-

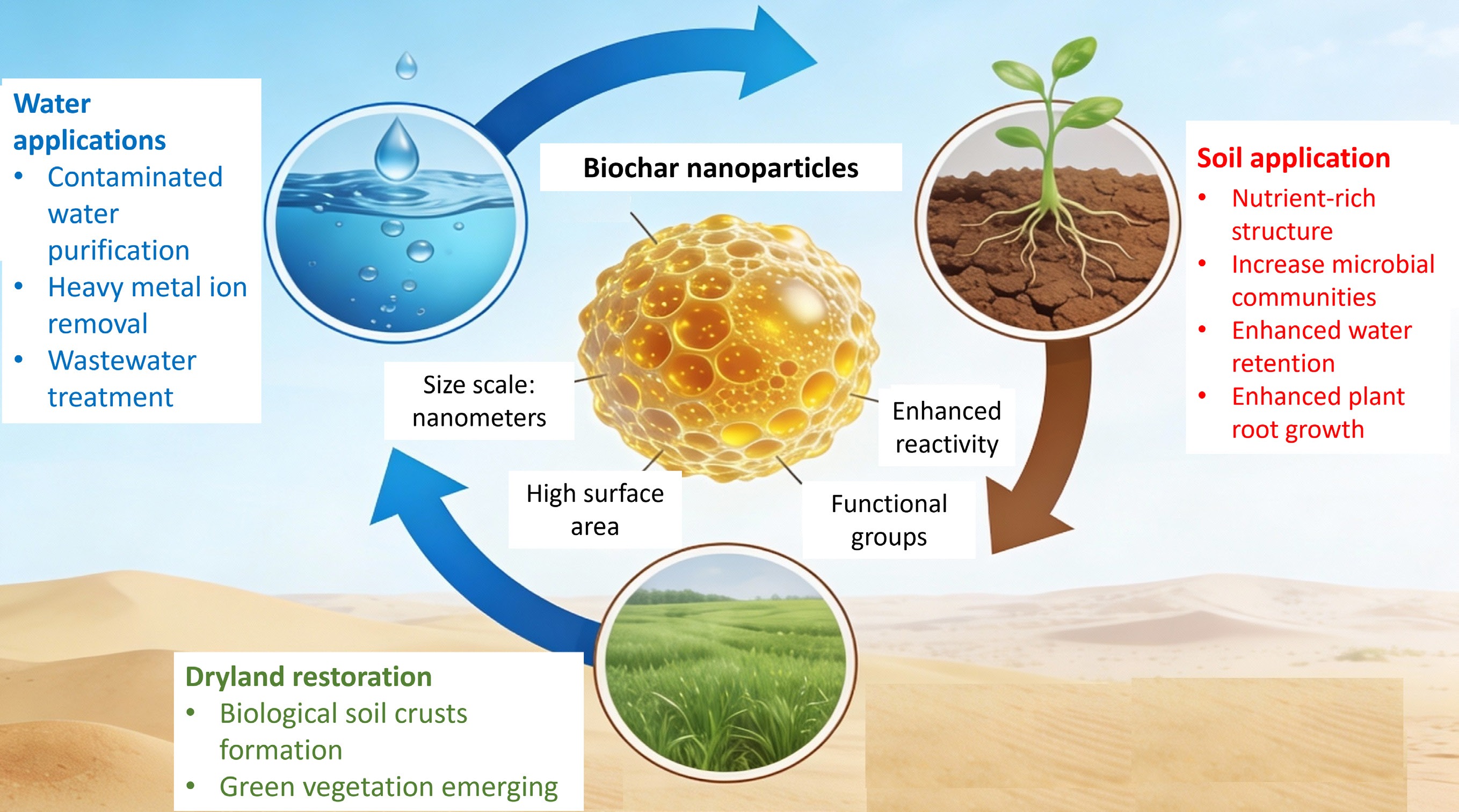

Carbon-based nanomaterials have garnered growing scientific interest because of their wide-ranging potential in agricultural and environmental applications. Among these materials, biochar has gained particular prominence due to its multifunctional contributions to climate change mitigation, pollution remediation, and soil quality enhancement. Biochar is a carbon-rich solid produced via the thermochemical conversion of biomass feedstocks—including agricultural residues, lignocellulosic materials, animal manures, and other organic wastes—under oxygen-limited conditions (gasification) or in the absence of oxygen (pyrolysis)[1]. Biochar production is generally considered cost-effective and environmentally sustainable, as it utilizes readily available waste resources, typically involves relatively low energy consumption, and is commonly carried out at temperatures below 700 °C[2,3]. These characteristics have supported its widespread use in both research and practical applications aimed at improving soil properties, promoting plant growth, and mitigating environmental pollution (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Multifunctional benefits of biochar: physical, chemical, and biological soil improvements.

Beyond its environmental benefits, biochar has long been recognized as a valuable amendment for promoting agricultural sustainability[4]. The physicochemical properties of bulk biochar vary with feedstock type and thermochemical conditions, resulting in particle sizes that commonly range from the micrometer to centimeter scale[5]. These properties influence its interaction with soil, water, and contaminants. Importantly, biochar also serves as a versatile precursor material that can be further processed into finer particles to enhance its functional performance.

Nanobiochar represents a refined form of bulk biochar that has been engineered to achieve substantially smaller particle sizes, particularly at the nanoscale. Biochar itself is defined as a stable form of charcoal derived from biomass sources, including wood, agricultural residues, herbaceous materials, animal manure, or sewage sludge, intended for applications that prevent rapid carbon release to the atmosphere[6]. Through additional processing, bulk biochar can be transformed into nanobiochar using methods such as hydrothermal carbonization, ball milling, and sonication[7,8]. Reducing biochar particle size to the microscale (10–600 μm) increases the number of exposed adsorption sites, thereby improving its ability to bind contaminants[9,10]. Further reduction to the nanoscale (≤ 100 nm) dramatically enhances surface-to-volume ratio, surface energy, reactivity, and biological effectiveness[10].

As a result of these enhanced properties, nanobiochar has become a focal point of contemporary research, combining the established benefits of bulk biochar with the unique advantages of nanoscale materials. Nanometer-sized particles are typically produced through mechanical exfoliation or by controlling thermochemical parameters such as pyrolysis temperature[11,12]. This convergence of carbon stability, high reactivity, and tunable surface properties positions nanobiochar as a promising, yet complex, material for advanced environmental and agricultural applications.

While nanobiochar itself offers enhanced properties through size reduction, further advances have extended these applications through the synthesis of biochar nanocomposites, which integrate nanobiochar or bulk biochar with functional nanomaterials to achieve multifunctional properties[13,14]. Biochar nanocomposites are hybrid, multi-component materials created by incorporating functional nanomaterials (metal oxides, graphene, magnetic iron particles, etc.) into biochar or by coating biochar with nanoparticles. Nanocomposites incorporating nanobiochar display improved pore architecture, surface chemistry, catalytic activity, and separation efficiency, enabling simultaneous adsorption and degradation of contaminants[15,16].

Biochar-based materials have been widely investigated as adsorbents due to their role in improving plant performance, enhancing carbon sequestration, and contributing to climate mitigation[17,18]. Their physicochemical characteristics—high surface area, microporosity, environmental abundance, and strong sorption capacity—enable them to remove a variety of contaminants from aqueous systems, including minerals, vitamins, and pharmaceuticals[19,20]. During thermochemical processing, biofuels and syngas are also produced alongside biochar, making the entire process economically more attractive relative to direct biomass combustion[19]. However, the performance of biochar in water treatment can be constrained by the choice of feedstock, reaction conditions, and pyrolysis method[15].

Raw biochar typically exhibits limited adsorption capacity, and powdered forms can be difficult to recover from aqueous environments[21,22]. Nanobiochar helps overcome these limitations by providing enhanced chemical, structural, and mechanical features. Its nanoscale size offers a larger surface area and a greater abundance of reactive functional groups, as well as improved mechanical and thermal stability[23]. Moreover, nanobiochar often exhibits more negative zeta potentials, smaller hydrodynamic radii, and a higher density of carbon and oxygen defect sites capable of generating reactive organic species, all of which contribute to superior adsorption performance compared with bulk biochar[24].

Defects in carbon nanomaterials—whether topological or located at material edges—play a major role in modulating their physicochemical behavior. These structural irregularities increase the number of unpaired π electrons, reduce formation energy, enhance electron transfer, and influence catalytic reactions such as oxygen reduction[25]. Owing to these properties, nanobiochar is now widely recognized as an effective soil amendment, enzyme support, and multifunctional adsorbent. Its high specific surface area, microporosity, and hydrophobic surfaces enable it to retain diverse pollutants, including herbicides, heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Its inherent alkalinity also contributes to reductions in soil acidity[26,27].

Nanobiochar may exhibit properties different from its well-known macroforms, and these different properties have raised questions about potential environmental risks, including toxicity in aquatic and terrestrial environments, the remediation of pollutants, and influence on crop yields[28]. Hybrid nanocomposites, such as carbon nanotube–biochar combinations, have shown promise as low-cost materials for removing dyes and organic contaminants. Emerging evidence indicates that such hybrids may also provide efficient and economical options for heavy metal remediation[14].

