-

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), a member of the Solanaceae family, native to the Andean highlands of South America, displays both annual and perennial growth patterns. This economically important crop has gained global popularity due to its flavorful fruits, which boast diverse pigmentation and exceptional nutritional value, making them one of the world's most widely consumed vegetable crops[1]. However, as consumer standards continue to rise, there is growing emphasis on tomato fruit quality in commercial markets. Malformed fruits represent a significant economic challenge in tomato production, negatively impacting both marketability and practical utility while posing a major threat to the industry's sustainable growth. Current research has established a direct relationship between ovary locule number and fruit deformity in tomatoes. Higher locule counts correlate strongly with increased malformation rates, whereas fewer locules typically produce smaller fruits with lower deformity susceptibility[2]. This connection makes understanding the genetic regulation of locule number determination particularly valuable - both theoretically for plant developmental biology and practically for reducing economic losses from abnormal fruit formation in commercial tomato cultivation.

Contemporary research consensus is that the tomato locule number is principally governed by genotype-specific genetic characteristics, while being modulated through complex interactions with environmental conditions, nutrient availability, and phytohormonal signaling. Crucially, the plant's genetic character remains the dominant regulatory factor, with external influences likely mediating their effects indirectly through transcriptional reprogramming of locule-associated genetic networks[3,4]. This study focuses on elucidating the mechanisms of malformed tomato fruits and their contributing factors, aiming to systematically delineate the molecular regulatory network underlying multilocular malformed fruit development. The findings offer a scientific framework for creating technologies to predict and prevent these issues, as well as for designing stress-resistant cultivars through marker-assisted breeding. Additionally, this research serves as a valuable reference for addressing developmental abnormalities across diverse fruit crop species facing similar environmental challenges.

-

Tomato fruit malformation primarily stems from two key causes: (1) irregular flower bud development, and (2) uneven fruit growth patterns[5]. These malformations can be categorized by their connection to ovary locule number: multilocular and non-multilocular types. Multilocular cases mainly result from genetic factors and environmental stresses during the seedling growth stage, while non-multilocular forms typically arise from improper hormone use or physical damage during fruit set[6]. The number of locules directly reflects the carpel count. As flowers mature, fused carpels create the ovary - a process controlled by carpel primordia development. This biological mechanism not only determines locule quantity but also ensures proper flower development, making it critical for normal ovary shaping.

-

Research has shown that the formation of multilocular tomatoes is closely linked to specific genetic loci. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) analyses of tomato fruit size have identified two loci, fw2.1 and fw11.3, critically associated with locule number determination. These loci correspond to the classical fasciated (fas) and locule number (lc) genes, located on chromosomes 11 and 2, respectively. Notably, the lc locus governs the clustered locule morphology characteristic of fasciated fruits[7]. In tomato plants, locule number directly determines fruit shape and size. Wild tomato varieties and small-fruited cultivars typically produce fruits with 2−4 locules, whereas large-fruited, multilocular cultivated varieties harbor mutations in either or both fas and lc. Remarkably, the combined mutations of lc and fas generate extra-large fruits exceeding 500 g[8]. These loci exhibit epistasis, with each independently increasing locule number: lc mutations elevate locule count by 2−4[9], while natural fas mutations produce over 15 locules.

The lc locus maps to a non-coding region 1,080 bp downstream of WUSCHEL (WUS), a key gene maintaining stem cell identity in meristems[10]. Functional analyses have revealed that lc is associated with two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the CArG box downstream of WUS. Mutations at this site increase locule number by 2−4[11]. Overexpression of WUS phenocopies the lc mutant, increasing floral organ number[12], while silencing SlWUS reduces flower size and locule count, confirming its central role in organogenesis[13]. Originally, the fas mutant phenotype was attributed to loss-of-function of a YABBY transcription factor[14]. However, subsequent studies identified a 294 kb chromosomal inversion spanning from the YABBY intron to 1 kb upstream of CLAVATA3 (CLV3), which disrupts the SlCLV3 promoter and increases locule number by 6−8 in fas mutants[15].

