-

With the intensification of pig farming in China, environmental factors and feed play significant roles in the formation of free radicals in pigs. When the production of free radicals exceeds the antioxidant system's reductive capacity, it disrupts redox balance and triggers oxidative stress[1]. Oxidative stress not only induces lipid peroxidation of phospholipids, damages proteins, and DNA, but also contributes to intestinal health[2]. This imbalance leads to elevated levels of free radicals and/or reduced antioxidant defenses against reactive oxygen species (ROS). Notably, increased ROS levels and decreased antioxidant enzyme activity led to the activation of inflammatory pathways, such as the NF-κB pathway[3]. A significant amount of free radicals can be generated during nutrient absorption and metabolism, negatively affecting the intestinal mucosa[4]. The body's endogenous antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and catalase (CAT), help to reduce ROS in the cellular fluid[5]. Furthermore, oxidative stress and inflammation are closely linked to the growth and development of animals during both pre-natal and post-natal stages, influencing productivity in the livestock industry[6]. Therefore, enhancing the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities of pigs through nutritional interventions is crucial for improving both animal health and pork quality.

Vinegar residue (VR) is a common agricultural byproduct generated during vinegar production[7]. It is characterized by its high nutritional value, low cost, and renewable properties, making it widely applicable in the food industry. China has abundant VR resources, and effectively utilizing them could help mitigate feed supply shortages in the livestock industry, while also reducing environmental pollution associated with the vinegar brewing process[8]. From both resource development and environmental protection perspectives, the efficient use of VR is significant to the growth of the livestock sector. VR contains malic acid, acetic acid, and lactic acid, which act as dietary acidifiers that lower intestinal pH, enhancing pepsin activity and nitrogen retention[9,10]. Additionally, the high fiber content of VR is believed to positively impact gut microbiota, promoting microbial colonization and growth, which leads to the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and anti-ROS molecules such as glutathione, which offer significant health benefits[11].

Although numerous studies have demonstrated the positive effects of vinegar residue (VR) in various animal species and its widespread use in animal production, its potential in intensive farming remains under-utilized[9,12,13]. To fully exploit VR as a feed ingredient, further research is necessary to investigate its efficient use across different animal species and physiological stages. Accordingly, three experiments were conducted to evaluate the nutritional value of VR from different sources, and its potential application in growing pigs.

-

Ten sources of vinegar residue were obtained from rice (VR1, VR2, VR3, and VR4), wheat (VR5 and VR6), sorghum (VR7 and VR8), and wheat bran (VR9 and VR10), respectively. The general steps for producing vinegar residue are as follows. Raw materials (rice, wheat, sorghum, and wheat bran) are pulverized, steamed, and mixed with vinegar starter (Pei) for alcohol fermentation. Subsequently, supplementary materials including rice husks and sorghum husks are incorporated for acetic acid fermentation, lasting approximately 20 d with daily stirring, followed by final product extraction through soaking and filtration processes that yield vinegar liquid and leave vinegar residue (VR) as the solid byproduct. Twenty two healthy Duroc × Landrace × Large White three-way crossbred castrated boars, aged 80 d and weighing 20.15 ± 1.25 kg, were randomly allocated to 11 dietary treatments (Supplementary Table S1) in a randomized complete block design (three blocks, two pigs/diet/block; six replicates/diet), stratified by initial body weight. Animals were housed individually in stainless steel metabolism crates (1.4 m × 0.7 m × 0.6 m) within a climate-controlled facility (24 ± 2 °C), with free access to water and fed 4% of initial body weight daily. Feed was equally divided into three timed meals (08:00, 14:00, 16:00), with precise intake monitoring. The 10-d trial included a five-day dietary adaptation phase followed by 5 d of fecal/urine collection using standardized protocols, with subsequent processing as described previously[14].

Experiment 2: pig feeding experiment

-

A total of 50 growing pigs [Duroc × Large White × Landrace; Initial body weight (BW) = 20.3 ± 0.3 kg] were randomly assigned to five treatment groups in a randomized complete block design, with 10 replicates and one pig per pen. The pigs were fed either a control (CON) diet or a CON diet supplemented with vinegar residue from rice, wheat, sorghum, and wheat bran [VR-R (VR1), VR-W (VR6), VR-S (VR7), and VR-WB (VR9)], based on effective energy values. Pigs in the VR groups were fed a basal diet supplemented with 5% VR-R, VR-W, VR-S, or VR-WB, respectively. The dose of VR was based on a previous study[15]. The experimental diet (corn-soybean meal base) was formulated to meet NRC (2012) swine nutrition guidelines (Supplementary Table S2). Animals were maintained in individual pens with continuous water access and received timed feedings (08:00, 13:00, 18:00) during the 35-d study period.

Sample analyses

Experiment 1: digestibility and concentration of energy

-

All chemical analyses were performed in duplicate. The chemical composition of ingredients, diets, feces, and urine samples were determined for gross energy (GE) using Bomb calorimetry (Parr 6300), quantified gross energy in all biological matrices. Proximate analyses included DM (AOAC 930.15), ash (AOAC 942.05), and starch (AOAC 979.10 glucoamylase method) determinations. Mineral profiling involved dual preparation: Dry ashing (AOAC 942.05) at 600 °C/4 h and EPA 3050B (2000) wet digestion prior to ICP-OES measurement. Dietary fiber fractions (IDF/SDF) were characterized via AOAC 991.43, with TDF derived from their summation. Phytic acid quantification followed the spectro-photometric protocol previously reported by Plaami[16].

Experiment 2: pig feeding experiment

Measurements of the anti-oxidative enzyme activity, oxidative metabolite, and cytokine concentration in the plasma

-

Following the experimental period, swine underwent terminal body weight measurement prior to humane euthanasia via intravenous sodium pentobarbital administration (200 mg/kg BW). Postmortem procedures included intracardiac blood collection and ileal sampling (mid-ileum digesta and mucosa), with biological specimens flash-frozen at −80 °C for preservation. Plasma inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α) were quantified using species-validated ELISA kits (R&D Systems) per standardized protocols. Concurrently, plasma oxidative stress markers (GSH-Px, SOD, CAT, GSH, MDA) were assayed through enzymatic colorimetric methods (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute kits).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), protein extraction, and immunoblot analysis

-

Mucosal samples (0.5 g each) were thawed and processed for RNA extraction, with 1 μg of total RNA reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser according to the manufacturer's protocol. Target gene mRNA expression levels were quantified via the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method, normalized against the β-actin housekeeping gene. Corresponding primer sequences are detailed in Supplementary Table S3. The expression of target proteins, Nrf2, and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), was analyzed by Western blotting, with β-actin as the internal reference.

