-

The sessile nature of plants makes them vulnerable to intricate and fluctuating environments, and susceptible to pathogen infection and herbivore attack, which result in adverse impacts on the growth, development, and yield of plants. To deal with these complex abiotic and biotic stresses, plants have evolved plentiful defense mechanisms, including the formation of specialized tissue structures (such as trichomes and thorns) as physical barriers, and the production of specific metabolites (such as toxins and terpenoids) as chemical protections[1,2].

Phytohormones are natural products of plants that play essential roles in sensing changeable environmental cues and initiating signaling cascades to respond to various stresses[3]. SA is a central member of phytohormones that is essential for plant immunity, growth, and development[4]. SA can not only regulate the response to biotic stresses to enhance the resistance of plants to the invasion of pathogens (e.g. virus, bacteria, and fungi) and attacks of arthropods and herbivores but also alleviate diversified abiotic stresses (such as drought, ultraviolet-radiation, and thermo-tolerance) to help plants adapt to adverse environments[5]. Additionally, it also functions as a versatile signal molecule to regulate multiple biological processes such as seed germination, vegetative growth, photosynthesis, flowering, and senescence[6,7]. Usually, stimulus caused by aforementioned biotic factors will trigger the sophisticated immune responses in plants, including pathogen (or microbe)-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI), respectively[8]. The defense phytohormone SA is of great importance for PTI and ETI against biotrophic, and hemibiotrophic pathogens[9,10], and it is also involved in strengthening resistance in the infected tissues and further inducing the systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in the uninfected parts of plants[9,11]. The role of SA in plant immunity against biotic stress is irrefutably established, and the underlying molecular basis still requires further in-depth investigation[12].

Attributed to its significant biological function in plant growth and defenses, the biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling pathways of SA are systematically managed at multidimensional levels to maintain the regular growth and enhance the resistance of plants to manifold biotic factors[13]. In this context, we will focus on these recent advancements in the regulation of SA biosynthesis and SA-mediated signaling in response to biotic stress.

