-

Evolving over millions of years, plants have developed intricate signaling networks that enable them to respond swiftly to stress and adapt to environmental changes in their fixed locations[1]. Ethylene, the simplest alkene and a unique gaseous hormone in plants, regulates diverse processes including plant growth, development, and stress responses, seed germination, root development, sex determination, fruit ripening, organ senescence, as well as responses to pathogen infection, drought, salinity, and hypoxia[2−8]. The evolutionary conservation of ethylene signaling is evident in early-diverging plant lineages. The freshwater alga Spirogyra pratensis demonstrates ethylene responsiveness[9,10], suggesting an ancient origin of this signaling pathway. Furthermore, ethylene regulates 3D gametophore formation in the bryophyte Physcomitrium patens, reinforcing its conserved role in plant development[10,11]. These findings confirm ethylene as an ancient signaling molecule fundamental to plant adaptation throughout evolutionary history.

Ethylene's extensive and critical roles in plant biology have fueled over a century of research. In 1901, Dimitry Neljubov found ethylene-induced morphological changes in etiolated pea seedlings[12]. It was not until thirty years later that Gane identified ethylene as a natural product of plant metabolism[13]. By the 1970s, the biosynthetic pathway of ethylene in plants was fully elucidated[14,15]. A pivotal discovery in the 1990s revealed the dramatic 'triple response' of Arabidopsis etiolated seedlings to ethylene treatment: inhibited root and hypocotyl elongation, exaggerated apical hook curvature, and hypocotyl swelling[16,17]. This phenotype became a powerful tool for genetic screens, leading to the isolation of ethylene response-deficient mutants and marking a significant milestone in dissecting ethylene signaling.

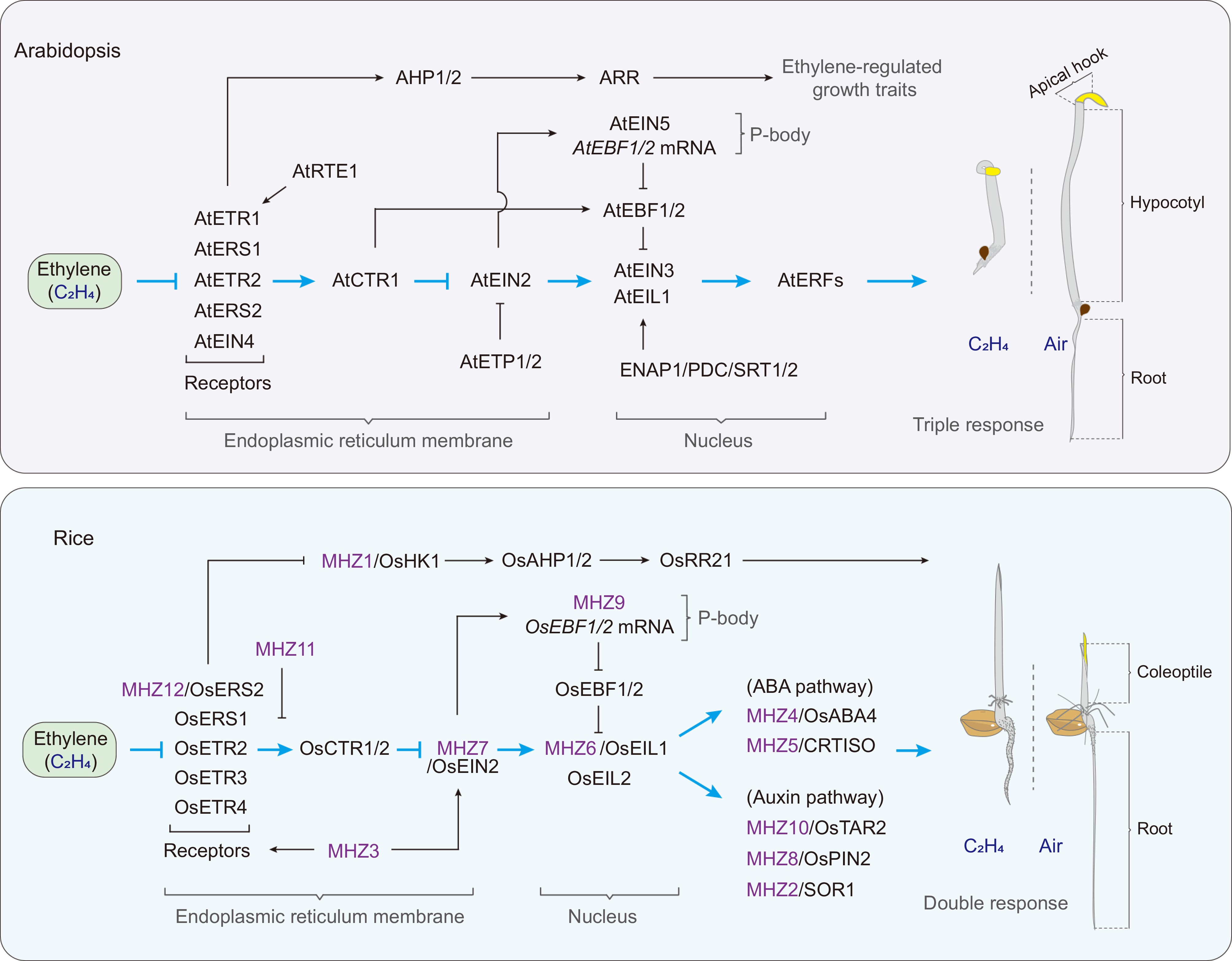

The ethylene signaling pathway in Arabidopsis comprises multiple key components. At the receptor level, five ethylene receptors have been identified: ETHYLENE RESPONSE 1 (AtETR1), ETHYLENE RESPONSE SENSOR 1 (AtERS1), AtETR2, AtERS2, and ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE 4 (AtEIN4)[17−22]. These receptors work in concert with downstream components, including the Raf-like Ser/Thr protein kinase CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE 1 (AtCTR1)[23], the Nramp-like transmembrane protein AtEIN2[24], and the nuclear transcription factors EIN3, EIN3-LIKE1 (AtEIL1), and ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTORS 1 (AtERF1)[25−27]. Additional regulatory complexity is provided by EIN3 BINDING F-BOX1/2 (AtEBF1/2)[28−31], EIN2 TARGETING PROTEIN 1/2 (AtETP1/2)[32], and various chromatin regulators, such as ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE NUCLEAR-ANCHORED PROTEIN 1 (ENAP1)[33], SRT1/2[34], and PYRUVATE DEHYDROGENASE COMPLEX (PDC)[35]. The mechanistic framework for these components follows a precise sequence of events: upon ethylene perception, the negative regulators—ethylene receptors and AtCTR1—are inactivated, which releases the inhibition of AtEIN2, leading to the cleavage of AtEIN2 and the generation of its active C-terminal fragment (EIN2-CEND)[36−38]. The EIN2-CEND exhibits dual functionality: the cytosolic portion binds to AtEBF1/2 mRNA 3' UTR and interacts with multiple cytoplasmic processing body (P-body) factors, thereby inhibiting AtEBF1/2 mRNA translation[39,40]. Simultaneously, another portion of the EIN2-CEND enters the nucleus, where it interacts with chromatin regulators and collaborates with transcription factors AtEIN3 and AtEIL1 to regulate the expression of downstream ethylene-responsive genes, ultimately triggering the characteristic 'triple response'[25,33−35]. Beyond this well-determined signaling cascade, Park et al. demonstrated that ethylene induces the shuttling of AtCTR1 from the ER membrane to the nucleus, acting as a positive regulator in the secondary ethylene response[41]. Additionally, the ethylene receptor AtETR1 exhibits histidine kinase (HK) activity, which may facilitate phosphorelay through the AtETR1-AHP-ARR pathway, thereby adding an extra layer of regulation to the ethylene response[42−45] (Fig. 1). These findings expand the classical linear model of ethylene signaling, revealing an intricate regulatory network that enables plants to achieve both rapid and precise hormonal responses through multiple interconnected mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Model of ethylene signal transduction in Arabidopsis and rice. In Arabidopsis, ethylene receptors, AtCTR1, and AtEIN2 form a complex on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Ethylene binding inactivates the receptor/CTR1 complex, relieving repression on AtEIN2. The cleaved EIN2-CEND then follows two pathways: one part enters the P-body, where it inhibits AtEBF1/2 mRNA translation via AtEIN5, while the other translocates to the nucleus to regulate downstream gene expression with AtEIN3/EIL1, ENAP, PDC, and SRT1/2. AtRTE1 and AtETP1/2 act as negative regulators of ethylene signaling, targeting AtETR1 and AtEIN2, respectively. AtCTR1 also can enter the nucleus to repress AtEBF1/2, exerting a positive regulatory role. Also, a non-canonical pathway exists in which AtETR1 signals to histidine-containing AHP, which subsequently activates ARR to modulate ethylene-mediated growth traits. The ethylene receptor-OsCTR1/2-OsEIN2-OsEIL1/2 pathway in rice is highly conserved compared to Arabidopsis. There also exists a distinct MHZ1 pathway independent of OsEIN2. Furthermore, several new regulatory components have been identified: MHZ11 regulates signaling by inhibiting the activation of the ethylene receptor/OsCTR2 complex, while MHZ3 not only stabilizes OsEIN2 but also enhances the activity of the ethylene receptor/OsCTR2 complex. MHZ9 is involved in the translation repression of OsEBF1/2 mRNA in the P-body. The ABA and auxin signaling pathways also interact with the ethylene signaling pathway to co-regulate double responses in rice. The light blue arrows represent the canonical ethylene signaling pathway, while the black arrows indicate non-canonical ethylene signaling pathways or regulation of the components of the canonical ethylene signaling pathway. The 'T' blunt ends indicate negative regulation.