Analysis of the bacterial community and concentrations of short-chain fatty acids in the digesta samples

-

Genomic DNA extraction, microbial community profiling, and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) analysis followed established protocols[17]. Briefly, DNA was isolated from 0.2 g of intestinal contents via bead-beating (Biospec Products mini bead beater). Microbial OTUs were clustered de novo at 97% similarity, and group-specific bacterial taxa were identified through LEfSe (linear discriminant analysis effect size). SCFA quantification in colonic digesta was performed by gas chromatography (Shimadzu GC-14B) under standardized conditions: column at 110 °C, injector/detector at 180 °C.

Calculation and statistical analyses

-

In experiment 1, the DE and ME of the VR diets were calculated as described by Adeola[18]. The apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) of nutrients was calculated using the method: ATTD (%) = (GEi − GEf)/GEi × 100, where:GEi = Diet GE (kcal DM) × Feed consumption (5-d collection), GEf = Fecal GE (kcal DM) × Total fecal dry mass.

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0-23.0 (IBM Corp.). Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SE. Normal distributions were compared through one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons, whereas non-parametric datasets (e.g., microbiota) were evaluated via Kruskal-Wallis tests, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

-

In this study, vinegar residues (VR) from 10 distinct regions were collected, using primary raw materials including rice, wheat, sorghum, and wheat bran. These samples were analyzed for their nutritional composition, amino acid profiles, and mineral contents. As shown in Table 1, VR7 (derived from sorghum) exhibited the highest crude protein content at 15.63%, while VR10 (derived from wheat bran) had the lowest crude protein content at 4.10%. VR5 (derived from wheat) showed the highest dry matter content (92.31%), and VR9 (derived from wheat bran) recorded the highest crude fat (12.90%) and crude ash (9.21%) contents. Additionally, VR1 (derived from rice) contained the highest levels of neutral detergent fiber (65.73%), acid detergent fiber (56.03%), and crude fiber (30.60%). Moreover, VR7 had the highest levels of amino acids, including glutamic acid (2.01%) and leucine (1.30%). In contrast, VR10 exhibited the lowest amino acid content among the vinegar residues. Furthermore, VR6 (derived from wheat) had the highest concentrations of iron (1,002 mg/kg), while VR1 contained the lowest levels of copper (8.25 mg/kg), and iron (218 mg/kg). Additionally, VR7 recorded the highest levels of phytate phosphorus (0.45%), and copper (26.81 mg/kg).

Table 1. Chemical composition and amino acids of vinegar residue from different sources (as-fed basis).

Item Rice Wheat Sorghum Wheat bran VR1 VR2 VR3 VR4 VR5 VR6 VR7 VR8 VR9 VR10 Gross Energy (GE, MJ/kg) 18.59 17.92 18.98 17.74 18.64 18.69 17.58 17.36 20.70 15.03 Dry Matter (DM, %) 92.39 90.22 92.04 90.08 92.31 92.72 90.78 90.90 90.03 90.27 Crude Protein (CP, %) 13.6 10.42 11.68 10.35 13.69 14.52 15.63 10.44 11.76 4.10 Crude Fat (EE, %) 5.10 6.25 5.08 7.18 7.96 9.42 11.77 5.79 12.90 3.16 Total Mineral Content (Ash, %) 5.38 2.23 8.59 1.56 1.89 7.35 2.43 4.23 9.21 10.00 Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF, %) 65.73 48.72 59.18 59.13 40.42 58.75 42.23 58.39 57.50 63.19 Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF, %) 56.03 27.83 34.20 27.99 16.86 40.67 20.63 32.40 28.81 43.24 Crude Fiber (CF, %) 30.60 23.76 25.01 26.29 13.40 30.29 11.03 25.53 18.86 30.29 Total Dietary Fiber (TDF, %) 66.40 51.10 60.20 63.10 41.90 60.60 45.90 61.80 59.40 63.80 Soluble Dietary Fiber (SDF, %) 0.80 3.10 3.80 6.30 1.90 0.80 4.70 4.60 5.40 0.50 Insoluble Dietary Fiber (IDF, %) 65.60 48.00 56.40 56.80 40.00 59.80 41.20 57.20 54.00 63.30 Amino Acid, % Asp 0.48 0.69 0.74 0.76 0.75 0.60 0.82 0.67 0.79 0.38 Thr 0.36 0.39 0.40 0.36 0.46 0.34 0.43 0.31 0.41 0.21 Ser 0.36 0.42 0.38 0.37 0.43 0.36 0.64 0.32 0.41 0.21 Glu 1.70 1.68 1.41 1.39 1.51 1.95 2.01 1.20 1.47 0.71 Gly 0.35 0.35 0.51 0.50 0.59 0.46 0.54 0.42 0.53 0.27 Ala 0.72 0.77 0.61 0.60 0.60 0.76 0.79 0.51 0.61 0.32 Cys 0.06 0.09 0.15 0.18 0.10 0.19 0.12 0.18 0.15 0.09 Val 0.50 0.52 0.60 0.58 0.62 0.59 0.98 0.52 0.54 0.29 Met 0.12 0.12 0.13 0.11 0.14 0.09 0.16 0.14 0.10 0.03 Ile 0.37 0.39 0.39 0.38 0.41 0.39 0.47 0.31 0.40 0.20 Leu 1.00 1.08 0.73 0.68 0.72 1.00 1.30 0.58 0.81 0.37 Tyr 0.27 0.27 0.31 0.29 0.28 0.32 0.64 0.27 0.32 0.18 Phe 0.32 0.37 0.34 0.31 0.30 0.40 0.24 0.27 0.36 0.17 Lys 0.13 0.24 0.42 0.40 0.39 0.18 0.26 0.32 0.36 0.16 His 0.16 0.21 0.23 0.23 0.27 0.19 0.31 0.17 0.24 0.15 Arg 0.04 0.26 0.50 0.47 0.47 0.16 0.28 0.40 0.41 0.13 Pro 0.48 0.54 0.36 0.34 0.37 0.69 0.51 0.30 0.49 0.30 Mineral Ca, % 0.20 0.17 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.03 0.01 0.01 P, % 0.05 0.04 0.09 0.08 0.08 0.06 0.04 0.08 0.06 0.02 Phytate Phosphorus, % 0.40 0.32 0.24 0.08 0.08 0.30 0.38 0.45 0.30 0.24 Na, % 0.11 0.03 0.04 0.09 0.09 0.03 0.07 0.08 0.03 0.04 K, % 0.13 0.06 0.11 0.08 0.08 0.06 0.04 0.09 0.06 0.03 Mg, % 0.03 0.03 0.07 0.03 0.03 0.06 0.03 0.05 0.06 0.02 Cu, mg/kg 8.25 12.56 10.56 17.20 17.20 16.52 16.58 26.81 16.52 11.25 Fe, mg/kg 218 663 663 682 682 465 1002 785 465 358 Zn, mg/kg 15.02 12.65 16.68 18.36 18.36 21.35 21.54 23.54 21.35 19.35 Digestibility and concentration of energy