With drylands accounting for 41% of the Earth's land surface and experiencing degradation at rates approaching 12 million hectares annually, there is an urgent need for innovative restoration strategies[29]. Conventional approaches often fail due to extreme abiotic stress, particularly in hyper-arid regions. In this context, biochar offers a promising pathway by facilitating the establishment and development of biological soil crusts (BSCs)[30,31]. Through nanoscale interactions with pioneer cyanobacteria, nanobiochar can enhance exopolysaccharides (EPS) production, improve moisture retention, and help stabilize mobile sandy substrates, effectively acting as a bio-geoengineering agent.

This review bridges recognized knowledge gaps by establishing mechanistic connections between nanobiochar production methodologies, encompassing mechanical attrition and hydrothermal synthesis, and the physicochemical transformations governing material performance. Rather than enumerating isolated case studies, it develops integrated design-function frameworks that clarify mechanistic explanations for nanobiochar's enhanced functionality relative to macroscale biochar amendments across diverse soil and aqueous environments. Significantly, this analysis advances nanobiochar as a bio-geoengineering platform material capable of catalyzing cyanobacterial recruitment, enhancing extracellular polysaccharide biosynthesis, and stabilizing unstable desert substrates. Consequently, nanobiochar transitions from a conventional soil conditioner to a strategic agent for large-scale desertification mitigation and ecological recovery of degraded arid lands.

This review pursues four integrated objectives: (1) to establish quantitative relationships between nanobiochar synthesis pathways and the physicochemical attributes controlling functional capacity; (2) to identify convergent mechanistic principles underlying performance in nutrient bioavailability and pollutant immobilization; (3) to delineate nanobiochar-BSC interactions as a frontier research domain for accelerating dryland ecosystem recovery; and (4) to systematically evaluate sustainability constraints encompassing production energy intensity, technology scalability, environmental persistence, and potential ecological perturbations. These integrated analyses aim to inform responsible technology translation from laboratory-scale investigations toward operational deployment in agricultural and restoration contexts.

The objectives of this review are fourfold: (i) to connect nanobiochar synthesis methods with key physicochemical properties that govern functionality; (ii) to identify shared mechanistic principles underlying its performance in nutrient management and contaminant remediation; (iii) to establish nanobiochar–BSC interactions as a promising frontier for accelerating dryland recovery; and (iv) to critically assess sustainability challenges related to energy demand, scalability, environmental fate, and potential ecological risks. Together, these perspectives aim to support the responsible translation of nanobiochar from laboratory studies to real-world agricultural and ecological applications.

A systematic literature review was conducted, synthesizing evidence from four international scientific databases—Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar—which captured peer-reviewed primary literature, edited chapters, and technical reports. Literature collection employed a hierarchical keyword strategy across three thematic domains to optimize both comprehensiveness and specificity. Domain 1 (Production and Characterization) utilized search terms such as nanobiochar synthesis, ball-milled biochar, hydrothermal carbonization, biochar nanocomposites, and physicochemical properties. Domain 2 (Agricultural and Environmental Applications) incorporated keywords including soil remediation, nutrient release, heavy metal adsorption, wastewater treatment, and sustainable agriculture. Domain 3 (Dryland Restoration— the review's primary focus) employed cross-disciplinary search strings coupling nanotechnology with arid ecological processes: nanobiochar and biological soil crusts, cyanobacteria inoculation, dryland restoration, desertification control, and soil aggregate stability. This tiered methodology facilitated the systematic capture of knowledge spanning nanobiochar development, mechanistic functionality, and innovative applications in degraded arid ecosystems.

-

Biochar synthesis employs diverse thermochemical pathways. The primary routes—slow pyrolysis, fast pyrolysis, gasification, and carbonization—convert biomass feedstocks, including agricultural residues, wood, and animal waste, into biochar[32,33]. Among these approaches, slow pyrolysis in oxygen-depleted conditions yields approximately 35% biochar by mass[34–36]. Fast pyrolysis is commonly preferred for biofuel generation, whereas gasification is mainly used to produce syngas that can subsequently be utilized for heat and power production[37]. Previous studies have shown that lignocellulosic feedstocks produce greater amounts of nanobiochar than municipal solid waste materials[3]. The effectiveness of biochar for targeted applications can be significantly improved through various physical and chemical modification strategies. Chemical approaches include CO2 activation, oxidative treatments, acid or alkaline modification, steam activation, and the incorporation of engineered nanoparticles[38]. In contrast, physical modification methods, such as ball milling, have demonstrated considerable potential but remain less extensively investigated[38,39].

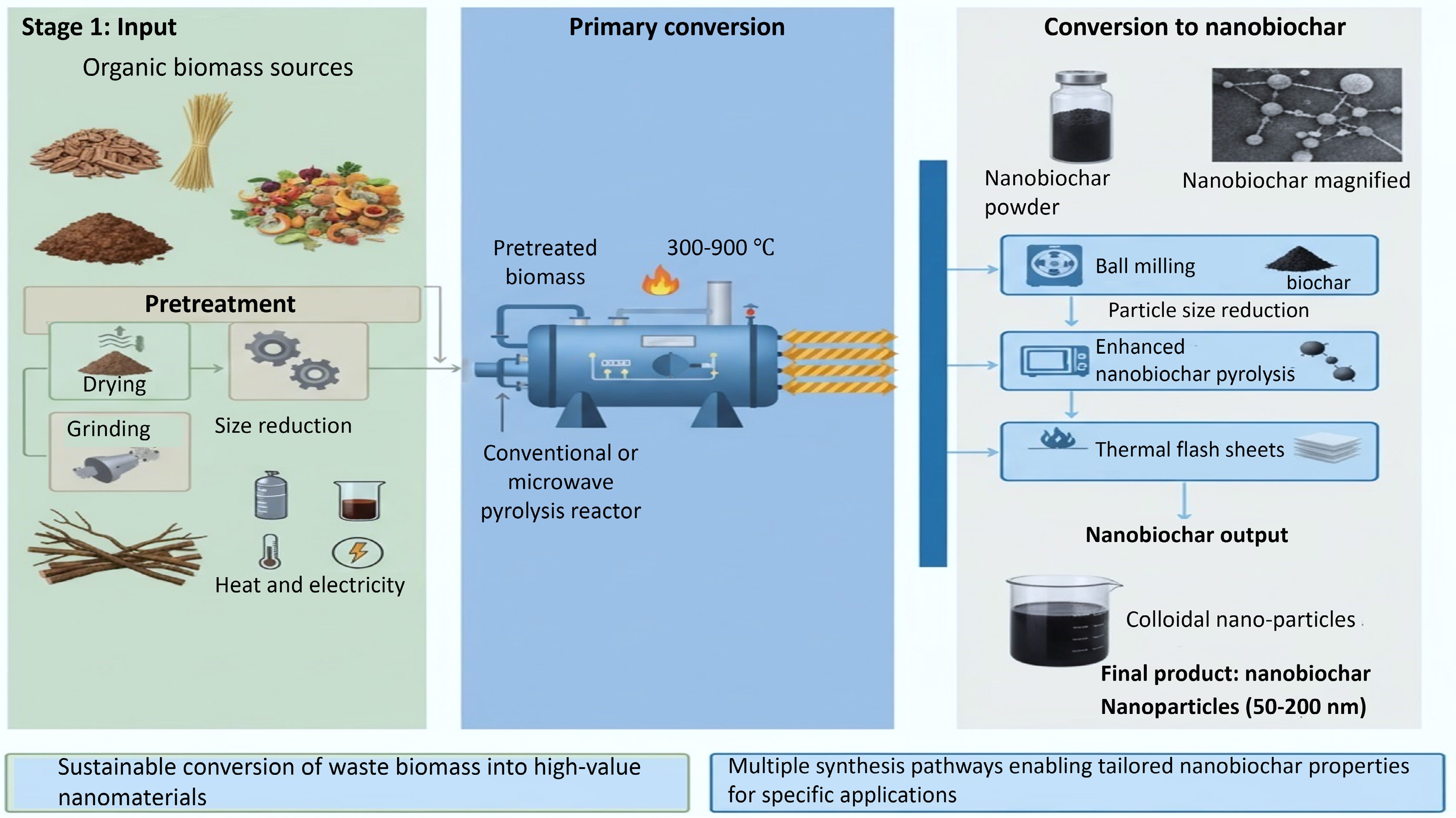

Nanobiochar synthesis involves various techniques applied to conventional biochar. Mechanical grinding is employed to generate nanoparticles (Fig. 2), while flash heating directly produces graphitic nanosheets from biochar[40]. Ultrasonic vibration and sonication techniques disperse biochar and facilitate the formation of nanosized particles[41]. Ball milling represents the most widely applied industrial method for nanobiochar production[42]. In this process, repeated impacts and friction generated by moving metallic balls within a milling chamber induce bond rupture and facilitate charge redistribution within the material. The resulting particle size distribution can be precisely regulated by modifying operational parameters such as milling time, rotational speed, and ball-to-material ratio[43,44]. Alternative methods for nanobiochar preparation include double-disc milling and vibration disc milling, with the latter demonstrating superior results in generating a higher quantity of nanobiochar with uniform shape and size[41]. Additionally, nanobiochar can be produced through a hydrothermal reaction method using agricultural waste and its by-products. For instance, cattle dung and soybean straw can be converted into bulk biochar, which is then subjected to concentrated sulfuric and nitric acid digestion in a high-pressure hydrothermal reactor.

