-

The increasing prevalence of plastic pollution has garnered worldwide attention[1−3], and one key risk factor associated with plastics pollution is the release of additives[4], such as phthalates and organophosphate esters (OPEs)[5−7]. In addition to being a common plasticizer, OPEs are also extensively utilized as pesticides and flame retardants[8−10], and are commonly detected in the environment[11−14]. The majority of OPE pollutants are endocrine disruptors[15−18], and can induce a wide range of toxic effects, including neurological[19], respiratory[20], developmental[21−23], and reproductive[24] toxicities, as well as potential carcinogenicity[25−27], thus causing concerns over their health and ecological risks. The degradation and weathering of plastics into microscale and nanoscale particles is expected to accelerate the leaching of OPE additives[28−30], which exacerbates the environmental impacts of microplastics[28,31,32]. The ecological risks of OPE pollutants are largely dictated by their environmental behavior and transformation processes, including biotic and abiotic oxidation and hydrolysis[33−35].

Metal-bearing nanoparticles, which are abundant in the environment, play significant roles in various biogeochemical processes and substantially impact the fate and transport of environmental pollutants[36−38]. Iron oxides, among the most plentiful metal oxide nanoparticles in the environment[36], can significantly influence the transformation of pollutants[39,40], due to their compositional and structural diversity and redox activity[39,41]. For instance, nanosized iron oxides can adsorb pollutants[42,43], or form co-precipitates with them[44]. Moreover, iron oxides can catalyze the oxidation-reduction[45−47] and hydrolysis[34,48−50] reactions of pollutants in the environment. Hydrolysis is one of the most important reaction types that affect the environmental fate of organic pollutants such as esters[48,51], chlorinated hydrocarbons[52], and antibiotics[50,53,54]. Recent studies have demonstrated that physicochemical properties of nanosized iron oxides, particularly exposed facets, can affect their efficiency in mediating the hydrolytic transformation of organic pollutants (including phthalates and OPEs) in the environment[48,51]. However, the impacts of crystalline phase, a critical parameter that fundamentally determines the bulk and surface atomic arrangement and coordination state, on the ability of iron oxide nanoparticles to mediate the hydrolysis of organic pollutants remain to be elucidated.

Herein, we investigated the mechanisms by which the crystalline phase of iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles affects their efficiencies in mediating the hydrolysis of OPE pollutants. Three common polymorphs of iron oxyhydroxide, including goethite (α-FeOOH), akageneite (β-FeOOH), and lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), were chosen as model materials, and p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) was selected as a model OPE compound, as it represents the core structure of common OPE pollutants[55,56]. The performance of the oxyhydroxide nanoparticles in catalyzing pNPP hydrolysis at environmentally relevant pH (6.0 to 8.0) was examined, and the Langmuir–Hinshelwood kinetics model was used to compare the differences in pNPP adsorption affinity and surface catalytic activity among the iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles. Moreover, the adsorption configuration of pNPP and its adsorption affinity on iron oxyhydroxide with different crystalline phases were investigated using in situ attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) analysis, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. A correlation between surface reactivity, and Lewis acidity of the materials was discerned using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy after pyridine adsorption (Py-IR), and DFT calculations. This study provides valuable insights to enhance predictive understanding of the environmental behavior of OPE plastic additives and the related ecological risks.

-

Information on the chemicals used is provided in Supplementary File 1 (Text S1). The specific synthesis procedures for the three iron oxyhydroxide materials are detailed in Supplementary File 1 (Text S2).

The morphological features of the materials were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The crystalline phases were determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD). The specific surface area (SABET) was determined from the nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms. The ζ-potential was measured at pH 3 to 11. The surface acidity of the materials was analyzed by Py-IR[57]. More detailed characterization methods are provided in Supplementary File 1 (Text S3).

Hydrolysis experiments

-

The pNPP hydrolysis experiments were performed at environmentally relevant conditions (pH 6.0 to 8.0, 25 ± 0.1 °C). The concentrations of pNPP and 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) over time were determined from the UV-vis absorbance at 310 and 400 nm, respectively, with their UV-vis spectra shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. More detailed methods are provided in Supplementary File 1 (Text S4).

Phosphate adsorption experiments

-

Since pNPP constantly hydrolyzes, which makes it inaccurate to directly determine the adsorption capacity of the iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles for pNPP, the adsorption of orthophosphate ions as a surrogate was measured[58]. The adsorption isotherms were determined at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0 (with detailed methods in Supplementary File 1, Text S5).

Data analysis

-

The pNPP hydrolysis data were fitted to the pseudo-first-order kinetic model to calculate the apparent rate constant, kobs (h−1).

The Langmuir−Hinshelwood (L−H) model, a widely used model to describe the kinetics of heterogeneous catalytic reactions[59], was employed to obtain the adsorption coefficient of pNPP on the materials, KL (L mg−1) and the reaction rate constant of adsorbed pNPP, kr (mg L−1 h−1). More details are provided in Supplementary File 1 (Text S6).

In situ ATR-FTIR measurements of pNPP adsorption

-

In situ ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was employed to investigate the adsorption configuration of pNPP on the surface of iron oxyhydroxides. Detailed methodologies are provided in Supplementary File 1 (Text S7).