-

The digestible energy (DE) and metabolizable energy (ME) values of vinegar residues from various regions are detailed in Table 2. Pigs fed the diet containing VR8 (derived from sorghum), had the lowest gross energy (GE) intake and fecal GE excretion among all groups (p < 0.05). In contrast, pigs receiving the VR6 diet (derived from wheat), exhibited the highest GE excretion in feces (p < 0.05). Additionally, the diet containing VR4 (derived from rice), resulted in the lowest urinary GE excretion. Pigs fed the VR5 and VR6 diets, both derived from wheat, demonstrated the lowest apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) of GE compared to other groups (p < 0.05), while those fed VR1 (derived from rice) and VR10 (derived from wheat bran) showed the highest ATTD of GE (p < 0.05). Moreover, pigs fed the VR5 diet had the lowest DE and ME values, whereas those consuming VR1 (derived from rice) had the highest ME value (p < 0.05).

Table 2. Effective energy values of vinegar residue from different sources.

Item Corn Rice Wheat Sorghum Wheat bran SEM p-value VR1 VR2 VR3 VR4 VR5 VR6 VR7 VR8 VR9 VR10 As-fed basis GE intake, MJ/d 20.65a 19.17a 18.28a 18.93a 18.60a 16.81a 19.26a 19.61a 11.69b 17.73a 18.18a 0.390 <0.01 GE in feces, MJ/d 5.13de 6.12bcd 6.93abc 6.71abc 6.61abcd 6.77abc 7.74a 7.42ab 4.11e 5.91bcd 5.82cd 0.151 <0.01 GE in urine, MJ/d 0.61a 0.45ab 0.42ab 0.53a 0.22b 0.62a 0.63a 0.56a 0.40ab 0.37b 0.46ab 0.024 <0.01 ATTD of GE 0.75a 0.68b 0.62cd 0.65bcd 0.64bcd 0.60d 0.60d 0.62cd 0.65bcd 0.67bc 0.68b 0.006 <0.01 DE/(MJ/kg) 14.40a 13.01b 11.93ab 12.37bc 12.35bc 11.40d 11.47d 11.96bcd 12.41bc 12.75bc 13.02b 0.117 <0.01 ME/(MJ/kg) 13.79a 12.08b 11.07bcd 11.52bc 11.13bcd 10.06d 10.54cd 11.11bcd 10.40cd 11.63bc 11.60bc 0.140 <0.01 In the same row, values with different small letter superscripts mean significant difference (p < 0.05), while values with the same or no letter superscripts mean no significant difference (p > 0.05). The same applies below. Growth performance of growing pigs fed diets based on different sources of VR

-

Based on the results mentioned above, one vinegar residue from each of the four sources (VR-R [VR1], VR-W [VR6], VR-S [VR7], and VR-WB [VR9]) was selected based on effective energy values for subsequent experiments on growing pigs. As shown in Table 3, no significant differences in final weight were observed among the five groups, and no differences in average daily gain (ADG) and average daily feed intake (ADFI) were observed overall among the treatments (p > 0.05). However, pigs fed the VR-W diet exhibited a higher feed-to-gain ratio (F:G) than those fed the control (CON) or VR-R diets (p < 0.05).

Table 3. Growth performance of growing pigs fed diets based on different sources of VR.

Item Treatment SEM p-value CON VR-R VR-W VR-S VR-WB Initial weight, kg 20.55 20.86 20.61 20.88 20.31 0.22 0.895 Final weight, kg 43.52 43.30 42.39 42.30 42.65 0.51 0.354 ADG, g/d 656 641 622 612 643 13 0.685 ADFI, g/d 1304 1275 1314 1266 1298 25 0.421 F/G 1.99b 1.99b 2.11a 2.06ab 2.02ab 0.03 0.038 Values are means ± SEMs, n = 6. Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different from each other, p < 0.05. Plasma anti-oxidative enzyme activities and cytokines of growing pigs fed diets based on different sources of VR

