-

As the demand for energy and adverse environmental issues intensify, the search for new, efficient, and environmentally friendly energy storage technology is becoming even more urgent. Supercapacitors are electrochemical energy storage devices that have gained wide attention to solve the problems of insufficient energy and power density of fuel cells and lithium batteries[1−3]. There are two types of supercapacitors, namely pseudocapacitors and electric double-layer supercapacitors (EDLCs), according to the storage mechanisms[4,5]. Therefore, the capacitance of EDLCs depends mainly on the accessible surface area of the electrode material[6]. During charging/discharging, there are no chemical reactions in EDLCs since the energy is stored at the interface between the electrode and electrolyte through the electrostatic action of the charge, which generally makes them have higher power density and better cycling stability than pseudo-supercapacitors[7].

Biochar-based porous materials, which usually have a high specific surface area, a high degree of graphitization, and good electrical and chemical stability, are ideal for preparing electrode materials for EDLCs application[8,9]. Amongst the various biomass feedstocks, cellulose-based polymer materials or glucose (the composition unit of cellulose) can be used to prepare versatile porous biochars with optimized hetero-electrochemical properties through hydrothermal carbonization coupled with pyrolysis activation[10]. The key to the advantage of this route is that the cellulose-based feedstock is first readily converted in to carbon spheres through hydrothermal treatment. Although the prepared hydrothermal carbon spheres (HTCs) have the advantage of rich functional groups, the hydrothermal process causes agglomeration of HTCs, making the specific surface area small, and hinders their direct application[11]. However, the agglomerated HTCs are an ideal framework for preparing porous biochar through activation of the perforation.

The number of cigarettes consumed globally exceeds 5.8 trillion annually, generating about 8 million tons of discarded cigarette butts (CBs)[12,13]. This waste, primarily composed of cellulose (outer packaging), and cellulose acetate (filter tip), is notoriously difficult to degrade and contains many harmful substances, such as volatile organic compounds, heavy metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, among others[14−16]. A green and efficient use for the cigarette butts is urgently needed. Recently, some CBs derived carbon materials, with developed pore structure and rich surface groups, have been reported and have shown superior environmental remediation performance in hydrogen storage[12], ciprofloxacin and sodium dodecyl sulfate adsorption[17], and edible oils decolorization[18]. Although CBs have the potential to prepare high-quality porous carbon materials as energy storage materials, the relevant research is very limited. In addition, doping with heteroatoms like nitrogen and oxygen can enhance the electrical conductivity of porous biochar materials by providing more active sites without affecting the basic structure, thus improving their supercapacitor's electrical storage performance, especially in specific capacitance[19−21].

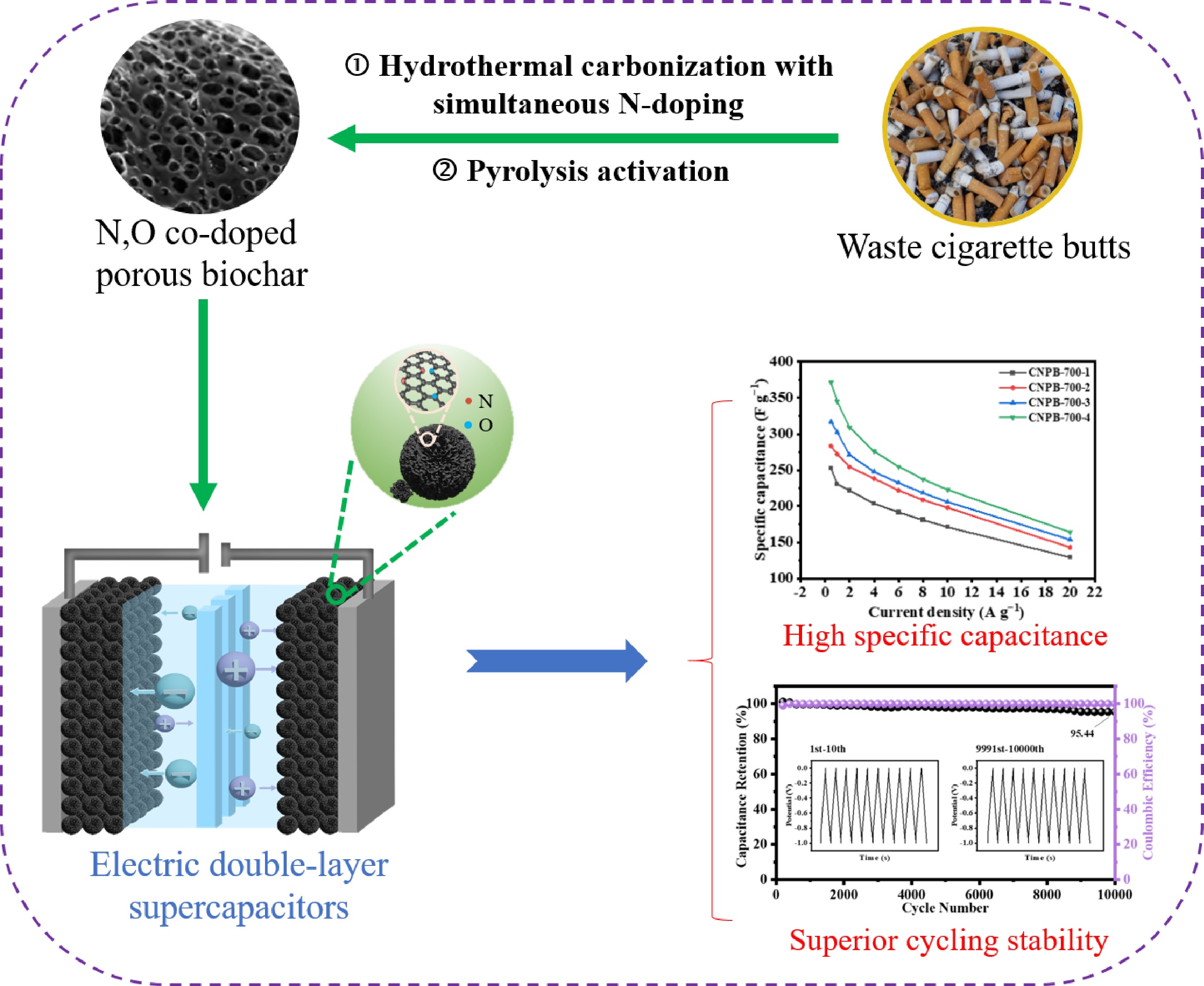

In this paper, waste CBs derived N,O co-doped porous carbon (CNPB) as an electrode material for supercapacitors was prepared through a process of hydrothermal carbonization through the hydrothermal carbonization coupled with pyrolysis activation. The effects of KOH ratios and pyrolytic temperatures on CNPB's pore structure and surface chemical properties, as well as its energy storage performance, were investigated. This study demonstrated the favorable conversion of cigarette butts into porous carbons for high performance energy storage applications.

-

Waste CBs were collected from public areas such as roadsides in Kaifeng city (China) and were pretreated to remove residual tobacco ashes and impurities. The obtained butts were crushed into a fluffy state, and dried at 60 °C for 2 h, and stored in a rapid glass dryer before use. Concentrated hydrochloric acid, potassium hydroxide (analytical grade), urea (analytical grade), acetylene black, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), and foam nickel were all acquired from Aladdin Reagent Company (Shanghai, China).

Hydrothermal carbonization of cigarette butts

-

As a pre-carbonization step, CBs (5 g) and urea (5 mmol) were thoroughly mixed using deionized water (50 mL) and placed in a hydrothermal autoclave (YSFB-100, Yushen Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). The autoclave was kept in an oven and reacted at 250 °C for 120 min. Afterwards, the autoclave was removed and allowed to cool to room temperature. The reacted mixture was filtered, and the solid residue was thoroughly washed with ethanol and deionized water until the washings were neutral. After being dried at 80 °C for 12 h, the N-hydrochar was obtained.

