-

Antibiotics have been widely applied in clinical medicine and livestock husbandry due to their ability to inhibit microbial cell proliferation[1]. Norfloxacin (NOR), a representative fluoroquinolone antibiotic, is one of the most extensively used globally. However, the unregulated discharge of NOR into aquatic environments has not only contributed to the evolution of antibiotic-resistant genes but also posed long-term threats to human health and ecological equilibrium[2]. As a refractory pollutant, NOR exhibits high toxicity, environmental persistence, and limited biodegradability, presenting significant challenges for efficient removal in wastewater treatment and environmental remediation. Consequently, the development of effective methods for NOR elimination from contaminated water has become a critical research priority.

To address this challenge, a range of treatment technologies has been developed, including adsorption, coagulation/flocculation, membrane separation, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). In particular, peroxymonosulfate (PMS)-based AOPs have garnered considerable attention as a promising strategy for the degradation of recalcitrant organic pollutants owing to their unique advantages[3]. In contrast to traditional AOPs, which primarily rely on hydroxyl radicals (•OH), PMS activation generates sulfate radicals (SO4•−) with a higher redox potential (2.5–3.1 V vs 1.9–2.4 V for •OH) and a longer half-life (30–40 μs vs ≤ 1 μs for •OH), thus enabling broader pH adaptability[4,5]. Moreover, PMS activation can generate singlet oxygen (1O2), a non-radical reactive oxygen species (ROS) with a redox potential of 2.2 V, which selectively targets electron-rich organic groups. This non-radical pathway can effectively mitigate interference from coexisting cations, anions, and natural organic matter in real water matrices, addressing a major limitation of radical-based AOPs[6]. Despite these merits, conventional PMS activation methods, such as those relying on metal-based catalysts or UV irradiation, suffer from several drawbacks, including high energy consumption, potential metal ion leaching that causes secondary pollution, and limited stability[7]. Mainstream carbon materials, including graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes, have demonstrated promising catalytic performances in PMS activation, due to their large surface area, tunable pore structures, and abundant morphological defects[8]. However, the high cost and complex synthesis of these carbon materials limit their scalable application.

Recently, biomass-derived carbon has emerged as a viable substitute, offering a means to convert renewable biomass into functional carbon while achieving waste valorization[9]. However, pristine biomass-derived carbon typically exhibited limited catalytic activity due to an insufficient number of active sites and poor electron transfer capability. Heteroatom doping (N, P, and S) has been demonstrated to enhance the catalytic activity of carbon materials by modulating their electronic structure and surface chemistry[10−12]. Specifically, nitrogen doping alters the charge distribution across the carbon lattice, and graphitic N species can facilitate the shift from radical-dominated mechanisms to more selective non-radical pathways, which are crucial for efficient catalysis in complex water environments[13]. Similarly, sulfur doping creates structural defects and forms thiophenic S sites that optimize the charge and spin density of adjacent carbon atoms, thereby enhancing PMS adsorption and activation[14]. A major challenge is that most existing studies on N-, S-codoped carbon catalysts rely on exogenous sulfur sources such as thiourea, sodium persulfate, or sulfuryl chloride, which not only increase synthesis costs but also introduce environmental risks, including toxic byproducts[15,16]. To address this issue of sustainability, natural biomass with intrinsic sulfur emerges as an ideal precursor for sulfur-doped carbon materials. Among such biomass sources, κ-carrageenan (κ-c), a sulfated polysaccharide extracted from red algae, contains abundant sulfate groups (–OSO3–) in its molecular structure, making it a renewable, low-cost, and environmentally benign source of both sulfur and carbon. Unlike exogenous sulfur reagents, the intrinsic sulfate groups in κ-c could be in-situ converted into thiophenic S during pyrolysis, simplifying the synthesis process and reducing environmental impact.