-

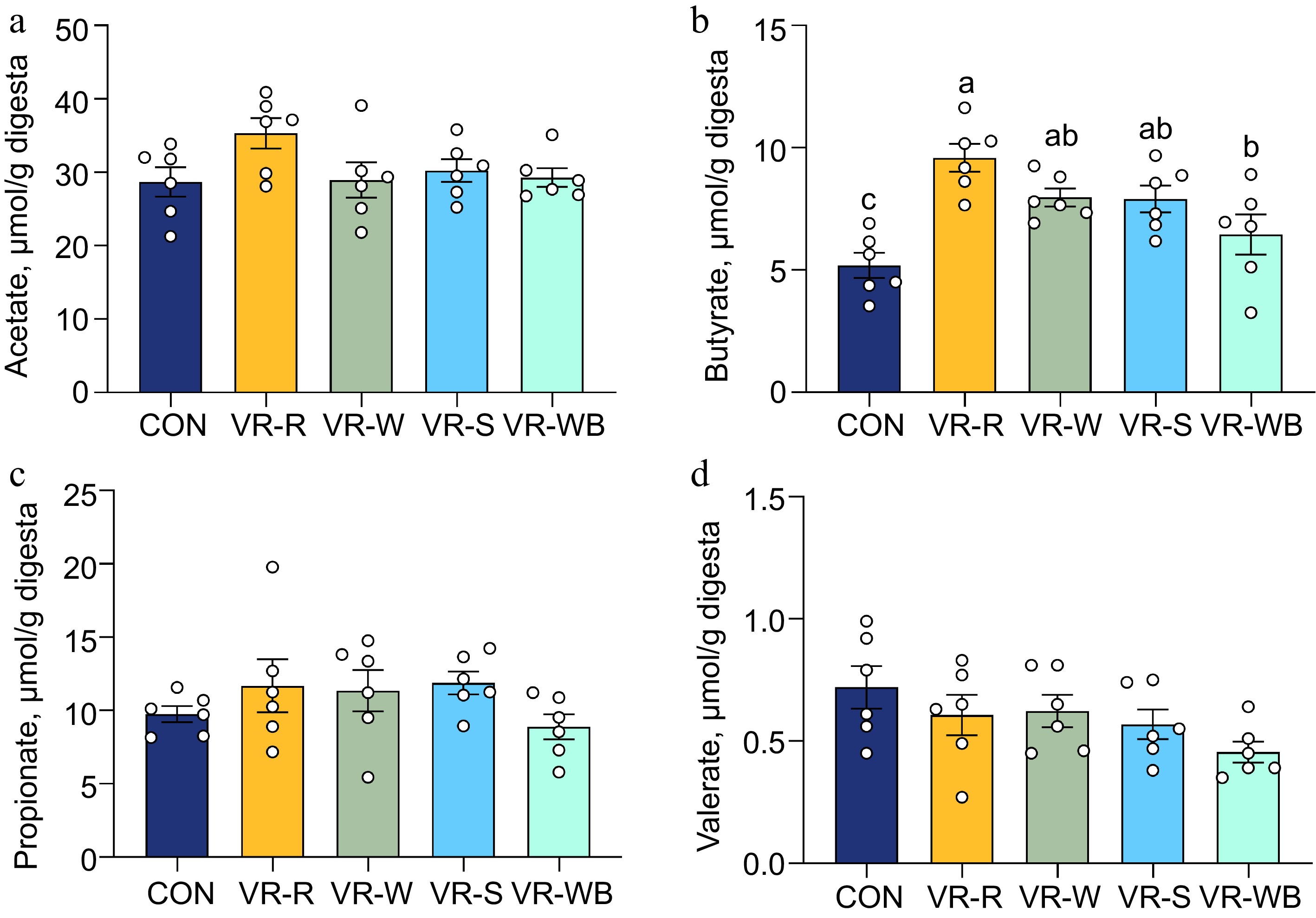

To investigate the effects of vinegar residue (VR) on oxidative stress and the inflammatory response, we analyzed anti-oxidative enzyme activity, oxidative metabolites, and cytokines in plasma. As shown in Fig. 1, pigs fed the VR-W diet had significantly lower levels of MDA and increased activities of CAT and GSH-Px in plasma compared to the CON group (p < 0.05). Additionally, lower MDA levels and higher GSH-Px levels were observed in pigs fed the VR-W diet compared to those fed the CON diet (p < 0.05). Moreover, no differences were observed in the plasma levels of GSH and SOD among all groups (p > 0.05). Furthermore, pigs fed the VR-R or VR-W diets had lower pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in plasma compared to pigs fed the CON diet (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Plasma antioxidative enzyme activities and cytokines of growing pigs fed diets based on different sources of VR. (a)−(d) The plasma activities of MDA, CAT, GSH-px, GSH, and SOD. (f)−(i) The plasma levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-6 values are means ± SEMs, n = 6. Labelled means without a common letter are significantly different from each other, p < 0.05.

Effects of VR on the intestinal oxidative stress and inflammatory response related to Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways

