-

Turfgrasses are a select group of grasses used for ground cover on different applications, including athletic fields, landscapes, golf courses, and home lawns. In the past decades, regulatory policies pushing for water conservation have driven increased efforts to improve drought resistance in turfgrass species, enabling the maintenance of turfgrass quality under lower irrigation[1,2]. While new cultivars with improved drought resistance have been recently released[3−6], further investigations are required to enhance our understanding of drought resistance mechanisms and best methods for selection in turfgrasses.

Zoysiagrasses are warm-season grasses (C4 photosynthesis) widely used in the US[7], especially in the South and the transition zone[8,9]. They are well-adapted for a number of uses (including home lawns, commercial landscapes, and golf courses), and exhibit highly desirable traits, such as superior turfgrass quality, good competitiveness against weeds, lower input needs, and higher cold tolerance than other warm-season grasses[7,9,10]. However, zoysiagrasses require higher amounts of water and have greater drought susceptibility than other warm-season grasses, such as bermudagrass and buffalograss[11−15]. Therefore, improving drought resistance of zoysiagrass is of critical importance for reducing the irrigation needs of these plants while maintaining turfgrass quality and survival[8,9].

Previous studies on zoysiagrass demonstrate a large variation in drought resistance across genotypes and cultivars[10,14,16−18]. In these studies, drought resistance was assessed through survival rate and aesthetic traits upon various levels of irrigation deficit. However, very few studies have thoroughly examined the mechanisms contributing to drought resistance in zoysiagrasses (however, see Jesperson & Schwartz and Hong & Bremer for example research[16,18]). Drought resistance is a complex trait that can be brought about by escape (i.e., inducing dormancy upon dry spells), avoidance (i.e., minimizing plant dehydration during soil drought), and tolerance (i.e., maintaining cell viability and function stability upon tissue dehydration)[19].

While differences in drought avoidance and tolerance were observed across experimental breeding lines and commercial cultivars of zoysiagrass[16,20], differences in drought tolerance alone were shown to dictate resistance among other commercial cultivars[18]. The study of Simpson et al.[18] investigated the drought resistance mechanisms of four commercial cultivars of zoysiagrass (Lobo, Zeon, Empire, and Meyer). The authors demonstrated that at the end of the drought, Lobo and Zeon exhibited greater normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and lower values of canopy mortality than Empire and Meyer. The greater resistance of Lobo and Zeon was not associated with greater capacity to avoid dehydration; instead, it was associated with a greater tolerance to dehydration. However, the study by Simpson et al.[18] was performed using small pots (8-cm long), which can limit proper root development and mask potential differences in drought avoidance across genotypes[21−23]. Small pot sizes can also alter plant recovery from drought, given the importance of root development in this trait[24−27].

In this study, the aim was to further examine the drought avoidance, tolerance, and recovery capacity of the four commercial cultivars of zoysiagrass assessed by Simpson et al.[18]. Specifically, we asked (1) whether the similar drought avoidance of Lobo, Zeon, Empire, and Meyer is confirmed when root development is not limited through the use of larger pots; and (2) whether these four cultivars display contrasting drought tolerance and recovery capacity when exposed to a more severe drought intensity. The aim was also to (3) confirm whether Lobo and Zeon display similar drought avoidance and contrasting drought tolerance at the field level, thus ensuring that large pots can be confidently used for selection in zoysiagrass breeding programs.

-

An experiment was conducted under controlled conditions to assess the drought responses of four commercial cultivars of zoysiagrass: Lobo™ (XZ 14069; Zoysia japonica Steud. x Z. matrella L. Merr.)[6], Zeon (Z. matrella)[28], Empire® (SS-500; Z. japonica)[29], and Meyer (Z. japonica)[30]. Zeon, Empire, and Meyer are economically important cultivars widely used throughout the US[8,9], and Lobo is a newly released cultivar bred for drought resistance[6]. Plants of each cultivar were obtained from the North Carolina State University Turfgrass Breeding program. Plugs of each cultivar were grown in large and long plastic pots (5.5 L in volume, 15.2 cm in diameter, and 30.5 cm in height) to allow proper root development (Supplementary Fig. S1)[22]. Pots were filled with a substrate consisting of calcined clay (Turface Athletics, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and coarse sand mixed in equal parts by volume. The grasses were cultivated in a greenhouse (Raleigh, NC, USA) for approximately 6 months, until the root systems reached the bottom of the pots, and the turf canopy completely covered the soil surface. During this time, plants were daily irrigated and fertilized via fertigation with a soluble all-purpose fertilizer (Water-soluble all-purpose plant food 24-8-16, Miracle-Gro). A week before the experiment, plants were moved to a walk-in growth chamber (Supplementary Fig. S1). Environmental conditions in the chamber were set to day/night temperatures of 30/21 ± 0.03 °C, day/night relative humidity of 35/65 ± 0.12%, 12-h photoperiod, photosynthetic photon flux density of c. 1,000 µmol·m−2·s−1, and CO2 concentration of 410 µmol·m−2·s−1. Pots were mowed every other week to a height of approximately 6 cm. Each pot, containing plants of a single cultivar, was considered a biological replicate.

Six pots (n = 6) of each cultivar were arranged randomly in the controlled environment chamber, each placed on a custom-built weigh lysimeter. Water loss of whole pots (canopy evapotranspiration) was measured every 10 min, and values were used to calculate daily evapotranspiration. Plants were allowed to dehydrate by withholding irrigation until each plant reached a leaf water potential (LWP) < −6.0 MPa, which represents a severe drought to these plants[18]. Measurements of LWP were taken every 2 days until the sixth day of drought and then every day until the ninth day of the drought. Measurements were performed at midday using a pressure chamber (Model 1505D, PMS Instruments) and a stereomicroscope to better visualize the leaf xylem. Two leaves were randomly selected per pot, and the average was used to describe the LWP of the plant stand in that pot. All plants reached LWP < −6.0 MPa between 7 and 9 days of drought (Supplementary Fig. S2). When plants reached this threshold water potential, they were re-irrigated and thereafter received daily irrigation for 10 additional days.

