-

Over the past few decades, global anthropogenic reactive nitrogen (N) loading has increased dramatically[1,2]. Estuaries serve as significant sinks for reactive nitrogen on a global scale[3−6], yet substantial anthropogenic inputs have led to widespread nitrogen pollution, including eutrophication and elevated nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions[7,8]. Denitrification, a microbially mediated process that reduces nitrate (NO3−) and nitrite (NO2−) to nitrogen gas (N2)[9], plays a crucial role in mitigating nitrogen eutrophication in estuarine and coastal ecosystems[4−6]. However, denitrification is also a significant source of N2O[9], a potent greenhouse gas approximately 300 times more effective than CO2 at warming the climate[10]. Consequently, understanding factors governing denitrification and N2O emissions in these sediments is vital for managing eutrophication and greenhouse gas fluxes.

Concomitantly, global antibiotic use has surged, leading to widespread detection of residues in natural environments[11−13], particularly in aquatic ecosystems[12,14]. Antibiotic overuse leads to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which has become a global health threat. AMR genes, known as biocontaminants, have rendered life-saving drugs ineffective against common infections, further directly undermining SDG 3's promise of health equity. Estuarine and coastal zones are primary receptors for anthropogenically derived biocontaminants and pharmaceutical pollutants[15]. These contaminants can alter sediment microbial community structure and function, potentially disrupting denitrification and stimulating N2O emissions[6,16−19]. Despite existing studies, the precise effects of antibiotics on denitrification remain poorly constrained[20,21]. For instance, sulfamethoxazole (SMX) has exhibited both inhibitory and stimulatory effects on denitrification[16,17,22−26], while triclosan and triclocarban have shown concentration-dependent effects[27]. Furthermore, temporal dynamics are evident, with antibiotics often initially inhibiting but later promoting denitrification[28]. Similarly, antibiotics frequently enhance N2O emissions[6,17,26], although the effects depend on exposure duration and concentration[22,29]. This inconsistency underscores the need for further research to clarify the impacts of antibiotics in estuarine and coastal ecosystems.

DNA stable isotope probing (DNA-SIP) enables direct identification of active functional microbes assimilating specific substrates labeled with stable isotopes (15N or 13C) into their biomass[30]. This technique has successfully identified microorganisms actively degrading pollutants, including phenanthrene (PHE), triclosan, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)[31−33]. Recently, DNA-SIP has also been characterized in situ in aerobic and anaerobic SMX-degrading bacteria within activated sludge and soils[34−37]. However, degraders vary across environments[31], and the identity and activity of antibiotic-degrading bacteria in estuarine sediments remain largely unexplored. Critically, the potential linkage between these degraders and denitrifying bacteria is unknown.

The Yangtze River Estuary is heavily contaminated with antibiotics, with sulfonamides predominating[38,39]. Therefore, this study investigated the common sulfonamide SMX, using sediment slurry incubations combined with 15N tracer analysis to quantify its effects on denitrification rates and N2O emissions. Bacterial community composition, functional potential, and abundances of denitrification (nirS, nosZ) and resistance (sul1) genes were further analyzed to elucidate microbial mechanisms. Crucially, DNA-SIP with 13C-SMX was applied to identify active SMX-degrading bacteria and examine their relationship with denitrifying communities. This study aims to disentangle the link between SMX-degrading bacteria and denitrifiers, thereby deepening understanding of the effects of antibiotics on nitrogen removal in estuarine and coastal regions.