-

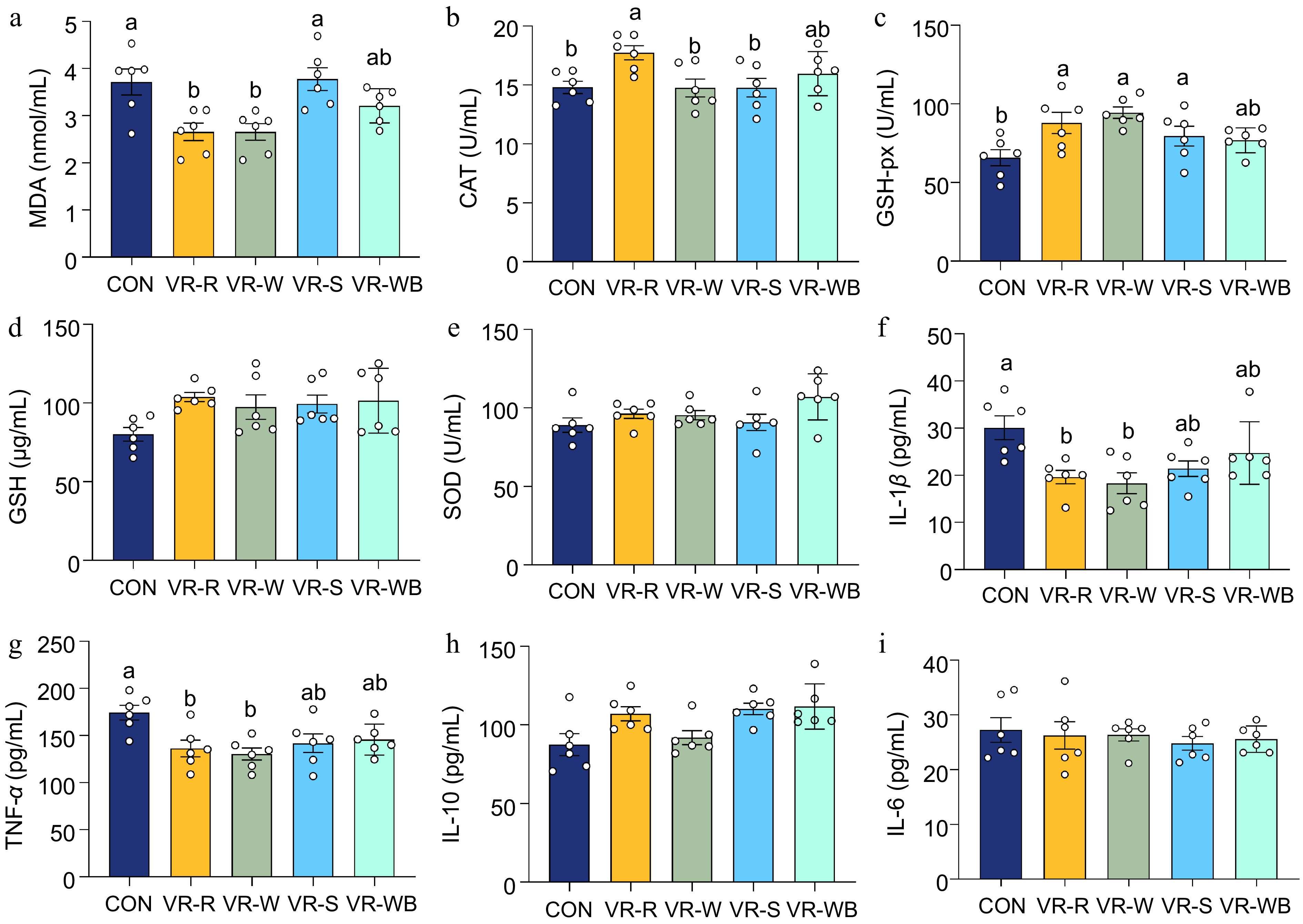

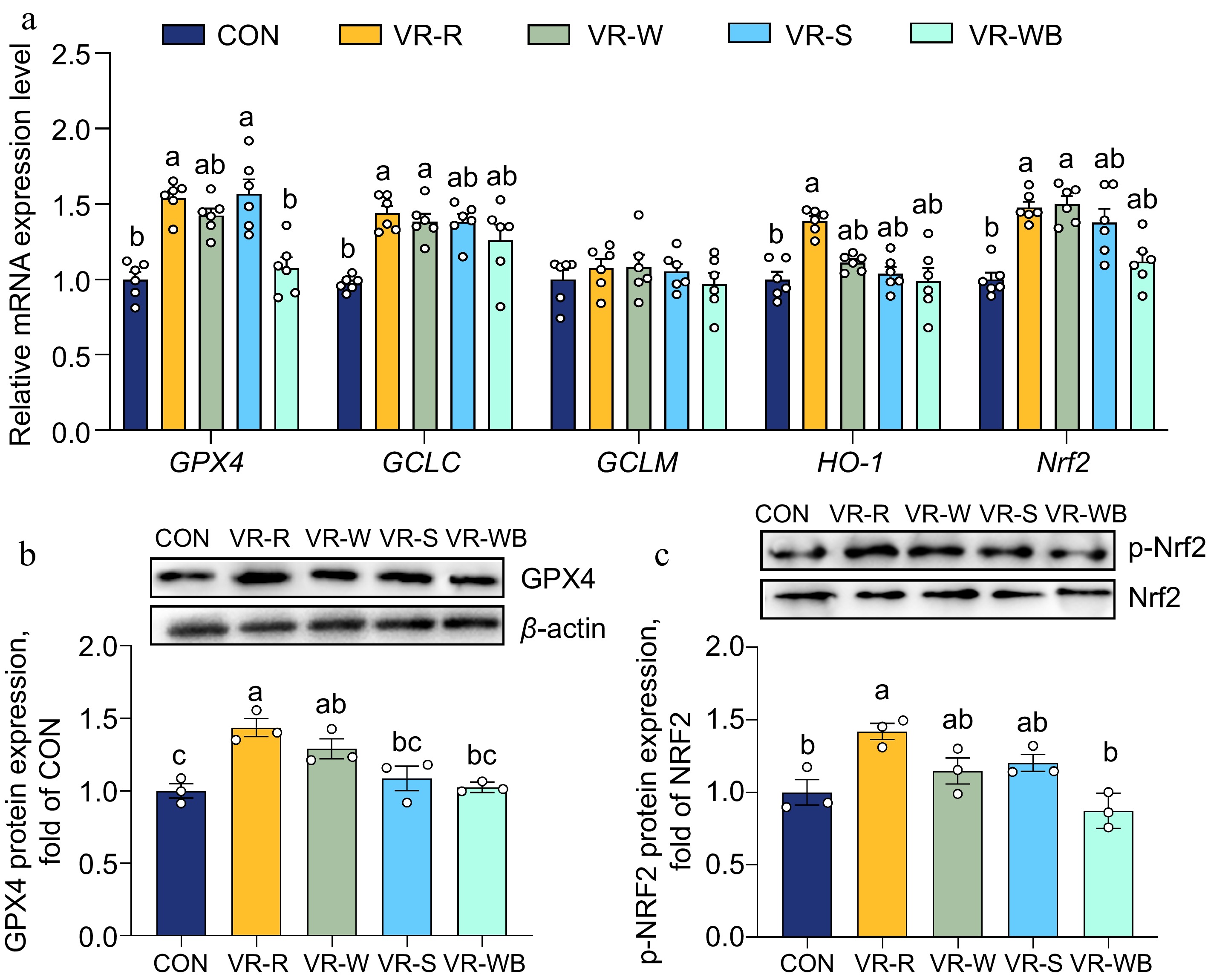

To investigate the effects of vinegar residue (VR) on oxidative stress and the inflammatory response in the small intestine, we analysed the expression of the Nrf2 and NF-κB signalling pathways. As shown in Fig. 2, the intestinal mRNA expression levels of Nrf2, GPX4, HO-1, and GCLC were significantly upregulated in the VR-R group compared to the CON group. Moreover, pigs fed the VR-R diet had greater GPX4 protein expression and higher Nrf2 phosphorylation levels compared to pigs fed the CON diet (p < 0.05). Additionally, VR-R treatment downregulated the relative mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, MyD88, and TLR4 compared to the CON treatment (p < 0.05; Fig. 3). Moreover, pigs fed the VR-R diet had lower phosphorylation levels of NF-κB and IκB compared to pigs fed the CON diet (p < 0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Effects of VR on the intestinal oxidative stress related to Nrf2 pathways. (a) Relative mRNA expressions of GPX4, GCLC, GCLM, HO-1, and Nrf2 normalized to β-actin expression. (b), (c) Western blot analysis of GPX4 and p-Nrf2 protein levels normalized to β-actin or Nrf2. Values are means ± SEMs, n = 3 or 6. Labelled means without a common letter are significantly different from each other, p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Effects of VR on the intestinal inflammatory response related to NF-κB pathways. (a) Relative mRNA expressions of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, TLR4, and Myd88 normalized to β-actin expression. (b), (c) Western blot analysis of p-NFκB and p-IκB protein levels normalized to NFκB or IκB. Values are means ± SEMs, n = 3 or 6. Labelled means without a common letter are significantly different from each other, p < 0.05.

