-

Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. is an annual herb belonging to the Lamiaceae family, originating from East Asia and recognized as a traditional Chinese medicinal and edible plant. The use of P. frutescens in traditional medicine involves treating ailments like coughs, headaches, colds, asthma, nasal congestion, chest tightness, and constipation. Modern pharmacological research has noted that P. frutescens has many pharmacological activities ranging from anti-inflammatory[1], anti-allergic[2], antioxidant[3], anti-cancer[4], antibacterial[5], anti-depressant[5], and liver-protective effects[6], among others. Studies related to phytochemical reports have identified that phenolic acids are the primary active ingredients found in P. frutescens; rosmarinic acid (RA) is the leading phenolic acid present in P. frutescens. RA is generally available in Lamiaceae plants, and it can be easily detected in the leaves, fruits, and stems - the principal medicinal parts of P. frutescens prescribed by the Chinese Pharmacopoeia.

Agrobacterium rhizogenes is a soil bacterium that belongs to the gram-negative bacteria and has a broad range of hosts. Its root-inducing (Ri) plasmid has a complete T-DNA, and it carries the rol oncogenes (rolA, B, C, and D)[7]. The basic principle behind hairy root culture involves infecting the recipient plant cells with A. rhizogenes to integrate the T-DNA in the Ri plasmid into the genomic DNA of the recipient cells, and A. rhizogenes infects the injured parts of the plant to induce the growth of hairy roots[8]. Hairy roots possess different characteristics to the original plant, such as hormone-free nature, rapid growth, genetic stability, and others[9]. Many researchers have shown that the production of various secondary metabolites using hairy roots culture is feasible, and these compounds are present at significantly higher levels than in the original plants. Hairy root culture has shown great industrial application potential due to its ability to reliably and stably produce high-value natural products on a large scale. Hairy roots perform exceptionally well in synthesizing secondary metabolites and can efficiently accumulate target compounds. At the same time, the hairy root culture system is simple to set up and easy to operate. In addition to its use in the production of secondary metabolites, hairy root culture has been widely applied in plant gene function research, crop variety improvement, and environmental remediation, demonstrating its broad potential for application across various fields.

Hairy root cultures have been successfully established for several Lamiaceae plants, such as Salvia miltiorrhiza[10], and Salvia bulleyana[11]. In many plant species, the production of secondary metabolites can be improved through the use of elicitors. Methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and salicylic acid (SA) are commonly used elicitors to induce the production of secondary metabolites[12]. Previous studies have shown that MeJA can promote tanshinone production in S. miltiorrhiza cell cultures[13] and increase phenolic acid content in S. miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures[14]. Similarly, SA and MeJA were found to stimulate tropane alkaloid content in transgenic Atropa baetica[15], and significantly enhance phenolic acid content in S. miltiorrhiza and Lithospermum erythrorhizon suspension cell cultures[16,17]. However, the establishment of a hairy root culture system for P. frutescens has not been previously reported. Therefore, we could initially establish the P. frutescens trichocarpa root system as well as observe the changes of secondary metabolites in P. frutescens trichocarpa roots by inducing them using MeJA and SA.

The current study reports the successful establishment of P. frutescens hairy roots using the A. rhizogenes C58C1 induction process for the first time. Five fast-growing hairy root lines were selected, and the accumulation of phenolic acids in these hairy roots was determined. The study also investigated the effects of MeJA and SA on the phenolic acid content in P. frutescens hairy roots. In addition, we constructed transgenic hairy roots expressing the P. frutescens bHLH transcription factors (PfbHLH13/66) and investigated changes in phenolic acid content in the transgenic lines.

-

The seeds of P. frutescens were obtained from the Medicinal Botanical Garden of Jilin Agricultural University (Jilin, China). The fully matured seeds were sterilized using mercury dichloride (HgCl2) for 12-15 min and then washed with 75% ethanol for 30 s, followed by several washes with sterile distilled water. The sterilized seeds were then cultured on a solidified MS medium containing 0.1% agar and 0.3% sucrose according to the protocol described by Murashige and Skoog in 1962[18]. The cultures were incubated at a temperature of 25 °C under a 12/6 h (light/dark) photoperiod in a growth incubator.

For the induction of hairy roots, three A. rhizogenes strains - C58C1, A4, and R1000, were streaked on YEB liquid medium supplemented with Rifampicin (50 mg/mL rif) and incubated at 28 °C. Single colonies were picked and sub-cultured in YEB liquid medium with Rifampicin, following which they were shaken overnight at 28°C. Finally, the density of the A. rhizogenes cells was adjusted to an OD600 nm value of 0.6 spectrophotometrically to facilitate effective hairy root induction.

Transformation and cultures of P. frutescens explants

-

In this study, the middle healthy leaves of 7-week-old P. frutescens seedlings were transformed for hairy root induction. The leaves were cut into 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm pieces, and then placed in liquid 1/2MS medium containing A. rhizogenes strains for 15 min. Co-cultivation was carried out at a temperature of 28 °C in a constant-temperature shaker (120 rpm) under dark conditions. Following co-cultivation, the explants were dried using sterile tissue paper and then transferred onto MS solid medium for three days under dark conditions. The leaves were washed several times with sterile distilled water, dried on sterile filter paper, and finally, placed on MS solid medium supplemented with 500 mg/mL Cefotaxime (Cef). The cultures were incubated at a temperature of 25 °C for seven days to remove bacteria. After this, the concentration of Cef was gradually reduced each week (250, 100, 50, 0 mg/mL) until the bacteria were removed from the hairy roots, which formed at the wounded sites of the explants about one week after induction.

Once the hairy roots reached a length of 5 cm, they were individually transferred to MS solid medium without Cef and cultured until their fresh weight reached approximately 0.5 g. These hairy lines were then cultured in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing liquid 1/2MS medium and maintained on a rotary shaker (120 rpm) at a temperature of 25 °C in the dark. During subculturing, five fast-growing lines were selected for further experiments and labeled P1 to P5.

Confirmation of transformation

-

The rol gene is present in the T-DNA region of the Ri plasmid of A. rhizogenes, which is usually used to identify hairy roots. By designing specific primers for rolB and rolC genes, the DNA of five hairy root clones was extracted for PCR amplified. The specific amplification primers were listed as follows: rolB (423 bp) (Forward: GCTCTTGCAGTGCTAGATTT; Reverse: GAAGGTGCAAGCTACCTCTC); rolC (626bp) (Forward: CTCCTGACATCAAACTCGTC; Reverse: TGCTTCGAGTTATGGGTACA). The plasmid DNA of A. rhizogenes C58C1 was used as a positive control, and the roots of P. frutescens sterile seedling DNA were used as negative controls. The amplified PCR reaction products were run on 1% agarose gel (GelStain staining) electrophoresis, and the 2k DNA marker was used as a reference.

Preparation and application of MeJA and SA

-

Methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and salicylic acid (SA) were both prepared as stock solutions in anhydrous ethanol at a concentration of 0.1 mM and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter. The 20-day-old hairy roots were inoculated into 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 150 mL of 1/2MS liquid medium with a pH of 5.8. Elicitors (MeJA and SA) were added to achieve a final concentration of 100 μM/L[19]. The hairy roots were harvested on days 0, 3, 6, and 9 after treatment and then dried in an oven at 50 °C until a constant dry weight was achieved. To study the growth dynamics of P. frutescens hairy roots, hairy roots grown to approximately 0.5 g on MS solid medium were transferred to a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of 1/2MS liquid medium (pH 5.8). The flasks were then cultured in a shaking incubator at 120 rpm and 25 °C. Subculturing was performed every 7 d, during which the fresh weight and dry weight were measured. Each experimental group was set up with three replicates, and the average values were taken. Growth curves were plotted based on the data of dry weight and fresh weight.

Phytochemical analysis

Extraction procedure

-

The 200 mg powder samples of fast-growing P. frutescens hairy roots lines (P1-P5) and the hairy roots of treatment with elicitor at different periods (0, 3, 6, 9 d) were collected and accurately weighed. Then the hairy roots powder was soaked in 5 mL 70% methanol solution, and treated with ultrasound for 1 h. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm organic membrane and analyzed using an HPLC system.

Quantitative analysis

-

In this study, phenolic acid contents were measured using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), HPLC (Waters USA) analysis system was equipped with an e2695 system separations module and 2489 UV / Vis detector (Waters, USA), and the column was a Cosmosil Cholester packed C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm). The column temperature was 35 °C, detection wavelength was 330 nm. The injection volume was 20 μL. The mobile phase is methanol (A)−0.2% phosphoric acid water (B). The gradient elution system was used: 0−15 min, 25% A; 15−25 min, 25%−50% A; 25−28 min, 50% A; 28−29 min, 50%−25% A; 29−34 min, 25% A. The flow rate was 1 mL/min.

Acquisition of transgenic hairy roots

Induction of transgenic hairy roots

-

The pCAMBIA1304 vector was subjected to double digestion using the restriction endonucleases BglII and BstEII to construct a plant overexpression vector with the target gene. The recombinant plasmid was then transformed into A. rhizogenes strain K599. According to the method described above, explant transformation and cultivation were performed. The induced hairy roots were subjected to genomic DNA extraction using the EasyPure® Plant Genomic DNA Kit. The presence of transgenic hairy roots was identified based on the rolB gene sequence (405 bp) from K599 and the Hyg (hygromycin resistance) gene sequence (535 bp) from pCAMBIA1304.

Sample preparation

-

Wild-type hairy roots, as well as transgenic PfbHLH13-OE and PfbHLH66-OE hairy roots at approximately 45 d of growth, were collected. After removing surface moisture, the samples were divided into two portions: one for RNA extraction and the other for phenolic acid content determination in transgenic hairy roots. The samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

The frozen hairy root samples were freeze-dried and ground into a fine powder. A precise amount of 20 mg of the powdered sample was weighed and extracted with 1 mL of methanol via ultrasonic treatment at 25 °C for 1 h. The extract was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 1 h, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane. The filtrate was stored at 4°C in the dark for further analysis.

