-

In the global energy consumption structure, traditional fossil energy occupies a considerable proportion, exerting significant pressure on the environment and having a major impact on economic development[1,2]. Therefore, the development of both environmentally friendly and economically viable renewable energy sources is becoming increasingly attractive. As the only renewable carbon-containing resource in nature, biomass is an excellent raw material for the production of sustainable fuels and high-value chemicals. Large-scale utilization of biomass resources helps to optimize the energy structure, stabilize economic growth, and promote the sustainable development of the ecological environment[3,4]. Lignocellulosic biomass is the most abundant biomass resource in nature, consisting of cellulose (35%–50%), hemicellulose (20%–35%), and lignin (10%–25%), and has a wide range of application prospects[5]. Among them, lignin is a reticulated polymer formed by phenylpropane structural units through C–O ether bonds and C–C bonds, and is the only natural polymer with a large number of aromatic ring structures[6]. Due to its complex structure, lignin usually needs to be depolymerized at high temperatures, but its depolymerization products have low yield and poor selectivity, which represents a bottleneck for the efficient application of lignin[7−9]. Currently, cellulose and hemicellulose have been commercially utilized in the paper making, biodiesel, and bioethanol industries, while lignin has long been used as a by-product as a low-grade boiler energy[10−13]. Converting lignin to aromatic products would greatly increase the commercial viability of biorefining. Therefore, the research on depolymerizing lignin and producing high-value products is also gaining attention.

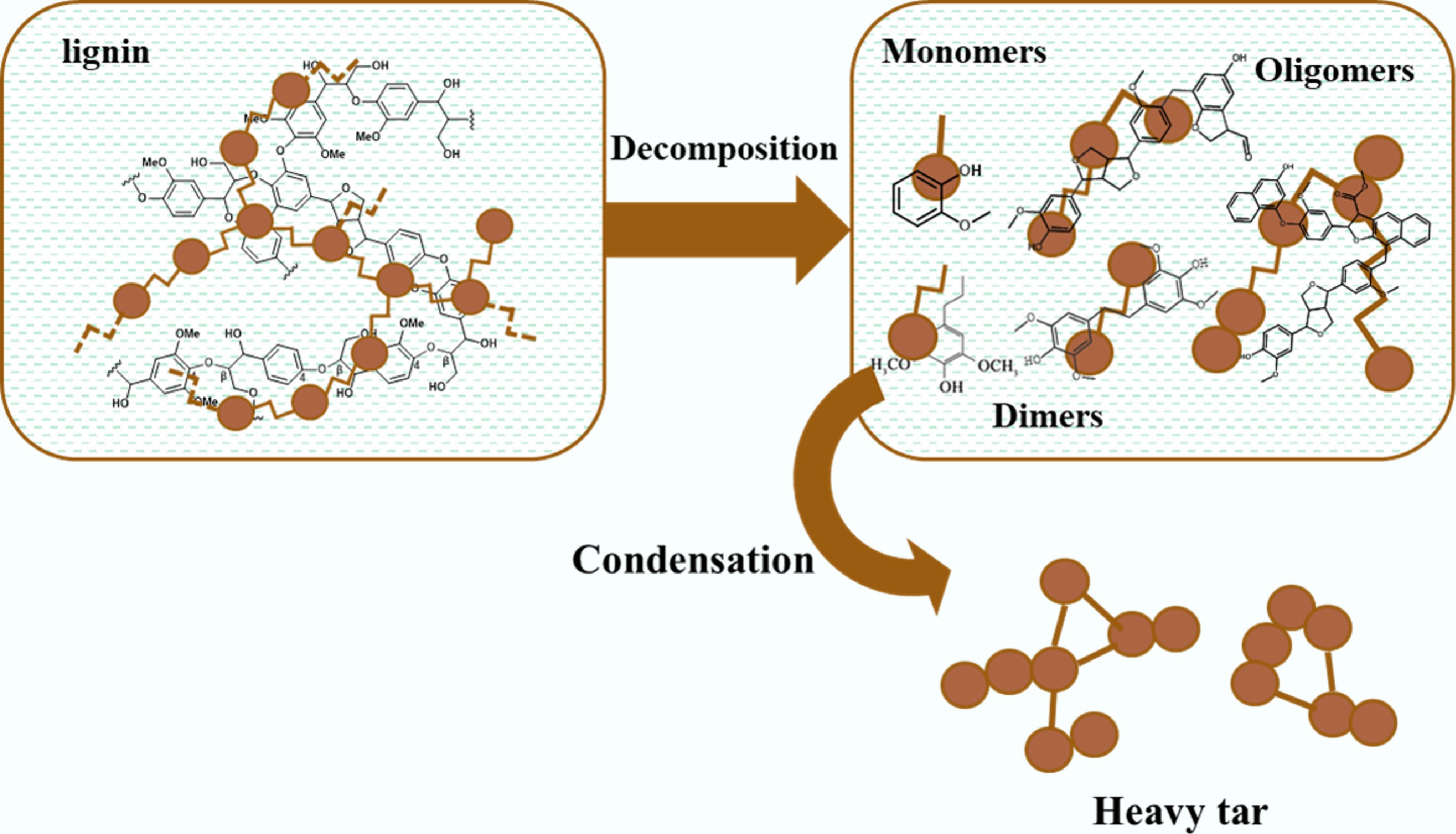

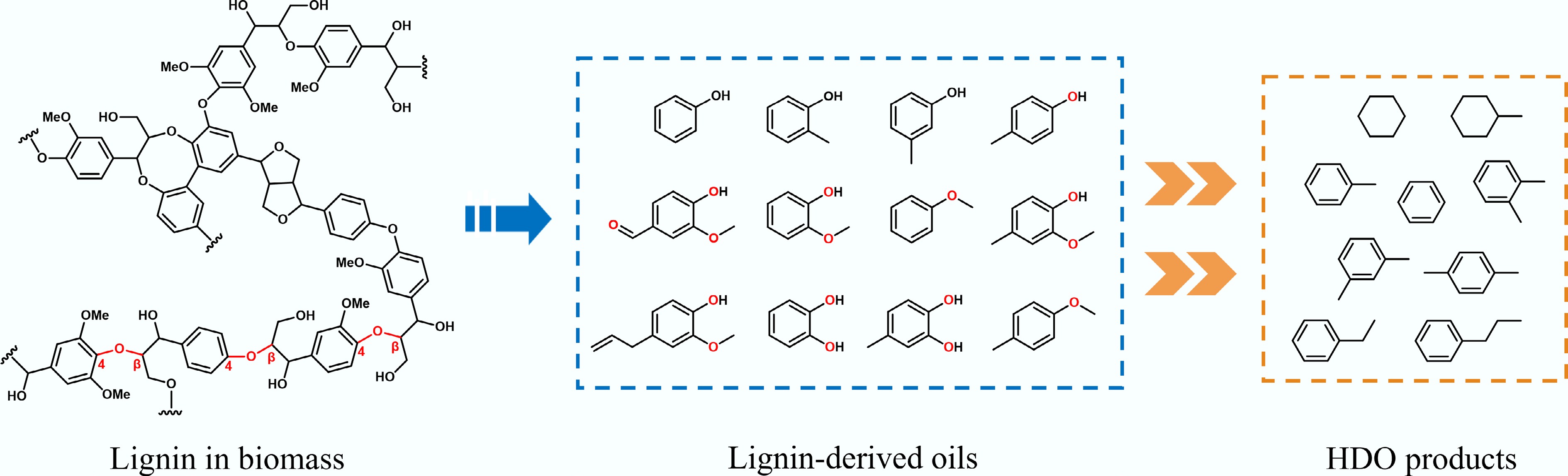

Various methods such as reductive depolymerization, pyrolysis, acidolysis, and enzymatic hydrolysis have been developed for the utilization of lignin to maximize its depolymerization into monomeric aromatic compounds[9,14,15]. The products of lignin depolymerization are usually called lignin-derived bio-oils, which are mainly composed of phenolic monomers (phenol, guaiacol, and eugenol, etc.), dimers, and oligomers (Fig. 1)[16]. These substrates serve as the primary feedstock for conversion into high-value-added chemical products[17]. However, lignin-derived phenolics contain abundant oxygen-containing functional groups, which are primarily bonded to aromatic rings and are challenging to eliminate[18]. This results in drawbacks including high oxygen content, low calorific value, high viscosity, and poor stability, all of which make lignin-derived oil unsuitable for direct use as fuel or as a fuel blending component[19−24]. Therefore, hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) under suitable reaction temperature and external H2 has been considered as an efficient method for the upgrading of lignin-derived complex mixtures.

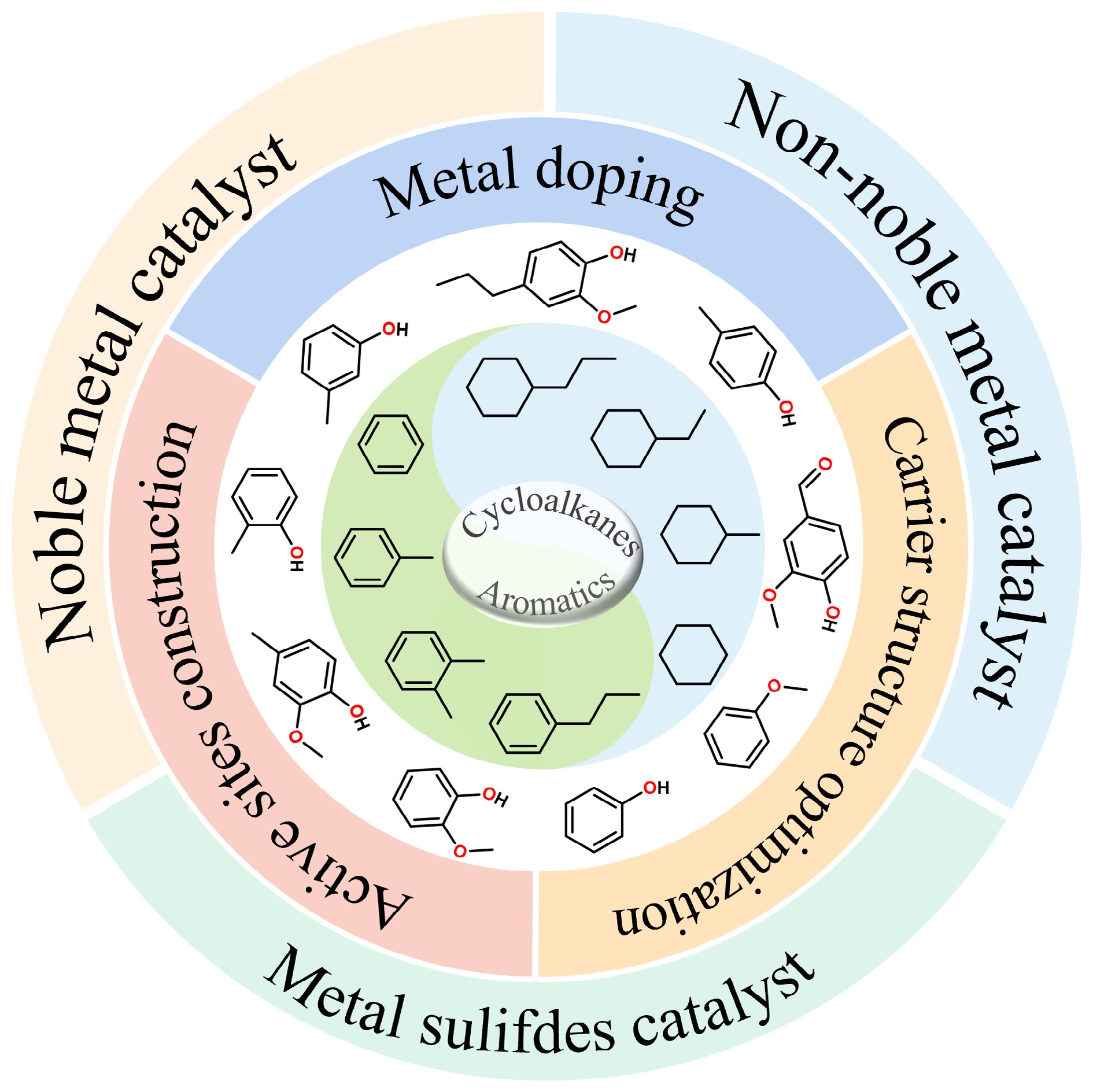

The HDO process is usually accompanied by a series of reactions, including direct deoxygenation, aromatic ring hydrogenation, dehydration, C-C hydrogenolysis ring opening, and transalkylation etc. (Fig. 2). The specific types of reactions depend on temperature, pressure, and the structure of the catalyst[25,26]. So far, researchers have mostly studied lignin-derived phenolic model compounds (guaiacol, phenol, and cresol, etc.) rather than structurally complex bio-oils[27,28]. Considering that the bond energy of Caryl-OR (R: H, methyl or phenyl) is relatively higher, it is challenging to break this bond in HDO reactions[29−32]. HDO has been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in the conversion and upgrading of lignin and its derivatives. Although numerous excellent reviews have extensively summarized the current HDO reactions, there is still a need for a deeper review and discussion of the catalyst structure modulation strategies and the product selectivity of lignin-derived phenols. In this review, the adsorption models and HDO reaction pathways of lignin-derived phenols are first summarized, and then the mechanisms of the influence of different active sites in the catalysts on the HDO reaction are investigated, followed by a discussion of the relationship between catalyst structure modulation and the HDO reaction.

-

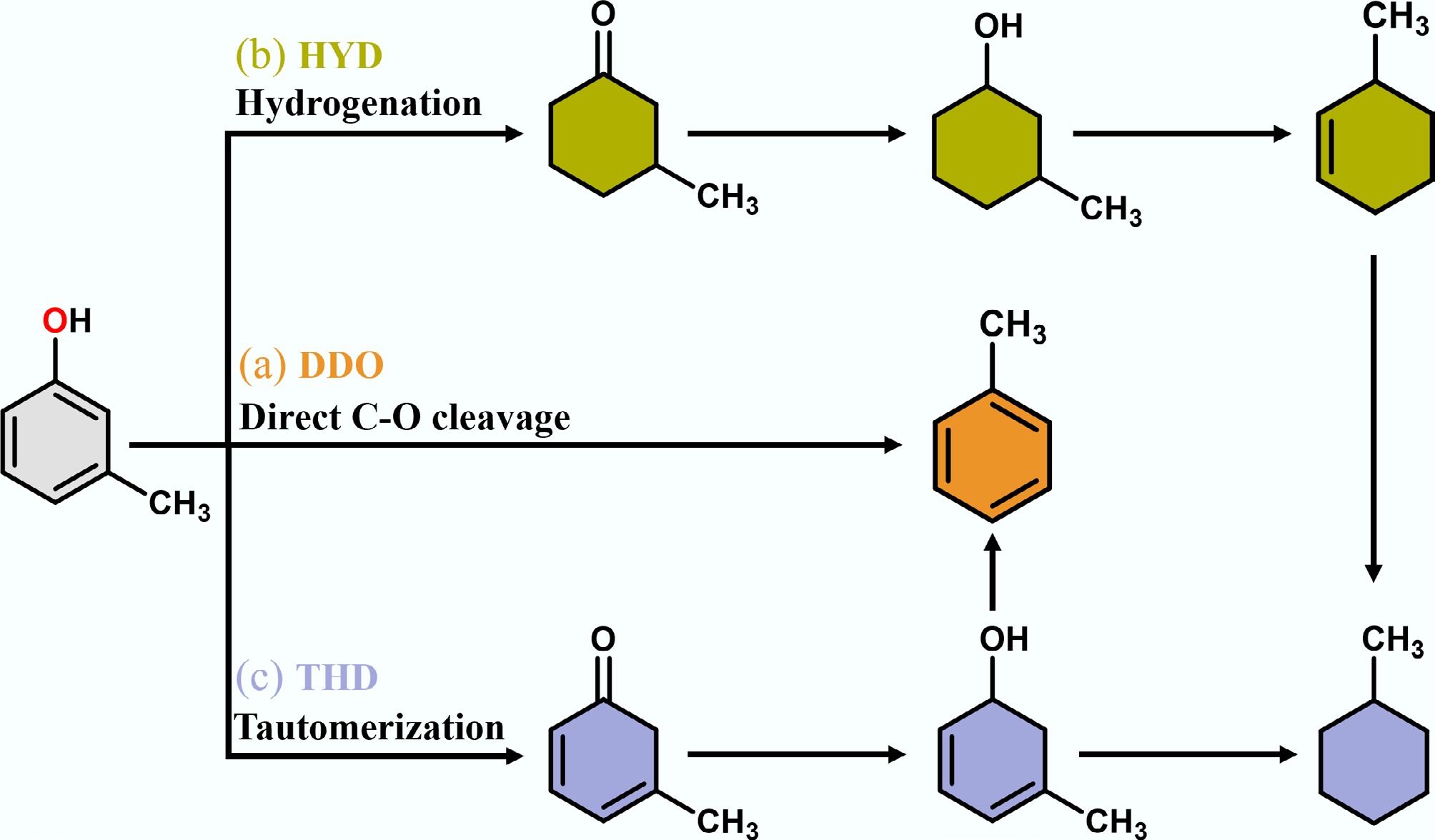

In general, the HDO reactions of lignin-derived phenolic compounds usually follow three main catalytic pathways: (a) direct C–O bond breaking (DDO); (b) aromatic ring hydrogenation (HYD); and (c) tautomerization (THD) (Fig. 3)[33]. Taking m-cresol as an example, path (a) involves breaking the carbon-oxygen bond while keeping the aromatic ring unchanged, resulting in toluene and water. However, as mentioned above, the C-O bond energy in the aromatic ring is high and it is challenging to break this bond. Path (b) first undergoes the hydrogenation of the aromatic ring to form the intermediate product methylcyclohexanone, followed by further hydrogenation and dehydration to obtain methylcyclohexanol, ultimately producing the cycloalkane product methylcyclohexane. Similar to path (b), path (c) also undergoes hydrogenation of the aromatic ring followed by dehydration, and the products contain methylcyclohexane and toluene, with the main difference being that the initial stage of path (c) undergoes reciprocal isomerization. Furthermore, in path (c), due to the poor thermodynamic conditions for the dehydrogenation of methylcyclohexene to toluene, high-pressure H2 favors the formation of the hydrogenation product methylcyclohexane[31,34−37]. Although all three pathways ultimately result in the further conversion of phenols to aromatics or cycloalkanes, product selectivity remains highly contingent on variations in temperature, pressure, and catalyst architecture.

