-

London plane tree (Platanus × acerifolia Willd., family Platanaceae) belongs to the early derived eudicot clades[1,2]. The tree is grown widely worldwide, being used for road-side avenue plantings. This popularity reflects a number of desirable morphological and physiological traits such as a rapid growth habit, excellent shading capacity, attractive autumn leaves, and also a high capacity for the extraction of air-borne dust particles as well as urban noise reduction[3]. However, a major drawback to urban plantings of London plane trees is the abundant release of pollen and achene fibers from April to May, which can cause human respiratory difficulties and skin allergies[4−6].

Platanus pollen has been recognized as both a potent aeroallergen and an emerging environmental health hazard of global significance[7]. Unlike the reduced perianth structures, Platanus anthers exhibit extreme developmental elaboration and produce densely aggregated pollen grains at maturity. Each staminate inflorescence of the plant tree releases approximately 3.3 × 106 pollen grains[8]. Current research has identified at least seven distinct allergenic proteins (designated Pla a 1–Pla a 7) in this pollen source[9−11], revealing a complex allergenic profile that exacerbates sensitization risks in at-risk demographics. Studies employing geospatial modeling have established significant correlations between Platanus stand density, flowering phenological patterns, and atmospheric pollen load dynamics[4,12−14]. They recommended reassessing the suitability of Platanus spp. as urban landscaping species, and proposed designing low-pollen corridors through urban planning to minimize allergenic particle dispersion and enhance atmospheric quality standards. However, such adaptive measures would inevitably decrease the species' current utilization rate in urban greening initiatives. Consequently, breeding hypoallergenic Platanus cultivars through advanced breeding technologies has emerged as the most sustainable solution to this environmental health challenge.

Polyploidization, the process of whole genome duplication (WGD), drives the evolution of both wild and cultivated plants[15,16]. From the perspective of agricultural trait improvement, polyploid organisms exhibit remarkable 'polyploid vigor', e.g., characterized by gigas effects (organ gigantism), enhanced stress resistance, and increased accumulation of secondary metabolites[17−20]. These advantageous traits explain the widespread prevalence of polyploids among major crop species. Nevertheless, the meiotic stability of polyploids—particularly neopolyploids—is compromised by the presence of additional chromosome sets[16]. The coexistence of multiple homologous chromosomes often leads to multivalent formation during meiosis, resulting in chromosome missegregation, reduced pollen production, and impaired fertility[21,22]. Interestingly, this meiotic instability could be leveraged as a potential strategy for breeding novel pollen- and achenes-free Platanus varieties.

P. × acerifolia is an ancient hexaploid with three subgenomes[2]. In the year 2000, four dodecaploid plants of P. acerifolia were successfully obtained through the in vivo application of colchicine[3]. 'HP' is one of the dodecaploid plants with much fewer flowers and fruits than hexaploid plants. This accession is considered to be of particular interest because of the significantly reduced levels of pollen numbers and fertility. This study demonstrates that the reduced fertility in the 'HP' line mainly stems from meiotic abnormalities induced by polyploidization, including aberrant chromosome pairing, disordered chromatid segregation, and unequal nuclear division, which ultimately leads to developmental defects in microsporogenesis. These findings provide a theoretical breakthrough for polyploid breeding, as the conventionally perceived disadvantage of meiotic instability can now be innovatively repurposed as an effective tool for developing male-sterile Platanus varieties.

-

The dodecaploid 'HP' line of London plane tree, growing in Wuhan, China, was originally induced through colchicine treatment in 2000. The line had been maintained for 23 years prior to this study. Two hexaploid lines ('WT') with normal flowering characteristics were employed as controls. All plant materials were field-grown at the Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China. Chromosome numbers were determined in shoot apical meristem cells following the method of Liu et al.[23], with at least 10 cells examined per sample.

Pollen fertility determination

-

Pollen fertility levels were evaluated using in vitro pollen germination assays. Ten mature male inflorescences were collected from each of the two hexaploid wild-type ('WT') lines and the dodecaploid 'HP' line of P. × acerifolia. Pollen grains from dehiscent anthers were cultured in germination medium (i.e., 10% sugar and 0.01% boric acid) at 25 °C for 24 h. Successful germination was defined according to the criterion that the length of the pollen tube was greater than the diameter of the original pollen grain. For each genotype, 50 replicate observations were carried out, with each observation assessing 40−50 pollen grains.

Histological analysis of anther development

-

To observe anther development, flower buds from two hexaploid 'WT' lines and the dodecaploid 'HP' line were collected, spanning developmental stages from the early primordium stage through mature pollen release. For histological analysis, the male flowers at each developmental stage were sampled and fixed in FAA solution [90 mL ethanol (70%, v/v), 5 mL acetic, and 5 mL formalin] for 24 h, followed by storage in 70% ethanol at 4 °C. Fixed samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 8 μm thickness using the method of Bell[24]. Finally, the sections were stained with 0.1% Toluidine Blue solution and photographed for histological observation.

Scanning electron microscopy of mature pollen grains

-

Mature pollen grains collected from the dehiscent anthers of the trees were fixed overnight in FAA and prepared for scanning electron microscopy following Echlin's protocol[25]. The samples were examined using a scanning electron microscope (ETEC, HITACHI SU8010) at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV.

Meiosis behavior observation

-

Inflorescences were selected at the appropriate stage (Fig. 1c) and fixed in Carnoy's solution (ethanol : acetic acid, 3:1) for 24 h, followed by storage in 70% ethanol at 4 °C until required. The anthers were hydrolyzed in 1N HCl for 6 min at 60 °C. The microspore mother cells (MMCs) were extracted from the squashed, hydrolyzed anthers using a needle, and stained with carbol fuchsin solution. About 100 meiocytes from each sample were tested to observe chromosome morphology at each stage of the microsporogenesis process.

