-

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) ranks among the world's most nutritionally significant cereal crops, serving as a dietary staple and industrial raw material for diverse food products[1]. Fusarium head blight (FHB), primarily caused by Fusarium graminearum, poses a critical threat to global wheat production. This disease not only reduces yields but also contaminates grains with deoxynivalenol (DON) and other mycotoxins[2]. Since 1950, at least 30 FHB epidemics have been reported in China, with their occurrence reported almost every year in the past 20 years, affecting over 45 million hectares of land on average and causing crop losses of over 3.41 million tons from 2000 to 2018[3]. FHB usually occurs between mid-April and mid-May, which encompasses the wheat flowering and pollination period. F. graminearum penetrates wheat flowers via natural openings or the cuticle during flowering[4]. During this process, F. graminearum secretes various enzymes, including cuticle enzymes, cell wall–degrading enzymes, and lipase, and activates the biosynthesis of DON, thus completing the initial infection[5].

When a pathogen invades a plant, the plant initiates multiple layers of immunity, including innate immunity and acquired immunity initiated by plant hormones. Innate immunity includes pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI)[6,7], also known as local immunity. Unlike PTI- and ETI-mediated local immunity, hormones, notably salicylic acid (SA) trigger systemic acquired resistance (SAR), a whole-plant immune response that synergistically enhances plant defense in combination with PTI and ETI[8,9]. SA is the core of the hormone regulatory network, and SA-mediated response is an important part of immune regulation. There are some studies that show that SA directly inhibits the growth and development of F. graminearum hyphae and spores, reduces the synthesis of DON toxin[10], and affects the proteins on the cell wall and membrane[11,12]. Therefore, for F. graminearum, effective clearance of SA and destruction of SA-mediated signal transduction are the key requirements for promoting colonization. This review summarizes the role of SA in the interaction between wheat and F. graminearum, hoping to provide help for FHB resistance breeding.

-

SA plays a key role in plant disease resistance by inducing extensive transcriptional reprogramming of genes and enhancing PTI and ETI[13,14]. SA biosynthesis occurs via two pathways: phenylalanine and isochorismate. PAL and ICS are key enzymes, with ~90% of SA produced through the isochorismate (ICS) pathway[15,16]. A previous study showed that silencing barley ICS1/ICS2 reduced resistance to FHB, whereas PAL-deficient mutants showed no significant changes[17], consistent with findings in TaICS1- and TaPAL2-silenced wheat[18]. The core regulatory mechanism of SAR centers on non-expresser of pathogenesis-related genes 1 (NPR1)[19]. It interacts with TGA transcription factors to modulate the expression of pathogenesis-related proteins and cooperates with WRKY transcription factors[20,21]. In contrast, the SA receptors NPR3/NPR4 act as transcriptional repressors and are inhibited by SA during defense responses[22]. During ETI, SA perception by NPR1 and NPR3/NPR4 is essential for activating the biosynthesis of N-hydroxypipecolic acid (NHP), a key component inducing SAR[23]. Additionally, PTI and ETI are severely compromised in npr1-1 npr4-4D double mutants, highlighting the critical roles of NPR1 and NPR4 in these immune responses[24]. A previous study reported that the introduction of NPR1 into wheat-susceptible varieties successfully improved wheat FHB resistance, indicating that NPR1 plays a key role in wheat disease resistance[25]. However, silencing TaNPR1 and TaNPR3 decreased wheat FHB resistance, whereas silencing TaNPR2 did not[18]. It is suggested that NPR1 may play a more complex role in wheat. TaLRRK-6D encodes a leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (LRR-RLK), which belongs to the pattern recognition receptor (PRR) of the plant immune system. Silencing TaLRRK-6D inhibited the expression of ICS1, PAL, NPR1, NPR3-LIKE, and NPR4 in wheat, resulting in a more severe reduction in FHB resistance than silencing TaICS1 and TaNPR1, respectively[26]. In conclusion, the above studies prove that SA is very important for plant resistance, and the silencing of genes related to SA signal synthesis and signal transduction leads to severe FHB infection in wheat.

-

In the course of a pathogen infection, the host environment is stimulated, leading to an increase in the levels of secondary metabolites such as SA and linoleic acid[27−29]. The study showed that high SA concentration limited the spore germination and hypha growth of F. graminearum, and reduced DON synthesis[10]. Elevated SA inhibits antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX)[30], leading to ROS accumulation and oxidative damage.

