-

Fresh fruits are an essential part of the human diet and are abundant sources of vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, and other health-promoting compounds. Fruit ripening involves several changes in fruit shape, color, quality, flavor, and others, and is influenced by a mass of plant hormones, including ET, ABA, auxin, GA, CK, JA, SA, and BR[1]. Fleshy fruits can be categorized into climacteric fruits (such as apple, apricot, avocado, banana, tomato, etc.) and non-climacteric fruits (i.e. citrus, grape, orange, lemon, raspberry, strawberry, etc.) based on the features of respiration and ET production during fruit ripening[2]. Climactic fruits exhibit a clear peak in respiration at the start of ripening together with bursts of ET production. In contrast, the latter do not exhibit such significant bursts of respiration and ET production[2]. ET is regarded as the major hormone controlling climacteric fruit ripening and other hormones, most notably ABA, are also believed to be involved in the regulation of fruit ripening[3]. Numerous studies have also demonstrated that ABA, along with the combined effects of other hormones including ET, Auxin, SA, and BR, plays an important role in the maturation of non-climacteric fruits[4].

A great deal of progress has been made recently in understanding the molecular basis of hormonal regulation of fruit ripening[5]. However, the molecular basis of hormonal crosstalk among various hormones is still largely unknown. In addition to having biological significance for understanding fruit ripening, a thorough understanding of the network of interactions between plant hormones is crucial commercially for reducing postharvest losses and enhancing shelf life. In this review, we evaluated the molecular interactions between several plant hormones during fruit ripening, concentrating on hormone interactions with direct molecular evidence. The purpose of the work is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the molecular interactions between hormones, which also presents a few crucial phytohormone junctions that will further our understanding of these interactions.

-

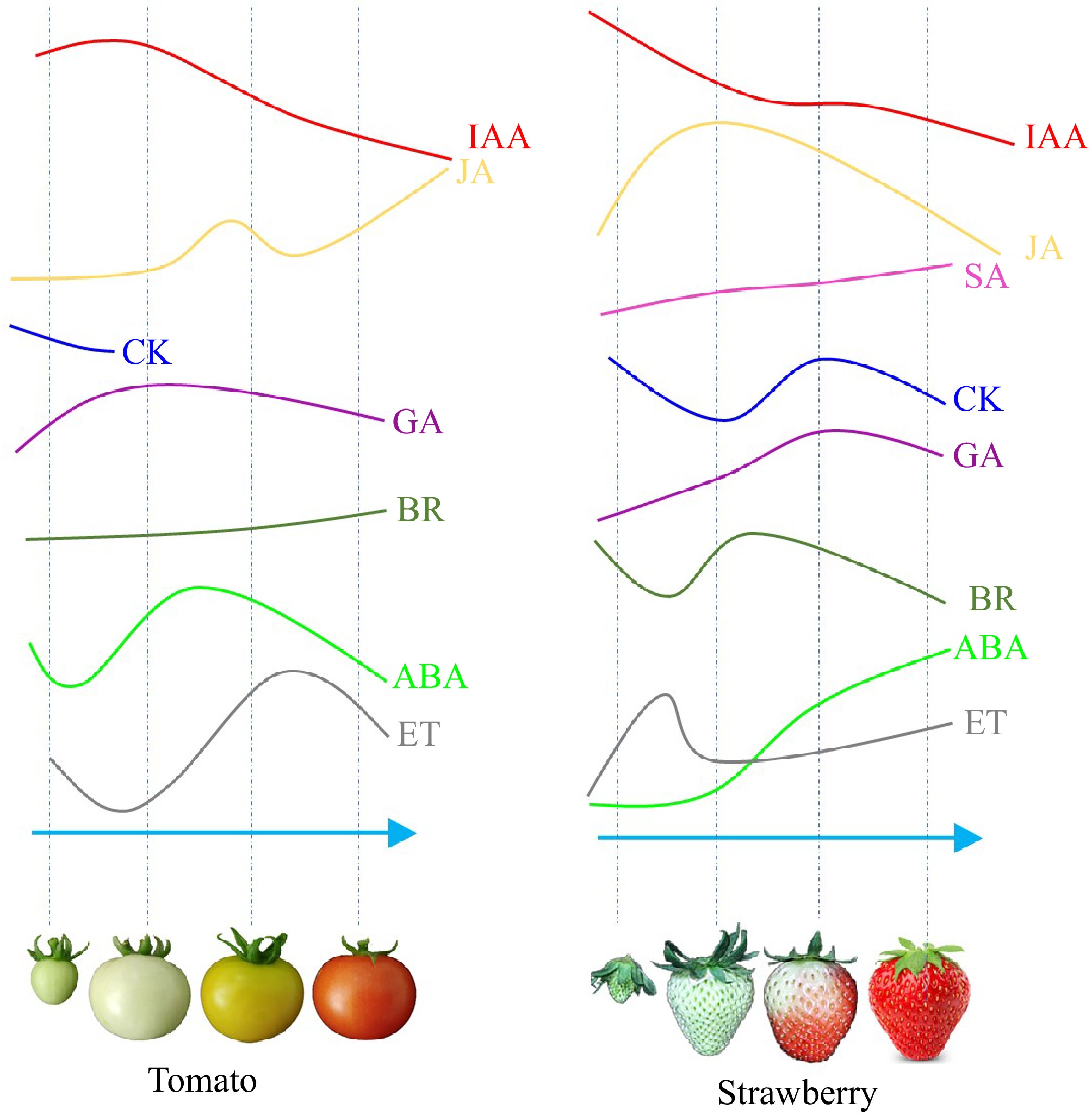

Phytohormones are essential to the ongoing process of fruit development and ripening. It is generally considered that auxin, CK, and GA are the key hormones during fruit morphogenesis and development of both climacteric and non-climacteric fruits, while ABA and ET are key for fruit ripening. The variation of their content in the fruit also confirms their function, the primary hormones that influence the ripening of climacteric and non-climacteric fruits are different, and their contents vary at different stages of fruit ripening[1,3]. Figure 1 depicts a model diagram illustrating the variations in plant hormone content during tomato and strawberry fruit ripening. When the tomato fruit development is complete but before it changes color, the concentrations of ABA and JA increase, and this is when the ET content reaches its peak (Fig. 1). ABA, JA, and SA concentrations all increase as the strawberry pseudocarp turns red, while the ET content of the strawberry fluctuates significantly during fruit development but it doesn't change much during ripening (Fig. 1). IAA, CK, and GA were significantly decreased after color of the two types of fruits were broken, while BR changes inconsistently during development and ripening in both types[3]. In addition to ABA and ET, other hormones also play an important role in controlling fruit ripening, and some of them have favorable effects while others have negative ones, according to variations in hormone content during fruit ripening[5,6].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of endogenous ET, ABA, IAA, GA, CK, JA, SA, and BR contents in tomato and strawberry during fruit development and ripening. Different coloured lines represent different types of hormones. The horizontal axis represents different developmental stages of tomato and strawberry, while the vertical axis represents the relative contents of the hormones[3,7].

