.

Nevertheless, LLMs continue to face challenges in environmental SG tasks. As noted by Zhu et al., GPT-4 delivers inconsistent performance on expert-level questions, while fine-tuning strategies may result in overfitting and performance degradation[36]. Moving forward, future research should pay more attention to developing reasoning architectures tailored to domain-specific needs, such as the self-verification mechanism used in GeneAgent[44], coupled with the construction of high-quality environmental corpora, and the integration of human-in-the-loop strategies[42]. Collectively, LLMs, with their cross-modal integration, semantic reasoning, and automated decision-making capabilities, have great potential for applications in aquatic ecological risk assessment. By combining fine-tuning, RAG, multimodal modeling, and scientific reasoning mechanisms, LLMs can not only enhance the accuracy and interpretability of environmental semantic generation but also promote the discovery of new environmental pollutant patterns and the innovation of governance strategies.

-

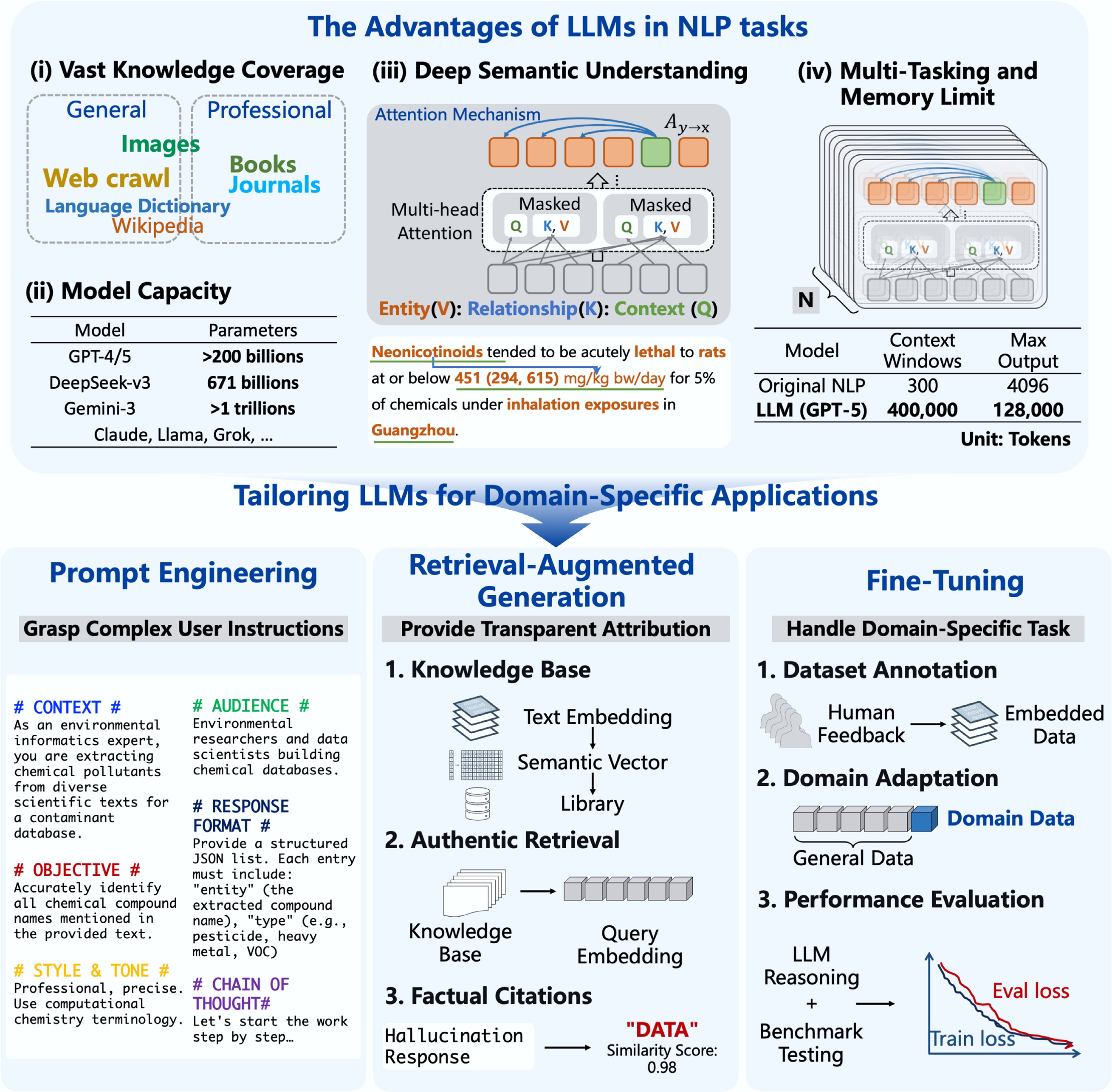

To date, LLMs are capable of understanding complex long texts, and improving accuracy in NER and RE tasks when combined with few-shot fine-tuning, as validated across multiple disciplines such as chemistry, biology, and earth science. At the same time, LLMs can analyze environmental data of multiple modalities simultaneously to extract comprehensive information. Furthermore, LLMs have demonstrated reasoning ability. For example, they can identify unreported quantitative structure-activity relationships in molecules, which can effectively advance knowledge discovery. To take this a step further, concatenating LLMs with different functions will create an AI agent that can automatically execute workflows, including file parsing, data analysis, and knowledge discovery (Fig. 4).

