-

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas capable of absorbing long-wave radiation and driving the greenhouse effect[1]. On a mass basis, CH4 shows a significantly higher global warming potential (GWP) than CO2, approximately 28 times higher over a 100-year horizon[2]. Methane originates from both geochemical and biochemical processes, and biogenic methane is predominantly generated by methanogens[3]. The establishment of anaerobic conditions is a critical factor enabling biogenic methane production, as observed in environments such as anaerobic wastewater treatment[4], solid waste digestion[5], flooded rice paddies[6], and anoxic zones of river and lake ecosystems[7]. Globally, methane emissions are estimated at 500–600 Tg/year, with roughly 70% originating from biogenic sources, whereby aerobic methanotrophs play a critical role in the atmospheric source-sink balance by oxidizing approximately 60% of this biogenic fraction[8].

Aerobic methanotrophs (methane-oxidizing bacteria, MOB) represent a group of microorganisms that utilize methane as their carbon and energy source. They are widely distributed in natural environments and can be found in mineral springs[9], lakes[10], wetlands[11], forests[12], and grasslands[13], where they frequently thrive through syntrophic associations with other microorganisms[14]. Since their initial discovery in 1906, advances in molecular phylogenetics and high-throughput omics have progressively refined the taxonomic framework of methanotrophs and deepened the understanding of their global biogeography, metabolic versatility, and ecological significance[15]. Beyond their ecological roles, methanotrophs possess unique biocatalytic machinery that oxidizes methane under ambient conditions. This process mitigates atmospheric emissions while concurrently generating a spectrum of value-added bioproducts, serving a dual functionality that underpins their emerging relevance in industrial and biotechnological applications[16]. Furthermore, the methane monooxygenase (MMO) expressed by methanotrophs exhibits relatively broad substrate promiscuity, which enables the co-metabolic degradation of a wide array of emerging contaminants[17,18], including alkylmercury[19], halogenated hydrocarbons[20], microplastics[21], and certain antibiotics[22]. This trait not only highlights their potential in bioremediation but also implies an adaptive advantage that sustains metabolic robustness under the stress of emerging contaminants.

Methanotrophs exhibit significant advantages in methane removal and resource utilization. Current chemical conversion strategies, such as thermal, photocatalytic, and electrocatalytic processes, aim to transform CH4 into chemicals like methanol and formaldehyde[23,24]. However, the high C-H bond energy and chemical inertness of CH4 necessitate severe reaction conditions, which often result in considerable CO2 emissions and exacerbate greenhouse gas effects[25]. Although carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies offer an effective means of carbon sequestration, their widespread implementation remains constrained by high costs of operation and maintenance[26]. In contrast, methanotroph-based biological systems operate under mild conditions with low energy input, offering a viable and sustainable alternative for efficient methane removal and conversion. Consequently, the valorization of methane through biological pathways has attracted growing research interest. Nevertheless, the metabolic network of methanotrophs is highly complex, and their interactions with other microorganisms, as well as their responsiveness to environmental factors such as nitrogen sources, are not yet fully elucidated. These knowledge gaps currently hinder the engineered application of methanotrophs at scale.

This review systematically summarizes research advances in methanotrophs over the past decade, emphasizing that overcoming bottlenecks in reaction efficiency, product selectivity, and process stability through multi-level metabolic engineering strategies is crucial for transitioning these systems from laboratory-scale studies to industrial applications. We elucidate how the diversity of methanotrophic metabolic pathways underpins their functional versatility, evaluate and summarize their potential for greenhouse gas mitigation and synthesis of high-value products, and discuss the key regulatory mechanisms of carbon flux, along with analytical approaches and underlying principles for improving microbial product yields. Finally, the future development direction for integrating high-value resource utilization technology of methanotrophs with cutting-edge interdisciplinary fields is prospected.

-

Methanotrophic microorganisms are broadly categorized into two functional groups: aerobic methanotrophs and anaerobic methanotrophs. The latter group includes NC10 bacteria[27] and anaerobic methanotrophic archaea (ANME)[28], which utilize substances such as nitrate and nitrite as electron acceptors[11] and are generally unable to grow in oxygen-rich environments. In contrast, aerobic methanotrophs employ O2 as their terminal electron acceptor, exhibit considerable phylogenetic and metabolic diversity, and demonstrate remarkable functional versatility with some strains retaining activity even under hypoxic conditions[10]. Owing to these traits, aerobic methanotrophs play a significant role in both ecological remediation and contribute substantially to the biogeochemical regulation of carbon flux.

