-

Euodiae fructus (Wuzhuyu), a traditional Chinese medicinal herb derived from the nearly ripe fruits of Euodia rutaecarpa[1] (syn. Tetradium ruticarpum (A. Juss.) T. G. Hartley in Flora of China[2]) and related species from Rutaceae plants harvested from August to October, has been widely utilized in East Asian medicine for centuries to address conditions associated with cold stagnation and yang deficiency. Euodia rutaecarpa has also been referred to as Euodiae fructus[3] or Tetradium fructus[2]. Its earliest documentation can be traced back to the ancient text 'Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing'. Furthermore, it is officially recognized and listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. According to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, Euodiae fructus is defined as the fruit of one of the following species or varieties: E. rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth., E. rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth. var. officinalis (Dode) Huang (referred to as 'Shi-Hu' in Pinyin), or E. rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth. var. bodinieri (Dode) Huang (referred to as 'Shu-Mao Wu-Zhu-Yu' in Pinyin)[1]. Characterized by its pungent, bitter, and hot properties, it traditionally serves to dispel cold, alleviate pain, and regulate gastrointestinal and hepatic functions. Historically documented in Shennong Bencao Jing and Compendium of Materia Medica, Wuzhuyu has been prescribed for ailments ranging from migraines and abdominal cold pain to vomiting and diarrhea, reflecting its versatility in harmonizing the liver, spleen, kidney systems, hypertension, and dermatological conditions[4,5]. Such as used for treating headache, cold hernia abdominal pain, dampness beriberi, abdominal pain, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, high blood pressure, external cure sores, etc.

Modern pharmacological studies have identified over 300 compounds in Wuzhuyu, including alkaloids (e.g., evodiamine, rutaecarpine, dehydroevodiamine), limonoids, volatile oils, flavonoids, and polysaccharides[6,7]. These components exhibit anti-inflammatory[8,9], antimicrobial[10], antithrombotic[11], and anti-tumor activities[12], with notable efficacy in modulating cardiovascular function and gastrointestinal[13] health. For instance, evodiamine (Evo), a key alkaloid, demonstrates anti-tumor[14], immunomodulatory[15], and analgesic properties[16]. Clinical studies further validate its role in treating inflammation-related diseases and metabolic disorders through mechanisms such as COX-2 inhibition[8] and adipogenesis suppression[17].

Despite its therapeutic potential, concerns regarding neurotoxicity, fetal risks, and drug interactions (e.g., antagonism with adrenergic agents) underscore the need for standardized dosing and rigorous toxicological evaluations[18,19]. The challenges persist in harmonizing traditional formulations (e.g., Wuzhuyu Tang, Zuo-Jin Pill) with modern clinical practices.

In this review, the chemical composition and pharmacological effects of E. rutaecarpa officinalis in recent years are reviewed, to provide a reference for the pharmacological efficacy research, quality evaluation, and new drug development research of E. rutaecarpa.

-

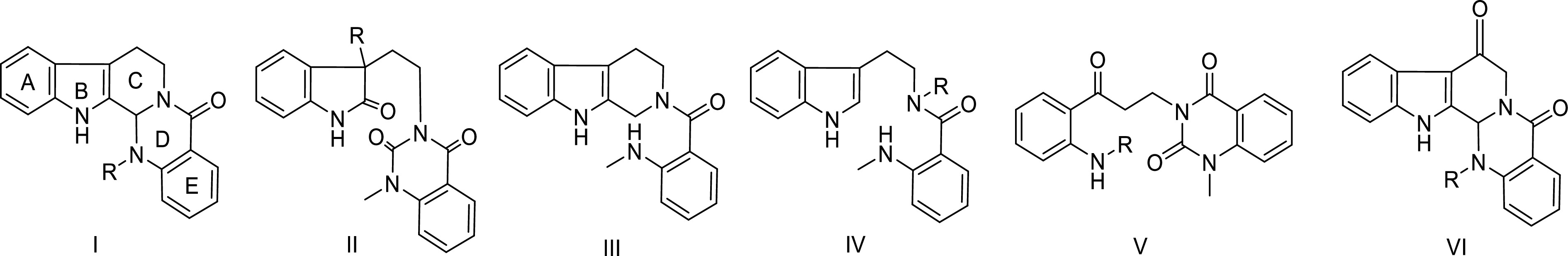

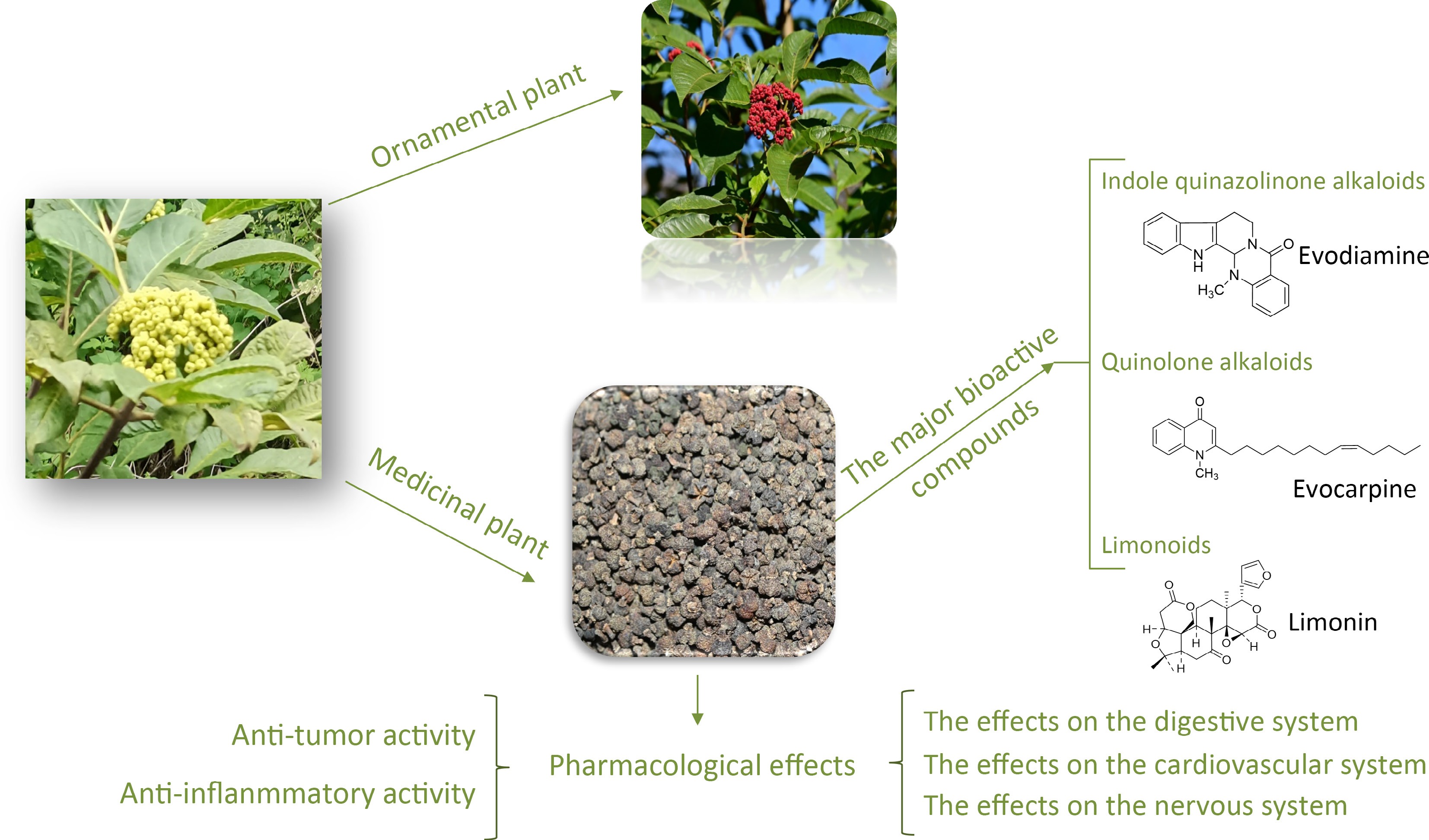

Euodia rutaecarpa contains about 300 compounds[7]. Among these, the primary bioactive compounds can be categorized into three major classes: indole alkaloids, quinolone alkaloids, and limonoids (Fig. 1). In this review, we summarized 143 alkaloids, including 58 indole quinazoline alkaloids, and 85 quinolone alkaloids, 21 limonins, and others. The specific information of these compounds is shown in Tables 1−5.

Figure 1.

The chemical composition of Euodia rutaecarpa is diverse and includes alkaloids, limonoids, flavonoids, and volatile oils. The major bioactive compounds are: indole quinazolinone alkaloids, quinolone alkaloids, and limonoids.

