-

The dual crises of greenhouse gas emissions and energy scarcity present urgent challenges for modern society[1,2]. Although natural processes such as CO2 sequestration and geological storage exist, they operate over extended timescales that are insufficient to meet the pressing climate objectives[3]. The transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources is imperative; however, renewable energy inherently suffers from temporal and spatial intermittency[4,5]. At the nexus of energy and environmental imperatives, the conversion of CO2 into high-value chemicals—effectively storing renewable energy—emerges as a transformative technology[6,7], ultimately supporting the development of a sustainable society[8,9].

Interactions between abiotic materials and biological components has garnered significant interest across diverse fields, including nanomaterials science, environmental chemistry, automation, and biomedicine. For example, engineered material–biology interfaces, whether monolithic, distributed, or focal, are fundamental to disease diagnostics and therapeutics[10]. In environmental contexts, functional nanomaterials often undergo biotransformation, most notably through the adsorption of biological components to form a "biocorona". These biological components can range from enzymes, organelles, and cellular appendages to entire cells, tissues, plants, animals (e.g., Drosophila melanogaster, Tubifex tubifex), and even the human body[11−15]. The biocorona critically influences the fate and functionality of nanomaterials, complicating their biological and environmental identities and posing significant challenges for characterization and application[16]. For instance, studies of plasma protein coronas have shown that protein conformational states significantly affect surface coverage, substrate permeability, and catalytic performance[17]. In a related study, a modularly engineered bacterium enabled spatiotemporal control of gene expression and drug release via magnetothermal activation of magnetic nanoparticles, advancing precision immunotherapy for tumors[18].

