-

Numerous contaminants, including heavy metals, nutrients, and emerging pollutants, are inevitably released into the aquatic environment due to the fast development of industry, agricultural production, and human activities[1,2]. Most untreated or partially treated industrial and domestic wastewater is a major source of water pollution[3]. Water contamination by organic pollutants and heavy metals represents a ubiquitous global challenge. Heavy metals exhibit persistent non-biodegradability, widespread distribution, and pronounced toxicity. Heavy metal discharge occurs extensively worldwide, severely compromising aquatic ecosystems and water quality[4].

The impact of organic pollution in the aquatic environments cannot be overlooked[5,6]. Organic pollutants include both conventional and emerging contaminants[7]. Traditional organic compounds like dyes raise water turbidity, impede photosynthesis[8], and may degrade into toxic or carcinogenic substances[9]. Moreover, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) exhibit carcinogenicity toward the skin, lungs, and bladder epithelium[10]. Emerging pollutants include pharmaceutical residues[11], phenolic derivatives[12], and perfluorinated compounds[13], among others. Pharmaceuticals have the potential to promote antibiotic resistance genes, creating long-term risks to aquatic ecosystems[14,15]. Phenolic compounds are typically utilized in the preparation of petrochemicals, synthetic rubber, and plastics. They are highly toxic to humans and can seriously affect the nervous system[16]. Perfluorinated compounds demonstrate multiple toxicological effects, including immunosuppression, liver damage, and carcinogenic potential[17]. While individual removal of organic pollutants or heavy metals can be achieved effectively, their simultaneous presence in aquatic systems presents substantial remediation challenges requiring integrated treatment approaches.

For simultaneous treatment of organic pollutants and heavy metals in wastewater, several techniques have been reported, such as membrane filtration[18], ion exchange[19], electrochemical[20], biological[21], and advanced oxidation methods[22]. However, significant limitations constrain industrial implementation of these methods, including substantial operational expenses and complex integration of multiple technologies[23]. Adsorption remains the most promising remediation approach due to its operational simplicity, straightforward implementation, and effective regeneration potential[24]. At present, materials frequently utilized for the adsorption of organic pollutants include montmorillonite[25], zeolite[26], and graphene oxide[27]. The adsorption materials for heavy metals mainly include sepiolite[28], chitosan[29], biochar[30], and carbon nanotubes[31]. Carbonaceous materials, including carbon nanotubes, biochar, and activated carbon, facilitate the simultaneous removal of organic pollutants and heavy metals, though optimal adsorbents for these contaminant classes exhibit distinct physicochemical properties. Therefore, the development of materials with dual properties at the same time is essential for the simultaneous removal of combined pollution in wastewater.

Biochar is a stable, porous, carbon-rich material[32,33]. As a novel kind of adsorbent, it has been extensively employed to eliminate both organic and inorganic contaminants from water[34,35]. Typically, the physicochemical characteristics of biochar can be modified via modification[36], giving it excellent adsorption capacity[37,38]. For example, corn straw biochar treated with H3PO4 exhibited both higher pollutant adsorption capacity and higher tolerance to co-existing salts compared to untreated corn straw biochar. Bisphenol A and Cr6+ demonstrated maximum adsorption capabilities of 476.19 and 116.28 mg/g, respectively[39]. The tetracycline and Pb2+ adsorption on manganese-enriched merchant land biochar showed superior removal efficiencies over the pristine merchant land biochar, with 279.33 and 47.51 mg/g adsorption capacity for Pb2+ and tetracycline, respectively. This enhancement was primarily attributed to the formation of manganese oxide and manganese minerals through pyrolysis[40]. Therefore, an increasing number of engineered biochars are being employed for removing organic pollutants and heavy metals, such as nano-metal oxide biochar composites, magnetized biochar composites, and loaded biochar as photocatalysts, which have been developed and utilized[41].

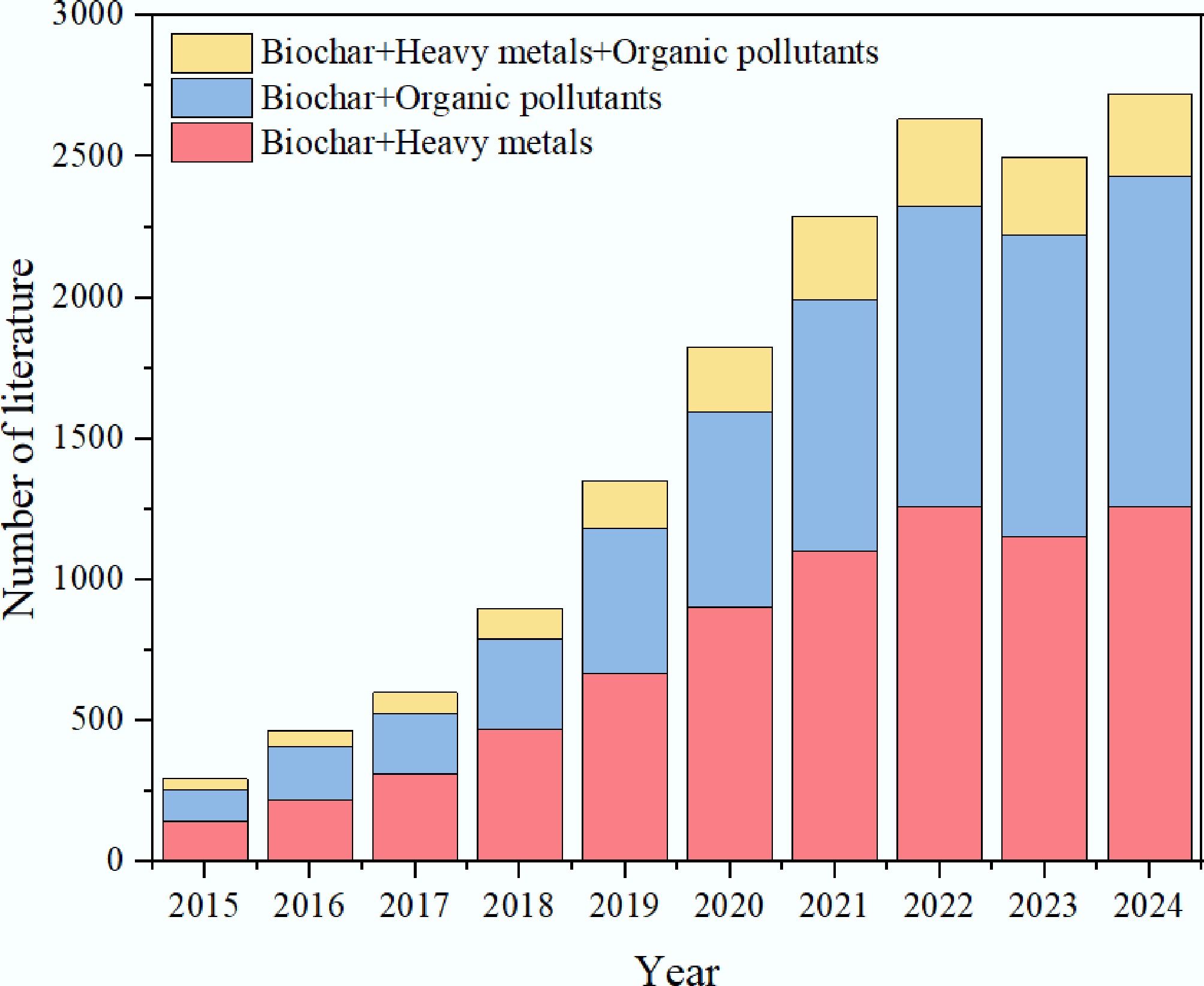

Although numerous biochar variants have been engineered for mixed contamination, their structural properties and remediation efficacies vary considerably. A Web of Science analysis using keywords 'biochar', 'organic pollutants', and 'heavy metals' reveals accelerating research interest in biochar-based simultaneous removal technologies (Fig. 1). Hu et al.[42] explored the use of biochar-based materials for removing organic and inorganic pollutants. Their work specifically examined these materials' roles in both adsorption and degradation processes. Akash et al.[43] published a review on the application of metal-oxide nano-biochar materials for removing dyes and heavy metals. Kasera et al.[44] discussed the adsorption mechanisms for the removal of heavy metals and organic compounds by nitrogen-doped biochar, including the mathematical analysis of adsorption. All of these studies have proved the promising advantages of biochar in certain aspects of environmental applications. Although some researchers have published reviews on the removal of organic pollutants and heavy metals, these studies mostly emphasize removal performance and mechanisms within isolated systems. Consequently, the existing research remains fragmented and insufficient to support further investigations. Therefore, a systematic summary of the simultaneous removal of organic pollutants and heavy metals by engineered biochar would help understand and grasp future research work in this field.

Figure 1.

The number of literature on the application of biochar in water from 2015 to 2024 (Data come from Web of Science).