Stem cell dynamics and regulatory networks

-

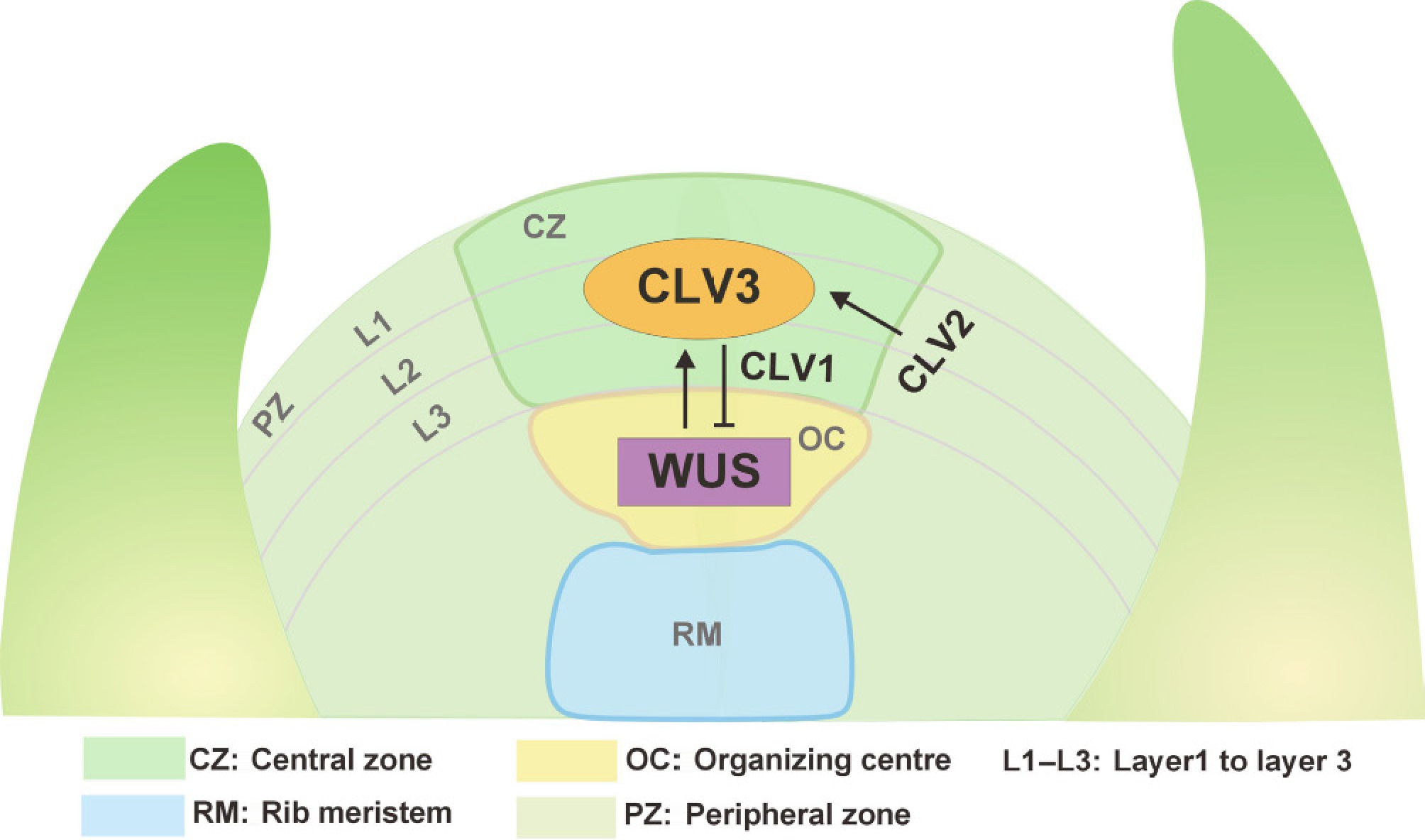

Recent studies link locule formation to stem cell differentiation in the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and FM. The SAM, a dome-shaped structure (Fig. 1), comprises three histologically distinct cell layers (L1−L3) that differentiate into epidermal, ground, and vascular tissues. Functionally, the SAM is divided into three zones which include central zone (CZ), peripheral zone (PZ), and rib zone (RZ). The central zone (CZ), located at the summit, harbors slowly dividing pluripotent stem cells. Surrounding the CZ is the peripheral zone (PZ), where cells undergo rapid division to generate leaf primordia or axillary meristems, serving as the core region for lateral organ development. Below the CZ, the rib zone (RZ) consists of cells that divide to form stem tissues. The CZ continuously supplies stem cells to the PZ and RZ. Between these zones lies the organizing center (OC), a signaling hub critical for maintaining stem cell homeostasis[16].

Figure 1.

The CLAVATA3-WUSCHEL negative feedback loop in the shoot meristem. The SAM is composed of three cell layers (L1−L3) and can be divided into distinct functional domains based on its functional and cytological characteristics. These domains include the central zone (CZ), peripheral zone (PZ), organizing center (OC), and rib meristem (RM). The transcription factor WUS is specifically expressed in the OC. Its expression is suppressed by a signaling cascade involving the small peptide CLV3, which binds to the transmembrane receptor kinase CLV1, and the receptor-like protein CLV2. Under normal conditions, the WUS protein moves from the OC to the CZ, where it activates CLV3 expression to inhibit its own activity, thereby ensuring proper growth volume in the plant. Consequently, these components form a feedback loop within the SAM that balances stem cell maintenance and cell differentiation.

The CLV-WUS axis acts as a self-correcting rheostat: WUS protein migrates from the organizing center to activate CLV3 in the stem cell zone, while CLV3 peptides diffuse downward to repress WUS, dynamically balancing stem cell renewal and differentiation (Fig. 1)[17]. This pathway relies on interactions among spatially restricted receptors, ligands, and transcription factors. This regulatory circuit involves two core components: the homeodomain-type WUS gene, encoding a homeodomain transcription factor essential for maintaining SAM stem cells in an undifferentiated state; and the CLV3 gene, which produces a mature 13-amino-acid peptide. This small signaling peptide translocates between adjacent cells via plasmodesmata and undergoes post-translational modifications such as hydroxylation or arabinosylation. CLV3 suppresses stem cell proliferation across diverse plant species. The CLV-WUS signaling pathway maintains SAM homeostasis by dynamically balancing stem cell maintenance and differentiation[18]. In tomato, the slclv3 mutant exhibited a significantly enlarged SAM with fruit locule number increase to 11. In contrast, the slwus mutant displayed floral organ defects characterized by the absence of carpel structures. Notably, upregulation of SlWUS gene expression resulted in a significant increase in floral organ number. Previous studies have demonstrated that the WUS-CLV3 module influences tomato fruit size by modulating locule number. Elevated WUS expression promotes cell division, leading to SAM expansion and ultimately contributing to the formation of multilocular fruits[19].

Expanded genetic regulation: two additional loci, Fasciated and branched (FAB) and Fasciated inflorescence (FIN), regulate tomato locule number. FAB encodes CLV1, a receptor kinase for CLV3, while FIN encodes an arabinosyltransferase that modifies CLV3. Genetic analyses show that both fin and fab mutants modulate locule number through the CLV3 pathway. CLV1, a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK), is expressed below the CZ and around the WUS domain. CLV3 signaling is perceived by CLV1 and a heteromeric complex containing CLV2, a receptor-like protein, coordinating stem cell dynamics via the conserved CLV3-WUS loop[20].