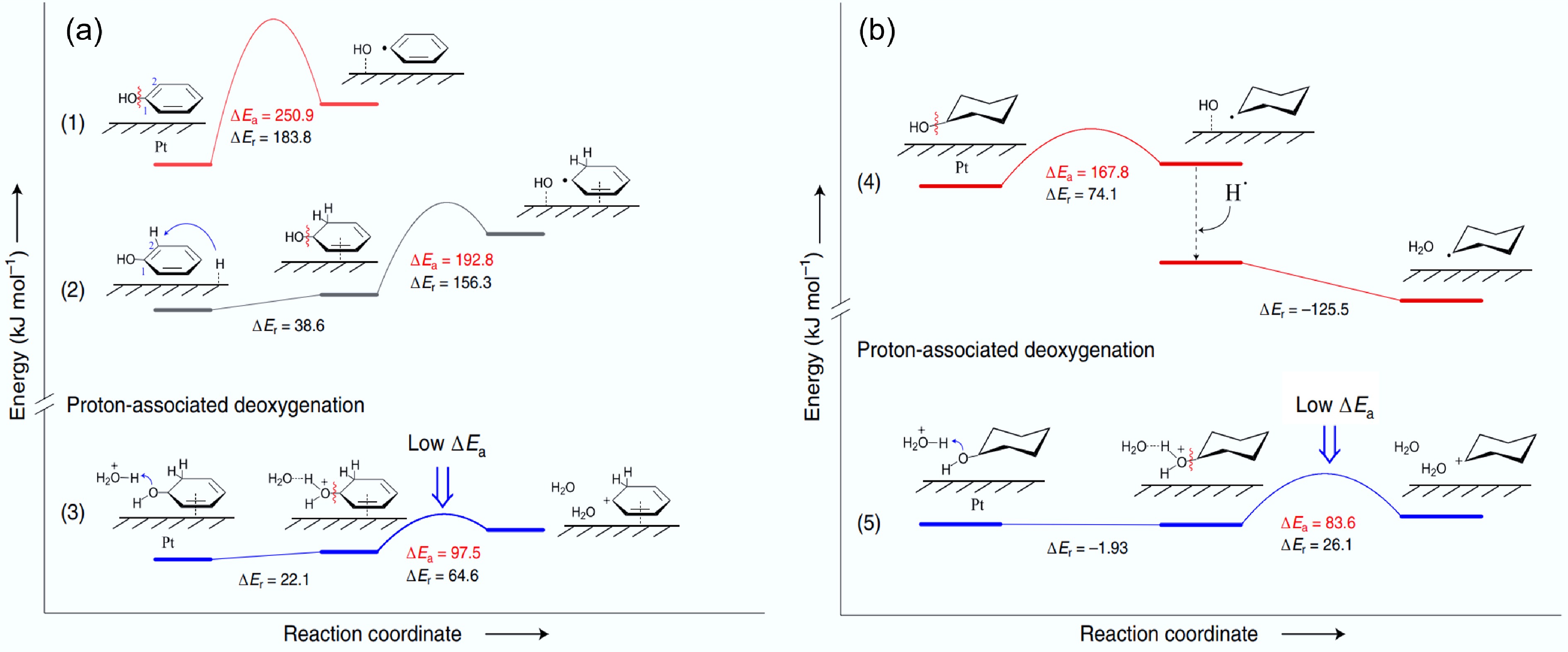

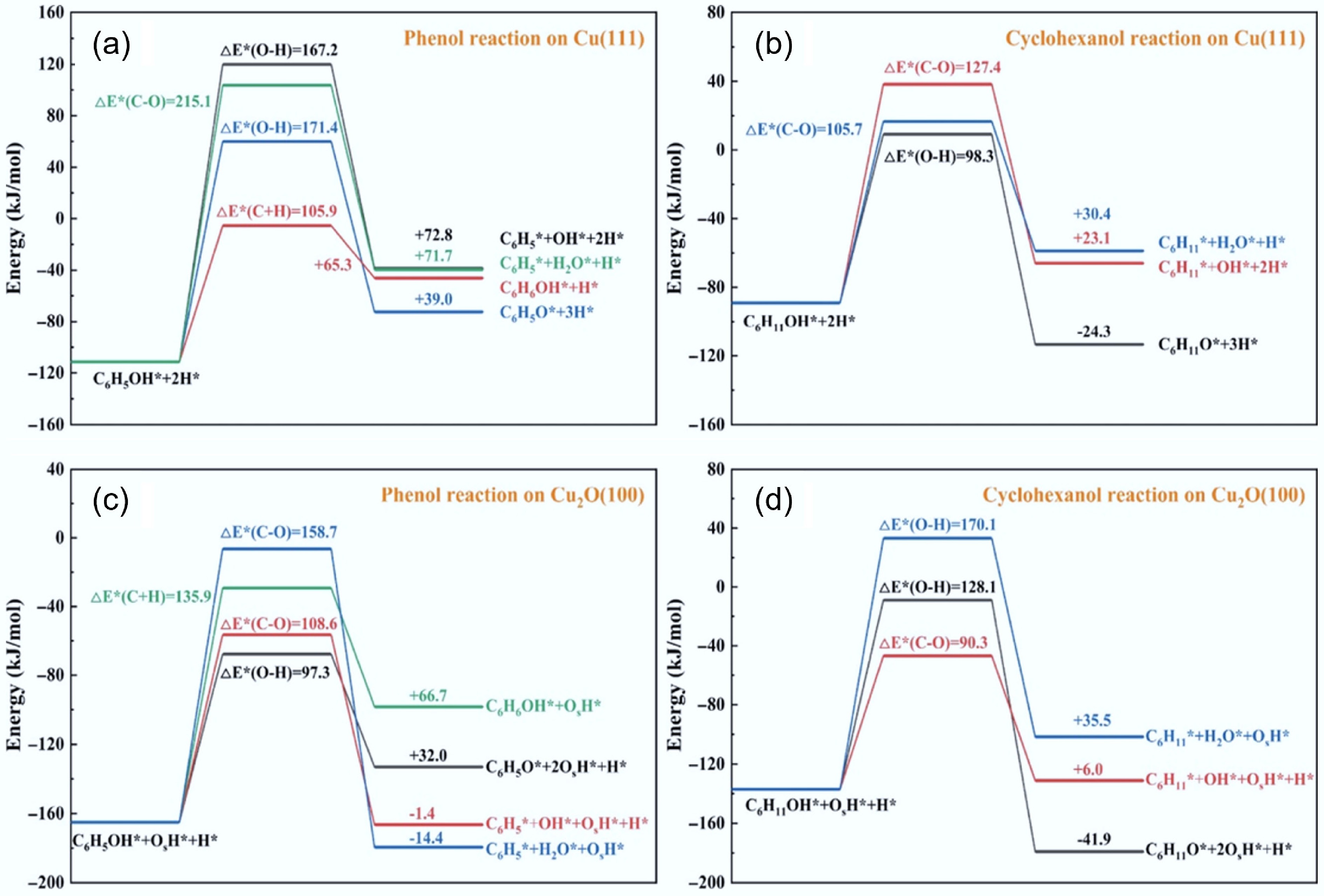

A wide range of biomass-derived substrates has been tested in the HDO reaction. Due to their relatively simple structure, phenol is often used as a reaction substrate, and valuable products such as benzene and cyclohexane are generated during the HDO. Based on the mechanism of benzene formation from phenol HDO in a SiW12-Pt/C catalyzed system at low temperature, three different C–O bond breaking paths were proposed in conjunction with density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Meanwhile, the presence of Pt also makes it possible for phenol to preferentially undergo hydrogenation to produce cyclohexanol, and the breaking of the C–O bond is the main challenge that constrains the generation of cyclohexane (Fig. 4)[38]. The conversion of cyclohexanol to cyclohexane determines the reaction rate of phenol HDO, where the synergistic interaction between Cu0 and Cu+ plays a crucial role in this process[39]. The Cu (111) surface is covered with hydrogen atoms, where Cu0 adsorbed phenol forms a C–H bond, has the lowest activation barrier (105.9 kJ/mol), which is the main reaction pathway, and thus the Cu0 site is more active in the aromatic ring hydrogenation of phenol to produce cyclohexanol. However, the dehydration of cyclohexanol on the Cu+ species on the Cu2O (100) surface to generate cyclohexyl intermediates is the main reaction step with an activation barrier of 90.3 kJ/mol, followed by a rapid hydrogenation to cyclohexane with an activation barrier of 88.2 kJ/mol (Fig. 5). The monometallic Cu is capable of both saturating and deoxygenating aromatic rings. As a representative of bio-oil compounds containing Caryl-O-C bonds, anisole is also frequently used as a model compound in the HDO process, where four main reaction pathways occur: hydrogenation, hydrolysis, demethylation, and transalkylation. Guaiacol is one of the most widely used phenolic model substrates, containing three distinct types of C–O bonds. As a complex model compound, guaiacol can represent lignin and its many derivatives[40,41]. In early HDO studies, guaiacol typically yielded a range of valuable chemicals including catechols, methylation products, and deoxygenation products such as phenol, benzene, cyclohexanol, and cyclohexane[42].

Figure 4.

Energy profiles of possible C–O bond breaking pathways for (a) phenol, and (b) cyclohexanol in HDO on the Pt (111) surface. ΔEr: reaction energy, ΔEa: activation energy. Reproduced with permission[38]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature.

Figure 5.

(a) Phenol and (b) cyclohexanol reaction over Cu (111), and (c) Phenol and (d) cyclohexanol reaction over Cu (111) Cu2O (100) surfaces. Reproduced with permission[39]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

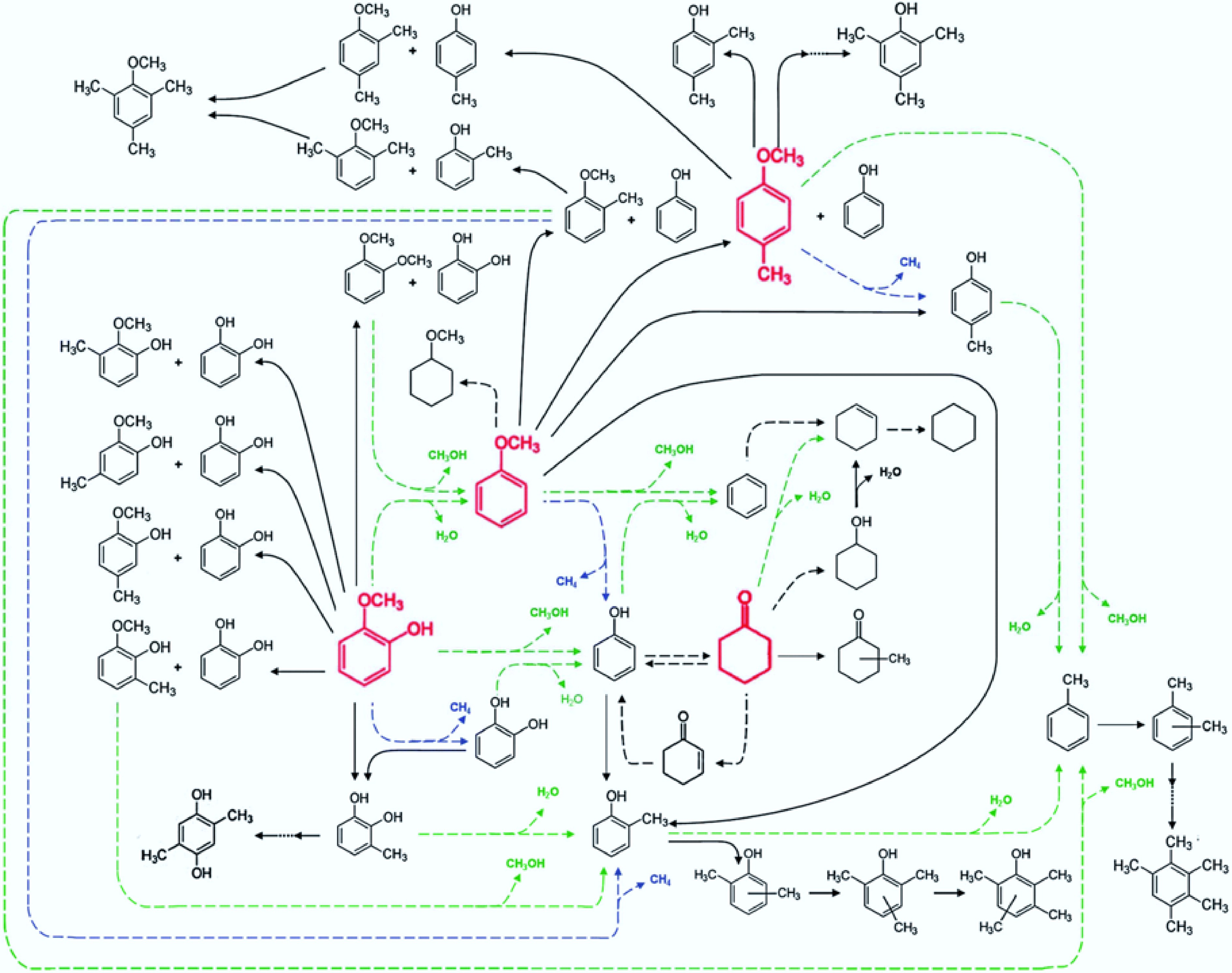

The study of reaction mechanisms is complicated by the increase of oxygen-containing functional groups in model compounds and the existence of more potential reaction pathways. Runnebaum et al.[43] analyzed the HDO products of Pt/γ-Al2O3 catalysts at 573 K and postulated possible reaction pathways for lignin-derived representative compounds (Fig. 6), including the above-mentioned guaiacol, phenol, anisole, and other reaction intermediates (cyclohexanone and 4-methylanisole). The reaction pathway of guaiacol is more complex than those of other phenolic compounds, and its pathway contains both phenol and anisole reactions. This is mainly due to the presence of three different types of C-O bonds in guaiacol, which are also present in phenol and anisole, respectively. When one of these functional groups undergoes direct hydrogenolysis, phenol or anisole is obtained. Although the components of bio-oils are very complex and include a range of compounds containing other functional groups in addition to the derivatives mentioned above, It generally follows the above deoxidation reaction pathways and depends on the structure of the substances themselves. It is believed that this proposed reaction pathway diagram is informative for most catalysts, and it also illustrates the feasibility of choosing lignin-derived compounds as a substitute for bio-oil for the performance evaluation of HDO reactions.

Figure 6.

Reaction pathway for the conversion of lignin-derived compounds under Pt/γ-Al2O3. Reproduced with permission[43]. Copyright 2012, Royal Society of Chemistry.

