-

Amid the current scarcity of freshwater resources, utilizing wastewater resources has emerged as a viable strategy to mitigate water scarcity. Extensive research has been conducted on the treatment of wastewater containing metal ions, but most metals in water exist in complex forms rather than as free ions. Metals from industrial wastewater, municipal wastewater effluent, seawater, and lakes are stably complexed with various agents, such as citrate acid, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, nitrilotriacetic acid, and humic acid, due to their strong affinity toward carboxyl and amino functional groups[1,2]. Meanwhile, metal complexes have been used in industry, agriculture, and healthcare, and typical industries include electroplating and dyeing[3]. Citric acid stands out as one of the most prevalent agents due to its ability to serve as a brightening, leveling, and buffering agent in pure copper plating[4]. Meanwhile, citric acid is used in daily life for its anti-corrosion and antibacterial properties, and when discharged into water, it can prevent the precipitation of metals as hydroxides or other less soluble salts[5]. Polluting metal complexes exhibit stability across a wide pH range as well as easy migration and limited biodegradability, and pose serious environmental and health risks due to their persistence and bioaccumulation. However, metal complexes have often been overlooked in water treatment. Thus, it is important to explore the effective removal of metal complexes to achieve water pollution control.

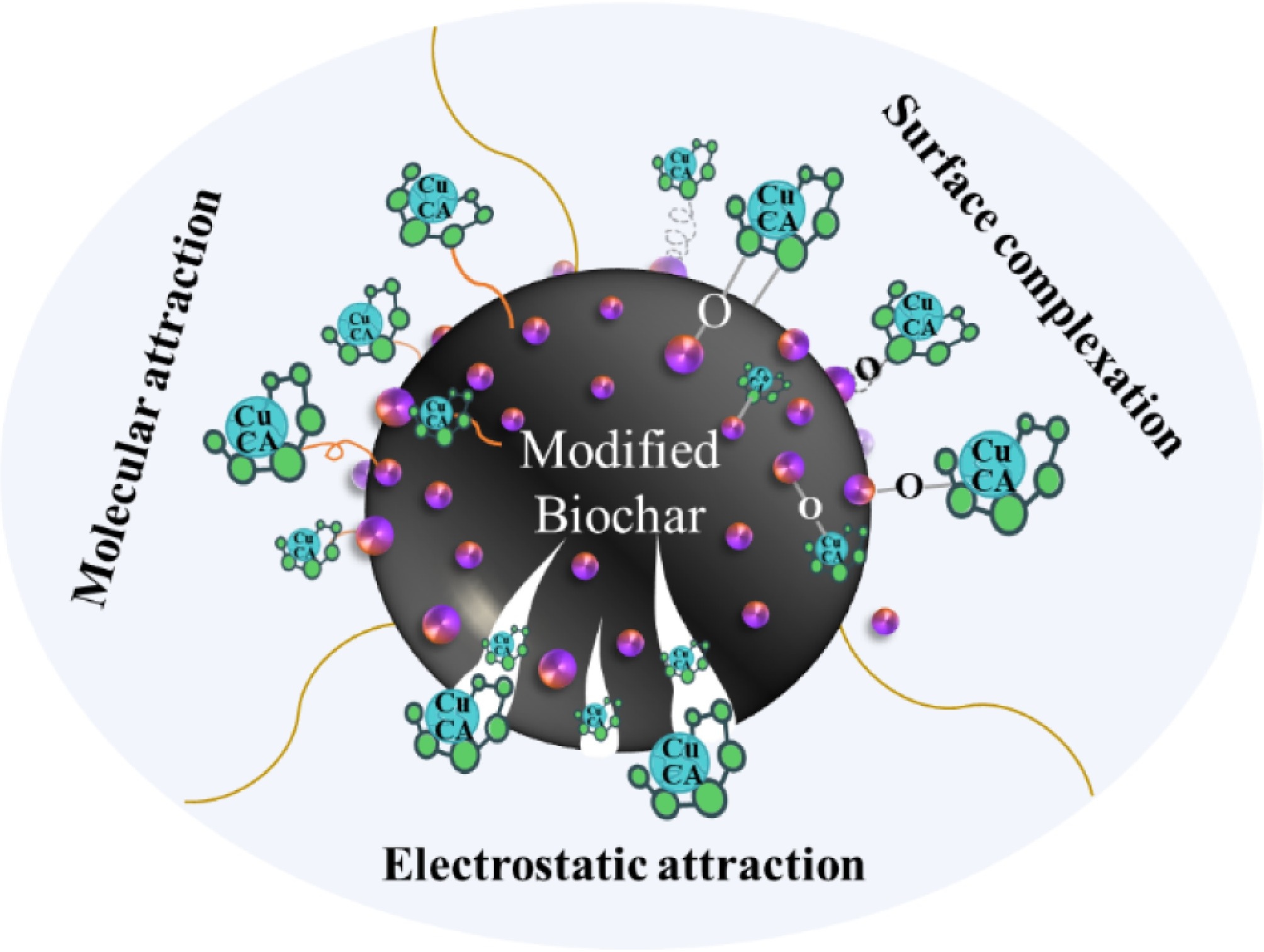

Metal complexes pose persistent issues in the field of environmental protection due to their diverse forms and inherent difficulty of management. The formation of copper–citrate complexes is depicted by the general equilibrium in Eq (1)[6]. Consequently, conventional chemical precipitation or ion exchange methods face significant hurdles in effectively treating electroplating wastewater[7,8]. The removal of metal complexes typically involves two main approaches: decomplexation and integral treatment. In the decomplexation process, heavy metal ions can be released through methods such as the Fenton reaction[9], photo/electrocatalysis[10,11], or plasma discharge[12]. These techniques facilitate the subsequent removal of the metal ions. Another effective method involves removing the metal complexes through adsorption and membrane separation[13], which relies on the active sites of adsorbents or the pore size of the membrane. Copper citrate (CuCA), as a representative organic complex copper, has been removed by ultrafiltration[14], with a orange peel-based biosorbent[15], through biosorption on sludge[16], through UV irradiation[17], and with a nFe3O4/persulfate coupled microbial system[18]. However, the availability of diverse adsorbents broadens the scope and potential applications of adsorption in this context. Biochar stands out as an adsorbent material, offering advantages such as affordability and excellent adsorption effects for heavy metals. However, biochar has shortcomings, such as having few active sites, low adsorption capacity, and poor adsorption selectivity[19]. Using metal elements to modify biochar can effectively enhance its absorption performance. For example, the modification of iron oxides or manganese oxides has emerged as a widespread and effective strategy for enhancing its properties[20]. Fe or Mn oxide-modified biochar could remove metals through forming complexes with oxygen-containing functional groups (–COOH and –OH) and co-precipitation, followed by ion exchange, redox, electrostatic attraction, and cation–π interaction[21,22]. Despite the economical and environmentally friendly nature of modified biochar and its promising adsorption capabilities for metal ions, there remains a gap in the field concerning the removal of copper-containing complexes from wastewater. Additionally, the reaction mechanisms, especially those involving the removal of heavy metal complexes, remain unclear.

$ \mathrm{nCu}^{ {2+}}+ \mathrm{mCit}^{{3-}} +\mathrm{rH}^{ +}\rightarrow \mathrm{Cu}_{ \mathrm{n}} \mathrm{Cit}_{ \mathrm{m}} \mathrm{H}^{ (2{\mathrm{n}}-3{\mathrm{m}}+{\mathrm{r}})+} $ (1) This study utilized ferromanganese binary oxide biochar as an adsorbent to treat the target pollutant CuCA, aiming to investigate the removal mechanism of the CuCA complex through adsorption. Initially, a combination of removal experiments and material characterization methods was employed to analyze the effects of various preparation conditions on the adsorption performance of the modified biochar. Subsequently, the influences of the solution pH, coexisting ions, and removal temperature were assessed. Finally, the adsorption mechanism was explored by examining the chemical structures of the modified biochar and monitoring any changes in its composition. The aim of this research was to provide theoretical support and technical guidance for the practical utilization of ferromanganese binary oxide biochar in the treatment of copper-containing complexes in wastewater.

