-

Tetracyclines (TCs), a class of broad-spectrum antibiotics, have been extensively used in human medicine, animal husbandry, and aquaculture over the long term. A large proportion of TCs that are not metabolized by organisms enter the environment in their parent forms or as metabolites. This not only significantly disrupts the physiological activities of plants and animals, alters the structure and function of microbial communities, induces phytotoxic effects and abnormal carbon–nitrogen cycling, but also leads to the enrichment of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic-resistant genes in the environment[1]. Collectively, these consequences pose potential risks to the stability of ecosystems and human health[1]. Currently, TCs are frequently detected in urban wastewater treatment plants, with concentrations ranging from 186.8 to 786.2 μg·L−1[2]. Conventional filtration processes fail to achieve effective removal of TCs, resulting in their discharge into natural water bodies and further exacerbating water pollution. For instance, existing studies have detected TCs in surface waters across four to ten countries, with concentrations of tetracycline (TC) ranging from 1.4 to 260.0 ng·L−1, doxycycline (DC) from 1.8 to 74.0 ng·L−1, and oxytetracycline (OTC) from 6.9 to 1,292.0 ng·L−1[3]. In China, residual TCs with concentrations of 0.62–54 ng·L−1 have been detected in rivers within the Three Gorges Reservoir Basin[4]. Therefore, enhancing the removal efficiency of TCs from wastewater is of great significance for reducing the risk of human exposure to these antibiotics in the natural environment.

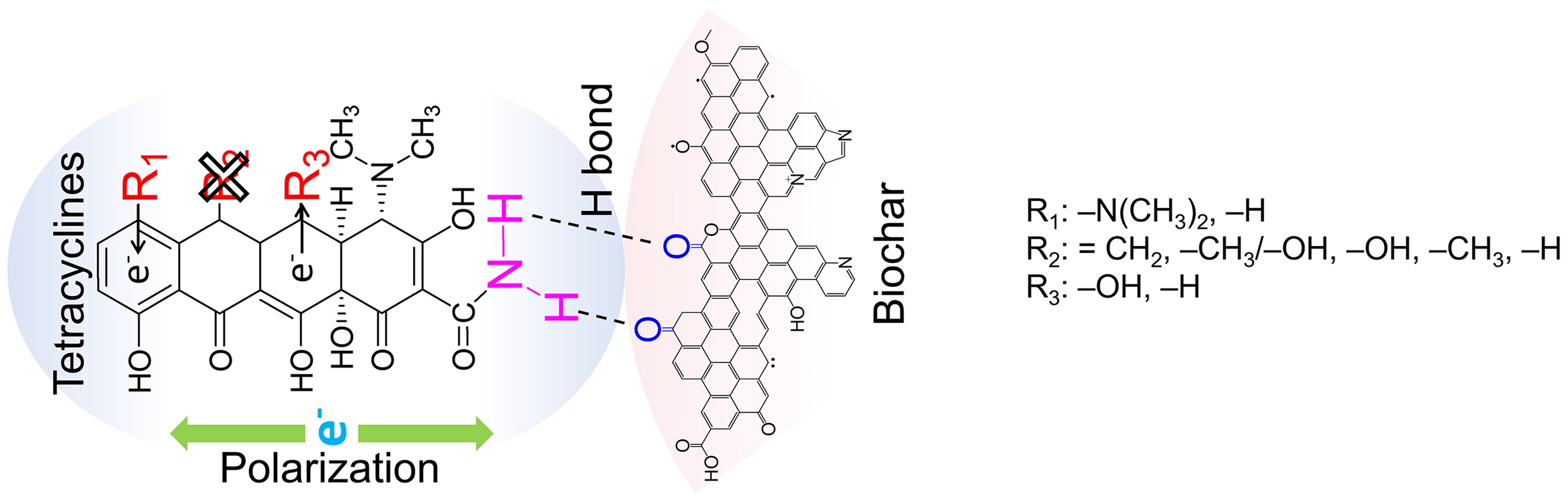

Over the past decade, extensive investigations have been conducted on the application of biochar for TCs removal from aqueous systems, and this approach has been proven to be technically feasible and effective[5−7]. Most studies have generalized the removal mechanisms by BC across all TCs congeners, e.g., electrostatic interaction, hydrogen bonding interaction, hydrophobic interaction, π–π electron donor-acceptor (EDA) interaction, and pore diffusion, ignoring that structural variations can drastically alter the reaction rate and interaction mode between TCs and biochar active sites[8]. The intrinsic molecular structure of TCs dictates their adsorption mechanisms onto biochar. As documented in prior investigations, the acid dissociation constant (pKa) of TC is a key determinant of its adsorption performance on solid adsorbents like biochar[6,9]. For example, phosphomolybdic acid-modified low-temperature sludge biochar (PMABC-200) exhibited remarkable TC adsorption capacity (~90% removal efficiency) at pH 3, 5, and 7, which stemmed from the attenuated electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged PMABC-200 and either neutral (pH 5 and 7) or protonated TC+ (pH 3)[6]. Conversely, at alkaline pH (9 and 11), both TC and PMABC-200 were negatively charged, and the resultant electrostatic repulsion suppressed TC adsorption, leading to a removal rate of less than 70%[6]. Hydrophobicity (Kow) also plays a pivotal role in TCs adsorption onto solid interfaces by mediating hydrogen bond formation[10]. Furthermore, electronic structure parameters such as frontier molecular orbital energies may regulate electron transfer processes and site-specific binding at polar sites between TCs and biochar[11]. However, a major limitation of current research lies in the lack of integrated analyses that correlate multi-faceted molecular structural parameters of TCs, encompassing acid–base equilibrium parameters, molecular polarity/interfacial interaction parameters, and electronic structure parameters, with their adsorption mechanisms on biochar. This critical shortcoming has severely hindered the rational optimization of biochar to enhance TCs removal efficiency in aqueous systems.

A variety of simulation and computational techniques are available to deepen the mechanistic understanding of interactions between TCs' molecular structures and biochar. Two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy of structural characterization data allows for unambiguous discrimination of the specific TCs' functional groups that engage with the biochar surface[12]. For example, 2D-FTIR correlation spectroscopy (2D-FTIR-CoS) was utilized to investigate humic acid adsorption onto TiO2 nanoparticles across varying pH conditions, identifying the carbonyl (C=O, encompassing carboxylate, amide, quinone, or ketone functionalities) and C−O moieties (including phenolic, aliphatic hydroxyl, and polysaccharide groups) of humic acid as the core binding sites responsible for its immobilization on TiO2 nanoparticles[12]. Quantum chemical computations can retrieve molecular structural parameters of TCs and biochar that remain inaccessible to conventional experimental techniques[13]. For example, density functional theory (DFT) calculations facilitate rapid quantification of critical electronic descriptors for TCs, such as the highest occupied (EHOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (ELUMO)[14]. Principal component analysis (PCA) enables the selective extraction of dominant principal components governing TCs' properties and environmental behaviors from redundant structural datasets[15]. When coupled with reaction rate constants derived from kinetic models (e.g., double-exponential model, DEM)[6,16] and incorporated into quantitative structure–property relationship frameworks[17], these components enable predictive modeling of adsorption behaviors for more TC congeners on biochar. Synergistic use of these methods will enable cross-scale correlation for TCs adsorption on biochar, drive the systematization and precision of pollutant adsorption mechanism research, and also furnish a rigorous roadmap for adsorbent design and tuning.