Rice serves as both a critical staple crop feeding nearly half of the world's population and a premier model organism for studying monocot biology[46]. Interestingly, Yang et al. discovered that rice etiolated seedlings display a distinctive ethylene response that differs not only from the dicot model Arabidopsis but also from other major monocot species, including Brachypodium distachyon, maize, wheat, and sorghum[47]. A 'double response' phenotype is observed in rice etiolated seedlings, where ethylene promotes the elongation of the coleoptile while inhibiting the elongation of the root[47]. This unique ethylene response might be an adaptation to rice's semi-aquatic, hypoxic environment[48]. This distinctive phenotype enabled Ma et al. to develop a robust high-throughput screening system, leading to the identification of multiple ethylene-insensitive mutants. These mutants were designated 'mao hu zi' (mhz) based on their characteristic adventitious root morphology[49]. In addition to the conserved ethylene signaling components, such as ethylene receptors[50−52], MHZ7/OsEIN2[49], MHZ6/OsEIL1[53], OsCTR1/2[54,55], and OsEBF1/2[56], the cloning and functional analysis of new components, including MHZ1/OsHK1[50], MHZ2/SOR1[57], MHZ3[58,59], MHZ4/OsABA4[60], MHZ5/CRTISO[52], MHZ8/OsPIN2[61], MHZ9[56], MHZ10/OsTAR2[62], and MHZ11[55], have led to the construction of a comprehensive ethylene signaling pathway in rice (Fig. 1). These studies demonstrate that while rice retains the core ethylene signaling machinery, it has evolved unique regulatory mechanisms compared to Arabidopsis, reflecting its distinctive physiological adaptations (Table 1).

Table 1. Components of Arabidopsis and rice in the ethylene signaling pathway.

Arabidopsis Rice Protein Gene No. Phenotype (triple response)

(if unspecified, it is loss-of-function)Ref. Protein Gene NO Phenotype (double response)

(if unspecified, it is loss-of-function)Ref. Ethylene receptors Prokaryote-like histidine kinase AtETR1 AT1G66340 Loss: different degrees of constitutive ethylene response

Gain: ethylene insensitivity[19] OsERS1 Os03g49500 Root ethylene semi-hypersensitivity [52] AtERS1 AT2G40940 [20] MHZ12/

OsERS2Os05g06320 Loss: root ethylene semi-hypersensitivity;

Gain: root-insensitive and coleoptile-semi insensitive ethylene response[50, 52] AtERS2 AT1G04310 [21] OsETR2 Os04g08740 Root ethylene semi-hypersensitivity [4, 52] AtETR2 AT3G23150 [22] OsETR3 Os02g57530 Root ethylene semi-hypersensitivity [51] AtEIN4 AT3G04580 [21] OsETR4 Os07g15540 Unknown [51] Cellular signaling components Serine-threonine protein kinase AtCTR1 AT5G03730 Constitutive triple response [23] OsCTR1 Os09g39320 Root ethylene semi-hypersensitivity [54] OsCTR2 Os02g32610 Root ethylene semi-hypersensitivity [54,55] Nramp-like membrane protein AtEIN2 AT5G03280 Ethylene insensitivity [24] MHZ7/

OsEIN2Os07g06130 Root and coleoptile ethylene insensitivity [49,115] Transcription factor AtEIN3 AT3G20770 Ethylene insensitivity [25] MHZ6/

OsEIL1Os03g20790 Root-insensitive and coleoptile-slightly insensitive ethylene response [53] AtEIL1 AT2G27050 Reduced ethylene sensitivity [25] OsEIL2 Os07g48630 OsEIL2-RNAi:

coleoptile ethylene insensitivity[53] Regulators F-box protein AtEBF1 AT2G25490 ebf1 ebf2: constitutive ethylene response [28−31] OsEBF1 Os06g40360 Hypersensitivity of root and coleoptile [56] AtEBF2 AT5G25350 OsEBF2 Os02g10700 Hypersensitivity of root and coleoptile [56] AtETP1 AT3G18980 amiR-ETP1/ETP2:

constitutive ethylene response[32] Unidentified AtETP2 AT3G18910 Membrane protein AtRTE1 AT2G26070 Enhanced ethylene sensitivity [86] OsRTH1 Os01g51430 Unknown [90] AtMHL1 AT1G75140 mhl1 mhl2: reduced ethylene sensitivity [58] MHZ3 Os06g02480 Root and coleoptile ethylene insensitivity [58] AtMHL2 AT1G19370 Enzyme AtEIN5 AT1G54490 Reduced ethylene sensitivity [116,117] Function not studied Arabidopsis homolog not identified MHZ11 Os05g11950 Root-specific ethylene insensitivity [55] Histidine kinase AtAHK5 AT5G10720 Enhanced ethylene sensitivity [107] MHZ1 Os06g44410 Root-specific ethylene insensitivity [50] RNA-binding protein Arabidopsis homolog not identified MHZ9 Os01g69990 Root-insensitive and coleoptile- semi-insensitive ethylene response [56] Ethylene signal transduction involves a sophisticated interplay of protein-protein, protein-RNA, and protein-DNA complexes, each precisely regulated to ensure appropriate cellular responses. This review examines recent advances in understanding these molecular interactions, revealing how different protein complexes, namely ethylene perception complex (EPC), signal transduction complex (STC), translation regulatory complex (TRC), and nuclear regulatory complex (NRC), coordinate to achieve precise signal transmission and response specificity in plant ethylene signaling. It should be noted that although multiple plant species were mentioned, we are more focused on the protein complexes in rice, with comparisons to those in Arabidopsis. This modular perspective may provide deeper insights into the molecular architecture underlying ethylene signaling in plants.

-

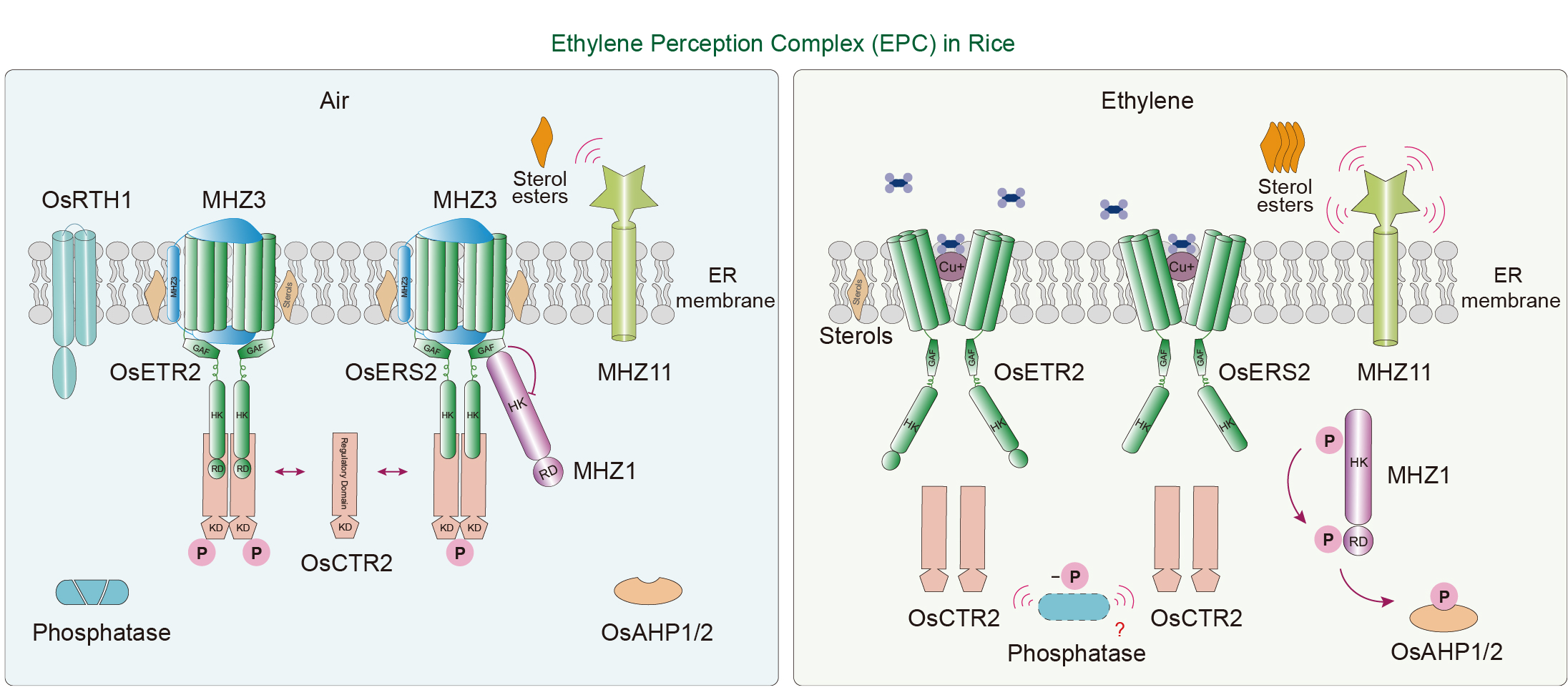

At the ER membrane, ethylene receptors associate with multiple regulatory factors to form signaling complexes, referred to as the ethylene perception complex (EPC), which facilitate ethylene perception and initiate the hormone response cascade (Fig. 2). This section reviews the characteristics of ethylene receptors and their intricate interactions with associated regulatory proteins.

Figure 2.