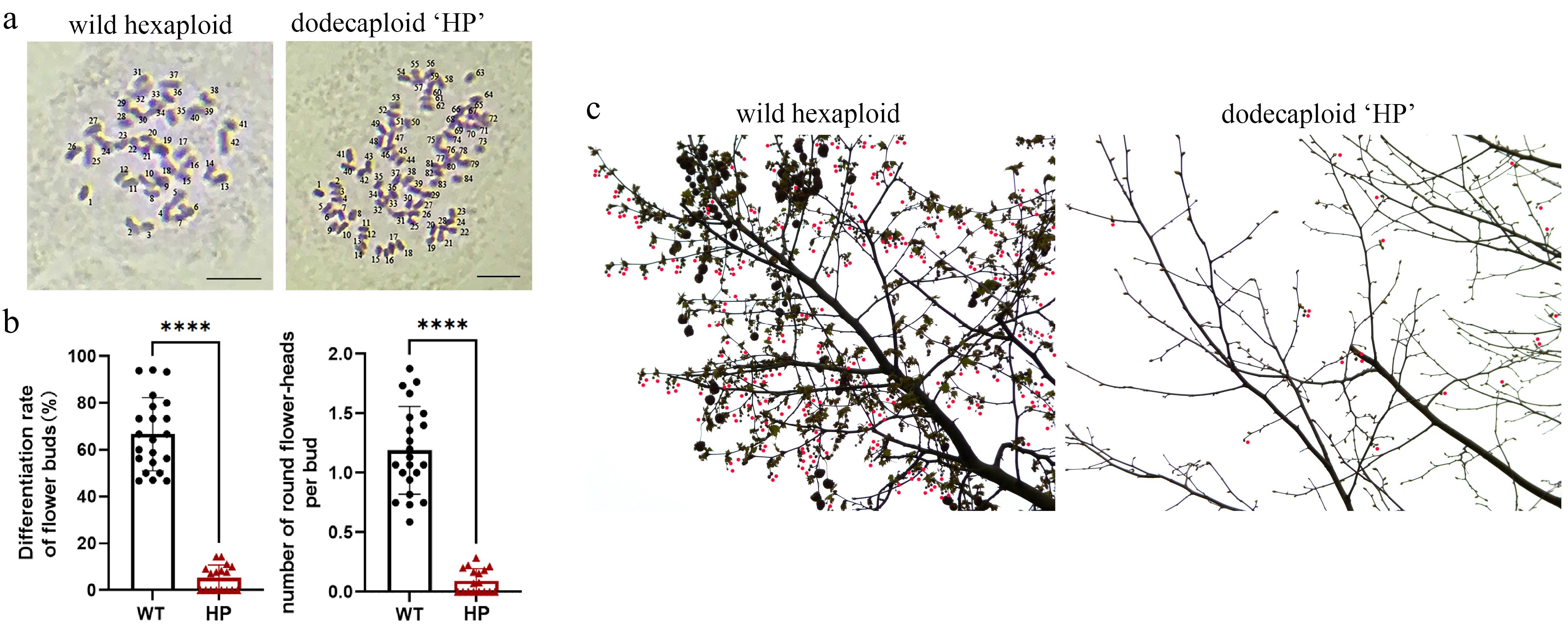

Figure 1.

Comparative reproductive phenotyping between polyploid 'HP' and wild-type P. × acerifolia. (a) Ploidy verification. Chromosome number of bud primordia cells were observed in wild-type P. × acerifolia (left) and 'HP' line (right). Scale bars = 5 μm. (b) Quantitative assessment of reproductive efficiency. Flower bud differentiation frequency (% of total buds) and mean inflorescence count per bud were analyzed in 'WT' and 'HP' lines. Student's t-test of 20 biological replicates; Error bars indicate ± SD; **** p < 0.0001. (c) Inflorescence distribution on mid-crown branches of 'WT' and 'HP' lines. Wild-type displayed characteristic high-density floral clusters, while the 'HP' line exhibited significantly reduced flowering sites. Red dots indicate globose inflorescence.

Seed germination percentage of 'HP'

-

The corns were sampled from the two 'WT' lines and the 'HP' line at the fruit mature stage. Seeds stripped from these corns were cultured in the laboratory dishes with moist filter papers. The culture dishes were incubated in light growth incubators, and watered frequently to keep the filter papers wet. One month later, the germination rates of London plane seeds per corn were scored.

Data analysis and photomicrographs

-

The data obtained were statistically analyzed by PROC ANOVA (analysis of variance) in SPSS software (IBM Corp., version 18.0), with the LSD (least significant difference) test applied at a 5% significance level[26]. Percentage data were transformed via arcsin before analysis. Photomicrographs of pollen germination morphology were made from freshly prepared slides using an OLYMPUS-SZX16 stereo microscope. Photomicrographs of chromosome morphology and observations of paraffin sections were taken with a Nikon Eclipse 80i optical microscope.

-

P. × acerifolia 'HP' is one of the dodecaploid plants obtained by colchicine treatment in 2000. The chromosome number of the wild P. × acerifolia plant ('WT') is 2n = 6x = 42, whereas the dodecaploid line 'HP' contains 2n = 12x = 84 chromosomes (Fig. 1a). As an adult London plane plant, 'HP' has far fewer inflorescences and fruits than wild-type plants. According to statistics, over 66.7% of buds in wild plane trees could differentiate into flower buds (Fig. 1b, c). Thus, one adult London plane plant could reproduce approximately hundreds of fruits (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, the 'HP' line produces only 5.3 flower buds (about 9.2 cone inflorescences) per 100 buds (Fig. 1b, c), and yielded only 3−6 fruits per year (Supplementary Fig. S1).

