-

Carbon-based materials derived from sustainable biomass, particularly biochar, have attracted considerable attention for their broad range of multifunctional applications from energy storage and structural composites to catalysis, soil remediation, and water purification[1−3]. While extensive research has explored the environmental behavior, and chemical properties of biochar[4−6], existing studies have predominantly focused on powdered biochar, thereby disregarding its inherent hierarchical architecture. This architecture plays a pivotal role in retaining anisotropic properties that are critical for advanced load-bearing and flow-through applications. Consequently, research on the anisotropic mechanical properties of monolithic biochar remains a significant gap due to the disruption of natural microstructure, limiting its implementation in next-generation technologies.

The anisotropic hardness characteristics of biochar are predominantly governed by two critical factors: (1) feedstock selection; and (2) pyrolysis conditions control (e.g., temperature, time, and heating rate)[7−9]. Plant feedstocks with high lignin content and high density typically yield biochar with superior hardness. This phenomenon is attributed to the formation of stable aromatic carbon structures from lignin during pyrolysis—structures that better retain mechanical strength compared to those derived from cellulose and hemicellulose. Furthermore, the dense cellular structure facilitates the retention of a continuous carbon skeleton after carbonization, thereby enhancing anisotropic hardness. Videgain et al. pointed out that biochar derived from holm oak exhibited greater resistance to the applied forces than that from vine shoot[10]. Wallace et al. also reported that biochar derived from hemp possessed a higher Young's modulus but lower hardness than biochar produced from softwood chips[11]. Pyrolysis conditions significantly influence the ultimate quality parameters of biochar (e.g., fixed carbon content, ash ratio, and elemental composition) by modulating its physicochemical properties, including carbonization degree, pore structure, and surface functional group composition. These quality parameters act as mediating variables that directly determine the micromechanical properties of biochar, particularly its hardness. Notably, due to the distinct chemical composition (e.g., lignin/cellulose ratio) and morphological features (e.g., vascular bundle structure) of different biomass feedstocks, the correlation between pyrolysis conditions and hardness performance exhibits a strong feedstock dependency. For example, Das et al. demonstrated that a combination of higher heat treatment temperatures (≥ 500 °C) and longer residence time (~ 60 min) increased both the hardness and modulus of biochars derived from seven types of waste materials[12]. In contrast, de Abreu Neto et al. found that the density, dynamic hardness, and stiffness of charcoal tended to decrease with increasing temperature[13]. However, these studies overlook three critical dimensions: (i) orientation-dependent anisotropy (i.e., axial vs transverse); (ii) species-specific mechanical responses under identical pyrolysis conditions; and (iii) disconnects between nanoscale intrinsic properties and bulk-scale behavior. Critically, no study has utilized monolithic biochar—where the native wood structure is preserved—to investigate its true anisotropy. This represents a notable oversight, as monolithic biochar retains the hierarchical porosity and fiber alignment that are essential for directional strength in functional devices like electrodes or filters.

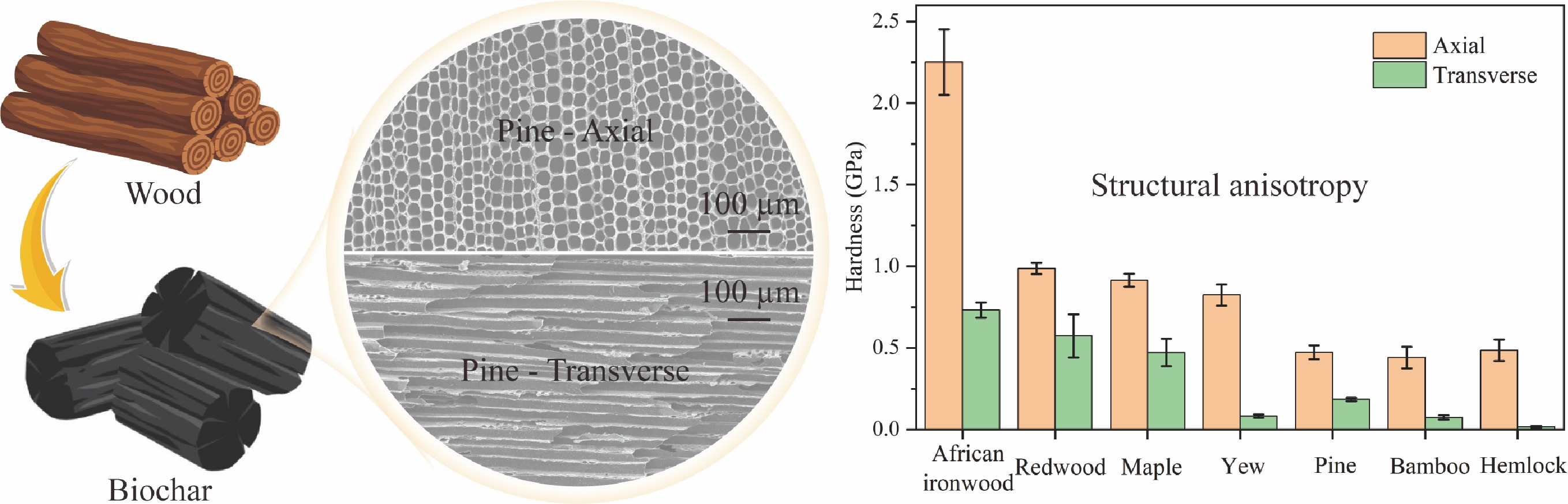

This work bridges these gaps through the first multiscale mechanical analysis of crack-free monolithic biochars derived from seven wood species (maple, pine, hemlock, African ironwood, redwood, bamboo, yew) pyrolyzed at 600, 800, and 1,000 °C. Specifically, orientation-dependent hardness is quantified via micro-indentation, establish a correlation between anisotropy and both bulk density and carbon microstructure, and decouple intrinsic properties (assessed via nano-indentation) from structural properties (evaluated via micro-indentation). The present approach reveals two transformative insights: first, preserving monolithic structure exposes extreme anisotropy that is unseen in studies on powdered biochar—exemplified by African ironwood biochar pyrolyzed at 1,000 °C, which exhibits axial hardness of 2.25 GPa vs a transverse hardness of 0.73 GPa; second, we demonstrate a fundamental scale divergence is demonstrated: while nanoscale intrinsic hardness is uniform across all samples (3.64–4.41 GPa), microscale anisotropy varies drastically (e.g., transverse hardness as low as 0.017 GPa in hemlock), confirming that mechanical differences arise from pore architecture and orientation effects, rather than intrinsic properties and material gradients.