Theoretical calculations

-

DFT calculations were carried out using the VASP 5.4.4 package[60], to obtain information on the electron localization function (ELF), pNPP adsorption energy, charge density differences, partial density of states (PDOS), and crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP). Details are provided in Supplementary File 1 (Text S8).

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical differences were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (version 19.0, IBM, USA), with significant differences (p < 0.05) indicated by different letters. For pNPP hydrolysis and phosphate ion adsorption experiments, arithmetic means, and standard deviations of triplicate tests were reported.

-

The as-synthesized iron oxyhydroxide materials have different crystalline phases, as demonstrated by XRD results. The XRD pattern of goethite (JCPDS No. 29−0713)[61] has diffraction peaks at 2θ = 17.8°, 21.2°, 33.2°, 34.7°, 36.6°, and 53.2°, corresponding to the (020), (110), (130), (021), (111), and (221) crystal planes, respectively. The XRD pattern of akaganeite (JCPDS No. 34-1266)[61] has diffraction peaks at 2θ = 11.8°, 16.7°, 26.6°, 33.9°, 35.1°, 39.2°, 46.4°, and 55.8°, corresponding to the (110), (200), (310), (400), (211), (301), (411), and (521) crystal planes, respectively. The XRD pattern of lepidocrocite (JCPDS No. 08-0098)[62] has diffraction peaks at 2θ = 14.2°, 27.1°, 36.4°, and 46.8°, corresponding to the (020), (120), (031), and (200) crystal planes, respectively (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, (b) nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms, and (c) pore size distribution curves of goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images of (d) goethite, (e) akaganeite, and (f) lepidocrocite. Electron localization function (ELF) analysis of (g) goethite, (h) akaganeite, and (i) lepidocrocite. Red regions in the ELF isosurface represent strong electron localization, while blue regions indicate delocalized electron states.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm analyses (Fig. 1b) revealed that lepidocrocite possesses a higher SABET (169.2 m2 g−1) than goethite (71.9 m2 g−1), and akaganeite (45.8 m2 g−1)[63]. The larger specific surface area, which is conducive to exposure of more catalytic sites, likely can improve the catalytic efficiency. The isotherms are type IV with type H3 hysteresis loops, indicating the presence of mesopores and macropores in the aggregates[63,64], which is consistent with pore size distribution analysis results (Fig. 1c). Among the three materials, lepidocrocite also exhibits the narrowest pore size distribution, which may hinder the diffusion, and mass transfer of target molecules.

The SEM and TEM images of three types of iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (Fig. 1d–f) show that goethite exhibits nanorod morphology with lengths of 200–600 nm and diameters of 40–50 nm, with most nanorods forming bundled aggregates (Fig. 1d). In contrast, akaganeite presents more uniform spindle-like structures ranging from 200–600 nm in length, and 50–150 nm in diameter (Fig. 1e), and lepidocrocite is composed of nanofibers with diameters of 10–30 nm (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, in the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images, the goethite revealed lattice spacing of 0.26 nm, indexed to the (021) plane[65], and the akaganeite and lepidocrocite displayed lattice spacing of 0.27 and 0.33 nm, corresponding to the (400) plane and (200) plane[66], respectively. Additionally, structural modeling and surface ELF analysis (Fig. 1g–i) reveal distinct densities of unsaturated Fe sites per unit surface area across the different FeOOH phases. This crystalline phase dependency originates not only from active site density differences but also from coordination environments and electronic structures of surface Fe atoms, which collectively modulate Lewis acidity and catalytic reactivity[48,67].

The crystalline phase influences the catalytic pNPP hydrolysis performance of iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles

-

The crystalline phase plays a key role in determining the activity of the iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles in catalyzing the hydrolysis of pNPP under environmentally relevant pH conditions (6.0, 7.0, and 8.0). All three iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (100 mg L−1) significantly accelerated pNPP hydrolysis (Fig. 2), with lepidocrocite exhibiting the highest activity across all pH levels. For instance, at pH 6.0, the removal efficiency of pNPP reached 85% (lepidocrocite), 45% (goethite), and 25% (akaganeite) after 48 h. It is important to note that the mass balance of pNPP and its hydrolysis reaction product 4-NP in the aqueous phase remained > 95% (Supplementary Figs S2–S4). Considering that pNPP hydrolysis was negligible (< 3%) in the absence of iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (Fig. 2a), we believe that heterogeneous catalytic hydrolysis was the dominant removal mechanism rather than adsorption. The hydrolysis kinetics fitted to the pseudo-first-order model well, and surface area-normalized rate constant (kobs/SABET) followed the order of lepidocrocite > akageneite > goethite (Fig. 2d–f and Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, hydrolysis efficiency decreased with increasing pH, which can be attributed to electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged iron oxyhydroxides surfaces at higher pH (Supplementary Fig. S5) and the deprotonated forms of pNPP (pNPP− and/or pNPP2−) predominant at pH 6.0 to 8.0 (Supplementary Fig. S6), thereby hindering substrate adsorption and diminishing catalytic performance[68].

