-

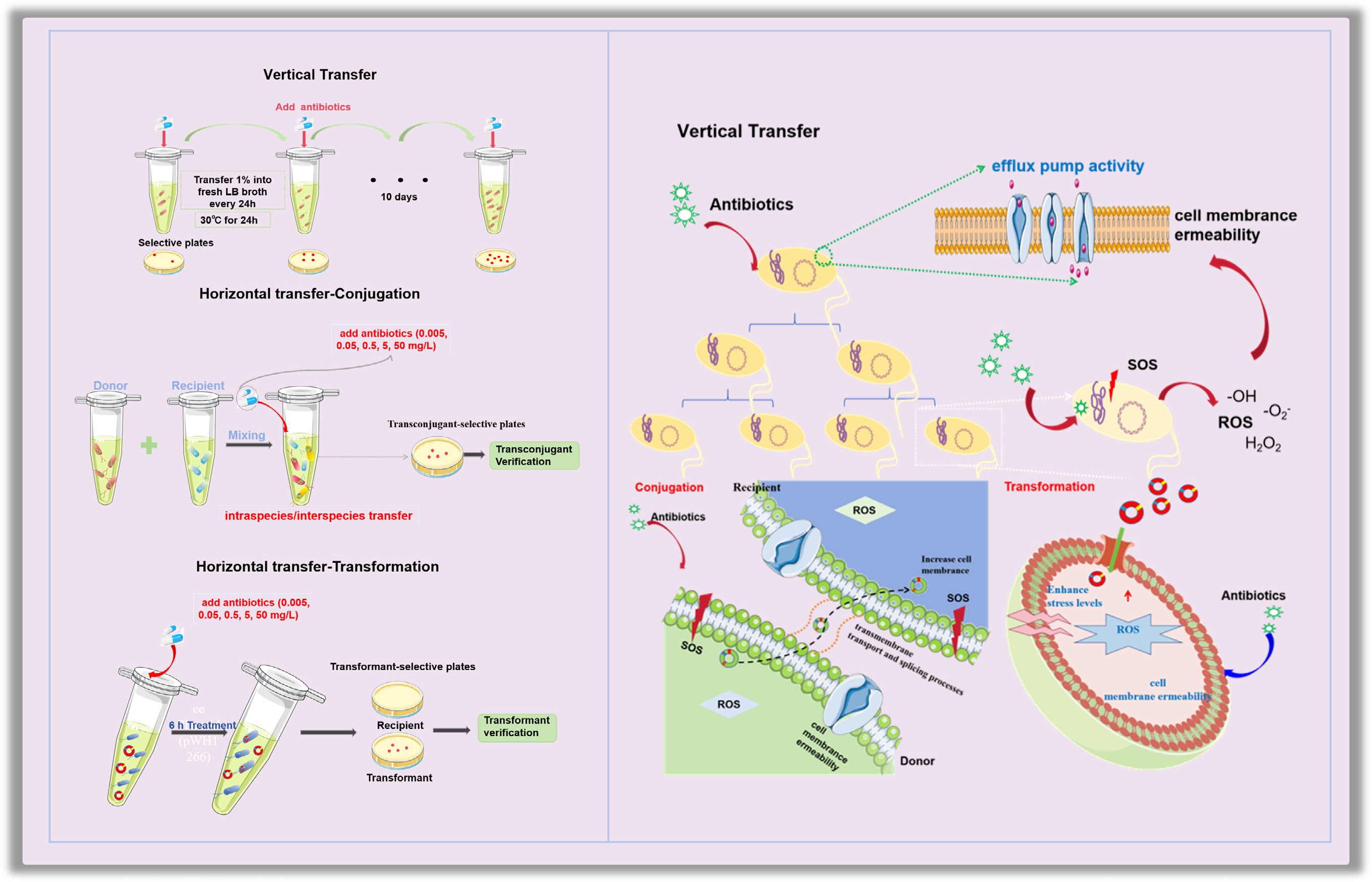

Antibiotic resistance is defined as the ability of microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, or viruses) to withstand or diminish the efficacy of antibiotics upon exposure[1,2]. Bacteria that exhibit antibiotic resistance are referred to as antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and harbor the corresponding antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Although antibiotic resistance is not a novel phenomenon, the current global dissemination of ARB and ARGs has escalated to unprecedented levels, raising serious ecological and public health concerns[3]. It is estimated that approximately 70% of hospital infections exhibit resistance to at least one antibiotic[4]. Recent studies have indicated that in 2019, antibiotic-resistant infections directly caused 1.27 million deaths and indirectly contributed to 4.95 million deaths, and an estimated 39 million people worldwide will die from antibiotic resistance between 2025 and 2050[5]. ARGs are transmitted in the environment by vertical gene transfer (VGT)[6] and horizontal gene transfer (HGT)[7]. VGT refers to the transfer of genes from a mother cell to daughter cells through bacterial reproduction[8]. VGT plays a stabilizing role in the succession and expansion of bacterial communities[9]. For HGT, three distinct pathways are involved: (i) conjugation, which facilitates the transfer of ARGs through conjugative bridges and aids in transferring nonresistant bacteria to ARB[10]; (ii) transformation, where competent bacteria take up extracellular DNA, a process identified in over 80 Gram-positive and Gram-negative species[11]; and (iii) transduction or bacteriophage-mediated ARG transfer[12,13]. Among these, conjugation remains the primary driver of horizontal ARG dissemination[14]. VGT plays a dominant role in shaping the composition of ARGs within prokaryotic communities, especially during the expansion of bacterial populations[15]. Resistance genes are efficiently passed on to their progeny through the process of cell division. In addition, there is a synergistic effect between vertical and horizontal transfer, contributing to the widespread dissemination of resistance genes[15].

Antibiotics are a class of chemicals that inhibit or kill microorganisms, primarily bacteria. They not only possess bactericidal action but also impact the adherence, transcription stability, and electron transfer of bacteria[16]. Antibiotics are classified into eight major categories, with the most common classes being β-lactams (e.g., penicillin), tetracyclines (e.g., tetracycline), and aminoglycosides (e.g., kanamycin)[17−20]. Statistical data show that in 2023, global antibiotic consumption reached 49.3 billion defined daily doses (DDD). It is estimated that by 2030, global antibiotic use will reach 75.1 billion DDD, with an increase of over 50% since 2016[21]. In 2023, the global antibiotic market size was approximately

${\$} $ ${\$} $ While antibiotics are traditionally considered the most direct selecting factor influencing the development of antibiotic resistance, their effects on VGT and HGT are controversial. For example, subinhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin and streptomycin have been shown to increase the mutation frequency in Streptococcus pneumoniae[46], and sulfadiazine can significantly enhance the VGT rate[15]. In contrast, tetracycline can inhibit bacterial growth and may limit VGT rates[15]. Regarding HGT, the occurrence of specific HGT events coincides with elevated antibiotic levels[47,48]. Moreover, antibiotics at subinhibitory levels can stimulate HGT of ARGs, whereas some studies have shown that acyclovir and biochar inhibit the horizontal transfer of ARGs through specific mechanisms[49,50]. Notably, current studies have focused on the short-term effects of antibiotics on the spread of ARGs, within several hours to several days. Considering that antibiotics persist in the environment[51], their long-term effects on the development of antibiotic resistance remain largely unknown.

In this study, we tried to fill the knowledge gap by establishing both the genetic evolution model and the HGT model under the exposure of typical antibiotics (i.e., tetracycline, ampicillin, streptomycin, and kanamycin) at concentrations ranging from environmentally relevant (0.005–0.5 mg/L) to subinhibitory levels (5–50 mg/L). For the genetic evolution model, three bacterial strains containing different ARGs were exposed to antibiotics for 10 consecutive days. For the HGT model, conjugation systems were established for both intra- and inter-species transfer using Escherichia coli MG1655 carrying the plasmid RP4 as the donor and E. coli HB101 and Salmonella enterica as the recipients. A transformation model was also established by exposing the free plasmid pWH1266 to the naturally competent Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. Bacterial reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, SOS response, cell membrane permeability, and gene expression levels of the relevant genes were measured under antibiotic exposure to unravel the underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, mathematical models were established to predict the long-term effects of antibiotics on the spread of antibiotic resistance.

-

The genetic system was established using E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid (resistant to the antibiotics tetracycline, ampicillin, and kanamycin), E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid (resistant to tetracycline and ampicillin), and E. coli HB101, which is inherently resistant to streptomycin. The conjugation system was established using E. coli MG1655 carrying the RP4 plasmid as the donor, and E. coli HB101 (streptomycin-resistant) and S. enterica as the recipients for intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative transfer, respectively. The transformation system was established by introducing the foreign plasmid pWH1266 into naturally competent A. baylyi ADP1. All bacterial cultivation conditions are provided in Supplementary Text S1.

VGT model

-

A genetic system was constructed under typical antibiotic exposure (i.e., 20 mg/L tetracycline, 100 mg/L ampicillin sodium, 50 mg/L streptomycin, and 40 mg/L kanamycin). Three selected bacterial strains were cultured overnight to achieve a 108 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL concentration. The bacteria were then exposed to their corresponding antibiotics (i.e., antibiotics to which they exhibit resistance) and evolved aerobically for consecutive 10 d. In detail, resistant bacteria that had been grown overnight were inoculated with 30 μL into 2.97 mL Luria–Bertani (LB) broth containing the corresponding antibiotic. Every 24 h, 30 μL of bacteria was transferred to fresh LB broth with the same antibiotic concentration and incubated for another 24 h. This process was repeated for 10 d. The control group was set as a bacterial culture without any antibiotic exposure. CFU counts on agar plates were further analyzed to validate the stable genetic transmission of the ARGs.

Conjugative transfer model

-

Two conjugation systems were constructed by employing E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid as the donor, E. coli HB101 as the recipient (for intrageneric conjugative transfer), and S. enterica as the recipient (for intergeneric conjugative transfer). In both the intrageneric and intergeneric conjugation models, the donor and recipient bacteria were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with a concentration of 108 CFU/mL for each. Conjugation was performed in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-based system (pH = 7.2) with a total volume of 1 mL. Various classes of antibiotics at a range of concentrations, including subinhibitory levels relevant to environmental conditions, were added separately to the conjugation system. The final concentrations of tetracycline, kanamycin, ampicillin, and streptomycin were set at 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 5, and 50 mg/L. After 8 h of incubation at 25 °C without shaking, 50 μL of the mixture was spread onto LB selective agar plates containing 20 mg/L tetracycline, 100 mg/L ampicillin, 50 mg/L streptomycin, and 40 mg/L kanamycin to screen for transconjugants. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates. Conjugative transfer rates were calculated by dividing the number of transconjugant colonies by the recipient colony count. As no nutrients were provided during mating, the growth of the donor, recipient, and transconjugants was excluded. Additionally, the plasmids used in the conjugation experiments were large, and the recipient strains were not competent cells; thus, the possibility of a bacterial transformation process could be eliminated[11].