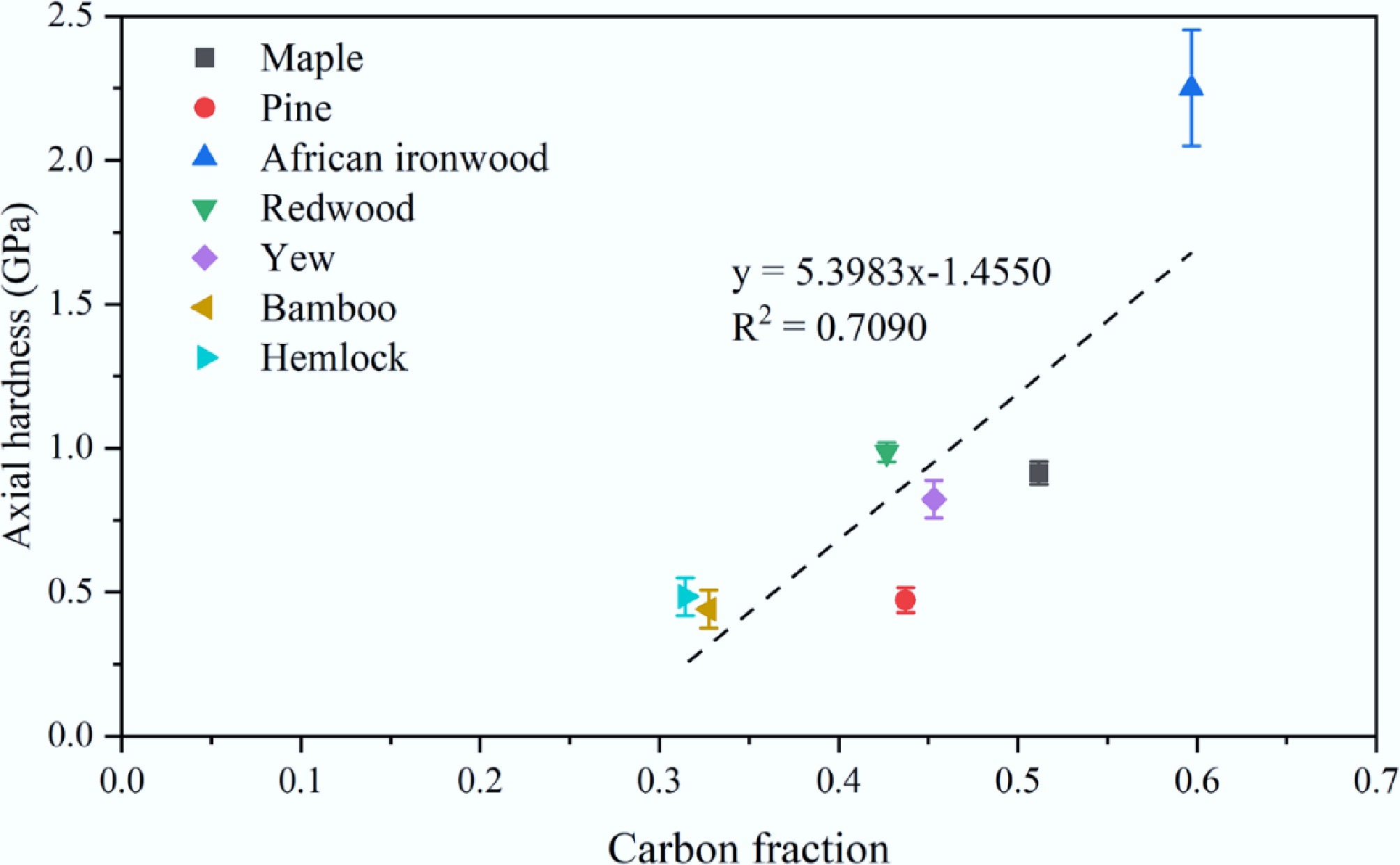

These results redefine the design principles for anisotropic carbon materials. By correlating axial hardness with bulk density (R2 = 0.84), and SEM-derived carbon fraction (R2 = 0.71), microstructure-property relationships are established that enable the rational optimization of biochar monoliths. This work advances the development of applications requiring directional mechanical performance, including axial-reinforced composites for lightweight structures, stress-tolerant electrodes in energy devices, and mechanically stable filters for high-pressure systems—ultimately accelerating the deployment of sustainable carbon materials in next-generation technologies.