Compensatory mechanisms

-

Intriguingly, studies of multilocular tomato mutants have uncovered a compensatory role for SlCLE9 when SlCLV3 function is compromised[21]. The functional interplay between key genetic components was further elucidated through research demonstrating that tomato plants subjected to precision editing of both the SlCLV3 promoter and the transcriptional repression domain downstream of SlWUS developed significantly enlarged fruits with increased locule numbers. This genetic engineering approach successfully modified meristem regulation to enhance fruit morphology characteristics[22]. Notably, while multiplex promoter editing of SlCLV3 created a gradient of locule proliferation in mutants, SlWUS remained remarkably resistant to promoter perturbations[23,24]. Mechanistically, the functional loss of SlCLV3 activates its paralog SlCLE9 through transcriptional reinforcement, an elegant genetic compensation strategy that preserves developmental redundancy within the system[25,26]. Collectively, these breakthroughs establish that the CLV3-WUS feedback loop maintains developmental control through dual regulatory axes: gene dosage sensitivity and compensatory genetic networks. This paradigm ultimately positions transcriptional precision in the CLV3-WUS circuit as the master regulator of locule patterning, demonstrating that precise transcriptional regulation of this circuit fundamentally shapes tomato fruit architecture[27].

AG-WUS feedback loop regulates locule number via floral meristem termination

-

The FM, which differentiates from the SAM, shares structural similarities with the SAM but follows a distinct developmental path. Unlike the SAM, the FM undergoes termination of stem cell activity after differentiation, during which the positional arrangement and developmental sequence of floral organ whorls are determined[28]. Consequently, floral stem cells produce a defined number of organs before exiting their pluripotent state. Notably, locules originate directly from carpels within the flower. Locule formation is linked to carpel development, with carpel number dictating the final locule count[29]. The number of carpels generated by the FM directly dictates the resultant locule number, a process finalized during FM termination, the developmental phase marked by the irreversible cessation of stem cell activity[30].

