-

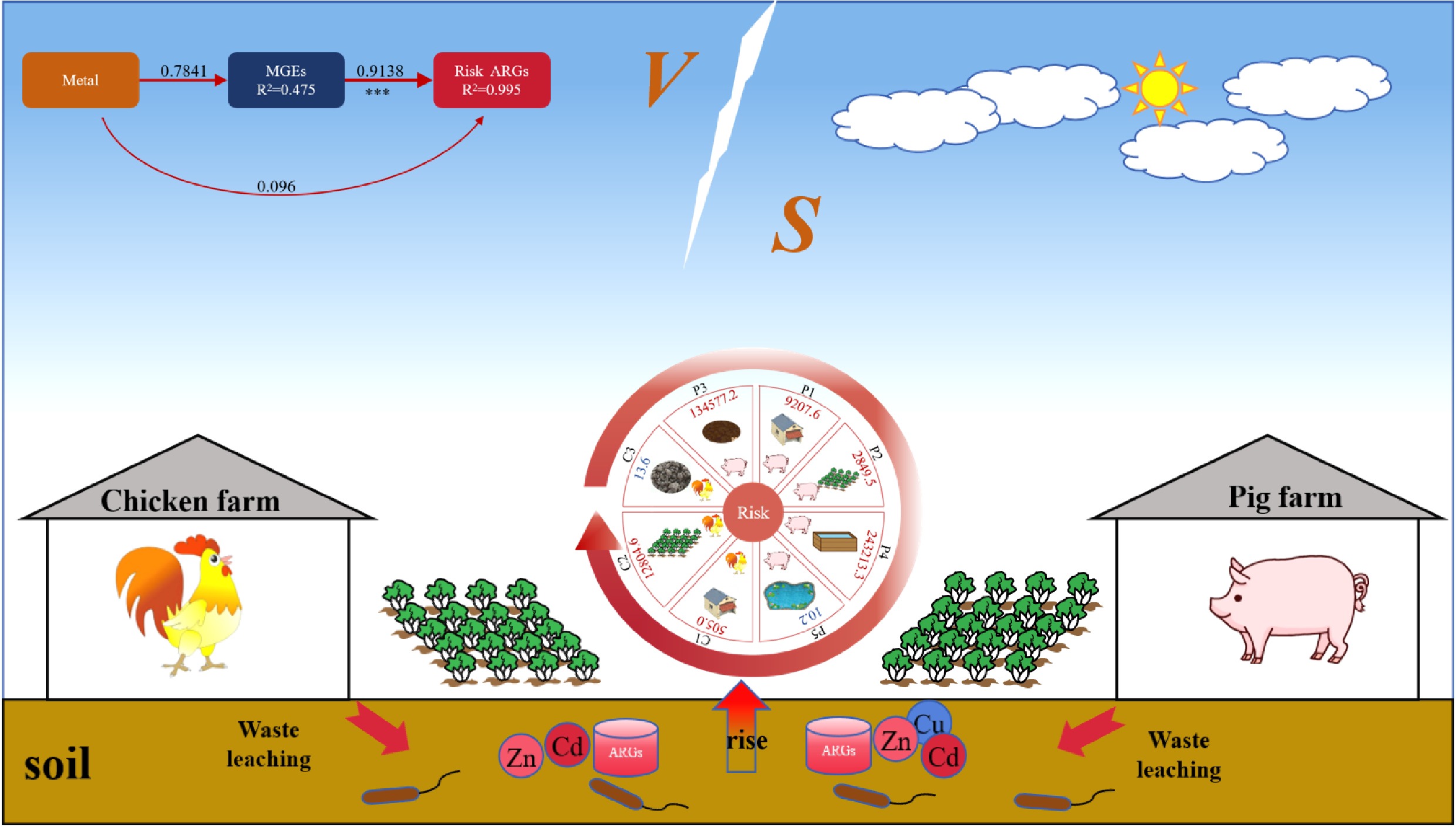

Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) have become a critical global threat to public health and ecosystems, with approximately 700,000 annual deaths linked to antibiotic resistance[1,2]. The proliferation of ARGs is driven by the extensive use of antibiotics and heavy metals in agriculture, which impose selective pressures that promote microbial evolution and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) mediated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs)[3,4]. These determinantes of resistance are now pervasive across diverse environmental matrices, including soil, water, and air, where they interact dynamically with microbial communities[5−7], amplifying ecological risks.

Intensive livestock farming represents a major reservoir of ARGs because of routine antibiotic administration and the use of metal-based feed additives (e.g., Cu, Zn). Global antibiotic consumption by livestock was projected to surpass 100,000 tons by 2030[8], yet < 30% of the administered antibiotics are metabolized in animals[9]. Residual antibiotics and metals accumulate in manure, where they persistently select for resistant gut microbiota[10]. These contaminants are subsequently introduced into agricultural soils via the application of manure or other pathways, leading to elevated levels of heavy metals and antibiotics. Consequently, this process drives the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, ultimately compromising key ecological functions and increasing the risks to human health through potential transmission pathways[11−13]. A critical concern stems from the capacity of ARGs to persist as extracellular DNA in environmental matrices, independent of their original host cells. These extracellular ARGs can be horizontally transferred across microbial taxa via MGEs[14,15], thereby amplifying ecological risks and establishing potential transmission routes to human populations.

Livestock and poultry manure have received considerable scientific attention as a major reservoir of environmental pollutants, particularly because of the significant accumulation of heavy metals and antibiotics in animal excreta[16,17]. Nevertheless, the prevalence and dissemination of ARGs are influenced by a complex interplay of biotic and abiotic factors. Specifically, the dissemination of ARGs among microorganisms is facilitated by the presence of MGEs, and variations in microbial communities affect the abundance of potential host bacteria for ARGs, thereby influencing the prevalence of ARGs[18,19]. In addition, heavy metals promote ARGs through mechanisms such as co-selection (including co-resistance and cross-resistance) and regulatory responses, and by influencing biofilm formation[20]. Agricultural soils adjacent to farming operations serve as critical ARG sinks, with applications of manure as a fertilizer establishing direct contamination pathways. This practice not only introduces ARGs into croplands but also increases the risk of their uptake by edible plants[21].

Despite the extensive research conducted on heavy metal and ARG contamination in livestock farming, critical knowledge gaps remain. First, most previous studies have focused on a single type of livestock farm, complicating comparative analyses of contamination's characteristics and risks across different livestock farming systems. Second, there is still a lack of comparative analyses that quantify the significance and interaction of heavy metals, MGEs, and microbial communities in shaping the dissemination of high-risk ARGs. Third, and most importantly, there is a lack of assessment of the direct human health risks posed by ARG contamination in the environments surrounding livestock farms, which is essential for developing risk-based management strategies. Furthermore, most previous studies have treated ARGs as a single entity, overlooking the fact that ARGs posing different levels of human health risks may exhibit distinct environmental behaviors and be driven by different ecological processes. Understanding whether and how the drivers (e.g., heavy metals, MGEs, microbial hosts) vary for ARGs in different risk categories is crucial for developing risk-based management strategies.

To address these gaps, we conducted a comparative field investigation of large-scale pig and chicken farms within the Poyang Lake watershed. Using high-throughput sequencing and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), we analyzed microbial communities, ARGs, and MGEs in farm-associated soils. We elucidated the interactions among heavy metals, microbiota, and ARGs, identifying key drivers of ARGs' dissemination. By prioritizing high-risk ARG subtypes and assessing their environmental determinants, this work provides a basis for targeted mitigation strategies in agricultural systems. This study had four primary objectives: (1) To characterize the spatial distribution and concentration profiles of heavy metals and ARGs in soils adjacent to intensive pig and chicken farming operations; (2) to determine the taxonomic profiles of characteristic microorganisms and MGEs within these soil ecosystems; (3) to elucidate the key drivers governing ARGs' abundance and dissemination patterns through multifactorial analysis; and (4) to prioritize and calculate the human health risk of high-risk ARG subtypes at different sampling sites and to explore their environmental determinants. Collectively, our work aimed to elucidate the co-occurrence patterns of heavy metal and ARG contamination across different livestock production systems and to quantify the associated human health risks, thereby providing a foundation for developing targeted ARG mitigation strategies in agricultural soils.