Figure 2.

Efficiencies of iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles in catalyzing pNPP hydrolysis. Catalytic pNPP hydrolysis kinetic curves in the absence (denoted as 'Control'), or presence of the iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles at pH (a) 6.0, (b) 7.0, (c) 8.0, and (d)–(f) the corresponding surface area-normalized kobs. Initial pNPP concentration: 6.0 mg L−1. The italic letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

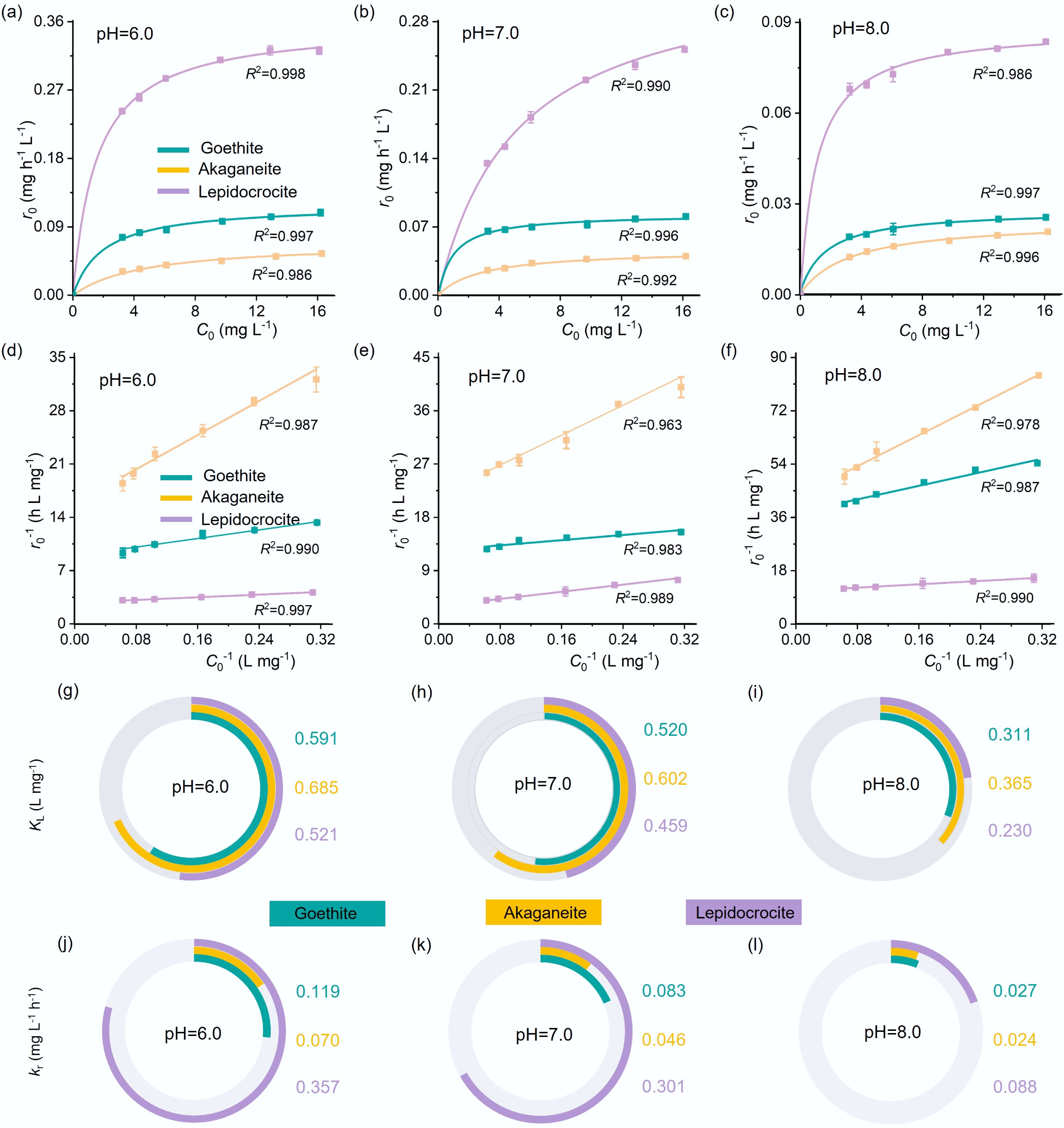

The hydrolysis of pNPP catalyzed by iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles proceeds via a surface-mediated reaction, in which pNPP first adsorbs to the surface active sites, followed by cleavage of the phosphate ester bond. To decouple the effects of adsorption and surface reactivity, initial reaction rates (r0) were fitted using the L–H model[59] across variable initial pNPP concentrations (C0 = 3.2–16 mg L−1) and pH values (Supplementary Tables S2–S4, Fig. 3a–f, Supplementary Figs. S7−S9). For all the iron oxyhydroxides, r0 as a function of C0 fits well with the L–H model (Fig. 3a–f), revealing distinct differences in both adsorption affinity and surface reactivity (Fig. 3g–l). At pH 6 (Fig. 3g), the KL values followed the trend: akaganeite (0.685 L mg−1) > goethite (0.591 L mg−1) > lepidocrocite (0.521 L mg−1), indicating the strongest pNPP affinity of akageneite. Interestingly, this trend does not align with the apparent catalytic activity normalized to surface area (kobs/SABET), and notably, lepidocrocite, which exhibited the highest kobs/SABET, had the lowest affinity toward pNPP. This suggests that, apart from adsorption affinity, other factors also influence the overall hydrolysis efficiency. Indeed, the surface reaction rate constants show a different pattern, and lepidocrocite exhibited much higher kr than the other two materials (Fig. 3j−l); for example, at pH 6, lepidocrocite exhibited a 5.1-fold higher kr value than akaganeite and 3.0 times greater than goethite (Fig. 3j). The highest surface reactivity of lepidocrocite compensated for its lowest pNPP adsorption affinity, thus contributing to its superior overall catalytic efficiency.

Figure 3.

(a)–(c) Initial hydrolysis reaction rate (r0) vs initial pNPP concentration (C0), with lines representing least-squares fit to the L–H model, (d)–(f) linear plot of r0−1 vs C0−1, (g)–(i) L–H model parameters KL (representing surface adsorption affinity), and (j)–(l) kr (representing surface reactivity) determined for each material at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0.

Crystalline phase regulates pNPP adsorption affinity by modulating electronic interaction of Fe 3d and O 2p