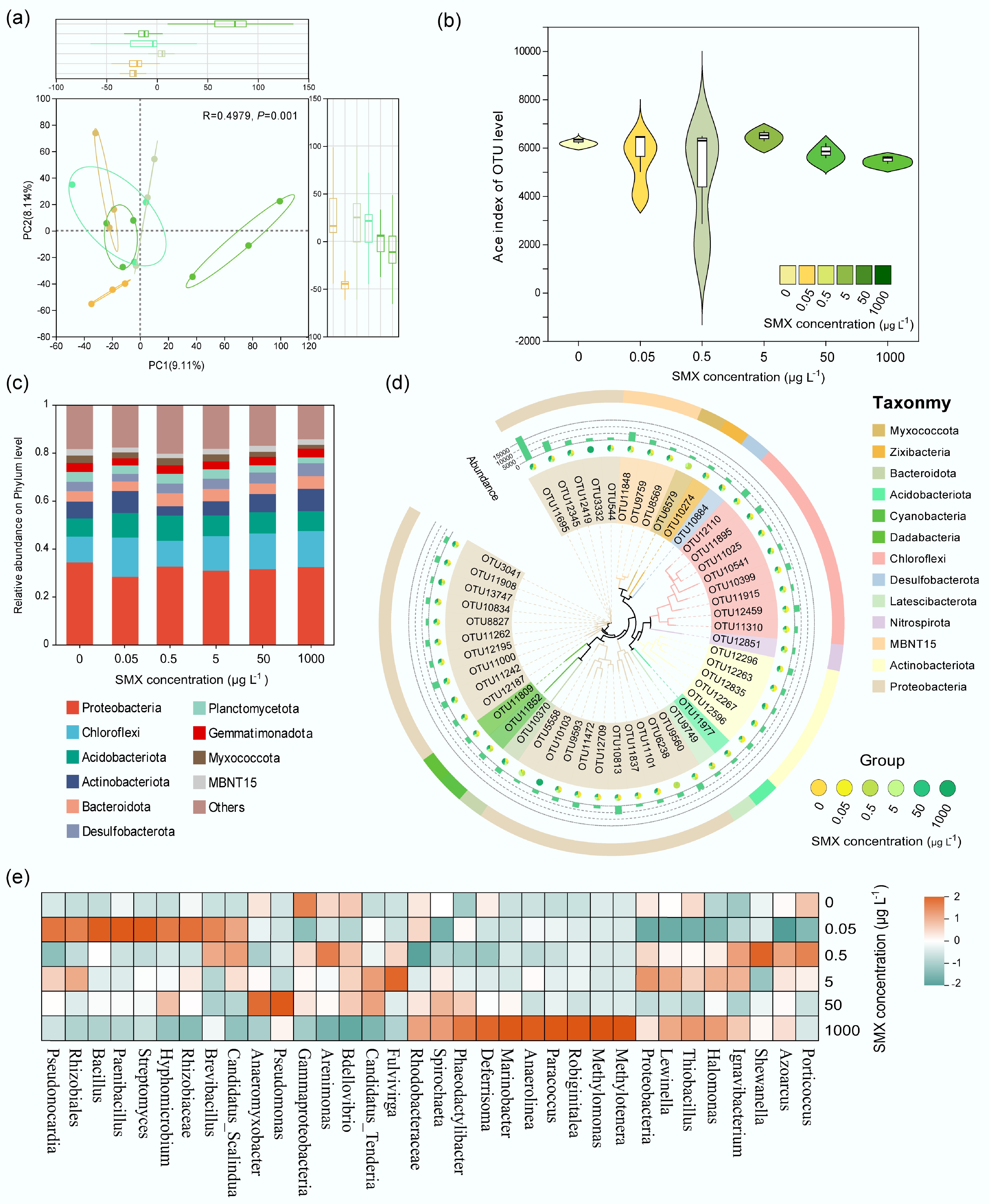

-

The study area is located in the East Tidal Flat Wetland of the Yangtze River Estuary (China), one of the largest estuaries in the world (Supplementary Fig. S1). Sediment samples were collected in November 2022 from the intertidal zone of the Yangtze River Estuary Wetland. Briefly, during low tide, surface (0–5 cm) sediment was collected from five plots (10 m × 10 m each) using a sterile stainless-steel shovel, and stored in sterile plastic bags. Additionally, on-site overlying water was collected using 10 L polyethylene buckets for subsequent incubation. Following collection, all samples were refrigerated (4 °C) and transported to the laboratory as soon as possible. Subsequently, all sediment samples were homogenized and divided into two sub-samples in the laboratory. One sub-sample was stored at −20 °C for the analysis of sediment physicochemical properties. Detailed sediment physicochemical properties and measurement methods are provided in Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and Supplementary File 1 (Method 1.1). The other sub-sample was preserved at 4 °C for the microcosm incubation experiment.

Sediment incubation experiments

-

In the laboratory, surface sediment was pre-incubated at 20 °C for approximately 2 months to reduce SMX levels below detection limits[6]. Subsequently, a sediment gradient slurry experiment with SMX was conducted. Wet sediment samples (200 g) were mixed with filtered, aerated in-situ water at a ratio of 1:2 (weight/wet weight) in 500 mL amber glass bottles with polytetrafluoroethylene-lined stoppers. The environmental concentrations of SMX were reported to range from 2.2 to 764.9 ng L−1 in the study area[40], whereas therapeutic concentrations can exceed 1 mg L−1[41]. Therefore, SMX was added to final concentrations of 0 (blank), 0.05, 0.5, 5 μg L−1 (environmental concentrations), and 50, 1,000 μg L−1 (therapeutic concentrations). The glass bottles were immediately sealed and purged with helium to establish anaerobic conditions favorable to denitrifiers, then incubated in the dark at 20 °C for 30 d. Six samples were taken for each treatment using a destructive sampling method during days 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 of the incubation, with three replicates at each sampling time. A total of 18 glass bottles were prepared for each treatment (six sampling times, each with three replicates). Each sediment sample was divided into two parts: one for determining denitrification and N2O emission rates using15N isotopes, and the other for DNA extraction and measurement of sediment physicochemical properties.

Measurement of denitrification and associated N2O emission rates

-

Denitrification rate was measured using the 15N isotope-tracing method[6]. Following cultivation, the sediment was mixed with artificial seawater at a ratio of 1:7. Approximately 30 min of helium gas purging was employed to remove dissolved N2 and O2. Subsequently, the precipitated slurry was transferred into 12 mL gas-tight borosilicate vials and pre-incubated in darkness for 48 h. After pre-incubation, all slurry samples were spiked with 100 μL of 15N-NO3− (99% 15N), and half were immediately quenched with 100 μL of ZnCl2 solution to halt microbial activity. The remaining half was quenched after 8 h. Detailed information on the calculation of denitrification rates is provided in Supplementary File 1 (Method 1.2).

In the process of determining denitrification rates, simultaneous slurry culture experiments were conducted to measure N2O emission rates. After incubation, dissolved N2O was measured using the headspace equilibration technique. Three mL of ultra-high purity nitrogen gas was injected into each 12 mL vial to replace the aqueous phase and generate headspace. The vials were vigorously shaken for 1 h to equilibrate the gas and liquid phases. Subsequently, headspace gas was extracted using a syringe, and N2O concentration was measured by gas chromatography (Shimadzu GC-14B), with a detection limit of 0.1 nL L−1. The Henry's coefficient at the measured temperature, after equilibration, and the measured N2O concentration in the headspace was used to estimate the total N2O concentration in the sediment slurry[42]. N2O production rates were calculated from changes in N2O concentration during the incubation period, following the method of a previous study[6]. Detailed information on the calculation of N2O emission rates is provided in Supplementary File 1 (Method 1.3).

Antibiotic degradation and SIP incubation experiments

-

The experiment comprised three treatments: (1) utilizing gamma-irradiated sediment blended with sterilized water and 12C-SMX as an abiotic degradation control; (2) sediment blended with in situ overlying water and 12C-SMX; and (3) sediment blended with in situ overlying water and 13C-SMX (purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., China) for chemical analysis. To establish microcosms, wet sediment samples (200 g) were mixed with filtered and aerated in situ overlying water at a ratio of 1:2 (weight/wet weight) in 500 mL brown glass bottles fitted with PTFE-lined caps. SMX was added to final concentrations of 1,000 μg L−1 each. The bottles were promptly sealed and flushed with helium to induce anaerobic conditions. Figure 1 illustrates the precise SMX concentrations for all treatments on day 0. As previously detailed[6], 1 mL of slurry was extracted from each sample using a syringe on days 1, 3, 5, 10, 14, 23, and 30 post-incubation for SMX concentration analysis. SMX concentrations were determined using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). SIP culture experiments were conducted using the aforementioned culturing method to identify active SMX degraders in sediment blended with either 12C-SMX or 13C-SMX. 15N-NO3− was also spiked to resemble the incubation for measuring denitrification rates. No other carbon source was added during the microcosm experiment. Sediment samples were collected upon achieving an 80% SMX removal percentage for DNA extraction and molecular analysis. Comparisons and differential analyses of sequencing results between 13C- and 12C-labeled DNA were conducted to identify the main bacterial groups involved in the degradation/assimilation of SMX[31].