UPLC-MS analysis

Chromatographic conditions

-

The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (Phase A) and water (Phase B), with the following gradient elution program: 0–7 min: 5%–20% (A), 95%−80% (B); 7–11 min: 20%–22% (A), 80%−78% (B);11–20 min: 22%–60% (A), 78–40% (B); 20–25 min: 60%–65% (A), 40%−35% (B); 25–28 min: 65% (A), 35% (B); 28–30 min: 65%–95% (A), 35%−5% (B); 30–34 min: 95% (A), 5% (B). The flow rate was set to 0.3 mL/min, with a column temperature of 35 °C and an injection volume of 2 μL.

Mass spectrometry conditions

-

A heated electrospray ionization (HESI) source was employed in negative ion mode, with a spray voltage of 3.00 kV. The scan range was set to 100–1,500 m/z. The resolution for full MS scans was 70,000, while MS/MS scans were conducted at a resolution of 17,500. The sheath gas flow rate was set to 35 arb, and the auxiliary gas flow rate was 10 arb. The ion transfer tube temperature was maintained at 320 °C, while the auxiliary gas temperature was set to 310 °C. A stepped collision energy of 35 eV was applied.

Standard curve construction and phenolic acid content calculation

-

Stock solutions of rosmarinic acid (5.98 mg), ferulic acid (8.27 mg), and caffeic acid (4.80 mg) were accurately weighed and dissolved in chromatographic-grade methanol to a final volume of 50 mL, yielding standard solutions with concentrations of 0.1196, 0.1654, and 0.096 mg/mL, respectively. The standard solutions were serially diluted, and the diluted samples were analyzed via UPLC-MS. Standard curves were constructed by plotting peak area (Y-axis) against standard concentration (X-axis). The concentration of phenolic acid components in the samples was determined using the corresponding calibration equations.

Expression analysis of phenolic acid biosynthetic pathway genes in transgenic hairy roots

-

Total RNA was extracted from −80 °C frozen hairy root samples. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to analyze the expression levels of key genes involved in the biosynthesis of P. frutescens phenolic acids, including Pf4CL, Pf4CH, PfHPPR, PfPAL1, PfRAS, and PfTAT, in transgenic hairy roots overexpressing PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66.

Statistical analysis

-

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM, USA) for statistical calculations, including one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05). Raw data were preprocessed in Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft, USA). Graphs were plotted using OriginPro 2023 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). All the experiments were performed in triplicate and the data presented are the mean values of three determinations. The data were calculated as mean ± standard error (SD).

-

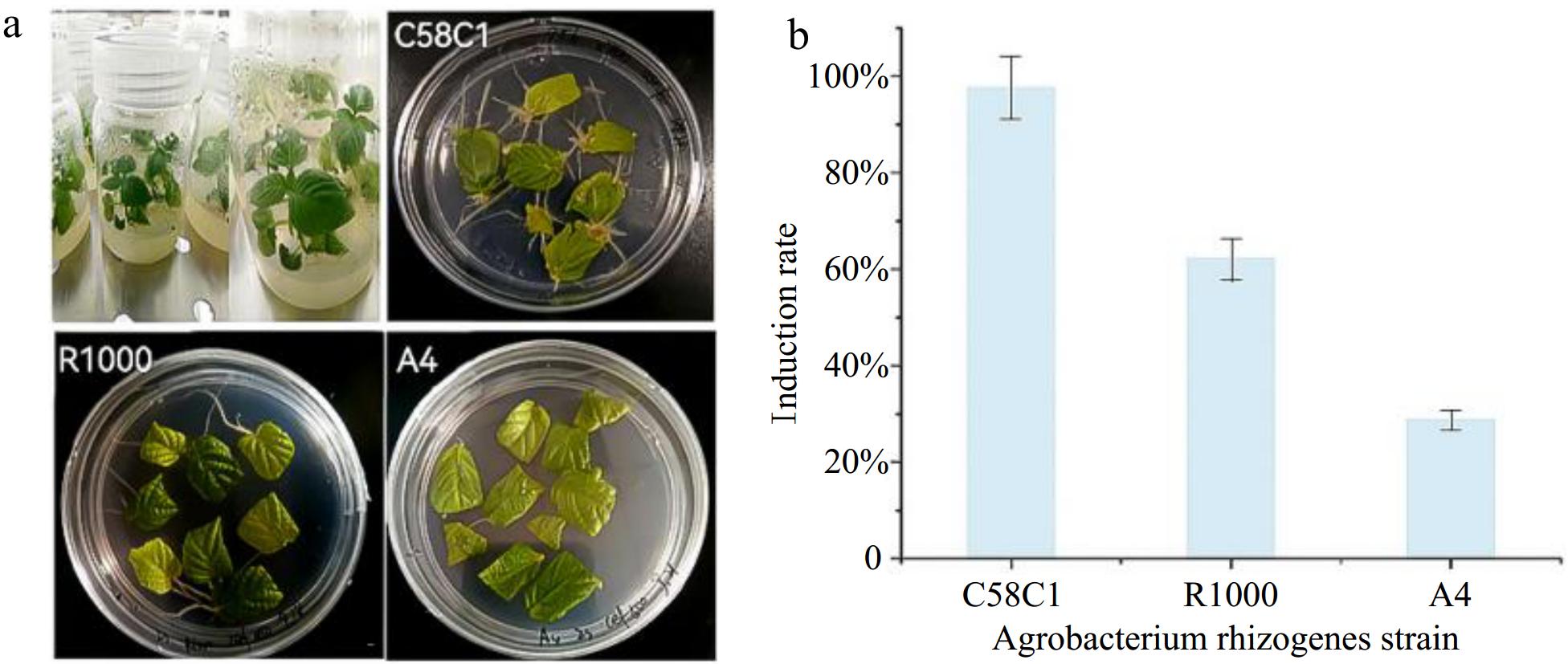

In this study, three different strains of A. rhizogenes, namely R1000, A4, and C58C1, were used for the induction of hairy roots in P. frutescens. The effectiveness of these strains in hairy roots induction was evaluated, and the results showed that there were significant differences in the induction rate of hairy roots among the three strains.

After 15 d of sterilization and cultivation, the number of hairy roots produced by the P. frutescens leaves varied among the different strains, as shown in Fig. 1a. The results indicated that the C58C1 strain had the highest number of hairy roots. During the co-cultivation stage, P. frutescens explants infected with the C58C1 strain had hairy roots growing around the fifth day, with an induction rate of 97.7%. In contrast, P. frutescens explants infected with the R1000 and A4 strains had hairy roots growing around the 10th and 15th d, respectively, with an induction rate of only 63.3% and 28.9%, as seen in Fig. 1b. These findings suggest that the C58C1 strain is more effective than the other two strains in inducing hairy root formation in P. frutescens.

Figure 1.

Leaves of P. frutescens infected by different strains and the induction rate of hairy roots in P. frutescens. (a) Differences in the number of hairy roots on leaves of aseptic seedling cultures of P. frutescens and those infested with different strains of the fungus. (b) Induction of hairy roots in leaves infested with different strains of bacteria.

$ Induction\ rate\ ({\text{%}})\ =\ \dfrac{Number\ of\ hairy\ root\ explants\ produced}{Total\ number\ of\ inoculated\ explants}\times100{\text{%}} $ Effects of different infecting times and co-culture times on hairy roots induction rate