-

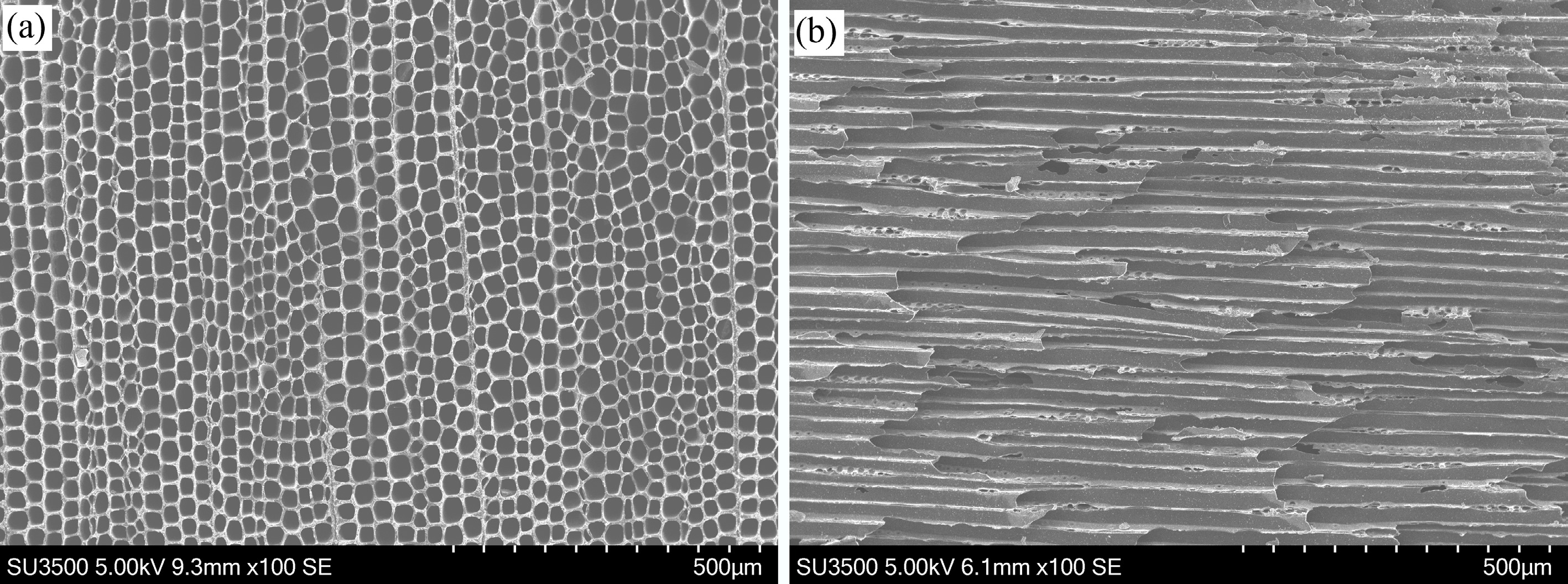

Crack-free monolithic biochar samples were synthesized using seven wood species as feedstocks: maple (Acer saccharum), pine (Pinus spp.), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), African ironwood (Olea capensis), redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), bamboo (Bambusoideae), and yew (Taxus baccata). Kiln-dried lumber (ambient moisture < 12%) was cut into 20 mm × 20 mm × 10 mm blocks, with the natural grain orientation preserved. Biochar production was conducted in accordance with US Patent 6,124,028, using a Carbolite Gero CTF 12/65 tube furnace under N2 atmosphere (200 mL/min). The thermal protocol was as follows: (1) heating at a ramp of 5 °C/min to the target temperature (600, 800, or 1,000 °C); (2) isothermal holding at the target temperature for 2 h; and (3) controlled cooling (ramping down at 10 °C/min to 200 °C, followed by natural cooling to RT). Maple and pine were processed at all three temperatures, while the remaining species were only pyrolyzed at 1,000 °C. Figure 1 shows the SEM images of pine biochar in axial and transverse orientations, as examples. The transverse cutting angle was estimated by analyzing the dimensions of open tracheids in SEM images.

Figure 1.

SEM images of pine biochar (a) produced at 1,000 °C in axial, and (b) transverse orientations.

Sample preparation for indentation

-

Monoliths were sectioned into 5 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm cubes using a Buehler Isomet low-speed saw. Samples were vacuum-infiltrated (10−3 bar, 30 min) with LECO epoxy/hardener (5:1 w/w) to minimize pore infiltration. The infiltrated samples were cured at room temperature for 24 h and stabilized for 48 h. Polishing employed sequential SiC sandpaper (400→800→1,200 grit; 150 rpm), followed by 1 μm diamond suspension. Surface roughness (Ra < 0.05 μm) was verified via white-light interferometry.

Micro-indentation testing

-

Hardness measurements were conducted using a LECO LM310AT microhardness tester (Vickers indenter, 136° pyramid angle). Calibration used certified reference blocks (HV 0.5/1.0 GPa; daily error < ± 2%). Species-specific loads were applied: 300 N (maple/pine) and 100 N (hemlock/bamboo). Ten indents per sample (five axial + five transverse) were performed with spacing ≥ 3× diagonal length (ISO 6507-1). Regions with pores were excluded via SEM pre-screening. Hardness calculated as Eq. (1):

$ HV=\dfrac{\mathrm{F}}{\mathrm{S}}=\dfrac{2F\mathrm{sin}\dfrac{\alpha }{2}}{g{d}^{2}}\cong 0.1891\dfrac{F}{{d}^{2}} $ (1) where, HV is the Vickers hardness number, F is the testing load (N), S is the surface area of the indent (mm2), α is the face angle of the indent (136°), d is the mean of the indent diagonals (m), and g is the standard acceleration due to gravity (9.80665 m s−2).

Nano-indentation testing

-

Intrinsic hardness (HIT) was characterized using KLA iMicro nanoindenter equipped with a diamond Berkovich tip (Synton-MDP, Switzerland). Test performed in accordance with ISO 14577, employing a constant quasi-static strain rate of 0.05 s−1. The maximum depth of indents was limited to 500 nm to minimize the edge effects, while thermal drift was controlled under 0.1 nm/s. On each sample, matrices of 5 * 5 were measured at three different locations. The locations of indentation were calibrated using an optical microscope, and only indentation made clearly on cell walls was included in the results. Hardness was calculated using the Oliver-Pharr method, with continuous stiffness measurement, as shown in Eqs (2) and (3).

$ {h}_{c}=h-\varepsilon \dfrac{P}{S} $ (2) $ {H}_{IT}=\dfrac{P}{{A}_{c}}=\dfrac{P}{f\left({h}_{c}\right)} $ (3) where, h is the indentation depth (nm), hc is the contact depth,

$ \varepsilon $ Bulk density and carbon fraction analysis

-

Bulk density (ρbulk = m/V) was derived from Mitutoyo caliper measurements (± 0.01 mm) and Mettler Toledo mass (± 0.0001 g; uncertainty < ± 3%). Carbon fraction (fC) was quantified from FEI Quanta 250 SEM images (10 kV) using ImageJ thresholding (180–255 grayscale = carbon; ± 5% RSD via triplicate analysis).

Uncertainty management

-

Uncertainty management for various types of tests is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Uncertainty management for various types of tests

Parameter Uncertainty source Mitigation Magnitude Micro-indentation Epoxy infiltration Vacuum impregnation + SEM exclusion ΔHV ≈ 0.116 GPa Nano-indentation Surface roughness Calibration of indentation positions + low indentation depth ± 3% Orientation Cutting angle deviation Sample preparation + surface parallelism check (optical) < 5° Carbon fraction SEM threshold sensitivity Multi-operator validation ± 5% RSD Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was assessed via ANOVA in OriginPro 2023. -