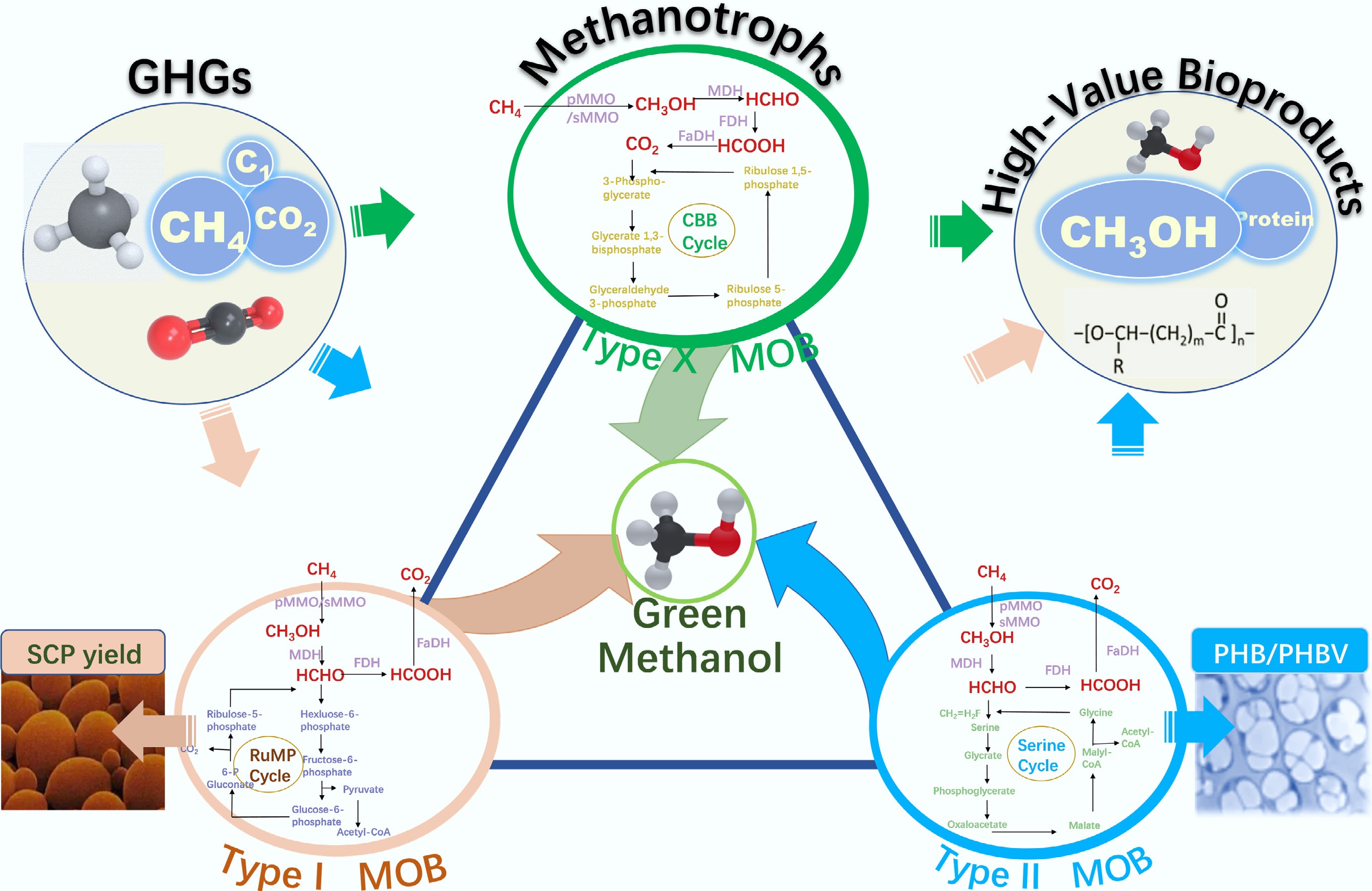

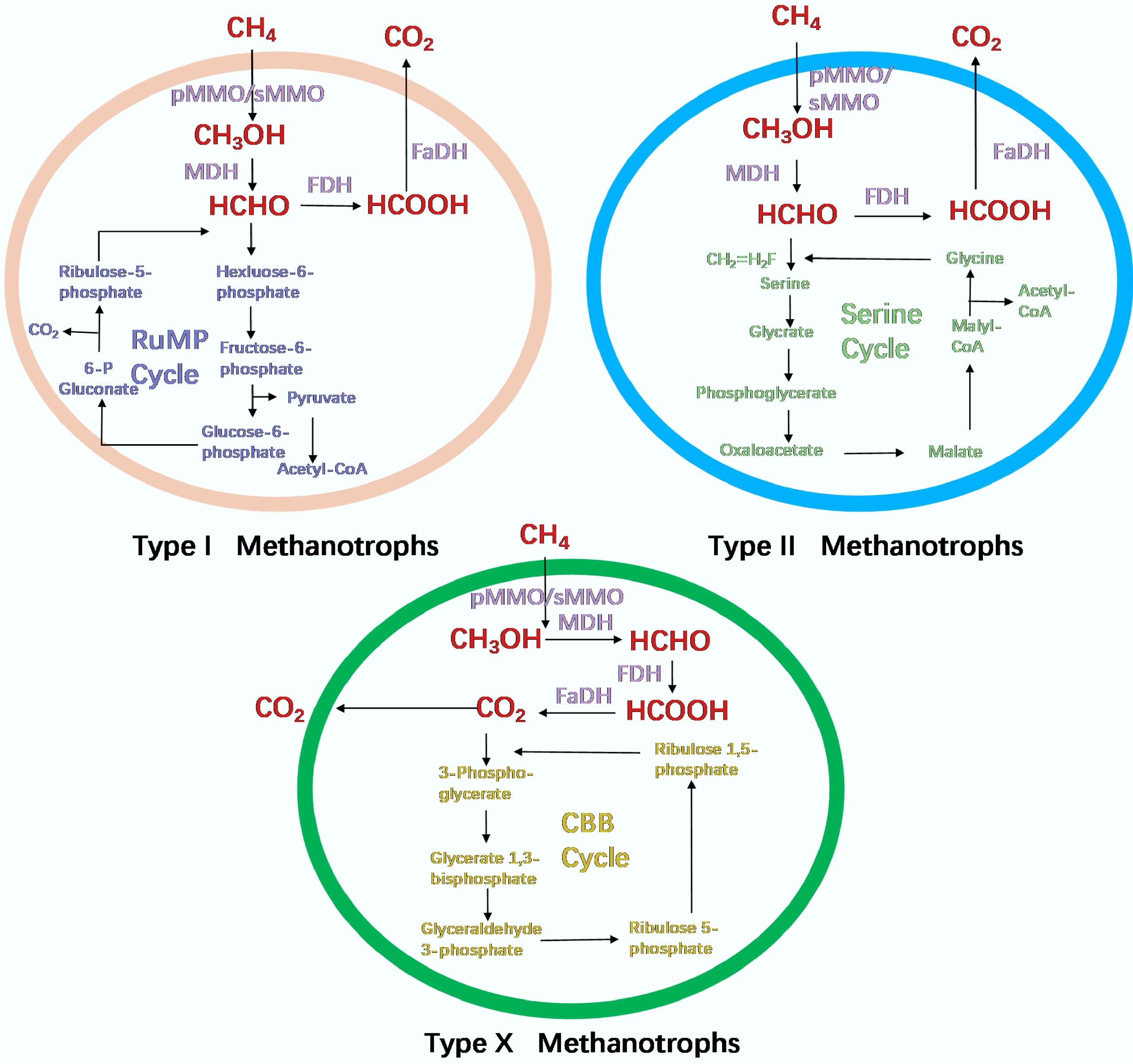

Based on phylogenetic divergence and distinct carbon assimilation pathways, aerobic methanotrophs are primarily classified into Type I (Gammaproteobacteria), Type II (Alphaproteobacteria), and Type X (primarily belonging to Verrucomicrobia)[29,30]. Type I methanotrophs, characterized by intracellular membrane systems arranged as vesicular disks or bundles, predominantly drive methane oxidation in high-methane environments such as wetlands, hot springs, and marine ecosystems; in contrast, Type II methanotrophs possess layered intracytoplasmic membranes and demonstrate higher adaptability to low-methane environments, including acidic soils, wetlands, and plant-associated niches; additionally, Type X methanotrophs represent extremophilic lineages with relatively simplified membrane structures, enabling them to thrive under highly acidic and elevated temperature conditions[29,31].