-

Raw coconut shell biochar (BC) was processed to a particle size of 60–80 mesh. Copper citrate was purchased from MacKlin Reagent Co. Ltd., China. Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) and ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) served as the manganese and iron sources, respectively, for biochar modification. Sodium chloride (NaCl) and calcium chloride (CaCl2) were utilized as the cation sources, while sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), and sodium acetate (CH3COONa) served as the anion sources. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were employed for pH adjustment. All the aforementioned reagents were of analytical purity and were obtained from Beijing Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., China. Nitric acid (HNO3, GR) was sourced from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd, China. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ) was prepared using the Shanghai Hitech water purification system.

Synthesis of ferromanganese oxide-modified biochar

-

The synthesis of ferromanganese oxide-modified biochar followed a modified version of the method reported in a previous study[23]. The adsorption capacity of the modified biochar was influenced by the type and ratio of metals; therefore, the preparation conditions considered the type of Mn salt and Fe salt, their ratio, and the pyrolysis parameters. Briefly, 1 g of 60–80 mesh biochar particles (BC) were mixed with solutions of 0.1 M KMnO4 and FeCl3 in a specific ratio. In this setup, the Mn–Fe ratio was varied to 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4, maintaining a solid–liquid ratio of 1:60. The mixture was adjusted to pH 10 using a 1 mol L–1 NaOH solution and stirred for 10 h at room temperature. Subsequently, it was washed with ultrapure water and dried at 80 °C for 16 h. The solid mixture underwent pyrolysis at various temperatures (400, 500, and 600 °C) for 90 min in a tube furnace, with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1 under a N2 atmosphere. The resulting samples were denoted as FMBC-T (T represents the pyrolysis temperature). The pyrolysis conditions for BC were identical to the aforementioned process and were designated as BC-T.

Characterization

-

The morphology and elemental composition of the samples were characterized using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) at a voltage of 5 kV (ZEISS Sigma 500, Carl Zeiss co., Ltd., UK). The specific surface areas were determined by N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K using a physisorption instrument (ASAP 2020, Micromeritics, US). The crystal lattice structure was analyzed using powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) (XRD-6000, Shimadzu, Japan) with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.540589 Å, 40 kV, and 30.0 mA) over the 2θ range from 5° to 90°. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR (Frontier, PerkinElmer, US) was employed to examine the surface functional groups. The chemical composition and metal valence state were determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Escalab 250xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific, US). Total organic carbon (TOC) was quantified using a TOC analyzer (Multi C/N 2100, Analytik Jena, Germany). Following dilution of the sample with 2% HNO3, the total concentrations of Cu, Mn, and Fe were analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) (PerkinElmer, US).

Batch adsorption experiments

-

A 10 mg/L CuCA stock solution was prepared using ultrapure water, with the initial pH set to 7.0 unless otherwise specified. The mixed suspension was pre-equilibrated by shaking in a constant-temperature shaker (25 °C) at 200 rpm. First, the removal efficiency of CuCA was compared using the modified biochar synthesized at different pyrolysis temperatures (FMBC-T, T = 400, 500, 600 °C) under the conditions of 10 mg·L−1 of the CuCA solution and 1 g L−1 of modified biochar. Second, the effect of varying the dosage of FMBC-600 was analyzed, using concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 g L–1. Meanwhile, 1 g L−1 of BC and BC-T was continuously reacted 22 h as the control experiment. The kinetic experiments were conducted in a mixed solution of 10 mg L−1 of CuCA and 1 g L−1 of FMBC-600 at various time intervals, including 30, 60, 120, 180, 300, 420, 540, and 1,320 min. Thirdly, for the isothermal equilibrium experiments, the initial CuCA concentration was varied across 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg L−1 with 1 g L−1 of modified biochar at 25 and 35 °C for 22 h. Fourthly, the initial pH was adjusted to 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 using 0.1 mol L−1 of HNO3 and NaOH. The influence of coexisting ions was analyzed in a mixed system of of 10 mg L−1 of CuCA and 1 g L−1 of FMBC-600, and the ion concentration was set to 10 and 50 mM, including Na+, Ca2+, CO32−, SO42−, and CH3COO−. Finally, the adsorption-saturated FMBC-600 was added to 1 mol L−1 of a NaOH desorption solution for 24 hours, immediately followed by cleaning and drying, and then the re-adsorption experiment was conducted. The modified biochar, after the second desorption, was subjected to the adsorption test again. All samples were conducted for 22 h and samples were taken at 0.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 22 h. Part of the sample was filtered using a 0.45 μm polyether sulfone (PES) membrane and acidified with 2% dilute nitric acid for detecting Cu, Mn, and Fe concentrations by AAS. Another portion of the sample was analyzed using a TOC analyzer. The concentrations of Cu and TOC were used to evaluate the removal efficiency, while the concentrations of Mn and Fe were used to assess the stability of the modified biochar. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

The removal efficiency (%) of Cu and TOC was calculated using Eqs (2) and (3), respectively, and the adsorption capacity at equilibrium was obtained by Eq (4).

$ \text{Cu}(\text{%})=\dfrac{{{C}}_{{0}}-{{C}}_{{e}}}{{{C}}_{{0}}}\times{100} $ (2) $ \text{TOC}(\text{%})=\dfrac{{{C}}_{{1}}-{{C}}_{{e}{,1}}}{{{C}}_{{1}}}\times {100} $ (3) $ {{q}}_{{e}}=\left({{C}}_{{0}}-{{C}}_{{e}}\right)\times \dfrac{{V}}{{w}} $ (4) where, C0 and Ce (mg L−1) indicate the initial and equilibrium concentrations of Cu, respectively. Similarly, C1 and Ce,1 (mg L−1) represent the initial and equilibrium concentrations of TOC, respectively; qe (mg g−1) denotes the amount adsorbed at equilibrium; and V (L) and w (g L−1) are the volume of the removal system and the mass of modified biochar.

The kinetics were analyzed by fitting a pseudo-first-order kinetic model (Eq [5]) and a pseudo-second-order kinetic model (Eq [6]) to the experimental data. Additionally, the internal diffusion model (Eq [7]) was used to analyze the removal mechanism. The linear forms of the kinetic models are as follows:

$ \ln({{q}}_{{e}}-{{q}}_{{t}})=\ln{{q}}_{{e}}-{{k}}_{{1}}{t} $ (5) $ {{{t}}/}{{q}}_{{t}}=\dfrac{{1}}{{{k}}_{{2}}\times{{qe}}^{{2}}}{+{{t}}/}{{q}}_{{e}} $ (6) $ {q}_{t}=k{{p\times t}}^{{1/2}}{+C} $ (7) where, k1 (h−1) and k2 (g [mg min]−1) represent the adsorption rate constant and the apparent rate constant, respectively; qt (mg min−1) is the amount of Cu adsorbed at time t; kp (mg g−1 min−0.5) is the constant for particle diffusion, and C is a constant.

The adsorption thermodynamic models include the Langmuir adsorption model and the Freundlich isothermal adsorption model. The Langmuir adsorption model assumes that homogeneous surfaces have identical adsorption sites and that adsorbents form a monolayer form. In contrast, the Freundlich isothermal adsorption model assumes that the surface has nonuniform adsorption points. The linear equations for these models are shown in Eqs (8) and (9).

