-

Since the discovery of the five major classes of classical plant hormones in the 1950s, extensive research has been conducted on their functions[1]. The initial focus of plant hormone research was on their signaling pathways, which regulate plant growth, development, and responses to adversity[2]. With the gradual rise of the medicinal value of traditional Chinese herbs as a hot topic in the health industry[3], the focus of plant hormone research has shifted to their regulation of the synthesis of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants[4].

Plants, especially higher plants, contain not only primary metabolites such as carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids but also non-essential small-molecule compounds formed through a series of enzymatic reactions using primary metabolites as substrates. This process is known as secondary metabolism[5]. Primary metabolism provides many small molecule substrates as precursors for secondary metabolism, which are generally at branch points in metabolic pathways. These substrates undergo various enzymatic modifications to produce different secondary metabolites[6]. The secondary metabolites of medicinal plants that have been discovered can be classified into several categories, including phenols, terpenoids, saponins, quinones, steroids, and alkaloids. They possess a variety of functions such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor activities, making them key components for the efficacy of medicinal plants. For example, artemisinin, a secondary metabolite extracted from Artemisia annua, is widely used in the treatment of malaria[7]. Another example is vincristine, a monoterpene indole alkaloid derived from the medicinal herb Catharanthus roseus, which is used in antitumor drugs[8].

The synthesis of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants is modulated by a diverse array of factors, primarily divided into biological and abiotic categories. Abiotic factors include environmental stressors such as drought and salinity, which activate the plant's stress response pathways. These external environmental changes can significantly disrupt the plant's internal homeostasis, leading the plant to adjust its hormone levels to regulate the synthesis of secondary metabolites in response to these environmentally induced alterations[9]. Biological factors include the effects of plant hormones, symbiotic microbes, and pathogens or pests, which can activate the synthesis of defense-related secondary metabolites[10]. Symbiotic microbes such as rhizobia and mycorrhizal fungi can influence the synthesis of secondary metabolites in herbs such as Astragalus membranaceus, Salvia miltiorrhiza, and Solanum nigrum[11]. Plant hormones like gibberellins (GA) and abscisic acid (ABA) can regulate the synthesis of ginsenosides in Panax ginseng[12]. Regardless of whether the factors are biological or abiotic, they can all exert secondary metabolic regulatory effects through plant hormones to adapt to their growth environment. Plant hormones can significantly impact the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants by influencing different metabolic pathways, thereby affecting the accumulation of various secondary metabolites. The biosynthesis process of secondary metabolites is highly complex, with numerous plant hormones, such as jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), ABA, GA, and cytokinins (CK), playing crucial roles in regulating the accumulation of secondary metabolites[13]. These plant hormones regulate the synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites through signal transduction mechanisms and interaction networks[14]. For instance, the synthesis of ginsenosides and glycyrrhizinic acid typically starts with steroids or triterpenes, which are modified by glycosyltransferases to link sugar molecules to the steroid or triterpene backbone, a process regulated by plant hormones like JA and SA[15].

As secondary metabolites are fundamental to the efficacy of medicinal plants, research on their metabolic regulation has become a hot topic. However, current investigations into the modulation of secondary metabolism via plant hormones mainly focus on the control of key enzymes in the synthesis pathways of secondary metabolites. Relatively speaking, there are fewer studies on the interactions between hormones and the feedback regulation between hormones and secondary metabolites. Additionally, the complex interactions between various hormones and the involvement of many secondary metabolic pathways result in an unclear network mechanism of hormone regulation in secondary metabolism, and there are relatively few comprehensive literature reviews on this topic[16].

This review addresses these gaps by providing a comprehensive synthesis of the effects of plant hormones on the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants and their interactive roles. It offers a detailed analysis of the regulatory network mechanisms and evaluates current research limitations. By doing so, this review not only advances our understanding of the molecular processes governing secondary metabolism but also provides a foundation for enhancing the quality of Chinese medicinal materials and modernizing the traditional Chinese medicine industry. This work represents a novel contribution to the field, offering fresh insights into the intricate interplay between plant hormones and secondary metabolism, with significant implications for both basic science and applied biotechnology.

-

Plant hormones are trace chemical substances that play a pivotal role in plant growth and development and environmental adaptation. They can regulate plant physiological processes, including cell division, elongation, differentiation, and responses to stress, even at extremely low concentrations. The main types of plant hormones include GA, ABA, ethylene (ETH), JA, SA, and brassinosteroid (BR)[17−22]. These hormones regulate various processes such as growth, maturation, and metabolism through complex signaling networks and interactions, allowing herbs to adjust to fluctuating environmental circumstances[18]. Studying the effects of plant hormones on the growth and metabolism of medicinal plants can clarify their key roles in these plants[19]. Many secondary metabolites in herbs are also active ingredients, and understanding how plant hormones affect their synthesis can lead to methods for increasing the yield of these active components, enhancing the economic value of medicinal plants[20]. Therefore, it is necessary to deeply understand the impact and regulatory mechanisms of plant hormones on the biosynthesis of active components in herbs.

Gibberellins (GAs)

-

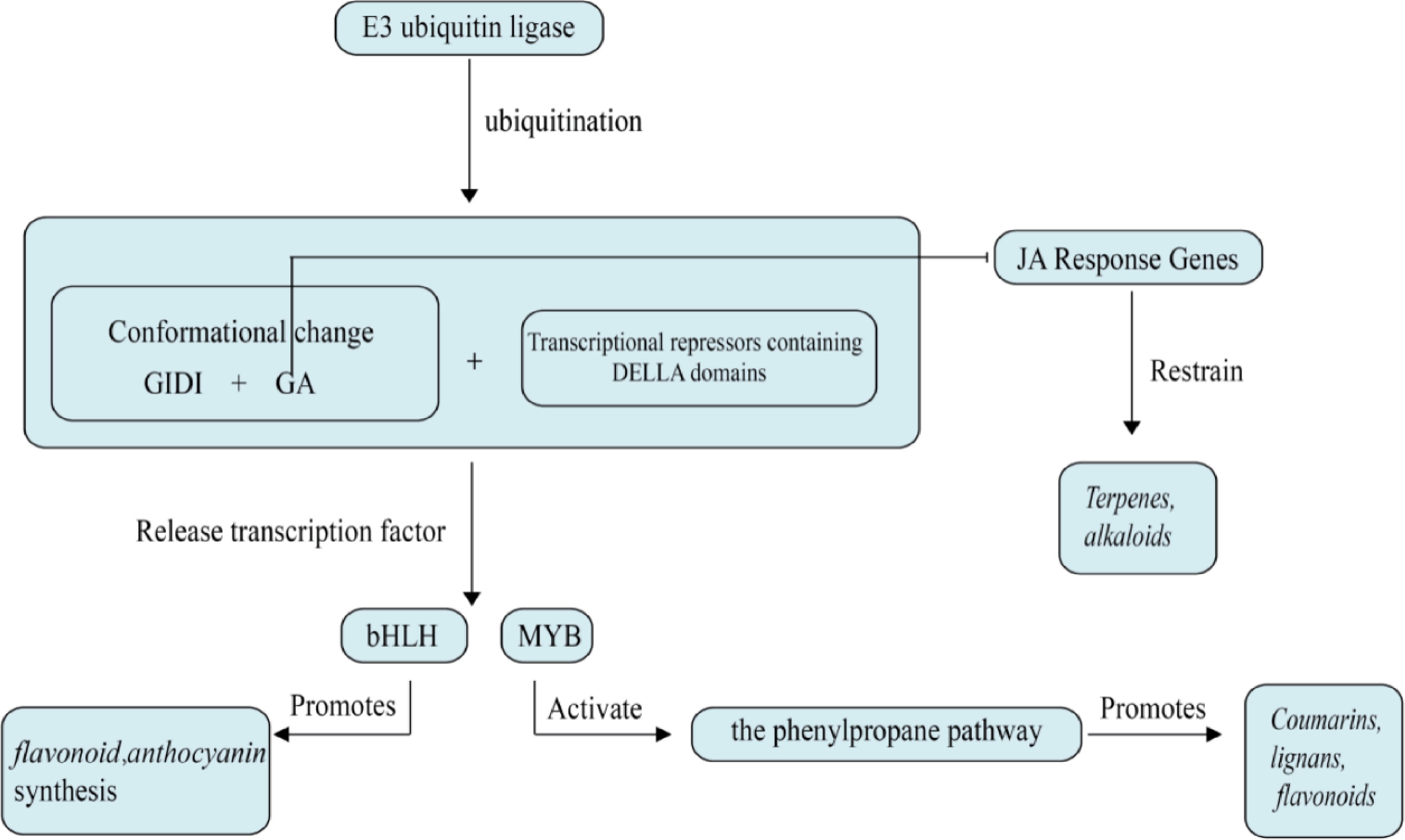

GAs are a class of diterpenoid compounds with a gibberellane skeleton, synthesized through the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway[21]. GA plays a crucial role in promoting cell elongation, stem elongation, seed germination, and fruit development, as well as in the plant's response to stress[22]. Most current research on GA focuses on improving various growth issues in plants. The signaling pathways and components involved in their action include receptors, kinases, phosphatases, and transcription factors, which collectively respond to GA signals and regulate plant growth and development, as shown in Fig. 1. The perception of GA is achieved through the GA receptor GID1 protein, which can bind to GA and promote the binding of GA to DELLA proteins[23]. DELLA proteins are key inhibitors in GA signaling transduction and are a subfamily of the GRAS family. They act as transcriptional repressors in plants and are primarily involved in regulating plant sensitivity to GA[24].

