-

Salinity stress is a growing global threat to agriculture, impacting an estimated 1,381 million hectares of land, representing 10.7% of the total land area[1]. Agricultural practices, such as overirrigation, the use of reclaimed water, and excessive fertilizer application, have exacerbated this issue, leading to salinity stress in approximately 10%−33% of irrigated farmland worldwide[1−4]. Most crop species are salt-sensitive glycophytes that experience significant yield losses due to the detrimental effects of excessive sodium (Na+) on growth and development[5,6]. In contrast, salt-tolerance halophytes, comprising only 1% of plant species[7], can thrive in Na+ concentrations exceeding 200 mM. Halophytes have evolved diverse strategies to combat salinity, including Na+ compartmentalization within vacuoles (euhalophytes), sequestration in less-sensitive tissues (salt excluders), and active secretion through specialized salt glands (recretohalophytes). Understanding the mechanisms underlying halophyte salt tolerance offers valuable insights for improving crop resilience and restoring salt-affected lands.

Zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.) is a halophyte belonging to the subfamily Chloridoideae of the family Poaceae[8]. It originated from the coastline and islands of the west Pacific and Indian Ocean and was introduced to the US as a lawn grass in 1892[9,10]. Two major species, Z. matrella and Z. japonica, are widely grown as turfgrass in the southern US. Both species are recretohalophytes with active salt glands located on the adaxial surface of leaf blades[11,12]. In Z. matrella and Z. japonica, salt glands are located on the adaxial surface of the leaf blades, arranged in rows between the stomata[12,13]. These glands exhibit a distinctive bicellular structure, featuring a partitioning membrane in the basal cell and a cuticular cavity atop the cap cell, both of which are crucial for salt secretion[13,14]. Research has demonstrated that Z. matrella varieties exhibit greater salt tolerance than Z. japonica varieties, exhibiting lower leaf firing rates, higher leaf and shoot dry weights, and maintaining lower internal Na+ content under salinity stress[9,12,15]. Z. matrella has a higher salt gland density on the leaf surface and can secrete substantially more salt than Z. japonica[12,16]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying salt secretion through salt glands remain poorly understood. In addition to salt secretion, other mechanisms associated with salt tolerance in zoysiagrass have been observed, including Na+ accumulation, sequestration from root stele, and exclusion from root maturation zone[16,17]. This suggests that zoysiagrass incorporates multiple strategies to achieve high salinity tolerance. It is important to note that in vivo experiments using whole plants or runners, as employed in the abovementioned research, may not accurately reflect the stress levels experienced by leaf blade and salt glands because other tolerance mechanisms may act as barriers, preventing Na+ from reaching the salt glands.

The uptake, transport, and secretion of Na+ in plants rely on a variety of transmembrane transporters[18−20], including high-affinity K+ transporters (HKTs) and Na+/H+ antiporters (NHXs). HKTs, located on the plasma membrane, transport Na+ or K+ from the apoplast into the cytoplasm[21,22]. HKTs are classified into two groups based on their sequence phylogeny and ion selectivity. Class I HKTs exclusively transport Na+ and are found in both dicots and monocots, while Class II HKTs are Na+ and K+ symporters and are found only in monocots. Class I HKTs play significant roles in salt tolerance in glycophytes through their involvement in Na+ redistribution processes. For example, AtHKT1;1 in Arabidopsis thaliana and OsHKT1;5 in Oryza sativa are expressed in xylem parenchyma and phloem cells, where they retrieve Na+ from the xylem sap and load it into the phloem for transport to less-sensitive tissues such as roots and leaf sheaths[23−25]. Class II HKTs also contribute to salt tolerance by mediating Na+ uptakes and maintaining K+ and Na+ homeostasis under salt stress.

NHXs represent another important group of Na+ transporters involved in salt stress responses. These transporters transport Na+ or K+ out of the cytosol in exchange for H+. Based on their subcellular localization and transport direction, NHXs are categorized into three groups: (1) Vacuolar NHXs: located on the tonoplast and vacuole membranes, these transporters sequester Na+ into vacuoles, contributing to osmotic adjustment and turgor maintenance for cell expansion and plant growth under saline conditions[26]; (2) Endosomal NHXs: located on endomembrane systems such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, trans-Golgi network (TGN), and prevacuolar compartment (PVC), endosomal NHXs play important roles in intracellular vesicular trafficking, pH regulation, and ion homeostasis[27−29]. They are likely involved in salt secretion[30]; (3) Plasma-membrane NHXs: located on the plasma membrane, these transporters, also known as Salt Overly Sensitive 1 (SOS1), extrude cytosolic Na+ into the apoplast[31]. The SOS1-mediated salt tolerance mechanism is widely conserved across various plant species, including glycophytes and halophytes.

To study salt secretion and the associated gene expression of HKT and endosomal NHX genes in zoysiagrass under varying salinity stress, we developed an in vitro salt secretion assay using leaf blade explants. We selected 'Diamond' (Z. matrella) and 'Meyer' (Z. japonica) as high and low salt-tolerant varieties, respectively, based on prior greenhouse and field evaluations[11,12,32]. We found that both varieties reach maximum salt secretion at 300 mM NaCl. Diamond exhibited significantly higher secretion capacity, consistent with its greater salt tolerance. While HKT1;4 genes were upregulated in both varieties under high salinity conditions (where salt secretion was inhibited), endosomal NHX gene expression was induced by salinity stress only in Diamond. This research provides valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying salt tolerance in zoysiagrass.

-

Zoysiagrass plants (Z. matrella cv. Diamond and Z. japonica cv. Meyer) were maintained in a greenhouse at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Dallas, TX, USA. Rhizomes were transplanted to 4-inch square pots containing potting mix (SunGro, Agawam, MA, USA) and fertilized with 30-10-10 (N-P-K) fertilizer (Miracle-Gro, Marysville, OH, USA). After establishing plants with at least three fully extended leaves, leaf blades were collected and cut into 10-mm-long segments. Segments from a leaf blade were considered as biological replicates. Surface contaminants were removed using nuclease-free water, and the segments were air dried for approximately 30 s. Segments were then immediately placed on 1% agar solidified media with the abaxial leaf surface in contact with the media. The media contains 1X Murashige & Skoog Basal Salt Mixtures with Vitamins (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and supplied with NaCl at the following concentrations: 0, 100, 200, 300, 600, and 1,000 mM. Following incubation at 25 °C with a 16:9 day/night cycle for 12, 24, and 48 h, the leaf segments were removed from the medium for analysis.