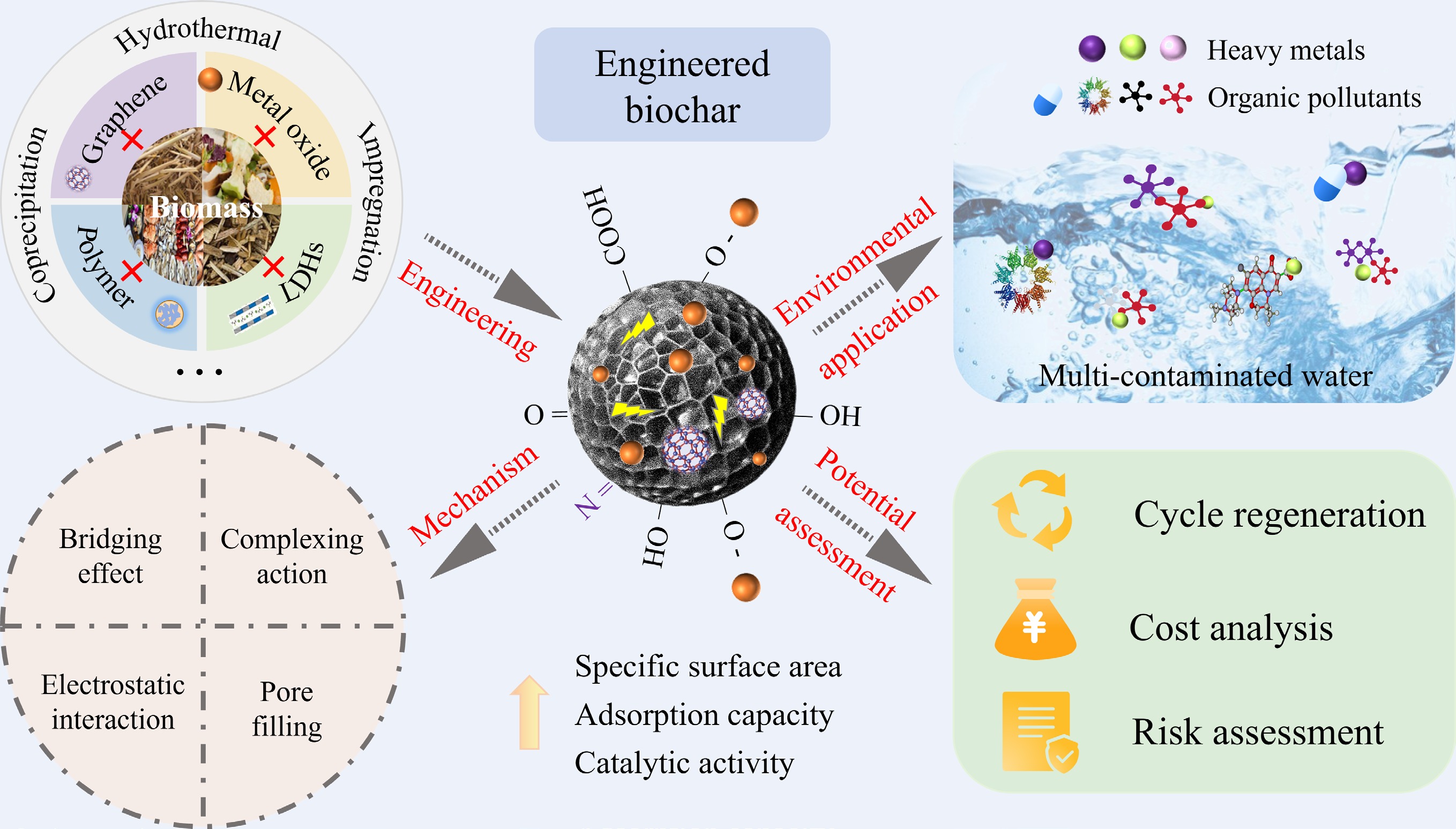

Based on these considerations, this review aims to: (1) examine prevalent engineered biochar for removing organic pollutants and heavy metals from wastewater; (2) elucidate simultaneous removal mechanisms for different categories of pollutants; (3) evaluate engineered biochar applications in the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and dyes, antibiotics and heavy metals, and other compounds; (4) assess practical implementation in real water systems, including regeneration techniques, economic feasibility, and environmental impacts; and (5) identify research gaps and future directions.

-

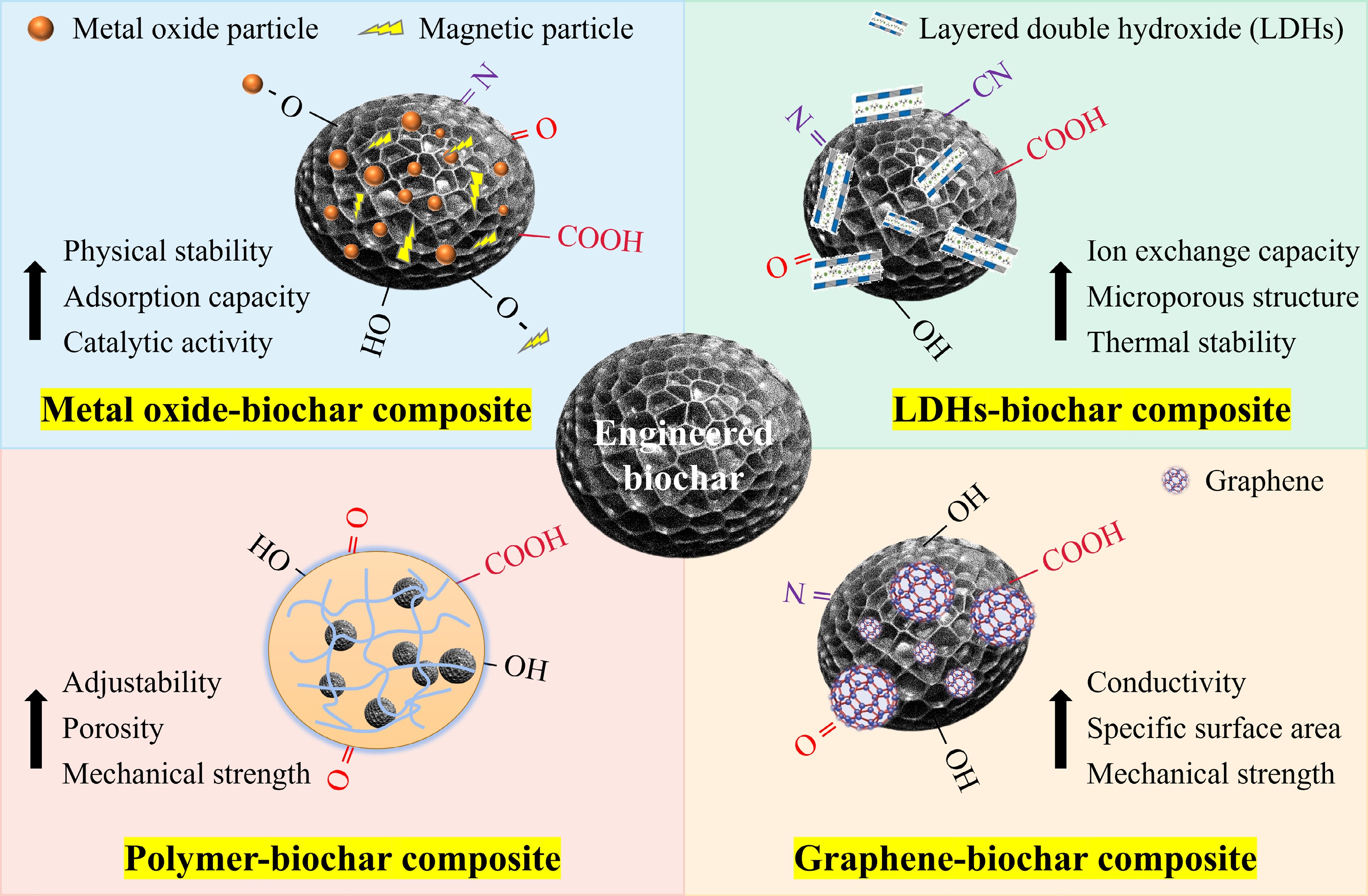

Transforming solid waste from agriculture, industry, and forestry into biochar to remediate polluted water is currently a practical task of turning waste into treasure. However, to achieve industrial application, functionalization of pristine biochar is required to enhance its adsorption efficiency, stability, and recyclability[45]. Based on the literature review, engineered biochar that is utilized to remove heavy metals and organic pollutants simultaneously can be grouped into several categories as illustrated in Fig. 2, including metal oxide-biochar composites, layered double hydroxide-biochar composites, polymer-biochar composites, and graphene-biochar composites.

Metal oxide-biochar composites

-

Metal oxide particles serve as the primary source of active sites that govern both adsorption capacity and catalytic turnover in biochar-based systems. Their intrinsic crystal phase, surface hydroxyl density, and redox potential ultimately determine the composite's adsorption capacity or catalytic ability toward heavy-metal ions and refractory organics[46]. However, most metal oxides are prone to agglomeration due to their nanoscale size, and incorporating them into biochar matrices can reduce particle aggregation while improving their stability[47]. Research reports demonstrate that functionalizing metal oxides with amino ligands enhance their functionality. Additionally, forming stable complexes with the -NH2 and -COOH of biochar improves the hydrophilicity, dispersibility, and surface adsorption capacity of metal oxides[48]. When selecting metal oxides for modifying pristine biochar, priority should be given to some non-toxic and environmentally friendly metal oxides, such as ZnO, Fe3O4, CeO2, and ZrO2[49−51]. Moreover, some metal oxide particles exhibit magnetic properties and can be separated easily via a magnetic field after contaminant adsorption, enhancing their effectiveness in recovery and reuse[52].