-

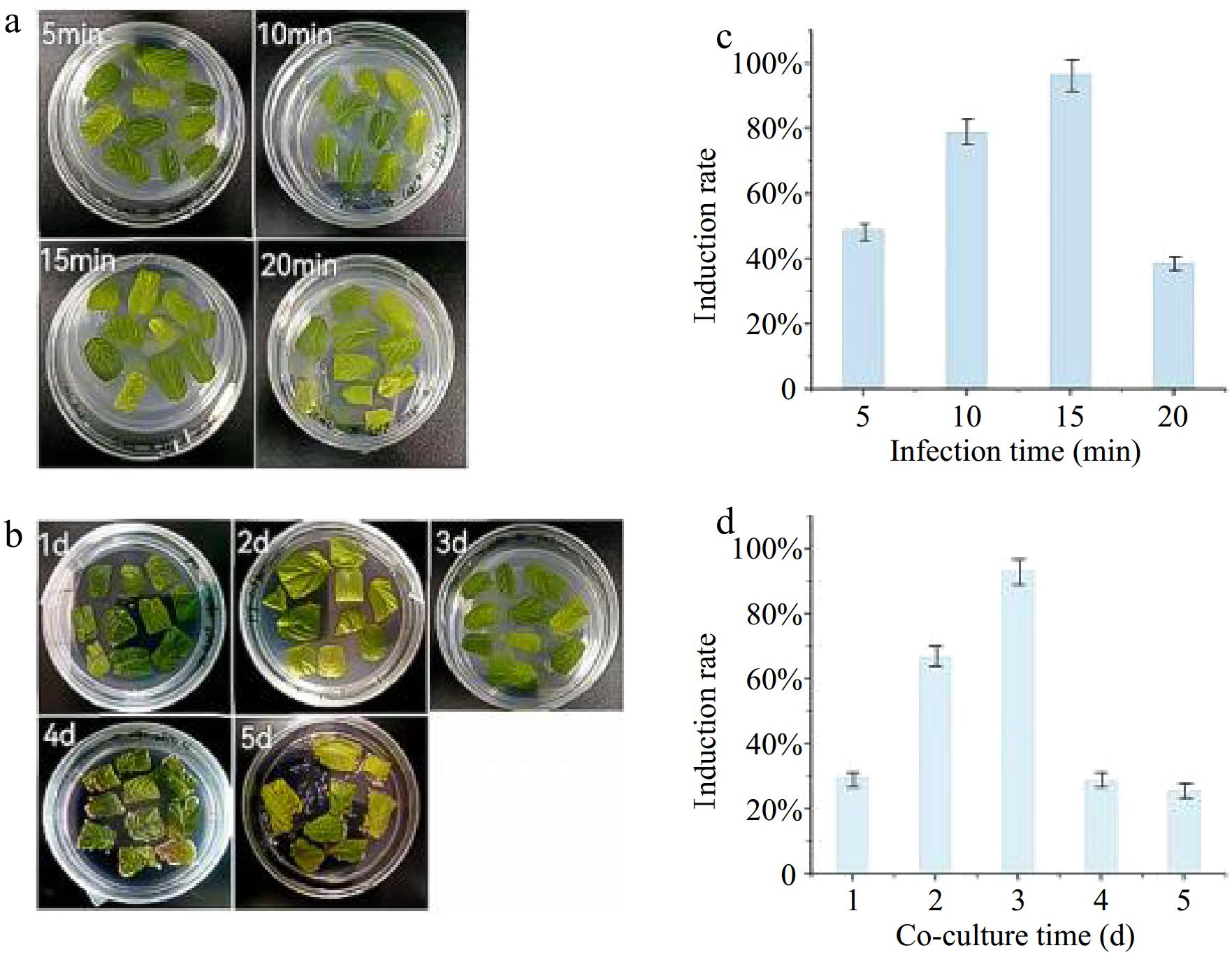

In this study, the inoculation time and co-culture time were also evaluated to determine their effect on the induction rate of hairy roots in P. frutescens (Fig. 2a, b). The results revealed that these factors played a critical role in influencing the success rate of hairy root induction. Regarding infecting time, the C58C1 bacterial solution with an OD value of 0.6-1 was used to infect the leaves of sterile P. frutescens seedlings for different durations. The results showed that the optimal infecting time was 15 min, where the induction rate of hairy roots reached 96.6%, as seen in Fig. 2c. Regarding co-culture time, it was observed that both short and long periods had negative effects on the induction rate of hairy roots. The experimental results demonstrated that a co-cultivation duration of 2–3 d yielded optimal hairy root induction efficiency. However, when the co-cultivation period was extended to 4–5 d, excessive proliferation of A. rhizogenes was observed on the plates (Fig. 2b). Concomitantly, a marked reduction in the induction rate was detected starting from day 4 (Fig. 2d), suggesting that prolonged co-cultivation suppresses genetic transformation efficiency.

Figure 2.

Changes in leaves of P. frutescens at different time of infection and days of co-culture. (a) Changes in leaves at different infection times. (b) Changes in leaves at different co-culture times. (c) Effects of different infection times on trichome root induction rate. (d) Effects of co-culture times on trichome root induction rate.

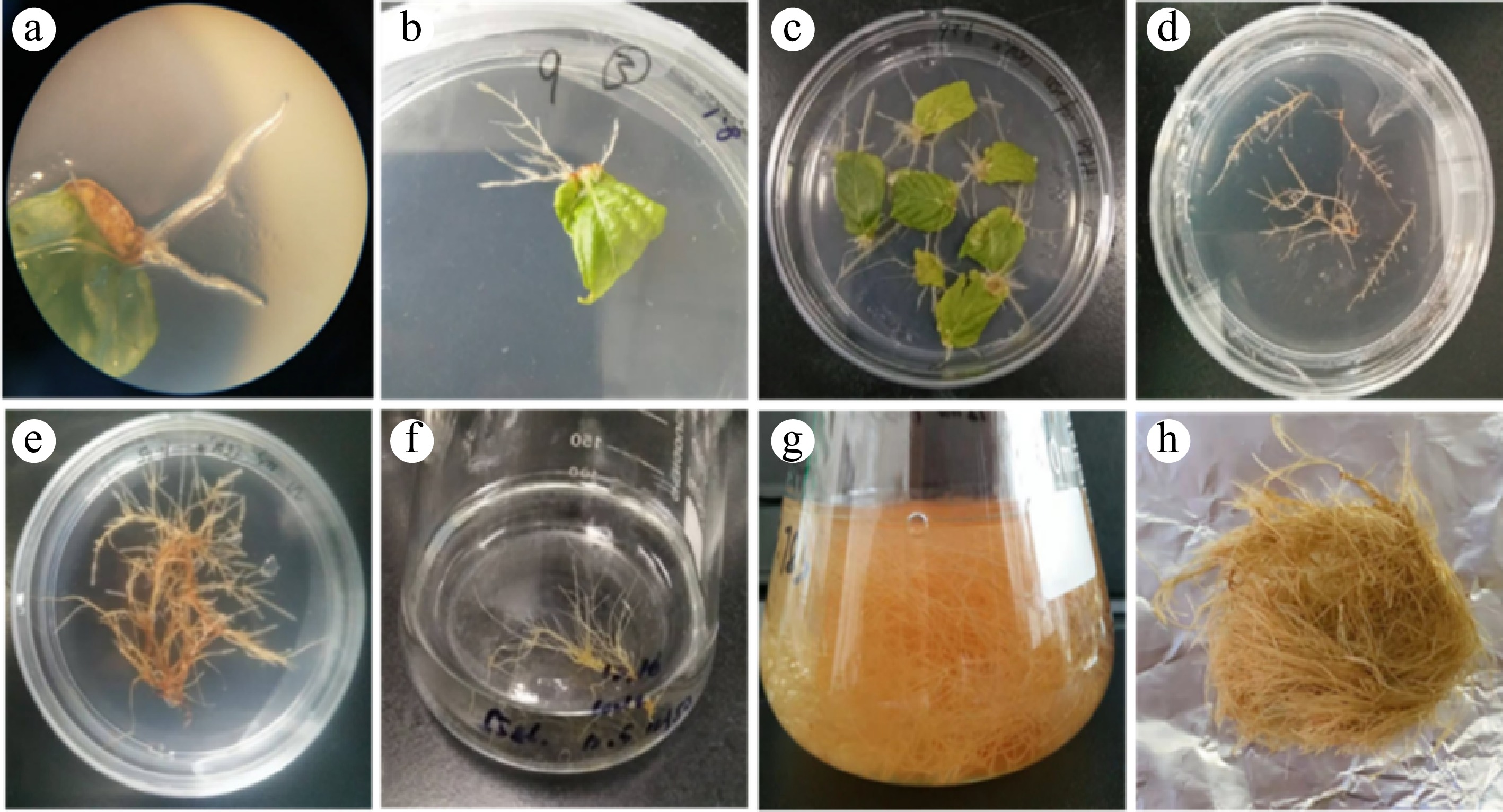

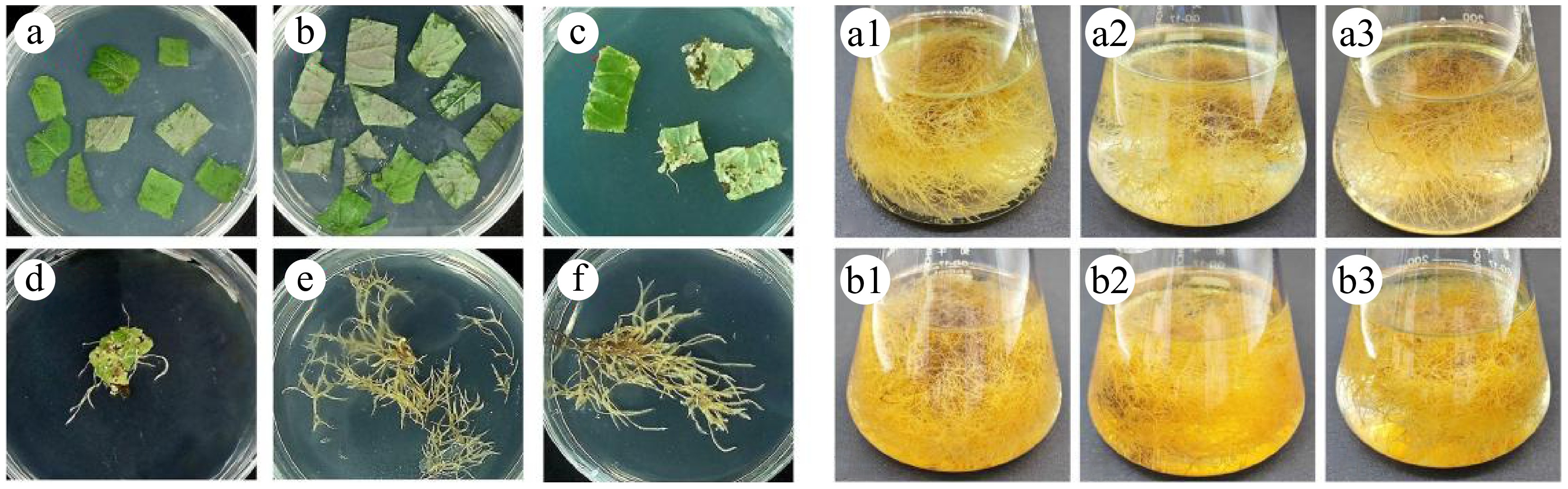

The induction of hairy roots in P. frutescens was visually monitored and documented (as shown in Fig. 3). After infecting the leaves explants with A. rhizogenes C58C1, hairy roots were observed one week later on the wounded petiole, as seen in Fig. 3a and b. Subsequently, many hairy roots appeared after the second or third week of incubation, as shown in Fig. 3c. When the hairy root reached approximately 5 cm in length, fast-growing lines with lateral branches were selected and cultured on solidified MS medium, as seen in Fig. 3d. The hairy roots were subcultured until their fresh weight reached around 0.5 g, which took five weeks to achieve, as shown in Fig. 3e. The hairy roots were then transferred into 1/2MS liquid medium (pH = 5.8), as demonstrated in Fig. 3f. After eight weeks of growth in the liquid medium, the hairy roots of P. frutescens reached a stagnation period, as illustrated in Fig. 3g, h. These observations help to understand the growth pattern of P. frutescens hairy roots during culturing, which could be useful in optimizing conditions for large-scale production of phenolic acids using these hairy root cultures.