-

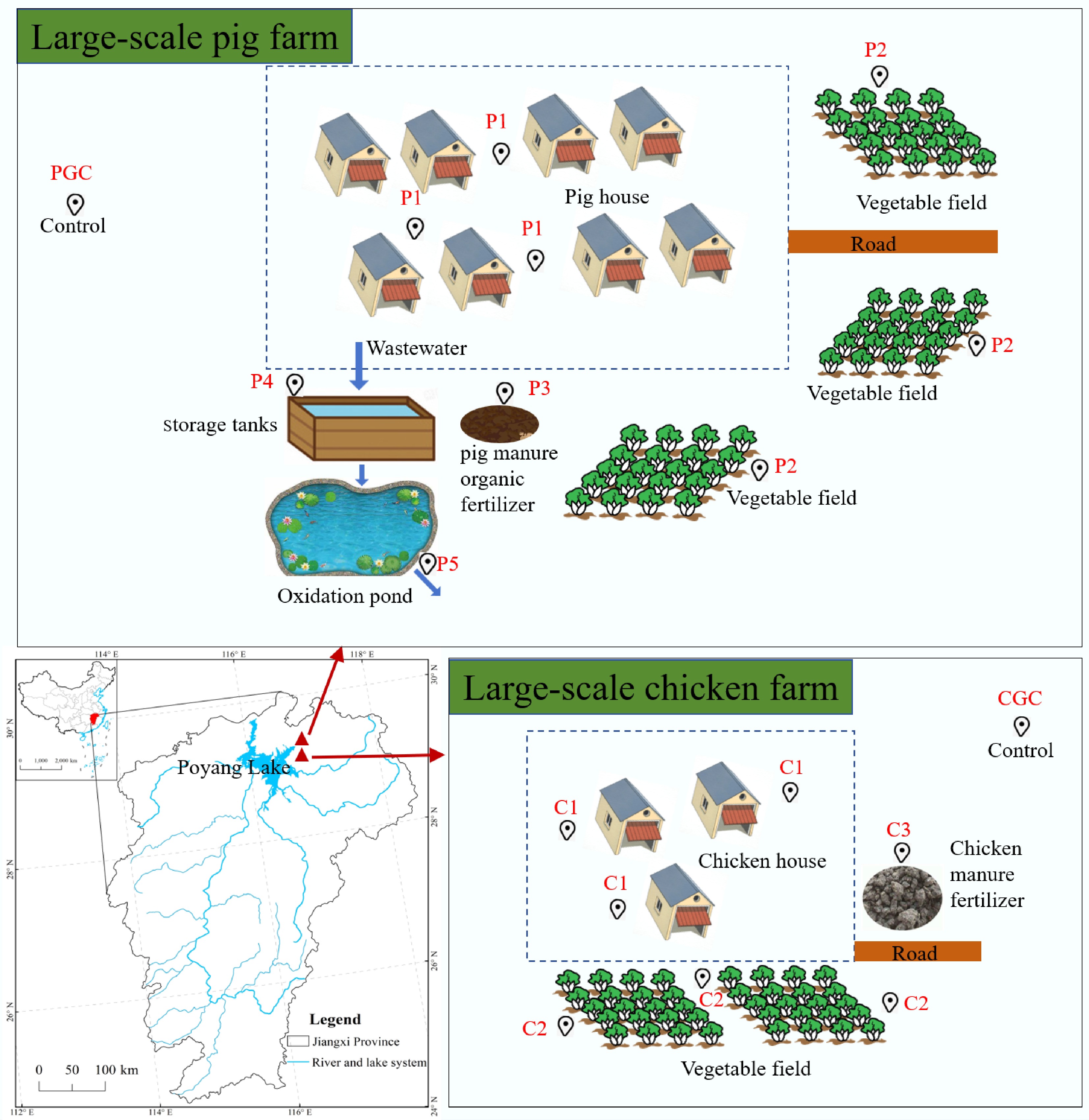

Soil samples were collected from large-scale pig and chicken farms on the shore of Poyang Lake (Fig. 1). Poyang Lake is the largest freshwater lake in China and has maintained a generally sound ecological environment over the past few decades. However, in recent decades, nonpoint source pollution from the surrounding areas has emerged as a growing threat to its water quality[22]. The pig farm produces 2,000 meat pigs per year. All pig wastewater is collected in a storage tank and then flows into farmland after passing through the oxidation pond. The chicken farm has a breeding scale of 20,000 producing hens, laying 9,000 eggs daily. Control soil samples, designated PGC and CGC, were collected from areas outside the direct influence of the pig and chicken farms, respectively. Samples P1 and C1 were obtained from areas adjacent to the livestock housing, whereas samples P2 and C2 were collected from nearby vegetable fields. For each designated sampling point, a single composite sample was formed by mixing material collected from three randomly selected subpoints within a 10 m × 10 m area. This composite sample was considered as one biological replicate. Pig manure organic fertilizer (P3), with a water content of about 50%, and chicken manure organic fertilizer (C3), with a water content of about 20%, were also sampled in the workshops of the farms. In addition, water samples of influent from the storage tank of the pig farm were collected as P4, and water samples of the effluent from the oxidizing pond after treatment were collected as P5.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the sampling site next to Poyang Lake. PGC, P1, P2, and P3 are soil samples from the pig farm control, pig house, vegetable field, and pig manure organic fertilizer, respectively; P4 and P5 are water samples from the pig farm storage tank influent and oxidation pond effluent. CGC, C1, C2, and C3 are soil samples from chicken farm control, chicken house, vegetable field, and chicken manure fertilizer, respectively.

Soil and water samples were collected in sterile bags and polyethylene bottles, respectively, transported under refrigeration to the laboratory for immediate pretreatment, and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from all samples using FastDNA SPIN kits following the manufacturer's instructions, with specific processing and extraction methods described in detail in a previous study[23]. Heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd) were quantified using inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; NexION 2000, PerkinEImer, USA). The ICP-MS system was calibrated using a series of multi-element standard solutions (PerkinElmer Pure Plus Standard) covering a concentration range of 0–500 μg/L. Quality assurance included the use of blank controls (2% HNO3), continuous internal standardization, and analysis of certified reference materials (NIST SRM 2709a San Joaquin Soil and ERM®-CA713 Wastewater) every 20 samples to verify accuracy. Recovery rates for all metals ranged between 90% and 105%.

High-throughput qPCR and data analysis

-

ARGs and MGEs were detected by high-throughput qPCR (HT-qPCR) using the Wafergen SmartChip Real-Time PCR System (Wafergen, UCA). In total, 296 primer sets were used: 283 for ARGs, 12 for MGEs, and 1 for 16S rRNA genes[24]. The HT-qPCR conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 30 s and annealing at 60 °C for 30 s. A cycle threshold of 31 was set as the detection limit. The relative abundance of each ARG and MGE was calculated by normalizing its copy number to that of the 16S rRNA gene in the same sample, expressed as copies per 16S rRNA gene copy[23]. Each HT-qPCR run included: (1) No-template controls (NTCs) containing molecular-grade water instead of DNA to monitor contamination, (2) positive controls using plasmid DNA carrying specific target genes, and (3) triplicate reactions per sample to assess technical variability. Amplification reactions with efficiency outside the range of 90%–110% or with a coefficient of determination (R2) below 0.99 for standard curves were excluded from further analysis. Comprehensive data pertaining to all 296 target genes are listed in Supplementary Table S1, encompassing 283 ARGs, 12 MGEs, and 1 16S rRNA gene.

High-throughput Illumina sequencing and data processing

-

The bacterial community structures in the samples were characterized using a high-throughput Illumina sequencing technique (Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) as described previously[25]. The V4–V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the universal primers 515F (GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG) and 907R (CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification program consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Negative controls (no template) were included during amplification and sequencing to detect potential contaminant DNA. The purified PCR products were sequenced by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. using the Illumina platform. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered at 97% similarity using UPARSE 7.1. The SILVA 16S rRNA database (Silva v128) was used to assign taxonomic classification to each sequence with a 70% confidence threshold.

Determining the risky ARGs in different samples

-

On the basis of their human accessibility, mobility, human pathogenicity, and clinical availability, risky ARGs were categorized into four classes (Q1–Q4), and then the health risk of each sample was calculated from the RI value of each risky ARG[26]. The RI for each sample is calculated as:

$ {{RI}}_{{sample}}={\sum} _{{i}{=1}}^{{n}}{{Abundance}}_{{i}}\times{{RI}}_{{i}} $ (1) where, Abundancei is the relative abundance of ARG i in the sample, and RIi is the RI of ARG i.