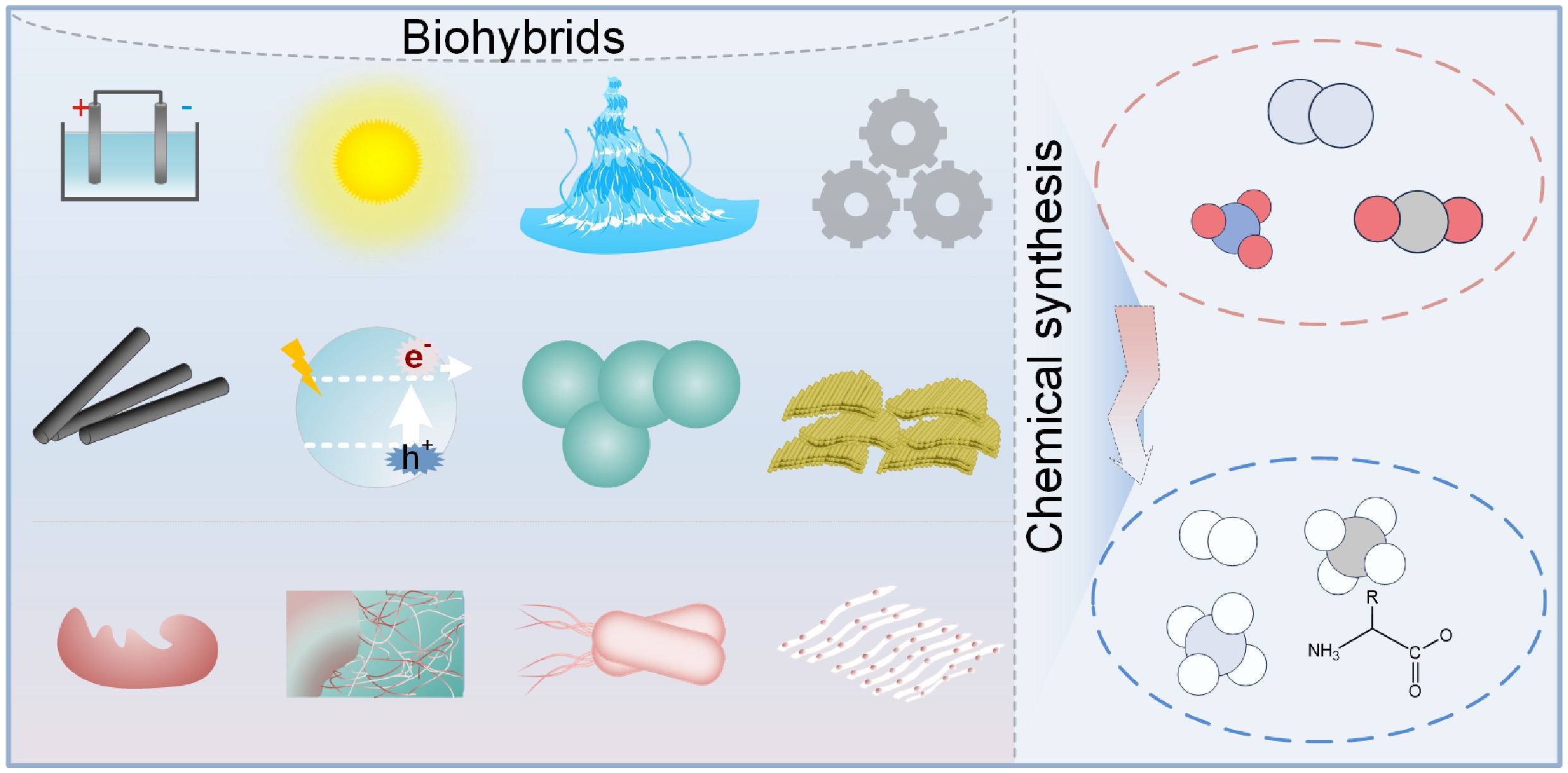

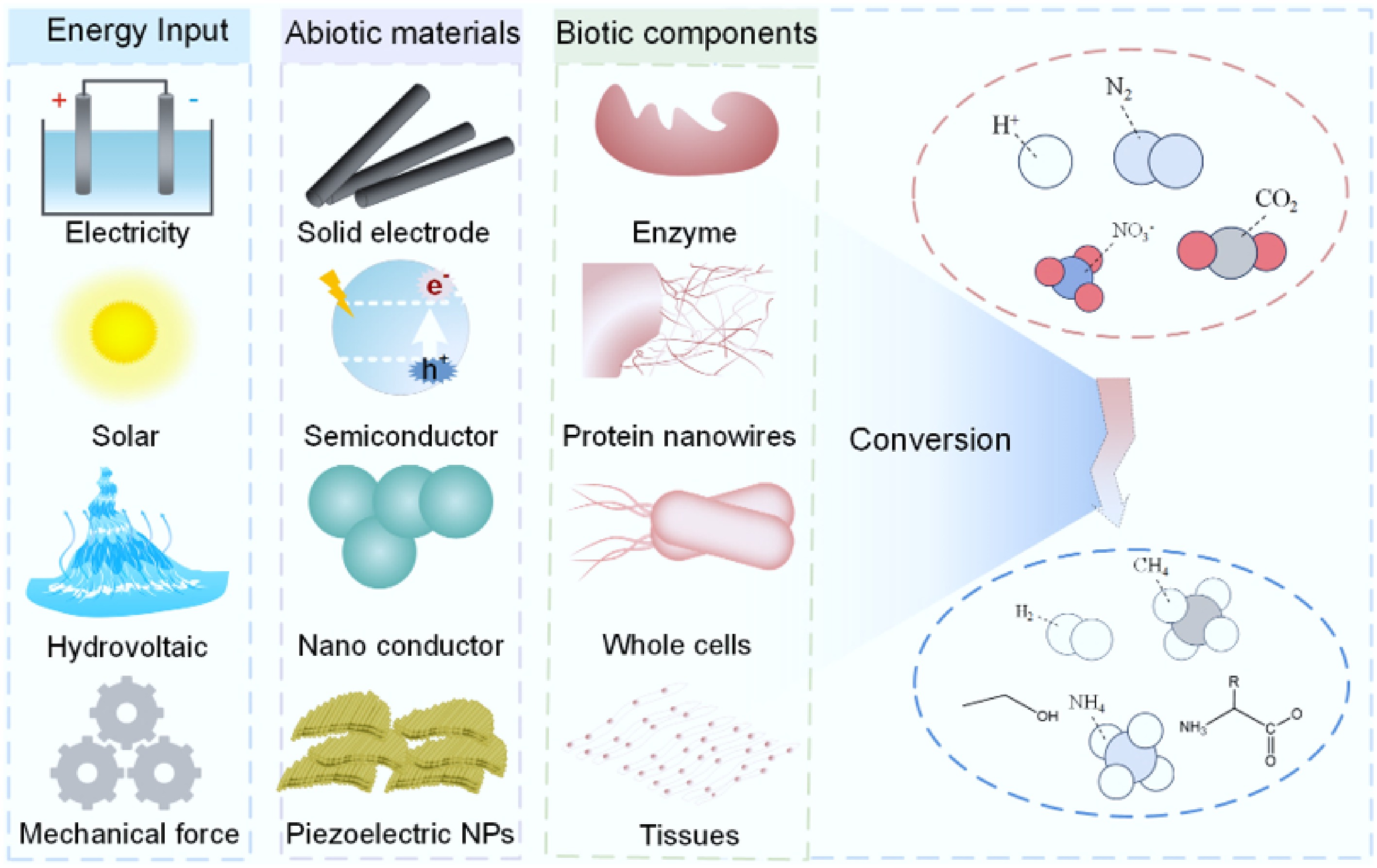

Recently, biohybrids for sustainable chemical synthesis have emerged as a cutting-edge research frontier at the intersection of energy and environmental sciences. These systems integrate diverse energy inputs—including direct current electricity, solar radiation, hydrovoltaic, and mechanical energy—with a broad spectrum of abiotic materials, spanning from nanoscale functional components to solid electrodes at the micrometer scale and beyond. Coupled with various biotic components—such as enzymes, protein nanowires, whole cells, and tissues—biohybrids enable the conversion of multiple substrates into value-added products (Fig. 1). Remarkably, compared with natural photosynthesis, semi-artificial photosynthetic systems integrating the strengths of natural and artificial photosynthesis can achieve higher solar energy conversion efficiency and, in contrast to abiotic artificial photosynthetic systems, can produce high-value products that the latter cannot generate[19].

Figure 1.

Biohybrids for sustainable chemical synthesis. These systems leverage diverse energy inputs, a wide range of abiotic materials, and various biotic components to produce valuable products from multiple substrates.

This review focuses specifically on whole microbial cells as the biotic components of biohybrids; subcellular structures, plant or animal cells, tissues, and multicellular organisms fall outside the scope of this discussion. While the central emphasis is on carbon-based transformations—particularly CO2 conversion—the strategies and methodologies presented are also applicable to other important processes such as H2 production[20,21], N2 fixation[21−24], denitrification[25−27], dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA)[28], and sulfate reduction[29].

Focused specifically on whole microbial cells, microbial uptake of extracellular electrons constitutes the core of energy conversion in biohybrids. Microbes capable of exporting electrons are termed exoelectrogens, whereas those capable of electron uptake are referred to as electrotrophs. Microbial extracellular electron transfer (EET) can operate bidirectionally. Microbes either export intracellular electrons to external acceptors (e.g., iron/manganese oxides, humic substances, electrodes, or syntrophic partners)[30] or import electrons from external solid substrates (e.g., reduced minerals, humics, electrodes, or syntrophic partners)[31]. Notably, the model industrial microorganism Escherichia coli has been adaptively evolved to use an anode as a terminal electron acceptor, which involved rapid genetic changes in the outer membrane porin OmpC, significantly enhancing EET mediated by 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (HNQ), thereby supporting cellular growth[32]. Nevertheless, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying microbial EET remains a complex and ongoing endeavor[33−35].

Poised electrodes are frequently employed in microbial electrochemical systems to simulate the electron-donating or -accepting behavior of abiotic materials under external energy stimulation. On the anodic side, numerous electroactive microbes have been identified[36], laying the foundation for microbial fuel cells (MFCs) and derivative technologies[37−40]. On the cathodic side, microbes such as methanogens, acetogens, and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) can directly uptake extracellular electrons to sustain their metabolic functions[41,42]. The concept of microbial electrosynthesis (MES) is widely acknowledged to have emerged in 2010, when a model acetogenic bacterium, Sporomusa ovata, was employed to capture electrons from an electrode for reducing CO2, ultimately leading to the generation of extracellular products including acetate and 2-oxobutyrate[43]. Notably, the MES technology employs poised electrodes in dark environments to replicate the activated abiotic materials capable of exciting electrons, thereby establishing a robust experimental framework for probing interfacial redox interactions between abiotic substrates and microbial consortia[44,45].

Numerous reviews have explored microbial electrochemical chemical synthesis, covering multiple topics including microbial electrodes[46], multidisciplinary analyses[47], energy flow[19], product diversity[48,49], electroactive microbes[36,50], metabolic and energy conversion strategies[44,51], fundamental mechanisms[52,53], and the engineering of EET pathways[54].

Building on this foundation, the present review adopts a broader macroscopic perspective and focuses on biohybrid systems for sustainable chemical synthesis. It begins by discussing recent advancements in MES technologies, with critical attention to the structural limitations of biocathodes and the development of formate-mediated electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems. It then examines recent progress in semi-artificial photosynthetic systems. Emerging directions involving hydrovoltaic, piezoelectric, magnetic, and thermosensitive materials for next-generation biohybrid designs are also explored. Finally, the review considers the environmental applications of biohybrid technologies, with particular emphasis on their potential role in soil carbon sequestration.

-

MES is recognized as a promising water–energy–carbon nexus technology[46]. In its narrower sense, MES refers specifically to systems employing biocathodes that support direct microbial attachment, enabling power-to-X conversions via valorization of CO2[31]. As a representative of the third-generation (3G) biorefinery technologies[55], MES offers notable advantages, including mild operating conditions, high product selectivity for multi-electron transformations, tolerance of feedstock impurities, and extended operational stability[55,56].

Microbial catalysts in MES systems are generally categorized as either pure or mixed cultures. Mixed cultures are often considered to be more effective in enhancing MES synthesis rates, through which thermodynamically constrained end-products can be produced[36,57], while pure cultures are predominantly utilized for fundamental research, enabling the tailored production of a high-value target products, frequently without optimization of the reactor's design or operational conditions[58].