Preparation of N-doped porous biochar

-

The mixture of KOH and N-hydrochar with different mass ratios was well ground and pyrolyzed in a CHY-1200 tube furnace (Chengyi Technology Co., Ltd, Zhengzhou, China) for 2 h at the target temperatures under a nitrogen atmosphere (25 mL min−1), and a pressure of 1 bar. Afterwards, the carbonized samples were washed with diluted hydrochloric acid, anhydrous ethanol, and deionized water until neutral. After being dried at 80 °C for 12 h, the N,O-doped porous biochar was obtained and named as CNPB-X-Y, where X represented the pyrolytic temperatures (600, 700, 800, and 900 °C), and Y represented the KOH to N-hydrochar ratios (1, 2, and 4).

Material characterization

-

The elemental compositions (C/H/N/O) of CBs, hydrochars, and CNPBs were analyzed using an elemental analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar, Germany). SEM (scanning electron microscope; Zeiss Merlin Compact, Germany) was used to analyze the morphology of N-hydrochars and CNPBs. XRD (X-ray diffraction; Bruker D8 Advance, Germany) was employed to examine the mineral and crystal properties of N-hydrochars and CNPBs. The pore structure and specific surface area of N-hydrochars and CNPBs were determined using a specific surface area and porosity tester (V-Sorb 2800P, Ultmetrics, China) through the static volumetric method. The Raman spectra of CNPBs were also detected using a laser confocal Raman spectroscopy (LabRAM HR800, Horiba Jobin Yvon, France) to identify their crystallinity. XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fischer, USA) was employed to explore the surface composition of N-hydrochar and CNPBs.

Electrode assembly and electrochemical measurement

-

The electrochemical performance of the prepared CNPBs as electrodes was evaluated using two types of cell configurations (three-electrode and two-electrode, respectively). CNPBs (80 wt%), acetylene black (10 wt%), and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, 10 wt%) were uniformly mixed in ethanol solution. This mixture (8 mg) was constantly stirred to a black paste and was evenly spread over nickel foam (1 cm2), which was then dried at 80 °C for 6 h in a vacuum oven. Finally, it was overlaid with 1 cm × 1.5 cm of nickel foam, which was pressed for 1 min at 10 MPa to obtain the working electrodes. For the three-electrode system, mercury/mercuric oxide, platinum wire electrode, and the above prepared electrodes slices were employed as the reference, the counter, and working electrodes, respectively. All potentials reported for the three-electrode measurements are presented relative to this Hg/HgO reference electrode. In the two-electrode system, the positive and negative electrodes were two mass-identical electrode sheets, and the cellulose septum was placed in the middle of the two electrode sheets to assemble symmetric supercapacitors. A 6 M KOH aqueous electrolyte was used to evaluate the electrochemical performance of both cell configurations.

Using an electrochemical analyzer workstation (CHI-760, Chenhua Instruments, Shanghai, China), the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves, galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) curves, and electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) of the prepared samples were determined. The related setting parameters can be referred to in the Supplementary Fig. S1. The cycling test was performed with continuous GCD cycling (10,000 cycles) at 10 A g−1 over a battery-testing instrument (LAND CT2001A, Lanhe Instruments, Beijing, China).

The discharge specific capacitances of the three- and two-electrode cells could be calculated according to the GCD curves with Eqs (1) and (2), respectively:

$ \rm C_m =\dfrac{I\Delta t}{m \Delta V} $ (1) $ \rm C_m =\dfrac{I \Delta t}{m\Delta V}\times 2 $ (2) where, I (A), Δt (s), m (g), ΔV (V), and Cm (F g−1) represent the discharge current, the discharge time, the electric potential, the weight of the active material, and the discharge specific capacitance, respectively. It is important to note that for the two-electrode system, the capacitance Cm Eq. (2) is normalized by the mass of a single electrode (msingle). However, all device-level energy density (E, Eq. [3]) and power density (P, Eq. [4]) calculations are normalized by the total mass of the active material on both electrodes (mtotal), as is standard for symmetric cells.

Energy density (E, Wh kg−1), and power density (P, W kg−1) were calculated with Eqs (3) and (4), respectively:

$ \text{E }=\dfrac{\text{1}}{\text{2}}\times {\text{C}}_{\text{m}}\times \text{(ΔV}{\text{)}}^{\text{2}} $ (3) $ {P}=\dfrac{\text{E}}{\text{Δt}} $ (4) -

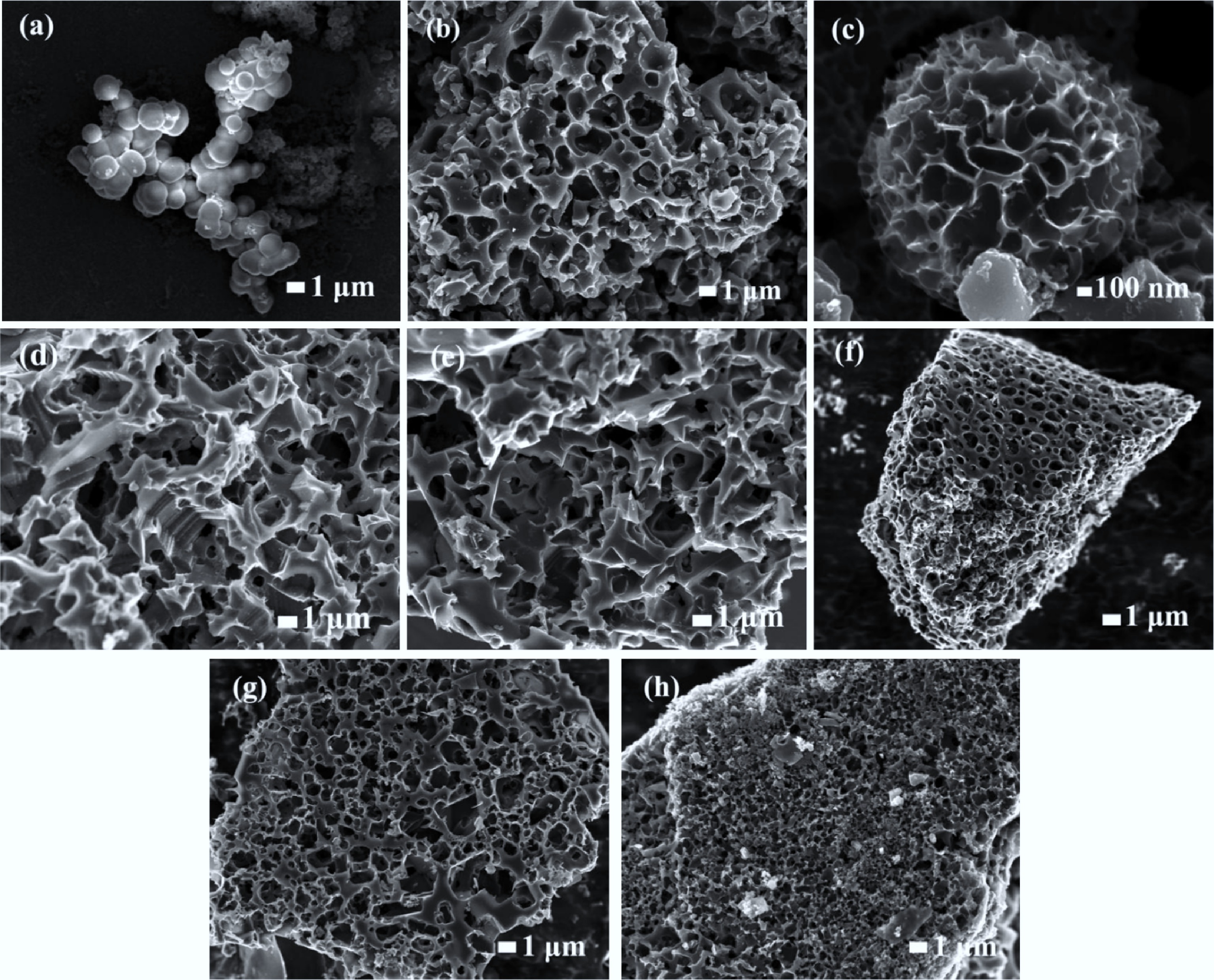

The yields of hydrochar, N-hydrochar, CPB-700-4, and different CNPBs are listed in Table 1. The total process yields of CNPBs ranged from 7.22% for CNPB-900-4 to 19.18% for CNPB-700-1. It can be seen that both activation temperature and KOH ratio significantly influence the yield of CNPBs with a general negative correlation. The prepared N-hydrochar (Fig. 1a) had stacked spherical structures with varying diameters from tens to hundreds of nanometers. There were no openings or pores on its dense and smooth surface, which is consistent with the ordered structure of cellulose acetate. After KOH activation, the SEM images of CNPBs (Fig. 1b & h) revealed their 3D scaffold/spherical porous structures. It has been reported that KOH played a meritorious role in the activation of hydrochar during pyrolysis and undergoes chemical reactions with hydrochar, as described in Eqs (5)–(7)[22]:

$ \rm C(s) + 4KON(s) \to K_{2CO_3} + K_2O(s) +2H_2 $ (5) $ \rm C(s) + K_{2O(s)} \to 2K(s) + CO(g) $ (6) $ \rm K_{2CO_3}+ 2C(s) \to 2K(s) + 3CO(g) $ (7) Table 1. Yields and elemental analysis of hydrochar, N-hydrochar, CPB-700-4, and CNPBs derived from CBs

Sample Yield (%) C (%) H (%) N (%) O (%) H/Cc O/Cc (O+N)/Cc Hydrochar 22.88a 67.11 4.38 0.11 28.40 0.782 0.317 0.319 N-hydrochar 23.67 67.70 5.09 4.77 22.44 0.902 0.248 0.309 CPB-700-4 10.16a/44.41b 77.79 2.82 0.04 18.45 0.436 0.178 0.178 CNPB-600-4 12.95/54.71 57.77 4.39 1.50 36.35 0.911 0.472 0.494 CNPB-700-1 19.18/81.03 76.30 4.43 2.93 15.34 0.697 0.161 0.194 CNPB-700-2 16.32/68.95 75.25 3.03 2.73 18.99 0.484 0.189 0.220 CNPB-700-3 13.26/56.02 73.60 2.44 2.39 21.57 0.560 0.210 0.237 CNPB-700-4 11.25/47.53 77.56 2.59 1.96 23.11 0.401 0.224 0.245 CNPB-800-4 9.86/41.66 82.76 1.86 1.78 13.61 0.270 0.123 0.142 CNPB-900-4 7.22/30.50 87.69 2.63 1.07 8.61 0.360 0.074 0.084 a Calculated based on dried OFR; b Calculated based on dried hydrochar or N-hydrochar; c Atomic ratio.

Figure 1.

SEM images of (a) H-hydrochar, (b) CNPB-600-4, (c) CNPB-700-1, (d) CNPB-700-2, (e) CNPB-700-3, (f) CNPB-700-4, (g) CNPB-800-4, (h) CNPB-900-4.

The surface of CNPB-700-1 started to become rough, and a pleated spherical structure appeared (Fig. 1c). These protrusions could expand the contact area with the electrolyte to promote charge storage[23]. With the KOH ratio increased, the carbon material became looser, and an irregular block structure was formed compared with the original spherical structure (Fig. 1d & f). Rich, irregular, honeycomb-like mesoporous structures were formed, which were in favor of the fast transport of electrons/ions[24,25]. The pore size of CNPBs became more and more regular as the activation temperature increased (Fig. 1b, f & h), indicating that high activation temperatures were beneficial to the growth of uniform pore structures.

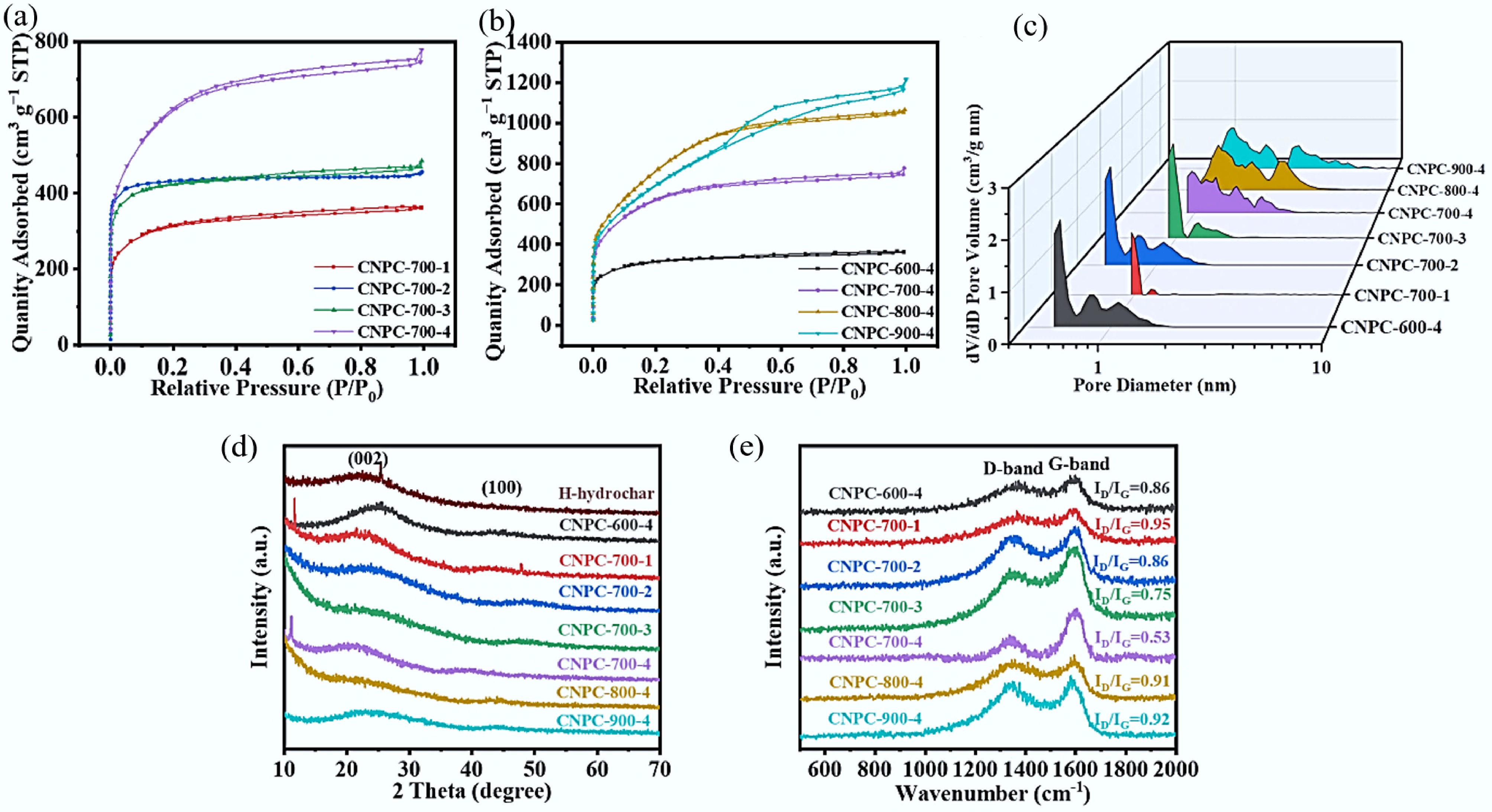

Table 2 shows the pore properties of the prepared carbons. Compared with N-hydrochar, the CNPBs generated from N-hydrochar with different KOH ratios and activation temperatures all had highly developed porosity. Amongst them, CNPB-700-4 showed a high specific surface area of 2,133.5 m2 g−1, a substantial pore volume of 1.203 cm3 g−1 (micropore volume of 0.401 cm3 g−1), and an adsorption average pore width of 2.24 nm. The porosity of the CNPBs were evidently positively influenced by the KOH ratio. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of CNPBs prepared under different activation conditions are shown in Fig. 2a and b. The presence of narrow micropores and multiple micro-mesoporous structures could be evidenced by the steep gas adsorption in the low-pressure region[26] and the H-4 type hysteresis loops[27], respectively, which are in agreement with the pore size distribution plots of CNPBs (mainly in the range of 1–3 nm) in Fig. 2c. The microporosity ratio (Vmic/Vt) increased slightly at 800 °C but decreased significantly at 900 °C due to the development of mesopores[25]. Interestingly, the microporosity (Vmic/Vt) was also closely related to the amount of KOH added. There was a significant decrease in Vmic/Vt at the highest KOH ratio, indicating the micropore volume decreased with increased KOH addition, and the increased mesopore volume provided more channels for the electrolyte diffusion into the micropore[22].