Herein, this study systematically explored the adsorption kinetics and structure-dependent mechanisms of five TC congeners in aqueous solution, including tetracycline (TC), oxytetracycline (OTC), doxycycline (DC), minocycline (MNC), and methacycline (MTC), on rice straw biochar pyrolyzed at 700 °C (BC700). The analysis method 2D-FTIR-COS was applied to elaborate structural alterations of TCs upon binding to biochar at various pH levels. The double-exponential model (DEM) was utilized to fit the adsorption rates k1 and k2 of five TCs towards BC700. By DFT calculation and literature retrieval, eight core molecular structure descriptors (like EHOMO and ELUMO, etc.), two dissociation constants (pKa1 and pKa2), and the octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow) of TCs were collected. PCA was used to extract dominant molecular structure descriptors regulating TCs properties, PC1, PC2, and PC3, enabling the identification of key structural factors and interaction mechanisms controlling TCs adsorption onto biochar. Ultimately, multiple linear regression (MLR) was applied to develop reliable predictive models that bridge the three structural principal components and TCs adsorption rate constants (k1 or k2). This study is intended to clarify the performance and mechanistic basis of biochar for aqueous TCs decontamination, furnishing scientific support for its engineering application in aquatic pollution control and providing a new paradigm for the high-value valorization of agricultural biomass waste.

-

Biochar was synthesized from dry rice straw sourced from Lianyungang, Jiangsu, China. The straw was pulverized, placed in a quartz boat, and pyrolyzed in a tube furnace (GSL-1100X-S, Kejing, Hefei) under a nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C·min−1, held at a temperature of 700 °C (BC700) for 180 min. The biochar product was, ground and passed through a 100-mesh sieve prior to use. BC700 had elemental contents of C 485.4 g·kg−1, H 13.1 g·kg−1, O 81.1 g·kg−1 and N 7.8 g·kg−1, with corresponding molar ratios of H/C = 0.32, O/C = 0.12 and (O + N)/C = 0.13[18].

The antibiotics used were tetracycline hydrochloride (TC), minocycline hydrochloride (MNC), doxycycline hydrochloride (DC), methacycline hydrochloride (MTC), and oxytetracycline hydrochloride (OTC) (all ≥ 98% purity, Macklin, Shanghai). Analytical-grade chemical reagents, including NaOH and HCl, were acquired from Lingfeng Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China). All experiments utilized ultrapure water (HYJD-I-40L/H, Yongjieda Purification, Hangzhou) with an electrical resistivity of 18.25 MΩ·cm−1.

Adsorption experiments

-

Batch adsorption experiments of TC on BC700 were carried out in 50 mL flasks. BC700 at a concentration of 4 g·L−1 was mixed with 25 mL TC solutions of initial concentrations 2 and 60 mg·L−1, respectively, followed by dark stirring at 25 °C and 150 r·min−1 for 24 h in a constant-temperature shaker (THZ-100, Yiheng, Shanghai, China) to reach adsorption equilibrium. After the reaction, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane, and the equilibrium TC concentration was quantified. Solution pH was adjusted to 3–9 using 1 mol·L−1 HCl or NaOH to assess the impacts of acid–base conditions on BC700 surface structure before and after TC interaction.

For the adsorption kinetics of all five TCs, 1.2 g of BC700 was dispensed into five 300 mL flasks, to which 250 mL of 60 mg·L−1 solutions of TC, MNC, DC, MTC, and OTC (pH adjusted to 7 with 1 mol·L−1 HCl/NaOH) were added separately. The flasks were placed in a shaker at (25 ± 1) °C and 150 r·min−1 with light excluded. Aliquots (10 mL) were sampled at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, filtered through 0.45 μm membranes, and TC concentrations were determined at 357 nm via a spectrophotometer (DR6000, Hach), with a calibration curve R2 ≥ 0.999. All experiments were conducted with at least two parallel replicates for reproducibility.

The Freundlich (Eq. [1]) model has been used to model TC adsorption processes on BC[16]:

$ \text{Freundlich:}\; \; Q_e=K_F\ \times\ C_e^{1/n} $ (1) where, Qe (mg·g−1) and Ce (mg·L−1) are equilibrium concentrations of an adsorbate on the carbon nanotubes and in the aqueous solution, respectively, KF (mg1−n·Ln·g−1) is the Freundlich affinity coefficient; n (unitless) is Freundlich linearity index.

The double-exponential model (DEM) (Eq. [2]) and n-order kinetic model (Eq. [3]) were employed to fit the adsorption kinetic data of TCs onto BC700[16]:

$ \text{DEM:}\; \; Q(t)=Q_e-a_1\ \times\ exp(-k_1\ \times\ t)-a_2\ \times\ exp(-k_2\ \times\ t) $ (2) $ \text{n-order kinetic model:}\; \; Q(t)=Q_e\ \times\ [1-(k_n\ \times\ t+1)^{\frac{1}{1-n}}] $ (3) where, Q(t) (mg·g−1) is the TCs adsorption capacity of BC700 at contact time t (h); k1 and k2 (h−1) are the rate constants corresponding to the fast and slow adsorption stages of the DEM, respectively; n is the adsorption reaction order, and kn ((mg·g)1−n·h−1) is the rate constant for n-order kinetic model; Qe (mg·g−1) refers to the equilibrium TCs adsorption capacity of BC700; and a1 and a2 are empirical constants.

Characterization, computation, and analyses

Specific surface area and pore size distribution

-

Approximately 200 mg of BC700 was weighed into a sample tube, which was then loaded into a specific surface area analyzer (ASAP 2020 Plus HD88, Micromeritics Instrument Corporation). Nitrogen (77 K) was used as the adsorbate gas to determine the specific surface area and pore size distribution of BC700.

2D-FTIR-CoS analysis of BC700-TC interactions

-

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Tensor 27, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to characterize changes in surface functional groups of BC700 following 0 and 24 h of interaction with 2 and 60 mg·L−1 of TC solutions across pH values ranging from 3–9. The acquired FTIR datasets were processed via the 2D-correlation spectroscopy analysis application (v. 1.20) integrated in Origin 2025 to generate synchronous and asynchronous spectra, which were subsequently employed to investigate structural variations of BC700 with pH.

Quantum computation of TCs' molecular descriptors

-

Gaussian 09 software was utilized to optimize the molecular structures of the five TCs at the RB3LYP/6-31G(d) level, ensuring that all optimized structures corresponded to the lowest-energy conformations on the potential energy surface. Key quantum chemical parameters, including the highest occupied molecular orbital energy (EHOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (ELUMO), polarizability (α), and dipole moment (μ), were calculated. A total of eight quantum chemical descriptors were derived from these computations, encompassing EHOMO, ELUMO, α, μ, the frontier orbital energy gap (ΔELUMO−HOMO), and the sum of squared EHOMO and ELUMO values for substituent (R1, R2, R3)-linked carbon atoms (

${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}3} $ Principal component analysis (PCA) and multiple linear regression (MLR)

-

The principal component analysis application (v. 1.50) in Origin 2025 was applied to analyze the TCs molecular structure datasets. The extracted principal components (PC1, PC2, PC3) were then subjected to the analysis-fitting-MLR function embedded in Origin 2025 against the rate constants (k1 and k2) derived from DEM fitting. This analysis was conducted to establish the correlation between TCs molecular structural features and their adsorption affinity toward BC700, as well as to identify the structural traits that facilitate favorable adsorption.