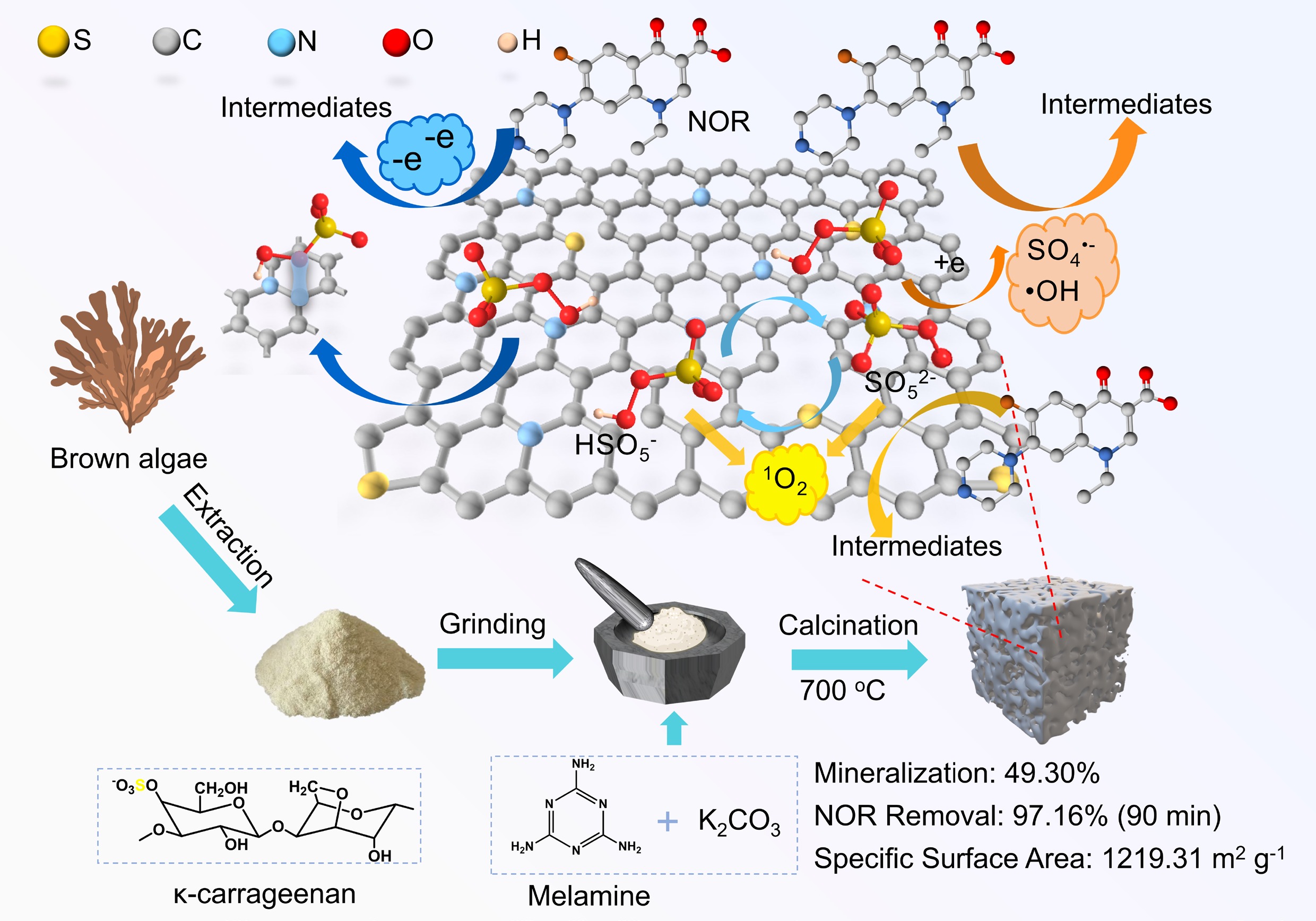

Building on this, the strategy constructs N-, S-codoped porous carbon (NSPC) by utilizing κ-c as natural dual sulfur/carbon precursors, melamine as the nitrogen source, and K2CO3 as a pore-forming activator. This innovative approach addresses key limitations in existing research by eliminating the need for toxic exogenous sulfur reagents and leveraging the intrinsic sulfate groups in κ-c for in-situ sulfur doping. This not only streamlined the synthesis process but also enhanced the sustainability of the catalyst. Furthermore, the synergistic effect of graphitic N and thiophenic S in NSPC selectively promoted two types of non-radical pathways, namely 1O2 generation and electron transfer, for NOR degradation. The two pathways account for over 84% of the total contribution. In addition, the NSPC-700 catalyst demonstrated excellent stability, overcoming the poor durability of previously reported biomass-derived carbon catalysts. The morphology and microstructure of NSPC were characterized, and the mechanism of PMS activation for NOR degradation was studied emphatically through quenching experiments, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and electrochemical tests. This work provides a sustainable route for designing metal-free carbon catalysts and offers new insights into non-radical-dominated PMS activation, promoting practical applications in antibiotic wastewater remediation.

-

κ-carrageenan (C24H36O25S2), methanol (MeOH, HPLC), tert-butanol (TBA, AR), furfuryl alcohol (FFA, AR), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4, AR), L-histidine, methylene blue (MB), and acetonitrile (CH3CN) were purchased from Aladdin reagent Inc. Acetic acid (CH3COOH, ≥ 99.5%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium chloride (NaCl, AR), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4, AR), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, AR), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, AR), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, AR), potassium peroxymonosulfate (KHSO5·0.5KHSO4·0.5K2SO4, ≥ 42%), NOR, sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3, AR), 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO, 97%), and 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone (TEMP, 98%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Humic acid (HA) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were of analytical grade and were used without further purification.

Catalysts preparation

-

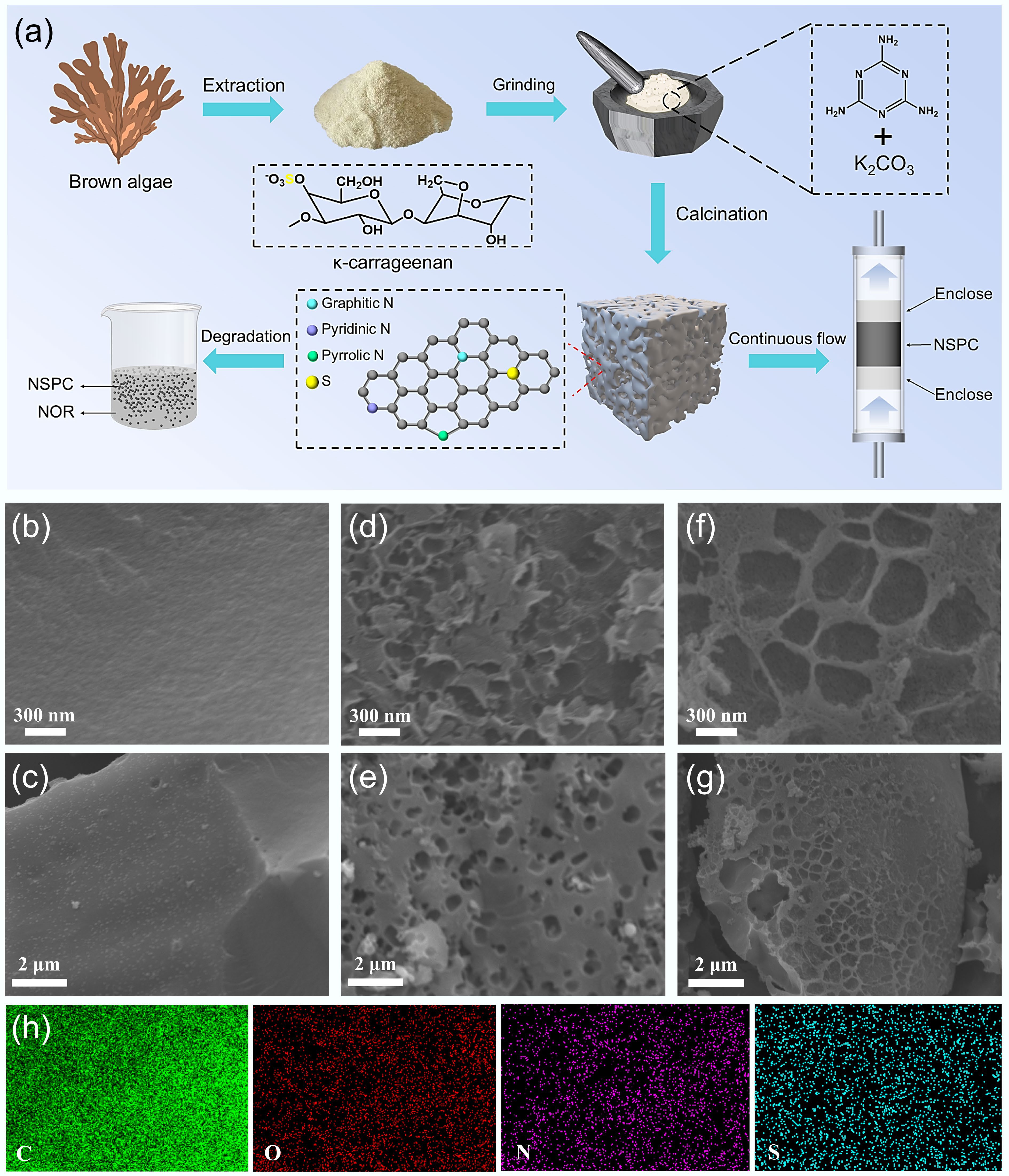

NSPC was prepared via direct pyrolysis, as shown in Fig. 1a. A mixture of 1.0 g of κ-carrageenan (κ-c), melamine, and K2CO3 was thoroughly ground for 20 min. The resulting powder was then transferred to a tube furnace and pyrolyzed under an argon atmosphere at different target calcination temperatures (500, 600, 700, and 800 °C) with a heating rate of 5 °C min–1 and a dwell time of 2 h. After pyrolysis, the products were washed with ethanol and deionized water, collected by filtration, and dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h. The resulting materials were named as NSPC-500, NSPC-600, NSPC-700, and NSPC-800, respectively. For comparison, a control sample was prepared by pyrolyzing κ-c alone under identical conditions at 700 °C, denoted as SC-700. Additionally, a composite without melamine was also processed at 700 °C and referred to as SPC-700.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of NSPC preparation. (b), (c) SEM images of SC-700. (d), (e) SPC-700. (f), (g) NSPC-700. (h) EDS mapping images of C, N, and O in NSPC-700.