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test in SPSS. Asterisks indicate the levels of statistical significance as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). All data, including means, standard deviations, and standard errors, were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2016. Bar graphs were created using Origin 9. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), redundancy analysis (RDA), and partial least squares path modeling (PLSPM) graphs were calculated and plotted using R 4.4.2. Co-occurrence networks were constructed using Gephi 0.9.2, with a threshold coefficient of ≥ 0.7 and p < 0.05.

-

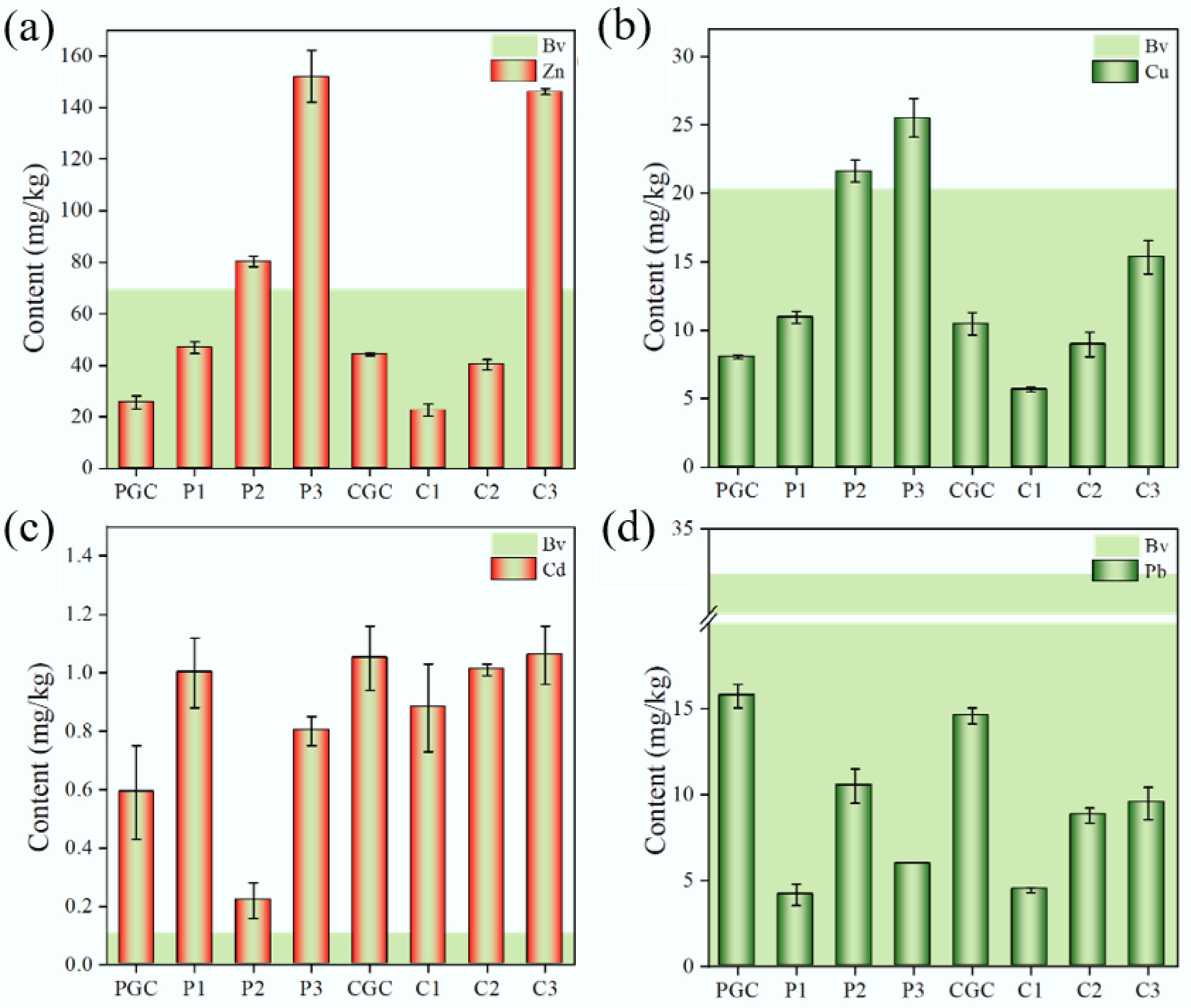

Heavy metal contamination poses a significant threat to agricultural ecosystems, with livestock farming identified as a major contributor to heavy metals' accumulation and dispersion in the surrounding soil systems[27,28]. Our analysis revealed pronounced zinc (Zn) enrichment in organic fertilizers. Specifically, pig manure fertilizer (P3) and dry chicken manure (C3) exhibited Zn concentrations 2.2- and 2.1-fold higher, respectively, than the regional soil background levels[29]. Secondary Zn accumulation (2.1-fold above the background) was also observed in the adjacent vegetable plots (P2) (Fig. 2a). Copper (Cu) contamination showed a similar trend, with P3 containing the highest Cu content (1.26-fold above the background value), followed by P2 (Fig. 2b). The elevated Zn and Cu concentrations in manure samples (P3, C3) were primarily attributed to their use as feed additives[30,31]. Notably, significant Zn and Cu accumulation was observed in soils associated with pig farming, whereas soils around poultry facilities, including chicken manure-amended plots, showed no comparable contamination. This disparity suggests a greater propensity for heavy metal transfer from swine production systems to adjacent agroecosystems than from poultry systems. This phenomenon may be attributed to the use of liquid manure or slurry (which contains a higher water content) in pig farms. Such practices are more prone to runoff or seepage, thereby potentially facilitating the transportation of heavy metals to the adjacent farmland. In contrast, the reduced water content in chicken manure likely impedes its mobility. Although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, future studies should focus on elucidating key factors such as differences in feed additives, manure management practices, and hydrological leaching behaviors to develop targeted mitigation strategies. Regarding cadmium (Cd), the concentrations at all sampling points were 6 to 10 times higher than the regional soil background value, except for P2, which showed a twofold increase (Fig. 2c). However, when compared with the control samples, Cd concentrations did not show significant elevation. This suggests that Cd contamination may be unrelated to livestock and poultry farming environments and is more likely associated with the local soil conditions. In contrast to Zn and Cu, the lead (Pb) content of the samples remained within the established soil background value (Fig. 2d). Analysis of the water samples (P4 and P5) revealed comparatively high Cu levels in the influent reservoir (P4), with a substantial reduction observed in the treated effluent from the oxidation pond (P5). This indicates that the treatment processes were largely effective in removing copper (Supplementary Table S2). In summary, Cu and Zn were identified as the predominant heavy metals accumulating in both pig and chicken farming systems, showing significantly higher enrichment in manure. The pig farm system demonstrated a markedly greater propensity to disperse these heavy metals into adjacent areas than the chicken farm system.

Figure 2.

Concentrations of heavy metals in different soil samples. Light green (Bv) indicates the soil's backgroundvalues.