-

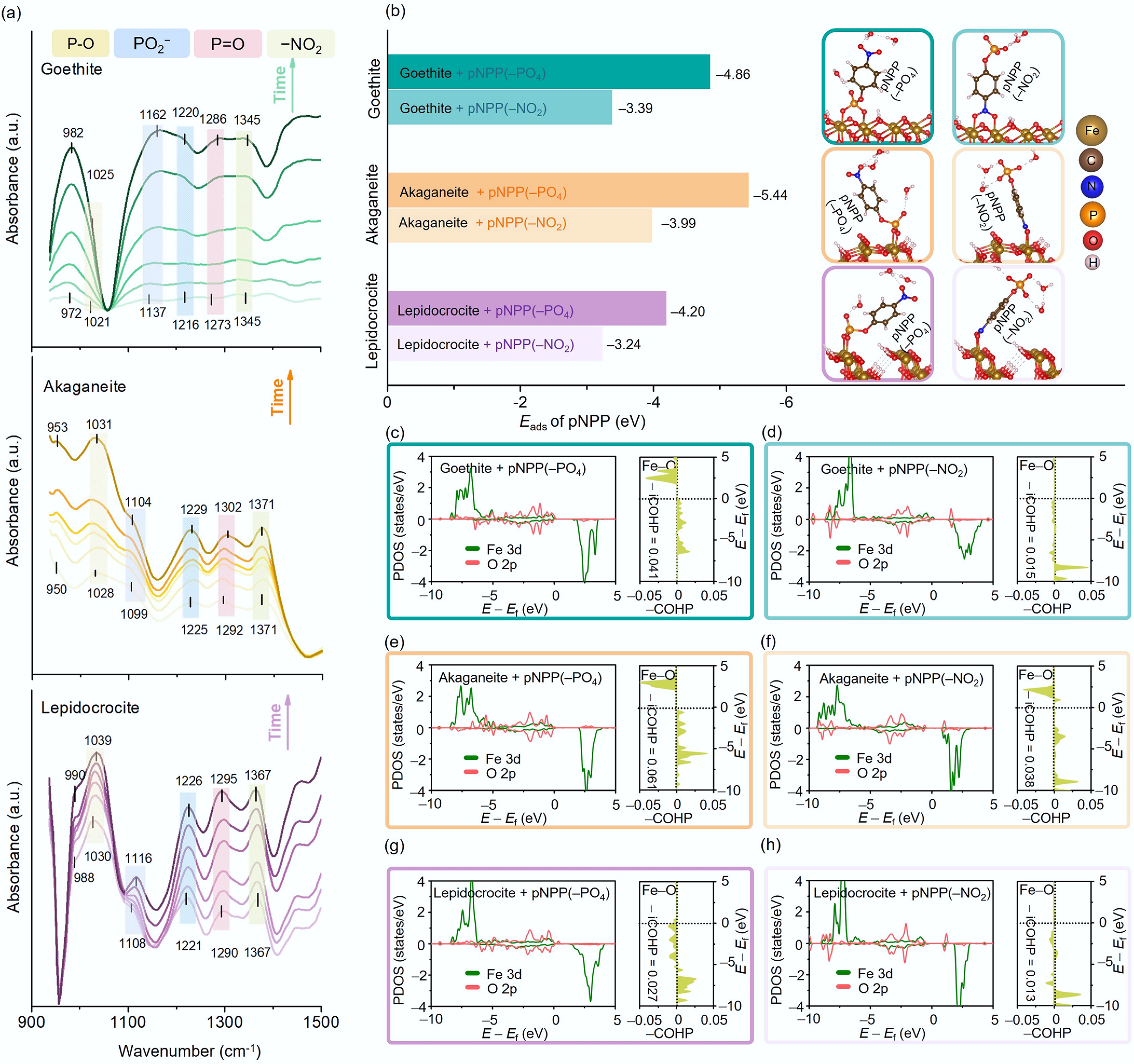

The effective adsorption of reactant molecules onto a material surface is a prerequisite for heterogeneous catalytic hydrolysis of organic contaminants mediated by metal oxide nanoparticles[48,53]. Accordingly, differences in the adsorption affinity of pNPP on iron oxyhydroxides with different crystalline phases have a crucial influence on their overall catalytic performance. In situ ATR-FTIR analysis suggests that pNPP molecules were primarily adsorbed through inner-sphere complexation, which involves the −PO4 group of pNPP binding directly to surface Fe atoms. The characteristic absorption bands of pNPP on the material surfaces progressively increased over time (Fig. 4a), reflecting the continuous adsorption process[69]. Although the ATR-FTIR spectral features differed among goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite, likely due to variations in surface charge distribution caused by different crystalline phases (Fig. 1g–i), several common trends were observed, providing insights into their adsorption mechanisms. Specifically, the ATR-FTIR spectrum of pNPP dissolved in water (Supplementary Fig. S10) showed bands of the −PO4 group at 1,089, 1,167, and 1,260 cm−1[43,48,69], and that of the −NO2 group at 1,347 cm−1 (corresponding to the νs(−NO2) mode)[48,70]. When pNPP was adsorbed onto iron oxyhydroxides (Fig. 4a), the characteristic ν(P−O), νs(PO2−), and ν(P=O) bands of the −PO4 group increased in intensity over time and shifted to higher wavenumbers, whereas that of the −NO2 group remained stable at 1,345–1,371 cm−1[43,48]. Moreover, a band at 950–990 cm−1 was observed (Fig. 4a), which corresponds to the P−O−Fe bond[48,71,72], arising from the inner-sphere complexation between pNPP and the surface Fe atoms of the iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles.

Figure 4.

(a) In situ ATR-FTIR spectra of goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite (along the direction indicated by the arrow; the time is: 5, 30, 60, 90, 130, and 180 min). (b) The adsorption energy (Eads) of pNPP on goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite via different functional groups (−PO4 or −NO2) and the corresponding stable adsorption configurations (insets). The PDOS and COHP of Fe 3d and O 2p orbitals during adsorption in various configurations: adsorption of pNPP via the −PO4 or −NO2 group on (c), (d) goethite, (e), (f) akaganeite, and (g), (h) lepidocrocite.