-

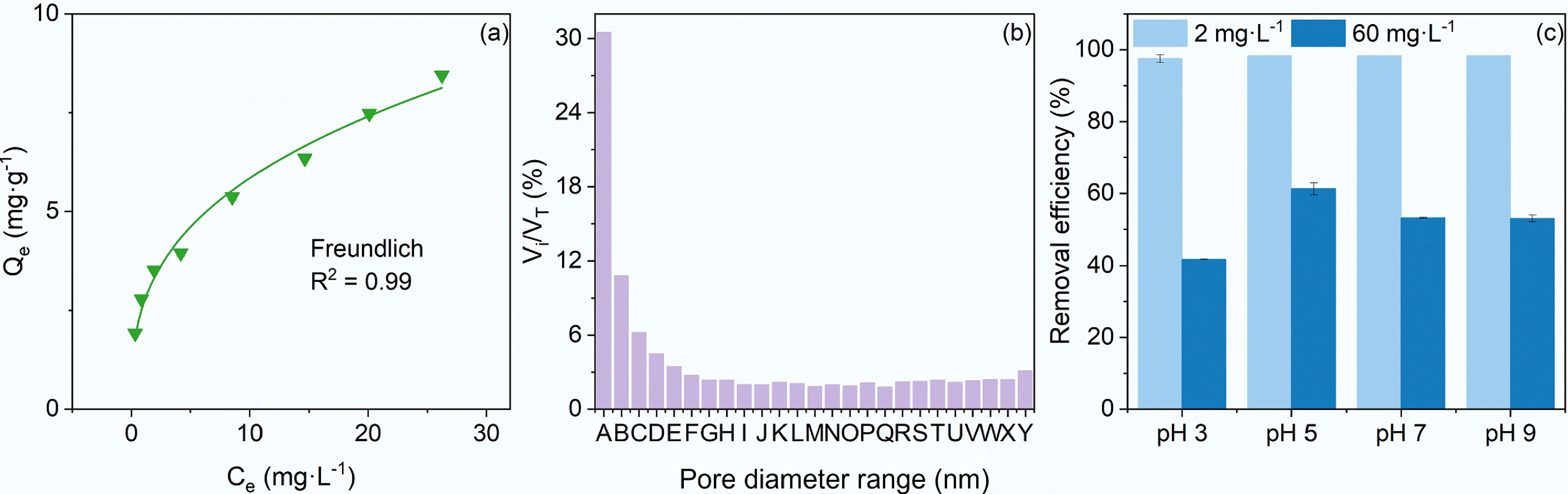

Adsorption isotherm of TC with an initial concentration of 2–60 mg·L−1 on 4 g·L−1 BC700 was fitted using the Freundlich model (Fig. 1a). The correlation coefficients R2 achieved 0.99, indicating that the selective binding of TC to specific sites on the BC700 surface promoted its adsorption, which were far from saturation, so that competitive adsorption between TC molecules remained negligible[16]. Reported selective binding mechanisms for TC adsorption onto carbon materials include π–π interactions, pore filling, and hydrogen bonding[6]. π–π interactions refer to attractive forces arising from the overlapping of π-electron clouds when two or more aromatic rings are in close contact[19]. For instance, π–π interactions dominate TC adsorption onto carbon materials with high graphitization like graphite or carbon nanotubes, which typically exhibit extremely high graphitized carbon contents (> 99.999%) and lack surface functional groups[19]. In contrast, BC700 used in this study featured relatively low aromaticity (H/C ratio = 0.32) and abundant oxygen-containing functional groups (OFGs) (data from a previously published study[18]). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterization[18] further revealed that BC700 had a high content of carbonyl/quinone C=O groups. Thus, π–π interactions should not play a dominant role in TC adsorption onto the biochars, especially BC700 investigated herein. Analysis of the pore size distribution of BC700 showed that pores with diameters ranging from 51.4 to 313.8 nm (average diameter 57.6 nm) accounted for 30.5% of the total pore volume, while pores larger than 2.0 nm contributed to 94.5% of the total pore volume (Fig. 1b). This indicated that BC700 was dominated by macropores and mesopores. Combined with its moderate specific surface area (75.82 m2·g−1), these results suggested that TC adsorption onto BC700 was dominated by surface adsorption rather than pore filling.

Figure 1.

The adsorption of TC on biochar and the physical characterization of biochar. (a) Adsorption isotherms of TC on 4 g·L−1 BC700. (b) The pore size distribution of BC700, and A−Y are specific pore diameter ranges (nm), respectively: 313.8–51.4, 51.4–27.8, 27.8–19.2, 19.2–14.7, 14.7–11.9, 11.9–9.9, 9.9–8.5, 8.5–7.5, 7.5–6.6, 6.6–5.9, 5.9–5.4, 5.4–4.9, 4.9–4.5, 4.5–4.1, 4.1–3.8, 3.8–3.5, 3.5–3.2, 3.2–3.0, 3.0–2.8, 2.8–2.6, 2.6–2.4, 2.4–2.2, 2.2–2.0, 2.0–1.8, 1.8–1.7. Vi is the incremental pore volume (cm3·g−1) for each pore with different diameter range, and VT is the total pore volume (cm3·g−1) for all pores. (c) Removal efficiency of TC with an initial concentration 2 and 60 mg·L−1 after its interaction with BC700 for 24 h at pH 3–9.

Collectively, the most plausible adsorption mechanism of TC onto biochars, particularly BC700, is hydrogen bonding formation, with pH serving as the key factor governing the protonation or deprotonation of the oxygen- and nitrogen-containing moieties in TC molecules[9]. As indicated earlier, TC at initial concentrations of 2–60 mg·L−1 was far from fully occupying the adsorption sites on 4 g·L−1 BC700. Even so, considerable differences were observed in the adsorption removal efficiencies between the 2 and 60 mg·L−1 TC systems, with each also exhibiting distinct performance across varying pH conditions (Fig. 1c). For instance, following a 24 h reaction at 25 °C, BC700 exhibited exceptional adsorption performance toward 2 mg·L−1 TC, achieving a removal efficiency exceeding 97.5% ± 1.1% over the entire pH range of 3−9. In contrast, the adsorption efficiency of BC700 for 60 mg·L−1 TC showed a distinct pH dependence: the removal efficiency peaked at 61.3% ± 1.6% at pH 5, decreased to approximately 53% at pH 7 and 9, and reached the minimum of 41.7% ± 1.1% at pH 3. Given the significant discrepancy in adsorption efficiency between low and high TC concentrations, the surface structural changes arising from the interaction between BC700 and TC at initial concentrations of 2 and 60 mg·L−1 were subsequently characterized to verify whether hydrogen bonding dominated the interaction mechanism across the broad range of initial TC concentrations.

pH-dependent variations of N- and O-containing groups on biochar with TC interaction