Table 2. Pore structure parameters of N-hydrochar and CNPBs derived from CBs

Sample SBETa (m2 g−1) Smicb (m2 g−1) Vmicc (cm3 g−1) Vtd (cm3 g−1) Vmic/Vt (%) Pore sizee (d, nm) N-hydrochar 7.8 − 0.003 − − 2.51 CNPB-600-4 1,136.9 770.0 0.319 0.560 57.03 2.24 CNPB-700-1 772.3 668.9 0.271 0.407 66.53 2.24 CNPB-700-2 1,683.5 1,529.7 0.599 0.693 86.58 2.22 CNPB-700-3 1,598.8 1,376.5 0.554 0.751 73.72 2.24 CNPB-700-4 2,133.5 903.2 0.401 1.203 33.29 2.24 CNPB-800-4 2,787.2 534.5 0.237 1.649 14.34 2.23 CNPB-900-4 2,492.9 203.6 0.060 1.880 3.21 2.25 a Specific surface area; b Surface area of micropores calculated by the t-plot method; c Micropore volume calculated by the t-plot method; d Total pore volume at P/P0 = 0.99; e Average pore size value.

Figure 2.

(a), (b) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms, (c) pore size distribution, (d) XRD patterns, and (e) Raman spectra of CNPBs prepared under different activation conditions.

The crystallinity composition is also crucial for carbon materials used as supercapacitor electrodes. Figure 2d shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of the prepared materials. The two broad peaks located at 23.5° and 43.5° corresponded to the (002) and (100) planes, respectively, revealing the graphitization of biochar materials, and graphitic carbon is favorable for fast electron transfer in electrochemical reactions[28]. It is noticed that CNPBs presented a significant intensity in the small-angle region of 2θ < 20°, implying the existence of high-density micropores, which is in line with the analysis from the SEM and pore properties analysis. In addition, the peak intensities of CNPB-800-4 and CNPB-900-4 were significantly weaker compared with CNPB-700-4 due to the presence of amorphous carbon structure after KOH activation, implying that the graphitization and crystallinity were reduced considerably[29]. As the temperature increased, the characteristic peak strength of carbon weakened (the broader peaks), indicating an increase in defect and disorder structures as the activation temperature further increased[30,31].

Figure 2e shows the Raman spectroscopy of the samples, which was employed to further investigate their crystallinity. It is well recognized that the D-band (~1,350 cm−1) caused by structural defects is associated with graphite disorder, while the G-band (~1,590 cm−1) corresponds to the carbon atoms in regular graphite crystals[28,32]. The relative graphitization of CNPBs was evaluated by qualitative analysis using the D-band and G-band's integrated intensity ratio (ID/IG). An increased ID/IG indicated that the defect structure developed[32]. The ID/IG values of CNPB-700-1, CNPB-700-2, CNPB-700-3, and CNPB-700-4 were 0.95, 0.86, 0.75, and 0.53, respectively, indicating the lowest disordering degree of CNPB-700-4. The ID/IG values of CNPB-700-4, CNPB-800-4, CNPB-900-4 were 0.53, 0.91, and 0.92, respectively, which could be explained by the fact that high activation temperatures may lead to more defects and disordered structures and more chemical reactions between KOH and the graphitized regions in the carbon particles[33].

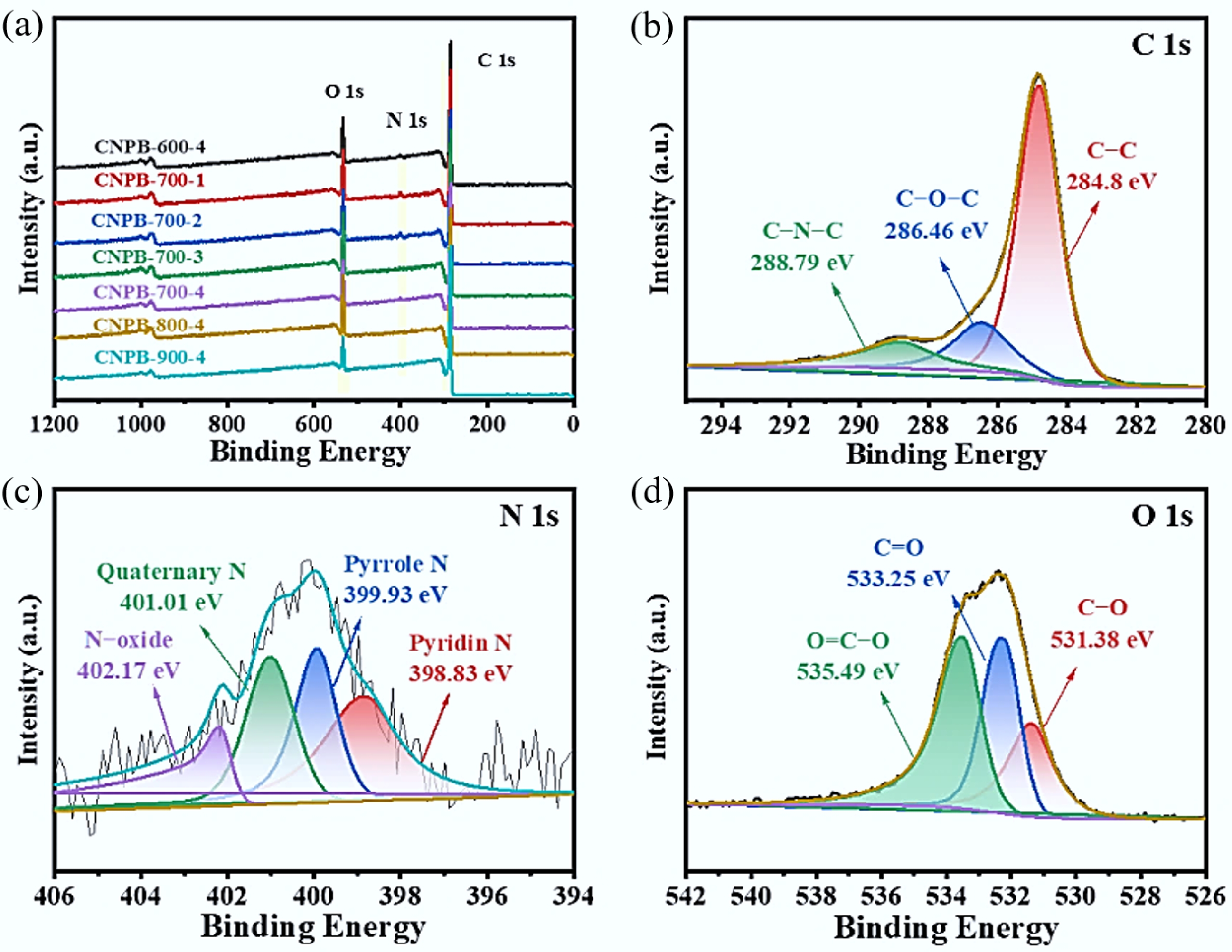

Table 1 shows the elemental composition of the samples. N-hydrochar and CNPBs all contained N with the content range of 1.86 wt% to 4.93 wt%, indicating the successful introduction of N during hydrothermal carbonization with the addition of urea. The surface element composition, valence states, and content of the CNPBs were further characterized through XPS (Fig. 3), demonstrating that the resulting porous carbon materials all consisted of C (284.8 eV), O (530 eV), and N (400 eV) elements, which is in agreement with the results of elemental analysis. The surface nitrogen content of CNPB-700-4 was about 1.82 wt%, close to the elemental analysis (1.96 wt%), meaning that the N elements were uniformly distributed in the framework of the ordered porous biochar.

Figure 3.

(a) XPS measurement spectra of CNPBs prepared under different activation conditions; (b), (c), and (d) fine spectra of C 1s, N 1s, and O 1s of sample CNPB-700-4.

