-

More and more secreted peptides have been characterized as crucial signaling molecules that facilitate cell-to-cell communication in plants, orchestrating cellular functions[1]. Since Pearce et al. discovered a plant peptide, systemin, composed of 18 amino acids in tomato, an increasing number of plant peptide hormones have been identified[2]. The total number of plant peptide hormones has increased several-fold and now exceeds the total number of classical plant hormones[1]. Secreted peptides play vital roles in numerous aspects of plant developmental processes and responses to biotic and abiotic stressors[3,4]. In these processes, most of them function as signaling molecules, participating in cell-to-cell communication by binding to membrane receptors and coordinating responses with plant hormones[5,6].

Plant peptide signals include secreted peptides and non-secreted peptides. Intercellular signal transduction is primarily mediated by secreted peptides, although non-secreted peptides can also induce signal transduction when released into the intercellular space through cell lysis[7]. In recent years, significant progress has been made in characterizing peptide perception and signal transduction mechanisms[8,9]. However, the biogenesis of these signaling molecules remains poorly understood. All secreted peptides require proteolytic processing to release the mature peptide from their precursors. Currently, the processing events of all the identified secreted peptides are found to be carried out by subtilisins (SBTs), which are serine proteases in the sublilase family[10].

In this review, we discuss several previously confirmed peptide signal processing mechanisms and review the methods used to identify and analyze peptide signal maturation. Summarization of research on the processing of mature peptides provides valuable insights for future studies on the mechanisms and roles of peptide maturation.

-

The mechanism by which precursor proteins are processed into functional mature peptides remained unclear until 2008 when the Phytosulfokines 4 (PSK4) precursor protein was found to undergo N-terminal cleavage by AtSBT1.1. This processing left three additional residues at the N-terminus of the 5-residue peptide, suggesting that additional SBTs might participate in processing PSK precursors, as a complete mature peptide was not released[11]. In 2020, the SBT protease phytaspase 2 (SlPhyt2) in tomato was identified as capable of processing the N-terminal part of PSK precursors to release the mature peptide[12]. The C-terminal processing of PSK1 was later discovered in 2021, with AtSBT3.8 being expressed under osmotic stress to process PSK1 and alleviate stress effects[13]. These findings indicate that peptide signal processing often involves multiple SBTs.

Currently, the processing mechanisms that release mature peptides of several peptide signals, including Inflorescence Deficient in Abscission (IDA), Clavata3/Endosperm Surrounding Region 40 (CLE40), Rapid Alkalinization Factor 23 (RALF23), and Twisted Seed 1 (TWS1), have been characterized. For instance, AtSBT4.12, AtSBT4.13, and AtSBT5.2 redundantly process IDA precursors, releasing the 14-amino-acid mature IDA peptide[14]. In the case of CLE40, AtSBT1.4, AtSBT1.7, and AtSBT4.13 all process the hydroxyproline-modified CLE40 precursor at both the N- and C-termini[15]. AtSBT1.8 precisely cleaves both termini of the TWS1 peptide[16], while AtSBT6.1 processes the N-terminus of the RALF23 precursor to directly produce the functional mature RALF23[17]. Additionally, some enzymes are only identified for processing part of the peptides. For example, AtSBT3.8 can process the N-terminus of the peptides Root Meristem Growth Factor 6 (RGF6) and RGF8[18], while AtSBT2.4 can process the C-terminus of TWS1[19].

Several secreted peptides have been reported to be processed similarly to PSK4 by AtSBT1.1, where the mature peptide is not completely released but retains some N-terminal residues. For example, AtSBT3.8 processes Serine Rich Endogenous Peptide 20 (SCOOP20), and AtSBT3.5 processes SCOOP12, both cleaving at the N-terminus of their precursors without releasing a complete mature N-terminal peptide[20]. AtSBT6.1 processes the N-termini of RGF6 and RGF8 precursors to release peptides retaining partial amino acid residues, which are further processed by AtSBT3.8 to produce fully mature N-terminal peptides[16,21].