-

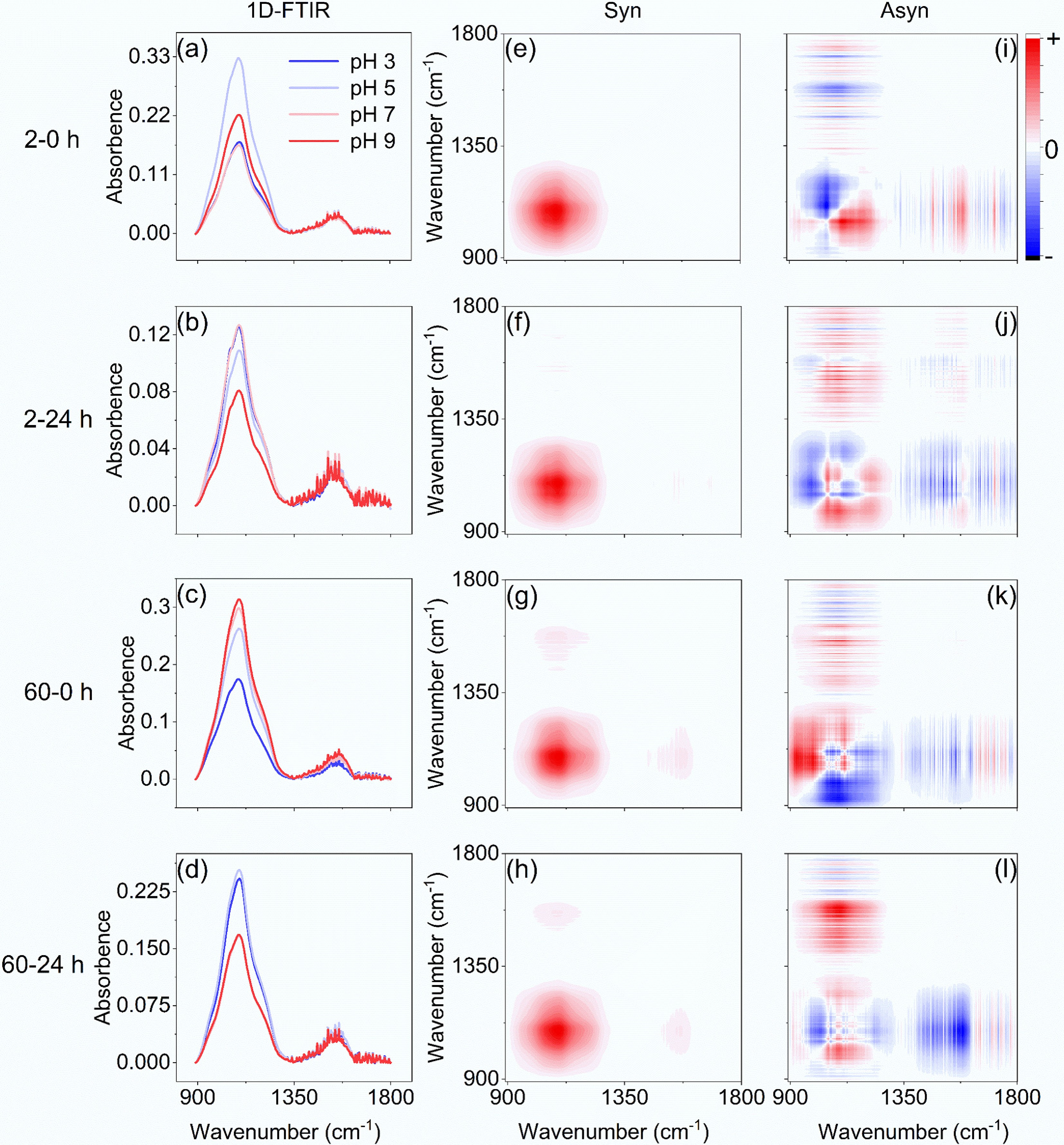

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to characterize variations in nitrogen- and oxygen-containing functional groups on BC700 before (0 h) and after (24 h) TC adsorption (Fig. 2). One-dimensional FTIR spectra (Fig. 2a, b) revealed that for the 2 mg·L−1 TC system, no obvious increases in the amide I band (C=O, 1,679 cm−1) and amide II band (N–H, 1,559 cm−1)[20] were observed after 24 h of interaction. This phenomenon could be attributed to the low TC concentration, whose characteristic signals were masked by the intrinsic nitrogen species of BC700 with an N content of 7.8 g·kg−1 (data from a previously published study[18]). For the 60 mg·L−1 TC system (Fig. 2c, d), a comparison of amide I and amide II peak intensity differences between pre- and post-adsorption on BC700 at the same pH level revealed that both peaks increased across all pH conditions, with larger increments under weakly acidic conditions and smaller ones under neutral-to-alkaline conditions. For example, the intensities of the amide I and amide II bands increased by 14.7%–43.4% and 14.3%–28.5%, respectively, at pH 3 and 5; at pH 7, the amide I band intensity rose by 23.8% while the amide II band showed negligible growth; and at pH 9, only the amide I band exhibited a 7% increase. These experimental results confirm that TC was indeed adsorbed onto BC700, and the pH of the aqueous solution exerted a strong regulatory effect on the TC adsorption process by BC700. Collectively, these FTIR results confirm the successful adsorption of TC onto BC700 and highlight that aqueous solution pH strongly regulates the adsorption process, with the extent of amide band enhancement that reflects TC-BC700 interactions varying significantly with pH due to differences in TC speciation and BC700 surface properties under acidic (pH 3 and 5), neutral (pH 7), and alkaline (pH 9) conditions.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of BC700 before and after its interaction with TC. (a)–(d) 1D-FTIR spectra of BC700 after adsorption of 2 and 60 mg·L−1 TC at pH 3–9 for 0 and 24 h. (e)–(h) Synchronous, and (i)–(l) asynchronous 2DCoS maps of 1D-FTIR for TC adsorption on BC700.

The analysis method 2D-FTIR-CoS was further employed to analyze the synergistic variation trends and sequential order of nitrogen- and oxygen-containing functional groups on BC700 with various pH levels. The results indicated that for 2 mg·L−1 TC and BC700 at 0 h (Fig. 2e, i), with increasing pH, the peaks at 1,559 cm−1 (amide II) and 1,707 cm−1 (C=O of –COOH)[21] exhibited changes prior to that at 1,110 cm−1 (C–O–C)[21], while the peaks at 1,608 cm−1 (C=O of ketone)[21], and 1,738 cm−1 (C=O of ester group, O–C=O)[22] changed subsequently; these functional groups showed consistent trends of increase or decrease. In contrast, the peak at 1,679 cm−1 (amide I) changed prior to C–O–C but displayed an opposite variation trend to C–O–C. After the 24 h reaction between 2 mg·L−1 TC and BC700 (Fig. 2f, j), with rising pH, the peaks at 1,556 cm−1 (amide II), 1,523 cm−1 (aromatic C=C)[21], and 1,679 cm−1 (amide I) changed later than the 1,110 cm−1 (C–O–C) peak and shared identical variation trends. Meanwhile, the peaks at 1,370 cm−1 (phenolic –OH)[21], 1,446 cm−1 (–CH3)[21], and 1,631 cm−1 (C=O of carbonyl)[21] altered prior to C–O–C, and the 1,710 cm−1 peak (C=O of –COOH) changed subsequently, all of which exhibited opposite trends to C–O–C. These observations demonstrated that at 0 h, the order of variation for nitrogen- and oxygen-containing moieties was amide groups/C=O of –COOH > C–O–C > C=O of ketone/C=O of O–C=O. The increase in the amide I (C=O) signal with pH elevation (pH 5–7) at 0 h implied an enrichment of –NH2 groups linked to C=O moieties on BC700; that is, the C=O sites on BC700 bonded to –NH2 groups was converted to an amide-like structure, so that the original C=O of carbonyl or COOH on BC700 became less. This indicated that a small amount of TC had already adhered to BC700 but had not reached adsorption equilibrium at 0 h. After 24 h of reaction, the decrease in C–O–C groups along with the reductions in amide II, aromatic C=C, and amide I groups, coupled with the increases in phenolic –OH, –CH3, carbonyl C=O, and –COOH C=O groups with rising pH, suggested that more C=O groups were released under high pH levels and that amide groups were not stably adsorbed on BC700. The above results reveal that prior to adsorption (0 h), as pH increases from 3 to 7, TC adheres to BC700 primarily via hydrogen bonding between the amide –NH2 groups of TC and C=O moieties of BC700. Specifically, amide groups preferentially form hydrogen bonds with C=O in carboxyl –COOH, followed by those in ketone C=O/ester O–C=O. However, when pH further rises from 7 to 9, these hydrogen bonds dissociate. After adsorption equilibrium (24 h), as pH increases from 3 to 9, the release of C=O moieties from carbonyl and carboxyl –COOH occurs without a distinct sequential order.

Prior to the reaction (0 h), for 60 mg·L−1 TC and BC700 (Fig. 2g, k), as pH increased from 3 to 9, in comparison with the 1,110 cm−1 band (C–O–C), the peaks at 1,384 cm−1 (phenolic –OH), 1,443 cm−1 (–CH3), and 1,512 cm−1 (aromatic C=C) exhibited delayed changes with consistent trends of increase or decrease. In contrast, the 1,556 cm−1 (amide II) and 1,652 cm−1 (amide I) peaks changed prior to C–O–C, followed by the 1,705 cm−1 (C=O of –COOH) and 1,735 cm−1 (C=O of O–C=O) peaks, all of which showed opposite variation trends to C–O–C. With rising pH, the abundance of C–O–C, phenolic –OH, –CH3, and aromatic C=C groups increased, while that of amide II, amide I, C=O of –COOH, and C=O of O–C=O decreased; notably, amide groups decreased prior to C=O of COOH, and ester groups. The decrease of C=O at 0 h under various pH levels showed that, despite the fact that high pH was unfavorable for TC adsorption, TC could still form hydrogen bonds with C=O groups on BC700. After 24 h of reaction (Fig. 2h, l), as pH increased from 3 to 9, relative to the 1,110 cm−1 (C–O–C) band, the peaks at 1,638 cm–1 (C=O of carbonyl), 1,648 cm−1 (amide I), and 1,710 cm−1 (C=O of –COOH) changed earlier, while the 1,441 cm−1 (–CH3) peak showed delayed changes, and all these groups displayed consistent variation trends with C–O–C. At 24 h, all nitrogen- and oxygen-containing functional groups exhibited a decrease in abundance, indicating that TC adsorption onto BC700 primarily occurred via interactions between –NH2 and C=O groups. The oxygen content of BC700 is tenfold higher than its nitrogen content, and the FTIR spectrum of pristine BC700 confirmed the presence of abundant surface C=O moieties but few –NH2 groups (data from a previously published study[18]). Therefore, hydrogen bonding is deemed the predominant interfacial interaction, preferentially forming between TC-containing –NH2 groups and BC700-borne C=O sites, which is further corroborated by the O–H stretching vibration peak shifted from 3,445 to 3,450 cm−1 and from 3,438 to 3,448 cm−1 for 2 and 60 mg·L−1 of TC before and after reaction, respectively[6]. For relatively high TC concentrations, hydrogen bonds between amide groups and C=O moieties still form with increasing pH. However, the sequential order of interaction between C=O-containing groups and amides is indistinct. This is likely attributed to the high TC concentration, which leads to extensive contact with C=O sites and reduced binding selectivity.