Several studies have investigated the creation of functional composites by incorporating modified nanoparticles into biomass prior to pyrolysis. For example, graphene-enhanced biochar composites were produced using slow pyrolysis of wheat straw biomass treated with graphene. The results indicated that graphene-coated biochar exhibited increased surface area, enhanced thermal stability, and improved mercury and phenanthrene removal capabilities, along with a greater abundance of functional groups, compared to untreated biochar[45]. The development of biochar-based nanocomposites, which integrate the advantages of biochar with various nanomaterials, has shown significant promise. Nanobiochar particles typically exhibit sizes in the nanometer range, achievable through methods such as controlling exfoliation or pyrolysis temperature techniques, as reported in numerous studies[46,47]. Exfoliated biochar has been observed to possess particle sizes smaller than 10 nm.

Magnetic nanobiochar composites have been synthesized by first carbonizing biochar via pyrolysis, followed by FeCl3 pretreatment, sulfuric acid sulfonation, and oleic acid acidification to enhance acidity, ultimately yielding magnetic nanobiochar composites with improved catalytic properties. Nanobiochar derived from pine wood biochar has been successfully produced using the planetary ball mill method. Pretreating the biochar prior to milling reduced particle size by approximately 60 nm and increased the nanobiochar surface area by 15-fold compared to conventional biochar.

Thermal and chemical treatments of biomass not only yield syngas and biofuels but also promote biochar formation, thereby addressing multiple objectives: waste recycling, pollutant removal, energy production, and carbon sequestration[48]. Therefore, the production of biochar nanomaterials holds significant promise in effectively addressing these goals. The demonstrated advantages of nanocomposites suggest their potential as innovative adsorbents for economically removing pollutants such as chromium (Cr VI) from aqueous solutions. Tailored biochar nanocomposites can be synthesized by slow pyrolysis of bagasse biomass coated with a suspension of carbon nanotubes[49]. On the other hand, physical modification techniques such as ball milling have not gained significant attention, despite limited research indicating promising outcomes that merit further exploration. Mechanical grinding or milling is commonly employed to generate nanoparticles[50]. Despite the application of mechanical techniques, direct nanobiochar production through flash ignition can lead to the formation of graphitic nanosheets. Researchers have also employed ultrasonic vibration to physically disintegrate biochar, followed by sonication to produce nanosized particles[51]. According to current literature, nanobiochar production via ball milling is considered the most suitable and recommended method[52]. Ball milling achieves grinding through particle collisions, which decreases particle size. Another method for producing nanobiochar is double-disc milling, although its higher operational costs make it less common[34].

While numerous strategies exist for nanobiochar fabrication, selecting the appropriate synthesis pathway is critical for determining the material's final physicochemical properties and scalability. As summarized in Table 1, production methods are generally categorized into 'top-down' approaches (e.g., ball milling), and 'bottom-up' approaches (e.g., hydrothermal carbonization). Top-down methods, which rely on mechanical attrition, are currently favored for large-scale environmental applications due to their scalability and solvent-free nature. However, bottom-up synthesis allows for superior control over surface functionality, creating 'hydrochars' that may offer enhanced water-retention capabilities valuable for dryland restoration. Table 1 provides a comparative assessment of these primary synthesis routes, evaluating their respective advantages, limitations, and potential for industrial scaling.

Table 1. Comprehensive comparison of nanobiochar synthesis methods: production pathways and performance metrics

Synthesis method Classification and process description Key advantages Limitations Ref. Ball milling (Top-down) Mechanical grinding of bulk biochar using planetary mills; repeated impacts and friction induce particle size reduction; parameters include milling time, rotational speed, and ball-to-material ratio Eco-friendly; solvent-free; significantly increases surface area (up to 15-fold); creates acidic and oxygen-containing functional groups crucial for water retention; can be integrated into existing biochar supply chains High energy consumption; long processing times; potential contamination from milling media; particle size distribution variability; requires careful optimization of milling parameters [56−62] Hydrothermal carbonization (Bottom-up) Thermochemical conversion of wet biomass in water at high pressure and temperature (using concentrated sulfuric and nitric acid in high-pressure reactor) Produces uniform, spherical hydrochar nanoparticles; rich in surface functional groups; ideal for coating seeds or bacteria; superior control over surface functionality; enhanced water-retention Lower porosity compared to pyrolysis chars; requires post-synthesis activation; expensive reactor infrastructure; higher capital costs; more complex operational parameters [34,59] Pyrolysis + sonication (Hybrid) Conventional pyrolysis at 500–700 °C followed by high-intensity ultrasonic exfoliation; ultrasonic vibration physically disintegrates biochar to facilitate nanosized particle formation Effectively separates graphitic layers; improves aqueous dispersion; ideal for hydro-seeding applications; carbon enrichment through selective ash removal; enhanced dispersion in water Lower yield of nanoscale fraction; difficulty achieving uniform particle size distribution; energy-intensive sonication stage; incomplete particle separation [20,40,63] Vibration disc milling (Top-down) Similar to ball milling but uses vibrating disc mechanism instead of planetary mills; mechanical particle reduction through disc oscillation Superior results compared to ball milling in uniform shape and size generation; higher quantity of nanobiochar produced; consistent particle morphology Higher operational costs than planetary ball milling; less widely available equipment; similar energy demands [34,41] Double-disc milling (Top-down) Mechanical grinding between rotating discs; two-stage milling process for particle size reduction Produces fine particles; alternative to ball milling; suitable for specific feedstock types Higher operational costs; limited industrial adoption; requires specialized equipment maintenance [34] The synthesis of nanobiochar from diverse feedstocks results in method-specific transformations in physicochemical properties that clearly distinguish it from bulk biochar. As summarized in Table 2, nanobiochar characteristics arise from distinct interactions between feedstock type and production technique. Sonication promotes carbon enrichment primarily through selective ash removal[40], whereas mechanical milling increases the hydrogen-containing functional groups and enhances structural and mechanical properties[53]. Microwave-assisted processing yields nanobiochar with high carbon purity and improved thermal stability[54], while chemical modification combined with thermal treatment produces materials with highly developed surface characteristics suitable for adsorption-driven applications[55]. These contrasting pathways highlight the importance of tailoring nanobiochar production protocols to meet specific environmental remediation and industrial performance objectives.

Table 2. Comprehensive physicochemical characterization of biochar and nanobiochar: transformation of properties by feedstock type and production method

Feedstock type Synthesis method

and conditionsParticle size transformation Surface area (m2/g) Moisture (%) Ash (%) H/C ratio Ref. Wheat straw Pyrolysis at 700 °C followed by sonication Bulk biochar reduced to nanoparticles via ultrasonic exfoliation Bulk: 56.65;

Nano: 88.4Bulk: 41.14;

Nano: 52.35Bulk: 53.87;

Nano: 27.88Bulk: 0.39;

Nano: 0.67[40] Dairy manure Pyrolysis at 500 °C with sonication

(30 min) and centrifugationBulk biochar transformed to nanoparticles through ultrasonic separation − Bulk: 38.5;

Nano: 56.6Bulk: 50.5;

Nano: 6.58Bulk: 0.12;

Nano: 3.65[64] Corn straw Pyrolysis at 500 °C with planetary ball milling (600 rpm, 150 min) Bulk biochar mechanically milled to approximately 60 nm particle size Bulk: 8.1;

Nano: 7.9Bulk: 5.13;

Nano: 6.27Bulk: 78.96;

Nano: 77.62Bulk: 0.72;

Nano: 0.51[53] Rice husk Pyrolysis at 500 °C with planetary ball milling (600 rpm, 150 min) Bulk biochar ground to nanoparticles via mechanical attrition Bulk: 8.6;

Nano: 8.7Bulk: 31.55;

Nano: 31.51Bulk: 54.62;

Nano: 53.05Bulk: 0.77;

Nano: 0.78[53] Pine wood Pyrolysis at 525 °C with ball milling (575 rpm, 100 min) Bulk biochar mechanically reduced to nanoscale particles Bulk: 47.25;

Nano: higher valuesBulk: 2;

Nano: 2.11− Bulk: 1.0;

Nano: 0.5[65] Rice hull Carbonization at 600 °C with centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 30 min) and freeze-drying Bulk biochar processed to nanoparticles through centrifugal separation Bulk: 27.1;

Nano: 123.2Bulk: 79.62;

Nano: 80.87Bulk: 1.08;

Nano: 1.27− [66] Rice husk Pyrolysis at 600 °C with planetary ball milling and chemical amendment

(Iron Oxide nanobiochar)Bulk biochar converted to nanoparticles Bulk: —;

Nano: 1,736− − − [67] A dash (—) indicates that specific data for that property were not reported. H/C: Hydrogen-to-Carbon ratio. -