Transformation model

-

A transformation system was established by applying the naturally competent bacterial strain A. baylyi ADP1 and the free pWH1266 plasmid[52]. In detail, after overnight culture of A. baylyi ADP1 at 30 °C in LB broth, a 1% cell suspension was transferred to fresh LB medium and incubated in a shaking incubator until the exponential growth phase, with an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.2. Cells were then collected by centrifugation, washed twice with PBS buffer to remove any residual LB, and resuspended. Freshly prepared pWH1266 plasmids were suspended in a 2.5 mM Tris-HCl elution buffer and added to the cell suspension, achieving a final plasmid concentration of 1 ng/µL (equivalent to 1.04 × 108 copies/µL). Sodium acetate was included as an energy source to establish the transformation system. The mixture was then exposed to four antibiotics at concentrations of 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 5, and 50 mg/L. After thorough mixing, the transformation system was incubated at room temperature for 6 h. The total number of cells was cultured on nonselective agar, while the transformation ratio was determined by plating on selective agar containing antibiotics to count the number of transformants. The transformation ratio was calculated as the number of transformants divided by the total number of cells. Each experiment was conducted with three biological replicates.

ROS and cell membrane permeability detection

-

Upon antibiotic exposure, bacterial generation of ROS and changes in cell membrane permeability were assessed. In detail, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) (final concentration of 10 μM) dye was used to detect intracellular ROS, whereas propidium iodide (PI) (final concentration of 2 μg/mL) dye was used to assess enhanced membrane permeability[53,54]. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a multifunctional microplate reader (Synergy H1M, BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA), with the fluorescence intensity values representing the levels of ROS and the extent of membrane permeability. Each experiment was conducted with three biological replicates (details are provided in Supplementary Text S2).

Adenosine triphosphate detection

-

The intracellular levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in donor and recipient microbial populations were quantified using a chemiluminescence-based method (BacTiter-Lumi™ ATP assay kit, Beyotime Biotech Inc.)[55,56]. The relative ATP content was calculated from chemiluminescence signals, normalized to untreated controls. All experiments were performed with three biological replicates. Details are provided in Supplementary Text S3.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction technique

-

Expression levels of genes related to antibiotic resistance transfer were assessed using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Initially, three systems were established as previously described and exposed to antibiotics. Total RNA was extracted from bacterial samples using the RNeasy MiniKit (QIAGEN®, Germany) with an additional bead-beating step included in the protocol for cell lysis. This was followed by cDNA synthesis using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit, which includes a gDNA Eraser (Takara) for determining mRNA gene expression levels. RT-qPCR was performed using a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Expressions of six typical genes (i.e., oxyR, soxR, recA, tolC, ompA, and ompC), which are involved in stress responses and membrane permeability, were analyzed under antibiotic exposure. Primer sequences and reaction conditions are provided in Supplementary Text S4 and Supplementary Table S1.

Mathematical modeling and prediction of the long-term cumulative effects of VGT and HGT

-

Two different mathematical models were used to simulate and predict the long-term effects of antibiotics on the VGT and HGT of ARGs. The first model describes the dynamic changes in plasmid-carrying bacteria (carrying ARGs) and plasmid-free bacteria (Eqs [1] and [2], respectively), which reflects the genetic evolution of ARB. The second model is used to describe the dynamic transfer in naturally competent bacteria, transformants, and free plasmids (Eqs [3]−[5], respectively). Long-term dynamic changes in the horizontal transfer of ARGs can be predicted. Each model contains two key variables, which are implicitly calibrated using an optimization function (details are provided in Supplementary Text S5).

$ \mathrm{M}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{l}\,\mathrm{I}\left\{\begin{array}{l}& \dfrac{d{M}_{0}}{dt}={r}_{0}{M}_{0}\left(1-\dfrac{{M}_{0}+{M}_{1}}{K}\right)-{d}_{0}{M}_{0}+\alpha {M}_{1}-\beta {M}_{0}{M}_{1}\quad\quad\left(1\right) \\ &\dfrac{d{M}_{1}}{dt}={r}_{1}{M}_{1}\left(1-\dfrac{{M}_{0}+{M}_{1}}{K}\right)-{d}_{1}{M}_{1}-\alpha {M}_{1}+\beta {M}_{0}{M}_{1}\quad\quad\left(2\right)\end{array}\right. $ Model I is based on the population dynamics of plasmid-carrying bacteria (ARB) and plasmid-free bacteria (antibiotic-sensitive bacteria). The two differential equations describe the changes in the population sizes of the two bacterial types. Equation (1) describes the growth, natural death, plasmid loss, and conjugation of plasmid-bearing ARB (M0). Equation (2) describes the growth, natural death, plasmid acquisition, and conjugation of plasmid-free bacteria (M1). All variables and parameters involved in Model I are defined in Table 1.

Table 1. Variables used in Model I (VGT model)

Symbol Description Model variables M0 Count of E. coli MG1655 M1 Count of E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid t Time (h) Model parameters r0/r1 Growth rate of M0 or M1 d0/d1 Death rate of M0 or M1 K Environmental carrying capacity, set as 108 α Probability of plasmid loss β Conjugative transfer ratio ${\rm{ Model\; II}} \left\{\begin{array}{l}& \dfrac{d{A}_{0}}{dt}={r}_{0}{A}_{0}\left(1-\dfrac{{A}_{0}+{A}_{1}}{K}\right)-{d}_{0}{A}_{0}-\mu P{A}_{0}\quad\quad\left(3\right) \\ & \dfrac{d{A}_{1}}{dt}={r}_{1}{A}_{1}\left(1-\dfrac{{A}_{0}+{A}_{1}}{K}\right)-{d}_{1}{A}_{1}+\mu P{A}_{0}\quad\quad\left(4\right)\\ & \dfrac{dP}{dt}=-\mu P{A}_{0}+{d}_{1}{A}_{1}\lambda -\theta P\quad\quad\left(5\right) \end{array}\right. $ Model II is based on the population dynamics of wild-type bacteria (A0), transformants (A1), and free plasmids (P). The equations describe the temporal variations in the abundance of wild-type bacteria, transformed bacteria, and free plasmids. Equations (3) and (4) describe the growth, death, and plasmid-mediated transformation processes of A0 and A1 bacteria, respectively, whereas Eq (5) considers the bacterial uptake of plasmids, the plasmids released during bacterial lysis, and the intrinsic degradation of plasmids. All variables and parameters involved in Model II are defined in Table 2.

Table 2. Variables used in Model II (transformation model)

Symbol Description Model variables A0 Count of wild-type A. baylyi A1 Count of transformants, A. baylyi with the pWH1266 plasmid P Number of free plasmids t Time (h) Model parameters r0/r1 Growth rate of A0 or A1 d0/d1 Death rate of A0 or A1 K Environmental carrying capacity, set as 108 μ Transformation ratio λ Plasmid copy number in the transformant θ Decay rate of free plasmids in the environment Statistical analyses

-

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate biological replicates. Significance was analyzed using the Benjamini–Hochberg-corrected independent-sample t-test, with the corrected p-value denoted as padj[57]. A value of padj < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

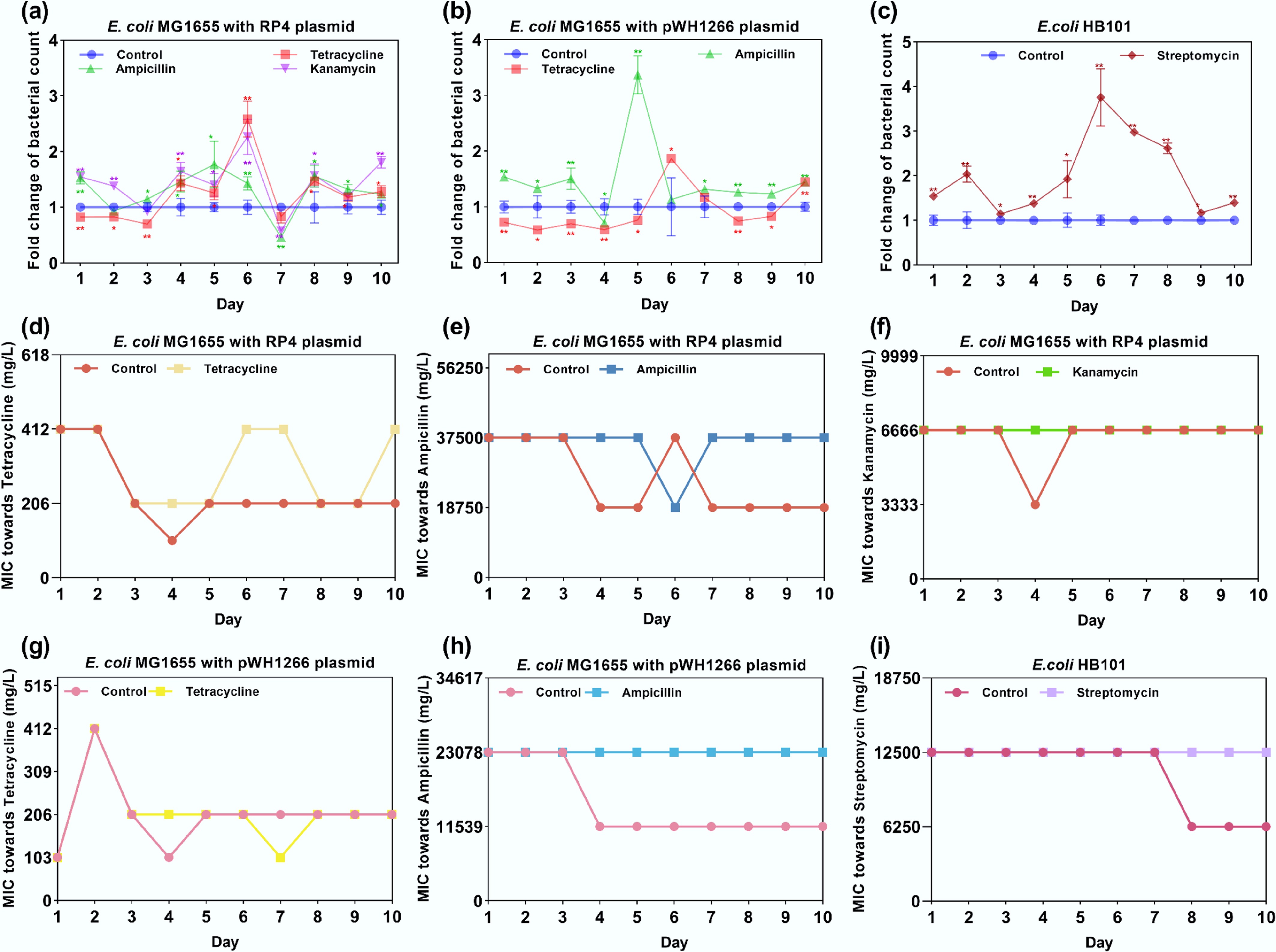

To assess the genetic stability of bacterial resistance genes, we constructed a vertical transmission system through a 10-d serial passage experiment to evaluate changes in antibiotic susceptibility and investigate whether subsequent generations can stably inherit bacterial resistance.