These findings suggest that the pre-processing of peptide signal precursors is not an isolated phenomenon but plays a critical role in forming mature peptides. Even in the presence of other SBTs capable of precise peptide processing, knocking out the pre-processing SBTs often results in the loss of the associated peptide function. For example, overexpression of SCOOP20 in materials lacking AtSBT3.8 and its homologs results in a wild-type phenotype[20]. Similarly, GLV1 overexpression leads to an agravitropic root phenotype, but knocking out the partial N-terminus-processing AtSBT6.1 restores the wild-type phenotype[18].

Processing of non-secreted peptides

-

The processing of non-secreted peptides could be distinct from that of secreted peptides. Secreted peptide processing occurs within the secretory pathway or in the apoplast, where precursor proteins interact spatially and temporally with SBT proteases to undergo processing, which is not necessarily true for non-secreted peptides. To date, the only non-secreted peptide with a defined processing mechanism is Plant Elicitor Peptide 1 (PEP1). The processing of PEP1 involves the following steps: In undisturbed root epidermal cells, the inactive METACASPASE 4 (MC4) resides in the cytoplasm, while the precursor PEP1 is attached to the vacuolar membrane. Upon wounding of the plant tissue, a sustained Ca2+ influx is triggered in the cytoplasm, activating MC4 to cleave PROPEP1 and release the mature PEP1 peptide. The mature PEP1 then diffuses into neighboring cells, where it binds to PEPR, activating the defense response[22,23]. More processing mechanisms of non-secreted peptides remain to be elucidated.

-

Current studies indicate that secreted peptides in plants are processed by SBT proteases, suggesting that SBTs play a universal role in the formation of secreted peptide signals[24]. SBTs are alkaline serine proteases first identified in the bacterium Bacillus subtilis[25]. Plant SBTs are crucial in shaping plant structures, determining cell developmental fate, and mediating intercellular communication, thereby regulating various developmental processes. These processes range from embryogenesis and seed development[26] to germination[27], mobilization of seed reserves, vegetative growth, reproductive development, and senescence[14,28,29].