-

The design and synthesis of catalysts featuring high activity, selectivity, and stability represent the core challenge for enhancing the efficiency of the HDO reaction. The following section Table 1 summarizes HDO catalysts reported in recent years, particularly focusing on the effects of active metal sites, acid sites, and modulation of interfacial properties on catalyst activity and hydrodeoxygenation reaction pathways of metal catalysts. Although high temperature facilitated the rate of the HDO reaction[44], coke tended to form on the surface of the catalyst at high temperature to deactivate the active sites. Besides, the catalyst itself could also be deactivated due to sintering. Therefore, research activities are focused on catalysts that significantly reduce the reaction temperature and are highly resistant to carbon deposition[32,37,45−47]. Since the HDO process has multiple reaction pathways, unique catalysts should be designed to modulate the active sites of the catalysts to generate aromatic hydrocarbons or cycloalkanes with high selectivity. This review summarizes the recent progress of metal sulfides, noble metals, and non-noble metal catalysts in HDO and the corresponding modulation strategies, including second-metal doping, active-site construction, and optimization of the carrier structure. This paper provides guidance on regulating the selectivity of the HDO reaction and delivers insights into catalytic mechanisms for the rational design of highly efficient and selective HDO catalysts toward aromatic hydrocarbons or cycloalkanes production.

Table 1. HDO of lignin-derived model compounds over heterogeneous catalysts

Catalysts Reaction conditions Substrate Conv. (%) Products Sel. (%) Ref. T (°C) P (bar) Solvent FMoS2 300 30 decalin p-cresol 69.6 toluene 87.2 [48] SMoS2 300 30 decalin p-cresol 98.7 toluene 83.1 [48] Co-FMoS2 180 30 decalin p-cresol 21.0 toluene 98 [48] Co-SMoS2 180 30 decalin p-cresol 97.6 toluene 98.4 [48] CoS2/MoS2 220 30 dodecane p-cresol 58.9 toluene 95.2 [49] Co-Mo-S 220 30 dodecane p-cresol 88.5 toluene 97.4 [49] Mo0.06−Co9S8/Al2O3 265 40 − DPE 99.8 benzene 91 [50] Pt-Mo-200 120 50 − p-cresol 100 MCH 96.3 [51] Pd/m-MoO3−P2O5/SiO2 110 10 decalin phenol 100 cyclohexane 97.5 [52] Pt-WO3-x 230 30 n-hexane phenol 99 cyclohexane 94.3 [53] Ru/TNP 250 10 octane guaiacol 99.9 cyclohexane 100 [54] Ru/C-HPW 200 10 octane guaiacol 100 cyclohexane 92.1 [55] Ru@H-ZSM-5 150 50 water phenol 60 cyclohexane 51 [56] Pd-ZrO2 300 1 − m-cresol 14.7 toluene 87.9 [57] Pd-ZrO2 300 1 − phenol 77 benzene 66 [58] Pt-WOx/C 300 36 dodecane m-cresol 61 toluene 98 [59] Br-Ru/C 120 5 methanol DPE 99.8 benzene 44.7 [60] Ni-Co-NbOx 300 30 dodecane guaiacol 100 cyclohexane 98.9 [61] Fe-ZrO2 300 40 octane guaiacol 17.1 cyclohexane 0.4 [62] FeNi-ZrO2 300 40 octane guaiacol 100 cyclohexane 89.4 [62] Ni/SiO2 340 40 dodecane m-cresol 19.6 MCH 63.6 [63] Ni/ZrO2 340 40 dodecane m-cresol 18.2 MCH 56.8 [63] Ni2P/SiO2 340 40 dodecane m-cresol 20.2 MCH 62.9 [63] Ni2P/ZrO2 340 40 dodecane m-cresol 20.9 MCH 74.3 [63] Ni2P/SiO2 250 30 dodecane m-cresol 94.7 MCH 96.3 [64] Ni15Fe5/ZrO2 300 20 n-hexane p-cresol 98.1 MCH 68.7 [65] Ni15Co5/ZrO2 300 20 n-hexane p-cresol 100 toluene 34.9 [65] 5% Ni/SiO2 300 1 − m-cresol 95.6 toluene 67.6 [66] Ni-Mo/SiO2 350 1 − m-cresol 95 toluene > 80 [67] Metal sulfides

-

Metal sulfide catalysts were initially mainly applied in hydrodesulfurization (HDS) and hydrodenitrogenation (HDN) processes in petroleum refining[68]. Due to their high hydrogenation activity, researchers also explored the performance of sulfide catalysts in the HDO of lignin-derived phenols[69]. In particular, MoS2-based catalysts have made great progress, and with further research, an increasing number of metal sulfide catalysts have been designed and developed to enhance the HDO reaction rate.

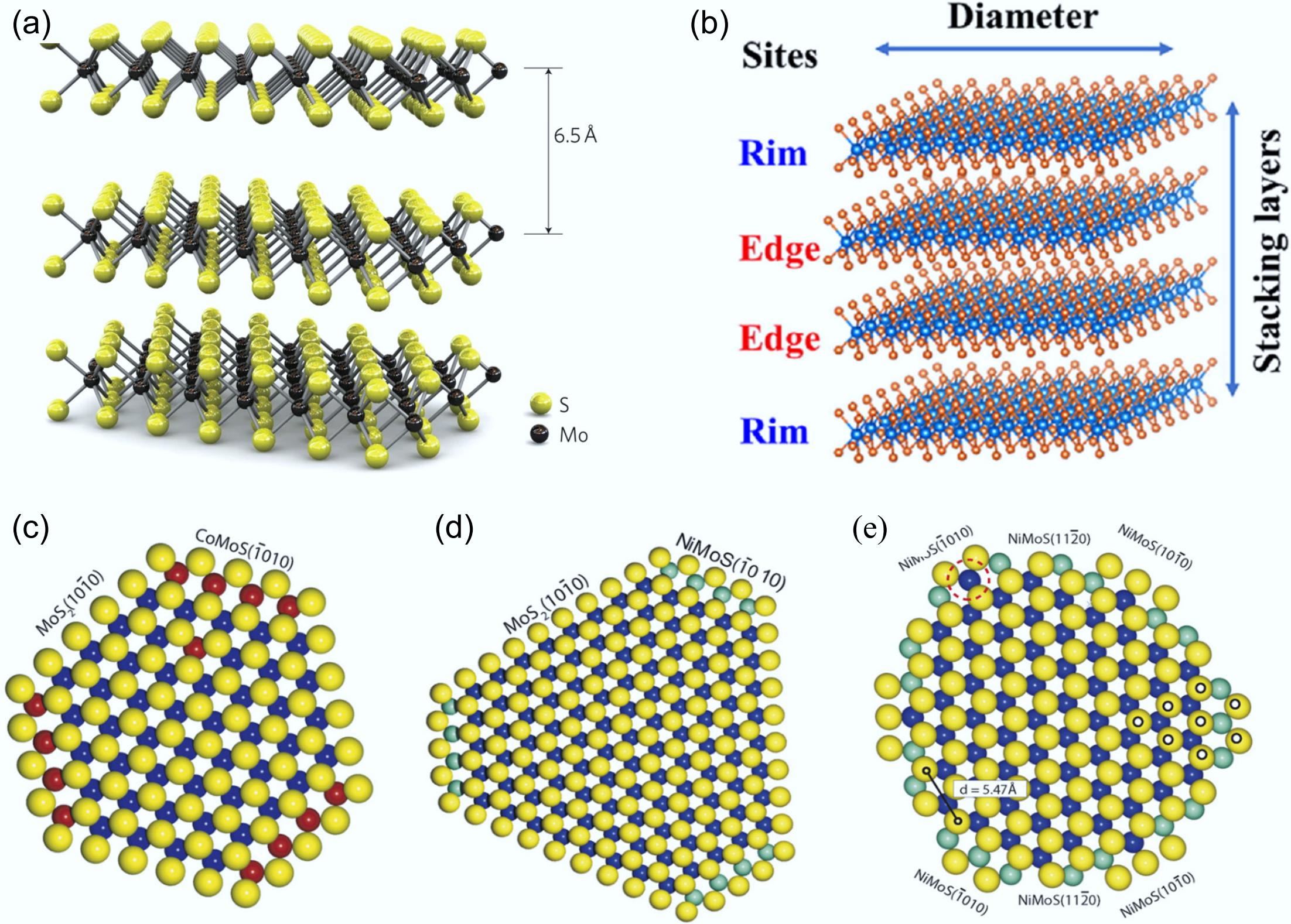

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) is a crystal structure consisting of vertically stacked S-Mo-S layers that are held together by van der Waals forces[70,71]. Mo atoms and S atoms are arranged in a weakly interacting S-Mo-S layer through a hexagonal lattice arrangement. Each S atom is coordinated to three Mo atoms in monolayer MoS2 (layer thickness 6.5 Å), with a standard Mo-S bond length of 2.42 Å (Fig. 7a)[70,72]. Since the sandwich structure of the S-Mo-S layer results in anisotropic crystals, researchers have proposed four MoS2 polycrystalline types, 1T MoS2, 1H MoS2 (the most stable), 2H MoS2, and 3R MoS2[73]. Numerous experiments have confirmed that the high catalytic activity of MoS2 mainly originates from the formation of S vacancies on its edge sites, thus exposing unsaturated ligand Mo atoms[70,74,75].

Figure 7.

(a) Three-dimensional model of the MoS2 structure. Reproduced with permission[70]. Copyright 2011, Springer Nature. (b) Rim-edge model of an MoS2 catalytic particle. Reproduced with permission[76]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. Ball model of (c) Co–Mo–S, (d) type A Ni–Mo–S, (e) type B Ni–Mo–S. S: yellow, Mo: blue, Co: red, Ni: cyan. Reproduced with permission[77]. Copyright 2007, Elsevier.

Three main structural models have been put forward to elucidate the catalytic properties of MoS2, including the rim-edge model[78], remote control model[79], and Co-Mo-S model[77]. The Rim-edge model was first proposed by Daage et al. in the HDS reaction of dibenzothiophene(DBT), which describes a multilayer sulfide with different average stacking layers (Fig. 7b)[78]. Hydrogenation of the aromatic ring primarily took place at the rim sites on account of their higher coordinative unsaturation, whereas hydrogenolysis occurred at both the rim and edge sites. Wang et al. applied a hydrothermal method to synthesize MoS2 catalysts with different stacking numbers[80]. It was demonstrated that increased stacking layers in catalysts led to improved DDO selectivity, while MoS2 with fewer stacked layers exhibited a preference for the HYD pathway. The synergistic interaction between the doping of a second metal and MoS2 can be aptly interpreted by the remote control model put forward by Delmon & Froment[79]. Their hypothesis suggested that the catalytic activity and selectivity of bimetallic MoS2 catalysts stemmed from synergistic interactions between two coexisting phases. Specifically, the synergistic interaction between CoSx and MoS2 was commonly referred to as the remote-control model.

The Co-Mo-S model was first proposed by Lauritsen et al.[77], and it currently stands as the most widely accepted model in the field of HDO reactions. This model employed sulfur vacancies as active sites for selective deoxygenation, where enhanced catalytic activity and aromatic selectivity were achieved through increasing surface sulfur vacancy density[81]. It is generally believed that the addition of Co to MoS2 can improve the HDO activity. Co atoms are located at the edge of MoS2 and provide electrons to Mo for chemical interaction, which weakens the Mo–S bond at the Co-anchoring position and promoted the elimination of S[31]. Through combined scanning tunneling microscopy (STM), and density functional theory (DFT) studies, Topsøe's research group conducted in-depth investigations into the atomic-scale structure of Co/Ni-promoted MoS2 nanoclusters. They determined that the Co-Mo-S phase presented a sub-hexagonal morphology, with Co atoms preferentially localized at the (1(-)010) edge featuring a 50% S coverage (Fig. 7c). According to the STM images of the Ni-Mo-S phase, type A (larger MoS2 nanoclusters) had similar features to the Co-Mo-S phase (Fig. 7d), while type B (smaller MoS2 nanoclusters) showed a dodecagonal shape with three different edges at the end (Fig. 7e).

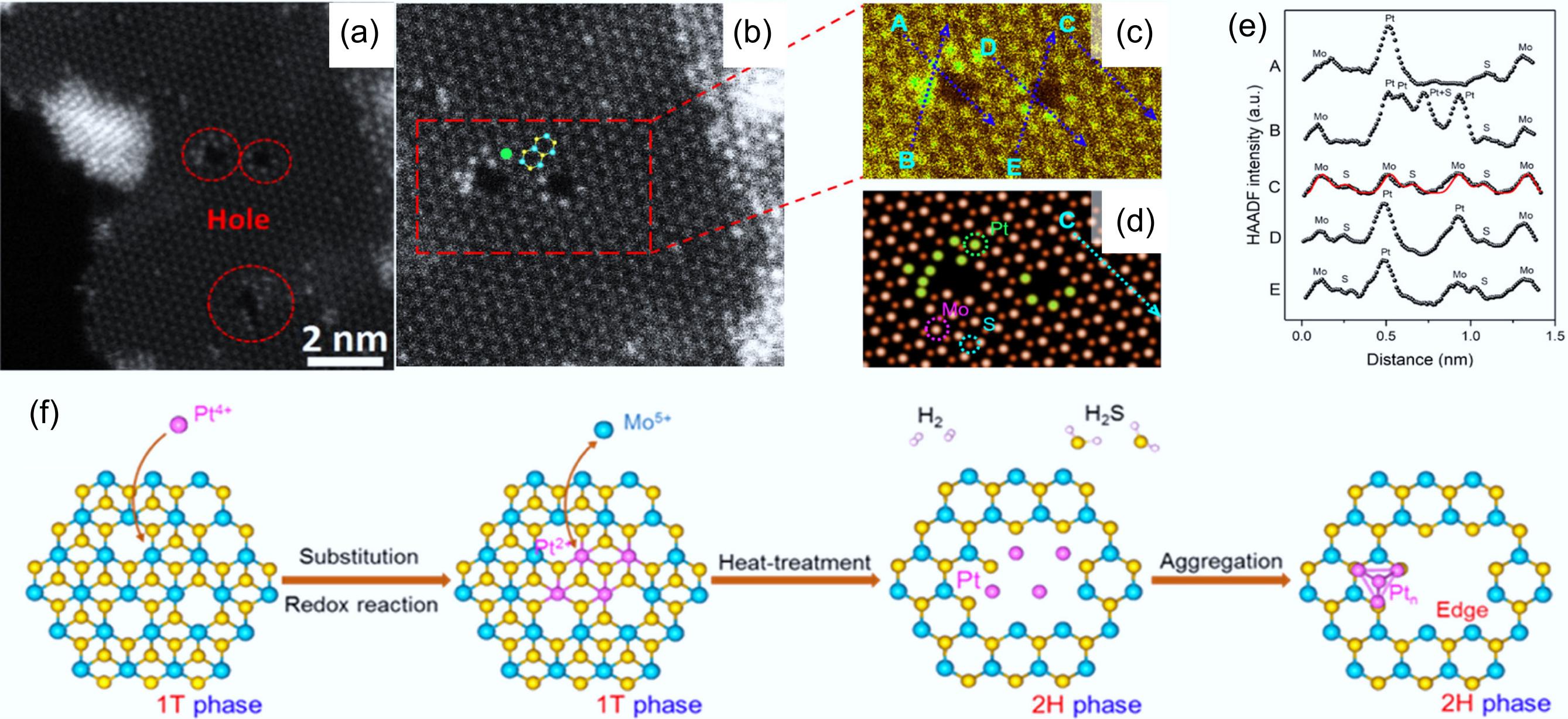

Metal-doped MoS2 catalysts are currently one of the most promising materials for HDO reactions. Doped metals like Pt and Ni with excellent hydrogen dissociation abilities tend to undergo cyclohydrogenation reactions, allowing selective preparation of cycloalkane products under mild conditions[38,82]. The noble metal Pt is highly prone to sulfidation under H2S exposure, resulting in severe catalyst deactivation[83]. To significantly improve the activity of MoS2, Wu et al. devised a novel metal insertion-deinsertion strategy for the synthesis of the Pt-MoS2-x catalyst[51]. During the formation of Pt-MoS2-x, Pt4+ initially undergoes partial substitution for Mo atoms in the basal plane of the 1T-phase. Subsequently, Pt is deinserted from the basal plane, yielding isolated Pt atoms and generating new edge sites on the basal plane of the 2H-phase. This process achieves activation of the inert basal plane (Fig. 8a). The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) results proved that Pt species existed in the form of Pt-O and Pt-Pt bonds in the Pt-Mo-200 spectrum, compared to the PtS2 standard sample, where Pt was present as Pt-S. This indicated the cleavage of Pt–S bonds and the formation of metallic Pt nanoparticles at the edge position of the basal plane. This observation aligned with the results obtained through high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) analysis (Fig. 8b-f). In the HDO process of p-cresol, the catalyst achieved 100% deoxygenation at a low temperature of 120 °C, and with a 96.3% yield of methylcyclohexane. Almost no S loss or deactivation was observed in the stability tests.

Figure 8.