Salt secretion capacity was evaluated after 24 and 48 h of salt exposure. Leaf segments were carefully adhered to sticky microscopic slides with the adaxial surface facing upward and fully extended without disturbing. Salt was crystallized on the leaf surface at room temperature and then immediately imaged under a stereo microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) at 10× magnification. To quantify salt secretion, a 'salt index' were calculated for each segment: the area covered by salt crystals (measured using Image J[33]) was divided by the sample area. For each treatment, 9−12 leaf segments were evaluated, and two-tailed t-tests were performed between the two varieties.

Identification of HKTs and NHXs from genome assemblies of Z. matrella and Z. japonica

-

To identify HKT and NHX genes in Z. matrella, we first utilized the genome assembly and annotation of Z. matrella cv Diamond. These sequences were then used as queries in BLASTp searches against the Zoysia Genome Database[34] to identify homologous genes in Z. japonica cv. Nagirizaki (r1.1). For comparative analysis, we also retrieved HKT and NHX sequences from Oryza sativa Japonica Group (IRGSP-1.0) via Ensembl Plants, ensuring completeness by cross-referencing with the genome annotation. Further, HKT genes from Triticum aestivum (wheat) and NHX genes from Zea mays (maize) were included in the analysis, based on data from previous studies[35,36]. To validate the function of the identified genes, we performed protein domain analysis using InterProScan[37]. HKT candidates were confirmed based on the presence of the 'Cation transporter' (IPR003445) or 'TrkH Potassium Transport' (IPR051143) protein family memberships, and the 'monoatomic cation transmembrane transporter activity' (GO:0008324) Gene Ontology term. Similarly, NHX candidates were validated through the presence of the 'Cation/H+ exchanger, CPA1 family' (IPR018422) protein family membership and the 'antiporter activity' (GO:0015297) GO term. Phylogenic analysis of HKT and NHX genes was performed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA-11)[38]. TBtools-II[39] was used to investigate the syntenic relationships of NHX and HKT genes between Z. matrella and O. sativa genome assemblies.

RNA extraction and gene expression analysis

-

We used quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) to quantify HKT gene expression in the leaf blade of zoysiagrass, including 2 HKT1;3 (ZmdHKT1;3-A and B), 2 HKT1;4 (ZmdHKT1;4-A and B), 1 HKT2;1 (ZmdHKT2;1), 2 HKT2;2 (ZmdHKT2;2-A and B), and 1 HKT2;4 (ZmdHKT2;4) from Z. matrella and 2 HKT1;4 (ZjnHKT1;4-A and B), 1 HKT2;1 (ZjnHKT2;1), 1 HKT2;2 (ZjnHKT2;2), and 1 HKT2;4 (ZjnHKT2;4) from Z. japonica. Vascular NHX genes, including 1 NHX5 (ZmdNHX5), and 2 NHX6 (ZmdNHX6-A and B) from Z. matrella, and 1 NHX6 (ZjnNHX6) from Z. japonica, were also analyzed. The extra leaf segments used in the in vitro salt secretion assay were harvested at 12, 24, and 48 h after salt treatment and used for total RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Leaf segments were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and cryoground into a fine powder using a HG-600 Geno/Grinder (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) at 1,750 strokes per minute for three cycles of one minute each. RNA was further purified using the Quick RNA Miniprep Kit (ZYMO Research, Irving, CA, USA), including on-column DNase I (ZYMO) digestion to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The cDNA synthesis was performed with the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting cDNA was diluted 1:1 with water and used for qRT-PCR analysis with an Applied Biosystems StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The qRT-PCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with the following cycling conditions: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min, and a final melt curve analysis from 60−95 °C to confirm amplification specificity. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer 3[40] based on coding DNA sequences and validated by PCR (Supplementary Table S1). Three biological replications were incorporated for each treatment, and each contained three technical replications. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔCᴛ method[41] with a putative zoysia polyubiquitin gene serving as an internal reference control (Supplementary Table S1). Samples treated with 0 mM NaCl were used as the control group. Statistical analysis, including ANOVA and multiple comparison tests with Tukey HSD adjustment under each NaCl concentration, was conducted using R software.