Plants were photographed and assessed for maximum photochemical quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm), percent green cover, and NDVI on the following days: prior to the drought, on the last day of the drought, the first day of recovery, and the tenth day of recovery. All measurements were performed at midday. The Fv/Fm was assessed using a LI-600N (LI-COR Biosciences, USA) in leaves sampled and maintained in the dark for at least 30 min. The same two leaves used for LWP measurements were used to describe the Fv/Fm of the plant stand in that pot. The NDVI was assessed using a hand-held device (FieldScout TCM 500 Turf Color Meter, Spectrum Technologies Inc.). The percent green cover was obtained via image analysis with TurfAnalyzer software (Green Research Services LLC.) using the Hue, Saturation, and Value color space to differentiate and select green leaf tissue from brown leaf tissue and the image background. The percent green cover was calculated as:

$ \text{Percent green cover}=\frac{\mathrm{Green\ pixels}}{\mathrm{Green\ pixels+Brown\ pixels}}\times100 $ Plant dehydration during natural droughts at the field level

-

The rate of plant dehydration was also assessed for Lobo and Zeon during natural droughts at an existing field trial that included these cultivars. Two other zoysiagrasses included in these field trials were El Toro (Z. japonica)[31], and Zenith (ZNW-1; Z. japonica). Field trials were performed at two locations: Lake Wheeler Turf Field Laboratory in Raleigh, NC, USA, and Sandhills Research Station in Jackson Springs, NC, USA. Soils in these locations are classified as Cecil sandy loam (fine, kaolinitic, thermic Typic Kanhapludults) in Raleigh[32], and as Candor sand (sandy, kaolinitic, thermic Grossarenic Kandiudults) in Jackson Springs[33]. Plots were established at the two locations in the spring of 2024 by transplanting 2.25 m2 of sod into 1.5 m × 1.5 m plots with 0.46 m alleys between plots. Each trial was arranged as a randomized complete block design with three replications. During establishment, plots were daily irrigated, and irrigation was withheld during the experiment period such that natural soil dehydration occurred. The drought evaluations were performed in the last week of August 2024 between rain events. The rain-free period lasted 5 days in Raleigh and 9 days in Jackson Springs. Mean day/night temperatures during the rain-free period were 26/14 °C in Raleigh and 29/17 °C in Jackson Springs. Leaves were sampled every 2 days at midday, placed in bags with moist paper towels, and taken to the lab in coolers filled with cold packs to minimize tissue dehydration. Measurements were performed using a pressure chamber and a stereomicroscope to better visualize the leaf xylem.

Data analysis for the performance of Lobo and Zeon during drought and recovery across multiple environments

-

We obtained data for Lobo and Zeon from the study of Gouveia et al.[34], which assessed the performance of zoysiagrasses during natural droughts at the field level. The data obtained for these cultivars are summarized in this study and are used to compare with the data obtained in the drought experiments under controlled conditions. Briefly, the study of Gouveia et al.[34] evaluated 45 zoysiagrass breeding lines and cultivars (including Lobo and Zeon) under natural prevalence of droughts at eight locations across the southern United States: Citra and Jay (FL), Dallas (TX), Griffin and Tifton (GA), Jackson Springs (NC), Stillwater (OK), and Riverside (CA). Data on turfgrass quality (rated visually on a scale of 1 to 9, where 1 = poor quality and 9 = outstanding quality, as described by the National Turfgrass Evaluation Program), percent green cover, NDVI, and green leaf index were collected from 2020 to 2023. Small unmanned aircraft systems were used to estimate percent green ground cover, NDVI, and green leaf index in all locations, with the exception of Jay and Riverside, where aircraft systems were not available. A detailed description of the estimation of the traits was published in Gouveia et al.[34]. Drought evaluations started when at least 50% of plots showed turfgrass quality ratings below 5, and were conducted weekly until the end of the drought period. Additionally, turfgrass quality was assessed 1−2 weeks after the end of drought periods to evaluate the recovery ability of the genotypes, where 9 = full recovery. The number of days that assessments were made for Lobo and Zeon during drought and recovery for each location and year in the field is presented in Supplementary Table S1. For further details on the methods, see Gouveia et al.[34].

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical analyses were performed in RStudio version 4.3.0[35]. Differences among cultivars for single-point measurements were tested using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test (p-value < 0.05) for data that met ANOVA's assumptions, while the Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn's test with a Bonferroni correction was used for those that did not.

Multiple-point measurements over time were plotted and inspected to determine general response curves. Cumulative evapotranspiration over time was fitted using a self-starting nonlinear least squares asymptotic regression model using the nlme package[36], expressed as:

$ {\mathrm{Cumulative}}\; {\mathrm{ET}} = {\mathrm{Asym}} + ({\mathrm{R}}0 - {\mathrm{Asym}}) \times {\mathrm{exp}}(-{\mathrm{exp}}({\mathrm{lrc}})^*{\mathrm{Day}}) $ where, cumulative ET is cumulative evapotranspiration, Asym is the upper asymptote, R0 is cumulative evapotranspiration at day 0, lrc is the natural logarithm of the rate constant, and Day is days since last irrigation. Differences among cultivars for cumulative evapotranspiration responses over time were tested using a non-linear model fit by maximum likelihood.

Leaf water potential over time was fitted using linear regressions, expressed as:

$ {\mathrm{Leaf}}\; {\mathrm{water}} \;{\mathrm{potential}} = \beta 1 \times {\mathrm{Day}} - \beta 0 $ where, β1 is the slope and β0 is the intercept. Differences among cultivars for leaf water potential responses over time were tested using ANOVA (p-value < 0.05). When appropriate, Tukey's test (p-value < 0.05), a post hoc mean separation test, was employed to compare the cultivar effect on model parameters using the emmeans package[37].

For the field evaluations of Lobo and Zeon, a stage-wise analysis was performed using the ASReml package v.4[38]. For each trial, analysis was conducted separately for each location and year. In this first stage, genotype, and repetition were treated as fixed effects, while repeated measures and the interaction between genotype and repeated measures were modeled as random effects. From this model, the best linear unbiased estimates (BLUEs) and Smith's weights[39] (the diagonal elements of the inverse variance-covariance matrix of the predicted values) were extracted and used in a second-stage analysis. In the second model, genotype, location, and the genotype x location interaction were considered as fixed effects, whereas year and its interaction with location, genotype, and genotype × location were treated as random effects. An exception was made for NDVI, as data was not available across multiple years in each location; thus, the model contained only the fixed effects of genotype and location, and the interaction between these two effects. Differences between the cultivars were assessed using the least significant difference using ASRemlPlus[40].