Pollution characterization of ARGs and MGEs from the selected farms

Diversity of ARGs and MGEs

-

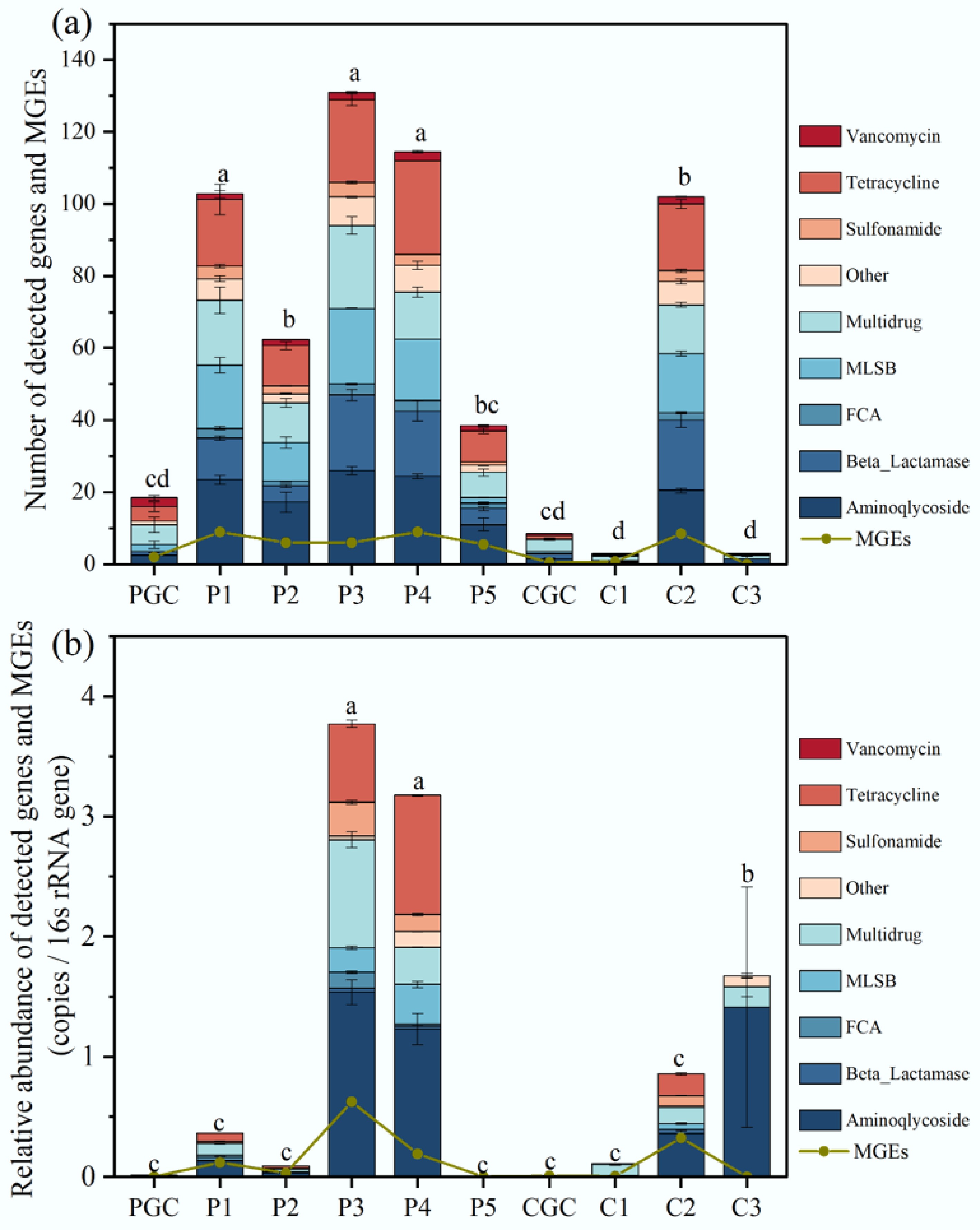

Quantitative analysis revealed significant spatial heterogeneity in ARG and MGE profiles across the sampling locations (Fig. 3a). The most prevalent ARGs detected included those for aminoglycosides; beta-lactamases; florfenicol, chloramphenicol, and benzylpenicillin (FCA); macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin (MLSB); and tetracycline. The number of ARG subtypes detected varied among the livestock farms and sampling locations. The pig farm organic fertilizer (P3) had the highest number of subtypes, with 131 (46.3% detection rate), followed by the P4 sample with 115 (40.1% detection rate). Overall, ARG abundance in all pig farm-associated samples exceeded that of the control (PGC). Chicken farm samples displayed divergent trends: The vegetable plot (C2) harbored 102 ARG subtypes (36.0% detection), whereas dried chicken manure (C3) contained only 5 subtypes, which is substantially lower than the 262 subtypes reported in poultry waste by Błażejewska et al.[32]. This discrepancy may stem from reduced water content during manure desiccation, which likely diminishes microbial viability and the associated carriage of ARGs. Conversely, undried pig manure (P3), with a higher moisture content, supported richer microbial communities, facilitating the preservation of ARGs. Regarding relative abundance, the primary categories of ARGs identified in pig and chicken farm samples were as follows: Aminoglycosides (25.1%), multidrug (22.4%), tetracyclines (15%), and MLSB (10.8%). Furthermore, beta-lactamase was identified as the predominant ARG type (except at the C3 locus) in chicken farms, accounting for 17.4%–20% of all ARGs (Supplementary Fig. S1). These findings indicate that fecal sources from different livestock species harbor distinct ARG profiles and transmit them. This phenomenon may correlate with differences in medication practices and antibiotic classes used in pig and chicken farms. However, variations in resistance gene types still cannot fully explain antibiotic usage patterns, as co-resistance mechanisms occur among certain antibiotics and between antibiotics and heavy metals. The detected ARGs from the pig and chicken farms encompassed nearly all the predominant antibiotic classes commonly used in both human and veterinary medicine, thereby exemplifying the comprehensive range of resistance mechanisms observed. The dominant mechanisms were antibiotic inactivation (24%–50% of ARGs) and efflux pumps (20%–53%), followed by cellular protection (15%–28%). However, in the C3 samples, antibiotic inactivation accounted for 80% of cases, whereas efflux pumps accounted for 20% (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 3.

(a) Number of ARGs and MGEs detected in each sample. (b) Relative abundance of ARGs and MGEs detected in each sample. ANOVA was performed for each sample. Tukey's test was performed for two different samples. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Abundance of ARGs and MGEs

-

Quantitative analysis revealed significant spatial disparities in ARG abundance across sampling sites (Fig. 3b). The P3 sample exhibited the highest ARG concentration (3.78 copies/16S rRNA gene), followed by the P4 sample (3.18 copies/16S rRNA gene). The high diversity and abundance of ARGs in P3 and P4 indicate that raw wastewater from the pig farm and swine manure serve as critical reservoirs for ARGs. A notable 99% reduction in ARG abundance was observed between the influent (P4) and the treated effluent (P5) from the oxidation pond, demonstrating its remarkable efficacy. Though such ponds are known to remove conventional pollutants such as nitrogen and phosphorus[33], the mechanisms specific to ARG removal are not fully understood. Experimental data revealed a 91% reduction in Cu concentration in the treated wastewater (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, nutrient depletion in oxidation ponds, such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), may reduce microbial abundance, potentially limiting ARGs' persistence by limiting host cells' availability.

In summary, both pig and chicken farming activities were found to elevate ARG levels in the surrounding soil environment. For instance, the relative abundance of ARGs detected in soil sample P1 near the pig house (0.36 copies/16S rRNA gene) was 27-fold higher than that of the control PGC (0.013 copies/16S rRNA gene). It was noteworthy that sample C3 exhibited a low diversity of ARG subtypes, yet its relative abundance (1.67 copies/16S rRNA genes) was 186-fold higher than that of the CGC. This finding suggested that microorganisms may harbor a small but highly abundant number of resistance genes to ensure survival under extreme conditions, such as desiccation. This finding underscores the need for measures to mitigate ARGs in chicken manure fertilizers, thereby preventing their accumulation and migration to other environments during use. Notably, 85.6% of the ARG abundance (1.67 copies/16S rRNA gene) in C3 was attributed to the aminoglycoside resistance gene aadA1. This gene is frequently located within the gene cassettes of Class 1 integrons, which facilitate the capture and expression of resistance genes via site-specific recombination, enabling horizontal transfer between bacterial strains[34]. The widespread use of aminoglycoside antibiotics in both clinical and agricultural settings drives the selection of aadA1. Evidence indicates its widespread detection in livestock farming environments (e.g., pig and chicken manure), urban sludge, and hospital environments[35−37]. The abundance of ARGs (1.67 copies/16S rRNA gene) detected in C3 (dry chicken manure fertilizer) was lower than the 2.54 copies/16S rRNA gene detected in wet chicken manure by Błażejewska et al.[32], indicated that lowering the water content of chicken manure is effective in reducing the diversity and abundance of ARGs (except aminoglycoside), thereby reducing the associated risks to human health. This finding suggests that managing soil moisture could be a viable approach to curtail ARGs' proliferation in agricultural environments.