Figure 1.

Effects of gibberellin on plant secondary metabolism. Gibberellin inhibits secondary metabolism of medicinal plants mainly through DELLA protein degradation and hormone signaling antagonism.

GA not only regulates the growth and development of medicinal plants but also participates in the regulation of secondary metabolic pathways. Under the influence of GA, the expression levels of four PgGRAS genes from the DELLA subfamily in P. ginseng hairy roots showed significant changes, and qPCR results suggested that these genes may be involved in GA signal transduction and stress response[25]. Gibberellin degrades DELLA proteins, thereby relieving their inhibition on metabolism-related genes and activating downstream transcription factors, which subsequently upregulates the expression of relevant genes. This process promotes the synthesis of intermediates such as danshenketone diene and rustolone, ultimately leading to the accumulation of secondary metabolites in the form of danshenketones. In S. miltiorrhiza, the SmGRAS gene family, through the action of the GA signaling pathway, inhibits root growth and regulates the biosynthesis of tanshinones by activating the key enzyme gene SmKSL1 in the tanshinone synthesis pathway[26,27]. Research also indicates that GA can activate genes involved in the synthesis of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), leading to an increase in the synthesis of rosmarinic acid[28]. Furthermore, GA can help plants adapt to adverse environmental conditions by regulating the synthesis of stress-related secondary metabolites. Multiple studies have shown that GA oxidases (GAoxs), such as GA3ox, GA20ox, and GA20ox, can form various types of GAs, and GAoxs participate in plant growth and development, regulating plant tolerance to environmental stresses, metabolism, and other processes[29,30]. In alfalfa (Medicago sativa), mutants of MtGA3ox1, which lack functional GA3ox1, showed a significant increase in the diversity of flavonoid metabolites in their leaves, with a significant increase in the content of naringenin (a precursor of flavonoid biosynthesis), apigenin (a precursor of flavonoid and flavonol biosynthesis), and isoflavone aglycones (a precursor of isoflavone biosynthesis). Additionally, with the increase in the mRNA and protein abundance of chalcone-flavonone isomerase family proteins and chalcone-dihydroxybenzene synthase family proteins, the content of liquiritin and isoliquiritin in the leaves of the GA3ox1 mutant also increased, indicating that the biosynthesis of isoflavones, as well as the biosynthesis of flavonoids and flavonols, may be positively regulated by GAs[31,32]. In summary, GA has a positive regulatory effect on the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in herbs.

Cytokinins (CKs)

-

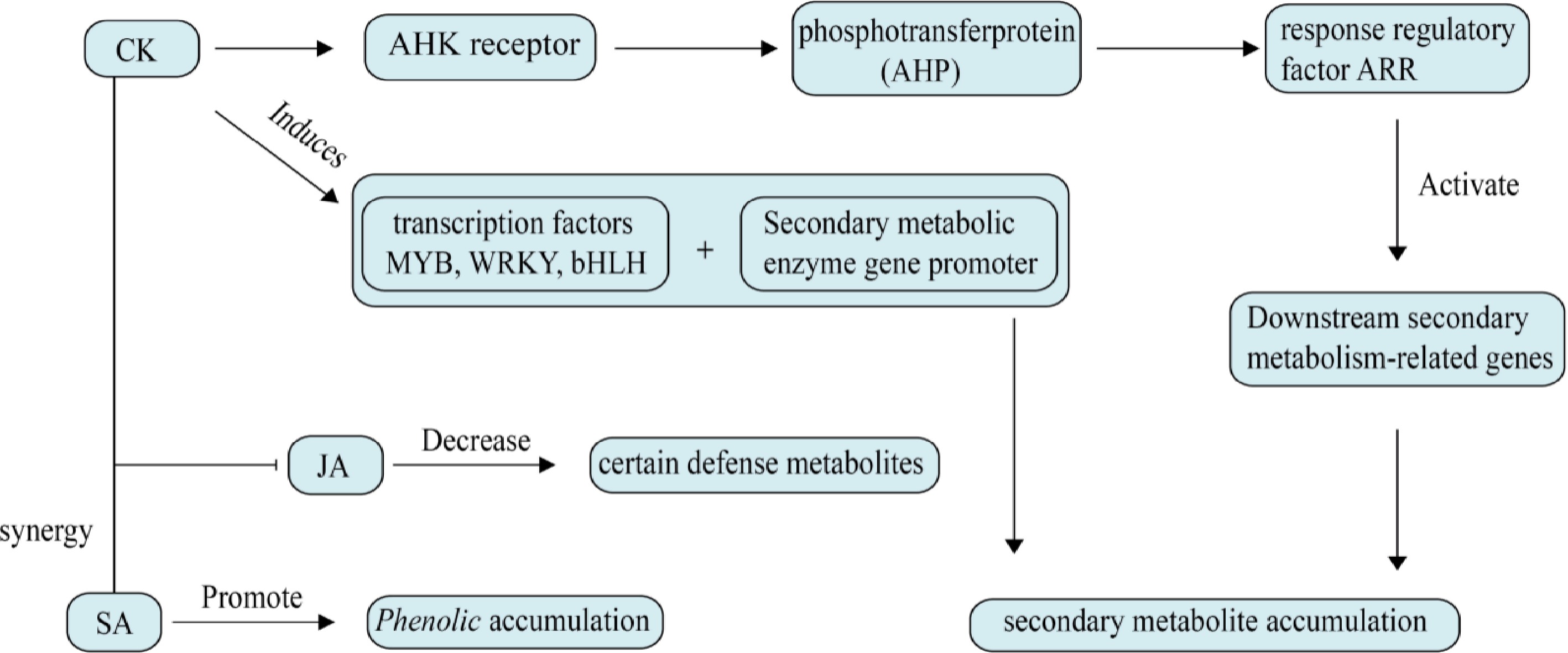

CKs are a group of plant hormones derived from adenine that stimulate cell proliferation and participate in governing the diverse physiological functions of plants by affecting cell division and differentiation[33]. The signaling pathway of CK is generally as follows: CKs bind to the CHASE domain of the receptors (AHK2/3/4), causing auto-phosphorylation of the receptors. The phosphate group is transferred from the histidine residue in the kinase region to the aspartate residue in the signal reception region, and then to AHP. AHP carries the phosphate group into the nucleus, where it is transferred to the phospho-acceptor region of type B ARR in the nucleus, leading to its phosphorylation and activation of type A ARR transcription factors and CRFs. Studies have shown that CRFs have similar functions to type B ARR in regulating CK signaling. The activated transcription factors act on their target genes, causing a series of gene expressions[34].

CK can significantly increase the proliferation rate of medicinal plants and also promote the production, as shown in Fig. 2, and accumulation of secondary metabolites[35,36]. P. ginseng treated with CK can enhance its root growth and development, and increase root yield[29,37], enabling rapid regeneration of some medicinal plants and increased production of active pharmaceutical ingredients. Studies have shown that cytokinin promotes glycyrrhizic acid synthesis by regulating the activity of DXS and related enzymes, which are key genes in the glycyrrhizic acid synthesis pathway, increases the concentration of polar metabolites in Menthaceae herbaceous plants, and promotes the formation of tight callus and bud regeneration[26,38,39]. Additionally, supplementing with CK during plant tissue culture techniques can alter the plant's secondary metabolite profile, allowing for the extraction of secondary metabolites from micropropagated plants[40]. CK can also link plant growth and development to defense, with different CK levels altering defense metabolic products[41]. CK affects secondary metabolic pathways by regulating the expression of key enzyme genes, thereby enhancing the growth, development, and stress resistance of medicinal plants.

Figure 2.

Effects of cytokinin on plant secondary metabolism. CKs transmit signals via histidine kinase receptors, phosphotransfer protein, and response regulator (ARR) to activate downstream secondary metabolity-related genes. At the same time, MYB, WRKY, bHLH, and other transcription factors are induced, which directly bind to the promoter of secondary metabolic enzyme genes. It can also increase the level of intracellular H2O2, activate the antioxidant system, and indirectly regulate the synthesis of phenols and terpenes.

Abscisic acid (ABA)

-

ABA is a pivotal plant hormone that functions as an activator and regulator of abiotic stress resistance mechanisms across various stages of plant development. ABA is primarily synthesized in organs that are in a dormant state or are about to abscise, and its levels in plants increase rapidly under stress conditions[42]. ABA is primarily transported in a free form and does not exhibit polarity in its transport. Its signal perception is mediated by specific receptors and auxiliary receptors that recognize ABA molecules, triggering the phosphorylation of downstream effectors by Snf1-related kinase 2 (SnRK2). This process is a critical step in the activation of ABA signaling and stress response, as phosphorylated SnRK2 can phosphorylate transcription factors such as ABFs and ABI5, ultimately leading to the expression of a series of target genes[35].