-

In climacteric fruit, ET is a key regulator for fruit ripening, and the application of ABA can significantly accelerate ET biosynthesis[7]. The ABA treatment in tomato led to earlier peaks in both ABA and ET production, demonstrating both its influence on ET production and its contribution to climacteric fruit ripening[8]. Exogenous ABA can hasten fruit coloring by directly acting on genes associated with fruit coloring or by using the ET pathway[8]. The crosstalk between ABA and ET during fruit ripening is quite intricate. ABA signaling may be located upstream of ET signaling in regulating fruit ripening[9]. Although endogenous ABA and ET levels start to rise after tomato green ripening, ABA levels peak before ET production[10]. The self-inhibitory process (systems I) and the autocatalytic process (systems II) are the two different pathways of ET production during fruit ripening in climacteric fruits. Exogenous ABA in system I increased basal ET production via increasing the expression of SAM gene[11]. However, the regulatory action of ABA may take a backseat after fruit ripening as it is anticipated to have a more significant role in causing ET to flip from autoinhibitory to autocatalytic[8].

Is ABA an inducer of ET synthesis?

-

Extensive research has meticulously elucidated the mechanisms by which ABA induces ET biosynthesis and signal transduction in climacteric fruit. Genes participating in ABA biosynthetic or signal transduction pathways play an important role in modulating ET production: their overexpression or silencing can either enhance or attenuate this process. This has been convincingly demonstrated in tomato plants.

Inhibition of NCED1, a key gene in ABA biosynthesis, leads to a marked reduction in endogenous ET levels, accompanied by impaired ET signal transduction—findings that strongly corroborate the stimulatory role of endogenous ABA in ET production[12]. Conversely, overexpression of the ABA receptor gene SlPYL9 accelerates fruit ripening and promotes ET biosynthesis[13]. Co-silencing of ABA receptors (SlRCAR9, SlRCAR11, SlRCAR12, and SlRCAR13) dampens both ET biosynthesis and signaling, thereby delaying fruit ripening[9]. Additionally, suppression of SlPP2C1 and SlPP2C5 enhances ET release in fruits, establishing a critical regulatory node that accelerates ripening processes[14]. The ABA-responsive transcription factor SlAREB1 upregulates the expression of SlACS2, SlACS4, and SlACO1—key genes in ET biosynthesis—thereby driving ET production and fruit ripening[15].

A proposed model suggests that ABA signaling acts upstream of ET signaling in regulating fruit ripening: inhibiting ABA signaling can cause a delay in fruit ripening, yet exogenous ET application can rescue this phenotype. These studies confirm that ABA acts as an upstream regulator of ET, yet the precise molecular interactions and downstream effectors mediating their signaling cross-talk remain unclear, highlighting critical gaps for mechanistic exploration. Future research could first dissect direct physical interactions between ABA signaling components and ET pathway factors, as well as how ABA modifies ET signaling via post-translational mechanisms like phosphorylation. Moreover, identifying ABA-responsive genes controlling ET biosynthesis/signal transduction and characterizing their transcriptional/epigenetic regulation will clarify downstream regulatory nodes.

Are NAC TFs the bridge in ET-ABA crosstalk?

-

NAC TFs primarily regulate tomato fruit ripening through ET- and ABA-dependent pathways, both in climacteric and non-climacteric fruits[16].

In tomato, SlNCED1 and SlNCED2 positively modulate ABA and ET biosynthesis, as well as fruit ripening[7]. Overexpression of SlNAC1 upregulates SlNCED1 and SlNCED2, while silencing of SlNAC4 reduced the expression of these genes[17,18]. Conversely, silencing of SlNAC9 increased SlNCED1/SlNCED2 expression, suppressed ABA biosynthesis, and delayed fruit ripening[17]. Notably, SlNAC4 enhances ABA signaling by transcriptionally activating SAPK3—a gene encoding a key enzyme in ABA catabolism—and repressing SlCYP707A1, a critical component of ABA signal transduction[19]. SlNAC4 interacts with SlACS2 and SlACO1 and directly binds to the promoters of SlACS8 and SlACO6, thereby upregulating their expression and accelerating ET production[19]. SlNAC9 directly controls ABA signaling by transcriptionally activating SlAREB1, a downstream TF in the ABA signaling pathway[19]. Meanwhile, SlNAC9 directly controls ABA signaling by activating SlAREB1, a downstream TF in the ABA pathway[19]. These factors likely serve as critical bridges between ET and ABA signaling, as shown in Fig. 2.

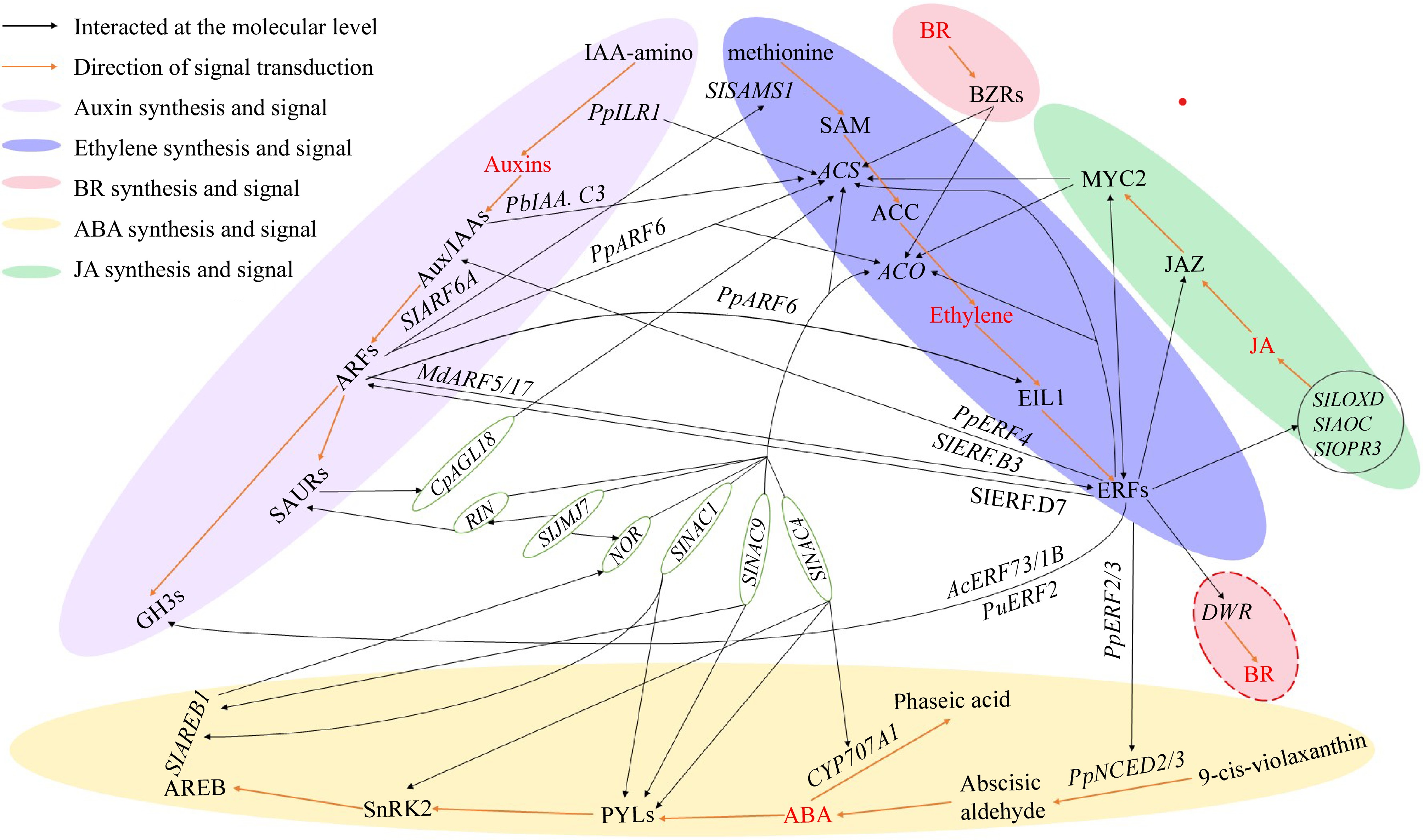

Figure 2.