Figure 3.

Hairy root induction and culture stages of P. frutescens. (a) internode; (b) hairy root induction; (c) hairy roots growth two weeks after induction; (d) hairy roots growth three weeks reached 5 cm; (e) hairy roots growth six weeks reached 0.5 g; (f) hairy roots transferred from solid to liquid medium; (g) hairy roots growth eight weeks in the liquid medium; (h) hairy roots before drying.

Molecular analysis of hairy roots

-

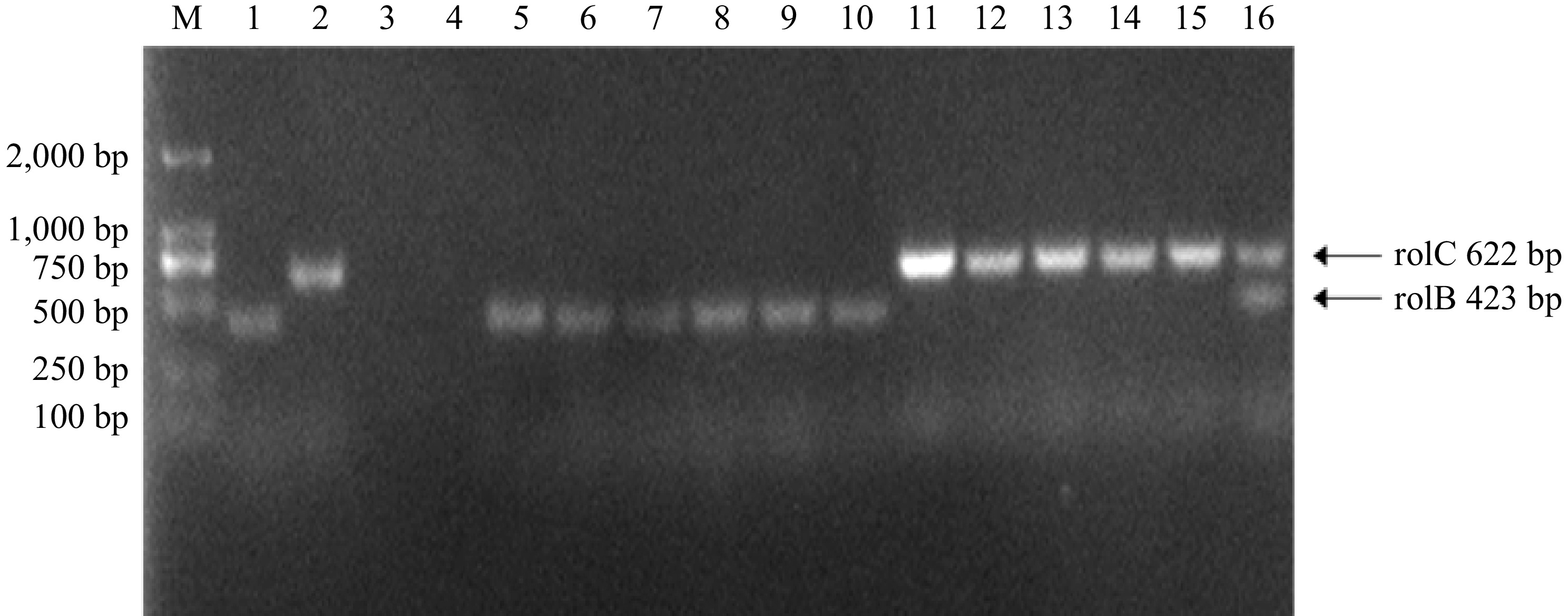

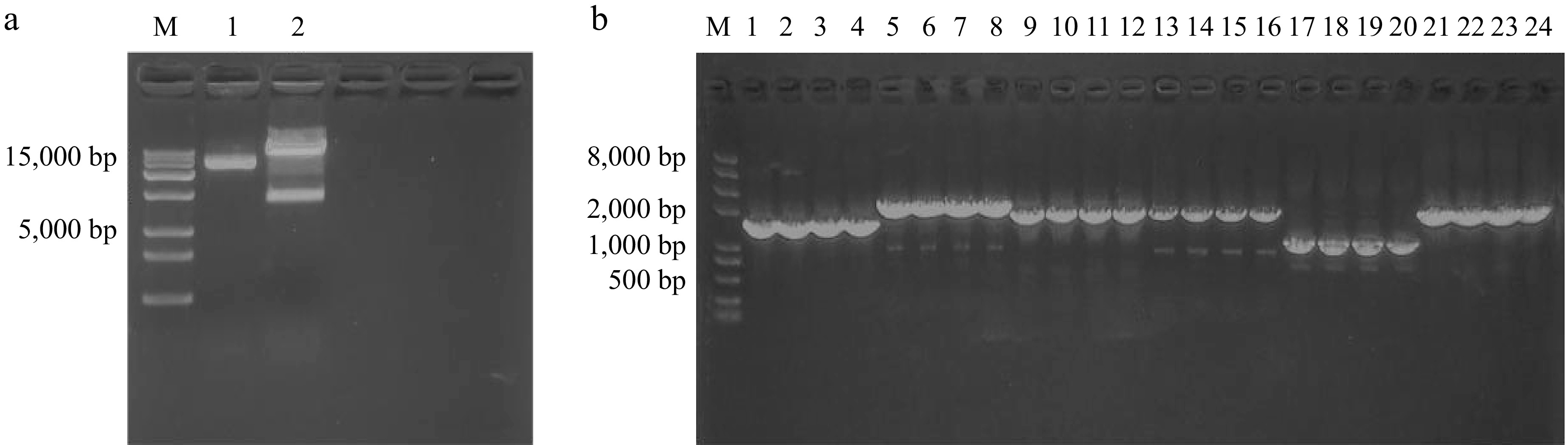

In this study, five fast-growing P. frutescens hairy root lines (P1-P5) were selected for identification. The DNA was isolated from the hairy roots, A. rhizogenes (positive control), and non-transformed sterile seedlings roots (negative control) for PCR analysis. The results showed that plasmid fragments containing genes rolB (423 bp) and rolC (622 bp) were detected in all analyzed P. frutescens hairy root lines and positive controls (A. rhizogenes C58C1 plasmid DNA). However, these fragments were not observed in the negative control (non-transformed sterile seedling roots), as seen in Fig. 4. These findings confirm the successful transformation of the P. frutescens plants with the A. rhizogenes C58C1 strain and indicate that the rolB and rolC genes are present in the five P. frutescens hairy root lines.

Figure 4.

PCR identification of hairy roots, M is the DL2000bp marker; lanes 1 and 2 are a positive control: C58C1 plasmid DNA; lanes 3 and 4 are the negative control: P. frutescens sterile seedling root DNA; lanes 5–16 are hairy root DNA; (lanes 5–10 are the rolB gene, and lanes 11–16 are the rolC gene).