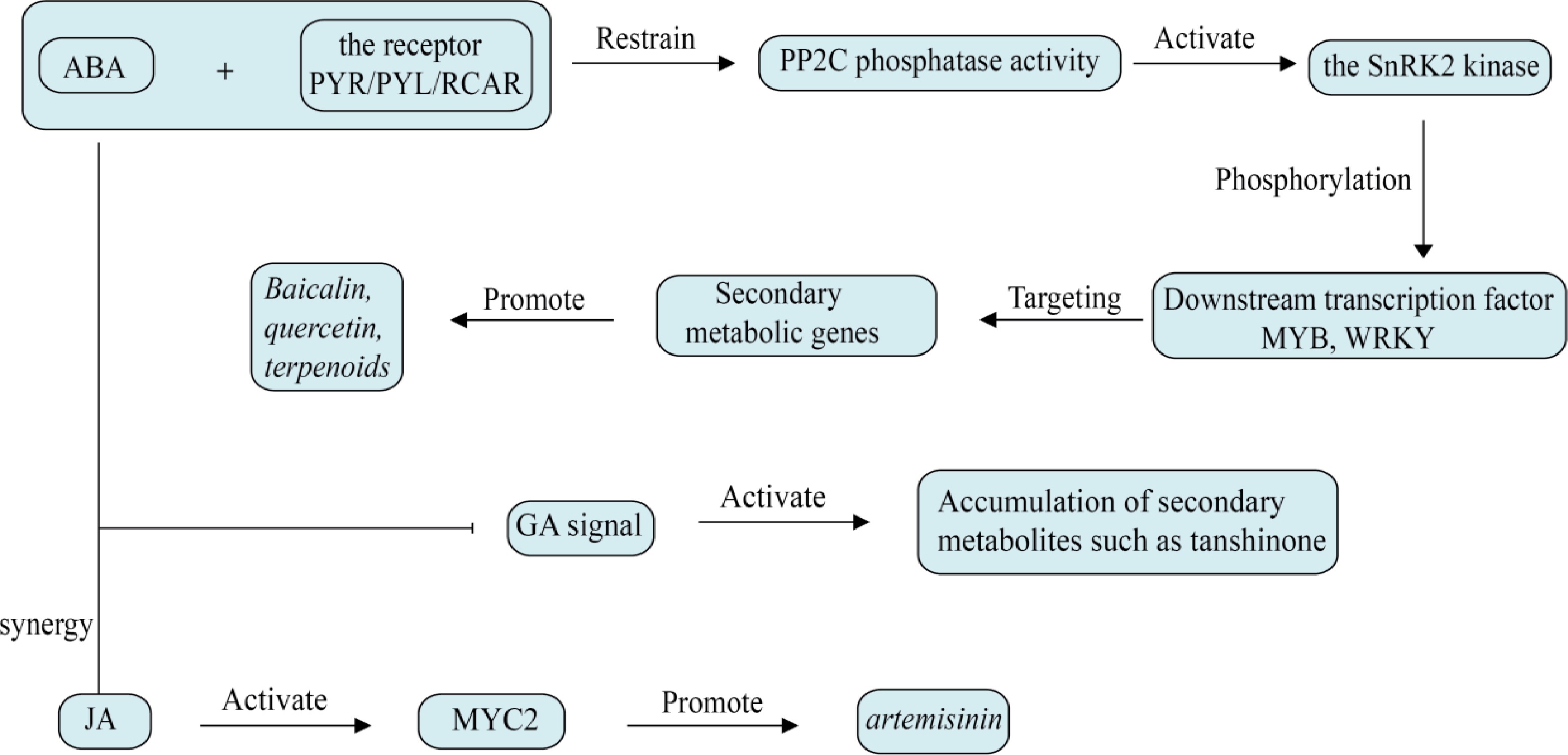

ABA, as a hormone that responds to stress, can selectively trigger the synthesis of certain secondary metabolites in response to environmental stress[36], as shown in Fig. 3. Under NaCl stress, ABA is involved in the signal transduction pathway of salt-induced phenolic synthesis in Lonicera japonica leaves[43]. In American ginseng hairy root cultures, ABA can regulate the biosynthesis of ginsenosides[38]. Treatment with ABA can result in a considerable enhancement of the expression of phenolic acid biosynthesis-related genes in SmbZIP1 overexpression plants, thereby promoting the accumulation of phenolic acids[39]. In S. miltiorrhiza, WRKY transcription factors responsive to ABA can affect the biosynthesis of phenolic acids and tanshinones[44], similar the study by Chen et al. which found that the ubiquitin ligase gene UBE3 is also associated with the synthesis of phenolic acids or tanshinones[45]. In alfalfa, the ABA-sensitive transcription factor MsMYB741 positively controls the expression of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase MsPAL and chalcone isomerase MsCHI, promoting the accumulation of total flavonoids in alfalfa and also promotes the secretion of flavonoids from alfalfa roots[46]. UV-B-induced ABA can inhibit PP2C, activate SnRK2, and up-regulate CHS and IFS expression, thereby enhancing isoflavone accumulation in soybean[47].

Figure 3.

Effect of abscisic acid on plant secondary metabolism. Abscisic acid directly activates secondary metabolic enzyme genes through the SnRK2-MYB/WRKY pathway, and amplifies the interaction between ROS signaling and hormones.

Ethylene (ETH)

-

ETH is a gaseous plant hormone that, unlike other plant hormones, is produced and acts locally only in the areas where it is needed, without being transported over long distances within the plant. It participates in the processes of plant ripening and senescence and has an impact on plant disease resistance[48]. The model of the ETH signal transduction pathway is the ETR1 (EIN4)-CTR1-EIN2-EIN3 (EIN5)2 ETH response[49]. ETH signal transduction begins with a family of five components of the ETH receptor family (ETR, ETH receptor) family, followed by CTR and ETR1, which have protein kinase activity and act as negative regulators of ETH signal transduction. Downstream and at the end of the signal transduction are EIN2, and EIN3 (ETH-insensitive 2,3), which are positive regulators of ETH signal transduction. ETH receptors sense ETH and transfer the signal to a downstream component protein CTR1, similar to animal Raf kinase, through the phosphorylation of the histidine protein kinase domain of the receptors[50]. CTR1 protein is a central component of ETH signal transduction, acting downstream of ETH receptor proteins and being a negative regulator of EIN2, EIN3, and EIN5. When ETH is not present in the plant, the ETH receptor ETR binds to CTR1, maintaining its protein kinase activity and inhibiting ETH response, specifically, active CTR1 phosphorylates EIN2, and the kinase domain of CTR1 binds to the carboxyl-terminal domain (516-1294) of EIN2. Upon the appearance of ETH, the receptors are inactivated and separate from CTR1, leading to the dephosphorylation of several sites on EIN2 and the proteolysis of one of these sites. The carboxyl-terminal domain of EIN2 enters the nucleus, activating the activity of EIN3 and its homologous proteins, and then activating the activity of ERF1 and other transcription factors, initiating the expression of target genes and causing a series of ETH responses[51]. Meanwhile, two types of F-box proteins also regulate this signaling pathway, such as EBF1/2 regulating the degradation of EIN3 and its homologous proteins, and ETP1/2 regulating the degradation of EIN2, both processes are completed through the ubiquitination process dependent on the 26S proteasome[52].