The abundance in the soil sample C2 from the vegetable patch near the chicken farm (0.86 copies/16S rRNA gene) was 96-fold higher than that of the control CGC (0.009 copies/16S rRNA gene), suggesting that the application of chicken manure fertilizer in the vegetable plot may have contributed to this increase. Contrary to patterns in manure samples, soil from chicken manure-amended vegetable plots (C2) exhibited markedly elevated ARG diversity, abundance, and associated human health risk indices (12,804.6) compared with pig manure-treated soils (Figs 3 & 6d). Furthermore, chicken manure fertilization enriched soil levels of tetracycline, sulfonamide, and multidrug resistance genes—contaminants that are undetectable in the original fertilizer. This may be caused by the co-selective pressure of heavy metals in the soil of the vegetable plots from chicken manure. This finding underscores that the risk posed by manure cannot be assessed solely by focusing on ARGs. Critically, both types of manure increased soil ARG levels, which could be transferred to edible vegetables via bacteria, thereby increasing ARGs' abundance on vegetable leaves and posing a potential threat to human health[38]. Therefore, it is imperative to treat livestock manure before use to mitigate the potential contamination of vegetable plots with ARGs.

Conventional composting is a prevalent treatment for antibiotics and ARGs in livestock manure[39,40]; however, this process can inadvertently increase the overall abundance of ARGs, including certain high-risk ARGs[41,42]. In contrast, hyperthermophilic composting, which uses elevated temperatures, has been shown to be more effective at removing ARGs, yielding more consistent and efficient outcomes[43]. The extreme temperatures (> 70 °C) in hyperthermophilic composting eliminate most heat-sensitive pathogens, preventing them from harboring ARGs. Crucially, the heat also disrupts cells, exposing and degrading intracellular ARGs and denaturing free extracellular DNA (eDNA), which blocks HGT via transformation. This yields a high-quality, safe organic fertilizer that enhances soil fertility and supports circular agriculture. As a superior alternative to traditional composting, it can be easily implemented in existing facilities. In addition, hydrothermal carbonization, which recovers nutrients from manure while producing a biofertilizer with a low risk of heavy metal contamination, is a potential alternative to manure treatment[44,45]. Hydrothermal carbonization utilizes considerably more intense reaction conditions than composting, which completely eradicate all pathogens and associated ARG transmission risks. Nevertheless, the high capital and operational costs could restrict its adoption for fecal management. The relative abundance of MGEs exhibited a distribution pattern congruent with that of ARGs. Peak MGE abundance was identified in Sample P3 (0.63 copies/16S rRNA gene), followed by Sample C2 (0.33 copies/16S rRNA genes). A notable deviation occurred in Sample C3, where MGEs were undetectable despite elevated ARG abundance. This suggests that although reducing manure's moisture content cannot fully eliminate ARGs, it exerts a stronger suppressive effect on their HGT mechanisms. Collectively, ARGs originating from the farms were predominantly localized in manure reservoirs, with soils amended with poultry-derived fertilizers exhibiting significantly elevated ARG abundance compared with nonamended control sites.

Characterization of bacterial communities from the selected farms

Diversity of bacterial communities

-

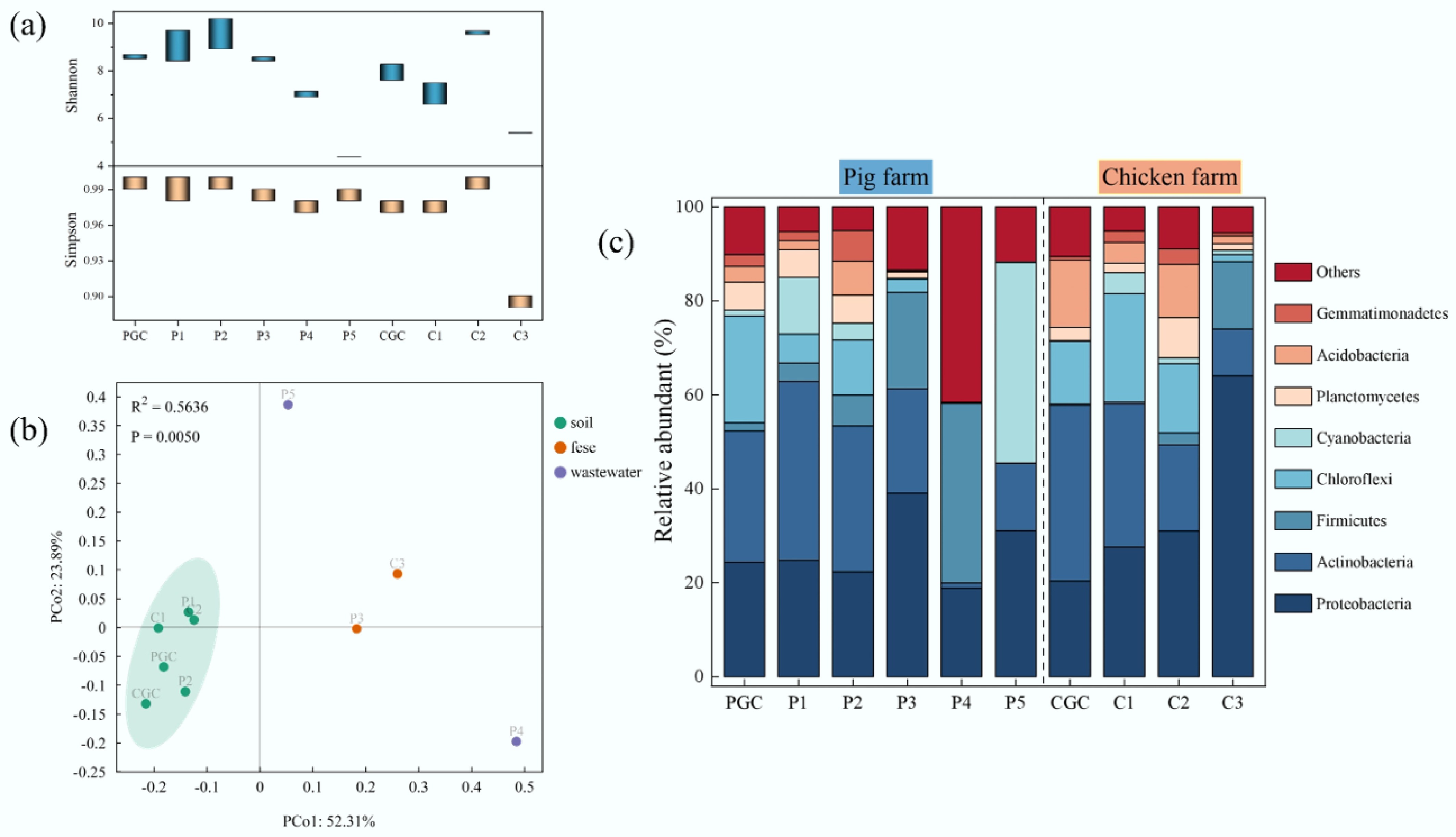

In this study, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to characterize variations in and the distribution of bacterial communities. Alpha diversity, assessed by the Shannon and Simpson indices, indicated that the bacterial diversity in dried chicken manure (C3) was significantly lower than in all other samples (Fig. 4a). Principal coordinate analysis (PCA) based on Bray–Curtis distances revealed that microbial communities clustered primarily by sample type (soil, manure, and wastewater), independent of the farm of origin (Fig. 4b). In contrast, the microbial communities of the influent (P4) and effluent (P5) water from the same pig farm were distinctly separated, indicating that the wastewater treatment process profoundly reshaped the bacterial community structure.

Figure 4.

Microbial communities in samples from the pig farm and the chicken farm. (a) Shannon and Simpson indices; the bar represents the range of values. (b) PCA based on Bray–Curtis distance used to assess beta diversity. (c) Percentage of bacterial community abundance at the phylum level.

Bacterial community composition

-

The relative abundance of the bacterial community at the phylum level is shown in Fig. 4c. Analysis of the soil samples (PGC, P1, P2, CGC, C1, and C2) from pig and chicken farms revealed the presence of similar microbial communities, with the dominant phyla being Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteria. The Proteobacteria accounted for 20.3%–31.0% of the soil microorganisms, and Actinobacteria constituted 18.4%–38.0%. In the manure samples P3 and C3, Proteobacteria were the most abundant bacterial phylum, accounting for 39.1% and 64.0%, respectively, which were 1.6- and 2.1-fold higher than in the control soils. This finding aligns with numerous prior studies demonstrating that Proteobacteria is the predominant bacterial phylum in soil and manure samples from livestock farms, particularly in manure samples with higher proportions[46−48]. This phenomenon likely stems from the elevated abundance of Proteobacteria within the gut microbiota of farmed animals[49]. A notable observation was the divergence in the dominant bacterial phyla between yjr influent (storage tank, P4) and effluent (oxidation pond, P5) water samples. Comparative analysis demonstrated increased proportions of Proteobacteria (+12.5%; 18.8%–31.3%), Actinobacteria (+13.2%; 1.1%–14.3%), and Cyanobacteria (+42.4%; 0.3%–42.7%) in effluent samples compared with influent samples. Conversely, the abundance of Firmicutes drastically reduced from 38.3% to 0.1%. The synchronized sharp decrease in ARGs and Firmicutes in the P5 sample suggests that Firmicutes may be a key host for ARGs in pig farm samples. A substantial body of research has demonstrated that Firmicutes are potential hosts for ARGs and may be associated with a wide range of them[50−52].