Ethylene perception complex (EPC) in rice. In the absence of ethylene (left), an EPC is formed with ethylene receptors at its core, preventing signaling activation. MHZ3 interacts with OsETR2 and OsERS2 to stabilize OsCTR2 on the ER membrane, keeping it autophosphorylated and inhibiting the canonical pathway. The GAF domains of ethylene receptors also bind histidine kinase MHZ1, suppressing its activity and blocking the phospho-relay pathway. Upon ethylene perception by the receptors (right), the EPC dissociates, triggering the activation of ethylene signaling. Ethylene binding weakens the interaction between the receptors and MHZ3, leading to the dissociation of OsCTR2. An unknown specific phosphatase may dephosphorylate OsCTR2, inactivating its inhibition of the canonical pathway. Meanwhile, MHZ1 dissociates from the EPC, activating the MHZ1-mediated phospho-relay pathway, transferring phosphate groups to OsAHP1/2, and activating the non-canonical ethylene signaling pathway. Under the influence of ethylene, MHZ11 converts membrane sterols into sterol esters, potentially increasing membrane fluidity and promoting the dissociation of the EPC. The arrows indicate biological processes. The 'T' blunt end indicates negative regulation.

Ethylene receptor domain structure and perception

-

Ethylene receptors are the central components of the EPC, playing critical roles in ethylene signal perception and regulating the on/off state of downstream signaling. The ethylene receptor family comprises a group of prokaryotic-derived two-component His protein kinase-related receptors, primarily localized to the ER membrane[63,64]. Functioning as negative regulators of ethylene signaling, ethylene receptors exhibit remarkable functional plasticity: dominant gain-of-function mutations result in ethylene insensitivity, while loss-of-function mutations trigger constitutive ethylene responses[19,63]. Ethylene receptors typically comprise an N-terminal ligand-binding domain, a GAF (cGMP phosphodiesterase/adenylyl cyclase/FhlA) domain, and a HK domain, with some receptors also featuring a receiver domain at their C-terminus[65]. Based on phylogenetic relationships and sequence characteristics, ethylene receptors are classified into two subfamilies. In Arabidopsis, AtETR1 and AtERS1 belong to subfamily I, while AtETR2, AtERS2, and AtEIN4 are classified under subfamily II[64]. Similarly, in rice, OsERS1 and OsERS2 are members of subfamily I, whereas OsETR2, OsETR3, and OsETR4 fall under subfamily II[61]. Subfamily I receptors generally retain HK activity, whereas the HK domain in subfamily II receptors has degenerated[66]. Furthermore, subfamily II receptors often possess an additional transmembrane domain at their N-terminus[66,67]. Among the ethylene receptors in Arabidopsis, AtETR1, AtETR2, and AtEIN4 contain a receiver domain, while in rice, the receiver domain is found exclusively in the receptors of subfamily II[61]. Subfamily II receptors in rice, Arabidopsis, and tobacco all exhibit Ser/Thr kinase activity in vitro[4,68]. This activity was first identified in the tobacco subfamily II ethylene receptor NTHK1[68]. Additionally, another tobacco subfamily II member, NTHK2, and Arabidopsis AtERS1 were found to possess dual HK and Ser/Thr kinase activities[69,70]. Taken together, ethylene receptors exhibit both conservation and divergence in their structure and biochemical properties.

Studies across multiple species have revealed functional differentiation among ethylene receptors[59,71−73]. In Arabidopsis, the subfamily I receptors AtETR1 and AtERS1 serve as the principal ethylene receptors, with subfamily II receptors unable to fully compensate for their functions[72]. Within subfamily I, AtETR1 and AtERS1 play distinct roles in regulating ethylene responses, with AtERS1 potentially enhancing ethylene signaling in an AtETR1-dependent manner[72,74]. In tomato, SlETR3, SlETR4, and SlETR6 are highly expressed in the early stages of fruit ripening, while SlETR1, SlETR2, SlETR5, and SlETR7 are more prominent at later stages. This expression pattern indicates the functional differentiation of these receptors during ripening[73]. In comparison, members from both subfamilies of rice ethylene receptors play a role in ethylene response. Except for OsETR4 which is predominantly expressed in reproductive tissues, single loss-of-function mutants of other ethylene receptors result in a certain degree of constitutive ethylene response in etiolated seedling roots, indicating functional redundancy[52]. However, the regulatory capacity of different receptor members differs when it comes to the molecular level, as their regulation of OsCTR2 phosphorylation varies significantly. In the Osetr2 mutant, OsCTR2 phosphorylation is undetectable under normal conditions, while it remains detectable in Osers1, Osers2, and Osetr3 mutants. The loss of phosphorylation is more pronounced in the Osetr2 ers2 and Osetr2 etr3 double mutants. These findings suggest that the subfamily II receptor OsETR2 plays a key role in regulating OsCTR2 function, with other ethylene receptors showing supplementary contributions[59]. Consistent with this finding, in Arabidopsis, the increased nuclear accumulation of AtCTR1 in the triple mutant Atetr2-3 ers2-3 ein4-4 highlights the unique role of subfamily II receptors in regulating AtCTR1 function[41]. Moreover, the tobacco subfamily II ethylene receptor NTHK1 plays a more significant role in seedling growth, ethylene sensitivity, and salt response than the subfamily I member NtETR1[75]. Another study on subfamily II receptors in Arabidopsis demonstrated that AtETR2 exhibits affinities for both AtCTR1 and AtEIN2 comparable to those of AtETR1[76]. However, AtETR1, which contains the receiver domain, has a stronger affinity for AtCTR1 compared to receptors lacking this domain, such as AtERS1. These structural differences may influence the signal output of CTRs, leading to functional differentiation among the receptors[77,78].

Ethylene receptors function as homodimers, with two monomers covalently linked by disulfide bonds[79,80]. The role of these disulfide bonds in receptor function remains inconclusive[63]. The ethylene-binding site (EBD) is located in the conserved N-terminal transmembrane region, where highly conserved Cys and His residues are involved in chelating the copper cofactor[79,81]. Although the precise stereochemistry of copper cofactor binding by receptor dimers remains debated, the metal-binding capacity of these receptors has been definitively shown to be essential for ethylene perception[81,82]. Previous studies revealed the Arabidopsis Atetr1-1 mutant exhibits ethylene insensitivity due to a Cys-to-Tyr substitution at position 65, which disrupts copper chelation and prevents ethylene binding[83]. In addition to mutations at the EBD, other functionally significant missense mutations have been identified in the N-terminal ligand-binding domain. For example, the dominant gain-of-function mutant Osers2d carries an Ala32Val substitution in OsERS2, which corresponds to the Atetr1-3 mutation in Arabidopsis and similarly confers dominant ethylene insensitivity[19,50]. These ethylene insensitivity phenotypes of these mutants may arise from either the loss of ethylene binding capacity; or impaired signal output of receptors. Azhar et al. revealed that the Asp25 site in Arabidopsis AtETR1 indirectly regulates copper cofactor coordination through His69 and interacts with Lys91 in the transmembrane region to participate in ethylene signal transduction. This site is conserved in ETR1-like proteins, but it can naturally mutate to Asn in several cyanobacteria and plants[84]. Although the Asn variant reduces copper/ethylene binding affinity in vitro, its in vivo signaling function remains intact, suggesting that natural variation may fine-tune ethylene binding affinity to achieve adaptive regulation, maintaining the receptor's dynamic balance[84]. Overall, the ligand perception process of ethylene receptors involves precise inter- and intra-molecular regulation.

The ethylene receptor-ligand binding initiates a fast and efficient signaling cascade. In rice, a 15-min ethylene treatment sufficiently triggers a rapid decrease in OsCTR2 phosphorylation, which is swiftly restored upon ethylene removal[59]. In Arabidopsis, ethylene rapidly inhibits hypocotyl elongation, with the growth rate promptly increasing once ethylene is removed[30]. These findings highlight the ability of ethylene receptors to mediate rapid and reversible responses, ensuring precise and dynamic regulation of ethylene signaling. Additionally, in Arabidopsis, ethylene receptors are capable of recognizing ethylene concentrations spanning six orders of magnitude (from 0.2 nL/L to 1,000 μL/L)[85], but the mechanism underlying this high ability to sense a wide range of concentrations remains unclear.

Helpers involved in ethylene receptor function

-

The proper function of ethylene receptors requires assistance from several interacting proteins and membrane components. This section discusses the ER-membrane localized regulatory components that function collectively to fine-tune receptor activity, achieving precise regulation of ethylene signaling.

The protein network centered around Arabidopsis REVERSION-TO-ETHYLENE SENSITIVITY1 (AtRTE1) is involved in the regulation of ethylene receptor function. Screening for suppressors of the Arabidopsis Atetr1-2 mutant revealed that loss-of-function AtRTE1 can rescue its ethylene-insensitive phenotype[86]. AtRTE1 is localized to the Golgi/ER membrane and positively regulates AtETR1 by modulating the ethylene signaling pathway through the N-terminal transmembrane domain of AtETR1. Interestingly, AtRTE1 specifically interacts with AtETR1, how this specificity is achieved remains unclear[87−89]. In rice, three RTE1 homologs (OsRTH1-OsRTH 3) have been identified. OsRTH1, most similar to AtRTE1, can complement the Arabidopsis Atrte1-2 mutant, whereas overexpression of OsRTH2 and OsRTH3 does not[90]. Similarly, overexpression of the tomato SlRTE1 homolog Green Ripe (GR) reduces fruit sensitivity to ethylene, suppressing ripening without causing whole-plant ethylene insensitivity[91]. In addition, some proteins, including ARGOS, Cb5, and LTPs, regulate ethylene receptor function via interaction with AtRTE1[92−95]. In summary, RTE1 and its interacting proteins are key regulators of ethylene receptor function.