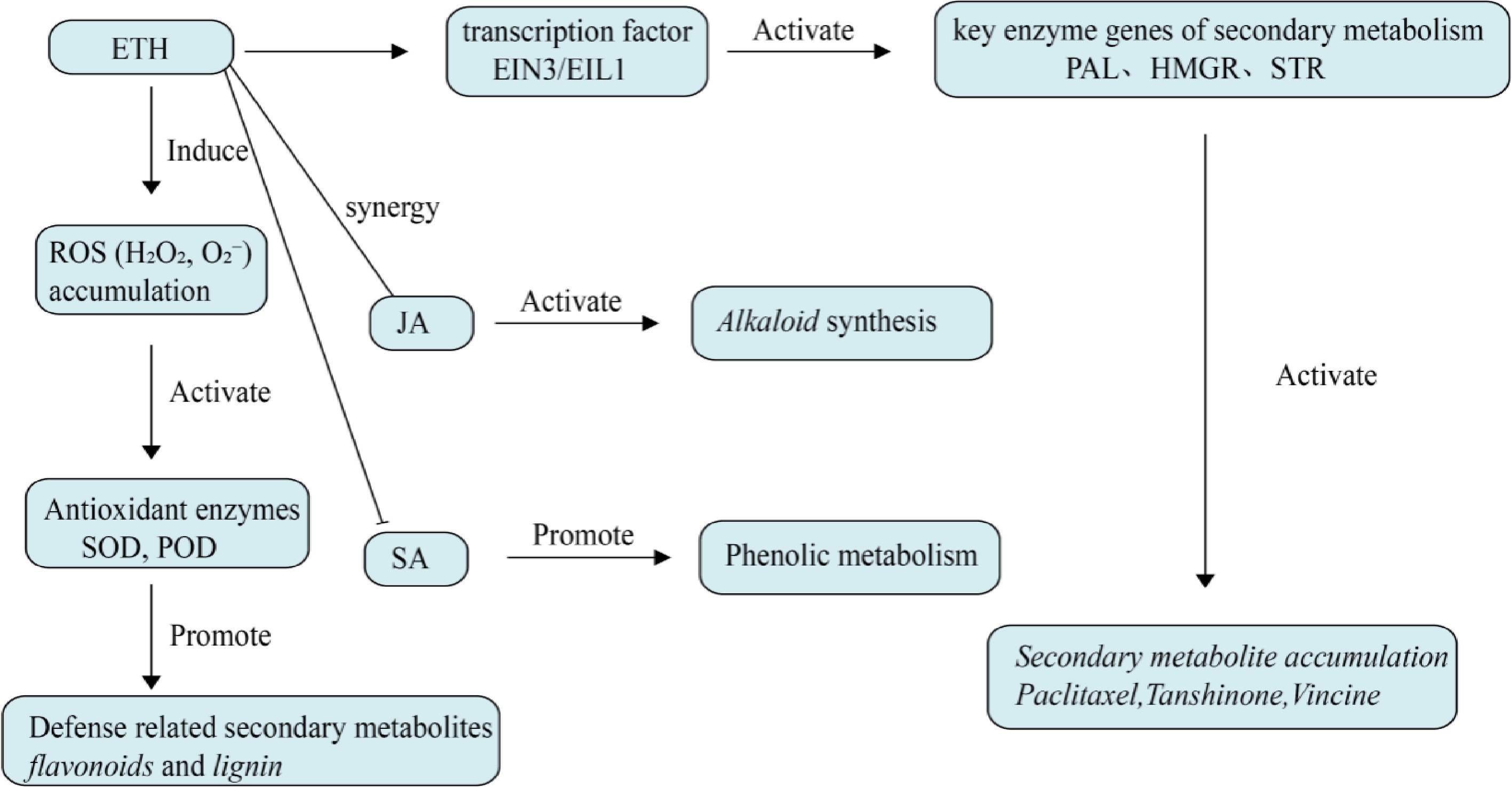

Under stress conditions, plants typically experience an increase in ETH levels, which can promote the formation of secondary metabolites,as shown in Fig. 4. The ERF family of proteins is a key component of the ETH signaling pathway and plays an important regulatory role. In S. miltiorrhiza, ERF family (Ethylene Response Factor Family) transcription factors coordinately regulate the biosynthesis of tanshinones and the expression of seven key genes in the upstream methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway[53]. Bai et al. identified the SmERF6 transcription factor from the ERF family of S. miltiorrhiza, which is highly expressed in the roots of S. miltiorrhiza and responds to ETH treatment, regulating the biosynthesis of tanshinones. SmERF6 overexpression in hairy roots increaseed the accumulation of tanshinones and maintained the steady state of total phenolic acids and flavonoids in S. miltiorrhiza[54]. Li et al. identified the ETH-responsive transcription factor SmEIL1, and overexpression of SmEIL1 markedly reduced the biosynthesis of tanshinones and downregulated the expression of key genes involved in tanshinone biosynthesis[55]. Studies have also shown that the negative correlation between ethylene signaling and artemisinin biosynthesis is mainly attributed to ethylene inhibiting the expression of key genes and enzymes in secondary metabolic pathways through AaEIN3 induced leaf senescence, thereby reducing artemisinin-biosynthesis[56]. Exogenous application of ETH enhanced the resistance of Catharanthus roseus to cadmium and significantly promoted the biosynthesis of anthraquinone indole alkaloids[57].

Figure 4.

Effect of ethylene on plant secondary metabolism. Ethylene directly activates key enzyme genes of secondary metabolism mainly through EIN3/EIL1 transcription factors, and can also cooperate with other plant hormones to regulate defense metabolites. Ethylene can also induce ROS accumulation, activate antioxidant enzymes, and indirectly promote defense-related secondary metabolism.

Jasmonic acid (JA)

-

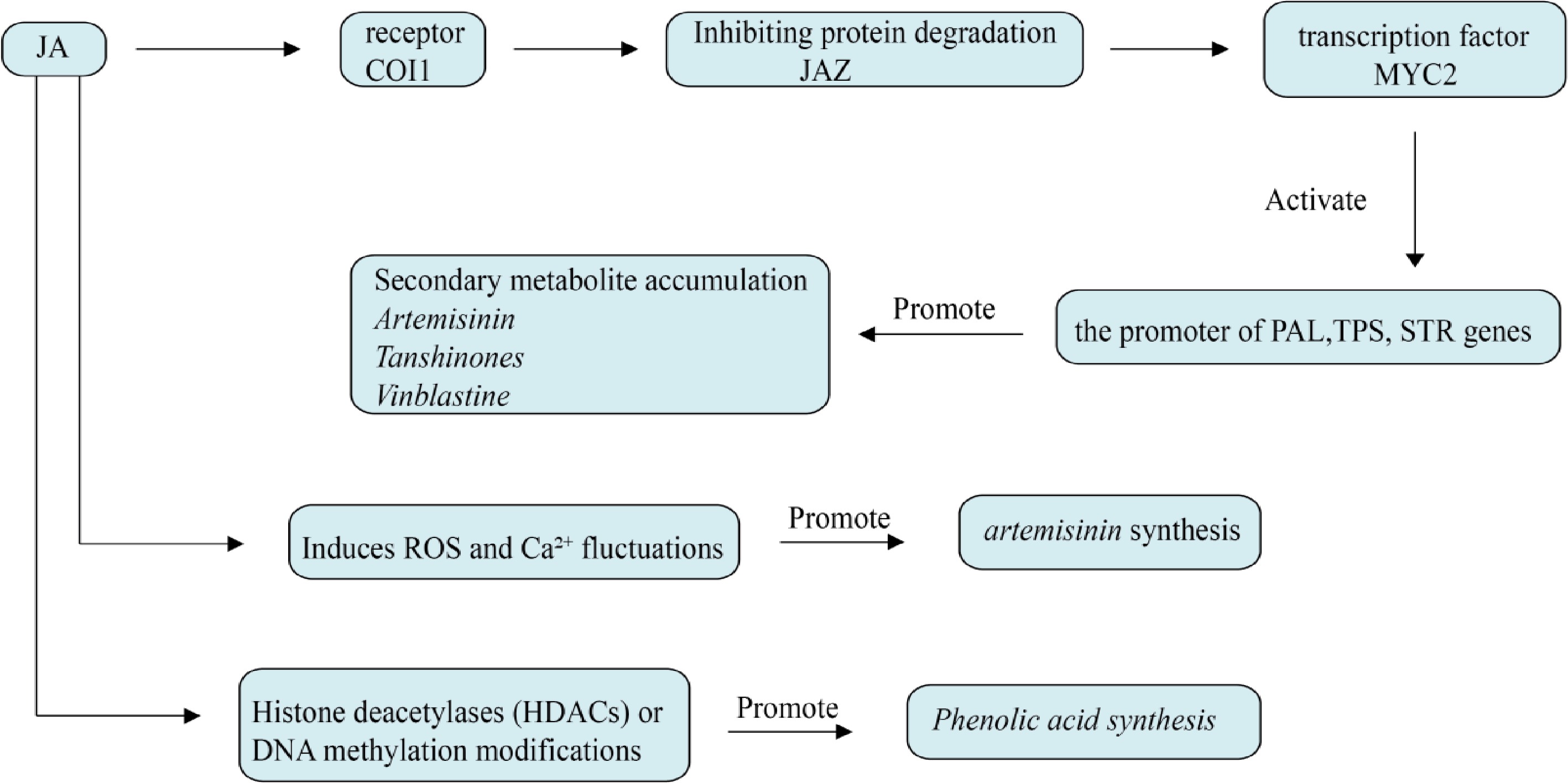

JA is one of the fastest signaling molecules in plants in response to external stimuli, including JA and its volatile methyl ester derivative methyl jasmonate (MeJA), which play pivotal roles in plant growth and development, defense responses, and responses to environmental stresses[58]. The defense responses that rely on jasmonates as regulatory signals are also prerequisites for the accumulation of plant secondary metabolites, as shown in Fig. 5. Jasmonates can affect plant secondary metabolism at the transcriptional level by coordinately expressing a series of biosynthetic genes[59]. When plants are injured, they synthesize large amounts of JA, which is then converted into the biologically active form (+)-7-iso-jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine (JA-Ile). The presence of JA-Ile promotes the formation of the SCF-COI1-JAZ auxiliary receptor complex. This complex mediates the degradation of JAZ (Jasmonate ZIM-domain) proteins through a 26S proteasome-dependent ubiquitination process, thereby relieving the inhibition of the MYC2 transcription factor by JAZ. With the activation of MYC2, the transcription of its downstream genes is initiated, triggering plant defense and repair responses. During this process, the content of secondary metabolites in some herbs may also increase[60].

Figure 5.

Effect of jasmonic acid on plant secondary metabolism. Jasmonic acid can directly activate key genes of secondary metabolism through MYC2 transcription factor, and can coordinate with other plant hormones to regulate defense metabolites. It also induces fluctuations in ROS and Ca²+ and activates the MAPK cascade, which in turn affects artemisinin accumulation.