$ \dfrac{{{C}}_{{e}}}{{{q}}_{{e}}}=\dfrac{{1}}{{{q}}_{{m}}\times {{K}}_{{L}}}+\dfrac{{{C}}_{{e}}}{{{q}}_{{m}}}{} $ (8) $ {\log}{{q}}_{{e}}={\log}{K}_{F}+\dfrac{{1}}{{n}}{\log}{{C}}_{{e}} $ (9) where, qm (mg g−1) is the maximum adsorbed amount, KL (L mg−1) is the Langmuir constant, KF is the Freundlich adsorption coefficient, and 1/n represents the surface heterogeneity or adsorption intensity. A value of 1/n < 1 indicates a normal Freundlich isotherm, while a value of 1/n > 1 indicates cooperative adsorption.

-

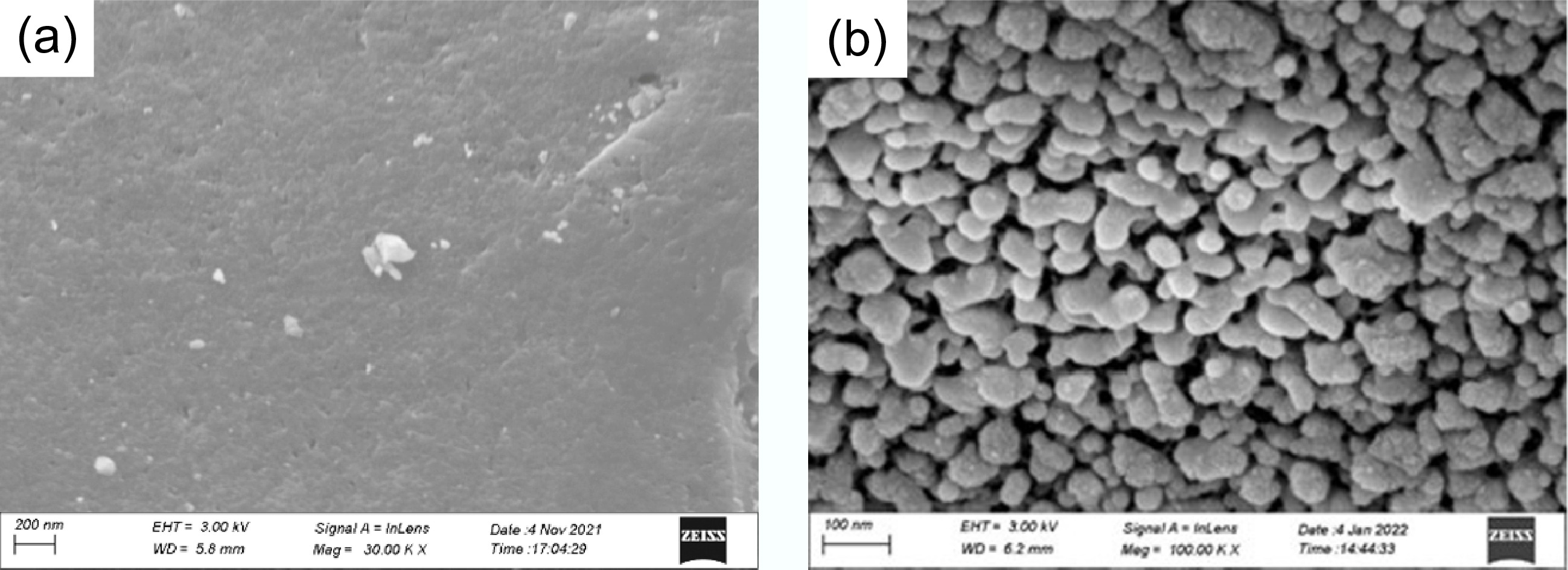

The morphology of BC, BC-600, and FMBC-600 was analyzed (Fig. 1). The FE-SEM results showed significant changes in surface morphology after different treatment processes. The surface morphology of BC was relatively smooth and clear (Fig. 1a). In contrast, FMBC-600 exhibited a rough surface covered with dense and uniform nanoparticles ranging in size from 80 to 100 nm (Fig. 1b). High-magnification surface scanning analysis was conducted on BC and FMBC-600, and the elemental composition results are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The biochar primarily consisted of C and O. However, the presence of Fe and Mn on FMBC-600 confirmed the successful preparation of ferromanganese oxide particles. Additionally, Cu was detected on the surface of the modified biochar after the adsorption process.