-

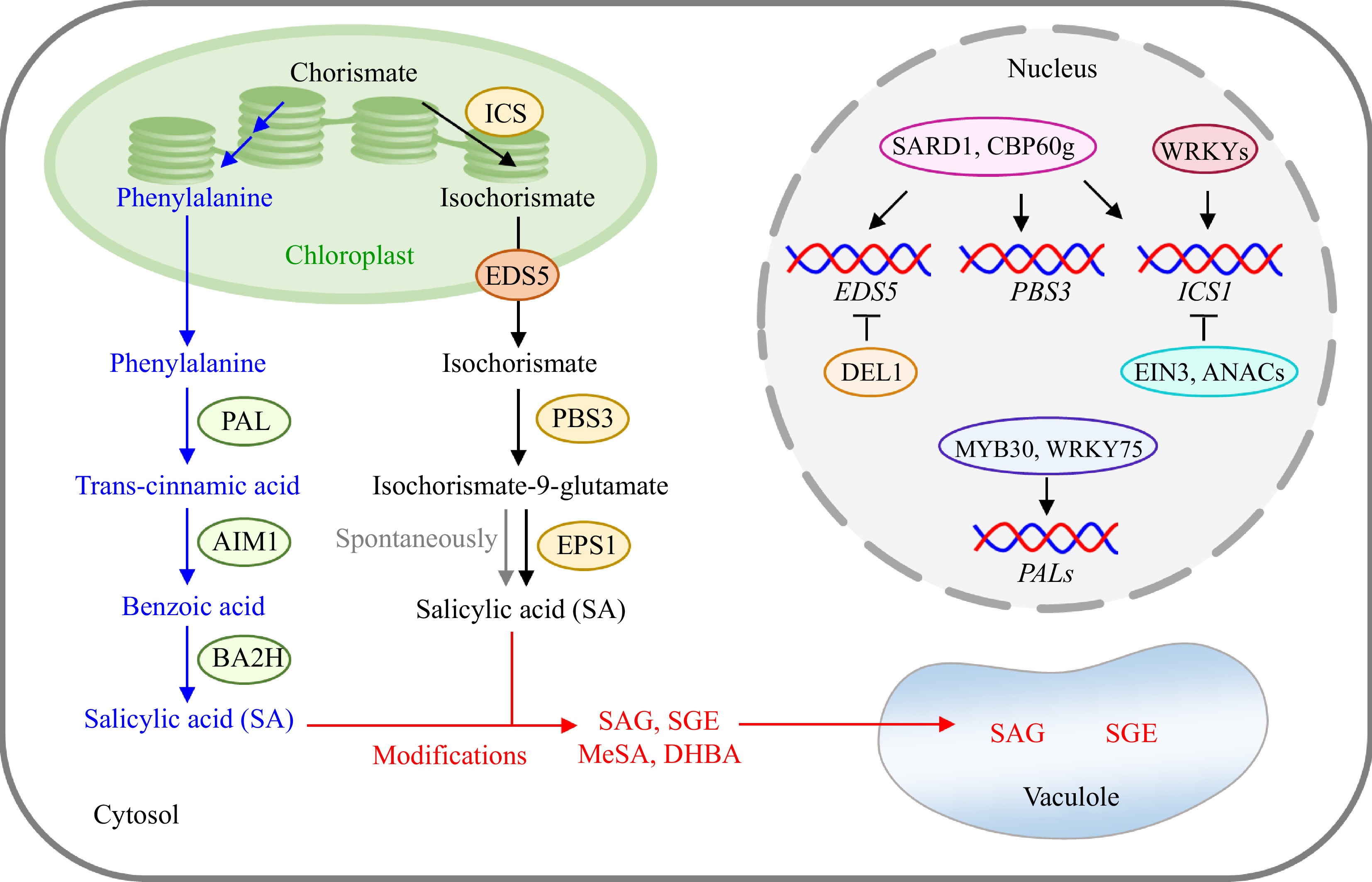

SA, also known as 2‐hydroxybenzoic acid, is a type of phenolic compound and a natural secondary metabolite produced in bacteria, fungi, and plants[14]. The phylogenetic analysis performed by a recent study demonstrated the widespread existence of SA biosynthesis in the green lineages and the significance of SA in high-irradiance acclimation after plant terrestrialization[15]. The route for SA biosynthesis has been investigated for several decades, but its precise biosynthetic pathway in different plant species has not yet been fully understood. Currently, it is generally recognized that plants utilize chorismate as the common precursor to synthesize SA through two widely accepted pathways: the isochorismate (IC) pathway and phenylalanine ammonia‐lyase (PAL) pathway[16] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis, metabolism, and regulation of SA in plants. Plants employ the precursor chorismate for SA production through two biosynthetic pathways mediated by ICS and PAL, respectively. On the one hand, SA is generally metabolized or conjugated to form other compounds (such as SAG, SGE, and MeSA) under various types of modifications to maintain SA at the basal level in vivo. SAG and SGE can be further stored in the vacuole. On the other hand, the biosynthesis of SA is also precisely regulated by many transcription factors. For instance, SARD1 and CBP60g are key regulators of ICS1, PBS3, and EDS5. The expression of ICS1 is also enhanced by some WRKYs and inhibited by EIN3 and ANACs. DEL1 is a well-documented repressor of EDS5. Additionally, PALs can be positively regulated by MYB30 in rice and WRKY75 in Tulip. PAL, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; AIM1, abnormal inflorescence meristem 1; BA2H, benzoic acid-2-hydroxylase; ICS, isochorismate synthase; EDS5, Ehanced Disease Susceptibility 5; PBS3, AvrPphB Susceptible 3; EPS1, Ehanced Pseudomonas Susceptibility 1; SAG, SA glucoside; SGE, SA glucose ester; MeSA, methyl salicylate; DHBA, dihydroxybenzoic acid; SARD1, SAR-deficient 1; CBP60g, Calmodulin binding protein 60-like g; EIN3, ethylene insensitive 3; DEL1, atypical DP-E2F-like 1.

Isochorismate pathway

-

Genetic analyses revealed that SA is principally synthesized via the isochorismate pathway in plants[17,18]. According to the researchers' efforts in the isochorismate pathway of SA biosynthesis, it is well elucidated that the synthesis of SA occurs in both the chloroplast and cytosol[19] (Fig. 1). In chloroplasts, the primary precursor chorismate is converted into isochorismate by the chloroplast-localized isochorismate synthase (ICS). Isochorismate is further transported to the cytosol with the assistance of Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 5 (EDS5), a transporter localized in the chloroplast envelope and belonging to the multidrug and toxin extrusion family[20−22]. The cytosolic isochorismate is subsequently conjugated with glutamate to form isochorismate-9-glutamate under the catalysis of an amidotransferase known as AvrPphB Susceptible 3 (PBS3), whose enzymatic activity is inhibited by SA through a feedback regulatory loop[23]. Isochorismate-9-glutamate can be further decomposed into SA either spontaneously or through the action of an acyltransferase called Enhanced Pseudomonas Susceptibility 1

(EPS1)[21,23]. It is worth noting that the spontaneous degradation of isochorismate-9-glutamate can effectively produce SA in the absence of EPS1[21].In the isochorismate pathway, the conversion of chorismate to isochorismate is catalyzed by a rate-limiting enzyme remarked as ICS[24]. Plant ICS enzymes are universally encoded by one or two ICS genes. For example, rice has one ICS gene, while Arabidopsis thaliana (hereinafter referred to as Arabidopsis) owns two ICS genes (AtICS1 and AtICS2)[25]. In Arabidopsis, pathogen treatment could dramatically induce the accumulation of SA and AtICS1 transcripts, while the abundance of AtICS2 was largely undetectable. Importantly, SA content in Atics1 mutant only accounted for 5%−10% compared to the SA level in wild-type plants treated with pathogens, indicating that AtICS1 mediates more than 90% of SA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis[26]. Although AtICS2 is capable of breaking down chorismate, its contribution to SA biosynthesis is limited, and the Atics1 isc2 mutant could synthesize a slight amount of SA[27]. Barley has a single ICS gene, and its knock-out ics mutant accumulated normal basal SA, suggesting the basal SA of barley does not originate from the isochorismate pathway[28]. These studies reveal that SA biosynthesis is not restricted to the isochorismate pathway in plants.

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase pathway

-

Besides the isochorismate pathway, plants also employ a second biosynthetic pathway for SA mediated by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), which serves as the rate-determining enzyme in this pathway encoded by multiple copies of the PAL genes[24]. Briefly, phenylalanine is first synthesized in the chloroplast from chorismate, and then the cytosolic enzyme PAL uses phenylalanine as a substrate to produce trans-cinnamic acid[29]. Benzoic acid is further made from trans-cinnamic acid by abnormal inflorescence meristem 1 (AIM1) and subsequently metabolized to SA through benzoic acid-2-hydroxylase (BA2H)[30−32] (Fig. 1). AIM1, a hydroxyacyl-CoA hydrolyase, is responsible for β-oxidation process using multiple substances as substrates besides trans-cinnamic acid, and its role in SA biosynthesis is well-established and valuable[33]. As for BA2H, it was indeed involved in SA formation from benzoic acid in tobacco, and SA content was highly correlated with the activity of BA2H under salt stress in rice and heat stress in pea[32,34,35]. However, direct experimental evidence for the role of BA2H in SA biosynthesis is lacking, as there are few further related studies.

Although the isochorismate pathway and PAL pathway for SA biosynthesis have been documented, the contribution of these two pathways in various plants is significantly different and still controversial[24]. For instance, SA is predominantly synthesized via the PAL pathway in virus-infected tobacco, whereas SA biosynthesis induced by pathogens is almost equally produced by isochorismate and PAL pathways in soybean[36,37]. Previous studies considered that approximately 90% of SA in Arabidopsis is made from isochorismate pathway, and the quadruple mutant of Arabidopsis PALs with developmental defects certainly displayed a reduction of SA level[26,38]. Interestingly, a recent report showed that feeding Arabidopsis plants with isotopically labeled phenylalanine produces 4‐hydroxybenzoic acid rather than SA, whereas feeding isotopically labeled benzoic acid results in SA production, indicating that SA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis is not related to phenylalanine, but depends on benzoic acid[39]. It is still largely unknown whether the benzoic acid-dependent SA biosynthesis relies on the PAL pathway, and the identification of key enzymes involved in this pathway are beneficial to uncover the route of SA biosynthesis independent of isochorismate pathway in Arabidopsis[40]. Additionally, it is also of great value to address the SA biosynthetic pathway in plants whose SA biosynthesis routes are not well-established in the future.