Catalysts characterization

-

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to visualize the surface morphology of the catalysts, combined with the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Specific surface area, porosity, and pore size distribution were studied using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) N2 adsorption/desorption method. The pore size distribution (PSD) was determined by analyzing the adsorption branch of the isotherm using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method. Raman spectroscopy data were obtained using a Raman spectrometer (Raman, Nicolet 5700, ThermoFisher, USA). The surface chemical composition and valence states of the elements were distinguished by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (ESCALab 250). Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined using a TOC analyzer (TOC-L CPH, Shimadzu, Japan).

Catalytic degradation experiments

-

All NOR degradation experiments were performed at room temperature under constant magnetic stirring (500 r min–1). The initial pH was adjusted to 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 9.0, and 11.0 with 0.1 M NaOH and 0.1 M acetic acid, respectively. A typical degradation system contained 0.4 g L–1 catalyst, 1 mM PMS, and 20 mg L–1 NOR. Prior to the catalytic reaction, 0.4 g L–1 catalyst was introduced into the NOR solution and stirred for 60 min to achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium. Subsequently, the reaction was initiated by adding 1 mM PMS. At predetermined time intervals (2, 5, 10, 30, 60, and 90 min), 1.0 mL of the reaction solution was sampled and immediately quenched with 0.2 mL of Na2S2O3, followed by filtration through a 0.22 µm organic filtration membrane. After the degradation, the catalyst was separated, rinsed thoroughly with deionized water and anhydrous ethanol, and dried.

Analytical methods

-

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, 1260II, Agilent, USA) with an Agilent C18 column was used to analyze the change in NOR concentration. Supplementary Text S1 provides the detailed HPLC information. Electrochemical tests were performed in a three-electrode cell using an electrochemical analyzer (CHI 760E, Shanghai Chenhua, China), and detailed test conditions are described in Supplementary Text S2. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements were performed on an EPR spectrometer (Bruker, EMX Plus, Germany) with DMPO and TEMP as spin trapping reagents for free radicals and singlet linear oxygen species. Detailed test conditions are given in Supplementary Text S3.

-

SEM images of SC-700, SPC-700, and NSPC-700 are presented in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1b, c, SC-700, which was derived from the direct carbonization of κ-c without activation, exhibited a relatively smooth and non-porous morphology, suggesting a limited specific surface area. In contrast, SPC-700 (activated solely by K2CO3 at 700 °C, Fig. 1d, e) displayed a markedly rough surface with abundant pores that were several hundred nanometers in diameter. Notably, NSPC-700 (Fig. 1f, g) retained a similar porous architecture to that of SPC-700, confirming that the porous framework was preserved upon N doping. Both SPC-700 and NSPC-700 possessed well-developed, highly porous structures with adequate small pores and channels, forming a hierarchical porous architecture. The pores were irregularly shaped and ranged in size from tens to hundreds of nanometers, and were interconnected to form a complex, three-dimensional network. These results demonstrated that K2CO3 activation effectively endowed the biochar with a high specific surface area and large pore volume, which were crucial to enhance adsorption capacity and provide ample sites for loading active species. The pore formation mechanism involves the condensation of carbon into aromatic skeletons during pyrolysis, followed by K2CO3 etching of the carbon framework at elevated temperatures, thereby generating porous structures. This porous network facilitated the exposure of active sites, promoted the transport of reactive species, and enhanced the mass transfer and adsorption of pollutant molecules. Furthermore, EDS mapping in Fig. 1h confirmed the homogeneous distribution of C, O, N, and S in the NSPC-700 catalyst.