DFT calculations confirmed that the adsorption energy (Eads) of pNPP via the −PO4 group on iron oxyhydroxide surfaces was considerably larger in absolute value than that through the −NO2 group (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Figs S11–S16), indicating that adsorption via the −PO4 group is thermodynamically more favorable. This result corroborates the proposed mechanism that pNPP preferentially binds to surface Fe atoms on iron oxyhydroxides through inner-sphere complexation involving the −PO4 group. Additionally, noticeable differences in Eads values were observed among three crystalline phases of iron oxyhydroxides. Specifically, akaganeite exhibited the lowest Eads (–5.44 eV), followed by goethite (–4.86 eV), and lepidocrocite (–4.20 eV), suggesting that akaganeite possesses a stronger adsorption affinity for pNPP, consistent with the experimental observations (Fig. 3g–i). Moreover, the PDOS and COHP analyses revealed a more pronounced overlap between Fe 3d orbitals and O 2p orbitals of the −PO4 group compared with the −NO2 group (Fig. 4c–h). The bonding orbitals were more extensively populated with covalent electrons (−COHP > 0, E < Ef, −iCOHP = 0.027–0.041), indicating a stronger electronic interaction between Fe atoms and the −PO4 group[73]. Among the crystalline phases, akaganeite displayed the highest bonding strength, as reflected by its −iCOHP value of 0.061, exceeding those of goethite (0.041), and lepidocrocite (0.027). This suggests a higher degree of electron density in the bonding orbitals and stronger interaction between akaganeite and pNPP. Interestingly, surface area-normalized adsorption coefficients Kd of orthophosphate ions by the materials (Supplementary Fig. S17) showed similar trends to the adsorption affinity predicted by theoretical calculations, which is also consistent with the experimentally determined KL of pNPP.

Crystalline phase enhances catalytic hydrolysis performance by inducing electron redistribution in pNPP via surface Lewis acid sites