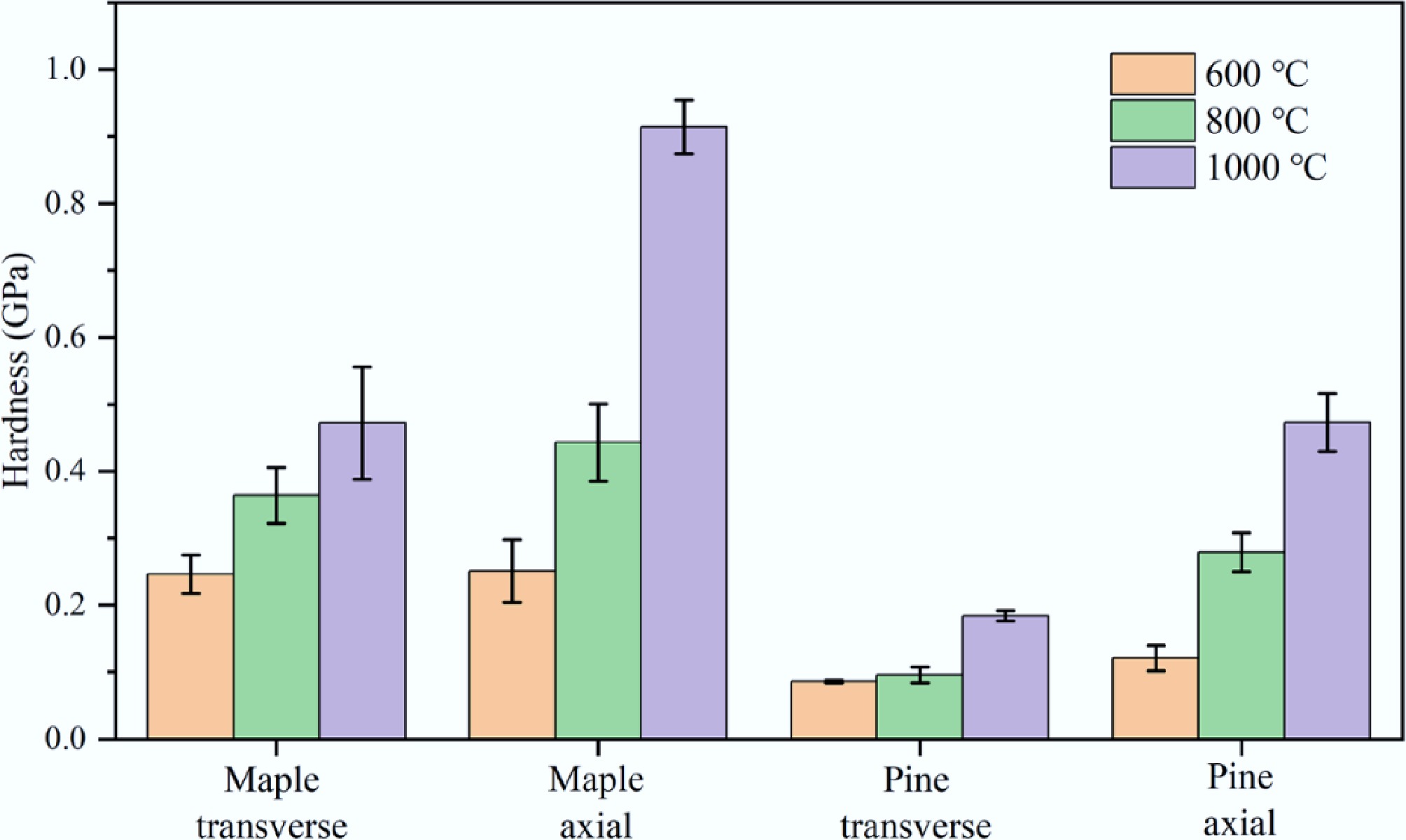

The hardness of biochar samples was measured across different wood species at different pyrolysis temperatures (600, 800, and 1,000 °C) in axial and transverse directions. The hardness values of maple and pine biochar at different pyrolysis temperatures are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2 for better visualization. Five tests were conducted at different areas for each sample, and the average hardness was calculated.

Table 2. Hardness of maple and pine biochar produced at 600, 800, and 1,000 °C in axial and transverse directions from micro-indentation testing

Sample Temperature

(°C)Transverse

hardness (GPa)Axial hardness

(GPa)Maple 600 0.246 ± 0.029 0.251 ± 0.047 800 0.364 ± 0.042 0.443 ± 0.058 1,000 0.472 ± 0.084 0.914 ± 0.040 Pine 600 0.086 ± 0.002 0.121 ± 0.019 800 0.096 ± 0.012 0.279 ± 0.029 1,000 0.184 ± 0.008 0.473 ± 0.043

Figure 2.

Hardness of maple and pine biochar produced at 600, 800, and 1,000 °C in axial and transverse directions.

In general, the hardness of maple and pine biochars increases with pyrolysis temperature. At 600 °C, both types of biochar samples exhibit lower hardness values. This is attributed to the incomplete carbonization of the wood structure, where the material remains partially in its original state and lacks full stabilization. At this temperature, the cellular framework of the wood undergoes only limited decomposition, and fails to transform into a denser carbon matrix, resulting in reduced hardness. At 800 °C, the hardness values increase significantly, corresponding to the greater extent of carbonization. Elevated temperature drives further thermal decomposition of the wood, promoting a denser and more stable structure. At 1,000 °C, the hardness reaches a maximum for both maple and pine biochar. This observation is consistent with the increased carbon content and enhanced structural densification with higher pyrolysis temperatures. Notably, pyrolysis at 1,000 °C promotes the formation of a more crystalline, ordered carbon network, significantly improving the hardness of the biochar.

When comparing the hardness values in the transverse and axial directions, the axial hardness consistently exceeds the transverse hardness across all temperatures for both maple and pine species. At 600 °C, the hardness values in both directions are similar due to the incomplete carbonization, which results in less pronounced anisotropy. However, as pyrolysis temperature increases, the axial and transverse hardness differential becomes increasingly pronounced. This can be explained by the preferential alignment and compaction of carbon structures along the axial direction during high-temperature pyrolysis, which enhances the mechanical strength. Notably, the axial hardness of maple biochar nearly doubles when the pyrolysis temperature increases from 600 to 1,000 °C, highlighting the significant impact of temperature on the material's anisotropic mechanical properties.