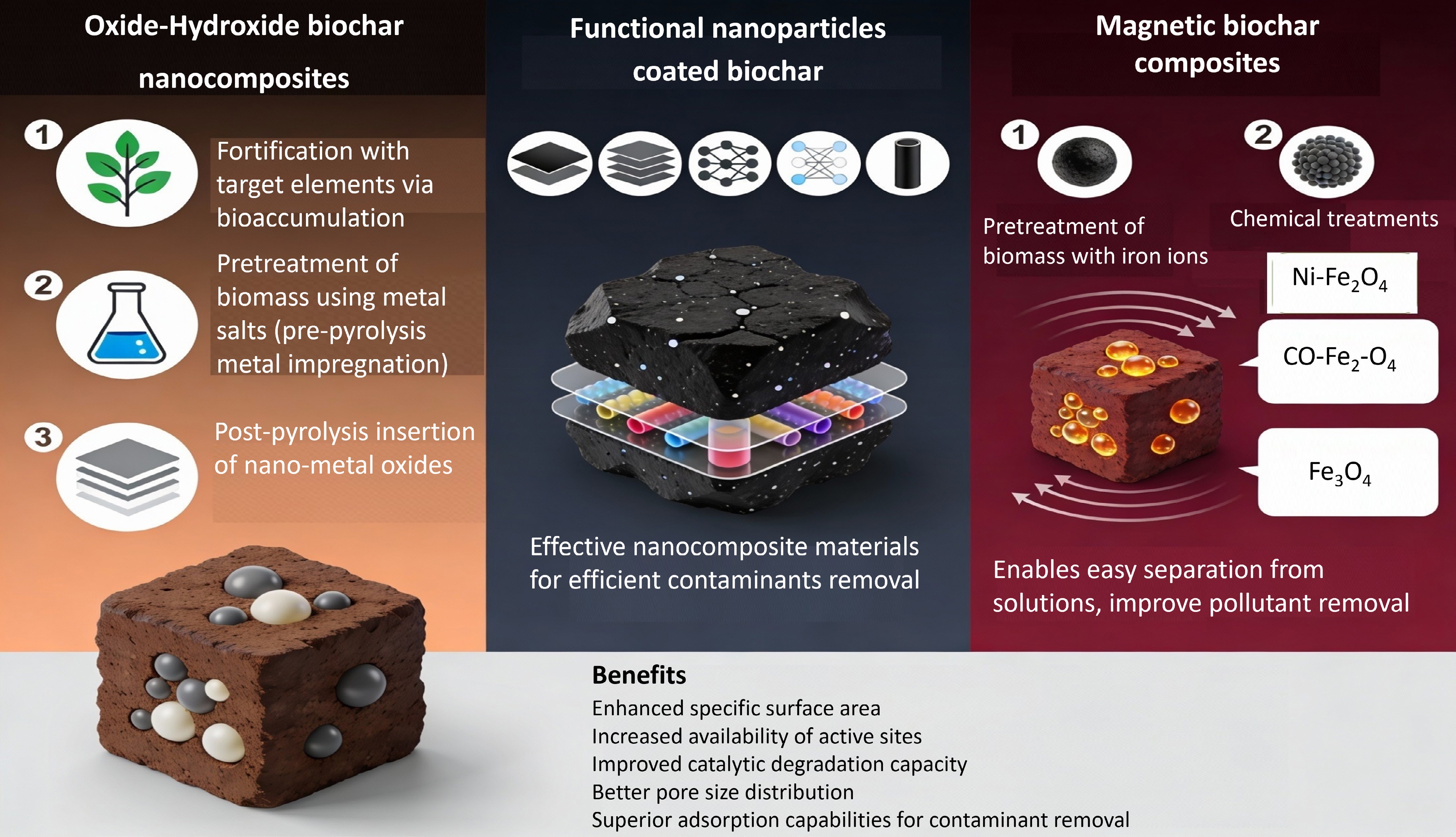

The fabrication methods for various biochar-based nanomaterials are illustrated in Fig. 3. Based on the nanomaterials incorporated into nanobiochar, these materials can be classified into three categories: oxide/hydroxide-biochar nanocomposites, magnetic-biochar nanocomposites, and biochar coated with functional nanoparticles (such as graphene, graphene oxide, chitosan, and carbon nanotubes). These composites are synthesized through different methods, typically involving two treatment processes: pre-treatment and post-treatment of biomass[15].

Figure 3.

Engineering biochar nanocomposites: synthesis methods for metal oxide, graphene, and magnetic systems.

Oxide-hydroxide surface modifications

-

Oxide/hydroxide biochar nanocomposites are primarily synthesized through three methods: (i) fortification with target elements via bioaccumulation; (ii) pre-treatment of biomass using metal salts; and (iii) post-pyrolysis insertion of nanometal oxides. The first two methods involve pre-pyrolysis metal impregnation of the biomass, whereas the third method involves the direct introduction of oxide/hydroxide nanometals into the pyrolyzed biochar[15,16].

Functional particle surface coatings

-

Biochar coated with functional nanoparticles, including graphene and its carbon, chitosan, oxide nanotubes, and layered double hydroxides, forms effective nanocomposite materials. These composites are capable of efficiently removing various contaminants.

Magnetic iron oxide integration

-

Considering the challenges associated with separating biochar from aqueous solutions, magnetic biochar composites can be synthesized using two primary approaches: pre-treatment of biomass with iron ions or chemical co-precipitation of iron oxides onto biochar. These methods facilitate the coating of nanosized magnetic iron oxides, such as CoFe2O4 and Fe3O4[68,69], onto the biochar surface. This modification not only imparts magnetic properties to the biochar, enabling easy separation from solutions, but also enhances the availability of active sites for iron oxide, thereby improving the removal of pollutants and increasing adsorption capacity[15].

Biochar-based nanocomposites, which exhibit enhanced parameters such as specific surface area, availability of active sites, catalytic degradation capacity, pore size distribution, pore volume, and ease of separation, have demonstrated high efficiency in contaminant removal. Numerous studies have shown that these composites possess superior adsorption capabilities, allowing them to adsorb a wide variety of contaminants from aqueous solutions[70,71]. Additionally, these nanocomposites, when incorporating diverse reductive/oxidative and catalytic nanoparticles (such as graphitic C3N4 and nanoscale zero-valent iron), can simultaneously adsorb and degrade various toxic substances[15]. Therefore, biochar-based nanocomposites hold significant potential for treating various waste materials and have diverse environmental applications.

-

Biochar, an organic material, has been recognized for its diverse applications in agriculture, including enhancing plant growth, managing diseases, remediating pesticides, serving as a fertilizer and soil amendment, and supporting microbial growth. Additionally, biochar has been reported to improve crop productivity, reduce soil salinity, and enhance soil quality and plant biomass. The incorporation of biochar into agricultural soils has also been shown to decrease dependence on chemical fertilizers, particularly nitrogen fertilizers, thereby reducing nitrogen leaching into groundwater.

Crop productivity improvements

-

Global agriculture faces a critical soil nutrient deficit driven by multiple anthropogenic pressures: intensive monoculture, livestock overgrazing, forest clearance, and industrialization. Traditionally, chemical fertilizers have been the primary solution for addressing soil nutrient deficiencies[72]. While synthetic fertilizers can temporarily remedy these deficiencies, their continuous application generates significant environmental costs through nutrient runoff and groundwater contamination[73−76]. Despite numerous strategies proposed to tackle nutrient management challenges and resource limitations, practical solutions remain scarce.

Recent evidence indicates that nanobiochar amendments act as highly effective soil conditioners, mitigating nutrient loss while sustaining plant-available nutrient pools through enhanced sorption and controlled release mechanisms[77,78]. Biochar can improve fertilizer use efficiency by preserving nutrients and reducing their loss from soil[79]. Researchers have documented favorable plant responses to biochar amendments, noting that nanobiochar functions effectively as a soil conditioner that enhances plant growth by effectively delivering and retaining nutrients, among other benefits[80]. Nanobiochar enhances plant nutrient acquisition due to its nutrient-rich composition and release characteristics, as well as its ability to increase nutrient sorption, enhance soil cation exchange capacity, improve soil physical properties, boost water retention capacity, and adjust soil pH[81].

Nanobiochar has demonstrated more promising results in enhancing plant growth in acidic soils compared to alkaline soils[82]. A study by Graber et al.[83] investigated the effects of nanobiochar in soilless growth media, finding significant benefits in improving yields of crops such as peppers and tomatoes. With the horticultural industry increasingly acknowledging the need to reduce or eliminate peat use in favor of more sustainable and cost-effective growth media, biochar has emerged as a leading alternative. Research indicates that combining biochar with engineered nanomaterials and chemicals can provide additional benefits. For instance, the use of biochar with water-soluble carbon nanotubes significantly enhanced wheat growth[17]. In terms of root growth, alkaline nanobiochar has been shown to significantly increase root biomass compared to biochar with a lower pH[84]. Both biochar and non-pyrogenic organic amendments have demonstrated positive effects on plant growth; their variable impacts can limit their widespread agricultural use[85]. A study by Scheifele et al.[86] found that applying bamboo biochar at concentrations below 10% stimulated nodulation and improved soybean growth. Plant nutrition and dry mass are influenced by the quantity and type of biomass applied during agricultural practices and cropping.