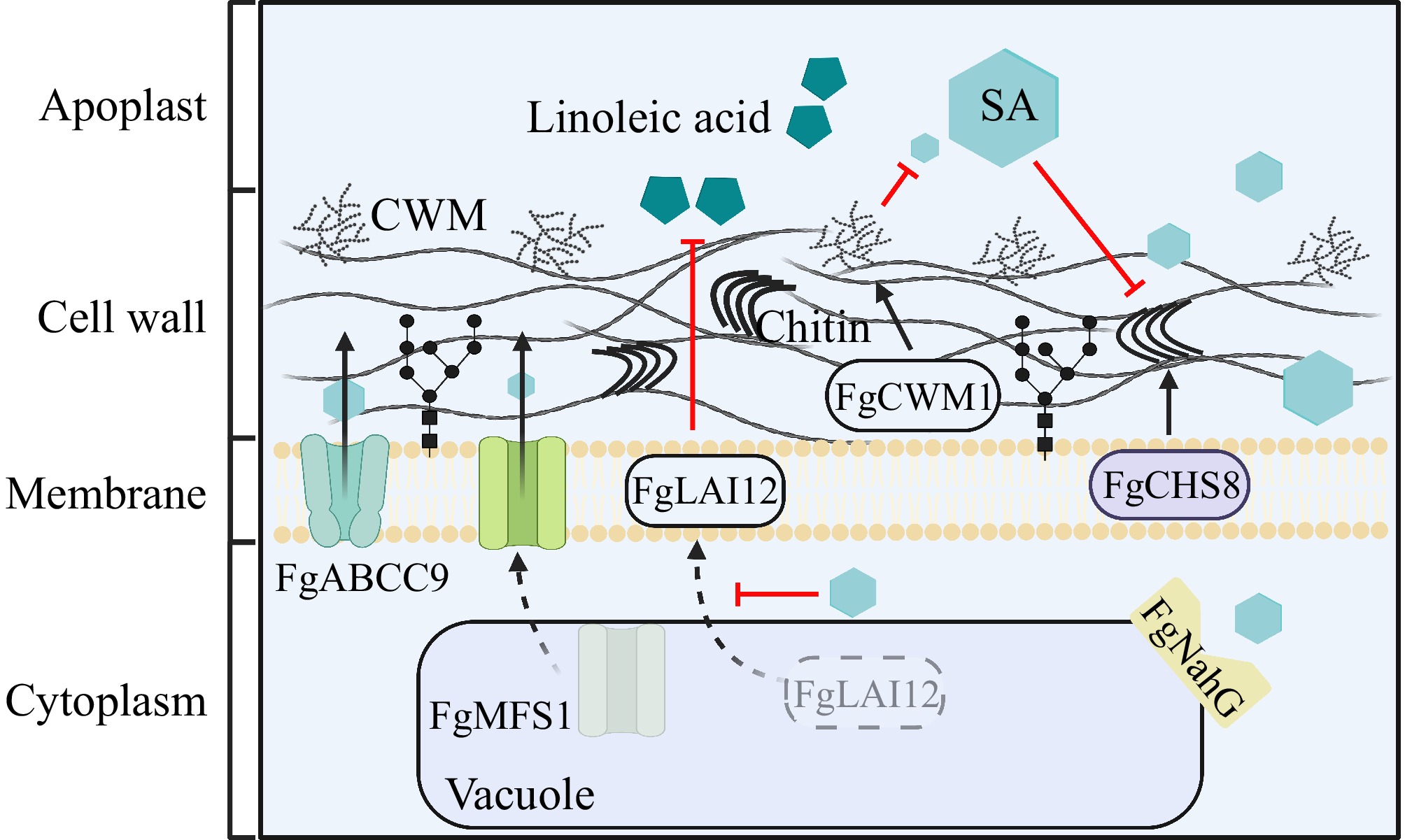

SA can directly affect proteins on the cell wall and membrane of F. graminearum. The cell wall of F. graminearum, consisting of chitin, glucan, and cell wall mannoprotein (CWM)[31], was the first to contact the wheat apoplast and faced the challenge of SA. Chitin can be recognized by PRRs such as CERK1[32], and studies have shown that this process promotes the accumulation of SA in cells[33]. Studies have demonstrated that chitin is associated with fungal growth, development, and pathogenicity. FgCHS8, a chitin synthetase in F. graminearum, was inhibited by SA, and its mutant strains showed decreased chitin synthetase activity and decreased DON synthesis. Under high SA conditions, the mutant showed more severe growth restriction than the wild type[10,34]. CWMs, which have a strong influence on fungal growth and pathogenicity[35,36]. Research has demonstrated that the F. graminearum CWM synthesis FgCWM1 is induced by SA, it can resist SA by enhancing cell wall integrity. Its mutant strain displayed reduced accumulation of mannose and proteins in the cell wall, especially under high SA conditions, leading to cell wall defects and increased sensitivity of the strain to SA[11]. Salicylic acid also promotes the action of other secondary metabolites on F. graminearum. Linoleic acid, a type of unsaturated fatty acid, plays a critical role in fungal growth, toxin synthesis, pathogenicity, and sexual and asexual spore production through its metabolic pathway. Linoleic acid isomerase (LAI) participates in this metabolic pathway[37]. The FgLAI12 metabolizes linoleic acid in the host environment, with its subcellular localization shifting from the vacuole to the cell membrane during this process. SA inhibits this translocation, and the ΔFgLAI12 mutant exhibits limited hyphal growth and reduced DON synthesis[38]. In summary, although the mechanism by which SA enters F. graminearum remains unclear, SA significantly influences the biological activity of this fungus. SA impacts the cell environment and directly affects F. graminearum's cell wall, cell membrane, chitin synthesis, hypha growth, and DON synthesis, thus influencing its biological activity (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The strategy of Fusarium graminearum against SA. SA can be toxic to the cell membrane and cell wall of F. graminearum and affect chitin production. In response, F. graminearum activated the transcription of a large number of genes. Specifically: FgCWM1 