Table 1. Quinazoline alkaloids isolated from Euodia plants.

No. Indole quinazoline alkaloids Molecular formula Relative molecular mass Structure type Ref. 1 Evodiamine (EVO) C19H17N3O 303 I [20−25] 2 Hydroxyevodiamine C19H17N3O2 319 I [26] 3 13β-acetongl hydroxyl evodiamine C22H21N3O2 359 I [27] 4 Carboxyevodiamine C20H17N3O3 347 I [28] 5 13,14-dihydrorutaecarpine C18H15N3O 289 I [29] 6 14-N-formyldihydrorutaecarpine C19H15N3O2 317 I [22,23] 7 13β-hydroxymethylevodiamine C20H19N3O2 333 I [30] 8 Rutaecarpine (RUT) C18H13N3O 287 I [21−25] 9 Hortiacine C19H15N3O2 317 I [31] 10 1-hydroxyrutaecarpine C18H13N3O2 303 I [32] 11 3-hydroxyrutaecarpine C18H13N3O2 303 I [29] 12 7β-hydroxyrutaecarpine C18H13N3O2 303 I [22,23,25,33,34] 13 10-hydroxyrutaecarpine C18H13N3O2 303 I [35] 14 (7R,8S)-7,8-hydroxyrutaecarpine C18H13N3O3 319 I [32] 15 (7R,8S)-7-hydroxy-8-methoxy-rutaecarpine C19H15N3O3 333 I [32] 16 (7R,8S)-7-hydroxy-8-ethoxy-rutaecarpine C20H17N3O3 347 I [32] 17 N13-methyl rutaecarpine C19H15N3O 301 I [36] 18 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosylrutaecarpine C24H23N3O7 465 I [37] 19 Rutaecarpine-2-O-β-D-glucopyranoside C24H23N3O7 465 I [37] 20 Rutaecarpine-10-O-β-D-glucopyranoside C24H23N3O7 465 I [38] 21 Rutaecarpine-10-O-β-D-rutinoside C30H33N3O11 611 I [38] 22 13-methyl-13H-indolo [2',3':3,4] pyrido[2,1b] quinazolin-5-one C19H13N3O 299 I [39] 23 7,8-dehydrorutaecarpine C18H11N3O 285 I [30] 24 Pseudorutaecarpine C18H13N3O 287 I [32] 25 Dehydroevodiamine C19H15N3O 301 I [22,23,40] 26 Hortiamine C20H17N3O2 331 I [41] 27 Dehydroevodiamine chloride C19H16N3OCl 337 I [31] 28 Evodianinine C19H13N3O 299 I [20] 29 Wuzhuyurutine A C17H11N3O2 289 I [36] 30 Evodiagenine C19H13N3O 299 I [42] 31 Evodiaxinine C20H15N3O 313 I [20,43] 32 (+) evodiakine C19H17N3O3 335 I [44] 33 (−) evodiakine C19H17N3O3 335 I [44] 34 Dievodiamine C38H30N6O2 602 I, II [42] 35 Wuchuyuamide I C19H17N3O4 351 II [21,22,25,31] 36 Wuchuyuamide II C19H17N3O3 335 II [45] 37 Evollionines B C20H19N3O5 381 II [46] 38 Goshuyuamide-II C19H17N3O2 319 II [25,47] 39 13-hydroxymethyl goshuyuamide-II C20H19N3O3 349 II [48] 40 10-methoxygoshuyuamide-II C20H19N3O3 349 II [29] 41 Wuzhuyurutine C C18H13N3O3 319 II [30] 42 Wuzhuyurutine D C17H11N3O3 305 II [30] 43 (s)-7-hydroxysecorutaecarpine C18H15N3O3 321 II [25,37] 44 Wuzhuyurutine B C17H11N3O3 305 II [30] 45 Bouchardatine C17H11N3O2 289 II [30] 46 Evodiamide A C20H19N3O5 381 II [40] 47 Evodiamide B C19H16N4O2 332 II [40] 48 Evodiamide C C37H32N6O6 656 II, IV [40] 49 Goshuyuamide-I C19H19N3O 305 III [23,25,47] 50 Rhetsinine C19H17N3O2 319 III [49] 51 Evollionines A C19H15N3O2 317 III [46] 52 Evodiamide C19H21N3O 307 IV [23,27] 53 Dimethyl evodiamide C18H19N3O 293 IV [47] 54 Nb-demethylevodiamide C18H19N3O 293 IV [50] 55 Wuchuyuamide III C18H17N3O3 323 V [40,51] 56 Wuchuyuamide IV C19H17N3O4 351 V [51] 57 Wuchuyuamide V C20H19N3O5 381 V [21] 58 Evodamide A C19H15N3O2 317 VI [29] Table 2. Quinolone alkaloids isolated from Euodia plants.

No. Quinolone alkaloids Molecular formula Relative molecular mass Structure type Ref. 1 2-ethyl-1-methyl-4(1H)-quinolone C12H13NO 187 I [52] 2 Quinolone A C14H15NO3 245 I [53] 3 1-methyl-2-pentyl-4(1H)-quinolone C15H19NO 229 I [52] 4 Methyl 5-(1,4-dihydro-1-methyl-4-oxoquinolin-2-yl) pentanoate C16H19NO3 273 I [46] 5 1-methyl-2-heptyl-4(1H)-quinolone C17H23NO 257 I [52] 6 1-methyl-2-octyl-4(1H)-quinolone C18H25NO 271 I [52] 7 1-methyl-2-nonyl-4(1H)-quinolone C19H27NO 285 I [25,52] 8 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-4-nonenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C19H25NO 283 I [54] 9 1-methyl-2-decyl-4(1H)-quinolone C20H29NO 299 I [52] 10 1-methyl-2-undecyl-4(1H)-quinolone C21H31NO 313 I [25,52] 11 1-methyl-2-[(E)-1-undecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H29NO 311 I [54] 12 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-5-undecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H29NO 311 I [30] 13 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-6-undecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H29NO 311 I [30] 14 1-methyl-2-[6-carbonyl-(E)-4-undecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H27NO2 325 I [30] 15 1-methyl-2-[7-carbonyl-(E)-5-undecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H27NO2 325 I [54] 16 1-methyl-2-[(1E,5Z)-1,5-undecadienyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H27NO 309 I [54] 17 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-1-undecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H29NO 311 I [55] 18 1-methyl-2-[6-carbonyl-(E)-7-undecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C21H27NO2 325 I [54] 19 1-methyl-2-dodecyl-4(1H)-quinolone C22H33NO 327 I [25,52] 20 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-5’-dodecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C22H31NO 311 I [52] 21 1-methyl-2-tridecyl-4(1H)-quinolone or Dihydroevocarpine C23H35NO 341 I [52] 22 Evocarpine C23H33NO 339 I [56]. 23 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-4-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H33NO 339 I [57] 24 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-7-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H33NO 339 I [30] 25 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-8-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H33NO 339 I [30] 26 1-methyl-2-[12-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H33NO 339 I [58] 27 1-methyl-2-[(4Z,7Z)-4,7-tridecadienyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H31NO 337 I [54] 28 1-methyl-2-[6-carbonyl-(E)-7-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H31NO2 353 I [30] 29 1-methyl-2-[7-carbonyl-(E)-8-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone (correct)

1-methyl-2-[7-carbonyl (E)-9-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone (reference)C23H31NO2 353 I [30] 30 1-methyl-2-[8-carbonyl-(E)-9-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H31NO2 353 I [30] 31 1-methyl-2-[9-carbonyl-(E)-7-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C23H31NO2 353 I [52] 32 1-methyl-2-[7-hydroxy-(E)-8-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone (correct)