Quantitative analysis

Analysis of the content of phenolic acids in different lines

-

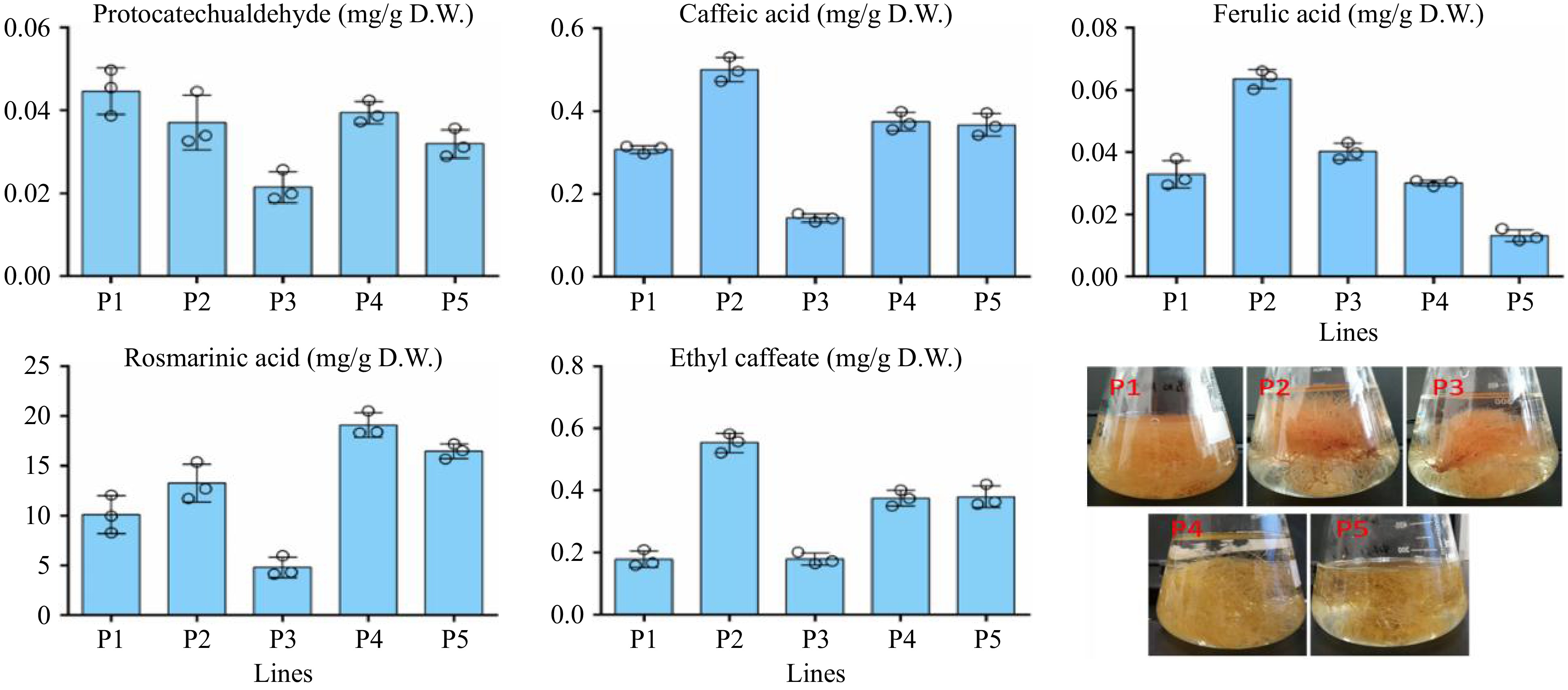

This study also aimed to determine the contents of five phenolic acids, namely protocatechuic aldehyde, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, RA, and ethyl caffeic acid, in the hairy roots of P. frutescens lines P1-P5 using HPLC analysis. The results showed that these phenolic acids exhibited different accumulation patterns in each line. Among the five identified compounds, RA was found to be the predominant compound in the extracts of the P. frutescens hairy roots, with a content range of 4.27 to 19.08 mg/g DW. The highest production of RA was observed in the P4 line (19.08 mg/g DW), as seen in Fig. 5. The content of RA in the P. frutescens hairy roots was about 6.4-fold higher than that reported in a previous study on the roots of the leaves of P. frutescens[20]. Caffeic acid was also detected in the P. frutescens hairy roots, with content ranging from 0.14–0.49 mg/g DW, and the highest amount being observed in the P2 line. The content of ethyl caffeate ranged from 0.16–0.54 mg/g DW. Ferulic acid and protocatechuic aldehyde were also found in the hairy roots, with content ranging from 0.01–0.06 and 0.02–0.05 mg/g DW, respectively, as seen in Fig. 5.

Effect of MeJA and SA induction on phenolic production in P. frutescens hairy roots

-

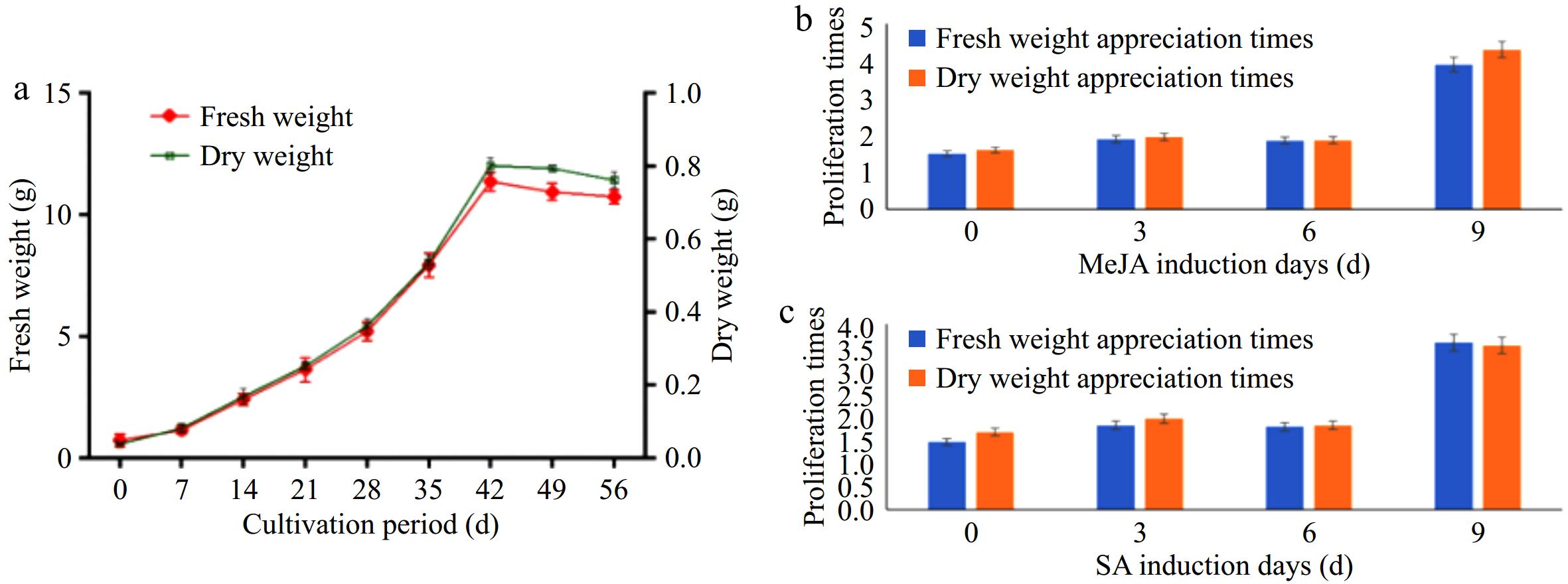

The growth characteristics of P. frutescens hairy roots were studied by cultivating them in 1/2MS medium for 56 d, and samples were taken every seven days to analyze the fresh and dry weight of the hairy roots. The increment curves of both dry and fresh weights were obtained, as seen in Fig. 6a. From the graph, it can be observed that the growth curve of P. frutescens hairy roots is an 'S-shaped' curve. The growth of the hairy roots is relatively slow from 0 to 14 d, followed by a logarithmic growth period from 14 to 42 d. After 42 d, the growth of the hairy roots enters a stagnant period. The fresh weight and dry weight of hairy roots growing in the plateau stage are 14 and 0.9 times higher than those at the beginning, respectively. Therefore, the highest biomass accumulation of hairy roots occurs when they grow for six weeks. The effect of MeJA and SA inducers on the biomass accumulation of P. frutescens hairy roots in liquid culture was also investigated. During the first 6 d of induction treatment with MeJA or SA, the biomass of P. frutescens hairy roots did not change significantly, with a multiplication factor of less than 1.5. However, on the 9th d of induction treatment, their fresh weight multiplication factor reached 3.2, and the dry weight multiplication factor reached 4.7. This indicates that MeJA and SA inductions can promote the growth of P. frutescens hairy roots. The effect of MeJA and SA inducers on the proliferation of dry and fresh weight was not significant until 6 d before induction, after which there was a significant increase in proliferation rate. On the 9th d after treatment, the proliferation rate greatly increased, as seen in Fig. 6b, c. These findings suggest that MeJA and SA treatments could be used to enhance the growth and biomass accumulation of P. frutescens hairy roots in liquid culture.