Soil-water dynamics

-

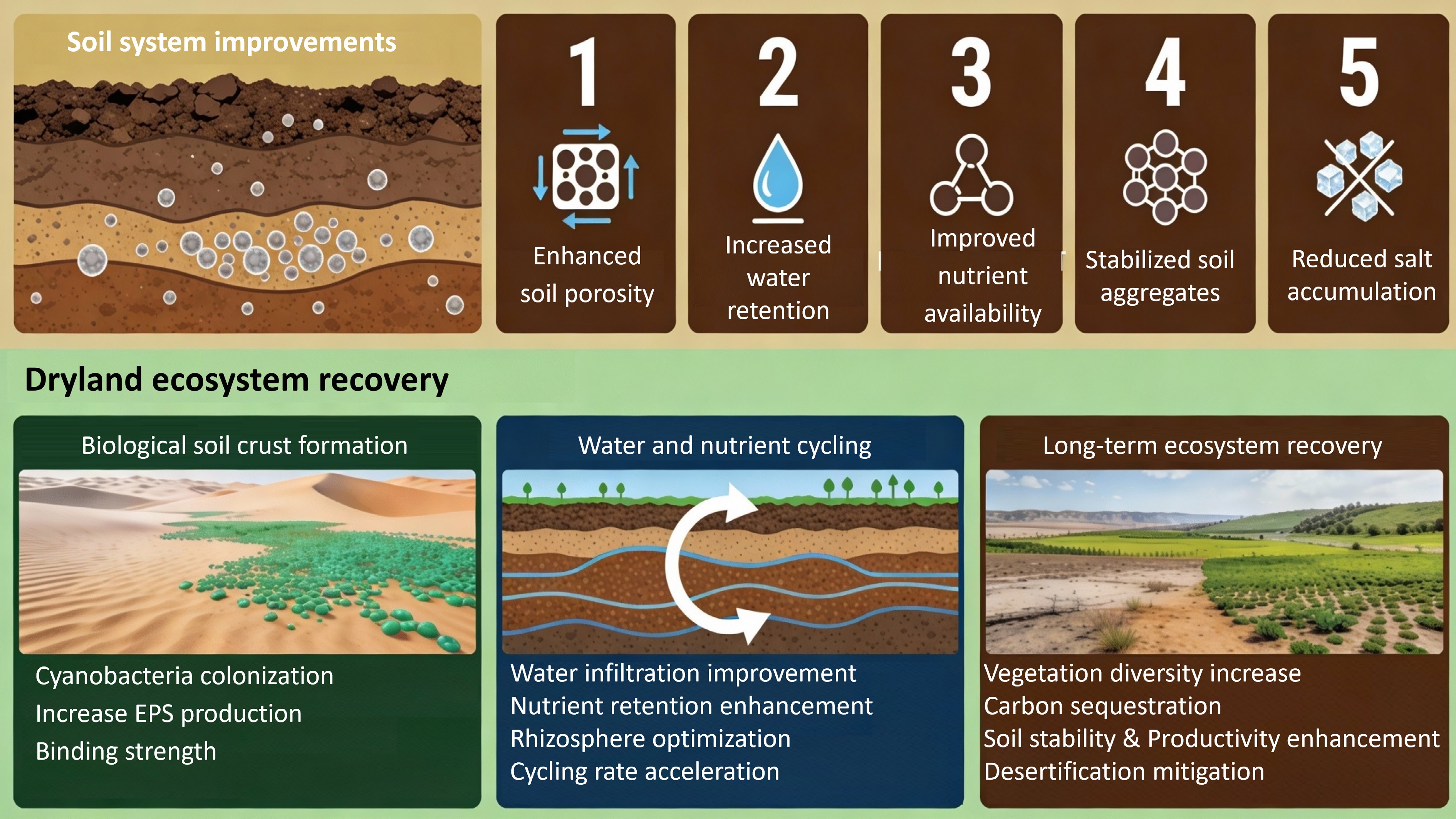

Biochar enhances soil structure by promoting aggregation and reducing compaction. As a physical conditioner, it aids in forming stable soil aggregates, leading to the development of macro- and micro-aggregates. These improvements increase soil porosity and aeration, facilitating better root penetration and water infiltration[87,88]. The effect of biochar on soil hydraulic conductivity is dependent on soil water content, providing valuable insights into how biochar influences soil hydrological properties. Enhanced water infiltration and drainage reduce the risk of waterlogging and increase oxygen availability to plant roots[89]. Biochar also helps mitigate soil hydrophobicity, improving infiltration and water distribution[90].

Salt stress mitigation mechanisms

-

To mitigate excessive soil salinity, plant scientists utilize various techniques, including sub-soiling, sand mixing, seed bed preparation, and salt scraping[91]. Modern agronomic practices such as the application of hydrophilic polymers, gypsum, sulfuric acid, green manuring, humic substances, olive mill wastes, farmyard manures, improved irrigation systems, and cultivation of salt-tolerant crops are also employed[92,93].

Biochar application has been widely reported to improve soil quality under saline conditions through multiple, interrelated mechanisms. One of the most important effects is its capacity to immobilize excess sodium ions in the soil matrix, thereby facilitating the release and uptake of essential mineral nutrients and alleviating osmotic stress in the root zone. Previous studies have demonstrated that biochar amendments can significantly reduce exchangeable sodium levels and lower the sodium-to-potassium (Na+/K+) ratio in saline soils, resulting in a more balanced and favorable rhizospheric environment for plant development[94]. In addition, biochar influences nutrient cycling by enhancing the retention and availability of essential elements, while simultaneously limiting the bioavailability of potentially toxic ions commonly associated with saline conditions.

Improvements in soil chemical and physical properties following biochar addition are closely reflected in plant performance under salinity stress. Numerous studies have demonstrated that biochar enhances plant tolerance to salinity by stimulating antioxidant defense systems and reducing oxidative damage[95,96]. Biochar-amended soils have been associated with improvements in key morphological traits, including seedling establishment, leaf expansion, shoot and root biomass accumulation, plant height, dry matter production, and final yield under saline stress conditions[95]. Moreover, biochar contributes to improved osmotic regulation by increasing soil water-holding capacity and enhancing carbon dioxide assimilation. These changes promote higher transcriptional activity, increased stomatal conductance, and improved photosynthetic efficiency[97]. Collectively, these responses highlight the integrated nature of soil–plant interactions and underscore the role of biochar as a soil amendment that mediates physiological resilience through improvements in soil quality.

Nanobiochar, due to its nanoscale dimensions and increased surface area, effectively alleviates salinity stress in plants and soils through several mechanisms. Its increased porosity and surface area enhance its ability to adsorb ions, particularly chloride and sodium, which are the dominant soluble salts in saline soils. The simultaneous removal of both Na+ and Cl− is essential because each ion creates distinct phytotoxic effects: sodium causes osmotic stress and interferes with potassium uptake, while chloride accumulates in plant tissues to toxic levels independent of sodium presence[98,99]. This adsorption capability effectively lowers the concentration of detrimental salts in the rhizosphere, thereby minimizing osmotic stress on plants. Additionally, nano-biochar can improve nutrient cycling dynamics in saline soils by enhancing nutrient availability. It adsorbs and retains essential nutrients, preventing their leaching and creating a favorable microenvironment that enhances nutrient uptake by plants. This process mitigates the adverse effects of salinity by improving nutrient absorption[99].

Slow-release nutrient systems

-

Biochar produced from biomass is not only a carbon-rich material but also contains appreciable quantities of essential macro- and micro-nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulfur, manganese, copper, zinc, iron, and ash. This nutrient-rich composition underpins its growing use as an organic soil amendment and fertilizer[100]. The use of biochar as a nutrient carrier has opened new avenues for the development of slow-release biofertilizers. For example, nitrogen use efficiency has been shown to increase by up to 64.3%, while nitrogen leaching losses and surface migration are substantially reduced, leading to improved crop growth and nutrient availability over time[100,101].

At the nanoscale, nanobiochar has demonstrated considerable potential as a slow-release nutrient source, contributing to improved soil fertility and enhanced crop productivity[34]. Yield and growth improvements observed in rice systems have been largely attributed to synergistic interactions between nanobiochar and mineral fertilizers, resulting in increases in plant height, tiller number, and overall biomass[102,103]. These findings highlight the effectiveness of nanobiochar–fertilizer combinations as efficient nutrient delivery systems in intensive cropping systems.

The superior performance of nanobiochar is closely linked to its physicochemical characteristics. Its large specific surface area and charged surface facilitate the adsorption and subsequent availability of nutrients following fertilization[104,105]. Oxygen-containing functional groups on nanobiochar surfaces further enhance the adsorption of ammonium and ammonia, improving nitrogen retention and reducing losses through leaching and volatilization[102]. The porous structure of nanobiochar also enables the capture and retention of nitrate ions, limiting their displacement by irrigation or rainfall[106]. Through these mechanisms, nanobiochar improves key soil nitrogen processes such as mineralization and nitrification, ensuring a more consistent and readily available nitrogen supply for plant uptake and ultimately supporting higher productivity[107]. In parallel, improvements in soil structure and microbial diversity further enhance nutrient cycling and availability[108].

Beyond conventional fertilizers, biochar-based nanocomposites derived from agricultural wastes, such as corn residues, have been developed to provide slow-release macro- and micronutrients to plants[77]. These approaches contribute to sustainable waste management by transforming agricultural by-products into value-added fertilizers, while also mitigating nutrient leaching associated with traditional fertilization practices[109]. More recently, hydrogel-based biochar composites have been introduced as environmentally safe materials capable of retaining moisture and nutrients, thereby supporting eco-friendly and resource-efficient agricultural production systems[110]. Despite these advances, further research remains necessary to fully evaluate the capacity of biochar-derived fertilizers to simultaneously immobilize heavy metals while providing controlled and sustained nitrogen release under diverse soil and environmental conditions.