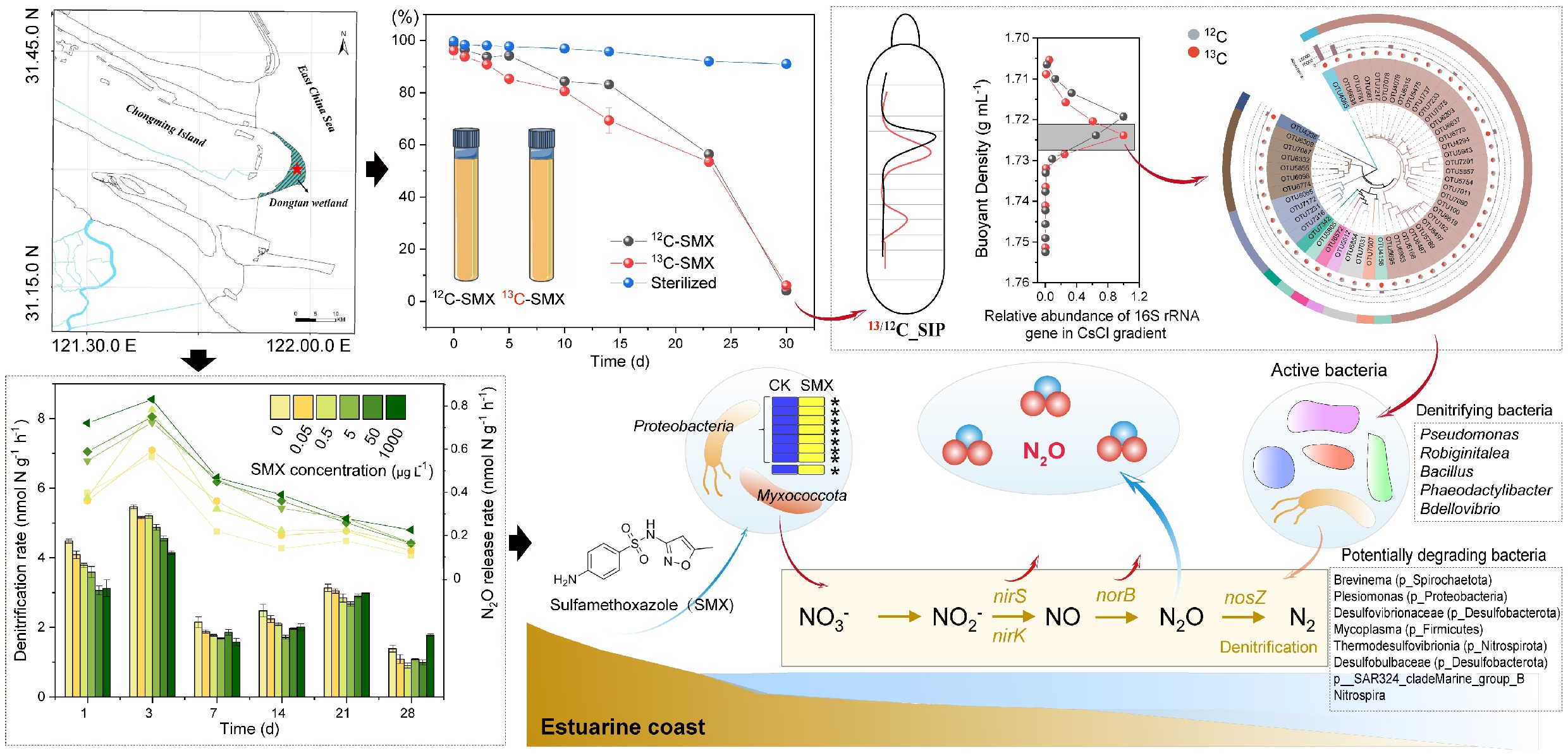

Figure 1.

Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) degradation dynamics and effects on denitrification and N2O emissions. (a) Degradation of 13C- and 12C-SMX in active vs sterilized sediments over 30 d. Time-course changes in (b) denitrification rates, and (c) N2O release under SMX gradients (0–1,000 μg L−1). (d) Time-course changes in denitrification rates and N2O release among blank (0), environmental concentrations (0.05–5 μg L−1), and therapeutic concentrations (50–1,000 μg L−1). Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3). Lowercase letters denote significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

DNA extraction and quantitative PCR

-

Total DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of sediment using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentrations and purity of DNA were measured using a NanoDrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The abundances of the 16S rRNA gene, the denitrification functional genes (nirK, nirS, and nosZ), and sulfonamide resistance genes (sul1, sul2) were quantified by the ABI7500 Sequence Detection System. The primers and qPCR thermal conditions are provided in Supplementary Table S3. A standard curve for each target gene was constructed using 10-fold serial dilutions of the plasmid DNAs. The correlation coefficients (R2) were all > 0.99, and all amplification efficiencies ranged from 90% to 110%. All qPCR assays were performed in triplicate.

DNA fractionation

-

According to the DNA-SIP protocol[43], the DNA from 12C- and 13C-SMX-treated samples were separated by CsCl density-gradient ultracentrifugation. Initially, 2.5 μg of DNA was mixed with CsCl solution (1.85 g mL−1) and GB buffer (pH = 8.0, 0.1 mol L−1 Tris-HCl, 0.1 mol L−1 KCl, 1.0 mmol L−1 EDTA) to achieve a final buoyant density of 1.725 g mL−1. Subsequently, the mixture was loaded into 5.1 mL polyallomer ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman), sealed, and centrifuged at 45,000 rpm (190,000 × g) for 48 h at 20 °C. The centrifugation gradient was fractionated into 15 equal-volume fractions containing DNA. Buoyant density was measured using an AR 200 handheld refractometer (Reichert), and the DNA fractions were further purified by gradient purification using polyethylene glycol (PEG-6000). Subsequently, the DNA was washed three times with 70% ethanol and stored at −20 °C in a 30 µL DES (deep eutectic solvents) buffer. The recovery efficiency of DNA reached approximately 60%[44]. The purified DNA was then subjected to quantitative analysis of 16S rRNA, nirS, sul1, and sul2 gene abundance. DNA fragments containing the highest abundance of the 16S rRNA genes from the 12C- and 13C-SMX incubated experiments were selected, and the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primer pair 338 F/806 R[45]. The key species in this study were identified based on differences in microbial abundances between the 12C- and 13C-SMX groups from the DNA-SIP results[46]. The microbial groups with significant differences were identified as active microbial communities (key species) involved in SMX metabolism (p < 0.05).

High-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene

-

High-throughput sequencing was used to investigate the composition of the bacterial community; the V3 and V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified with primer pairs 338F (5'-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3'), and 806R (5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3') by an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 PCR thermocycler (ABI, CA, USA). Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity cutoff. Using a Bayesian algorithm, the RDP classifier was applied to classify each representative OTU sequence at the phylum and genus levels. Detailed information is given in Supplementary File 1 (Method 1.4). The raw reads were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under Accession No. PRJNA1241457.

Statistical analysis

-

SPSS 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA), and Origin 2024 were applied for statistical analyses and graphing. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the significant differences with p < 0.05. Correlations between variables were analyzed with Pearson's correlation. Alpha diversity indices (Chao1 richness, Shannon diversity) were calculated using the vegan package to assess within-sample microbial diversity. Beta diversity analysis was conducted using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices and visualized using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA). PERMANOVA was used to assess differences in microbial communities. Co-occurrence networks of microbes were constructed using Spearman correlation (r > 0.7, p < 0.01), and visualized in Cytoscape. Functional shifts were evaluated by redundancy analysis (RDA), and differential expression profiling. Raw sequencing data were processed using QIIME 2 (version 2023.9). Briefly, sequence quality control, denoising, chimera removal, and merging of paired-end reads was performed with the DADA2 plugin to generate a table of operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The phylogenetic investigation of the microbial community's metabolic potential was inferred using PICRUSt2 (version 2.5.0). The OTU representative sequence file (FASTA) and the OTU abundance table (BIOM format) generated from QIIME 2 served as the input. The standard PICRUSt2 pipeline was executed, which involves placing OTUs into a reference tree, predicting hidden-state gene family abundances, and inferring pathway abundances based on the MetaCyc database.