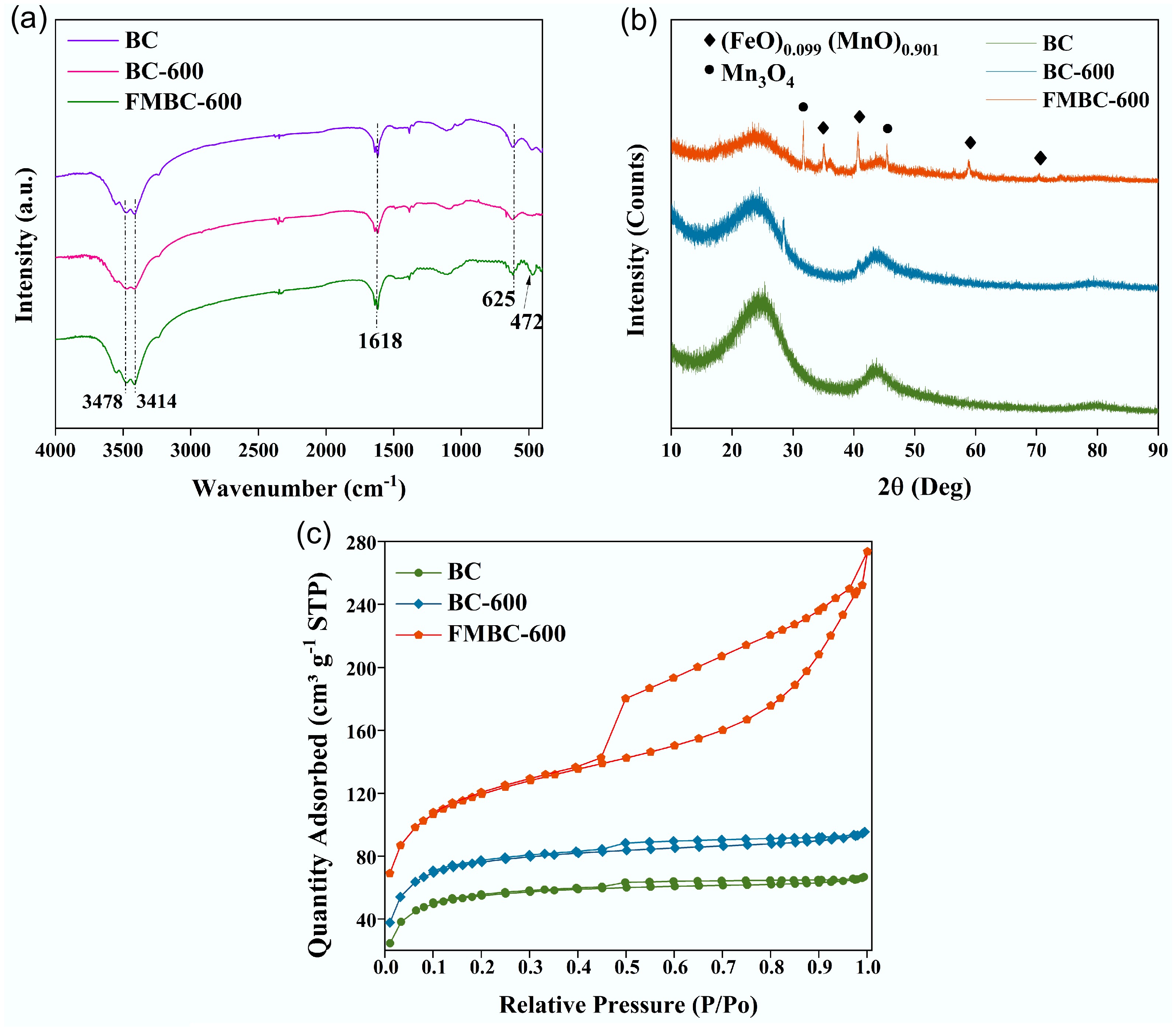

FTIR spectroscopy was used to analyze the possible functional groups in BC, BC-600, and FMBC-600, and the results are shown in Fig. 2a. The peaks at 3,478 and 3,414 cm−1 in all three materials represented the stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups (–OH) related to hydrogen bonding[24]. The characteristic peak of aromatic C=C appeared at 1,618 cm−1, while the stretching vibration peak of aliphatic C–O was around 1,173 cm–1[25]. The peak at 625 corresponded to the aromatic C–H stretching vibration[26]. The absorption peak at 472 cm−1 may be attributed to the stretching vibrations in Mn–O or Fe–O[27,28]. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 2b, BC-600 displayed a new peak compared with BC, which could be attributed to the amorphous structure of SiO2 derived from the raw biomass. According to the XRD results, in comparison with BC and BC-600, the metallic oxides Mn3O4 and (FeO)0.099(MnO)0.901 coexisted on the surface of BC and were well crystallized[29]. The diffraction peaks located at 30.91° and 45.04° can be ascribed to Mn3O4 (PDF#75-0765). The characteristic peaks at 35.04°, 40.68°, 58.89°, and 70.34° suggest the presence of (FeO)0.099(MnO)0.901 (PDF#77-2362). These results confirm that the ferromanganese oxides were successfully supported on the surface of BC, and the modified BC retained its structural integrity. Furthermore, the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm is shown in Fig. 2c, and the data for specific surface area, total pore volume, and pore size are listed in Table 1. The results indicate that changes in specific surface area are closely related to the pyrolysis and modification conditions. The porosity of BC-600 significantly improved, with an increased specific surface area compared with BC. However, the specific surface area of FMBC-600 decreased while the pore volume increased, which may be caused by a collapse in the pore structure of BC or the accumulation of nanoparticles[30]. Despite this, FMBC-600 still had a larger specific surface area than that reported in other studies (specific surface area: 364.47 m2 g−1), which is beneficial for the adsorption of copper complexes[31,32].

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR spectra, (b) XRD patterns, and (c) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of BC, BC-600, and FMBC-600.

Table 1. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) results of BC, BC-600, and FMBC-600

Sample BET surface area (m2 g−1) Pore volume (cm3 g−1) Pore diameter

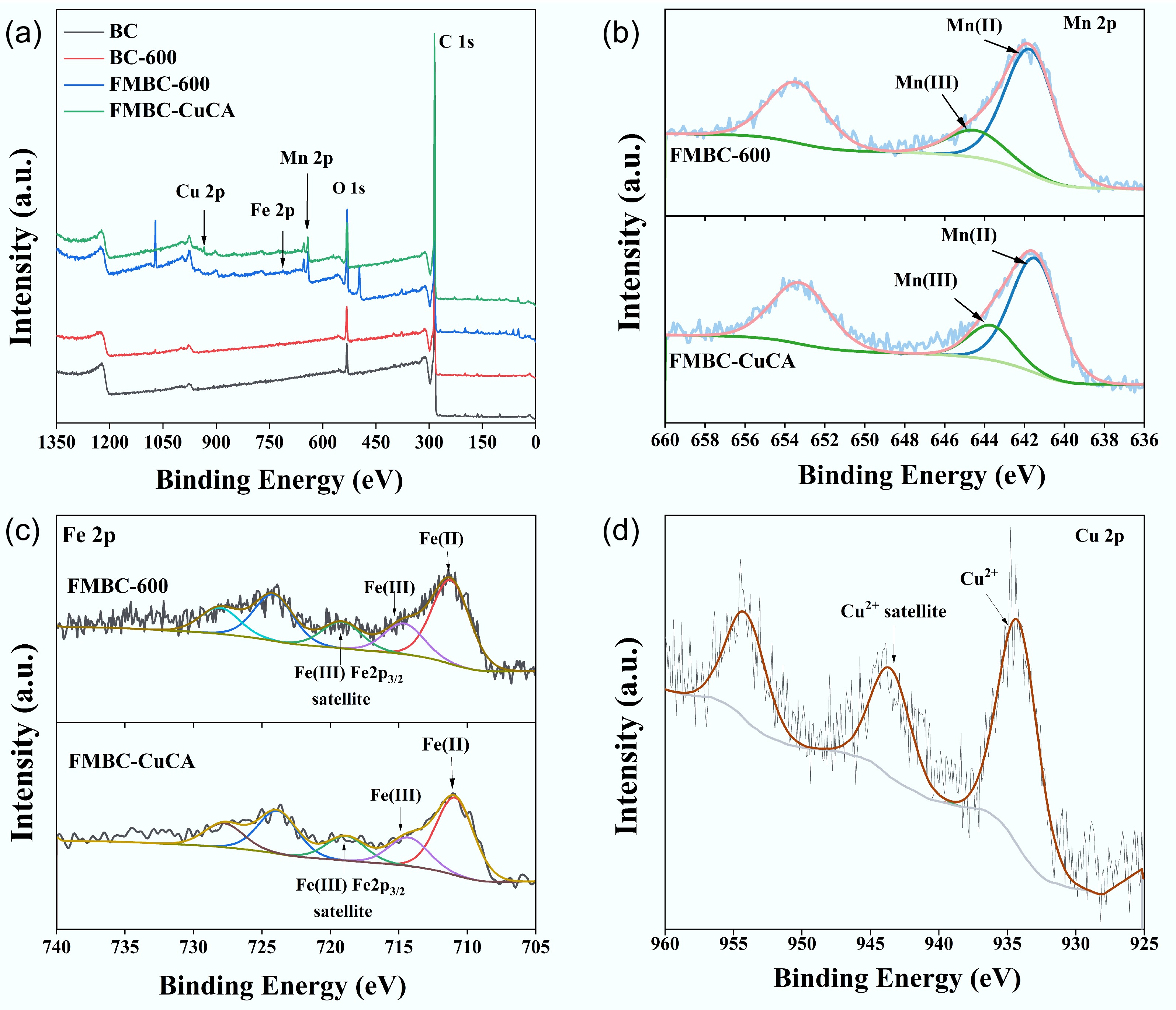

(nm)BC 577.37 0.33 2.30 BC-600 634.65 0.37 2.35 FMBC-600 599.40 0.50 3.32 The valence states and functional groups of the material were analyzed using XPS spectroscopy (Fig. 3). From the full spectrum (Fig. 3a) and the elemental content (Supplementary Table S1), it is evident that BC and BC-600 contained C and O elements; FMBC-600 contained C, O, Mn, and Fe elements; and FMBC-CuCA contained C, O, Mn, Fe, and Cu elements. This confirms that the ferromanganese oxide-modified biochar had adsorption capability. The characteristic peak of C1s was formed by the overlap of three functional group peaks (Supplementary Fig. S1a), with binding energies at 284.08, 285.10, and 290.13 eV, corresponding to C–C, C–O, and O–C=O, respectively[33,34]. For O1s (Supplementary Fig. S1b), the characteristic peaks were attributed to the C–O bond in BC and BC-600, and the Mn/Fe–O bond (530.28 eV) in FMBC-600[35]. Meanwhile, the peak of Fe–O or Mn–O of MBC-CuCA shifted towards lower binding energies (530.06), and the peak intensity increased, which proved that ferric oxide or manganese oxide was involved in adsorption. Further, the binding energies of Mn 2p3/2 at 641.7 and 644.5 eV in FMBC-600 were associated with divalent manganese and trivalent manganese, respectively (Fig. 3b)[35,36]. After adsorption, the centroid of Mn 2p3/2 shifted towards lower binding energies (641.53 and 644.33 eV) and the reduction in the content of divalent and trivalent manganese, which showed that manganese may participate in the removal of CuCA through chemical adsorption[37]. The high-resolution spectra of Fe2p (Fig. 3c) revealed that the binding energy of Fe 2p3/2 at 711.1 and 714.6 eV could be attributed to Fe(II) and Fe(III) transitions[26,38]. After adsorption, the peak intensity of Fe(III) reduced and the intensity of Fe(II) increased, which illustrated that Fe was involved in the removal of CuCA by electron transfer[39]. Additionally, the high-resolution spectra of Cu2p showed that Cu2+ was attached to the surface of FMBC-600, confirming that the modified biochar can adsorb copper complexes.