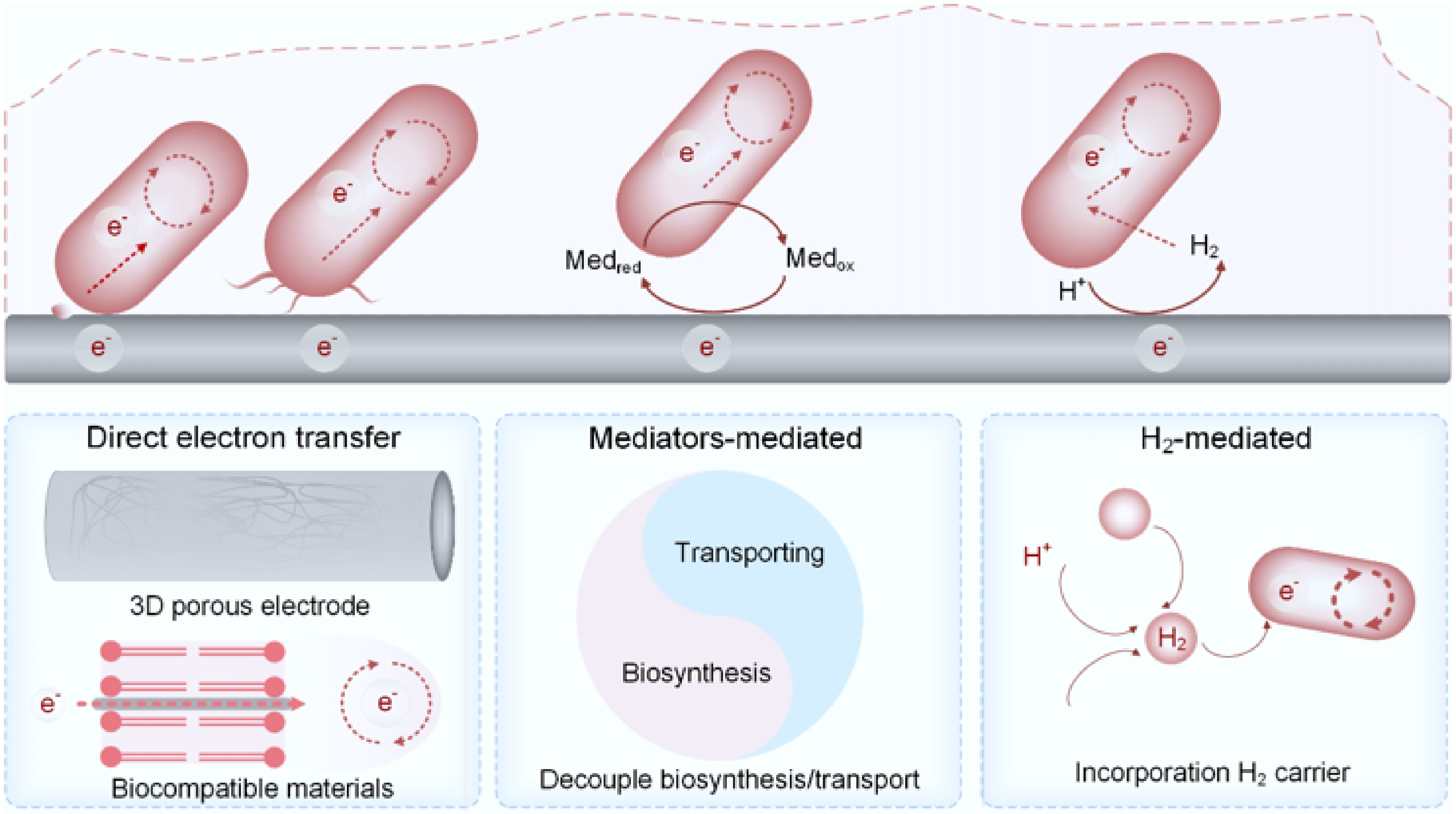

From an electron transfer perspective, MES systems can be classified into three primary types: (i) direct electron transfer (DET), (ii) mediated electron transfer using either exogenous or self-secreted redox mediators, and (iii) hydrogen-mediated electron transfer (Fig. 2)[46].

DET is typically facilitated by extracellular nanowires composed of cytochromes, enabling long-range electron transport within prokaryotic systems[34]. However, MES systems relying solely on DET generally exhibit low current densities, often an order of magnitude lower than those achieved via hydrogen-mediated pathways or by electricity-generating bioanodes[59]. This suggests that DET-based MES alone may be insufficient to fully exploit the carbon fixation potential of nonphotosynthetic microorganisms[51,60]. To address this issue, the overall approach encompasses two dimensions: (1) enhancing the interactions between microbial cells and active materials on electrode surfaces at the microscopic, molecular, or even atomic scale (that is, increasing the DET rate per cell); (2) employing three-dimensional (3D) macroscopic electrodes to facilitate microbial attachment, thereby increasing the biomass loading per unit volume (or cross-sectional area). The electrode architectures can influence electron transfer efficiency through microbe–electrode interactions. For instance, an atomic–nanoparticle bridge (CoSA@Co-NP) was meticulously engineered, and finite element analysis demonstrated that the incorporation of the underlying Co nanoparticles significantly enhances the electrode's electronegativity and electric field density[61]. This, in turn, promotes the formation of densely packed biohybrids through electrostatic interactions, while the optimized surface electronic structure facilitates efficient extracellular charge exchange and lowers the activation energy barrier, thereby enabling expedited charge transfer to the microbial counterparts. Additionally, when the atomic–nanoparticle bridge material was employed to investigate its interaction with a model methanogen, M. barkeri, it was found that the atomically dispersed Co–N4 sites provide a rapid direct electron transfer pathway by directly bonding with the molecular center of Cytochrome b (Cytb)[62]. Meanwhile, the Co nanoparticles enhance both this direct pathway and the F420-mediated electron transfer pathway through their multiorbital modulation of surface electronic structures. Other efforts to overcome these barriers have included the incorporation of biocompatible materials—such as oligoelectrolytes and silver nanoparticles—to modify cell surfaces or for intercalation into membranes, thereby lowering the activation energy barriers and enhancing CO2 fixation rates[40,63]. The use of 3D cathode materials has been proposed as a potential solution and has shown some success[64], though issues related to mass and electron transport limitations persist[65].

Mediated electron transfer offers an alternative strategy, leveraging biocompatible artificial mediators with suitable redox potentials. For systems utilizing self-produced mediators, effective control over biosynthesis and transmembrane transport is critical[66]. This decoupled approach mitigates the limitations associated with carrier synthesis and threshold tolerances, while significantly reducing electrons' translocation resistance. Notably, mediated electron transfer does not inherently require biofilm formation, suggesting that its full potential remains largely underexplored. Recent work on redox-mediated Shewanella-based microbial flow fuel cells further supports this view, demonstrating that biofilm-free systems can overcome the trade-offs typically associated with dense biofilms[67].

Considerable efforts have also been directed toward improving the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) to enhance the efficiency of hydrogen-mediated electron transfer[48,68,69], which is particularly important in single-chamber reactors inoculated with hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria (HOB), where it is critical to suppress undesired cathodic reactions involving O2, such as the formation of hydrogen peroxide[69,70]. With the creation of hydrogen-mediated electron transfer in hybrid material–microbe systems, Sporomusa ovata has shown increased levels of redox cofactors and upregulation of genes related to proton transport and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis, outperforming conventional gas fermentation systems in reducing equivalent utilization[68]. However, hydrogen-mediated MES faces persistent challenges, including low gas–liquid mass transfer efficiency, safety concerns, and the inhibition of biofilm development through the formation of hydrogen bubbles[71−74]. Strategies such as the use of biocompatible perfluorocarbon (PFC) nanoemulsions as hydrogen carriers have been shown to enhance the efficiency of acetic acid production from electricity-driven CO2 reduction[73].

In summary, since MES was first formally conceptualized in 2010, the majority of implementations have relied on biocathode-based designs[31,43,75]. Over the past 15 years, considerable progress has been made, including substantial contributions by our own group[48,51,57]. Encouragingly, recent advancements have expanded the range of MES products to include higher-value compounds such as medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs)[49]. Despite this progress, MES systems' current densities remain one to two orders of magnitude lower than those achieved in HER or CO2 electroreduction (CO2RR) systems[76]. A critical insight has emerged: unlike in CO2RR systems, where performance is typically constrained by CO2 mass transfer [a limitation that can be addressed via flow cells or membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs) with gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs)], MES systems are primarily limited by the thickness of the microbial biofilms and the intrinsic catalytic activity of the microorganisms employed[47,59].

-

Formate-mediated electron transfer has received comparatively limited attention in MES research. This phenomenon can predominantly be ascribed to the widespread utilization of electrochemically inert carbon-based electrodes or electrocatalysts that are exclusively optimized for the HER, thereby overshadowing the potential of CO2RR electrocatalysts. Most crucially, the integration of CO2RR electrocatalysts and microbial catalysts within a shared catholyte continues to pose a formidable challenge, primarily due to the inherent difficulty of preserving the activity of both catalysts under identical operational conditions.

Nevertheless, even in the absence of CO2RR electrocatalysts, some studies have demonstrated that acetogens can secrete formate dehydrogenase, which adsorbs onto graphite electrodes to catalyze formate production within a specific electrochemical window[77]. In co-culture systems, such as those comprising an iron-oxidizing bacterium (IS4) and the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii, formate has been detected as an intermediate during acetate biosynthesis[78]. Wild-type S. oneidensis strains are also capable of converting CO2 to formate[79]. Moreover, through the introduction of a reductive glycine pathway module and a C2+ product synthesis module, engineered S. oneidensis strains have been employed for malate production via bioelectrochemical CO2 reduction[80].

Recent advances in CO2RR have yielded electrocatalysts capable of selectively producing carbon monoxide (CO) and formate at current densities one to two orders of magnitude higher than those typically achieved in MES systems[81−84]. The direct electrochemical synthesis of highly reduced products (e.g., methane, acetate, ethylene) from CO2 is attractive[85], as it generally requires sophisticated and costly electrocatalysts[86]. While formate itself has a limited market price and carbon intensity[86], it is a soluble electron carrier and an easily assimilated carbon source[85], making it an ideal intermediate for electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems[47,59]. These tandem systems combine the high reaction rates of electrocatalysis with the product specificity of biocatalysis.