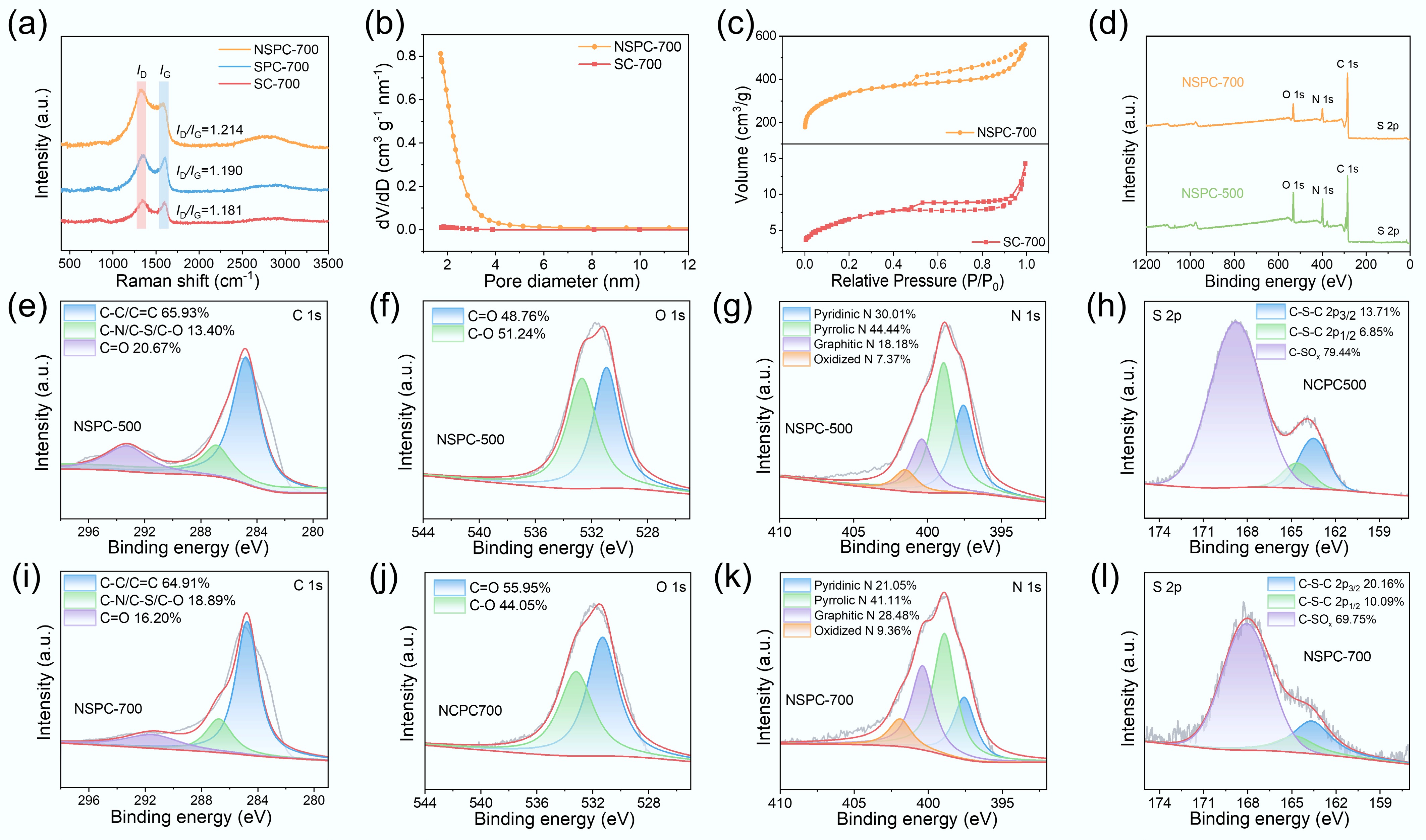

Raman spectroscopy probed the lattice vibrations within the carbon materials, providing critical insights into their structural disorder and graphitization degree. As shown in Fig. 2a, the Raman spectra for all materials exhibited the characteristic D band (~1,350 cm–1) and G band (~1,580 cm–1), which were indicative of defective carbon structures and graphitic domains, respectively. The D band was associated with structural disorders and defects, such as those induced by vacancies or heteroatom doping. The presence of such defects, including edge sites and vacancies, played a crucial role in initiating the formation of porous networks during synthesis. In contrast, extrinsic defects could be introduced by pyrolyzing carbon precursors mixed with heteroatom sources (e.g., N, B, and S). The G band corresponded to the in-plane vibration of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms in ordered, graphitic structures. The intensity ratio of the D to the G band (ID/IG) was widely used to evaluate the defect density and structural disorder in carbon materials. The ID/IG values corresponding to SC-700, SPC-700, and NSPC-700 increased from 1.181 to 1.190 and 1.214, respectively. The increase in the ID/IG ratio from SC-700 to SPC-700 was primarily attributed to K2CO3 activation. This process enhanced porosity and generated additional defects, such as jagged and armchair edges, as well as vacancies (missing carbon atoms in the matrix), at elevated temperatures. The further increase in the ID/IG ratio for NSPC-700 (1.214) indicated that N-doping introduced additional defects beyond those generated by K2CO3 activation alone. The heteroatom-induced defects were readily incorporated through the co-pyrolysis of carbon and heteroatom precursors.

Figure 2.

(a) Raman mapping images of SC-700, SPC-700, and NSPC-700. (b) N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms, and (c) pore size distribution curves of SC-700, and NSPC-700. (d) XPS survey spectra of NSPC-500 and NSPC-700. High-resolution XPS spectra of (e), (i) C 1s, (f), (j) O 1s, (g), (k) N 1s, and (h), (l) S 2p for NSPC-500 and NSPC-700.

The quantitative effects of K2CO3 activation and N-doping on the pore structure of κ-c-derived carbon were further evaluated by N2 adsorption-desorption analysis and PSD measurements (Fig. 2b, c). PSD analysis confirmed that the pore structure of NSPC-700 was predominantly composed of micropores and mesopores. As summarized in Supplementary Table S1, the specific surface area increased dramatically from 23.58 m2 g–1 for SC-700 to 1,219.31 m2 g–1 for NSPC-700 after K2CO3 activation. Correspondingly, the total pore volume increased markedly from 0.022 to 0.87 cm3 g–1. This significant enhancement in porosity, consistent with the SEM observations, demonstrated the critical role of K2CO3 as an effective activating agent. The resulting porous framework facilitated the exposure of active sites and improved mass transfer, thereby promoting PMS activation.

XPS analysis was performed to determine the surface elemental composition and chemical states of the catalysts. The survey spectra in Fig. 2d exhibited four distinct peaks, confirming the presence of O, N, C, and S elements in NSPC-700, respectively. The atomic percentages of C, O, N, and S were quantified as 70.81%, 12.05%, 15.76%, and 1.37% for NSPC-500, and 80.27%, 8.54%, 10.7%, and 0.48% for NSPC-700, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). Notably, the atomic contents of O, N, and S decreased with increasing pyrolysis temperature. This trend suggested the thermal decomposition and elimination of oxygen-containing functional groups, as well as the possible cleavage of less stable C–N bonds, at elevated temperatures. The high-resolution C 1s spectra of NSPC-500 and NSPC-700 (Fig. 2e, i) were subdivided into three component peaks at 291.49 eV (C=O), 286.76 eV (C-N/C-S/C-O), and 284.77 eV (C-C/C=C)[17]. The decrease in C=O peak intensity at higher temperatures was consistent with the overall reduction in O content, which reaffirmed the loss of oxygen-containing groups. The high-resolution O 1s spectra (Fig. 2f, j) were fitted with peaks at 533.2 eV (C–O) and 531.31 eV (C=O)[18]. Among the remaining oxygen species in NSPC-700, the proportion of thermally stable C=O groups was higher compared to NSPC-500.

The N 1s spectra (Fig. 2g, k) were resolved into four types of nitrogen species: oxidized N (401.91 eV), graphitic N (400.39 eV), pyrrolic N (398.91 eV), and pyridinic N (397.57 eV)[12]. These N species could modulate the electron density of adjacent carbon atoms, thereby facilitating the adsorption and activation of PMS. Graphitic N exhibited higher stability in NSPC-700 and was considered to play a dominant role, as it effectively activated PMS to generate 1O2, thereby improving the selectivity and interference resistance of the catalyst. As the temperature increased from 500–700 °C, the relative content of graphitic N rose from 18.18% to 28.48%, while the proportions of pyrrolic N and pyridinic N decreased from 44.44% to 41.11% and from 30.01% to 21.05%, respectively. This transformation indicated the conversion of less stable nitrogen configurations (pyridinic N and pyrrolic N) into the more thermally stable graphitic N at high temperatures. Thus, pyrolysis temperature effectively modulated the N speciation, optimizing the population of active sites. The high-resolution S 2p spectra (Fig. 2h, l) exhibited a doublet at 164.75 and 163.65 eV, characteristic of thiophenic S[19], which was another effective site for PMS activation. The content of thiophenic S increased from 20.56% to 30.25% as the temperature rose from 500 to 700 °C. The existence of thiophenic S double peaks was due to spin-orbit interactions. The peak at 168.1 eV corresponded to oxidized S (C-SOx). Collectively, graphitic N and thiophenic S served as synergistic active sites for promoting PMS activation.

Degradation performances of NSPC

-

The catalytic performance of the synthesized NSPC was evaluated in a PMS-based system using NOR as the target pollutant. Prior to the catalytic testing, the catalysts were equilibrated in the NOR solution for 60 min to establish adsorption-desorption equilibrium, ensuring that the subsequent removal was primarily attributable to catalytic activation. As shown in Fig. 3a, control experiments confirmed that PMS alone achieved only 15.59% NOR removal, indicating a negligible decomposition. Similarly, the non-activated SC-700 showed low catalytic activity, demonstrating its inability to activate PMS effectively. The adsorption capacities of SPC-700 and NSPC-700 were similar (30%), which represented a significant enhancement compared with the 5.44% adsorption by SC-700. This result confirmed that K2CO3 activation successfully created porous structures that facilitated contact between the catalyst and pollutant. The NOR removal efficiencies for SC-700, SPC-700, and NSPC-700 reached 28.32%, 80.69%, and 97.16%, respectively. The significantly enhanced performance of SPC-700 over SC-700 was attributed to the improved mass transfer and active site exposure resulting from K2CO3 activation. While SPC-700 containing S-sites achieved 80.69% NOR removal, the codoping of N and S in NSPC-700 led to a synergistic effect, further elevating the removal efficiency to 97.16%. These results suggest that S-sites played a key role in PMS activation, while the introduction of N-sites provided a critical synergistic enhancement.