'HP' exhibits severe male gametophytic defects

-

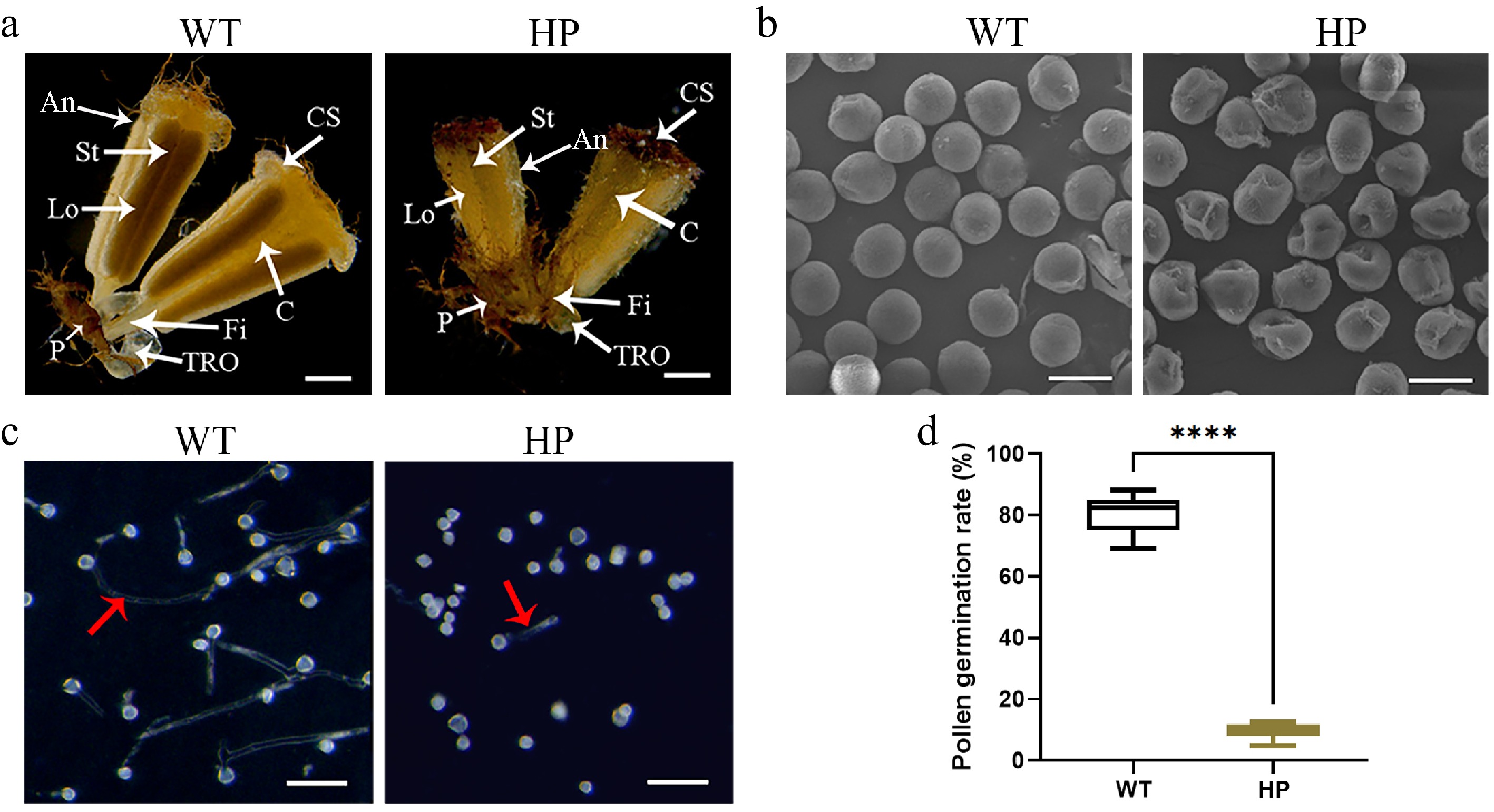

Platanus spp. are monoecious plants bearing unisexual male inflorescences composed predominantly of pollen-producing stamens. Compared to the wild type, the stamens of the 'HP' line exhibited reduced size (Fig. 2a). The morphologies of the pollen grains from 'WT' and 'HP' plants were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The 'WT' pollen grains were spherical and plump in appearance, with clearly visible apertures through which the pollen tubes would emerge. By contrast, 'HP' pollen grains displayed shrunken phenotypes (Fig. 2b), indicating potential impairment in pollen viability. Individual pollen grains in which the length of the germinating pollen tube exceeded the diameter of the pollen grain were generally viable. Whereas those that produced only a short pollen tube or none at all were nonviable. Measurement of pollen grain germination in vitro showed that 'WT' pollen was almost fully fertile, whereas the polypoid line showed significant levels of pollen sterility (Fig. 2c). Specifically, 80.52% ± 5.49% of pollen grains from hexaploid 'WT' plants had produced extended pollen tubes following a 24 h culture period. In contrast, the dodecaploid 'HP' line showed germination in just 9.54% ± 2.45% of pollen grains (Fig. 2d). The seed germination rate of 'HP' was also decreased to 6.85 ± 0.95%, compared to the 'WT' lines (39.67% ± 6.84%, Supplementary Fig. S2a, S2b). The impaired seed germination observed in the 'HP' line is likely attributable to defective pollination and fertilization, which stem from diminished pollen viability.

Figure 2.