Adsorption kinetics of five TCs

-

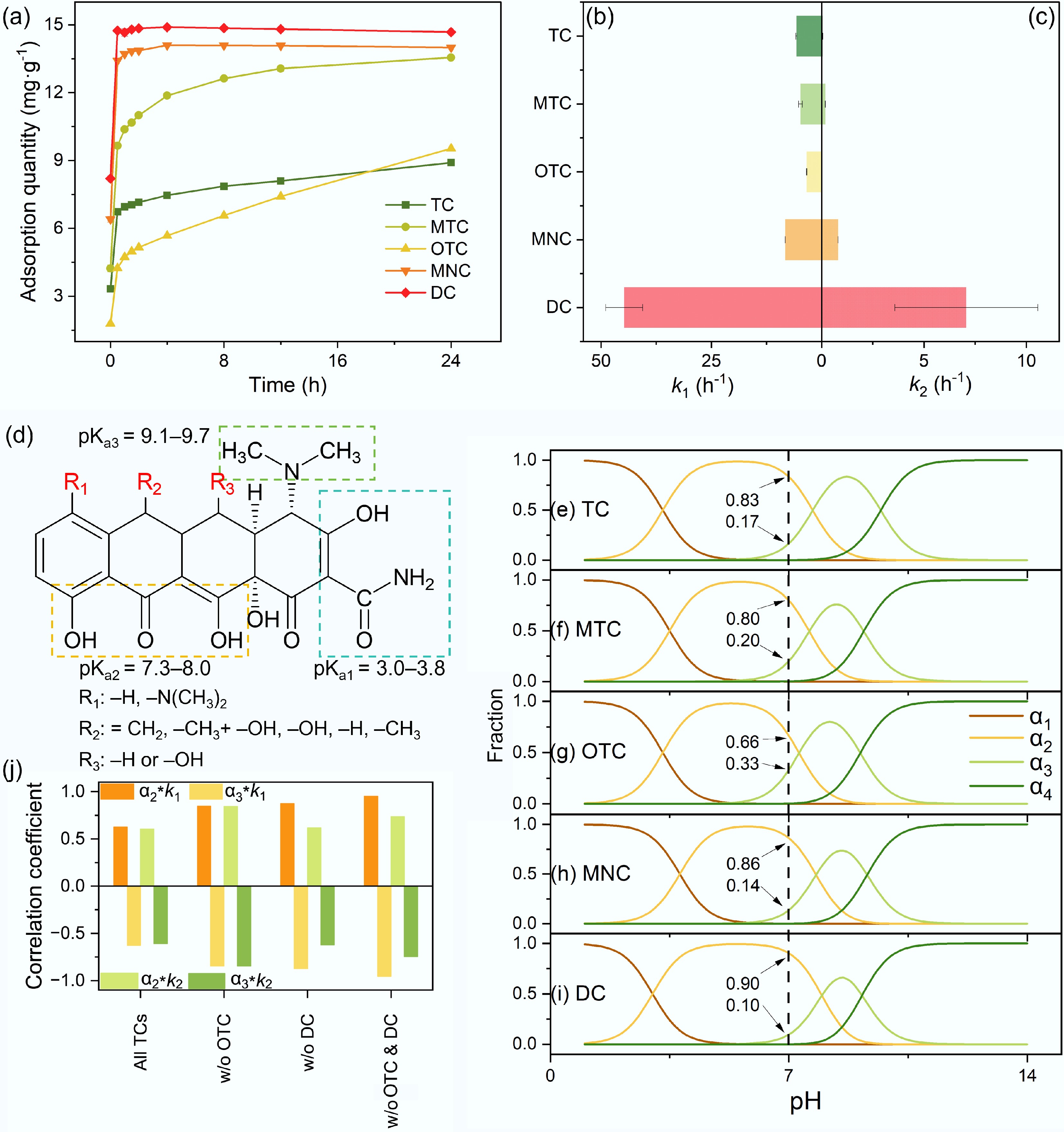

At pH 7 and 25 °C, following a 24 h equilibration, 4 g·L−1 BC700 displayed divergent removal performances for five TCs congeners with an initial concentration of 60 mg·L−1 (Fig. 3a). Specifically, the 24 h removal efficiencies of TC, MTC, OTC, MNC and DC were 47.8% ± 0.3%, 86.6% ± 0.3%, 58.6% ± 0.2%, 88.3% ± 0.3% and 95.3% ± 0.2%, respectively, highlighting the structure-dependent affinity of TCs congeners toward BC700. The adsorption kinetics of TCs on the BC700 surface were fitted using the n-order kinetic model, yet the fitting failed to converge. Double-exponential model (DEM) fitting of adsorption kinetics data yielded high correlation coefficients (R2 = 0.9991–0.9999), confirming that all TCs adsorption onto BC700 universally involved a fast (Fig. 3b) and a slow (Fig. 3c) adsorption phase. Variations in adsorption rates indicated differential interaction strengths between BC700 and individual TC molecules. In the fast phase, DC (k1 = 41.77 h−1) and MNC (k1 = 8.24 h−1) exhibited the fastest adsorption kinetics, rapidly sequestering C=O active sites on BC700 and approaching equilibrium, whereas OTC showed the lowest rate (k1 = 3.30 h−1). In the slow adsorption stage, TC (k2 = 0.05 h−1) and OTC (k2 = 0.02 h−1) retained the lowest adsorption rates, failing to reach adsorption equilibrium in the fast phase and thereby displaying a sustained rise in adsorption capacity. Conversely, DC, MNC, and MTC showed minimal fluctuations in adsorption capacity, owing to their rapid attainment of adsorption equilibrium across both the fast and slow phases.

Figure 3.

Adsorption kinetics of TCs on BC700 and the impacts of TCs dissociation species. (a) Adsorption kinetic profiles of five TCs at 60 mg·L−1 onto 4 g·L−1 BC700 at pH 7. (b), (c) Fast-stage (k1), and slow-stage (k2) adsorption rate constants fitted by DEM. (d) Dissociation functional moieties of TCs and their corresponding pKa values. (e)–(i) pH-dependent speciation distributions of TC, MTC, OTC, MNC, and DC. (j) Pearson correlation coefficients between the relative abundances of TCs neutral (α2), and monoanionic (α3) species with k1 and k2.