The results showed that kanamycin, ampicillin, and streptomycin could significantly increase the number of ARB during bacterial genetic processes (Fig. 1a–c). Under all four antibiotic treatments, the abundance of resistant bacteria exhibited daily fluctuations, peaking on Day 6 under treatment conditions, except for the two ampicillin-treated groups. E. coli HB101 under streptomycin exposure showed the most pronounced change (a 3.76-fold increase compared with the control group) (Fig. 1a–c). Although resistant clones accumulated during the mid-phase of treatment, their overall fluctuations in abundance were limited. In contrast, tetracycline exhibited distinct behaviors. Under tetracycline exposure, in contrast to the other treatment groups, resistant bacteria exhibited slower growth; their abundance remained below that of the control during the first 3 d of passage, then began to rise from Day 5 onward and reached a peak on Day 6. This was also shown in the OD600 variation (Supplementary Fig. S1). Additionally, it was noted that the growth of E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid and E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid in the tetracycline-treated group was slower than that in the other antibiotic-treated groups (Supplementary Fig. S2). This difference may be related to tetracycline's reliance on efflux pumps to actively expel the drug from the cell, consuming a large amount of energy (such as ATP). Therefore, even when carrying resistance plasmids, bacterial growth remains slower under tetracycline exposure. Additionally, ampicillin, kanamycin, and streptomycin are bactericidal, rapidly killing sensitive bacteria and promoting the selection of resistant strains. In contrast, tetracycline is bacteriostatic, primarily inhibiting protein synthesis to delay cell proliferation, resulting in more pronounced growth inhibition[58−61].

Figure 1.

Fold change in bacterial counts and MIC variation under exposure to antibiotics. (a) Fold change in bacterial counts for E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid. (b) Fold change in bacterial counts for E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid. (c) Fold change in bacterial counts for E. coli HB101. (d) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid treated with tetracycline. (e) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid treated with ampicillin. (f) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid treated with kanamycin. (g) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid treated with tetracycline. (h) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid treated with ampicillin. (i) MIC variations of E. coli HB101 treated with streptomycin. Statistical significance between the antibiotic-treated and control groups was analyzed using an independent sample t-test and corrected by the Benjamini–Hochberg method, * padj < 0.05 and ** padj < 0.01. Data represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

Under exposure to antibiotics, the bacterial strain initially harbors the corresponding antibiotic resistance, and bacterial resistance can be reliably inferred from bacterial count measurements. This was further confirmed by detecting the MIC (Fig. 1d–i). Under antibiotic selection, MIC values for all strains remained similar to those on Day 0 and remained stable overall throughout serial passage; in contrast, under antibiotic-free conditions, MICs generally decreased by approximately twofold (Fig. 1d–i). Tetracycline exhibited greater variability than the other treatments; under tetracycline exposure, E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid failed to maintain stable resistance across multiple days (Fig. 1d), whereas tetracycline-treated E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid showed a lower MIC on Day 7 than that of the control (Fig. 1g). We further detected the tetracycline concentration by applying high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)[62] (details are shown in Supplementary Text S6). The HPLC results revealed that the tetracycline concentration in the bacteria-containing treatment (17.98 mg/L) was markedly lower than that in the bacteria-free control (19.97 mg/L), suggesting that the bacterial strain is capable of degrading tetracycline (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S3). Overall, the dominant effect of environmentally relevant selection pressures on resistance is the maintenance of a stable baseline.

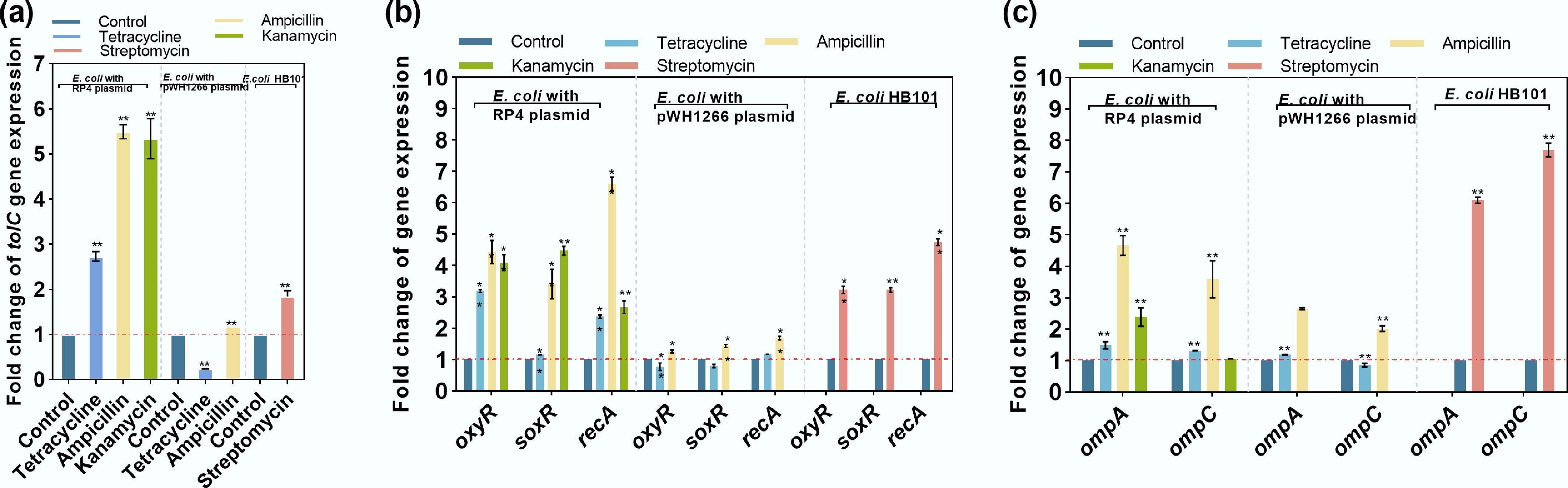

Antibiotic exposure enhanced the stability of resistance and further promoted the emergence of new resistant phenotypes, as confirmed by the MIC measurements. The results showed that E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 or pWH1266 plasmids exhibited a gradual increase in streptomycin resistance under antibiotic pressure (the MIC increased by approximately two- to fourfold), with the tetracycline-treated group displaying the earliest and most pronounced enhancement (Fig. 2a, b). Accordingly, E. coli HB101 treated with streptomycin exhibited higher MIC values against other antibiotics compared with the control group, indicating that streptomycin exposure could enhance the resistance of E. coli HB101 to tetracycline, ampicillin, and kanamycin (Fig. 2c–e). Furthermore, an examination of susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in the three strains revealed that the MIC values remained largely stable between the control and treated groups, except for the emergence of a new resistant phenotype in tetracycline-treated E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 or pWH1266 plasmids (Fig. 2f–h). In summary, environmentally relevant antibiotic concentrations may stabilize existing resistance and promote the development of new cross-resistance, thereby increasing the risk of resistance disseminating.

Figure 2.

(a) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid treated with streptomycin. (b) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid treated with streptomycin. (c) MIC variations of E. coli HB101 treated with tetracycline. (d) MIC variations of E. coli HB101 treated with tetracycline. (e) MIC variations of E. coli HB101 treated with ampicillin. (f) MIC variations of E. coli HB101 treated with kanamycin. (g) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid treated with ciprofloxacin. (h) MIC variations of E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid treated with ciprofloxacin.

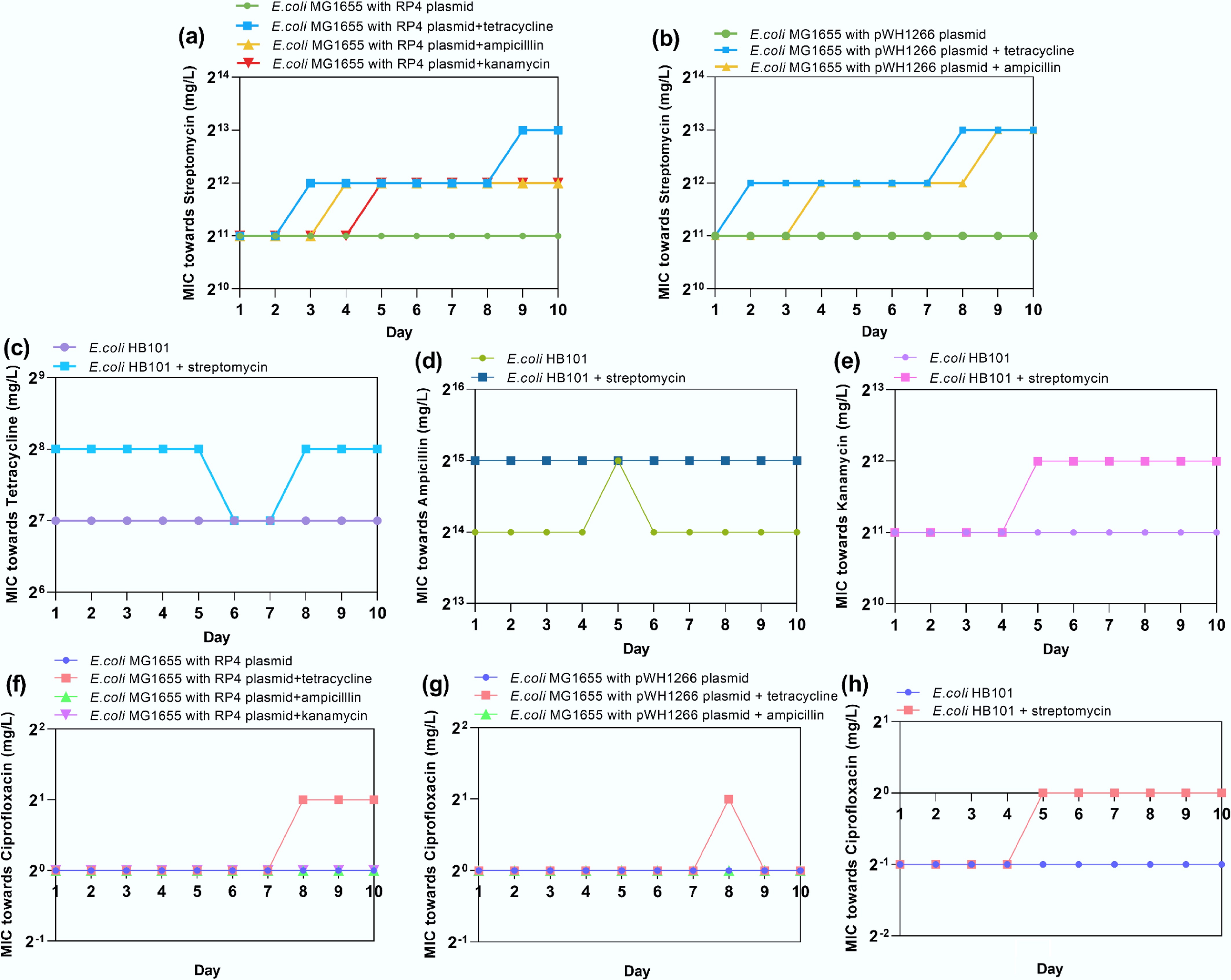

In the bacterial metabolism process, ROS are generated as byproducts. Excessive ROS production induces detoxification mechanisms, triggering oxidative stress responses to counteract cellular damage[63]. ROS-mediated oxidative stress has been recognized as a common antimicrobial mechanism of antibiotics[64,65]. Moreover, the activation of efflux pumps is a crucial resistance mechanism, enabling bacteria to regulate their internal environment by expelling toxic substances such as antibiotics[66,67]. Evidence suggests that ROS can target membrane components, inducing structural damage that increases membrane permeability[68,69]. In this study, we hypothesized that the persistence of ARGs under antibiotic exposure may be mechanistically linked to the overproduction of ROS, SOS-mediated oxidative stress responses, efflux pump activity, and compromised membrane integrity. To test the hypothesis, RT-qPCR was used to investigate the regulation of key genes in response to antibiotic exposure.