-

In both 12C- and 13C-SMX treatments, SMX concentrations decreased progressively over the cultivation period, reaching removal rates of approximately 80% by day 28, and 94% and 96% by day 30, respectively (Fig. 1a). No significant difference in SMX concentrations between 12C- and 13C-SMX was observed in this study. As incubation was conducted in the dark, photodegradation was not considered in this study. In the sterile treatment, SMX residual concentrations remained above 90% and decreased slightly within 30 d (Fig. 1a), confirming microbial biodegradation as the primary removal pathway and indicating that SMX was biodegraded during biological treatment, with sediment microorganisms playing a significant role in its removal.

Denitrification rates ranged from 0.90 to 5.46 nmol N g−1 h−1 (Fig. 1b). Rates in all groups rose gradually during days 1–3 and 7–21, then significantly declined from days 21–28 (p < 0.05). Compared with controls, SMX significantly suppressed denitrification rates during days 1–14 (p < 0.05), with inhibition rates ranging from 4.75% to 36.61%. During days 1–3, therapeutic concentrations of SMX inhibited denitrification rates more significantly than environmental concentrations, but the inhibition rates resembled between the two concentration groups during days 7–14 (Fig. 1d). Moreover, denitrification rates exhibited a concentration-dependent U-shaped trend during days 21–28 (Fig. 1d). By day 28, SMX at 0.05–50 μg L−1 inhibited potential denitrification rates (p < 0.05), while 1,000 μg L−1 promoted denitrification rates (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b).

N2O emission rates ranged from 0.11 to 0.83 nmol g−1 h−1. Rates peaked during days 1–3 before significantly decreasing from days 3–28 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1c & d). SMX exposure significantly increased N2O emission rates by 5.43%–178.61% (p < 0.05), with significant inter-group variation.

Abundances of N transformation functional genes and antibiotic resistance genes

-

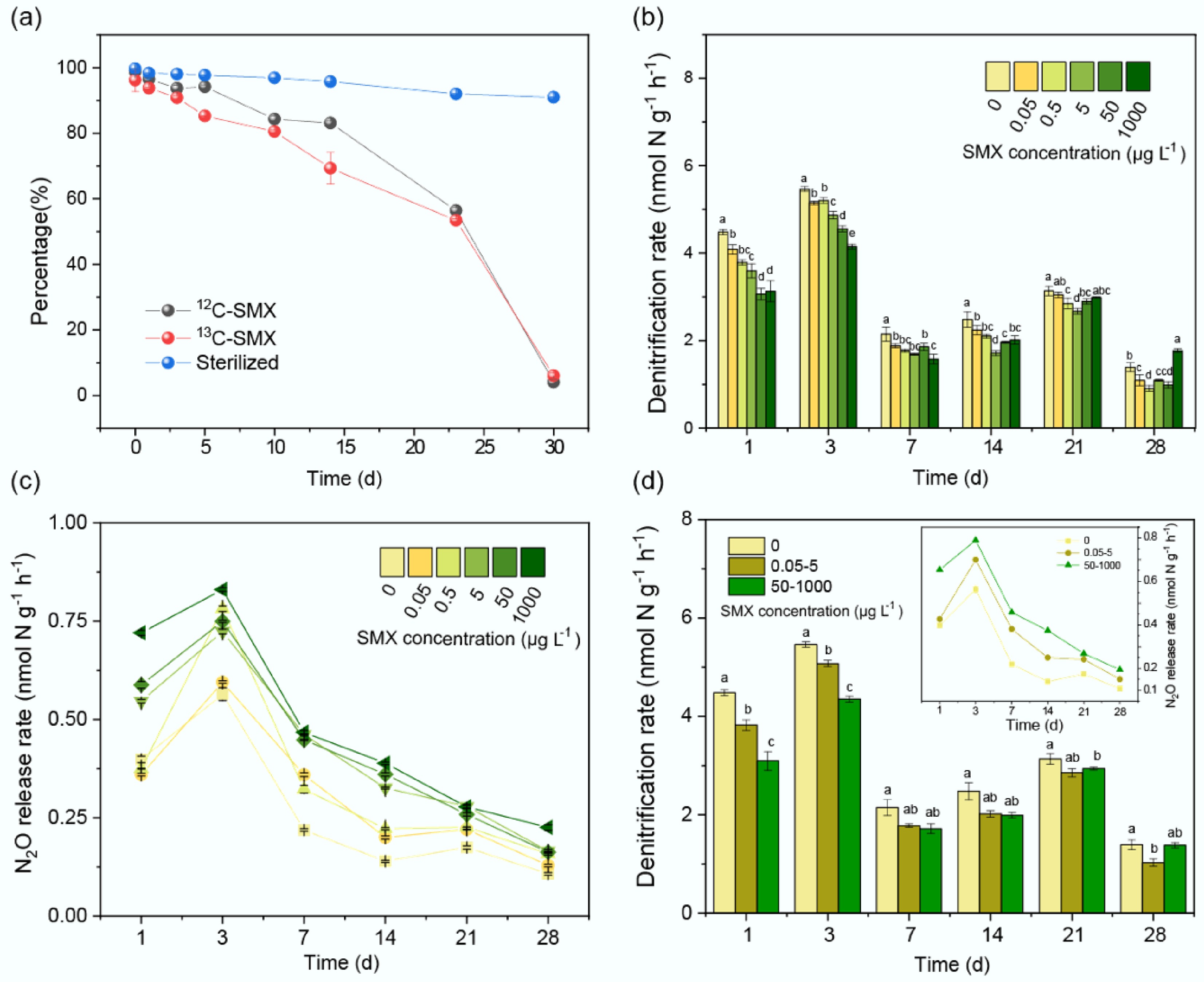

On day 1, the abundances of nirS, nirK, and nosZ genes in the SMX treatments were modestly reduced compared to controls (Fig. 2). From days 3 to 14, SMX significantly decreased gene abundances (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, on days 21–28, a weak U-shaped trend emerged in gene abundances. The abundance of sulfonamide resistance genes sul1 and sul2 rose over time (p < 0.05), and were significantly elevated relative to controls from days 3–28 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

SMX effects on denitrification and sulfonamide resistance gene abundances. Temporal changes in (a) nirS, (b) nirK, (c) nosZ, and (d) sul2 gene copy numbers across SMX concentrations (0–1,000 μg L−1). Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3). Lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Effects of SMX contamination on microbial community structure and diversity