-

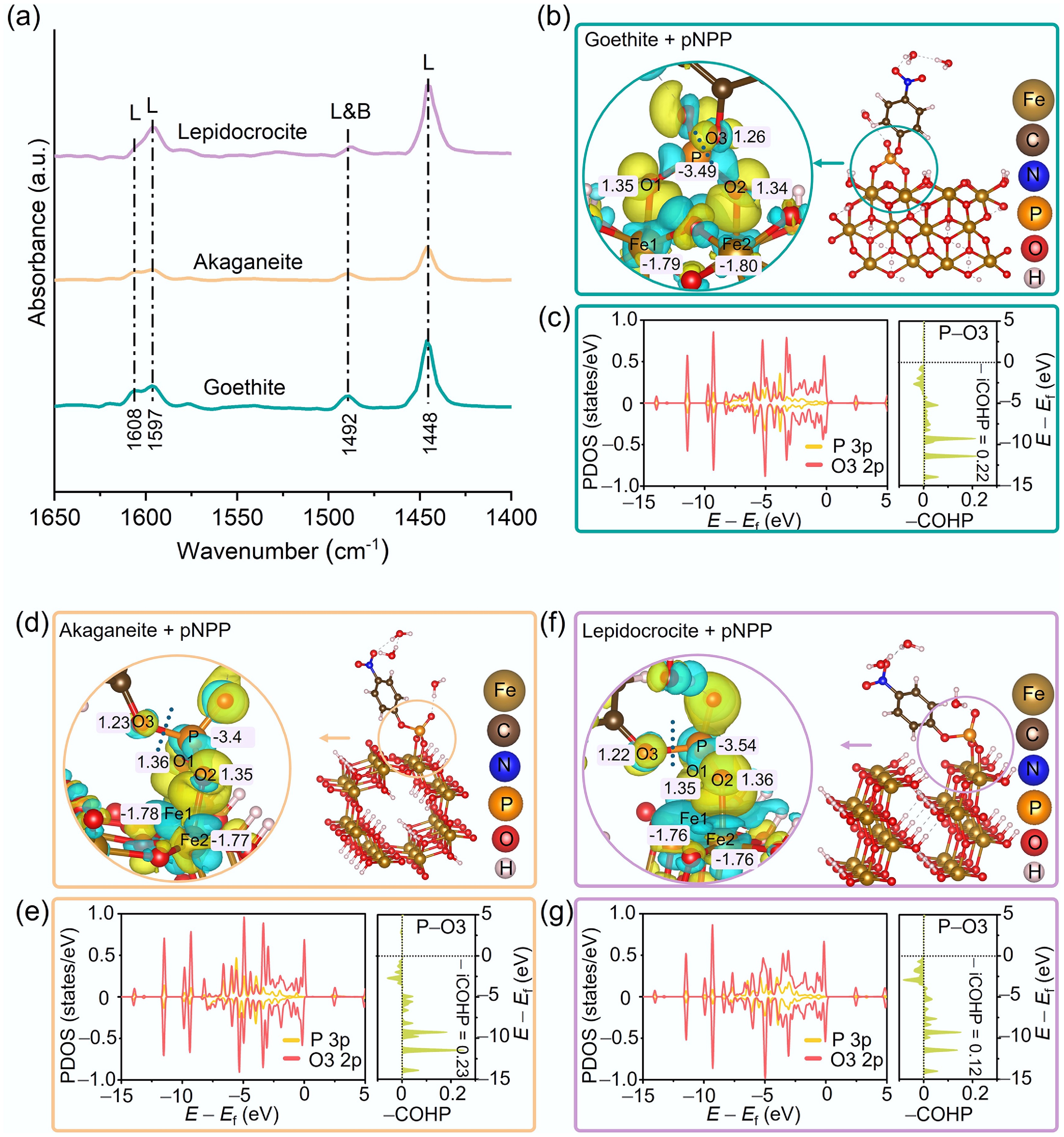

The coordination saturation of metal sites on metal oxide surfaces is a key factor governing their Lewis acidity, which directly influences their catalytic activity toward the hydrolysis of organophosphorus pollutants[34,48,74]. According to Py-IR analysis (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S18), all three types of iron oxyhydroxides are rich in Lewis acid sites (the bands at 1,448, 1,597, and 1,608 cm−1 are typically attributed to Lewis acid sites[47,75]; that at 1,492 cm−1 is usually assigned to both Lewis and Brønsted acid sites[75], though with weaker intensity; and no band corresponding to Brønsted acid sites at 1,545 cm−1 was observed[47]). Among them, lepidocrocite exhibited the highest density of Lewis acid sites (214 μmol m−2), significantly surpassing those of akaganeite (177 μmol m−2), and goethite (192 μmol m−2), consistent with its superior catalytic performance in pNPP hydrolysis (Figs 2 and 3, Supplementary Table S1). These acid sites play a crucial role in facilitating pNPP conversion by stabilizing electron-rich intermediates and reducing the activation energy barrier[76].

Figure 5.

(a) Py-IR spectra of goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite. Charge density differences and Bader charge analyses for pNPP molecules adsorbed onto the surfaces of (b) goethite, (d) akaganeite, and (f) lepidocrocite. Yellow and cyan regions represent electron accumulation and depletion, respectively. PDOS and COHP analyses of the P 3p and O3 2p orbitals in pNPP adsorbed on (c) goethite, (e) akaganeite, and (g) lepidocrocite, respectively.