Regulation of salicylic acid homeostasis

-

Generally, basal SA levels are maintained at a relatively low level during the process of plant growth and development to avoid hyperactivated signaling. Upon perceiving internal and external stimuli, such as pathogen infection, SA content rapidly increases to initiate immune responses against relevant biotic factors[41]. Therefore, the intracellular SA level is of great importance for both plant growth and immunity, and it is precisely regulated at multilayered levels.

In plants, free SA can also be transformed into inactive forms under various modifications, such as methylation, glycosylation, and hydroxylation[19] (Fig. 1). In Arabidopsis, SA is usually glycosylated by UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGT74F1, UGT76B1, and UGT74F2) to form SA glucoside (SAG) and SA glucose ester (SGE), which can be further stored in vacuoles[42,43]. The benzoic acid/SA carboxyl methyltransferase 1 (BSMT1) methylates SA to produce methyl salicylate (MeSA), which is critical for SAR and can be converted back to SA by methyl esterase 9 (MES9)[44,45]. SA also undergoes hydroxylation to form dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA) and suffers from many other modifications, such as sulfonation, to collectively stabilize the SA level within the optimal range[24].

Besides being modulated through chemical modifications, the SA level is broadly adjusted by regulating its biosynthesis (Fig. 1). Studies on Arabidopsis demonstrated that the invasion of pathogens observably induced the transcription of ICS1, along with significant SA accumulation[26], indicating that ICS1 is the pivotal enzyme for SA biosynthesis. Transcription factors regulating the expression of ICS1, as well as EDS5 and PBS3, have been isolated and characterized. For instance, Calmodulin binding protein 60-like g (CBP60g) and SAR-deficient 1 (SARD1) can directly target the promoters of abovementioned three genes and cooperatively activate their expression during pathogen-infection[46]. The WRKY transcription factors, such as Arabidopsis WRKY28 and Tulip WRKY75, are also reported to positively regulate ICS1 expression[47,48]. Furthermore, ethylene insensitive 3 (EIN3) and ANAC109 could inhibit the expression of ICS1, and atypical DP-E2F-like 1 (DEL1) can transcriptionally repress the expression of EDS5[24]. However, the regulation of PAL-mediated SA biosynthetic pathway remains currently unbeknown, except for one MYB transcription factor from rice (OsMYB30) that positively mediates the expression of OsPAL6/8[49], and the Tulip WRKY75 that activates PAL1 expression[47]. The verification of critical regulatory proteins of ICS- and PAL-mediated SA biosynthetic pathways is one of the key focuses for future work to better understand the biological function of SA.