-

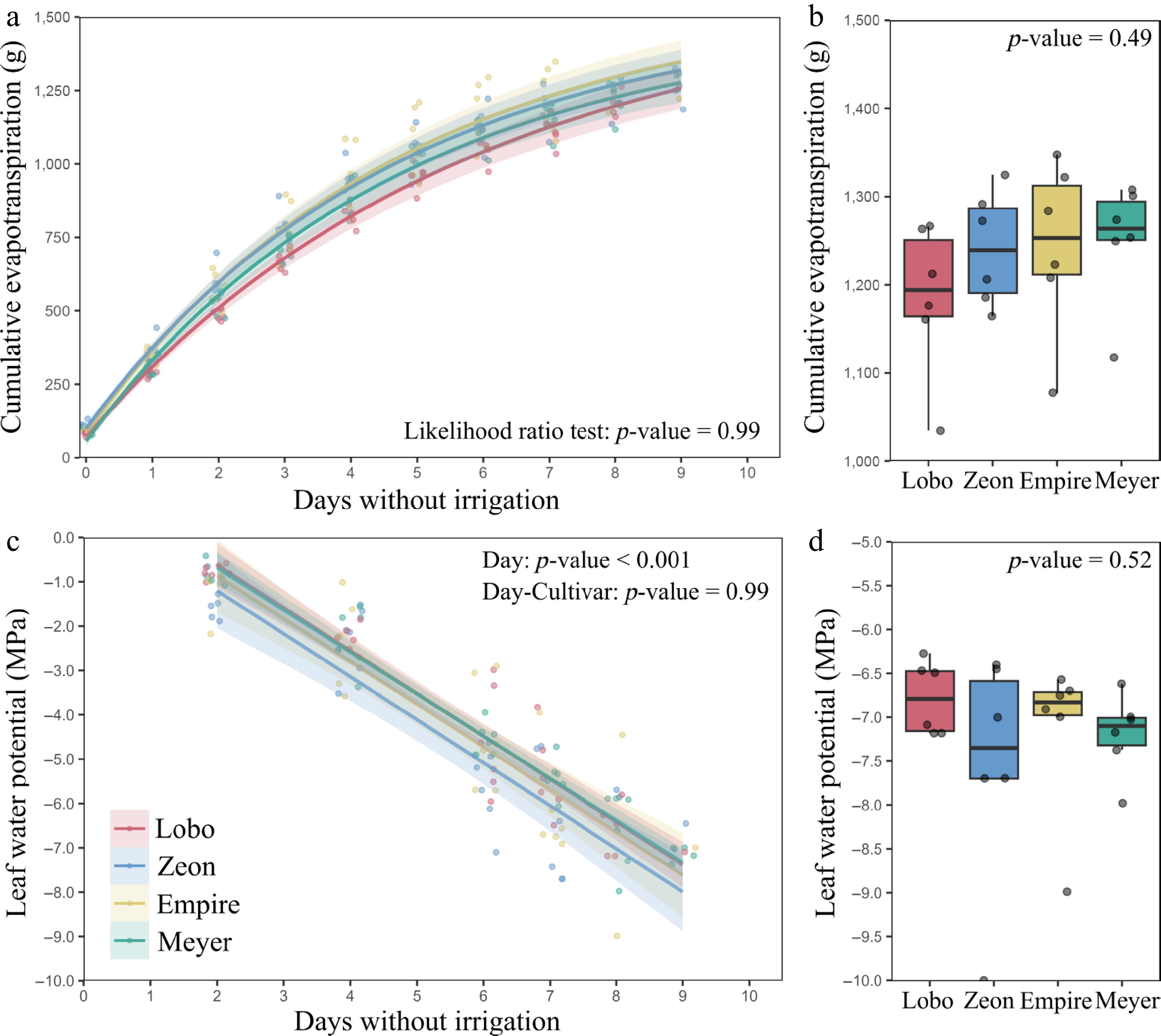

During the dry-down experiment, plants of all cultivars reduced their daily evapotranspiration rates, and therefore, the slope of the cumulative evapotranspiration curves (Fig. 1a). A likelihood ratio test found no effect of cultivar (p-value = 0.87) for the relationship between cumulative evapotranspiration rate and days without irrigation. On the last day of the drought, all cultivars lost on average (± SD) 1,230 ± 80 g of water, with no difference among cultivars (p-value = 0.49) (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Changes in cumulative evapotranspiration and leaf water potential during drought under controlled conditions. (a) Plateauing cumulative evapotranspiration after irrigation withholding, and (b) final cumulative evapotranspiration on the last day of drought. (c) Declines in leaf water potential after irrigation withholding, and (d) minimum leaf water potential on the last day of drought. Data are for four zoysiagrass cultivars (n = 6). Lines in (a) and (c) represent curve fits to data points, and shadings represent 95% confidence intervals. Parameters for the curves are present in the Supplementary Table S2. The p-value in (a) was calculated using a likelihood ratio test, and the p-values in (b)−(d) were calculated using ANOVA.

Plants of all cultivars experienced decreases in LWP during the dry-down experiment (Fig. 1c). On average (± SD), LWP declined from −1.0 ± 0.4 MPa on the third day of drought to −7.2 ± 0.9 MPa on the last day of drought. Plants from different pots (biological replicates) required different days to reach LWP < −6.0 MPa, ranging from 7 to 9 d (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, differences in dehydration rate and days to reach LWP < −6.0 MPa were not affected by cultivar (p-value = 0.99 for the effect of cultivar on the relationships between LWP and days without irrigation in Fig. 1c; p-value = 0.09 for the effect of cultivar on days to −6.0 MPa in Supplementary Fig. S2). All cultivars had similar final LWP on the last day of drought (p-value = 0.52) (Fig. 1d). Parameters for the relationships between cumulative evapotranspiration x days without irrigation, and between LWP x days without irrigation are found in Supplementary Table S2.