The molecular crosstalk among ABA, ET, auxin, BR, and JA. The red-colored text represents the five hormones including Auxins, ABA, BR, Ethylene, and JA. The red line represents the hormone synthesis and signal transduction pathway. The black lines represent genes or proteins that have direct interaction relationships which have been confirmed through various experiments including yeast one-hybrid, yeast two-hybrid, EMSA, etc. IAA-amino: indole-3-acetic acid-amino acid; PpILR1: IAA-amino hydrolase gene 1 in peach; Aux/IAAs: auxin/indole-3-acetic acid protein family; SAURs: small Auxin-Up RNAs; GH3s: auxin responsive GH3 gene family; ARFs: auxin response factors; SlSAMS1: S-adenosylmethionine synthetase gene; SAM: S-adenosyl-L-methionine; ACS: 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase gene; ACC: 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid; ACO: aminocyclopropanecarboxylate oxidase gene; EIL1: ethylene-insensitive protein; ERFs: ethylene-responsive transcription factors; DWF: steroid 22S-hydroxylase gene, the key for BR biosynthesis; BR: brassinosteroid; MYC2: a basic/helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein response to JA; JAZ: jasmonate ZIM domain-containing protein; JA: Jasmonic acid; SlLOXD: lipoxygenase gene of tomato; SlAOC: allene oxide cyclase gene of tomato; SlOPR3: 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase gene of tomato; PpNCED2/3: 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene 2/3 in peach; ABA: abscisic acid; CYP707A1: abscisic acid 8'-hydroxylase; PYL: abscisic acid receptor PYR/PYL family; SnRK2: serine/threonine-protein kinase SnRK2: SNF1-related kinase 2; AREB: abscisic acid response element-binding factor; SlNAC1/4/9: NAC transcription factors in tomato; NOR/RIN: two key transcription factor regulating fruit ripening in tomatoes; SlJMJ7: Jumonji C domain-containing protein gene in tomato, an eraser of histone methylation; CpAGL18: a MADS transcription factor in papaya.

NOR acts as a pivotal upstream positive regulator of ET biosynthesis genes[16]. The NOR-like TF NOR-like1, whose knockout mutant exhibits reduced ET production, positively influences tomato fruit ripening[20]. Intriguingly, SlAREB1—a downstream TF in the ABA pathway—transcriptionally activates NOR, which functions upstream of RIN in the ripening regulatory hierarchy[15]. This suggests that SlAREB1 indirectly modulates RIN and ET biosynthesis genes via the NOR gene. NOR gene is likely to be a key factor among NAC TFs in mediating ABA and ET signaling.

Additionally, in other climacteric fruits, studies have reported that NAC TFs function as key intermediaries in mediating ABA-ET crosstalk[16]. However, clear molecular interaction evidence remains limited, with few reports demonstrating direct mechanistic links between the two pathways. In non-climacteric species like strawberries and citrus, NACs are also implicated in ABA-ET signaling crosstalk[16], though the underlying molecular connections remain unclear. A notable example comes from grapes, where VvNAC26 interacts with VvMADS9 to upregulate genes involved in both ET and ABA biosynthesis, driving early fruit ripening[21]. Yet current evidence of such interactions still focuses on individual hormone pathways (ABA or ET), failing to establish a unified regulatory framework that integrates both signals. Further research is needed to characterize the precise molecular interactions that bridge ABA and ET through NACs, particularly how these factors coordinate cross-pathway signaling during fruit ripening. Collectively, these findings support a model where NAC TFs serve as central mediators of ABA-ET interactions, highlighting their critical role in orchestrating hormonal networks that govern fruit maturation.

Other TFs in ET-ABA cross-talk

-

The interplay of ABA and ET during fruit ripening may also be mediated by additional TFs, including MADS, bHLH, C2H2, and other families. Most of the experiments with conclusive evidence of molecular interactions are from climacteric fruits. In tomato, SlZFP2 (C2H2 family) regulates ABA biosynthesis during fruit development by directly repressing ABA biosynthesis genes; it also controls fruit ripening through transcriptional repression of CNR and further inhibition/activation of ET biosynthesis[10,11]. Besides, SlbHLH22 regulates ET-mediated fruit ripening and carotenoid accumulation, whereas exogenous ABA increases bHLH22 expression[22]. In tomato, although some studies have shown that other TFs are involved in ABA-ET crosstalk, currently, there are still relatively few TFs for which the molecular interaction networks between TFs and ABA as well as between TFs and ET have been established. In apples, AREB/ABF binding sites identified in the upstream regions of MdACS1/3 and MdACO1 imply direct regulation of ET synthesis genes by AREB family members[23]. Moreover, exogenous ABA and ABA inhibitors alter MADS-RIN expression, which may be an essential node of the ABA-ET relationship[8]. In plums, ABA insensitive 5 (ABI5) can bind to the promoter area of ACS1 to activate ET biosynthesis, indicating that ABI5 may be a major factor by which ABA influences ET biosynthesis[24]. These TFs, serving as intermediate bridges, are highly likely to be crucial mediators connecting ABA and ET, and require further research.

Epigenetic modification in ET-ABA cross-talk

-

During fruit ripening, epigenetic modifications—particularly DNA methylation—play a pivotal regulatory role by coordinating the synthesis and signaling of ABA and ET. The DNA demethylase SlDML2 serves as a central mediator in this process, with its activity being dually regulated by ABA and ET: exogenous ABA and ET treatments significantly induce DML2 expression in green fruits, while DML2-mediated DNA hypomethylation activates transcription of ABA biosynthesis genes (e.g., NCEDs), forming a positive feedback loop[25,26]. Concurrently, DML2 modulates the methylation status of ET biosynthesis-related and signaling-related genes, thereby influencing the ET pathway. This dual regulatory mechanism is validated in DML2-RNAi lines, where hypermethylation in the promoter regions of key genes (e.g., ACS2, ACO1) disrupts ABA and ET synthesis[25,27].

Histone modifications synergize with DNA methylation to regulate ABA-ET crosstalk. The H3K4me3 demethylase SlJMJ7 suppresses DML2 transcription by reducing H3K4me3 levels at its promoter, while directly modulating methylation of ET biosynthesis genes[28]. Notably, homologs of SlJMJ7 in Arabidopsis bind to the promoter of ABI5, a core ABA signaling factor, suggesting cross-species conservation in ABA-ET integration[29]. This epigenetic cascade is amplified in nor, rin, and cnr mutants, where DML2 expression is markedly downregulated and its promoter exhibits hypermethylation, positioning DML2 as a feedback target downstream of ripening inhibitors (e.g., RIN/NOR)[27]. Furthermore, bidirectional interplay exists between DNA methylation dynamics and hormone signaling: ABA activates DML2 via the PYL-PP2C-SnRK2 module, while DML2-mediated demethylation promotes expression of ethylene-responsive factors (e.g., ERFs), ultimately enabling epigenetic reprogramming to harmonize multi-hormone networks during ripening[30].