Dual regulation of FM determinance by AG-WUS

-

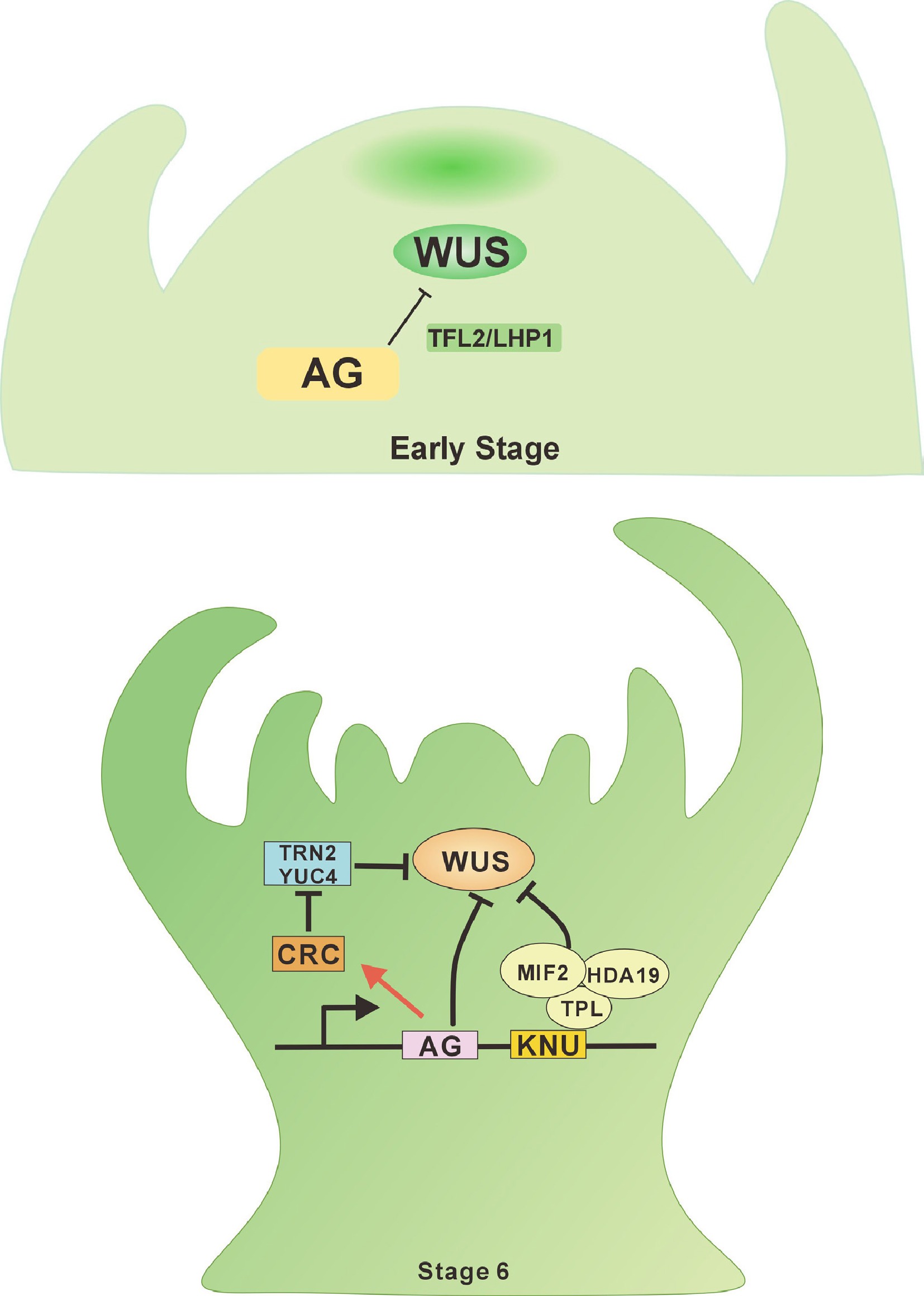

The transcription factor WUS maintains stem cell activity in the SAM and FM[31]. The spatial distribution of the WUS protein determines stem cell activity; thus, timely termination of WUS expression in the FM ensures orderly differentiation. WUS positively regulates the expression of AG[32]. AG, a critical regulator of floral stem cells, is required for terminating normal floral development by repressing the expression of the stem cell determinant WUS[33]. AG orchestrates floral determinacy by repressing WUS through two synergistic mechanisms (Fig. 2). (1) Epigenetic silencing via polycomb recruitment: during early FM termination, AG directly recruits Polycomb Group (PcG) proteins TERMINAL FLOWER2 (TFL2), and LIKE HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN1 (LHP1) to epigenetically silence WUS expression via histone modification, thereby terminating floral stem cell pluripotency. (2) Chromatin remodeling through KNUCKLES (KNU) Activation: at stage 6 of flower development, AG indirectly downregulates WUS by activating the transcription factor KNU, which disrupts stem cell maintenance through chromatin remodeling or competitive DNA binding[34]. KNU, encoding a C2H2-type zinc finger protein, is transcriptionally activated by AG. This activation involves the delayed induction of histone-based epigenetic modifications at the KNU locus. Upon induction, KNU binds to the WUS promoter, displacing SPLAYED (SYD), a chromatin-remodeling factor required for WUS activation. Concurrently, KNU facilitates the deposition of H3K27me3, thereby establishing Polycomb-mediated repression of WUS[35]. Additionally, AG positively regulates the expression of MINI ZINC FINGER2 (MIF2) during floral development. MIF2 forms a transcriptional repressor complex with KNU, the transcriptional corepressor TOPLESS (TPL), and the chromatin remodeler HISTONE DEACETYLASE19 (HDA19). Within this complex, MIF2 binds to the WUS locus and mediates its epigenetic silencing through histone deacetylation[30].

Figure 2.

AGAMOUS-WUSCHEL signaling in the flower meristem. During the early stages of floral development, AG directly represses the WUS gene by recruiting the Polycomb Group (PcG) protein TFL2/LHP1 in the initial phase of floral meristem (FM) termination, thereby terminating floral stem cell fate. At stage 6 of floral development, AG activates the expression of CRC and KNU, which indirectly suppress WUS, ensuring FM determinacy.

Auxin-cytokinin crosstalk in FM termination

-

AG indirectly suppresses WUS expression through another critical downstream target, the YABBY transcription factor CRABS CLAW (CRC). CRC regulates auxin homeostasis by directly repressing TORNADO2 (TRN2), thereby establishing an auxin maximum during carpel primordia initiation[36]. This auxin maximum reduces FM activity, inhibits WUS expression, and promotes subsequent gynoecium formation[37]. Recent studies reveal that KNU also modulates auxin and cytokinin levels at stage 6, indirectly suppressing WUS expression to ensure robust FM termination[38].

Additional regulatory factors influencing tomato locule number

-

Multiple regulatory factors interact with the CLV3-WUS pathway to control tomato locule number (Table 1). For instance, SlENO (EXCESSIVE NUMBER OF FLORAL ORGANS), identified from mutants with supernumerary floral organs, encodes an AP2/ERF transcription factor that directly binds to the SlWUS promoter to suppress its expression. sleno mutations elevate SlWUS transcript levels, resulting in increased locule counts[39,40]. Similarly, the transcriptional repressor SlBES1.8 (BRI1-EMS- SUPPRESSOR 1) forms heterodimers with SlWUS, blocking its ability to activate SlCLV3 and other targets. While slbes1.8 mutants show no visible defects, overexpressing SlBES1.8 expands the SAM and produces pepper-shaped fruits with excessive floral organs[41]. Another regulator, SlTPL3, modulates locule numbers by forming a co-repressor complex with WUS. Silencing SlTPL3 increases floral organ and locule numbers, accompanied by synchronized upregulation of WUS and CLV3 transcripts[42,43]. Additionally, auxin signaling components SlARF8A and SlARF8B promote locule and placental development. These factors are inhibited by sly-miR167, which activates auxin-responsive genes. Mutations in SlARF8A/B reduce free IAA levels but accumulate inactive IAA conjugates (e.g., IAA-Ala). SlARF8B directly represses SlGH3.4, an enzyme conjugating auxin to amino acids. Disrupting this balance via SlGH3.4 overexpression causes locule malformations[44].

Table 1. Determinants regulating locule number in tomato.

Locus/gene (gene number) Chromosomal location Mechanism Mutant phenotype SlCLV3 (Solyc11g071380) Chromosome 11 The mutation of the CArG element downstream of SlWUS results in the loss of repressive function,

leading to the upregulation of WUS expression and affecting the WUS-CLV3 pathway.The number of locules increases by 2 to 4. SlWUS (Solyc02g083950) Chromosome 2 A 294 kb inversion upstream of the SlCLV3 gene disrupts the SlCLV3 promoter, and this mutation affects the WUS-CLV3 pathway. The number of locules increases by 6 to 15. Fab (Solyc04g081590) Chromosome 4 The FAB gene encodes CLV1, a receptor kinase for CLV3. Mutations in FAB can suppress the transcription