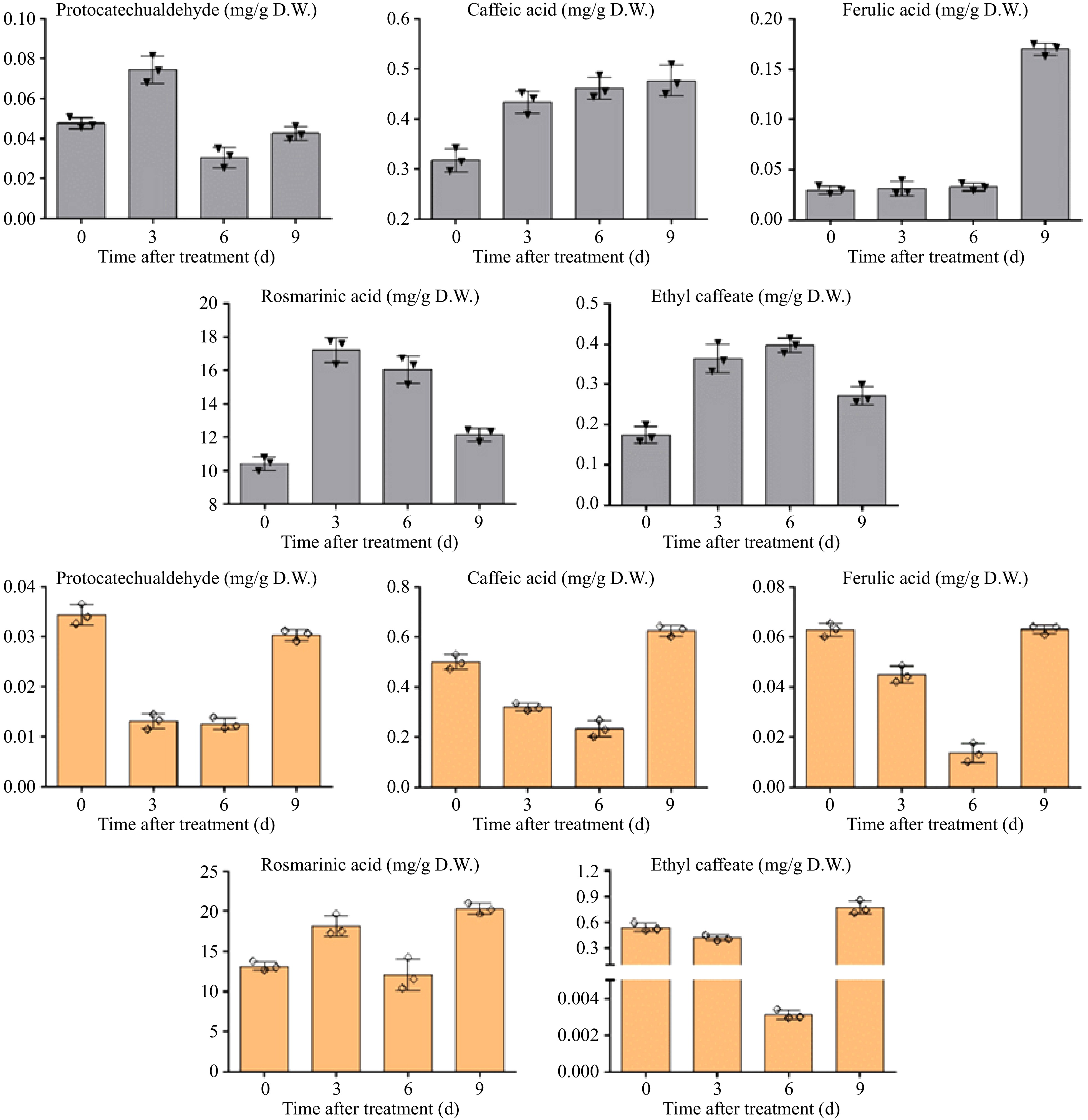

MeJA treatment was found to affect the phenolic acid accumulation in P. frutescens hairy roots. The content of RA was significantly increased after MeJA treatment and reached its maximum (17.36 mg/g DW) on the third day, which was about 1.7-fold higher than that at 0 d, as seen in Fig. 7. Caffeic acid accumulation showed a gradual increase and reached its maximum (0.49 mg/g DW) on the ninth day after MeJA addition. The yield of ferulic acid was also increased to 5.6-fold at 0 d and reached 0.17 mg/g DW. The highest content of protocatechualdehyde (0.08 mg/g DW) was observed on the third day after MeJA treatment, but it decreased significantly on the sixth day. After MeJA treatment, the concentration of ethyl caffeate gradually increased until the ninth day then decreased, and reached its maximum (0.39 mg/g DW) on the sixth day. These findings demonstrate that MeJA treatment could enhance the accumulation of certain phenolic acids in P. frutescens hairy roots, such as RA, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, protocatechualdehyde, and ethyl caffeate. The addition of SA was found to affect the content of the five phenolic acids in P. frutescens hairy roots. Among the five detected compounds, the concentration of RA increased after treatment with SA for nine days and reached its maximum (20.92 mg/g DW), which was about 1.58-fold higher than that of the control samples, as seen in Fig. 7. SA inhibited the accumulation of caffeic acid within six days and then showed a significant enhancement on the ninth day. Finally, a 1.26-fold increase (0.63 mg/g DW) in caffeic acid was observed at nine days compared to the beginning of the experiment. The effect of SA on the content of protocatechualdehyde, ferulic acid, and ethyl caffeate showed a similar pattern as caffeic acid. A prominent decrease appeared during the first six days after treatment; subsequently, they increased on the ninth day and reached their highest levels (0.03 mg/g, 0.06 mg/g, and 0.77 mg/g DW, respectively), as shown in Fig. 7. These results imply that SA treatment could significantly alter the accumulation of certain phenolic acids, such as RA, caffeic acid, protocatechualdehyde, ferulic acid, and ethyl caffeate, in P. frutescens hairy roots. These compounds have been previously reported to possess various medicinal properties, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory effects. Therefore, SA- and MeJA-treated hairy roots may have potential value for the development of natural bioactive compounds for use in the pharmaceutical and food industries.

Figure 7.

Effects of MeJA on the accumulation of phenolic acids in P. frutescens hairy root and effects of SA on the accumulation of phenolic acids in Perilla hairy root.

Induction of transgenic hairy roots, phenolic acid content determination, and expression analysis

Generation and identification of transgenic hairy roots

-

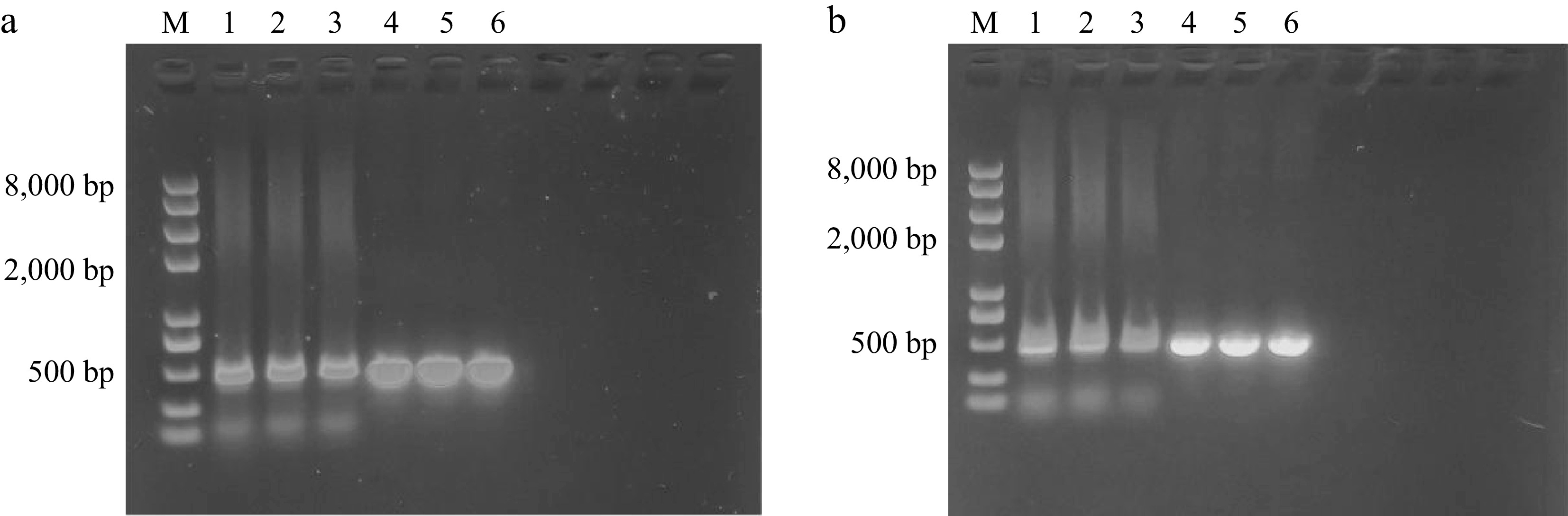

Previous studies by Chen et al.[21] demonstrated that MeJA treatment significantly upregulates the expression of two bHLH transcription factor family members (PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66) in P. frutescens leaves. To investigate the regulatory roles of these bHLH transcription factors in phenolic acid biosynthesis, we constructed plant overexpression vectors for PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 (pCAMBIA1304-PfbHLH13 and pCAMBIA1304-PfbHLH66), as shown in Fig. 8. The recombinant plasmids were introduced into A. rhizogenes strain K599, which was used to induce transgenic hairy roots overexpressing PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 in P. frutescens leaves. Three monoclonal transgenic lines were selected for each construct (PfbHLH13-3, PfbHLH13-5, PfbHLH13-9 and PfbHLH66-2, PfbHLH66-4, PfbHLH66-8), as illustrated in Figs 9, 10.

Figure 8.

Restriction digestion and bacterial identification electrophoresis gel of pCAMBIA1304. (a) Lanes 1 and 2 represent the 1,304 plasmid and the 1304 restriction enzyme digestion products, respectively. (b) Lanes 1–4 show the bacterial identification results for PfbHLH88; Lanes 5–8 show the bacterial identification results for PfbHLH13; Lanes 9–12 show the bacterial identification results for PfbHLH46; Lanes 13–16 show the bacterial identification results for PfbHLH66; Lanes 17–20 show the bacterial identification results for PfbHLH45; Lanes 21–24 show the bacterial identification results for PfbHLH5.

Figure 9.

Growth status of transgenic hairy roots. (a), (b) Perilla leaves during co-cultivation. (c), (d) Perilla leaves at the end of co-cultivation. (e), (f) Transgenic hairy roots. (a1)–(a3) Three PfbHLH13-3/5/9 transgenic hairy root lines. (b1)–(b3) Three PfbHLH66-2/4/8 transgenic hairy root lines.

Figure 10.

PCR identification of transgenic hairy roots. (a) Lanes 1-3 show the PCR results of the rolB gene (405 bp) for three PfbHLH13-3/5/9 transgenic lines; lanes 4–6 show the PCR results of the Hyg gene (535 bp) for the same transgenic lines. (b) Lanes 1–3 show the PCR results of the rolB gene for three PfbHLH66-2/4/8 transgenic lines; lanes 4–6 show the PCR results of the Hyg gene for the same transgenic lines.