Common methods for preparing metal oxide-biochar composites include the sol-gel method, impregnation method, hydrothermal method, and co-precipitation method[53]. Among these, the impregnation method is predominant due to its precise control, cost-effectiveness, and operational simplicity[54]. This process facilitates the adsorption of metal ions onto the biochar through interaction with functional groups (e.g., -OH and -COOH) on the biochar surface. Subsequent heat treatment converts the adsorbed metal ions into metal oxides, which are then fixed onto the biochar[55,56]. However, excessive loading of metal oxides can block the pores of the biochar, compromising its removal performance. Table 1 presents the optimal conditions for various metal oxide-biochar composites.

Table 1. Performance and optimal conditions of engineered biochar for simultaneous removal of organic pollutants and heavy metals

Engineered biochars Pollutants Removal performance (mg/g) pH Dosage

(g)Initial concentrations (mg/L) Reaction

time (min)Reaction temperature (°C) Ref. Hydroxyapatite-modified cod bone biochar Diclofenac 43.29 8.0 0.01 100 300 − [172] Fluoxetine 12.53 100 Pb2+ 714.24 2,100 Silicon dioxide/biochar (corn cob) nanocomposite U6+ 255.10 5.0 0.6 10–100 − 25 [173] Cr6+ 90.01 2.0 0.2 MB 1,614.04 7.0 0.4 Potassium ferrate-activated wheat straw biochar Cu2+ 48.75 − 0.2 10 720 25 [127] SMZ 51.72 Magnesium oxide/rice husk biochar composite BPA 18.10 5.0 0.1 20–160 240 25 [174] Cu2+ 64.90 Mixed silicate/hydrocarbon (pine sawdust) composites Cu2+ 214.70 − 0.5 10–300 − − [175] Zn2+ 227.30 TC 361.70 Iron/nitrogen co-doped rapeseed straw biochar CIP 46.45 2.0−6.0 0.2 50 − 25 [176] Cu2+ 30.77 EDTA/chitosan bifunctionalized magnetic biochar MO 305.4 5.0 0.5 200 − 25–45 [116] Cd2+ 63.20 100 Zn2+ 50.80 100 Eagnetically-modified Enteromorpha prolifera−based biochar hydrogels MO 47.65% 3.0 0.01 80 − [177] Cr6+ 42.50% 80 Polymethyl methacrylate/(rice husk ash)/polypyrrole composite film Cr6+ 360.50 2.0 0.006 0−80 150 25 [178] Tartrazine (E102) 165.70 60 Polyacrylic acid modified tobacco stem biochar Quinclorac 80.74% − 0.008 10 240 25 [179] Pb2+ 73.20% Iron/zinc activated rice straw biochar 17β-estradiol 123.00 − 0.006 6 − 25 [180] Cu2+ 76.00 140 Nano zero valent iron loaded biochar Cr6+ 30.87 3.0 0.3 50 2,880 25 [181] TCE 32.32 10 Compared to pristine biochar, metal oxide-biochar composites exhibit superior adsorption capabilities for both organic pollutants and heavy metals. By adjusting the types and contents of metal oxides, as well as the preparation conditions of the biochar, the adsorption performance can be adjusted to suit the removal of various water pollutants[57]. However, the synthesis of metal oxide-biochar composites is often complex, which increases costs and limits their viability for large-scale implementation[58]. Preparation methods for these composites require optimization to enhance their adsorption capacity and cost-effectiveness, for example, by changing carbonization conditions and improving the loading method of metal oxides. In addition, different metal oxides exhibit different affinities for particular pollutants, necessitating careful selection based on specific contamination scenarios.

Layered double hydroxide-biochar composites

-

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) are a group of inorganic compounds that have a layered structure. Their chemical formula can be denoted as [M2+1-xM3+x(OH)2]x+[Ax/n·H2O]n−, in which, M2+ and M3+ represent the divalent and trivalent metals, x denotes the ratio of M3+/(M3+ + M2+), and An− stands for the organic or inorganic anions[59]. The interlayer anions in LDHs may be displaced by other heavy metal ions or other harmful ions via ion-exchange to achieve effective removal of pollutants, and thus are widely used as adsorbent materials[60]. By preparing composites with biomass waste containing oxygen functionalized groups, the dispersion of LDHs can be improved, the exposure of surface active sites can be increased, and the adsorption capacity of single-LDHs can be enhanced[61].

The preparation techniques of the hydrothermal method, the anion exchange method, the co-precipitation method, and in-situ synthesis are primarily applied to synthesize LDHs-biochar composites[62]. Co-precipitation is the preferred approach for preparing composites owing to its simplicity, economy, and high yield. The basic principle of the co-precipitation method is the reaction of divalent and trivalent metal ions with hydroxyl ions to produce LDH structures under alkaline conditions. Meanwhile, the incorporation of biochar provides a carrier that promotes the uniform deposition of LDHs on its surface[63,64]. Nevertheless, sometimes the inhomogeneity of the biochar surface may lead to non-uniform distribution of the LDH layer. Consequently, various LDH-biochar composites, and their optimal conditions for the elimination of organic pollutants and heavy metals, are given in Table 1.

LDHs-biochar composites exhibit selective adsorption ability due to the interlayer voids of LDHs and the porous structure of biochar, which can efficiently remove specific types of heavy metals and organic pollutants[65]. Factors such as loading ratio, dispersion, and surface modification of layered hydroxides and biochar all affect the properties of organic pollutants and heavy metals removal[66]. Therefore, future research should delve into these factors to optimize the composition and structure of LDH-biochar composites. Additionally, exploring regeneration and recovery methods for LDH-biochar composites is crucial for minimizing waste generation, and enhancing the sustainability of adsorption materials.

Polymer-biochar composites

-

Polymer-biochar composites generate synergistic effects by combining the structural integrity and chemical functionality of polymers with the porous structure and high adsorptive performance of biochar[67]. This combination not only strengthens the stability of the composite but also effectively eliminates organic contaminants and heavy metals through chemical and physical pathways. Consequently, these composites are increasingly gaining attention in water treatment and environmental purification[68]. Commonly used polymer materials include polyethylene, polyurethane, polyacrylamide, chitosan, and alginate[69−71]. Among them, chitosan is particularly favored for making polymer biochar composites due to its good water solubility, biocompatibility, and ease of integration with materials like biochar[72]. The incorporation of biochar with chitosan typically involves dispersing biochar powder in a chitosan solution, followed by solidification through freezing or heat treatment. This method embeds biochar within the chitosan polymer network, increasing the specific surface area of the composite and its adsorption sites[73]. However, chitosan has some limitations, such as high solubility in an acidic environment, and limited mechanical strength[74,75].

Polymer-biochar composites usually have good recyclability and can be reused multiple times through simple regeneration steps[71]. However, some polymers may lose stability under extreme environmental conditions, affecting their adsorption performance and reusability[76]. Therefore, appropriate modification measures can be taken, such as introducing active groups and cross-linking treatment, to increase adsorption sites and specific surface area, thereby improving adsorption performance. Alternatively, they can be incorporated with other materials, such as metal oxides and nano-materials, to enhance selectivity.

Graphene-biochar composites

-

In the last few years, graphene-based composites have been extensively employed in wastewater remediation owing to their outstanding chemical stability, electrical conductivity, and strong adsorption capacity[77]. However, the high production cost of graphene and the difficulties associated with its recycling and reuse limit its sustainability. Therefore, to develop more cost-effective composites, functionalization of graphene should be considered[78]. Studies indicate that graphene-biochar composites can reduce graphene stacking, enhancing the stability and dispersibility of the composites in water. Moreover, the incorporation of biochar can decrease the total cost of the composites and enhance their overall adsorption capacity[79,80]. Common methods used to prepare graphene-biochar composites include physical mixing, co-precipitation, chemical cross-linking, and solvothermal methods[81]. The primary mechanisms for heavy metals and organic pollutants removal by graphene-biochar composites include ion exchange, π–π interactions, electrostatic effects, and pore filling[82]. To understand the effectiveness of the composites in applications, a variety of graphene-biochar composites and polymer-biochar composites for organic pollutants and heavy metals removal are listed in Table 1.

Due to the high conductivity and excellent mass transfer properties of graphene, graphene-biochar composites exhibit a rapid adsorption rate, enabling efficient pollutant removal[83]. Nevertheless, the preparation cost of graphene-biochar composites is relatively high, which may limit their economic feasibility in large-scale applications[78]. In addition, the integration of graphene and biochar may pose stability challenges, especially under some extreme environmental conditions, which may lead to the detachment or aggregation of the loaded graphene and compromise adsorption performance.