Figure 3b shows the high-resolution C 1s spectrum of CNPB-700-4, which consisted of three resolved individual peaks of C-C (~284.8 eV), C-O-C (~286.46 eV), and C-N-C (~288.79 eV) binding. The high-resolution N 1s spectrum (Fig. 3c) consisted of four peaks of ~398.83, ~399.93, ~401.01, and ~402.17 eV, reflecting pyridine (N-5), pyrrole (N-Q), quaternary (N-4), and N-oxide (N-x) groups, respectively. Among these, the pyridinic (N-5) and pyrrolic (N-Q) groups are particularly renowned for inducing pseudo-capacitance by providing electrochemically active sites for fast, reversible Faradaic reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface. It is recognized that pyridine and pyrrole nitrogen are able to contribute to forming surface and edge defects in carbon materials, which is in favor of increasing the number of active sites for electrochemical reactions such as Faraday processes in Eqs 8 and 9[34], thereby triggering pseudo-capacitance behavior in the charge/discharge process[35]. It is also well recognized that N-Q and nitrous oxide groups in the carbon skeleton can provide positive charges, alter charge density, reduce charge migration resistance, and improve conductivity[36].

$ \rm{ \gt CH{\text-}N}{\text{H}}_{{2}}+\text{2O}{\text{H}}^- \longleftrightarrow { \gt C=NH + 2}{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}+{ 2}{\text{e}}^{-} $ (8) $ \rm { \gt C{\text-}N}{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}+\text{2O}{\text{H}}^-\longleftrightarrow{ \gt C{\text-}NHOH }+{\text{H}}_{\text{2}}\text{O} + 2{\text{e}}^{-} $ (9) The O 1s spectrum (Fig. 3d) demonstrated the three oxygen-based bindings of C-O (~531.38 eV), C=O (~533.25 eV), and COOR (~533.49 eV). These oxygenated groups were able to improve the wettability of carbon materials with aqueous electrolytes and introduce Faraday pseudo-capacitance to enhance their electrochemical capacity[8].

The above characterizations showed the favorable properties of CNPBs, such as the ultra-high specific surface area, feasible pore volume, uniformly distributed adjustable nitrogen atoms, and enhanced wettability to be used as supercapacitor electrode material. The analysis also indicated that CNPB-700-4 potentially possessed the most excellent electrochemical properties amongst the prepared porous biochars.

Electrochemical performance

Three-electrode test

-

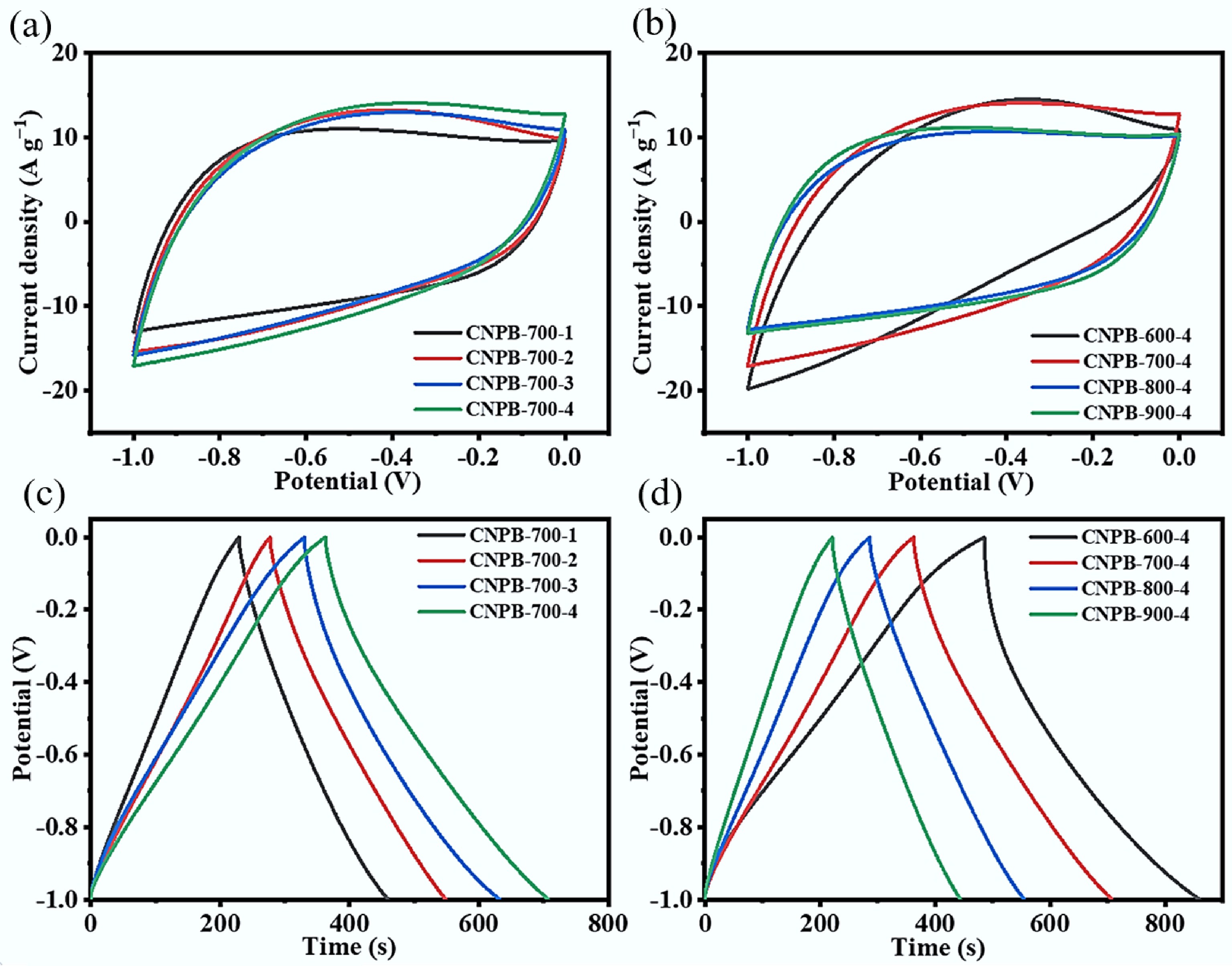

Various electrochemical measurements on CNPBs were performed in a three-electrode system with a 6 mol L−1 KOH aqueous solution as the electrolyte. The cyclic voltammetric curves of CNPBs prepared at various KOH/N-hydrochar mass ratios (Fig. 4a) and pyrolysis temperatures (Fig. 4b) showed similar rectangular features (scan rate = 50 mV s−1) in the potential window of −1.0 to 0 V (vs Hg/HgO), showing that the electrical energy was mainly stored in the electric double layer. The redox peaks can be observed around 0.4 V (Fig. 4a & b), which could be explained by the Faraday pseudo-capacitance generated by the redox reactions of functional groups containing oxygen and nitrogen on the electrode surface[37,38]. Cigarette butt-derived porous biochar, without the introduction of nitrogen, was prepared at 700 °C with a hydrochar and KOH ratio of 4 (CPB-700-4). It was found that N-doping overall enhanced the electrochemical properties of the material (Supplementary Fig. S1). When the activation temperature was 600 °C, the CV curve was distorted, which may be due to the low graphitization order of CNPB-600-4 at a low activation temperature, while as the pyrolysis temperature reached 900 °C, this excessive temperature would lead to the reduction of the remaining functional groups, thus decreasing the total capacitance[39]. The charge/discharge performance of CNPBs was investigated at a current density of 1 A g−1 (Fig. 4c & d), showing that the charge/discharge curves of CNPBs were quasi-triangular in shape, indicating that the prepared CNPBs were supercapacitor materials with electric double-layer capacitive properties. The charge/discharge time of CNPBs tended to proportionally increase with the increasing KOH ratio (Fig. 4c), which also indicated that the regulation of porosity and specific surface area could help to enhance the electrochemical performance of CNPBs. Similarly, it was found that the charging and discharging time of CNPBs showed a decreasing trend with increasing pyrolysis temperature when the amount of KOH addition was identical (Fig. 4d), which might be due to the fact that higher temperatures during the pyrolysis process promoted the conversion of N elements in N-hydrochar to NH3, resulting in a decrease in the nitrogen content of CNPBs (Table 1), thus reducing the pseudo-capacitance provided by N atoms.

Figure 4.