(a) Pt-Mo-200, and (b), (c) enlarged HAADF-STEM images. (d) Simulated high-resolution HAADF-STEM results for Pt-Mo-200. (e) Measurement of the intensity profiles of the four lines labeled in (c) and (d). (f) Schematic of the synthesis of Pt-MoS2-x catalyst. Reproduced with permission[51]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society.

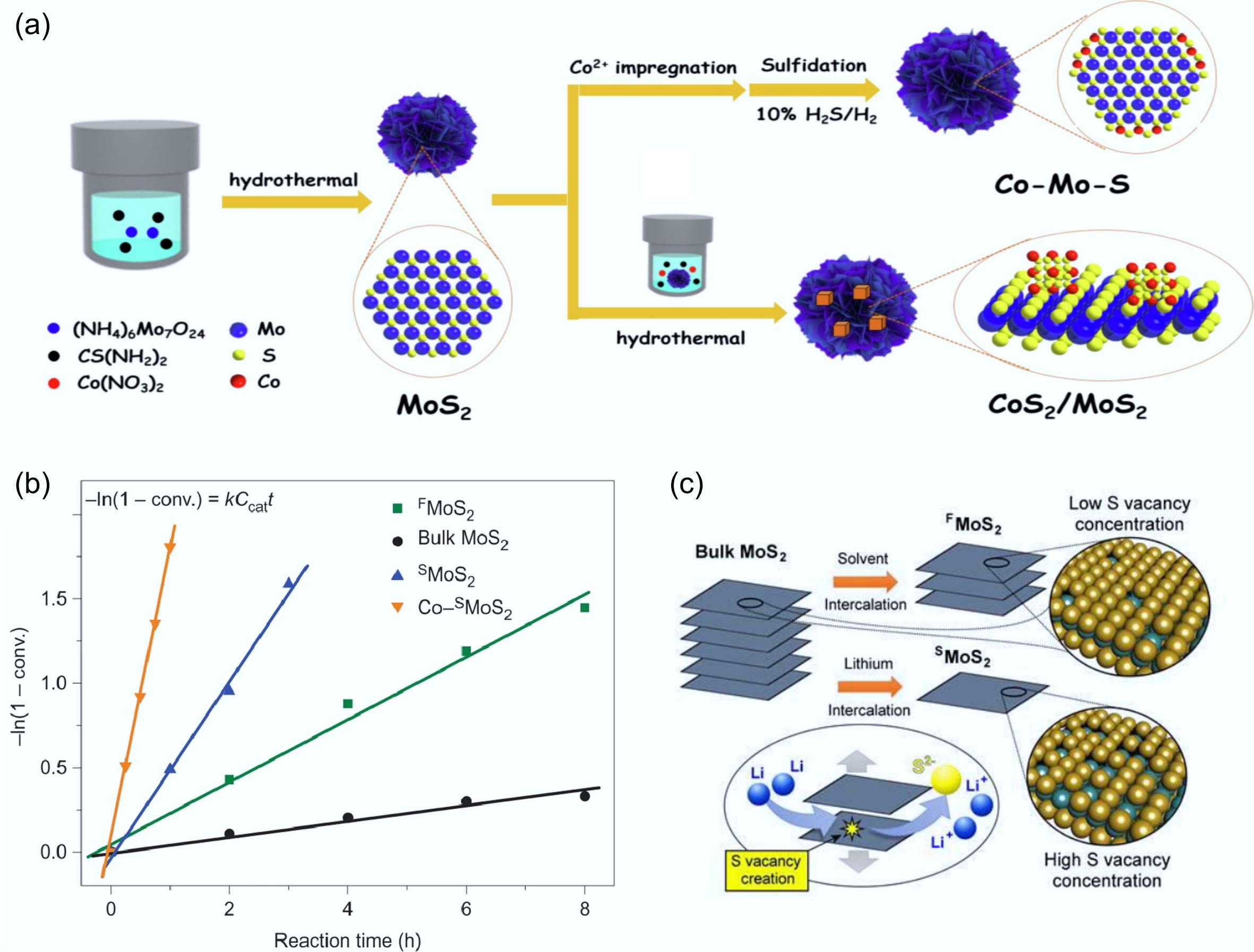

The incorporation of Co can alter the morphology, structure, and electron cloud density distribution of MoS2. This modification significantly increases the number of S vacancies on the surface of the Co-Mo-S phase, leading to the formation of more active sites[76]. This led to enhanced selectivity in the conversion of lignin derivatives to aromatics, accompanied by high hydrodeoxygenation activity and outstanding stability[84,85]. In their investigation of m-cresol hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) performance, Cao et al. developed two Co-doped MoS2 model catalysts (Fig. 9a), with the active phase structure being characterized through X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses[49]. The results demonstrated that the Co-Mo-S phase catalyst exhibited notably higher HDO activity compared to the CoS2/MoS2 catalyst, achieving a conversion of 88.5% and a toluene selectivity of 97.4%. The high activity of the Co-Mo-S phase was attributed to the significant weakening of the Mo–S bond, which promoted the formation of new S vacancies at the Co-Mo-S interface and improved the reaction rate and aromatic selectivity of the DDO pathway. In addition, Liu et al. synthesized a novel catalyst by dispersing Co species on a MoS2 monolayer. They mixed the prepared MoS2 monolayer with thiourea-based Co species to covalently bind Co atoms to sulfur vacancies on MoS2[48]. The monolayer MoS2-based catalysts synthesized exhibited superior activity, selectivity (99.2%), and stability towards the HDO of p-cresol compared to those prepared by the conventional methods for bulk catalysts (Fig. 9b). The performance of HDO was significantly improved owing to the generation of numerous S vacancies (Fig. 9c). This unique catalyst structure allowed the reaction temperature to be reduced to 180 °C and no S loss was detected during the catalytic process. In summary, the formation of the Co-Mo-S phase notably enhanced the HDO catalytic efficiency of MoS2-based systems.

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic illustration of the preparation routes for Co-Mo-S and CoS2/MoS2 catalytic materials. Reproduced with permission[49]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (b) Kinetic study of p-cresol to toluene at 3 MPa and 300 °C, the order of activity: Co-SMoS2 > SMoS2 > FMoS2 > bulk MoS2. (c) Physical (solvent intercalation) and chemical (Lithium intercalation) exfoliation methods of bulk MoS2, S: yellow, Mo: green. Reproduced with permission[48]. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature.

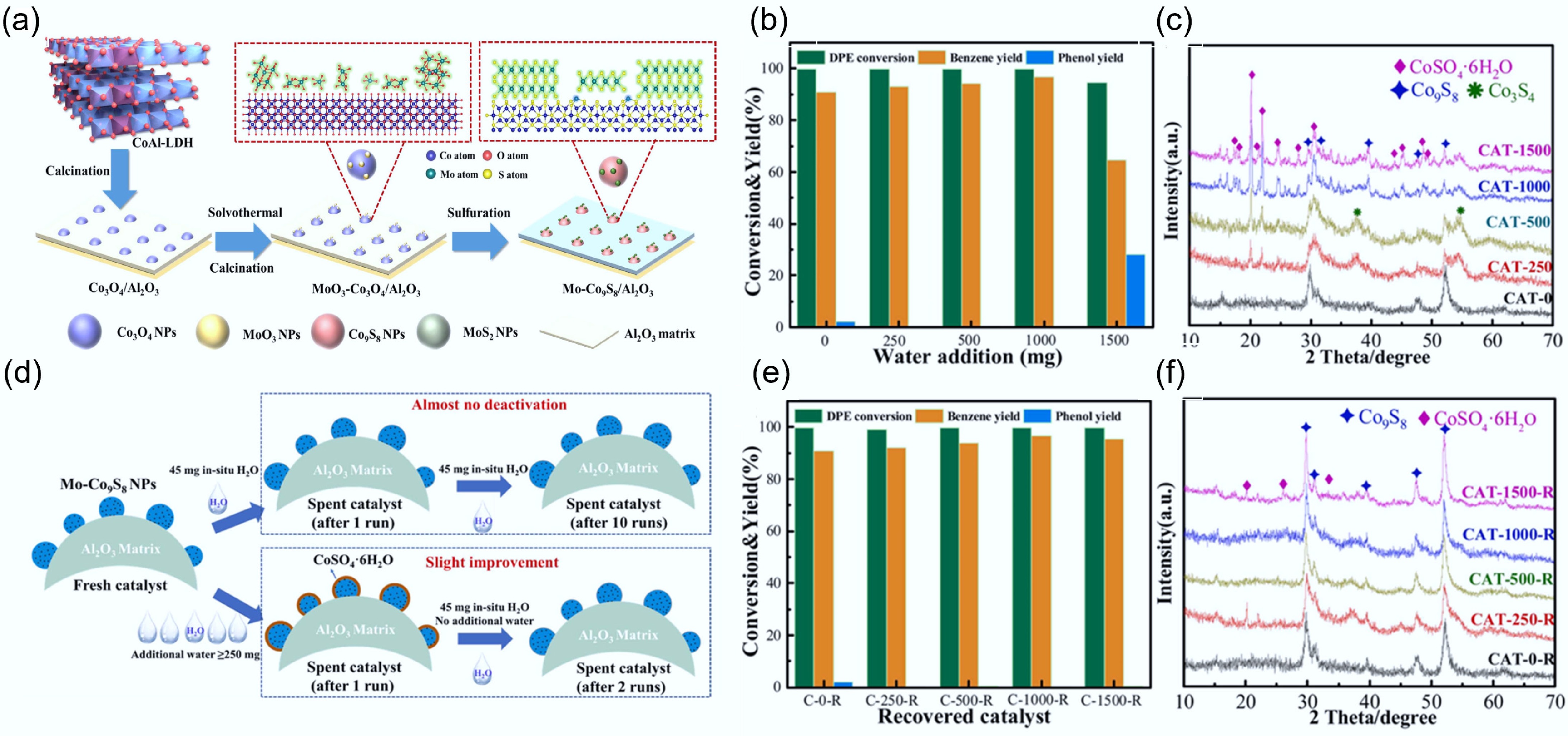

In situ formation of substantial water occurred during the HDO reaction. The produced water interacts readily with the active site of the Co-doped MoS2 catalyst at elevated temperature, leading to the loss of S from the Mo active sites, and consequently causing catalyst deactivation[86,87]. Thus, a synthetic strategy of loading highly dispersed Mo on hydrotalcite-derived Co3O4/Al2O3 and subsequent sulfidation was proposed by Diao et al. to prepare the Mo-Co9S8/Al2O3 catalyst (Fig. 10a)[50]. By enclosing the active Co-Mo interfacial sites in the water-absorbent rich inert Co9S8 species, this indirect protection approach avoided the contact between water and active sites, thus enabling the catalyst to exhibit strong resistance to water deactivation[68]. In this study, complete removal of the oxygen atom from 2.5 mmol of diphenyl ether would theoretically yield 45 mg of water. Under the same conditions, the moderate addition of water increased the yield of aromatics. However, excessive water resulted in a competitive adsorption behavior between water and diphenyl ether, reducing the conversion and yield (Fig. 10b). From the XRD pattern of the recovered catalysts, with the increase of water, the abundant Co9S8 on catalyst surface was preferentially passivated and transformed into cobalt sulfate hydrate (Fig. 10c). Meanwhile, the active interface remained essentially intact, attributed to the protective role of Co9S8 (Fig. 10d). Stability testing of the above recovered catalysts revealed that the catalysts with cobalt sulfate hydrate as the main phase exhibited enhanced benzene yield and fully reverted to the Co9S8 phase at the end of the reaction (Fig. 10e,f). In addition, the anchoring effect of the Al2O3 matrix also made the catalyst resistant to high-temperature sintering. This highly selective and robust catalyst was capable of converting raw lignin into aromatics, even under challenging reaction conditions.

Figure 10.

(a) Schematic synthesis of Mo-Co9S8/Al2O3 catalyst. (b) Effect of water addition on the DPE HDO process over Mo0.06-Co9S8/Al2O3 catalyst. (c) XRD spectrum of Mo0.06-Co9S8/Al2O3 recovered from the (b) reaction. (d) Simplified scheme for catalyst property changes. (e) HDO results of Mo0.06-Co9S8/Al2O3 catalysts recovered from the (b) reaction over DPE. (f) XRD spectrum of Mo0.06-Co9S8/Al2O3 recovered from the (e) reaction. Reaction conditions: 106 mg catalyst, 3 MPa, 265 °C, 10 h. Reproduced with permission[50]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Although sulfide catalysts show high selectivity in HDO, the constant addition of H2S/C2S to regenerate the catalyst is required due to S loss during the reaction. At the same time, the catalysts are subject to contamination and rapid deactivation due to coke deposition. The large amount of water generated during the HDO process seriously affects the performance of the active sites, so the improvement of water resistance is a challenge that needs to be solved urgently. Decreasing the reaction temperature is currently the most stable and cost-effective strategy used to inhibit S loss, water toxicity, sintering, and carbon deposition. Nevertheless, achieving high catalytic activity in MoS2-based systems under low-temperature conditions remain a significant scientific challenge.

Noble metal catalysts

-

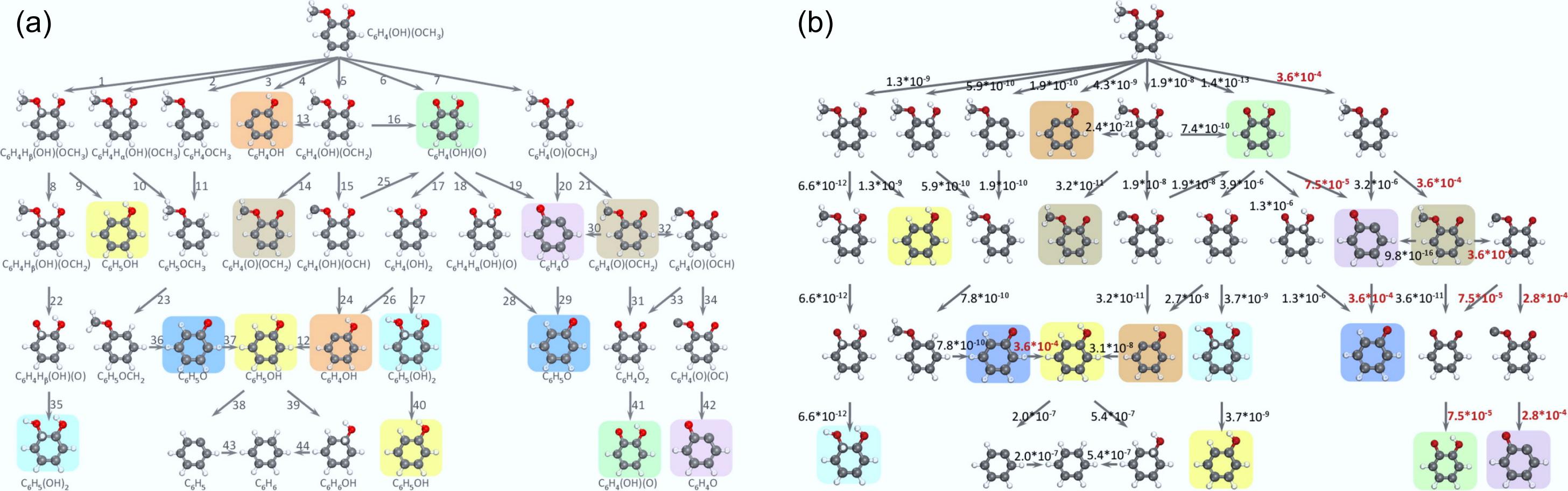

In view of the excellent low-temperature activity and hydrogenation properties of noble metals, especially in the selectivity for cycloalkanes, noble metals have been extensively studied in HDO[88,89]. The reaction network and TOF of the corresponding steps for the hydrogenation of guaiacol on Pt (111) at atmospheric pressure to aromatic products were investigated by theoretical calculation and are shown in Fig. 11[90]. At 573 K, the production of the main product catechol was found to be at least four orders of magnitude faster than its further deoxygenation to phenol or benzene. The slow deoxygenation of guaiacol can be achieved through decarbonylation, hydrogenation of the benzene ring, and cleavage of the -OH bond. In the absence of an activated aromatic ring, the deoxygenation rate is reduced by at least five orders of magnitude.

Figure 11.

(a) Reaction network depicting the hydrogenation of guaiacol on the Pt (111) surface to yield aromatic products. (b) Turnover frequencies (s−1) of elementary steps at the pressure of 1 bar for guaiacol and hydrogen reactants and the temperature of 573 K. Reproduced with permission[90]. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society.