-

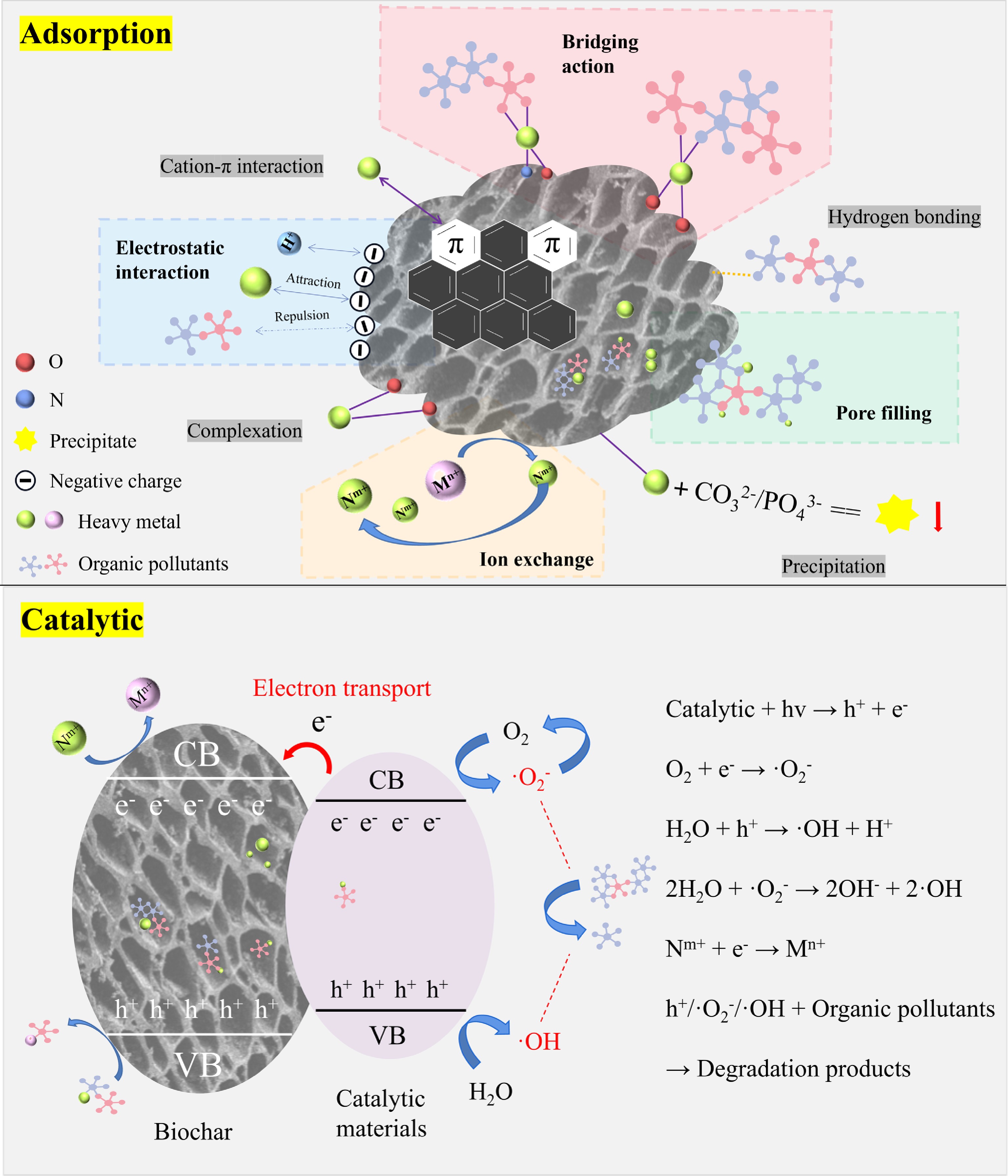

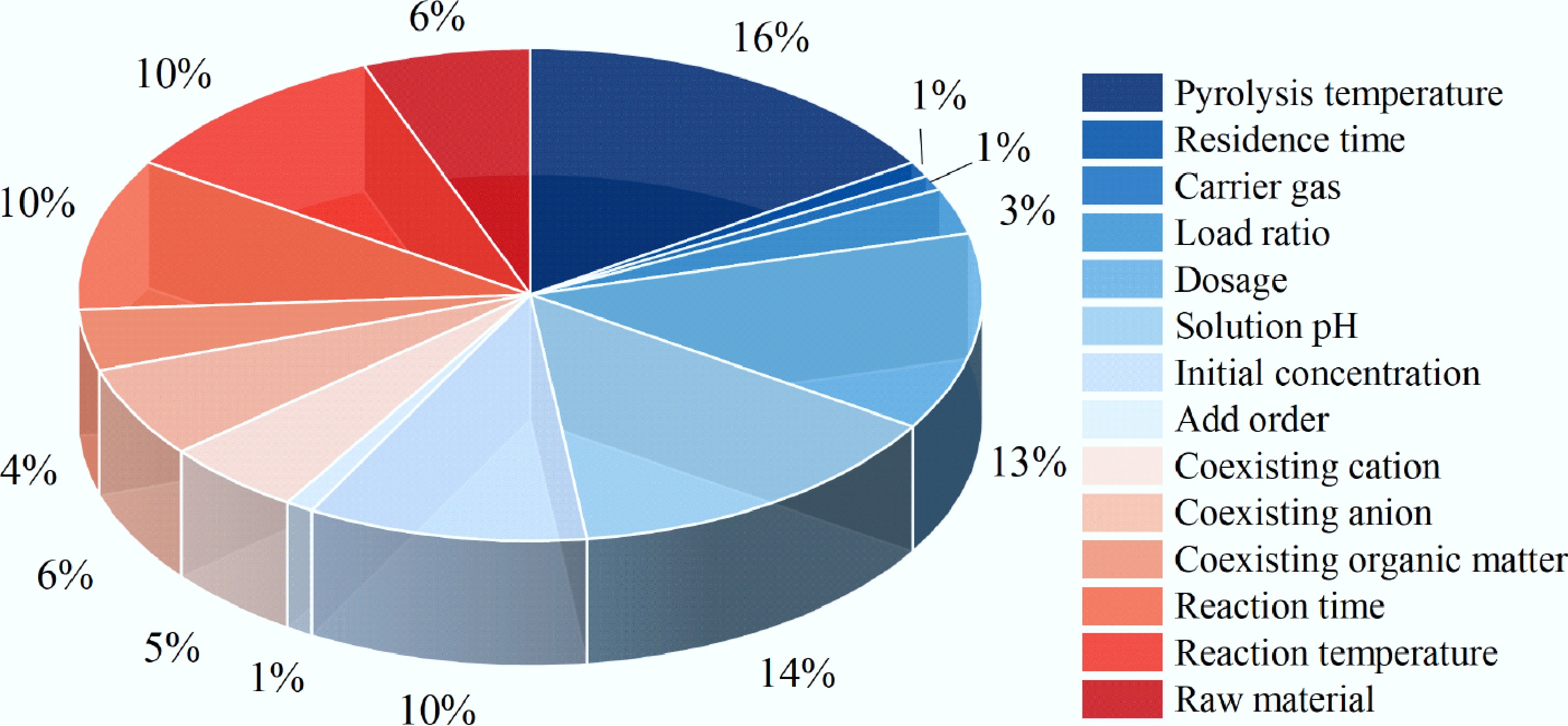

The main removal mechanisms of heavy metals and organic pollutants by engineered biochar are shown in Fig. 3. Electrostatic attraction is the predominant mechanism for heavy metal removal by engineered biochar. Comprehensive mechanistic analyses have additionally revealed multiple concurrent pathways contributing to adsorption phenomena, including cation-π interaction, complexation, surface precipitation, and ion exchange[84]. π-electron donor-acceptor (EDA) interactions, electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding, pore-filling, and hydrophobic interactions may occur in the sorption of organic pollutants[85,86]. The adsorption mechanisms of diverse types of organic pollutants and heavy metals in the environment are very different. These variations depend on factors such as the preparation conditions of engineered biochar, environmental pH, temperature, and pollutant concentration[87]. The impact weights are shown in Fig. 4. Complex interactions, such as enhancement, inhibition, and neutral effects, occur between organic pollutants and heavy metals[88]. Their combined removal mechanisms include bridging effect, competitive adsorption, electrostatic interaction, and pore filling.

Figure 3.

Multiple mechanisms of engineered biochar for co-removing heavy metals and organic pollutants.

Figure 4.

The proportion of influencing factors on the removal performance of engineered biochar in co-removing heavy metals and organic pollutants.

Bridging effect

-

The bridging effect is the primary mechanism facilitating the simultaneous adsorption of heavy metals and organic pollutants[89]. Metal ions or organic ligands that are adsorbed on the engineered biochar surface act as bridges to form ternary complexes with heavy metals and organic pollutants. The formation of these complexes enhances the affinity of organic pollutants and heavy metals for the engineered biochar[40,90]. Additionally, other organic pollutants can also directly bind with heavy metals to form complexes. In this scenario, both organic pollutants and heavy metals can act as bridges for each other, improving adsorption capacity[91]. Through the bridging effect, more effective adsorption sites are created on the engineered biochar surface, aiding in the simultaneous removal of more heavy metals and organic pollutants.

It is worth mentioning that the bridging effect involves two distinct modes of complexation: inner-bound complexation, and outer-bound complexation[92]. Inner-bound complexation mainly combines the central ion with the ligand through coordination bonds[93], while outer-bound complexation connects metal acid ions to the carbon-based substrate surface via electrostatic interaction[94]. For instance, Yea et al.[95] investigated the impact of heavy metals on the removal of perfluorinated compounds by polyaniline-activated biochar. The results showed that heavy metals can act as bridging ions to form inner adsorbent–heavy metal surface complexes, which improved the removal performance of perfluorinated compounds.

Competitive adsorption

-

Competitive adsorption of organic pollutants and heavy metals primarily involves competition for the limited active sites on engineered biochar[96]. On the one hand, heavy metals and organic pollutants can attach to engineered biochar surfaces through different mechanisms, such as interactions with amino or carboxyl groups[97]. For example, tetracycline adsorbs to hydroxyl groups of the charcoal via hydrogen bonding, while Cu2+ also adsorbs to the same groups through complexation, resulting in lower adsorption capacity in a binary system, in contrast to a single system[98]. On the other hand, different organic pollutants and heavy metals possess distinct chemical properties, such as charge and polarity. These characteristics affect their affinity for specific functional groups on biochar[99]. For instance, positively charged heavy metals (such as Pb2+ and Cu2+) may be attracted to negatively charged groups like carboxyl or phenolic hydroxyl, while nonpolar organic pollutants (such as benzene) might interact with the carbon-based groups of biochar through hydrophobic interactions[100−102].