Species-specific hardness at 1,000 °C

-

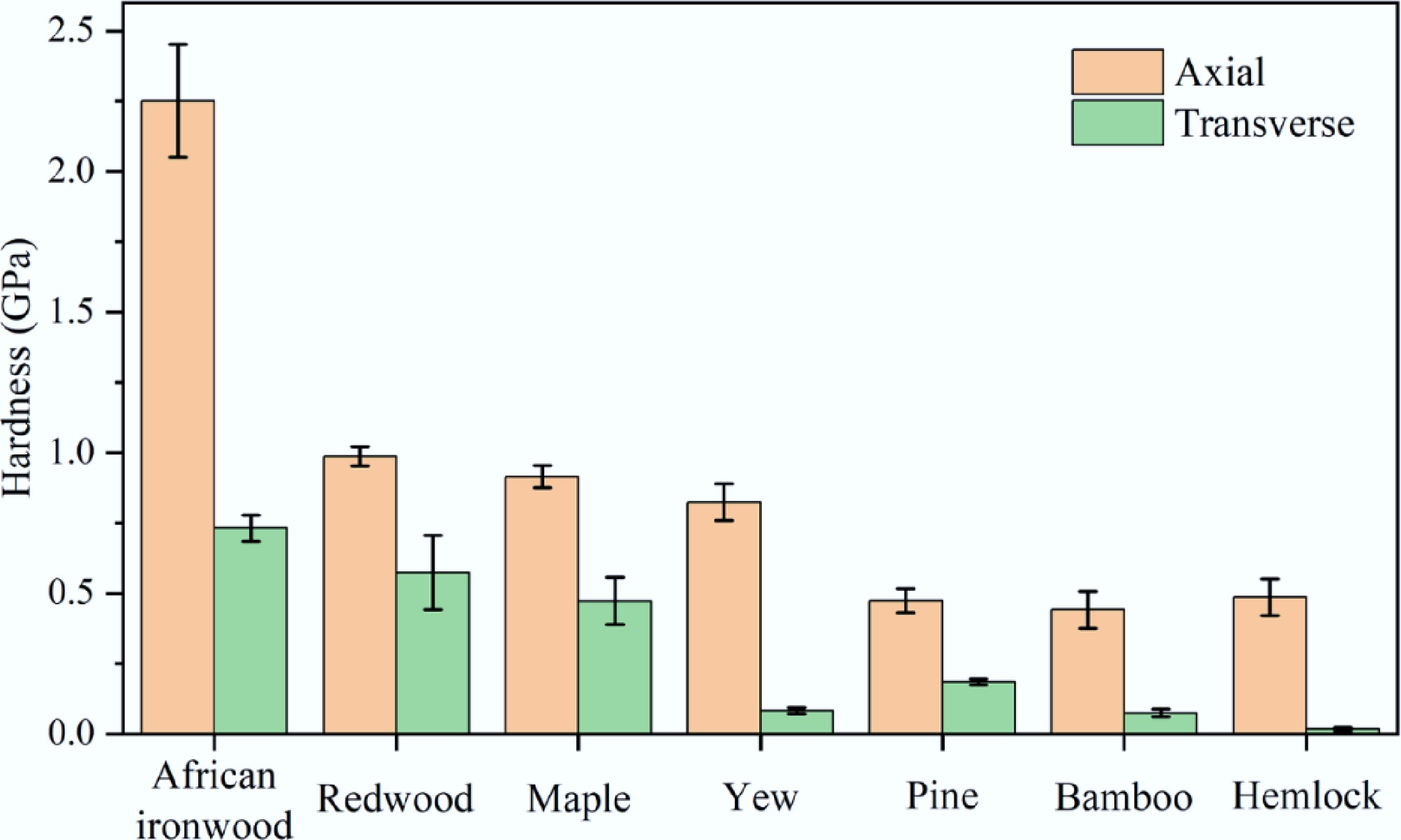

The hardness values varied not only with pyrolysis temperature but also with wood species. This section focuses on additional wood species pyrolyzed at 1,000 °C, including hemlock, bamboo, redwood, African ironwood, and yew. Table 3 summarizes axial and transverse hardness values for these species, while Fig. 3 presents a comparative bar chart among different wood species.

Table 3. Hardness of biochar in axial and transverse directions for different wood species pyrolyzed at 1,000 °C

Wood species Axial hardness

(GPa)Transverse

hardness (GPa)Anisotropy

(A/T)African ironwood 2.251 ± 0.201 0.731 ± 0.046 3.08 Redwood 0.987 ± 0.034 0.574 ± 0.132 1.72 Maple 0.914 ± 0.040 0.472 ± 0.084 1.94 Yew 0.823 ± 0.065 0.082 ± 0.011 10.04 Pine 0.473 ± 0.043 0.184 ± 0.008 2.57 Bamboo 0.441 ± 0.066 0.074 ± 0.013 5.96 Hemlock 0.485 ± 0.065 0.017 ± 0.006 28.53

Figure 3.

Hardness of biochar in axial and transverse directions for different wood species pyrolyzed at 1,000 °C.

As shown in Fig. 3, African ironwood exhibits the highest hardness values in both axial and transverse directions at 1,000 °C, consistent with its highly dense and compact structure. Redwood, maple, and yew follow in descending order of hardness. Redwood and maple demonstrate a balanced axial and transverse hardness, making them versatile for applications requiring consistent performance across orientations. In contrast, yew shows moderate axial hardness (0.823 ± 0.065 GPa) but significantly lower transverse hardness, indicating pronounced anisotropy, likely due to its grain alignment and structural composition. Such balanced axial and transverse hardness in redwood and maple supports their potential use in applications requiring consistent performance across orientations, such as monolithic catalyst supports and certain biomedical scaffolds.

Pine, bamboo, and hemlock demonstrate modest mechanical strength. Pine exhibits marginally higher axial hardness (0.473 ± 0.043 GPa) compared to bamboo (0.441 ± 0.066 GPa), but its transverse hardness (0.184 ± 0.008 GPa) is significantly greater than that of bamboo (0.074 ± 0.013 GPa). This suggests that pine biochar retains greater structural integrity across different orientations compared to bamboo biochar, whose vascular bundle-dominated architecture leads to significantly weaker transverse mechanical performance. Hemlock, on the other hand, exhibits the lowest hardness values overall, with an axial hardness of 0.485 ± 0.065 GPa, and a transverse hardness of only 0.017 ± 0.006 GPa. These findings correlate with hemlock's porous and less carbon-dense composition, limiting its suitability for applications demanding high mechanical strength.

Bulk density and carbon fraction correlations

-

Bulk density refers to the unit mass of biomass per unit volume, including the void spaces and pores within the material. Biochar generally exhibits a lower bulk density than the original wood due to structural arrangement during pyrolysis. At high pyrolysis temperatures, biochar undergoes densification, which reduces porosity due to thermal degradation. To measure the bulk density, each biochar sample was cut into a perfect cube. Sandpaper was used to polish the surfaces to ensure dimensional uniformity and suitability for accurate measurements. A Vernier calliper was used to measure the dimensions of each biochar sample. The volume of each sample was calculated by multiplying its length, width, and height. A balance was used to measure the mass of each sample, and the bulk density was determined by dividing the mass by the calculated volume. The bulk density and the original wood density are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Bulk density of different wood biochar under different pyrolysis temperature