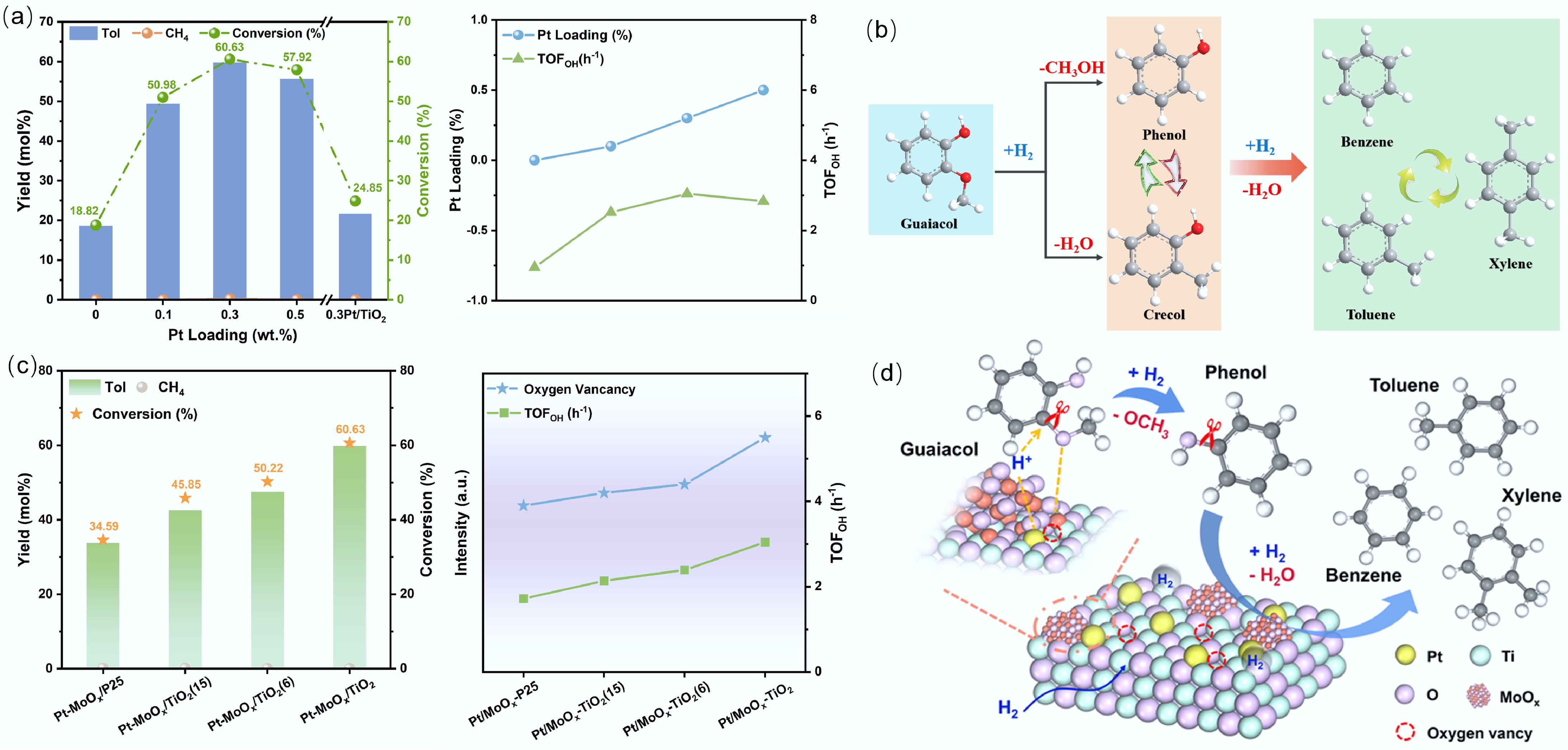

Compared with monometallic catalysts, the incorporation of a second metal can alter the d-band electron density and surface morphology of the primary metal. Due to the synergistic interaction between the two metals, bimetallic catalysts show good activity, selectivity, and stability for C–O bond breaking in HDO[91−97]. It has further been observed that bimetallic catalysts efficiently suppress polymerization, condensation, and carbon deposition throughout the catalytic process[33,52,61,66]. For instance, literature reports indicate that the high activity of Pd-Fe bimetallic catalysts in HDO stems from the interaction between Pd and Fe, which shifts the d-band center of Pd[98,99]. The incorporation of Fe altered the electronic configuration of Pd, resulting in attenuated adsorption of both reaction intermediates and final products. In addition, the presence of Pd prevented the deactivation of the catalyst due to Fe oxidation, thus preserving the formation of metallic Fe in the HDO process. The Pt-Mo bimetallic catalyst exhibits high selectivity for aromatic hydrocarbons in the HDO of lignin derivatives (Fig. 12a). The addition of Pt alters the structure of Mo, enhancing the hydrogen decomposition and the hydrogenation desorption of intermediates. The presence of Pt also promotes the alkylation reaction, retaining more hydrocarbon elements in the liquid product (Fig. 12b). Moreover, the presence of oxygen-rich vacancies in TiO2 enhances the adsorption of oxygen-containing substrates, preventing catalyst deactivation due to the activity of Mo (Fig. 12c, d)[100].

Figure 12.

(a) The hydrogenation dehydrogenation of guaiacol by Pt-Mo bimetallic system. (b) Direct deo-xygenation and alkylation transfer of guaiacol on Pt-Mo surface. (c) The influence of carrier oxygen vacancies on the hydrogenation dehydrogenation rate of Pt-Mo catalysts. (d) The synergistic mechanism of bimetallic and carrier oxygen vacancies. Reproduced with permission[100]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

In recent years, bifunctional metal-acid catalysts have garnered growing research attention and demonstrated remarkable activity in the HDO of lignin for the production of hydrocarbon compounds. It is desirable to design and synthesize bifunctional catalysts integrating the hydrogenation ability of active metals and the deoxygenation properties of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites to promote efficient HDO reactions[101−104]. Usually, the noble metals provide hydrogenation active sites for the HDO reaction, while the carriers or the incorporated second acidic oxides provide acidic sites. Zhao et al.[101] have made a significant contribution to the efficient combination of the active sites. The research team developed a bifunctional catalytic system combining carbon-supported noble metals with phosphoric acid, which achieved selective transformation of phenolic bio-oil constituents into cycloalkanes and methanol through consecutive hydrogenation–hydrolysis–dehydration pathways. The transformation of phenols to cyclohexane in liquid-phase hydrodeoxygenation occurred via a sequential three-step mechanism: (i) metal-catalyzed aromatic ring hydrogenation to cyclohexanol, (ii) acid-promoted cyclohexanol dehydration generating cycloalkene intermediates, and (iii) final metal-catalyzed hydrogenation of the cycloalkene to saturated cyclohexane[101,105].

Duan et al. prepared an efficient Pd/m-MoO3-P2O5/SiO2 catalyst for the HDO of phenol as a model substrate[52]. When compared with the Pd/SiO2 catalyst, which only yielded hydrogenation products (cyclohexanol and cyclohexanone), the new Pd/m-MoO3-P2O5/SiO2 catalyst promoted the subsequent dehydration process. This improvement stems from the introduction of acidic sites (m-MoO3-P2O5), leading to highly dispersed Pd and coexisting Brønsted–Lewis acid sites on the catalyst surface. Under mild reaction conditions, the catalyst exhibited complete phenol conversion (100%) with exceptional cyclohexane selectivity (97.5%), demonstrating superior performance compared to the monofunctional Pd/SiO2 reference system. Yang et al. strategically exploited the synergistic interplay between metallic and acidic sites by developing a bifunctional catalytic system comprising Ru/C and phosphotungstic acid (HPW)[55]. The thermally responsive phase transition characteristics of HPW facilitated its uniform distribution across the Ru/C catalyst surface while enhancing interfacial interactions between metallic and acidic active sites. Ru/C-HPW enabled the efficient conversion of guaiacol to cycloalkane products at a lower temperature (200 °C), which demonstrated the advantages of high reaction rate and good recoverability.

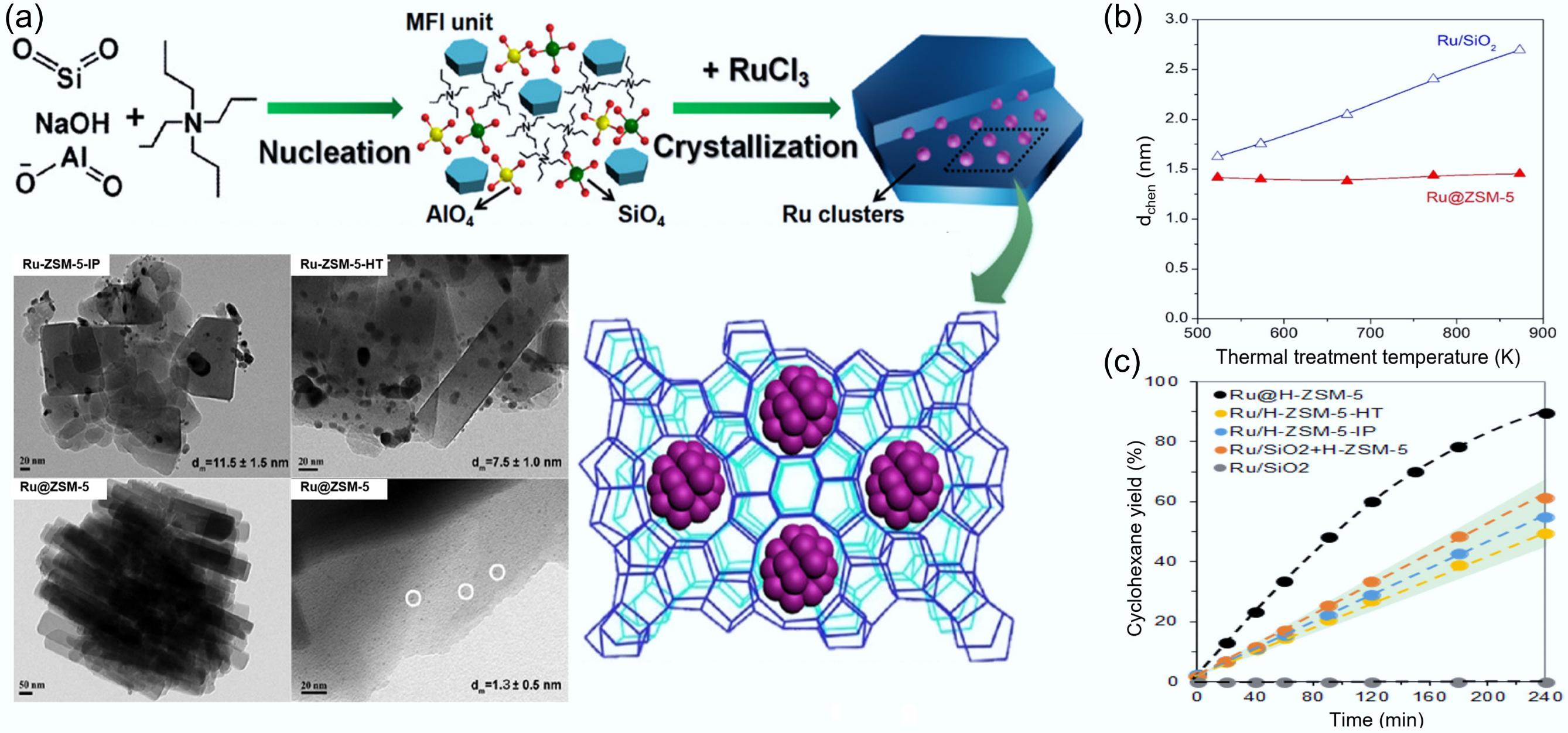

Molecular sieve solid acid catalysts have found wide application in bifunctional catalysts due to the unique selective morphology, strong hydrothermal stability, and tunable acidity[106,107]. The nanoscale intimacy between metallic and acidic centers in metal-molecular sieve catalysts notably enhances metal stability and enables synergistic effects in catalytic reactions. Yang et al. prepared highly dispersed (dispersion ~ 80%) ultrafine metallic Ru clusters (average particle size 1.4 nm) by an in situ two-stage hydrothermal synthesis strategy (Fig. 13a), and successfully encapsulated them into high-alumina ZSM-5[56]. This new method offered significant advantages over the conventional impregnation method (average particle size 11.5 nm) and the one-step hydrothermal method (average particle size 7.5 nm). It significantly improved the metal stability and prevented the sintering or leaching of active metal species during the catalytic process[108]. As shown in Fig. 13b, after thermal treatment at varying temperatures from 573 to 873 K, the average diameter of Ru species in Ru@ZSM-5 did not change significantly, even at high temperatures, and remained at 1.5 nm. This result confirms that the confined environment of molecular sieves improves the thermal stability of metal clusters. The Ru@H-ZSM-5 catalyst exhibited a narrow and distinct Al (IV) signal (99.2%), along with a Brønsted acid site (BAS) fraction of 97% in the molecular sieve pore. The Al (IV) dominated in the tetrahedral framework of aluminum (FAL), and provided tight Ru clusters and BAS neighborhoods at the sub-nanometer level. Unlike the Ru/SiO2 catalyst without acid sites, where the phenol HDO reaction yielded only the primary products cyclohexanone and cyclohexanol, the selectivity and yield of cyclohexane in Ru@H-ZSM-5 were significantly increased (Fig. 13c), improving the ability of deep HDO.

Figure 13.

(a) Schematic preparation and TEM characterization of catalysts for in situ two-stage hydrothermal synthesis of metal clusters encapsulated into high-alumina ZSM-5. (b) Average diameters of Ru particles in Ru/SiO2 and Ru@ZSM-5 by H2 chemisorption across a temperature range spanning from 573 to 873 K. (c) Time-dependent cyclohexane yield profiles for various catalysts. Reproduced with permission[56]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

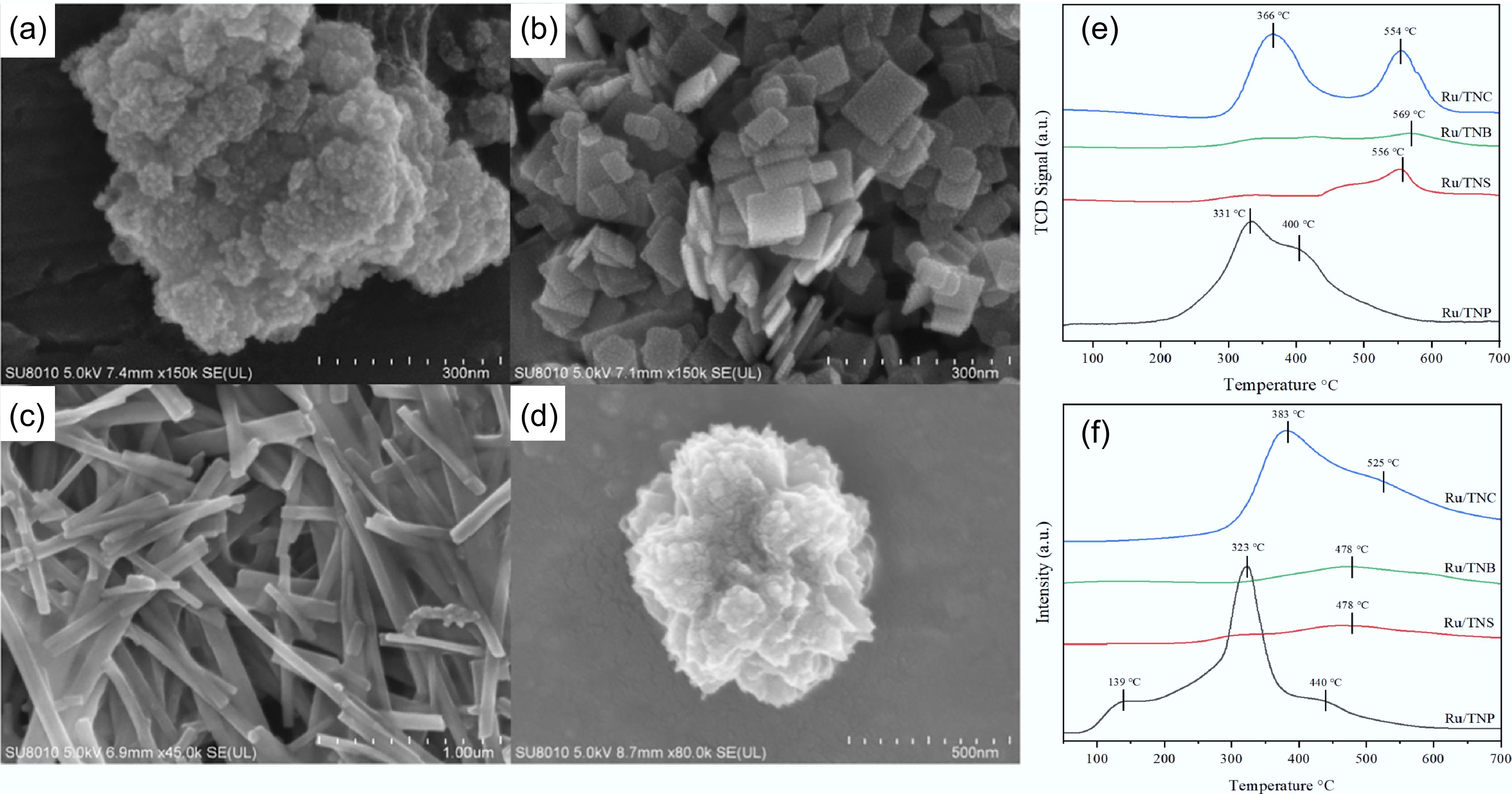

While an increase in acidic sites can facilitate the deoxygenation process, excessively high acidity may lead to the polymerization of phenolic compounds to form coke deposits that adhere to the catalyst surface and result in coking deactivation. For example, in the HDO of guaiacol over CoMo/Al2O3 catalyst studied by Laurent & Delmon, the strong acidity of Al2O3 led to the polymerization of guaiacol[68]. As a typical acidic carrier, TiO2 is moderately acidic and less prone to polymerization, and therefore has potential as a carrier of HDO catalysts[109,110]. Zhong et al. dispersed Ru on four different morphologies of TiO2 by photochemical methods, including nanosphere (TNP), nanosheet (TNS), nanobelt (TNB), and nanocluster (TNC) (Fig. 14a-d). Ru/TNP showed good performance in the HDO of guaiacol at 250 °C and 1 MPa H2, achieving nearly 100% conversion and cyclohexane selectivity. This exceptional activity arises from its large surface area, robust hydrogen adsorption capacity, and abundant medium-strength acid sites (Fig. 14e,f)[54].