-

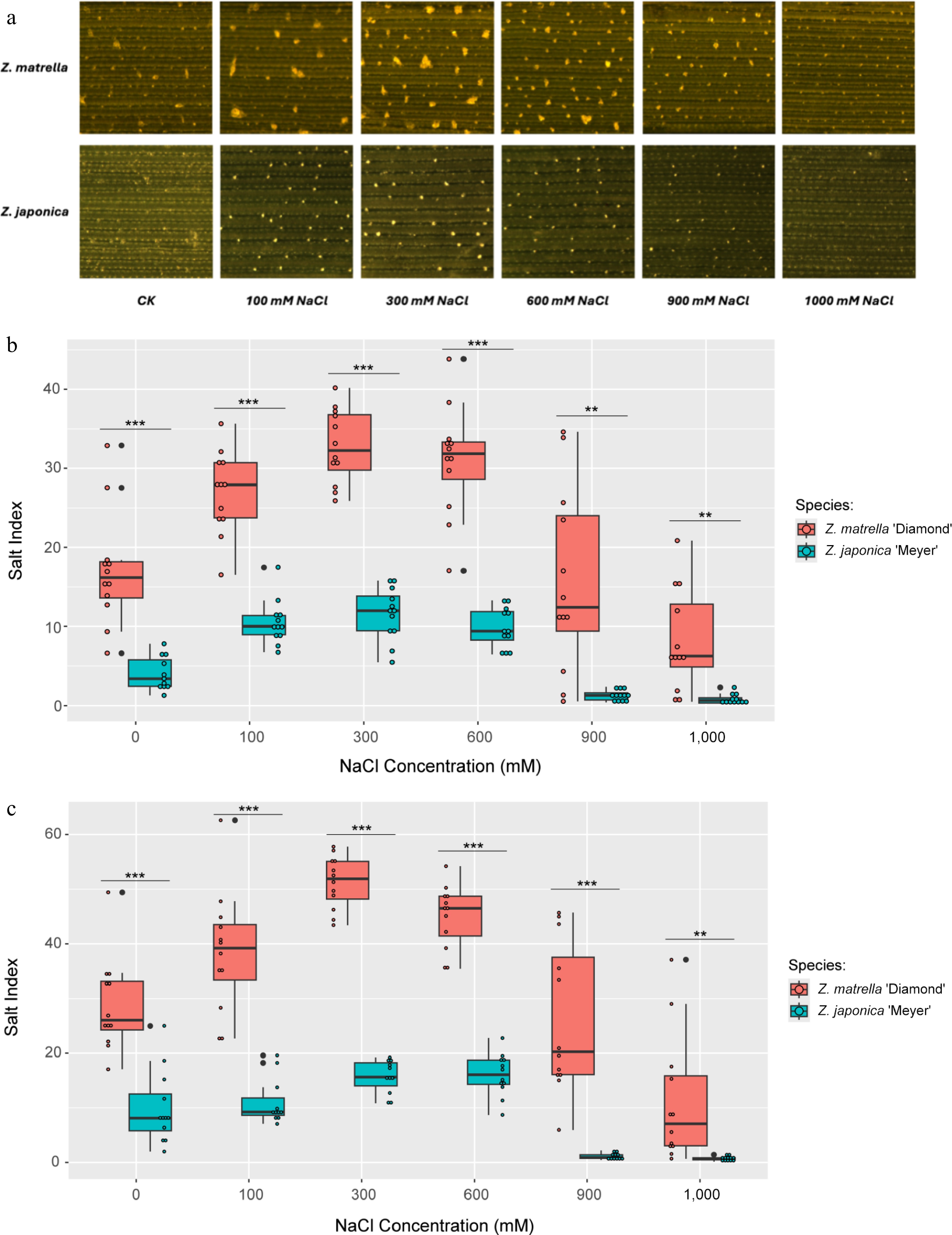

In vitro salt secretion assays revealed sustained salt secretion in both Z. matrella and Z. japonica for at least 48 h. Liquid droplets, containing secreted salts, appeared on the adaxial leaf surfaces of both species, with Z. matrella exhibiting visible droplets as early as 2 h after exposure, while Z. japonica showed droplets at 12 h. Salt crystallization from these droplets was observed at both 24 and 48 h (Fig. 1a). Control samples treated without Na+ also exhibited a few salt crystals secreted, likely due to the continuation of secretion of pre-existing internal Na+ before the experiment.

Figure 1.

Salt secretion in Z. matrella and Z. japonica under in vitro conditions with ambient NaCl. (a) Adaxial leaf surface after 24 h of salt treatment, illustrating the quantity of salt secreted. Boxplots comparing salt secretion rates per unit area for the two species measured at (b) 24 h, and (c) 48 h of salt treatment. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Salt secretion rates measured at 24 and 48 h after treatments exhibited similar patterns across the different levels of NaCl treatment. Measurements collected at both 24 and 48 h after treatments showed the rate of salt secretion in both species increased with salinity levels from 0 to 300 mM NaCl, reaching a maximum rate between 300 and 600 mM. This suggests that the salt glands in both species have similar sensitivities to salinity stress and that Na+ levels become excessive at 600 mM. Above 600 mM, secretion rates declined dramatically in both species, with Z. japonica showing almost complete inhibition at or above 900 mM. However, Z. matrella maintained a low level of secretion even at the highest salinity level (1,000 mM) (Fig. 1b, c). Throughout the salinity range tested, Z. matrella consistently exhibited a significantly higher salt secretion rate than Z. japonica.