Furthermore, when active sites on the engineered biochar are filled with either organic pollutants or heavy metals, the adsorption of other contaminants is limited. For instance, if the heavy metal ions are in high concentration, they may adsorb preferentially by ion exchange, thus suppressing the adsorption of organic pollutants[84,103].

Electrostatic interaction

-

Electrostatic interaction is also an underlying mechanism. The surface charge of engineered biochar is determined by the ionization state of the functional groups on its surface, which is governed by pH[104]. The charge properties of the biochar surface change under varying pH conditions. For instance, -COOH may become protonated to -COOH2+, causing the surface of the biochar to be positively charged at low pH[86]. Conversely, -COOH may lose protons to become -COO−, making the surface charge negative at high pH[105]. These variations directly influence the engineered biochar adsorption of charged heavy metals and organic pollutants. Studies have shown that when engineered biochar surfaces and metal ions carry opposite charges, electrostatic attraction could improve the adsorption of metal ions. Meanwhile, if negatively charged organic pollutants are present in the solution, the appropriate electrostatic repulsion might reduce the adsorptive properties of the engineered biochar towards these organic pollutants. The presence of metal ions can facilitate organic pollutants removal by decreasing electrostatic repulsion between engineered biochar and organic pollutants[106]. Additionally, the ionic strength of the solution affects electrostatic interactions. High ionic strength generally compresses the bilayer, reducing the effective charge density on the surface of engineered biochar, thereby diminishing electrostatic attraction[107]. This means that in high-salt environments, even though metal ions or organic pollutants are electrostatically attracted to the engineered biochar surface, the adsorption efficiency may still be reduced.

Pore filling

-

Besides the above-mentioned mechanisms, pore filling in engineered biochar is also a significant mechanism for controlling organic pollutants and heavy metals migration[108]. Choudhary et al.[109] utilized NaOH-modified cactus biochar for removing malachite green, Cu2+, and Ni2+, with adsorption amounts of 1,341, 49, and 44 mg/g. Adsorption kinetics analyses revealed dual interaction mechanisms between NaOH-modified cactus biochar and multiple contaminants (malachite green, Cu2+, Ni2+): robust chemisorption processes coupled with predominant intraparticle diffusion into microporous networks. In complementary research, Zhao et al.[39] demonstrated phosphoric acid-modified corn stover biochar exhibiting exceptional removal efficiency toward both endocrine-disrupting bisphenol A and Cr6+. The study found that phosphoric acid-modified corn stover biochar had extremely high porosity, and micropore filling was the fundamental mechanism. Cr6+ and bisphenol A were removed by up to 70% and 90%. Zhou et al.[98] reported that the highest adsorption capacities of Cu2+ and tetracycline on iron/zinc-modified sawdust biochar were 108 and 95 mg/g at a pH of 6.0, and suggested that the pore structure of iron/zinc-modified sawdust biochar was one of the primary mechanisms influencing the high tetracycline and Cu2+ adsorption.

Overall, the mechanisms for the simultaneous removal of organic pollutants and heavy metals mainly include the bridging effect, competitive adsorption, electrostatic interaction, and pore filling. However, in practical applications, environmental factors are complex and varied. To better explain the adsorption mechanism of heavy metals and organic pollutants in coexistence systems, the following methods can be further explored in the future: (1) optimize experimental design, such as setting up preloaded pollutants to observe the effect; (2) establish a model and quantify the contribution ratios of internal and external bond complexation in bridging effect using in-situ characterization techniques; and (3) use molecular dynamics simulation combined with in-situ characterization techniques to map the spatial distribution and affinity of functional groups on the surface of engineered biochar, and reveal the competitive priority. In addition, future research should break through the perspective of a single mechanism, focus on the analysis of multi-mechanism coupling effects, and promote the transformation of engineered biochar from laboratory mechanism research to large-scale applications in actual wastewater treatment.

-

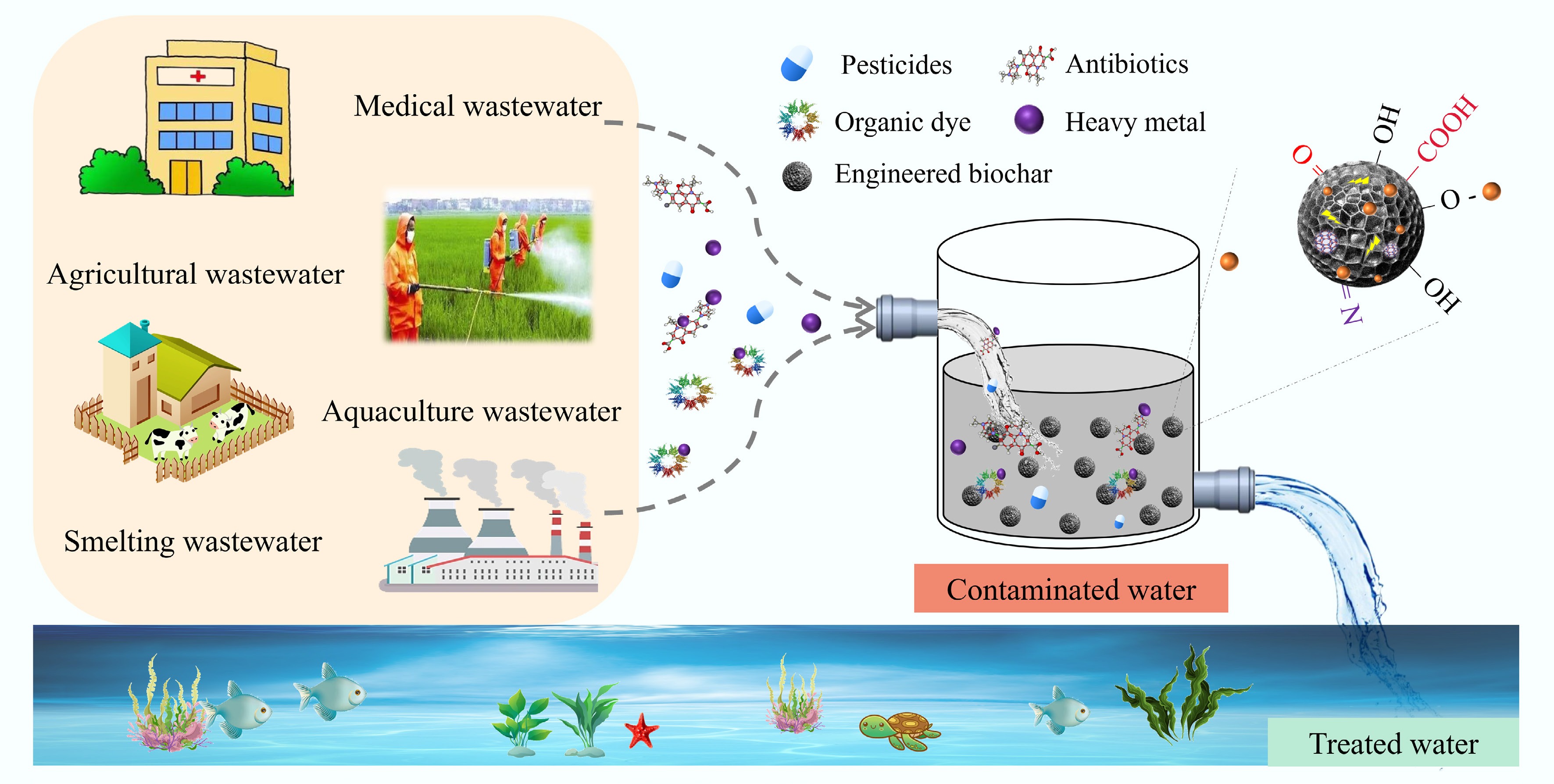

The interactions between organic pollutants and heavy metals tend to alter their physicochemical properties, migration and transformation pathways, as well as biotoxicity[70]. This makes the treatment of combined pollution more difficult and poses a greater threat to the environment than mono-contamination[110]. Compared with other adsorption materials, high adsorption performance and environmental friendliness are two benefits of engineered biochar. Applications of engineered biochar have been made to remove many contaminants, including heavy metals, nutrients, emerging pollutants, and organic dyes. Therefore, the use of engineered biochar in environmental remediation is covered in depth in this section (as shown in Fig. 5).

Organic dyes and heavy metals

-

The printing and dyeing industries have grown rapidly in the past few years, leading to an increasingly complicated problem of water contamination from heavy metals and organic dyes[111]. Heavy metals are typically applied as effective mordants in the dyeing process, and therefore inevitably enter water with the continuous discharge of dyeing wastewater, causing stronger and more complex ecotoxicity to aquatic ecosystems[112]. Moreover, the differences in physicochemical properties between organic dyes and heavy metals, make it more challenging to treat them simultaneously[113]. Consequently, before releasing industrial effluent into the receiving water, it is vital to minimize the amount of heavy metals and organic dyes[114].