-

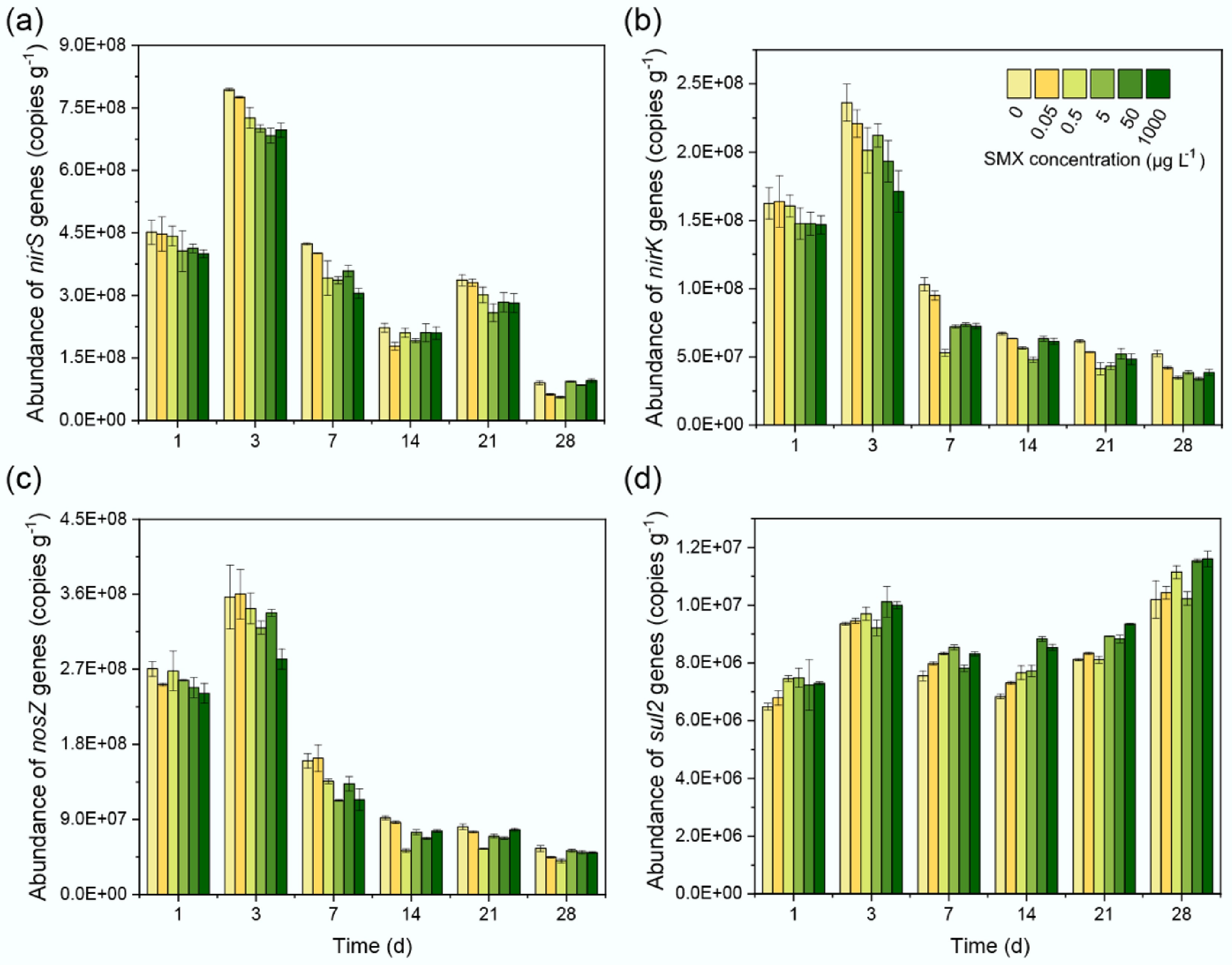

High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing under SMX gradients revealed significant community separation via PCoA (Bray-Curtis; R = 0.4979, p = 0.001; Fig. 3a). Microbial richness (ACE index) showed a unimodal response to SMX: stimulated at 0.05–5 μg L−1 but suppressed at 50–1,000 μg L−1 (Fig. 3b). At the phylum level, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota increased with moderate SMX levels, while Acidobacteriota and Chloroflexi declined under high-dose exposure (Fig. 3c). Notably, Myxococcota and Planctomycetota were sensitive to low concentrations. LEfSe identified 34 SMX-sensitive OTUs (Fig. 3d), with Actinobacteriota and Desulfobacterota suppressed under high SMX, while select Bacteroidota and Proteobacteria OTUs were enriched. Genus-level analysis revealed SMX-driven shifts in key taxa (Fig. 3e): Bacillus, Pseudolabrys, and Streptomyces increased at low-moderate SMX, whereas nitrifiers (e.g., Nitrosomonadaceae) and sulfate reducers (e.g., Desulfobulbus) were inhibited at high concentrations.

Figure 3.

SMX-driven shifts in sediment bacterial communities. (a) PCoA (Bray-Curtis) showing community separation by SMX (PERMANOVA, R = 0.4979, p = 0.001). (b) ACE index (richness) response to SMX concentration. (c) Phylum-level composition highlighting Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Chloroflexi. (d) Phylogenetic cladogram of SMX-sensitive OTUs (LEfSe; p < 0.05). (e) Heatmap of SMX-responsive genera; color = log-fold change vs control.