Rice GDSL lipase MHZ11 was identified as a regulator of the ethylene receptor/CTR2 complex. MHZ11, localized to the ER membrane, positively regulates ethylene responses in rice roots and likely influences the function of the receptor/OsCTR2 complex by acting upstream of OsCTR2. Further studies revealed that OsCTR2 exists in two states in vivo: phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated. Ethylene treatment inhibits the phosphorylation and kinase activity of OsCTR2, while the phosphorylation state of OsCTR2 is locked in mhz11 mutants, abolishing the inhibitory effect of ethylene. Functional analysis revealed that MHZ11 hydrolyzes various phospholipids, releasing free fatty acids. These fatty acids are then incorporated into sterol esters, leading to a reduction in free sterol content within membrane microdomains. This alteration in membrane composition weakens the interaction between the receptor and OsCTR2 within microdomains, diminishing OsCTR2 phosphorylation and ultimately activating downstream ethylene signal transduction[55] (Fig. 3). In Arabidopsis, studies have found that phosphatidic acid can bind to AtCTR1 and inhibit its kinase activity[96]; however, whether a regulator similar to MHZ11 exists requires further investigation.

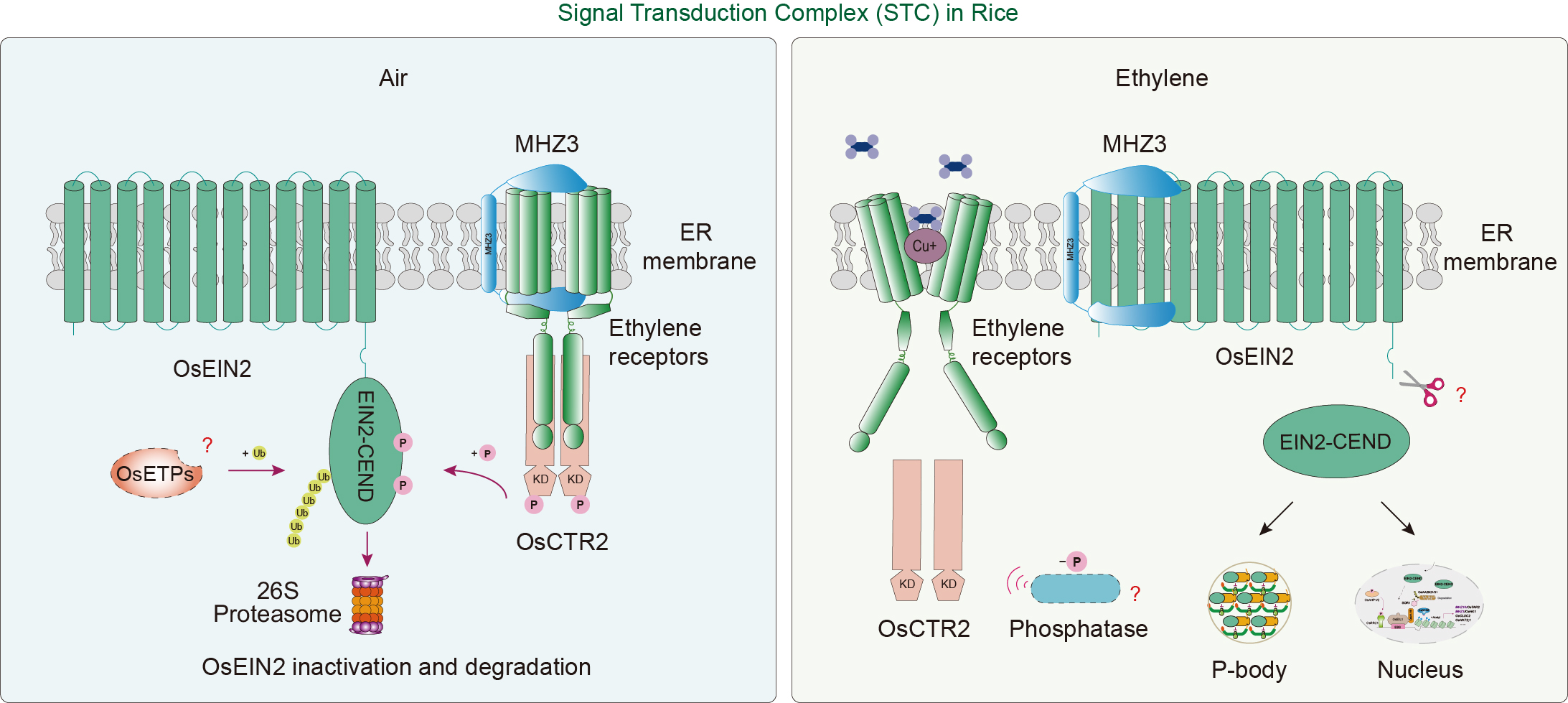

Figure 3.

Signal transduction complex (STC) in rice ethylene signaling. In the absence of ethylene (left), the STC centered on OsEIN2 is unstable. OsEIN2 undergoes phosphorylation by the serine/threonine kinase OsCTR2 and ubiquitination by potential F-box protein OsETPs. These modifications lead to the inactivation and degradation of OsEIN2 via the 26S proteasome, thereby preventing OsEIN2-mediated ethylene signaling. Upon ethylene binding (right), OsCTR2 loses activity and is unable to phosphorylate OsEIN2. Meanwhile, the membrane protein MHZ3 binds to OsEIN2, inhibiting its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. The stabilized OsEIN2 is cleaved to produce an active C-terminal fragment, which is partially directed to the P-body and partially translocated to the nucleus, thereby completing ethylene signal transduction. Red arrows indicate biological processes, while the black arrows indicate subcellular translocation.

Recent studies on the rice membrane protein MHZ3, which was previously identified as a positive regulator of MHZ7/OsEIN2 stability, have revealed that it plays a significant role in regulating the function of ethylene receptors[58,59]. In the mhz3 mutant, OsCTR2 phosphorylation is completely lost, while MHZ3-overexpressing lines exhibit enhanced phosphorylation of OsCTR2. MHZ3 and ethylene receptors jointly regulate OsCTR2 phosphorylation in a mutually dependent manner. Similar to ethylene receptor mutants (Osetr2, Osetr2 etr3, and Osetr2 ers2), the mhz3 mutant shows reduced binding between ethylene receptors and OsCTR2, along with decreased OsCTR2 membrane localization[55]. The possible mechanism of MHZ3 is as follows: in the air, MHZ3 binds to ethylene receptors, maintaining OsCTR2 activity and inhibiting ethylene signaling. Upon ethylene binding, the interaction between MHZ3 and the receptors weakens, releasing OsCTR2 from the membrane, reducing its activity, and allowing ethylene signaling to proceed (Fig. 3). Furthermore, in mhz3 mutant background, transgenic lines overexpressing the stable OsEIN2 (OsEIN2/mhz3) exhibit constitutive ethylene response phenotypes in air but fail to respond further to exogenously applied ethylene and 1-MCP[59]. This suggests that MHZ3 may also be involved in regulating ethylene perception. MHZ3 sequence is conserved from algae to land plants[58], suggesting an important role of MHZ3 in ethylene signaling. However, whether the regulatory function on the ethylene receptor/CTR complex is conserved requires further investigation.

In addition to AtRTE1, MHZ11, and MHZ3, several other proteins modulate ethylene receptor function through interactions. Arabidopsis AtCPR5 regulates ethylene signaling by interacting with the N-terminal domain of ETR1 and controlling the nucleoplasmic transport of ethylene-related mRNAs[97,98]. Additionally, AtTPR1 interacts with the ethylene receptor AtERS1, and overexpression of both AtTPR1 and tomato SlTPR1 leads to an enhanced ethylene response[99]. In tobacco, NtNEIP2 and NtTCTP interact with the ethylene receptor NTHK1. Ethylene induces NtNEIP2 to inhibit the ethylene response and promote growth recovery, while NtTCTP stabilizes NTHK1, inhibiting proteasomal degradation, and thereby suppressing the ethylene response[100,101]. Some ethylene receptors in Arabidopsis and tomato undergo ethylene-induced degradation via the 26S proteasome[102,103]. Identifying ubiquitin ligases involved in receptor degradation will enhance our understanding of the EPC and ethylene receptor regulation.

Ethylene receptor function is regulated by a variety of interacting proteins that influence receptor perception, signaling, and degradation. However, the mechanistic understanding of how these proteins integrate into the ethylene perception complex and modulate receptor function remains limited. A compelling hypothesis is that different ethylene receptor members perform specialized functions through selective interactions with specific protein partners.

-

The molecular effects of ethylene perception on receptor function are not fully understood. Possible mechanisms include modulation of kinase activity, changes in receptor oligomerization, or switching between active and inactive states. Subsequently, the ethylene receptor transmits the signal to the components within the EPC that receive it. These targets vary between species: in Arabidopsis, AtCTR1 is the main signal recipient, while rice uses both OsCTR2 and MHZ1/OsHK1. Moreover, ethylene receptors can also initiate signaling through alternative pathways independent of these canonical components.