It was shown that for the efflux pump-related gene tolC, ampicillin, kanamycin, and streptomycin could upregulate its expression by up to 5.53-, 5.85-, and 1.95-fold (** padj< 0.01), respectively, whereas tetracycline decreased the expression of tolC in E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid (0.35-fold compared with the untreated control) (Fig. 3a). Regarding genes encoding oxidative stress regulators (oxyR and soxR[70]) and SOS response regulators (recA), most increased significantly under exposure to antibiotics, with the highest fold changes being 4.43-, 4.47-, and 6.67-, respectively (Fig. 3b). However, tetracycline treatment did not induce oxidative stress in E. coli MG1655 with the pWH1266 plasmid, and it even reduced ROS release (with a significant downregulated expression of oxyR by 0.77-fold). Similarly, upregulations of membrane porin genes (ompA and ompC) were observed under exposure to ampicillin, kanamycin, and streptomycin, with the highest fold changes of 6.71- and 7.71-fold, respectively. Tetracycline exhibited limited effects on the regulation of membrane porin-related genes (0.86-fold to 1.49-fold) (Fig. 3c). The expression levels of efflux pump, oxidative stress, and membrane porin-related genes corresponded to the phenotypic phenomenon that antibiotics can promote the stable inheritance of ARGs.

Figure 3.

Changes in the expression of key genes under exposure to antibiotics. (a) Efflux pump-related gene tolC. (b) Oxidative stress-related genes (oxyR and soxR) and an SOS response-related gene (recA). (c) Membrane porin-related genes ompA and ompC. Statistical significance between the antibiotic-treated groups and controls is indicated by * padj < 0.05 and ** padj < 0.01.

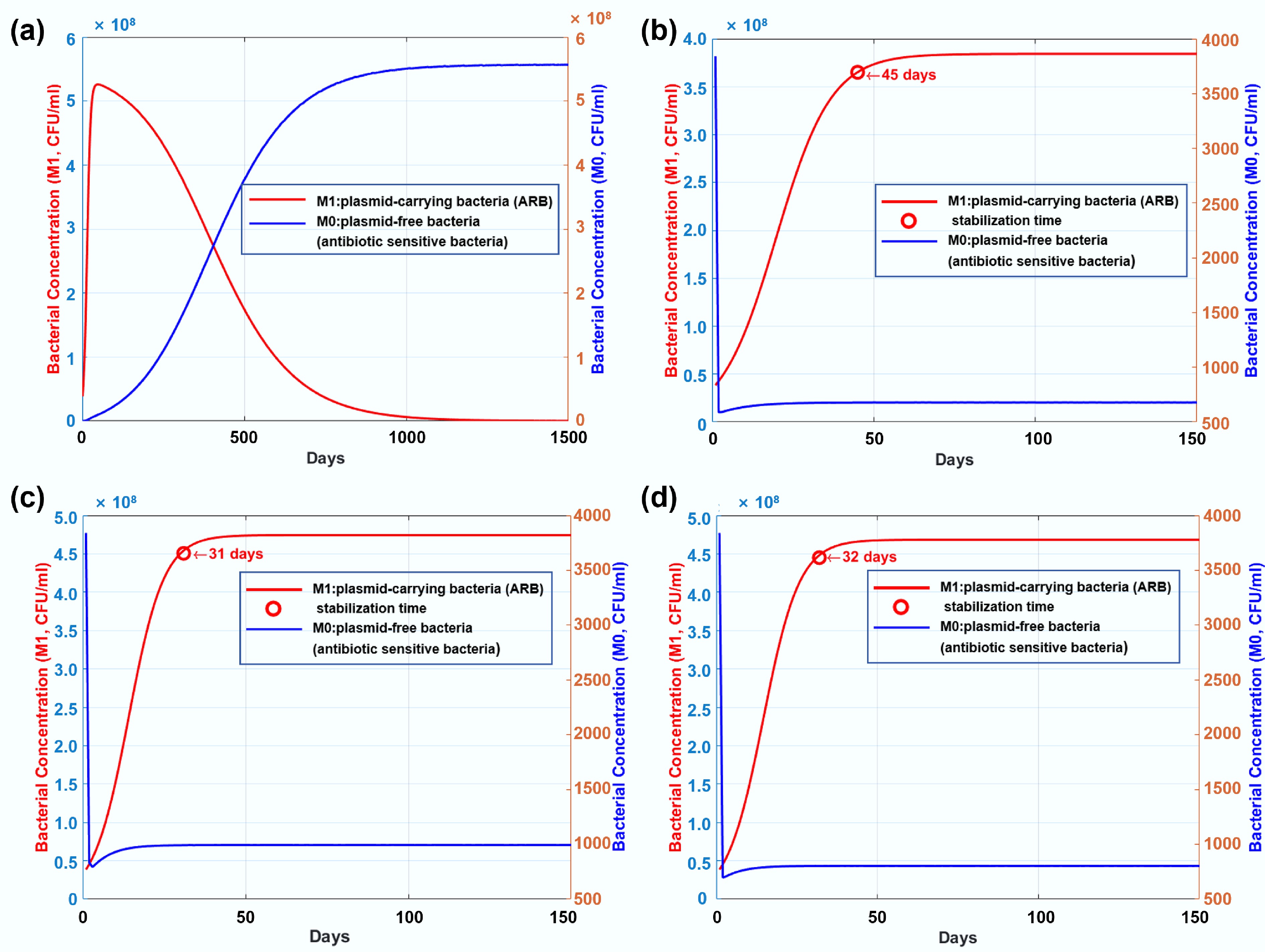

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the long-term dynamic changes in the ARB population under antibiotic pressure, this study constructed an ordinary differential equation (ODE) model based on the number of plasmid-carrying bacteria (ARB) and plasmid-free bacteria (antibiotic-sensitive bacteria). The model simulates and predicts the long-term genetic changes of these bacteria under different antibiotic environments (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

By utilizing experimental data from the continuous 10-d evolution experiments of the control group (no antibiotic treatment) and the experimental group (exposed to antibiotics), we calibrated two key parameters in the ODE model: the probability of plasmid loss and the probability of potential gene conjugation transfer. Upon solving the differential equations, we observed that in the control group without antibiotics, the number of plasmid-carrying bacteria (ARB) first increased and then decreased over time. In contrast, plasmid-free bacterial populations (antibiotic-sensitive bacteria) demonstrated sustained growth, eventually stabilizing as the dominant subpopulation within the system (Fig. 4a). This phenomenon likely arises from elimination of the metabolic burden imposed by plasmid maintenance, enabling plasmid-free strains to achieve higher growth rates in the absence of antibiotics[71]. In the experimental groups exposed to antibiotics, the changes in the population size of plasmid-carrying bacteria and plasmid-free bacteria during genetic processes showed significant differences compared with the control group. Plasmid-carrying bacterial populations exhibited a progressive increase followed by stabilization, whereas plasmid-free bacteria rapidly decreased under the effect of the antibiotics and approached extinction. (Fig. 4b–d). In the tetracycline-treated group, a longer time was required to achieve a stable bacterial number, namely 45 d, whereas the times for the kanamycin- and ampicillin-treated groups were 31 and 32 d, respectively. The mathematical model further confirmed that, under antibiotic exposure, plasmid-carrying bacteria can maintain stable genetic inheritance, whereas plasmids harboring ARGs can be easily lost without antibiotic exposure.

Figure 4.

(a) Long-term genetic dynamics of plasmid-carrying bacteria (ARB) and plasmid-free bacteria (antibiotic-sensitive bacteria) in the control group without any antibiotic dosage. (b) Long-term genetic dynamics of resistant and susceptible bacterial strains under exposure to tetracycline. (c) Long-term genetic dynamics of resistant and susceptible bacterial strains under exposure to kanamycin. (d) Long-term genetic dynamics of resistant and susceptible bacterial strains under exposure to ampicillin.

Antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can promote both intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative transfer of ARGs

-

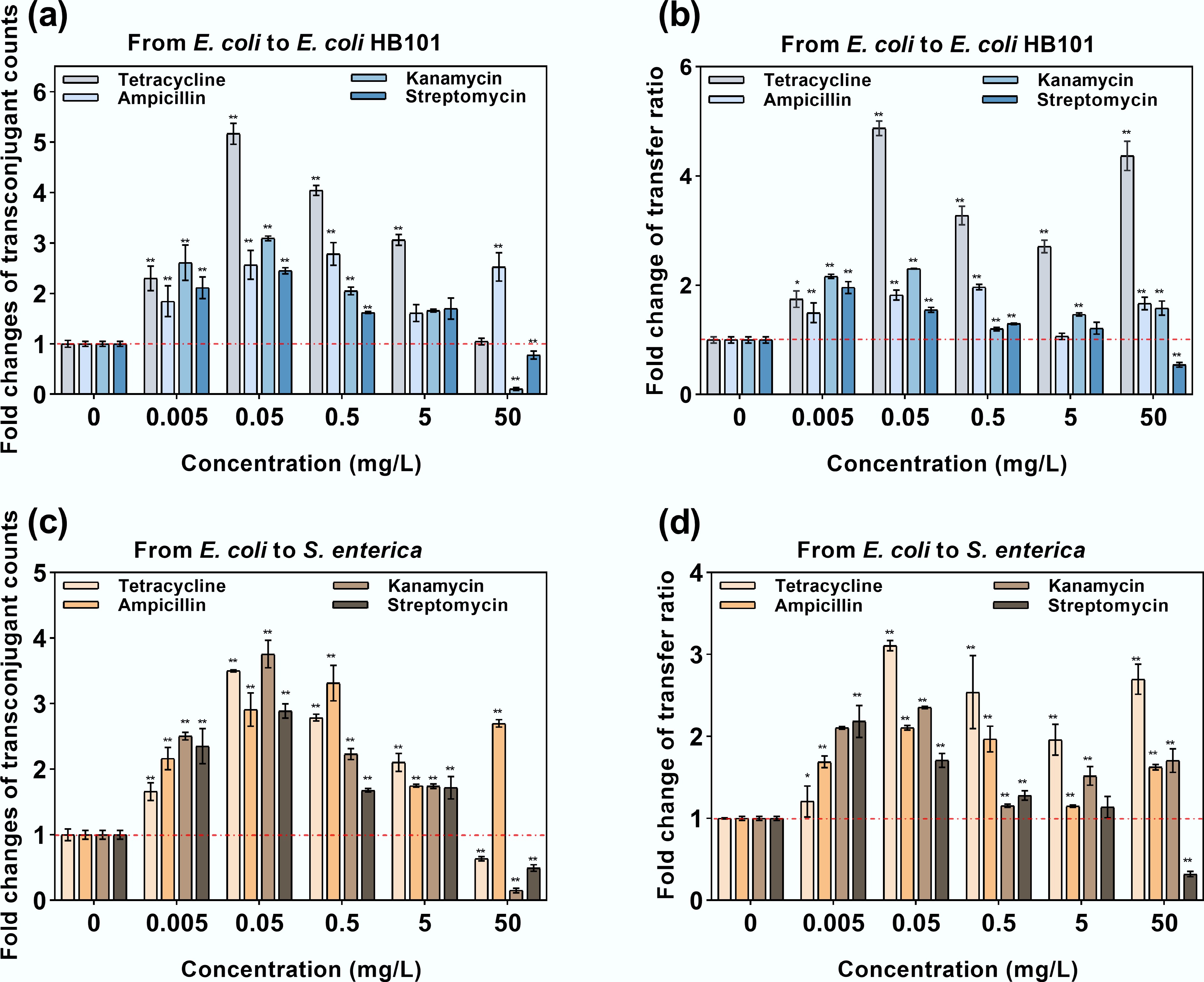

To better understand how ARGs are transferred horizontally in the presence of antibiotics, both intrageneric and intergeneric conjugation systems were established. Low doses of antibiotics (0.005–5 mg/L) significantly increased transconjugant counts for both intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative transfer, with increases of 1.61- to 5.17-fold (** padj < 0.01). This increase also corresponded with a rise in the RP4 plasmid-mediated conjugative transfer ratio, which were elevated 1.15- to 4.88-fold (** padj < 0.01) (Fig. 5). Notably, tetracycline, kanamycin, and streptomycin at a concentration of 0.05 mg/L (environmentally relevant)[72,73] showed the highest transconjugant number and the highest transfer ratio, whereas ampicillin reached its peak effect at 0.5 mg/L (environmentally relevant)[74]. In contrast, when exposed to antibiotics at a concentration of 50 mg/L, the conjugation system exhibited different patterns. Only the ampicillin-dosed group showed a significant increase in transconjugant number compared with the untreated control; the transconjugant number in other antibiotic-dosed groups decreased. However, the fold change in the transfer ratio still increased because of the decrease in the recipient number (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 5.

Intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative transfer under exposure to antibiotics. (a) Fold change in transconjugants under intrageneric conjugative transfer. (b) Fold change in the transfer ratio under intrageneric conjugative transfer. (c) Fold change in transconjugants under intergeneric conjugative transfer. (d) Fold change in the transfer ratio under intergenic conjugative transfer. Statistical significance between the antibiotic-treated and control groups was analyzed using an independent sample t-test and corrected by the Benjamini–Hochberg method, * padj < 0.05 and ** padj < 0.01. Data represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates.

The effectiveness of the transconjugants was also validated by extracting the RP4 plasmid from randomly selected transconjugants on selective agar plates, followed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and gel electrophoresis. Distinct single bands corresponding to the tetA and blaTEM genes confirmed successful intrageneric and intergeneric RP4 plasmid transfer from the donor to recipient strains (Supplementary Fig. S5).

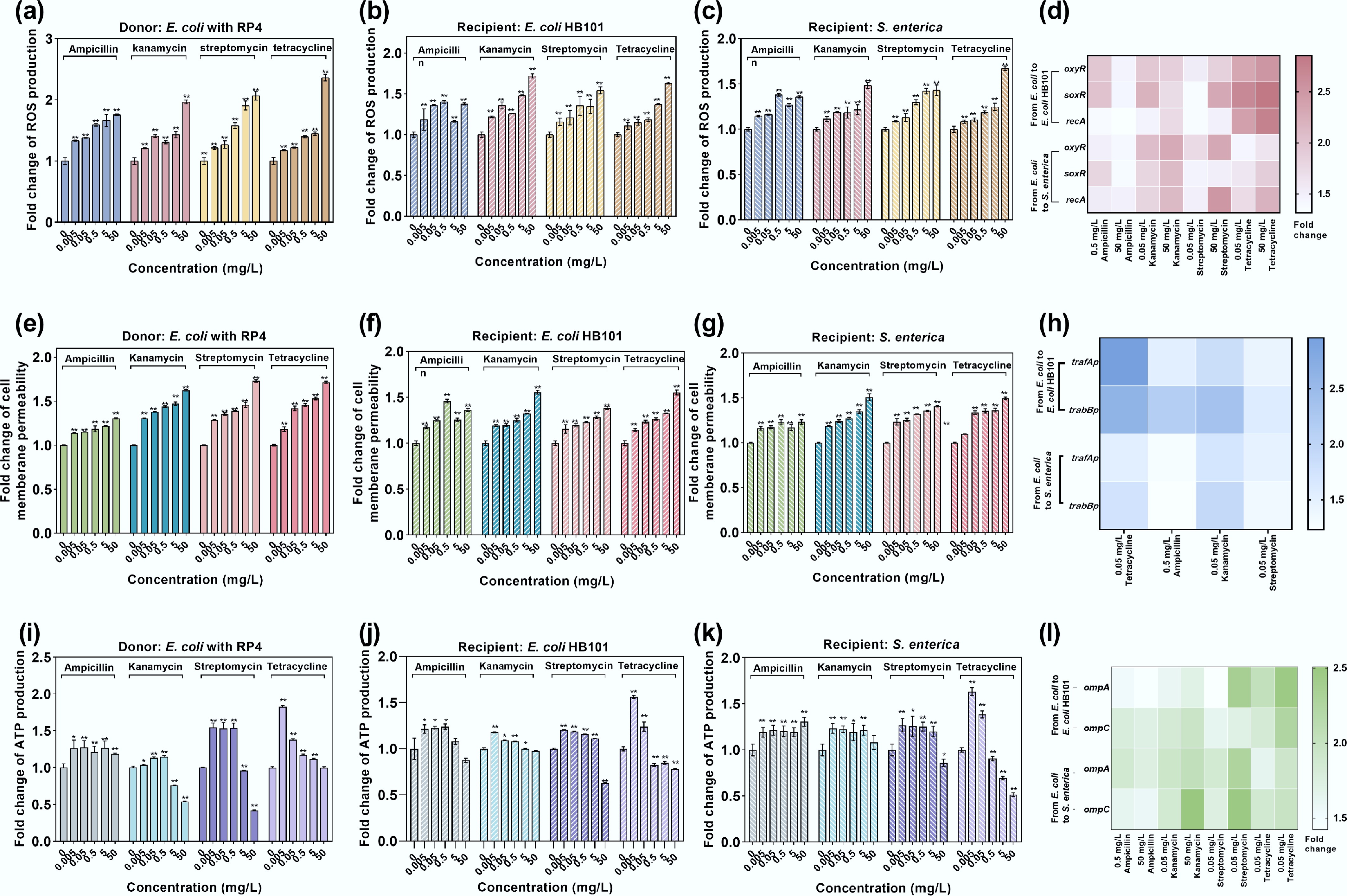

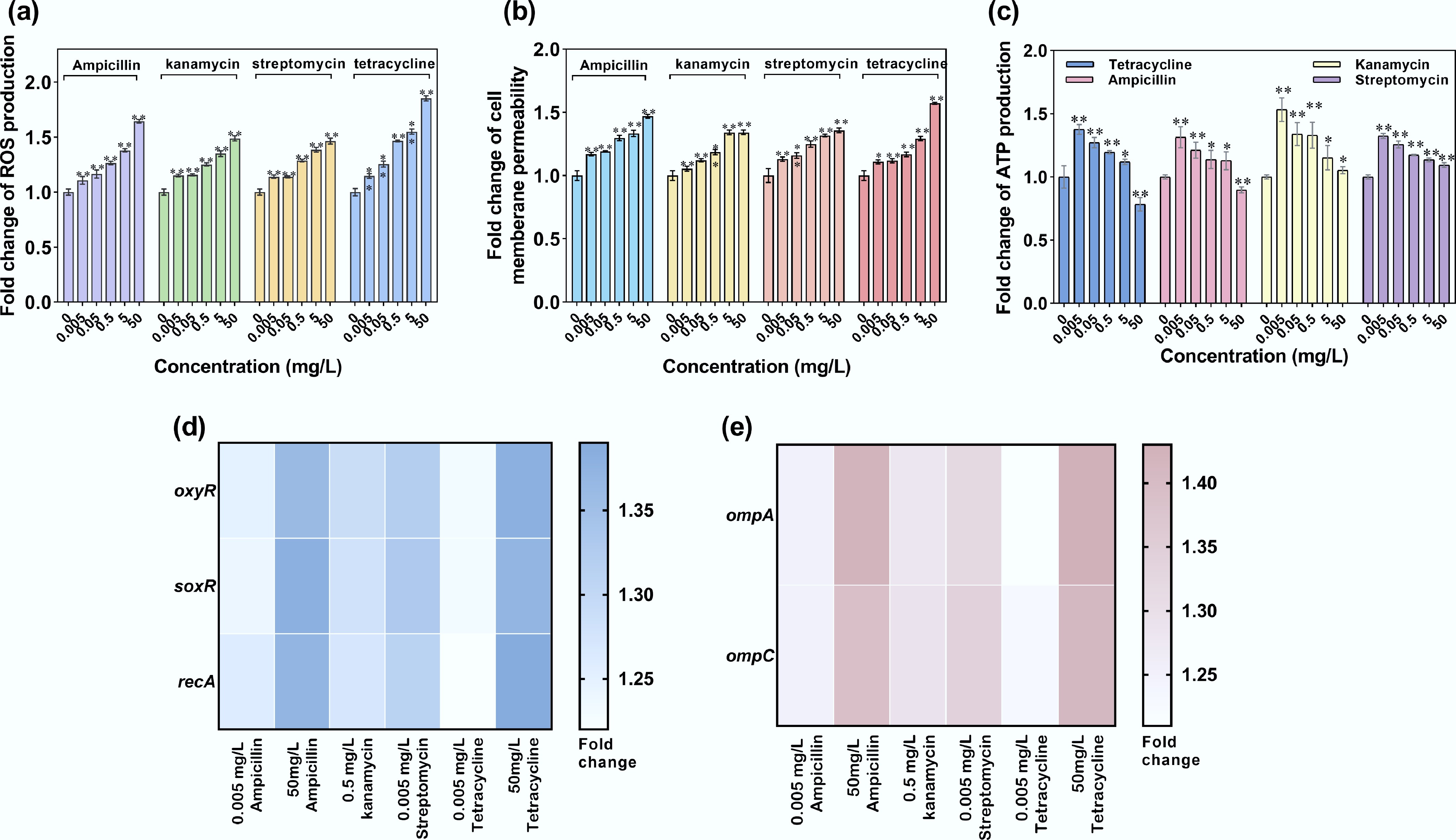

The underlying mechanisms were further unraveled by detecting bacterial ROS production, cell membrane permeability, and ATP production. The expression of genes related to bacterial oxidative stress, cell membrane, and conjugative regulation were examined.

Under exposure to antibiotics, ROS production in both the donor and recipient bacteria, as measured by fluorescence, significantly increased by 1.21–2.38-fold (padj < 0.01, Fig. 6a–c). Dose-dependent ROS levels were observed in the groups treated with kanamycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline. Notably, ampicillin at 0.5 mg/L resulted in the highest ROS production in the recipient bacteria, which corresponded well with the highest transconjugant number (Fig. 5a). Correspondingly, ROS regulatory genes (oxyR and soxR) and the SOS response marker gene (recA) were also upregulated significantly (p < 0.01, Fig. 6d). Specifically, 0.5 mg/L of ampicillin also exhibited higher ROS-related gene regulation compared with 50 mg/L ampicillin. For cell membrane permeability, which was detected by PI dye staining, both the donor and recipient bacteria showed elevated permeability levels, with 1.13–1.73-fold enhancement (padj < 0.01, Fig. 6e–g). Dose-dependent ROS levels were also observed in the kanamycin-, streptomycin-, and tetracycline-dosed groups, whereas ampicillin at 0.5 mg/L showed the highest increment. The expression levels of key genes related to the cell membrane, ompA and ompC, increased 1.42–2.51-fold and 1.58–2.21-fold, respectively, under exposure to antibiotics except ampicillin (p < 0.01, Fig. 6h), which was consistent with the changes in the conjugative transfer ratio. At high antibiotic doses, the expression of ompA and ompC genes was higher than that at lower doses, aligning with the changes in ROS production and cell membrane permeability. High-dose antibiotics may severely damage the cell membrane and inhibit plasmid transfer, leading to a significant decrease in the number of transconjugants (Fig. 5a, c).