Jasmonic acid is not only involved in the regulation of plant growth and development but also plays a key role in the synthesis of secondary metabolites and stress response. JA works synergistically with other plant hormones through complex signaling pathways to balance plant growth, development, and resilience[61]. JA promotes the degradation of JAZ (Jasmonate ZIM-domain) protein through JAR1 (Jasmonate Resistant 1), and releases the inhibition of MYC transcription factors (such as MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4), thus activating the expression of downstream genes[62]. JA promotes the synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites such as phenols and tanshinones by regulating the expression of key enzyme genes. Jasmonate carboxyl methyltransferase (JMT) plays a crucial role in JA signal transduction and may be involved in the conversion of JA to MeJA, thus participating in the regulation of plant defense response and metabolic processes. The research by Pei et al. showed that overexpression of SmJMT gene could promote the accumulation of phenolic compounds by activating the expression of key enzyme genes in the phenolic acid biosynthesis pathway, improve the endogenous MeJA level of S. miltiorrhiza, and promote the accumulation of tanshinone in hairy roots by activating the expression of genes related to tanshinone biosynthesis[63]. The JA signaling pathway can induce the expression of SOD-related genes, thereby increasing the synthesis of SOD, and at the same time, SOD and other antioxidant enzymes (such as CAT and APX) cooperate to form a complete antioxidant defense network and realize antioxidants in medicinal plant[64]. By regulating the synthesis of secondary metabolites, JA helps medicinal plants such as S. miltiorrhiza adapt to adverse conditions such as metal pollution and high salt, and enhance their ability to cope with adversity[65].

Salicylic acid (SA)

-

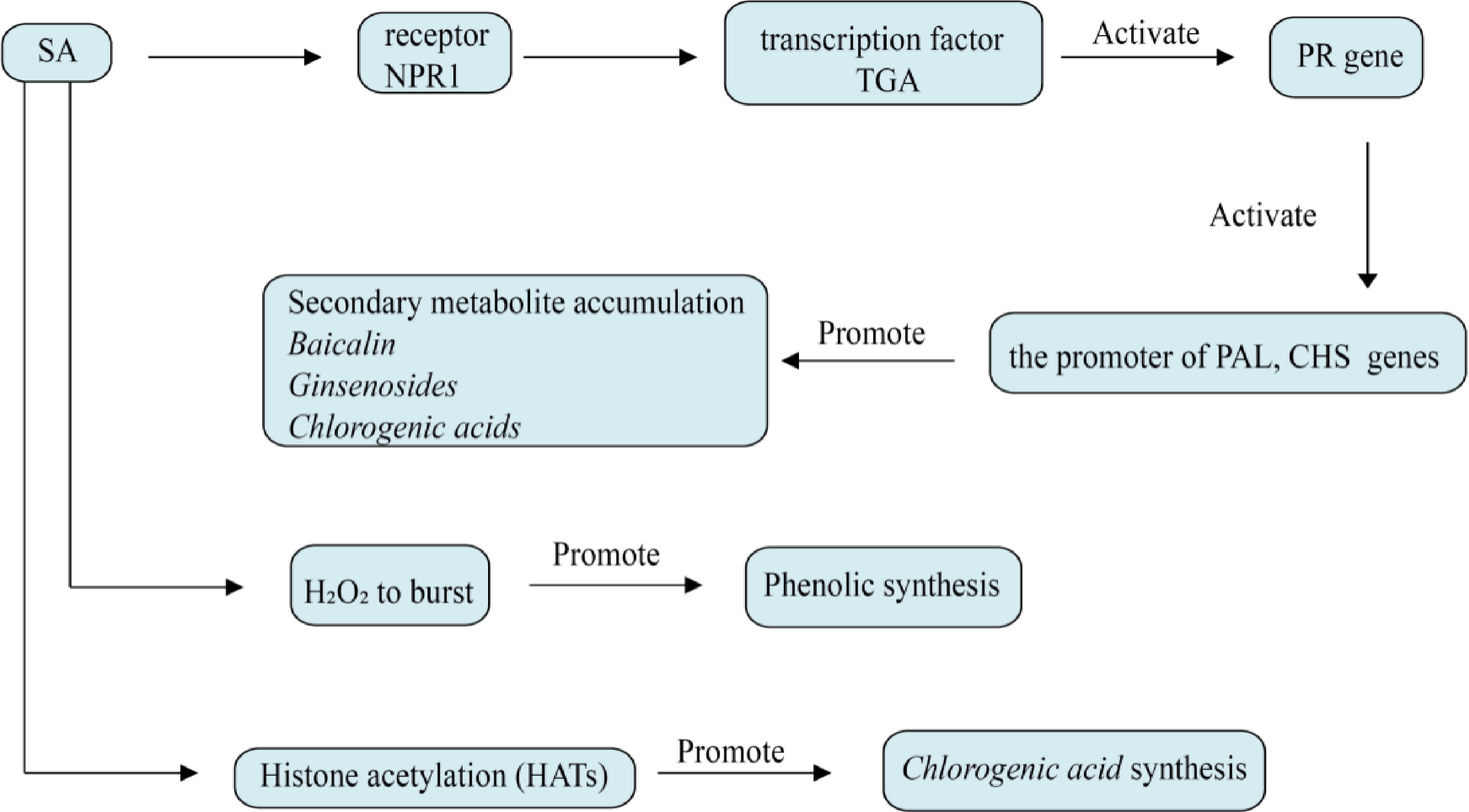

SA, in contrast to traditional plant hormones, does not participate in governing the processes of growth and development but plays a key role in plant secondary metabolism and stress responses as part of the defense response, as shown in Fig. 6. It is detected by two types of receptors, NPR1 and NPR3/NPR4, in plant cells, and NPR1 and NPR3/NPR4 act through two parallel signaling pathways within the plant to jointly regulate the expression of SA-induced defense genes[66]. They activate the biosynthesis of N-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (a precursor of SA biosynthesis), which is crucial for inducing systemic acquired resistance in plants. Additionally, NPR1 and NPR4 participate in the positive feedback enhancement of SA biosynthesis and the maintenance of SA homeostasis, encompassing modifications like 5-hydroxylation and glycosylation[67]. SA has a significant impact on the stress response and the synthesis of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. SA can regulate the expression of key enzymes in the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway, while phenylalanine aminolyase (PAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H), and 4-coumaryl-CoA ligase (4CL) are key enzymes in the phenolic acid biosynthesis pathway, so SA induction can increase the content of phenolic acid, which is the main bioactive compound in many medicinal plants[68]. In hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza, NPR protein SmNPR4 strongly responded to SA treatment as an inhibitor of SA-induced phenolic acid biosynthesis. The researchers identified an alkaline leucine zipper transcription factor, SmTGA5, that interacts with SmNPR4 and stimulates the expression of the phenolic acid biosynthesis gene, SmTAT1, by binding to the as-1 motif[69]. In the regulation of the antioxidant defense system of medicinal plants, such as in the leaves of Momordica grosvenori, SA treatment slightly increased the levels of ascorbic acid (AsA) and glutathione (GSH), enhanced the antioxidant defense mechanism of monk fruit, and alleviated the negative effects of hypoxia stress on plant growth and oxidative stress[70]. SA can also interact with methyl jasmonate (MeJA), and in some studies, it has been found that SA does not directly increase the number of secondary metabolites in herbs, but rather promotes the accumulation of active ingredients by promoting other plant hormones such as MeJA. For example, methyl jasmonate and SA synergism enhance Bacoside A content in shoot cultures of Bacopa monnieri[71–72].

Figure 6.

Effect of salicylic acid on plant secondary metabolism. The core of salicylic acid regulation is NPR1-TGA axis, which directly activates key enzyme genes such as PAL, CHS, and β-AS. It can also induce H2O2 eruption, activate the MAPK cascade and affect the synthesis of phenolic substances. Salicylic acid can also affect metabolites by opening PAL and CHS genes through histone acetylation (HATs).

Brassinosteroid (BR)