Performance during drought under controlled conditions

-

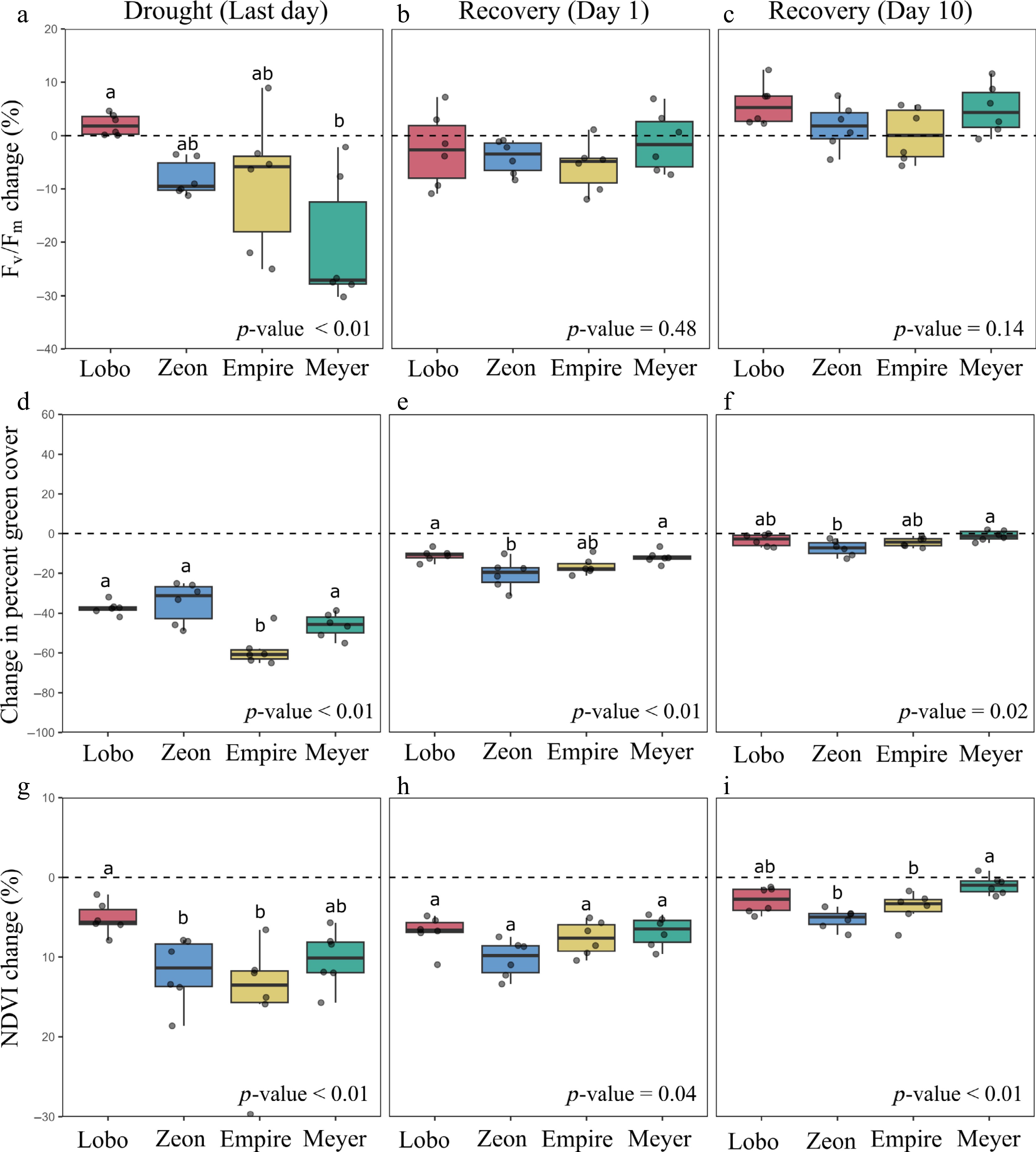

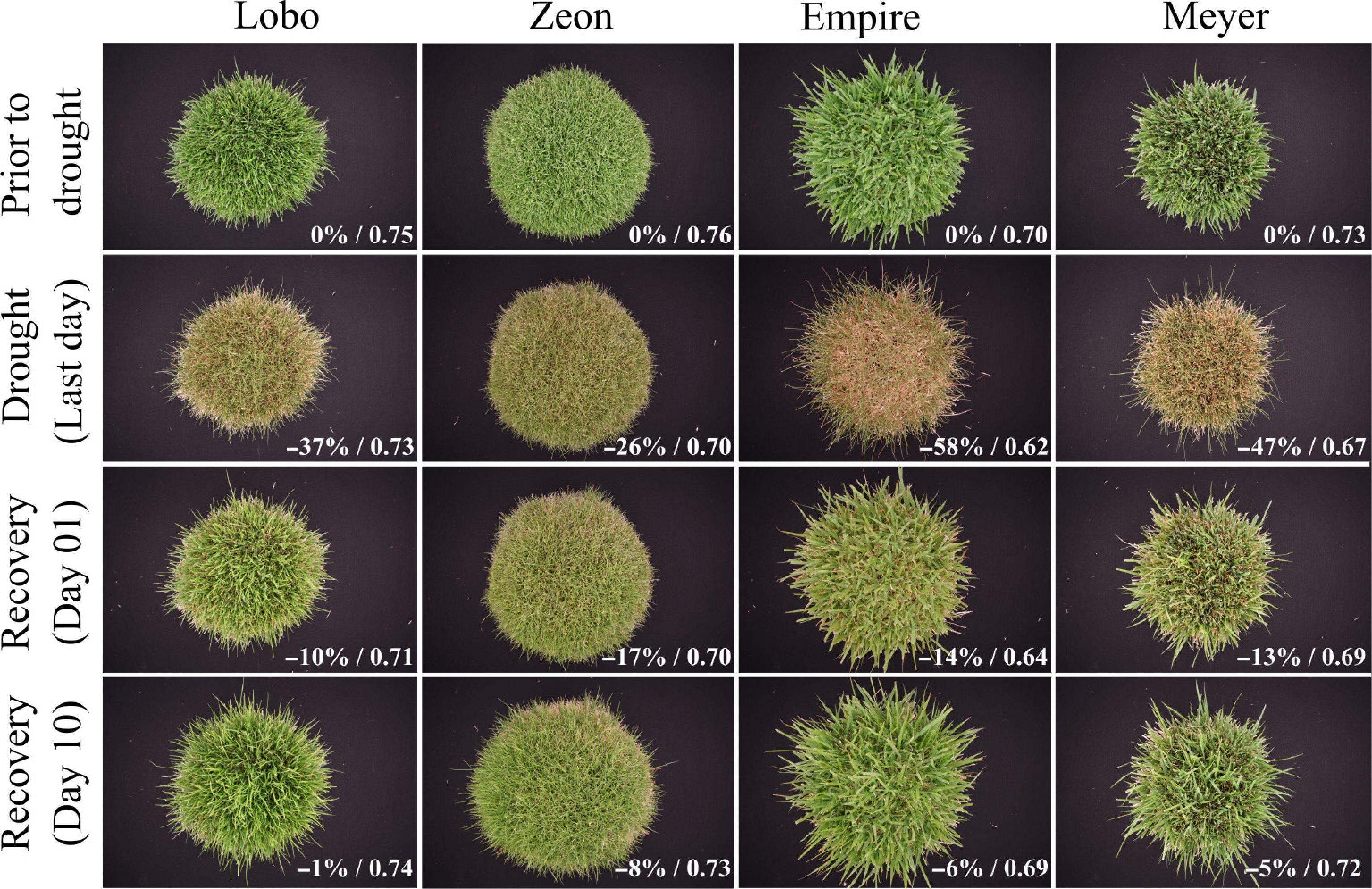

On the last day of drought, when plants experienced LWP of −7.2 ± 0.9 MPa, most plants displayed lower values of Fv/Fm, percent green cover, and NDVI (Fig. 2). Lobo was the only cultivar to maintain similar or higher values of Fv/Fm on the last day of drought when compared to before the drought (Fig. 2a). Zeon exhibited declines in Fv/Fm up to 11%, Empire of up to 25%, and Meyer of up to 30%. Lobo, Zeon, and Empire were statistically similar, and Lobo experienced lower declines in Fv/Fm than Meyer. On average, Fv/Fm values on the last day of drought were 0.73 for Lobo, 0.67 for Zeon, 0.68 for Empire, and 0.56 for Meyer (Supplementary Data 1).