Functional profiling of active microbial communities under SMX

-

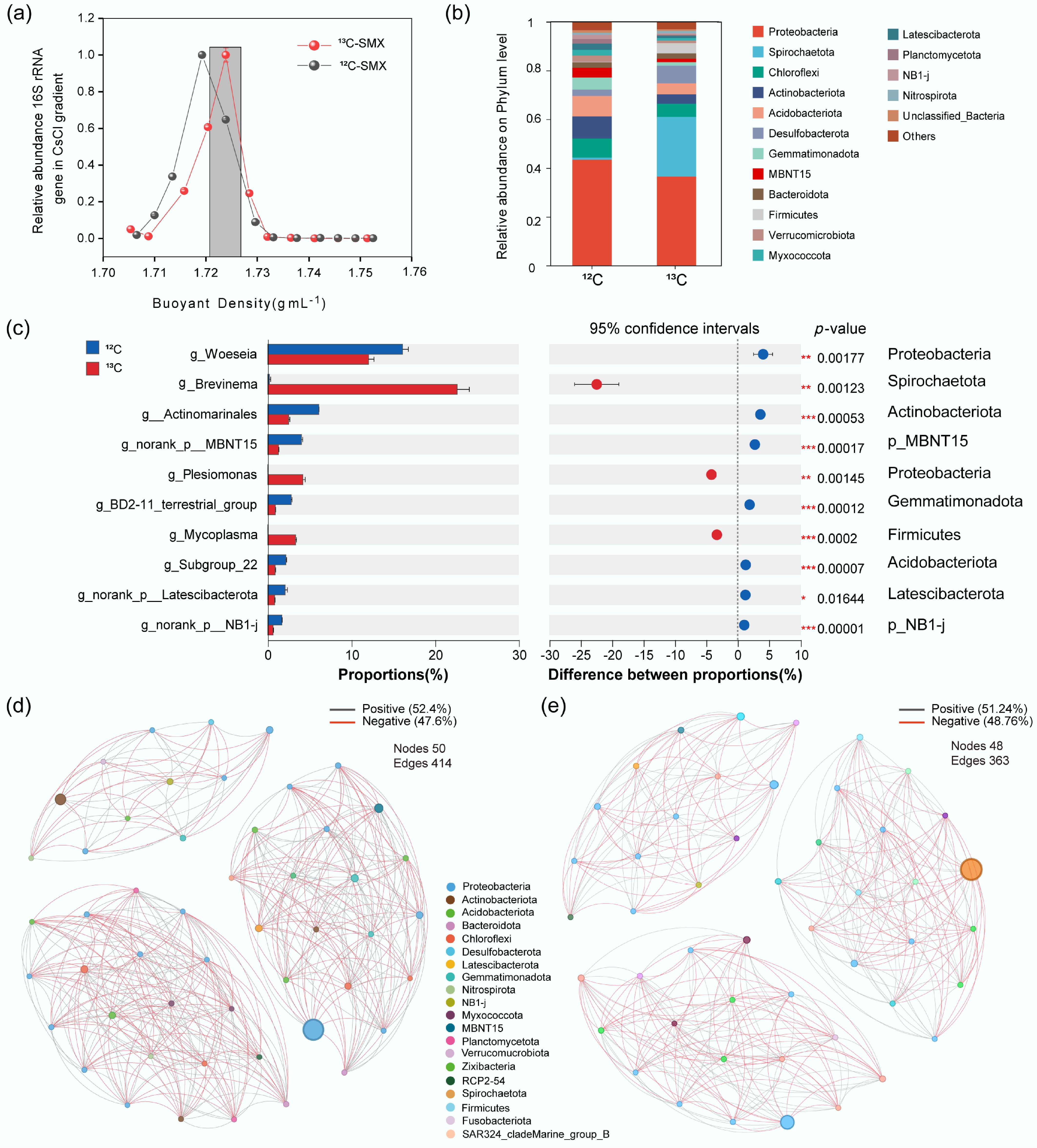

DNA-SIP revealed active microbes assimilating 13C-SMX, with 13C-DNA enriched at ~1.725 g mL−1 (vs 1.720 g mL−1 for 12C; Fig. 4a). Active communities (13C) showed higher proportions of Brevinema (p_Spirochaetota), Plesiomonas (p_Proteobacteria), Desulfovibrionaceae (p_Desulfobacterota), Mycoplasma (p_Firmicutes), Thermodesulfovibrionia (p_Nitrospirota), Desulfobulbaceae (p_Desulfobacterota), p__SAR324_cladeMarine_group_B, and Nitrospira (Fig. 4b). Differential abundance analysis identified Proteobacteria (g__Plesiomonas), Spirochaetota (g__Brevinema), and Firmicutes (g__Mycoplasma) as significantly enriched in 13C fractions (p < 0.001; Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Active SMX-assimilating taxa and microbial interactions identified by DNA-SIP. (a) Relative abundance of 16S rRNA gene in CsCl density fractions (13C- vs 12C-SMX). (b) Phylum composition of 13C- and 12C-labeled DNA. (c) Differentially enriched genera and phyla in 13C-DNA; bars = mean abundance, diamonds = proportional difference (*** p < 0.001). Co-occurrence networks for (d) 12C-, and (e) 13C-communities. Nodes: taxa (phylum-colored); edges: positive (gray)/negative (red) correlations.

Co-occurrence networks demonstrated substantial negative interactions (47.6% 12C; 48.76% 13C; Fig. 4d, e). The 13C network had fewer edges (n = 363 vs 414 for 12C) and reduced connectivity. Keystone taxa (e.g., Actinobacteriota, Desulfobacterota) were central hubs in the 13C network.

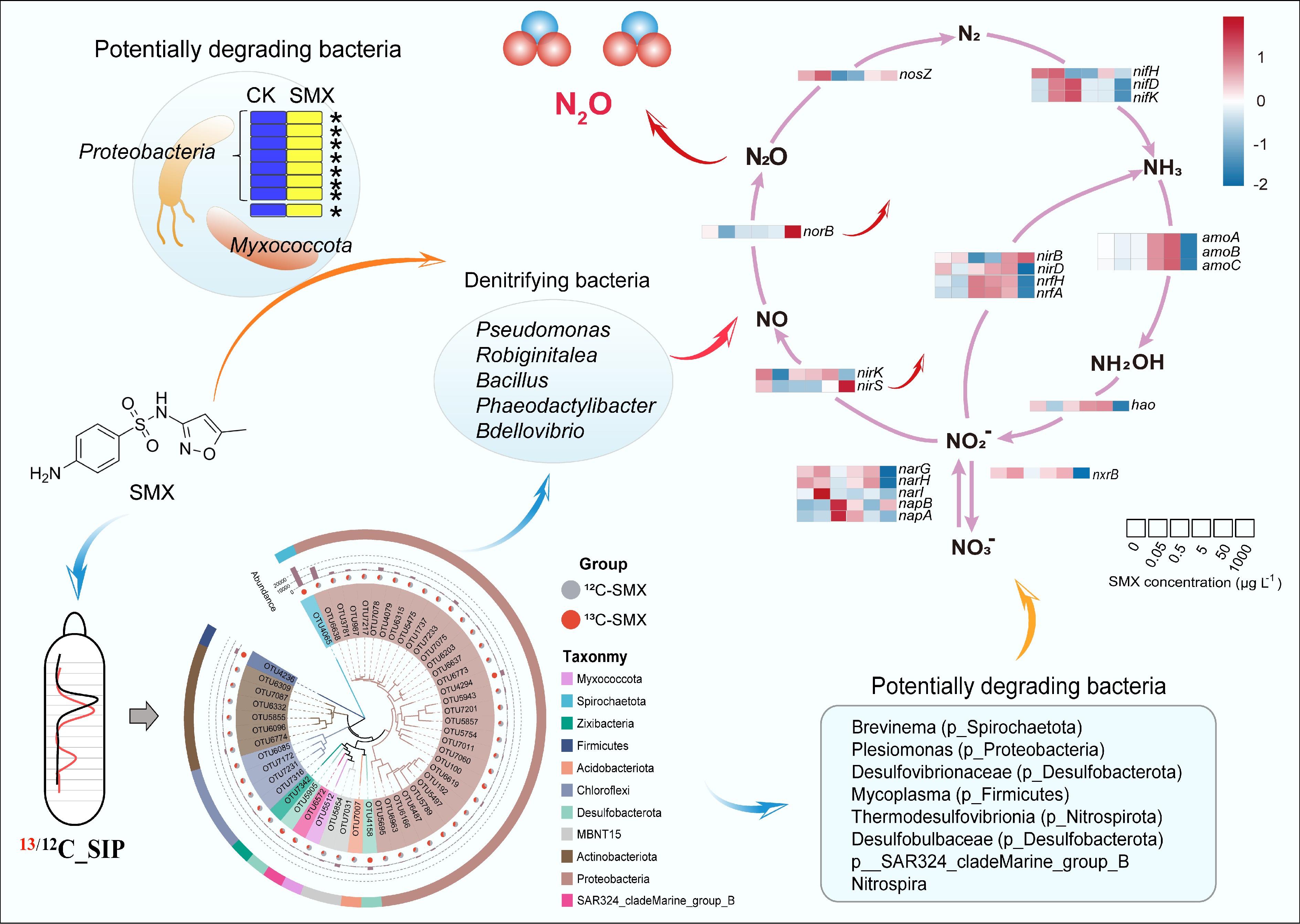

Based on PICRUSt2 functional predictions, SMX disrupted N cycling pathways in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S4). The therapeutic concentrations of SMX inhibited nitrate reductase (nar) and nitrite reductase (nirK/nirS) more severely than environmental concentrations, while promoting nitric oxide reductase (norB) and nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) more significantly. Therapeutic concentrations of SMX also inhibited nitrogen fixation (nif), nitrification (amo, hao, and nxr), dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (nrfA/H), and assimilatory nitrate reduction (nirB/D). On the other hand, environmental concentrations of SMX can promote nitrification, dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium, and assimilatory nitrate reduction.