The first demonstration of a formate-mediated tandem system within a shared catholyte was reported in 2012[87]. In this study, a ceramic membrane separated an indium foil electrocatalyst from a Ralstonia strain, enabling the production of approximately 140 mg/L of mixed alcohol products, including 3-methyl-1-butanol and isobutanol. However, our own efforts to integrate indium foil and biocathodes within a shared catholyte resulted in severe catalyst corrosion and poor stability in the system[88].

Beyond the need for high-selectivity formate-producing electrocatalysts—such as p-block metal oxides or sulfides[86]—a major bottleneck remains the shared catholyte environment. The operational requirements of electrocatalytic and microbial processes are often fundamentally incompatible. Electrocatalysts for CO2RR typically require alkaline electrolytes, whereas microbial systems demand near-neutral pH, buffering agents, essential nutrients, and trace elements. Electrolyte composition is critical for CO2RR's performance: alkali metal ions modulate catalytic activity[84,89]; chloride ions suppress HER[90]; and cationic surfactants, such as cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), enhance CO2/H2O regulation at the catalyst interfaces[91]. Conversely, impurities such as Fe and Mn can poison catalysts[92]. Several strategies have been proposed to address these incompatibilities, including physical separation using ceramic membranes or filter papers[87,93], and direct protection of microbial catalysts with biocompatible materials such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)[94]. However, these approaches have achieved only partial success.

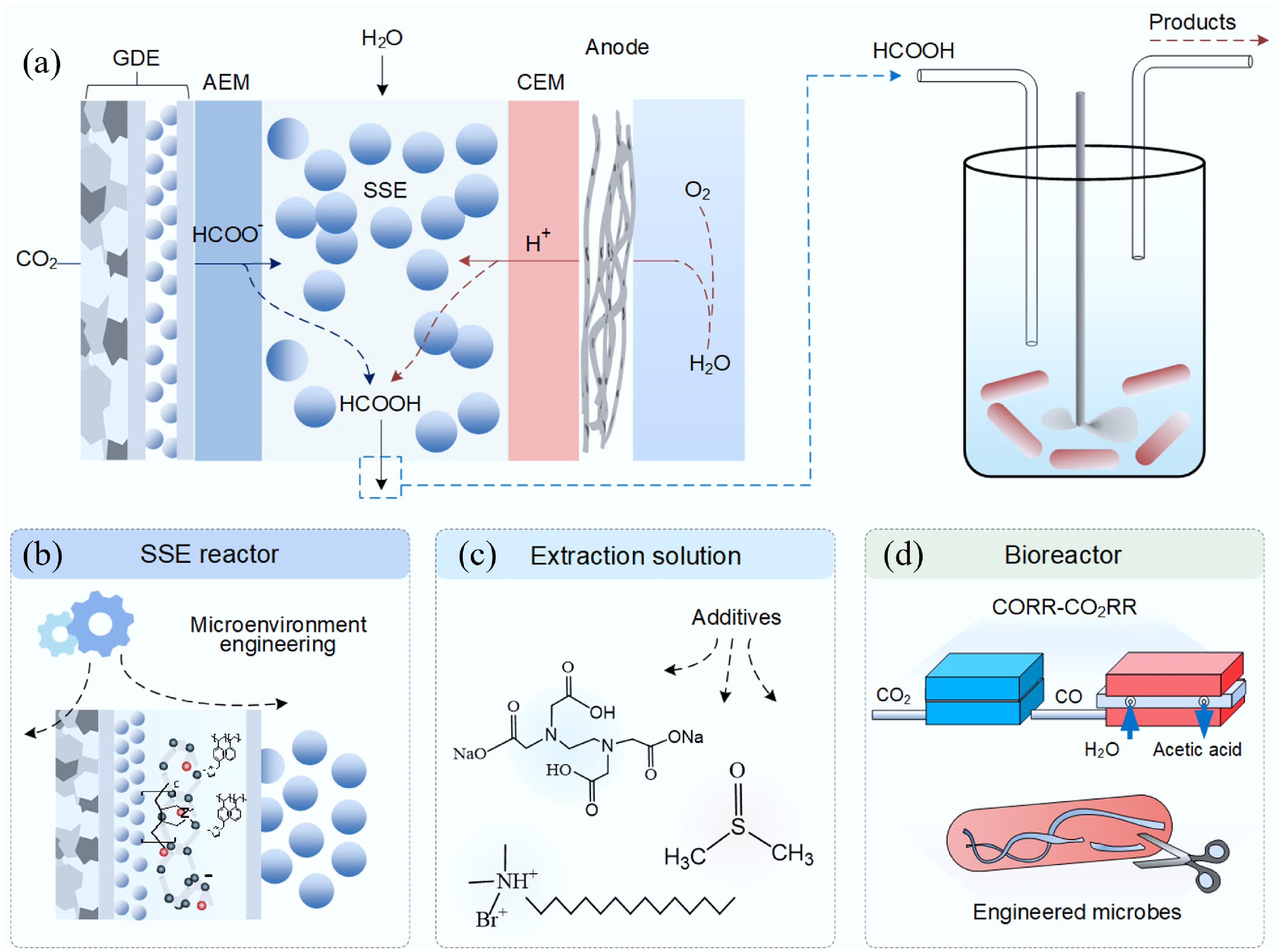

Solid-state electrolyte (SSE) reactors for electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems

Fundamental principles of SSE reactors

-

While gaseous intermediates such as H2, CO, and even CH4 have been explored in electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems[95−98], liquid-phase formate offers distinct advantages as a nexus molecule. However, formate dissolved in highly concentrated catholyte (generally > 1 M of potassium is used in CO2RR studies) can inhibit microbial activity[99]. The emergence of SSE reactors offers a promising solution to this challenge[100].

SSE reactors have been utilized across a variety of fields, including metal recovery[101], metal-free electrochemical reactions[102], local reactant concentration enhancement[103], and CO2 capture and release cycles[104,105]. They have also enabled the electrosynthesis of high-purity chemicals such as formic acid[106−113], ethanol[114,115], acetic acid[116,117], hydrogen peroxide[118−124], ammonia[102,125], and even urea[126]. These advancements suggest that SSE technology could serve as a transformative platform for sustainable chemical production[105,123]. Several recent reviews on SSE technology are recommended for further reading[127−130].

The operating principles of SSE reactors can be illustrated using the example of pure formic acid production (Fig. 3a). A cation exchange membrane (CEM) and an anion exchange membrane (AEM) sandwich an ion exchange resin layer between the anode and cathode. At the cathode, CO2 is electrochemically reduced to formate, which migrates through the AEM under an electric field. Simultaneously, protons generated at the anode migrate through the CEM. When deionized water is introduced into the SSE layer (made of ion exchange resin microspheres with a particle size ranging from tens to thousands of micrometers) as an extraction solvent, a neutralization reaction produces a concentrated aqueous formate solution.

Figure 3.

SSE-based electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems and strategies to address the associated limitations. (a) Schematic illustration of an SSE-based electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem system. (b) Rational modulation of the interfacial microenvironment to improve the CO2 reduction efficiency. (c) Application of chemical additives to enhance CO2 reduction performance, with consideration of their potential impacts on microbial metabolism. (d) Two-step conversion pathway in which CO2 is first reduced to CO, followed by microbial conversion of CO to acetate; alternatively, this process can be facilitated by genetically engineered microbial strains.

Studies and challenges in SSE-based electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems

-

SSE reactors enable the production of high-purity liquid organic acids without the need for extensive downstream separation processes[106,131], while facilitating the construction of tandem systems that couple CO2 reduction to microbial assimilation[132].

Nonetheless, several technical challenges must be addressed to enable broader adoption.