of SlCLV3, thereby affecting the WUS-CLV3 pathway.Increase the number of locules. Fin (Solyc11g064850) Chromosome 11 The FIN gene encodes an arabinosyltransferase responsible for the post-translational modification of CLV3. Mutations in FIN can suppress the transcription of SlCLV3, thereby affecting the WUS-CLV3 pathway. Increase the number of locules. SlTPL3 (Solyc01g100050) Chromosome 1 SITPL3 and SIWUS regulate the multicentric phenotype by negatively regulating IAA and positively regulating GA. The shoot apical meristem enlarges, and the number of locules increases. SlENO (Solyc03g117230) Chromosome 3 ENO can interact with the GGC-box cis-regulatory element in the promoter region of SlWUS, directly regulating the expression of SlWUS. The number of flower organs and fruit locules increase. SlIMA (Solyc02g087970) Chromosome 2 SlIMA can assemble with SlKNU, SlTPL1, and HAD19 to form a transcriptional repression complex that suppresses WUS expression. Increase the number of locules. SIBES1.8 (Solyc10g76390) Chromosome 10 SlBES1.8 suppresses the DNA-binding ability of SlWUS by forming a heterodimer through interaction

with it.The shoot apical meristem enlarges, and the number of locules increases. SlKNU (Solyc02g160370) Chromosome 2 SlKNU can assemble with SlMIF2, SlTPL1, and HAD19 to form a transcriptional repression complex that suppresses WUS expression. The number of flower organs and fruit locule increase. SlCLE9 (Solyc06g074060) Chromosome 6 SlCLE9 compensates for the loss of SlCLV3 function by binding to SlWUS, and its mutation exacerbates

the phenotypic defects in SlCLV3 mutants.Increase the number of locules. SlCRCa (Solyc01g010240) Chromosome 1 SlCRCa and SlCRCb bind to chromatin remodeling complex components, thereby suppressing SlWUS expression and promoting floral meristem determinacy. Increase the number of locules. SlCRCb (Solyc05g012050) Chromosome 5 SlCRCa and SlCRCb bind to chromatin remodeling complex components, thereby suppressing SlWUS expression and promoting floral meristem determinacy. Increase the number of locules. -

Research since the 1960s reveals that tomato locular formation results from both environmental conditions and genetic factors. While multiple stressors affect locular abnormal development, two elements dominate during early flower formation: (1) extreme temperatures/light changes; and (2) hormonal imbalances (particularly auxin or gibberellin levels). Environmental stresses modulate locule formation through both direct physiological effects and indirect interactions with genetic networks. The following sections dissect how temperature, light, water, and nutrients influence malformation risks.

Temperature effects on tomato malformation

-

Tomato plants, being highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations, develop multilocular malformed fruits through distinct mechanisms under cold and heat stress. Studies demonstrate that low night temperature stress during the seedling stage significantly increases both locule number and malformed fruit rate, with the latter exceeding 50%. The floral bud differentiation phase was identified as the critical developmental phase for low-temperature-induced malformation, with threshold night temperatures of 6−12 °C triggering substantial malformed fruit production. Experimental evidence indicates that 6 °C night temperature treatment initiated at the first true leaf expansion stage dramatically promotes malformed fruit formation, showing a negative correlation between seedling-stage night temperature and malformation rate. Specifically, temperatures below 12 °C induce exponentially higher malformation rates while increasing night temperatures substantially reduce malformation susceptibility[45].

Mechanistically, low night temperatures during seedling development elevate endogenous levels of gibberellins (GA), cytokinins (CK), and ethylene (ET) in the shoot apical meristem of the first inflorescence[46]. This phytohormonal imbalance potentially disrupts the CLV-WUS regulatory network, thereby altering carpel primordium initiation patterns. Further investigation into the mechanisms underlying low-temperature-induced tomato locule number variation revealed that the duration of low-temperature stress exhibits a significant positive correlation with the rate of malformed fruits. In addition to suppressing the transcriptional activity of SlWUS, SlCLV3, and TAG1, low temperature also establishes a hormone-facilitated microenvironment conducive to callose deposition in the floral meristem (FM) by inhibiting GA accumulation and promoting abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis. This hormonal imbalance leads to complete obstruction of the symplastic pathway throughout floral tissues under low-temperature stress. Upon gradual temperature recovery, stem cell activity is gradually restored. However, the delayed normalization of GA and ABA levels in the FM prevents timely callose degradation. This directly restricts the movement of SlWUS protein from the organizing center (OC) to the central zone (CZ) via plasmodesmata, thereby disrupting the feedback activation of SlCLV3 and TAG1. Consequently, aberrant upregulation of SlWUS occurs during the recovery stage ultimately manifesting as the multi-locule malformation phenotype[47].