Species Pyrolysis

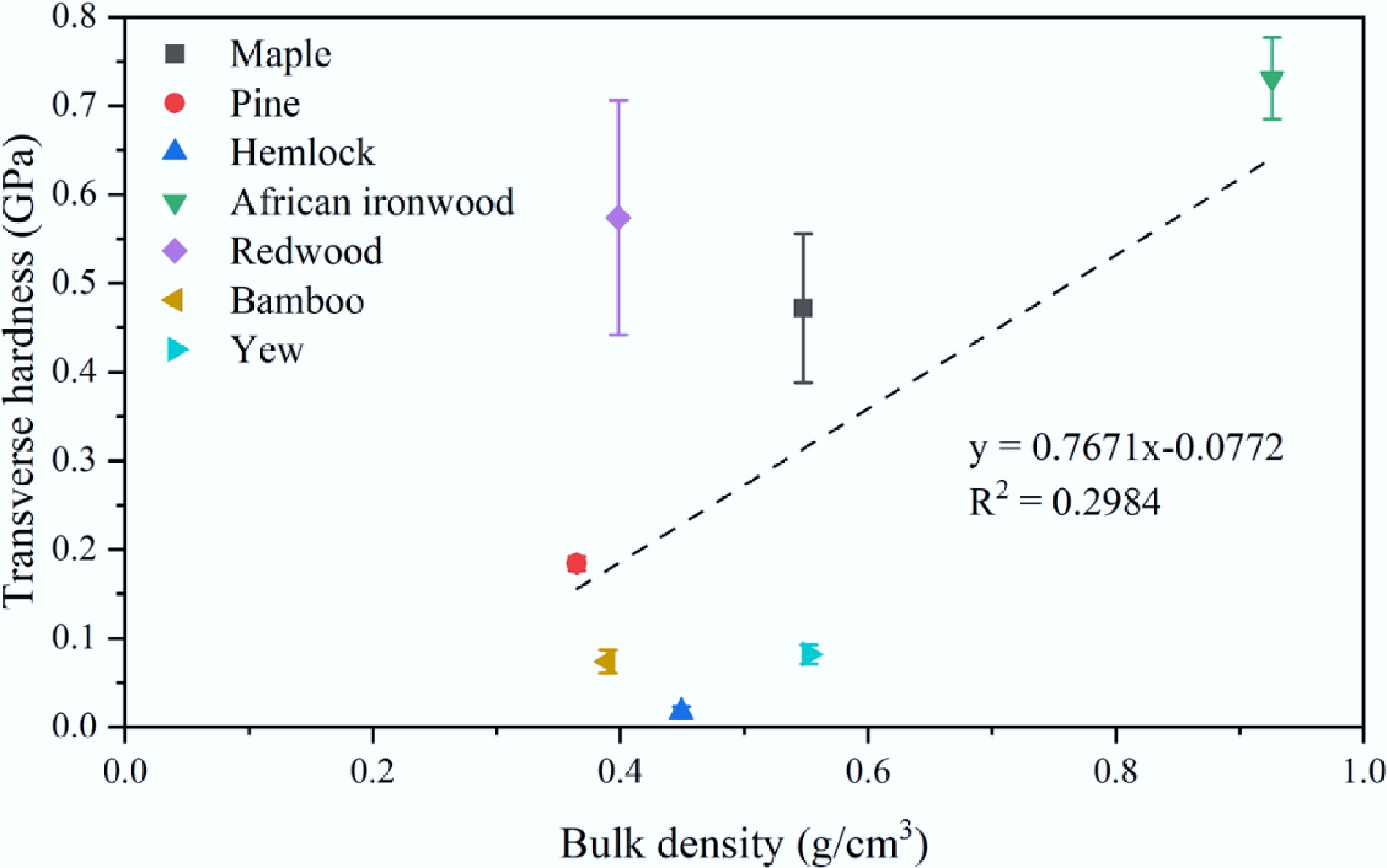

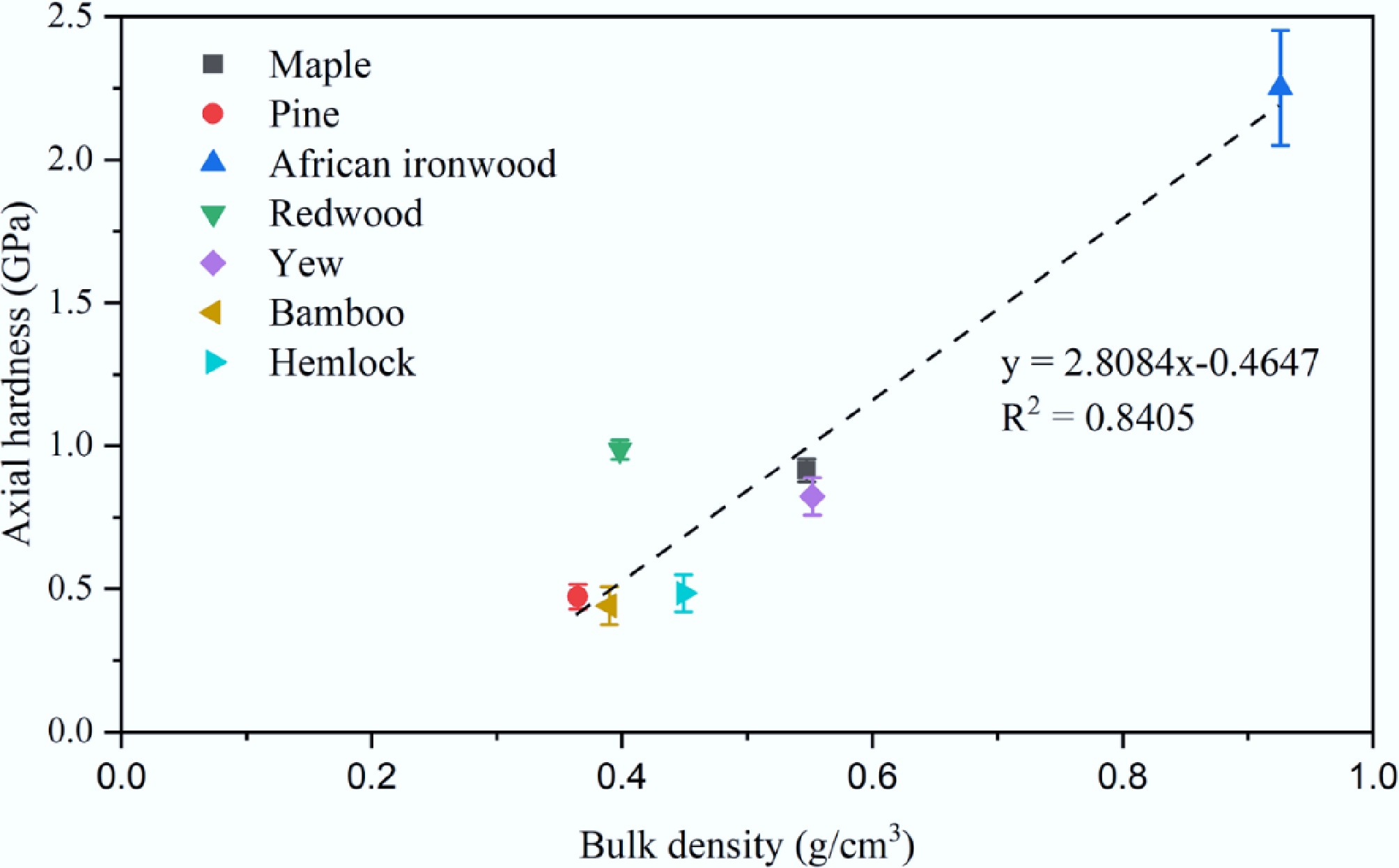

temperature (°C)Bulk density (g/cm3) Wood density (g/cm3) Maple 600 0.4125 0.78 800 0.4423 1,000 0.5474 Pine 600 0.3002 0.41 800 0.3509 600 Pine 1,000 0.3647 African ironwood 1,000 0.9260 1.35 Redwood 1,000 0.3983 0.68 Yew 1,000 0.5521 0.72 Bamboo 1,000 0.3898 0.76 Hemlock 1,000 0.4490 0.55 The relationship between hardness and bulk density reveals the significant anisotropy in biochar's mechanical behavior. As illustrated in Figs 4 and 5, a linear correlation was observed between hardness and bulk density, with substantially stronger correlation in the axial direction (R2 = 0.8405) compared to the transverse direction (R2 = 0.2981). In the axial direction, there is a strong linear relationship between hardness and bulk density. The carbonized cell walls in this direction are compact and aligned, providing uniform resistance to deformation under load. Increased bulk density corresponds to reduced porosity and enhanced structural cohesion, leading to greater axial hardness. In contrast, the correlation in the transverse direction is significantly weaker. The transverse surface exposes both solid cell wall material and voids, which disrupt the uniform transmission of force during indentation, resulting in greater variability in measured hardness.

Figure 4.

Relationship between transverse hardness and bulk density of biochar for different species produced at 1,000 °C.

Figure 5.

Relationship between axial hardness and bulk density of biochar for different species produced at 1,000 °C.

Furthermore, the transverse structure of biochar is additionally sensitive to cutting angles during sample preparation. In the transverse orientation, the biochar surface primarily reveals the cross-sections of lumens and cell walls. The cutting angle determines how these features are exposed. Deviations from a perfectly perpendicular cutting plane induce uneven distributions of solid material and voids within the test area. This variability impacts hardness measurements, as the probe may encounter differing proportions of solid carbonized cell walls and empty spaces. Another contributor to the weaker correlation in the transverse direction is the that the transverse hardness is more influenced by edge effects[14]. Imperfect cutting angles of samples may distort the shapes and sizes of lumens, exacerbating variability. Such distortions may contain sharp edges or uneven material distributions, which affect the interaction of the indentation probe with the surface, thereby reducing the reliability of bulk density as a predictor of hardness.

In contrast, the axial orientation, characterized by long, continuous cell walls, exhibits less sensitive to these edge effects. The alignment of carbonized cell walls in this orientation minimizes structural inconsistency, ensuring more consistent interactions between the indentation probe and the material. Consequently, hardness measurements in the axial orientation are more consistent and strongly correlated with bulk density, reinforcing the anisotropic mechanical behavior of biochar.

Hardness, as a mechanical property, is governed by structural features ranging from micro to macro scales, including porosity, sp3/sp2 bonding ratio, crystallinity, size of ordered clusters, density of amorphous domains, remaining O/H, and spatial gradient, among others. Bulk density, conversely, is primarily determined by the volume of tracheids and vessels, which are highly variable across wood species. It is also affected by the density of the amorphous carbon matrix, which is nano-porous. Consequently, monolithic wood biochar is heterogeneous on multiple spatial scales. Notably, the low but positive coefficient (R2 = 0.84) demonstrates both the complexity of monolithic biochar hardness and the importance of bulk density, confirming the importance of bulk density in controlling hardness and offering a mechanism for strengthening monolithic biochar. While biochar density correlates strongly with precursor wood density (Table 4), it can be increased via densifying precursor wood after removing lignin[15].