First, optimizing the CO2RR requires the deliberate modulation of the interfacial microenvironment (Fig. 3b). While high-performance AEMs (e.g., poly N-methyl-piperidine-co-p-terphenyl (QAPPT), Sustainion X37-50) have been used to ensure efficient ion transport and to increase the local alkalinity on the surface of the catalyst[124,133,134], their high cost and limited durability—particularly under the acidic conditions (pH < 2) within SSE layers—hinder their large-scale deployment[106,135,136]. A recent study observed that commercial AEMs exhibited notably distinct performances for H2O2 electrosynthesis within the SSE reactor[124]. Generally, Sustainion XC-37T demonstrated the best performance in terms of H2O2 concentration, faradaic efficiency (FE), cell voltage, and energy consumption (EC), followed by Piperion A-40, Pention 7215-30, FAA-3-50, FAA-3-PK-130, and AMI-7001, in descending order. This performance trend can be primarily attributed to the varying conductivities of the AEMs, as the resistance (Rs) for these six AEMs increased in the same sequence. Additionally, the incorporation of a SSE layer and a pair of ion exchange membranes increases the internal resistance, resulting in current densities that are often an order of magnitude lower than those achieved in flow cells or MEAs[124,130]. The extraction chamber packed with ion-exchange resin particles constitutes the most substantial contributor to the internal resistance of the SSE reactor. This can be ascribed to several key factors. First, the restricted contact area between the resin particles plays a significant role, as the compaction of these particles not only increases the pump pressure but also augments the risk of GDEs leaking. Secondly, despite the resin's ability to facilitate proton conduction, numerous studies have unequivocally shown that its proton conductivity exhibits limited effectiveness. Interestingly, this very characteristic has even been leveraged in certain research endeavors to deliberately suppress the HER[126,137]. Indeed, prior investigations have revealed that when the extraction chamber is alternatively filled with a 1 M KOH solution (in place of the ion-exchange resin particles), the observed cell voltage is approximately reduced by half[138]. It is thus challenging to standardize the SSE reactor and ensure consistent performance[139].

Second, regarding the extraction solution, while decoupling the electrochemical and biological compartments helps address any kinetic incompatibilities[132,140], systematic studies on optimized extractant formulations remain limited[130,141]. Additives such as cetrimonium bromide (CTAB), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which enhance CO2RR's performance by modulating the catalyst interfaces (Fig. 3c)[142], may influence microbial metabolism or membrane permeability, or act as competing electron acceptors when transferred into the bioreactor[143,144].

Third, from a biological perspective, not all microorganisms possess the inherent ability to directly metabolize formate, and the synthesis efficiency of high-value products in wild strains remains suboptimal, necessitating substantial enhancement. For instance, yeast typically requires acetate as a carbon source. However, the electrochemical production of acetate via CO2RR remains challenging. A promising approach involves two-step conversion process of first electrochemically reducing CO2 to CO (a reaction with high selectivity)[92,145,146], followed by reducing CO to acetate (with high carbon efficiency)[1,141]. Additionally, microbial strains have been genetically engineered to enhance their biocompatibility with electrocatalytically synthesized compounds while concurrently optimizing the efficiency of converting carbon to the final product (Fig. 3d). For example, engineered yeast strains have been utilized to convert acetate into extracellular glucose in SSE-based tandem systems[140]. Similarly, Ralstonia. eutropha can use acetate from SSE reactors to produce bioplastics[117], and an acetate/ethanol blend has been employed to support E. coli mutants engineered for the production of L-tyrosine[114].

-

Semi-artificial photosynthetic systems, which integrate biological components with semiconductor materials, offer improved solar energy conversion efficiency compared with natural photosynthesis and enable the production of high-value chemicals that are often unachievable with purely abiotic artificial systems[19]. Notably, a growing body of recent research has concentrated on enhancing the solar energy conversion efficiency of photosynthetic microorganisms, either through the development of novel electron utilization pathways or via physical protection mechanisms afforded by advanced materials. For example, photosynthetic microorganisms have been explored as candidates for constructing semi-artificial biohybrid photosynthetic systems. Under illumination, electrons released by Geobacter sulfurreducens can be utilized by the green sulfur bacterium Prosthecochloris aestuarii to drive photosynthetic processes[147]. In the absence of light, G. metallireducens can transfer electrons to the model purple non-sulfur bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris, providing the reducing power necessary for CO2 fixation[45]. More recently, living photosynthetic materials have been fabricated by immobilizing the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 within a pluronic F-127-based polymeric network. This mechanically stable 3D matrix, formed through photo-crosslinking in the presence of a photoinitiator, provided physical protection while permitting nutrient diffusion, supporting sustained cellular activity. Notably, this system enabled dual carbon sequestration via biomass accumulation and insoluble carbonate formation over a period exceeding 400 days[148]. In fact, nonphotoelectrosynthetic bacteria can be engineered into photoelectrotrophs, as demonstrated by the engineering of R. eutropha to establish a photon- and electron-harvesting system for synthesizing biomass from CO2[149].

A comparative summary of MES systems employing biocathode structures versus semi-artificial photosynthetic systems is provided in Table 1. Notably, unlike MES systems that require the deployment of both anodes and cathodes within a constructed reactor and typically depend on biofilm formation (which often entails a long startup period), semi-artificial systems can directly harness solar energy without such infrastructural constraints. Certainly, these technologies exhibit overlaps and variations that evolve from one another. For example, biocathodes operated under dark conditions can be coupled with photoanodes, using solar energy to drive electron excitation at the anode[45,150]. Biocathodes can also function under illumination when paired with photosensitizers or natural/artificial phototrophic microorganisms[151]. When semiconductors are applied as coatings on cathodes to construct photocathodes[152,153] or as photocatalyst sheets in Z-scheme systems[154], biofilm attachment may again become advantageous in semi-artificial systems, particularly to enhance electron transfer efficiency during direct extracellular electron transfer.

Table 1. Comparison of MES systems based on biocathode structures and semi-artificial photosynthetic systems