Figure 2.

Changes at the leaf and canopy levels during and after drought under controlled conditions. Percent changes in maximum photochemical quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm), canopy green cover, and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) on the (a)–(c) last day of drought as well as on the (d)–(f) first, and (g)–(i) tenth days of recovery. Percent changes were calculated based on values obtained prior to the drought (represented by the dashed lines). Data are for four zoysiagrass cultivars (n = 6). Original values are present in the Supplementary Data 1. The p-values were calculated using ANOVA, and different letters denote statistical differences among cultivars according to Tukey's test (p-value < 0.05). In (a), (c), p-values were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis, and different letters denote statistical differences among cultivars according to Dunn's test with Bonferroni correction.

On the last day of drought, Lobo, Zeon, and Meyer exhibited lower declines in percent green cover than Empire (Fig. 2b). Lobo, Zeon, and Meyer declines ranged from c. 25 to 51%, while Empire declines ranged from c. 42 to 65% (Supplementary Data 1). Regarding NDVI, Lobo experienced lower declines in NDVI than Zeon and Empire, and similar to Meyer (Fig. 2c). Declines in NDVI were lower than 8% for Lobo, lower than 16% for Meyer, and ranged between 7 and 30% for Zeon and Empire. Average NDVI values on the last day of drought were 0.71 for Lobo, 0.66 for Zeon, 0.61 for Empire, and 0.64 for Meyer.

Recovery from drought under controlled conditions

-

After a single day of recovery, plants already exhibited higher values of Fv/Fm, percent green cover, and NDVI when compared to the last day of drought. All plants exhibited values of Fv/Fm similar to, greater than, or only slightly lower than those the plants exhibited prior to drought exposure (Fig. 2d). No difference was observed across cultivars for recovery of Fv/Fm (p-value = 0.48). Average Fv/Fm values on the first day of recovery ranged between 0.70 and 0.71 for all cultivars (Supplementary Data 1). Plants of all cultivars also exhibited greater percent green cover on the first day of recovery than on the last day of drought (Fig. 2e), demonstrating that leaves quickly unrolled upon rehydration (Fig. 3). Still, declines in percent green cover were observed for all pots, indicating partial canopy mortality due to drought (Fig. 2e). Lobo, Empire, and Meyer exhibited similarly lower declines in percent green cover. Declines were lower in Lobo and Meyer than in Zeon. Lobo, Empire, and Meyer also exhibited greater NDVI values than Zeon on the first day of recovery (Fig. 2f). NDVI values on the first day of recovery were similar across all cultivars according to Tukey's test, despite the ANOVA p-value of 0.043. Average values were 0.70 for Lobo, 0.68 for Zeon, 0.66 for Empire, and 0.67 for Meyer (Supplementary Data 1).

Figure 3.

Changes in canopy during and after drought under controlled conditions. Sequence of canopy appearance of plants from four zoysiagrass cultivars before the drought, on the last day of the drought, and during the recovery (first and tenth d). Values at the bottom right are percentage changes in green cover relative to the control and NDVI for the specific plants represented in this image. For size reference, pot diameter = 15 cm.

After 10 d of recovery, all cultivars had successfully recovered Fv/Fm to pre-drought levels and exhibited percent green cover and NDVI only slightly lower than pre-drought levels. Lobo had reached higher values of Fv/Fm than those obtained before the drought (Fig. 2g). Zeon, Empire, and Meyer exhibited relatively similar values of Fv/Fm to those before the drought. No difference was observed across cultivars for recovery of Fv/Fm on the last day of drought (p-value = 0.14). Average Fv/Fm values ranged between 0.74 and 0.76 for all cultivars (Supplementary Data 1). The percent green cover was similar to or only slightly lower than pre-drought levels (Fig. 2h). Lobo, Empire, and Meyer exhibited similarly high values of percent green cover (Fig. 2h), while Lobo and Meyer exhibited similarly high values of NDVI (Fig. 2i).