1-methyl-2-[7-hydroxy-(E)-9-tridecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone (reference)C23H33NO2 355 I [54] 33 1-methyl-3-[(7E,9E,12Z)-7,9,12-pentadecadienyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H33NO 363 I [59] 34 1-methyl-3-[(7E,9E,11E)-7,9,11-Pentadecadienyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H33NO 363 I [59] 35 1-methyl-2-(13-hydroxy-tridecenyl)-4(1H)-quinolone C23H35NO2 357 I [30] 36 1-methyl-2-tetradecyl-4(1H)-quinolone C24H37NO 355 I [52] 37 1-methyl-2-[13-tetradecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C24H35NO 353 I [58] 38 1-methyl-2-pentadecyl-4(1H)-quinolone C25H39NO 369 I [52,60] 39 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-5-pentadecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H37NO 367 I [52] 40 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-6-pentadecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H37NO 367 I [54] 41 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-9-pentadecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H37NO 367 I [56] 42 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-10-pentadecenyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H37NO 367 I [56] 43 1-methyl-2-[(6Z,9Z)-6,9-pentadecadienyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H35NO 365 I [30,39] 44 1-methyl-2-[12-hydroxy-tridecyl]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H35NO2 381 I [58] 45 1-methyl-2-[(6Z,9Z,12Z)-6,9,12-pentadecatriene]-4(1H)-quinolone C25H33NO 363 I [55] 46 1-methyl-2-(15-hydroxy-pentadecenyl)-4(1H)-quinolone C25H39NO2 385 I [30] 47 1-methyl-2-hexadecyl-4(1H)-quinolone C26H41NO 383 I [58]. 48 2-nonyl-4(1H)-quinolone C18H25NO 271 I [61] 49 2-undecyl-4(1H)-quinolone C20H29NO 299 I [61] 50 2-tridecyl-4(1H)-quinolone C22H33NO 327 I [56] 51 1-methyl-2-[(6Z,9Z,12E)-pentadecatriene]-4(1H)- quinolone C25H33NO 363 I [58] 52 1-methyl-2-[(9E,13E)-9,13-heptadecadienyl]-4(1H)- quinolone C27H39NO 393 I [58] 53 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy-3-(3’-methyl-2’-butenyl)- quinolone C15H17NO2 243 I [62] 54 4-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-nonyl-quinolinium C19H27NO 285 I [63] 55 Atanine I C15H17NO2 243 II [33] 56 4-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)-2-quinolone-8-O-β-D-glucopyranoside C21H27NO8 421 II [53] 57 Quinolone B C21H27NO8 421 II [53] 58 3-Dimethylallyl-4-methoxy-2-quinolone C15H17NO2 244 II [64] 59 Edulinine C16H21NO4 291 II [65] 60 Dictamnine C12H9NO4 199 III [33,66,67] 61 6-methoxydictamnine C13H11NO3 229 III [33] 62 Evolitrine C13H11NO3 229 III [33,67] 63 Confusameline C12H13NO3 215 III [67] 64 Kokusaginine C14H13NO4 259 III [66] 65 Skimmianine C14H13NO4 259 III [23,25,33,67] 66 Haplophine C13H11NO3 229 III [68,69] 67 Robustine C12H9NO3 215 III [69] 68 7-isopentenyl-γ-fagarine C18H19NO4 313 III [65] 69 Melineurine C18H19NO4 313 III [70] 70 Leptanoine A C17H15NO3 281 III [71] 71 Leptanoine B C18H17NO4 311 III [71] 72 Leptanoine C C18H19NO4 313 III [71] 73 Evodine C18H19NO5 329 III [72] 74 Roxiamine A C18H19NO5 329 III [73] 75 Roxiamine B C18H17NO5 327 III [73] 76 Roxiamine C C16H27NO4 287 III [73] 77 Evoxoidine C18H19NO5 329 III [74] 78 Ribalinine C15H17NO3 259 IV [65] 79 1-hyddroxy-2,3-dimetoxy-10-methylacridone C16H15NO4 285 V [65] 80 2,3-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxy-10-methylacridone C16H15NO4 285 V [75] 81 2,3,4-trimethoxy-10-methylacridone C17H17NO4 299 V [76] 82 Xanthoxoline C15H13NO4 271 V [77] 83 Evoxanthidine C15H11NO4 269 V [77] 84 Xanthevodine C16H13NO5 299 V [77] 85 Melicopidin C17H15NO5 313 V [68] Table 3. Ring-integrating limonoids isolated from Euodia.

No. Limonoids Molecular formula Relative molecular mass Ref. 1 Limonin C26H30O8 470 [69,78−82] 2 12α-hydroxylimonin C26H30O9 486 [83−85] 3 6α-acetoxy-5-epilimonin (glaucin B) C28H32O10 528 [82,86] 4 6β-acetoxy-5-epilimonin C28H32O10 528 [87] 5 Jangomolide C26H28O10 500 [88] 6 Limonin diosphenol C26H28O9 484 [82−84] 7 Evodol (graucin C) C26H28O11 516 [78,80] 8 12α-hydroxyevodol C26H28O10 500 [80,89] 9 12α-hydroxyrutaevin (glaucinA) C26H30O10 502 [82] 10 Rutaevin C26H30O9 486 [80,82,90] 11 7β-acetoxy-5-epilimonin (ruteavine acetate) C27H32O10 516 [91] 12 Isolimonexic acid C26H30O10 502 [81] 13 Shihulimonin A1 C26H30O10 502 [78] 14 Evorubodinin C27H32O10 516 [59] 15 Evolimorutanin C28H36O11 548 [79] 16 Evodirutaenin A C26H29O11 517 [92] 17 Euodirutaecins A C26H28O11 516 [92] 18 Euodirutaecins B C26H28O11 516 [92] 19 Graucin A C26H30O10 502 [83] Table 4. Rearranged limonoids isolated from Euodia.

No. Limonoids Molecular formula Relative molecular mass Ref. 20 Obacunone C26H30O7 454 [91] 21 7-deacetylproceranone C25H29O5 409 [87] 22 Nomilin C29H38O9 530 [87] 23 Clauemargine L C26H34O7 458 [91] 24 19-hydroxy methyl isoobacunoate diosphenol C28H36O10 532 [91] 25 Obacunonsaeure C26H32O8 472 [91] Table 5. Degradable limonoids isolated from Euodia.

Quinazoline alkaloids

-

According to the ring splitting characteristics of the mother nucleus structure of quinazoline alkaloids in Euodia, the skeleton types can be divided into five categories (Fig. 1): Type I alkaloids (6/5/6/6/6 ring system) have complete A, B, C, D, E five ring mother nucleus structure, with evodiamine as the typical representative, which is most widely distributed in natural products; Type II is characterized by C-ring cleavage; Type III is characterized by D-ring cleavage; Type IV is characterized by C-D double ring cleavage, and type V is characterized by B-C double ring cleavage. The classification system is divided according to the differences of ring splitting sites. Type I complete mother nucleus structure is absolutely dominant, followed by type II single C ring splitting structure, and the rest types are relatively rare in nature. The structural characteristics of each subtype can be intuitively explained by the skeleton classification model shown in Fig. 2.

Quinolone alkaloids

-

So far, about 70 quinolone alkaloids have been isolated from Euodia. From the perspective of structural types, type I quinolone alkaloids are the most, with a total of 43. Among them, there are 40 quinolone alkaloids with R1 substituent of -CH3, and only three quinolone alkaloids without R1 substituent; five cases of type Type II; 18 cases of type III; one case of type IV; seven cases of type V. The structural characteristics of each subtype can be intuitively explained by the skeleton classification model shown in Fig. 3.

Limonoids from Euodia

Ring-integrating limonoids

-

Limonoids isolated from Euodia species predominantly feature a complete tetranortriterpenoid skeleton (A/B/C/D rings). Based on the functionalization of the C-17 side chain, these compounds are classified into two structural categories: 17β-furan limonoids and C17 Δα, β-unsaturated lactone limonoids. The former group includes evodol and limonin, which are renowned for their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, contributing to the medicinal value of Euodia plants. Notably, limonin (Entry 1, Table 3) is a prototypical limonoid with a molecular formula of C26H30O8 and a relative molecular mass of 470. Structural modifications such as hydroxylation (12α-hydroxylimonin, Entry 2) or acetylation (6α-acetoxy-5-epilimonin/glaucin B, Entry 3) enhance structural diversity and bioactivity. Glaucin A (C26H30O10), a furan-bearing limonoid, exemplifies the role of the furan ring in stabilizing the molecular framework and modulating bioactivity.

Table 3 summarizes 19 ring-integrating limonoids, highlighting key derivatives such as rutaevin (Entry 10) and evolimorutanin (Entry 15). The latter, with a molecular formula of C28H36O11, demonstrates the complexity introduced by additional oxygen-containing functional groups. Recent studies emphasize the pharmacological potential of these compounds, including anti-tumor, neuroprotective, and antiplatelet aggregation activities.

Rearranged limonoids

-

Rearranged limonoids represent the second-largest group in Euodia, characterized by structural modifications such as ring condensation, alkyl migration, and aromatization. These rearrangements yield two subtypes: split-ring and non-split-ring limonoids. Obacunone (Entry 20, C26H30O7) is a prominent example, known for its role as a biosynthetic precursor to other limonoids. Its derivative, obacunonsaeure (C26H32O8), further illustrates the metabolic flexibility of this class.

Table 4 lists six rearranged limonoids, including nomilin (Entry 22) and clauemargine L (Entry 23). These compounds often exhibit enhanced bioactivity due to their unique stereoelectronic configurations. For instance, obacunone derivatives demonstrate potent cytotoxic effects against colon cancer cells by inducing apoptosis.