In the canonical ethylene signaling pathway, AtCTR1 in Arabidopsis mediates the output of receptor signals and acts downstream of the ethylene receptors as a negative regulator of ethylene signaling[37,77] (Fig. 1). The kinase domain of AtCTR1 is active when dimerized, and AtCTR1 relies on its autophosphorylation sites to form homodimers[104]. In the absence of ethylene, the kinase domain of AtCTR1 interacts with the EIN2-CEND region, catalyzing the phosphorylation of Ser645 and Ser924[37]. Mutations in the active site or autophosphorylation sites of the kinase domain lead to the loss of AtCTR1's ability to phosphorylate AtEIN2[41]. Recent studies have shown that ethylene induces AtCTR1 to enter the nucleus and exerts a positive regulatory role, independent of its kinase activity and autophosphorylation capability[41]. Rice has three homologs of Arabidopsis AtCTR1: OsCTR1, OsCTR2, and OsCTR3. OsCTR1 and OsCTR2 are more similar to AtCTR1, and their nonsense mutants show a constitutive ethylene response, confirming their roles as negative regulators[54,55]. OsCTR2 was shown to undergo autophosphorylation in vivo, which was proven essential for its function[55,59]. Both ethylene treatment and receptor mutations (particularly in OsETR2) lead to a decrease in membrane-localized OsCTR2[59] (Fig. 2). Unlike Arabidopsis AtCTR1, nuclear-localized OsCTR2 was not detected, suggesting functional divergence[41]. Previous studies show that in the OsERS2 gain-of-function mutant Osers2d, OsCTR2 phosphorylation remains unchanged and unresponsive to ethylene. While Osers2d retains an intact ethylene binding site, it fails to transmit the signal to OsCTR2, highlighting the importance of proper receptor-mediated signal transmission for OsCTR2 regulation[55]. Ethylene receptor-CTR interactions have been demonstrated in Arabidopsis[77], rice[55,59], and tomato[105]. However, whether CTRs, in turn, exert a regulatory effect on receptor function remains an open question, requiring further investigation.

In rice, the MHZ1 pathway, independent of OsEIN2, receives signals from the ethylene receptor and regulates the ethylene response in roots (Fig. 1). Histidine kinase MHZ1/OsHK1 mediates the ethylene response through the MHZ1-OsAHP1/2-OsRR21 phosphorelay pathway. The ethylene receptors interact with MHZ1/OsHK1 through its GAF domain, employing dual mechanisms to inhibit MHZ1/OsHK1 function: direct suppression of its kinase activity and tethering it to the ER membrane, thereby preventing interaction with downstream signaling components. Ethylene perception relieves this inhibition effect, activating the phosphorelay pathway to trigger transcriptional reprogramming in the nucleus[50] (Fig. 3). While GAF-GAF domain interactions were known to form ethylene receptor dimers, this study shows that GAF also mediates interactions with downstream components for signaling output[50,106]. Studies in Arabidopsis have revealed that AtETR1 integrates ethylene and cytokinin signaling to regulate root growth through a multistep phosphorelay pathway. Notably, this signaling mechanism is independent of the canonical AtCTR1-AtEIN2-AtEIN3 ethylene pathway[43]. In comparison to MHZ1/OsHK1's predominant role as a positive regulator of ethylene signaling in rice, its Arabidopsis counterpart, AHK5, functions as a negative regulator and plays only a minor role in ethylene response[107]. The molecular basis underlying this divergence between homologous proteins remains unknown. It is worth testing the function of MHZ1/OsHK1 in other plant species.

In addition to AtCTR1, OsCTR2, and MHZ1/OsHK1, several clues indicate the existence of additional signal output pathways operating downstream of ethylene receptors. For instance, overexpression of the N-terminal region of Atetr1-1 (1-349 aa) partially suppresses the Atctr1-1 phenotype, suggesting that the N-terminal part of AtETR1 can conditionally mediate receptor signal output independent of AtCTR1[108]. Furthermore, the ethylene receptor Atetr1 ers1-3 in Arabidopsis exhibits more severe growth defects than the Atctr1 mutant[109]. Similarly, the rice Osers1 ers2 double mutant develops severe growth defects that are not phenocopied by OsEIN2 overexpression[61]. These data suggest that ethylene receptors may have additional roles in regulating plant development that are not executed through the CTR-EIN2 module. Bisson & Groth found that the C-terminal domain of EIN2 interacts with the kinase domain of ethylene receptors in Arabidopsis and tomato[110]. The conserved NLS of AtEIN2 is crucial for complex formation with AtETR1, implying that AtEIN2 is a component of the ethylene receptor signal output[111].

Ethylene receptors are central to the EPC, yet how they regulate the activity of CTRs or MHZ1 in response to ethylene binding remains poorly understood. Future structural analyses of these receptor complexes could provide valuable insights into their signaling dynamics and help clarify the differential outputs observed among receptor subtypes.

-

EIN2 is a central component of the ethylene signal transduction pathway, receiving signals from EPC and transmitting them to the nucleus and the P-body[36,38−40,77]. Its N-terminal domain, anchored to the ER membrane, resembles the Nramp-like sequence. The C-terminal region contains a plant-specific hydrophilic domain crucial for triggering the ethylene response[24]. Mutants of EIN2 in Arabidopsis and rice show complete insensitivity to ethylene[24], and similar mutations in EIN2 homologs from other species, including Medicago truncatula and tomato, lead to a failure to respond to ethylene or block fruit ripening[112,113]. EIN2, together with components such as AtCTR1 and AtETP1/2 in Arabidopsis[32], as well as MHZ3 in rice[58], constitutes the signal transduction complex (STC), which regulates the ethylene signaling cascade (Figs 1 & 3).

AtCTR1 and AtETP1/2 block the activation of AtEIN2

-

In Arabidopsis, the activity of the AtEIN2 function is tightly controlled under normal growth conditions to prevent premature activation of ethylene signaling. AtCTR1-mediated phosphorylation plays an important role in regulating AtEIN2 function. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments have demonstrated that the kinase domain of AtCTR1 binds EIN2-CEND and phosphorylates Ser645 and Ser924[37,114]. Mutations at these sites (Ser645Ala/Ser924Ala) trigger a constitutive ethylene response, mirroring Atctr1 mutants, and highlighting the importance of these phosphorylations in repressing AtEIN2 signaling. Phosphorylation of Ser924 exerts a stronger inhibitory effect on EIN2 than Ser645[37]. Overall, AtCTR1 and AtEIN2 form a regulatory complex that suppresses ethylene signaling in the absence of ethylene through the phosphorylation of specific residues[36,37]. OsCTR2 in rice undergoes autophosphorylation, and its activity depends on its own kinase activity[55,59]. Whether the effects of OsCTR2 and AtCTR1 on EIN2 are the same requires further investigation.

Besides phosphorylation, AtEIN2 protein level is regulated by ubiquitination. Qiao et al. identified the F-box proteins AtETP1 and AtETP2 that interact with EIN2-CEND. In vitro, both AtETP1 and AtETP2 bind directly to EIN2-CEND. Knockdown of AtETP1 and AtETP2 leads to a constitutive ethylene response, while overexpression of these proteins reduces ethylene sensitivity. Ethylene treatment downregulates the levels of AtETP1 and AtETP2 proteins, disrupting their interaction with AtEIN2, which facilitates the accumulation of AtEIN2. Overall, AtETP1/2 are negative regulators of ethylene signaling, preventing the activation of the ethylene signaling by degrading AtEIN2[32]. Similar to Arabidopsis, rice MHZ7/OsEIN2 is also proven to undergo proteasomal regulation, while the existence of AtETP1/2 homologs requires further investigation[58].

Although both phosphorylation and ubiquitination negatively regulate AtEIN2 function and are often mentioned together, whether these two different modifications affect each other remains unclear. In rice, the mhz3 mutant not only disrupts OsCTR2 kinase activity but also prevents OsEIN2 accumulation, suggesting that OsCTR2-mediated phosphorylation of OsEIN2 is not a direct cause of OsEIN2 degradation, implying a possible missing link between EIN2 phosphorylation and ubiquitination[58,59].

MHZ7/OsEIN2 and stabilizer MHZ3 in rice

-

In the rice genome, there are four EIN2 homologs, including OsEIN2.1 (MHZ7, Os07g06130), OsEIN2.2 (Os03g49400), OsEIN2.3 (Os07g06300), and OsEIN2.4 (Os07g06190)[61,115]. A single mutation in MHZ7/OsEIN2 results in ethylene insensitivity, and transcriptomic data also indicate that about 95% of ethylene-responsive genes depend on MHZ7/OsEIN2. These findings highlight the critical role of MHZ7/OsEIN2 in regulating the ethylene response in rice.

Like the Arabidopsis AtEIN2, the stability of the OsEIN2 protein in rice is also regulated by the 26S proteasome-mediated degradation system. MHZ3 was identified as a key stabilizer of OsEIN2, interacting with the Nramp-like domain of OsEIN2 through both its N- and C-terminal regions. This interaction is crucial for OsEIN2 accumulation, likely by shielding it from ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation, thereby ensuring its stability in the ethylene signaling pathway[58]. Short-term ethylene treatment enhances the association between OsEIN2 and MHZ3 without significantly affecting the MHZ3 protein levels, which may facilitate the rapid transmission of ethylene signals, also suggesting that MHZ3 might directly receive signals from the receptor complex[59] (Fig. 4). Simultaneous mutation of the two Arabidopsis MHZ3 homologs significantly reduces ethylene sensitivity, underscoring the potentially conserved role of MHZ3 homologs in regulating ethylene responses across species[58]. As mentioned earlier, in addition to stabilizing OsEIN2, MHZ3 also maintains the phosphorylation of OsCTR2 by synergizing with ethylene receptors. This suggests that MHZ3 plays a dual role in ethylene signaling, exhibiting both positive and negative regulatory activities within the pathway[59].