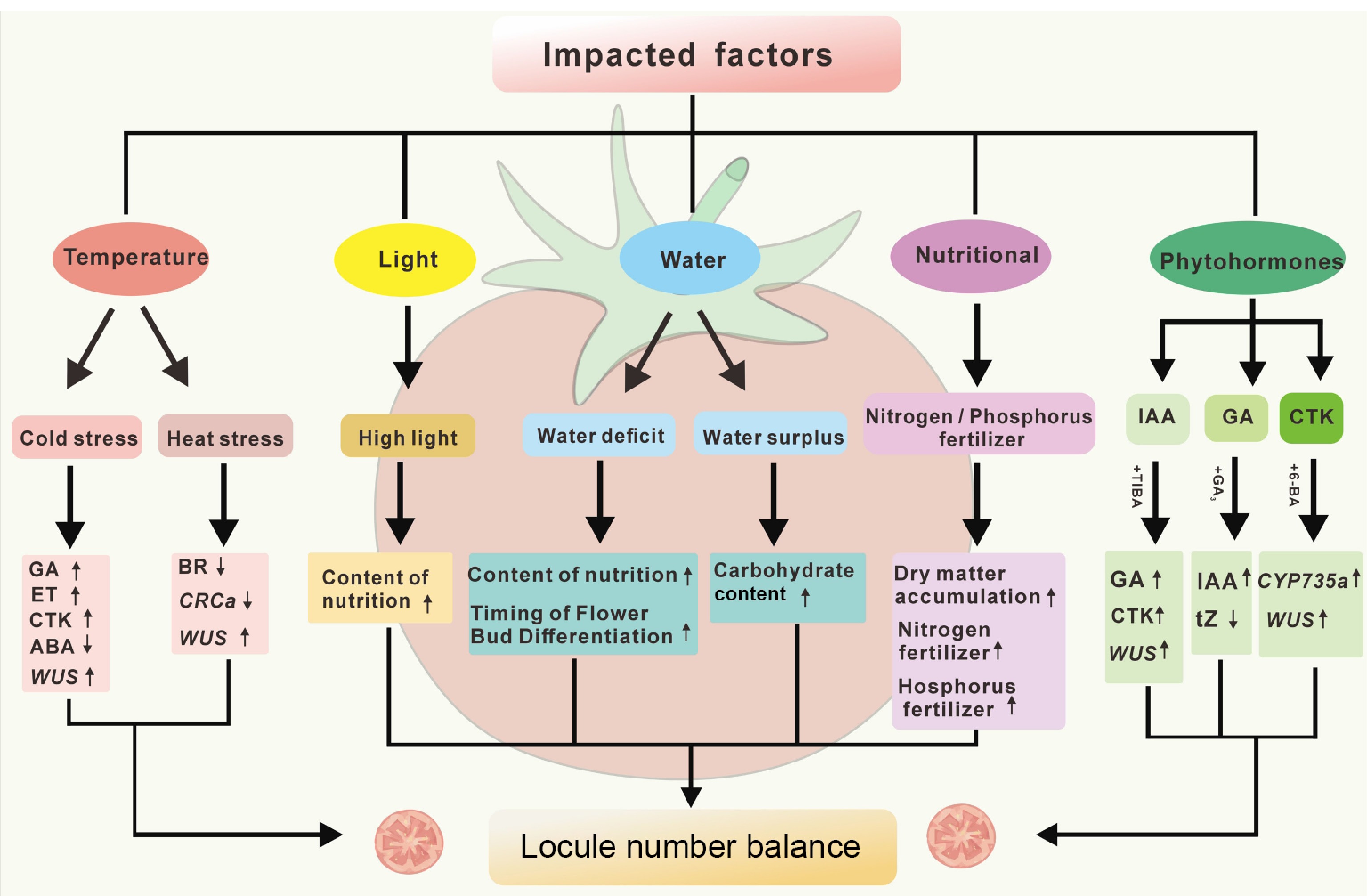

Furthermore, high-temperature stress can also cause tomatoes to develop multi-locule deformed fruits, directly harming the commercial quality and yield of the tomatoes. Research shows that transient high-temperature stress can induce abnormal upregulation of SlWUS expression, preventing stem cells in the FM from termination promptly, leading to fruit deformity. Additionally, under high-temperature stress (HS), the biosynthesis of BR and the expression of SlCRCa in the FM are inhibited, which preserves the activity of SlWUS and disrupts the termination of the FM, ultimately resulting in the formation of multi-locule deformed tomatoes (Fig. 3)[48].

Figure 3.

Critical factors in abnormal fruit development. This diagram summarizes the key factors influencing tomato malformed fruit formation (temperature, light, water, nutrients, and phytohormones), which lead to changes in the levels of GA (gibberellins), CK (cytokinins), ET (ethylene), ABA (abscisic acid), tZ (trans-zeatin), WUS (wuschel), and CRCa (CRABS CLAWa). The upward and downward arrows indicate the increase or decrease of hormone levels, gene expression, or physiological indicators under specific conditions.

Light intensity effects on tomato malformation

-

Tomato is a sun-loving crop. It has been reported that the occurrence of tomato malformed fruits is associated with light intensity. This relationship may be primarily mediated through the accumulation of soluble proteins, soluble sugars, and starch at the shoot apex of seedlings. Specifically, a reduction in the accumulation of these compounds at the seedling shoot apex correlates with a decrease in both the frequency and severity of deformed fruits[49]. However, excessively high light intensity during the seedling stage leads to over-differentiated floral buds, thereby increasing the occurrence of malformed fruits. For instance, upon enhanced light exposure during the seedling stage, the proportion of abnormal flowers will be significantly elevated in the primary inflorescence, while its impact on the secondary inflorescence is less pronounced[50]. Further studies indicate that weak light during the seedling stage can reduce the frequency of malformed fruits by decreasing the number of locules in tomato fruits. When shading reaches 32%, the occurrence of malformed fruits decreases significantly. Under ambient temperatures of 25–29 °C, reducing light intensity from 35,000 Lux to 30,000 Lux has been shown to markedly lower the malformed fruit rate (Fig. 3)[51].

Water condition effects on tomato malformation

-

Tomatoes require precise water adjustments across growth phases to prevent fruit malformation. Young seedlings develop stronger roots and produce more normal fruits when grown under mild water stress[52]. Excessive soil moisture at this stage, particularly under low-temperature conditions, may induce the formation of double-layer flowers, ultimately leading to malformed fruits. In contrast, reduced soil moisture minimizes the risk of double-layer flowers even under low-temperature stress. In the mid-to-late growth stages, elevated soil moisture levels can increase carbohydrate accumulation within tomato plants, thereby potentially resulting in multilocular fruits. Conversely, severe water deficit during the flowering and fruit-setting period may lead to undersized or malformed fruits[53]. Furthermore, irrigation scheduling significantly influences malformed fruit formation. Studies demonstrate that adjusting irrigation intervals has an impact on both the frequency and severity of malformed fruits. Shortening the irrigation interval notably reduces the malformed fruit rate, while also alleviating the types and extent of deformities (Fig. 3)[54].