Figure 3.

Effect of (a) different catalytic systems, (b) carbonization temperature, (c) rate constants for different systems, (d) mass ratio of κ-c to melamine, (e) initial pH, (f) presence of natural organic matter and inorganic anions on NOR degradation, (g) TOC removal, and (h) Comparison with other reported catalysts. Experimental conditions unless otherwise specified: [NOR]0 = 20 mg L−1, [PMS]0 = 1.0 mM, room temperature, and pH = 7.0.

The pyrolysis temperature was a critical parameter that significantly modulated the electronic conductivity, defect density, and heteroatom speciation of carbon catalysts. The properties of NSPC synthesized at 500, 600, 700, and 800 °C were evaluated (Fig. 3b). The adsorption capacity increased markedly with pyrolysis temperature, rising from only 0.35% for NSPC-500 and 3.18% for NSPC-600 to 30.10% for NSPC-700. This substantial increase for NSPC-700 was attributed to the effective activation by K2CO3, which becomes significant at around 700 °C. At lower temperatures (< 700 °C), insufficient pores and low specific surface area limited the contact between the catalyst and NOR molecules. The NOR removal efficiency increased dramatically from 26.58% (NSPC-500) and 52.83% (NSPC-600) to 97.16% (NSPC-700) as the temperature rose from 500 to 700 °C. This enhancement was correlated with the increased specific surface area and pore volume, which facilitated mass transfer. Furthermore, XPS analysis indicated that the chemical composition evolved with temperature. The NSPC-700 possessed higher contents of graphitic N and thiophenic S compared to NSPC-500. When the temperature was further increased to 800 °C, the adsorption capacity of NSPC-800 continued to rise, indicating more vigorous etching by K2CO3. However, its catalytic performance declined to 91.94%. This decline was likely due to the volatilization of N and S species at extremely high temperatures, leading to a loss of active sites. The degradation rate constant (Kobs) further confirmed this trend: SC-700, NSPC-500, NSPC-600, SPC-700, NSPC-800, and NSPC-700 were 0.0033, 0.0047, 0.0122, 0.0195, 0.0218, and 0.0403 min–1, respectively (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Text S4). Therefore, NSPC-700 represented an optimal balance, combining highly porous structures, large specific surface area, and high density of active sites (graphitic N and thiophenic S) to promote NOR degradation effectively. The effect of the κ-c to melamine mass ratio was also investigated (Fig. 3d). The NOR removal efficiency by NSPC-700 increased gradually from 82.39% (4:1 ratio) to 97.16% (2:1 ratio) and 98.28% (1:1 ratio). This suggested that the nitrogen content approached saturation at a 2:1 ratio, beyond which further addition yielded diminishing returns. Therefore, considering both catalytic efficiency and resource economy, NSPC-700, synthesized at 700 °C with a κ-c to melamine ratio of 2:1, was selected for subsequent experiments.

The solution pH significantly influenced catalytic performances. As shown in Fig. 3e, the NOR removal efficiency was highest (97.16%) at neutral pH. It decreased to 58.42% and 63.19% at pH = 3 and 5, respectively, and declined to 92.64% and 57.81% at pH = 9 and 11. Under acidic conditions, the activation of PMS was hindered as H+ could form hydrogen bonds with the O–O group, reducing its reactivity[20]. In strongly acidic environments, excess protons may have scavenged ROS, further diminishing the removal efficiency. The pKa of PMS was 9.4. Thus, under strong alkaline conditions (pH > 9.4), PMS predominantly existed as SO52–, which was more difficult to activate than HSO5– [21]. At pH = 9, where HSO5– remained the major species, the inhibition was less pronounced. The surface charge of NSPC-700 was assessed by zeta potential measurements (Supplementary Fig. S1). The point of zero charge (pHpzc) of NSPC-700 was 4.71, indicating a positively charged surface below this pH and a negatively charged surface above it. NSPC-700 carried a positive charge at pH < 4.71 and a negative charge at pH > 4.71. The pKa values of the dissociation constants of NOR were 6.32 and 8.47. NOR existed predominantly as a cation (NOR+) at solution pH < 6.32, as an anion (NOR−) at pH > 8.47, and as an amphipathic ion (NOR±/NOR0) at pH in the range of 6.32–8.47. In highly acidic and alkaline environments, NSPC-700 and NOR possessed like charges (positive-positive or negative-negative), resulting in electrostatic repulsion. This was evidenced by the decreased adsorption capacity to 19.53% (pH = 5) and 13.49% (pH = 11), which subsequently inhibited the interfacial generation of ROS and electron transfer, ultimately reducing the degradation efficiency.

To investigate the effects of HA and inorganic anions in natural water on NOR degradation, several common anions and HA commonly found in groundwater were added to the NSPC-700/PMS/NOR system. As shown in Fig. 3f, the presence of 10 mM of Cl–, SO42–, H2PO4–, HCO3–, and 5 mg L–1 HA inhibited NOR removal to varying degrees, with the removal efficiencies dropping to 66.01%, 76.15%, 95.21%, 75.88%, and 88.48%, respectively. The system exhibited strong resistance to H2PO4–, as the removal efficiency remained high. The presence of Cl– and SO42– could potentially compete with NOR for active sites or scavenge reactive species, leading to the observable inhibition of degradation efficiency[22]. Similarly, HA competed with NOR for active sites on the catalyst surface and could scavenge ROS. HCO3– elevated the solution pH, creating an alkaline environment that affected the removal of NOR. However, it was noteworthy that the system still maintained NOR removal efficiency of over 66% even with 10 mM of these anions, demonstrating its considerable resistance in complex water matrices. This performance was attributed to the high specific surface area of the catalyst, which provided abundant active sites, coupled with the inherent resistance of the dominant non-radical pathways to quenching by common anions.

The TOC removal reached 49.3% within 90 min (Fig. 3g), indicating a significant mineralization of NOR into CO2 and H2O. The catalyst also effectively degraded MB (Supplementary Fig. S2), demonstrating its potential universality for treating organic pollutants. In addition, a comparative study with other advanced oxidation systems based on metallic or non-metallic catalysts was summarized in Fig. 3h. The NSPC-700 possessed a superior reaction rate constant (Kobs = 0.0403 min–1), highlighting its great potential as an efficient catalyst[11,23−30].