Degradable limonoids

-

Degradable limonoids, primarily isolated from E. rutaecarpa fruits, retain a tetranortriterpene core with a stable 17β-furan ring. These compounds arise from environmental degradation, preserving bioactive fragments of the parent limonoids. Hiiranlactone E (Entry 27) and 9α-methoxy dictamdiol (Entry 26) are notable examples, though their pharmacological profiles remain under investigation.

-

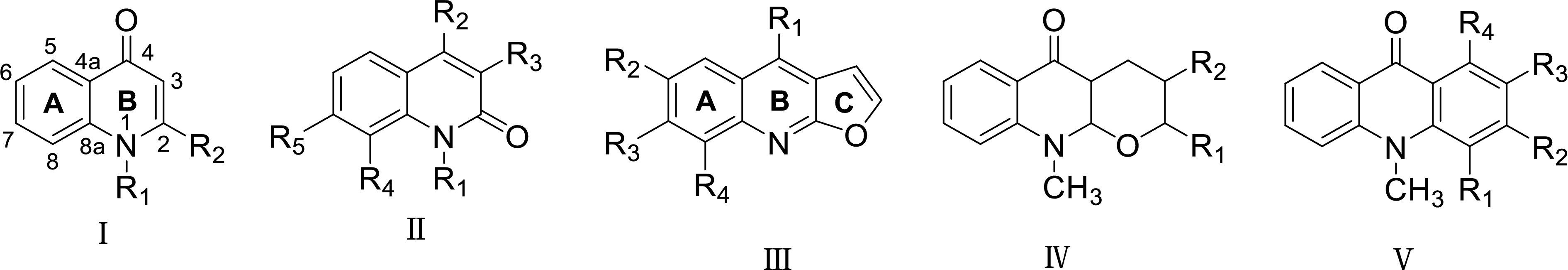

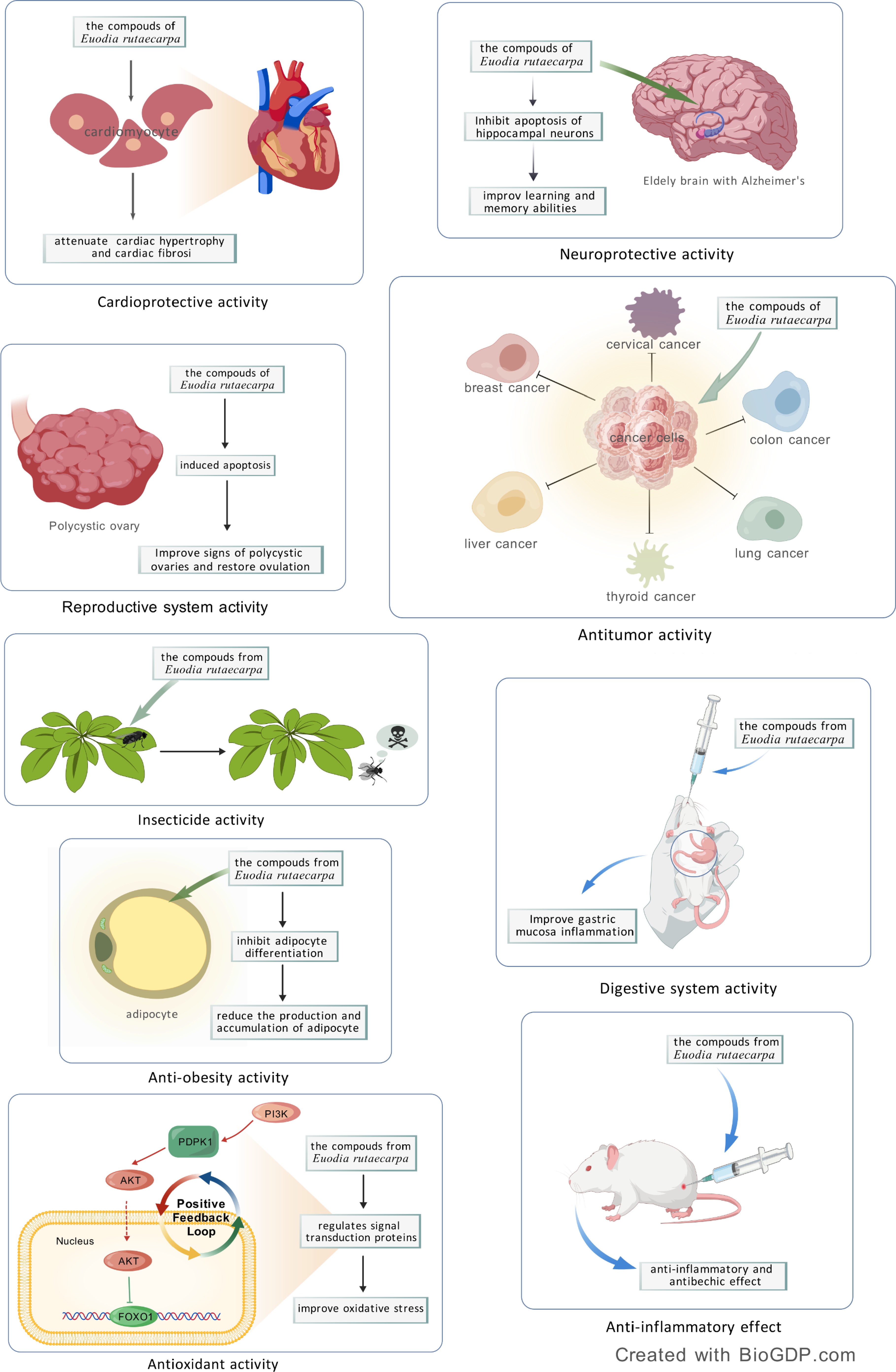

The clinical application of E. rutaecarpa is largely attributed to its rich chemical composition, which serves as a crucial pharmacological foundation. As science and technology have advanced, researchers have delved into the pharmacological effects of E. rutaecarpa across multiple dimensions. Their findings reveal that this plant exhibits a wide range of biological activities, including anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as effects on the digestive, cardiovascular, and central nervous systems (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Pharmacological effects of Euodia rutaecarpa: cardioprotective activity, neuroprotective activity, reproductive system activity, anti-tumor effect, insecticide activity, anti-obesity activity, antioxidant activity, digestive system activity, anti-inflammatory effect.