A suite of unique enzyme systems employed by methanotrophs catalyze methane oxidation, primarily including methane monooxygenase (MMO), methanol dehydrogenase (MDH), formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FDH), and formate dehydrogenase (FaDH)[32]. Among these enzymes, MMO is classified into two types: particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) and soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO). Specifically, pMMO is bound to the intracellular membrane and exists in nearly all methanotrophs, while sMMO is only present in a few methanotrophic groups and distributed in the cytoplasm[32]. In addition, there are some methylotrophs lacking MMO in the methane oxidation system, which cannot directly utilize methane but fix carbon using the metabolic products of methane[33]. pMMO and sMMO are structurally and evolutionarily unrelated enzymes, differing fundamentally in their molecular architecture and catalytic mechanisms, and their expression is regulated by distinct trace metal ions: pMMO activity is strictly copper-dependent, whereas sMMO expression requires sufficient iron availability[34]. Moreover, copper concentration acts as a key metabolic switch: elevated copper levels promote pMMO expression, while copper limitation induces sMMO expression[35]. In summary, methanotrophs exhibit considerable diversity in their carbon fixation pathways, which involve markedly distinct intermediate metabolites. Notably, the pmoA gene, encoding a critical subunit of pMMO, is conserved across the majority of methanotrophs and has been established as a key molecular marker for assessing their ecological distribution and abundance in diverse environments[36].

The central metabolic pathway of methanotrophs involves the sequential oxidation of CH4 to methanol, formaldehyde, formate, and ultimately CO2, catalyzed by the key enzymes mentioned above[37]. During this process, pivotal intermediate metabolites can be channeled into different carbon assimilation routes to support either cellular growth or the synthesis of specific bioproducts. Type I methanotrophs predominantly employ the ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) pathway for carbon fixation, with 3-hexulose-6-phosphate synthase acting as a key enzymatic step; whereas Type II methanotrophs utilize the serine pathway, relying on hydroxypyruvate reductase as a critical catalyst; and Type X methanotrophs primarily fix carbon via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle[4]. The diversity in phylogeny and metabolic pathways directly determines their diverse resource utilization potential. Methanotrophs employ three principal electron transfer mechanisms. Type I methanotrophs primarily utilize a direct coupling mechanism for methane oxidation, while Type II methanotrophs predominantly rely on a redox arm mechanism[38]. Under specific physiological or environmental conditions, certain methanotrophs may also engage in an uphill electron transfer mechanism[39]. This metabolic versatility not only expands their potential for applications in biomanufacturing and environmental remediation but also provides a robust physiological foundation for their industrial deployment across diverse scenarios. Metabolic pathways of methanotrophs are demonstrated in Fig. 1, while the representative genera and characteristics of methanotrophic communities are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Metabolic pathways of methanotrophs (adapted from Park & Kim[32]).

Table 1. Representative genera and characteristics of methanotrophic communities

Type Genera Species Representative strains Separation source Characteristics Ref. Type I Methylococcus Methylococcus geothermalis IM1 A geothermal spring Thermophilic (48 °C) [40] Methylomonas Methylomonas methanica MC09 Coastal seawater Halotolerant (seawater) [41] Methylomonas koyamae Fw12E-Y A rice paddy field Methanol-utilizing [42] Methylobacter Methylobacter tundripaludum SV96 Arctic wetland soil Nitrogen-fixing (nifH) [43] Methylovulum Methylovulum miyakonense HT12 Forest soil Formaldehyde-assimilating [44] Methylovulum psychrotolerans Sph1 Low-temperature terrestrial environments Psychrotolerant (2 °C) [45] Methylosoma Methylosoma difficile Lc 2 Lake sediment Nitrogen-fixing (nifH) [46] Methylothermus Methylothermus thermalis MYHT A hot spring Thermophilic (67 °C) [47] Methylothermus subterraneus HTM55 Subsurface hot aquifer Thermophilic (65 °C) [48] Methylogaea Methylogaea oryzae E10 A rice paddy field Nitrogen-fixing (nifH) [49] Methylohalobius Methylohalobius crimeensis 10Ki Hypersaline lakes Extremely halophilic

(15% NaCl)[50] Methylomarinum Methylomarinum vadi IT-4 Marine environment Obligate marine [51] Methyloprofundus Methyloprofundus sedimenti WF1 Marine sediment Nitrogen-fixing (nifH) [52] Methylotenera Methylotenera versatilis 301 Lake sediment Multiple substrate utilization [53] Type II Methylocystis Methylocystis hirsuta CSC1 A groundwater aquifer Special surface structure [54] Methylocella Methylocella silvestris BL2 An acidic forest cambisol Multiple substrate utilization [55] Methylocapsa Methylocapsa aurea KYG A forest soil Multiple substrate utilization [56] Methyloferula Methyloferula stellata AR4 Acidic Sphagnum peat bogst Acidophilia (pH = 3.5) [57] Methylorubrum Methylorubrum rhodesianum MB200 A household biodigester Multiple substrate utilization [58] Methylobrevis Methylobrevis albus L22 Freshwater lake sediment Oxidase and catalase production [59] Type X Methylacidiphilum Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV Volcanic region Hydrogenase-possessing [60] Methylacidiphilum infernorum V4 A geothermal field Hyperthermophilic (60 °C) [61] Methylacidimicrobium Methylacidimicrobium fagopyrum 3C Volcanic soil Acidophilia (pH = 0.6) [62] Methylacidimicrobium tartarophylax 4AC Volcanic soil Acidophilia (pH = 0.5) Methylacidimicrobium cyclopophantes 3B Volcanic soil Acidophilia (pH = 3.6) Candidatus Methylacidithermus Candidatus Methylacidithermus pantelleriae PQ17 Volcanic environments Sulfur-fixing (cysD/C/H) [63] Methylotrophs Methylophaga Methylophaga marina ATCC 35842 Sea water Fructose and methylamine utilization [64] Methylophaga thalassica ATCC 33146 Sea water Fructose and methylamine utilization Methylotenera Methylotenera mobilis JLW8 Lake sediment Methylamine-utilizing [65] Hyphomicrobium Hyphomicrobium denitrificans TK 0415 − Anaerobic denitrification [66] Paracoccus Paracoccus denitrificans Stanier 381 Garden soil Hydrogen-utilizing [67] Methyloversatilis Methyloversatilis universalis FAM5 Freshwater wetlands Multiple substrate utilization [68] Methylopila Methylopila capsulata IM1 Soil Multiple substrate utilization [69] Habitats and global prevalence

-

On a global scale, distinct methanotroph species possess specific habitat preferences. While the majority thrive under mesophilic and neutral pH conditions, certain methanotrophic lineages have adapted to extreme environments, displaying thermophilic, acidophilic, or alkaliphilic characteristics[70,71]. A recent study in 2025 revealed that Mycobacterium (Actinobacteria) also possesses methane-oxidizing capabilities, and strain MM-1 shows significant NH3 tolerance and pH tolerance, maintaining activity even at an NH4+ concentration of 143 mM and pH = 4[72]. This finding has significantly expanded the known physiological boundaries of methanotrophs and provides a new microbial resource for methane emission reduction in high-ammonia environments such as livestock and poultry farms, and landfills.