In the catalytic system of iron oxyhydroxides, coordinatively unsaturated Fe atoms act as Lewis acid sites, engaging in electron pair sharing with the –PO4 group of pNPP, which functions as a Lewis base, thereby driving the hydrolysis reaction[34,48,74]. Charge density differences (Fig. 5b, d, and f) confirm this process, showing an increase in electron density on the oxygen atoms of the –PO4 group and a corresponding partial positive charge (δ+) on the central P atom. This polarization effect enhances the susceptibility of the P atom to nucleophilic attack by H2O molecules. Bader charge analysis (Fig. 5b, d, and f) further elucidates the crystalline phase-dependent promotion of hydrolysis: the charge transfer on the P atom of pNPP adsorbed on lepidocrocite (–3.54 e) is notably greater than that observed for akaganeite (–3.49 e), and goethite (–3.44 e), indicating that lepidocrocite more effectively facilitates nucleophilic hydrolysis. Furthermore, bonding stability analysis provides deeper insight into the underlying mechanism. PDOS and COHP results (Fig. 5c, e, and g) reveal that pNPP adsorbed on lepidocrocite exhibits the weakest orbital overlap between the P 3p orbitals and the O3 2p orbitals of the ester bond. A larger proportion of covalent electrons occupies the antibonding orbitals (E < Ef, –COHP < 0, –iCOHP = 0.12), significantly weakening the P–O bond. This electronic configuration is identified as the intrinsic origin of the enhanced hydrolytic efficiency observed for lepidocrocite.

-

Iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (including goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite) can effectively promote the hydrolysis of OPE pollutants under environmentally relevant pH conditions, and their catalytic capacity is significantly affected by the crystalline phase, with surface area-normalized rate constant following the order: lepidocrocite > akaganeite > goethite. The mechanisms underlying the crystalline phase-dependent catalytic activity were elucidated by experimental and theoretical investigations. Specifically, the crystalline phase influenced both the adsorption affinity of the iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles toward pNPP and the reactivity of the surface-bound pNPP molecules. Differences in surface charge distribution of different crystalline phases and their electronic interactions with the –PO4 groups in pNPP led to variations in their adsorption affinities for pNPP (akaganeite > goethite > lepidocrocite). Moreover, crystalline phase-dependent variation in surface Lewis acidity of the iron oxyhydroxides (in the order of lepidocrocite > goethite > akaganeite) and the induced charge rearrangement of the central P atom in pNPP largely determined their overall apparent catalytic activity.

These findings deepen our understanding of the critical role of the crystalline phase in regulating the capability of metal oxide nanominerals to mediate hydrolytic transformation of OPEs, and potentially other plastic additives, which are valuable for accurately assessing the environmental behavior and potential ecological risks of these emerging pollutants. Notably, in real aquatic environments, metal oxides may interact with ions and natural organic matter, altering the surface charge, density of surface active sites, and even the crystalline phase[61,77,78], which may dampen the crystalline phase-dependent catalytic activity observed in the simplified systems. Meanwhile, the adsorption of ions such as Zn2+ may promote hydrolysis reactions by metal oxides[54]. Therefore, future research needs to elucidate how metal oxide nanominerals mediate the hydrolysis reactions under complex environmental conditions, so as to more accurately predict the environmental fate and risks of plastic additives.

-

It accompanies this paper at https://doi.org/10.48130/ebp-0025-0008.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Pei X, Liang Z, Chen Z; writing – original draft, methodology: Pei X, Liang Z; writing – review & editing: Pei X, Duan L, Jiang C, Alvarez PJJ, Zhang T; data curation: Pei X, Liang Z, Chen Z; funding acquisition: Pei X, Duan L, Jiang C, Zhang T; formal analysis, visualization: Pei X; visualization: Liang Z; project administration, conceptualization: Jiang C; supervision: Zhang T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22125603, 22241602, and 22020102004), Starting Research Grant for High-level Talents and Innovative Foundation from Ankang University (2023AYQDZR21, 2025AYHX008, and 2024AKHX009), Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (23JCZDJC00740), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (63253200 and 63251028), and the Ministry of Education of China (B17025).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Crystalline phase dictates the efficiency of iron oxyhydroxides in catalyzing OPE hydrolysis.

Lepidocrocite exhibits superior catalytic performance to goethite and akageneite.

Crystalline phase-dependent Fe 3d-O 2p electronic interaction mediates adsorption affinity.

Crystalline phase-dependent Lewis acidity determines the surface reactivity of adsorbed OPEs.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Xule Pei, Zongsheng Liang

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Supplementary File 1 Supplementary materials and methods to this study.

- Supplementary Table S1 Summary of the experimental parameters and fitted kinetic constants of pNPP hydrolysis mediated by different iron oxyhydroxide nanomaterials at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0 (Initial pNPP concentration: 6.0 mg L−1).

- Supplementary Table S2 Summary of the experimental parameters and fitted kinetic constants of pNPP hydrolysis (pH = 6.0) mediated by iron oxyhydroxide nanomaterials at varying initial pNPP concentrations.

- Supplementary Table S3 Summary of the experimental parameters and fitted kinetic constants of pNPP hydrolysis (pH = 7.0) mediated by iron oxyhydroxide nanomaterials at varying initial pNPP concentrations.

- Supplementary Table S4 Summary of the experimental parameters and fitted kinetic constants of pNPP hydrolysis (pH = 8.0) mediated by iron oxyhydroxide nanomaterials at varying initial pNPP concentrations.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The UV-vis spectra of pNPP and 4-NP under alkaline conditions (pNPP and 4-NP concentration: 10 mg L−1, and NaOH concentration: 0.1 mol L−1).