HKT and NHX genes in Z. matrella and Z. japonica

-

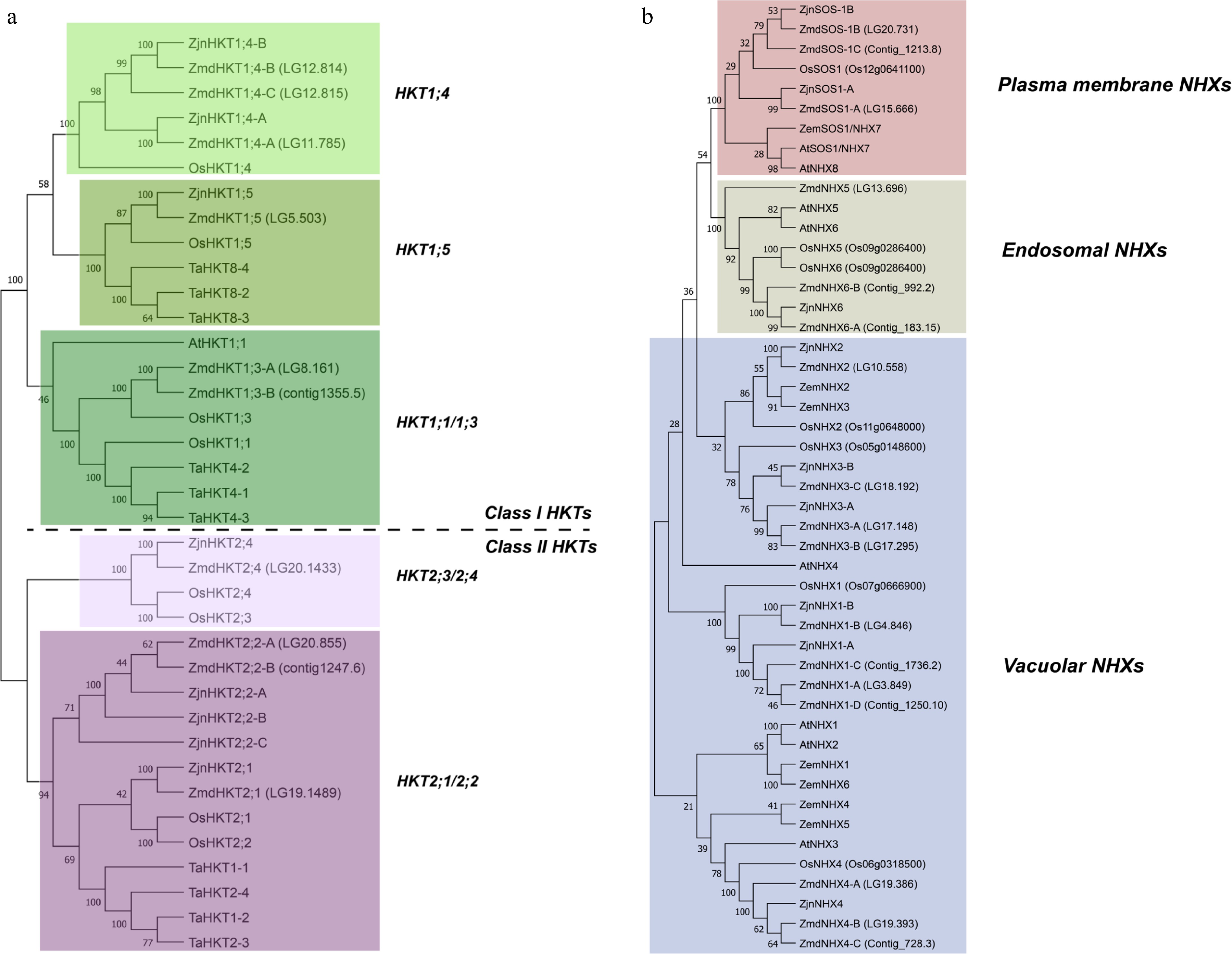

The Z. matrella cv. Diamond genome harbors 10 potential HKT genes distributed across chromosomes LG5, LG8, LG11, LG12, LG19, and LG20, as well as two unanchored contigs (Contig1247 and Contig1355). A tandem duplication of the HKT1;4 gene was identified on chromosome LG12. In contrast, the Z. japonica genome contains eight potential HKT genes, including tandem duplications of HKT2;1/2;2. Phylogenetic analysis of 37 HKT genes from four monocot species and Arabidopsis thaliana clearly distinguishes Class I and Class II HKTs. Following the established nomenclature system for HKTs[42] and considering the rice genome's resemblance to the ancestral form of the grass genome[43,44], we assigned names to the zoysiagrass HKT genes based on sequence homology with OsHKT genes. A letter identifier was added to differentiate genes within the same group. This resulted in the designation of 2 HKT1;3 (ZmdHKT1;3-A and B), 3 HKT1;4 (ZmdHKT1;3-A, B, and C), 1 HKT1;5 (ZmdHKT1;5), 3 HKT2;1 (ZmdHKT2;1-A, B, and C), and 1 HKT2;4 (ZmdHKT2;4) in Z. matrella, and 2 HKT1;4 (ZjnHKT1;4-A and B), 1 HKT1;5 (ZjnHKT1;5), 1 HKT2;4 (ZjnHKT2;4), and 4 HKT2;1 (ZjnHKT2;1-A, B, C, and D) in Z. japonica (Table 1, Fig. 2a).

Table 1. Summary of HKT and NHX genes in Zoysia matrella and Zoysia japonica.