In terms of specific sites, the community structure and spatial distribution of methanotrophs are co-regulated by climatic and edaphic factors. Methanotroph abundance is generally elevated in regions with favorable hydrothermal conditions[36], showing a positive correlation with pH and a negative correlation with concentrations of ammonium and nitrate nitrogen[73]. Significant functional differentiation is observed across distinct habitats, and aside from spatial heterogeneity, methanotroph populations also display marked seasonal fluctuations. For instance, their abundance in aquatic ecosystems is influenced by hydrological characteristics and seasonal variations in dissolved constituents[74]. Although summer typically offers richer nutrient availability and higher overall bacterial abundance, the relative abundance of methanotrophs in certain rivers and lakes has been reported to peak during winter[74], which may be attributed to a combination of factors such as elevated dissolved oxygen levels, reduced solar radiation, and higher organic carbon content during the colder months[75].

Cultivation and separation methods

-

The optimal growth temperature for most methanotrophs is approximately 30 °C, with a preferred pH near neutral (around 7.0)[76]. Nevertheless, some acidophilic and thermophilic methanotrophs have been successfully cultivated and isolated under high temperatures and low pH. For example, Verrucomicrobia bacteria can be cultivated at 55 °C and pH = 3[77]. In terms of carbon sources, methanotrophs typically use methane as a growth substrate, but they differ in substrate affinity. Low-affinity methanotrophs typically require high methane concentrations for cultivation, whereas high-affinity methanotrophs are capable of metabolizing atmospheric trace methane[78]. Commonly, standard cultivation media include nitrate mineral salts (NMS) and ammonium mineral salts (AMS)[79]. Notably, certain methanotrophic strains can fix atmospheric nitrogen, enabling growth in media devoid of exogenous nitrogen sources[80]. Beyond nitrogen, essential mineral salts must be supplemented, as several metal ions act as cofactors of key enzymes in methane oxidation. As mentioned above, MMO activity depends on Cu or Fe[35]. Similarly, the XoxF-type MDH requires lanthanide elements such as Ce, Eu, or Yb to function[81]. In addition, methanotrophs display considerable divergence in salt tolerance, because of which medium composition can be directionally optimized according to the ecological origin and physiological type of the strain. For example, dilute nitrate mineral salt (DNMS) medium may be employed for strains inhabiting low-salt environments[82]; whereas ammonium-nitrate mineral salt (ANMS) medium with 3% NaCl may be utilized for marine strains[83].

Conventional procedures for obtaining methanotrophs typically involve environmental sampling, microscopic examination, and enrichment culture[16]. Common inoculum sources include paddy soils[14,84], marine sediments[83], and biodesulfurization filter beds[85]. However, due to the propensity of methanotrophs to form microbial aggregates with heterotrophic bacteria, obtaining axenic colonies remains challenging[86]. Traditional isolation methods such as the 'dilution to extinction' technique, consume a large amount of time and effort[86]. It has been reported that increasing the dilution rate gradually can improve specific growth rate to 0.40 h−1, yet this approach is generally effective only for fast-growing species[87]. In recent years, several novel separation strategies have been developed to improve the isolation efficiency of methanotrophs[16]. For instance, a label-free, high-throughput Raman-activated cell sorting platform (pDEP-DLD-RACS), pioneered by Qingdao Single-Cell Biotechnology Co., Ltd, enables rapid screening of target live cells based on metabolic function[88]. Raman flow cytometry can achieve a 58% yield improvement of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) over wild-type strains by sorting DHA-overproducing mutants within two days[88]. This advanced methodology provides a powerful tool for the efficient and precise acquisition of functional methanotrophic strains.

-

Conventional approaches to mitigating methane emissions from various sources (such as fugitive releases during biogas utilization) often focus on suppressing methanogenesis at the source, such as adding chemical inhibitors to suppress methanogenic activity[89]. As a complementary strategy, the use of methanotrophs for methane removal offers distinct advantages, including applicability across diverse locations and emission modes[90]. For example, in mining operations, the application of ultrafine water mists containing methanotrophs has been shown to reduce methane concentrations in ambient air, lowering the risk of gas explosions[91]. Currently, a range of methanotroph-based engineering solutions has been developed, such as bio-cover systems, biofiltration units, and bacterial suspension injection, enabling efficient methane removal tailored to different operational scenarios[92]. Representative applications include exhaust treatment in biogas upgrading facilities[93], rhizoremediation of diesel-contaminated soils[94], and mitigation of methane and odorous compounds in landfill sites[95]. Furthermore, during wastewater treatment, methanotrophs can simultaneously remove dissolved methane and nitrite, achieving synergistic reduction of greenhouse gases and pollutants[96].

However, the regulatory role of methanotrophs in greenhouse gas dynamics is bidirectional: while oxidizing CH4, they may inadvertently trigger the emission of other greenhouse gases. For instance, aerobic methanotrophs can compete with denitrifying bacteria for Cu2+, potentially suppressing denitrification activity and leading to N2O release[97]. Similarly, certain anaerobic methanotrophs have been reported to generate N2O via NO dismutation during denitrification[98]. Given that the GWP of N2O is approximately 10 times that of CH4 over 100 years, even minor N2O emissions can substantially offset the climate benefits gained from CH4 oxidation[90]. Therefore, controlling concomitant N2O emissions is critical for maximizing net greenhouse gas mitigation. Notably, some methanotrophs possess N2O reductase genes, enabling them to concurrently remove both CH4 and N2O[98]. Certain aerobic methanotrophs, such as Methylocella tundrae and Methylacidiphilum caldifontis, can grow under anaerobic conditions, using methanol or C-C substrates (such as pyruvate) as electron donors to respire N2O, and they can also adapt to suboxic environments[99]. Anaerobic oxidation of CH4 by aerobic methanotrophs can be coupled with denitrification, utilizing N2O produced during denitrification as an electron acceptor, significantly reducing emissions of both CH4 and N2O and influencing the net greenhouse effect of the ecosystem[100]. Furthermore, the newly identified anaerobic methanotroph Candidatus Methylomirabilis sinica has been shown to completely reduce nitrate to N2 via a methane-dependent denitrification pathway without N2O production and accumulation, preventing the generation of N2O at the source[101]. This unique metabolic capability offers a promising route for the synergistic mitigation of multiple greenhouse gases.

In addition, microorganisms, including methanotrophs, can act as effective bioindicators for oil and gas resource exploration[102]. In petroleum reservoir areas, the upward seepage of light hydrocarbons causes an increase in surface methane, which in turn induces specific changes in the abundance and community structure of methanotrophs, and a significant positive correlation has been observed between their population density and the intensity of hydrocarbon seepage[103]. Compared to traditional exploration techniques, which are often characterized by high costs and long operational cycles[104], microbial prospecting of oil and gas offers considerable advantages, including lower expense and higher sensitivity[105].