generates cell wall mannoprotein (CWM), which resides SA at the outermost layer of F. graminearum's cell wall. FgCHS8 located on the cell membrane is chitin synthase and is inhibited by SA. FgABCC9 and FgMFS1, as transport proteins that function on the cell membrane, transport the intracellular SA of F. graminearum to the extracellular space, among which the subcellular localization of FgMFS1 is transferred from the vacuole to the cell membrane. FgLAI12 also needs to be transferred from the vacuole to the cell membrane to resist the toxicity of wheat linoleic acid, and SA prevents its translocation. SA carboxylase FgNahG degrades SA near the vacuole.

-

To overcome SA-mediated defenses, F. graminearum can directly expel SA and degrade SA, to alleviate the persecution of SA. F. graminearum possesses two SA transporters: the ABC transporter FgABCC9 and major facilitator superfamily 1 (FgMFS1). During infection, when wheat synthesizes and releases a greater amount of SA, FgMFS1 starts altering its expression level and subcellular localization, moving from the vacuole to the cell membrane and acting synergistically with FgABCC9 to transport SA out of the cell to minimize its toxicity[12,39]. FgNahG, a salicylate hydroxylase in F. graminearum, is upregulated by SA during infection and converts SA into catechol. Deletion mutants of FgNahG exhibited reduced pathogenicity and increased SA sensitivity[40].

In addition to the above direct means, the use of Jasmonic acid (JA)/ethylene (ET) antagonism with SA to suppress SA-mediated resistance signals is an indirect means for many pathogens[41,42]. In wheat, JA contributes positively to FHB resistance; the silencing genes involved in the JA biosynthetic pathway, such as TaAOS, TaAOC, and TaOPR3, result in reduced resistance to FHB[43]. Generally, high concentrations of ET promote the pathogenicity of necrotrophic pathogens[44], and silencing the key gene TaACS2 in the ET biosynthesis pathway enhances resistance to FHB during the early stages of infection in wheat[45]. Mechanistically, SA controls the JA/ET signaling pathway through NPR1. NPR1 can regulate the transcription of WRKY70, a negative regulator of JA, and bind to EIN3, a key regulatory gene of the ET pathway, thereby removing the transcriptional inhibition of SID2, a gene related to SA synthesis[41,46,47]. In wheat, TaWRKY70 has been reported to positively contribute to FHB resistance[48]. It is suggested that the antagonism of SA and JA is important for FHB resistance in wheat.