Effects of VR on the intestinal bacterial composition, diversity, and metabolites

-

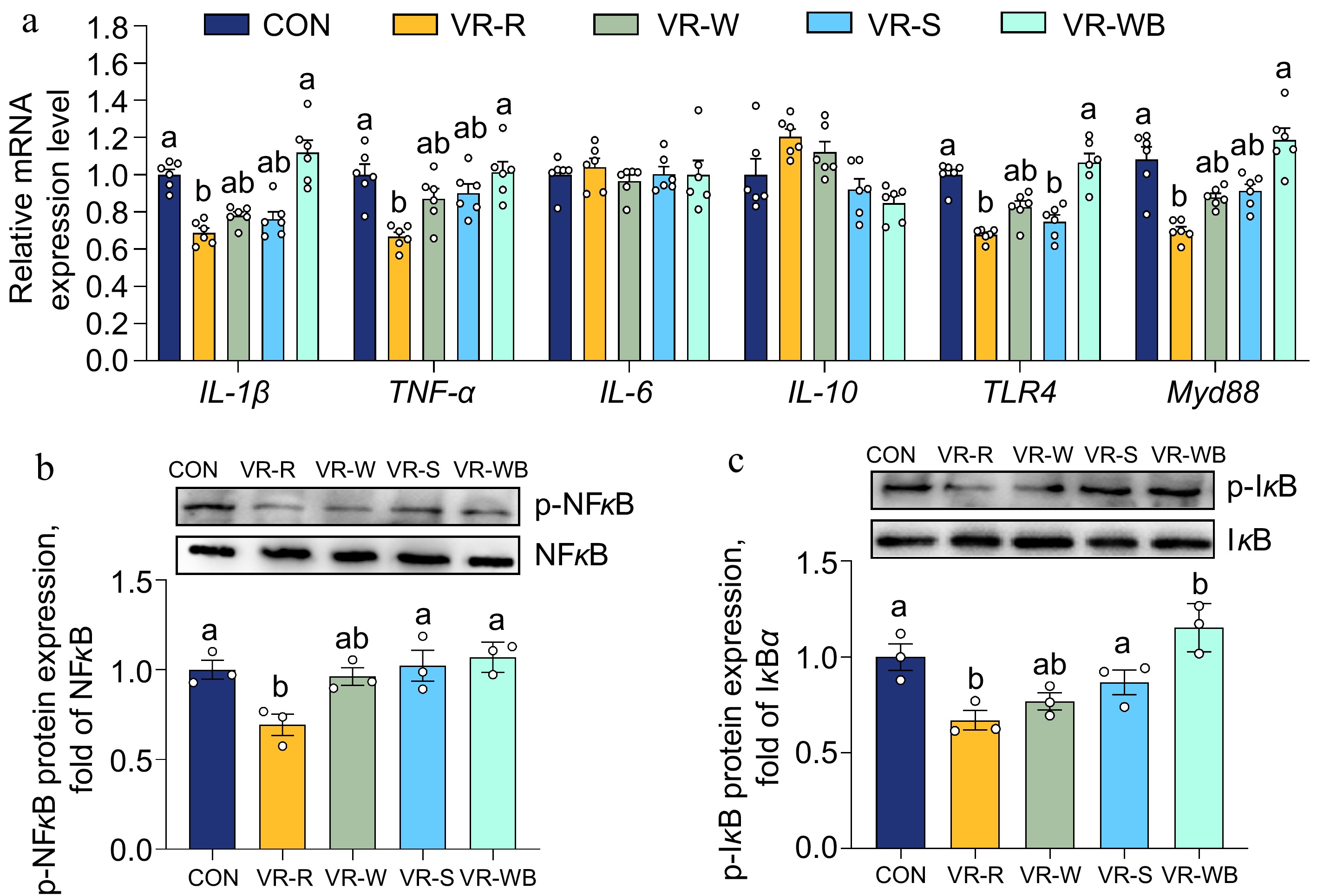

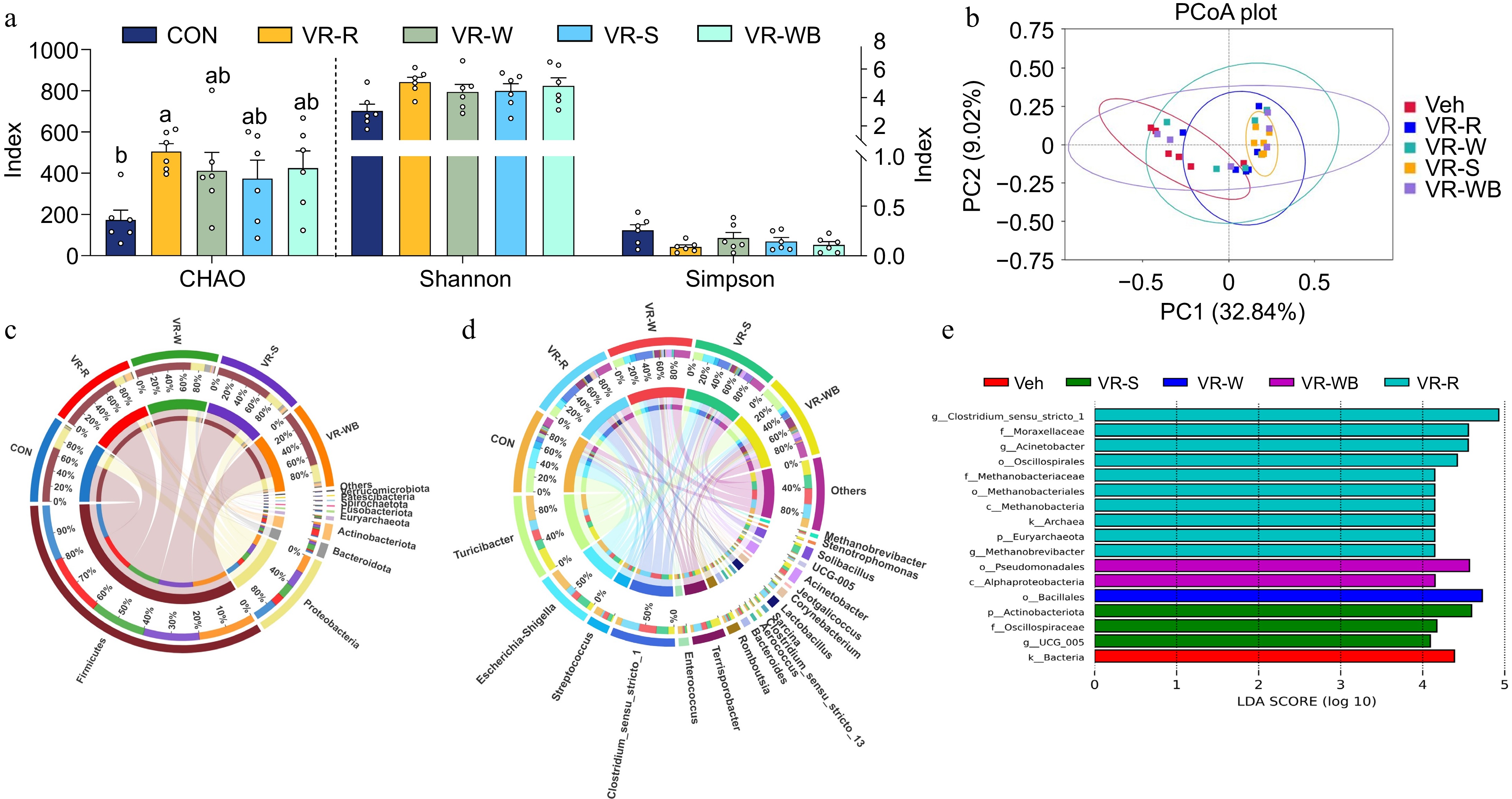

The VR diet contains higher plant fiber than the CON diet, and fiber can provide energy to intestinal epithelial cells, as well as regulate the structure and metabolism of the intestinal microbiota. Therefore, we analyzed the ileal microbiome. As shown in Fig. 4, pigs fed the VR-R diet had higher α-diversity (CHAO index) compared to pigs fed the CON diet. Additionally, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distances revealed that the overall β-diversity of the gut microbiota composition was significantly different between the CON group and the VR group. At the phylum level, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were the most dominant phyla, with average abundances exceeding 70% and 20%, respectively. At the genus level, Turicibacter, Clostridium sensu stricto 1, and Escherichia-Shigella were more abundant in the ileum. LEfSe analysis revealed a total of 17 taxonomic groups with significant differences, ranging from the phylum to the genus level (Fig. 4c, d). Specifically, compared to the CON group, the relative abundance of g_Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, f_Moraxellaceae, g_Acinetobacter, o_Oscillospirales, f_Methanobacteriaceae, c_Methanobacteria, k_Archaea, p_Euryarchaeota, and g_Methanobrevibacter increased in the VR-R group, while the relative abundance of k_Bacteria decreased. Furthermore, butyrate levels were significantly increased in the ileum of pigs fed the VR-R diet compared to those fed the CON diet (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5). No differences in the levels of acetate, propionate, and valerate were found among the five groups (p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of VR on the intestinal bacterial composition and diversity. (a) The diversity of CHAO, Shannon Simpson. (b) PCoA analysis. (c), (d) The community structure of each group was analyzed at the phylum level and genus level. (e) Distribution histogram of different bacteria based on LDA score. Values are means ± SEMs, n = 6. Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different from each other, p < 0.05.

-

The limited availability of traditional feedstuffs (e.g., corn, soybeans, wheat) has hindered livestock industry growth globally. To address rising livestock product demand and reduce food resource competition, agro-industrial byproducts are emerging as vital alternative feeds[19]. These unconventional resources offer cost advantages over traditional options and are increasingly integrated into ruminant production systems[20,21]. In this study, we assessed the nutritional characteristics of vinegar residue (VR) using indicators such as dry matter, crude protein, and crude fiber. The feeding value of VR is closely related to its crude protein content. In this study, the crude protein content from different sources ranged from 4.10% to 15.63%, with VR derived from wheat bran having lower crude protein compared to the other sources. Additionally, the digestible energy (DE) and metabolizable energy (ME) values of VR from different sources ranged from 11.40 to 13.02 MJ/kg, and 10.06 to 12.08 MJ/kg, respectively. The DE and ME values of VR are lower than those of corn. Moreover, the source of the VR also affects the DE and ME values. For instance, VR derived from wheat had lower DE and ME than those derived from rice, wheat bran, and other sources. These differences may be attributed to the varying nutritional components of vinegar residue from different sources and the distinct fermentation processes involved[8].