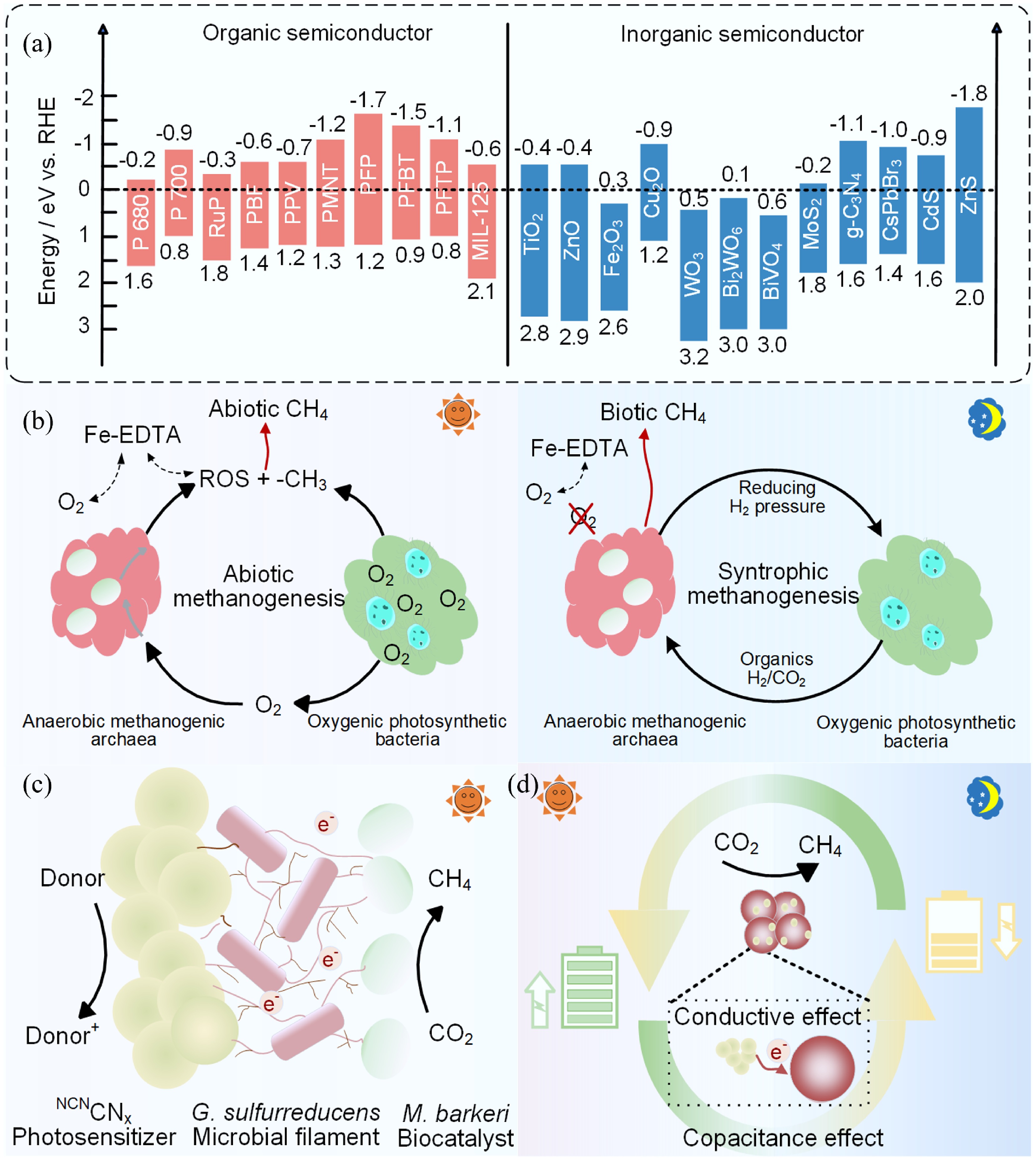

Items MES systems based on biocathode structures Semi-artificial photosynthetic systems Energy input Direct current electricity Solar Abiotic materials Electrode Semiconductor Biofilm attachment Yes Not necessary In these semi-artificial photosynthetic systems, photons with energy equal to or greater than the semiconductor bandgap induce charge separation. When the reduction potential of the semiconductor is more negative than that of outer membrane cytochromes (OMCs, −0.15 V vs. Ag/AgCl) or flavins (−0.46 V vs. Ag/AgCl), photogenerated electrons can spontaneously transfer to nonphotosynthetic microorganisms via inward EET pathways to drive metabolic synthesis[53]. These EET pathways may involve membrane-associated redox protein complexes or diffusible electron mediators such as methyl viologen or neutral red. On the basis of their energy band alignment, most semiconductors, excluding Fe2O3, WO3, and BiVO4, are theoretically suitable for direct integration into semi-artificial photosynthetic systems (Fig. 4a)[35].

Figure 4.

Representative organic and inorganic semiconductors and studies on semi-artificial photosynthetic systems. (a) The conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) of common semiconductors. Reproduced with permission from Song et al.[53]. (b) Biotic and abiotic CH4 production under anoxic dark and oxic light conditions with oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Reproduced with permission from Ye et al.[180]. (c) Engineering a microbial ecosystem to balance electron generation and utilization. Reproduced with permission from Kalathil et al.[167]. (d) Capacitive modification of biohybrid interfaces. Reproduced with permission from Hu et al.[166].

As early as 2012, it was reported that nonphotosynthetic microorganisms, such as Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and Alcaligenes faecalis, could indirectly utilize solar energy for growth via photoelectrons generated by semiconductor minerals like goethite, sphalerite, and rutile[41]. Building on this concept, a variety of biohybrid semi-artificial photosynthetic systems have been developed by combining nonphotosynthetic microbes—electroactive or otherwise—with nanomaterials. Examples include hybrids such as S. oneidensis–CdS hybrids, Moorella thermoacetica–CdS, Clostridium autoethanogenum–CdS, and M. thermoacetica–Au[155,156]. A summary of semi-artificial photosynthetic systems for chemical synthesis via CO2 valorization is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of reported semi-artificial photosynthetic systems for chemical synthesis from valorization of CO2

Microorganisms Photosensitizer Products Ref. M. barkeri CdS CH4 [163,164] M. barkeri Ni: CdS CH4 [165] M. barkeri CNx CH4 [166−168] M. barkeri EGaIn CH4 [169] M. barkeri R. palustris CH4 [170] M. thermoacetica CdS Acetate [171,172] S. ovata Photocatalyst sheet Acetate [154] S. ovata Si nanoarrays Acetate [152] S. ovata InP/ZnSe/ZnS QDs Acetate [173] C. autoethanogenum CdS Acetate [156] S. oneidensis MR-1 CdS Acetate [174] E. coli CdS Formic acid [175] Azotobacter vinelandii CdS/CdSe/InP/

Cu2ZnSnS4@ZnSFormic acid [21] Cupriavidus necator CdS/CdSe/InP/

Cu2ZnSnS4@ZnSC2H4, PHB, IPA, BDO, MKs [21] Chlorella zofingiensis Gold nanoparticles Carotenoid [158] R. eutropha g-C3N4 PHB [176] R. eutropha Organic polymer dots PHB [177] X. autotrophicus CdTe Biomass [178] Synechococcus sp. Poly(fluorene-co-phenylene) derivative (PFP) Biomass [179] Polyhydroxybutyrate, PHB; isopropanol, IPA; 2,3-butanediol, BDO; methyl ketones, MKs; polymeric carbon nitride, CNx; eutectic gallium–indium alloys, EGaIn. Although this review primarily focuses on CO2 valorization, it is important to note that organic substrates can serve as the sole carbon source, create mixotrophic conditions, or act as precursors in semi-artificial photosynthetic systems for the biosynthesis of structurally complex, high-value chemicals such as astaxanthin, shikimic acid, and carotenoids[157−159]. For instance, guided biomineralization strategies have been employed to direct the in situ synthesis of semiconductor nanoparticles within the periplasmic space of E. coli, enhancing the efficient transfer of photogenerated electrons into the oxidative respiratory chain and driving ATP synthesis. This process redirects the carbon flux of glucose metabolism from pyruvate to malate[160]. In addition, another significant application scenario of semi-artificial photosynthetic systems is hydrogen production. For instance, in the TiO2/MV/recombinant Escherichia coli (expressing [FeFe]-hydrogenase) hybrid system, the MV2+/MV+ mediator facilitates electron transfer between TiO2 and E. coli, thus promoting hydrogen production[161]. Another study delivered CuInS2/ZnS quantum dots to the periplasmic space of Shewanella, constructing a quantum-dot-photosensitized hybrid system for efficient solar hydrogen generation[162].

In addition to common organic and inorganic semiconductors, the photoelectrochemical properties of bacteria and algae have recently attracted significant attention as new photosensitizers for photogenerated electron excitation. For instance, R. palustris can harvest solar energy and conduct anoxygenic photosynthesis using sodium thiosulfate as an electron donor. When co-cultured with Methanosarcina barkeri under illumination, it can function as a living photosensitizer to drive CO2 to CH4[170]. Furthermore, studies have shown that photoelectrons generated from illuminated, nonviable cells of Raphidocelis subcapitata and Chlorella vulgaris can transfer electrons to electroactive microbes, facilitating microbial redox reactions, including methyl orange decolorization, denitrification, and hexavalent chromium reduction[181].

Several critical challenges must be addressed to advance semi-artificial photosynthetic systems:

First, conversion products may originate from both biotic and abiotic pathways. For instance, a M. barkeri–CdS photoelectrochemical system enhanced CH4 production by 1.7-fold and yield by 9.5-fold when CO was used instead of CO2, attributed to CO's ability to quench reactive oxygen species (ROS) and serve as a more direct carbon source[182]. In another example, a biofilm-based co-culture composed of Synechocystis PCC 6803, M. barkeri, and EDTA–Fe complexes demonstrated methane production via both biotic and abiotic pathways (Fig. 4b)[180]. Therefore, it is essential to distinguish between biotic and abiotic contributions when elucidating reaction mechanisms[180,183].

Second, improving the interface compatibility between abiotic materials and living cells is crucial. Ultraviolet (UV) photons can cause photodegradation of semiconductors and irreversible microbial damage. To address this, encapsulation strategies using natural luminogens and the incorporation of berberine into polymeric carbon nitride–M. barkeri hybrids have been developed, significantly boosting CH4 yields (a 2.75-fold increase)[168]. Similarly, the integration of biocompatible eutectic gallium–indium alloys with M. barkeri produced stable liquid metal nanobiohybrids, achieving over 99% CH4 selectivity across multiple operational cycles[169]. Microbial ecosystem engineering, such as introducing G. sulfurreducens KN400 to mediate electron transfer to the neighboring M. barkeri, can also address mismatches between electron generation and utilization (Fig. 4c)[167]. Alternatively, capacitive modifications using cyanamide-decorated polymeric carbon nitride (NCNCNx) enhanced photogenerated electron storage and redistribution at the biotic–abiotic interface, thereby improving the quantum yield and selectivity of CH4 (Fig. 4d)[166].