Expression pattern analysis of phenolic acid biosynthetic pathway genes

-

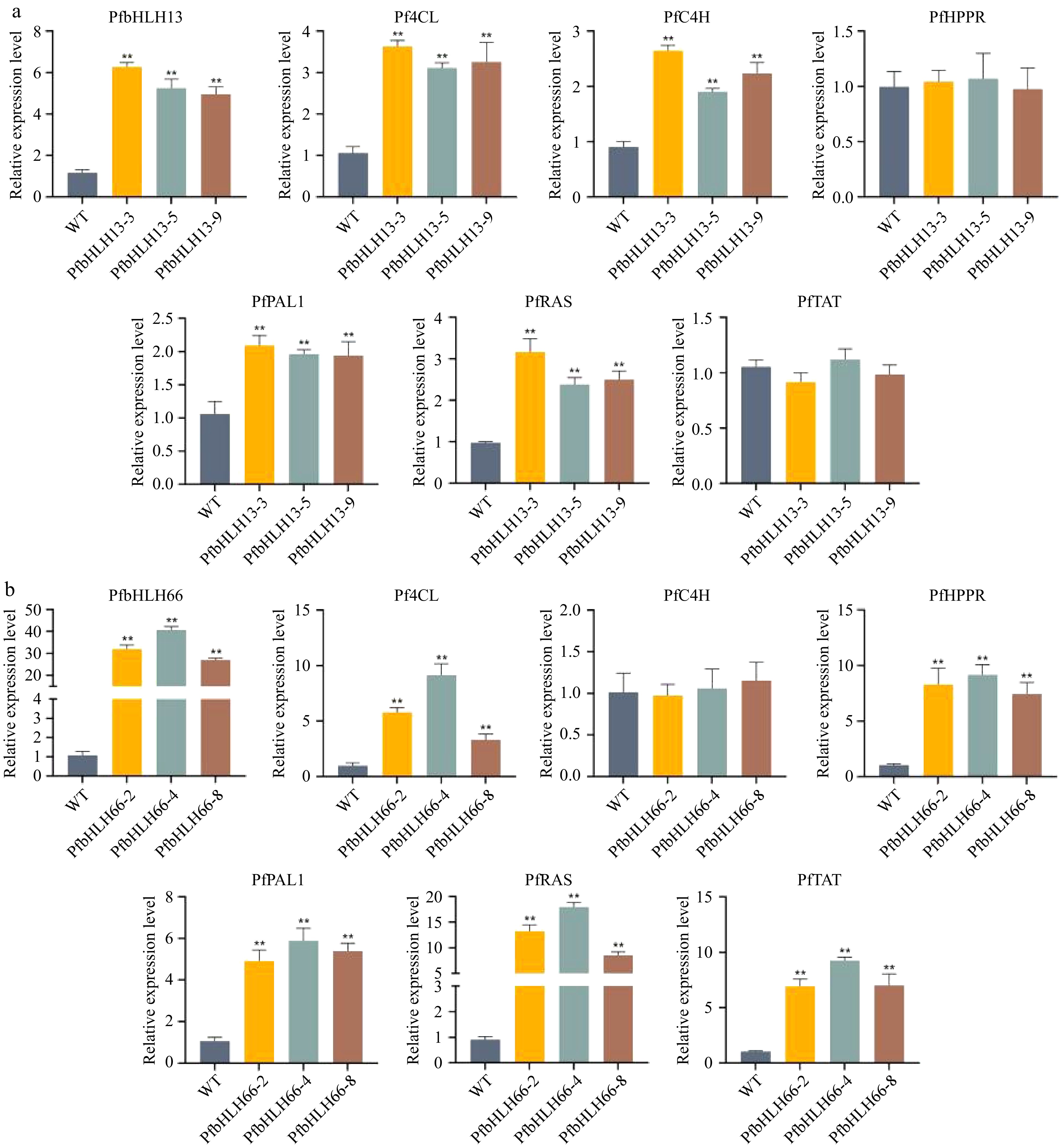

To elucidate the function of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 in phenolic acid accumulation, we performed qRT-PCR analysis using cDNA from wild-type (WT) and transgenic lines (PfbHLH13-3, PfbHLH13-5, PfbHLH13-9, PfbHLH66-2, PfbHLH66-4, PfbHLH66-8). The expression levels of target genes and key genes in the phenolic acid biosynthetic pathway were analyzed (Fig. 11). In PfbHLH13 transgenic lines (Fig. 11a), PfbHLH13 expression was significantly higher than in WT across all three transgenic lines. Additionally, genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway (Pf4CL, PfC4H, PfPAL1, PfRAS) were markedly upregulated in PfbHLH13 transgenic lines, suggesting that PfbHLH13 overexpression may enhance the activity of the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway. However, the expression levels of PfHPPR and PfTAT remained largely unchanged. In PfbHLH66 transgenic lines (Fig. 11b), PfbHLH66 was significantly upregulated in all three transgenic lines compared to WT. The expression of Pf4CL was notably increased in PfbHLH66-2, PfbHLH66-4, and PfbHLH66-8, with the highest level observed in PfbHLH66-2. Additionally, genes including Pf4CL, PfHPPR, PfPAL1, PfRAS, and PfTAT were significantly upregulated in PfbHLH66-2 and PfbHLH66-4, with PfbHLH66-2 showing the highest expression levels. PfC4H exhibited a slight increase in PfbHLH66-2 and PfbHLH66-4 compared to WT, while its expression in PfbHLH66-8 was similar to WT. The PfbHLH66-8 line showed relatively lower expression of most target genes but remained higher than WT. These findings suggest that PfbHLH66 may enhance the activities of both the phenylalanine and tyrosine pathways, thereby promoting the biosynthesis of phenolic acid compounds.

Figure 11.

Gene expression analysis in transgenic hairy roots. (a) Gene expression analysis in three PfbHLH13-3/5/9 transgenic hairy root lines and WT. (b) Gene expression analysis in three PfbHLH66-2/4/8 transgenic hairy root lines and WT. * p < 0.5, ** p < 0.01.

Phenolic acid content analysis in transgenic P. frutescens hairy roots

-

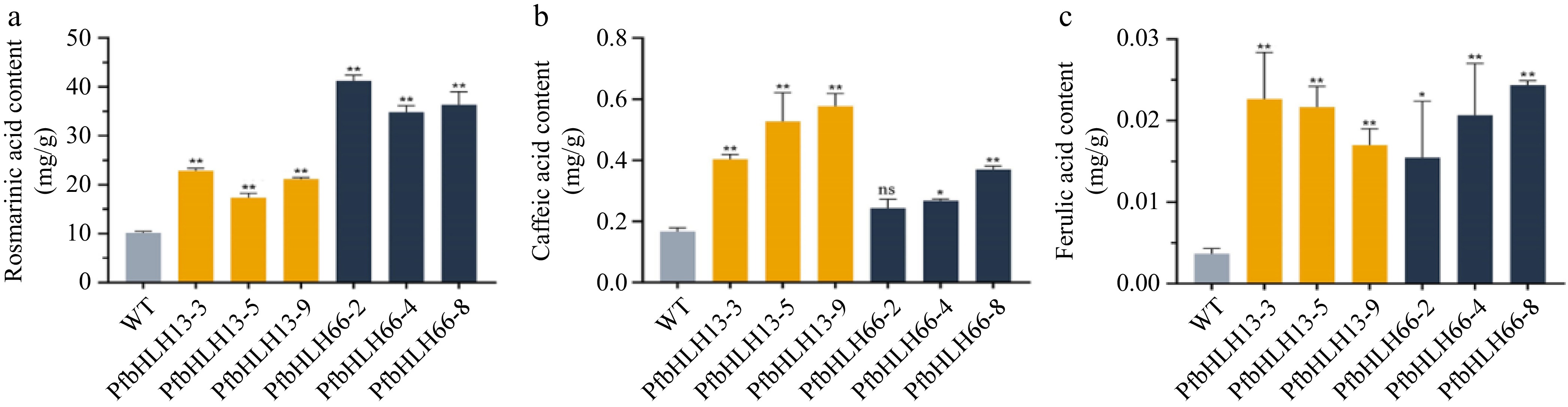

A mixture of standard solutions of rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid was prepared and serially diluted (2.5-fold dilutions). The samples were analyzed by UPLC-MS, and linear regression analysis was performed using peak area (x) and standard concentration (y, mg/mL) (Table 1).

Table 1. Linear relationship of phenolic acid compounds.

Chemical compound Regression equation Linear range (peak area) Regression coefficient Rosmarinic acid y = –4.02E-4 + 3.29E-11x 1.35186E7 ~ 3.64516E9 0.9999 Caffeic acid y = –4.52E-05 + 2.15E-11x 3986496 ~ 1.7685E8 0.9951 Ferulic acid y = –3.07E-06 + 2.07E-11x 354779 ~ 1.03305E7 0.9995 To investigate the effect of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 on phenolic acid biosynthesis in P. frutescens, the phenolic acid content in transgenic hairy roots was quantified using UPLC-MS (Fig. 12). In the WT, the content of rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid was 10.13, 0.17, and 0.0037 mg/g, respectively. In PfbHLH13 transgenic lines (PfbHLH13-3, PfbHLH13-5, PfbHLH13-9), the content of rosmarinic acid was 22.88, 17.37, and 21.2 mg/g; the content of caffeic acid was 0.4, 0.53, and 0.58 mg/g; and the content of ferulic acid was 0.023, 0.022, and 0.017 mg/g, respectively. In PfbHLH66 transgenic lines (PfbHLH66-2, PfbHLH66-4, PfbHLH66-8), the rosmarinic acid content was 41.23, 34.83, and 36.32 mg/g; the caffeic acid content was 0.24, 0.27, and 0.37 mg/g; and the ferulic acid content was 0.015, 0.02, and 0.024 mg/g, respectively. Compared to WT, the overexpression of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 led to a 1.71- to 2.26-fold increase in rosmarinic acid content, a 2.42- to 3.46-fold increase in caffeic acid content, and a 4.64- to 6.18-fold increase in ferulic acid content. These results indicate that PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 play significant regulatory roles in phenolic acid biosynthesis in P. frutescens.

Figure 12.

Quantification of three phenolic acid components in transgenic hairy roots. (a) Rosmarinic acid content in WT and two transgenic systems. (b) Caffeic acid content in WT and two transgenic systems. (c) Ferulic acid content in WT and two transgenic systems. WT: Wild-type; PfbHLH13-3/5/9, PfbHLH66-2/4/8 represent the three transgenic lines of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66, respectively; ns, no significance; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

-

The use of hairy root cultures for the production of bioactive compounds in pharmaceuticals has been extensively reported in the literature. For instance, Trachyspermum ammi hairy roots can produce thymol[22], Gymnema sylvestre hairy roots can produce gymnemic acid[23], and Artemisia hairy roots can produce phenol, flavonoid, sterol, and essential oil[24]. Furthermore, Salvia viridis hairy roots can be utilized to produce polyphenolic compounds[25], Brugmansia candidas hairy roots can produce tropane alkaloids[26], Rehmannia elata hairy roots can produce iridoid and phenylethanoid glycosides[27], and Corylus avellana hairy roots can produce saponins[28]. These examples demonstrate the potential of using hairy root cultures to produce a variety of bioactive compounds for multiple applications.

In our study, we successfully established a rapid and efficient system for cultivating P. frutescens hairy roots for the first time, allowing us to investigate the accumulation of phenolic acids in these roots. Our results revealed that compared to the original P. frutescens plants, the cultivated hairy root showed a higher yield of valuable secondary metabolites that could serve as a consistent resource for producing pharmaceutical components. Specifically, HPLC analysis of the hairy roots demonstrated that RA was the predominant compound in the extract. The content of RA in the hairy roots was six times higher than that found in the original plants (P. frutescens leaf)[20,29]. P. frutescens hairy root cultures are an efficient system for producing plant secondary metabolites, offering several unique advantages, particularly in cost control and cultivation conditions. The hairy root culture system is simple and easy to operate, making it highly suitable for large-scale production. It requires minimal cultivation conditions, is highly adaptable, has a high survival rate, and is genetically stable, making it ideal for industrial-scale production. The secondary metabolites in P. frutescens hairy roots possess a range of pharmacological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties, which make them highly applicable in the pharmaceutical field. The genetic stability of the hairy roots makes them a sustainable source of natural products, capable of replacing traditional cultivation or wild resource harvesting to meet the market demand for high-value natural products.