-

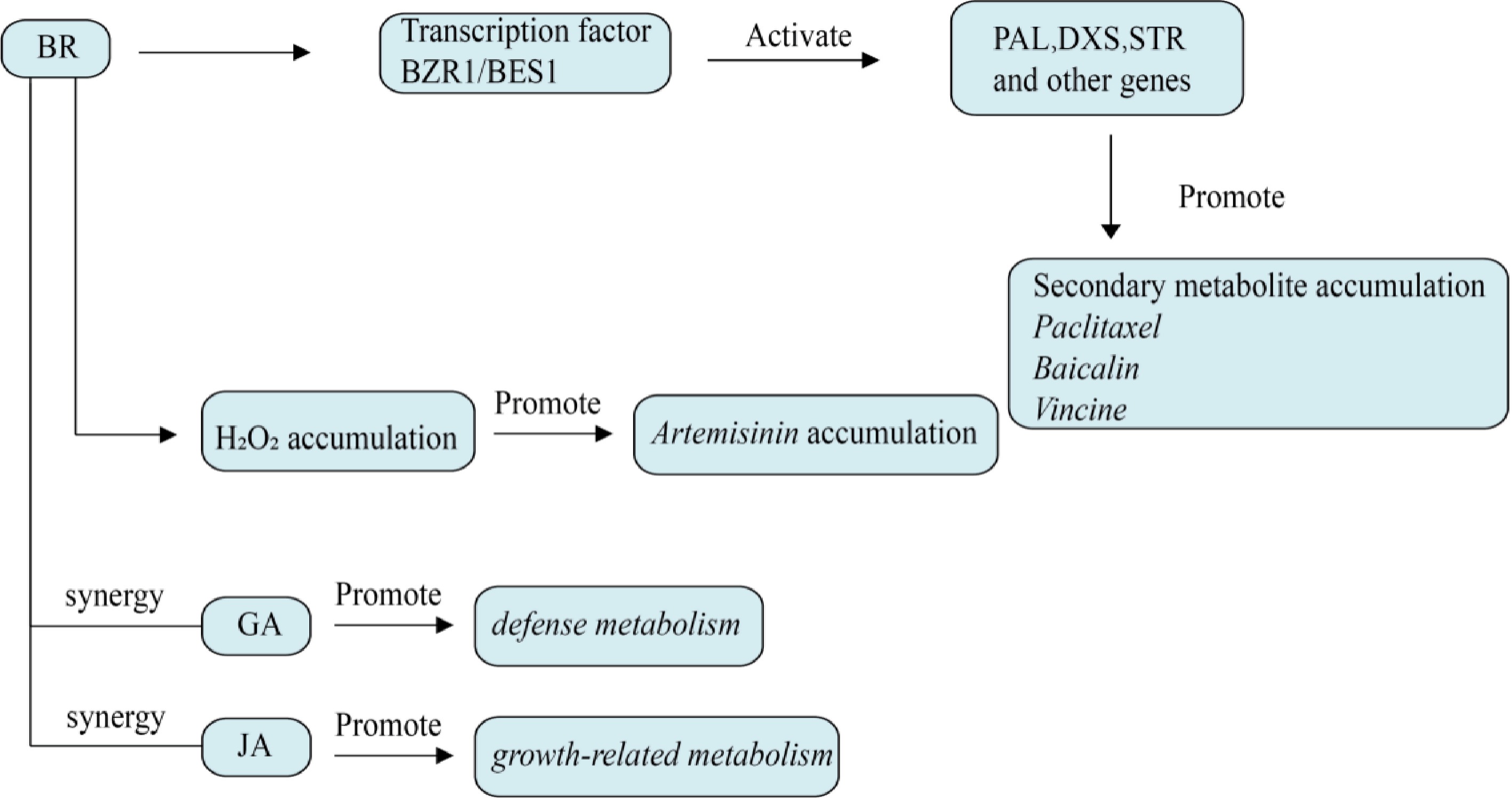

BRs are synthesized from cholesterol through a series of enzymatic reactions, ultimately forming active BRs. BRs do not act through nuclear receptors but are transmitted via cell membrane-surface receptor kinases (BRI1). BR binds to BRI1 and is perceived, and BRI1 interacts with the co-receptor BAK1 to form a heterodimer, undergoing autophosphorylation or cross-phosphorylation. In the absence of BR perception, the negative regulatory protein BKI1 binds to BRI1, preventing BRI1 from binding to its co-receptor BAK1 and thus negatively regulating the BR signaling pathway. When the BR receptor BRI1 perceives brassinosteroids, it phosphorylates BKI1, causing BKI1 to dissociate from the cell membrane into the cytoplasm, allowing BAK1 to bind to BRI1[73]. Activated BRI1-BAK1 phosphorylate downstream kinases BSKs and CDG, which then induce the dephosphorylation of the downstream phosphatase BSU1. The phosphorylated BSU1 has enhanced dephosphorylation capabilities and inhibits the activity of BIN2. When BR levels are low, BIN2 is active and can phosphorylate the binding sites of BZR1/2 and GRFs, with GRFs binding to BZR1/2 keeping BZR1 in the cytoplasm, and the phosphorylated BZR1/2 can also be degraded by the proteasome in the cytoplasm. When BR levels increase, the activity of BIN2 decreases, and BZR1/2 is rapidly dephosphorylated by PP2A, moving into the nucleus to initiate a series of gene expressions[74].

After binding with receptor BRI1 on the cell surface, BRs regulate some transcription factors, thereby improving the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, and APX, further increasing the content of antioxidant secondary metabolites, improving the activity of plant antioxidant defense system and enhancing plant stress resistance, as shown in Fig. 7. BRs can also increase polyamine synthesis by regulating the expression of some genes or interacting with other plant hormones. 2,4-Epbrassinolide (EBL) can induce the expression of arginine synthase in the polyamine synthesis pathway of alfalfa under salt stress, promote the biosynthesis of arginine, and thus enhance the salt tolerance of plants[75]. Wang et al. demonstrated the regulatory effect of BZR1 on the biosynthesis genes of GSL (glucoside thiioside) and major sulfur metabolic pathway genes through transient expression experiments in tobacco leaves, and GSL and its degradation products play an important role in disease resistance and pest resistance, regulation of oxidative stress, and enhancement of stress tolerance[76]. Under salt stress, exogenous application of BR can alleviate the decline of SOD, CAT and APX enzyme functions in peppermint leaves, and significantly increase the total essential oil content[77]. BR treatment can promote the synthesis of some specific secondary metabolites through the expression of specific genes. BR treatment increased the expression of KAT and AHAS genes in hemifruit, indicating that in the presence of BR, 3-oxo-3-phenylpropropyyl-coa is transformed into 1-phenyl-1-2-profendione, thus promoting the synthesis of ephedrine in tubers[78]. In addition, Wen et al. confirmed by spraying BR (0.1 mg /L) on the surface of leaves that BR can significantly increase the contents of tea polyphenols, catechins, amino acids, and caffeine in tea under cold stress, and improve the antioxidant capacity and quality of tea[79]. BRs can enhance the antioxidant capacity and stress resistance of plants by regulating the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes, polyamine synthesis pathway, and secondary metabolite synthesis.

Figure 7.

Effect of brassinolide on plant secondary metabolism. BZR1/BES1 is the core transcription factor regulated by brassinolide, which directly activates PAL, DXS, STR, and other genes. BRs induces the accumulation of H2O2, activates the MAPK cascade, and affects the metabolite content.

Auxin

-

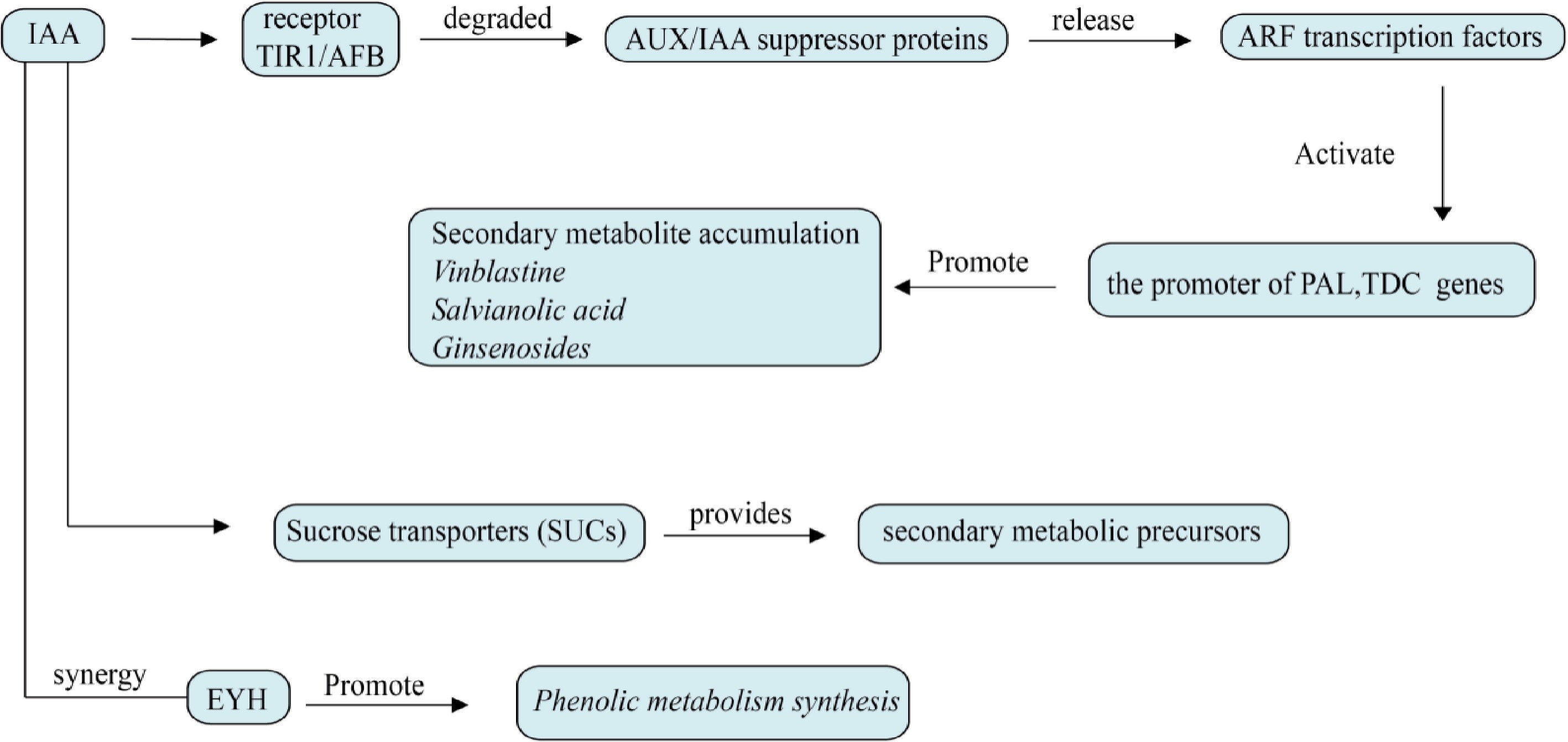

Auxin is the first discovered plant hormone, which plays an important role in regulating plant growth. Auxin regulates the secondary metabolism of plants through various mechanisms, as shown in Fig. 8, including promoting the synthesis of secondary metabolites, regulating plant response to environmental stress, affecting the interaction between plants and microorganisms, and regulating plant hormone balance. These effects not only help the growth and development of plants but also enhance the resistance and adaptability of plants[80]. The mechanism of auxin has been studied earlier, and the signal transduction system of auxin has also been reported. Auxin receptor TIR1 and its homologous protein AFB1/2/3/4/5 are a component of the SCF complex. Auxin binding to TIR1 significantly promotes the interaction of TIR1 with AUX/IAA. AUX/IAA proteins inhibit the auxin signaling pathway by negatively regulating ARF transcription factors. When auxin content was low, AUX/IAA inhibited ARF transcription factor activity together with TPL/TPP. When the content is high, it binds to SCFTIR1 ubiquitin ligase, promoting ubiquitination of AUX/IAA protein, and subsequent degradation of AUX/IAA protein and release of TPL/TPR lead to activation of ARF and deinhibition of signaling pathway[81].