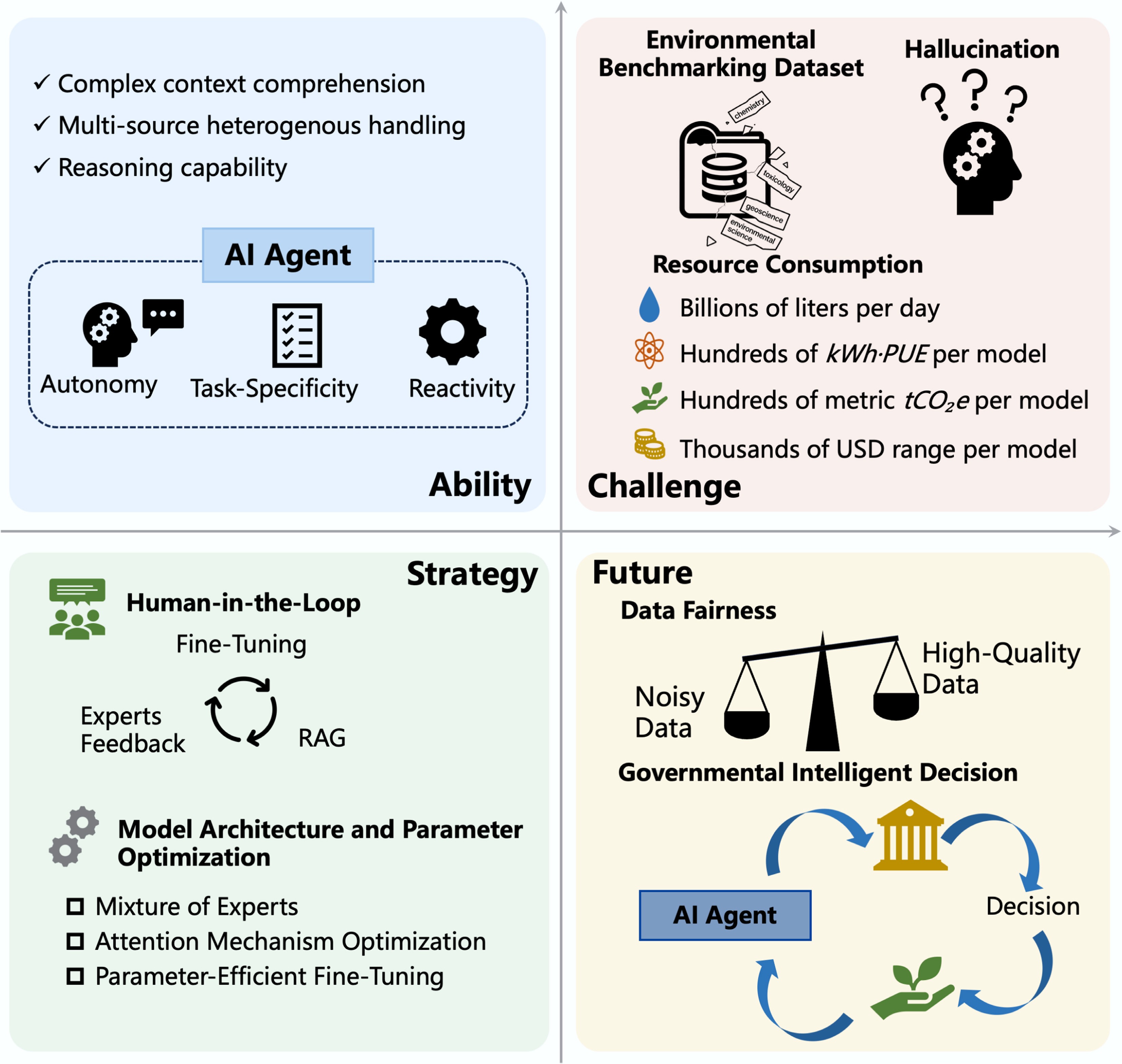

Figure 4.

The ability, challenge, strategy, and future of LLMs. AI agents enable the integration of multiple LLMs, thereby enhancing the level of task automation. LLMs still face challenges such as insufficient environmental data, hallucinations, and high resource consumption. Human-in-the-loop strategies can guide model learning and improve output reliability. Optimizing model architecture and parameters remains a conventional yet effective method for performance enhancement. In the future, greater attention should be directed toward improving data quality, ensuring data fairness, and leveraging AI agents to build intelligent systems that support governmental decision-making.