The carbon fraction was estimated using ImageJ, which is represented by the proportion of the white area in SEM images corresponding to carbonized regions. While this method does not provide precise chemical composition, it offers a visual approximation of the extent of carbonization across different biochar samples. The carbon fraction data for all biochar samples are shown in Table 5. To evaluate the influence of carbonization on the axial hardness at 1,000 °C, the relationship between the axial hardness of biochar and carbon content was analyzed, revealing a linear correlation with an R2 value of 0.709 (shown in Fig. 6).

Table 5. Summarized carbon fraction of different biochar species

Biochar species Carbon fraction African ironwood 0.5967 Maple 0.5116 Yew 0.4532 Pine 0.4373 Redwood 0.4268 Bamboo 0.3274 Hemlock 0.3144 African ironwood exhibited the highest carbon fraction (0.5967), followed by maple (0.5116), and Yew (0.4532). Pine, redwood, bamboo, and hemlock showed progressively lower carbon fractions, with hemlock exhibiting the lowest value (0.3144). The trend aligns with the observed axial hardness values. Species with higher carbon fractions, such as African ironwood and Maple, consistently demonstrated greater hardness, while those with lower carbon fractions, such as hemlock (0.3144) and bamboo (0.3274), exhibited lower hardness. These results highlight the significant influence of macro-level carbon fraction on the mechanical properties of biochar, particularly in the axial direction.

Moreover, the consistent superiority of axial hardness over transverse hardness observed in this study, underscores the anisotropic nature of monolithic biochar, which aligns with the inherent structural anisotropy of lignocellulosic materials, where the axial direction is reinforced by aligned cellulose fibers, leading to greater stiffness and resistance to deformation.

Intrinsic hardness obtained with nano-indentation

-

The hardness of the cell wall was obtained via nano-indentation. As the cell walls of biochar consist of nanoporous carbon and are free of tracheids and vessels, their hardness is considered intrinsic to the carbon material itself. Table 6 presents intrinsic hardness values, obtained with nano-indentation tests for maple, pine, and bamboo biochars. Compared to the intrinsic values the hardness values obtained with micro-indentation are approximately ten times smaller. This significant difference stems from fundamental differences in measurement methodologies. Micro-indentation measures average hardness across a broad area of the biochar, which includes tracheids and possibly even vessels. In contrast, nano-indentation targets a much smaller area, such as cell walls, that are free of macropores. Additionally, the edge effects are mitigated through optimized procedural adjustments. Consequently, intrinsic hardness values fall in a small range (3.64–4.41 GPa), and are independent of both wood species and orientation.

Table 6. Intrinsic hardness measured using nano-indentation technique for maple, pine, and bamboo biochar created at 1,000 °C

Species Pyrolysis

temperature (°C)Axial hardness

(GPa)Transverse

hardness (GPa)Maple 1,000 4.04 ± 0.16 − Pine 1,000 4.41 ± 0.05 4.38 ± 0.71 Bamboo 1,000 − 3.64 ± 0.52 Nano-indentation measurement revealed significant variability in graphite hardness. Flexible graphite exhibits hardness values ranging from 0.0058 to 0.016 GPa depending on the applied load[16]. Pradhan et al.[17] found that graphite flakes demonstrate higher hardness at 2 GPa. Richter et al.[18] reported 2.35 GPa for highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG). In contrast, a powdered activated carbon was evaluated using nano-indentation and found to be very soft (0.006 GPa)[19]. Incidentally, the hardness of African ironwood biochar is comparable to that of HOPG and mild steels (1–3 GPa)[20,21].