Transporter Species Gene ID Gene name Type Chr/contig Start End Protein High-affinity K+ transporters (HKTs) Zoysia matrella evm.TU.chrLG5.503 ZmdHKT1;5 Class I HKT LG5 1E+07 1E+07 399 evm.TU.chrLG8.161 ZmdHKT1;3-A LG8 1E+06 1E+06 694 evm.TU.chrLG11.785 ZmdHKT1;4-A LG11 2E+07 2E+07 856 evm.TU.chrLG12.814 ZmdHKT1;4-B LG12 1E+07 1E+07 966 evm.TU.chrLG12.815 ZmdHKT1;4-C LG12 1E+07 1E+07 613 evm.TU.contig_1355.5 ZmdHKT1;3-B Contig1355 47032 60625 1369 evm.TU.chrLG19.1489 ZmdHKT2;1 Class II HKT LG19 3E+07 3E+07 447 evm.TU.chrLG20.855 ZmdHKT2;2-A LG20 2E+07 2E+07 541/4871 evm.TU.chrLG20.1433 ZmdHKT2;4 LG20 2E+07 2E+07 519 evm.TU.contig_1247.6 ZmdHKT2;2-B Contig1247 40514 42319 541 Zoysia japonica Zjn_sc00004.1.g09630 ZjnHKT1;4-A Class I HKT Zjn_sc00004.1 420993 4E+06 925 Zjn_sc00011.1.g08720 ZjnHKT1;5 Zjn_sc00011.1 5E+06 5E+06 479 Zjn_sc00023.1.g02580 ZjnHKT1;4-B Zjn_sc00023.1 1E+06 1E+06 672 Zjn_sc00008.1.g01340 ZjnHKT2;4 Class II HKT Zjn_sc00008.1 560759 566679 876 Zjn_sc00068.1.g02380 ZjnHKT2;1 Zjn_sc00068.1 1E+06 1E+06 420 Zjn_sc00068.1.g02390 ZjnHKT2;2-C Zjn_sc00068.1 1E+06 1E+06 253 Zjn_sc00107.1.g01070 ZjnHKT2;2-A Zjn_sc00107.1 564336 566416 436 Zjn_sc00107.1.g01080 ZjnHKT2;2-B Zjn_sc00107.1 570341 571277 290 Na+/K+ antiporters (NHXs) Zoysia matrella evm.TU.chrLG13.696 ZmdNHX5 Endosomal NHX LG13 2E+07 2E+07 265 evm.TU.contig_183.15 ZmdNHX6-A Contig183 324272 333257 553 evm.TU.contig_992.2 ZmdNHX6-B Contig992 27765 37237 530 evm.TU.chrLG15.666 ZmdSOS1-A Plasma membrane NHX LG15 1E+07 1E+07 1144/10461 evm.TU.chrLG20.731 ZmdSOS1-B LG20 1E+07 1E+07 1154/10571 evm.TU.contig_1213.8 ZmdSOS1-C Contig1213 59774 68887 975 evm.TU.chrLG3.849 ZmdNHX1-A Vacuolar NHX LG3 2E+07 2E+07 540/3911 evm.TU.chrLG4.846 ZmdNHX1-B LG4 2E+07 2E+07 429/4013 evm.TU.chrLG10.558 ZmdNHX2 LG10 1E+07 1E+07 544 evm.TU.chrLG17.148 ZmdNHX3-A LG17 2E+06 2E+06 811 evm.TU.chrLG17.295 ZmdNHX3-B LG17 6E+06 6E+06 392 evm.TU.chrLG18.192 ZmdNHX3-C LG18 2E+06 2E+06 583 evm.TU.chrLG19.386 ZmdNHX4-A LG19 9E+06 9E+06 440 evm.TU.chrLG19.393 ZmdNHX4-B LG19 9E+06 9E+06 523 evm.TU.contig_738.3 ZmdNHX4-C Contig738 15126 19095 524/448/395/4444 evm.TU.contig_1250.10 ZmdNHX1-D Contig1250 58727 63951 540/391/4582 evm.TU.contig_1736.2 ZmdNHX1-C Contig1736 7 4443 429 Zoysia japonica Zjn_sc00085.1.g00950 ZjnNHX6 Endosomal NHX Zjn_sc00085.1 966404 976204 634 Zjn_sc00035.1.g02750 ZjnSOS1-B Plasma membrane NHX Zjn_sc00035.1 3E+06 3E+06 1057 Zjn_sc00105.1.g00050 ZjnSOS1-A Zjn_sc00105.1 32266 47024 1073 Zjn_sc00001.1.g01510 ZjnNHX-1A Vacuolar NHX Zjn_sc00001.1 634926 639121 540 Zjn_sc00016.1.g04350 ZjnNHX3-B Zjn_sc00016.1 3E+06 3E+06 525 Zjn_sc00044.1.g04210 ZjnNHX1-B Zjn_sc00044.1 2E+06 2E+06 546 Zjn_sc00096.1.g00980 ZjnNHX2 Zjn_sc00096.1 445565 450176 452 Zjn_sc00146.1.g00380 ZjnNHX4 Zjn_sc00146.1 294475 297777 245 Zjn_sc00166.1.g00230 ZjnNHX3-A Zjn_sc00166.1 148408 157386 507 1Two isoforms; 2three isoforms; 3five isoforms: one isoform of 429 aa and four isoforms of 401 aa; 4six isoforms: three isoforms of 395 aa, one isoform of 528 aa, one isoform of 448 aa, one isoform of 444 aa.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of (a) HKT, and (b) NHX gene families. Protein sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE alignment tool, and Neighbor-Joining (NJ) phylogenetic trees were constructed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA-11 software. The sequences used in the analysis are listed in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3. Species abbreviations: Zmd, Zoysia matrella cv Diamond; Zjn, Zoysia japonica cv Nagirizaki; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Os, Oryza sativa; Ta, Triticum aestivum; Zem, Zea mays.

Sixteen potential NHXs were identified in Z. matrella, located on chromosomes LG3, LG4, LG10, LG13, LG15, LG17, LG18, LG19, and LG20, and five unanchored contigs. Z. japonica has nine NHX genes. Phylogenetic analysis of NHXs revealed two monophyletic sister groups: plasma membrane (SOS1) and endosome NHXs. The majority of the remaining NHXs are paraphyletic vacuolar NHXs. Based on sequence homology, we identified three and two plasma membrane NHXs, three and one endosomal NHXs, and 11 and seven vacuolar NHXs in Z. matrella and Z. japonica, respectively (Fig. 2b). Similar to the HKTs, we adopted a nomenclature system for the NHX genes based on sequence homology to OsNHX genes (Table 1).