Anti-tumor activity

-

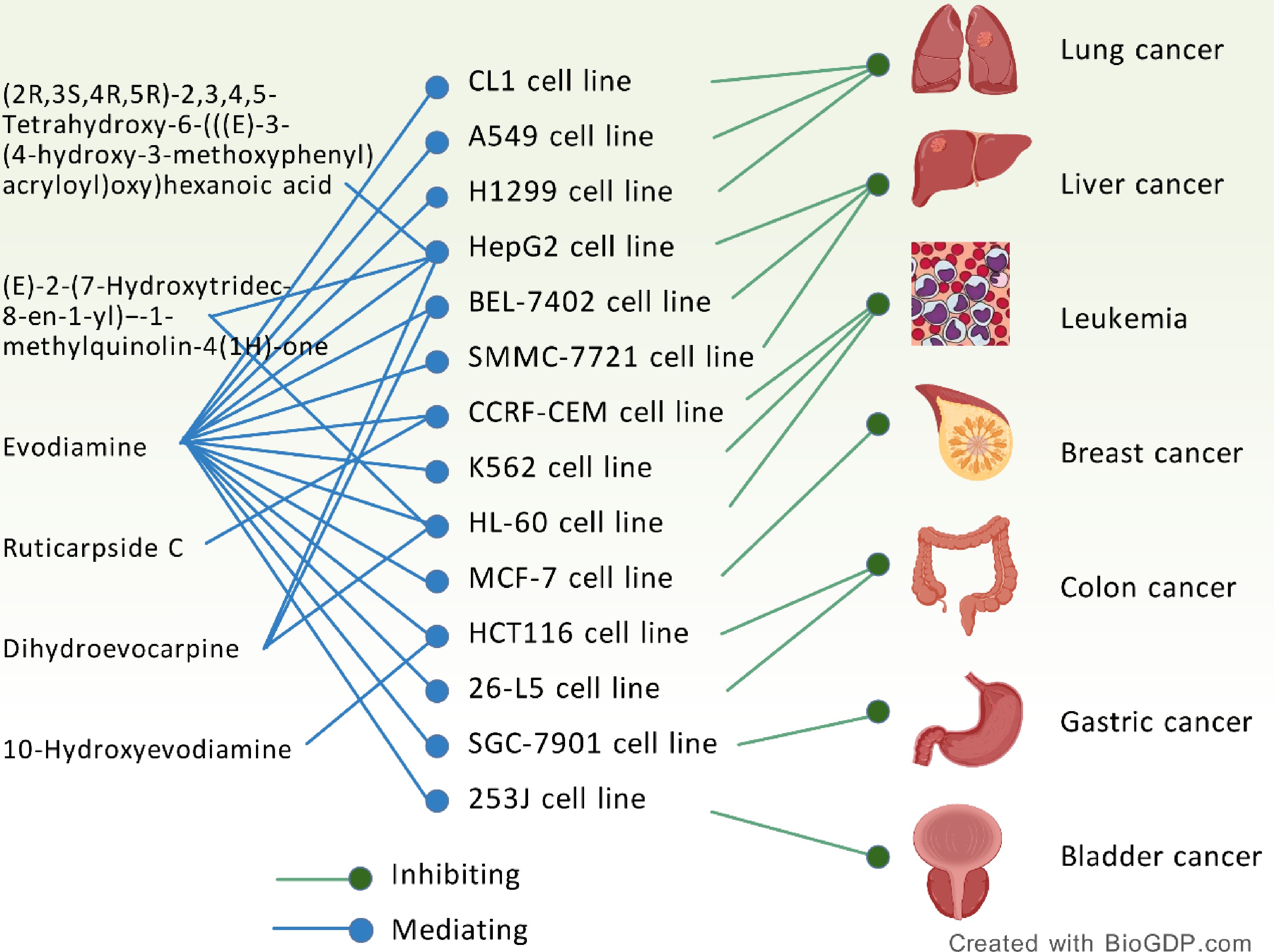

A variety of experimental studies have proved that evodiamine (Evo) is a multi-target anti-tumor drug, which has a positive effect on breast cancer[93−95], liver cancer[96−99], lung cancer[100,101], colon cancer[102−104], human melanin[105−107], cervical cancer[108], thyroid cancer[109,110], pancreatic cancer[111], bladder[112], prostate cancer[113], leukemia[5,114], gastric cancer[115,116], glioblastoma[117], urothelial cell carcinoma[118], ovarian epithelial carcinoma[119], cholangiocarcinoma[120], osteosarcoidoma[121], and oral cancer[122] all have therapeutic significance.

According to the published literature, the abnormal process of apoptosis and tumor occurrence and development are closely related. The most obvious characteristic of the process of tumorigenesis is cell apoptosis[123]. A large number of studies have shown that Evo has effects of anti-angiogenesis, inhibition of invasion and metastasis, which can inhibit tumor growth and metastasis[12] (Fig. 5).

Cytotoxicity on malignant melanoma

-

The cytotoxicity of Evo on A375-S2 cells inhibits cell proliferation. Existing research has demonstrated that the accumulation of intracellular oxidative stress mediators and alterations in mitochondrial membrane integrity play a critical role in mediating the pro-apoptotic effects triggered by Evo administration in A375-S2 human melanoma cell lines. Specifically, experimental evidence reveals that sustained generation of oxygen-derived free radicals coupled with compromised mitochondrial transmembrane potential constitutes a pivotal molecular mechanism underlying this phytochemical-induced programmed cell death pathway[124]. Evo significantly enhances the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) via the iNOS enzyme. Moreover, the production of NO has been reported to trigger apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by activating the p53 and p21 pathways[106]. Dehydroevodiamine (Dehy) exhibited inhibitory effects on B16F10 melanoma cells. However, this effect was mainly attributed to the direct inhibition of tyrosinase activity, rather than through the suppression of tyrosinase gene expression[125].

Effects on ovarian cancer

-

Evo is anti-proliferative in human multiple-drug NCI/ADR-RES cells by activating caspase-7 and 9 in apoptosis, which also promoted the phosphorylation of Raf-1 kinase and Bcl-2, and induced cell cycle progression arrest at the G2/M phase[126,127]. Park et al. certified that the apoptotic activity of an ethanol extract derived from immature fruits of E. rutaecarpa may be linked to a caspase-dependent cascade, mediated through the activation of the intrinsic signaling pathway involving AMPK[128].

Effects on human epithelial ovarian cancer cells

-

Zhong et al. suggested that Evo demonstrated significant anti-proliferative activity against human epithelial ovarian cancer cells, inducing G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and enhancing chemoresistance[129]. The research by Wei et al. indicated that the PI3K/Akt, ERK1/2 MAPK, and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, which are activated by Evo, might play a role in cell death. Additionally, Evo has the capacity to suppress the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells through mechanisms involving G2/M phase arrest and both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways[130]. Data indicate that the apoptotic effects of Evo are mediated through the activation of JNK and PERK pathways, which in turn lead to the disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). Additionally, the presence of an alkyl group at position 14 is recognized as a vital structural determinant for its pro-apoptotic activity[131].

Effects on breast cancer

-

Wang et al. found Evo may inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation through ER-inhibitory pathway, as Fig. 4[132]. Furthermore, Evo, featured with CSLC-specific targeting, selectively activates p53 and p21 and reduces the inactive Rb of major molecules in the G1/S assay site, which may be used in breast cancer treatment[133].

Effects on human colon cancer

-

Colon cancer is a prevalent malignant tumor with an incidence rate that has been rising annually. In COLO-205 cells, Evo has been shown to arrest the cell cycle at the G2/M phase. This effect is associated with decreased expression of Bcl-2, increased expression of Bax and p53, reduced mitochondrial transmembrane potential, activation and of caspase-3[134]. Additionally, Evo has been confirmed to inhibit the proliferation of human COLO cells by reducing the expression of procaspase-8, 9, and 3, and by inducing S phase arrest. Furthermore, Evo may downregulate the expression of HIF-1α and inactivate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through decreased expression of IGF-1 in colon cancer cells[135].

Effects on lung carcinoma

-

Studies have demonstrated that Evo exerts anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects on four wild-type EGFR non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines[136]. Comprehensive mechanistic dissection in A549 non-small cell lung carcinoma models elucidated multifaceted growth regulatory pathways mediated through redox homeostasis disruption and programmed cell death activation. Functional genomics profiling demonstrated concomitant G0/G1 phase blockade via p21WAF1/CIP1 upregulation and caspase-3-dependent apoptotic execution, paralleled by dual signaling axis modulation involving phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT/nuclear factor-kappa B (PI3K/AKT/NF-κB) survival pathways and Sonic Hedgehog/GLI1 (SHH/GLI1) developmental cascades[100]. Lu et al. demonstrated that Evo inhibited LLCCs growth and induced apoptosis through caspase-independent manner in vitro and caspase-dependent pathway in vivo[137].

Effects on hepatocellular carcinoma

-

Evo blocked STAT3 signaling pathway by inducing SHP-1 and showed anticancer effect in HCCs[138]. Evo inhibited the TPA-induced AP-1 activity and cellular transformation in human hepatocytes via the ERKs pathway[139]. Furthermore, the concurrent application of berberine and Evo has been shown to markedly increase apoptosis in SMMC-7721 cells, a finding that holds significant promise for advancing anti-cancer therapies and related research[140].

Effects on gastric cancer

-

Experimental interrogation of gastric carcinoma SGC-7901 cellular models demonstrated evodiamine's potent antiproliferative efficacy through dual mechanistic interventions. Cell cycle profiling via flow cytometry revealed significant G2/M phase arrest, mechanistically associated with cyclin B1/CDK1 complex dysregulation. Furthermore, programmed cell death initiation was confirmed through proteolytic activation of executioner caspases (-3, -8, -9), accompanied by mitochondrial apoptotic pathway modulation evidenced through immunoblot quantification showing 2.3-fold Bax/Bcl-2 ratio elevation and subsequent cytochrome c release, ultimately triggering caspase-dependent apoptotic cascade in treated neoplastic populations[141,142]. Another possible mechanism might be that Evo stimulates upregulation of aSMase expression and hydrolysis of sphingomyelin into ceramide[115]. Mechanistic investigations revealed that the combinatorial regimen of berberine and d-limonene induced cooperative tumor-suppressive responses in gastric adenocarcinoma MGC-803 models, mediated through tripartite therapeutic mechanisms. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated G1/S phase blockade via cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor upregulation, accompanied by dose-dependent reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction exceeding 2.1-fold compared to monotherapy. Notably, mitochondrial permeability transition studies confirmed apoptosis potentiation through Bcl-2/Bax axis modulation, with immunoblotting verifying caspase-9/-3 cascade activation, collectively establishing the phytochemical combination as a potent inducer of intrinsic apoptotic signaling in vitro[143].