Pollen fertility analysis in wild-type ('WT') and polyploid ('HP') London plane tree. (a) Morphology of male flowers in 'WT' and 'HP'. Key floral structures: An, anther; C, connective; CS, cap structure; Fi, filament; Lo: locule; P, perianth; St, stomium; TRO, three-ridged organ. Scale bar = 1 mm. (b) Scanning electron micrographs of pollen grains. Scale bar = 20 μm. (c) In vitro pollen germination assays. Red arrow indicates pollen tubes. Scale bar = 100 μm. (d) Comparative analysis of pollen germination rate in 'WT' and 'HP' (mean ± SD; n = 4 flowers, more than a thousand pollens were analyzed).

Developmental staging of stamen in London plane tree

-

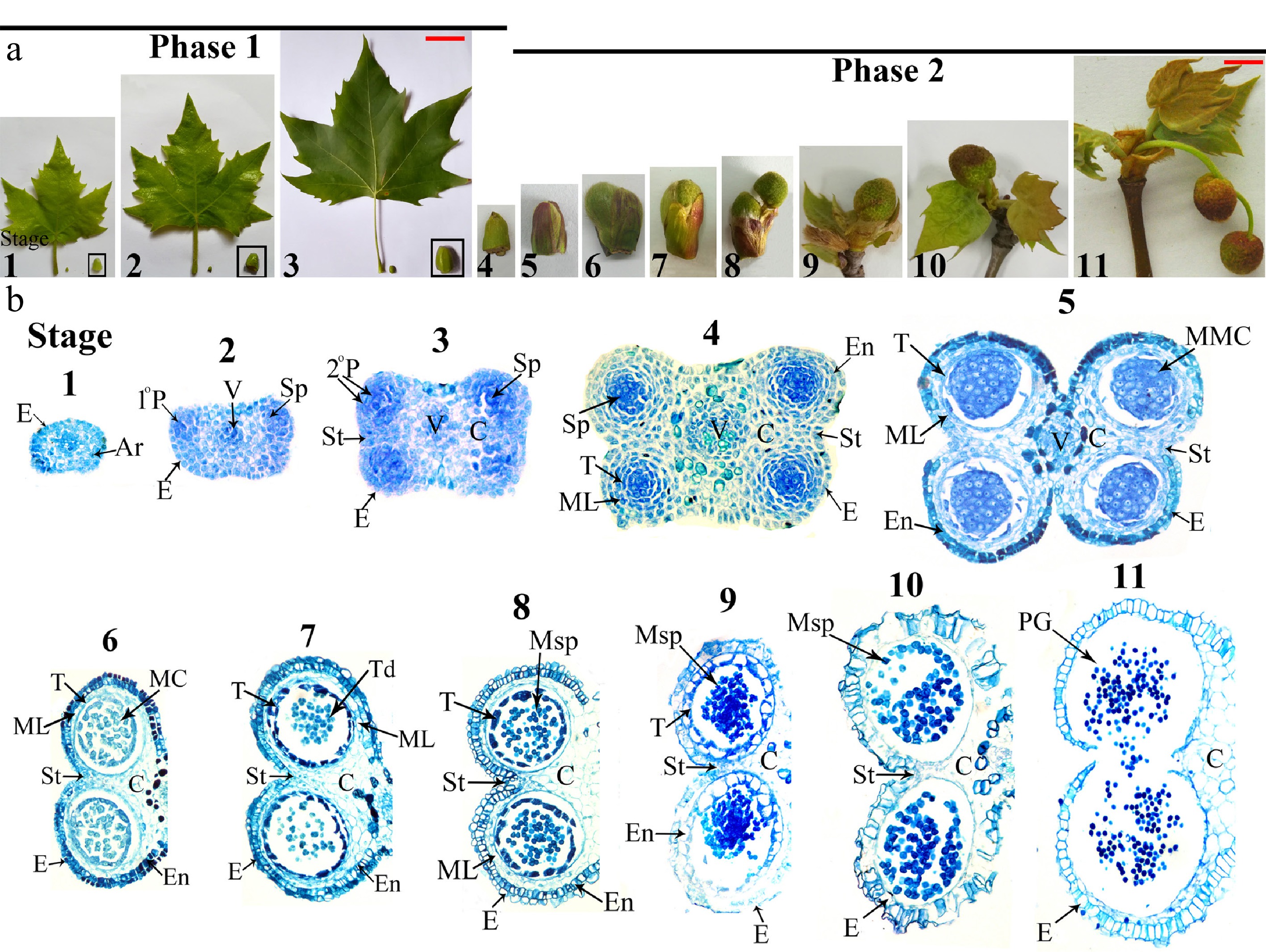

Although Platanus pollen significantly impacts human health through allergenic effects, the cytogenetic basis of its development remains poorly characterized. To investigate the mechanisms underlying pollen sterility in the polyploid 'HP' line, we first established a comprehensive staging system for stamen development in London plane tree. Through histological analysis of anther transverse sections, we established an 11-stage developmental timeline for London plane tree stamen, spanning from stamen primordia emergence to anther dehiscence (Fig. 3a). This staging system, divided into Phase I (Stages 1−4) and Phase II (Stages 5−11), enabled systematic characterization of cellular changes and served as a framework for investigating pollen sterility in the polyploid 'HP' line. The developmental progression correlated with specific morphological markers, including flower bud architecture (Fig. 3a), anther histology (Fig. 3b), and capitulum development (Table 1). Phase I encompassed early tissue differentiation, while Phase II included microsporogenesis and pollen maturation.

Figure 3.