Driving factors of ARGs' distribution

-

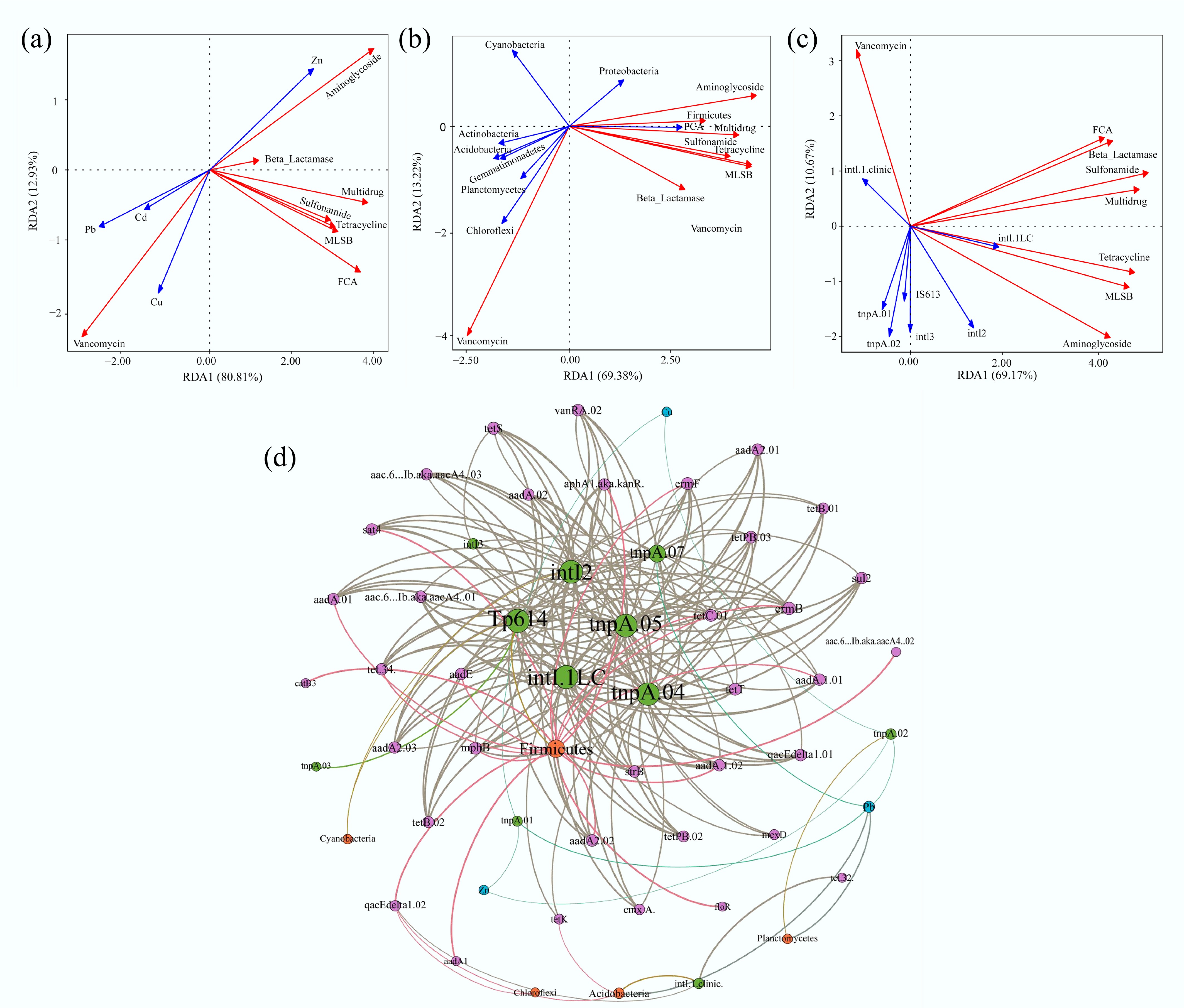

Redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed to investigate the drivers of ARGs' distribution across samples, focusing on heavy metals, bacterial communities, and MGEs (Fig. 5). The first two RDA axes collectively explained 80.0%–93.7% of the total variance. Correlation analysis between heavy metals and ARGs indicated that Zn (p = 0.004) was a significant factor influencing ARGs. Zn showed strong positive correlations with aminoglycoside resistance genes and most other ARG subtypes (excluding vancomycin resistance genes) (Fig. 5a). This finding is consistent with extensive literature indicating that metal contamination in the natural environment may play an important role in the maintenance and proliferation of ARGs[53−55]. Furthermore, a significant and positive correlation between heavy metal concentrations and the diversity and abundance of ARGs, with this correlation becoming more pronounced at elevated heavy metal concentrations[56], was corroborated by our data. In this study, soils with elevated concentrations of Cu and Zn exhibited a concomitant increase in the diversity and abundance of ARGs (Figs 2a, b & 3b).

Figure 5.

RDA and network analysis of the correlations among the samples collected from the selected farms. (a) Heavy metals vs. ARGs. (b) Bacterial phyla vs. ARGs. (c) MGEs vs. ARGs. The red arrows represent different types of ARGs. The blue arrows represent the factors that influence ARGs. (d) Network analysis reveals patterns of co-occurrence of ARGs, MGEs, heavy metals, and bacteria at the phylum level. Nodes and edges are colored according to the ARG classification. Node size is proportional to the number of connections, and edges are weighted according to the correlation coefficient. Connections showed strong (Spearman correlation coefficient > 0.7) and significant (p < 0.01) correlations.

Among the bacterial communities at the phylum level, Firmicutes (p = 0.007) and Chloroflexi (p = 0.003) were the bacterial phyla that significantly affected the abundance of ARGs, with Firmicutes being strongly correlated with FCA and multidrug resistance genes, and Chloroflexi mainly affecting the vancomycin resistance genes' relative abundance (Fig. 5b). The effect of MGEs on ARGs' abundance is shown in Fig. 5c. The results demonstrated that intI.1LC (p = 0.001) and intI2 (p = 0.003) were the significant MGEs affecting the relative abundance of ARGs and were positively correlated with most of the ARGs, with the exception of vancomycin resistance genes. The intI1 and intI2 genes are widely detected in fertilizers and field soils, and the widespread presence of Class 1 integrons may contribute to the accumulation and persistence of ARGs via HGT[57,58].

Correlation analyses were performed among heavy metals, bacterial taxa, MGEs, and the top 50 ARGs. Network modeling revealed complex interaction networks comprising 55 nodes and 200 edges (p < 0.01, Spearman's correlation coefficient > 0.70) (Fig. 5d). Most MGEs were associated with multiple ARGs, highlighting the complexity of their co-occurrence. For instance, intI2, intI.1LC, tnpA04, tnpA05, Tp614, and tnpA07 exhibited strong associations with various ARGs, including sulfonamides, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, FCA, MLSB, and other drug resistance genes. Furthermore, Firmicutes showed strong correlations with aadA, aadE, tetC, ermF, and ermB, suggesting their potential role as a primary reservoir of ARGs. Among the heavy metals, Cu, Zn, and Pb were not directly associated with ARGs but were associated with most MGEs. For instance, Pb significantly affected tnpA07, tnpA02, and tnpA01. The tnpA gene encodes a transposase, which is a core functional component of transposable elements. This activity indirectly promotes the spread of ARGs in bacterial populations by catalyzing the "cut-and-paste" mechanism of transposons, which mediates the lateral transfer and recombination of resistance genes[59]. The tnpA gene facilitates the movement and spread of ARGs through transposase activity. Therefore, the impact of soilborne heavy metals on ARGs is likely indirect, acting through their influence on MGEs (Fig. 5d). Collectively, our analyses identify Zn, the bacterial phyla Firmicutes and Chloroflexi, and MGEs (e.g., intI and tnpA) as key drivers of ARGs' distribution. The network analysis demonstrates an MGE-mediated dissemination pathway for ARGs, wherein heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Pb) indirectly promote ARGs' proliferation by enriching transposase-associated MGEs, rather than through direct correlation.