Leaf dehydration and turfgrass performance during natural field droughts

-

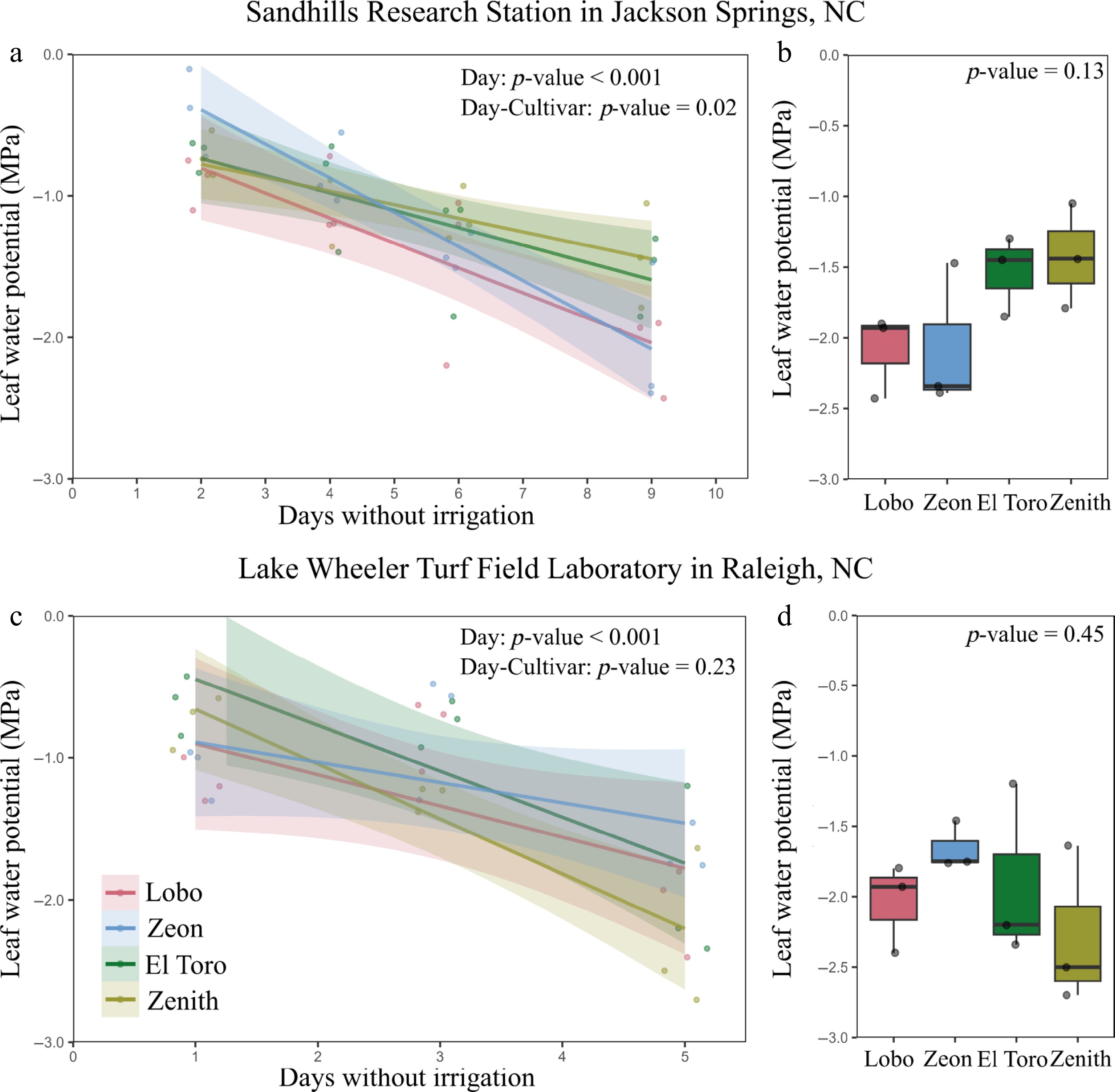

Declines in LWP during natural droughts were assessed in two field sites. In Jackson Springs, the slopes of LWP decline over time were similar between Lobo, Zeon, and El Toro, while Zenith exhibited a lower slope than Zeon (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table S3). Yet, after 9 days without irrigation or rain, all cultivars exhibited similar LWP (p-value = 0.13) (Fig. 4b). In Raleigh, plants only experienced 5 days without irrigation or rain. In this site, the slopes of declines in LWP over time were similar across all cultivars (Fig. 4c), and all cultivars exhibited similar LWP after 5 days without irrigation or rain (p-value = 0.45) (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Changes in leaf water potential during natural field droughts. (a) Declines in leaf water potential with days without irrigation during a rain-free period at Sandhills Research Station in Jackson Springs, NC, USA, and (b) minimum leaf water potential on the last day of drought. (c) Declines in leaf water potential with days without irrigation during a rain-free period at Lake Wheeler Turf Field Laboratory in Raleigh, NC, USA, and (d) minimum leaf water potential on the last day of drought. Data are for four zoysiagrass cultivars (n = 3). Lines in (a) and (c) represent curve fits to data points, and shadings represent 95% confidence intervals. Parameters for the curves are present in the Supplementary Table S3. The p-values were calculated using ANOVA.