Salicylic acid perception and signaling

-

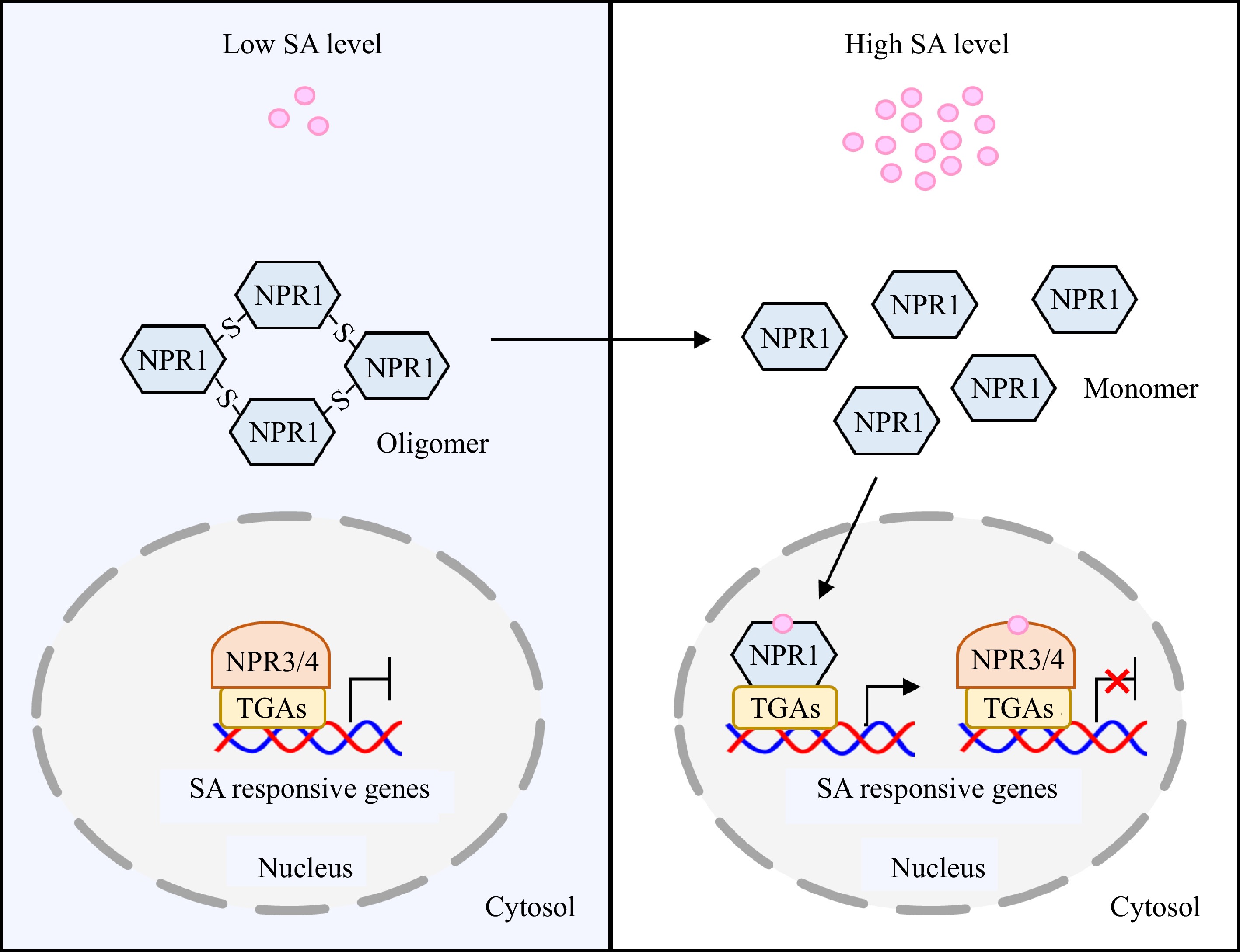

As a crucial signal molecule participating in multitudinous biological and stress-responsive processes, relevant receptors or SA-binding proteins are necessary to perceive SA for further signal transduction. The nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related protein 1 (NPR1) is the predominant SA-receptor that localizes to the cytosol in its oligomeric form and to the nucleus in its monomeric form[50]. In the cytosol, SA induces the formation of NPR1 condensates, which contain many stress-responsive proteins and recruit the Cullin 3 E3 ligase complex to control the homeostasis of these stress proteins[51]. The cytosolic NPR1 is also connected with jasmonic acid (JA)-mediated defense response by interacting with the jasmonate zim-domain proteins (JAZs), the repressor of JA-signaling[52]. Interestingly, SA accumulation can induce the redox state transition and then trigger the conformational change of NPR1 to promote its translocation into the nucleus, which is essential for the activation of SA-responsive genes[53]. It is well-known that NPR1 is a transcriptional activator lacking the DNA-binding domain so its regulatory functions in the nucleus are realized through 'TGACG' motif-binding transcription factors (TGAs), which can target the promoter of SA responsive genes (e.g. pathogenesis-related (PR) genes) and promote their expression[54,55]. There is no doubt that NPR1 is pivotal in SA signaling, as npr1 mutants are insensitive to SA and display significant alterations in SA-induced responses[56]. Nevertheless, a partial SA-induced response is still observed in npr1 mutants, suggesting the involvement of other key regulatory proteins in SA-induced responses[57].

Besides NPR1, Arabidopsis has five NPR1-related paralogs that also play key roles in SA-mediated signaling, namely NPR2, NPR3, NPR4, and BLADE ONPETIOLE 1/2 (BOP1/2). NPRs bind SA tightly, while BOP1/2 has low affinity with SA. Especially, NPR2 can partially complement the npr1 mutant, indicating that it is a SA receptor positively regulating SA signaling as NPR1[58]. In contrast, NPR3 and NPR4 are SA receptors that function as transcriptional repressors of TGAs and negatively control SA signaling[59,60]. BOP1/2 can affect methyl jasmonate (MeJA)-triggered resistance, and response to SA only in the absence of NPR3/4[58,61]. It is considered that NPR3/4 regulates the stability of NPR1, and they exert opposite effects on SA-mediated immune responses compared to NPR1[60,62]. The biological function of NPRs dependent on the intracellular SA level in vivo. At a relatively low intracellular SA level, SA-responsive genes are powerfully inhibited by a complex consisting of NPR3/4 and TGAs, and most NPR1 proteins are in the cytosol in the form of oligomers. Conversely, at high intracellular SA levels, NPR3/4 are deactivated upon binding to SA, so that the repression effect of NPR3/4-TGAs on SA-responsive genes is alleviated, and NPR1-TGAs intensively activate the expression of SA-responsive genes[15]. The action of NPR1 and NPR3/4 effectively fine-tunes the SA-induced responses against various stresses (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

NPRs-mediated SA signaling pathway in plants. At low intracellular SA level, NPR1 presents in the cytosol in its oligomeric form, while NPR3/4 interact with TGA transcription factors and inhibit the expression of SA-responsive genes. When intracellular SA level is elevated, the redox state transition induced by SA accumulation can trigger the conformational change of NPR1 from oligomer to monomer. The monomeric form of NPR1 enters into nucleus, and then interacts with TGAs to activate expression of SA-responsive genes. Meanwhile, SA binds to NPR3/4 and represses their activities, thereby alleviating the inhibitory effect of NPR3/4-TGAs on SA-responsive genes. NPR, nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related protein.

To deeply explore the SA signaling pathway, researchers employed high throughput screens to isolate many SA-binding proteins (SABPs), whose roles in SA signaling await to be addressed[63]. These SABPs encompass a wide range of enzymes and proteins, including catalase, MeSA esterase, carbonic anhydrase, glutathione S-transferase, thioredoxin, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and so on[57]. They are involved in different biological and physical pathways, indicating the versatility of SA. Taking the SABP1, SABP2, and SABP3 as examples, SABP1 is a soluble cytosolic catalase that can be inactivated by SA and first characterized in tobacco. SABP2 is defined as the MeSA esterase that catalyzes the conversion of MeSA to SA, and the knock-down of SABP2 impairs the resistance to tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) resulting from the reduced SA-activated PR1 expression. SABP3 is characterized as β-carbonic anhydrase, whose activity is repressed by SA, and it plays a key role in plant immunity. Notably, SABP3 can interact with NPR1 in a SA-dependent manner, indicating the crosstalk between SABP3-mediated signaling and NPR1-dependent signaling pathway[57]. These studies suggest the essential role of SABPs in SA signaling, yet the function of most SA-binding proteins remains under investigation. Therefore, it holds great significance to elucidate the role of these SA-binding proteins in SA signaling and how they interact with NPRs-mediated SA-induced responses in the future, which would provide new paradigms for the regulation of SA signaling in plants.