Currently, a recommended technology for simultaneously removing two types of contaminants is to add more targeted sites to a highly effective adsorbent for a single pollutant[115]. Engineered biochar has successfully demonstrated this remediation approach in practical applications. In a notable implementation, Zhang et al.[116] synthesized magnetic bamboo biochar with dual-chelating agents, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) and chitosan (ECMBB), which achieved simultaneous removal of Cd2+, Zn2+, and methyl orange (MO). Research showed that at 25 °C, the adsorption capacities of ECMBB for MO, Cd2+, and Zn2+ were 305.4, 63.2, and 50.8 mg/g, respectively. Under identical conditions, the ECMBB adsorption capacity was 1.9, 6.1, and 5.4 times that of magnetic bamboo biochar. ECMBB effectively sequestered anionic MO through three concurrent mechanisms: π–π interactions, electrostatic forces, and hydrogen-bond formation. This engineered biochar also enhanced carboxylate functionality within metal-complexed chitosan-EDTA matrices through the strategic incorporation of amino functionalities. Notably, in the MO–metal binary system, the existence of MO remarkably enhanced the removal of Cd2+ and Zn2+, while co-existing heavy metals had no evident impact on the MO adsorption. However, the opposite conclusion was obtained in another study. Yu et al.[117] used KOH to activate banana peel biochar for co-removing methylene blue (MB) and Co2+. The reported maximal adsorption capacities were 1,303.50 mg/g for MB and 122.39 mg/g for Co2+ in a single system. Their study revealed that in the binary system, the existence of MB did not affect the adsorption efficiency of Co2+, but as the concentration of Co2+ solution increased, the negative impact on MB adsorption became more pronounced.

The above studies indicate that the interaction between heavy metals and organic dyes vary and may change due to factors such as biochar materials, preparation conditions, and initial concentrations. In particular, the chemical species of organic compounds and heavy metals in water play a critical role in their removal by biochars. Therefore, the adsorption mechanism among them is worth further investigation.

Antibiotics and heavy metals

-

Antibiotics (including fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines) are extensively used for their ability to prevent and treat diseases. However, due to the low absorption rate of antibiotics, only a tiny portion of them are absorbed by the body after being ingested into human or livestock bodies. In addition, over 85% of antibiotics enter the ecological environment in the form of their parent compounds with excreta as a medium of transmission[116]. Furthermore, antibiotics are characterized by multiple functional groups, such as -NH2 and -COOH for gentamicin, -OH and phenol-OH for amoxicillin, as well as C=O and -COOH for ciprofloxacin[118,119]. Such functionalized groups allow antibiotics to combine with other chemicals, particularly with heavy metals, to form heavy metal-antibiotic complexes[120]. The generation of heavy metal-antibiotic complexes may alter the chemical reactivity, physicochemical characteristics, and morphology of pollutants. They may even exert a considerable influence on their ecotoxicological effects and environmental behavior[116]. Consequently, the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and antibiotics is attracting growing research interest.

Research has reported various adsorption materials for removing heavy metals and antibiotics, reducing environmental risks. For instance, Zhou et al.[121] prepared the ZIF-8 metal organic framework which could remove 95.4% of Cu2+ and 80.3% of norfloxacin. Li et al.[122] synthesized a nano Fe0/FeSx composite loaded on blast furnace slag for in-situ remediation of groundwater contaminated with Cr6+ and oxytetracycline, and the adsorption capacities reached 38 and 95 mg/g. Azad et al.[123] introduced a novel crosslinked/amine functionalized poly (ethylene glycol butyraldehyde)-polyacrylonitrile adsorption nanocomposite membrane with retention rates of 97.46% and 83.28% for cefotaxime and Pb2+ within 90 min. Although the composites reported above have good removal efficiency for antibiotics and heavy metals, their complex synthesis conditions and high cost limit their industrial application[124].

Biochar, with its advantages of simple preparation, wide sources, and good stability, has gained increasing research attention, and has achieved good results in removing antibiotics and heavy metals[125]. For instance, Cao et al.[126] prepared bentonite-activated sludge biochar using a one-step pyrolysis process for co-removing norfloxacin (NOR) and Cu2+. The results suggested that when the mixing ratio of bentonite and sludge was 1:2, the maximum adsorption capacities for NOR and Cu2+ reached 89.36 and 104.10 mg/g, respectively. Interestingly, the existence of Cu2+ suppressed the NOR adsorption on bentonite-activated sludge biochar and sludge biochar, and the inhibitory effect progressively enhanced as the proportion of sludge grew. Meanwhile, the addition of NOR also reduced the adsorption efficiency of Cu2+. This might be because ion competition lowers the adsorption efficiency of Cu2+ and NOR in the combined system. Zhao et al.[89] also reported similar findings. However, Yan et al.[127] obtained the opposite conclusion. The research team used wheat straw and ferrate (K2FeO4) as precursors to prepare iron-modified biochar (Fe-BC) for sulfadiazine (SDZ) and Cu2+ adsorption. The adsorption capacity of Fe-BC for SDZ and Cu2+ in a binary system was higher than that in a single system, which might be owing to the complexation and mutual bridging effect between SDZ and Cu2+. Additionally, the loaded iron oxide particles could act as a physical barrier, preventing the Cu2+ and SDZ from segregating and thereby suppressing competitive adsorption.

In summary, different modification methods and pollutants can lead to different interactions, thereby promoting or inhibiting their removal efficiency. Therefore, in response to the integrated contamination of heavy metals and antibiotics, it is essential to conduct systematic research on specific pollution scenarios, rather than simply applying generalized strategies.

Other organic pollutants and heavy metals

-

Except for the organic pollutants listed above, the environment usually contains multiple other components, such as PAHs, phenolic compounds, microplastics (NPs), and perfluorinated compounds (PFCs). Among them, PAHs are also widespread organic pollutants in the water environment, which are the earliest discovered and studied chemical carcinogens. When wastewater contains both industrial and domestic waste as well as rainwater containing road sediments, the simultaneous presence of heavy metals and PAHs in wastewater are universal[128]. Both of them can have detrimental impacts on the aquatic environment and can even be accumulated in the human body via the food chain because of their high toxicity and persistence. Given the importance of simultaneously removing these two types of pollutants, this topic has attracted increasing research in recent years. Lu et al.[129] investigated whether Cu2+ and Cr6+ inhibit the acenaphthene removal efficiency in co-existing systems utilizing bamboo and rice bran biochar. They found that co-existing Cu2+ and Cr6+ both suppressed the surface adsorption of acenaphthene by biochar. This was attributed to the fact that Cu2+ bound directly to the oxygenated functionalized groups of biochar. Meanwhile, Cr6+ was reduced to Cr3+, which subsequently bound to the oxygen-containing functionalized groups. Chen et al.[130] reported a similar phenomenon.

Furthermore, studies have reported that Cr3+ typically coexists with bisphenol A (BPA) in polluted surface and groundwater[131]. BPA, as a typical compound of endocrine disruptors, is widely used as a plasticizer. It can cause reproductive damage to humans and animals even at low concentrations. Engineered biochar also exhibits efficient simultaneous removal performance. For instance, Zhao et al.[39] utilized H3PO4 to activate corn straw biochar for the simultaneous removal of Cr3+ and BPA. The findings indicated that although the presence of BPA decreased the Cr6+ removal efficiency, it decreased by up to 10%. No sustained decrease was observed with the enhancement of BPA concentration. The existence of Cr6+ improved the BPA removal efficiency, which might be caused by hydrogen bonding interaction promoted by the bridging of oxygen-containing groups from CrO42– between BPA and biochar.

Meanwhile, NPs have become a globally recognized emerging environmental issue. There are research reports that NPs are released exponentially, seriously affecting water resource quality[132]. In addition to containing a variety of copolymers, polymers, and chemicals, NPs can act as carriers of heavy metals in the water environment and may pose a hazard to human health and aquatic organisms. Gao et al.[133] examined the adsorption characteristics of NPs on heavy metals by indoor and field experiments. The findings demonstrated that Cd, Cu, and Pb might all be adsorbed by polyvinyl chloride, polypropylene, polyethylene, polyamide, and polyoxymethylene. A complementary 6-month on-site experiment revealed significant accumulation of Cr, Pb, Cd, Cu, and Mn specifically on polyvinyl chloride and polypropylene substrates.

Ganie et al.[134] synthesized nano zero-valent iron-modified sugarcane bagasse biochar (nZVI-SBC) to explore how to effectively remove NPs and heavy metals. This engineered biochar demonstrated effective remediation capacity for diverse contaminants, including NPs and heavy metals (e.g., Cd2+, Ni2+, CrO42–, and AsO43–), with varying physicochemical properties and dimensional characteristics. It was observed that the maximum adsorption capacity of nZVI-SBC on 500 nm NPs modified with carboxylate was 90.3 mg/g, and Cd2+, Ni2+, CrO42–, and AsO43– exhibited the adsorption capacities of 44.0, 40.3, 87.8, and 47.6 mg/g. The removal mechanism of nZVI-SBC on NPs was electrostatic attraction, pore filling, and complexation, while surface complexation and co-precipitation were possible mechanisms for removing heavy metals. Currently, there is very little research on the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and NPs, and their adsorption performance and mechanism still need to be discussed. Expanding the applicability of engineered biochar to practical environments also requires a large amount of research evidence to support it.