Data analysis for the performance of Lobo and Zeon across multiple environments

-

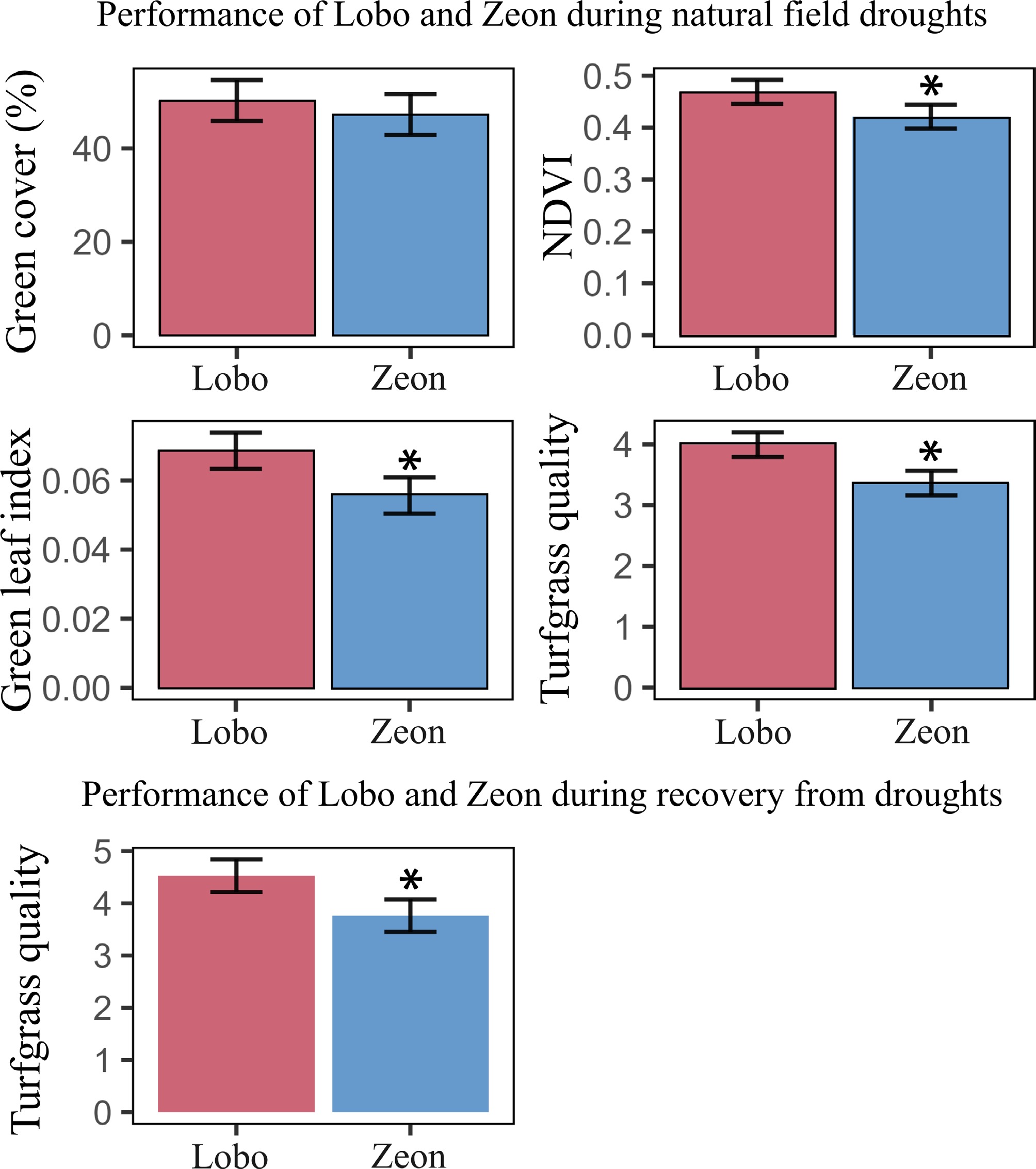

When assessing important traits related to turfgrass quality for Lobo and Zeon under natural field droughts, Lobo and Zeon exhibited similar percent green cover, but Lobo displayed greater NDVI, green leaf index, and turfgrass quality (via visual rating by turfgrass professionals) (Fig. 5). During the recovery period after natural droughts (up to 15 d after rains resumed), Lobo also demonstrated greater turfgrass quality than Zeon (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Critical turfgrass traits of Lobo and Zeon during natural field droughts and recovery. Best linear unbiased estimates for percent green ground cover, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), green leaf index, and turfgrass quality for Lobo and Zeon evaluated in field trials from 2020−2023 across eight locations in the southern US. Error bars represent the least significant difference. Asterisks denote statistical differences between cultivars according to the least significant difference.

-

In this study, dehydration of potted turf stands after irrigation was withheld was monitored and it was observed that LWP declined similarly throughout the drought among the four zoysiagrass cultivars (Fig. 1). Similar dehydration rates across these four cultivars have been previously demonstrated in a study using small pots (8-cm long)[18], and the current study confirms this result using longer and larger pots (Supplementary Fig. S1). The pots used in the current experiment are approximately 30.5 cm long and 5.5 L in volume, which allows the root systems of zoysiagrass to properly develop[21]. Given that most roots of zoysiagrass plants occur within the first 30 cm of soil[14,41,42], we believe that this approach was suitable to capture potential root system variation across cultivars. This, in turn, would be reflected in their ability to capture soil water and, therefore, in their dehydration rates during the dry-down.

Lobo and Zeon were also cultivated in two field sites, and they were found to have similar drought avoidance at the field level (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S3). These results likely confirm the suitability of large pots to assess drought avoidance in zoysiagrass. It is important to note, however, that a few breeding programs are currently aiming to develop zoysiagrasses with deeper roots, and some breeding lines are capable of growing deeper roots[9]. The evaluation and selection of these lines is possible in the field or using even longer pots (90 cm or longer)[16,41,42].

In addition to assessing the drought avoidance potential of Lobo and Zeon, two additional commercial cultivars of zoysiagrass were included in the field trials (El Toro and Zenith) to determine if they would also show similar dehydration avoidance. Empire and Meyer were not present in these trials. Interestingly, when assessing the drought avoidance of these four cultivars at the field level, a genotype × environment interaction was observed (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S3). All cultivars exhibited similar drought avoidance in Raleigh, where soils are shallow due to the presence of large (> c. 10 cm) rocks (personal observation), and the drought developed faster. The rocks were present less than 8 cm deep across the field where the trial was grown (personal observations), which likely imposed a mechanical resistance to root elongation[43], and resulted in similar drought avoidance across cultivars. Conversely, Zenith dehydrated more slowly than Zeon in Jackson Springs, where soils are deeper, which potentially allowed differential root growth between these cultivars. The mechanical restriction to roots in Raleigh likely explains why plant dehydration occurred faster in this site, which contains sandy loam soils, than in Jackson Springs, which contains sandy soils. Restricted soil depth has also been documented to negatively affect the drought resistance of bermudagrass and buffalograss[44]. Further experiments with Zenith are needed in more locations to confirm whether this cultivar has a greater ability to grow longer roots, or to better restrict water loss, thus resulting in greater drought avoidance and turfgrass quality during drought.

Differences in drought tolerance across cultivars

-

In a previous experiment, it was found that Lobo and Zeon (cultivars with narrower leaves, < 2 mm) exhibited greater NDVI and higher percent green cover than Empire and Meyer (cultivars with wider leaves of c. 3 mm) during a drought event of severity of c. −4.5 MPa[18]. However, our previous study did not separate Lobo from Zeon, or Empire from Meyer. In the current study, plants were exposed to a more severe drought (of −6 MPa), and all pots experienced similar LWP at the time of evaluations, an important aspect of drought experiments designed to evaluate contrasting drought tolerance[45,46]. In this experiment, it is confirmed that Lobo has a greater drought tolerance than Empire and Meyer. However, Zeon has a similar drought tolerance to Empire and Meyer. It is further demonstrated that during drought, Lobo displays improved turfgrass traits over Zeon (Fig. 2c), and Meyer displays improved turfgrass traits over Empire (Fig. 2b). The improved canopy traits (particularly NDVI) of Lobo over Zeon in this experiment are in line with field assessments during drought across multiple locations and years (Fig. 5). Different to NDVI, percent green cover during drought was similar between Lobo and Zeon, both in the controlled-environment and the field experiments. This demonstrates that NDVI is more sensitive than percent green cover in capturing differences across genotypes.

The comparison between two drought experiments with different drought intensities (the current experiment and that of Simpson et al.[18]) suggests that differences between genotypes to a certain stress might be present at more severe stress levels, while not at mild or moderate levels. An alternative hypothesis is that an improved evaluation of the cultivars occurred because of a more realistic root-to-shoot ratio allowed by the larger pots[21−23]. Altogether, the present results confirm the importance of assessing genotypes at multiple stress levels and environmental conditions, as well as using large pots (when performing drought under controlled conditions) so that more informed decisions are made during selection processes[21,47].

Differences in drought recovery capacity across cultivars

-

One day after soil rehydration, Lobo and Meyer were demonstrated to exhibit lower permanent declines in percent green cover than Zeon (Fig. 2e). After only a few hours of rehydration, live grass leaves unroll, changing our perception of canopy damage due to drought[18]. Because no new leaves are formed at this early stage of recovery, differences in percent green cover likely reflect more differences in drought tolerance than differences in the ability to recover from drought. Recovery ability is better demonstrated after plants have time to resume function and growth, so that the efficacy of drought tolerance mechanisms is assessed[46]. Interestingly, for the zoysiagrass cultivars, increased drought tolerance did not translate into increased recovery capacity in the controlled environment experiment. Lobo, for instance, had greater drought tolerance than the other three cultivars, but similar recovery capacity to all of them in the controlled environment-drought. Meanwhile, Meyer had similar drought tolerance to Zeon but greater recovery capacity.