Male flower and anther development in wild-type London Plane tree. (a) Male flower development progression from male flower bud formation to opening (shown with concomitant leaf morphology). Scale bars: 7 cm (Stages 1−3), 1 cm (Stages 4−11). (b) Bright-field micrographs of anther transverse sections throughout developmental Stages 1−11. Ar, archesporial cells; C, connective; E, epidermis; En, endothecium; MC, meiotic cell; ML, middle layer; MMC, microspore mother cells; Msp, microspores; 1°P, primary parietal layer; 2°P, secondary parietal cell layers; PG, pollen grain; Sp, sporogenous cells; St, stomium; T, tapetum; Td, tetrads; V, vascular bundle. Microscopy magnification factors for Stages 1−4, 5−7, 8−10, and 11 were × 400, × 200, × 100, and × 70, respectively.

Table 1. Major events during anther development of London plane tree.

Anther stage Time Characteristic of male flower bud Capitulum diameter (cm) Major events and morphological markers of anthers 1 Early July Capitulum primordia formed. 0.12 Oval stamen primordium, archesporial cells arise in four corners. 2 Middle of June Young leaves grown rapidly 0.15 Four regions of mitotic activity; 1° parietal, sporogenous cell and vascular region initiated. 3 Early July Adult leaves formed 0.2 Vigorous mitotic activity in four corners; two bilaterally symmetrical pollen sacs began to establishing. 4 December Leaves start shedding, flower bud enter dormancy. 0.35 Four clearly locules established; all anther cell types present. 5 End of February Outer bud-bract cracking. 0.5 Pollen sacs distinct; microspore mother cells with prominent, centrally located nuclei. 6 Beginning of March Inner bud-bract stared cracking. 0.65−0.7 Meiosis begins; middle layer be crushed and degenerate. 7 Early March Inner bud-bract cracked. 0.65−0.7 Meiosis complete; microspores in tetrad; tapetum become large and multinucleate. 8 Middle of March Capitate head out form subpetiolar bud. 0.75 Microspores released; remnants of middle layer present; secondary thickening in outer wall layers. 9 Middle to end of March Young leaves head out, outer bud-bract detachment. 0.9 Tapetum degeneration initiated; expansion of endothecial layer; microspore become vacuolated with an increase size. 10 End of March Young leaves head out. 1.05−1.1 Septum cell degeneration intiated; stomium differentiation begins; endothecium layer shrink, pollen binucleate. 11 Early April Young leaves fully expanded, capitate turn red. 1.3−1.4 Anthers dehisced along stomium; mature pollen grains released. The male flower differentiation in P. × acerifolia initiates in May and progresses through April of the subsequent year. The period from May to February encompassed Phase I (Stages 1−4) of anther development, corresponding to the vegetative growth phase that culminates in dormancy. During this phase, all major anther tissues became fully differentiated. Specifically, Phase I comprises the early differentiation of various tissues, including the epidermis, endothecium, vascular bundle, connective, stomium and tapetum (Stages 1–4, Fig. 3b). The transitional period from late February through April marks dormancy release and leaf bud break (Fig. 3a), coinciding with Phase II of anther development (Stages 5−11). During this critical phase, two key developmental processes were completed, as microsporogenesis and gametogenesis, as well as anther maturation and dehiscence (Stages 5–11, Fig. 3b).

Comparative analysis of meiotic progression and microsporogenesis in hexaploid and dodecaploid P. × acerifolia

-

In other plant species, pollen sterility has generally been attributed to premature breakdown or persistence of the tapetum[27−29]. Therefore, we used histological, cytological, and chromosomal methods to explore the structural characteristics of the anther, aiming to determine when and how the pollen abortion occurs during anther development. The results revealed no structural abnormalities in the development and degradation of the observed anther-specific tissues, including the epidermis, endothecium, tapetum, MMCs, connective tissues, stomium, and vasculature (Supplementary Fig. S3). However, the 'HP' line appeared to exhibit aberrant meiotic events during sporogenesis from sporocytes.