Synthesis of high-value products

-

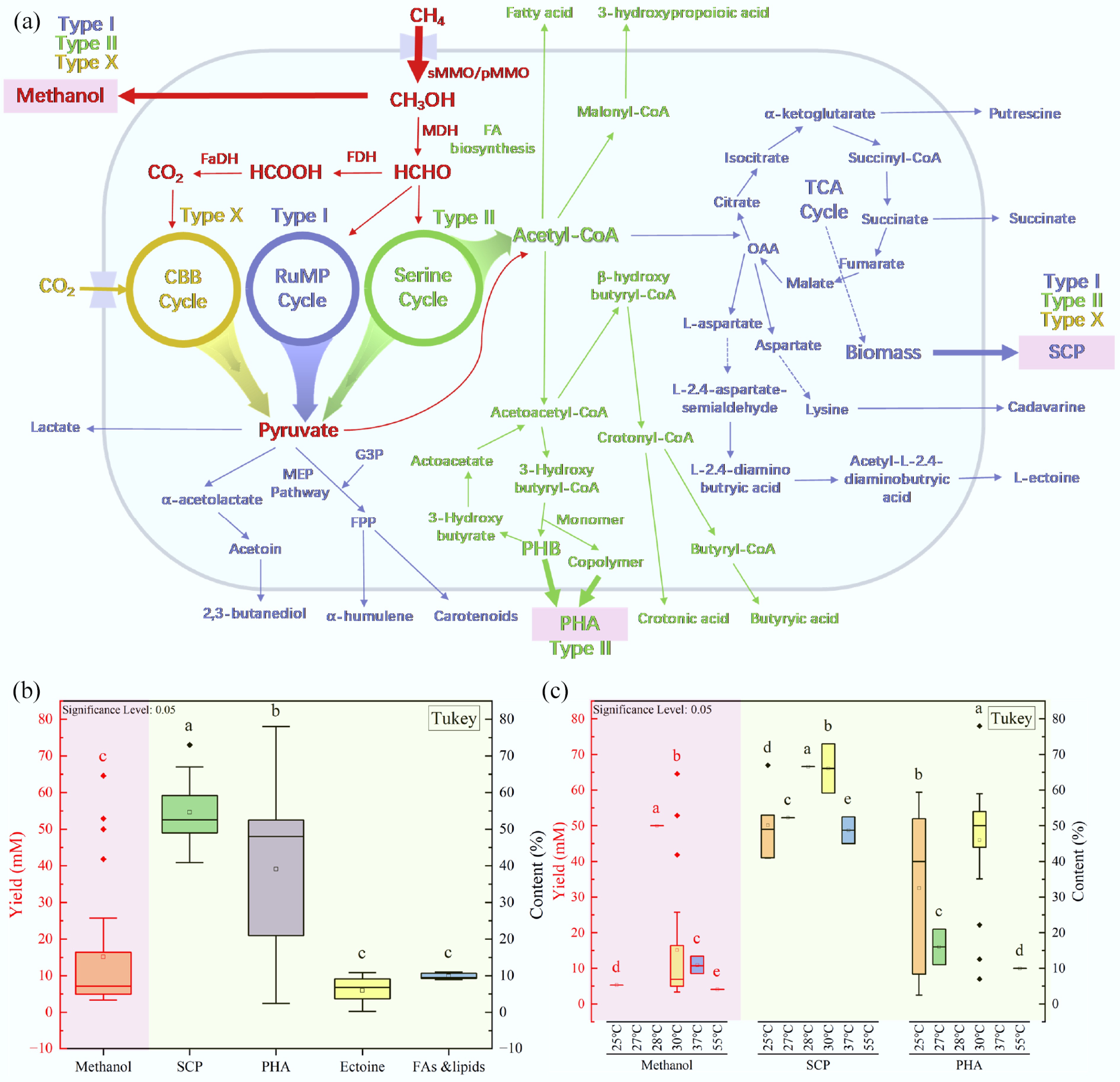

Methanotrophs not only contribute to greenhouse gas mitigation but also synthesize a range of value-added products through carbon assimilation pathways. Currently, methanotrophs are capable of synthesizing high-value resources such as methanol[77], single-cell protein (SCP)[14], polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)[106], ectoine[107], fatty acids and lipids[108], succinate[109], carotenoids[82], and so on. Additionally, methanotrophs can be co-cultured with other microorganisms to produce new products such as mevalonate[110]. As shown in Fig. 2, pyruvate and acetyl-CoA play pivotal roles in the high-value product production of methanotrophs. Overall, Type I methanotrophs are suited to producing pyruvate-related products, while Type II methanotrophs are suited for products originating from acetyl-CoA. Due to the anaplerotic role of the RuMP cycle towards the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, Type I methanotrophs are more capable of producing certain products related to the TCA cycle.

Figure 2.

Pathways for high-value product production by (a) methanotrophs, (b) yields of primary high-value products, and (c) yields of key high-value products with large-scale production potential at common reaction temperatures (G3P: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; MEP: Methyl-erythritol Phosphate; FPP: Farnesyl Pyrophosphate; PHB: Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate; OAA: Oxaloacetate, FA: Fatty acid. Data are sourced from the literature[111], and Tables 3[112−119], 4[85,120−124], and 5[106,125−131]).

However, the primary products that have reached scale-up production include methanol, SCP, and PHA[111]. Although challenges remain in regulating carbon flux and optimizing the expression of key enzymes during large-scale production[111], their application potential in sectors including food and pharmaceuticals is considerable. A systematic comparison of the production status for three major value-added products is summarized in Table 2. The cases of methanol, SCP, and PHA production by methanotrophs are shown in Tables 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

Production Methanol SCP PHA Biosynthesis pathway Central metabolic pathway Multiple carbon assimilation pathways Serine carbon assimilation pathway Producers Type I, II, and X capable Type I dominant, Type II, and X applicable Primarily type II Product value Moderate Relatively low Relatively high Commercialisation status Not yet commercialised Large-scale commercialisation Small-scale commercialisation Carbon conversion challenges Methanol is a metabolic intermediate that is readily oxidized, leading to low accumulation. The production requires maximized carbon flux toward biomass and suppression of complete oxidation. The production is typically induced under nutrient imbalance, creating a growth-synthesis trade-off. Applications Chemical feedstocks, fuel, bioplastic precursors Animal feed, food additives, nutrient supplements Biodegradable plastics, biomedical materials Methanol production

-

Methanol serves as a crucial industrial feedstock and clean fuel, valued for its high energy density and ease of storage and transportation[132], with broad applications across the energy and chemical sectors. Compared with conventional catalytic synthesis processes, which are typically energy-intensive, methanotroph-based conversion of CH4 to methanol operates under mild conditions and offers distinct advantages such as minimal byproduct formation and reduced process carbon emissions[133]. In practical applications, the immobilization of methanotrophic cells has been shown to improve both the efficiency and operational stability of methanol production, and various materials such as coconut shell biochar, ion-exchange resins, and chemically modified chitosan have been employed as effective immobilization carriers, some of which can achieve a maximum yield increase of more than 20 times[112−114]. However, these supports differ significantly in mass transfer efficiency and operational costs, necessitating careful selection based on the specific production system. Interestingly, it has been reported that a thermophilic methanotroph species can reduce CO2 to methanol via the CBB cycle[115], providing promising prospects for the synergistic resource utilization of greenhouse gases.