In addition, PFCs are extensively utilized in a variety of applications, including lubricants, cleaning agents, flame retardants, and surfactants, due to their unique oleophobicity and hydrophobicity[135], especially in the electroplating process. Therefore, high concentrations of PFCs mixed with heavy metals are often found in the wastewater discharged from electroplating plants[136]. Yea et al.[95] used polyaniline-activated biochar (AB@PANI) to remove perfluorooctanoic acid, perfluorooctane sulfonate, and perfluorohexane sulfonate, and studied the effect of coexisting cations (Pb2+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+) on their removal performance. The results indicated that these heavy metal ions could act as bridging ions to form complexes from the surface of heavy metal ion contaminants of the inner sphere adsorbent and exchange ions with AB@PANI, thus improving the removal efficiency of PFCs. However, this study only considers heavy metal ions as an influencing factor to study the removal performance of PFCs. Although it has some reference value, it cannot fully reveal the mechanism and application potential of engineered biochar for simultaneously removing PFCs and heavy metals.

Numerous factors can affect the adsorption of organic pollutants and heavy metals by engineered biochar. The adsorption performance of engineered biochar can be impacted by changes in its hydrophobicity, surface area, and pore structure, which can be brought about by varying pyrolysis temperatures and raw feedstock types. Furthermore, contaminants and environmental conditions, such as reaction temperature and pH, evidently affect the adsorption performances of engineered biochar. Therefore, it is essential to fully understand the impact of co-existing organic pollutants and heavy metals on the adsorption performance of engineered biochar.

-

The effective regeneration and recycling of engineered biochar play a decisive role in enhancing the economic viability of wastewater treatment[137]. Table 2 shows the regeneration performance of different biochars. To recover pollutant-laden biochar for reuse, several different types of reagents have been studied to elute heavy metals and organic pollutants from adsorbed engineered biochar. Dyes (Congo red, methylene blue, and malachite green) can be desorbed using non-ionic or cationic surfactants, alcohols, or HCl[138,139]. Sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and other antibiotics can be desorbed by methanol/ethanol, NaOH, HCl, non-ionic or anionic surfactants, and complex solvents consisting of several of these reagents[140−142]. The principle of NaOH desorption is that at high pH, anions undergo desorption. Due to the deprotonation of engineered biochar, excessive negative charges repel anions, leading to their desorption. Moreover, HCl, citric acid, NaOH, and ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid can desorb heavy metals, e.g., Cr, Cu, and Pb[143−145]. The principle of HCl desorption is that at low pH, the surface protons and excess positive charges of engineered biochar repel cations, causing them to desorb from the surface[146].

Table 2. Regeneration performance of engineered biochar

Engineered biochars Pollutants Regeneration methods Regeneration performance Cycle

numberRef. NaOH-modified cactus biochar Peacock stone green 0.1 M NaOH The removal rate of peacock stone green decreased by 15%, and the removal rates of Cu2+ and Ni2+ both decreased by 16%. 6 [109] Cu2+ Ni2+ Iron/Zinc modified wood chip biochar TC 0.1 M NaOH The removal rates of TC and Cu2+ both exceed 89%. 3 [98] Cu2+ Polyacrylic acid-modified tobacco stem biochar Quinclorac − The removal rate of quinclorac was 53.8%, and the removal rate of Pb2+ was 45.5%. 5 [179] Pb2+ Hydroxyapatite-modified cod bone biochar Diclofenac Deionized water The adsorption capacity of diclofenac decreased by 11%−13%, the adsorption capacity of fluoxetine decreased by 15%−16%, and the adsorption capacity of Pb2+ decreased by 1.99%. 1 [172] Fluoxetine Pb2+ EDTA/Chitosan bifunctionalized magnetic biochar MO 1 M NaOH The removal rate of MO decreased by 16.8%, the removal rate of Cd2+ decreased by 1.5%, and the removal rate of Zn2+ decreased by 8.9%. 8 [116] Cd2+ 0.01 M EDTA-2Na Zn2+ Potassium ferrate-activated wheat straw biochar Cu2+ 0.01 M NaOH − 3 [127] SMZ Ball-milled magnetic nano biochar TC 0.2 M NaOH The adsorption capacities of TC and Hg2+ were approximately 90.55 and 87.36 mg/g. 5 [182] Hg2+ 0.5 M Na2S Iron/zinc-activated rice straw biochar 17β-estradiol Ethanol The removal rate of 17β-estradiol and Cu2+ decreased by 13.79% and 12.16%. 5 [180] Cu2+ Deionized water Iron/nitrogen co-doped rapeseed straw biochar CIP − The adsorption capacities of CIP and Cu2+ were approximately 3.67 and 3.89 mg/g. 5 [176] Cu2+ In binary systems, the co-existence of organic pollutants and heavy metals can affect the regeneration efficiency of engineered biochar[147]. Given the disparate regeneration performances of organic pollutants and heavy metals, sequential recovery may represent a more advantageous strategy[148]. Although a range of studies have reported the regeneration of engineered biochar following simultaneous adsorption, these methods demonstrate intrinsic limitations. For instance, improper handling during solvent recovery may introduce new contaminants and residues, and frequent chemical regeneration can decrease the physicochemical characteristics of the biochar[116]. Nevertheless, there is an emergent need to further research and develop a straightforward and useful method for regenerating biochar that also addresses the removal of mixed pollutants.

Economic cost analysis

-

Economic cost analysis is the most crucial step in any applied research, including pollutant remediation[149]. If the economic cost and energy demand are high, physical and chemical technologies used to remove pollutants may not be feasible[150]. Engineered biochar is increasingly used in environmental remediation owing to its low energy consumption, high adsorption efficiency, low cost, and ease of use in soil remediation and wastewater treatment[151]. Production of biochar is estimated to be cheaper in comparison to commercially activated carbon, costing USD

${\$} $ ${\$} $ Currently, there is little research on the cost analysis of engineered biochar that can simultaneously remove heavy metals and organic pollutants. However, some researchers have reported that the cost of pristine rapeseed straw biochar was USD

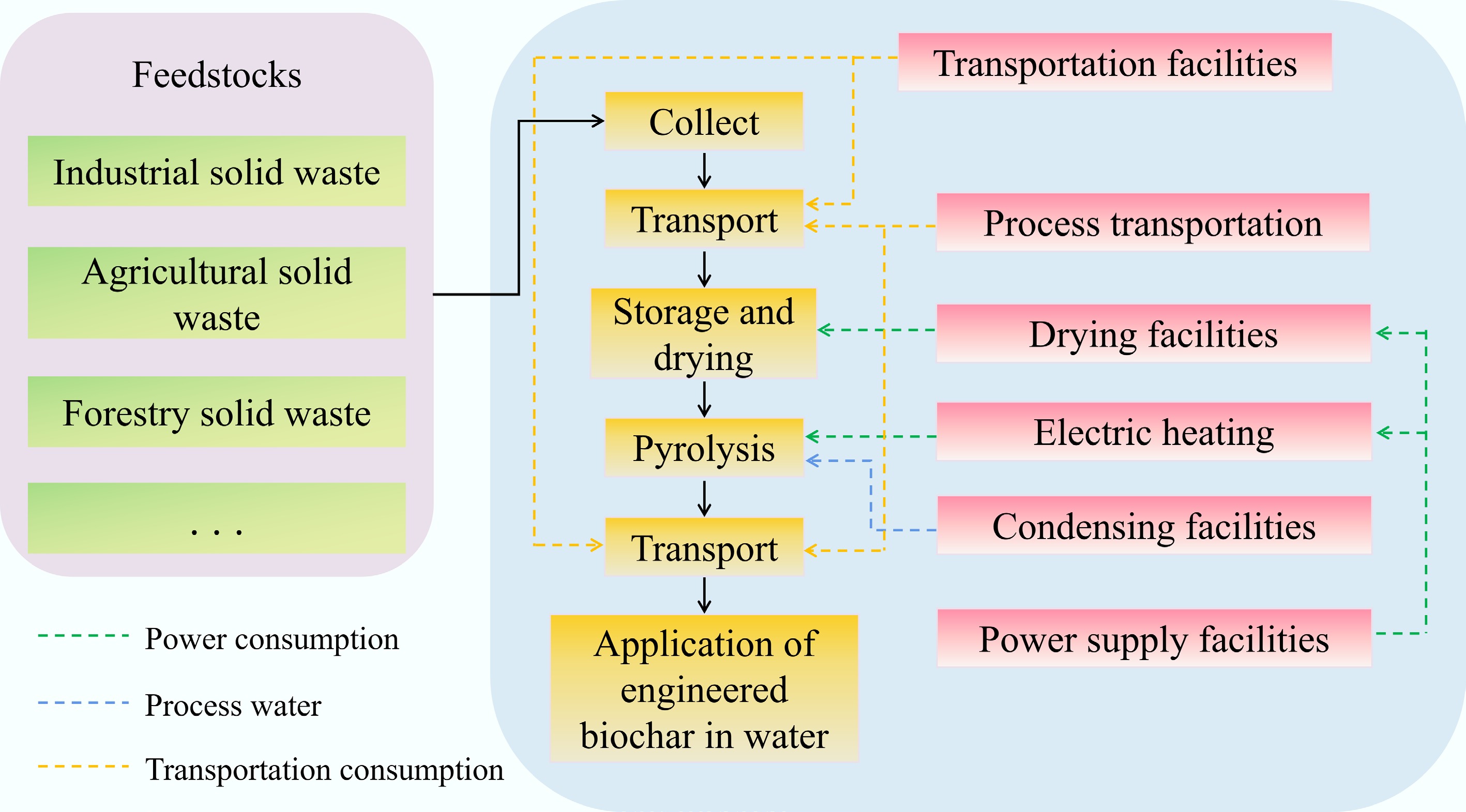

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ The economic cost analysis of engineered biochar should not be limited to production cost, application cost, and economic benefit analysis[155]. The production cost first involves the preparation of engineered biochar, including biomass collection, investment in pyrolysis equipment, and operating costs. Furthermore, the cost of the functionalization stage includes functionalizing agents, equipment, and energy consumption[156,157]. The application cost primarily involves the deployment, monitoring, and maintenance of engineered biochar. Firstly, it is necessary to consider the equipment, manpower, and transportation costs for deployment and application. Secondly, to ensure the sustained effectiveness of engineered biochar, monitoring and maintenance are also necessary, which will incur certain economic expenses[158,159]. The application of engineered biochar in aquatic environments may bring various economic benefits[131]. Initially, it can adsorb harmful pollutants, improving water quality while minimizing the cost of water environment remediation. Additionally, through improved water parameters, engineered biochar may catalyze aquaculture sector expansion and revenue enhancement[160]. Economic viability assessment requires a systematic evaluation of production costs, implementation requirements, operational expenditures, and projected financial returns throughout the complete lifecycle of these engineered carbon-based remediation technologies.