Although the roles of DNA methylation and histone modification in fruit ripening have been well-established, there is still a lack of critical molecular evidence regarding how they participate in the crosstalk between ABA and ET. Future studies should focus on identifying shared epigenetic regulators that directly bridge ABA and ET signaling, such as chromatin remodelers or DNA/RNA methylation enzymes with dual roles in hormone pathways.

Can ABA be activated by ET?

-

On the other hand, ABA biosynthesis and signaling can also be impacted by ET and ET-related cues. This situation exists in both climacteric and non-climacteric fruits. In non-climacteric fruits such as strawberries, exogenous ET encourages ABA accumulation in the receptacle tissue of postharvest strawberry fruit[31]. In grape, minute quantities of endogenous ET trigger VvNCED1 transcription, which in turn triggers ABA biosynthesis[32]. In non-climacteric fruits, further research has revealed that PpERF2/3 can interact with PpNCED2/3 to affect ABA biosynthesis during fruit ripening, but their functions are opposite in Pyrus pyrifolia[33,34]. In tomato, ERF family transcription factor SlPti4-RNAi interference reduced ET content in fruit but increased NCED1 transcription and ABA synthesis[35]. It is likely that the AP2/ERF transcription factor has a significant impact on the complicated, potentially positive or negative, interactions between ET and ABA during fruit ripening. During fruit maturation, the EBF1 protein in bananas can interact with ABI5 and increase the transcriptional activity of genes involved in starch and cell wall degradation[36].

In some plants, ET induces the production of ABA. However, more direct evidence of molecular interactions regarding this induction mechanism is still lacking. This has positive significance for the postharvest ripening promotion of non-climacteric fruits.

Other factors in ET-ABA cross-talk

-

Small RNAs may also play a role in ethylene-induced ABA biosynthesis[37]. In strawberry fruits, miR161 negatively regulates the biosynthesis of ABA by suppressing the expression of FaNCED1. Meanwhile, ET promotes the biosynthesis of ABA by inhibiting the expression of miR161 in fruits, thereby affecting fruit ripening[38].

Calmodulin-like proteins also participate in ABA-ET cross-talk during the fruit ripening process. CML15 interacts with PP2C46/65 and plays a significant role in the ABA and ET signaling pathways, thereby regulating the fruit ripening process[39].

Current research indicates that ABA and ET collaboratively regulate fruit ripening through intricate crosstalk mechanisms. ABA plays a pivotal role in both climacteric and non-climacteric fruits, with its accumulation typically preceding ethylene. ABA triggers ripening by activating ET biosynthesis genes to promote ET release, while ET signaling components reciprocally modulate ABA-related genes to form bidirectional feedback. In non-climacteric fruits, ABA directly governs softening, sugar accumulation, and pigment synthesis while partially synergizing with ethylene, as exemplified by ABA activating ripening-related genes[4]. Their interaction is further modulated by environmental factors and other hormones. Additionally, post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications, as well as epigenetic regulation, have been shown to influence ABA-ET crosstalk by targeting ABA metabolic genes.

-

Although the antagonistic relationship between auxin and ET has been widely reported, current research has revealed that auxin and ET are not just antagonistic during fruit ripening[3]. Reduced auxin concentrations or inhibited auxin transmission can increase fruit tissue susceptibility to ET, increasing the likelihood of fruit ripening[40]. PpILR1, which encodes an IAA-amino hydrolase that releases free IAA, is also a transcriptional activator of PpACS1 that promotes ET production[41]. In peach fruit, auxin increases ET synthesis by boosting expression of ACO1 and ACS1, whereas ET increases auxin transport by increasing transcription of the auxin transport gene PIN1, resulting in high levels of auxin in the early stages of fruit ripening[42]. These results demonstrate the complexity of the crosstalk between auxin and ET during peach fruit ripening.

ARFs in auxin-ET crosstalk

-

Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) play a central role in ethylene-dependent fruit ripening by regulating key genes in ET biosynthesis and signaling pathways, forming complex interaction networks with multiple hormonal signals. In tomato, for example, the expression of SlARF2A and SlARF2B is significantly correlated with fruit ripening, and their suppressed expression leads to impaired ET biosynthesis[43]. Further studies reveal that SlARF2A expression is downregulated in the nor, rin, and Nr mutants and responds to exogenous ET, auxin, and ABA, indicating its potential role as a key node in auxin-ET signaling crosstalk[43]. Additionally, SlARF6A directly binds to the SlSAMS1 promoter to negatively regulate its expression, inhibiting ET production and fruit ripening[44]. Notably, members of the tomato ARF2 protein family exhibit functional divergence: SlARF2A is regulated by ethylene, while SlARF2B is induced by auxin, with both participating in the dual regulation of target genes[43].

In other species, the regulatory mechanisms of ARFs on ET pathways exhibit both conservation and specificity. In apple, MdARF5 directly binds to the promoters of ET biosynthesis-related genes such as MdERF2 and MdACS3a, while MdARF17 indirectly regulates MdACS1 expression by activating MdERF003, forming a cascading regulatory network[45,46]. In papaya, CpARF2 mediates auxin-ET signaling crosstalk by stabilizing the CpEIL1 protein and enhancing its transcriptional activity[47]. In peach, PpARF6 accelerates the ripening process through dual mechanisms: it directly activates ET biosynthetic genes and interacts with PpEIL2/3 to maintain their stability, thereby amplifying the transcription of ethylene-related genes[48]. As a result, the ARF family is likely involved in regulating ET-dependent fruit ripening by interacting with key genes of ET biosynthesis and signal transduction.

At the molecular level, the promoter regions of ARFs often harbor both auxin and ET response elements, suggesting their regulation by multihormonal coordination. For example, 27 ERFs in tomato show upregulated expression during fruit ripening, with some potentially mediating reverse regulation by binding to ARF promoters[49]. Furthermore, ARFs exhibit functional synergy with MADS-box TFs (such as RIN), cooperatively regulating key ET biosynthetic genes[50].

ARFs also orchestrate stage-specific synergy between auxin and ethylene: in the early ripening phase, auxin upregulates ET biosynthetic genes via ARFs, while in later stages, ET induces feedback inhibition of auxin signaling through ERFs[51]. ABA indirectly influences ARF activity by regulating ABF binding sites in the promoters of NOR and RIN genes, forming an ABA-ET-auxin regulatory loop[52]. These findings establish ARFs as molecular hubs integrating multidimensional regulatory signals during ethylene-dependent fruit ripening (Fig. 2).

Aux/IAAs in auxin-ET crosstalk

-

Auxin-dependent gene regulation is mediated by the auxin/indole-3-acetic acid (Aux/IAA) family, which acts as key intermediaries in hormonal crosstalk. In tomato, SlIAA3 expression is induced by ET during fruit ripening, and it positively regulates the transcription of ERFs, highlighting its role in integrating ET and auxin signaling[53]. The ET-responsive factor SlERF.B3 further bridges these pathways by controlling the expression of SlIAA27, thereby coordinating cross-talk between the two hormones[54]. Moreover, SlIAA29 is transcriptionally activated by both auxin and ethylene, suggesting a convergent regulatory input from these signals[55].