Figure 3.

(a) XPS spectra, including the full spectrum and the high-resolution spectra of (b) Mn 2p, (c) Fe 2p, and (d) Cu 2p.

Analysis of CuCA removal efficiency

Optimization of modification conditions

-

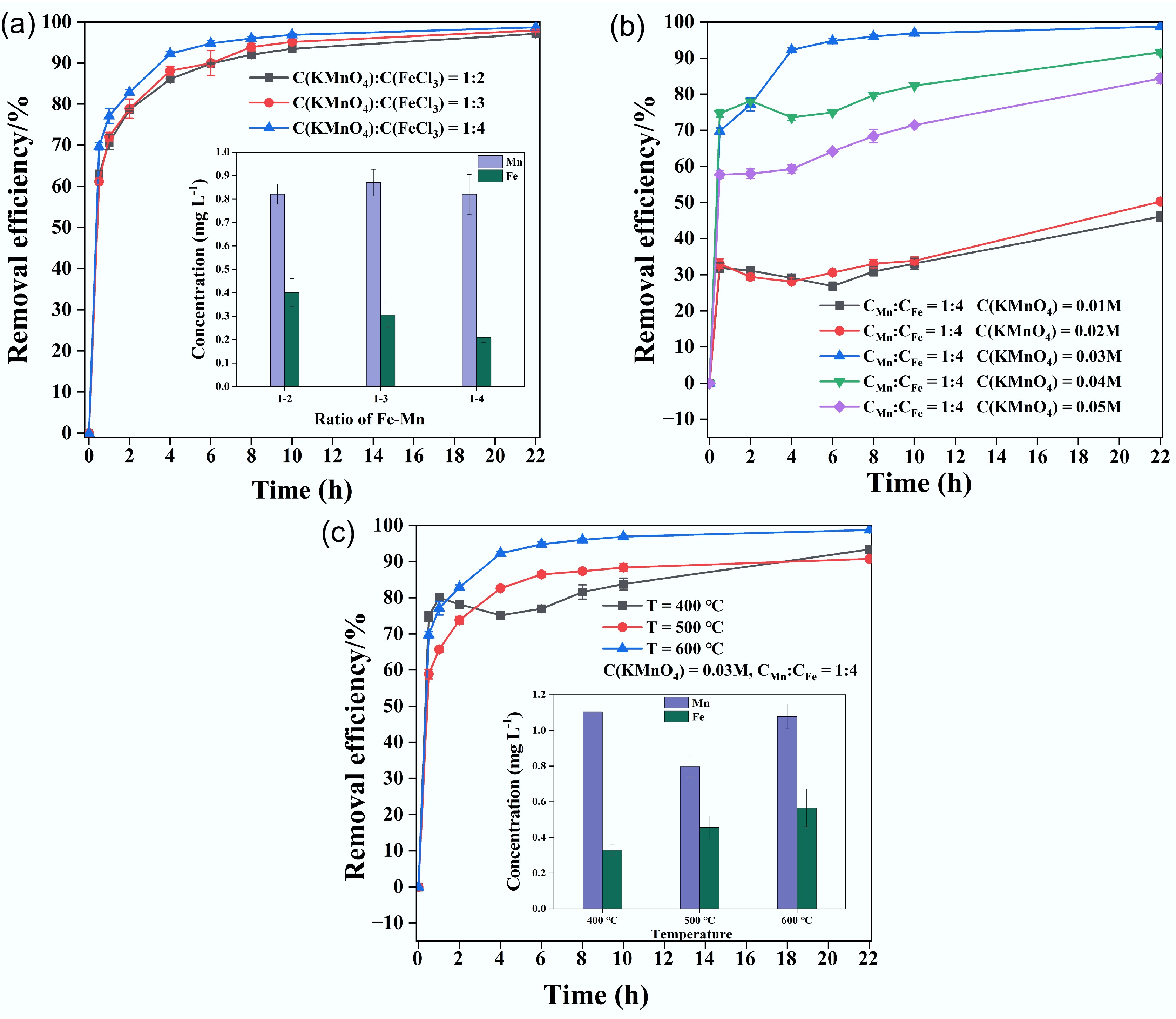

To optimize the preparation conditions for the modified biochar with excellent adsorption performance, various factors were analyzed, as shown in Fig. 4. These factors included the ratios of Fe and Mn, the Mn concentration, and the pyrolysis temperature. Firstly, the removal efficiency of CuCA was observed to be 97.1%, 98.0%, and 99.5%, corresponding to the Fe–Mn concentration ratios of 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4, respectively. The removal efficiency increased slightly with the increase in the iron–manganese ratio, and when the ratio was 1:4, the removal rate already meet the requirements. Next, to investigate the effect of the initial KMnO4 concentration, it was varied from 0.01 M to 0.05 M with steps of 0.01 M. As shown in Fig. 4b, the Cu removal efficiency gradually increased with an increase in the manganese concentration. At a manganese dosage of 0.02 M, the Cu removal efficiency was less than 50%, whereas it exceeded 90% at a dosage of 0.03 M manganese. However, when the concentration was further increased to 0.05 M, both the removal rate and the stability of the modified biochar decreased. Meanwhile, the removal efficiency increased first and then decreased at the initial stage of adsorption, which was caused by more adsorption sites leading to a faster adsorption rate[40]. The results indicate that the amount of manganese added will affect the removal efficiency, and higher manganese addition will change the stability of the modified biochar[41]. Furthermore, the modified biochar was prepared using a ratio of C(KMnO4) to C(FeCl3) of 1:4, with an initial manganese concentration of 0.03 M, and pyrolysis temperatures of 400, 500, and 600 °C. As depicted in Fig. 4c, the removal efficiency of copper remained similar at different temperatures, with FMBC-600 achieving a removal efficiency of 99.5%. Additionally, the optimal modified condition was determined to be a ratio of C(KMnO4) to C(FeCl3) of 1:4, with an initial Mn concentration of 0.03 M under pyrolysis at 600 °C without oxygen.

Figure 4.

Contrastive analysis of Cu removal efficiency based on the (a) Fe–Mn ratio, (b) initial KMnO4 concentration, and (c) pyrolysis temperature.