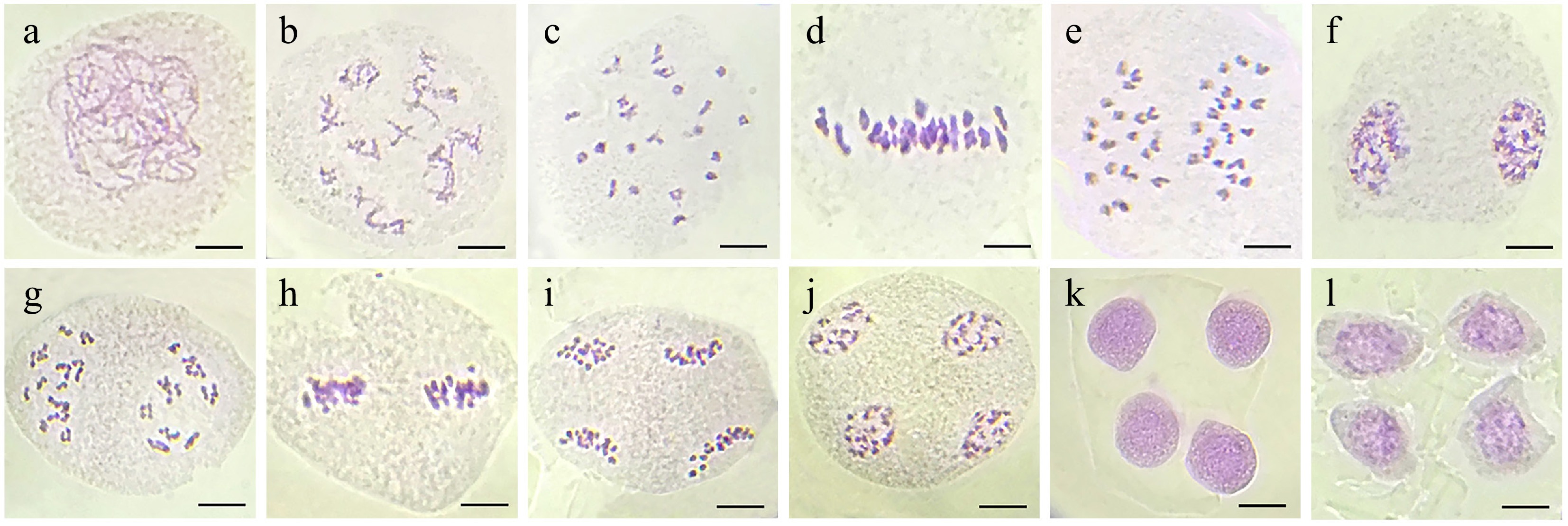

In wild P. × acerifolia, microsporogenesis involves one meiotic division followed by a mitotic division in pollen mother cells, ultimately producing four male gametes. The earliest observed stage (Fig. 4a) was leptotene, showing faint linear chromosome axes. During pachytene, homologous chromosomes synapsed and underwent recombination (Fig. 4b), later condensing into V-, O-, X-, and 8-shaped bivalents at diakinesis (Fig. 4c). At metaphase I, bivalents aligned equatorially (Fig. 4d), followed by anaphase I segregation via spindle traction (Fig. 4e). Telophase I yielded dyads with haploid chromosome sets (Fig. 4f). Meiosis II began with rod-like chromosomes in prophase II (Fig. 4g), equatorial alignment at metaphase II (Fig. 4h), and sister chromatid separation in anaphase II (Fig. 4i). Telophase II produced a tetrad (Fig. 4j, k), eventually forming four uninucleate microspores (Fig. 4l).

Figure 4.

Normal meiotic divisions in microspore mother cells of wild-type London plant tree. (a) Leptotene. (b) Diplotene with sister chromatid exchanges. (c) Diakinesis with 21 bivalents. (d) Metaphase I. (e) Anaphase I. (f) Telophase I. (g) Prophase II. (h) Metaphase II. (i) Anaphase II. (j) Telophase II. (k) Tetrad. (l) Uninucleate microspores. Bar = 10 μm.