Figure 6.

Bacterial ROS production, cell membrane permeability, and ATP production under the exposure to antibiotics in conjugative systems. (a) ROS production in donor E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid. (b) ROS production in the intraspecies recipient E. coli HB101. (c) ROS production in the interspecies recipient bacteria S. enterica. (d) Fold changes in the expression of key oxidative stress-related genes in intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative systems. (e) Fold change in cell membrane permeability in donor E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid. (f) Fold change in cell membrane permeability in the intraspecies recipient E. coli HB101. (g) Fold change in cell membrane permeability of interspecies recipient S. enterica. (h) Fold change in the expression of key membrane porin-related genes in intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative systems. (i) Fold change in ATP production in donor E. coli MG1655 with the RP4 plasmid. (j) Fold change in ATP production in the intraspecies recipient E. coli HB101. (k) Fold change in ATP production in the interspecies recipient S. enterica. (l) Fold changes in the expression of conjugative regulation genes in intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative systems. Statistical significance between the antibiotic-treated and control groups was analyzed using an independent sample t-test and corrected by the Benjamini–Hochberg method, * padj < 0.05 and ** padj < 0.01. Data represent the mean ± SD of biological triplicates.

ATP, as an essential energy molecule for cells, provides the necessary energy for DNA translocation across membranes[75]. ROS can induce the release of ATP from cells[76]. The results showed that exposure to low-dose antibiotics (0.005–0.5 mg/L) significantly elevated ATP levels in the donor bacteria, with a 1.13- to 1.56-fold increase compared with the untreated control (padj < 0.01, Fig. 6i). ATP levels in the recipient bacteria significantly increased in the 0.005–0.05 mg/L concentration range of antibiotics (padj < 0.01, Fig. 6j, k). The elevated ATP level indicates that more energy is available during the conjugative transfer process[71,77,78]. Conversely, higher antibiotic doses (excluding ampicillin) reduced ATP levels by 25%–58% in the donor and recipient cells. This decrease may result from the excessive release of ROS, which reduces viable cell numbers and further decreases the transconjugant number.

Conjugation efficiency in plasmids is critically regulated by plasmid-borne genes governing replication, partition, and mating pair formation[79]. Focusing on the RP4 plasmid, key factors influencing conjugation include the genes responsible for DNA transfer, replication, and transmembrane transport[80]. Specifically, trafAp (regulating transmembrane translocation) and trabBp (modulating conjugation dynamics) directly orchestrate RP4-mediated conjugative transfer. In this study, antibiotic concentrations corresponding to the highest conjugation transfer ratios were selected for testing the expression of trafAp and trabBp genes. It was shown that compared with the control group, the expression levels of trafAp and trabBp genes significantly increased under both intrageneric and intergeneric conjugative transfer systems by 1.42–2.95-fold and 1.23–2.61-fold, respectively (p < 0.01, Fig. 6i). Among the antibiotics, 0.05 mg/L of tetracycline resulted in the highest upregulation of intrageneric conjugation regulation genes, whereas 0.05 mg/L of kanamycin resulted in the highest upregulation of intergeneric conjugation genes. These findings align with the changes in the number of transconjugants (Fig. 5a, c), which were also likely attributable to antibiotic-induced alterations in recipient cells' viability and population dynamics.

Antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can elevate bacterial transformation of ARGs

-

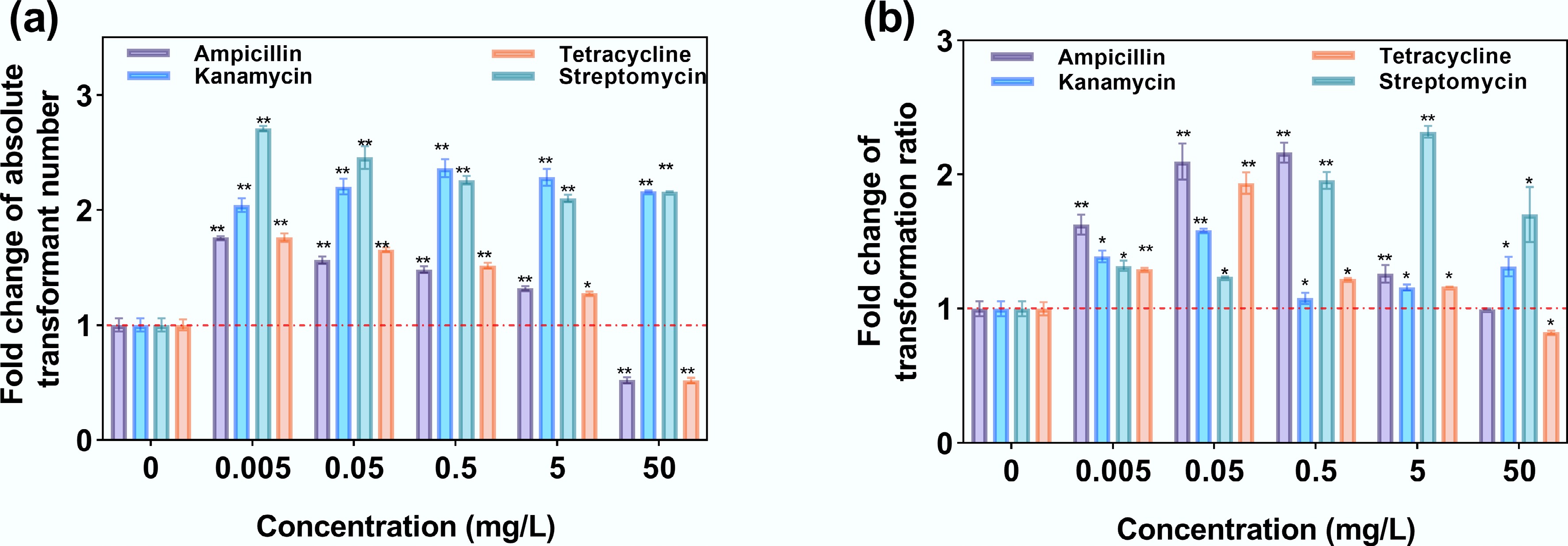

A transformation system was established to further assess antibiotic-driven HGT using the naturally competent bacterium A. baylyi ADP1 and the free plasmid pWH1266, which encodes resistance to tetracycline and ampicillin. After successful transformation, A. baylyi ADP1 carrying the pWH1266 plasmid (transformants) were obtained and quantified using selective agar plates. The transformation ratio was normalized as the percentage of transformants relative to the total bacterial count after 6 h of exposure to antibiotics.

Low-dose antibiotic exposure (0.005–5 mg/L) universally elevated both transformant numbers and transformation ratios across all tested antibiotics compared with the no-antibiotic control, with fold changes ranging from 1.28- to 2.72-fold (padj < 0.01, Fig. 7a) and 1.22- to 2.16-fold (padj < 0.01, Fig. 7b), respectively. Notably, exposure to kanamycin and streptomycin, to which the plasmid lacks resistance, resulted in a higher number of transformants compared with the other two antibiotics that the plasmid initially harbors resistance to. However, a divergence emerged in the transformation ratio: at 0.005–0.05 mg/L, ampicillin and tetracycline induced higher values compared with streptomycin or kanamycin, whereas streptomycin-dominated enhancement occurred at higher concentrations (> 0.5 mg/L). This disparity likely reflects antibiotic-specific shifts in total viable recipient populations. Notably, ampicillin and tetracycline at 50 mg/L decreased the transformant number and suppressed the transformation ratio, whereas kanamycin and streptomycin exhibited the opposite effects. This may be caused by varying levels of cell damage caused by exposure to different antibiotics as high concentrations. To validate the successful transformation, we further extracted the pWH1266 plasmid from randomly selected transformants on selective plates. After PCR amplification and agarose gel electrophoresis, we confirmed that the pWH1266 plasmid had been successfully transferred into A. baylyi ADP1 successfully, with clear bands for tetA and blaTEM genes matching the original plasmid (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 7.

Transformation under exposure to antibiotics. (a) Fold change in absolute transformant number. (b) Fold change in the transformation ratio.

ROS generation levels, cell membrane permeability, ATP production, and the expression of transformation-related genes were measured further to unravel the underlying mechanisms. ROS levels were significantly upregulated by 1.11–1.85-fold (padj < 0.01, Fig. 8a), accompanied by a marked increase in cell membrane permeability (1.05–1.57-fold, padj < 0.01, Fig. 8d). Both ROS generation levels and cell membrane permeability showed a dose-dependent effect. Kanamycin and streptomycin at 50 mg/L induced the highest increases in ROS (1.48- and 1.47-fold, padj < 0.01) and cell membrane permeability (1.57- and 1.47-fold, padj < 0.01), which corresponded to an enhanced pWH1266 plasmid transformation ratio (Fig. 8b). Gene expression profiling was conducted with antibiotic concentrations at either a high dose (50 mg/L) or a low dose (0.005 mg/L). High-dose tetracycline and ampicillin (50 mg/L) exhibited the most pronounced upregulation of oxidative stress response genes (oxyR, soxR), a DNA repair gene (recA), and outer membrane porin genes (ompA, ompC), with expression levels 1.37- to 1.43-fold higher (p < 0.01) than in the control (Fig. 8b, e). This also suggests that antibiotics at higher concentrations may disrupt the cell membrane, leading to inhibitory effects on transformation. Antibiotics at lower concentrations enhance transformation, suggesting that moderate oxidative stress (e.g., low ROS levels and membrane perturbations) may transiently induce competence without overwhelming cellular repair mechanisms. Conversely, high-dose tetracycline and ampicillin (50 mg/L) disrupted this balance, driving excessive ROS production and membrane damage that coincided with hyperactivation of stress-response genes, ultimately impairing the efficiency of transformation.

Figure 8.

ROS production, cell membrane permeability, and ATP production of recipient A. baylyi ADP1 under exposure to antibiotics. (a) Fold change in ROS production. (b) Fold change in oxidative stress-related gene expression. (c) Fold change in cell membrane permeability. (d) Fold change in membrane porin-related gene expression. (e) Fold change in ATP production. Statistical significance between the antibiotic-treated and control groups was analyzed using an independent sample t-test and corrected by the Benjamini–Hochberg method, * padj < 0.05 and ** padj < 0.01. Data represent the mean ± SD of biological triplicates.