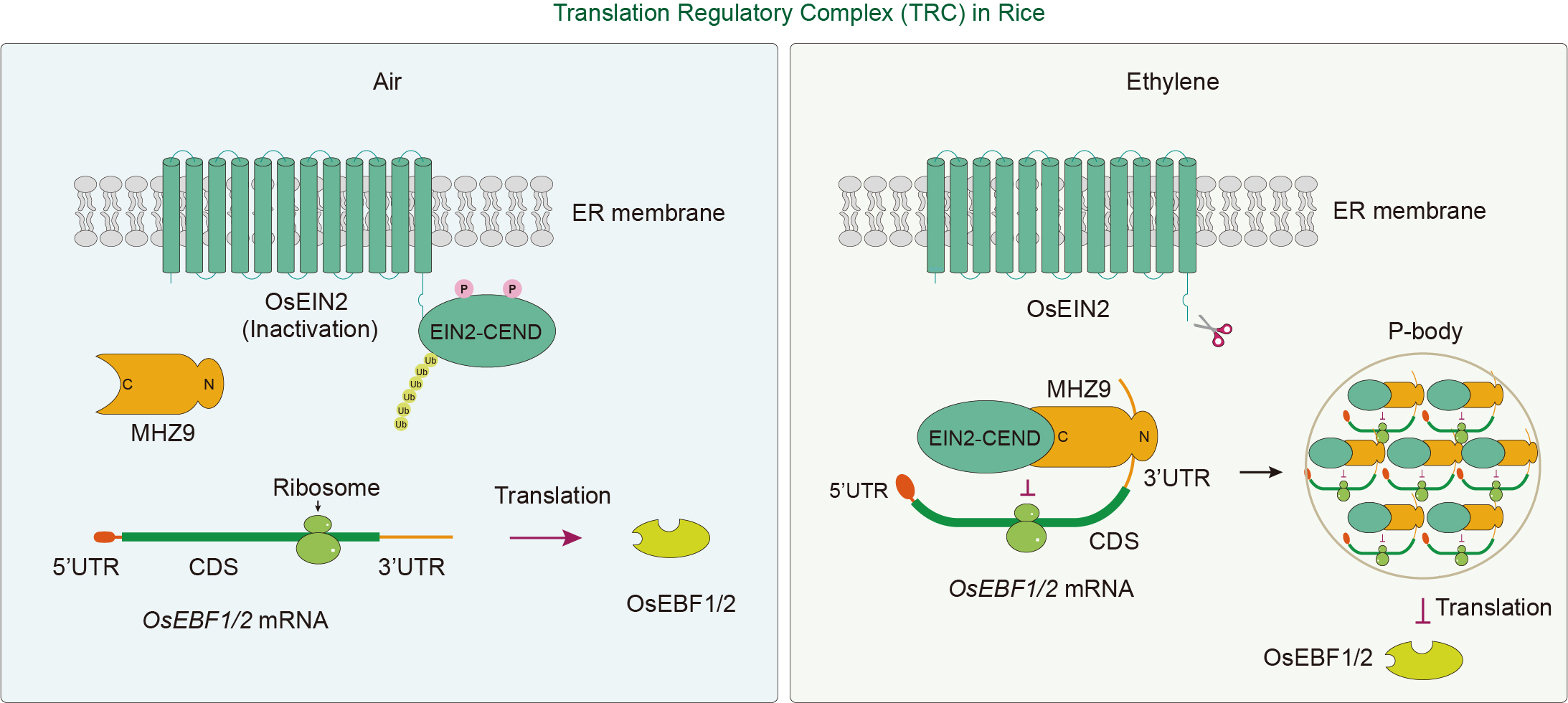

Figure 4.

Translation regulatory complex (TRC) in rice ethylene signaling. In the processing body (P-body), the C-terminal of OsEIN2 (EIN2-CEND), along with MHZ9, OsEBF1/2 mRNA, and other components, forms the TRC, which is involved in the translational inhibition of the ethylene signaling negative regulators, OsEBF1/2 proteins. In the absence of ethylene (left), MHZ9 binds OsEBF1/2 mRNA with low affinity, allowing normal translation and accumulation of the negative regulators OsEBF1 and OsEBF2, which deactivates the ethylene response. In the presence of ethylene (right), the C-terminal region of MHZ9 interacts with OsEIN2-CEND, facilitating the binding of its N-terminal region to the 3' UTR of OsEBF1/2 mRNA, leading to translational repression in the P-body. This prevents OsEBF1/2 accumulation and activates a nuclear ethylene signaling cascade. Dark red arrows indicate biological processes and black arrows indicate subcellular translocation. The 'T' blunt end indicates negative regulation.

EIN2-mediated signal output

-

In the presence of ethylene, the inhibitory effects of AtCTR1 and AtETP1/2 on AtEIN2 are relieved, allowing AtEIN2 to accumulate and transmit signals to the nucleus and P-body. The signal output mediated by AtEIN2 involves the production of active EIN2-CEND[36,39,40].

Upon ethylene exposure, EIN2-CEND is released from the ER membrane and migrates to the nucleus, where it interacts with EIN2 NUCLEAR-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 1 (ENAP1), promoting histone acetylation and enabling AtEIN3 to bind target DNA for transcriptional activation. ENAP1 also recruits histone deacetylases SRT1 and SRT2 to repress ethylene-downregulated genes by maintaining low H3K9Ac levels[33,34]. Phosphorylation of Ser645 in AtEIN2 is crucial for the cleavage of EIN2-CEND. AtEIN2S645A exhibits constitutive nuclear localization in leaf cells in the absence of ethylene, linking AtCTR1-mediated phosphorylation of AtEIN2 to the cleavage process[36]. To date, how ethylene regulates AtEIN2 cleavage and the components involved in this process remain unknown.

EIN2-CEND exhibits dual subcellular targeting, not only entering the nucleus but also localizing to the P-body, where it specifically binds to the 3' UTRs of AtEBF1 and AtEBF2 transcripts[36,38−40]. This binding leads to the degradation of these mRNAs by exoribonuclease 4 (XRN4, also known as AtEIN5), a well-characterized 5'-3' exoribonuclease that influences ethylene signaling[116,117]. The reduction of AtEBF1/2 leads to increased stability of the transcription factors AtEIN3 and AtEIL1 in the nucleus, thereby triggering an enhanced ethylene response[28,30]. Studies in rice have shown that EIN2-CEND can also localize to the P-body, where it performs similar functions[39]. This will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

-

Recent progress highlights the crucial role of post-transcriptional regulation, in particular, the regulation of mRNA stability and translation efficiency in the ethylene response[39,40,56]. Upon ethylene perception, a portion of EIN2-CEND released from the ER membrane enters the P-body, where it interacts with various components, including AtEIN5 and PABs in Arabidopsis, and the RNA-binding protein MHZ9 in rice[36,39,56,116]. These components play a key role in regulating mRNA translation. The proteins and mRNAs involved in regulating ethylene signal translation are referred to as the translation regulatory complex (TRC) (Fig. 4).

EIN2-mediated translational regulation

-

Studies show that upon activation, AtEIN2 not only transduces signals to the nucleus for transcriptional reprogramming but also participates in the translation regulation of AtEBF1/2 mRNA in the P-body[36,38−40]. AtEIN2 interacts with the 3' UTR of AtEBF1/2 mRNA through its EIN2-CEND domain, specifically with the PolyU motifs, targeting AtEBF1/2 mRNA to the P-body and thereby inhibiting its translation. EIN2-CEND is the key region mediating this translation repression function[39,40] (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the NLS (1262-1269 aa) motif plays a crucial role in its nuclear localization and function in the P-body. Deletion or mutation of the NLS region disrupts the translation repression activity of EIN2-CEND[39,110]. EIN2-CEND interacts with P-body components such as AtEIN5 and PABs, and this interaction depends on the presence of mRNA. Overexpression of the 3' UTR of AtEBF1/2 mRNA leads to reduced ethylene sensitivity, and the P-body component mutation showed an ethylene-insensitive phenotype. After ethylene treatment, the level of AtEBF1/2 mRNA increases, but its translation efficiency decreases. The interaction between EIN2-CEND and AtEBF1/2 mRNA is enhanced, promoting the colocalization of EIN2-CEND and AtEBF1/2 mRNA in the P-body[39,40]. This translation regulation mechanism allows EIN2-CEND to more effectively repress the translation of AtEBF1/2 mRNA in the presence of ethylene, thereby modulating the plant's response to ethylene. Rice EIN2-CEND can also interact with P-body components, suggesting the conservation of this mechanism across species[56] (Fig. 4).

MHZ9 mediates mRNA binding in translational regulation

-

EIN2 requires additional components for its translation suppression function. In rice, MHZ9, an RNA-binding protein containing a Gly-Tyr-Phe (GYF) domain, has been identified as a positive regulator of ethylene signaling. The N-terminal of MHZ9, which contains a PRP4 domain involved in RNA processing, directly binds the 3'UTR of OsEBF1/2 mRNA, mediating the ethylene-induced translational repression of these mRNAs. Its C-terminal, rich in glutamine, facilitates interaction with EIN2-CEND and determines its P-body localization. Overall, through its C-terminal, MHZ9 interacts with the EIN2-CEND to receive upstream ethylene signals, activating the RNA-binding activity of its N-terminal and mediating the translational repression of these mRNAs in response to ethylene[56] (Fig. 4). In Arabidopsis, RNA-binding proteins with functions similar to MHZ9 have not yet been identified. Additionally, whether EIN2-CEND can directly bind to the 3' UTRs of EBF1/2 mRNAs in the P-body in both rice and Arabidopsis requires further research.