Distribution of risky ARGs, risk values, and influencing factors

-

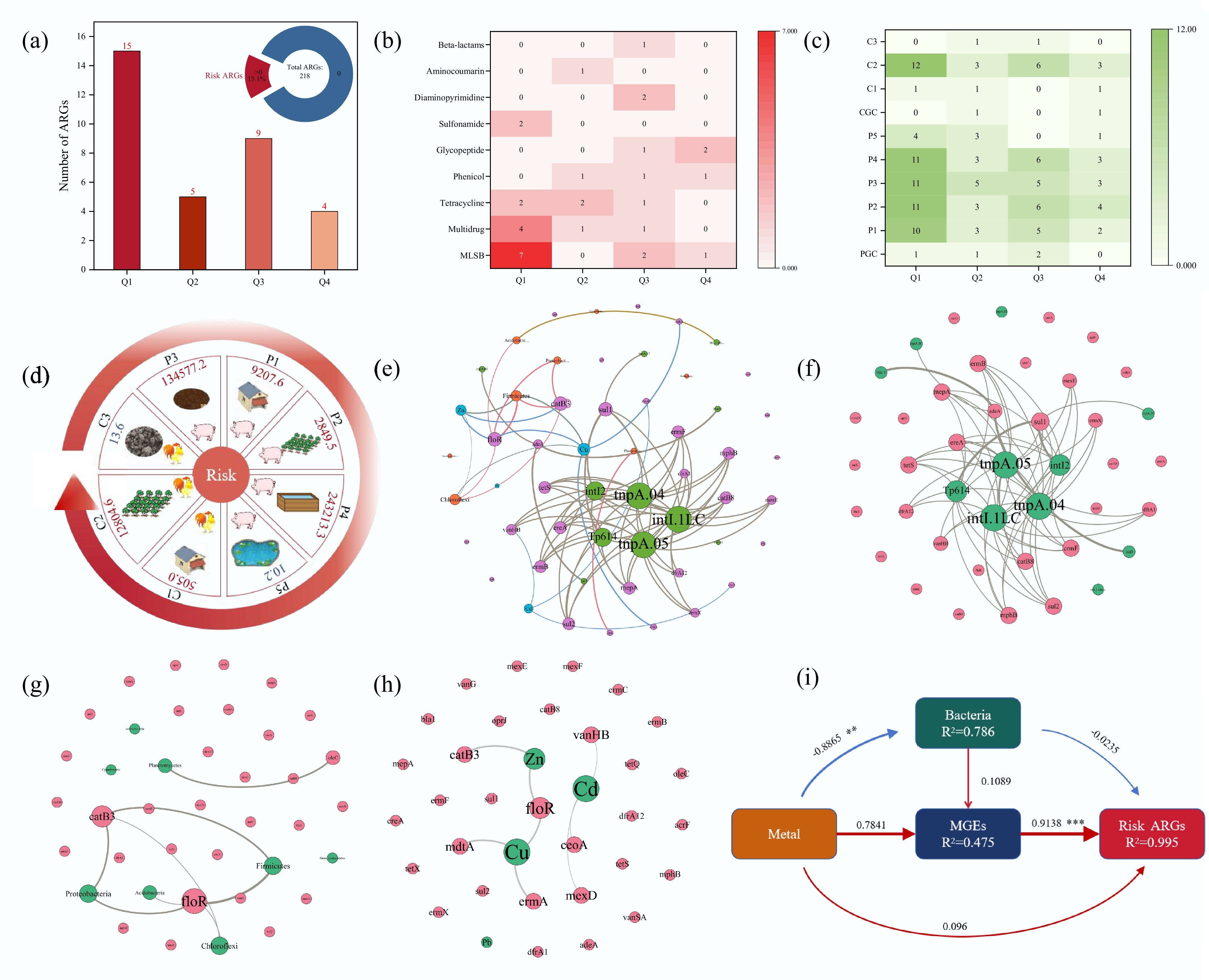

Following the framework established by Zhang et al.[26], we classified ARGs into four risk categories (Q1–Q4) and calculated their corresponding RIs, with detailed metrics provided in Supplementary Table S3. Among 218 ARGs detected in farm samples (Fig. 6a), 33 (15.1%) exhibited quantifiable risks: Q1 = 15, Q2 = 5, Q3 = 9, and Q4 = 4. MLSB resistance genes predominated (n = 10), followed by multidrug (n = 6) and tetracycline (n = 5) resistance (Fig. 6b). The risky ARGs contained in different samples were analyzed, and it was found that ARGs with risk level Q1 were detected the most in all samples (Fig. 6c). The most risky ARGs were detected in the chicken farm sample C2 (24 subtypes), and were also detected in large quantities in the pig farm samples P1, P2, P3, and P4, but they were rarely detected in the control group, suggesting that the farms increased the risky ARGs in the surrounding environment. It is worth noting that very few risky ARGs were detected in chicken manure fertilizer (C3) compared with those in pig manure fertilizer (P3).

Figure 6.

Risky ARGs in the samples and their influencing factors. (a) Detection rate of risky ARGs and the number of detected risky ARGs by risk ranking. (b) Different categories of risky ARGs. (c) Detection of risky ARGs in different samples. (d) Risk values for each sample. (e) Network analysis revealing patterns of co-occurrence of risky ARGs, MGEs, heavy metals, and bacteria at the phylum level. Correlation network diagram of (f) MGEs, (g) bacteria, and (h) heavy metals with risky ARGs. Nodes and edges are colored according to the ARGs' classification. Node size is proportional to the number of connections, and edges are weighted according to the correlation coefficient. Connections showed strong (Spearman correlation coefficient > 0.7) and significant (p < 0.01) correlations. (i) Influences on the risk level of ARGs were analyzed using PLSPM (**, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001).

To assess the potential human health risk from farm environments, we quantified the ARGs' RI for each sample (Fig. 6d; Supplementary Table S4). Both pig and chicken farms increased the abundance of high-risk ARGs in the surrounding soils. A striking disparity was observed between manures: The RI value for pig manure (P3) was 134,577.2, vastly exceeding that of dry chicken manure (C3, RI = 13.6). This indicates that reducing manure's water content can effectively mitigate the environmental and human health risks posed by ARGs. However, the RI value for the chicken manure-amended soil (C2) surged to 12,804.6, surpassing that of the pig manure-amended soil (P2, RI = 2,849.5). This demonstrates that even a low-risk manure can pose a high dispersal risk once introduced into the environment. Furthermore, the RI value of the treated wastewater (P5, 10.2) was dramatically lower than that of the influent (P4, 243,213.3), confirming the efficacy of oxidation ponds in reducing hazardous ARGs. We acknowledge that using relative abundance focuses on the genetic potential within the microbial community, whereas absolute abundance reflects the total environmental load. Future studies incorporating absolute quantification could provide complementary insights.

The main factors affecting the risky ARGs, including MGEs, bacterial communities, and heavy metals, were identified by network analysis (Fig. 6f–h). The results showed that intI.1LC, tnpA.04, and tnpA.05 were correlated with most of the risky ARGs. Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Zn showed a strong correlation with the resistance genes floR and catB3. VanHB, ceoA, and mexD were associated with Cd, whereas floR, ermA, and mdtA were associated with Cu. Most MGEs were strongly associated with multiple risky ARGs, whereas heavy metals and bacteria were associated with only a few of these risky ARGs (Fig. 6e). These results clearly demonstrate that the drivers of dissemination vary substantially across ARGs of different risk categories. Although MGEs serve as universal dissemination vehicles for risky ARGs across all risk categories, heavy metals and specific bacterial taxa exhibit distinct, risk-preferential associations. The broad connectivity pattern of MGEs suggests that HGT represents a fundamental mechanism facilitating the spread of diverse risky ARGs regardless of their specific risk classification. In contrast, the more selective associations of specific heavy metals with particular ARG subtypes, such as Cd with high-risk vancomycin resistance genes (VanHB) and Cu with moderate-risk efflux pump genes (mdtA), indicate that metal-specific co-selection pressures may preferentially enrich certain risk determinants. Similarly, the finding that Firmicutes and Proteobacteria showed stronger associations with moderate-risk ARGs (e.g., floR, catB3) suggests that the hosts' habitat range may be risk-dependent, potentially reflecting the ecological fitness costs associated with maintaining high-risk resistance determinants. This risk-stratified analysis provides critical insights for developing targeted intervention strategies: general measures to reduce the abundance of MGEs would broadly mitigate the potential for disseminating ARGs, whereas specific control of cadmium and copper pollution could preferentially reduce the selection pressure on high-risk and moderate-risk ARGs, respectively.