TCs have substituents R1, R2, and R3 on three respective rings (Fig. 3d), which modulate their physicochemical properties[23] and thereby govern their adsorption kinetics onto BC700. Extensive literature has demonstrated that the distinct dissociation species of TCs under varying pH conditions exert a profound impact on their adsorption behaviors[5,6]. Although the three pKa values of five TCs are similar[9,24,25], the presence of different substituents leads to quantitative discrepancies in their existing species at the same pH. The proportions of TCs dissociation species under different pH conditions were calculated based on their pKa values, revealing that at pH 7, all five TCs predominantly existed as two species: α2 (neutral TCsH20) and α3 (monoanionic TCsH−) (Fig. 3e–i). Specifically, the order of α2 content from highest to lowest was DC (0.90) > MNC (0.86) > TC (0.83) > MTC (0.80) > OTC (0.66), while the order of α3 content was the reverse. Correlation analyses were performed between the proportions of dissociation species (α2 and α3) and adsorption rate constants (k1 and k2) (Fig. 3j). The results showed that α2 was positively correlated with k1 (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.63) and k2 (r = 0.61), whereas α3 exhibited negative correlations with k1 (r = −0.63) and k2 (r = −0.61). When OTC alone, DC alone, or both OTC and DC were excluded from the analysis, the correlation coefficients increased significantly to as high as 0.95 and −0.96 for α2 and α3, respectively. These findings indicate that the neutral, uncharged TCsH20 species dictates the rate of TCs adsorption, while the monoanionic TCsH− species experiences repulsion from the biochar surface. It is further confirmed that TCs adsorption onto BC700 does not involve chemisorption requiring the formation of strong chemical bonds; instead, it is driven by weak hydrogen bonding interactions between the –NH2 groups of TCs and the C=O moieties of BC700.

Molecular structural characteristics of TCs

-

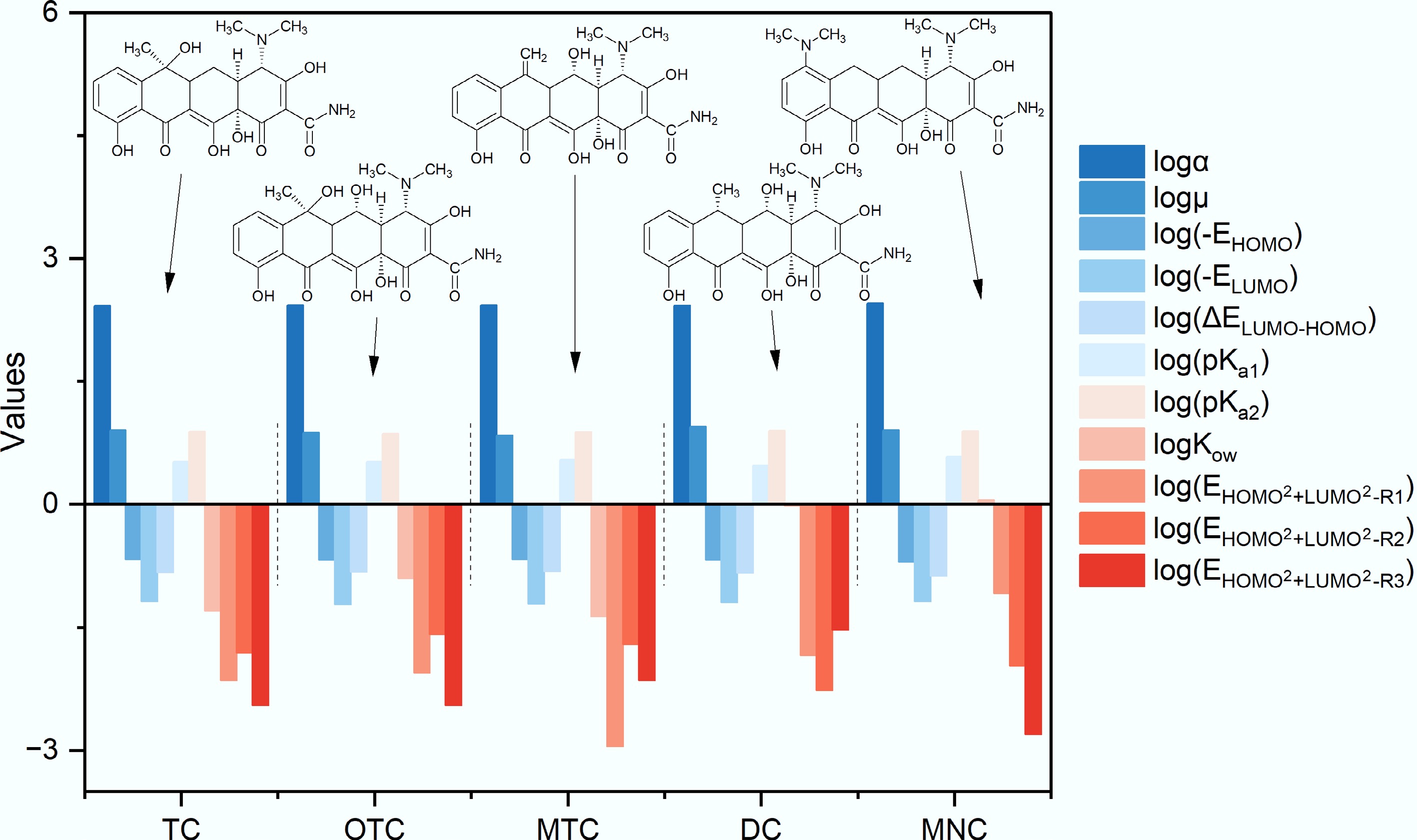

Substituents that differentiate TCs modulate their overall electronic configuration and spatial conformation, thereby influencing the formation of hydrogen bonds between the intrinsic −NH2 groups of TCs and the surface C=O moieties of BC700. From a structural perspective, TC bears a −CH3 and a −OH group as its R2 substituent; OTC differs from TC by an additional −OH group at the R3 position; MTC features =CH2 at R2 and −OH at R3; DC carries −CH3 at R2 and −OH at R3; and MNC is characterized by a −N(CH3)2 substituent at R1 (Fig. 4). To elucidate the impact of substituents on TCs molecular architectures, 11 molecular structural descriptors for TCs were compiled via quantum chemical calculations and literature retrieval. These descriptors include acid dissociation constants (pKa1 and pKa2), molecular polarity/interfacial interaction parameters (polarizability (α), dipole moment (μ), and octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow)[23]), and electronic structure parameters (highest occupied molecular orbital energy (EHOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (ELUMO), frontier orbital energy gap (ΔELUMO-HOMO), and the sum of the squares of EHOMO and ELUMO for the carbon atoms bonded to the three substituents (

${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}3} $

Figure 4.

Eleven structural descriptors of five TCs. All data were logarithmically transformed (base 10) for facilitation of plotting and comparative analysis.

Table 1. Detailed structural descriptors of five TCs

TC OTC MTC DC MNC α (a.u.) 264.3747 269.8470 268.2860 265.5643 284.5270 μ (a.u.) 8.0224 7.4779 6.9306 8.8518 7.9863 EHOMO (a.u.) −0.2143 −0.2105 −0.2145 −0.2106 −0.1991 ELUMO (a.u.) −0.0659 −0.0608 −0.0610 −0.0639 −0.0661 ΔELUMO−HOMO (a.u.) 0.1484 0.1497 0.1535 0.1467 0.1330 pKa1 3.3000 3.3000 3.5000 3.0000 3.8000 pKa2 7.7000 7.3000 7.6000 7.9700 7.8000 logKow −1.3000 −0.9000 −1.3700 −0.0200 0.0500 ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ (a.u.) 0.0071 0.0087 0.0011 0.0144 0.0828 ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ (a.u.) 0.0155 0.0262 0.0197 0.0055 0.0107 ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}3} $ (a.u.) 0.0036 0.0036 0.0071 0.0294 0.0016 Ranking of molecular polarity/interfacial interaction parameters and electronic structure parameters revealed that substituents alter the electron-donating/accepting capacity, polarity, and polarizability of TCs by modifying their electronic configurations. MNC exhibited the highest EHOMO (−0.1991 a.u.), rendering it the most prone to electron donation[26]; in contrast, OTC possessed the highest ELUMO (−0.0608 a.u.), making it the most susceptible to electron acceptance[26]. Given that TCs adsorb onto BC700 primarily via hydrogen bonding between their −NH2 groups and C=O moieties on BC700, which requires TCs to donate electrons, MNC displayed a high adsorption rate while OTC exhibited the slowest kinetics. EHOMO^2+LUMO^2 for the C atoms bonded to substituents R1, R2, and R3 reflects the electron cloud density at these sites, with higher values corresponding to greater electron cloud density[11]. Notably, the C atom linked to the R1 substituent (−N(CH3)2) of MNC had the highest electron cloud density (