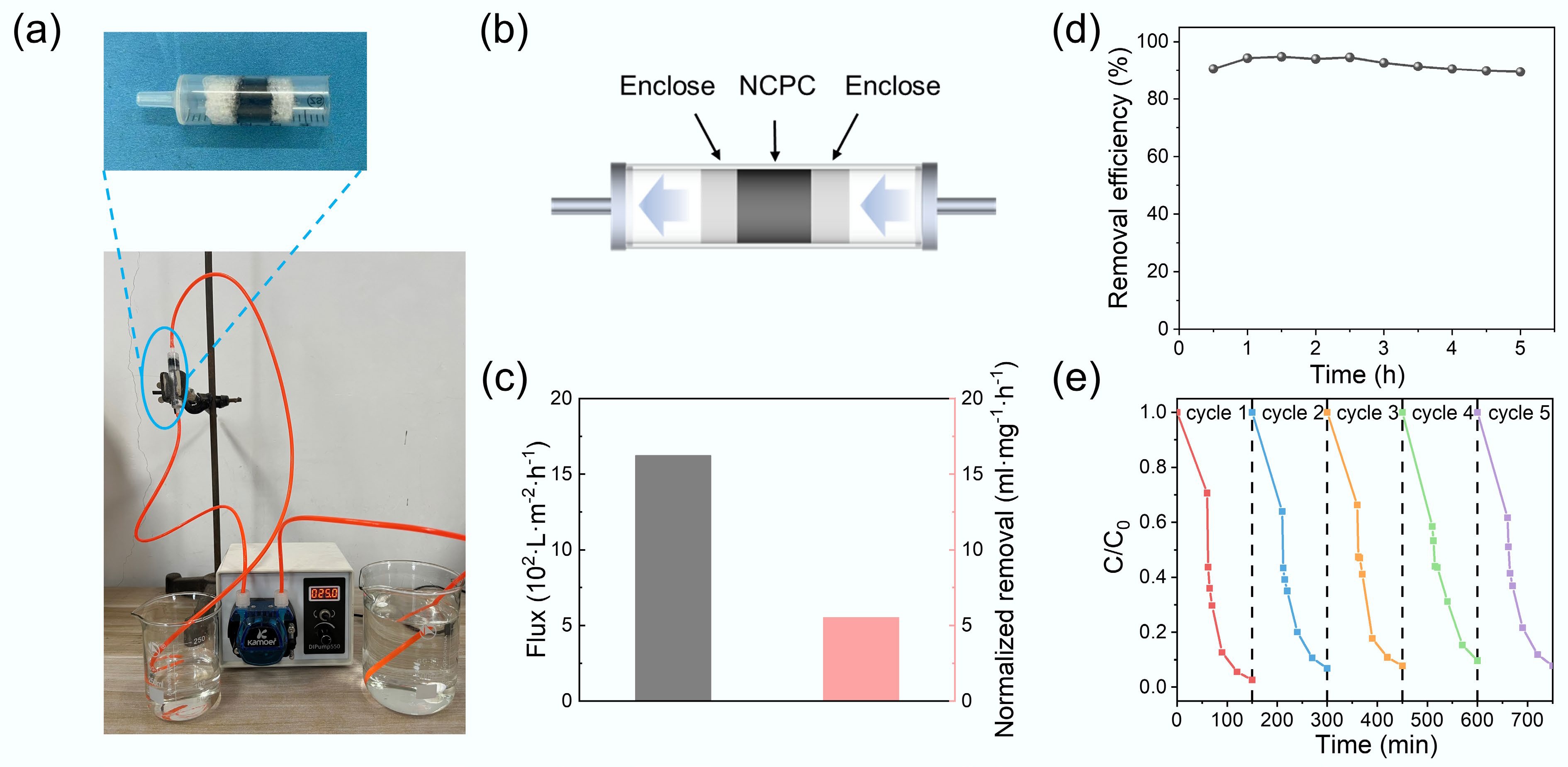

To assess the practical applicability of the catalyst, a homemade flow-through device was constructed to evaluate NOR removal under continuous flow conditions. As shown in Fig. 4a, b, NSPC-700 was packed into a syringe, with foam plugs at both ends to prevent catalyst leakage. A solution containing 1 mM PMS and 10 mg L–1 NOR was circulated through the device at a flow rate of 4 mL min–1 using a peristaltic pump. As shown in Fig. 4c, the system exhibited a flux of 1,558 L m–2 h–1, corresponding to a NOR removal capacity of 6.9 mL mg–1 h–1. As shown in Fig. 4d, a high NOR removal efficiency (94.00%) was maintained for the first 2.5 h of continuous operation. After 5 h, the removal efficiency remained at 89.00%, demonstrating satisfactory operational stability. These results indicated the good practical potential of NSPC-700 for continuous-flow wastewater treatment. The cycling performance of the catalyst was an important parameter for assessing its practical application potential. After each cycle, the spent catalyst was recovered by centrifugation, washed alternately with deionized water and ethanol, dried, and then reused. As shown in Fig. 4e, the NOR removal efficiency remained at 93.17%, 92.23%, 90.36%, and 92.18% over the second, third, fourth, and fifth cycles, respectively. Although a slight decrease from the first cycle was observed, the catalyst consistently retained over 90% of its initial activity across five cycles, demonstrating its excellent stability and reusability. The slight decrease in catalyst performance may be attributed to the gradual consumption or oxidation of active sites during the reaction. Both the continuous flow and cycling experiments confirmed the long-term stability of the synthesized NSPC-700 catalyst.

Figure 4.

(a) Continuous flow devices. (b) Schematic diagram of the degradation device. (c) Continuous flow device flux and removal efficiency. (d) Removal efficiency of NOR for 5 h. (e) Cycling performances.