Third, it is crucial to expand cellular functionality and diversify the product spectrum. The production of high-value compounds can be achieved through C–N coupling processes. A study constructed a hybrid system by integrating the autotrophic Xanthobacter autotrophicus, which possesses the capability to fix CO2 and N2, with cadmium telluride (CdTe) quantum dots, and the internal quantum yield (IQY) of this system reached 47.2% ± 7.3% and 7.1% ± 1.1%, respectively[178]. Additionally, synthetic biology approaches have facilitated the engineering of cells that can be remotely activated via various stimuli, enabling access to diverse metabolic pathways for the production of complex biomolecules[184]. Finally, given the complexity of the processes involved, there is an urgent need to apply advanced characterization techniques to analyze mechanisms such as charge separation, interfacial electron transfer, and microbial metabolism[53].

-

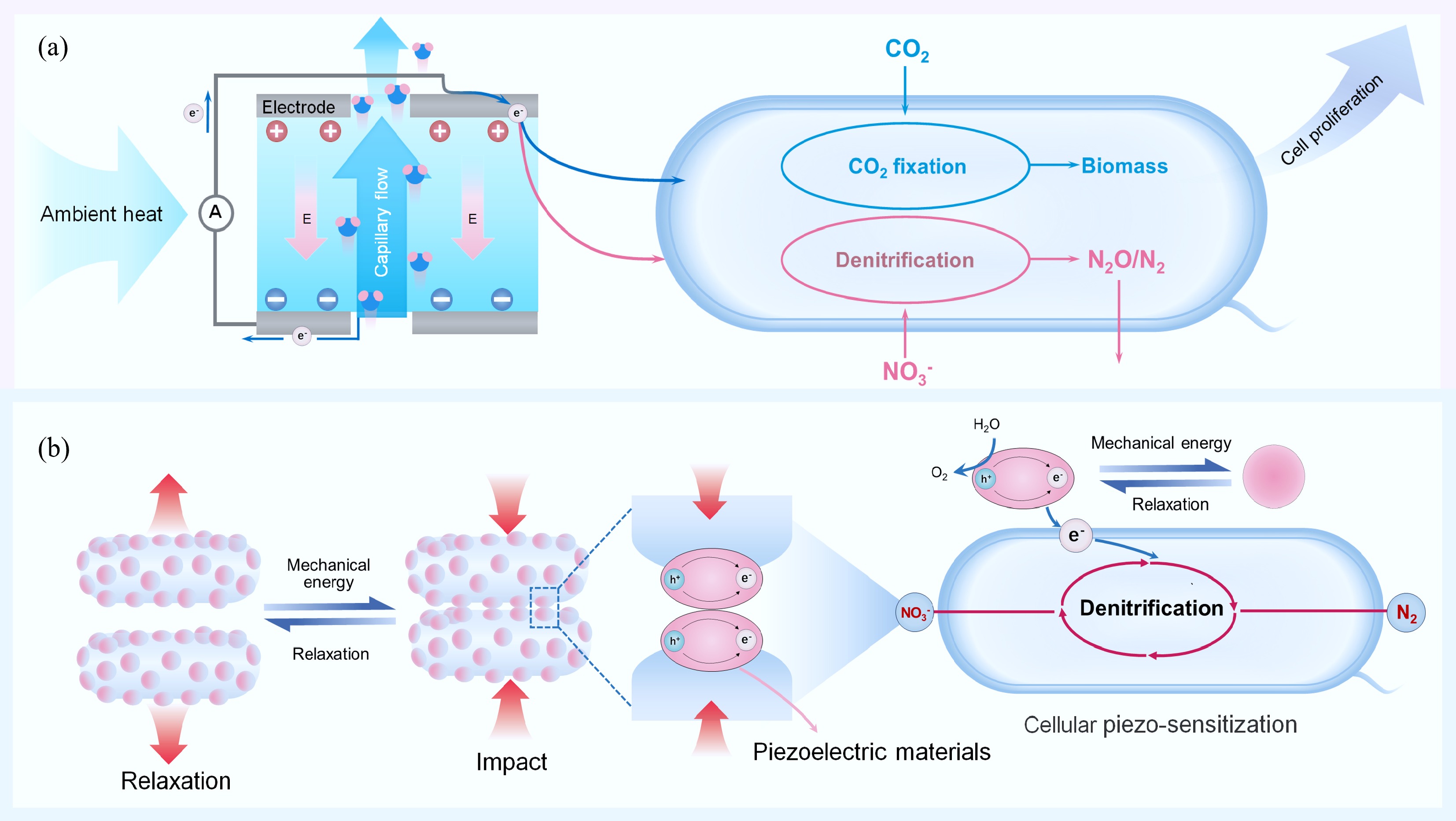

Nanostructured materials can generate electricity through interactions with water, a phenomenon known as the hydrovoltaic effect. This emerging approach enables energy harvesting from natural processes within the Earth's water cycle—including raindrops, waves, evaporation, and atmospheric humidity—offering innovative solutions to challenges in climate, energy, and water management[185,186]. Notably, hydrovoltaic devices utilizing nanomaterials have demonstrated significantly enhanced performance[187].

Recently, biological materials such as proteins, cells, biofilms, and even whole plants have attracted increasing interest for hydrovoltaic power generation. For example, thin-film devices composed of nanometer-scale protein wires derived from G. sulfurreducens have been shown to generate continuous power via a self-sustained moisture gradient, achieving a steady voltage (~0.5 V) and a current density of ~17 µA/cm2[188]. Similarly, a prototype based on G. sulfurreducens biofilms achieved continuous power generation with a peak output of approximately 685.12 µW/cm2, attributed to the biofilm's hydrophilicity, porosity, and conductivity[189]. Our group recently reported a transpiration-driven generator (LTG), which harnesses the hydrovoltaic effect in plant transpiration to capture latent environmental heat for sustained electricity production[190].

Hydrovoltaic electrons can also be directly harnessed by electroactive microorganisms. For instance, R. palustris was shown to grow within biofilms by capturing evaporation-induced electrons via extracellular electron uptake, with carbon fixation coupled to nitrate reduction (Fig. 5a)[191]. Under similar conditions, Thiobacillus denitrificans and M. thermoacetica also exhibited significant growth, while electroheterotrophic bacteria such as S. oneidensis and G. sulfurreducens maintained metabolic activity without cellular proliferation. In contrast, nonelectroactive strains such as E. coli and Bacillus subtilis showed neither growth nor viability. These findings suggest that, with proper metabolic and electron utilization pathway design, hydrovoltaic electrons could be effectively harnessed in biohybrids for sustainable chemical synthesis, rather than biomass accumulation.

Figure 5.

Biohybrids with hydrovoltaic energy and mechanical energy input. (a) Schematic diagram of hydrovoltaic electron generation within a biofilm supporting microbial growth. Reproduced with permission from Ren et al.[191]. (b) Schematic diagram of mechanically driven denitrification. Reproduced with permission from Ye et al.[192].

In parallel, there is growing interest in nanostructured piezoelectric semiconductors, which have revealed novel phenomena arising from the coupling of piezoelectric polarization and semiconductor properties[193]. Despite these advances, the direct application of mechanical energy to drive microbial metabolism remains relatively unexplored. A recent study demonstrated that mechanical agitation-induced strain in piezoelectric materials generates free charges that can be transferred via surface enzymes and proteins into microbial intracellular nitrate reduction pathways, enabling mechanically driven denitrification (Fig. 5b)[192].

-

This review examines biohybrid systems used for sustainable chemical synthesis through the lens of different energy input modalities, providing an overview of recent advancements, identifying key challenges, and proposing potential solutions. To further advance the field, we highlight the urgent need for a deeper understanding of the interactions between abiotic materials and microbial systems, as well as the exploration of additional viable energy conversion pathways. These efforts will be instrumental in broadening the applicability of sustainable biohybrid technologies across a range of environmental contexts.