Subcellular sites of peptide processing

-

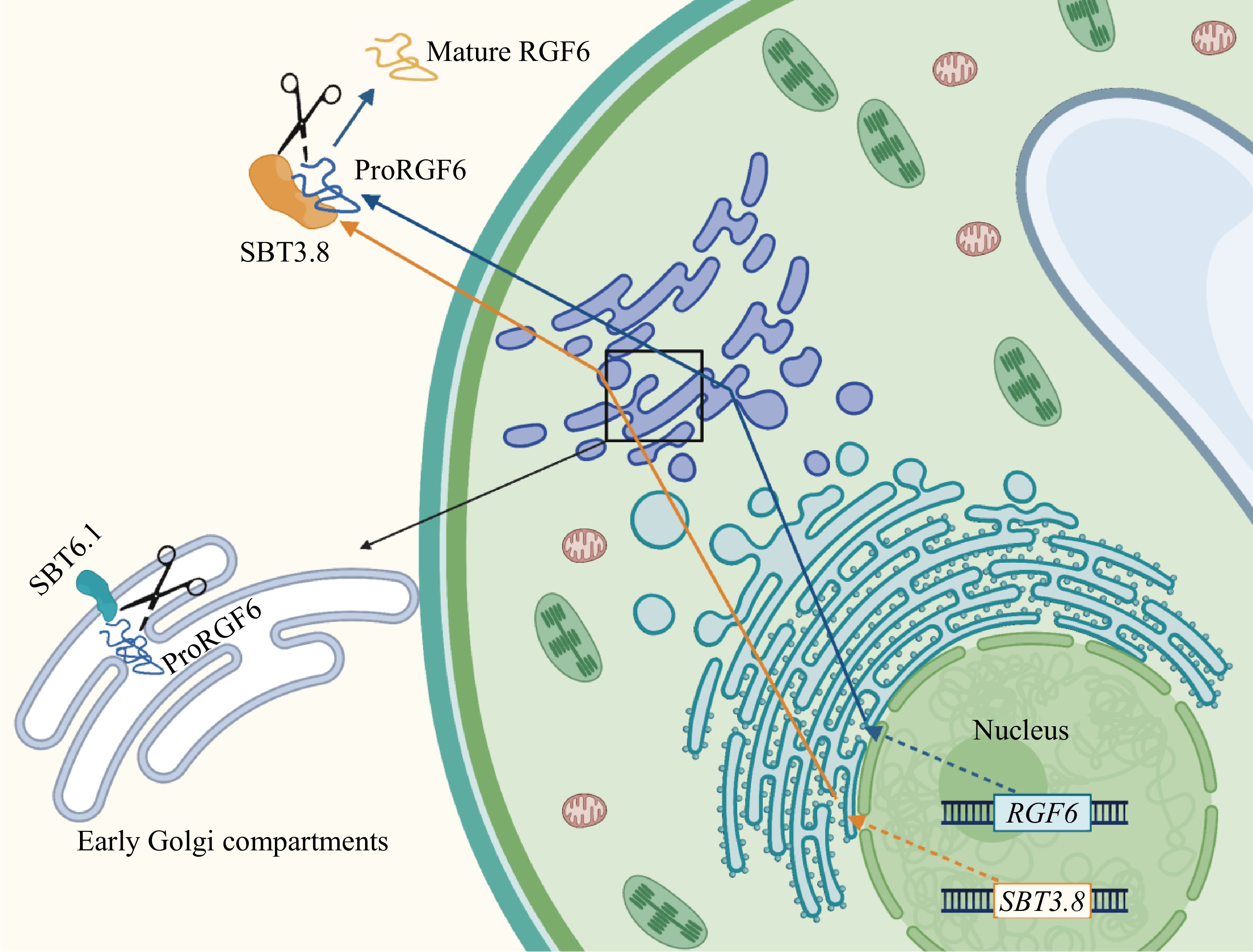

Most SBTs in Arabidopsis are localized in the apoplast[30]. However, unlike other SBTs, AtSBT6.1 is localized at the Golgi apparatus or on the plasma membrane. Similar to its ortholog in humans, Site-1 Protease (S1P), AtSBT6.1 cleaves membrane-anchored bZIP transcription factors at the Golgi, facilitating the translocation of their cytosolic domains to the nucleus to activate expression of Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress response genes[31,32]. In the study of AtSBT6.1 processing of the RGF6 precursor peptide, it was discovered that AtSBT6.1 mediated pre-processing occurs in the early Golgi compartments. Site-directed mutagenesis of the cleavage site on the RGF6 precursor impaired RGF6 precursor secretion, causing a portion of the precursor proteins to be retained at the ER and Golgi[18]. Moreover, AtSBT3.8 was shown to process unprocessed precursor proteins in vitro, suggesting that pre-processing facilitates transportation of precursor proteins out of the Golgi, enabling further processing steps (Fig. 1).

Furthermore, an early study on AtSBT1.1 processing of PSK4 precursor proteins showed that although fluorescence signals for both proteins were observed in the cytoplasm and apoplast, cleavage efficiency was the highest at pH 6.0[11], which aligns with the Golgi pH environment. Given their shared secretory pathway, it is likely that processing occurs during secretion. Post-translational modifications such as tyrosine sulfation, which is required for PSK activity[33,34], occur in the trans-Golgi compartments[35]. Tyrosine sulfation in plants minimally requires an aspartate (Asp) residue adjacent to the Tyr at the N-terminal position[35,36], with additional acidic residues near Tyr significantly enhancing sulfation efficiency[35]. This suggests that pre-processing of precursor proteins may also facilitate post-translational modifications.

For many secreted peptides, precise subcellular locations of processing remain unclear due to the complexity of the process. It is possible that the control of SBT activities, rather than co-localization along the secretory pathway, determines the subcellular site of proteolytic activation. SBT activity is typically regulated by a 77-amino acid prodomain, located between the signal peptide and the catalytic domain, which functions as both an intramolecular chaperone for folding and an inhibitor of the mature enzyme but is not part of the mature enzyme[37]. SBT zymogens remain inactive until the prodomain is autocatalytically cleaved and subsequently released[10,37,38]. The inhibition and latency of SBT activities mediated by the prodomain are pH-dependent. Proteolytic activation occurs in a compartment-specific manner as the pH drops along the secretory pathway. Similarly, SBT3 from tomato requires the acidic pH of post-Golgi compartments for prodomain cleavage and activation[37].