Figure 14.

SEM micrographs of: (a) Ru/TNP, (b) Ru/TNS, (c) Ru/TNB, (d) Ru/TNC. (e) H2-TPD, and (f) NH3-TPD patterns for different Ru-based catalysts. Reproduced with permission[54]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier.

To suppress the excessive hydrogenation of aromatic rings to generate cycloalkanes, the selectivity of aromatic hydrocarbons was significantly improved by rational modification of the catalyst structure. Bifunctional catalysts have demonstrated breakthrough progress among numerous catalytic materials in recent years due to their superior performance, becoming a research hotspot for an increasing number of scientists[111,112]. Bifunctional catalysts typically consist of two components: metals and reducible metal oxides. Among them, metals (like Pt, Pd, Ru, etc.) adsorb and activate hydrogen molecules, generating active hydrogen protons that provide additional active sites for hydrogenation reactions, and significantly enhance the reaction rate. It has been confirmed that the interaction between Pt and different metal oxides significantly affects the selectivity of target products, promoting the reaction to proceed toward the formation of specific aromatic products[113]. Reducible metal oxides markedly improve hydroxyl group adsorption capacity via engineered oxygen vacancy formation, thereby enabling efficient direct deoxygenation pathways under thermodynamically challenging low-pressure, high-temperature conditions[53]. At high temperatures, the C–O bond in hydroxyl groups adsorbed on oxygen vacancies gains sufficient energy to break, producing dehydroxylation products. More importantly, the close coupling between metal active sites and reducible metal oxide active sites in the bifunctional catalyst system plays a crucial role in improving the selectivity of aromatic hydrocarbons[114]. Wang et al. explored the synthesis of toluene from m-cresol via HDO reaction over C-loaded Pt-WOx catalysts[59]. DFT calculations of m-cresol adsorption on the optimized Pt (111) surface revealed that platinum not only stabilized tungsten oxide species but also induced the generation of redox-active sites, thereby accelerating C–O bond hydrogenolysis. Thus, in stark contrast to the inferior performance of the Pt/C catalyst, which exhibited lower selectivity and stability in this reaction, the Pt-WOx/C catalyst demonstrated remarkably high activity and toluene selectivity (> 94%). Under reduced hydrogen pressure and in the absence of a solvent, the Pt-WOx/C catalyst still displayed exceptionally high selectivity for the target product. The authors further demonstrated that this highly active catalyst is not limited to cresol derivatives alone. In response to the problem that the aromatic rings are prone to hydrogenation during the hydrodeoxygenation of conventional lignin derivatives, Gao et al. designed a bimetallic highly targeted deoxygenation catalyst rich in oxygen vacancy defects[100]. The Pt-MoOx/TiO2 catalyst supported on TiO2 rich in oxygen vacancies prepared by the hydrothermal method features a large specific surface area, pore volume, small microcrystalline size, higher acidity, and obvious mesoporous characteristics, which effectively improve the hydrodeoxygenation performance of the catalyst. The catalyst exhibits a strong signal peak intensity of oxygen vacancies, which can promote the reduction of Mo species while avoiding excessive reduction of active valence states. Under the optimal catalyst preparation and reaction conditions, the Pt-MoOx/TiO2 catalyst shows significantly better reaction activity than other catalysts, achieving complete conversion of m-cresol and a high aromatic hydrocarbon molar yield of 98.45%.

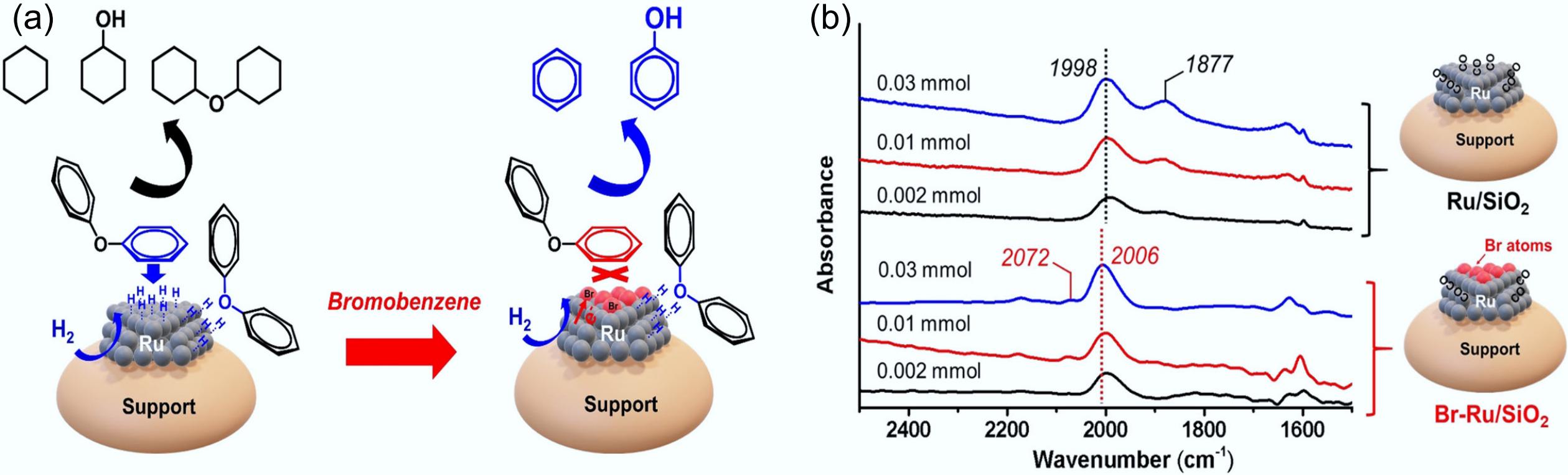

The introduction of heteroatoms can affect the adsorption patterns and conversion pathways of the substrates. In the HDO of diphenyl ether, Ru/C showed excellent hydrogenation performance toward the benzene ring under conditions of 120 °C, 5 bar H2, and with methanol as a hydrogen-donor solvent[115,116]. However, the introduction of the halogenated element Br for the hydrogenolysis pretreatment of Ru/C under reducing conditions led to a dramatic change in the product distribution, with aromatic hydrocarbons (benzene and phenol) as the main products in yields as high as 90.3%, implying that Br almost completely inhibited the hydrogenation of the benzene ring[60]. FTIR spectral analysis of CO adsorption further confirmed that Br atoms were selectively deposited on the terraces of Ru nanoparticles, which effectively prevented the excessive hydrogenation of the aromatic ring (Fig. 15). The hydrogenolysis of C–O bonds primarily occurs at the corner and edge surfaces of Ru nanoparticles, where positively charged Ru species exhibit high deoxygenation activity toward these bonds.

Figure 15.

(a) Schematic illustration of the adsorption and conversion of DPE on Ru and Ru-Br catalysts. (b) CO-FTIR patterns of Ru/SiO2 and Br-Ru/SiO2 catalysts. Reproduced with permission[60]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

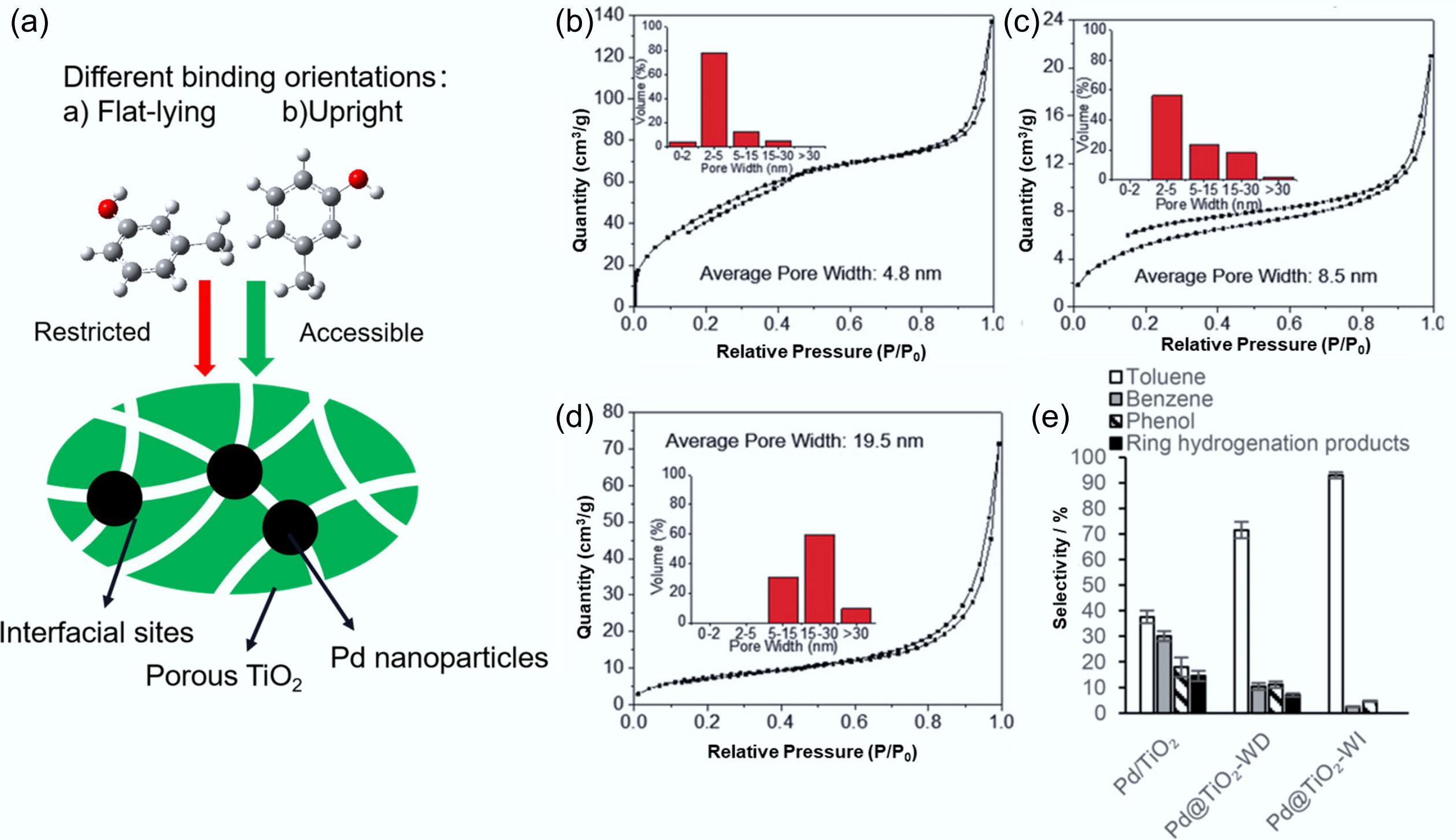

The pore size of the catalyst also affects the aromatic selectivity. Zhang et al. demonstrated that coating well-dispersed Pd nanoparticles with porous TiO2 films significantly improved the HDO selectivity toward the aromatic phenolic compound m-cresol (Fig. 16a, e)[117]. The porosity of TiO2 films was modulated by adjusting the rate of water injection to regulate the hydrolysis rate of the precursor or by switching to acetone to reduce the activity of the precursor[118]. Pd@TiO2-WI had the smallest average pore size (4.8 nm), with most (~ 82%) of them having pore widths less than 5 nm, whereas ~ 50% of Pd@TiO2-WD with an average pore size of 8.5 nm had pore widths larger than 5 nm, and Pd@TiO2-AI had the largest average pore size of 19.5 nm (Fig. 16b−d). They found that encapsulating Pd in TiO2 films with a minimal pore size could suppress side reactions, accelerate the HDO reaction rate, as well as inhibit the decarboxylation and cyclic hydrogenation.

Figure 16.

(a) The nanoporous TiO2 film precisely modulates binding characteristics and creates engineered interfacial active sites. N2 physisorption isotherm plots and pore size distributions of TiO2 in (b) Pd@TiO2-WI, (c) Pd@TiO2-WD, (d) Pd@TiO2-AI. (e) Catalytic conversion selectivity of HDO on m-cresol. Reproduced with permission[117]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

Non-noble metal catalysts

-

Recent studies on HDO catalysts have also centered on the development of low-cost transition metal catalysts[119,120]. Coking remains one of the most critical issues in HDO, directly impeding the industrial application of bio-oil. While elevated temperatures promote faster reaction kinetics, they concomitantly increase carbon deposition rates. Structurally optimized transition metals (Ni, Co, Mo) have shown significant effectiveness in mitigating carbon deposition during catalytic processes.

In particular, metal Ni has a strong ability to adsorb and activate H2, and is widely used in the HDO of bio-oil model compounds. Studies have revealed that metal oxide supports notably enhance the deoxygenation activity of Ni-based catalysts. Mortensen et al. demonstrated that Ni/ZrO2 showed the best phenol HDO performance in a range of catalysts (Ni/Al2O3, Ni/SiO2, Ni/CeO2-ZrO2, Ni/CeO2, Ni/C, Ru/C, and Pd/C). The interaction between the oxygen-friendly sites Zr3+/4+ and the –OH bond on the ZrO2 carrier was beneficial for the activation of phenol, thus facilitating the HDO reaction[121]. Previous studies have indicated that in a bimetallic catalyst, the active metal site facilitates H2 dissociation, whereas the modified metal provides anchoring sites for the oxide[93, 122,123]. Chen et al.[62] designed and developed an inexpensive FeNi-ZrO2 catalyst via a co-crystallization method for the production of cyclohexane from guaiacol. By adding the oxygen-friendly metal Fe, the catalytic activity for HDO was significantly improved, achieving a hydrocarbon product selectivity of 98.5% at complete guaiacol conversion. Compared with the traditional impregnation method, the co-crystallization method resulted in a stronger binding of the metal species to the amorphous zirconium dioxide and promoted metal dispersion.