${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2} $ On the other hand, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap (ΔELUMO−HOMO) correlates with molecular polarizability[27]: a smaller gap implies higher polarizability, meaning the electrons of TCs that have low ΔELUMO−HOMO are more easily perturbed by C=O groups on BC700. MNC (0.1330 a.u.), and DC (0.1467 a.u.) had the smallest energy gaps, consistent with their high adsorption rates. However, the calculated polarizability (α) revealed that OTC (269.8470 a.u.) exhibited a higher value than DC (265.5643 a.u.), yet the adsorption rate of the latter was considerably faster than that of the former. On the other hand, the dipole moment (μ) of TCs showed a strong correlation with the adsorption rate (r = 0.82). Evidently, a single parameter cannot adequately predict TCs' adsorption rates; a comprehensive integration of the aforementioned electronic structure parameters is required to establish the relationship between TCs' molecular structure and their adsorption kinetics onto BC700. Several factors should be considered when selecting the molecular structure parameters of TCs. For example, as discussed above, at pH 7, the abundances of monoanionic TCsH− and dianionic (TCsH22−) species are negligible; thus, only pKa1 and pKa2 were considered in subsequent analyses, with pKa3 excluded. Since physical adsorption also contributed to the interaction between TCs and biochar, Kow, which reflects the hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties of organic compounds, should be incorporated into the comprehensive analysis.

Quantitative correlation of molecular structure parameters with adsorption rates of TCs

-

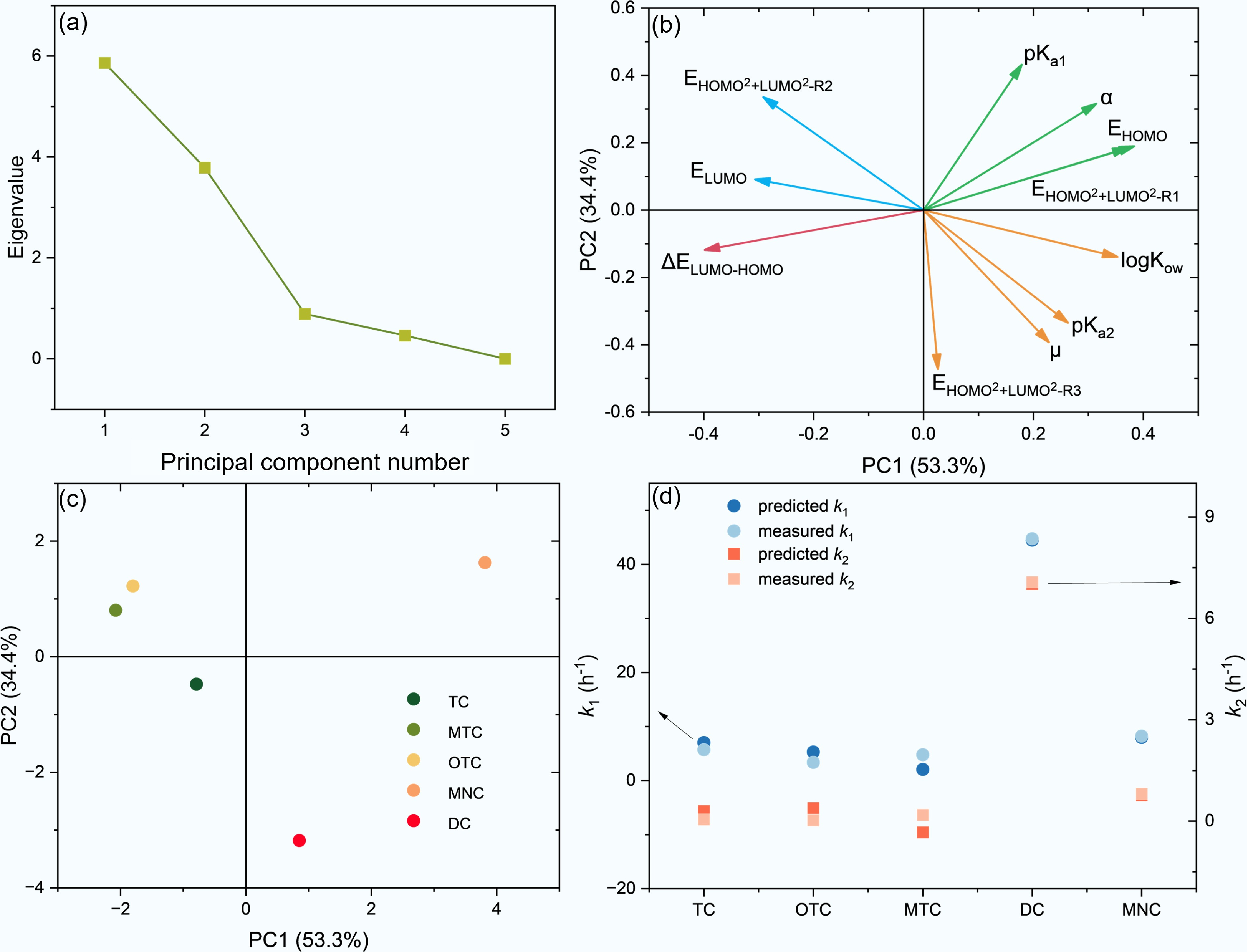

As discussed above, the influence of 11 molecular descriptors on the adsorption kinetics of TCs onto BC700 must be evaluated via a comprehensive multi-parameter framework. Given the presence of information redundancy among these descriptors, e.g., both α and ΔELUMO−HOMO can characterize molecular polarizability[27], PCA was employed using Origin 2025 to extract valid information from the 11 molecular descriptors[28]. The scree plot indicated that three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) could be derived from the 11 structural descriptors (Fig. 5a). Specifically, the cumulative variance explained by PC1 and PC2 reached 87.7%, while the combined contribution of PC1, PC2, and PC3 amounted to 95.8%. These results confirm that PCA can effectively highlight critical information and eliminate redundant data. The relationships between the scores of PC1, PC2, PC3 and the 11 structural descriptors are provided below—Eqs (4)−(6), and Fig. 5b:

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of TCs structural descriptors and multiple linear regression (MLR) of structure-adsorption rate relationships. (a) Scree plot of PC eigenvalues. (b) Loadings plot of TCs structural descriptors. (c) PC scores plot of individual TCs. (d) Comparison between measured and predicted values of TCs adsorption rate constants (k1, k2) derived from MLR models incorporating PC1, PC2, and PC3.