However, the applications of LLMs are still in their infancy, and numerous challenges await. Firstly, 'garbage in, garbage out'. Building reliable models requires the availability of high-quality datasets, which is a critical challenge in current LLM development. In aquatic risk assessment, the available databases generally lack comprehensiveness and a large scale. High-quality database construction relies on ample, high-quality, source-credible, and authentic textual resources, which require rigorous selection criteria defined by experts. Secondly, training and running state-of-the-art LLMs require significant computational power and electricity, raising environmental concerns, particularly regarding energy, water, and carbon consumption[45,46]. Training a model like BERT on a GPU incurs significant costs: 12,000 watts of energy, 1,400 pounds of CO2e, and up to USD

$\text{\$} $ Researchers have introduced the ChatEnv dataset and the EnvBench evaluation benchmark within the environmental domain. These resources encompass knowledge in five key areas: atmospheric environment, water environment, soil environment, biodiversity, and renewable energy. They have contributed to improving large language models' reasoning, analytical, and text-generation capabilities for environmental tasks[49]. Besides, to ensure the trustworthiness of LLM outputs in policy-making, interpretability, and fairness are essential. Attention, visualization, and causal reasoning could be used to enhance model transparency. Moreover, mitigating taxonomic biases in training data can distort risk predictions.

The application of LLMs to integrate global monitoring data, reports, and literature on pollutants, combined with embedded risk assessment models, can enable environmental scientists to maximize the utility of historical data and achieve a more accurate, systematic understanding of the risks associated with environmental pollutants. Integrating scientific knowledge with national policies may further minimize environmental risks. To address resource consumption, stakeholders should enhance the efficiency of large-scale model computation by optimizing utilization and adopting advanced cooling-water technologies.

-

Large language models (LLMs) represent significant advancements in data mining and knowledge discovery for aquatic ecological risk assessment. Compared with traditional natural language processing (NLP) models, LLMs achieve superior performance in entity recognition, relation extraction, and semantic generation. These capabilities allow LLMs to efficiently process heterogeneous, multi-source environmental data, reduce manual annotation costs, and improve adaptability in data-scarce contexts. Recent studies indicate that LLMs can extract complex terminology and reconstruct implicit relationships from literature in chemistry, toxicology, geoscience, and environmental science, thereby providing a transformative framework for integrating fragmented data in aquatic ecological risk assessment.

Despite these advancements, the application of LLMs in environmental science is still nascent and faces several challenges, including a lack of high-quality domain-specific corpora, inconsistent training data quality, hallucinations, and high computational demands. Future research should prioritize the development of robust environmental corpora and hybrid strategies that integrate fine-tuning, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and expert feedback to improve model accuracy and reliability. With systematic integration of aquatic ecological risk data, LLMs have the potential to become essential tools for scientific risk assessment and intelligent management, thereby providing a strong data foundation for ecological security and public health.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Qianhui Li: writing – original draft, investigation, visualization, formal analysis, data curation; Fei Cheng: writing – review & editing, visualization, validation, conceptualization, funding acquisition, formal analysis; Jing You: writing – review & editing, conceptualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were generated or analyzed in this study.

-

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (42577301, 42377270, and 42321003), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2025A1515010960), Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (2023B0303000007), and the Innovative Research Team of the Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2020KCXTD005).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li Q, Cheng F, You J. 2026. Large language models in aquatic risk assessment: research status and future perspectives. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 2: e007 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0026-0002

Large language models in aquatic risk assessment: research status and future perspectives

- Received: 30 October 2025

- Revised: 23 December 2025

- Accepted: 12 January 2026

- Published online: 04 February 2026

Abstract: As a crucial component for maintaining ecological security and human health, aquatic ecosystems are facing risks from intensified human activities. Aquatic risk assessment requires a comprehensive understanding of geographic distribution, exposure, and effects of diverse pollutants. In the era of big data, utilizing available environmental data to its fullest extent is expected to facilitate efficient regional risk assessment, and support informed decision-making in risk management. However, it faces a significant challenge in data integration, as environmental data are scattered across heterogeneous texts from diverse corpora, such as scientific research literature, monitoring reports, and policy documents. Natural language processing (NLP) approaches serve as key tools for structured information extraction (IE). Traditional NLP techniques face bottlenecks such as cumbersome feature engineering, and limited generalization, while newly developed large language models (LLMs) can perform a wide array of tasks through prompting, achieving remarkable generalization and versatility. The present work systematically reviewed cutting-edge applications of LLMs in IE tasks across multiple disciplines, including chemistry, biology, and toxicology, from three perspectives: entity extraction, relation extraction, and semantic generation. On the contrary, the current application of LLMs in environmental science is still in its early stages, facing challenges such as data dependence, hallucinations, and environmental concerns. Future research should focus on building high-quality environmental corpora and hybrid strategies to systematically integrate aquatic ecological risk data, and support environmental risk assessment and management policies.