Figure 8.

Effects of auxin on plant secondary metabolism. ARF transcription factor is the core of auxin regulation and directly activates rate-limiting enzyme genes such as TDC, PAL, and DXS. Auxin enhances the sugar input to the library tissue through sucrose transporters (SUCs) and provides secondary metabolic precursors. It can also interact with other plant hormones and act on plants.

Auxin promotes the synthesis of tanshinone and phenolic acid by regulating the key enzyme genes SmKSL1 and PAL in the biosynthesis pathway of tanshinone and phenolic acid. The adaptive ability of S. miltiorrhiza to stress (such as drought and salt stress) could be enhanced by regulating the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes[82]. Auxin response factor (ARF) is an important component of auxin signaling. Auxin affects auxin distribution in ginseng root and expression of ginsenoside biosynthesis-related genes by regulating the transport of PIN and PILS proteins and transcriptional regulation of PgARF, then regulating ginsenoside accumulation[83–84]. In addition to promoting root growth and development and callus and bud regeneration, thereby indirectly affecting the synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites, auxin can also enhance the adaptability of medicinal plants to drought, salt stress, and cold stress by regulating the antioxidant defense system and the synthesis of secondary metabolites[85]. Table 1 is a summary of the effects of some plant hormones on secondary metabolites of medicinal plants.

Table 1. The effects of plant hormones on secondary metabolites of medicinal plants.

Phytohormone Medicinal plant Secondary metabolites and influence Ref. GA Stevia rebaudiana Promote the biosynthesis of steviol [86] S.miltiorrhiza Regulate the synthesis of tanshinones, phenolic acids and anthocyanins in S. miltiorrhiza [87–88] Echinacea purpurea Increase the production of secondary metabolites caffeic acid derivatives and lignin in hairy roots of E. purpurea [89] Eucommia ulmoides GA inhibits SbMYB12 by degrading DELLA protein, resulting in a 50% reduction in baicalin content [90] CK Santalum album heartwood Cytokinin promote the accumulation of essential oils, flavonoids and phenols in S. album [91] ABA Glycyrrhiza uralensis Abscisic acid increased the contents of triterpenoid saponins and flavonoids in G. uralensis root [92] S. miltiorrhiza Regulate the synthesis of tanshinones and phenolic acids in S. miltiorrhiza [39] Camptotheca acuminata ABA signal positively regulates biosynthesis of camptothecin [93] ETH Uncaria rhynchophylla Ethylene can promote the production of crotonine and isocrotonine in U. rhynchophylla [94] Lithospermum erythrorhizon Synthesis of shikonin from hairy roots of comfrey induced by ETH [95] Morinda citrifolia fruits (22S, 23S)-high brassinolide induced Artemisinin accumulation in hairy root culture of Artemisia annua [96] JA Mentha piperita Foliar application of methyl jasmonate can induce secondary metabolites of peppermint [97] Panax notoginseng (Burk.)

F. H. ChenRegulation of JA in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can promote the accumulation of notoginseng saponins [98] Platycodon grandiflorus

(Jacq.) A. DC.Exogenous MeJA application can increase the saponin content in the roots of p . grandiflorus [99] SA Silybum marianum Salicylic acid increases the accumulation of flavonoid lignans in S.marianum fruit [100] Melissa officinalis Salicylic acid promotes the metabolism of rosmarinic and lithospermic acids in M.officinalis [101] Cannabis sativa Salicylic acid stimulates the production of cannabinoid compounds [102] BR Artemisia annua (22S, 23S)-high brassinolide promoted artemisinin accumulation in hairy roots of A. annua [103] IAA Artemisia annua IAA mediates A. annua photoregulation of artemisinin biosynthesis [104] -

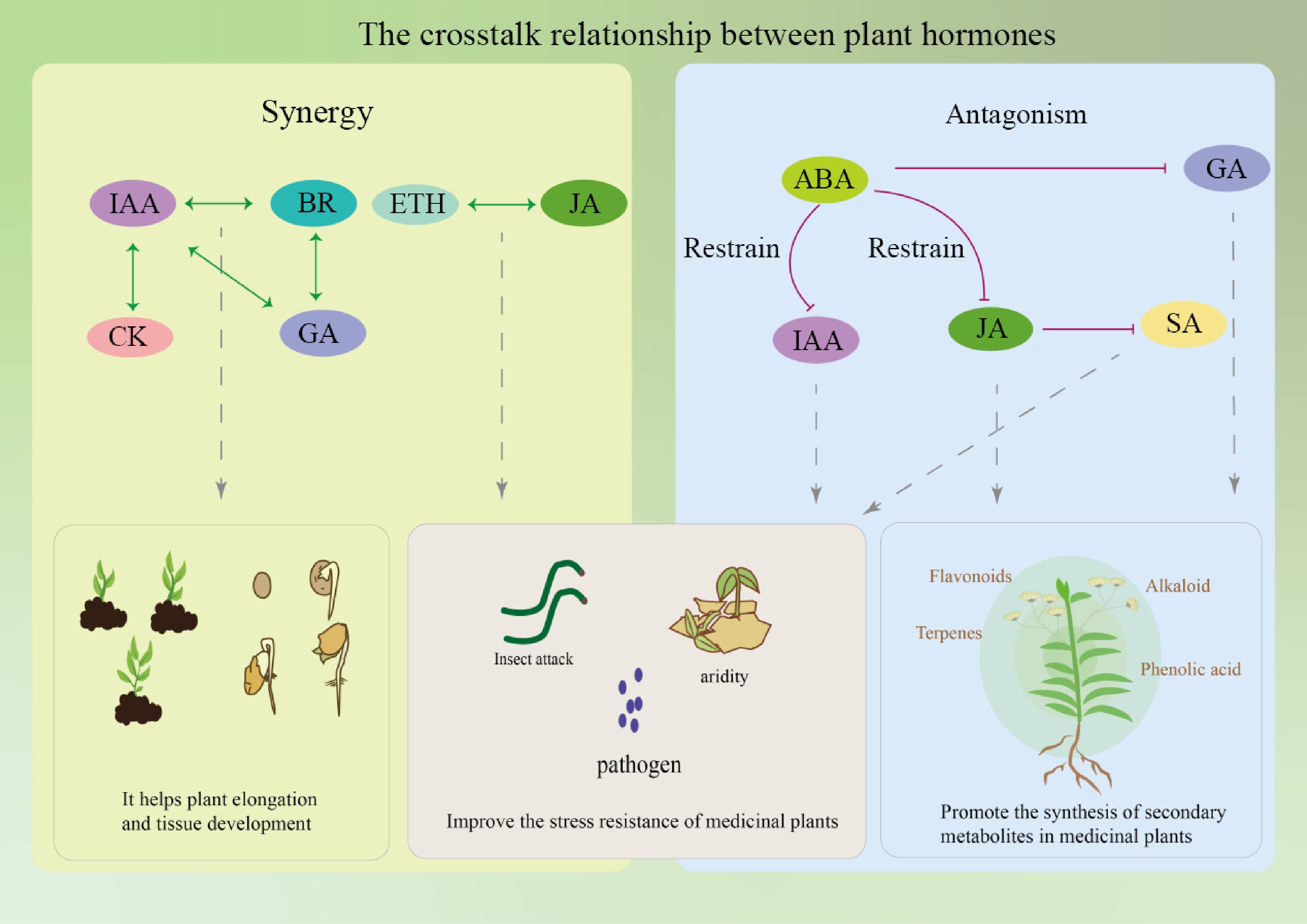

Signal crosstalk of plant hormones refers to the interactions and influences between different plant hormone signaling pathways, as shown in Table 2, which collectively affect the growth and development, secondary metabolism, and stress response processes of medicinal plants[105,106]. For example, during the growth and development stage, the growth of roots, stems, and leaves, as well as leaf expansion, in medicinal plants, are influenced by CKs and GAs. Plant hormones can also interact to promote the synthesis of secondary metabolites, such as ETH and MeJA, which can regulate different signaling pathways and jointly promote the accumulation of catharanthine[107,108]. Additionally, in various environmental stresses, plant hormones like MeJA and ABA play crucial roles in stress responses[109]. It has also been shown that plant hormones can affect the growth and secondary metabolism of a single hairy root species, thus affecting the production of artemisinin[110]. However, the mutual influences among different plant hormones are not simply one of mutual promotion or inhibition, but rather a complex network of hormone regulation involving synergistic, antagonistic, and regulatory interactions, to promote the growth and metabolism of plants as shown in Fig. 9.