Nutritional effects on tomato malformation

-

Excess nutrients during tomato growth often trigger multi-locule fruits by overloading plants with dry matter, while uneven fruit development raises deformity risks. Therefore, in agricultural production, it is recommended to prioritize organic fertilizers and ensure a balanced ratio of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) when applying inorganic fertilizers, while avoiding excessive nitrogen supplementation. Notably, during the seedling stage, surplus nitrogen and phosphorus availability increases both the frequency and severity of malformed fruits, particularly under low-temperature conditions. Adequate nutrient supply promotes seedling growth. However, lower nighttime temperatures (6–10 °C) can suppress plant growth, leading to shorter internodes, thicker stems, and expanded leaf area, thereby stronger seedlings. Additionally, low temperatures reduce the growth rate of the shoot apex and decrease respiratory consumption of nutrients, redirecting more assimilates to floral buds. Under such conditions, prolonged exposure to high nutrient concentrations in floral buds stimulates excessive cell division, resulting in an increased number of locules and a higher rate of malformed fruits (Fig. 3)[45]. Thus, optimizing nutrient management and temperature control is critical for minimizing tomato malformation.

Plant hormone effects on tomato malformation

-

During tomato floral bud differentiation, the application of different phytohormones significantly influence floral organ quantity and fruit locule formation. Gibberellins (GAs) promote somatic cell division and elongation, thereby increasing floral organ numbers. Studies demonstrate that exogenous GA3 application markedly enhances ovary locule numbers in tomatoes. As a key regulator of locule formation, gibberellins may function by facilitating nutrient translocation and participating in cellular differentiation processes[55,56]. Auxins also modulate the development of tomato locules. Exogenous treatments with 2,4-D or NAA reduce ovary locule numbers and malformed fruit rate. NAA application significantly elevates endogenous auxin levels in shoot apices while suppressing gibberellin and cytokinin concentrations. Cytokinins positively regulate locule formation. Under low temperatures (10 °C), tomato ovaries exhibit increased locule numbers alongside elevated cytokinin levels in shoot apices. Exogenous cytokinins (e.g., iP and ZR) further enhance locule numbers, with more pronounced effects in multilocular cultivars compared to few-locular ones. This differential response may result from the higher expression of CYP735A1, a key enzyme in cytokinin biosynthesis, in multilocular cultivars[57]. Additionally, other phytohormones such as ethephon have been shown to exacerbate both the frequency and severity of malformed fruits (Fig. 3)[58,59].

-

Fruit locule number critically determines crop yield and quality by shaping fruit size, structure, and marketability. Recent research extends beyond tomatoes to key crops like cucumber, maize, rapeseed, and melon, revealing conserved and species-specific regulatory mechanisms. In cucumber (Cucumis sativus), locule number strongly predicts fruit weight and shape, key factors for yield and consumer appeal. Larger locule counts correlate with wider fruits and altered flavor profiles. Two chromosome 1 QTLs, ln1.1 and ln1.3, drive multilocular traits[60,61]. Maize leverages locule variation through the FEA3 receptor, which modulates stem cell activity via CLE peptides. fea3 mutants produce longer ears with more kernel rows, directly boosting yield potential[62,63]. Rapeseed (Brassica napus) links silique locules to seed count, a vital yield determinant. Multilocular varieties show dual benefits: higher seed numbers and enhanced disease resistance. The Bra034340 gene (a CLV3 homolog) controls locule number in Brassica rapa by regulating silique width[64,65] Melon (Cucumis melo) demonstrates a locule-morphology tradeoff: 3-locular fruits are typically elongated, while 5-locular types trend spherical. Increased locules expand fruit width but raise environmental deformity risks. The CmCLV3 gene emerged as a dual regulator of locule number and fruit shape through GWAS[66,67].