Visible Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) and analyses were conducted on pine and maple biochar samples pyrolyzed at 600, 800, and 1,000 °C[22]. The extensive background Raman signals in low-temperature (600 °C) samples confirmed residual organic matter, such as H and OH[23]. After subtracting the photoluminescence contributions, Raman spectra revealed an increase in the intensity ratio of the D (1,350 cm−1) and G (1,650 cm−1) bands (ID/IG) as the pyrolysis temperature increased. According to Miccoli et al.[24], the elevation in the ID/IG ratio could be attributed to the reduced sp3 content in amorphous carbon (a-C). XRD analyses[22] revealed the increased size of graphitic nanocrystals (graphitization) with rising temperature, consistent with the observed reduction in sp3 content in the a-C matrix. Specifically, the crystallites in pine biochar produced at 1,000 °C exhibited a larger (40%) basal plane {100} than those in maple biochar produced at the same temperature, despite their similar basal plane stacking height {002}. The intrinsic hardness of pine biochar produced at 1,000 °C was about 10% greater than that of maple biochar (Table 6). Notably, increased pyrolysis temperature resulted in a substantial increase in density (Table 4). As the temperature increases, the release of bond terminators (H and OH) enable carbon atoms to rearrange and local reconstruction, promoting denser cell walls, which is another factor contributing to increased intrinsic hardness. Given the fundamental role of sp2 hybridization in graphite formation, further work is required to decouple the respective influences of carbon bonding structure (crystallinity), and nano-porosity (densification) on intrinsic hardness.

This study, focusing on the anisotropy of monolithic biochar hardness and its macrostructural dependence, reveals a positive correlation between hardness and pyrolysis temperature (600–1,000 °C). Biochar preparation conditions are known to influence the structure of biochar, with predictable impacts on biochar hardness. For example, slower heating rates (1–9 °C/min) and extended residence times facilitate a more complete carbonization and a robust carbon matrix, enhancing hardness[25,26]. Conversely, Gurtner et al.[8] reported a decreased compressive strength with increasing temperature for woody biomass pyrolyzed at 300–450 °C. Monolithic wood biochar (MWB) exhibits hierarchical, heterogeneous, and nanoporous structures. As an emerging functional material, MWB requires much more investigation for its structure-property relationships by leveraging the tools employed for widely used materials, such as metals and polymers.

-

This study establishes that mechanical anisotropy in monolithic biochar (axial/transverse hardness ratios ≤ 28.5×) originates from hierarchical cellular architecture rather than intrinsic cell wall properties. Nano-indentation confirms consistent intrinsic hardness (3.64–4.41 GPa) across wood species/orientations, whereas micro-indentation reveals pronounced structural anisotropy (0.017–2.25 GPa) with strong correlation to bulk density (R2 = 0.84), and carbon fraction (R2 = 0.71). Anisotropy arises from directional microstructure: axial strength derives from aligned lumens/dense cell walls, while transverse weakness reflects porous cross-sections prone to collapse. High pyrolysis temperatures enhance both hardness and anisotropy. Wood species selection dictates performance extremes: African ironwood achieves record axial hardness (2.25 GPa) due to high lignin density and tylose-filled vessels, whereas hemlock exhibits near-zero transverse hardness (0.017 GPa) attributed to open tracheids and low carbon fraction (fc = 0.31). Strong axial correlations confirm grain-direction deformation resistance scales with bulk density, while carbon fraction primarily governs cell wall load-bearing capacity. These relationships enable rational material selection: high-fc species (e.g., ironwood) for robust electrodes; low-anisotropy species (e.g., redwood, A/T = 1.72×) for uniform-flow filters. Decoupling intrinsic (nano) and structural (macro) properties facilitate the design of monolithic devices that leverage native wood anatomy for advanced applications.

-

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Qinyi Wang, Mohana Sridharan, and Lizhong Lang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Charles Jia, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data analysis, reviewed the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This work was supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and the Low Carbon Renewable Materials Centre at the University of Toronto.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Extreme anisotropy uncovered: Axial hardness exceeds transverse by up to 28.5× (hemlock, 1,000 °C).

African ironwood achieves mild steel-like axial hardness (2.25 GPa) — the highest for wood-derived biochar.

Axial hardness strongly correlates with bulk density (R2 = 0.84) and carbon fraction (R2 = 0.71).

Nano-indentation confirms uniform intrinsic (cell-wall) hardness (3.64–4.41 GPa), independent of species/orientation.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang Q, Ji Y, Sridharan MM, Lang L, Zou Y, et al. 2025. Unlocking extreme anisotropy in monolithic biochar hardness. Biochar X 1: e007 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0007

Unlocking extreme anisotropy in monolithic biochar hardness

- Received: 11 July 2025

- Revised: 02 September 2025

- Accepted: 14 September 2025

- Published online: 21 October 2025

Abstract: Monolithic biochar offers structural advantages over its powdered counterpart for advanced applications; however, a fundamental understanding of its mechanical properties remains a critical barrier to its rational design. This study aims to address this gap through a multiscale hardness analysis of crack-free monoliths derived from seven wood species pyrolyzed at 600–1,000 °C. Micro-indentation reveals extreme structural anisotropy of monolithic biochar, with axial hardness exceeding transverse hardness by up to 28.5× (hemlock, 1,000 °C), and achieving steel-like values in African ironwood (2.25 GPa). This structural hardness demonstrates a strong correlation with bulk density (R2 = 0.84), and carbon fraction (R2 = 0.71). Conversely, nano-indentation demonstrates a uniform intrinsic cell-wall hardness (3.64–4.41 GPa) that is independent of wood species or orientation. This scale-divergent behavior confirms that the dramatic mechanical anisotropy originates from the hierarchical pore architecture of the precursor wood, rather than from intrinsic differences in the carbon material itself. The findings presented in this study establish a quantitative framework for engineering monolithic biochar with tailored mechanical performance, ranging from ultra-hard species for robust electrodes to highly anisotropic types for directional-flow filters, thus paving the way for its application in next-generation structural, energy, and environmental technologies.

-

Key words:

- Monolithic wood biochar /

- Hardness /

- Intrinsic uniformity /

- Structural anisotropy /

- Temperature /

- Wood species