Optimization of removal conditions

-

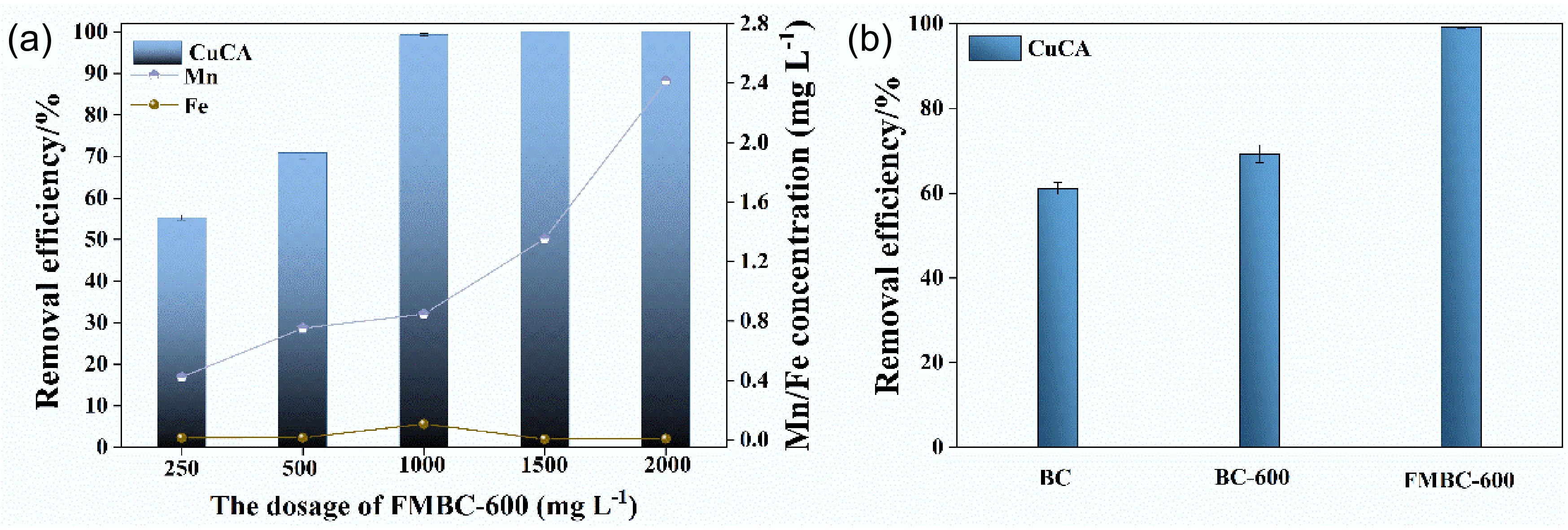

The removal performance of CuCA under different amounts of FMBC-600 is depicted in Fig. 5a. During the removal process, Cu was rapidly adsorbed within the first 30 min due to the abundance of adsorption sites on the surface of FMBC-600. Subsequently, the rate of adsorption gradually slowed down over time. Additionally, the concentration of Mn dissolution increased with both the dosage of modified biochar and time (Supplementary Fig. S2). In Fig. 5a, it is evident that the Cu removal rate increased with the increase in the amount of adsorbent. Moreover, the removal rate reached 99.5% at 1 g L−1 of FMBC-600, with Mn and Fe dissolution concentrations of 0.84 and 0.11 mg L−1, respectively. Meanwhile, the calculated TOC removal rate was 92.6% (Supplementary Table S2). When the dosage increased to 2.0 g L−1, there was no significant improvement in the Cu removal, but with an increased Mn concentration. If we compare these findings with a study on the removal of 1.0 mmol L−1 of copper citrate using 0.25 g L−1 of a magnetic anion exchange resin and 1.0 g L−1 of a cation exchange resin after 24 h, which achieved a removal rate of about 99%[42], FMBC-600 demonstrated excellent copper citrate removal at a dosage of 1.0 g L−1. Additionally, if we compare the removal performance of BC-600 and BC under the established conditions (Fig. 5b), BC and BC-600 removed 62.1% and 67.8% of copper, respectively, which was lower than that of FMBC-600 (99.5%). The control results revealed that the loading of ferromanganese oxides effectively improved the removal ability[43]. By comparing the morphology of FMBC-600 before and after adsorption (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S3), it was found that there were flocculent substances on the surface of FMBC-CuCA, and the nanoparticles agglomerated on the surface, indicating that the stability of the material may be reduced due to agglomeration.

Analysis of influential factors

-

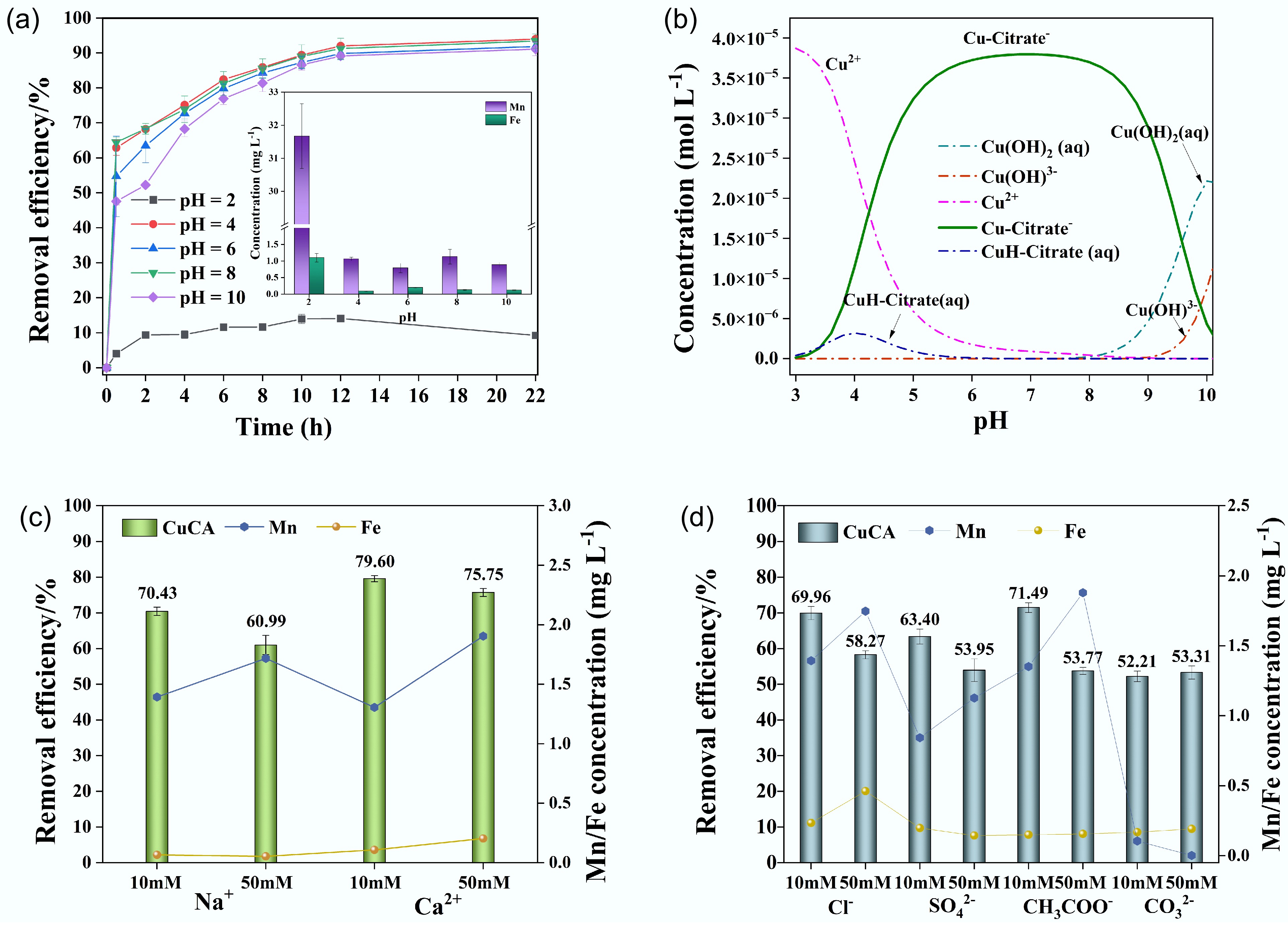

The pH of the solution affects both the electrostatic interaction of adsorption and the speciation of metal ions. Figure 6a illustrates the effect of pH (ranging from 2 to 10) on the removal of CuCA by FMBC-600, while Fig. 6b shows the speciation of CuCA calculated using Visual MINTQE 3.1 software under different pH conditions. At pH 2, although copper exists predominantly as Cu2+, the removal rate was lower than 20%, coupled with 35 mg L−1 Mn and 1 mg L−1 Fe dissolution, indicating that the modified biochar is unstable under this acidic condition. From Fig. 6b, it is evident that Cu mainly exists in the form of CuH-CA at pH < 4 and CuCA− between pH 6 and 9, while it forms Cu(OH)2(aq) gel and Cu(OH)3− at pH > 10. As the pH increased from 4 to 10, the removal rate was 96.2%, 93.0%, 95.7%, and 93.0%, respectively. The surface of FMBC-600 was electronegative (Supplementary Table S3), and copper existed in the form of negatively charged complexes. They both had electrostatic repulsion, leading to the reduced removal rate. However, the removal results showed that FEBC-600 still had excellent removal performance, indicating that the removal of CuCA does not only rely on electrostatic attraction. According to previous research, surface complex-formation and molecular attraction may also occur during the removal process[44]. Meanwhile, the final concentrations of Mn and Fe after dissolution were both lower than 1.0 and 0.5 mg L−1, respectively. These results illustrate that the wide range of pH changes did not significantly affect the removal ability of modified biochar. If we compare these findings with a study on the adsorption of copper citrate on chitosan[45], FMBC-600 demonstrated outstanding removal performance and notable stability over a wide pH range. In practical scenarios, wastewater is often acidic, and the results above indicate that manganese oxide-modified biochar has valuable applications in treating metal complexes in slightly acidic wastewater[46].