-

Pathogens and herbivores are the most common and harmful biotic factors that tremendously threaten plant fitness, often resulting in severe diseases and crop failure. Phytohormones are essential for inducing the complicated defenses against these detrimental attackers to ensure the survival of plants[64]. Among these distinct phytohormone-dependent defense mechanisms, SA-mediated defense responses against biotic stressors are widely and well-studied. It can function either individually or in cooperation with other phytohormones, such as JA and ethylene (ET), to cope with various types of biotic factors[65]. For example, JA and ET, as predominant and recognized defensive phytohormones, contribute to the defense against necrotrophs and can interplay synergistically or antagonistically with SA-mediated immune responses through mutual influences on their biosynthesis or downstream signaling pathways[66,67].

Besides JA and ET, other phytohormones are also believed to play crucial roles in plant resistance against biotic stressors and potentially communicate with SA signaling[65]. For instance, the induction of stomatal closure by abscisic acid (ABA), coupled with the accumulation of callose and production of secondary metabolites, effectively minimizes the infiltration of pathogenic bacteria and insects[68,69]. The study on ABA receptor pyrabactin resistance 1 (PYR1) showed that it can negatively regulate the SA pathway by inhibiting the expression of SA-responsive defense genes[70]. Auxin, one of the growth-regulating phytohormones, is also of great significance in the interactions between plants and pathogens[71]. Additionally, pathogen-induced SA can disturb auxin levels, and alter the expression of auxin sensitivity-related genes, thereby enhancing the resistance against pathogens[14,72]. Brassinosteroid (BR) contributes to plant resistance against biotic factors like Fusarium culmorum, TMV, and Magnaporthe grisea, and its combined application of pyraclostrobin largely improves the disease resistance of Arabidopsis plants to Botrytis cinerea and Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis[73,74]. Intriguingly, the cooperative up-regulation of ICS1 by Brassinazole-Resistant 1 (BZR1) and CYP85A1 by TGA1/4 in Arabidopsis boosted endogenous BR and SA levels, and the interaction between TGAs and BZR1 further triggered SA-mediated immunity by elevating PR5 expression, ultimately fortifying the plant resistance to pathogens[75]. Cytokinin (CK) has been reported to exhibit both positive and negative impacts on plant resistance to specific pathogens, with recent studies showing cell-specific effects in responses to Phytophthora infestans and a reduction in tomato disease symptoms caused by necrotrophic and biotrophic fungi, which are dependent on SA and ethylene mechanisms rather than JA[76,77]. Gibberellin (GA) is also reported to affect signaling pathways during pathogens invasion, and DELLA, the repressor of GA signaling, regulates plant immunity by balancing the signaling of SA and JA[78,79]. Strigolactones (SLs) have recently gained significant attention for their pivotal role in regulating various molecular and physiological adjustments in plants under biotic stresses, including their negative regulation in TMV resistance and key involvement in SA-dependent disease resistance, where SA conversely determines SLs-induced disease resistance in Arabidopsis[80−83]. These studies emphasize that defensive pathways elicited by phytohormones, especially SA, are important for plants in defending themselves against a variety of detrimental attackers, including pathogens and herbivores.

Salicylic acid-mediated defense responses against pathogens

-

Plants are susceptible to the invasion of multifarious pathogens, including virus, bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and oomycetes. These pathogens can not only deprive the nutrients of plants, but can also disrupt the normal physiological processes by producing toxins and virulence proteins that cause tissue damage, and even cell death to the plants[84]. Therefore, plants have evolved robust defense systems to combat pathogens. When pathogens attach to the plant host, they are immediately recognized by the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and activate PTI to initiate the first defensive line of plants. Most pathogens typically release effectors to inhibit PTI and activate the ETI process, which further stimulates a series of signaling cascades, such as SA biosynthesis and signaling, the SAR pathway, and the production of secondary metabolites[85].