-

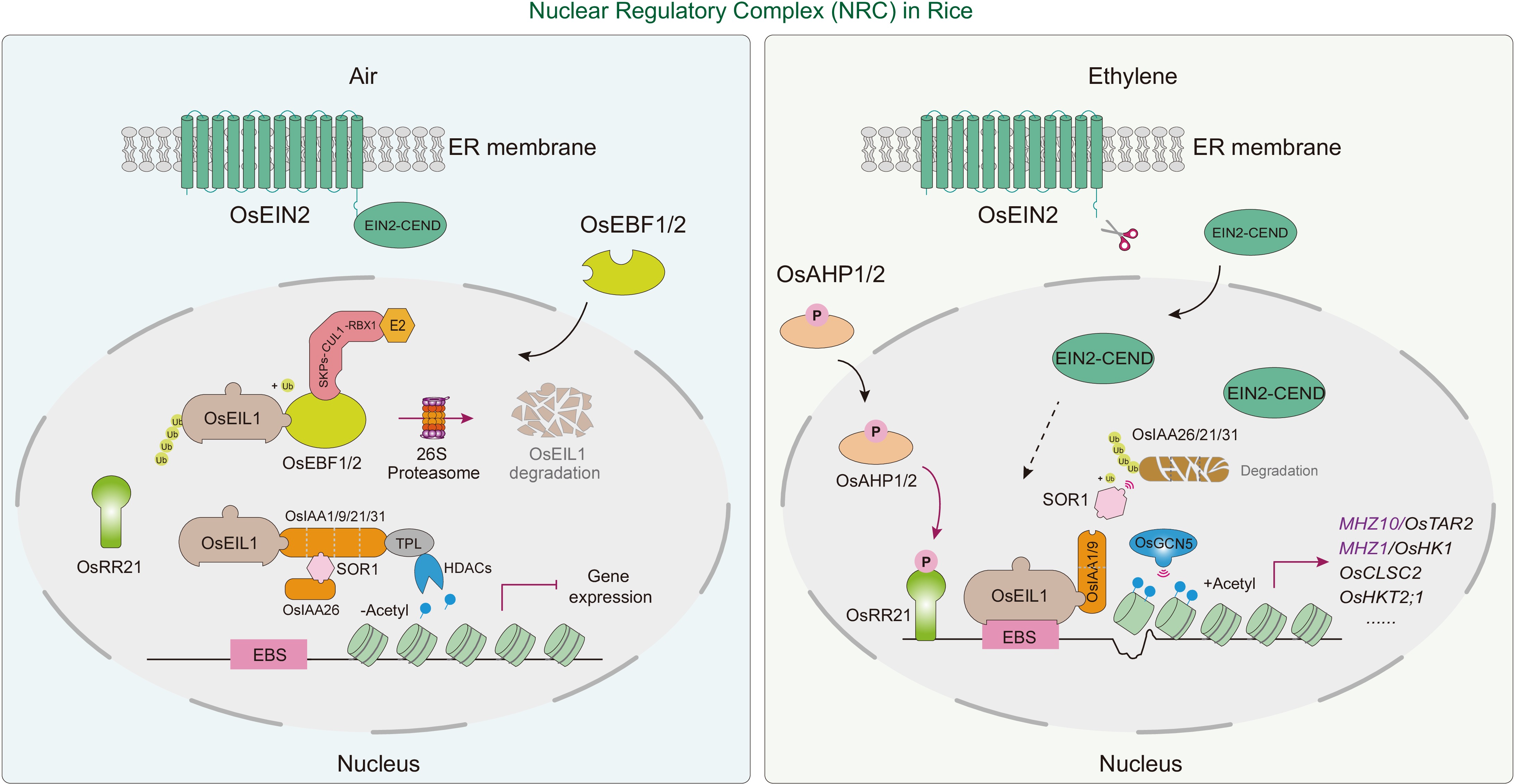

In the nucleus, Arabidopsis EIN2-CEND forms a complex with AtEIN3/EIL1 and nuclear factors to regulate histone acetylation, protein stability, and transcription. By promoting histone acetylation, it enhances AtEIN3/EIL1-mediated gene transcription. In both Arabidopsis and rice, EIN3/EIL1 proteins play crucial regulatory roles in ethylene signaling at the transcriptional level and integrate multiple hormonal pathways. The complex formed by EIN2-CEND, AtEIN3/EIL1, and OsEIL1/2, along with their interacting partners and DNA motifs involved in transcriptional regulation, is referred to as the nuclear regulatory complex (NRC) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Nuclear regulatory complex (NRC) in rice ethylene signaling. The core transcription factor OsEIL1 can recruit different interacting components to form a NRC, participating in the regulation of ethylene-responsive genes in rice. In the absence of ethylene (left), the F-box proteins OsEBF1 and OsEBF2 promote the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the OsEIL1 transcription factor, thereby inhibiting the activation of ethylene-responsive genes. Low levels of OsEIL1 may interact with auxin repressors OsIAA21 and OsIAA31, repressing downstream genes by recruiting co-repressor TOPLESS (TPL) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), leading to chromatin condensation. Additionally, OsIAA21 and OsIAA31 may attenuate the OsEIL1-OsIAA1/9 complex, maintaining basal biosynthetic processes for normal metabolic functions. In the presence of ethylene (right), OsEIN2-CEND transduces the ethylene signal to the nucleus, where OsIAA1/9 recruits the histone acetyltransferase OsGCN5 to mediate histone acetylation and chromatin decondensation. OsIAA1/9 interacts with OsEIL1, thereby activating the expression of downstream genes. OsEIL1 directly binds to the promoters of MHZ10/OsTAR2, MHZ1/OsHK1, OsCLSC2, OsHKT2;1, and others, playing a role in regulating various biological processes. The response regulator OsRR21, receiving phosphoryl groups from the MHZ1-OsAHP1/2 phospho-relay, activates and amplifies the ethylene signal. Red arrows indicate activation and/or biological process and black arrows indicate subcellular translocation. The 'T' blunt end indicates negative regulation.

EIN2-CEND-mediated chromatin remodeling in the nucleus

-

In the nucleus, EIN2-CEND participates in histone acetylation regulation[36]. Studies have shown that ethylene enhances H3K14 and non-canonical H3K23 acetylation in Arabidopsis etiolated seedlings in an AtEIN2-dependent manner[33]. ENAP1, a positive ethylene response regulator, interacts with EIN2-CEND and histone H3, increasing acetylation at H3K14 and H3K23. This interaction facilitates AtEIN3 binding to target genes and activates ethylene-responsive gene expression. Conversely, ethylene represses gene transcription by down-regulating H3K9Ac, with histone deacetylases SRT1 and SRT2 interacting with ENAP1 to reduce H3K9Ac levels at repressed gene promoters[33,34] (Fig. 1).

Recent studies have found that ethylene induces the translocation of the PYRUVATE DEHYDROGENASE COMPLEX (PDC) from the mitochondria to the nucleus. PDC mutations can lead to reduced histone acetylation and transcriptional activation, resulting in decreased ethylene sensitivity. Ethylene-induced nuclear translocation of PDC retains its enzymatic activity, and in the nucleus, PDC interacts with EIN2-CEND to synthesize nuclear acetyl-CoA, which is used for histone acetylation, particularly at H3K14 and H3K23 (Fig. 1). This process is crucial for the function of EIN2-CEND in histone acetylation regulation[35].

In summary, when Arabidopsis AtEIN3/EIL1 binds to gene promoters, EIN2-CEND in the nucleus recruits various chromatin remodeling factors to modulate the acetylation levels of histone H3, thereby regulating the activation or repression of ethylene-responsive genes[33,34]. EIN2-CEND appears to serve as a core scaffold, linking the PDC, which provides acetyl-CoA, with ENAP1, which regulates histone H3 acetylation[35]. Whether acetyltransferases exist to add acetyl groups to lysine residues on histones, thereby further regulating gene transcription, remains to be investigated. Additionally, the epigenetic regulatory mechanisms involving EIN2-CEND in the nucleus in rice and other plants remain unknown.

Regulation of EIN3/EIL protein stability

-

In Arabidopsis, AtEIN3 and its homolog AtEIL1 are key transcription factors in the ethylene signaling pathway. AtEIN3/EIL1 receives upstream signals transmitted by STC and TRC, triggering the transcriptional reprogramming of ethylene-responsive genes, thereby activating and amplifying the ethylene signaling[36,39,40]. The stability of AtEIN3 is regulated by two EIN3-interacting F-box proteins, AtEBF1 and AtEBF2. In the absence of ethylene, AtEIN3/EIL1 proteins are targeted by AtEBF1/2 for degradation by the 26S proteasome. When ethylene is presented, AtEBF1/2 protein abundance is reduced due to translational inhibition, leading to the stabilization and accumulation of AtEIN3/EIL proteins[28−30]. Recent studies have found that ethylene-induced nuclear-localized AtCTR1 interacts with AtEBF1/2, thereby promoting AtEIN3/EIL1 accumulation[41]. However, the regulatory mechanism of this process remains unknown. Additionally, AtEBF1/2 proteins are subject to 26S proteasome-mediated degradation in response to ethylene and various stress signals[118]. Hao et al. identified the RING-type E3 ligase SDIR1, which positively regulates the ethylene response by promoting AtEIN3 accumulation. SDIR1 interacts with AtEBF1/EBF2, targeting them for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, and mediates temperature-induced degradation of AtEBF1/2 to regulate ethylene responses to temperature changes[119].

In rice, MHZ6/OsEIL1 and OsEIL2 are homologous to Arabidopsis AtEIN3/EIL1. The OsEIL1 loss-of-function mutant and OsEIL2 RNA interference (RNAi) lines exhibit spatially specific ethylene insensitivity in their roots and coleoptiles, respectively[47,53]. Similar to AtEBF1/2 in Arabidopsis, OsEBF1/2 proteins act as negative regulators of ethylene signaling, with loss-of-function leading to constitutive ethylene responses, while overexpression results in reduced ethylene sensitivity[56]. Additionally, similar SlEBFs proteins in tomato also regulate ethylene signaling by promoting the degradation of SlEILs proteins. This regulatory mechanism is highly conserved across different species[3,120,121].