It has been indicated that the methanol production yield by methanotrophs ranges between 5.34 and 64.6 mM (Table 3)[115,116]. The production efficiency is influenced by multiple factors including strain type, gas composition, immobilization carrier, and cultivation conditions. Among the investigated species, Methylocystis bryophila has demonstrated robust methanol synthesis capability in several studies[113,116], and is often applied in combination with other methanotrophs such as Methyloferula stellata[112,114,117]. Culturing with 20%–30% CH4 or a CH4 : CO2 ratio of 2:1 to 4:1 can improve the output of methanol[112−114], and coupling with 15% H2 can attain a methanol yield of up to 64.6 mM[116]. In addition, certain methanotrophs, including Methylocaldum sp., exhibit notable tolerance to sulfur impurities (500 ppm H2S), highlighting their potential applicability in the treatment of real industrial off-gases[118].

Table 3. Cases of methanol production by methanotrophs

Production Output Production condition Corresponding producer Ref. Methanol 52.9 mM 30% CH4, 30 °C, NMS medium, immobilized on coconut coir, eight repeated batch conditions Methylocystis bryophila, Methyloferula stellata, Methylocella tundrae [112] Methanol 25.75 mM CH4 : CO2 = 2:1, 30 °C, NMS medium, immobilized on chitosan, eight repeated batch conditions Methylocystis bryophilla [113] Methanol 24.36 mM CH4 : CO2 = 4:1, 30% CH4, 30 °C, NMS medium, immobilized on chemically modified chitosan, eight repeated batch conditions Methylomicrobium album, Methylocystis bryophila, Methyloferula stellata [114] Methanol 5.34 mM Cultivation in biogas containing CH4, 25 °C, AMS medium, six repeated batch conditions Primarily Methylobacter and Methylosarcina [115] Methanol 64.6 mM 30% CH4, 15% H2, 30 °C, NMS medium, six repeated batch conditions Metholosinus sporium, Methylocystis bryophila [116] Methanol 16.4 mM 30% CH4, 15% CO2, 30 °C, NMS medium, immobilized on synthetic precursor solution, ten repeated batch conditions Methyloferula stellata, Methylocystis bryophila [117] Methanol 8.59 mM CH4 : air = 1:4, 37 °C, NMS medium, 500 ppm H2S Methylocaldum sp. [118] Methanol 5.37 mM 30% CH4, 30 °C, NMS medium, immobilized on polyvinyl alcohol, five repeated batch conditions Methylocystis bryophila, Methyloferula stellata [119] SCP production

-

SCP, also referred to as microbial protein, represents a resource-efficient alternative protein source[134,135]. It is characterized by rapid growth rates and high spatial productivity[136], offering a sustainable pathway to alleviate the environmental pressures associated with conventional protein production. Methanotrophs possess strong protein biosynthesis capacity and can utilize methane-containing waste gases like biogas as substrates to enable the valorization of pollutants[137]. These microorganisms can be cultivated either in pure culture or in co-culture systems with other functional bacteria, such as sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB), to optimize both protein yield and amino acid profile[14,85,120]. It has been shown that methanotroph-derived SCP is rich in diverse amino acids, including essential amino acids[14], and sulfur-containing amino acids[85,120], meeting the nutritional standards for feed applications, whereas its potential use in the food industry still entails certain safety and regulatory considerations[4].

It has been indicated that SCP synthesized by methanotroph generally possesses high protein content, with reported values ranging from 41% to 73% of cell dry weight (Table 4)[85,121]. Representative methanotrophic genera employed in SCP production include Methylococcus[122], Methylosinus[123], and Methylomonas[121], and non-methanotrophs such as Terrimonas[14] and Chryseobacterium[85,120] are also frequently present in production consortia. In current practice, optimal SCP content is typically achieved using a CH4 : O2 ratio between 1:4 and 2:3[85,124], supplemented with controlled amounts of CO2[138], and a cultivation temperature maintained within 25–37 °C[121,122].

Table 4. Cases of SCP production by methanotrophs

Production Content Production condition Corresponding producer Ref. SCP 56.10% ± 10.99% CH4 : O2 = 1:2, NMS medium, 2,973 ppm H2S Primarily Methylocystis and Terrimonas [14] SCP 73% ± 5% CH4 : O2 = 2:3, 30 °C, NMS medium, 1,500 ppm H2S Primarily Methylocystis spp. and Chryseobacterium spp. [85] SCP 59.2% ± 3.6% CH4 : CO2 = 70:30 or 50:50, CH4 : O2 = 2:3, 30 °C,

AMS medium, 4,000 ppm H2SPrimarily Methylocystis spp. and Chryseobacterium spp. [120] SCP 41% ± 2.0% CH4 : O2 = 1:2, 25 °C, dAMS medium Primarily Methylophilus sp.1 and Methylomonas sp.1 [121] SCP 45% 60% CH4, 30% O2, 10% CO2, 37 °C, cultivation in

wastewater containing NH4+Methylococcus capsulatus [122] SCP 52.3% 60% CH4, 40% CO2, 27 °C, AMS medium Primarily Methylosinus and Methylococcus [123] SCP 67% CH4 : O2 = 1:4, 25 °C, AMS medium Primarily Methylomonadaceae and Methylococcaceae [124] SCP 50.2% Primarily CH4 : O2 : CO2 = 1:2:0.05, NMS medium Primarily Methylococcus and Methylotenera [138] dAMS: dilute ammonium mineral salt. PHA production

-

PHA represents a class of biodegradable polyesters that serve as environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional petroleum-based plastics[139]. To achieve cost-effective production, C1 gases such as CH4 from biogas or industrial off-gases can be utilized as economical carbon sources for large-scale PHA synthesis by methanotrophs[140]. Within the PHA family, poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) is the most prevalent homopolymer[141], exhibiting mechanical properties comparable to those of traditional polyolefins[111]. Methanotrophs possess the capacity to accumulate intracellular carbon reserves, with PHA primarily synthesized by Type II strains, whereas Type I strains tend to produce extracellular polysaccharides[125].