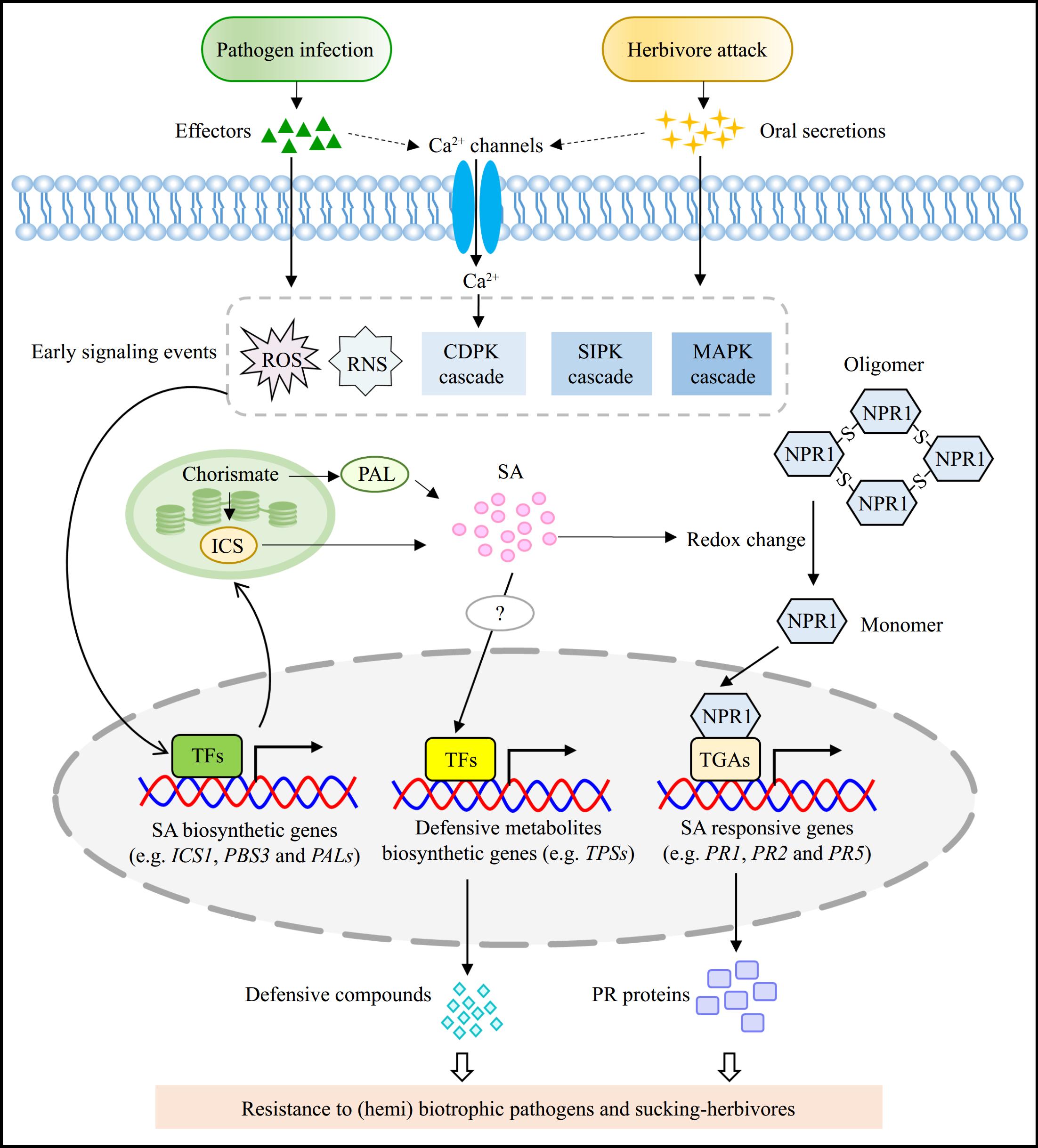

As the vital component of defensive responses, SA can promote the resistance of both local and systemic plant tissues, and regulate the process of hypersensitive response (HR) and cell death induced by pathogens[41]. SA-elicited defense responses are proposed to predominantly resist biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens, and function either individually or cooperate with other phytohormones such as JA to cope with different kinds of pathogens[86]. The connection between pathogen-infection, SA biosynthesis/signaling, and resistance of plants against pathogens has been well-established[12]. Previous studies have shown that the expression of key SA biosynthetic gene ICS1 was dramatically induced and SA level was significantly increased in pathogen-treated Arabidopsis plants, indicating that pathogen-infection can rapidly elevate SA accumulation probably through regulating the SA biosynthesis in plants[26]. Generally, the invasion of pathogens leads to some early signal reactions that function upstream of SA accumulation, such as the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades and elevation of Ca2+ level[87] (Fig. 3). These early signaling events play key roles in controlling SA biosynthesis. For instance, the elevated Ca2+ level relieves the repression of calmodulin-binding transcription activators (CAMTAs) on the critical regulators CBP60g and SARD1, which further positively regulate the expression of SA biosynthetic genes (ICS1, PBS3, and EDS5) to promote SA production[24].

Figure 3.

SA-mediated defense responses against pathogens and herbivores. When pathogens and herbivores invade plants, they usually produce effectors and oral secretions, respectively. These effectors and oral secretions generally elicit a range of early signaling events, including the burst of ROS and RNS, an increase of intracellular calcium level, and the activation of several protein kinase-mediated cascades. These early signaling events subsequently activate the TFs to promote the expression of SA biosynthetic genes, thereby enhancing SA accumulation. The elevated intracellular SA level induces the redox change that triggers the transition of NPR1 from oligomer to monomer, allowing it to enter the nucleus and interact with TGAs to stimulate the expression of SA-responsive genes (e.g. PR1, PR2, and PR5). Additionally, SA accumulation also promotes the production of defensive metabolites, probably by activating TFs that can directly target to the promoter of biosynthetic genes associated with these defensive metabolites. However, the precisely regulatory mechanism of SA-mediated production of defensive metabolites remains to be investigate. These defensive metabolites and PR proteins contribute to improve the resistance of plants to (hemi)biotrophic pathogens and sucking-herbivores. ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; CDPK, Calcium-dependent protein kinase; SIPK, SA-induced protein kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; TFs, transcription factors; PR, pathogenesis-related protein.

Notably, the accumulation of SA is the prerequisite to induce the subsequent immune response, since the resistance of plants to pathogens and the expression of genes related to plant immunity can be largely enhanced by the supplementation of exogenous SA[85,88]. Importantly, mutants deficient in SA accumulation are universally impaired in the SAR response and are more susceptible to pathogens[89]. The elevated intracellular SA level induces the accumulation of ROS and the change of redox state probably by controlling the expression of antioxidants-related genes, and then promotes the conversion of NPR1 from oligomer to monomer[7,90]. The NPR1 monomer enters into the nucleus and interacts with TGAs to enhance the expression of PR genes in both infected and uninfected parts of plants, which contributes to prevent the further spread of pathogens to uninfected tissues[54,55] (Fig. 3).

PR proteins were firstly identified in the TMV-infected tobacco and consist of at least 17 families of proteins that are indispensable for plant immune responses, such as chitinases, ribonuclease, glucanases, hydrolases, anti-microbial agents, and peroxidases[91,92]. These PR proteins appear a variety of structural, enzymatic, and receptor functions, some of which also display anti-pathogenic activities against bacteria, virus, insects, nematodes, and fungi[93]. PR1, PR2, and PR5 can specifically respond to SA, and they are commonly employed as signature proteins of SA-mediated SAR pathway[94]. PR1 is a small protein with anti-microbial activity and capable of sterols-binding, which can sequestrate sterols from pathogens to inhibit their growth[95]. The family of PR2 proteins are β-1,3-glucanases that defend against fungi through hydrolyzing their cell walls and forming oligosaccharides to induce the accumulation of other PR proteins or antifungal compounds[93]. PR5 proteins are similar to thaumatin-like proteins (TLPs), some of which are equipped with antifugal activities and can disrupt the fungal plasma membrane through osmotic rupture to resist the invasion of fungi, as well as a number of other pathogens[96]. The SA-responsive PR proteins (PR1, PR2, and PR5) are supposed to mutually function with other PR proteins, such as JA-responsive PR proteins (PR3, PR4, and PR12), to effectively handle the infection of pathogens that are not limited to (hemi)biotrophic pathogens[94]. Besides the transcriptional regulation of SA-responsive genes and the production of PR proteins, SA-mediated immune responses could also enhance the resistance to pathogens by stimulating the biosynthesis of callose and lignin to consolidate plant cell walls, and activating the production of secondary metabolites with antimicrobial function[97].