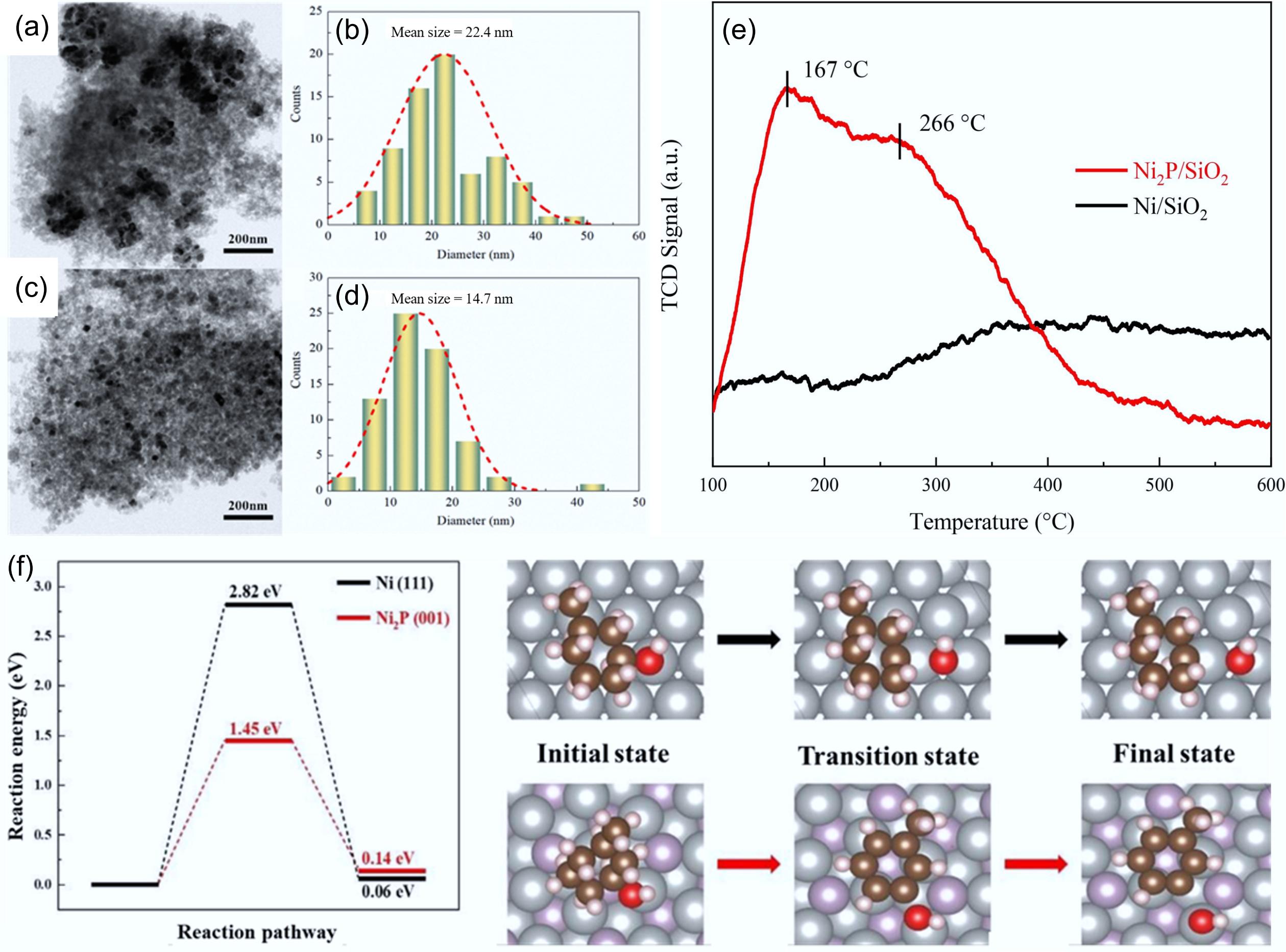

The cooperative interaction between acidic and active catalytic sites was observed to facilitate selective C–O bond scission, leading to cycloalkane formation[6, 124,125]. The incorporation of phosphorus species induced both electronic modulation and geometric restructuring of the Ni2P phase, facilitating robust interactions between phosphorus sites and hydroxyl groups. Highly dispersed and smaller (14.7 nm) Ni2P particles were formed, which also exposed more active sites on the catalyst surface (Fig. 17a–d). In addition, it significantly increased the acidic sites (Fig. 17e) and facilitated the dehydration of cyclohexanol to produce cyclohexane[63, 126]. The Ni2P/SiO2 catalyst exhibited high methylcyclohexane selectivity (96.3%) at 250 °C for 4 h. The Ni2P (001) surface facilitates C–OH bond cleavage with a 1.45 eV energy barrier. This result has been confirmed by DFT, demonstrating superior activity over conventional Ni (111) (2.82 eV) (Fig. 17f)[64].

Figure 17.

(a) TEM images of Ni/SiO2, and (c) Ni2P/SiO2 and respective (b), (d) particle size distributions. (e) NH3-TPD profiles of Ni/SiO2 and Ni2P/SiO2 catalysts. (f) C–OH bond cleavage energy barriers for MCHnol on the Ni (111) and Ni2P (001) surfaces. Ni: gray, P: purple, C: brown, H: pink, O: red. Reproduced with permission[64]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier.

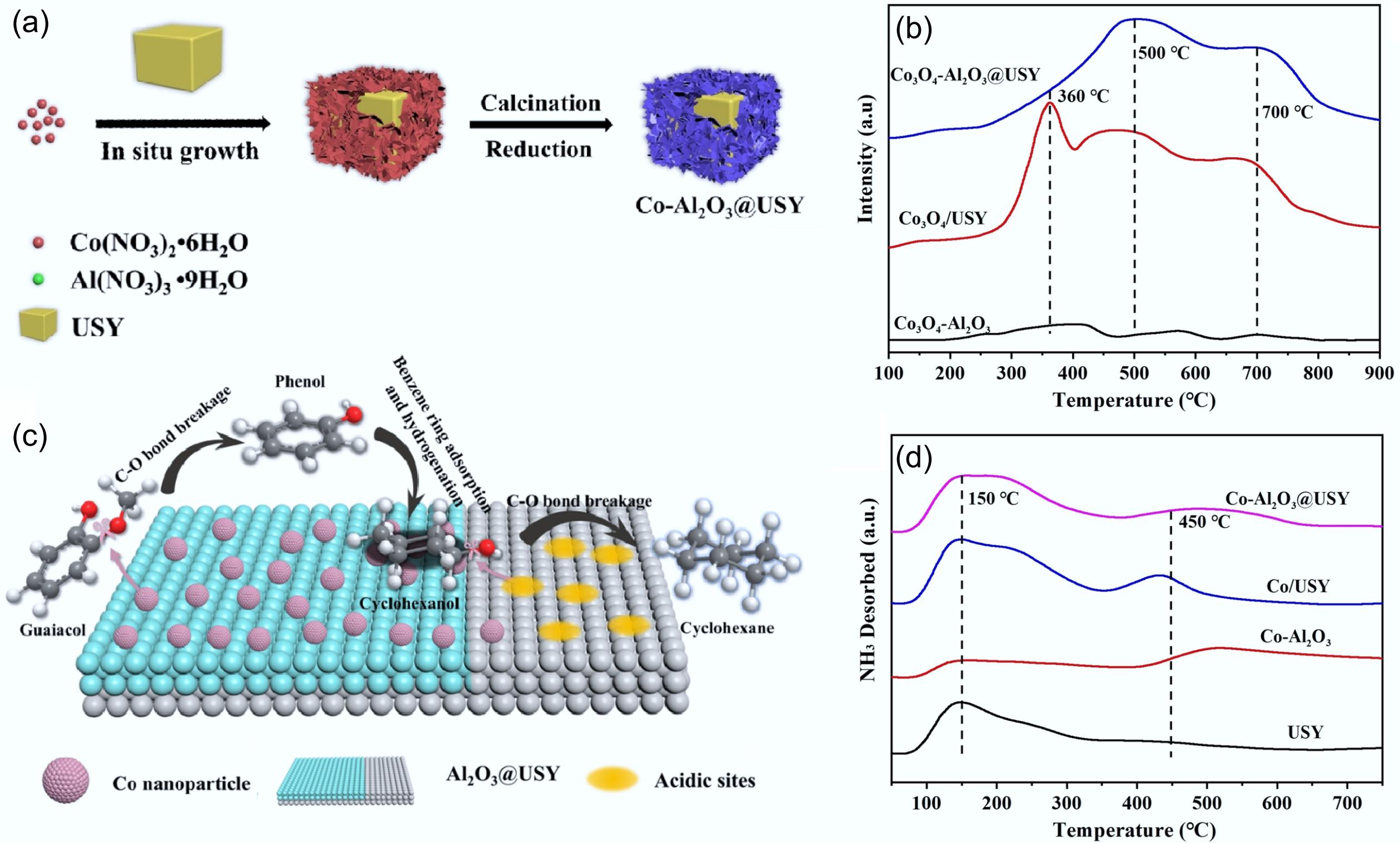

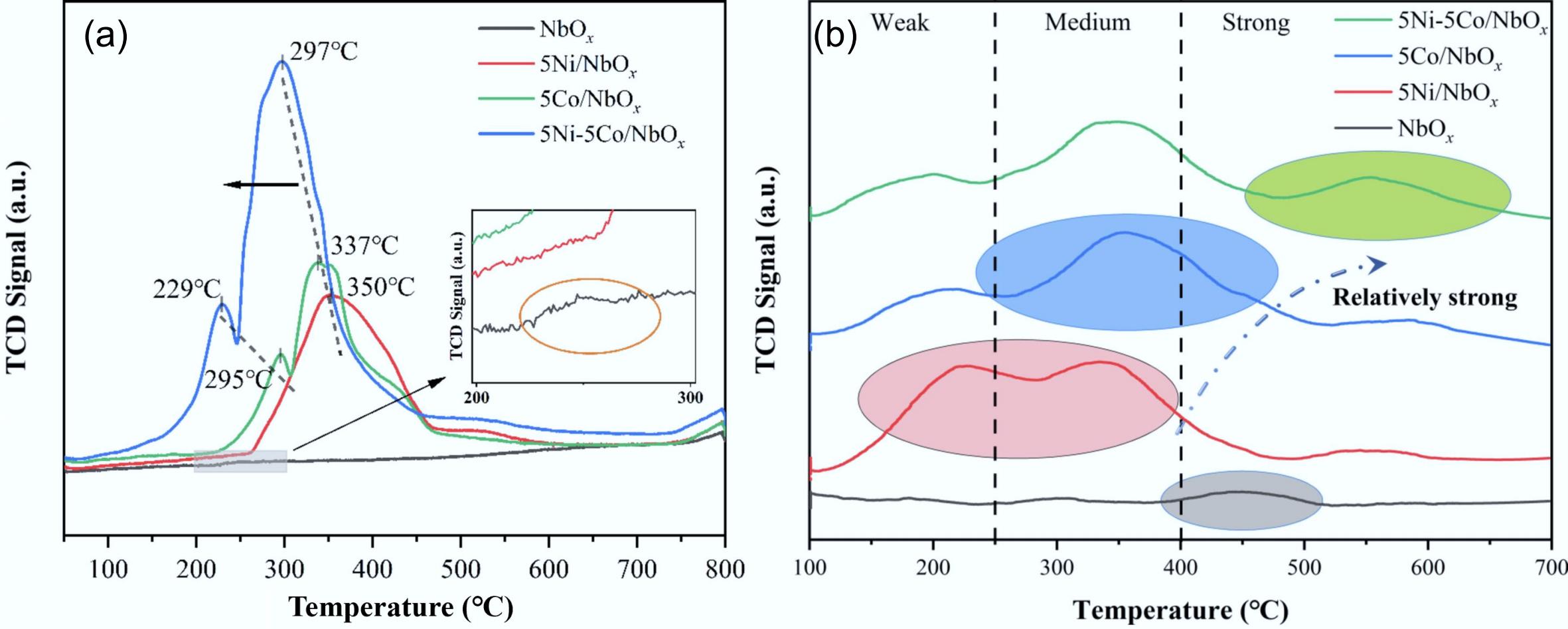

Co-based catalysts also showed good activity for lignin-derived phenol hydrogenation. However, due to the weaker deoxygenation ability of Co compared to Ni, it usually requires a combination of metal doping or metal-carrier synergistic means to promote –OH breakage[128−130]. Ji et al. prepared Co-Al2O3@USY bifunctional catalyst via treatment of CoAl layer double hydroxide (LDH) grown in situ on USY molecular sieve in a reducing atmosphere (Fig. 18a)[127]. The catalytic performance was investigated in the HDO process of guaiacol under conditions of 180 °C, 3 MPa, and 4 h, achieving complete conversion with a high cyclohexane yield of 93.6%. The reduction properties of oxide precursors were further analyzed in conjunction with H2-TPR (Fig. 18b), and it was found that a strong interaction between Co and the molecular sieve carrier was formed. Meanwhile, the topological transformation of the LDH structure produced small Co nanoparticles (average particle size of 10.6 nm) that were highly dispersed on the surface of the catalyst (Fig. 18c)[131−133]. Simultaneously, the unique properties of molecular sieves endowed the catalyst surface with abundant acidic sites (Fig. 18d), and the synergistic effect with the metal active sites improved the deoxygenation capacity. In addition, the anchoring effect of Al2O3 matrix on Co nanoparticles well suppressed the agglomeration of Co particles; therefore, the catalyst exhibited excellent stability. Zhang et al. also synthesized a bifunctional catalyst by combining a Ni-Co alloy with an oxygen-friendly carrier NbOx, which showed high catalytic activity when Ni: Co = 1 (molar ratio). Notably, from the H2-TPD profiles (Fig. 19a), it was found that the reduction peak areas of the bimetallic 5Ni-5Co/NbOx catalyst were significantly larger than those of the monometallic ones, which was attributed to the fact that high metal loading of bimetallic catalysts leads to an increase in the consumption of H2. The notable peak shift toward the low-temperature region indicated that the Ni-Co alloy facilitated the reduction of oxide precursors. The oxygen vacancies in NbOx not only enhanced the adsorption of phenolics but also contributed to the formation of unique acidic sites (Fig. 19b), which promoted the HYD pathway and formed a strong interaction with the active metal to achieve the complete conversion of guaiacol, with up to 98.9% selectivity for cycloalkanes at 300 °C, 3 MPa H2[61].

Figure 18.

(a) Schematic synthesis of Co-Al2O3@USY catalyst. (b) H2-TPR profiles of Co3O4-Al2O3, Co3O4/USY, and Co3O4-Al2O3@USY. (c) Postulated reaction pathways for guaiacol hydrodeoxygenation catalyzed by the Co-Al2O3@USY catalyst. (d) NH3-TPD profiles of USY, Co-Al2O3, Co/USY, and Co-Al2O3@USY. Reproduced with permission[127]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

Figure 19.

(a) H2-TPR, and (b) NH3-TPD profiles of NbOx, 5Ni/NbOx, 5Co/NbOx, and 5Ni-5Co/NbOx catalysts. Reproduced with permission[61]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Unlike Co selectively breaks C–C bonds, one of the cheapest and abundant transition metals Fe exhibits high deoxygenation rates at low H2 consumption and has superior selectivity toward aromatic production from phenolics[134]. Sun et al. prepared a Fe-modified ZSM-5 catalyst, which prefers C–O bond breaking as Fe is an oxygen-friendly metal, and the yield of aromatics was greatly improved[135]. The presence of Fe also led to the catalyst surface susceptible to oxidation or deactivation due to carbon deposition[110, 136−139].

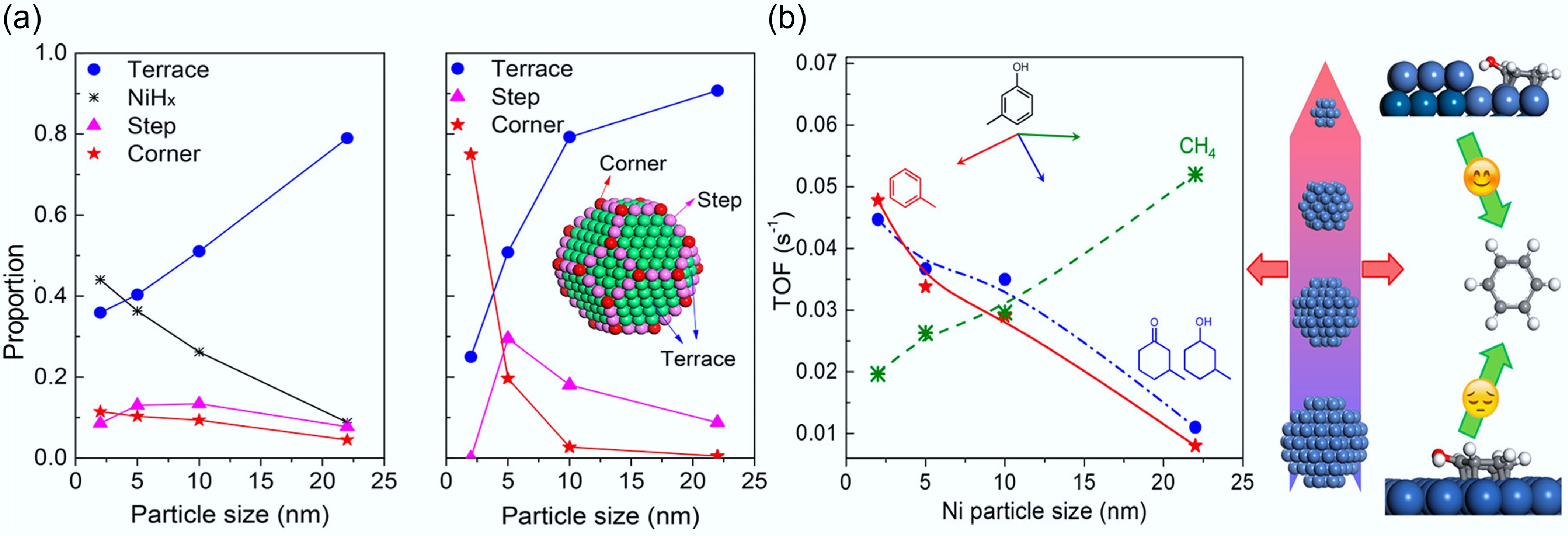

Existing studies have shown that tailoring the active metal particle size significantly affects both the catalytic activity and aromatic hydrocarbon selectivity in phenolic HDO. Ni-based catalysts typically exhibit benzene ring hydrogenation at low temperatures. Unfortunately, they are prone to break C–C bonds at high temperatures to generate large amounts of the byproduct methane, resulting in a decrease in the calorific value due to the undesired carbon loss[64]. Therefore, it is important to improve HDO activity by modifying Ni-based catalysts. The correlation between Ni nanoparticle sizes (2–22 nm) supported on SiO2 and their deoxygenation activity was systematically investigated through m-cresol hydrodeoxygenation experiments conducted at 300 °C under 1 atmosphere H2 pressure[66]. The surface site distribution (terrace/step/corner) exhibits strong particle-size dependence, with relative abundances varying by up to 70% across the 2-22 nm range. As the Ni particle size increases, the proportion of terrace sites increases while that of corner sites decreases (Fig. 20a). A size reduction of Ni particles from 22 nm to 2 nm resulted in a 6-fold increase in toluene-selective deoxygenation TOF, concomitant with a 75% reduction in methane formation activity. Nevertheless, CH4 selectivity remained at 10% (Fig. 20b). These findings demonstrate that reduced particle dimensions promote deoxygenation/hydrogenation pathways, while extended terrace sites preferentially facilitate C–C bond hydrogenolysis. Reducing the Ni particle size represents an effective strategy to suppress C–C hydrogenolysis. The propensity for C–C bond hydrogenolysis can be effectively suppressed through strategic incorporation of a secondary metal to create bimetallic catalytic systems. Yang et al. designed a Ni-Mo alloy catalyst with equal molar ratio loaded on SiO2[67]. Comparative evaluation under standardized conditions revealed that the NiMo bimetallic system achieved m-cresol conversion rates that were 10 to 20 times greater than its monometallic counterparts. Besides, it also showed high deoxygenation activity for toluene, and there was essentially no C–C hydrogenolysis reaction to CH4 even at a high temperature of 350 °C. Overall, during HDO over a specific active metal catalyst, the metal particle size plays a decisive role in governing product distribution. Meanwhile, a higher proportion of step or corner sites on the metal surface is more conducive to the cleavage of the C–O bond.