Mechanisms of peptide processing by SBTs

Peptide signal processing dependent on amino acid residue sequences

-

For the processing of plant-secreted peptides, the cleavage is in many cases dependent on basic amino acid residues adjacent to the cleavage sites (Table 1). The cleavage sites of AtSBT1.1, AtSBT3.5, AtSBT6.1, and AtSBT6.2 resemble those of the typical animal S1P (site-1 protease) cleavage motif (RXXL or RXLX, where 'X' represents any amino acid)[39]. However, there are notable distinctions in plants. For example, the main recognition site for AtSBT1.1 during the processing of the PSK4 peptide precursor is SLVL, with the P2-P4 positions being particularly sensitive[11]. AtSBT3.5 prefers the RKLL motif and can recognize the RRLM motif during the SCOOP12 processing[20]. SBT6.1 has been shown to process two types of peptides: the RGF family peptides (RGF6 and RGF9) and RALF23, with cleavage sites at RRAL and RRIL[18,21], respectively. For N-terminal processing of the IDA peptide precursor, the P2-Pro and P4-Tyr residues are critical for substrate recognition by AtSBT4.13[14].

Table 1. Proteolytic processing of plant signaling peptides by SBTs.

Protein ID Substrate Cleave site Ref. AtSBT1.1 proAtPSK4 SLVL↓HTDY [11] AtSBT1.4 proCLE40 QVPT↓GSDPLHHK↓HIPF [15] AtSBT1.7 proCLE40 QVPT↓GSDPLHHK↓HIPF [15] AtSBT1.8 proTWS1 LE↓DYNFPVDP...KPGPIEH↓GTP [16] AtSBT2.4 proTWS1 PIEH↓GTP [19] AtSBT3.5 proSCOOP12 RRLM↓ [20] AtSBT3.8 proPSK1 YIYTQ↓DLN [13] proSCOOP20 VWD↓ [20] proRGF6 VM↓D [18] proRGF9 DM↓D [18] AtSBT4.12 proIDA YLPK↓GVPIPPSAPSKRHN↓SFVN [14] AtSBT4.13 proCLE40 RQVPT↓GSDPLHHK↓HIPF [15] proIDA YLPK↓GVPIPPSAPSKRHN↓SFVN [14] AtSBT5.2 proEPF2 SLPD↓CSYA [40] proIDA YLPK↓GVPIPPSAPSKRHN↓SFVN [14] AtSBT5.4 proCIF4 PVPH↓GSL [41] AtSBT6.1 proRGF6 RRLR↓and RRRAL↓ [21] proRGF9 RRLR↓and RRRAL↓ [18] proRALF23 RRAL↓and RRIL↓ [17] SlPhyt2 proSlPSK HLD↓ [12] Peptide signal processing dependent on aspartic acid recognition

-

In Arabidopsis, the gene AtSBT3.8 encodes a phytaspase protease from the subtilase family. This protease has been shown to have strict Asp specificity under weakly acidic physiological conditions (pH 5.5)[42]. From a synthetic peptide substrate library, the AtSBT3.8 enzyme preferentially cleaved the motifs YVAD and IETD. However, under neutral pH conditions, Arabidopsis phytaspase could also hydrolyze peptide substrates after two other amino acid residues, His and Phe, in addition to Asp[43]. This observation suggests that the enzyme specificity of Arabidopsis phytaspase may be modulated by the cellular environment. AtSBT3.8 can process various secreted peptides, where Asp residues are located at either the P1 or P1' position (the amino acid immediately upstream or downstream of the cleavage site). For instance, in processing the precursor proteins of PSK1 and SCOOP20, Asp is at the P1 position[13,20], while in the processing of CLE40, Asp is at the P1' position[15]. Similarly, SlPhyt2 processes the SlPSK peptide precursor with Asp at the P1 position. Although the Tyr residues near the cleavage sites of SlPSK and CLE40 undergo sulfation, this modification does not appear to affect the protease-mediated processing of the peptides[15,22].