Microbial diversity and activity

-

Nanobiochar has emerged as a promising option for soil enhancement, enzyme activity promotion, and pollutant adsorption due to its porous structure and unique physical and chemical properties. These properties, including a high surface area, hydrophobicity, and microporosity, enable nanobiochar to effectively adsorb pollutants such as heavy metals, herbicides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and polychlorinated biphenyls[27]. Additionally, nanobiochar's alkaline nature makes it effective in neutralizing soil acidity, broadening its applications in agriculture and environmental management by improving soil quality.

An investigation of nanobiochar's effects on tobacco rhizosphere microbiology[100] demonstrated substantial increases in bacterial and fungal diversity alongside shifts in microbial community composition. These shifts coincided with elevated soil enzyme activities (catalase, invertase, phosphatase) and enhanced microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen pools. Application rates of 3% nanobiochar proved optimal for maximizing metabolic activity and community diversity in tobacco-cultivated soil, with statistically significant positive correlations between enzymatic activity and microbial richness[100].

In a study conducted in a rubber tree plantation in Northeast Thailand, increasing doses of nanobiochar were found to influence soil pH, nutrient content, and microbial communities, with fungal communities being more affected than bacterial communities[111]. Nanobiochar impacts soil microbial diversity and function through both abiotic processes and modifications to the soil's physical environment. Changes in pH and oxidation potential due to nanobiochar can affect microbial population structure and activity, as well as nitrogen and carbon adsorption dynamics. Nanobiochar's porous structure provides a microhabitat for soil fungi and bacteria, supplying essential organic components and minerals. This structure supports microbial growth, enhancing soil nutrient content and altering community structures[112]. Understanding nanobiochar's effects on microbial populations and functions is crucial for developing systems that maintain soil health and improve degraded soils, ultimately protecting plants[112].

-

The environmental applications of macro-biochar have been extensively studied and documented by various researchers. However, nanobiochar is now being explored for numerous environmental purposes, including phytoremediation, carbon sequestration, and energy generation, as well as applications in waste management, wastewater treatment, and pollutant removal.

Nanobiochar demonstrates effective sorption properties for removing pollutants such as pesticides, steroid hormones, pharmaceuticals, and toxic metals[113]. These micropollutants pose significant risks to human health and the environment, primarily spreading through improper wastewater discharge, waste disposal, and agricultural chemical use. Nanobiochar and biochar modified with nanominerals exhibit exceptional adsorption capabilities due to their unique characteristics compared to conventional biochar[53]. Furthermore, by adsorbing toxic chemicals like pesticides and immobilizing metals, nanobiochar contributes to remediating pollution that can lead to severe environmental and health issues. Therefore, nanobiochar is increasingly recognized as a promising agent for the bioremediation of a wide range of contaminants.

The superior environmental performance of nanobiochar compared to bulk biochar fundamentally derives from enhanced physicochemical properties that create multiple coordinated remediation mechanisms[114]. Nanobiochar exhibits dramatically increased specific surface area and porosity, generating exponentially more adsorption sites and reactive functional groups (hydroxyl, carboxyl, and phenolic groups) capable of binding diverse pollutants[115]. The primary mechanism for nanobiochar interacting with heavy metals and organic pollutants is adsorption, enabled by surface functional groups including lactone, carboxyl, and hydroxyl moieties that increase its ability to adsorb and immobilize various contaminants through multiple simultaneous pathways: interactions with aromatic organics (e.g., pesticides, pharmaceutical compounds), coordination bonding with metal cations, and pore-filling mechanisms[114]. For heavy metal removal, aged nanobiochar exhibits a higher surface area and more functional groups favorable for binding cadmium through enhanced chemisorption and physical adsorption processes such as hydrogen bonding and pore filling, with chemical ageing producing the most significant effect[116]. Critically, the synthesis method determines the primary remediation mechanism: ball milling and mechanical grinding increase surface area and porosity suitable for contaminant immobilization, while chemical modifications incorporating metal oxides enable catalytic degradation pathways in addition to adsorption[115,117]. Notably, magnetic nanobiochar modifications incorporating iron nanoparticles impart magnetic properties, enabling facile recovery of treated nanobiochar from water and supporting multiple regeneration cycles. These integrated mechanisms—combining adsorption, absorption, precipitation, complexation, and catalytic transformation—position nanobiochar as a multifunctional environmental remediator substantially outperforming conventional biochar across diverse contaminant classes (heavy metals, organic pollutants, pharmaceuticals) and environmental matrices (contaminated water and soil)[118].

Wastewater contaminant removal

-

Water contamination by persistent heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu) represents a major environmental and public health hazard due to bioaccumulation and non-degradability. The most widely accepted methods for removing heavy metals include adsorption, ion exchange, and chemical precipitation[119]. Among these, adsorption from aqueous solutions or effluents has gained popularity due to its economic feasibility.

Conventional remediation technologies, including activated carbon, zeolite, iron oxide, and silica gel-based adsorbents, exhibit significant practical limitations, including oxidative instability, suboptimal adsorption kinetics, insufficient selectivity, and prohibitive costs[120]. These constraints have motivated the investigation of nanobiochar-based alternatives. Recent research has focused on synthesizing different types of nanobiochar to enhance its adsorption capacity for aqueous and ionic pollutants[121,122]. Studies have demonstrated significant improvements in wastewater treatment using biochar nanocomposites, highlighting their removal efficiencies and adsorption capacities.

Heavy metals such as cadmium, arsenic, copper, and chromium contribute significantly to water pollution, primarily due to their adsorption and degradation by nanobiochar and biochar-based nanocomposites. A study by Liu et al.[99] demonstrated that transforming pristine magnetic biochars into ball-milled magnetic nanobiochar derived from wheat straw markedly improved the removal efficiency of tetracycline and mercury from contaminated irrigation water. Recent studies have shown that modifying biochar with hydroxides, metal oxides, magnetic iron particles, and other functional nanoparticles has enabled researchers to harness its potential for wastewater treatment[123,124]. These biochar-based nanocomposites have proven highly efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective for the bioremediation of wastewater by adsorbing toxic metals and other contaminants.

Biochar-enhanced phytoremediation

-

Biochar is widely recognized for its adsorption capabilities and has been utilized to remove pollutants effectively. Additionally, various forms of nano-carbon materials, such as carbon black, activated carbon, or engineered carbon nanomaterials, have demonstrated a high ability to adsorb natural organic matter. Research has shown that contaminants like heavy metals, pharmaceuticals, and dyes can be effectively removed using biochar, with nanobiochar proving particularly efficient. Table 3 summarizes the effectiveness of different nanobiochar composites. Furthermore, numerous studies have confirmed that biochar nanocomposites possess a significant capacity to eliminate major heavy metal contaminants, including arsenic, lead, copper, chromium, and cadmium, as well as other pollutants such as toxic chemicals, dyes, and antibiotics. For instance, as shown in Table 3, a study by Li et al.[125] reported that ZnO/ZnS-modified nanobiochar demonstrated high potential for adsorbing Cr6+, Cu2+, and Pb2+.

Table 3. Comprehensive assessment of pollutant elimination through adsorption using nanobiochar and biochar nanocomposites

Pollutants removed Pollutant category Composite composition Adsorption mechanism Application scope Ref. Pb2+, Cu2+, Zn2+ Heavy metals Biochar + hydroxyapatite mineral coating Chelation bonding with phosphate groups; ion exchange Industrial wastewater treatment; Contaminated water remediation [126] Cr6+, Cu2+, Pb2+ Heavy metals (hexavalent chromium) Biochar integrated with zinc oxide and zinc sulfide nanoparticles Redox reduction of Cr6+ to Cr3+; electrostatic adsorption; complexation Chromium-contaminated wastewater; Metal-rich industrial effluents [125] Pb2+ Heavy metal (lead) Biochar surface coated with manganese oxide nanoparticles Oxidation-adsorption synergy; manganese oxide sorption sites; ion exchange Lead contamination in aqueous solutions; Mining wastewater [69] Metformin hydrochloride (MFH) Pharmaceutical pollutant (antidiabetic drug metabolite) Biochar treated with sodium hydroxide creating alkaline surface Electrostatic attraction to basic sites; hydrogen bonding; pore filling Pharmaceutical wastewater [127] Tetracycline and Hg2+ Antibiotic + toxic metal Biochar with embedded magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4 or CoFe2O4) Magnetic adsorption; surface functional group binding; chelation Antibiotic-contaminated agricultural runoff; Mercury-contaminated water; Easy magnetic recovery [128] Fluoride (inorganic) Inorganic anion pollutant Biochar derived from corn stover with iron oxide modification Ion exchange mechanism with iron oxide sites; adsorption to hydroxyl groups Fluoride-contaminated groundwater; Industrial fluoride-containing wastewater [129] Cu2+, Cd2+, Pb2+ Multiple heavy metals Biochar surface treated with potassium permanganate creating nanometal oxide sites Oxidative adsorption from permanganate sites; ion exchange; complexation Multi-metal contaminated solutions; Electroplating industry wastewater [130] Phosphate (inorganic) Nutrient ion pollutant (eutrophication control) Biochar with magnesium oxide and magnesium hydroxide nanoparticles Precipitation reaction with magnesium species; Lewis acid-base interactions Nutrient-rich wastewater treatment; Eutrophication prevention; Agricultural runoff [131] Nanobiochar-BSC integration for drylands

-

The intersection of nanotechnology and ecological restoration represents a paradigm shift in dryland management. While traditional restoration efforts often rely on the passive natural recovery of BSCs—a process that can take decades and is prone to failure under hyper-arid conditions—the integration of carbon-based amendments offers a pathway to active, accelerated 'bio-geo-engineering'. Although existing research has primarily documented the benefits of bulk biochar in facilitating BSCs establishment[30,31,132], the theoretical properties of nanobiochar suggest that it could overcome the limitations of macroscopic amendments. By creating a hybrid material system with exponentially higher surface area and colloidal reactivity, nanobiochar-amended BSCs are hypothesized to transcend the performance of either component individually. This section explores the future trajectory of this synergy, proposing how nanobiochar could facilitate the emergence of resilient, self-sustaining soil skins in degraded drylands more effectively than conventional methods.