Exogenous SA promoted FHB resistance in the early stage of wheat infection, whereas methyl jasmonate (MeJA) initially promoted FHB development. However, after 48 h of infection, exogenous MeJA inhibited FHB development[18]. As the disease progresses, the plant's hormone content indicates that SA synthesis is inhibited, while the content of JA gradually increases[49]. This may be because F. graminearum has two stages of infection: in the early stages, it resembles a biotrophic pathogen, and in the later stages, it transitions into a necrotrophic pathogen[50,51]. JA and ET usually work together to mediate resistance to necrotic pathogens[52], while SA dominates resistance to biotroph pathogens[53]. Surprisingly, during the infection process of F. graminearum, TaNPR1 was not induced by exogenous SA, but by exogenous JA, whereas TaNPR2/3 was induced by both exogenous SA and JA[49]. This may imply that the SA pathway genes are also regulated by JA induction when wheat is resistant to FHB. Studies have shown that TaSSI2 negatively regulates FHB resistance. Exogenous SA promoted TaSSI2 expression, while exogenous MeJA inhibited TaSSI2 expression. However, silencing TaSSI2 activated the expression of the SA pathway gene PR5 and the JA/ET pathway-related gene PR4, improving FHB resistance in wheat[54]. In other words, an increase in JA content inhibits TaSSI2 expression and activates the SA pathway as the necrotrophic stage progresses. Therefore, we believe that the antagonism between SA and JA/ET pathways plays a crucial role in FHB resistance, and changes in hormone content may be an active selection by wheat rather than a passive induction by pathogens.

-

This review systematically synthesizes the dual roles of salicylic acid (SA) in wheat-Fusarium graminearum interactions, highlighting its critical functions in both host defense activation and pathogen counter-adaptation. SA-mediated resistance works through two interrelated mechanisms: direct inhibition of fungal growth and DON biosynthesis through perturbation of cell membranes and cell walls; and indirect regulation of hormone signaling networks to coordinate PTI/ETI responses. Conversely, F. graminearum has evolved sophisticated countermeasures, including SA efflux systems, SA hydroxylase[11,12,39,40], and manipulation of JA/ET antagonism, to overcome host defenses[49,54]. These findings underscore the dynamic co-evolutionary arms race between wheat and F. graminearum, with SA serving as a central battlefield.

Major advances in wheat and F. graminearum interaction include functional validation of wheat SA pathway components such as TaNPR1, TaICS1, and TaLRRK-6D by BSMV-VIGS, demonstrating their important role in FHB resistance[18,26]. Overexpression of TaICSA (TraesCS5A02G193800) can reduce the incidence of FHB by 55%−66%[55], representing a significant breakthrough for transgenic breeding. However, the translation of these discoveries into commercial cultivars remains limited, primarily due to challenges in pyramiding multiple resistance genes and understanding their epistatic interactions.

Additionally, systems biology approaches integrating transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics will provide holistic insights into SA-hormone crosstalk during F. graminearum's biotrophic-necrotrophic transition. Understanding how wheat dynamically adjusts SA-JA/ET balances represents a frontier for developing durable resistance strategies. Given F. graminearum's adaptive adaptive during necrotrophic phases, leveraging SA-mediated defenses during the biotrophic window holds promise for precision breeding. By bridging basic research and applied biotechnology, this field can unlock novel solutions to combat FHB, ensuring global food security.

This work was supported by grants to Xu Q from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32102229), and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFSC0405).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xia Y, Wei Y, Xu Q; data collection: Wu Q, Jiang Q, Ma J, Zheng Y; draft manuscript preparation: Xia Y. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xia Y, Wu Q, Jiang Q, Ma J, Zheng Y, et al. 2025. Salicylic acid signaling in wheat-Fusarium graminearum. Plant Hormones 1: e011 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0011

Salicylic acid signaling in wheat-Fusarium graminearum

- Received: 15 February 2025

- Revised: 07 May 2025

- Accepted: 12 May 2025

- Published online: 09 June 2025

Abstract: Salicylic acid (SA) plays a crucial role in defense against Fusarium head blight (FHB), a devastating disease primarily caused by Fusarium graminearum. This review examines the current understanding of SA-mediated resistance mechanisms and the counterstrategies employed by the pathogen. SA not only activates systemic acquired resistance (SAR) through the NPR1 signaling pathway, promoting the transcription of defense genes, but also directly inhibits spore germination, mycelial growth, and synthesis of chitin and deoxynivalenol toxin in F. graminearum, thereby reducing its virulence. F. graminearum counteracts SA-dependent immunity through multiple strategies: manipulating hormone signaling, enhancing cell wall integrity, deploying SA transporters, and degrading SA via salicylic hydroxylase. Despite significant progress, gaps remain in comprehending SA's role in wheat-FHB interactions, particularly regarding hormone signaling networks and the mechanisms of SA-responsive genes. This review synthesizes existing knowledge and identifies future research directions, to provide insights to enhance wheat resistance to FHB through the manipulation of the SA pathway.

-

Key words:

- Fusarium head blight /

- Salicylic acid /

- Hormone signaling /

- Plant immunity