Hairy root cultures not only efficiently accumulate a variety of bioactive phenolic compounds but also hold great potential as a source of natural bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical and industrial applications. The study further confirms the high efficiency of the hairy root system in synthesizing secondary metabolites, particularly in the production of high-value natural products. By optimizing processes such as sterile seedling preparation, A. rhizogenes transformation, preculture, co-culture, sterilization screening, and scale-up culture, stable and efficient production of secondary metabolites can be achieved. Hairy root cultures provide a rich source of active ingredients for the pharmaceutical industry and serve as a sustainable source of natural bioactive compounds for industrial applications. This highly efficient and genetically stable culture system lays a solid foundation for the development of novel drugs and functional products, while also offering new insights into the biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites. Of note, only a handful of medicinal plants or hairy roots have been reported to contain higher levels of RA than P. frutescens hairy roots. For instance, S. viridis hairy roots contained 35.6 mg/g DW of RA[25], S. bulleyana hairy roots contained 39.6 mg/g DW of RA[11], and Dracocephalum moldavica contained 38.9 mg/g DW of RA[30]. In contrast, the RA content in Ocimum basilicum was only 1.7 mg/g of FW[31]. These findings suggest that P. frutescens hairy roots hold significant potential for RA production when compared to other medicinal plants.

Elicitors, which are compounds that induce stress-related responses and developmental processes in plants have become increasingly popular in recent years as effective promoters of secondary metabolite production in hairy root cultures. For example, MeJA has been shown to promote the phenolic content in Mentha spicata[32], O. basilicum[31] enhances the production of triterpenoids in hairy roots of Centella asiatica[33] and terpenoid indole alkaloids in Rhazya stricta[34]. Additionally, MeJA has been found to improve tanshinones' content in S. miltiorrhiza hairy roots[35]. SA has also demonstrated potential as an elicitor for promoting secondary metabolite production in hairy roots. Moreover, Ag+ and yeast have been found to promote tanshinone accumulation in S. miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures[36,37].

In our study, treatment with MeJA resulted in a remarkable accumulation of RA in P. frutescens hairy roots on day three, with yields of 17.36 mg/g DW for RA and 0.08 mg/g DW for protocatechuic aldehyde. Caffeic acid and ferulic acid contents reached their maximum levels on day nine, while ethyl caffeate levels were increased by MeJA on day six but decreased on day nine. These findings suggest that MeJA can promote the rapid accumulation of RA in a short period (3 d) while inhibiting its accumulation over an extended period. These results are consistent with previous studies conducted using S. miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures[14,35] and S. przewalskii hairy root cultures[38].

Our results showed that treatment with SA led to more dramatic changes in the production of phenolic compounds in P. frutescens hairy roots. The content of RA was found to reach its maximum level on day nine (20.92 mg/g DW). In comparison to MeJA treatment, SA treatment did not stimulate the production of protocatechuic aldehyde and ferulic acid. On the other hand, the accumulation of caffeic acid and ethyl caffeic acid was suppressed by SA treatment on day three and day six but reached their maximum yields at the end of the treatment stage (day nine), with maximum yields of 0.63 and 0.77 mg/g DW (1.26-fold and 1.43-fold of the control), respectively. The accumulation trends observed in our study suggest that SA has a promoting effect on the accumulation of RA, which is consistent with previously reported results in S. przewalskii hairy roots[38]. These findings indicate that SA could be a valuable elicitor in enhancing the yield of RA in P. frutescens hairy root cultures. This information contributes to the understanding of the mechanisms underlying SA-induced secondary metabolism in plants, providing insight into new approaches for plant cell culture-based bioproduction of bioactive compounds.

Analysis of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 transgenic hairy roots revealed a significant increase in the accumulation of phenolic acid compounds (rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid) compared to the wild type (WT). qPCR results further confirmed that the expression levels of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 were markedly upregulated in their respective transgenic lines. In PfbHLH13 transgenic lines, several key genes in the phenylpropanoid pathway, including Pf4CL, PfC4H, PfPAL1, and PfRAS, were significantly upregulated relative to the control group, suggesting that PfbHLH13 may play a positive regulatory role in the expression of specific genes within the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway. Similarly, in PfbHLH66 transgenic lines, the majority of key phenylpropanoid pathway genes, such as Pf4CL, PfPAL1, PfRAS, PfTAT, and PfHPPR, were significantly upregulated, whereas PfC4H expression remained largely unchanged. These findings suggest that PfbHLH66 may enhance the accumulation of phenolic acids by regulating multiple key genes in both the phenylpropanoid and tyrosine biosynthetic pathways. bHLH transcription factors play a crucial role in the synthesis of plant secondary metabolites. For example, studies have shown that the Ib (2) family member SmbHLH92 regulates the synthesis of phenolic acids by modulating enzyme activities in the biosynthetic pathway of salvianolic acid[39]. SmbHLH60 is involved in the biosynthesis of phenolic acid components in Solanaceae plants under MeJA induction[40], while SmbHLH148 activates the biosynthesis pathways of phenolic acids and tanshinones under the combined induction of ABA and MeJA, promoting the synthesis of both components[41]. Additionally, bHLH transcription factors in potatoes regulate the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds in response to various environmental signals and plant hormones. These studies highlight the key role of bHLH transcription factors in the regulation of plant secondary metabolism.

-

In summary, this study represents the first report on the establishment of P. frutescens hairy roots and the determination of phenolic acid accumulation in these roots. The content of RA in hairy root cultures was found to be much higher than that of the original plant, with a maximum yield of 19.084 mg/g. This finding highlights the potential of P. frutescens hairy roots as a source of RA production.

Furthermore, our results suggest that elicitor treatment with MeJA or SA can affect the accumulation of phenolic acids in P. frutescens hairy roots. MeJA treatment promoted RA accumulation in a short period pattern, while SA treatment showed a more continuous pattern. The maximum RA content after MeJA treatment was 17.364 mg/g at three days, while the maximum RA content after SA treatment was 20.919 mg/g at nine days. These findings demonstrate the flexible regulation strategies that can be employed for RA production in P. frutescens hairy root cultures. Overall, the establishment of P. frutescens hairy roots and the elucidation of elicitor-induced RA production provides valuable insights into plant cell culture-based bioproduction of bioactive compounds. Our results also offer a foundation for future studies aiming to explore alternative strategies for enhancing the yield of RA and other valuable metabolites using hairy root cultures.

Based on the findings of Chen et al.[21] we selected PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66, which were significantly upregulated upon MeJA treatment, for functional analysis by generating transgenic hairy roots using plant expression vectors. The results showed that, compared to the wild type, the transgenic lines exhibited varying degrees of increase in phenolic acid compounds (rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid), with the most pronounced changes observed in rosmarinic acid levels. Gene expression analysis of the transgenic hairy roots suggested that PfbHLH13 may promote the accumulation of phenolic acids primarily by regulating the expression of phenylpropanoid pathway genes, whereas PfbHLH66 appears to exert its regulatory effects through both the phenylpropanoid and tyrosine biosynthetic pathways. In conclusion, functional characterization of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 through the transgenic hairy root system not only provides new insights into the regulatory mechanisms governing phenolic acid biosynthesis in P. frutescens but also holds significant potential for the industrial-scale production of secondary metabolites to meet commercial demands.

This research was funded by the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Project (20210101190JC), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1600900).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, manuscript review: Xu J, Huang X, Chen J, Shen Q, Hu R, Wang P, Yan Y, Di P; experiments conceived and design: Di P; material preparation, data collection and analysis: Huang X, Shen Q, Hu R, Wang P; draft manuscript preparation: Yan Y. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

The authors confirm that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jiayi Xu, Xinyi Huang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xu J, Huang X, Chen J, Shen Q, Hu R, et al. 2025. Establishment of hairy roots culture of Perilla frutescens L. and production of phenolic acids. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e018 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0017

Establishment of hairy roots culture of Perilla frutescens L. and production of phenolic acids

- Received: 03 December 2024

- Revised: 22 April 2025

- Accepted: 27 April 2025

- Published online: 26 May 2025

Abstract: Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt., a plant rich in phenolic acids, contains rosmarinic acid (RA) as its main phenolic component. RA exhibits various pharmacological activities, including anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects. In this study, we established hairy root cultures of P. frutescens using Agrobacterium rhizogenes strains C58C1, A4, and R1000, and assessed phenolic acid content. Among the strains, C58C1 yielded the highest number of rooted explants and the highest induction rate, with the RA content reaching 19.08 mg/g DW in the fastest-growing lines. We also investigated the effects of salicylic acid (SA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) on phenolic acid accumulation in hairy roots. SA treatment promoted RA accumulation, reaching 20.92 mg/g DW on day nine, while MeJA increased RA to 17.36 mg/g DW on day three, followed by a decline to 4.27 mg/g DW by day nine. Furthermore, transgenic analysis of PfbHLH13 and PfbHLH66 transcription factors showed that overexpression of these genes significantly increased RA content. Quantitative real-time PCR revealed that PfbHLH13 enhances phenolic acid accumulation by regulating the phenylpropanoid pathway, while PfbHLH66 influences both the phenylpropanoid and tyrosine-derived pathways. These findings highlight the potential of P. frutescens hairy roots for large-scale RA production.

-

Key words:

- Perilla frutescens /

- Hairy roots /

- Rosmarinic acid /

- Methyl jasmonate /

- Salicylic acid