ATP production in the recipient exhibited a concentration-dependent decline. At 0.005 mg/L of ampicillin, kanamycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline, ATP production was the highest, reaching 1.31-, 1.53-, 1.32-, and 1.38-fold compared with the control group (padj < 0.05, Fig. 8c). The number of transformants was also highest at this concentration (Fig. 7a), indicating a positive correlation between ATP production and transformation efficiency. Conversely, higher doses (50 mg/L) of ampicillin and tetracycline suppressed ATP production by 11% and 20% (padj < 0.05), corresponding to severe declines in the transformation ratio. This suppression likely stems from energy depletion and cumulative cytotoxicity (e.g., ROS overproduction and membrane damage), which impair cellular viability and metabolic activity[81]. Thus, ATP availability can be a critical modulator of HGT. At lower antibiotic levels, enhanced ATP synthesis (padj < 0.05) may energize transformation-related processes (e.g., plasmid uptake, recombination, or repair), driving the transformation ratio.

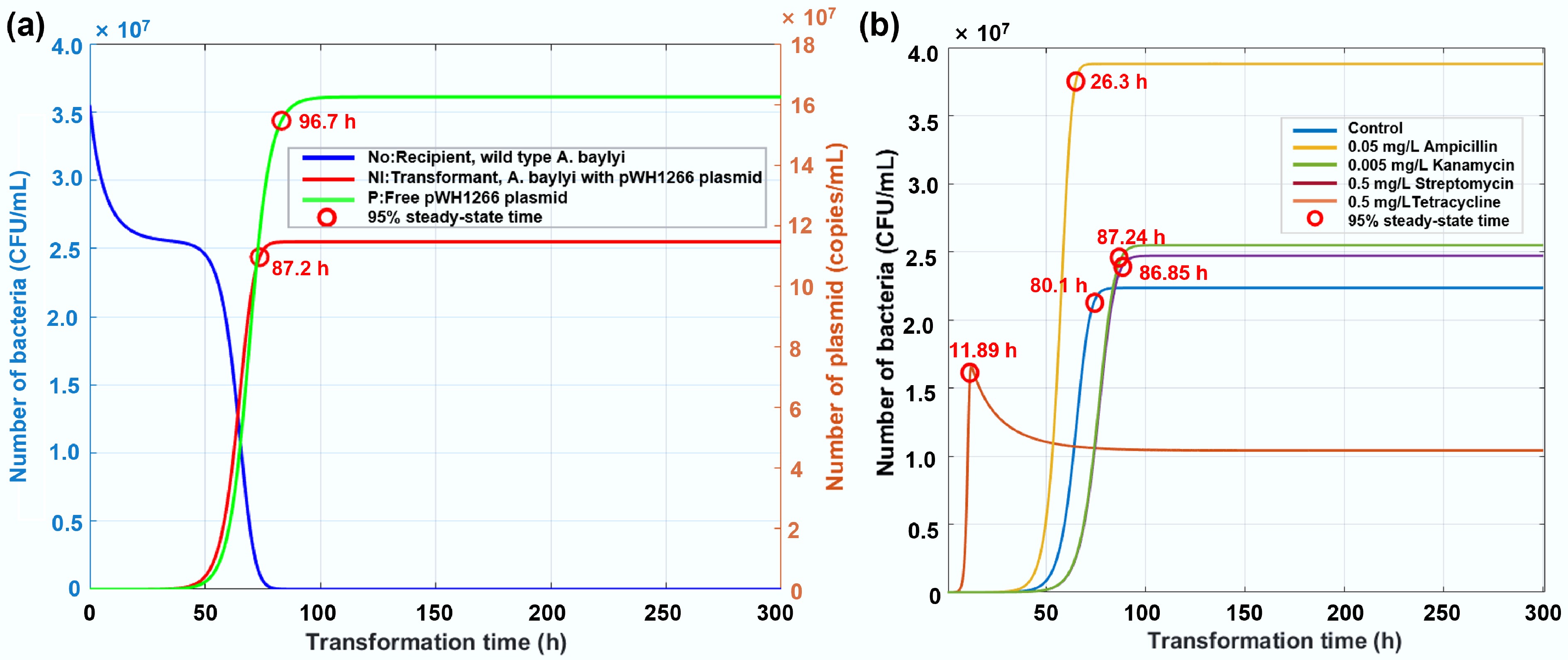

As transformation systems were incubated experimentally for 6 h, whereas free plasmids and competent bacteria can coexist for timespans of several hours to several months in real environments[82], another mathematical model based on ODEs was developed to overcome the experimental limitations.

By utilizing experimental data from the transformation system after 6 h of cultivation, we calibrated the unknown parameters (μ, d) in the model. In the spontaneous transformation system without antibiotics, transformant numbers gradually increased initially and then rapidly grew after a certain period, eventually reaching a plateau and stabilizing (Fig. 9a). In contrast, wild-type recipient bacterial populations declined initially, stabilized transiently, and ultimately underwent complete depletion over prolonged durations[83,84]. The plasmid remained at a stable concentration after initial enhancement, as plasmids can be released from transformants upon their death. For the transformation system with antibiotic dosage, transformant numbers gradually increased over time and eventually stabilized (Fig. 9b, Supplementary Fig. S7). Notably, except for the 0.05 mg/L ampicillin group, where the final transformant number was lower than that of the control group, all other antibiotic treatment groups had a final transformant number higher than the control group, with 0.74 to 1.74-fold enhancement. They reached stability in 26 h, although the slower ones took up to 87 h. However, the group treated with 0.05 mg/L ampicillin reached a stable state earlier than the other groups, namely at 11.89 h. Thus, mathematical modeling further confirms that antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can enhance both the transformant number and accelerate the HGT rate in the long term.

Figure 9.

Simulated changes in the number of bacteria with increased transformation time. (a) Temporal dynamics of recipient bacteria, transformants, and plasmid abundance in the absence of antibiotics. (b) Trajectories of transformant prevalence under exposure to antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations.

-

Antibiotic resistance is not a new phenomenon, but the recent increase in the prevalence of ARGs and ARB is unprecedented. Within the scope of the One Health Perspective, antibiotic resistance can be widely spread among various environments and is considered a biocontaminant. Although antibiotics are traditionally considered to be the most direct factor influencing the development of antibiotic resistance, their effects on the dissemination of antibiotic resistance are controversial[46,47,50,85−88]. Moreover, limited studies have focused on both bacterial genetic stability and the long-term horizontal transfer of ARGs in environmental settings. Here, we provide insights into the effects of four typical antibiotics (i.e., tetracycline, ampicillin, kanamycin, and streptomycin) on bacterial vertical and horizontal transfer of ARGs at concentrations ranging from environmentally relevant to sub-MIC levels.

Three bacterial models were established: the genetic stability model (VGT), conjugation, and transformation. The experimental results indicated that antibiotics can enhance the genetic stability of ARGs. Long-term exposure to ampicillin, kanamycin, and streptomycin significantly increased the retention rate of ARGs within bacterial populations, which is consistent with the theory proposed by Andersson and Hughes that sublethal concentrations of antibiotics drive bacterial adaptive evolution[16]. In contrast, tetracycline exhibited a unique effect, reducing the number of resistant bacteria early in exposure, which is likely caused by its bacteriostatic mechanism of inhibiting protein synthesis[89]. HPLC-based metabolomic profiling further revealed that the transient suppression in the tetracycline-dosed group may correlate with an enhanced bacterial enzyme-mediated degradation capacity[90], though the specific mechanisms of bacterial enzyme mediation require further investigation. In addition, long-term predictions from the mathematical model indicate that although it took 42 d for the resistant bacteria to reach a stable state in the tetracycline treatment group, the final concentration of resistant bacteria was similar to that in the kanamycin or ampicillin treatment groups.

Regarding the horizontal transfer of ARGs, antibiotics at environmentally relevant levels (i.e., 0.005, 0.05, and 0.5 mg/L) can significantly promote the intrageneric, intergeneric, and transformation of ARGs. The levels had increases that ranged from 1.61- to 5.17-fold and from 1.22- to 2.72-fold for conjugation and transformation, respectively. In contrast, antibiotics at high concentrations (50 mg/L) could decrease and suppress both conjugation and transformation. The long-term effects of antibiotics on HGT were indicated by mathematical modeling, which showed that antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can increase the final transformant (ARB) number and accelerate the transformation rate. Thus, in real environments where bacteria and plasmids stably coexist, ARB can reach a new equilibrium at a higher population density and at a faster rate when antibiotics are present. This further highlights the potential health risks associated with antibiotics in the environment.