Bio-ink carriers and protection

-

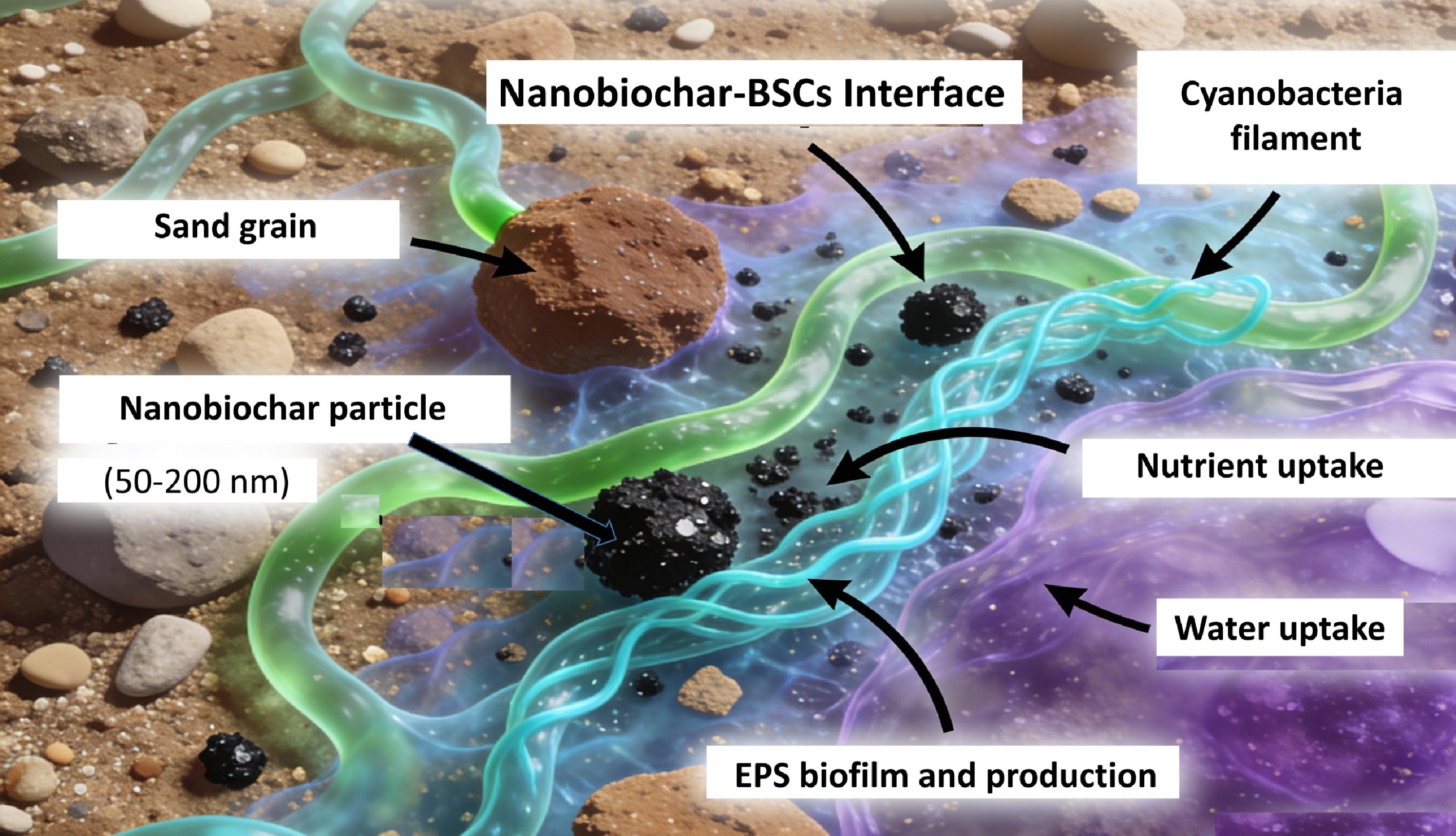

A major constraint in dryland restoration is the high mortality of inoculated cyanobacteria, which are often destroyed by wind erosion and intense UV radiation before they develop protective pigments or filament networks[133,134]. While bulk biochar has been shown to provide physical shelter for microbial colonization[40], a promising direction for future work is the development of nanobiochar-based 'bio-inks' for precision hydro-seeding. In this proposed approach, nanobiochar particles (50–200 nm) would act as protective colloidal carriers for cyanobacterial inocula. Their superior surface area-to-volume ratio compared to bulk biochar suggests they could promote the rapid formation of stable organo-mineral aggregates immediately upon application.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, this microscopic interaction is central to the hypothesized method's effectiveness because nanobiochar's enhanced surface area and nanoscale pore structure create mechanistic advantages for cyanobacterial colonization. Nanobiochar particles possess higher surface area-to-volume ratios, enabling stronger electrostatic anchoring of cyanobacterial cells and more rapid stabilization of soil micro-aggregates. The nanoscale pores reduce diffusion distances for essential nutrients and water, supporting rapid metabolic activity during critical early establishment phases. Additionally, nanobiochar's superior capacity to bind and concentrate EPS creates stronger bio-cement for aggregate stability, addressing wind erosion—a dominant failure mechanism in arid restoration. Unlike macroscopic biochar granules, which simply mix with soil, nanobiochar particles position themselves between sand grains and filamentous cyanobacteria, functioning as electrostatic micro-anchors within the EPS biofilm matrix. This integrated three-component assembly creates a refined micro-niche environment that provides mechanical stability, enhances water retention, and buffers early cyanobacterial cells from UV stress and desiccation during the critical establishment phase. Furthermore, nanobiochar-amended formulations are expected to maintain matric water at levels usable by cyanobacteria more effectively than bulk amendments, prolonging the metabolic window for photosynthesis and EPS secretion processes essential for initiating biological soil crust formation.

Accelerating microbial community assembly

-

Future research will likely focus on nanobiochar not just as a physical anchor, but as a highly efficient biochemical catalyst for the 'cyanosphere'—the consortium of heterotrophic bacteria that supports cyanobacterial growth. Bulk biochar is already utilized as a carrier for beneficial microbes, but nanobiochar offers a superior platform due to its increased loading capacity. By engineering nanobiochar to be pre-loaded with specific signaling molecules or limiting nutrients (e.g., phosphorus), restorationists could selectively recruit beneficial heterotrophs (Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria) with greater precision than is possible with macroscopic carriers. This synergy could transform the restoration process from a linear accumulation of biomass to an exponential assembly of community function. Field trials using biochar carriers suggest that co-inoculation strategies can compress succession timelines; shifting to nanobiochar could theoretically accelerate this further, potentially reducing recovery times in even nutrient-depleted substrates like mining tailings.

Climate stress tolerance and stability

-

Perhaps the most critical advantage of transitioning from bulk to nanobiochar is the potential for emergent resilience to climate change stressors[135], particularly in cold deserts. Evidence indicates that biochar-amended soils exhibit improved resistance to freeze-thaw cycles, a major cause of crust destabilization[136]. Nanobiochar is expected to amplify this effect through 'thermal buffering' and structural reinforcement. Its nanoscale pores can better accommodate the volumetric expansion of freezing soil water without disrupting the aggregate structure, while its uniform dispersion provides a darker albedo that increases surface temperatures. This would create a 'bio-composite armor' capable of withstanding erosion forces that would strip away natural crusts—an application particularly relevant for alpine steppes facing increasing climate variability.

Carbon sequestration potential

-

Finally, the widespread application of nanobiochar-BSC systems presents a scalable opportunity for carbon sequestration. This approach offers a 'double-locking' mechanism for carbon storage: the recalcitrant, aromatic carbon of the nanobiochar itself (stable for centuries) and the labile, photosynthetically fixed carbon trapped within the mineralized crust matrix. While biochar is a known carbon sink, nanobiochar's potential for deeper integration into the mineral matrix suggests it may be less susceptible to oxidative loss. As global carbon markets evolve, quantifying this sequestration potential could monetize dryland restoration, providing the economic model necessary to fund landscape-scale initiatives.

-

The growing interest in nanobiochar is primarily attributed to its distinctive physicochemical properties associated with particle size, including a higher specific surface area[115], reduced hydrodynamic radius and more negative zeta potential[64], increased abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups, and the presence of carbon defects relative to pristine biochar[137]. These characteristics enhance the reactivity of nanobiochar and underpin its strong adsorption capacity for trace metals and organic contaminants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons[34], which has promoted its application in wastewater treatment and contaminant immobilization. However, these same properties also introduce a range of limitations and potential adverse effects that require careful evaluation[115].