Mechanism insights of PMS activation by NSPC

Quenching results, EPR, and electrochemical analyses

-

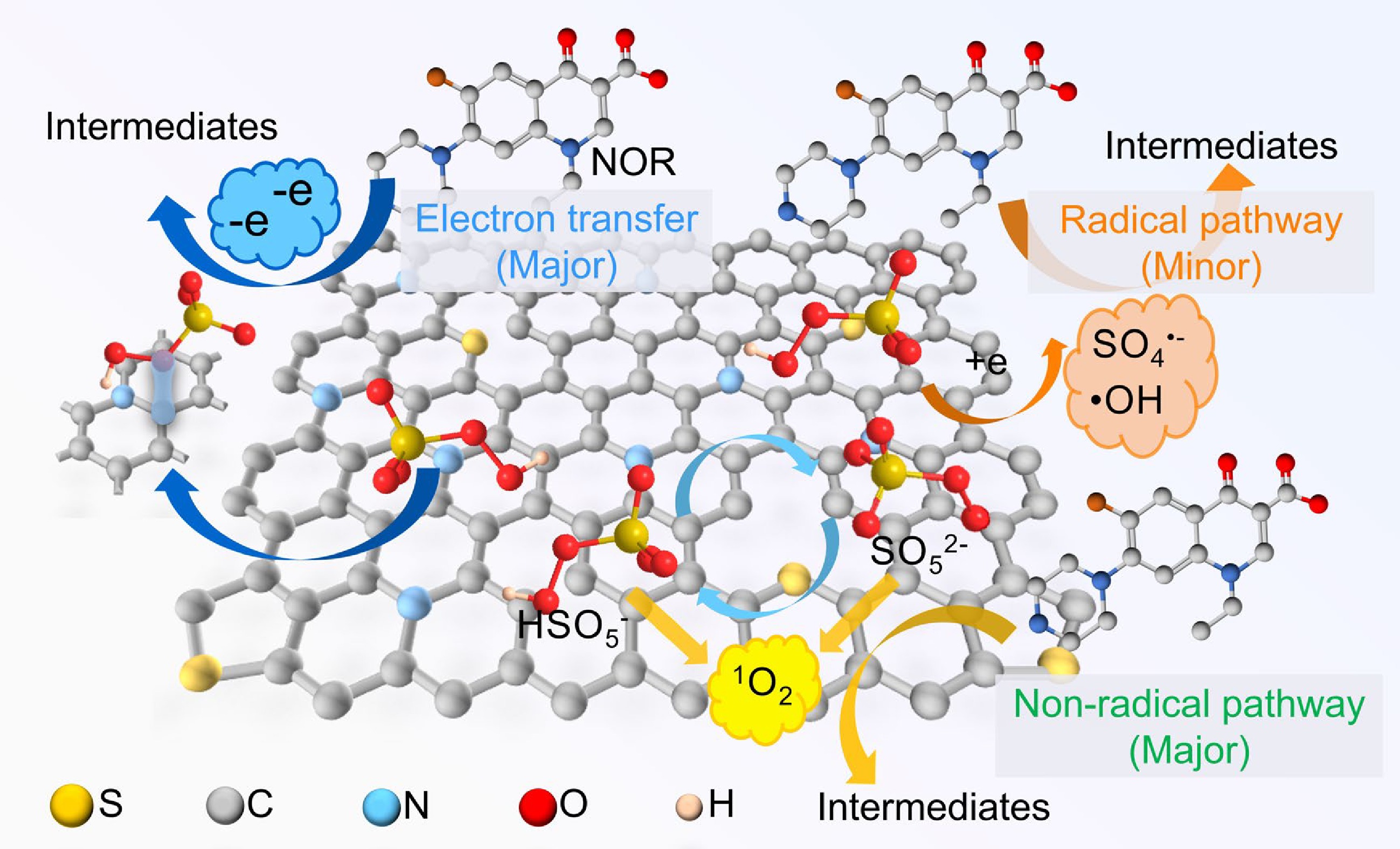

Quenching experiments were performed to identify the reactive species involved in the degradation process. Methanol (MeOH) reacts with SO4•− (kSO4•− = 2.5 × 107 M−1 s−1) and •OH (k•OH = 9.7 × 108 M−1 s−1) and tert-butanol (TBA) reacts only with •OH (k•OH = 6.0 × 108 M−1 s−1), and both were employed to probe radical pathways. As shown in Fig. 5a, the addition of 100 mM MeOH and TBA caused NOR removal efficiency to decrease to 93.08% and 89.12%, respectively. The slightly stronger inhibition of TBA than MeOH could be attributed to competitive adsorption between TBA and NOR on the catalyst surface, potentially due to hydrophobic interactions[31]. These results suggested that SO4•− and •OH play a minor role in the NSPC-700/PMS system. Furfuryl alcohol (FFA, 50 mM) was introduced, reducing NOR removal to 84.66%. To rule out the possibility that FFA itself depleted PMS, L-histidine (10 mM) as another selective 1O2 scavenger was also added, yielding a similar inhibitory effect (83.65% removal). These consistent results confirmed that 1O2 was a significant ROS and its contribution surpasses that of free radicals.

Figure 5.

(a) Quenching experiments. DMPO and TEMP spin-trapping EPR spectra of (b) O2•−, (c) SO4•−/•OH, and (d) 1O2 in NSPC-700/PMS system. (e) EIS measurement of SC-700, NSPC-600, and NSPC-700. (f) I-t curve of SC-700, NSPC-600, and NSPC-700. (g) Contribution of different oxidation pathways in the NSPC-700/PMS/NOR system. XPS spectra of used NSPC-700 for (h) N 1s, and (i) S 2p.

EPR spectroscopy was further employed to directly detect reactive species. DMPO acted as a trapping agent for O2•−, SO4•−, and •OH, and TEMP acted as a trapping agent for 1O2[32]. The peak intensities were tested at different time intervals (0, 2, 5, 10, and 20 min) after the addition of PMS. The signal for DMPO-O2•− was weak and remained unchanged over 20 min (Fig. 5b), indicating that superoxide radical (O2•−) was not involved in the degradation process. As shown in Fig. 5c, the peaks of DMPO-•OH and DMPO-SO4•− were detected initially but diminished over time, suggesting that •OH and SO4•− were generated transiently but were not the dominant persistent species. In contrast, the characteristic triplet signal of TEMP-1O2 was clearly observed, and its intensity increased steadily over time (Fig. 5d), demonstrating the continuous generation of 1O2 during the reaction. The overall signal intensity of TEMP-1O2 was much stronger than that of DMPO-O2•−, DMPO-•OH, and DMPO-SO4•− (Supplementary Fig. S3), providing direct evidence that 1O2 was the primary ROS during degradation, and the roles of SO4•−, •OH, and O2•− were negligible.

The quenching experiments showed that the NOR removal efficiency was inhibited but not completely suppressed, indicating that a significant portion of degradation proceeded via non-radical pathways. This implied the existence of a major degradation pathway other than ROS oxidation. To verify this, a series of electrochemical tests was conducted to probe the electron transfer mechanism. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) results (Supplementary Fig. S4a) showed a significant current increase upon PMS addition, confirming the formation of a metastable complex. A further current surge after NOR injection signified an electron transfer process from NOR to the activated PMS complex[33]. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves in Supplementary Fig. S4b indicated that NSPC-700 possessed the most pronounced redox capability among the tested samples. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements in Fig. 5e revealed the smallest semicircle diameter for NSPC-700, followed by NSPC-600 and SC-700, indicating that the higher preparation temperature resulted in better interfacial electron transfer. This enhanced electron transfer was attributed to the higher graphitic N content facilitated by the elevated pyrolysis temperature, which improved the electrical conductivity of the carbon matrix[34]. The I-t curve (Fig. 5f) showed the most significant current response for NSPC-700. A sharp current increase upon PMS addition indicated the formation of a metastable NSPC-700/PMS* complex, after which the current decreased with NOR injection, corresponding to electron transfer from NOR to the complex[35]. Collectively, the electrochemical analyses (EIS, I-t, CV, and LSV) confirmed an efficient electron transfer pathway in the NSPC-700/PMS system.

As summarized in Fig. 5g, the contributions of different degradation pathways were quantified as 15.38% (•OH&SO4•−), 46.56% (1O2), and 38.06% (electron transfer), respectively (Supplementary Text S5). This indicated the dominance of non-radical pathways, with a combined contribution of 84.62%, whereas the role of radical species was only 15.38%.