Figure 6.

(a) Removal performance under different pH values, (b) species of CuCA calculated by MINITEQ 3.1, (c) removal performance of coexisting cations, and (d) removal performance of coexisting anions.

Taking into account the fact that many ions are universally present in actual water, the presence of these ions may interfere with the removal efficiency of CuCA. The effect of coexisting ions on the removal performance of CuCA was tested (Fig. 6). It was observed that the presence of 10 mM Na+ slightly inhibited the removal of CuCA, and this inhibitory effect became more pronounced as the concentration increased to 50 mM. This suggests that competition for limited adsorption sites may occur, resulting in a decrease in Cu adsorption[47,48]. Regardless of the coexistence of high or low concentrations of Ca2+, the degree of inhibition of CuCA removal remained similar. However, with increasing concentrations of Na+ and Ca2+, the dissolution concentration of Mn increased, while the stability of ferric oxide remained unaffected. As depicted in Fig. 6d, the presence of 10 mM Cl−, SO42−, CO32−, and CH3COO− slightly inhibited the removal of CuCA, whereas severe inhibition occurred and the Mn dissolution concentration increased at 50 mM. The influence of coexisting anions on the removal of CuCA may stem from the high concentration of anions affecting the interaction between CuCA and FMBC-600, as well as competition for active sites, thereby impacting the removal rate and Mn dissolution concentration[49]. To quantify the affinity of the adsorbent for CuCA in the competitive adsorption process under the coexistence of various ions, the distribution coefficient (Kd) was used. Table S4 calculates the adsorption affinity of FMBC-600 for different ions. The highest Kd value indicates no significant effect on the removal rate[50]. For instance, when coexisting with Ca2+, the Kd value is the highest, which is consistent with the experimental results.

The recycling performance

-

The recycling performance of adsorbents is an important consideration factor for future applications. Supplementary Fig. S4 analyzes the removal performance of the modified biochar through two cycles of regeneration. As the number of cycles increased, the removal rate of CuCA gradually decreased. After the second cycle, the removal rate could reach about 80%, with a low dissolution concentration of iron and manganese, indicating that the removal effect of the modified biochar was relatively stable. However, there was a significant loss in the quality of the modified biochar. Thus, the results above indicate that FMBC-600 can be regenerated using an alkaline solution, but its reusability needs to be improved. According to abundant research, it is known that magnetic adsorption can effectively avoid quality loss or may increase the particle size of adsorbents while ensuring adsorption efficiency.

The reaction kinetics and isothermal adsorption model

-

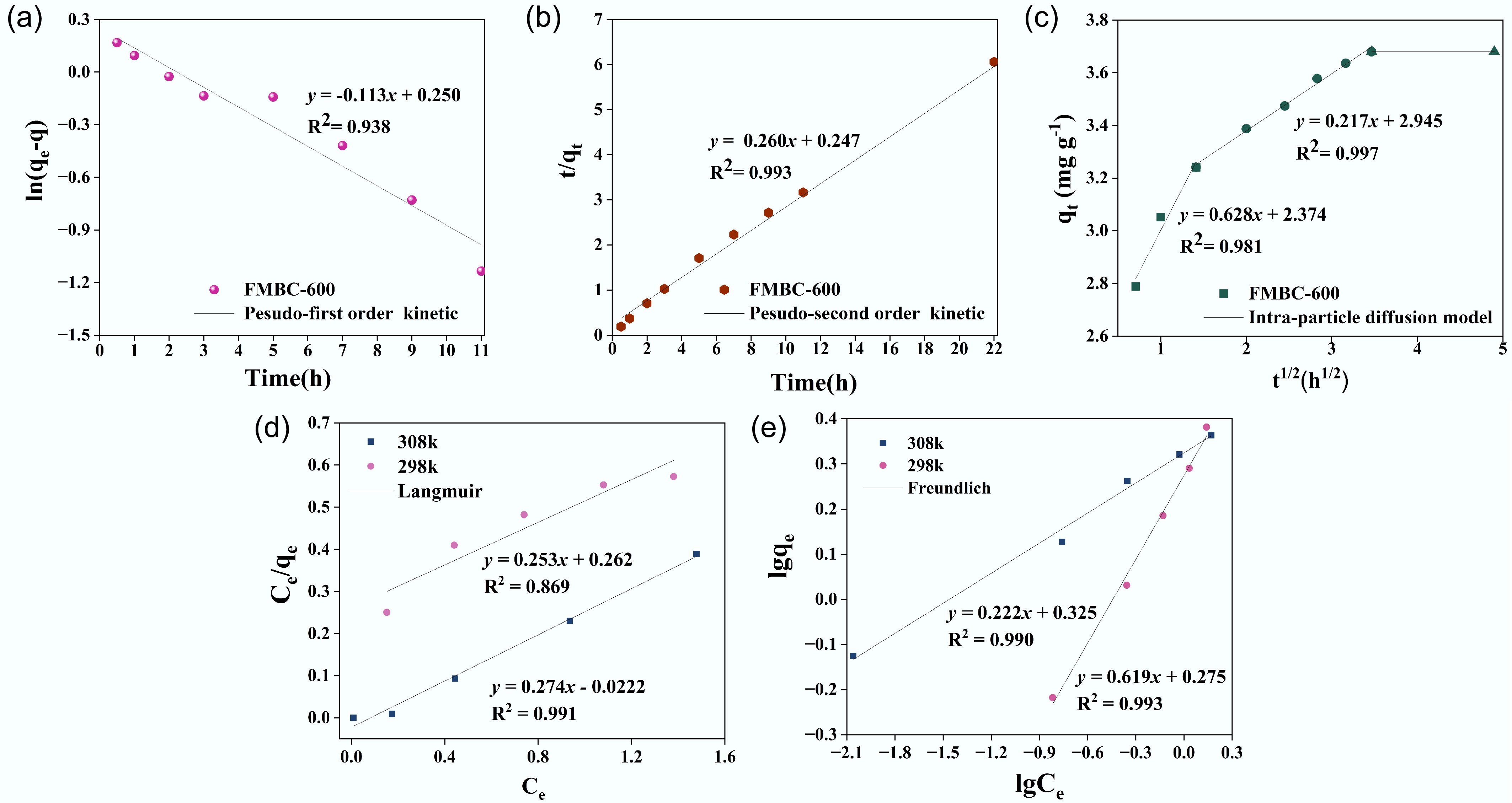

The fitting results of the pseudo-first-order kinetic, pseudo-second-order-kinetic, and internal diffusion kinetic models are depicted in Fig. 7, and the fitting parameters are shown in Supplementary Table S5. The removal process was more consistent with pseudo-second-order kinetics (R2 > 0.99), and the calculated qe value (3.852 mg L−1) closely matched the experimental qe value (3.794 mg L−1). This suggests that the main rate-limiting step may be the chemical adsorption of CuCA on FMBC-600; however, combined with the change in material properties, chemical adsorption may be involved in the effect of Mn–O or Fe–O[51,52]. The internal diffusion kinetics, as shown in Fig. 7c, indicated a multilinear relationship, suggesting an uninterrupted adsorption process with multiple steps for the adsorption of CuCA on FMBC-600. The first curve (within 2 hours) represented the adsorption of CuCA on the surface, where a significant driving force was generated for CuCA to diffuse from the solution to the external surface of the adsorbent. This was due to the high initial CuCA concentration, resulting in a large concentration gradient[53]. The diffusion rate in this stage was primarily determined by molecule diffusion and film diffusion[54]. In Stage Two, indicated by a low slope, CuCA transferred from the external surface to the pore channels, with intra-particle diffusion becoming the dominant process. Finally, in Stage Three, adsorption–desorption equilibrium gradually established as the CuCA concentration declined. Thus, the removal of CuCA by FMBC-600 may involve both physisorption and chemisorption processes.