Conversely, Lobo was demonstrated to exhibit greater turfgrass quality than Zeon during recovery after natural field droughts (Fig. 5). Differences between results from controlled environment and field might be associated with the intensity of the drought plants were exposed to and the level of rehydration post-drought[48,49]. The field data summarizes recovery from a number of drought events in multiple locations, and recovery might or might not have entailed complete rehydration of plants. The environmental conditions during the recovery period are also known to largely influence plant recovery capacity[15,48,50], which might have contributed to differences between the controlled environment and the field droughts. In addition, different mechanisms are associated with drought tolerance and recovery capacity[51]. Drought tolerance mechanisms commonly involve the ability of plants to sustain water transport[52,53] as well as tissue and cell integrity[54−56]. Drought recovery capacity partially relies on drought tolerance; genotypes that tolerate drought better are likely to recover better from it[46]. However, drought recovery capacity also relies on the level of carbohydrates in plant tissues so that plants can resume growth in a fast and efficient manner[24,57]. Therefore, drought tolerance and recovery capacity might or might not occur in parallel, and breeding programs should adapt their selection methods to select lines with both improved tolerance and recovery capacity. In the case of Lobo, a combination of tolerance and recovery capacity seems to have been achieved, as observed in the field dataset from multiple environments (Fig. 5).

When comparing the findings of this study with those of Simpson et al.[18], differences were observed, particularly for Meyer. Meyer displayed a good recovery capacity in the current study, but not in the study of Simpson et al.[18]. Differences between the current experiment and the previous one might be driven by differences in pot size. Given the importance of roots for plant recovery from drought[24,26], we might have been able to uncover differences among cultivars by using larger pots and allowing plants to achieve a more realistic root-to-shoot ratio. It is possible that Meyer was able to better grow new leaves and recover from drought in this experiment by relying on a more resilient root system[25]. While most studies demonstrate the importance of roots for drought avoidance (by sustaining water uptake), recent studies show that roots are also important for drought tolerance, and recovery from drought[24,26]. During drought, roots undergo dehydration and potentially hydraulic dysfunction[58], which directly impairs the ability of plants to survive and grow upon rehydration. Therefore, perennial grasses with greater root tissue density and narrow xylem vessels have been associated with greater resilience to drought, likely due to a greater embolism resistance[25]. Further studies associating root morphological traits with drought tolerance and recovery capacity from drought in zoysiagrasses would be highly informative to define critical traits to be selected by breeding programs.

-

We were able to confirm that Lobo, Zeon, Empire, and Meyer have similar drought avoidance using larger pots that allow roots to better develop. Similar drought avoidance between Lobo and Zeon was also confirmed in two field locations. This study confirms that Lobo displays greater drought tolerance than Zeon, Empire, and Meyer and uncovers a superior recovery capacity of Lobo than Zeon under more severe droughts. The greater drought tolerance of Lobo over Zeon is consistent with results from the field. Lobo displayed a greater recovery capacity than Zeon in the field, but not in the controlled environment. While most studies show genotypic differences in water use across zoysiagrass lines and cultivars, contrasting drought tolerance and recovery capacity were identified. The present findings show that drought avoidance, tolerance, and recovery capacity in zoysiagrass seem to be independent of one another, which opens the possibility for achieving all three at the same time through breeding efforts. However, selection methods need to be designed to capture differences in these three traits. Finally, it is demonstrated that drought experiments using large pots can yield similar results to those at the field level, and can potentially be used for selecting superior lines of zoysiagrass in breeding programs. Still, assessments at the field level should always be prioritized when possible because of potential genotype × environment interactions.

This study was supported by the Center for Turfgrass Environmental Research and Education Board (CENTERE) and the Research Capacity Fund (HATCH), project award no. 7003279, from the US Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Danielle Oliveira was supported by the Research Support Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Cardoso AA, Milla-Lewis S; data collection: Cardoso AA, Taggart M, Oliveira D, Gouveia BT, Enguídanos ÓA; analysis and interpretation of results: Cardoso AA, Taggart M, Gouveia BT, Suchoff D, Milla-Lewis SR; draft manuscript preparation: Cardoso AA, Gouveia BT, Suchoff D, Milla-Lewis SR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the Supplementary Data 1.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 The number of days that data was collected for Lobo and Zeon for each location and year.

- Supplementary Table S2 Parameters for the relationship between cumulative evapotranspiration and days without irrigation and between leaf water potential and days without irrigation for four zoysiagrass cultivars.

- Supplementary Table S3 Parameters for the relationships between leaf water potential and days without irrigation for four zoysiagrass cultivars in two field sites.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Representative images showing pot size and plants during the experiment.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Days without irrigation for each cultivar.

- Supplementary Data 1 Original data used to prepare figures.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Cardoso AA, Taggart M, Oliveira D, Gouveia BT, Enguídanos ÓA, et al. 2026. Similar drought avoidance and contrasting tolerance and recovery capacity across zoysiagrass cultivars: insights from controlled and field droughts. Grass Research 6: e003 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0031

Similar drought avoidance and contrasting tolerance and recovery capacity across zoysiagrass cultivars: insights from controlled and field droughts

- Received: 12 August 2025

- Revised: 30 September 2025

- Accepted: 06 November 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: Improvements in water use efficiency and drought resistance in turfgrasses can help them maintain performance and quality with reduced irrigation, thereby contributing to water conservation. This study aimed to better understand the importance of drought avoidance, tolerance, and recovery from drought across three economically important cultivars of zoysiagrass and a newly released zoysiagrass cultivar with increased drought resistance. Experiments were performed under controlled conditions using long pots (30 cm deep) and in the field. Results from the controlled drought demonstrate that Lobo, Zeon, Empire, and Meyer have similar drought avoidance. The similar drought avoidance between Lobo and Zeon was also confirmed under natural droughts at two field locations. Tolerance and recovery from drought differed across cultivars. Lobo displayed greater tolerance than Zeon, Empire, and Meyer under controlled drought conditions. The greater tolerance of Lobo over Zeon was consistent with results from field droughts. Under controlled drought, Lobo and Meyer had greater recovery capacity than Zeon and Empire, and under field droughts, Lobo also had greater recovery than Zeon. While most studies show differences in water use across zoysiagrass lines and cultivars, contrasting drought tolerance and recovery capacity were identified in this study. The present findings indicate that drought avoidance, tolerance, and recovery capacity in zoysiagrass are independent of one another, which opens the possibility of achieving all three simultaneously through breeding efforts. For that, selection methods need to account for the three strategies, preferably at the field level or under controlled conditions using long pots.

-

Key words:

- Controlled conditions /

- Drought resistance /

- Field experiment /

- Selection methods /

- Turfgrass quality