Environmental risk assessment

-

Engineered biochar can efficiently remove heavy metals and organic pollutants via mechanisms including chemical bonding and physical adsorption. However, its adsorption–release dynamics remain a concern[161]. On the one hand, engineered biochar can effectively reduce the pollution load in the environment by adsorbing pollutants. On the other hand, due to the saturation of its adsorption saturation sites of engineered biochar, excessive adsorption may result in the release of contaminants, leading to potential secondary pollution of the environment[162,163]. Moreover, engineered biochar loaded with pollutants may have toxic effects on exposed animals, plants, crops, microorganisms, and even humans in the environment[164,165]. In addition, previous studies have reported that engineered biochar, depending on different feedstocks, probably contains persistent free radicals and PAHs, which may also have potential adverse effects on the aquatic environment[166].

The underlying environmental risks of engineered biochar require a comprehensive understanding and evaluation to provide reliable scientific support for environmental governance[167]. Life cycle assessment (LCA) is a broadly applied tool for evaluating the environmental impacts of all the outputs and inputs of a product (or process) over its entire life cycle[168]. In the assessment, inputs and outputs of each stage are quantified and summarized, and the environmental effects generated by these inputs and outputs are analyzed and evaluated. Reasonable summaries and explanations of the relevant analysis results will be made[169].

At present, most studies focus on assessing the economic costs and environmental implications of the preparation of biochar[170]. The system boundary is shown in Fig. 6. It defines the range from the completion of the collection of different kinds of feedstocks to the end of the application of biochar in the water environment. It contains several steps such as collection, transportation, storage, drying, and the pyrolysis process. For example, Norberto et al.[153] aimed to investigate the environmental impact of modified rapeseed straw biochar for adsorbing As. The system boundary considered subsystems such as the collection, transportation, treatment, and preparation of rapeseed straw biochar, but did not include the disposal of adsorbents after use. The results indicated that modified rapeseed straw biochar offers higher environmental efficiency.

However, LCA also faces challenges in evaluating the environmental and social impacts of different stages of the lifecycle of engineered biochar, as the relevant environmental indicators (such as climate change and ecotoxicity) are numerous. Whether from the perspective of their impact or from a scientific perspective, these indicators are not equal[171]. There is not yet a consensus on which indicator has a more significant impact. Therefore, to better evaluate the lifecycle impact of engineered biochar, it is advisable to adopt a multidimensional evaluation method that comprehensively considers the weight and degree of influence of various environmental indicators, along with the influence of different social factors. This allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the true social and environmental impacts of engineered biochar, and provides a more reliable basis for formulating more reasonable policies and decisions.

-

The adsorption technology of engineered biochar offers a sustainable and environmentally friendly solution for treating contaminated water. Adsorbent materials based on solid wastes derived from industry, agriculture, and forestry have abundant functionalized groups, making them promising adsorbents for pollutant removal in either their pristine or functionalized forms. This paper reviews the categorization of engineered biochar and its applications in the synergistic removal of organic pollutants and heavy metals. Compared with other adsorbents, engineered biochar is renewable, biodegradable, biocompatible, and economically viable. Green, environmentally friendly, and low-cost biochar modification methods will become an inevitable trend for the co-removal of heavy metals and organic pollutants in water in the future. Moreover, various factors influence the interactions between organic contaminants and heavy metals, which are worth further exploration. Advancements in research on engineered biochar will undoubtedly lead to the emergence of new issues and challenges. Therefore, the following considerations should be pursued in future research:

(1) Explore more potential biomass feedstocks and functionalization materials. At present, the solid waste extensively applied in the preparation of biochar primarily include straw, animal manure/remains, fruit peel, sludge, etc, and further types of biomass feedstocks could be explored in the future. Moreover, while deciding whether to functionalize biochar, it is essential to take into account the cost, effectiveness, and stability of the modified materials. Industrial solid wastes like phosphogypsum and electrolytic manganese slag may be taken into consideration due to their large-scale accumulation and content of metallic elements.

(2) Research on the collaborative removal mechanisms of heavy metals and organic pollutants needs to be further strengthened. The research scope can be expanded to include the interaction between emerging organic pollutants and multivalent heavy metals. The microscopic interface adsorption process can be systematically analyzed using modern advanced characterization techniques and multidisciplinary research methods. Specifically, combined with a machine learning algorithm, a prediction model for competitive adsorption of pollutants could be constructed to clarify the principles of multi-mechanism coupling by the combination of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, in-situ real-time monitoring, and characterization, etc.

(3) The potential of engineered biochar for practical industrial applications needs to be assessed. Although studies have shown that engineered biochar can improve adsorption performance, a comprehensive and systematic evaluation of its application in actual industrial wastewater is still required. This can be achieved by investigating techniques for the removal, recycling, and regeneration of multi-component contaminants. Moreover, from the perspective of safe utilization, it is essential to clarify the interaction mechanism of engineered biochar with environmental media, such as whether the use of nanomaterials increases potential ecotoxicity and health risks.

(4) Several key factors need to be considered when applying engineered biochar in practical contexts. Firstly, although the feedstocks for biochar are inexpensive, the recovery and regeneration process after saturation is complex and costly. Secondly, the complex composition and high concentration of pollutants in the actual wastewater impose greater demands on the reusability and stability of biochar. Finally, the adsorption process of biochar does not decrease the toxicity of pollutants. Consequently, to effectively eliminate pollutants from water, it is essential to consider coupling biochar with other technologies to further convert the pollutants into harmless substances.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: methodology, formal analysis: Wang N, Wang B; conceptualization: Wang B; writing − original draft preparation: Wang N; writing − review and editing: Wang B, Wang H, Wu P, Hassan M, Wang S, Zhang X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

No data and materials were used for the research described in the manuscript.

-

This work was supported by the Key Project of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (ZK[2022]016), the Special Fund for Outstanding Youth Talents of Science and Technology of Guizhou Province (YQK2023[014]), the Project of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (GCC[2023]045), the Science and Technology Support Program of Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province (QKHZC[2025]100), and the Foreign Expert Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology (No. Y20240039).

-

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Engineered biochars enable simultaneous removal of organic and metallic contaminants.

Co-adsorption occurs via bridging interactions and competitive binding mechanisms.

Tailored biochar modifications address diverse environmental pollution scenarios.

Performance metrics establish biochar viability across varied remediation applications.

Strategic roadmap identifies critical research priorities for biochar advancement.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang N, Wang B, Wang H, Wu P, Hassan M, et al. 2025. Engineered biochar for simultaneous removal of heavy metals and organic pollutants from wastewater: mechanisms, efficiency, and applications. Biochar X 1: e008 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0008

Engineered biochar for simultaneous removal of heavy metals and organic pollutants from wastewater: mechanisms, efficiency, and applications

- Received: 15 July 2025

- Revised: 21 August 2025

- Accepted: 17 September 2025

- Published online: 31 October 2025

Abstract: Organic compounds and heavy metals constitute two major classes of aquatic contaminants. Their prolonged simultaneous presence facilitates complexation reactions, which can generate novel toxicants with enhanced biological hazards. Therefore, developing advanced remediation technologies for the concurrent elimination of these remains imperative. As a carbon-rich material, biochar is considered an environmentally friendly and cost-effective adsorbent. Over the past decade, modification of biochar has emerged as a hot research topic. Strategic architectural and physicochemical modifications enable tailored surface properties and enhanced adsorption mechanisms, substantially expanding potential applications across environmental remediation domains. Despite emerging literature on the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and organic pollutants through engineered biochar, most research still focuses on the removal of single pollutants. This review examines the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and organic contaminants using functionalized biochar. Firstly, remediation efficiency, mechanistic pathways, and practical applications of engineered biochar are investigated for complex pollution matrices in aqueous environments. Secondly, physicochemical processes governing simultaneous contaminant capture through surface-modified carbon architectures are elucidated. Thirdly, performance across diverse wastewater treatment scenarios are evaluated, and environmental deployment viability assessed. This comprehensive analysis not only advances scientific understanding but also facilitates technological implementation of engineered biochar for the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and organic pollutants from wastewater.