In papaya, treatments with 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC, an ET precursor) or ET inhibitors significantly alter the expression of Aux/IAA family genes, indicating their involvement in auxin-ET interactions during fruit ripening[56].

In peaches, the PpIAA1-PpERF4 protein complex not only regulates fruit ripening-related genes but also promotes the expression of PpNCED2 and PpNCED3, revealing a tripartite hormonal interplay[57]. Additionally, PpIAA13 directly binds to the promoter of the ET biosynthetic gene PpACS1 to transactivate its expression. This activity is further modulated through interactions with PpTIR1 (an auxin receptor) and the microRNAs ppe-miR393a/b, forming a regulatory network that jointly controls ACS transcription and fruit ripening[58].

In pears, PbIAA.C3 interacts with the promoter region of PbACS1b to modulate its transcription, directly influencing ET biosynthesis. Notably, PbIAA.C3 expression itself is regulated by PbARF32, suggesting that PbARF32 likely orchestrates ET production through a PbARF32-PbIAA.C3 regulatory loop[59]. These findings collectively demonstrate that Aux/IAA proteins serve as critical nodes in multihormonal networks, integrating auxin, ethylene, and ABA signaling to coordinate fruit ripening across species.

GH3s in auxin-ET crosstalk

-

According to current research, GH3 family genes play a crucial role in fruit ripening by regulating the interaction between auxin and ET. In tomato, the expression of SlGH3.2 is induced during ripening but significantly suppressed in rin and nor mutants. Tomato lines with silenced SlGH3.2 exhibit reduced lycopene content alongside elevated levels of IAA and ethylene, indicating that this gene regulates ripening by coordinating the dynamic balance between auxin and ethylene[60]. Similar mechanisms have been validated in other species: in kiwifruit, the transcription factors AcERF1B and AcERF073 promote IAA degradation by positively regulating AcGH3.1 expression, thereby accelerating fruit ripening[61]. In pears, ET triggers IAA inactivation through PuERF2-mediated activation of PuGH3.1 transcription, establishing a direct link between ET signaling and auxin metabolism[62].

Collectively, these findings highlight that GH3 family members act as critical nodes responding to both auxin and ethylene, likely serving as essential interfaces for hormonal integration during fruit development and ripening.

Other auxin signaling components in auxin-ET crosstalk

-

During tomato fruit ripening, the synergistic regulatory mechanisms between auxin and ET involve multiple key molecular components. The RIN gene not only directly activates the ET biosynthesis System II but also influences fruit sensitivity to ET by regulating the expression of SlSAUR69 (Small Auxin-Upregulated RNA 69)[40]. Studies demonstrate that RIN binds to the promoter region of SlSAUR69 to positively regulate its expression. Overexpression of SlSAUR69 significantly accelerates the initiation of fruit ripening, whereas its suppression delays the ripening process. This regulatory axis (RIN-SlSAUR69-ET sensitivity) is considered a critical mechanism for maintaining the dynamic balance between ET and auxin[40].

Notably, ET signaling also modulates auxin gradient distribution by regulating the expression of auxin transporter-encoding genes. Experimental evidence shows that ET treatment significantly alters the expression patterns of genes such as SlLAX1, SlLAX3, and SlPIN7[55]. Changes in the activity of these transporters may mediate ET's regulation of auxin spatial distribution, thereby affecting the spatiotemporal expression of ripening-related genes. Correspondingly, during the ripening initiation phase, auxin content and the activity of its signaling pathway decline markedly[4]. This endogenous auxin attenuation likely removes the inhibition of ET action, creating conditions for the burst of System II ET synthesis[55].

ET signal in auxin-ET crosstalk

-

In the signal interaction between ET and auxin, ERFs and ARFs play a central role. Research indicates that as downstream regulatory elements of the ET signal, ERFs not only participate in the fruit ripening process mediated by ET but also achieve coordinated regulation through interaction with other hormone pathways. For example, in tomatoes, peaches, and durians, the expression of some ERFs is induced or inhibited by auxin, suggesting that ERFs may serve as a molecular bridge for the interaction between the two hormones[63]. Notably, certain ERFs (such as AP2a) have the function of inhibiting ET synthesis themselves. A decrease in their expression will enhance the ET signal and accelerate fruit softening[3]. This bidirectional regulatory mechanism may explain the molecular basis for the functional diversity of ERFs during the ripening stage.

The regulation of ERFs by key components of the auxin signaling pathway, including ARFs and Aux/IAA proteins, exhibits species-specific characteristics. In apples and peaches, ARFs regulate ERF expression by directly binding to their promoter regions[45,57]. In tomato, however, SlARF2A and SlARF2B display divergent interaction patterns: SlARF2A is regulated by ethylene, while SlARF2B is induced by auxin[43]. SlERF.D7 integrates ET and auxin signals through positive regulation of SlARF2A/B abundance, thereby precisely controlling the tomato ripening process[43]. Additionally, the promoter regions of ARFs contain the response elements for both ET and auxin, suggesting their potential role as integrative nodes for hormonal signals[49].

In other species, interaction mechanisms reveal new dimensions. In papaya, ARFs participate in ripening regulation by modulating the expression of core ET signaling factors EIN3/EIL, while the MADS-box transcription factor CpAGL18 directly activates transcription of both the ET biosynthetic gene CpACS1 and the auxin early-response gene CpSAUR32, forming a cascading amplification effect of hormonal signals[64].

In papaya, ARF family members control the production of EIN3/EIL[47]. Additionally, CpAGL18 has the ability to interact with promoters of CpACS1 and CpSAUR32 and trigger their expression, affecting ET and auxin signals, and controlling papaya fruit ripening[64]. Notably, in some plants, ERF TFs directly interact with GH3, ARFs, and Aux/IAAs[45,57,62], revealing the complexity of hormonal crosstalk.

In summary, the interaction between ET and auxin forms dynamic regulatory networks through ERFs and ARFs, with molecular mechanisms involving transcription factor interactions, promoter binding, and cross-regulation of multiple hormonal signals. This networked regulatory pattern provides a molecular basis for the temporal control of fruit ripening but also increases the complexity of functional dissection, calling for more species-specific functional validation studies.

-

The crosstalk between ABA and auxin in fruit maturation regulation is primarily characterized by their antagonistic yet context-dependent synergistic interactions, with pivotal roles in orchestrating ripening processes across various fruit species. While auxin predominantly governs early developmental phases, ABA emerges as a dominant regulator during the ripening stages, with their dynamic interplay establishing precise regulatory networks[65].

In non-climacteric fruits like strawberries, this regulatory crosstalk is particularly pronounced. ABA promotes fruit ripening by enhancing auxin transport from achenes to the receptacle during early development, upregulating auxin transporter genes such as FaPINs to facilitate receptacle expansion. However, as fruit development transitions to the ripening phase, ABA shifts to suppress auxin biosynthesis in the receptacle, directly counteracting auxin's inhibitory effect on ripening[65]. This temporal antagonism highlights how ABA modulates auxin's activity to initiate senescence-related processes.

In grape berries, the hormonal balance between IAA and ABA acts as a critical ripening switch. During the pre-veraison stage, high auxin levels support seed development and accumulate ARFs in peel tissues[66]. As veraison approaches, the declining influence of auxin and the rising dominance of ABA alter the IAA/ABA ratio, which governs the onset of ripening[66]. This shift exemplifies a synergistic crosstalk where auxin primes developmental readiness, and ABA executes the ripening program, illustrating their complementary roles in sequential regulatory steps.