(a), (b) CV curves of prepared CNPBs under different activation conditions at a sweep rate of 50 mV s−1; (c), (d) GCD curves of prepared CNPBs under different activation conditions at a current density of 1 A g−1.

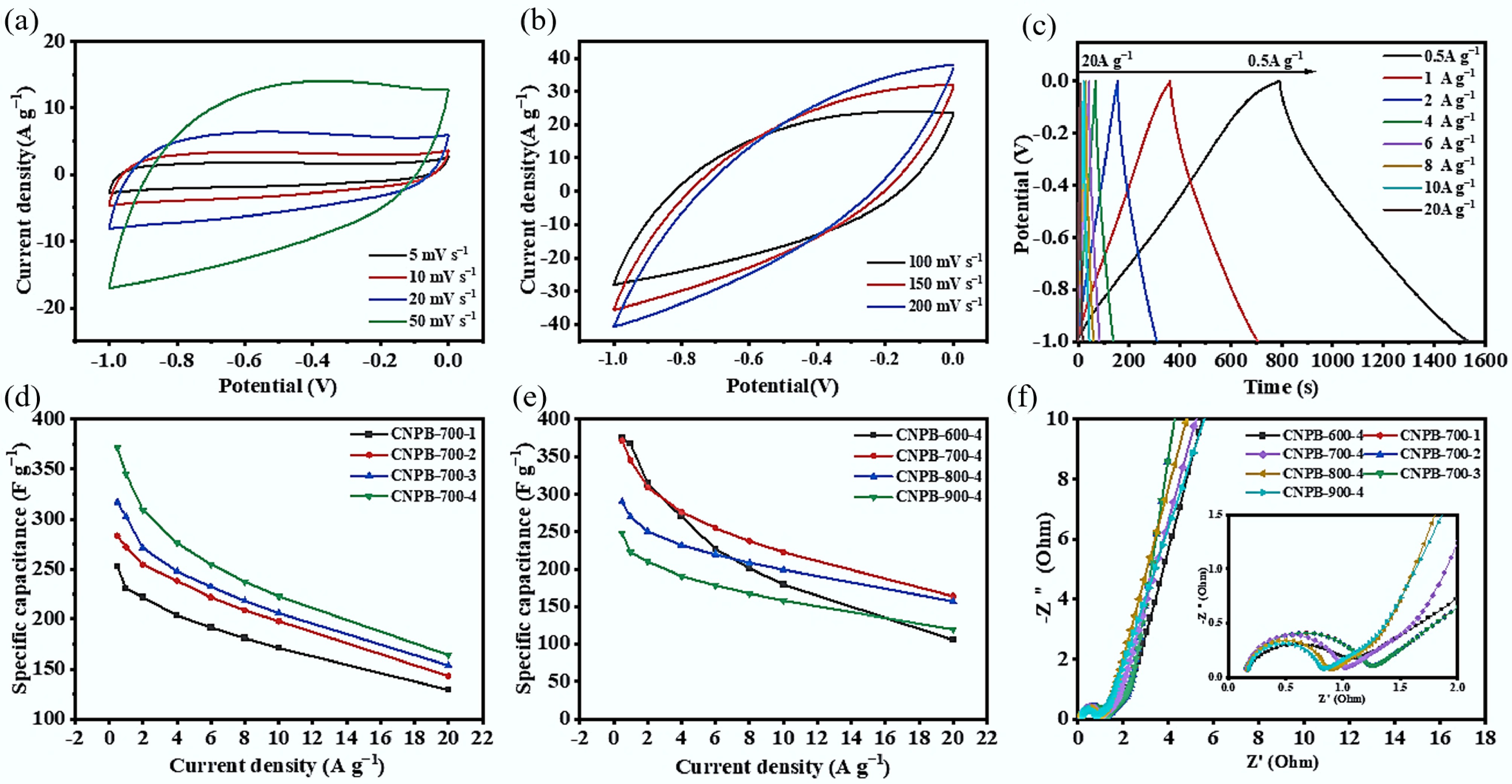

The CV curves of CNPB-700-4 exhibited good storage capacitance performance (Fig. 5a & b) due to the sculpting effect of KOH to form a layered mixed mesoporous and microporous structures. The micropores stored the charge, and the mesopores provided channels for electrolyte diffusion into the micropores[40]. At lower scan rates (Fig. 5a), the higher diffusion of electrolytic charges to the electrode surface resulted in increased diffusion-controlled capacitance. Nevertheless, when the scan rate was elevated from 100 to 200 mV s−1, the CV curve's rectangular and symmetric shape became slightly distorted (Fig. 5b), primarily due to the restricted ion influx in the active electrode material at higher scan rates.

Figure 5.

(a), (b) CV curves of CNPB-700-4 at 5~200 mV s−1; (c) GCD curves of CNPB-700-4 at 0.5~10 A g−1; (d) specific capacitance of different CNPBs prepared at the same activation temperature (700 °C) with different activator ratios; (e) specific capacitance of different CNPBs prepared with the same activator ratio (4:1) at different activation temperatures; (f) impedance profiles of CNPBs.

The charge/discharge behavior of the CNPB-700-4 electrode was tested at current densities ranging from 0.5 to 20 A g−1 (Fig. 5c). Owing to the pseudo-capacitive behavior of functional groups containing N and O in CNPBs, the constant-current charge/discharge curve did not form a perfectly symmetric isosceles triangle. Its excellent reversibility and conductivity made it only slightly distorted. The minimal bending of CNPB-700-4's charging curve (Fig. 5c) at high voltage was due to the increase in potential influencing ion transport[41]. The longer charging and discharging durations at lower current densities were attributed to the relatively adequate time for electrolyte ions to enter and diffuse into the pores of the electrode compared to higher current densities[42]. The specific capacitance at various current densities (shown in Fig. 5d & e) increased with the increase of the KOH ratio, and the specific capacitance of the CNPB-700-4 electrode at 1 A g−1 (344.91 F g−1) was the highest. Even when the current density increased to 20 A g−1, an excellent specific capacitance of 54.21% of the initial value was still maintained, demonstrating the CNPB-700-4 electrode's good rate capability (Fig. 5e).

Electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) ranging from 0.01 to 10,000 Hz were analyzed to investigate the resistances related to the charge storage process (Fig. 5f). The Nyquist curve of CNPB-700-4 showed a steep linear trend at low frequencies and a small semicircle at high frequencies, indicating near-ideal capacitance characteristics and small equivalent series resistance. This performance was credited to the superior intrinsic electronic properties and more efficient ions transportation through the electrode compared with others[40]. The solution resistance (Rs) was derived from the high-frequency intercept of the solid axis (Z') in the Nyquist plot, in which the semicircle indicates the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and the inclined straight line represents the diffusion resistance (Warburg impedance), related to the diffusion and transport of ions from the electrolyte to the surface of the electrode[43,44]. The CNPB-900-4 electrode exhibited the lowest impedance (Fig. 5f), probably because of its well-developed pore structure and high specific surface area. Interestingly, the Rcts values of the Nyquist plots of CNPB-600-4, CNPB-700-4, CNPB-800-4, CNPB-900-4 presented a gradually decreasing trend (0.8703, 0.7858, 0.6576, and 0.5888, respectively). This may be due to the higher graphitization of the pyrolysis samples at high temperatures[39]. The Rs values of CNPB-600-4, CNPB-700-4, CNPB-800-4, and CNPB-900-4 were 0.1199, 0.1475, 0.1603, and 0.1667, respectively. The minor Rct and Rs values indicated that the CNPB electrode materials had low contact resistance, good electrical conductivity, and superior ion transfer properties.