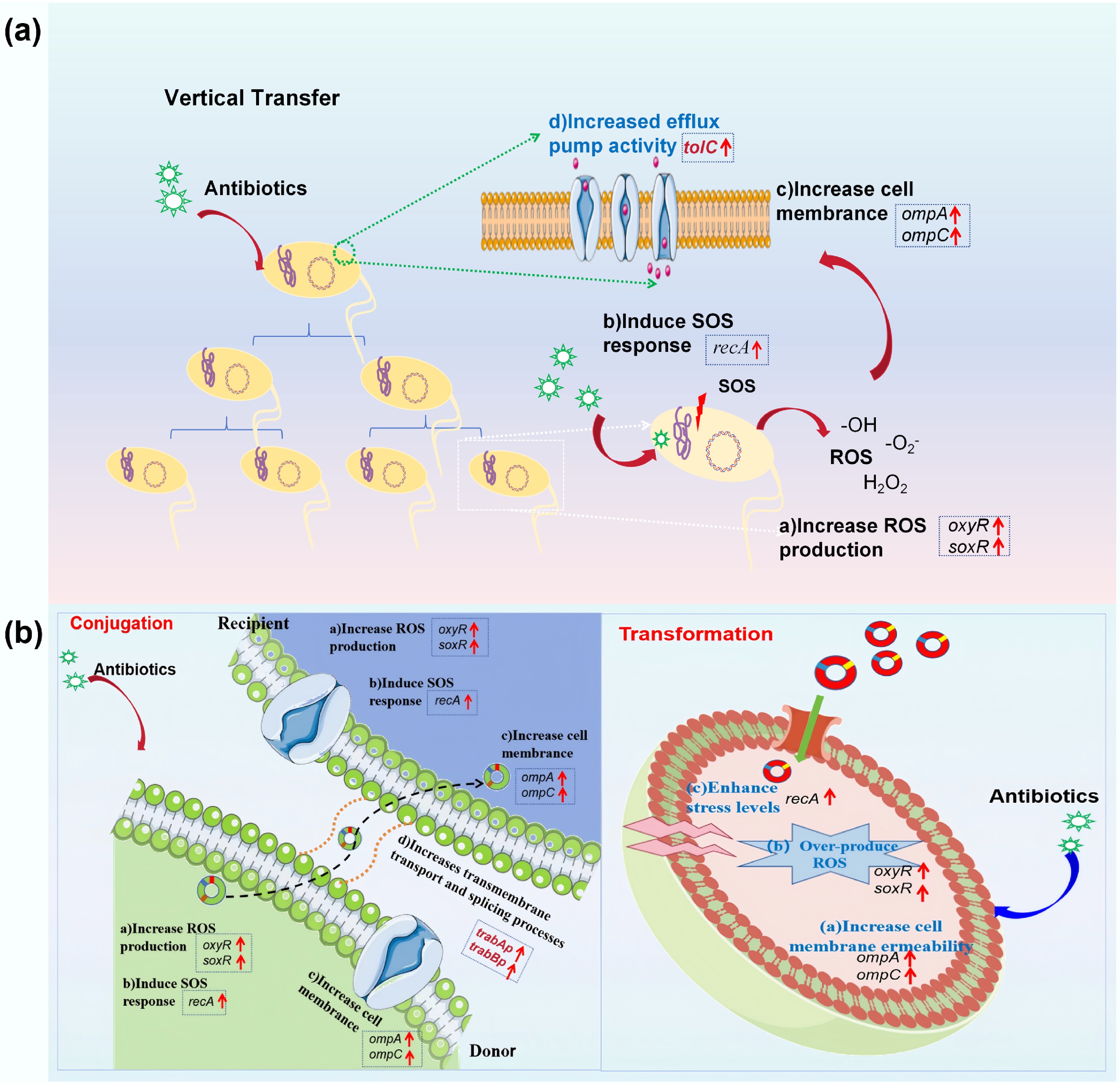

The enhanced VGT and HGT under antibiotic exposure share similar underlying mechanisms, including elevated stress levels, enhanced cell membrane permeability, stimulated bacterial efflux pumps, and increased ATP production (Fig. 10). These were observed through both phenotypic fluorescence and gene expression. During the evolution of ARB, pronounced upregulation of oxidative stress biomarkers (oxyR and soxR, up to 4.47-fold) and SOS response regulators (recA, up to 6.79-fold) were observed, coupled with elevated ROS levels (excluding tetracycline-exposed groups). Among these, the stress response induced by ampicillin in the VGT process was the most pronounced, likely because of the direct action of ampicillin on the cell wall. This validates the hypothesis that hydroxyl radical-induced DNA damage mediates antibiotic-driven genetic transfer[91,92]. Concurrently, the efflux pump-associated tolC and the porin-encoding ompA and ompC exhibited > 5-fold induction, suggesting that bacteria may respond to drug pressure through active efflux (reducing intracellular antibiotic accumulation) and membrane remodeling (limiting drug penetration)[93,94]. Notably, tetracycline uniquely suppressed tolC expression while preserving membrane integrity, a pattern that aligns with a previous study showing that tetracycline exhibits an efflux-independent resistance mechanism in metabolically active E. coli[69]. In the HGT process, elevated cell membrane permeability (up to 1.46-fold) and ATP levels (up to 1.76-fold) were observed, accompanied by increased ROS production (up to 2.36-fold). Gene expression levels (with tetracycline imposing the most significant effect) were consistent with the observed phenotypic phenomenon, where cell membrane, oxidative stress, and ATP levels correlated well with the enhanced HGT. Low doses of gentamicin were also found to increase plasmid transfer through the SOS response[95], and the bacterial cellular energy crisis model of antibiotic lethality is closely related to the membrane's structural collapse[89]. Among the two pathways of HGT applied in this study, the conjugation system relies on the upregulation of trafAp/trabBp for active regulation, whereas the transformation system operates through DNA uptake, highlighting the mechanistic differences between HGT pathways.

Figure 10.

Underlying mechanisms of antibiotic-promoted dissemination of antibiotic resistance. (a) VGT model. (b) HGT model.

Another important observation in this study is the role of ATP as a critical energy molecule for bacterial survival and HGT. Low concentrations of antibiotics were found to increase ATP levels, which aligns with the idea that moderate oxidative stress and mild membrane damage facilitate transformation and conjugation by providing the necessary energy for these processes[96]. However, high doses (e.g., 50 mg/L) triggered ATP exhaustion (a 58% decline), collapsing the energy-dependent HGT machinery. This is consistent with previous studies which showed that high concentrations of antibiotics can cause energy depletion and reduce cellular activity, ultimately inhibiting HGT[20]. This highlights the complex relationship of antibiotic concentration, bacterial stress responses, and the efficiency of gene transfer.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that antibiotics significantly promote the spread of ARGs, addressing VGT and HGT independently. For example, low concentrations of ciprofloxacin and streptomycin increase bacterial mutation rates, enhancing ARG enrichment, whereas sulfamethoxazole promotes VGT and amoxicillin inhibits it by suppressing bacterial growth[15,46]. In terms of HGT, low concentrations of antibiotics, including gentamicin, chlorhexidine, and triclosan, can facilitate the conjugative transfer of ARGs, which drives resistance spread. Some studies also report that certain compounds (e.g., tetracycline, amoxicillin) can inhibit the transfer of resistance genes[50,97]. However, these studies focus on the short-term effects of VGT and HGT separately, overlooking their long-term simultaneous interactions. In reality, VGT and HGT are mutually reinforcing: VTG provides hosts for the resistance genes, whereas HGT accelerates their dissemination across bacterial populations.

In this study, we focusd on investigating the dual effects of antibiotics on the genetic stability and HGT of ARGs. The results reveal that low antibiotic concentrations promote HGT, but high concentrations inhibit it. Long-term exposure to low doses (i.e., 0.005–0.5 mg/L) of antibiotics could also enhance the bacterial genetic stability of ARGs. This highlights the potential ecological and health risks posed by sub-MIC antibiotic residues. Additionally, mathematical model simulations and long-term predictions demonstrate that prolonged exposure to antibiotics can significantly accelerate the spread of ARGs in real environments. This finding provides new evidence for the long-term impact of antibiotics on the dissemination of ARGs.

Regarding the comparison of different antibiotics, tetracycline exhibited a unique effect, with the number of resistant bacteria in the tetracycline-treated group remaining lower than that of the control for at least 4 d in the VGT experiments. In contrast, in the HGT experiments, although exposure to 50 mg/L tetracycline significantly reduced the number of resistant bacteria; this concentration showed a resistance-enhancing effect similar to that of the other three antibiotics. This may be related to the antibiotic's mode of action and may need further investigation. In summary, this study highlights the dual effects of typical antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations on the dissemination of antibiotic resistance, as demonstrated through both experimental studies and mathematical simulations. The findings provide valuable insights for future antibiotic management strategies.

However, the results of this study are primarily based on controlled experimental conditions and do not fully reflect the complex scenarios of coexisting multiple pollutants, strains, and plasmids in real-world environments. In natural ecosystems, interactions between different pollutants, the diversity of microbial community structures, and the varied modes of plasmid carriage could significantly affect the stability and transfer efficiency of ARGs. Future studies incorporating environmental samples are needed to enhance the environmental applicability and ecological relevance of these methods.

-

This study reveals, through multidimensional evidence, that antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations (i.e., 0.005, 0.05, and 0.5 mg/L) drive the spread of ARGs in many ways, including promoting the retention rate of ARGs during bacterial evolution, increasing the intrageneric and intergeneric transfer of ARGs, and enhancing the transformation of ARGs. On the contrary, antibiotics at higher levels (e.g., 50 mg/L) inhibit the conjugation and transformation ratios. Elevated ROS production, increased cell membrane permeability, stimulated stress levels, and promoted ATP are correlated with the enhanced dissemination of ARGs. Among these factors, ATP plays a pivotal role in regulating HGT efficiency. A mathematical model based on bacterial dynamic changes was established, and parameter calibration according to experimental data indicated that prolonged exposure to antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can promote the proliferation of resistant bacteria through both VGT and HGT. These findings underscore the importance of reconsidering antibiotic usage and discharge standards in the context of environmental health.

We would like to thank the Analytical & Testing Center of Tiangong University for the high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry work.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0005.

-

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Jie Yang, Yifan Liu, and Mengke Geng. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yue Wang and Yifan Liu, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

-

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42307529 and 42577486), Hebei Natural Science Foundation (Nos. C2023110006 and E2023110001), the Research Fund of Tianjin Key Laboratory of Aquatic Science and Technology (No. TJKLAST-PT-2021-04), and Cangzhou Institute of Tiangong University (No. TGCYY-F-0103).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Antibiotics can promote the genetic stability of ARGs.

Antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can elevate both intrageneric and intergeneric transfer of ARGs.

Antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can enhance the transformation of ARGs.

Mathematical models are proposed to predict the long-term effects of antibiotics on the dissemination of ARGs.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Table S1 Primer list.

- Supplementary Table S3 Tetracycline measurement results.

- Supplementary Table S3 Variables and parameters used in the VGT model.

- Supplementary Table S4 Variables and parameters used in the HGT model.

- Supplementary Text S1 Bacterial Cultivation Conditions.

- Supplementary Text S2 ROS and cell membrane permeability detection.

- Supplementary Text S3 ATP detection.

- Supplementary Text S4 RT-qPCR technique.

- Supplementary Text S5 Model calibration function.

- Supplementary Text S6 Determination of tetracycline concentration by high-performance liquid chromatography.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The OD600 values of bacterial cultures under antibiotic pressure during the evolution process: (a) E. coli MG1655 with RP4 plasmid, (b) E. coli LE392 with pWH1266 plasmid, and (c) E. coli HB101.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The growth curves of three bacterial strains under antibiotic pressure (CON: control group): (a) E. coli with RP4 plasmid. (b) E. coli with the pWH1266 plasmid. (c) E. coli HB101.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Tetracycline concentration detection. (a)Tetracycline standard calibration curve. (b) Chromatogram of the tetracycline control group. (c) Chromatogram of the tetracycline sample group containing E. coli MG1655 with RP4 plasmid. (d) Chromatogram of the tetracycline sample group containing E. coli LE392 with pWH1266 plasmid.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 (a) The variation in the number of recipient bacteria E. coli HB101 on agar plates. (b) The variation in the number of recipient bacteria S. enterica on agar plates. Significant differences between the antibiotic treatment group and the control group are indicated as: * padj < 0.05 and ** padj < 0.01.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 PCR electrophoresis images of tetA and blaTEM genes in the conjugative RP4 plasmid.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 PCR electrophoresis images of the tetA and blaTEM genes in the transformants carrying the pWH1266 plasmid.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Trajectories of transformant prevalence under the exposure of antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang Y, Liu Y, Yang J, Geng M, Jia H, et al. 2025. Antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can promote the dissemination of antibiotic resistance via both vertical and horizontal gene transfer. Biocontaminant 1: e005 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0005

Antibiotics at environmentally relevant concentrations can promote the dissemination of antibiotic resistance via both vertical and horizontal gene transfer

- Received: 10 July 2025

- Revised: 17 September 2025

- Accepted: 17 October 2025

- Published online: 07 November 2025

Abstract: Antibiotic resistance has emerged as a significant global threat to human health and is considered a biocontaminant. Both vertical gene transfer (VGT) and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) play important roles in the spread of antibiotic resistance. The impact of environmentally relevant concentrations of typical antibiotics on the spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) through these two modes of transmission, as well as the underlying mechanisms, remains an urgent area of research. This study explores the effects of four typical antibiotics (tetracycline, ampicillin, kanamycin, and streptomycin) at environmental concentrations on the genetic stability and horizontal transfer of ARGs across three models (vertical transfer, conjugation, and transformation), along with the mechanisms involved. We conclude that, except for tetracycline, antibiotics exposed to the other three environmental concentrations could potentiate the persistence of resistance in resistant bacteria. Furthermore, all antibiotics, at concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 5 mg/L, were able to induce horizontal shifts in ARGs. Various metrics were employed in the phenotypic and genotypic analyses. The results indicated that enhanced resistance following exposure to antibiotics was directly correlated with the overproduction of reactive oxygen species, an elevated stress response, strengthened efflux pump activity, and intensified cell membrane permeability. Mathematical models were also used to predict the impact of prolonged bacterial exposure to antibiotics on the stability of ARGs and plasmid transformation. Our findings highlight the risks associated with the development of antibiotic resistance under environmentally relevant concentrations of antibiotics.