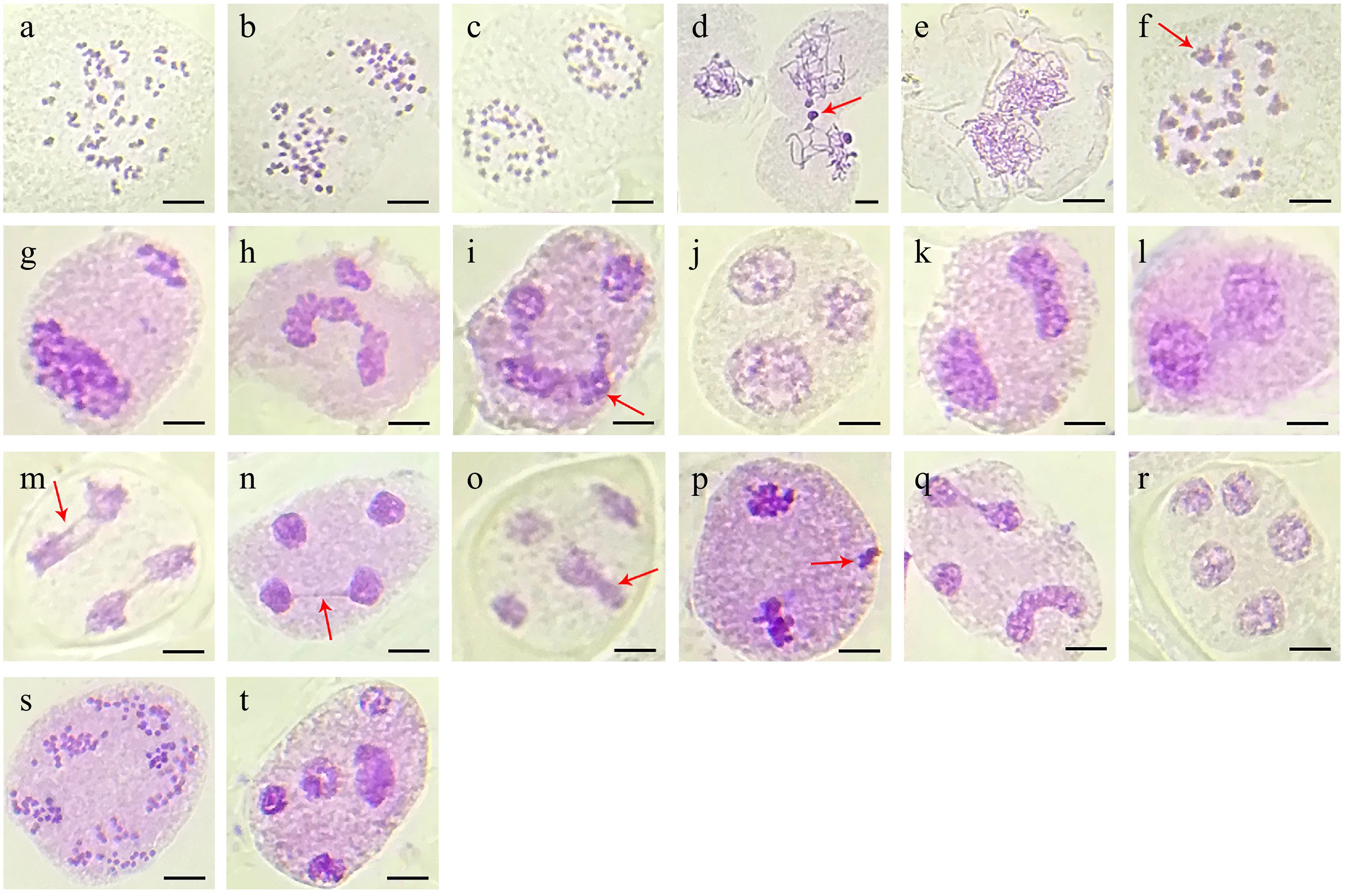

However, the polyploid 'HP' line exhibited significant meiotic abnormalities in microspore mother cells, characterized by aberrant chromosome morphology and behavior (Table 2, Fig. 5). Meiocytes of 'HP' displayed 42 bivalents at diakinesis and metaphase I (Fig. 5a). Subsequently, homologous chromosomes segregated 42:42 during anaphase I and formed two daughter cells during telophase I (Fig. 5b, c). However, multiple anomalies were observed, including chromatin transfer through broad-headed strands in 9.18% of early prophase cells (Fig. 5d), and rare instances of binucleated meiocytes at leptotene (Fig. 5e). These chromatin transfer events generated additional nuclear clusters during telophase I, which subsequently contributed to polyad formation following meiosis II (Fig. 5g, h). A subset of meiocytes (6.67%) failed to complete the first meiotic division, resulting in triad formation at anaphase II (Fig. 5i, j). Chromosome stickiness was particularly prevalent, manifesting as interbivalent chromatin adhesion in 5.31% of diakinesis cells (Fig. 5f) and progressing to form telophase II chromatin bridges in 18.32% of meiocytes (Fig. 5m, n). In severe cases, complete chromosomal aggregation occurred, creating dense chromatin masses that impaired proper segregation (Fig. 5k, l). These persistent abnormalities frequently led to the formation of restitution nuclei, producing dyads, triads, and abnormal tetrads (Fig. 5o−r). Abnormal spindle orientation and the associated patterns of chromosome migration resulted in disorganized chromosome distributions in meiocytes at anaphase II (Fig. 5s), thereby increasing genome fractionation leading to polyad formation with unequal chromosome numbers (Fig. 5t). Collectively, these meiotic irregularities resulted in abnormal microsporogenesis in 72.27% of observed cases (Table 2), demonstrating the substantial impact of polyploidy on meiotic fidelity in the 'HP' line.

Table 2. Meiotic abnormalities in tetraploid 'HP' of London plane tree.

Phases Total number of cells Abnormalities Number of cells Diakinesis 207 65 (31.40%) Chromosome transfer 19 Unorganized and pycnotic chromatin 35 Interbivalent connections 11 Metaphase I 51 4 (7.84%) Laggard chromosomes 4 Anaphase I 105 24 (22.85%) Multivalent 9 Asymmetric chromosome separation 7 Telophase I 156 19 (12.18%) Extra-nuclei 7 Asymmetric cell division 12 Prophase II 63 5 (7.94%) Asynchronous nucleus 5 Metaphase II 89 17 (19.10%) Asynchronous nucleus 4 Extra-nuclei 13 Anaphase II 191 122 (63.87%) Extra-nuclei 16 Laggards 20 Stickiness 35 Irregular spindle activity 51 Telophase II 238 172 (72.27%) Abnormal tetrad 64 Triad 61 Dyad 16 Bridges 20 Polyad 11

Figure 5.

Meiotic behavior observed in the polyploid 'HP' line of London plane tree. (a) Diakinesis with 42 bivalents. (b) Anaphase I with 42:42 chromosomes. (c) Telophase I with two daughter cells. (d) Early prophase with chromatin transfer (arrow). (e) Proximate pollen mother cell with double chromosome complement. (f) Anaphase I with interbivalent stickiness (arrow). (g), (h) Unbalanced chromosome segregation leading to additional nuclear clusters in telophase I. (i), (j) Anaphase II with severe chromosome stickiness in one daughter cell (arrow) impairing chromosome segregation leading to triad formation. (k), (l) Both daughter cells showing chromosome stickiness and forming dyads. (m), (n) Anaphase II and telophase II with chromosome stickiness in micronuclei through chromosome bridges (arrow). (o) Telophase II with irregular microspore (arrow). (p) Telophase I with one extra nuclear chromosome cluster (arrow). (q), (r) One extra nucleus and abnormal chromosome segregation formed into polyad. (s), (t) Chromosome segregation with abnormal spindle orientation leading to polyad formation with unequal microspores.

-

In this study, we found that the dodecaploid P. × acerifolia 'HP' exhibits significantly reduced pollen viability and decreased seed germination rates. Anther development, which begins with stamen primordia formation and culminates in pollen grain, involves a precisely coordinated series of developmental events including tissue specification, morphogenesis, programmed cell degradation, meiosis, and mitosis[23,27−29]. Through comparative histological analysis of sterile 'HP' anthers vs fertile wild-type anthers, we found that 'HP' maintains normal tissue architecture throughout stamen development. All anther-specific tissues—including the epidermis, endothecium, tapetum, connective tissues, stomium, and vasculature—showed no structural abnormalities during developmental or degradation processes (Supplementary Fig. S3). However, cytological examination revealed irregular chromosome behavior during meiosis in 'HP', consistent with previous reports that autopolyploids frequently exhibit chromosomal missegregation leading to fertility reduction[30]. These meiotic defects likely underlie the observed pollen developmental abnormalities.