$ \begin{split} {PC1} \,= \,\;& 0.314 \,\times\, {\alpha } \,+\,0.228\,\times\, {\mu} \,+\,0.371 \,\times\, {E} _{ {HOMO} } \,-\,0.307\,\times\, {E} _{ {LUMO} } \\ \;& \,-\,0.399\,\times\, {\Delta E} _{ {LUMO-HOMO} } \,+\,0.179 \,\times\, {pK} _{ {a1} } \,+\,0.263 \,\times\, {pK} _{ {a2} } \\ \;&\,+\,0.353\,\times\, {logK} _{ {ow} }\,+\,0.383 \,\times\, {E} _{ {HOMO^2+LUMO^2-R1} } \,-\,0.292\\ \;&\,\times\, {E} _{ {HOMO^2+LUMO^2-R2} } \,+\,0.026\,\times\, {E} _{ {HOMO^2+LUMO^2-R3} } \end{split}$ (4) $\begin{split} PC2 \,= \,\;& 0.316 \,\times \, a \,-\, 0.393 \,\times \, \mu \,+ \, 0.185 \,\times \, E_{HOMO} \,+ \, 0.091 \,\times \, E_{LUMO} \\ \;& \,-\, 0.118 \,\times \, \Delta E_{LUMO-HOMO} \,+ \, 0.432 \,\times \, pK_{a1} \,-\, 0.335 \,\times \, pK_{a2} \\ \;&\,-\, 0.139 \,\times \, \log K_{ow}\,+ \, 0.190 \,\times \, E_{HOMO^2-LUMO^2-R1} \\ \;&\,+ \, 0.336 \,\times \, E_{HOMO^2-LUMO^2-R2} \,-\, 0.472 \,\times \, E_{HOMO^2-LUMO^2-R3} \end{split}$ (5) $\begin{split} PC3 \,=\,\;& 0.196 \,\times \, a \,+ \, 0.008 \,\times \, \mu \,+ \, 0.255 \,\times \, E_{HOMO} \,+ \, 0.648 \,\times \, E_{LUMO} \\ \;& \,+ \, 0.007\,\times \, \Delta E_{LUMO-HOMO} \,- \,0.184 \,\times \, pK_{a1}\, -\, 0.262 \,\times \, pK_{a2} \\ \;& \,+ \, 0.466\,\times \, \log K_{ow}\,+ \, 0.046 \,\times \, E_{HOMO^2+ LUMO^2-R1} \\ \;&\,+ \, 0.158 \,\times \, E_{HOMO^2+ LUMO^2-R2} \,+ \, 0.360 \,\times \, E_{HOMO^2+ LUMO^2-R3} \end{split}$ (6) The 11 molecular structural descriptors of TCs exhibited divergent impacts on PC1 and PC2. Specifically, the magnitude of influence was positively correlated with the absolute value of the loading coefficients for each descriptor or the length of the descriptor arrow projection onto the x-axis (PC1) or y-axis (PC2) in Fig. 5b. For PC1, all descriptors exerted a positive influence except for ΔELUMO−HOMO, ELUMO, and

${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}3} $ Following PCA of the 11 structural descriptors, the five TCs were naturally clustered into four distinct quadrants based on their structural characteristics (Fig. 5c). Specifically, DC with R3 (−OH) and R2 (−CH3) was positioned in the bottom-right quadrant of the coordinate system and was more strongly influenced by PC2 than by PC1, indicating that its adsorption behavior is more susceptible to the effects of

${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}3} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ To further establish the quantitative relationship between structural features and adsorption kinetics, MLR fitting analyses by Origin 2025 were performed by correlating the PC1, PC2, and PC3 scores with the TCs adsorption rate constants (k1 and k2)[17], yielding Eqs 7 and 8:

$ k_1=2.09\times\mathrm{PC}1-8.17\times\mathrm{PC}2+5.74\times\mathrm{PC}3+13.36\; R^2=0.9896 $ (7) $ k_2=0.37\times\mathrm{PC}1-1.39\times\mathrm{PC}2+1.14\times\mathrm{PC}3+1.63\; R^2=0.9876 $ (8) The two regression models exhibited excellent fitting performance with R2 exceeding 0.98, and the predicted values of k1 and k2 in Fig. 5d exhibit excellent consistency with the corresponding measured data, confirming their reliability for predicting the adsorption behaviors of a broader range of TCs onto BC700. Moreover, in both the k1 and k2 regression equations, the regression coefficient of PC1 was positive, while that of PC2 was negative. This observation is consistent with the aforementioned findings, further verifying that the adsorption of TCs onto BC700 is positively regulated by

${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}3} $ -

This study systematically investigated the structure-dependent adsorption behaviors and mechanisms of five TCs, including TC, OTC, MNC, MTC, and DC, on BC700 biochar. The 2D-FTIR-CoS characterization confirmed that TCs adsorption is dominated by hydrogen bonding between –NH2 groups of TCs and surface C=O moieties of BC700. At low TC concentrations, –NH2 exhibits a preferential binding to carboxyl –COOH C=O as the primary site, followed by ketone/ester O−C=O. In contrast, this preferential sequence becomes indistinct at high TC concentrations. Adsorption kinetic results showed all TCs followed DEM fitting, with a structure-dependent rate order: DC > MNC > TC > MTC > OTC. Neutral pH favored the uncharged TCsH20 species, and adsorption rates were positively correlated with TCsH20 abundance. Quantum chemical calculations and literature surveys generated 11 molecular descriptors for TCs. PCA identified three key principal components (PC1, PC2, PC3), with PC1 and PC2 collectively explaining 87.7% of the variance. Thus, only the most influential structural descriptors within PC1 and PC2 for the adsorption rate were discussed. PC1 is regulated by electronic structure and hydrophobicity-related descriptors, with

${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}1} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}2} $ ${\mathrm{E}}_{{\mathrm{HOMO}}^2+{\mathrm{LUMO}}^2-{\mathrm{R}}3} $ -

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Jiayi Yao: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing − original draft; Jihao Ji: experiment, data curation, formal analysis; Jiahong Zhang: experiment, data curation, formal analysis; Jing Fang: conceptualization, writing − review and editing, funding acquisition, supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42577019) and the Basic Operational Fund of Zhejiang University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2025QN051).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Hydrogen bonding dominates tetracycline adsorption on biochar across pH.

The −NH2 group of tetracycline preferentially binds to carboxyl C=O over ketone/ester C=O on biochar.

The adsorption rate order is: doxycycline > minocycline > tetracycline > methacycline > oxytetracycline.

Electron-donating R1 and non-donating R3 substituents boost, whereas electron-withdrawing R2 substituents inhibit, tetracyclines adsorption rates.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yao J, Ji J, Zhang J, Fang J. 2026. Molecular structure-dependent adsorption mechanisms of tetracycline antibiotics congeners on biochar. Biochar X 2: e008 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0026-0007

Molecular structure-dependent adsorption mechanisms of tetracycline antibiotics congeners on biochar

- Received: 14 December 2025

- Revised: 31 December 2025

- Accepted: 14 January 2026

- Published online: 13 February 2026

Abstract: Tetracycline antibiotics (TCs) are ubiquitous aquatic contaminants that endanger human health by facilitating antibiotic resistance gene proliferation. Although biochar (BC)-based TCs adsorption has been widely studied, the effects of TCs' molecular structural heterogeneity remain underexplored. Herein, two-dimensional-Fourier transform infrared correlation spectroscopy (2D-FTIR-CoS) and quantum chemical computations were integrated to systematically investigate the structure-dependent adsorption behaviors and mechanisms of five TCs, including tetracycline (TC), oxytetracycline (OTC), minocycline (MNC), methacycline (MTC), and doxycycline (DC), on rice straw-derived BC pyrolyzed at 700 °C (BC700). Hydrogen bonding between TCs amide –NH2 groups and BC700 surface C=O moieties was identified as the dominant mechanism across all pH conditions; at low TCs concentrations, −NH2 preferentially binds carboxyl C=O over ketone/ester C=O, while this sequence becomes ambiguous at high concentrations. Kinetic studies confirmed that all TCs fitted the double-exponential model (DEM), with an adsorption rate order of DC > MNC > TC > MTC > OTC. Structure-kinetics correlation analysis revealed that electron-donating R1 (e.g., −N(CH3)2 of MNC) and non-electron-donating R3 (e.g., alicyclic –OH of DC) substituents of TCs enhanced adsorption by amplifying BC700-induced electronic polarization, elevating –NH2 electron density, and strengthening hydrogen bonding, whereas electron-withdrawing R2 substituents (e.g., =CH2 of MTC, −CH3/−OH of TC and OTC) exerted inhibitory effects. Multiple linear regression (MLR) was further employed to construct reliable predictive models linking TCs' structural principal components to adsorption rate constants (k1, k2) derived by DEM. This study advances the fundamental understanding of structure-dependent TCs adsorption on BC, provides a quantitative basis for customizing high-efficiency BC adsorbents, and offers critical guidance for remediating TCs-contaminated aquatic environments.

-

Key words:

- Tetracycline antibiotics /

- Biochar /

- Molecular structure /

- Hydrogen bonding