Residues may be used as the sole cereal grain to replace corn in diets fed to pigs without adversely affecting the growth performance of weaned pigs[22,23]. Similar to previous results, our study observed no significant differences in final weight among the five groups, and no differences in ADG and ADFI across the groups. Considering only ADG and ADFI, VR may be equivalent to corn for growing pigs without any negative effects on growth performance. Oxidative stress is a critical factor influencing the growth of pigs, caused by environmental factors and feed type[24]. Elevated ROS could drive membrane destabilization through polyunsaturated fatty acid oxidation (lipid peroxidation, LPO), compromising the structural and functional integrity of biomolecules. This oxidative cascade generates MDA – a thiobarbituric acid-reactive substance (TBARS) widely quantified as an index of redox imbalance-mediated cytopathological alterations[25]. In the present study, we observed that treatment with VR-R and VR-W decreased plasma MDA levels compared to the CON treatment. Moreover, pigs fed the VR-R diet exhibited higher CAT and GSH-px activities in the plasma. Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-px) is known for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis by detoxifying lipid hydroperoxides, thereby preventing the chain reaction of LPO[26]. The increased GSH-px activity observed with VR-R treatment may contribute to the reduced MDA levels. Importantly, Nrf2 regulates the expression of a wide array of antioxidant genes, including antioxidant enzymes (GPX4, GCLC, GCLM) and phase II antioxidant enzymes (HO-1), to mitigate tissue damage, and maintain redox homeostasis during oxidative stress[26,27]. We subsequently assessed the Nrf2 pathway and found that pigs fed the VR-R diet had higher Nrf2 phosphorylation, which may explain the lower plasma MDA levels. Moreover, GPX4 mRNA expression was upregulated in both the VR-R and VR-S groups compared to the CON group. Additionally, these groups exhibited elevated GPX4 protein expression levels. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) serves as a defense against oxidative lipid damage and a key regulator of the immune response, with these two functions tightly regulated to maintain host homeostasis[28,29]. Perhaps due to the vinegar fermentation process, certain nutrients are converted by micro-organisms into polyphenols and flavonoids, which possess antioxidant and other bioactive properties. As a result, vinegar residue may contain these beneficial compounds, and dietary supplementation with vinegar residue could enhance the antioxidant capacity of piglets[30,31]. Collectively, we conclude that VR treatments, particularly the VR-R treatment, reduce plasma MDA levels by promoting Nrf2 phosphorylation and GPX4 protein expression, thereby contributing to redox balance in pigs.