EIN3/EIL1-mediated transcriptional regulation and signal crosstalk

-

Both Arabidopsis AtEIN3 and AtEIL1 accumulate to form homodimers, which efficiently regulate the expression of downstream genes, such as AtERF1 and other AtERFs in the AP2 family of transcription factors, by binding to the EIN3 BINDING SITE (EBS) in the promoters of target genes via their DNA-binding domain. AtERFs, in turn, bind to GCC box elements in the promoters of other ethylene-responsive genes[122,123]. Chang et al. found that AtEIN3 directly binds to over a thousand genes, including most components of the ethylene signaling pathway, such as AtEBF2[124]. This finding suggests that feedback regulation is a common feature of ethylene signal transduction. AtEIN3 is also a crucial regulatory node in plant growth, development, and stress response processes[125,126]. It integrates most plant hormone and stress signaling pathways into a complex transcriptional regulatory network[124]. In Arabidopsis, AtEIN3/EIL1 are known to participate in the crosstalk between various signals, including light, temperature, nutrients, pathogens, GA, JA, BR, ABA, SA, and auxin, through both transcriptional regulation and direct protein interactions[2,61,123]. This regulation involving AtEIN3/EIL1 in Arabidopsis has been extensively reviewed[123], and we will focus on the biological processes regulated by NRC in rice.

MHZ6/OsEIL1 and OsEIL2 play diverse roles in regulating rice growth, development, and adaptation. OsEIL1/2 negatively regulates rice salt tolerance by directly binding to the promoter of OsHKT2;1, promoting its expression in the root system and increasing Na+ absorption[53]. This contrasts with the positive regulatory role of AtEIN3 and AtEIL1 in Arabidopsis salt tolerance[127] Ethylene regulates rice grain size by inducing OsERF115 expression. OsEIL1 directly binds to the OsERF115 promoter, activating its transcription and positively influencing grain size and weight[128]. OsLOX9 in rice is crucial for JA synthesis induced by the brown planthopper (BPH), and OsEIL1 negatively regulates BPH resistance by inhibiting OsLOX9 expression, revealing a cross-regulation between ethylene and JA signaling[129]. OsEIL1/2 binds to the promoters of OsVTC1-3 and PRX genes, enhancing their expression, reducing ROS levels in the coleoptile, and promoting growth and seedling emergence[130]. OsEIL1 also directly activates OsWOX11, which is involved in crown root formation and growth[131]. Furthermore, OsEIL1 amplifies ethylene signaling by activating MHZ1/OsHK1 expression, forming a positive feedback loop that also suggests crosstalk with cytokinin signaling[50,132]. In contrast, OsEIL2 represses GY1 expression and reduces JA levels, promoting mesocotyl and coleoptile elongation to facilitate seedling emergence[133]. In addition, the OsEILs family proteins also widely participate in various biological processes by regulating the expression of other downstream genes.

In rice, OsEIL1 serves as a key convergence point for the crosstalk between ethylene and auxin, regulating root elongation and gravitropism. A study on an ethylene-insensitive mutant in rice roots found that MHZ10 encodes TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE RELATED 2 (OsTAR2), involved in auxin synthesis. Under normal conditions, OsEIL1 interacts with OsIAA21/31, inhibiting MHZ10/OsTAR2 activation and suppressing the OsEIL1-OsIAA1/9 complex, ensuring normal root growth. However, when ethylene levels rise, OsEIL1 accumulates, OsIAA21/31 is degraded, and OsEIL1-OsIAA1/9 complexes are activated. OsIAA1/9 recruits OsGCN5 to enhance histone acetylation, promote MHZ10/OsTAR2 transcription, and increase auxin synthesis, thereby inhibiting root growth[62]. Previous studies have shown that IAA9 regulates auxin signaling. In the absence of ethylene or auxin, OsIAA9 inhibits the E3 ligase activity of MHZ2/OsSOR1, stabilizing OsIAA26. When ethylene or auxin is present, TIR1/AFB2 binds to OsIAA9, promoting its degradation and releasing OsSOR1 to degrade OsIAA26, inhibiting root elongation. These findings suggest that OsEIL1 regulates auxin synthesis and signaling at both the transcriptional and protein levels through its association with OsIAAs[57]. In addition to MHZ10/OsTAR2, mutations in MHZ8/PIN2, involved in auxin transport, and YUCCA (OsYUC8/REIN7), involved in auxin synthesis, also reduce the root response to ethylene in rice. OsEIL1 directly activates the expression of YUC8/REIN7[61,134] (Fig. 5). Together, these findings suggest that ethylene regulates root growth in rice by modulating auxin signaling.

OsEIL1 is also involved in regulating the synthesis and metabolism of GA at the transcriptional level and is involved in the control of mesocotyl and root elongation in rice[135,136]. Mechanical pressure from soil covering triggers ethylene release, leading to OsEIL1 accumulation. OsEIL1 binds to the SD1 promoter, promoting GA synthesis and enhancing mesocotyl elongation[135]. Ethylene also activates GA metabolism genes (OsGA2ox1, OsGA2ox2, OsGA2ox3, and OsGA2ox5), reducing active GA content, inhibiting root meristem cell proliferation, and suppressing primary root growth[136]. How ethylene precisely regulates the synthesis and metabolism of GA to adapt to changing environmental conditions requires further investigation.

OsEIL1/2 potentially regulates ABA synthesis, affecting root and coleoptile elongation in rice. MHZ4 encodes a protein homologous to the Arabidopsis ABA4, which is involved in ABA biosynthesis. MHZ5 encodes an enzyme, CRTISO, involved in carotenoid biosynthesis. Loss-of-function mutations in MHZ4 and MHZ5 exhibit ethylene-insensitive root growth and ethylene-hypersensitive coleoptile elongation[52,60]. Ethylene may regulate the expression of MHZ4 and MHZ5 through the activation of OsEIL1/2, leading to ABA accumulation and inhibition of root growth[136] (Fig. 1). These results suggest that ABA is required for ethylene-induced root growth inhibition, while it counteracts the effects of ethylene in promoting coleoptile elongation. In Arabidopsis, ethylene inhibition of root growth is downstream of ABA, indicating that rice has evolved a unique ethylene signaling mechanism.

-

Research on ethylene signaling transduction in plants, including Arabidopsis, rice, tomato, and others, has provided valuable insights into the dynamic regulation of signaling complexes. However, significant knowledge gaps remain in understanding the molecular mechanisms of this crucial pathway. The precise mechanism of ethylene receptor signaling output, particularly how receptors regulate AtCTR1 and OsCTR2 based on ethylene binding, remains unclear. A phosphatase dephosphorylating OsCTR2 may exist and require further identification. In Arabidopsis, ethylene signaling displays distinct modes under dark and light conditions, particularly at the level of EIN3[137]. It however remains largely unknown whether rice utilizes a comparable regulatory mechanism.

EIN2 emerges as a bridge/shuttle factor in ethylene signaling, mediating signal transmission between the ER membrane, P-body, and nucleus[36,38−40]. Critical unresolved areas include the specific impact of EIN2 phosphorylation sites on its cleavage and activation, the role of components involved in EIN2 processing, and the functional significance of EIN2's N-terminal domain[36,37,58]. The potential mechanisms of how MHZ3 stabilizes OsEIN2 through N-terminal domain interactions could be further explored.

The complexity of ethylene signaling extends to its interactions with other hormonal pathways. While current research has explored crosstalk at protein interaction and transcriptional regulation levels, the mechanisms of translational regulation remain largely unexplored. In this point, rice MHZ9 and/or its homologs in other plants may be worthy of further investigation and could be a node for multiple connections[56]. It is also crucial to understand the transcriptional regulatory networks under specific environments, which is important for developing more precise control of ethylene signaling, with potential applications in crop and horticultural production.

Technological advances in structural biology, especially cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) now provide unprecedented opportunities to investigate the structural basis of the ethylene signaling complexes discussed in this review. By integrating protein-protein interaction networks, targeted sequencing, and classical genetic screening methods, researchers can uncover and validate new regulatory factors. In addition, the Multi-Knock approach is used to overcome the redundancy in plant forward genetic screening[138], or to screen germplasm materials with natural variation in abnormal ethylene response, identify relevant genes, and elucidate their mechanism of action, which may provide new insights into ethylene signaling regulation. These innovative approaches promise a more comprehensive understanding of the ethylene signaling pathway, offering a robust theoretical foundation for future biological applications.

This work is supported by the STI 2030-Major Projects (2023ZD0407102, 2023ZD0406801), and the CAS Strategic Priority Research Program (XDB1090101).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation, figure preparation: Li XK; study conception and design, manuscript revision: Li XK, Yin CC, Tao JJ, Zhao H, Chen YC, Zhang JS. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li XK, Yin CC, Tao JJ, Chen SY, Zhao H, et al. 2025. Ethylene signaling in rice and Arabidopsis: from the perspective of protein complexes. Plant Hormones 1: e009 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0009

Ethylene signaling in rice and Arabidopsis: from the perspective of protein complexes

- Received: 18 February 2025

- Revised: 27 March 2025

- Accepted: 17 April 2025

- Published online: 16 May 2025

Abstract: Ethylene, a potent gaseous hormone, regulates crucial processes in plant growth, development, and environmental adaptation. Over the past three decades, the ethylene signaling pathway has been elucidated in the dicot model plant Arabidopsis, tracing the signal cascade from receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane to transcription factors in the nucleus. Rice, a monocot adapted to semi-aquatic environments, shares core elements of this pathway but also displays unique regulatory mechanisms reflecting its ecological adaptations. Studies on ethylene signaling in rice have added more insight into the dynamic regulation of this pathway. This review summarizes recent advances in ethylene signaling in rice and Arabidopsis, highlighting how multiple protein complexes orchestrate a sophisticated regulatory network spanning ligand perception, signal transduction, translational regulation, and nuclear signal amplification, thereby ensuring precise and coordinated hormonal responses.

-

Key words:

- Ethylene signaling /

- Rice /

- Arabidopsis /

- Protein complexes