Anti-invasive and anti-metastatic

-

Pharmacological evaluations across multiple murine tumor models (Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), B16-F10 melanoma, and colon 26-L5 carcinoma systems) demonstrated evodiamine's significant dual inhibitory capacity against neoplastic invasion and metastatic dissemination[144]. It can down the expression of MMP-9, uPA, and uPAR, which can decrease Bcl-2, cyclin D1, and CDK6 expression, and increase in Bax and p27Kip1 expression in vitro[132]. Rutaecarpine(Rut) exerts protective effects against ox-LDL-induced monocyte adhesion by enhancing Cx expression and restoring hemichannel function, mediated through TRPV1 activation[145].

Shi et al. reported that Evo exhibited a potential tendency to enhance the metastasis of gastric cancer cells, primarily through the upregulation of IL-8 secretion and the modulation of adhesion molecules, and functional analyses revealed that Evo significantly attenuated hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-induced activation in malignant cells, particularly manifesting as diminished neoplastic motility and invasive potential[146].

Other anti-tumor activity

Inhibit the proliferation of leukemia

-

Leukemia is a common malignancy of the blood system. According to the MTT assay, Evo-induced apoptosis in CCRF-CEM cells through a caspase-3-dependent signaling pathway[147]. Adams et al. reported that Rut and Evo were weak modulators of P-gP activity in CCRF-CEM leukemia cells[148]. Mechanistic investigations further revealed evodiamine's dual pharmacological actions, demonstrating selective binding affinity for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), and exhibiting agonistic activity. Importantly, transcriptomic profiling identified the PPARγ signaling cascade as a critical mediator underlying Evo-induced growth suppression in chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cell models. This tumor-suppressive effect appears mechanistically linked to cell cycle regulatory modulation, manifested through coordinated downregulation of cyclin D1 expression concomitant with transcriptional upregulation of p21CDKN1A, ultimately culminating in G1 phase arrest[149,150].

Attenuate multidrug resistance

-

Evo functions as a dual inhibitor targeting topoisomerases I and II, and it exhibits enhanced inhibitory effects on camptothecin-resistant cells[32,151]. In a groundbreaking study focused on colorectal carcinoma pathogenesis, researchers led by Sui et al. demonstrated for the first time that Evo effectively suppresses multidrug resistance phenotypes through selective inhibition of phosphorylated nuclear factor-kappa B signaling transduction. This seminal discovery, documented in human colorectal cancer cell models, reveals a novel therapeutic mechanism wherein Evo-mediated blockade of NF-κB activation cascade significantly compromises cancer cell adaptive resistance mechanisms in vitro[152].

Photo-sensitive agent

-

The photocytotoxicity effect of Evo is that Evo inhibits PI3K/AKT/mTOR phosphorylation and increases p38 phosphorylation[153]. Emerging evidence positions Evo as a promising photosensitizing candidate in photodynamic therapy (PDT) for neoplastic diseases.

Discussion 1: Fig. 5 reveals the potential value of E. rutaecarpa in cross-cancer studies. The multi-target cell models listed in this paper suggest that these compounds may have broad-spectrum anti-tumor activity, and the dual mechanisms of 'inhibition' and 'mediation' may reflect their effects through the regulation of key pathways. Such studies may provide a new direction for the development of low-toxicity and highly selective anti-cancer drugs, but further verification of their efficacy and mechanism specificity in vivo is required.

Anti-inflammatory activity

-

E. rutaecarpa has been used for treating inflammatory-related disorders. According to the research by Moon et al., the anti-inflammatory properties of E. rutaecarpa are partly due to the inhibition of COX-2 expression[154]. Furthermore, in vivo study verified that Rut is a selective COX-2 inhibiter, which possesses anti-inflammatory activity on rat λ-carrageenan paw edema[155]. Choi et al. and Noh et al. proposed that the inhibitory impact of Dehy on the expression of LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 genes is primarily due to its ability to suppress NF-κB activation at the transcriptional level[156,157]. The study by Chiou et al. demonstrated that both Dehy and Evo inhibited NO production in IFN-γ/LPS-stimulated RAW macro-phages in a concentration-dependent manner[158]. Evo effectively reduced inflammatory response via blocking calcium influx and NF-κB pathway, decreasing the level of E-selectin[8].

Contemporary pharmacological investigations have demonstrated Evo exhibits significant mucosal preservation capacity in ethanol-induced gastric mucosal lesions. Mechanistic dissection revealed this cytoprotective efficacy operates through dual regulatory axes: (1) redox homeostasis restoration via superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) upregulation, and (2) inflammatory cascade suppression through RhoA/ROCK/NF-κB signaling axis modulation. Histomorphometric analysis confirmed 89.7% reduction in ulcer indices, concomitant with decreased myeloperoxidase activity and COX-2/iNOS expression patterns. Molecular docking simulations further identified high-affinity binding (−9.3 kcal/mol) between Evo and ROCK2 catalytic domain, suggesting direct pathway intervention[159,160]. In addition to its other effects, Evo may exert anti-inflammatory effects in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) under high-glucose conditions through the inhibition of the P2X4R signaling pathway. This action demonstrates its potential to protect HUVECs from glucotoxicity-induced damage[161,162] (Table 6).

Table 6. Anti-inflammatory activity.

Discussion 2: The anti-inflammatory effect of E. rutaecarpa is mainly realized through its alkaloid components (such as Evo) inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators and inflammatory signaling pathways. However, its specific mechanism still needs to be further elucidated. Although it has been shown to have significant anti-inflammatory effects in vivo and in vitro models, its clinical translational potential and long-term safety need to be further investigated.

Effects on the digestive system

Protective effect on gastric mucosa injury

-

Pharmacological evaluation of Rut revealed significant gastroprotective activity in experimental models of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)-associated and stress-related mucosal lesions. Mechanistic interrogation demonstrated this cytoprotection originates from TRPV1 channel agonism-dependent evoked secretion of endogenous calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), as confirmed by complete abolishment of protective effects following pre-treatment with selective TRPV1 antagonists in controlled intervention studies[163]. Novel bioadhesive drug delivery systems encapsulating plant-derived alkaloid compounds demonstrated significant mucosal protection in experimental ethanol-induced gastropathy models. Mechanistic investigations revealed this cytoprotective efficacy involves dual anti-inflammatory pathways: (1) suppression of TNF-α/IL-6-mediated inflammatory cascades, and (2) inhibition of myeloperoxidase-positive leukocyte accumulation. Histopathological analyses confirmed preserved mucosal integrity with decreased hemorrhagic lesions, concomitant with downregulation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway activation in treated specimens[164].

Effects on gastrointestinal motility

-

Evo affects gastrointestinal transit, when administration of Evo, both gastrointestinal transit and gastric emptying were inhibited, and the mechanism involved the CKK release and CKK1 receptor activation[165]. Evo can also enhance normal jejunal contractility and improve hypercontractility in the jejunum under various experimental conditions. These effects are calcium-dependent, require the presence of interstitial cells of Cajal, and involve cholinergic neurons. Additionally, they are associated with increased myosin phosphorylation[13] (Table 7).

Table 7. Effects on the digestive system.

Activities Mechanism of action Signaling pathway Ref. Protective effect of gastric mucosa injury Stimulation of CGRP release TRPV1 [163] Reducing the inflammatory response [164] Effects on gastrointestinal transit Inhibiting gastrointestinal transit and gastric emptying CKK, CKK1 receptor [165] Increasing normal jejunal contractility [13] Discussion 3: E. rutaecarpa has many significant effects on the digestive system, and its effects of anti-ulcer, regulation of gastrointestinal function, anti-diarrhea, and anti-vomiting have been confirmed by many studies. Its mechanism may be related to inhibiting gastric acid secretion, protecting gastric mucosa, and regulating gastrointestinal motility. However, the specific mechanism of action of E. rutaecarpa still needs to be further studied to clarify its best application and potential risks in the treatment of digestive system diseases and to provide a more reliable basis for its clinical application.

Effects on the cardiovascular system

Positive inotropic and chronotropic effects

-

The crude acetone extract derived from the fruits of E. rutaecarpa exhibited a positive inotropic effect on isolated left atria from guinea pigs[166]. Electrophysiological investigations by Yoshinori's research group[167] documented that Rut and Evo elicit biphasic cardio stimulatory responses in ex vivo guinea pig atrial preparations. The initial phase manifested as transient enhancement of myocardial contractility (positive inotropy) and heart rate acceleration (positive chronotropy), succeeded by progressive refractoriness to subsequent dosing. Mechanistic analyses revealed this pharmacodynamic profile originates from TRPV1 receptor agonism-mediated calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release modulation, as evidenced by complete response abolition through selective CGRP receptor antagonism in parallel control experiments[168].