Salicylic acid-mediated defense responses against herbivores

-

Herbivores exclusively feed on plant tissues such as root, sap, and foliage, causing severe damage to the growth, development, and production of plants. Herbivores can be divided into sucking/piercing (e.g. aphids, whiteflies, thrips, and mites) and chewing insect herbivores (beetles, caterpillars, etc.) based on their distinct feeding ways[98]. During feeding, herbivores lay eggs and secret components or effectors from their oral and gut. These compounds are conceptually defined as herbivore-associated molecular patterns (HAMPs), which can be recognized by plants and generally trigger various signaling events, such as electrical signals, Ca2+ influxes, kinase cascades reactions, ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) burst, phytohormone signaling, and biosynthesis of defensive metabolites[99,100] (Fig. 3).

Plants utilize different defense strategies to fend off the attacks from sucking and chewing insect herbivores, and elicit the downstream phytohormone-regulated immune responses. Sucking herbivores usually seek out feeding spots in the phloem and trigger the defensive response mediated by SA[52]. Several studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between the attack of sucking herbivores and the biosynthesis/signaling of SA. A recent report indicated that the disruption of SA accumulation, caused by the heterologous expression of salicylate hydroxylase (NahG) in maize plants, diminishes their resistance to insect herbivores such as Spodoptera frugiperda, Spodoptera litura, and Mythimna separata[101], suggesting the crucial role of SA in defense against insect herbivores. In rice, OsPALs are significantly up-regulated during Brown planthopper feeding to promote the biosynthesis and accumulation of SA, thereby enhancing the resistance to Brown planthopper[49]. In Arabidopsis, the invasion of silverleaf whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) activates the gene expression related to SA biosynthesis (ICS1 and EDS5) and signaling (RP1, PR2, and PR5)[102]. The oral secretions (fatty acid-amino acid conjugates) of Manduca sexta can activate the SA-induced protein kinase (SIPK), an endogenous MAPK kinase that can induce several defensive responses in tobacco[103,104]. A salivary chemosensory protein (SmCSP4) secreted by S. miscanthi during feeding can induce the SA-regulated immune response to impede the feeding of aphid on wheat. SmCSP4 can interact with wheat WRKY76 to inhibit the transcriptional activation effect of WRKY76 on the SA-degradation enzyme, and thus enhance the accumulation of SA[105]. The SA pathway also promotes the generation of ROS to protect plants from insect herbivores by destroying the digestive system of pests and limiting their growth and development[90]. These studies indicate that plants can withstand the feeding of sucking herbivores by stimulating the accumulation of SA and SA-dependent defense responses (Fig. 3).

It is worth noting that plants suffering from herbivore-attacks commonly synthesize various secondary metabolites for defense, including phenolics, terpenoids, sulfur-, and nitrogen-containing compounds. These metabolites can directly dislodge and toxify herbivores, activate the defensive mechanism of plants against herbivores, and attract natural enemies of herbivores to prey on them[106]. Potato leaves damaged by the herbivore mite Tetranychus urticae release volatile organic compounds, which can entice the Neoseiulus californicus from flower to leaves to prey on Tetranychus urticae[107]. Studies from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) have shown that SlMYB75 affects the accumulation of sesquiterpenes (δ-elemene, β-caryophyllene, and α-humulene) to control the tolerance to spider mites by regulating the expression of terpene synthase genes[108]. The infestation of two-spotted spider mites results in increased expression of genes related to SA accumulation and volatile biosynthesis in tomato plants[109]. The defensive compound indole glucosinolates accumulates in Arabidopsis infected with the aphid Myzus persicae to elevate plant resistance[110]. These researchers indicate that the production of defensive secondary metabolites is an indispensable way of plant resistance to biotic stress.

Given the defensive role of secondary metabolites against a variety of biotic stresses, their biosynthesis is undoubtedly regulated by distinct factors in plants. The key transcription factors involved in mediating the biosynthesis of these defensive secondary compounds have been extensively investigated, such as WRYK, basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH), and MYB[111]. As the significant defensive phytohormone, SA certainly exerts function in regulating the biosynthesis and metabolism of secondary metabolites associated with defense responses in plants. The application of exogenous SA effectively increases the contents of these secondary metabolites as terpenoids (e.g. triterpenoids, artemisinin, and glycyrrhizin), phenolic compounds (like chlorogenic acid, quercetin, and caffeic acid), and N-containing compounds (cannabinoids, atropine, withanolide, etc.) by activating the expression of key genes involved in the corresponding biosynthetic pathways[112]. As previously reported, the abundance of two different types of defensive metabolites (chlorogenic acid, and benzoxazinoids) in NahG-expressing maize plants declined, while their contents increased in the exogenous SA-treated wild type maize plants[101]. These reports reveal the positive regulatory role of SA in mediating the level of defensive metabolites in plants during the feeding of insect herbivores. However, it is still largely unknown about the precise mechanism of SA in regulating the biosynthesis of defensive metabolites during herbivore feeding. In-depth exploration of the regulatory mechanism of SA-mediated metabolite biosynthesis is conducive to the development of biopesticides and the reduction of chemical pesticide use.

In addition, SA is also of great importance to plant airborne defense. MeSA, the volatile form of SA, acts as long-distance mobile signals for SAR and evokes airborne defense to protect neighboring plants from herbivores and pathogens they may carry[113]. A recent study showed that the biosynthesis of MeSA is significantly up-regulated in plants attacked by aphids through NAC2-SAMT1 module, and MeSA is further perceived and converted back into SA by neighboring plants to combat aphids and viruses carried by aphids[114]. Collectively, SA plays a significant part in improving plants' resistance to both pathogens and herbivores.

-

Despite the numerous beneficial effects of SA on plant defense responses, the constitutive immune response stimulated by over-accumulated SA can also be disadvantageous to plant fitness, such as inhibiting plant growth[57]. SA is a negative regulator of plant growth, as exogenous application and pathogen-induced accumulation of SA can severely inhibit plant growth and the expression of massive growth-related genes, while auxin supplementation can suppress the SA-mediated immune response against pathogens[97]. It indicates that there is an inverse relationship between growth and defense, and plants need to manage growth and defense in a variety of ways to achieve a balance between the two, which is known as growth-defense trade-off [115].