Tomato studies reveal another layer of interaction: auxin treatment not only delays ripening but also stimulates the biosynthesis of ABA precursors (neoxanthin and violaxanthin), leading to increased ABA concentrations[67]. This positive feedback loop demonstrates how auxin indirectly upregulates ABA pathways, suggesting a complex regulatory interface where one hormone modulates the metabolic precursors of the other, blurring the boundary between antagonism and synergy in ripening control.

At the molecular level, several candidate genes bridge these signaling pathways. In grapes, VvGH3.1, induced by exogenous ABA, represents a potential convergence point of ABA-auxin interaction, possibly integrating hormonal signals through auxin conjugation[68]. In strawberries, FaARF2 directly represses the promoter of FaNCED1, a key ABA biosynthesis gene, establishing a transcriptional link where auxin signaling components directly modulate ABA metabolism to inhibit ripening[69]. Tomato SlARF2A interacts with ABA-responsive ASR1 protein[70], while peach ABA treatment downregulates auxin biosynthesis/signaling genes (Aux/IAA, GH3, PIN1)[71], and auxin upregulates ABA receptor-related genes (PaPP2Cs, PaPYL1) in sweet cherry[72], all indicating conserved molecular mechanisms where TFs and signaling components act as nodal points of crosstalk.

Notably, while receptor-like kinases and ubiquitin ligases respond to both hormones during strawberry ripening, serving as potential signaling linkers, the direct molecular interactions between ABA and auxin signaling cascades remain undercharacterized[73]. Future investigations into key transcription factors in their respective signal transduction pathways—such as ARFs in auxin signaling and ABFs in ABA signaling—are likely to uncover the core regulatory modules governing their crosstalk, providing critical insights into the hormonal networks that drive fruit ripening.

-

GAs exhibit dynamic regulatory roles during fruit development and ripening, with their functions showing marked stage-specificity. In the early stages of fruit development, GAs play a critical role in seed germination, fruit set, and fruit expansion by promoting cell elongation and division[74]. At this stage, GA levels are relatively high in flowers and young fruits but decline significantly as fruits enter the ripening stage[75]. Notably, exogenous GA3 treatment can promote fruit set and fruit growth while delaying the ripening of various climacteric and non-climacteric fruits—a dual effect that reveals the differential regulatory mechanisms of GAs across distinct fruit developmental phases[76,77].

Molecular studies indicate that GA's effects on ripening are closely linked to its interactions with ET and ABA. In tomato, the significant upregulation of the SlGA2ox2 gene during the color-breaking stage reduces endogenous GA levels while activating the expression of ET biosynthesis genes ACS2, ACS4, and ACO1, accelerating ripening[78]. Exogenous GA treatment, or increasing endogenous GA levels through specific overexpression of the GA biosynthesis gene SlGA3ox2 in fruit tissues, delays tomato fruit ripening[74]. This suggests that GA plays a negative regulatory role in ripening by inhibiting ET synthesis, whereas SlGA2ox2 and SlGA3ox2 act as a positive regulator of ripening. Similarly, GA3 treatment in kiwifruit significantly suppresses the expression of ET biosynthesis-related genes, further supporting the antagonistic relationship between GA and ET[76]. In fruits like grapes, the dynamic balance between GA and auxin influences developmental processes by regulating genes such as VvIAA9 and VvARF7, highlighting the complexity of hormonal network regulation[79].

The interaction between GA and ABA is particularly critical for fruit color transition. In sweet orange peel, the decline in active GA1 and GA4 levels leads to sugar and ABA accumulation, promoting the activation of metabolic pathways related to carotenoid synthesis and ultimately driving peel color change[80]. At the mechanistic level, GA inhibits the accumulation of phytoene and carotenoid precursors by maintaining high lutein levels, indirectly blocking ABA biosynthesis[81]. This GA-ABA antagonism also exists in strawberries: GA promotes ABA accumulation by upregulating the FaGAMYB gene to enhance fruit coloration, while ABA accelerates the degradation of the GA biosynthesis enzyme ClGA20ox through ClSnRK2.3 phosphorylation, forming a bidirectional regulatory loop[82].

Many gaps remain in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of hormonal interactions. For example, genes like FaGAST1/2 in strawberries have been confirmed to participate in GA signaling, but their specific regulatory networks remain unclear[83]. Future research should focus on: (1) the stage-specific regulatory mechanisms of GA metabolic enzymes during different fruit ripening phases; (2) the cross-regulatory networks between GA and other hormones such as JA and BR; (3) gene function validation using technologies like CRISPR/Cas9. These explorations will deepen our understanding of GA's 'promoting development-inhibiting ripening' dual role in fruit maturation and provide theoretical foundations for precise regulation of fruit quality.

-

CKs, as N6-substituted adenine derivatives, play a key regulatory role in plant cell proliferation and differentiation. During fruit ripening, exogenous CK treatment exhibits a significant retarding effect. Exogenous CK application prior to fruit ripening delays fruit ripening and softening in peaches[84]. Exogenous CK reduces chlorophyll loss and anthocyanin accumulation in ripe fruit peels in lychee[85]. Mango fruits treated with synthetic 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) can inhibit the activities of ACS and ACO, resulting in inhibition of ET production and a delay in fruit ripening and senescence[86]. These studies indicate that CKs mediate their inhibitory effects on ripening by regulating the activity of key enzymes.

Although the molecular mechanisms of CK interaction with other hormones remain incompletely elucidated, multiple studies have revealed cross-regulatory networks with ET and ABA. In loquat fruits, CK levels decline sharply before ripening initiation, while ET concentrations rise, suggesting that the dynamic balance between ET and CK may be a critical condition for triggering ripening[87]. In cantaloupe, increased levels of endogenous CK partially offset the effects of ET during fruit ripening[88]. Research in kiwifruit further confirms that synthetic CKs not only inhibit ET synthesis but also affect ripening by regulating genes related to placental softening[89]. Such hormonal interactions may be mediated by TFs, as ARFs and ERFs have been confirmed to participate in CK signal transduction[90].

Notably, CKs and ABA exhibit significant antagonistic effects in ripening regulation. Comparative transcriptome analysis in litchi shows that ABA treatment promotes pericarp color transition, while CKs inhibit this process, with the two hormones achieving functional opposition through differential regulation of genes related to pigment metabolism[91]. This antagonism is supported at the hormonal signaling level: as classic ripening-promoting hormones, ET and ABA show significantly upregulated pathway genes during ripening, while genes related to CK and GA signaling tend to be downregulated[4]. In the regulatory model of fleshy fruit ripening, the roles of development-related hormones such as CK/GA are gradually replaced by ABA/ethylene, forming a regulatory switch from cell division to ripening.

-

JA and its derivatives (such as methyl jasmonate, MeJA) exhibit complex regulatory networks during fruit ripening, with their mechanisms of action involving hormone concentration-dependent effects, multi-pathway signaling crosstalk, and species-specific response patterns[92].

Concentration-dependent bidirectional regulatory effects

-

JA exhibits a pronounced concentration-threshold effect on fruit ripening. In apples, different MeJA concentrations yield opposing effects: 10 μM delays ripening (reducing ET release by 42%), while 1000 μM promotes ripening (increasing the rate of firmness decline by 55%)[93]. This concentration-dependent response may relate to the threshold accumulation of JAZ proteins, core repressors in JA signaling-at low concentrations, JAZ is degraded to release MYC2 and activate ripening genes, whereas high concentrations may trigger feedback inhibition loops.