Peptide signal processing dependent on post-translational modification recognition

-

Peptide signals often undergo post-translational modifications, which alter their physicochemical properties—such as net charge, hydrophilicity, and/or conformation—to regulate their binding affinity and specificity to target receptor proteins. Processing of plant-secreted peptide precursors is influenced not only by amino acid motifs but also by amino acid modifications, which play a significant role in some cases of SBT recognition. For example, during TWS1 processing by AtSBT1.8, recognition, and proper cleavage at the N-terminal site depend on sulfation of an adjacent tyrosine residue. Tyrosine sulfation prevents miscleavage of the TWS1 precursor, indicating that the sulfo-tyrosine-dependent interaction with AtSBT1.8 is critical for the specificity in precursor processing and the biogenesis of TWS1 peptides[16].

The CLE40 precursor can be cleaved by SBTs at two sites: the C-terminal site and an internal site of the CLE domain. However, after P4 hydroxylation, the CLE40 precursor protein was cleaved only at the C-terminal site[15]. Hydroxylation of the precursor may be crucial for the activity of plant signaling peptides, especially if it is required for receptor binding and activation[44,45]. For instance, receptor-binding and activation assays indicate that P9 hydroxylation is essential for the maximum activity of IDA[46]. However, the activity of the CLE40 peptide and its P4A mutant variant showed no difference, suggesting that hydroxylation at P4 is not essential for CLE40 bioactivity[15]. Instead, precursor hydroxylation may function to protect the internal cleavage site from SBT-mediated cleavage, thus ensuring the production of bioactive peptides.

-

Among the large group of plant-secreted peptides that have been identified, there are only a limited number of peptides of which the processing mechanisms have been elucidated (Table 1). Previous studies have demonstrated that the processing of secreted peptides is often mediated by SBTs. Several approaches are frequently used in screening for candidate SBTs that are responsible for secreted peptide processing.

The processing of precursor peptides requires spatial and temporal proximity between the peptide precursors and SBT proteases. Several peptide-encoding genes showed developmental or tissue-specific expression[4,47]. This provides a basis for identifying proteases through screening for SBTs with similar expression patterns. For instance, AtSBT3.8 is significantly upregulated after mannitol treatments, aligning with the expression pattern of PSK, and establishing their association[13]. Similarly, overexpression of CLE40 resulted in notable differential expression of SBTs that are involved in the processing of its precursor proteins[15].

Several SBTs have been characterized for their biological functions (Table 2). Substrate peptides of these SBTs could be identified if they have similar functions. For example, AtSBT2.4 regulates the formation of the embryonic cuticle in developing seeds, which is similar to the function of the TWS1 peptide[19,48]. AtSBT5.2 and the Epidermal Patterning Factor 2 (EPF2) peptide are both involved in limiting stomatal development under elevated CO2 levels[40]. Mutations in AtSBT1.2 disrupt stomatal patterning, causing stomatal clustering and a two- to four-fold increase in stomatal density[49]. This phenotype aligns with the negative regulation of stomatal density and development by EPF1 and EPF2 peptides[50]. Similarly, mutations in AtSBT1.4 result in increased inflorescence branching during reproductive development[29]. In rice, a similar phenotype is observed, where members of the EPF family, such as OsEPFL6, OsEPFL7, OsEPFL8, and OsEPFL9, negatively regulate spikelet number per panicle[51]. AtSBT5.4, typically expressed in shoot tips, causes aberrant siliques resembling the clv3 mutant phenotype when ectopically overexpressed[52]. We have also listed the SBT functions of other species in Table 2, providing a reference for future peptide signal processing in other species.

Table 2. Biological functions of SBTs.