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Changes of pNPP and 4-NP concentrations during pNPP hydrolysis experiments at pH 6.0 in (a) control, (b) goethite, (c) akaganeite, and (d) lepidocrocite. Error bars indicate standard deviations of triplicates.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Changes of pNPP and 4-NP concentrations during pNPP hydrolysis experiments at pH 7.0 in (a) control, (b) goethite, (c) akaganeite, and (d) lepidocrocite. Error bars indicate standard deviations of triplicates.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Changes of pNPP and 4-NP concentrations during pNPP hydrolysis experiments at pH 8.0 in (a) control, (b) goethite, (c) akaganeite, and (d) lepidocrocite. Error bars indicate standard deviations of triplicates.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Zeta potential of goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite at different pH values.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Speciation of pNPP in aqueous solution with an ionic strength of 5 mM at 25 °C. The acid dissociation constants of pNPP, pKa1 and pKa2, are 5.2 and 5.8 [12]. The activity coefficients for the deprotonated species pNPP− and pNPP2− were estimated to be 0.93 and 0.74, respectively, according to the Davies Equation.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Catalytic hydrolysis kinetics of pNPP with different initial concentrations by different nanomaterials: (a) goethite, (b) akaganeite, and (c) lepidocrocite at pH 6.0.

- Supplementary Fig. S8 Catalytic hydrolysis kinetics of pNPP with different initial concentrations by different nanomaterials: (a) goethite, (b) akaganeite, and (c) lepidocrocite at pH 7.0.

- Supplementary Fig. S9 Catalytic hydrolysis kinetics of pNPP with different initial concentrations by different nanomaterials: (a) goethite, (b) akaganeite, and (c) lepidocrocite at pH 8.0.

- Supplementary Fig. S10 ATR-FTIR spectrum of pNPP in aqueous solution at pH 6.0.

- Supplementary Fig. S11 Structural models after the adsorption of pNPP on goethite via the −PO4 group.

- Supplementary Fig. S12 Structural models after the adsorption of pNPP on goethite via the −NO2 group.

- Supplementary Fig. S13 Structural models after the adsorption of pNPP on akaganeite via the −PO4 group.

- Supplementary Fig. S14 Structural models after the adsorption of pNPP on akaganeite via the −NO2 group.

- Supplementary Fig. S15 Structural models after the adsorption of pNPP on lepidocrocite via the −PO4 group.

- Supplementary Fig. S16 Structural models after the adsorption of pNPP on lepidocrocite via the −NO2 group.

- Supplementary Fig. S17 The surface area-normalized adsorption coefficients (Kd) of orthophosphate ion by the materials at different pH. Different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

- Supplementary Fig. S18 The Lewis acid content of goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite as determined using Py-IR.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Pei X, Liang Z, Chen Z, Duan L, Jiang C, et al. 2025. Crystalline phase-dependent hydrolysis of organophosphate esters by iron oxyhydroxides: implications for nanomineral-mediated transformation of plastic additives. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e007 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0008

Crystalline phase-dependent hydrolysis of organophosphate esters by iron oxyhydroxides: implications for nanomineral-mediated transformation of plastic additives

- Received: 12 July 2025

- Revised: 11 August 2025

- Accepted: 09 September 2025

- Published online: 21 October 2025

Abstract: A key risk factor associated with pervasive plastic pollution is the release of additives, including organophosphate esters (OPEs). Metal-bearing nanoparticles, such as iron oxides, can significantly affect the transformation of these plastic additives. However, the mechanisms underlying how intrinsic properties of iron oxide minerals determine their capability to mediate the transformation of OPEs are still obscure. Here, it is demonstrated that iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (goethite, akaganeite, and lepidocrocite) can effectively catalyze the hydrolysis of 4-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP), a model OPE contaminant, under environmentally relevant pH conditions (pH 6.0 to 8.0). The catalytic efficiency exhibits a pronounced dependence on the crystalline phase of the iron oxyhydroxides, with surface area-normalized rate constant following the order: lepidocrocite > akaganeite > goethite. The crystalline phase-dependent catalytic performance is jointly governed by two key factors, i.e., the adsorption affinity toward pNPP of the iron oxyhydroxide nanoparticles and the reactivity of adsorbed pNPP at the surface. Specifically, differences in surface charge distribution among the crystalline phases lead to variations in electronic interactions with the phosphate groups in pNPP, affecting their adsorption affinities (akaganeite > goethite > lepidocrocite). Concurrently, the intrinsic catalytic reactivity (lepidocrocite > goethite > akaganeite) is governed by variations in Lewis acid sites and their ability to induce charge redistribution at the central P atom in adsorbed pNPP. These findings underscore the critical role of the mineral crystalline phase in controlling the environmental fate of OPEs and other plastic-derived additives, and can guide the accurate evaluation of the ecological risks of these emerging pollutants.

-

Key words:

- Organophosphate esters /

- Iron oxyhydroxide /

- Crystalline phase /

- Hydrolysis /

- Plastic pollution