Figure 5.

Mechanistic link between active SMX-degrading bacteria and denitrification. (Center) DNA-based stable isotope probing (DNA-SIP) with 13C-SMX identified denitrifying bacteria (Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Bdellovibrio) as primary assimilators of the antibiotic. (Upper left) Dominant bacterial phyla responsible for SMX assimilation (Proteobacteria, Myxococcota). (Bottom center) Phylogenetic distribution of 13C-enriched operational taxonomic units (OTUs), highlighting additional key degraders (Spirochaetota, Desulfobacterota). (Right) Heatmap showing SMX concentration-dependent responses of key nitrogen (N) cycling genes, linking antibiotic stress to disrupted N-cycling pathways. The genes analyzed include those for nitrogen fixation (nif, nitrogenase), which converts dinitrogen gas to ammonia; nitrification (amo, ammonia monooxygenase; hao, hydroxylamine oxidoreductase; nxr, nitrite oxidoreductase), which oxidizes ammonia to nitrate; the complete denitrification pathway (nar, nitrate reductase; nirK/nirS, nitrite reductase; norB, nitric oxide reductase; nosZ, nitrous oxide reductase), which reduces nitrate to dinitrogen gas; dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) (nrfA/H, cytochrome c nitrite reductase complex), which reduces nitrite to ammonia; and assimilatory nitrate reduction (nirB/D, assimilatory nitrite reductase), which incorporates nitrogen into biomass.

Correlations between microbial parameters and process rates

-

Pearson analysis showed that denitrification rates were positively associated with Anaerolinea, Deferrisoma, Marinobacter, Methylomonas, Methylotenera, Paracoccus, Robiginitalea, and nirS gene abundance (p < 0.01), but negatively associated with TOC. N2O emissions correlated positively with Anaerolinea, Deferrisoma, Ignavibacterium, Marinobacter, Methylomonas, Methylotenera, Paracoccus, Phaeodactylibacter, Robiginitalea, NH4+, nirS/nosZ, nirK/nosZ, sul1, and sul2, and negatively with TOC and nosZ. Denitrifiers Ignavibacterium correlated with sul1, while Marinobacter, Phaeodactylibacter, and Pseudomonas associated with sul2 (Supplementary Figs S3−S5).

-

Antibiotics in estuarine and coastal ecosystems pose significant risks to microbially mediated nitrogen cycling[6,16−19]. Combining 15N tracings and DNA-SIP, this study elucidated SMX effects on denitrification, N2O emissions, and associated microbial mechanisms. Key findings reveal a time-dependent denitrification response to SMX, accompanied by substantially enhanced N2O emissions.

While denitrification removes reactive nitrogen from these sediments, it simultaneously emits N2O[4,5]. Our previous work showed that SMX can alter N2O production pathways and induce N2O release via denitrification in estuarine sediments[16]. In this study, the data demonstrates that SMX significantly increases the risk of N2O emissions (Fig. 1c). As N2O is a denitrification intermediate[26], its net emission reflects the balance between production (nirS/nirK), and reduction (nosZ). SMX disproportionately inhibited nosZ, and N2O emissions correlated positively with nirS/nosZ and nirK/nosZ ratios (Supplementary Fig. S5). Thus, by impairing N2O reduction more severely than production, SMX amplifies N2O release. This aligns with prior observations of antibiotic-induced N2O via unbalanced nirS-nosZ inhibition[6,17,18,22], converting reactive nitrogen into a potent greenhouse gas[5]. In this study, both environmental and therapeutic concentrations of SMX promoted N2O emission distinctly (Fig. 1d). Numerous studies have demonstrated that environmentally relevant residual concentrations of antibiotics (e.g., sulfonamides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones) can significantly alter the structure and function of microbial communities in soil and aquatic ecosystems[47]. These alterations profoundly impact the nitrogen cycling process through multiple mechanisms: the inhibition of sensitive microorganisms (including key bacterial species involved in complete denitrification), the selective proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and the disruption of gene expression and enzymatic activity of critical nitrogen-transforming enzymes (such as Nar, Nir, Nor, and Nos)[48]. Of particular concern is the observation that antibiotic exposure frequently disrupt the denitrification pathway, leading to a 'truncation' characterized by the specific inhibition of the N2O reduction step (catalyzed by the Nos enzyme), or a relative increase in N2O production pathways[49]. This is also supported by the functional prediction of PICRUSt2 in this study (Fig. 5). SMX exposure, especially therapeutic concentrations, inhibited nitrate reductase (nar) and nitrite reductase (nirK/nirS) while promoting nitric oxide reductase (norB) and nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ), which illustrated that gene expression and enzymatic activity of N2O production and reduction enzymes were disrupted. This disruption results in elevated N2O accumulation and increased emission fluxes.

Denitrification displayed biphasic kinetics (Fig. 1). During the initial exposure (days 1–14), SMX continuously inhibited denitrification, consistent with acute antibiotic toxicity[17,50]. Mechanistically, SMX disrupts folate biosynthesis—essential for nucleotide synthesis—impairing denitrifier growth and gene expression[6,50]. Subsequently (days 21–28), inhibition weakened concomitantly with SMX degradation, yielding a U-shaped response (Fig. 1d). Compared to the control group, it is worth noting that the environmental concentrations of SMX inhibited denitrification rates throughout the 30-d incubation. In contrast, therapeutic concentrations of SMX even promoted denitrification rates at day 28. Similar biphasic patterns occur with triclosan/triclocarban[16,25,27], and high SMX (> 50 μg L−1) can stimulate denitrification under low nitrate/carbon conditions[51]. As denitrifiers are facultative heterotrophs that require organic carbon for nitrate reduction[20,52], and SMX can serve as a carbon source for genera such as Achromobacter and Pseudomonas[53,54], we propose that SMX biodegradation via co-metabolism with nitrate as the electron acceptor drove the observed late-phase stimulation[55].