Anti-hypertensive

-

E. rutaecarpa extracts were investigated for their in vitro effect on anti-hypertensive activities, including NO production and ACE activity[169]. Research work has demonstrated that Evo demonstrates a potential anti-atherogenic effect by activating PPAR, which in turn inhibits the migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)[170,171]. Experimental investigations into Evo demonstrated its cardioprotective efficacy against isoproterenol-triggered myocardial fibrosis. Mechanistically, this protection arises from Evo's suppression of endothelial-mesenchymal transition (End MT), a process critically regulated through targeted inhibition of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling axis. Cellular-level analyses confirmed dose-dependent attenuation of Smad2/3 phosphorylation, accompanied by reduced nuclear translocation of transcriptional regulators, suggesting dual-level interference with profibrotic signaling cascades[172]. In vitro studies demonstrate that Rut mitigates vascular endothelial injury induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein (Ox-LDL), thereby exerting a protective role. Mechanistically, Rut preserves gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) functionality through TRPV1 channel agonism, which modulates connexin isoform redistribution. Experimental validation using pharmacological inhibition confirmed TRPV1-dependent restoration of Cx43 membrane localization, accompanied by significant attenuation of pathological ZO-1 disassembly in endothelial monolayers exposed to atherogenic stimulation[173].

Anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic activities

-

Evo has the ability to directly suppress tube formation and invasive capacity of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro, by inhibiting the gene expression of VEGF and the p44/p42 MAPK, ERK that correlated with endothelial cells angiogenesis[174].

Rut was examined for its antiplatelet activity in human platelet-rich plasma, possibly by mechanisms involving the inhibition of thromboxane formation and phosphoinositide breakdown[11,166].

Vasodilatory effect

-

Dehy, Evo, and Rut were shown to exert vasodilatory effects on endothelium-intact rat aortas with comparable potency[166,175]. Pharmacological analyses of Dehy, Rut and Evo revealed dual mechanisms underlying their vasodilatory effects. Primarily, these alkaloids enhanced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity, promoting endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) production. Concurrently, they exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of receptor-operated calcium entry (ROCE) in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) through G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling modulation. Electrophysiological assessments confirmed significant blockade of voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) in VSMCs, with complete reversibility upon compound washout[176].

Anti-arrhythmic

-

In cardiac tissues derived from human atrial and ventricular specimens, the alkaloid compound Dehy demonstrated significant inhibitory effects on myocardial electrophysiological parameters. Experimental observations revealed a concentration-dependent suppression of action potential amplitude (APA) and maximum upstroke velocity (Vmax) in both fast-response and slow-response myocardial preparations. The compound concurrently attenuated myocardial contractility in these experimental models. Furthermore, voltage-clamp analyses demonstrated that Dehy exerted reversible and dose-dependent inhibition on both voltage-gated sodium channels (INa) and L-type calcium channels (ICa-L) in isolated human cardiomyocytes from atrial and ventricular origins[177]. The resting pHi and NHE activity were also significantly increased by Dehy[178].

Vascular disease

-

In vitro studies by Ge et al.[179] showed that Evo attenuates the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) stimulated by human platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) in a dose-dependent fashion, but does not induce cell death, and has potential value in the treatment of vaso-occlusive diseases, and its mechanism is related to the fact that Evo can attenuate the phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Wang et al.[180] found Evo can directly bind to ABCA1 (adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter A1 antibody) to promote the reverse transport of cholesterol, which provides a basis for the treatment of atherosclerosis with Euodia.

Protective effect against valvular heart disease

-

Calcific aortic valve stenosis, a type of heart valve disease, can be triggered by hyperphosphatemia. Mechanistic investigations by Seya's[181] research team demonstrated that the quinolone derivative 1-methyl-2-undecyl-4(1H)-quinolinone selectively downregulated the sodium-dependent phosphate transporter PiT-1 isoform, while showing no regulatory effect on PiT-2 expression. This compound significantly attenuated pathological calcification in human aortic valve interstitial cells under hyperphosphatemia conditions (3.2 mM). Furthermore, structure-activity relationship analyses suggested that C-2 substituent modifications in quinolone alkaloid derivatives could substantially modulate their anti-calcification efficacy (Table 8).

Table 8. Effects on the cardiovascular system.

Activities Mechanism of action Signaling pathway Ref. The positive inotropic and chronotropic effects Vanilloid receptors, the calcitonin gene related peptide antagonist [166,168] Anti-hypertensive Attenuation of VSMC migration PPAR [170,171] Regulating endothelial to mesenchymal transition The transforming growth factor-beta1/Smd [173] Anti-platelet and anti-thrombotic activities Inhibiting HUVECs tube formation and invasion VEGF, p44/p42, MAPK, ERK [174] Inhibiting thromboxane formation and phosphoinositide breakdown [11,166] The vasodiatory effect Endothelium, receptor-mediated Ca2+ channels [176] Anti-arrhythmic Decreasing the Na+ and Ca2+ currents [177] Vascular disease Attenuate the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase promote the reverse transport of cholesterol VSMCs

ABCA1[179]

[180]Protective effect against valvular heart disease Decrease the expression of phosphate cotransporter PiT-1 [181] Discussion 4: The effect of alkaloids from E. rutaecarpa on the cardiovascular manifestations of the main manifestations of positive and variable effects, anti-hypertensive, anti-platelet, and anti-thrombotic activity, vasodilator, antiarrhythmic, and so on. However, its bidirectional regulatory effect and potential toxicity still need to be further studied to ensure the safety and efficacy of clinical use.

Effect on the central nervous system

Anti-Alzheimer's disease

-

Park et al. reported that Dehy possesses novel anticholinesterase and antiamnesic activities and may serve as a therapeutic agent for Alzheimer's disease (AD) by acting as a beta-secretase inhibitor[182,183]. Additionally, the heptyl carbamate derivative of 5-deoxo-3-hydroxyevodiamine demonstrated significant potency, with an IC50 value of 77 nM. This compound exhibited high selectivity for its target compared to acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and provided substantial neuroprotective effects, observable at concentrations as low as 1 mM[184]. The new findings indicate that Evo possesses neuroprotective effects against okadaic-acid-induced tau pathology. Evo treatment significantly inhibited tau phosphorylation on Ser202/Thr205, Ser262, and Ser396 and downregulated tau aggregation and neuronal cell apoptosis. Evo treatment ameliorated learning and memory impairments in vivo, downregulated tau phosphorylation, and attenuated neuronal loss in mice brains[185].

Anti-anoxic and anti-cerebral ischemia activities

-

Methanol extract from a Chinese medicine E. rutaecarpa had a substantial impact on the KCN-induced anoxia model in mice, with the active components identified as Evo and Ru for further investigation[186]. The comparative pharmacological evaluation revealed differential neuroprotective profiles between evodiamine and vinpocetine across hypoxic paradigms. In murine models of potassium cyanide-induced acute anoxia, both compounds demonstrated comparable efficacy in neurological preservation. However, under hypobaric hypoxia challenge conditions, Evo exhibited superior therapeutic potential over vinpocetine in maintaining cerebral oxygen homeostasis[153].

Evo provided significant neuroprotection against ischemic damage caused by permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (pMCAO). This neuroprotective action may be attributed to the upregulation of pGSK3β and pAkt, as well as the stabilization of claudin-5, while simultaneously downregulating the expression of NF-κB[187].

Analgesic effect

-

Mechanistic studies have revealed that Evo exerts analgesic properties through neuronal desensitization pathways. Investigations by Kobayashi demonstrated that ex vivo ileal preparations from Evo administered rodents exhibited abolished responsiveness to capsaicin-induced sensory neuron activation while maintaining preserved contractile capacity upon carbachol-mediated parasympathetic stimulation[188]. Recently, Iwaoka et al. suggested that the analgesic effects of EF and Evo might result from the activation and subsequent desensitization of TRPV1 in sensory neurons[16].

Antidepressant effect

-

Evo shows a potential antidepressant effect on CUMS rats, and its potential mechanism may be associated with its regulation of monoamine emitters and hippocampal BDNF-TrkB signaling[189] (Table 9).

Table 9. Effect on the central nervous system.

Activities Mechanism of action Ref. Anti-Alzheimer's disease Beta-secretase inhibitor [182,183] Selectivity over AChE, strong neuroprotection [184] Inhibited tau phosphorylation on Ser202/Thr205, Ser262, and Ser396 and downregulated tau aggregation and neuronal cell apoptosis. [185] Anti-anoxic and

anti-cerebral ischemia activitiesEquivalent to vinpocetine [153] Upregulation of pGSK3b, pAkt, and claudin-5, and downregulation of NF-kB expression [187] Analgesic effect The activation and subsequent desensitization of TRPV1 [16] Antidepressant effect Monoamine emitters and hippocampal BDNF-TrkB signaling [189] Discussion 5: E. rutaecarpa also has anti-Alzheimer's, anti-cerebral ischemia, analgesic, and antidepressant effects. The mechanisms involved in the regulation of inflammatory factors, oxidative stress, and signaling pathways provide potential directions for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and anxiety disorders.