First, understanding the interaction between abiotic materials and microbes is essential for the creation of biohybrid systems. For example, S. oneidensis MR-1 donates electrons from lactate metabolism to fill photoholes in hematite, while hematite photoelectrons reduce hexavalent chromium, enhancing microbial tolerance and remediation capacity[194]. Another study showed that the anoxygenic phototrophic sulfur bacterium Chlorobaculum tepidum directly interacts with pyrite surfaces, secreting organic compounds that modify the mineral interface[195]. The presence of pyrite significantly upregulated the genes involved in photosynthesis, sulfur metabolism, and organic compound biosynthesis, while downregulating iron transporter proteins. In summary, understanding the interaction between abiotic materials and microbes is a complex task, involving various energy input forms, different electron transfer mechanisms, and responses at multiple biological levels. This complexity requires the application of interdisciplinary knowledge and techniques, including bioinformatics, materials science, theoretical calculations, and in situ spectrum imaging.

Secondly, there is an urgent need to explore additional forms of energy input for the construction of biohybrid systems for sustainable chemical synthesis. In this review, we primarily focused on energy modalities such as direct current electricity, solar, hydrovoltaic, and mechanical energy. It is worth noting that biological components can respond to a wide range of external stimuli. For instance, magnetic materials have been utilized to stimulate electron transfer at material–biology interfaces, particularly in nanobiotechnology-based bacterial therapies and microrobotic applications[196−198]. Examples include an extremophile-based biohybrid micromotor powered by acidophilic microalgae operating under extremely low pH conditions[199], and algae-driven microrobots capable of delivering drug-loaded nanoparticles for the treatment of lung metastases[200]. However, the use of magnetic fields in biohybrids for sustainable chemical synthesis remains underdeveloped. One report indicated that exposure to dynamic magnetic fields enhanced methane emissions from sediments, likely due to increased electron exchange among extracellular respiratory microorganisms[201]. Whether this enhancement results from magnetic field-induced electron transfer at the material–biology interface remains to be elucidated.

Thermosensitive materials have been employed to create material–biological interfaces, enabling precise temperature monitoring in living organisms. For example, they have been used to accurately monitor and adjust the internal temperature of solid tumors during photothermal therapy (PTT)[202]. Additionally, thermosensitive materials have facilitated continuous and precise body temperature monitoring through the development of hybrid biodegradable and bioresorbable temperature sensors and e-skins[203]. Recently, a study reported that tungsten disulfide (WS2) can either precipitate on the cellular surface or be internalized by the cells of Thiobacillus denitrificans, generating pyroelectric charges that act as reducing equivalents to drive bio-denitrification[204]. This finding demonstrates the application potential of thermosensitive materials in biohybrids for sustainable chemical synthesis.

Thirdly, the expansion of sustainable energy technologies across diverse environmental scenarios is necessary. Biohybrids have demonstrated considerable potential in wastewater treatment and show promising prospects for soil carbon sequestration. However, their application in the remediation of gaseous pollutants and solid waste remains largely underexplored.

In wastewater treatment, for example, T. denitrificans has been shown to utilize dissolved organic matter (DOM) as a microbial photosensitizer, enabling nitrate reduction and producing nitrogen gas as the final product[27]. Additionally, photoelectrons from both biogenic and abiogenic sphalerite nanoparticles have been found to enhance the activity of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans G20 for reducing sulfate and lead removal without the need for organic substrates, a long-standing challenge in sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB)-based applications for heavy metal remediation[29]. Mechanically driven biodenitrification has also been successfully implemented, achieving up to a 117% increase in nitrate removal efficiency[192]. Notably, by engineering microbial cell factories, abiotic components recovered directly from wastewater can be valorized to enable the scalable synthesis of biohybrids for the conversion of organic pollutants into value-added chemicals[205].

Another particularly promising avenue is the application of biohybrids for soil carbon sequestration, which presents further opportunities for investigating the role of formate. Inspired by natural soil's composition and functions, a bottom-up fabrication strategy has been employed to develop synthetic soil chemical systems, effectively modulating the microbial community's distribution and activity in vitro[206]. A self-sustaining "geo-battery" was constructed using iron minerals to mediate electron transfer, where the charging process drives CH4 oxidation and the discharging process drives CO2 reduction, offering a promising strategy for mitigating soil greenhouse gases[150]. Formate, a key small organic molecule, plays a central role in biogeochemical processes and can be synthesized abiotically through photoelectrocatalysis[207,208], water–rock interactions[209,210], and hydrothermal reactions[211,212]. Formate is secreted across all three major biological kingdoms—animals, plants, and microorganisms—and is involved in a wide array of biogeochemical cycles[212]. As discussed earlier, in the field of green chemical engineering, formate has received significant attention as a "nexus molecule" for constructing SSE-based electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems. We therefore propose that collaboration between soil minerals and nonphotosynthetic microbes may drive the development of formate-mediated carbon fixation technologies, with potential applications in energy and the environmental.

-

This review highlights the emerging role of biohybrid systems in sustainable chemical synthesis and outlines several critical challenges that must be addressed to advance the field. MES systems based on biocathode architectures commonly suffer from low current densities and necessitate the use of both anodes and cathodes within complex reactor configurations. However, the recent development of SSE reactors presents promising opportunities for the construction of more efficient formate-mediated electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems. Key obstacles limiting the progress of semi-artificial photosynthetic biohybrids include the need to elucidate complex photochemical mechanisms and electron transfer pathways, the optimization of interfacial compatibility and charge transfer kinetics between abiotic and biotic components, and the development of advanced microbial engineering strategies to expand the diversity of biosynthesized products. Notably, biological components, ranging from proteins to whole cells and biofilms, have exhibited hydrovoltaic effects, suggesting new avenues for designing self-powered biohybrid systems. Moving forward, a deeper understanding of the interactions between abiotic materials and microbial systems, along with the development of alternative energy input modalities such as mechanical, magnetic, and thermal energy, will be essential. While biohybrids have demonstrated considerable potential in wastewater treatment, their applications in the remediation of gaseous pollutants and solid waste remain largely underexplored. Furthermore, biohybrid systems, particularly those optimized for formate-mediated electron transfer, show significant promise in advancing soil carbon sequestration technologies.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiang Y, Zhou S; data collection: Jiang Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Jiang Y, Zhou S, Ren G, Zhang Y, Liang P; draft manuscript preparation: Jiang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42525702, 52370033) and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024J010021).

-

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Shungui Zhou is the Associate Editor of Energy & Environment Nexus who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer-review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

-

Biohybrids employ abiotic materials to tap diverse energies for biosynthesis.

Biocathode limitations and formate-mediated tandem reactions were reviewed.

Solar-powered semi-artificial photosynthetic systems were covered.

Abiotic-microbial interactions, energy form, and applications were outlooked.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang Y, Ren G, Zhang Y, Liang P, Zhou S. 2025. Biohybrids for sustainable chemical synthesis. Energy & Environment Nexus 1: e003 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0002

Biohybrids for sustainable chemical synthesis

- Received: 02 June 2025

- Revised: 05 July 2025

- Accepted: 10 July 2025

- Published online: 22 September 2025

Abstract: Amid rising global energy demands and mounting environmental challenges, the development of sustainable chemical synthesis technologies has become increasingly imperative. Biohybrid synthesis systems present a promising pathway by integrating abiotic materials capable of harnessing diverse energy sources—including direct current electricity, solar radiation, hydrovoltaic, and mechanical energy—to generate excited electrons that drive the metabolic activities of various biological components. This review first examines recent advances in microbial electrosynthesis (MES) technologies that utilize poised electrodes to replicate the activated abiotic materials capable to excite electrons. Special emphasis is placed on the structural limitations of biocathodes and innovations in formate-mediated electrocatalytic–biocatalytic tandem systems. Additionally, the review highlights progress in semi-artificial photosynthetic systems that utilize whole cells to directly capture solar energy for the biosynthesis of value-added chemicals. Emerging frontiers in biohybrid design are also explored, with a focus on the incorporation of hydrovoltaic and piezoelectric materials. The review further underscores the critical importance of understanding the interactions between abiotic materials and microbial systems, and discusses the potential of alternative energy modalities for constructing biohybrids, along with their applications in diverse environmental contexts. In conclusion, this work offers timely insights into cutting-edge technologies at the intersection of energy and environmental science, contributing to the advancement of sustainable chemical synthesis for a more resilient future.