At the soil scale, both biochar and nanobiochar can alter soil physical structure in ways that are strongly dependent on soil texture, application rate, and surface chemistry. Due to their extremely small size and high surface reactivity, nanobiochar particles are capable of migrating into soil pore spaces, which may reduce macroporosity and restrict gas exchange and root penetration when applied at excessive rates[138]. In addition, surface chemical characteristics inherited from feedstock selection and pyrolysis conditions may enhance hydrophobic behavior at the nanoscale. This water repellency can disrupt aggregate bonding mechanisms, increasing the susceptibility of soil aggregates to slaking and breakdown during repeated wetting and drying cycles. Consequently, improvements in soil structure observed at low application rates may shift toward compaction and structural instability under less controlled conditions.

Alterations in soil structure are closely linked to changes in soil water dynamics, where the effects of nanobiochar are often contradictory[139]. While the internal porosity and surface functional groups of nanobiochar can increase soil water-holding capacity, particularly in coarse-textured soils, surface-applied nanobiochar may simultaneously accelerate moisture loss. In some cases, nanobiochar forms thin surface layers that promote capillary rise and rapid evaporation rather than sustained moisture storage. Moreover, the high mobility of nano-sized particles can modify hydraulic conductivity and promote preferential flow pathways, resulting in uneven water distribution within the soil profile[139]. As a result, enhanced soil water retention does not always translate into improved plant water availability. A study by Chen et al.[140] reported that nanobiochar increased water repellency and decreased soil water retention, a discrepancy that may be largely attributed to differences in raw materials and preparation methods. Another contributing factor may be the redistribution of soil pore structure caused by nanobiochar entering small- and medium-sized pores, leading to the formation of zigzagging and complex water flow channels[141].

In addition to physical and hydrological effects, high application rates of biochar and nanobiochar may negatively influence soil biological properties. Excessive inputs can result in the accumulation of toxic compounds or the formation of physical barriers that impede microbial growth, ultimately reducing microbial abundance and diversity[142]. The presence of potentially toxic components within biochar and nanobiochar may further suppress bacterial populations[143]. These effects may also be linked to reductions in soil organic carbon availability, as discussed earlier, while elevated C/N ratios in nanobiochar can restrict carbon metabolism among microbial communities, thereby exerting additional pressure on microbial diversity[99].

Beyond soil-related effects, the production of nanobiochar raises important economic and energy concerns. The conversion of bulk biochar into nano-sized material typically relies on energy-intensive post-processing techniques such as ball milling, chemical oxidation, or ultrasonication. These processes substantially increase production costs and embodied energy compared with conventional biochar, limiting the feasibility of large-scale agricultural or restoration applications[28]. From a life-cycle perspective, the environmental benefits attributed to nanobiochar may be offset by its high energy demand unless its performance clearly exceeds that of bulk biochar, thereby confining its use primarily to specialized or high-value applications.

Given that both bulk biochar and nanobiochar are increasingly applied in agriculture and soil remediation[144], it is essential to assess their impacts on plants and diverse groups of organisms. Physicochemical characterization and contaminant profiling alone are insufficient for evaluating the environmental risks associated with nanobiochar[145], due to the complex interactions between nanobiochar, environmental matrices, and biological systems, as well as the dynamic nature of contaminant release and particle transport.

-

This review highlights the rapidly expanding role of nanobiochar and biochar-based nanocomposites in addressing critical agricultural and environmental challenges. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that nanobiochar can substantially enhance plant performance by improving nutrient cycling, alleviating salinity stress, and increasing fertilizer use efficiency. These benefits arise not only from its unique physicochemical properties but also from its capacity to influence the soil–plant–microbe continuum. In particular, nanobiochar-induced shifts in microbial activity and community structure play a central role in sustaining long-term soil fertility, ecosystem functioning, and resilience.

Beyond agronomic applications, nanobiochar exhibits strong environmental remediation potential due to its high sorption capacity associated with its large surface area and fine pore structure. This enables effective immobilization of a wide range of organic and inorganic contaminants in soils, aquatic systems, and even atmospheric environments. When coupled with its role in waste valorization and its contribution to enhanced crop productivity, these multifunctional attributes position nanobiochar as a key material supporting sustainable development goals.

An emerging and particularly promising frontier identified in this review is the application of nanobiochar in dryland restoration, especially through its interaction with biological soil crusts. Synthesis of current studies suggests that nanobiochar can act as an effective nucleation substrate for BSC initiation, helping to overcome constraints such as wind erosion, nutrient limitation, and rapid moisture loss in arid ecosystems. By promoting cyanobacterial colonization and strengthening the physical integrity of desert surface soils, nanobiochar facilitates the development of a stable bio-composite matrix. In this context, nanobiochar transcends the role of a conventional soil amendment and emerges as a strategic tool for bio–geo-engineering, offering a scalable, nature-based approach to combating desertification and enhancing long-term soil carbon sequestration.

To fully realize the potential of nanobiochar across agricultural and ecological systems, several research priorities must be addressed. First, mechanistic studies are required to unravel the complex and often non-linear interactions among nanobiochar, soil mineralogy, and microbial networks. Such knowledge is essential for the design of precision-engineered nanobiochar formulations tailored to specific soil types and degradation levels. Second, greater emphasis should be placed on optimizing biochar–organic and biochar–microbial consortia, particularly co-inoculation strategies that integrate nanobiochar with cyanobacteria, mycorrhizal fungi, or other beneficial microorganisms to enhance restoration success in nutrient-poor drylands.

Third, scaling up nanobiochar production remains a critical challenge. Advances in energy-efficient manufacturing pathways such as optimized ball milling, hydrothermal carbonization, and controlled pyrolysis are needed to improve product consistency, reduce energy demand, and enable landscape-scale applications. Fourth, the functional scope of nanobiochar extends beyond soil systems into emerging technological domains, including energy storage materials such as supercapacitor electrodes and the development of 'smart' soil sensors that integrate nanomaterials with real-time environmental monitoring technologies.

Finally, long-term ecological evaluations are indispensable for the responsible deployment of nanobiochar. Comprehensive field-based studies examining particle stability, mobility, trophic transfer, and ecosystem-level impacts over multi-year to decadal timescales are necessary to ensure environmental safety and regulatory acceptance. Addressing these knowledge gaps will allow the scientific community to harness the full versatility of nanobiochar, advancing innovative solutions for sustainable agriculture, environmental remediation, and the restoration of fragile dryland ecosystems.

This work is supported by Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

-

The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft, and approval for the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

No funding was received for conducting this study.

-

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Nanobiochar outperforms bulk biochar in soil remediation due to superior surface area and reactivity.

Nanobiochar acts as an efficient carrier for slow-release fertilizers, reducing nitrogen leaching.

Ball milling offers a sustainable, solvent-free pathway for synthesizing highly functionalized nanobiochar.

Application of biochar nanocomposites alleviates salinity stress in crops by regulating osmotic balance and ion homeostasis.

It acts as a bio-ink anchor, enabling pioneer cyanobacteria to colonize unstable dryland soils.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Salem H. 2026. Nanobiochar as a multifunctional amendment for coupled water-soil-biota systems: applications in agricultural production, environmental remediation, and arid ecosystem restoration. Biochar X 2: e009 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0026-0008

Nanobiochar as a multifunctional amendment for coupled water-soil-biota systems: applications in agricultural production, environmental remediation, and arid ecosystem restoration

- Received: 01 December 2025

- Revised: 10 January 2026

- Accepted: 16 January 2026

- Published online: 13 February 2026

Abstract: Nanobiochar, engineered carbon nanoparticles derived from biomass, represents an emerging interface between nanotechnology and environmental engineering. Produced through mechanical, thermal, and hydrothermal processes, nanobiochar exhibits a markedly higher specific surface area, enhanced surface reactivity, and improved sorption capacity relative to conventional bulk biochar. This review synthesizes recent advances in nanobiochar production pathways, physicochemical characteristics, and the mechanistic controls governing its functional performance across environmental systems. In agricultural applications, nanobiochar has been shown to enhance plant growth by improving nutrient cycling, mitigating salinity stress through ionic immobilization, reducing nitrogen losses via slow-release fertilizer delivery, and fostering beneficial soil microbial communities. Beyond agroecosystems, nanobiochar-based materials demonstrate strong potential for heavy metal immobilization, organic contaminant adsorption, and wastewater treatment. The review further highlights an emerging and largely unexplored frontier in dryland restoration, where nanobiochar may interact with biological soil crusts (BSCs). Preliminary evidence suggests that, when used as a carrier for pioneer cyanobacteria, nanobiochar could contribute to substrate stabilization, potentially influence exopolysaccharide production, and affect soil moisture retention under arid conditions. Considering the global extent of drylands, nanobiochar–BSC systems may offer an exploratory pathway for restoration with possible implications for long-term carbon sequestration. Nevertheless, challenges related to energy-intensive production and large-scale deployment remain and require careful optimization. Overall, this review elucidates key design–function relationships underlying nanobiochar performance, emphasizes the need for responsible upscaling, and identifies critical research priorities for its application in sustainable agriculture, environmental remediation, and ecosystem restoration.