Other biological activities

Anti-lipogenic and anti-gluconeogenic effects

-

Rut and Evo were found to display anti-lipogenic and anti-gluconeogenic activities in HepG2 cells under hyperlipidemic conditions[190]. Pharmacological investigations revealed OFF exerts insulinotropic action through direct modulation of pancreatic β-cell function in streptozotocin-challenged diabetic rodents. This therapeutic intervention demonstrated tripartite therapeutic efficacy: (1) restoration of glucose homeostasis via enhanced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), (2) normalization of dyslipidemia and hepatic transaminase abnormalities, and (3) attenuation of diabetes-associated pathologies including nephropathy and retinopathy. Mechanistically, calcium imaging confirmed OFF-enhanced Ca2+ influx potentiated insulin granule exocytosis, while intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (IPGTT) verified sustained glycemic control[191].

There have been reports that they were able to ameliorate hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia by regulating IRS-1/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in liver and AMPK/ACC2 signaling pathway in skeletal muscles[190], or by enhancing the assembly of high-molecular-weight (HMW) adiponectin, thereby activating AMPK and increasing the HMW-to-total adiponectin ratio in 3T3-L1 adipocytes[192], or to suppress adipogenesis through the EGFR-PKCα-ERK signaling cascade[193], or by suppressing the mTOR-S6K signaling pathway and serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) in adipocytes[194], or partially through the downregulation of NPY and AgRP mRNA and peptide expression within the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the rat hypothalamus[195].

Effect on the immune system

-

Evo can augment the antiviral immune response in shrimp via caspase-dependent apoptosis mediated by small molecules in vivo[15]. The experimental results demonstrated that both Evo and Rut exhibited significant inhibitory effects on TNF-α and IL-4 cytokine production in IgE-mediated antigen-activated RBL-2H3 mast cells. Notably, however, neither compound showed suppressive activity against β-hexosaminidase release in two distinct degranulation models: IgE-dependent RBL-2H3 cell activation and compound 48/80-induced rat peritoneal mast cell responses[196].

Anti-microbial

-

Evo blocked the relaxation of supercoiled plasmid DNA catalyzed by E. coli topoisomerase I and exhibited a substantially lower minimal inhibitory concentration[197]. The attenuation of antimycobacterial efficacy observed in quinolone alkaloid Evo appears to correlate with molecular interactions involving indoloquinazoline alkaloids. Experimental evidence suggests that these heterocyclic compounds may form stable molecular complexes with Evo, potentially through π-π stacking interactions, which could substantially diminish the therapeutic potential of the quinolone derivative against mycobacterial pathogens. This molecular association mechanism might explain the significant reduction in antimicrobial activity documented in combinatorial treatment assays[10].

Hepatic alcohol metabolizing

-

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) remains the leading cause of chronic liver disorders globally. Among the various pathogenic mechanisms, inflammatory response and oxidative stress are pivotal in mediating alcohol-induced liver injury (ALI). Recent pharmacological research has focused on RUT, a flavonoid with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Evidence suggests that RUT may attenuate alcohol-induced hepatic injury by modulating the NF-κB/COX-2 signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting inflammatory responses and oxidative stress[198].

Protect ovary cells

-

Experimental investigations reveal that Euodiae Fructus exerts cytoprotective effects on ovarian cells exposed to VCD-induced toxicity, with mechanistic studies suggesting Akt signaling pathway activation as a potential mediator[199]. These findings indicate its therapeutic potential in mitigating environmentally-associated ovarian dysfunction, particularly premature ovarian insufficiency and idiopathic fertility disorders.

Toxicity

-

The hepatotoxic effects induced by the volatile oil of Euodiae Fructus are primarily attributed to oxidative damage mechanisms, which are closely associated with the inhibition of pain neurotransmitter release, peroxidative damage, and nitric oxide (NO)-mediated toxicity[18]. Furthermore, the molecular pathways underlying E. rutaecarpa-induced hepatotoxicity potentially involve key signaling molecules, including Erkl/2, CDK8, CKle, Stat3, and Src, which may play significant roles in mediating these toxicological responses. E. rutaecarpa has a long history and a wide range of pharmacological effects. Its toxicity is also recorded in ancient classic works on materia medica.

Natural insecticide

-

Previous research[200] has demonstrated that Evo exhibits significant pesticidal efficacy against Mythimna separata, inducing physiological responses comparable to those observed following treatment with the ryanodine receptor (RyR)-targeting insecticide chlorantraniliprole. The characteristic toxic manifestations include complete feeding cessation, progressive muscular dysfunction, and systemic dehydration accompanied by body mass reduction.

-

E. rutaecarpa, a traditional Chinese medicine with abundant resources, has been widely used clinically and possesses a long history of application. Its chemical composition is highly diverse, primarily consisting of alkaloids and limonoids. However, current research on this plant predominantly centers on a few key components, such as Dehy, Evo, and Rut. In contrast, the pharmacological effects and mechanisms of action of the remaining chemical constituents remain relatively unexplored and require further in-depth investigation.

While the clinical efficacy of E. rutaecarpa has been partially validated, most existing studies are still restricted to animal and cellular levels. Therefore, future research should prioritize elucidating the pharmacological actions and underlying mechanisms of E. rutaecarpa. Conducting large-scale, randomized controlled clinical trials and performing systematic evaluations would significantly advance its clinical applications and facilitate the development of new drugs derived from this plant.

Future research on the chemical components and pharmacology of E. rutaecarpa should focus on the following directions: First, a comprehensive investigation into the pharmacological effects and mechanisms of other potential active components is essential to fully understand the scientific basis of its biological activities and provide robust theoretical support for clinical applications. Second, efforts should be intensified to develop and utilize E. rutaecarpa more effectively. Structural modifications of its toxic components could enhance efficacy while reducing toxicity. Additionally, designing various drug delivery systems tailored to its characteristics could lead to the development of novel formulations. This approach would not only mitigate the toxic and side effects of E. rutaecarpa but also broaden its clinical applicability, thereby maximizing its medicinal value.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32370424), and the Forestry Science and Technology Popularization Demonstration Project of the central finance (SU [2024] TG11), and the Jurong Science and Agricultural Technology Innovation Project (ZA32311).

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wang Q, Zhao W; data collection: Xu X, Chen J, Liang W; analysis and interpretation of results: Liang W, Xu S; draft and revised manuscript preparation: Xu X, Chen J, Zhao W, Wang Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Xiaoxiao Xu, Junjie Chen

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xu X, Chen J, Liang W, Xu S, Zhao W, et al. 2025. Review on chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of genus Euodia. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e019 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0014

Review on chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of genus Euodia

- Received: 01 March 2025

- Revised: 11 April 2025

- Accepted: 22 April 2025

- Published online: 25 June 2025

Abstract: Euodia rutaecarpa (Juss.) Benth., commonly known as Wu Zhu Yu in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), is a widely used medicinal plant belonging to the Rutaceae family. With a rich history spanning thousands of years, it is primarily valued for its fruits, which have been utilized in East Asia to treat a variety of ailments. E. rutaecarpa exhibits a broad range of pharmacological effects, including the ability to inhibit gastrointestinal motility, relieve diarrhea, prevent ulcers, and exert anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory properties. Modern pharmacological studies have further revealed its anti-tumor activity, immune-modulating effects, and potential role in weight management. Given its diverse therapeutic applications, there has been a significant increase in research related to E. rutaecarpa in recent years. According to the investigation, research on E. rutaecarpa began as early as 1915. This review systematically examines the latest research progress on the bioactive chemical constituents, pharmacological activities, and clinical applications of E. rutaecarpa. It comprehensively summarizes the bioactive compounds identified in this plant genus, including 58 indolo quinazoline alkaloids, 85 quinolone alkaloids, and 21 limonoid components. Additionally, it provides an in-depth analysis of the specific mechanisms underlying the pharmacological activities of E. rutaecarpa. Finally, the review discusses the limitations of current research, such as the risk of neurotoxicity, and outlines future research directions, including toxicity optimization through structural modification and the development of novel drug delivery systems. This work provides a theoretical foundation for the in-depth development of E. rutaecarpa and offers innovative perspectives for the research paradigm of multi-target natural medicine.

-

Key words:

- Euodia species /

- Chemical constituents /

- Pharmacological activities /

- Euodia rutaecarpa