Degradation mechanism

-

XPS analysis of NSPC-700 after five cycles confirmed the retention of C, N, O, and S. The S content remained notably stable at 0.48%, indicating the effective stabilization of endogenous sulfur derived from the natural precursor. The observed increase in oxygen content (from 8.54% to 9.40%) was likely attributable to surface oxidation occurring during the catalytic process (Supplementary Table S2). The high-resolution C 1s and O 1s spectra (Supplementary Fig. S5a, S5b) revealed preserved functional groups, suggesting good structural stability. Analysis of N species (Fig. 5h) showed a decline in pyridinic N (21.05% to 18.13%) and graphitic N (28.48% to 23.24%), along with an increase in pyrrolic N and oxidized N. This demonstrated that graphitic N acted as the main functioning N species in the NSPC-700/PMS system. The S 2p spectrum (Fig. 5i) indicated a slight decrease in thiophenic S and a marginal rise in oxidized S. The minor changes in the key active sites (graphitic N and thiophenic S) underscored the structural durability of NSPC-700.

Based on the quenching experiments, EPR tests, electrochemical analysis, and XPS results, the non-radical pathway in the NSPC-700/PMS/NOR system played a dominant role, while the radical pathway served a secondary role. As illustrated in Fig. 6 and Eqs (1)–(6), the degradation mechanism proceeds as follows: First, PMS was adsorbed on the N and S sites on the catalyst surface. This adsorption facilitated O-O bond cleavage in PMS, generating transient radical species (SO4•− and •OH) as illustrated in Eqs (1)−(3). Concurrently,1O2 was produced either through the self-decomposition of PMS or the formation of SO5•− as an intermediate as illustrated in Eqs (4)−(6). Simultaneously, a metastable NSPC-700/PMS* complex was formed, enabling a direct electron-transfer pathway from NOR to NSPC-700/PMS*. In summary, the superior performance of NSPC-700 originated from the synergistic effect of N and S co-doping, which collaboratively enhanced PMS adsorption, facilitated electron transfer, and promoted the dominant non-radicals degradation pathways.

$ \rm{HSO}_{{5}}^{ -}\to {\text •}OH+SO_{{4}}^{{\text•}-} $ (1) $ \rm {HSO}_{ 5}^{-} + e^{-}\to SO_{ 4}^{ 2-} + {{\text •}OH} $ (2) $ \rm {HSO}_{ 5}^{-} + {e}^{-} \to {SO}_{4}^{{\text •}-} + {OH}^{-} $ (3) $ \rm{HSO}_{ 5}^{-} +{SO}_{5}^{2-} \to {HSO}_{4}^{-} + {SO}_{ 4}^{ 2-} + {}^{{1}}{O}_{{2}} $ (4) $ \rm{HSO}_{5}^{-} \to {e}^{-} + {H}^{ +} + {SO}_{{5}}^{ {\text •}-} $ (5) $ \rm{2SO}_{ {5}}^{ {\text •}-} \to {2SO}_{4}^{2-} +{}^{ 1} {O}_{2} $ (6) -

In this study, N- and S-codoped porous carbon catalysts were synthesized using κ-carrageenan as natural precursors of sulfur and carbon, with melamine as a nitrogen source and K2CO3 serving as a chemical activator. This approach effectively circumvents the need for exogenous, toxic sulfur reagents, thereby enhancing the environmental sustainability of the synthesis process. The prepared NSPC-700 exhibited a high specific surface area of 1,219.31 m2 g–1 and contained substantial amounts of graphitic N and thiophenic S species, which were identified as critical active sites for PMS activation. The NSPC-700 catalyst demonstrated excellent performance in the degradation of NOR, achieving 97.16% NOR removal and 49.30% mineralization efficiency within 90 min. More importantly, the NSPC-700/PMS system demonstrated remarkable stability and practical potential, sustaining 89.00% NOR removal over 5 h in a continuous-flow operation and retaining 90.36% degradation efficiency after five consecutive cycles. Mechanistic studies confirmed that the degradation process was dominated by non-radical pathways, with 1O2 and electron transfer contributing 46.56% and 38.06%, respectively. This work highlighted the innovative utilization of intrinsic sulfur from biomass to construct high-performance metal-free carbon catalysts, providing a green and scalable alternative to conventional heteroatom-doped carbon materials. The proposed synthesis strategy not only realizes waste valorization of marine biomass but also offers new insights into the structural design of an efficient PMS activator for refractory antibiotic degradation.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/bchax-0025-0012.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Xiangyu Wang: investigation, data curation, writing-original draft; Lei Shi: investigation, data curation; Hongjiao Chen: formal analysis, data curation; Yuanyuan Sun: formal analysis, resources; Dongjiang Yang: supervision, methodology, formal analysis; Bin Hui: supervision, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, resources, funding acquisition, writing - review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The authors confirm that All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors are grateful to financial support by Excellent Youth Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2022YQ22), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 32571960 and 32101451), and the Youth Innovation Team Project of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2022KJ303).

-

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

N-, S-codoped porous carbon was synthesized using κ-carrageenan as S/C sources, melamine as the N source, and K2CO3 as the activator.

The NSPC-700 exhibited a high specific surface area (1,219.31 m2 g–1) and abundant graphitic N and thiophenic S sites.

The resulting NSPC-700 achieved 97.16% NOR removal and a mineralization efficiency of 49.30% within 90 min.

The catalyst maintained 89.00% NOR removal efficiency in a continuous-flow system over 5 h.

The degradation was dominated by non-radical pathways, with singlet oxygen (46.56%), and electron transfer (38.06%).

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang X, Shi L, Chen H, Sun Y, Yang D, et al. 2025. κ-carrageenan-derived N-, S-codoped porous carbon promotes peroxymonosulfate activation for norfloxacin degradation. Biochar X 1: e012 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0012

κ-carrageenan-derived N-, S-codoped porous carbon promotes peroxymonosulfate activation for norfloxacin degradation

- Received: 26 September 2025

- Revised: 13 November 2025

- Accepted: 24 November 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: Developing high-performance, sustainable carbon-based catalysts for degrading refractory organic pollutants is of critical significance in environmental remediation. Presented herein is a new metal-free N- and S-codoped porous carbon (NSPC) by utilizing κ-carrageenan (a natural marine biomass with intrinsic sulfate groups) as a dual source of sulfur and carbon, alongside melamine (the N source) and K2CO3 (the activator). This approach avoided the reliance on toxic exogenous sulfur reagents, simplifying the synthesis process while enhancing sustainability. The synthesized NSPC-700 exhibited a high specific surface area of 1,219.31 m2 g–1 and abundant active sites (graphitic N and thiophenic S), achieving an exceptional norfloxacin (NOR) removal efficiency of 97.16% and a mineralization efficiency of 49.30% within 90 min. Mechanistic studies identified graphitic N and thiophenic S as key active sites, and revealed that the degradation was dominated by non-radical pathways, specifically singlet oxygen (1O2) and electron transfer (total contribution > 84%). Furthermore, NSPC-700 demonstrated excellent practical potential: it maintained an 89.00% NOR removal efficiency in a continuous-flow system over 5 h and retained a 90.36% removal efficiency after five consecutive cycles. This work highlights the innovative use of intrinsic sulfur-source biomass to transform into a value-added carbon catalyst, offering a green, sustainable strategy for antibiotic wastewater remediation.

-

Key words:

- Porous carbon /

- κ-carrageenan /

- N, S co-doping /

- Peroxymonosulfate activation /

- Norfloxacin degradation