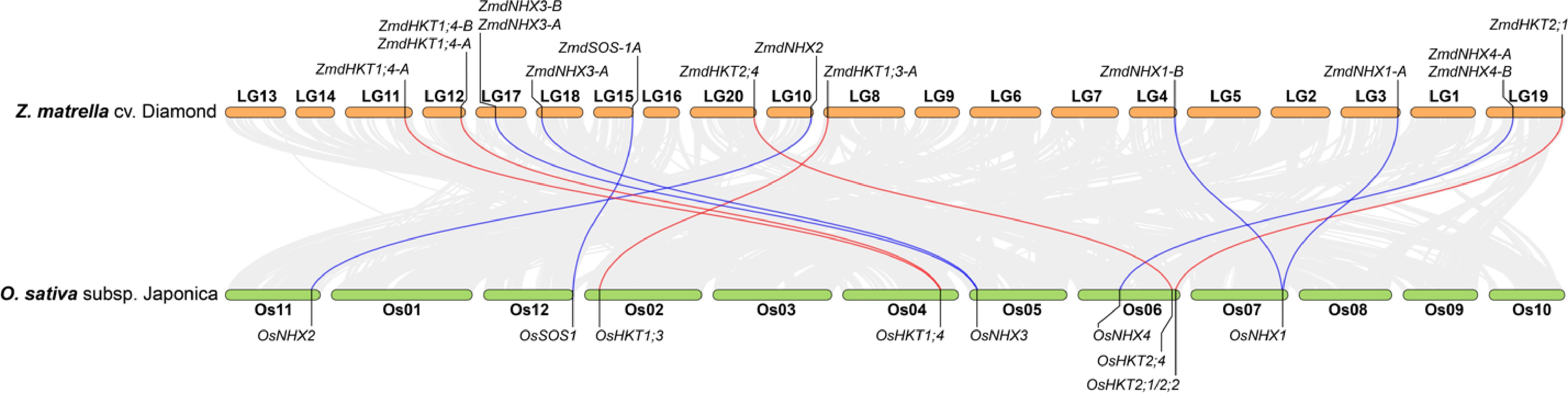

Z. matrella is an allotetraploid species with 2n = 4x = 40 chromosomes[45]. Following the genome duplication event, the duplicated genes are not equally retained throughout the genome, and this process is accompanied by significant chromosomal rearrangements, leading to a restructured genome where the duplicated genes are not always located in the same positions as the original copies. Genome synteny comparisons between Z. matrella and rice revealed collinearity of some HKT and NHX genes (Fig. 3). While duplicated copies of HKT1;4, NHX1, and NHX3[44] are conserved, only one copy of HKT2;1, HKT2;4, NHX2, NHX4, and SOS1 has been retained. In some instances, collinearity is less clear, such as ZmdHKT1;5 on LG5 and OsHKT1;5 on chromosome Os01. Additionally, ZmdNHX5 lacks a rice counterpart on Os08, suggesting chromosomal rearrangements and potential subfunctionalization after the genome duplication event.

Figure 3.

Genome collinearity analysis between Z. matrella cv. Diamond and O. sativa subsp. japonica, highlighting the relationships of HKT and NHX genes between the two species. Genes located on unanchored contigs in Z. matrella were excluded from the analysis.

Expression dynamics of HKTs and NHXs in Z. matrella and Z. japonica under different salinity stress levels

-

qRT-PCR analysis revealed that HKT1;4 genes were the most highly expressed HKTs in leaf blades of both Z. japonica and Z. matrella. In contrast, expression of class II HKTs in the leaf blades was much lower (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. S1). Both species exhibited similar HKT1;4 expression patterns in response to salinity stress at various time points (Fig. 4a, b, e, & f). At 12 h, HKT1;4 genes were expressed at significantly lower levels in leaf segments treated with 0 and 300 mM NaCl than in those treated with 600 and 1,000 mM NaCl. These differences were also observed at 24 and 48 h. The HKT2;4 is the highest expressed class II HKT gene in leaf blades of both species and showed similar expression patterns in response to salinity stress in both species. At 12 h, the expression levels of HKT2;4 were upregulated with the increasing NaCl concentration. However, at 24 and 48 h, the difference between treatments became less significant.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of relative expression levels of HKT and NHX genes in zoysia leaf blades under in vitro conditions treated with varying NaCl concentrations. (a)–(d) Expression profiles of Z. matrella genes: ZmdHKT1;4-A, ZmdHKT1;4-B, ZmdHKT2;4, and ZmdNHX6-D. (e), (f) Expression profiles of Z. japonica genes: ZjnHKT1;4-A, ZjnHKT1;4-B, ZjnHKT2;4, and ZjnNHX6. Statistical differences among NaCl treatments were analyzed using Tukey's HSD test (p < 0.05).

Gene expression analysis of endosomal NHX genes revealed distinct responses between the two species. Z. matrella possessed three endosomal NHX genes with similar expression dynamics (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. S1e & f), exhibiting an overall upregulation with increasing salinity stress. At 12 h, no significant difference in expression was observed between 0 and 300 mM treatment groups, and between 600 and 1,000 mM treatment groups. At 24 and 48 h, the gene expression showed gradually increased expression levels with increasing stress levels. In contrast, Z. japonica showed no significant differences in endosomal NHX gene expression between different salinity stress treatments (Fig. 4h).

-

The Poaceae family exhibits a wide range of salinity tolerance across species. While salt gland-like structures are present in most species (with the exception of Pooideae), only 15 species within the Chloridoideae subfamily have demonstrated active salt excretion[14,46]. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying salt secretion could enable the reintroduction or enhancement of this trait in grasses that have lost this ability, thereby improving their tolerance to saline environments and bolstering their resilience to salt stress.

Zoysiagrass employs multiple strategies to achieve high salinity tolerance, among which salt secretion is considered a primary mechanism. Traditional in vivo experiments, such as growing plants hydroponically or in potting mix with added salt, have been widely used to evaluate salt tolerance in zoysiagrass[12,15,17]. However, these methods have limitations when studying salt secretion. While they mimic field conditions, they do not directly expose salt glands to salinity stress. Instead, salt must first be absorbed by the roots and transported through the plant, with only a fraction ultimately reaching the salt glands for secretion. During this process, Na+ can gradually accumulate in shoots, as observed in Z. matrella and Z. japonica under hydroponic salinity stress[47]. In contrast, in vitro leaf assays offer a more direct and efficient approach to assessing salt secretion. By directly exposing leaf explants to salt, Na+ rapidly reaches the cells via diffusion, enabling a precise and efficient measurement of salt secretion. This direct method offers a valuable tool for rapidly assessing salt secretion capacity, which is particularly useful in breeding programs aiming to enhance salinity tolerance.

Previous studies in Z. japonica have demonstrated a direct correlation between salt tolerance and the amount of Na+ secreted through salt glands[17]. However, the relationship between gland density and secretion capacity is not always straightforward[12,16]. For instance, Z. japonica, despite having a lower salt gland density than Z. matrella, doesn't necessarily translate to reduced salt secretion[12,16]. This highlights the need to investigate whether salt glands from different species and varieties respond similarly to salinity stress. Our study revealed distinct differences in salt secretion capacity between Z. japonica and Z. matrella. Z. matrella consistently exhibited a higher salt secretion rate than Z. japonica. In both species, salt secretion increased in response to increasing salinity stress, reaching a peak at 300 mM NaCl. Beyond this concentration, further increases in salinity did not significantly enhance secretion, indicating that the salt glands had reached their maximum capacity. Interestingly, at 900 mM NaCl and above, salt secretion was completely inhibited in Z. japonica, whereas Z. matrella maintained a low but measurable level of secretion. These findings suggest that different capacities for salt secretion between the two species contribute to their differing response to extreme saline conditions.