Spatiotemporal specificity of hormonal interaction networks

-

In various reports, JA exhibits synergy or antagonism with ET in different fruits. In peach fruits, treatment with 100 mM MeJA reduces ET production by inhibiting the key ET biosynthesis genes PpACS1 and PpACO1, while simultaneously activating anthocyanin biosynthesis genes[94]. In apples, a positive regulatory pattern exists: MdMYC2 directly binds to the promoter regions of ET biosynthesis genes MdACS1 and MdACO1 to promote their transcription, whereas MdERF4 forms a JA-ET signaling integration module through physical interactions that bridge JAZ repressors and MYC2 transcription factors[95].

Metabolic coupling also exists between JA and ABA. In strawberries, MeJA treatment induces the upregulation of ABA biosynthesis genes NCED1/2/3, ultimately leading to a 2.3-fold increase in ABA content, with the two hormones synergistically promoting ripening[96]. In grapes, however, an antagonistic relationship emerges: exogenous MeJA inhibits the expression of the auxin biosynthesis gene VvYUC, causing a decrease in IAA levels, while activating the ABA-degrading enzyme gene VvCYP707A and reducing ABA levels[97]. Such discrepancies may arise from species-specific differences in the interaction specificity of hormonal signaling hub proteins.

Molecular regulatory pathways of JA

-

Like other hormones, TFs also play a crucial role in the crosstalk between JA and other hormones. SlERF.B8, as a key mediator in ET-JA crosstalk, directly binds to the promoter elements of JA biosynthesis genes LOXD, AOC, and OPR3[98]. MYC2 participates in JA signaling, and MdMYC2 promotes ET biosynthesis and fruit ripening in apple by binding to promoters of MdACO1 and MdACS1[95]. MdERF4 inhibits expression of MdACS1 and MdACO1 by interacting with JAZ, as well as with the JA-activated transcription factor MYC2, indicating that it functions as a molecular link between ET and JA hormone signals[99].

Although JA has multiple functions in fruit ripening, there is a lack of evidence of molecular interactions to support the crosstalk between JA and other hormones. In the future, research focusing on the interactions between signaling molecules in the JA pathway and those of other hormones will play an important role in elucidating the crosstalk between JA and other hormones.

-

As an endogenous signaling molecule in plants, SA significantly delays fruit ripening and senescence by regulating the metabolic networks of ET and auxin. Its mechanism of action involves multilayered molecular regulation and is closely associated with fruit developmental stages and treatment concentrations.

The inhibitory effect of SA on ET biosynthesis may occur by suppressing the gene expression and enzyme activity of ACS and ACO. In pear fruits, SA treatment causes a 42% and 38% reduction in ACS and ACO activity, respectively, and delays the peak of ET production by 5–7 d[100]. Meanwhile, in pear fruits, PpEIN3b, as a core transcription factor in ET signaling, can integrate SA and ACC signals and is likely a key factor in the crosstalk between ET and SA[101]. SA decreases PpEIN3a expression, while ET, auxin, and glucose increase it[102].

It is worth mentioning that the effect of SA on ET production is affected not only by treatment concentration but also by the stage of fruit development[103]. ARF2A-overexpressed tomatoes had lower SA content and ripened later, implying that auxin can limit SA production via ARF2A[70]. Exogenous SA also alters the expression of genes involved in auxin signaling, such as Aux/IAAs in papaya[56].

Although numerous studies have demonstrated that SA can influence fruit ripening by inhibiting ET biosynthesis, more molecular biological evidence is required. SA delays fruit ripening through multi-target regulation to form hormonal interaction networks and its concentration- and stage-dependent characteristics provide a theoretical basis for the development of precision preservation technologies. In the future, integration of single-cell sequencing, proteomics, molecular biology, and other technologies will be necessary to elucidate spatiotemporal-specific regulatory networks.

-

BRs primarily interact with ET to regulate fruit ripening, playing an important role in both climacteric and non-climacteric fruit development.

Emerging evidence highlights BRs as promoters of fruit ripening: exogenous BR application, overexpression of BR biosynthesis genes, or activation of BR signaling TFs consistently accelerates ripening across species[104]. For instance, BR treatment upregulates transcription of ET biosynthesis genes ACS2, ACS4, ACO1, and ACO4 in tomato fruit[105]. In tomato, overexpression of DWF (a key BR biosynthesis gene) enhances ET production and speeds ripening[106]; similarly, heterologous expression of the cotton gene GhDWF4 in tomato promotes ripening while increasing soluble sugar and vitamin C content[107]. Coincidentally, ET-induced AP2a modulates carotenoid biosynthesis by inhibiting DWF expression and BR accumulation[108], illustrating the bidirectional crosstalk between these pathways.

BR biosynthesis gene SlCYP90B3 in tomato, when overexpressed, elevates ACS2, ACS4, and ACO1 expression, boosts ET production, and accelerates ripening[109], reinforcing BR-ET synergism. Key BR signaling components like BRI1 (receptor) and BZR1/2 (TFs) also shape ripening: overexpressing SlBRI1 in tomatoes enhances ET biosynthesis, accelerates ripening, and increases carotenoids, ascorbic acid, soluble solids, and sugars during fruit maturation[110]. In bananas, MaBZR1/2 TFs bind to the CGTGT/CG motif in promoters of MaACS1, MaACO13, and MaACO14, directly repressing their transcription[111], while in persimmons, DkBZR1 and DkBZR2 act as repressors or activators of ripening by binding ACS/ACO promoters[112], demonstrating species-specific regulatory nuances.

Collectively, these findings reveal extensive BR-ET interactions during fruit ripening. However, direct molecular evidence of ET-BR pathway crosstalk—such as physical interactions between their signaling components—remains limited. Future research should prioritize identifying shared TFs, kinases, or regulatory hubs that bridge these pathways, leveraging multi-omics approaches to dissect their spatiotemporal coordination in fruit development.

-

Fruit ripening is orchestrated by an intricate hormonal crosstalk network. ET plays a pivotal role in the ripening process of climacteric fruits. Current research has identified crucial crosstalk molecules between ABA and ET. The interaction between ABA and ET may predominantly rely on the interplay of NAC TFs, and it could also involve certain members of the MADS, bHLH, and C2H2 TF families (Table 1). Intriguingly, the DNA demethylation gene DML2 might be the focal point of the hormonal crosstalk that regulates fruit maturity between these two hormones.

Table 1. A summary of hormone crosstalk interaction data.