In addition to oxidative stress, the immune system is also a crucial factor in triggering host inflammation during the growth process of pigs[24]. Immunological homeostasis exhibits marked vulnerability to redox perturbations, wherein ROS compromises phospholipid bilayer integrity and disrupts transcriptional regulatory networks in leukocytes through peroxidative modification of signaling scaffolds[2,32]. This oxidative micro-environment drives the polarization of cytokine profiles, with dynamic equilibrium between pro-inflammatory cascades and immuno-suppressive pathways. Consequently, quantitative serum cytokine profiling has emerged as a functional biomarker panel for immunometabolic status assessment[33]. Consistently, our results demonstrated that VR-R treatment reduced plasma IL-1β and TNF-α levels, which is further supported by findings showing that VR-R treatment downregulated the intestinal mRNA levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in mice. Mechanistically, TLR4 orchestrates pro-inflammatory mediator synthesis through MyD88-dependent initiation of canonical NF-κB signaling[34]. VR-R intervention demonstrated significant downregulation of intestinal TLR4/MyD88 gene expression, and attenuated phosphorylation events in the IκBα/NF-κB axis, indicating modulation of this inflammatory cascade. Intriguingly, Nrf2 modulates crosstalk between redox homeostasis and inflammatory cascades via molecular competition with CREB-binding protein (CBP). This redox-sensitive regulatory node not only impedes stress-activated NF-κB nuclear translocation but also enhances IκB-α stability through ubiquitination blockade, as evidenced by proteasomal degradation assays[35,36]. Overall, the VR-R supplement could enhance adaptive immunity through the suppression of TNF-α and IL-1β levels via blocking IκBα/NF-κB pathway.

The intestinal microbiota serves as a critical barrier against pathogens, and plays a vital role in modulating intestinal function by promoting the development of the gut immune system[37]. One key aspect of VR is its high fiber content, which promotes microbial colonization and growth, leading to the production of SCFAs that confer significant health benefits[11]. In this study, pigs in the VR-R group exhibited increased richness in the ileum as shown by the Chao index. Ecological modeling predicts that gut microbial communities with elevated α-diversity exhibit enhanced metabolic plasticity through niche complementarity mechanisms. This functional buffering capacity – manifested as conserved SCFA production profiles under dietary perturbations – confers ecosystem resilience against xenobiotic challenges[38]. Mature microbiota characterized by high phylogenetic diversity exhibit robust associations with immune-metabolic crosstalk and co-adaptation, representing a defining feature of the intestinal homeostasis[39]. Moreover, our findings revealed that the gut microbiota in VR-R diet-fed pigs experienced changes, particularly with an increased abundance of anti-inflammatory-linked bacteria, such as g_Clostridium sensu stricto (cluster I), as identified through phylogenomic analyses and novel protein signatures[40]. The g_Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 is a gut commensal which plays a critical role in preventing and reducing intestinal stress[41]. Clostridium sensu stricto has also been shown to promote the accumulation of butyrate[42]. Notably, compared with the CON group, the concentration of butyrate was higher in the VR-R group. Butyrate is rapidly absorbed by intestinal epithelial cells as an energy source and has multiple beneficial effects on host health, including anti-inflammatory properties and enhanced antioxidant capacities in the intestine[43]. Therefore, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of VR on piglets' intestines in the present study may be due to the increase in butyric acid content. Our results suggest that VR intervention can enhance the relative abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria and butyrate levels, thereby fostering a homeostatic intestinal environment.

-

Vinegar residue is rich in protein, minerals, and other nutrients. Vinegar residues derived from rice, sorghum, and wheat bran have similar DE and ME content. Moreover, corn can be replaced with 5% vinegar residue in the diets of growing pigs without negatively affecting growth performance. Additionally, vinegar residue, particularly from rice, can serve as an alternative energy source to corn in growing pig diets, enhancing anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacities. Overall, vinegar residue increases the relative abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria and their butyrate concentrations, thereby fostering a homeostatic intestinal environment. Our findings establish theoretical support for utilizing vinegar residue (VR) as a dual-functional (resource-conserving and disease-mitigating) additive in swine production.

This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFD1300205-5).

-

All procedures were reviewed and pre-approved by the the Animal Ethical Committee of Yangzhou University, identification number: No.202202160, approval date: 2022-02-24. The research followed the 'Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement' principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management for the animals, ensuring that the impact on the animals was minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: methodology, writing – original draft: Hu P; investigation: Hu P, Wang Y, Yuan Y, Zhu C; formal analysis, validation: Hu P, Wang Y, Yuan Y; data curation: Hu P, Wang Y, Zhu C, Yuan X, Zhu M; resources: Yuan X, Zhu M; supervision, writing – review & editing: Cai D, Liu H, Ogamune KJ; conceptualization, project administration: Cai D, Liu H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and its supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Demin Cai is the Editorial Board member of Animal Advances who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer-review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

- Supplementary Table S1 Composition and Nutritional Levels of experimental diets (as-fed basis).

- Supplementary Table S2 The composition and nutritional value of experimental diets (air-dry basis).

- Supplementary Table S3 Primer sequences in the current study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Hu P, Wang Y, Yuan L, Zhu C, Yuan X, et al. 2025. Vinegar residue: a sustainable alternative to conventional feedstuffs for improving nutritional value and gut health in growing pigs. Animal Advances 2: e019 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0017

Vinegar residue: a sustainable alternative to conventional feedstuffs for improving nutritional value and gut health in growing pigs

- Received: 04 February 2025

- Revised: 24 March 2025

- Accepted: 08 April 2025

- Published online: 22 July 2025

Abstract: The global scarcity of conventional foodstuffs such as corn, soybeans, and wheat has prompted the exploration of sustainable alternatives. Vinegar residue (VR), a byproduct of the food industry, appears as a potentially economical and nutritious feed resource. This study evaluates the nutritional composition of vinegar residue and its impact on growing pigs. Among the several types of vinegar residue evaluated, vinegar residue 7 (sorghum) had the highest crude protein (15.63%), while vinegar residue 1 (rice) had the highest fiber content, and also provided the highest digestible energy (DE) and metabolizable energy (ME). In feeding trials, growing pigs were fed a basic diet supplemented with 5% vinegar residue from rice, wheat, sorghum, and wheat bran (VR-R, VR-W, VR-S, and VR-WB) over 5 weeks. The results showed that both VR-R and VR-W supplementation reduced oxidative stress by lowering plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and boosting antioxidative enzymes (CAT, GSH-Px). VR-R further modulated inflammation by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines, inhibiting nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and activating the nuclear factor erythroid 2 (Nrf2) pathway with genes including GPX4 and HO-1. It also improved gut health by enhancing microbiota diversity, increasing butyrate, and promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Clostridium sensu stricto 1. These findings highlight vinegar residue's potential as a sustainable feed alternative for improving intestinal health in growing pigs.