Salt tolerance mechanism and the role of HKTs and endosomal NHXs in zoysiagrass

-

To date, the salt secretion mechanism remains largely unknown. Recent proposed models[14,30,46] suggest that basal cells within salt glands take up Na+ from surrounding mesophyll cells and apoplast, potentially through plasmodesmata, and concentrate them in intracellular vesicles. These vesicles are then transported to cap cells for secretion into the atmosphere via exocytosis. Sodium transporters like HKTs, non-selective cation channels (NSCCs), cyclic-nucleotide-gated cation channels (CNGCs), and endosomal NHXs are likely involved in this process. In addition to salt secretion, zoysiagrass also employs other strategies for salt tolerance, including sequestration of Na+ in vacuoles, increased potassium (K+) uptake, and compartmentalization of Na+ in less sensitive tissues[17]. Transporters such as HKTs and NHXs also play important roles in these processes.

Zoysiagrass is an allotetraploid species and rice serves as a suitable reference for comparative analysis due to its conserved genome structure of the grass ancestor[43,44]. Comparative genomic analysis between zoysiagrass and rice revealed post-polyploidization genome rearrangements, including differential retention and translocation of HKT and NHX genes. We identified HKT and NHX gene families in Z. matrella and Z. japonica and detected gene duplications derived from whole-genome duplication and tandem duplication events. While the number of HKT genes are comparable across species (Z. matrella: 10, Z. japonica: eight, O. sativa: eight), zoysiagrass possess significantly more NHX genes (Z. matrella: 17, Z. japonica: nine, O. sativa: six), suggesting an expansion of this gene family in zoysiagrass. Such gene duplications provide the raw material for the evolution of novel gene functions, which may contribute to the enhanced salt tolerance of zoysiagrass. Our gene expression analysis, coupled with in vitro salt secretion assays, provided intriguing insights. Only HKT1;4 genes were highly expressed in zoysiagrass leaf blades, and their expression levels were upregulated under high salinity conditions, such as 600 mM (12 h) and 1,000 mM (24, 48 h) (Fig. 4). This regulation, however, showed a negative correlation with salt secretion observed under the same experiment conditions. This suggests that HKT1;4 transporters in zoysiagrass may play roles in multiple pathways in salinity stress response and potentially contribute to Na+ accumulation or compartmentation. These pathways may serve as alternative pathways and only be activated when salt secretion is impaired under extreme saline conditions.

Previous studies showed overexpression of endosomal NHXs increased salt tolerance in glycophytes like A. thaliana, which lack salt secretion capacities[28,48]. Our study showed a significant increase in the expression of the endosomal NHX gene in Z. matrella, particularly at high salinity levels when salt secretion is impaired. In contrast, such significant upregulation of the endosomal NHX gene was not observed in Z. japonica. This differential expression pattern suggests that increased Na+ sequestration within the endomembrane system may be a pronounced salt tolerance strategy in Z. matrella under high salinity. The contrasting expression patterns of endosomal NHX genes likely contribute to the observed differences in salt tolerance between these two Zoysia species. Future research should focus on fully elucidating the precise functional roles of these transporters in the comprehensive salt tolerance mechanisms of zoysiagrass.