SA plays key roles in growth-defense trade-off by communicating with other phytohormones, such as auxin, gibberellin, and ethylene[116]. During the defensive response against various biotic factors, SA is largely produced and coordinates plant growth and defense by attenuating the biosynthesis, metabolism, transportation, and signaling of auxin. For instance, SA can promote the accumulation of the microRNA (miR167) to inhibit the expression of auxin responsive factors (ARFs) genes such as ARF6 and ARF8[117]. The interplay between SA and another growth-promoting hormone gibberellin has also been elucidated. The repressor of gibberellin signaling, DELLA, can interact with the positive regulator of SA biosynthesis named ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY 1 (EDS1). They form a feedback regulatory loop to control the balance between growth and SA-mediated immunity against constant infection of pathogens[118]. Additionally, SA and ethylene can antagonistically regulate the formation of apical hook during the process of seedlings emerging from the soil. Exposure of seedlings to various stress factors (e.g. light, temperature, and pathogens) stimulates SA accumulation, which then facilitates the nuclear translocation of NPR1. NPR1 subsequently interacts with EIN3 and represses its activity, thereby disturbing the DNA-binding ability of EIN3 to target genes and inhibiting apical hook formation in etiolated seedlings[119]. Collectively, the crosstalk of SA with other phytohormones sheds light on the growth-defense trade-off in plants. Understanding the interplay of SA with these phytohormones could help parse the regulatory mechanism of growth-defense trade-off, and develop resistant plants with vigorous growth.

In recent years, the essential role of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) in growth and defense trade-off has been extensively explored. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short and single-stranded ncRNAs that play vital roles in plant growth, development, and immunity. Several miRNAs associated with defense have been identified to regulate immune responses against pathogens and herbivores, and to coordinate the grain yield in rice. For example, rice miR164a can activate SA signaling and the expression of defense-related genes to resist the invasion of fungus Rhizoctonia solani[120]. A recent study showed that the long ncRNA (lncRNA) salicylic acid biogenesis controller 1 (SABC1) serves as a pivotal regulator of plant defense and growth. SABC1 enhances the H3K27me3 modification of NAC3 to repress its transcriptional activity, thereby inhibiting SA biosynthesis to suppress immunity and ensure plant growth. Pathogen infection down-regulates SABC1 expression to relieve its inhibitory effect on NAC3, so as to promote SA accumulation and subsequent immune responses to resist pathogens[121]. It suggests that lncRNAs related to immunity are significant regulators that maintain a low level of immunity and a robust growth of plants under normal conditions, and ensure quick immune responses in the case of pathogen infections. It likely provides an effective strategy to improve plant resistance against pathogens and herbivores without sacrificing growth through managing the action of these immunity-related ncRNAs.

-

During the decades of continuous exploration, tremendous advances have been made in understanding the role of SA in plant growth, development, and defense responses against biotic stress. However, there are still many unsolved and perplexing problems that need to be addressed in the future. Firstly, it is widely accepted that plants synthesize SA through ICS- and PAL-mediated pathways and different plant species may prefer to use one or the other to produce SA. More importantly, key enzymes responsible for the conversion of benzoic acid to SA in PAL-pathway remain arcane. The identification of these key enzymes and regulatory components involved in SA biosynthesis, as well as the characterization of predominant and accurate SA biosynthetic pathway in distinct plant species, are valuable for comprehending the biological function of SA and pertinently managing it at the molecular level to emphasize plant resistance. Secondly, the precise molecule mechanisms of SA receptors- and SA binding proteins-dependent signaling pathways, the relationship between the two pathways, and the downstream responsive genes remain to be further investigated. Thirdly, despite the significant role of SA in responding to biotic stress, SA is widely considered to synergistically or antagonistically collaborate with other phytohormones (e.g. JA, ethylene, and ABA) to handle the infection of pathogens and herbivores, and the corresponding regulatory mechanisms are worthy of in-depth study. Furthermore, many transcription factors regulating the biosynthesis of defensive compounds have been determined, but the connection between these transcription factors and SA signaling still needs to be further deciphered. Lastly, verification of important regulators, such as ncRNAs and transcription factors, that balance plant growth and defense is meritorious for broadening our comprehension of SA-mediated signaling networks and providing novel insights into developing desirable resistant plants with robust growth.

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0827), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2024CDJXY016, 2024CDJYDYL-002).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Fang X, Zhang W; draft manuscript preparation: Fang X, Xie Y, Yuan Y, Long Q, Zhang L, Abid G, Zhang W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fang X, Xie Y, Yuan Y, Long Q, Zhang L, et al. 2025. The role of salicylic acid in plant defense responses against biotic stresses. Plant Hormones 1: e004 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0003

The role of salicylic acid in plant defense responses against biotic stresses

- Received: 23 December 2024

- Revised: 08 January 2025

- Accepted: 14 January 2025

- Published online: 18 February 2025

Abstract: Phytohormones are of great significance in plant growth, development, immunity, and stress responses. As one of the promising phytohormones, salicylic acid (SA) is a natural phenolic compound synthesized from chorismate through two distinct pathways mediated by isochorismate synthase and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, respectively. It plays crucial roles in regulating various biological processes related to plant growth and development, as well as in response to diverse biotic and abiotic stresses. Pathogens and herbivores are the most confronting biotic factors that pose severe threats to plant fitness and crop yield. The significance of SA in defense responses against these biotic stresses has been well addressed in the past decades. This review pays attention to the biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling pathways of SA, and SA-mediated defense responses against pathogens and herbivores, thereby providing theoretical perspectives on the regulatory mechanism of SA-mediated immunity under biotic stress and improving the plant fitness and resistance to diseases caused by biotic factors.

-

Key words:

- Biotic stress /

- Defense response /

- Herbivores /

- Pathogens /

- Salicylic acid