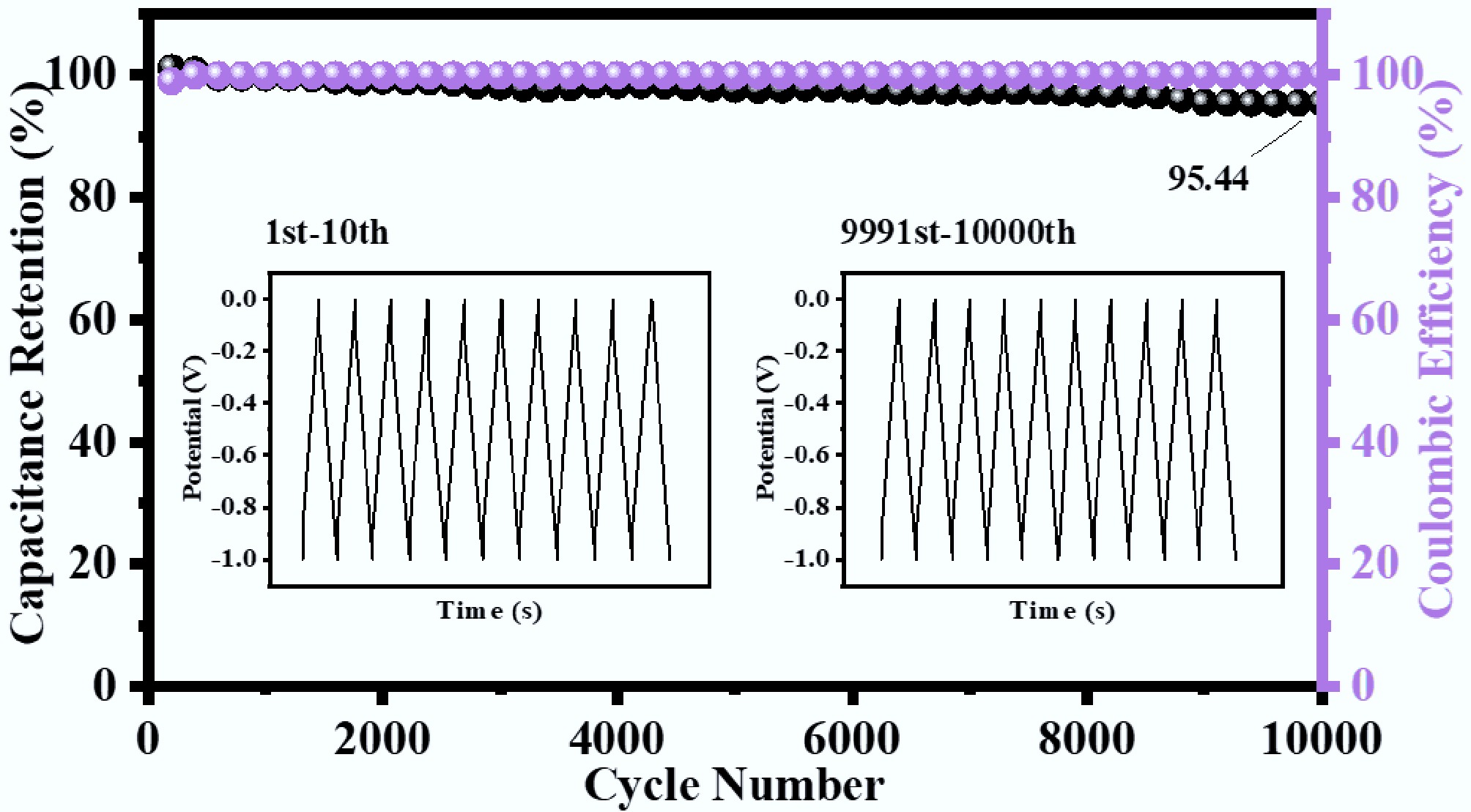

As shown in Fig. 6, CNPB-700-4's capacitance remained at 95.44% of the initial capacitance after 10,000 cycles of constant current charge/discharge at a current density of 10 A g−1. The first five cycles and the 9,996th to 10,000th charge/discharge cycles exhibited extremely similar potential-time response behavior (Fig. 6) and remained as quasi-symmetric triangles, demonstrating that the electrochemical process was quasi-reversible. These results indicate that CNPB-700-4 had good long-cycle performance (> 10,000 cycles), high reversibility, and stable capacitive performance when used as a supercapacitor electrode material.

Figure 6.

Cycling stability and coulomb efficiency plots of CNPB-700-4 in the three-electrode system.

In summary, the outstanding electrochemical performance of CNPB-700-4, including its highest specific capacitance (344.91 F g–1 at 1 A g–1) and remarkable long-term stability (95.44% retention), is directly attributed to the synergistic combination of its unique structural and compositional features. As established in the characterization, these features include its ultra-high specific surface area (2,133.5 m2 g–1), a well-developed hierarchical pore network that ensures efficient ion transport (mesopores) and charge storage (micropores), and the N,O co-doping which enhances conductivity and provides additional pseudo-capacitance.