Nod I Species Nod II Hormone crosstalk Experiment evidence of interaction Ref. SlAREB1 Solanum lycopersicum NOR ABA → NOR Y1H, EMSA, Dual-luciferase Mou et al.[15] SlNAC1 Solanum lycopersicum SlPYL2, SlAREB1 TFs → ABA Y2H, BiFC Yang et al.[19] SlNAC1 Solanum lycopersicum SlACS2, SlACO1 TFs → ET Y1H Ma et al.[18] SlNAC4 Solanum lycopersicum SlACS2, SlACO1, SlACO6, SlACS8 TFs → ET Y2H, BiFC, EMSA Yang et al.[19] SlNAC4 Solanum lycopersicum SAPK3, SlPYL9, SlCYP707A1 TFs → ABA Y2H, BiFC, Y1H, EMSA SlNAC9 Solanum lycopersicum SlAREB1, SlPYL9 TFs → ABA Y2H, BiFC Yang et al.[19] SlNAC9 Solanum lycopersicum LeACO1, LeACS2, LeACS4 TFs → ET EMSA Kou et al.[17] NOR Solanum lycopersicum SlACS2 TFs → ET EMSA Gao et al.[20] SlZFP2 Solanum lycopersicum NOT, SlAO1, SIT, FLC TFs —| ABA ChIP, EMSA, Weng et al.[11] SlJMJ7 Solanum lycopersicum ACS2, ACS3, ACO4, RIN, NOR, DML3 JMJ —| ET ChIP-seq Ding et al.[28] PpERF3 Pyrus pyrifolia PpNCED2/3 ET → ABA Y1H, Dual-luciferase Wang et al.[33] PpERF2 Pyrus pyrifolia PpNCED2/3 ET —| ABA Y1H, EMSA, Dual-luciferase Wang et al.[34] MaEBF1 Musa acuminata MaABI5 ET — ABA Y2H, BiFC, Co-IP Song et al.[36] SlARF2A Solanum lycopersicum SlASR1 Auxin — ABA Y2H, BiFC Breitel et al.[70] SlARF6A Solanum lycopersicum SAMS1 Auxin —| ET EMSA, Dual-luciferase, ChIP Yuan et al.[44] PpILR1 Pyrus pyrifolia PpACS1 Auxin → ET Y1H, EMSA, Dual-luciferase Wang et al.[41] CpARF2 Carica papaya CpEIL1 Auxin → ET Y2H, BiFC, Co-IP Zhang et al.[47] MdARF5 Malus domestica MdACS3a, MdACS1, MdACO1, MdERF2 Auxin —| ET ChIP-PCR Yue et al.[45] CpAGL18 Carica papaya CpACS1, CpSAUR32 TFs → ABA/Auxin Y1H, EMSA, ChIP-qPCR Cai et al.[64] SlERF.D7 Solanum lycopersicum SlARF2A/B ET → Auxin Y1H, EMSA, Gambhir et al.[43] SlERF.B3 Solanum lycopersicum SlIAA27 ET → Auxin EMSA Liu et al.[54] PpERF4 Pyrus pyrifolia PpIAA1, PpNCED2/3 ET — Auxin/ABA Y2H, BiFC, Y1H, EMSA Wang et al.[57] AcERF73/1B Actinidia chinensis AcGH3.1 ET —| Auxin Y1H, Dual-luciferase Gan et al.[61] PuERF2 Pyrus ussuriensis PuGH3.1 ET —| Auxin Y1H, EMSA Yue et al.[62] RIN Solanum lycopersicum SlSAUR69 ET — Auxin Dual-luciferase Shin et al.[40] MdMYC2 Malus domestica MdACO1, MdACS1, MdERF2/3 JA → ET Y1H, EMSA, ChIP-PCR Li et al.[95] MdERF4 Malus domestica MdJAZ, MdMYC2 ET — JA ChIP-seq, BiFC Hu et al.[99] SlERF.B8 Solanum lycopersicum SlLOXD, SlAOC, SlOPR3 ET → JA ChIP-qPCR, Dual-luciferase Ding et al.[98] MaBZR1/2 Musa acuminata MaACS1, MaACO13, MaACO14 BR —| ET EMSA, Dual-luciferase Guo et al.[111] DkBZR1/2 Diospyros kaki DkACS1, AkACO2 BR —| ET EMSA, Dual-luciferase He et al.[112] SlAP2a Solanum lycopersicum DWF ET —| BR Y1H, EMSA, Dual-luciferase Sang et al.[108] → indicates a positive effect, —| indicates a negative effect, and — indicates other interactions. The crosstalk among auxin, ABA, and ET is far more complex. ARFs and Aux/IAAs within the auxin pathway serve as core signals influencing their molecular crosstalk (Fig. 2). Notably, the crosstalk between auxin and ET can be either positive or negative. Overall, ET and ABA are highly likely to be part of a feedback loop with ARFs and Aux/IAAs. ET and ABA can modulate the expression of ARFs and Aux/IAAs, and some of these factors can, in turn, regulate the synthesis or signal transduction of ET and ABA.

Although there have been reports of crosstalk between GA, CK, SA, ABA, and ET, there is limited evidence of direct molecular interactions among them. In contrast, several study results indicate that JA and BR can directly regulate ET biosynthesis through intermolecular interactions. However, it remains unclear whether the key genes in the JA and BR signaling pathways interact with each other. It is also uncertain whether JA and BR interact with ET and ABA via the key TFs involved in fruit ripening.

Based on the molecular basis of the crosstalk between ABA, ET, and auxin, genes in the hormone signaling pathway are very likely to play a key role in the crosstalk between different hormones. Uncovering the potential target genes or proteins of the key genes in the hormone signaling pathways is an exciting task that may bring us closer to understanding the complex molecular mechanism of hormone crosstalk. Other regulatory factors related to fruit ripening, such as nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and non-coding RNAs, can have crosstalk with hormones and may also act as mediators of hormone crosstalk.

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 32202129, 32202563, 32230092, 32372403), Chongqing Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos cstc2020jcyj-bshX0067, CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0529), the New Youth Innovation Talent Project of Chongqing (CSTB2024NSCQ-031) and Science and Technology Research Projects of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No. KJQN202401308) and Chongqing Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (CQMAITS202302).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Zhu W and He W meticulously collected the pertinent literature and accomplished the composition of this comprehensive review. Wu T, Ran Y, and Li W actively engaged in the retrieval of materials concerning different hormone studies in relation to fruit ripening. Huang B, Cui G, Wang K, and Wang P revised the draft of the manuscript. Huang B and Cui G designed and supervised the work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Wei Zhu, Wei He

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu W, He W, Wang K, Ran Y, Li W, et al. 2025. Phytohormone cross-talk during fruit ripening: linked biosynthesis and signaling. Plant Hormones 1: e010 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0010

Phytohormone cross-talk during fruit ripening: linked biosynthesis and signaling

- Received: 10 February 2025

- Revised: 16 April 2025

- Accepted: 21 April 2025

- Published online: 29 May 2025

Abstract: Numerous plant hormones play important roles in fruit maturity. Ethylene (ET) and abscisic acid (ABA) affect the ripening of climacteric and non-climacteric fruits, respectively. Auxins, gibberellin (GA), cytokinin (CK), jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and brassinosteroid (BR) also regulate fruit ripening. Hormones' individual or combined effects on fruit ripening have long been one of hot topics in hormones research. It is now widely accepted that fruit ripening is regulated by a complex multi-hormonal crosstalks rather than by a simple antagonistic or synergistic interactions. While the importance of the interactions between multiple hormone signaling pathways is widely documented, integration of the recent advances in our understanding of the molecular events underlying this process during fruit ripening and senescence is not thoroughly addressed. Here we summarize the most advanced discoveries related to the hormone crosstalk underpinning the transition to ripening, with a particular emphasis on the interactions between hormonal signalings and developmental factors known to control fruit ripening. This sheds light on the molecular mechanisms leading to the genetic reprogramming underlying the fruit ripening process.

-

Key words:

- Fruit ripening /

- Phytohormone crosstalk /

- Ethylene /

- Abscisic acid /

- Auxin /

- Brassinosteroid /

- Jasmonic acid