DNA-SIP identified Spirochaetota, Desulfobacterota, and Firmicutes as primary SMX-degrading phyla—notably key hosts for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Specifically, Desulfobacterota (Desulfovibrio, Desulfobulbus, and Desulfomicrobium) and Firmicutes carry and disseminate sul1/sul2 in wetlands[56,57], and ARG-harboring hosts may degrade antibiotics more efficiently[34]. Critically, SIP revealed denitrifiers Pseudomonas, Robiginitalea, Bacillus, Phaeodactylibacter, and Bdellovibrio assimilating 13C-SMX (Fig. 5), confirming their SMX-biodegradation capability—consistent with Pseudomonas[58], Bacillus[59], and Bdellovibrio[60]. Furthermore, antibiotics promote the co-occurrence of nitrate reduction genes and ARGs[61], with Pseudomonas[62], Robiginitalea[63], and Bacillus[64] documented as hosts of ARGs. Based on previous studies, SMX biodegradation involves multiple pathways. In this study, as SMX biodegradation was conducted by denitrifiers, one important pathway for SMX degradation initiated with ipso-hydroxylation of the aniline moiety, resulting in cleavage of the sulfonamide −C−S−N− bond and accumulation of heterocyclic metabolites[59].

By day 28, nirS/nirK abundance showed a U-shaped dose-response, while sul1/sul2 increased significantly under high SMX (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S2). Correlation analysis linked denitrifiers Ignavibacterium to sul1, and Marinobacter, Phaeodactylibacter, and Pseudomonas to sul2 (Supplementary Figs S4, S5), suggesting these taxa may host ARGs and facilitate horizontal gene transfer. Thus, denitrifiers likely acquire ARGs through adaptation, thereby mitigating antibiotic inhibition of denitrification via dual strategies: direct antibiotic degradation, and resistance gene expression[28]. In that case, denitrifiers may be able to endure persistent exposure to SMX in estuarine and coastal regions and retain considerable ability to remove excessive reactive nitrogen under antibiotic stress.

In this study, the relative abundance of the sul1 and sul2 genes increased slightly with prolonged incubation time, but the increase was not significant. However, under SMX stress, the abundances of ARGs (sul1 and sul2) increased significantly by approximately 30% (p < 0.05). Exposure to high concentrations of antibiotics stimulates the transfer and autonomous replication of plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes in microbial communities, findings consistent with previous studies and that may elevate the health threat posed by biocontaminants in aquatic ecosystems[6,17,22,65,66]. Notably, sul1 enrichment in 13C-DNA fractions coincided with active SMX-degrading microbes, indicating dual resistance mechanisms: metabolic SMX breakdown, and ARG upregulation[37,67,68]. Conversely, sul2 absence in heavy DNA implies its hosts resist SMX without degrading it[37]. Collectively, microbial communities employ both biodegradation and ARGs development to counteract antibiotic stress.

-

In conclusion, this study elucidates the dynamic response of sedimentary nitrogen cycling to sulfamethoxazole (SMX), demonstrating that SMX initially inhibits denitrification but shifts to stimulation at high concentrations (≥ 1,000 μg L−1) as the antibiotic degrades. Critically, SMX amplifies N2O emissions by unbalancing the inhibition of nirS, nirK, and nosZ genes, thereby impairing N2O reduction. DNA-SIP further revealed that denitrifying bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Robiginitalea) actively assimilate SMX through dual resistance strategies: direct biodegradation and ARG (sul1) development. These mechanistic insights advance understanding of SMX fate and nitrogen transformations in anthropogenically impacted aquatic environments.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0006.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yin G, Han P; analysis and interpretation of results: Li C, Tang X, Pan J, Zhou Z; data collection: Li C, Tang X, Chen C, Li Y; draft manuscript preparation: Li C, Tang X; review and editing: Yin G, Han P; funding acquisition: Yin G, Han P, Hou L, Liu M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3208404 and 2024YFF0808804), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42476153, 42573078, 42371064, 42030411, and 42230505), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

First dual-tracer (15N + DNA-SIP) study decoupling SMX impacts on denitrification/N2O.

Biphasic denitrification: SMX inhibits initially (≤ 21 d) but stimulates at 1,000 μg L−1.

SMX biodegradation may stimulate the activity of denitrifying bacteria.

sul1 enrichment in 13C-DNA ties resistance to active SMX degraders.

nosZ inhibition > nirS boosts N2O emissions by 178% under SMX.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Chuangchuang Li, Xiufeng Tang

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Supplementary File 1 Supplementary methods to this study.

- Supplementary Table S1 The basic physical and chemical properties of the collected sediment in this study (means ± standard deviation; n =3).

- Supplementary Table S2 Physicochemical properties of the sediments after incubation.

- Supplementary Table S3 Primers and qPCR conditions for Bacterial 16S rRNA, nirK, nirS, nosZ, sul1 and sul2.

- Supplementary Table S4 PICRUSt2 data of total DNA, 13C and 12C DNA.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Study area and sampling site location.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Temporal changes in gene copy numbers for sul1 under different concentrations of SMX ranging from 0 to 1,000 μg L−1 over a 28-day incubation. Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3). The different lowercase letters above columns indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Relationships between denitrifiers and the denitrification rates and N2O emission rates after incubation. DNF is the potential denitrification rate. * represents p < 0.05; ** represents p <0.01; *** represents p <0.001.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Relationships between denitrifiers and ARGs after incubation. * represents p < 0.05; ** represents p < 0.01; *** represents p < 0.001.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Relationships between biotic and abiotic factors and the denitrification rates and N2O emission rates after incubation. DNF is the potential denitrification rate. DNF is the potential denitrification rate. * represents p < 0.05; ** represents p < 0.01; *** represents p < 0.001.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li C, Tang X, Yin G, Han P, Chen C, et al. 2025. Linking denitrifiers with sulfamethoxazole biodegradation: insights from DNA-based stable isotope probing. Biocontaminant 1: e007 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0006

Linking denitrifiers with sulfamethoxazole biodegradation: insights from DNA-based stable isotope probing

- Received: 18 September 2025

- Revised: 31 October 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published online: 21 November 2025

Abstract: Antibiotics are widespread in estuarine and coastal ecosystems, posing ecological risks to organisms and microbially mediated nitrogen cycling. This study, for the first time, employed 15N tracing and DNA-stable-isotope probing (DNA-SIP) techniques to investigate the effects of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) on sediment denitrification, associated N2O emissions, and the active SMX-biodegrading bacterial community. SMX inhibition of denitrification was time-dependent: significant suppression occurred during days 1–14, but diminished as SMX degraded from days 21–28, exhibiting a U-shaped response. 13C-SIP identified putative denitrifying bacteria (Pseudomonas, Robiginitalea, Bacillus, Phaeodactylibacter, and Bdellovibrio) assimilating 13C-SMX, suggesting SMX biodegradation may stimulate denitrifier activity. The SMX resistance gene sul1 was also enriched in 13C-DNA, implying it may benefit from SMX degradation or originate from active SMX degraders. Furthermore, SMX promoted N2O emissions by disproportionately inhibiting nirS (NO2− → NO) relative to nosZ (N2O → N2). These results establish a functional link between SMX-degrading bacteria and denitrifiers, providing a deeper mechanistic understanding of how antibiotics affect nitrogen transformations in estuarine-coastal sediments.

-

Key words:

- Sulfamethoxazole /

- Denitrification /

- Biodegradation /

- DNA-SIP /

- Denitrifiers