Figure 20.

(a) Turnover frequency (s−1) for conversion of m-cresol to different products. Reaction conditions: 573 K, 0.1 MPa H2, 30 min, W/F was adjusted to achieve conversion < 10%. (b) Percentage of different surface sites based on H2-TPD patterns and theoretical percentage of the cube-octahedron model based on the size of Ni. Reproduced with permission[66]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

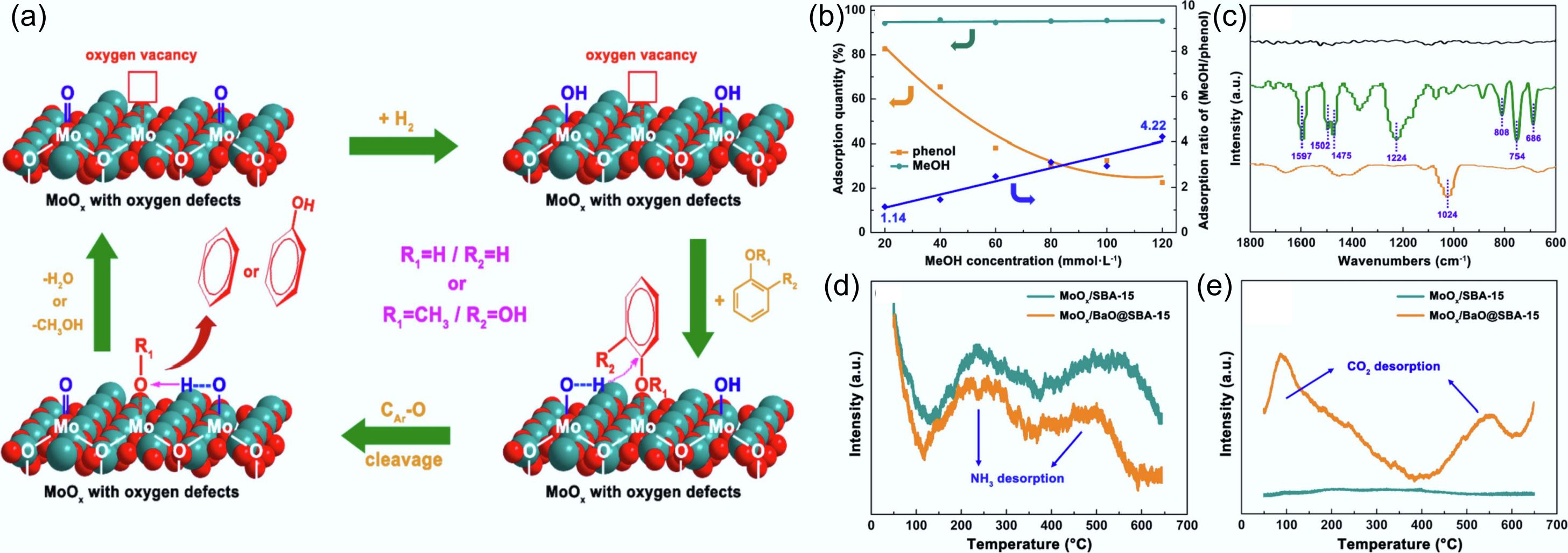

In the hydrodeoxygenation process of guaiacol, the CAr–OCH3 bond cleavage is kinetically favored over CAr–OH scission due to its significantly lower activation energy barrier. Since –OCH3 of intermediate methanol and –OCH3 of guaiacol have similar effects, they equally occupied the active sites on the catalyst surface. This strong interaction significantly weakened the adsorption of -OH groups, leading to competitive adsorption between methanol and phenol. This inhibits the further hydrogen deoxygenation (HDO) reaction of phenol to form benzene. Molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) has been demonstrated to exhibit catalytic behavior analogous to that of molybdenum sulfide. To precisely tune catalyst acid-base properties, Tan's group engineered a MoOx/BaO@SBA-15 system by depositing BaO onto oxygen-deficient MoOx/SBA-15[140−142]. Oxygen-containing groups selectively bind to oxygen vacancies on the catalyst surface, where phenolics undergo selective adsorption in a 'non-planar' configuration, thereby inhibiting excessive hydrogenation of the aromatic ring (Fig. 21a). Upon full activation in H2 for 2 h, the crystalline phase of molybdenum oxide was completely transformed from the pristine MoO3 and transition Mo4O11 phases to MoO2 in the reduced state[143]. The synergistic combination of highly dispersed MoOx species and the high-surface-area, large-pore SBA-15 support substantially increased the population of accessible active sites in the catalytic system. The competitive adsorption behavior between methanol and phenol was explored in solutions with different methanol concentrations, and the adsorption of methanol was consistently stabilized at 95% and above (Fig. 21b), which confirmed that the catalyst was more preferentially adsorbed over phenol for methanol. Simultaneously, FT-IR spectra also yielded consistent findings (Fig. 21c). In the samples treated with both phenol and methanol, the characteristic signal peaks of adsorbed phenol completely disappeared. The catalyst had a stronger interaction with methanol and then inhibited the HDO reaction. The BaO coating enhanced the alkalinity of the catalyst surface (Fig. 21d,e), which promoted the adsorption of phenol. The intermediate product methanol can be eliminated by alkylation reaction with phenol, which further enhances the one-step generation of aromatic products from guaiacol.

Figure 21.

(a) Postulated reaction mechanisms for phenolic compound hydrodeoxygenation catalyzed by activated MoOx/SBA-15 and MoOx/BaO@SBA-15. (b) Adsorption of phenol and methanol on activated MoOx/SBA-15 under varying methanol concentrations. (c) FT-IR spectra of activated MoO3 (black), activated MoO3 treated with phenol dissolved in 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene (green), and activated MoO3 treated with phenol dissolved in methanol (yellow). (d) NH3-TPD, and (e) CO2-TPD of MoOx/SBA-15 and MoOx/BaO@SBA-15. Reproduced with permission[140]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Among the numerous factors leading to catalyst deactivation, sintering of active components is considered as one of the most dominant causes[144]. Recent advances in catalyst design have increasingly targeted core-shell architectures to simultaneously address sintering resistance and active phase stabilization, while providing exceptional coking mitigation capabilities[145,146]. The core retains acidic sites to drive aromatization reactions, while the mesoporous shell layer optimizes the mass transfer pathways and improves the diffusion efficiency of reaction substrates[147,148]. Owing to its unique chemical inertness, mesoporous silica is recognized as an optimal inorganic material for encapsulating active components. This feature ensures that core components exhibit their intrinsic catalytic performance, while the shell layer effectively suppresses sintering and loss of active components[149,150]. Owing to the unique spatial constraints imposed by the core-shell architecture, lignin pyrolysis gas first contacts the shell layer upon passing through the catalyst. The large pore size of the shell layer then cleaves macromolecular oxygenates into small-molecule intermediates. These intermediates then diffuse to the internal core region for deep targeted deoxygenation[151]. Wang's research group engineered a high-performance core-shell Ni@Alx-mSiO2 bifunctional catalyst through precise encapsulation of Ni nanoparticles within aluminum-incorporated mesostructured silica[152]. The appropriate mesoporous pore size significantly promotes the transport of substrates and products while exposing more acidic sites to enhance their accessibility. The core-shell structure strengthens the metal-support interaction, effectively inhibiting the agglomeration of Ni nanoparticles and promoting the generation of more active sites. These characteristics endow the catalyst with excellent stability and good reusability[153,154]. Through templated synthesis, Xue and colleagues fabricated a dual-metal-loaded core-shell catalytic system specifically designed for efficient enzymatic lignin pyrolysis[155]. The research revealed that the metal type and loading position in the core-shell structure significantly influence product distribution. Loading iron on the microporous core and magnesium on the mesoporous shell provides acidic and basic sites, respectively, forming a unique acid-base synergistic catalytic system. The design of the FeZ@MgM core-shell catalyst significantly improves deoxygenation efficiency, achieving a selectivity of 38.9% for monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (MAHs).

-

Hydrodeoxygenation can convert complex, unstable lignin derivatives into platform chemicals or fuels. The hydrodeoxygenation process faces multiple challenges, including demanding operational parameters (elevated temperatures and pressures), substantial hydrogen requirements, solvent usage and separation, excessive hydrogenation, and catalyst deactivation. To solve these key problems, researchers have developed a series of catalysts and uncovered the hydrogenation-deoxygenation (HDO) reaction mechanisms operative at distinct catalytically active sites. This comprehensive review systematically examines recent advancements in the heterogeneous catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived compounds, encompassing sulfide-based, noble metal (e.g., Pt, Pd, Ru, etc.), and non-noble metal (e.g., Ni, Co, Mo, etc.) catalyst systems. For metal sulfides, continuous addition of H2S/C2S is required due to the loss of S species during the reaction process. Furthermore, the catalysts are prone to deactivation due to carbon deposition (coking) or contamination. While noble metal catalysts exhibit efficient low-temperature deoxygenation activity, their propensity for particle agglomeration and rapid deactivation necessitates the incorporation of secondary metals for stabilization. The substantial economic costs and finite natural abundance of noble metals fundamentally limit their viability for industrial-scale deployment and commercial applications. Non-noble metal catalysts generally display inferior activity for the hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived phenolic compounds, their active phases being susceptible to oxidative degradation under low temperatures. In contrast to noble metals, these catalysts are prone to compromised stability, while promoting undesirable side reactions, including condensation and arene ring scission. Bimetallic and metal-acid bifunctional catalysts are currently the most studied catalysts for HDO reactions. Incorporating a second metal with distinct hydrotreating or oxygenophilic properties to fabricate bimetallic or intermetallic catalysts can modify the active sites of the primary metal while simultaneously generating extra active sites. The following aspects should be further explored in the future:

(1) The development of more economical, recyclable, and highly stable catalysts is essential for scaling up lignin hydrodeoxygenation processes. Enhancing HDO efficiency under mild conditions can significantly reduce energy consumption, thereby improving process economics. While noble metals can significantly increase HDO activity at low temperatures with superior resistance to deactivation, they are expensive. Consequently, a key challenge lies in improving noble metal utilization efficiency or developing cost-effective catalysts with noble metal-like performance. Phosphide catalysts have shown similar catalytic properties to noble metals and are promising for broad application in HDO reactions in the future. Acidic sites can promote the deoxygenation process, but highly acidic catalysts also accelerate the rate of coke production. Suitable mesoporous carriers also have a significant impact on catalytic performance. Large pore sizes lead to coking and deactivation, while smaller pore sizes reduce the reaction rate. Therefore, it is necessary to precisely regulate the multiple active sites of the lignin HDO catalyst to construct a highly active and stable catalyst.

(2) Exploring a more environmentally friendly strategy for hydrogen production or choosing the right solvent for the hydrogen donor would greatly improve the carbon mitigation benefits of hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) processes. Currently, the majority of industrial hydrogen is produced from fossil feedstocks, resulting in significant carbon emissions during hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) processes. Thus, there is a need to explore a more environmentally benign and viable strategy for hydrogen production or to select a suitable hydrogen donor, such as isopropanol, methanol, and other alcoholic solvents. In addition, most of the HDO reactions need to be carried out under high H2 pressure conditions. The pursuit of atmospheric-pressure reaction conditions warrant thorough investigation, as successful implementation would simultaneously achieve significant cost reduction and enhanced operational safety.

(3) The choice of lignocellulosic biomass or lignin as a reactant is essential. Currently, a number of experiments were performed using of lignin-derived model compounds. However, real lignin and biomass compositions are very complex, leading to issues such as inadequate contact between the raw materials and the catalyst, as well as a tendency for intermediate products to undergo secondary polymerization. An efficient catalyst should be designed and developed for simultaneous application in both lignin depolymerization and subsequent hydrodeoxygenation processes to achieve the conversion of biomass to hydrocarbon target products through one-step catalysis.

(4) Actual industrial production and large-scale applications require the use of continuous reactor systems. Currently, hydrogen deoxygenation reactions at the laboratory scale are achieved through small high-pressure reactors or easily operated batch reactors. However, in large-scale bio-oil production processes, it is necessary to design reactors for continuous operation, which will facilitate higher yields of the target product. Clearly, this is challenging and requires addressing issues of heat transfer and mass transfer as well as integration with other processes.

The authors acknowledge the financial support of National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFB4206205), the National Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (52425607), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20240010).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study design: Gao Y, Xiao R, Yu J; draft manuscript preparation: Gao Y, Xiao R; data collection: Zhang H; manuscript revision: Zhang H, Yu J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript

-

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper. Additional data related to this paper are available from the authors on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Reviewed the recent advances in heterogeneous catalysts for hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) of lignin derivatives.

Summarized the possible reaction pathways for the hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) of lignin-derived compounds.

Discussed the relationship between catalyst structure and the hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) catalytic pathway as well as performance.

Offers guidance for the design of high-performance catalysts capable of targeted bond cleavage and selective product formation.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yu J, Gao Y, Zhang H, Xiao R. 2025. Hydrodeoxygenation of lignin derivatives on heterogeneous catalysts. Energy & Environment Nexus 1: e002 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0008

Hydrodeoxygenation of lignin derivatives on heterogeneous catalysts

- Received: 19 June 2025

- Revised: 11 August 2025

- Accepted: 22 August 2025

- Published online: 11 September 2025

Abstract: As the only abundant renewable resource containing aromatic ring structures, lignin shows tremendous potential for the production of biofuels and high-value-added chemicals. Catalytic hydrodeoxygenation (HDO) serves as a crucially important approach to convert lignin and its derived complex mixtures into valuable fuels and chemicals. However, lignin-derived compounds contain substantial amounts of oxygen-containing unstable compounds. Under high-temperature conditions, the catalysts are prone to coking and rapid deactivation. Therefore, the design of catalysts with high stable activity at low temperature and low pressure is the core of the HDO process. In recent years, numerous strategies have focused on the design of heterogeneous catalysts to enhance the reaction performance for the production of various high value-added products. This review first summarizes the possible reaction pathways for HDO of lignin-derived compounds over catalysts. Then the relationship between catalyst structure and HDO catalytic performance of reported catalysts (metal sulfides, nobel metal catalysts, non-noble catalysts) are discussed. Finally, this review presents a prospect that contributes to an in-depth understanding of the reported HDO catalysts, and provides guidance for the future design and fabrication of high-performance catalysts that can achieve precise cleavage of the target chemical bonds and selective generation of the target products.