Figure 7.

(a) Pseudo-first-order kinetics, (b) pseudo-second-order kinetics, (c) internal diffusion kinetics, (d) Langmuir isotherm, and (e) Freundlich isotherm.

Further analysis was conducted by obtaining the isothermal adsorption curve through fitting the adsorption of CuCA by FMBC-600 (Fig. 7c, d, Supplementary Table S6). The Langmuir model assumes that the adsorption process is monolayer adsorption with a uniform distribution of the adsorption sites, but these assumptions are rarely valid for all adsorbents, which is its weakness. The Freundlich model describes monolayer adsorption when chemisorption is the primary adsorption mechanism, whereas it describes multilayer adsorption when physisorption is the primary mechanism. However, the linearization process of the model results in a certain loss of accuracy[55]. In the study, the Langmuir and Freundlich models were employed to describe the adsorption processes of single and multiple molecular layers, respectively. In Fig. 7c, d, it is evident that the Freundlich model better explained the removal process (R2 > 0.99), indicating that the removal process was influenced by the nonuniform active sites of FMBC-600[56]. Generally, a value of n in the range of 1−10 suggests favorable adsorption effects. In this research, the value of n fell within this range, indicating that the adsorption of CuCA by FMBC-600 was favorable. Furthermore, according to the Langmuir model, the maximum adsorption capacity qm increases with increasing temperature, suggesting that high temperatures are beneficial for the removal of CuCA[57]. Compared with resin, chitosan, activated carbon, and other modified biochar in terms of adsorbent dosage and adsorption time (Table 2), the ferromanganese-modified biochar prepared in this study exhibited more efficient removal ability and superior stability[42,44,45,58,59].

Table 2. Comparison of present adsorbents with reported work

Adsorbent Contact time (h) Dosage qe Ref. Magnetic anion exchange resin and magnetic cation exchange resin 24 1.0 and 0.25 g L−1 / [42] Manganese oxide-modified biochar 24 1.0 g L−1 3.54 mg g−1; pH = 7.8 [44] Chitosan 72 4.96 mmol g−1; pH = 6 [45] Manganese oxide-modified gasification of ash-derived activated carbon 24 2.0 g L−1 4.237 mg g−1; pH = 3 [57] Polymer-supported, nanosized, and hydrated Fe(III) oxides 3 2.0 g L−1 with 40 mM H2O2 / [58] FMBC-600 22 1.0 g L−1 3.79 mg g−1; pH = 7.8 This study -

The materials discussed herein were prepared by a simple method and proved to be efficient in the removal of CuCA. Hopefully, they can by extended for an efficient and environmentally friendly approach for the removal of metal complexes from water and soil. The modification of biochar with ferromanganese oxide through impregnation and high-temperature calcination significantly enhanced the removal efficiency of CuCA. The surface of the modified biochar was dispersed with uniformly sized ferromanganese oxide particles. The ferromanganese oxide-modified biochar demonstrated excellent adsorption capacity, achieving a Cu removal efficiency of 99.5% (qe = 3.794 mg g−1) at a CuCA concentration of 10 mg L−1. Moreover, it showed high efficiency and stability over a wide pH range. The adsorption behavior of modified biochar was best described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and the Freundlich isotherm adsorption model. The removal mechanism involved multiple processes, including physical adsorption by the abundant pore structure and chemical adsorption of oxygen-containing functional groups.

The excellent removal performance and the low-cost preparation process are very attractive for larger-scale application. Undeniably, many more systematic explorations, such as the stability of modified biochar, are demanded for the broader modification of biochar in the removal of metal complexes. Meanwhile, the removal mechanism of metal complexes needs further in-depth research in terms of analyzing the relationship between iron oxides and manganese oxides.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/bchax-0025-0001.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: methodology, software, writing − original draft: Zhu Y; visualization: Lei X; funding acquisition: Fan W; experiment, data curation: Zhu Y, Lei X; formal analysis: Zhu Y, Li Y; supervision: Fan W, Liu J; writing − review and editing: Zhu Y, Fang W, Liu J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 41977352 and 42177240), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Higher Education Science and Technology Research Project (Grant No. NJZZ23079), Basic Research Business Fees for Universities Directly under Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Grant No. JY20220163), Scientific Research Project of Inner Mongolia University of Technology (Grant No. ZY202115), and the project of Inner Mongolia "Prairie Talents" Engineering Innovation Entrepreneurship Talent Team.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Ferromanganese oxide-biochar exhibited excellent remove capacity for CuCA.

Modified biochar has remarkable stability in wide pH and coexisting ions.

The CuCA removal mechanism involved chemisorption and physisorption.

The high efficiency and easy preparation of biochar extended its application.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Table S1 The element contents of BC, BC-600, FMBC-600, and FMBC-CuCA by EDS and XPS.

- Supplementary Table S2 TOC results under different medium.

- Supplementary Table S3 Zeta potential of BC、BC-600、FMBC-600 and FMBC-CuCA.

- Supplementary Table S4 The distribution coefficient Kd value.

- Supplementary Table S5 The fitting parameters of reaction kinetics model.

- Supplementary Table S6 The fitting parameters of isothermal adsorption model.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 XPS spectrum of BC, BC-600, FMBC-600, FMBC-CuCA: C 1s (a) and O1s (b).

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The Cu concentration (a) and Mn dissolution concentration (b) varied with time under different dosage of modified biochar.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 The FE-SEM image of FMBC-CuCA.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Cyclic utilization performance of FMBC-600.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu Y, Lei X, Liu J, Li Y, Fan W. 2025. Enhanced adsorption of copper citrate complexes by ferromanganese oxide biochar from water: performance and mechanism. Biochar X 1: e004 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0001

Enhanced adsorption of copper citrate complexes by ferromanganese oxide biochar from water: performance and mechanism

- Received: 15 June 2025

- Revised: 20 July 2025

- Accepted: 01 August 2025

- Published online: 14 October 2025

Abstract: The removal of metal complexes from water is more challenging compared with metal ions due to their stable structure. This study developed an efficient ferromanganese oxide-modified biochar and explored the preparation conditions in detail. The surface of ferromanganese oxide-modified biochar was uniformly loaded with 100 nm nanoparticles, mainly comprising Mn3O4 and (FeO)0.099(MnO)0.901, and exhibited excellent copper citrate (CuCA) adsorption capacity. The removal rate of CuCA at an initial concentration of 10 mg L–1 by 1 g L–1 modified biochar reached 99.5% for Cu and 92.6% for total organic carbon (TOC), with a copper adsorption capacity of 3.79 mg g–1. The mechanisms of using modified biochar to remove CuCA include chemical adsorption at the bimetallic oxide's active sites and oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of the biochar, as well as physical adsorption due to the porous structure of biochar. The modified biochar has significant potential for development in the removal of metal complexes in water with the advantage of efficient and easy preparation, good performance, and stability across a wide pH range and with some coexisting ions.

-

Key words:

- Adsorption /

- Ferromanganese oxide /

- Modified biochar /

- Metal complexes /

- Mechanism analysis