Meiosis is a complex process with a single round of DNA replication and two successive nuclear divisions. Thus, synapsis, recombination and segregation of homologous chromosomes occurs during meiosis I, and the separation of sister chromatids occurs within meiosis II, with the subsequent development of four haploid gametes (Fig. 5)[31]. In our study, chromatin stickiness gave rise to chromatin bridges in anaphase and telophase, and severe stickiness affected the segregation of chromosomes, either wholly or partially. The chromatin transfer and pycnotic chromatin traits were mostly detected during the early meiotic prophase, and this is in agreement with earlier findings in Brassica rapa[30], rice[32], and Pinellia ternata[23]. Neo-synthetic autopolyploids display markedly compromised fertility relative to their natural counterparts, primarily attributable to the prevalent formation of meiotic multivalent complexes during metaphase I[33]. These aberrant chromosomal configurations originate from concurrent homologous pairing, synaptonemal complex assembly, and crossover establishment between multiple homologous partners, resulting in persistent chiasma-mediated linkages. Such sustained multivalent associations frequently induce erroneous chromosome disjunction during anaphase I, consequently generating aneuploid gametes and severely compromising reproductive fitness[30,34−36].

Beyond pollen sterility, the polyploid Platanus 'HP' exhibits comprehensive reproductive impairments, particularly manifested as significantly reduced inflorescence formation and fruit set rates (Fig. 1b, c). Previous studies have indicated that ploidy elevation leads to increased transcript isoform diversity, accompanied by enhanced frequencies of alternative splicing events, transposable element activation, and epigenetic modifications[2,37,38]. The observed reproductive deficiencies in dodecaploid 'HP' appear fundamentally linked to whole-genome duplication (WGD)-induced dysregulation of floral development-related genes[2], particularly the florigen components FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT)/FD, the floral repressor TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1), and the MADS-box transcription factors FRUITFULL (FUL) and SEPALLATA (SEP)[39−41].

This study demonstrates that the frequent chromosome missegregation and persistent chromatin adhesions seem to be responsible for the meiotic defects in the dodecaploid Platanus 'HP' line. Notably, under open pollination conditions with adjacent to hexaploid 'WT' trees, 'HP' showed severely compromised reproductive capacity – exhibiting only 6.85% seed germination competence. These findings indicate that the meiotic defects causing pollen sterility similarly disrupt female gametophyte development, resulting in defective embryogenesis and reduced germination success. From an applied perspective, while Platanus pollen and seed trichomes represent clinically significant aeroallergens, our results establish that polyploidization induces two valuable phenotypic traits: (1) significantly impaired pollen viability (reduction of 88.5% vs hexaploid); and (2) significantly diminished allergen production (91.8% reduction in inflorescence production and more than 95% decrease in cone set frequency). These findings position polyploid breeding as a promising strategy for developing low-allergen urban Platanus cultivars without compromising ornamental value.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32402607), the Hubei province natural science foundation grant (2024AFB915), and the research fund of Hubei provincial department of education (Q20232702). We thank Dr Alex McCormac (Mambo-Tox Ltd., Southampton, UK) for help with editing of the manuscript and all colleagues in our laboratory for technical assistance.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception: Bao M; study design: Bao Z, Long H, Li B, Shao C, Zhang J, Bao M; experiments: Bao Z. manuscript writing: Bao Z, Long H; manuscript editing and project advice: Bao M, Li B, Shao C, Zhang J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Winter-persistent cones in WT and 'HP' lines of P. × acerifolia.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Seed germination assays. (a) Representative images of WT and 'HP' seedlings at 15 days after sowing (DAS); (b) Quantification of germination rates in WT and 'HP' at 30 DAS. Data represent mean ± SD; n = 3, more than 300 seeds were analyzed; **** p < 0.0001 by Student's t-test.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Paraffin section images of individual anther locule cross-sections of the polyploid ‘HP’ line of London plane tree. The images (a)−(h) correspond to anther developmental Stages 4−11, respectively. MC, meiotic cell; MMC, microspore mother cells; Msp, microspores; PG, pollen grain; Sp, sporogenous cells; T, tapetum; Td, tetrads. Scar bars = 100 μm.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Bao Z, Long H, Li B, Shao C, Zhang J, et al. 2025. Anther development and pollen fertility in a polyploid cultivar of Platanus × acerifolia Willd. 'Huanong Panlong'. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e038 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0036

Anther development and pollen fertility in a polyploid cultivar of Platanus × acerifolia Willd. 'Huanong Panlong'

- Received: 26 June 2025

- Revised: 30 July 2025

- Accepted: 07 August 2025

- Published online: 10 October 2025

Abstract: Platanus, a key species in urban landscaping, is a classic allopolyploid with three distinct subgenomes. Polyploidization often induces meiotic irregularities, offering promising opportunities for breeding improved ornamental cultivars with suppressed flowering and fruiting. Here, we investigated the morphological and cytological characteristics of synthetic polyploid P. × acerifolia 'Huanong Panlong' (HP, 2n = 12x = 84) induced via colchicine treatment, and demonstrated that its higher ploidy level correlates with significantly reduced pollen viability (9.54%). Microstructural analysis revealed that no structural abnormalities were detected in the sporophytic anther tissues of 'HP'. However, cytological analysis identified a series of meiotic abnormalities during the microsporogenesis, including chromatin stickiness, multivalent formation, persistent chromatin bridges, and disordered chromosome segregation, resulting in dyad, triad, and polyad formation. Notably, approximately 72.27% of meiocytes exhibited abnormal tetrad formation. These meiotic irregularities likely account for both the observed pollen sterility and the consequent reductions in fruit set (3-6 cones an adult tree) and seed germination rate (6.85%). From an applied perspective, the observed reproductive deficiencies hold particular significance for urban horticulture, as both P. × acerifolia pollen grains and achene fibers are potent respiratory aeroallergens.

-

Key words:

- Platanus × acerifolia /

- Pollen sterility /

- Anther development /

- Meiotic abnormalities /

- Polyploidy