Protein ID Biological function Ref. AtSBT1.1 Callus induction [11] Control of cotyledon cell number [53] AtSBT1.2 Controls the development of cell lineages [49] AtSBT1.4 Reproductive development and silique number [29] AtSBT1.6 Regulating germination through GA [54] AtSBT1.7 Mucilage release from seed coats [27] AtSBT2.4 Controls embryonic cuticle formation via [48] AtSBT2.5 Plant morphogenesis and development [55] AtSBT3.3 Immune priming [56] AtSBT3.5 Root development [57] AtSBT3.8 Drought responses [13] AtSBT3.14 Basal immunity priming [58] AtSBT4.12 Abscission of floral organs [14] AtSBT4.13 Abscission of floral organs [14] AtSBT5.2a Control of stomatal development [40] Abscission of floral organs [14] AtSBT5.2b Attenuation of defense gene expression [59] AtSBT5.3 Lateral root development [60] AtSBT5.4 Overexpression produced a clavata-like phenotype [52] AtSBT6.1 Precursor processing [17,31] AtSBT6.2 Protein turnover [61] SlPhyt2 Drought-induced flower drop [12] SlPhyt3 Trigger non-autolytic cell death under oxidative stress [62] SlPhyt4 SlPhyt5 CpSUB1 Fruit ripening [63] GmSLP-1 Seed coat development [64] AcoSBT1.12 Floral transition [65] TaSBT1.7 Plant defense [66] GhSBT27A Drought responses [67] Although SBT cleavage sites are not strictly conserved, some potential substrate peptide precursors can be identified based on the presence of conserved processing sites. For example, AtSBT1.1, AtSBT3.5, AtSBT6.1, and AtSBT6.2 exhibit cleavage sites similar to the animal S1P site-1 protease cleavage motif (RXXL or RXLX, where 'X' represents any amino acid). Peptides such as SCOOP12, GRF6, and RALF23 have been identified through matching similar processing sites[17,20,21]. In plants, a large class of secreted peptides requires tyrosine sulfation modification, with a conserved -DY residue at the N-terminus. AtSBT3.8 has been shown to recognize and process the Asp residues of several such peptides[13,18,20], suggesting its potential to process other members of this class of secreted peptides.

-

Over the past two decades, an increasing number of peptide signal processing pathways have been identified, yielding exciting and unexpected breakthroughs in understanding the biochemical and biological roles of peptide signal processing in plants. A large number of studies have revealed that precursor processing of peptide signals in plants is a continuous process, often involving multiple SBTs. These proteases and their peptide substrates regulate plant development across various stages of the plant lifecycle and play critical roles in adaptive mechanisms to environmental changes and stresses.

However, challenges remain due to the low conservation of SBT processing sites and the generally low expression levels of peptide signals, making the identification of processing mechanisms difficult. To date, only a small number of peptide signal processing pathways have been fully elucidated. Moreover, the specific locations of SBT-mediated precursor peptide processing remain largely undefined, and the mutual regulatory mechanisms between SBTs and peptide signals are poorly understood. With the recent advances in omics and artificial intelligence technologies, we believe that exciting and significant discoveries in this field will be made in the near future.

This work was supported by grants to Guo YF from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270332).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Deng Z, Yang Y, Guo Y; data collection: Marowa P, Pan X, Wu R, Liu T; draft manuscript preparation: Deng D. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhichao Deng, Yalun Yang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Deng Z, Yang Y, Marowa P, Pan X, Wu R, et al. 2025. Processing of plant peptide signals: critical steps mediated by subtilisins. Plant Hormones 1: e003 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0004

Processing of plant peptide signals: critical steps mediated by subtilisins

- Received: 25 December 2024

- Revised: 20 January 2025

- Accepted: 31 January 2025

- Published online: 14 February 2025

Abstract: Secreted peptides are pivotal mediators of intercellular signaling in plants, playing crucial roles in plant growth, development, and stress responses. While substantial progress has been made in understanding peptide perception and signal transduction mechanisms, the mechanisms underlying their biogenesis remain poorly understood. All secreted peptides require proteolytic processing to release their mature forms, and this processing is primarily carried out by subtilisin-like serine proteases (SBTs). SBTs are essential enzymes in plants, being involved in various developmental processes such as embryo development, seed formation, root growth, and organ abscission. This review elucidates the role of SBTs in the processing of secreted peptide precursors, highlighting their involvement in plant signaling during different developmental processes and stress responses. We also summarize recent advancements in understanding the mechanisms of SBT-mediated peptide processing. Key challenges, such as the not-well-conserved nature of SBT recognition sites and the low abundance of peptide signals, are explored alongside promising methodological approaches. Addressing these gaps is critical for advancing our understanding of plant peptide biogenesis and its implications for developmental biology and stress adaptation.

-

Key words:

- Plant secreted peptides /

- Peptide processing /

- Subtilases /

- Signal transduction /

- Plant development /

- Stress response