-

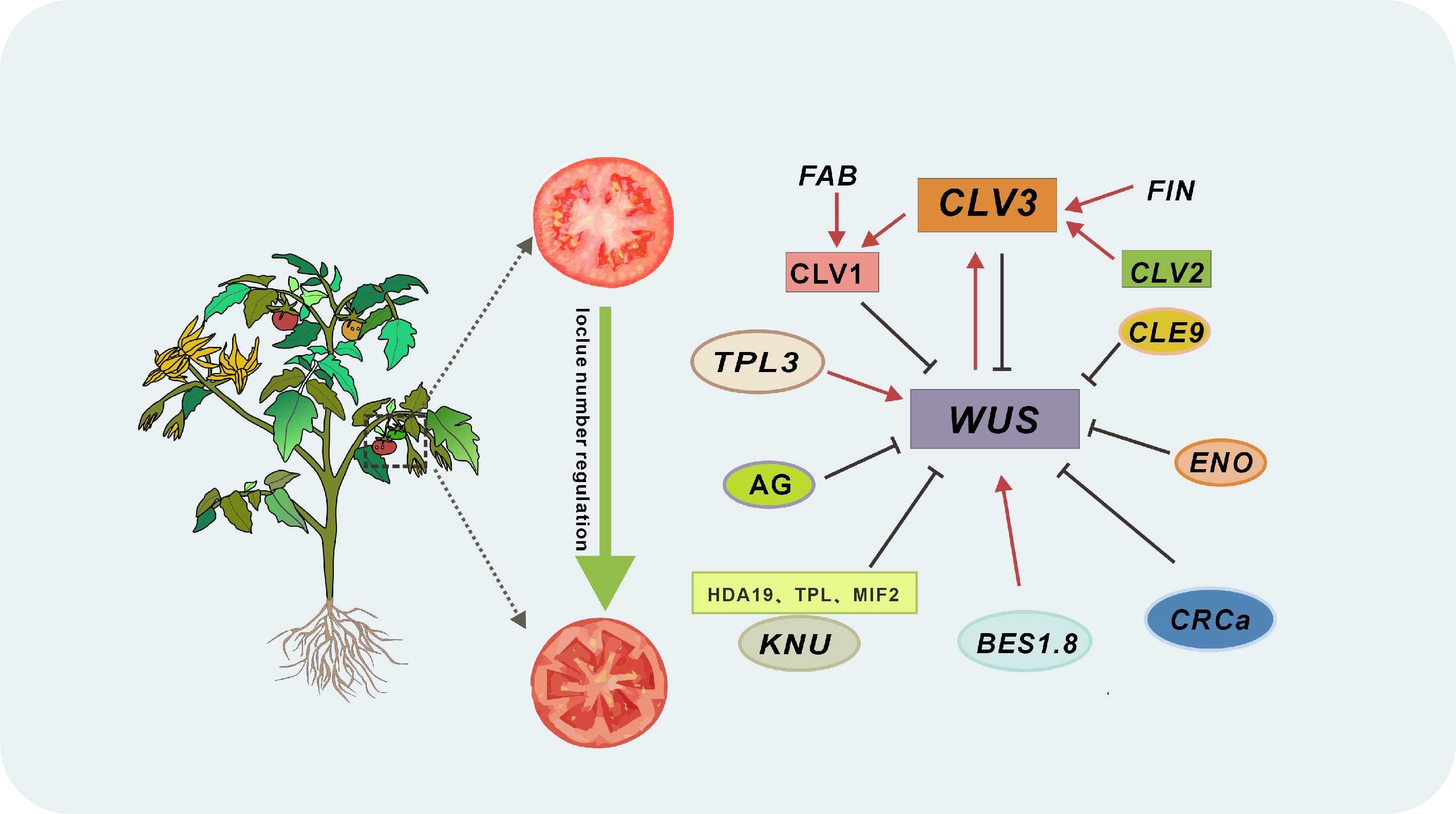

Decades of research have decoded the genetic and environmental controls behind tomato locule formation, establishing multilocular fruit development as a model for studying stem cell regulation in crops. We now recognize locule number, a critical agronomic trait governing fruit size, morphology, and yield, as emerging from dynamic interactions between environmental cues (temperature, light, water, nutrients, hormones) and genetic networks. Central to this system is the evolutionarily conserved CLV3-WUS feedback loop, which maintains stem cell balance in meristems through precise molecular choreography (Fig. 4). Recent breakthroughs, like SlKNU mutant analyses showing 30%−50% increases in floral organs and locules, reveal the network's exquisite sensitivity to genetic perturbation.

Figure 4.

Integrated networks controlling locule number in tomato. In the plant stem cell regulatory network, CLV1 (encoded by FAB) acts as the receptor kinase for the CLV3 peptide, FIN encodes an arabinosyltransferase that modifies CLV3, collaborating with CLV1 to form a core pathway suppressing WUS activity. When CLV3 is dysfunctional, SlCLE9 activates a partial compensatory mechanism to sustain WUS inhibition. This network integrates multi-tiered transcriptional control: SlENO (an AP2/ERF transcription factor) directly represses SlWUS by binding its promoter; SlBES1.8 sequesters SlWUS via heterodimerization, blocking its interaction with the SlCLV3 promoter and other targets; SlTPL3 partners with WUS to form a transcriptional co-repressor complex, silencing ventricular development-related genes; and AG employs a dual strategy, directly inhibiting WUS in early floral stages, then activating CRCa and KNU at stage 6 to enforce cascade suppression. Arrows denote activation; lines indicate inhibition.

Future efforts should map how environmental stressors reshape locule determination through epigenetic pathways, particularly temperature-induced DNA methylation patterns at SlWUS regulatory regions and histone acetylation-mediated chromatin remodeling. Parallel CRISPR screening of CLV3-WUS pathway components could accelerate the breeding of compact, stress-tolerant varieties with optimized locule counts, bridging fundamental discovery with agricultural innovation.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372716, 32202576, 31902013, and 31870286), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515012674, 2023A1515010497, 2022A1515012278, and 2021A1515010528).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: data collection: Huang C, Yao Y, Yang X, Zeng Z, Zhang X, Hu H, Xia R, Wang HC; figure preparation: Huang C, Liang Y; draft manuscript preparation: Huang C, Hao Y; manuscript revision: all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

No data was used for the research described in the article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Huang C, Yao Y, Liang Y, Yang X, Zhang X, et al. 2025. From stem cell dynamics to field phenotypes: genetic and environmental factors in tomato multilocular malformation. Plant Hormones 1: e012 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0012

From stem cell dynamics to field phenotypes: genetic and environmental factors in tomato multilocular malformation

- Received: 02 April 2025

- Revised: 30 April 2025

- Accepted: 19 May 2025

- Published online: 25 June 2025

Abstract: This comprehensive review examines the etiology of multilocular fruit deformities and how they are influenced by both genetic factors, like the CLV3-WUS feedback loop, and environmental stressors such as extreme temperatures and fluctuating light levels. The study also sheds light on molecular pathways that control key developmental stages: differentiation of carpel primordia and termination of floral meristems. By linking detailed mechanisms with observed traits, this research seeks to connect basic plant development science with practical farming techniques. In particular, it offers a theoretical basis for identifying molecular targets to enhance genetic resilience against environmental perturbations and optimizing cultivation protocols to mitigate fruit malformation under suboptimal growing conditions.