Partial least squares pathway modeling (PLSPM) was used to quantify the direct and indirect effects of drivers on risky ARGs. A pathway model was developed to explore the effects of heavy metals, bacterial communities, and MGEs on the distribution of risky ARGs (Fig. 6i). The goodness of fit (GOF) index was 0.73, indicating a model prediction accuracy of 73%. Heavy metals, bacterial communities, and MGEs accounted for 99.5% of the total variance explained (R2 = 0.995). MGEs had a direct and significant effect on risky ARGs (standardized path coefficient: 0.914), whereas heavy metals and bacteria did not. However, heavy metals significantly affected risky ARGs through MGEs (0.784). The results of the PLSPM analysis showed no strong direct association between microbial communities and risky ARGs, suggesting that the spread of ARGs is not driven by altered community structure but rather by HGT facilitated by heavy metals (Fig. 6i). Heavy-metal-induced horizontal transfer of ARGs is complex. First, co-tolerance occurs when heavy metals and specific ARGs are located on the same MGEs, and this physical linkage leads to co-option of other genes located on the same MGEs, which induces HGT and thus facilitates the spread of ARGs[20,60]. Secondly, there is also cross-resistance and co-regulation of heavy metals as a co-selection mechanism for maintaining and proliferating ARGs[20]. In addition, biofilm induction is one of the modes of co-selection of heavy metals with ARGs. Heavy metals can stimulate the production of extracellular polymeric substances, which leads to cell adhesion and ultimately to the formation of biofilms, which provide an ideal environment for the transfer of genes, thus facilitating the propagation of ARGs among organisms[20,61]. For instance, Guo et al.[62] reported that low concentrations of copper (12–22 mg/kg) and zinc (45–80 mg/kg) in dairy farm soils select for tolerant bacterial phyla (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria), thereby fostering a reservoir for ARGs and promoting their dissemination. In parallel, Wei et al.[63] provided a mechanistic insight, showing that Cu and Zn in biofilms directly facilitate the HGT of ARGs through co-resistance and cross-resistance pathways, while concurrently boosting vertical gene transfer by selecting for resistant bacteria. Heavy metals' promotion of HGT has also been demonstrated in a variety of environments, with Ni contamination in the soil increasing the frequency of conjugation transfer, and Hg2+ in water increasing the frequency of transformation[64,65].

This study found that ARGs' risk is co-determined by heavy metals, microorganisms, and MGEs. Unlike previous research focusing on single factors, our integrated approach—combining characterization of contamination, microbial community analysis, network analysis, and risk assessment—provides a comprehensive, quantitative evaluation of their inter-relationships. We show that heavy metals such as Zn and Cu indirectly drive the propagation of ARGs primarily by mobilizing MGEs (e.g., intI and tnpA), rather than through direct selection or changes in the microbial community. Moreover, by employing a quantitative risk index (RI) that accounts for ARG types and their mobility, we demonstrate that even manure with a low overall ARG abundance (e.g., dried chicken manure) can pose significant ecological risks if it contains high-risk ARGs associated with MGEs. These insights reveal that heavy metals facilitate the MGE-mediated HGT of ARGs, offering a new perspective for targeted mitigation. Our results emphasize the need to move beyond conventional indicators such as total ARG abundance and adopt integrated frameworks that assess the metal-driven transfer potential of specific, high-risk ARGs.

-

This study evaluated the contamination status and drivers of heavy metals and ARGs in soils adjacent to pig and poultry farms, and assessed the associated health risks posed by ARGs. The findings demonstrate that ARGs are co-driven by heavy metals, MGEs, and microbial communities, with MGE-mediated mechanisms playing a predominant role. Heavy metals indirectly influence ARGs through MGEs, whereas microbial communities provide biological niches for ARG hosts and proliferation. Among the samples analyzed, pig manure and manure slurry presented the highest ARG-related health risk values. Land application of manure contributes to the accumulation of both heavy metals and ARGs in the soil, thereby increasing the exposure risk of crops to these contaminants. Therefore, implementing effective livestock manure management practices is essential to curbing the spread of ARGs in agricultural ecosystems.

We would like to express our gratitude to Qian Lou, Liu Han, and Professor Jiayou Zhong from the Jiangxi Academy of Water Science and Engineering for their assistance with this work, and to Professor Min Qiao from the Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for her guidance in this project.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0007.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, investigation, writing – original draft: Liu W; methodology: Liu W, Zhou W, Fu C, Hou G, Zhang M; formal analysis, data curation: Liu W, Zhou W, Fu C, Hou G, Zhang M, He L; software: Hou G, Zhang M, He L; funding acquisition: Zhou W, Ding H; writing – review & editing: Zhou W, Yu J, Ding H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This study was supported by the Jiangxi Provincial Outstanding Youth Foundation Project (20224ACB214013) and the Key Project of Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20232ACB203023).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Pig farms disperse more heavy metals to adjacent areas than chicken farms.

Livestock farming increases the risk of ARGs in the surrounding soil.

Chicken manure fertilizer with low ARG risks still poses a high soil safety hazard.

Firmicutes strongly correlate with ARGs and are potential hosts.

Heavy metals indirectly affect risky ARGs by influencing MGEs.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Wenbin Liu, Wenguang Zhou

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Supplementary Table S1 Primer sets used in this study. FCA (fluoroquinolone, quinolone, florfenicol, chloramphenicol, and amphenicol), MLSB (Macrolide-Lincosamide-Streptogramin B), MGEs (mobile genetic elements).

- Supplementary Table S2 Heavy metal content in samples P4 and P5.

- Supplementary Table S3 Grading, RI values, and categorization of risky ARGs.

- Supplementary Table S4 Risk values for selected samples.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Proportion of each type of ARGs detected in samples (by type of antibiotic).

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Proportion of each type of ARGs detected in samples (by resistance mechanism).

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu W, Zhou W, Fu C, Yu J, Hou G, et al. 2025. Heavy metals and antibiotic resistance genes in large-scale livestock farming environments: pollution characteristics, driving factors, and risks to humans. Biocontaminant 1: e006 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0007

Heavy metals and antibiotic resistance genes in large-scale livestock farming environments: pollution characteristics, driving factors, and risks to humans

- Received: 29 July 2025

- Revised: 27 October 2025

- Accepted: 06 November 2025

- Published online: 18 November 2025

Abstract: The co-occurrence of heavy metals and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in livestock farming environments poses a substantial threat to ecosystem function and public health. This study systematically analyzed the distribution patterns of ARGs, heavy metals, mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and microbial communities in soils adjacent to representative pig and chicken farms near Poyang Lake, while identifying key drivers of ARGs' dissemination. Quantitative assessments revealed that pig farms contributed higher levels of heavy metals (e.g., Zn, Cu) to the surrounding soils than chicken farms. In contrast, ARGs were transferred to vegetable soils primarily through the application of manure, with the greatest enrichment and associated human health risks observed in plots amended with chicken manure. The risk index (RI) in chicken manure-fertilized soil surged to 12,804.6, representing a 941-fold increase over the original manure and a 16,006-fold increase over the control soil. These soils also harbored the highest diversity of risky ARGs, including tetracycline, sulfonamide, and multidrug resistance genes absent in the original manure. Mechanistic analysis indicated that heavy metals indirectly drive ARGs' proliferation through MGEs, with Firmicutes identified as a potential key host. These findings demonstrate that even low-risk organic fertilizers can pose significant safety concerns in agricultural ecosystems by facilitating the dissemination of ARGs. The results provide critical baseline data and mechanistic insights for developing targeted strategies to mitigate ARG contamination in livestock-affected agroecosystems.