Symmetric supercapacitor of the two-electrode cell

-

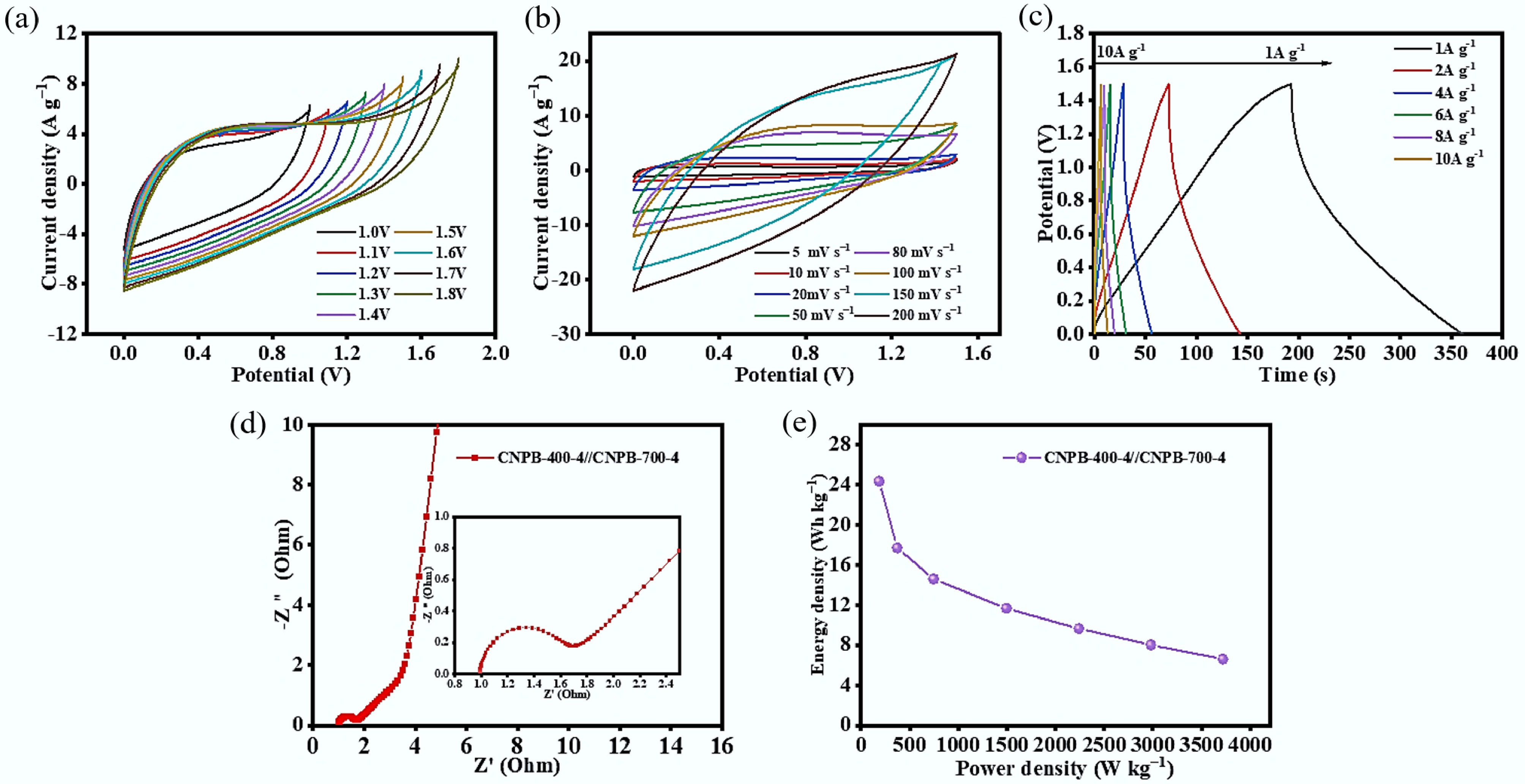

The symmetric CNPB-700-4//CNPB-700-4 electrode was assembled and tested to further estimate the practical use of CNPBs in supercapacitors. Figure 7a shows the CV curves at various voltage windows with a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. In the voltage range of 0~1.5 V, the CV curve remained in an excellent rectangular shape. The CV curve showed a 'sickle' distortion as the voltage window was expanded to 1.6 V, indicating the severe polarization[7]. The symmetric supercapacitor's electrochemical behavior was examined by setting the voltage window to range from 0 to 1.5 V. Figure 7b shows a quasi-rectangular shape and a broad pseudo-capacitance peak of the CV curves in the 0.3–0.5 V range. Even at a high scan rate of 200 mV s−1, the CV curves showed no significant distortion, indicating the device had good double-layer capacitance behavior[12]. As illustrated in the GCD curve of Fig. 7c, the charge/discharge curve of the symmetric supercapacitor also exhibited an approximate triangle with a specific capacitance of 210 F g−1 for CNPB-700-4//CNPB-700-4 at 1 A g−1 and 86.02 F g−1 (when the current density was increased to 10 A g−1). Figure 7e shows that CNPB-700-4//CNPB-700-4 had an ideal reversible double-layer capacitance behavior due to its low internal resistance. Correspondingly, the power density reached up to 373.71 W kg−1 at an energy density of 24.33 Wh kg−1, where all energy and power density values for the symmetric device (Fig. 7e) are normalized by the total mass of the active material on both electrodes. All the above electrochemical properties revealed that CNPB-700-4//CNPB-700-4 symmetric supercapacitor had good rate capability. Compared to other studies, the values found for the specific capacitances of CB derived porous biochars were quite high (210 F g−1 of symmetric supercapacitor) (Table 3), even compared with commercial activated carbon while being tested as a symmetric supercapacitor at 1 A g−1 (e.g., nitrogen-rich microalgae 117 F g−1[45], nitrogen-doped brewer's spent grain 46 F g−1[46], commercial activated carbon 79 F g−1, and nitrogen-rich chicken feather 25 F g−1 [3]).

Figure 7.

Electrochemical performance of CNPB-700-4//CNPB-700-4 symmetric supercapacitor: (a) CV curves for a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 at different voltage windows; (b) CV curves for a scan rate of 5~200 mV s−1 in a 0–1.5 V window; (c) GCD curves for a current density of 1~10 A g−1 in a 0–1.5 V window; (d) impedance profiles; (e) energy-power density Ragone plot.

Table 3. Comparison of SSA and electrochemical properties between CNPB-700-4 and other biomass electrode materials

Biomass electrode

materialsSSA

(m2 g−1)Specific capacitance

(F g−1)Current density

(A g−1)Energy density

(Wh kg−1)Power density

(W kg−1)Cycle stability

(%)Ref. CNPB-700-4 2,133.5 344.91 1 24.33 373.71 95.44/10,000 cycles This work Baby diaper 2,399 353 1 7.22 125 87.65/10,000 cycles [47] Peanut shells 17.8 240 1 4.08 101.3 90/1,200 cycles [48] Platycladus oriental leaves 1,140.2 156 0.5 11 65 96.3/10,000 cycles [49] Buckwheat core 805.91 330 0.5 6.1 250 90/5,000 cycles [50] A further interpretation of Table 3 highlights the balanced competitive advantages of CNPB-700-4. First, its ultra-high SSA (2,133.5 m2 g−1) significantly exceeds that of other biomass sources[49,50]. More importantly, CNPB-700-4 achieves an excellent balance of key metrics: it delivers not only a high energy density (24.33 Wh kg−1) and the highest power density listed (373.71 W kg−1), but also maintains exceptional cycling stability (95.44% over 10,000 cycles). In contrast, other materials listed either suffer from poor stability[47] or much lower energy densities[48−50]. This high, well-rounded performance, achieved from a hazardous waste source, demonstrates its unique application potential.

-

Waste cigarette butts-derived N,O co-doped hierarchical nanoporous biochars (CNPBs) electrode materials were readily prepared by hydrothermal carbonization coupled with pyrolysis activation. Attributed to the combination of high specific surface area, extremely high microporosity, and N/O rich properties, CNPB-700-4 exhibited excellent capacitance capacity, excellent rate capability, and long-term stability, comparable to or better than commercial activated carbon. It had a high storage capacity of 344.91 F g−1 at a current density of 1 A g−1 (210 F g−1 for the symmetric supercapacitor), and after 10,000 cycles of constant current charge/discharge at a current density of 10 A g−1, the capacity remained over 95% of the initial capacitance. The assembled symmetric CNPB-700-4//CNPB-700-4 electrode had an energy density of 24.33 Wh kg−1, and a power density of 373.71 W kg−1, demonstrating a high commercial potential. This work provides a scalable pathway for the large-scale waste valorization of toxic cigarette butts, addressing a significant environmental hazard. The resulting CNPB's high performance, which is comparable to, or even exceeds that of commercial activated carbon, highlights its robust potential for commercial application. This study thus demonstrates a viable circular economy model, upcycling hazardous waste into high-value materials for energy storage.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/een-0025-0016.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Jieni Wang: methodology, conceptualization, data curation, writing−original draft, writing−review and editing; Chenlin Wei: investigation, validation; Haodong Hou: validation, formal analysis; Fangfang Zhang: formal analysis, visualization; Chenxiao Liu: visualization, data curation; Leichang Cao: project administration, conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, resources; Shicheng Zhang: supervision, methodology; Jinglai Zhang: investigation, supervision; James H Clark: resources, writing–review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper. Additional data related to this paper are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

-

The authors are thankful for the support from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M731169), the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security's Research and Selected Funding Project For Overseas Returnees (J24018Y), the Key Scientific Research Projects of Universities in Henan Province (Grant No. 23A610006), the Key Science and Technology Department Project of Henan Province (Grant No. 222102320252), and the Yellow River Scholar Program of Henan University.

-

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

-

CNPB-700-4 exhibited a high capacitance of 344.91 F g−1 in 6 M KOH electrolyte.

Only a 4.56% loss of capacity was observed after 10,000 cycles at 10 A g−1.

The robust performance originated from the developed porosity and rich N/O groups.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang J, Wei C, Hou H, Zhang F, Liu C, et al. 2026. N,O co-doped hierarchical nanoporous biochar derived from waste cigarette butts for high-performance energy-storage application. Energy & Environment Nexus 2: e001 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0016

N,O co-doped hierarchical nanoporous biochar derived from waste cigarette butts for high-performance energy-storage application

- Received: 29 September 2025

- Revised: 10 November 2025

- Accepted: 30 November 2025

- Published online: 13 January 2026

Abstract: There are about 8 million tons of discarded cigarette butts generated annually worldwide. The green and efficient use of them is urgently needed. Cigarette butts are waste cellulose-based materials consisting of the outer packaging (cellulose) and the filter tip (cellulose acetate) that are good candidates to be resourcefully utilized. Herein, N,O co-doped hierarchical nanoporous biochars (CNPBs) with uniform morphology are readily prepared from cigarette butts via hydrothermal carbonization, coupled with pyrolysis activation. The hierarchical pore structure and surface properties of the prepared biochars could be expediently controlled by adjusting the activator ratio and activation temperatures. The optimal CNPB, which has a high specific surface area (2,133.5 m2 g−1), excellent microporosity, and oxygen-rich properties, is obtained at the activation temperature of 700 °C with a potassium hydroxide ratio of 4 (CNPB-700-4). CNPB-700-4 exhibits an energy storage capacity of up to 344.91 F g−1 at a current density of 1 A g−1. After 10,000 constant charge/discharge cycles at a current density of 10 A g−1, the capacity remains at 95.44%. The energy density and power density of the assembled CNPB-700-4//CNPB-700-4 symmetrical supercapacitors are 24.33 Wh kg−1 and 373.71 W kg−1, respectively, demonstrating the high commercial value of the prepared material.

-

Key words:

- Biomass waste /

- N,O co-doping /

- Hierarchical porous biochar /

- Energy storage