It has been indicated that the methanotroph-derived poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) content can reach up to 59.4% (Table 5)[126]. The polymer composition can be modulated by supplementing specific co-substrates. For instance, the addition of valerate promotes the incorporation of 3-hydroxyvalerate monomers, leading to the formation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) copolymers with improved mechanical properties[127]. Methylocystis sp. MJC1 has been reported to synthesize PHBV copolymers with a content of 41.9%. In an optimized medium, Methylocystis parvus OBBP reached a PHA content of approximately 54%[128]. Under specific recovery strategies, genera such as Methylocystis and Pseudomonas can reach PHB content approaching 60%[126]. Optimal production conditions, typically involving a CH4 : O2 ratio between 1:1 and 2:3[128,129] and a temperature range of 25–30 °C[126,128], are critical for achieving high PHA accumulation.

Table 5. Cases of PHA production by methanotrophs

Production Content Production condition Corresponding producer Ref. PHA 12.6% ± 2.4% 20% CH4, 30 °C, AMS medium Primarily Methylocystis [106] PHB 48.7% ± 1.2% CH4 : O2 = 1:1, 30 °C, NFMS medium Primarily Methylophilus and Methylocella [125] PHB 59.4% ± 4.5% CH4 : O2 = 1:1, 25 °C, AMS medium, recycle PHB producers after accumulation Primarily Methylocystis and Pseudomonas [126] PHBV 41.9% 30% CH4, 30 °C, NMS medium Methylocystis sp. MJC1 [127] Mutiple PHA 50% ± 4% to 56% ± 4% CH4 : O2 = 2:3, 30 °C, JM2 medium (modified AMS medium) Methylocystis parvus OBBP [128] PHB 22.20% CH4 : O2 = 1:1, 30 °C, NMS medium Primarily Methylocystis [129] PHBV 35% 0.5 atm CH4, 0.33 atm O2, 38 °C, AMS medium Methylosinus thricosporum OB3b [130] PHB 52.9% ± 4% CH4 : O2 = 1:1, 25 °C, AMS medium Mutiple methanotrophs [131] NFMS: nitrate free mineral salt. -

In the high-value resource valorization of methanotrophs, precise metabolic regulation is key to enhancing the synthesis efficiency of target products. Depending on the characteristics of the desired metabolites, mixed-culture strategies are often employed to optimize system performance through microbial synergies (cross-feeding)[142]. For instance, co-culturing methanotrophs with SOB enables the removal of H2S from biogas, alleviating its inhibitory effect on methanotrophic activity[120]. Similarly, the presence of methylotrophs facilitates the timely consumption of metabolic intermediates such as methanol generated during methane oxidation, preventing feedback inhibition and improving the overall methane oxidation rate[33]. By sharing metabolic byproducts, different microbial species form complementary and symbiotic relationships that help overcome inherent limitations of methanotrophs, including slow growth and sensitivity to accumulated metabolites[33]. Beyond microbial interactions, the modulation of environmental and nutritional factors can effectively direct carbon flux toward target product synthesis. Optimizing the CH4 : O2 ratio, adjusting temperature, selecting appropriate nitrogen sources, and regulating the concentrations of trace elements such as Cu and Fe have all been demonstrated to improve the efficiency of methane-based bioconversion.

Reprogramming central metabolism for methanol yield

-

The high-yield accumulation of methanol relies on the precise regulation of central carbon metabolism—facilitating the conversion of CH4 to methanol while moderately suppressing its downstream oxidation. As the first intermediate in the methanotrophic pathway, methanol contains C–H bonds that are more readily cleaved than those of CH4, rendering it prone to further oxidation[143]. Since methanotrophs constitutively express MDH, which continuously catalyzes methanol oxidation, effective production strategies require targeted inhibition of MDH activity to facilitate methanol accumulation[32]. However, such metabolic interventions must account for cellular energy balance. The oxidation of CH4 to methanol is an energy-consuming process that relies on reducing equivalents such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), whereas subsequent methanol oxidation helps regenerate NADH, thereby forming a cyclic energy supply[144]. Complete inhibition of MDH would lead to NADH depletion, which in turn hinders the initial oxidation step of CH4. Therefore, the ideal strategy is to partially inhibit MDH, enabling net methanol accumulation while maintaining sufficient NADH regeneration[144]. In practice, the extracellular hyperaccumulation of methanol can be achieved by reducing the concentration of lanthanides in the medium to inhibit MDH activity[77] or by adding specific enzyme inhibitors such as cyclopropanol[143]. The intracellular NADH/NAD+ ratio serves as a key indicator of the cellular redox state, providing a basis for the dynamic regulation of inhibitor dosage[144]. In summary, by finely balancing MDH activity with energy metabolism, it is possible to significantly increase methanol yield under mild reaction conditions and overcome the long-standing challenge of its rapid over-oxidation.

Enhancing carbon assimilation for protein synthesis

-

In SCP production, the core objective of metabolic regulation is to maximize biomass yield by directing carbon and energy fluxes toward cellular biosynthesis. Type I methanotrophs are considered preferred candidates for SCP production owing to their rapid growth rates. However, under nitrogen-limited conditions, these microorganisms tend to redirect carbon flux toward the synthesis of storage compounds such as extracellular polysaccharides[125], which can reduce protein yield. Therefore, maintaining an appropriate C/N ratio and ensuring sufficient nitrogen supply are critical to sustaining efficient protein synthesis. It has been shown that the CH4 : O2 ratio significantly influences nitrogen assimilation efficiency. For instance, at a CH4 : O2 ratio of 2:3, nitrogen assimilation approaches completion[85], improving protein synthesis efficiency. Moreover, precise editing of metabolic pathways via synthetic biology, such as the knockout of glycogen synthase or glucokinase genes, can effectively suppress carbon storage formation[145], redirecting more carbon toward protein accumulation. In summary, systematically optimizing cultivation conditions and gas composition, combined with genetic engineering to fine-tune metabolic flux, provides a dual strategy for improving the conversion efficiency of carbon and nitrogen and maximizing protein yield.

Metabolic regulation for PHA hyperconcentration

-

In the production of PHA, the central aim of metabolic regulation is to leverage the synthetic capacity of Type II methanotrophs by redirecting carbon flux toward storage polymer synthesis under specific nutrient-limiting conditions. Type II methanotrophs act as the primary microbial workhorses of PHA synthesis, and their pure culture system is more conducive to the efficient accumulation of PHA[130]. However, in industrial settings, inocula often consist of mixed communities of Type I and Type II methanotrophs, where interspecific competition can compromise the stability of PHA production. NH3, due to its structural similarity to CH4, acts as a competitive inhibitor of MMO activity, and this inhibition is more pronounced in Type I methanotrophs, thereby providing a selective advantage to Type II strains and helping them dominate the microbial community[126]. Nevertheless, if the sludge retention time (SRT) is excessively prolonged, Type I methanotrophs may adapt to the NH3 stress and re-establish dominance, ultimately reducing PHA synthesis efficiency[131]. In addition, the capacity for PHA accumulation varies across growth phases, with higher synthesis rates typically observed during the lag and exponential phases compared to the stationary phase[79]. Therefore, appropriately optimizing operational conditions to extend the duration of these two phases may represent a viable strategy for improving overall PHA productivity.