-

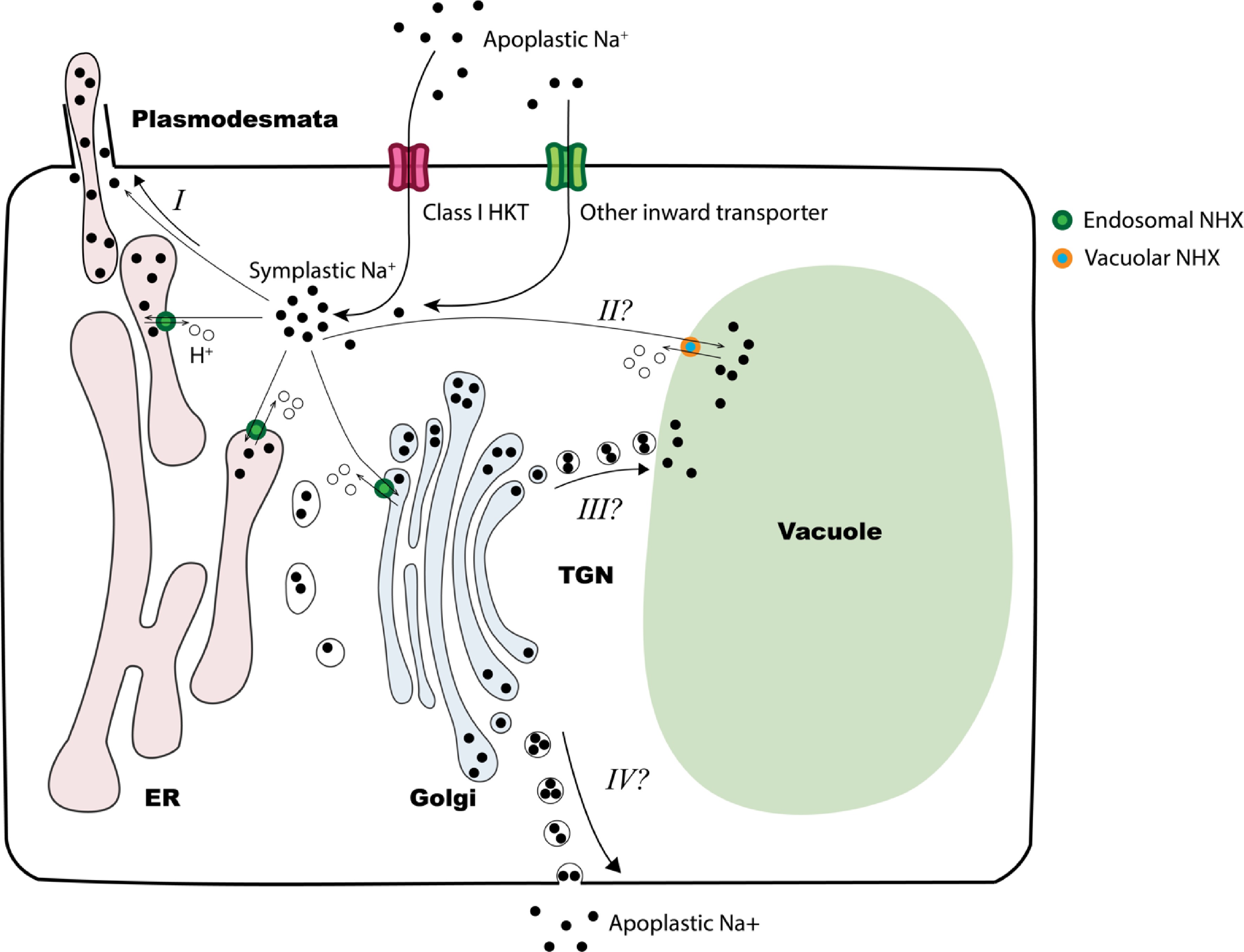

To isolate salt secretion from other salt tolerant mechanisms and efficiently evaluate salt secretion capacity across germplasm accessions, we developed an in vitro salt secretion assay. Using this assay, we compared salt secretion in Z. matrella and Z. japonica. Our study revealed that Z. matrella consistently exhibited a higher salt secretion rate than Z. japonica. Salt glands in both species exhibited similar levels of sensitivity to salinity stress, with their secretion peaking at 300 mM NaCl. Based on our findings, we propose an updated model for salt secretion in zoysiagrass (Fig. 5), expanding on the model by Lu et al.[30]. Under low salinity stress (internal Na+ < 300 mM), Na+ is transported to leaf blades and secreted by salt glands. Under higher salinity stress, HKT1;4 is upregulated, which intercepts Na+ from the tapoplast for storage or loading into the vascular system (not shown in the figure). In Z. matrella, the upregulation of endosomal NHXs facilitates the loading of excess Na+ into the endomembrane system. This sequestered Na+ could then be directed to several potential destinations: salt glands (I), vacuoles (II), or even excreted back into the apoplast (III).

Figure 5.

Proposed model of zoysiagrass response to salinity. Under salinity stress, apoplastic Na+ enters leaf cell through class I HKT transporters or other inward transporters. At high salinity stress levels, the cytosol may act as a temporary sink for Na+. The accumulated Na+ can be loaded to vascular system (not depicted in the figure), transported into endomembrane system via endosomal NHX transporters, or sequestered into the vacuole by vacuolar NHXs (option II). Excess Na+ within endomembrane system may be transported to salt glands via plasmodesmata (option I), to the vacuole (option III) or excreted back into the apoplast (option IV). In Z. matrella, the upregulation of endosomal NHXs under high levels of salinity stress suggests that options III and IV may serve as alternative responses to salt stress.

We sincerely thank the following personnel for their valuable assistance: Jinping Zhao, Dongshen Yao, and Junqi Song from Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Dallas; Craig Schluttenhofer and Marcus Nagle from the Central State University for technical support. This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) – Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI) (Grant No. 2019-51181-30472) to Yu Q and Ambika Chandra.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: research activities coordinating: Yu Q; experiments design: Yu Q, Zhao Z; experiments conducting and data analysis: Zhao Z, Lyu H, Xu Y, Wang F; plant materials providing: Chandra A; draft the manuscript: Zhao Z; manuscript revision: Yu Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 qRT-PCR primers for Zoysia matrella and Zoysia japonica HKT and NHX genes.

- Supplementary Table S2 HKT genes and their GenBank accession numbers from three other species used for phylogenic analysis in Fig. 2a.

- Supplementary Table S3 NHX genes and their GenBank accession numbers from three other species used for phylogenic analysis in Fig. 2b.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Dynamics of relative expression levels of HKT and NHX genes in zoysiagrass leaf blades under in vitro conditions treated with varying NaCl concentrations.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao Z, Lyu H, Xu Y, Wang F, Chandra A, et al. 2025. In vitro assessment of salt secretion and its correlation with transporter gene expression in zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.). Grass Research 5: e026 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0023

In vitro assessment of salt secretion and its correlation with transporter gene expression in zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.)

- Received: 02 March 2025

- Revised: 14 July 2025

- Accepted: 11 August 2025

- Published online: 28 October 2025

Abstract: Soil salinity is a major threat to global agriculture. The recretohalophytic turfgrass species Zoysia matrella (L.) Merr. and Zoysia japonica Steud. possess unique salt glands that enable them to secrete excess salt. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying salt secretion could enable the introduction of salt secretion in other grasses, thereby improving their salt tolerance. In this study, we developed an in vitro leaf assay to investigate salt secretion patterns and the expression of key sodium/potassium transporters, including HKTs and endosomal NHXs. The present study revealed that Z. matrella consistently exhibited a higher salt secretion rate than Z. japonica. In both species, salt secretion increased with rising salinity, peaking at 300 mM NaCl. Beyond this threshold, further increases in salinity did not significantly enhance secretion, suggesting a maximum capacity for the salt glands. Interestingly, at 900 mM NaCl, salt secretion was completely inhibited in Z. japonica, whereas Z. matrella maintained a low level of secretion. Among the HKT genes, HKT1;4 was the most highly expressed in the leaves of both species, and its expression was negatively correlated with salt secretion. Additionally, NHX6 expression in Z. matrella was negatively associated with secretion, a pattern not observed in Z. japonica. The contrasting expression patterns of endosomal NHX genes may contribute to the differential salt tolerance between the two species. The in vitro leaf assay developed in this study provides an efficient tool for evaluating salt secretion in breeding programs. The present findings offer valuable insights into salt secretion and tolerance mechanisms in zoysiagrass, paving the way for the development of new salt-tolerant varieties.

-

Key words:

- Zoysiagrass /

- Zoysia /

- Salt secretion /

- Salt tolerance /

- In vitro salt secretion assay /

- HKT transporters /

- NHX transporters