Table 2. Interaction of some plant hormones.

Phytohormone relationship Example Ref. Synergy Jasmonic acid and abscisic acid cooperate in plant response to drought stress [111] Ethylene and gibberellins have synergistic effect in the germination stage of A. thaliana [112] Cytokinin targets auxin transport to promote bud branching in A. thaliana [113] Synergies between jasmonic acid and salicylic acid pathways in tea plant enhance its anti-herbivore function [114] Auxin and cytokinin act synergistically to mediate aluminium-induced root growth inhibition of A. thaliana [115] The synergistic effect of salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate enhanced the yield of ginkgo lactone [116] The synergistic effect of abscisic acid and jasmonic acid can increase the content of saikosaponin [117] Antagonism ET has antagonistic effect with abscisic acid during seed germination of A. thaliana [112] The antagonism of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid signaling pathway in poplar makes it play an active role in the defense against rust bacteria [118] The antagonism of gibberellin and cytokinin signals controls the differentiation of female A. thaliana germline cells [115] Jasmonic acid and gibberellin have antagonistic effects on plant growth and development in response to environmental and endogenous stimuli [119] Salicylic acid antagonized jasmonic acid, and the contents of terpenoids decreased by 40% [120] The synergistic effects of plant hormones can enhance the synthesis of secondary metabolites. For example, JA and ETH often act synergistically in plant defense responses. Camalexin, an indole-derived antimicrobial metabolite and major phytoalexin in A. thaliana, is regulated by a multilayered synergistic action of ETH, JA, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MPK3/MPK6) signaling pathways[121]. Under low nitrogen conditions, hormones promote the symbiotic relationship between leguminous plants and rhizobia, leading to the formation of nitrogen-fixing root nodules. Bacterial Nod factors and various plant hormones can regulate key signaling molecules such as DELLA1 in this developmental process. DELLA1-mediated GA signaling interacts with CRE1-dependent CK signaling pathways, synergistically regulating early nodulation development. CK and GA jointly regulate plant growth, stress response, and secondary metabolism by influencing each other's signaling pathways[122]. BRs, auxins, and GAs can also collectively participate in the growth and development of the Phellodendron amurense stem, promoting the growth of its main active ingredient, isoquinoline alkaloids[123]. There are interconnections between the pivotal transcription factors EIN3 and EIL1 within the ETH signaling cascade and the primary regulator of SA signaling, NPR1, thus showing synergistic effects between SA and ETH during leaf senescence[124].

There are also antagonistic relationships between certain plant hormones, regulating the buildup of secondary metabolites. A prototypical illustration is that CK treatment can diminish the expression of genes associated with GA biosynthesis, and enhance the expression of DELLA genes GAI and RGA, thus effectively reducing GA activity[125]. After plant tissue injury, auxin and CK are activated by ETH and JA synergistically in the upstream wound response signaling, but SA signaling antagonizes this process[126]. In the herbaceous plant Panax notoginseng, increased ABA signaling inhibits GA signaling, suppressing the expansion of embryonic growth and development space, thereby inhibiting the embryonic development of recalcitrant seeds, promoting dormancy, and delaying germination[127]. The antagonistic effect of ABA and CK signaling can induce drought stress response and enhance drought tolerance[128].

In addition to antagonism and synergy, there are also more complex regulatory relationships between plant hormones. For example, in A. thaliana, stress and ABA treatment suppress the expression of genes coding for isopentenyltransferase, which are involved in CK synthesis, and the majority of genes encoding CK oxidases/dehydrogenases, leading to a decrease in the content of bioactive CK, indicating that there is a mutual regulation between CK and ABA metabolism[129]. ERF proteins play a central role in ETH signaling transduction, and ERFs not only integrate ETH signals but also integrate other plant hormone signals such as JA to respond to various environmental stresses[130]. When plants adapt to alkaline environments, the endogenous level of MeJA increases and interacts with the auxin signaling pathway to enhance plant tolerance, indicating that the interaction and signal integration between hormones play a key role in plant stress resistance[131]. In the process of plant defense against pathogens and insect attacks, SA, ETH, and JA play a core role. These small molecular signals activate and adjust the plant's immune response to biotic pathogens and necrotrophic pathogens through an interwoven network[132]. In addition, ABA inhibits the transcriptional activity of PAL, thereby suppressing the accumulation of SA and inducing the transcription expression of SA defense-related genes[133].

In summary, the interactions between plant hormones have a multifaceted impact on medicinal plants, including growth and development, the synthesis of secondary metabolites, and responses to environmental stresses. Thus, a comprehensive investigation into the interplay among plant hormones is crucial for enhancing the quality and productivity of Chinese medicinal plants.

-

As important internal signaling molecules, plant hormones play a crucial role in regulating the metabolic processes of medicinal plants. They can influence the biosynthetic routes of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants by governing growth, development, and stress responses. Secondary metabolites are the main sources of medicinal properties in medicinal plants, so plant hormones can directly affect the yield and quality of Chinese herbal medicines by controlling the synthesis pathways of secondary metabolites. Plant hormones also participate in plant defense responses by regulating the synthesis of defense-related secondary metabolites, affecting the disease resistance and stress tolerance of medicinal plants. Additionally, at the molecular level, plant hormones influence the synthesis of metabolites in medicinal plants by regulating the activity of specific enzymes and the expression of transcription factors. For example, SA or JA mitigated the metal toxicity of Sedum alfredii by decreasing MDA content, increasing chlorophyll content, and enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity[134]. For another example, jasmonic acid and its derivative methyl jasmonate regulate the plant's defense response by regulating the expression of downstream genes in response to abiotic stimuli such as salt, drought, heavy metals, and low temperatures[135].

In summary, the impact of plant hormones on the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants is a significant topic of research in plant biology and traditional Chinese medicine. Due to the complexity of the regulatory network of plant hormones, involving interactions between various hormones, and the potential differences in their effects across different plant species, growth stages, and environmental conditions, it is challenging to fully understand their complete regulatory patterns. Moreover, many of the synthesis pathways of secondary metabolites are not fully understood, which increases the difficulty of studying how plant hormones regulate these pathways. Additionally, laboratory research on plant hormones often focuses on model plants with shorter growth cycles, such as A. thaliana, but due to the limitations of long growth cycles and imperfect transgenic systems in medicinal plants, research on how plant hormones regulate secondary metabolism in medicinal plants is relatively limited. Therefore, there are many challenges in translating laboratory theoretical research into practical agricultural production practices to enhance the production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants.

This review comprehensively summarizes the effects of various plant hormones on the secondary metabolism of herbs and how these hormones interact to jointly regulate the secondary metabolism of herbs. It deeply analyzes the complex network mechanisms of plant hormones in governing the synthesis of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants and highlights the limitations of current research. In conclusion, although plant hormones are crucial for regulating the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants, current research still faces many challenges. Further technological innovations, method development, and deeper basic research are needed to better utilize plant hormones to enhance the production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 82104325 and 31800259), the Xi'an Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. 24NYGG0051), and the Shandong Province Postdoctoral Fund Project (Grant No. SDCX-ZG202400138).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: formal analysis: Li W, Lin S; investigation, writing−original draft: Li W; software: Wang R, Ni L; writing−review and editing: Chen C, Wang W; supervision: Liang Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this paper as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current research period.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li W, Lin S, Wang R, Chen C, Ni L, et al. 2025. Regulation of plant hormones on the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e020 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0016

Regulation of plant hormones on the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants

- Received: 03 December 2024

- Revised: 21 April 2025

- Accepted: 23 April 2025

- Published online: 25 June 2025

Abstract: With the rise of the big health industry, research on the active ingredients of Chinese herbal medicines has been widely considered. The secondary metabolites of medicinal plants play an important role in preventing and treating various diseases as the active components of Chinese herbal medicine. Therefore, improving the production of secondary metabolites and the quality of medicinal materials in medicinal plants has become the core of research work. Plant hormones, essential for controlling growth, development, and metabolic processes in plants, play a critical role in this regulatory mechanism. They contribute to the growth and development of medicinal plants, influence the synthesis of secondary metabolites, and regulate the synthesis of stress-related metabolites by affecting plant responses to stress. In the past, most of the attention on the effects of plant hormones was focused on regulating plant growth and development, and the metabolic regulation network of hormones on medicinal plants was relatively complex, so there were few systematic and comprehensive reports on related studies. This paper aims to summarize the regulation mechanisms and effects of various plant hormones on the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants, highlighting the intricate interactions among these hormones. It seeks to elucidate the regulatory network of plant hormones in the secondary metabolism of medicinal plants, offering a theoretical foundation for future research on improving the quality of Chinese medicinal materials.

-

Key words:

- Plant hormone /

- Medicinal plants /

- Secondary metabolite /

- Metabolic regulation /

- Signaling pathway