The synthesis efficiency of PHA is regulated by multiple environmental parameters, including carbon source availability, temperature, pH, and the type of nitrogen source. Appropriately increasing the partial pressure of CH4 can improve O2 utilization and promote PHA accumulation[130]. Certain non-growth co-substrates such as ethane may inhibit methane oxidation, yet their metabolic derivative acetate can act as a precursor of PHA biosynthesis, indirectly facilitating polymer formation[146]. Temperature and pH exert selective influences on community structure. When strains with strong PHA production capabilities become dominant, the yield is improved. For instance, the higher abundance of Methylocystis facilitates PHA production at 25–30 °C, while deviations from this range can significantly impair metabolic activity[147]. Similarly, while genera of high-yield PHA, such as Methylocystis, exhibit a competitive advantage within pH 5.5–7.0, which is conducive to PHA production[148]. There remains considerable controversy regarding nitrogen source selection: some studies suggest nitrate is preferable due to its minimal inhibitory effect on MMO activity[149], whereas others report that ammonium exerts weaker inhibition on Type II methanotrophs harboring ammonium tolerance genes, which facilitates their enrichment[126]. No-nitrogen (NoN) conditions can trigger PHA accumulation as a carbon reserve[79], but they also retard biomass growth. Therefore, future research may need to tailor nitrogen source strategies according to the genetic background of specific strains and process objectives rather than seeking a universal solution.

To achieve high-efficiency synthesis of PHA, a variety of strategic approaches have been developed. The selection of inoculum sources selection is fundamental, with priority given to environmental samples enriched with Type II methanotrophs. For example, methanotrophs derived from Sphagnum moss can raise the baseline potential of the production system[150]. At the process level, biomass recycling after the PHA accumulation phase can help reduce the proportion of Type I methanotrophs, while alternating nitrogen supply regimes can optimize resource allocation between growth and synthesis phases[126]. It has been indicated that nitrogen-feeding and starvation cycles of 8 h:16 h or 24 h:24 h yield the best results, whereas excessively long nitrogen starvation (2-fold higher than the feeding duration) inhibits PHA production[151]. Furthermore, the construction of co-culture systems coupling methanotrophs with heterotrophic bacteria such as Methylocystis sp. OK1 with Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) enables multi-directional cross-feeding[152]. In such systems, intermediates like acetone generated by Methylocystis can be utilized by E. coli for heterologous PHA synthesis, extending carbon flux and doubling overall productivity[152]. Looking forward, metabolic regulation in PHA production should evolve from single-factor optimization toward multi-scale metabolic network engineering. Integrating strain selection, process control, and system coupling will pave the way for comprehensive efficiency enhancement.

-

Methanotrophs play a pivotal role in the global carbon cycle and hold significant potential for sustainable biomanufacturing. They demonstrate considerable promise in methane emission mitigation, ecological restoration, and the synthesis of high-value products such as green methanol, SCP, and PHA. The discovery of novel species with unique traits like ammonium tolerance and pH tolerance, as well as direct denitrification, further expands their application scope. However, challenges in cultivation, metabolic complexity, and process stability hinder their large-scale deployment. Future efforts should leverage synthetic biology to construct high-capacity microbiological strains and synthetic consortia and even engineer strains with enhanced product yields, develop advanced bioreactors for optimized operation, and establish robust life-cycle assessments to evaluate sustainability. The integrated application of multiple technologies enables the full exploitation of methanotrophs' metabolic potential, which plays a crucial role in driving the large-scale application of negative carbon biotechnology, facilitating carbon neutrality goals, and accomplishing the synergistic control of environmental pollution.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Qigui Niu; investigation: Jingrui Deng, Qigui Niu; writing−Original draft: Jingrui Deng, Junpeng Qiao; writing−review and editing: Qigui Niu, Siyuan Ye, Feiyang Lin, Yu-You Li; visualization: Jingrui Deng; supervision: Qigui Niu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The author's research is supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos 2022YFC3700187 and 2022YFA0912500), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Project No. ZR2024MB158), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51608304), and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Project No. 2025A1515012777). This study contributes to the science plan of the Ocean Negative Carbon Emissions (ONCE) Program.

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Methanotrophs with unique functional traits are summarized.

Divergent metabolic and electron transfer mechanisms are deciphered.

The dual role of methanotrophs in climate change is evaluated.

Species-specific yields of high-value products are benchmarked.

Metabolic regulation underlying efficient PHA biosynthesis is unveiled.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Deng J, Qiao J, Ye S, Lin F, Li YY, et al. 2026. Advances in high-value resource recovery of greenhouse gases driven by methanotrophic communities. Energy & Environment Nexus 2: e002 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0018

Advances in high-value resource recovery of greenhouse gases driven by methanotrophic communities

- Received: 25 October 2025

- Revised: 03 December 2025

- Accepted: 15 December 2025

- Published online: 15 January 2026

Abstract: Amid rising global temperatures and accelerating carbon-neutral initiatives, the efficient valorization of greenhouse gases has emerged as a central focus of contemporary research. Microbial metabolism enables the low-cost transformation of methane, which has evolved into a strategic technological reserve for a green and low-carbon future. Methanotrophs, widely distributed across diverse habitats, utilize methane as both a carbon and an energy source. Through key enzymes in their central metabolic pathways, these microorganisms sequentially oxidize CH4 into methanol, formaldehyde, formate, and ultimately to CO2. In synthetic microbial consortia comprising methanotrophs and methylotrophs, inter-species cross-feeding effectively alleviates the accumulation of inhibitory metabolites, improving overall methane conversion efficiency. Beyond regulating the source-sink balance of atmospheric greenhouse gases, methanotrophic consortia also drive the high-value resource utilization of high-concentration CH4 and CO2. Type I, II, and X methanotrophs possess distinct carbon fixation pathways and are capable of synthesizing high-value products such as methanol, single-cell protein (SCP), and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). Investigating their mechanisms and efficient cultivation strategies is conducive to further exploring the potential of methanotrophs in carbon cycling and biomanufacturing. However, the practical application of methanotrophs still faces several challenges, including difficulties in process control, ineffective suppression of byproduct formation, and potential safety concerns associated with the synthesized products. Addressing these bottlenecks is imperative to unlock their full potential for large-scale industrial applications in greenhouse gas mitigation and sustainable biomanufacturing.