-

The greater yam (Dioscorea alata L.) is one of the most widely cultivated yams worldwide. As its cultivation area continues to expand annually, diseases have become a key factor limiting the development of the greater yam industry. Among these diseases, anthracnose stands out as a major threat to greater yam production, often causing significant yield reductions or even complete crop failure in severe cases[1−3]. It has been reported that the pathogens causing yam anthracnose primarily belong to the genus Colletotrichum within the Ascomycota subdivision. In China, the main pathogens reported to cause anthracnose in yam are C. capsici and C. gloeosporioides. However, there is relatively little research on the pathogen causing anthracnose in greater yam, indicating a need for further investigation[3−7].

Currently, the primary method for preventing and controlling anthracnose in greater yam cultivation is chemical control. While this approach is indeed efficient, rapid, convenient for large-scale application, and cost-effective, its prolonged use poses risks such as environmental contamination, increased pathogen resistance to fungicides, and the potential for chemical residue accumulation. These residues can lead to poisoning in both humans and animals. Consequently, there is an urgent need to expedite the selection and development of high-quality, disease-resistant greater yam varieties as the most effective strategy for managing anthracnose in greater yams[8].

Plants are equipped with sophisticated immune systems capable of swiftly detecting and responding to pathogen invasions. As a lipid compound, wax on the leaf surface can diminish the rate of transpiration and shield mesophyll cells from microbial invasions[9−11]. Furthermore, stomata play a key role in plant resistance to adverse external environments and pathogen attacks. Upon pathogen infection, the stomatal aperture in plants may reduce or even close, triggering a natural defense mechanism[12,13]. Research indicates that abscisic acid (ABA) can protect against pathogen incursions by modulating stomatal movement. A reduction in the internal ABA levels in plants hinders their ability to swiftly shut their stomata, highlighting the crucial role of ABA in stomatal defense responses[14,15]. Therefore, plants utilize ABA to regulate stomatal closure, forming a critical barrier against pathogen invasion[16]. Additionally, when plants are infected by pathogens, they trigger a cascade of defense responses, leading to alterations in defensive enzymes such as peroxidase (POD), phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), and polyphenol oxidase (PPO)[17−23].

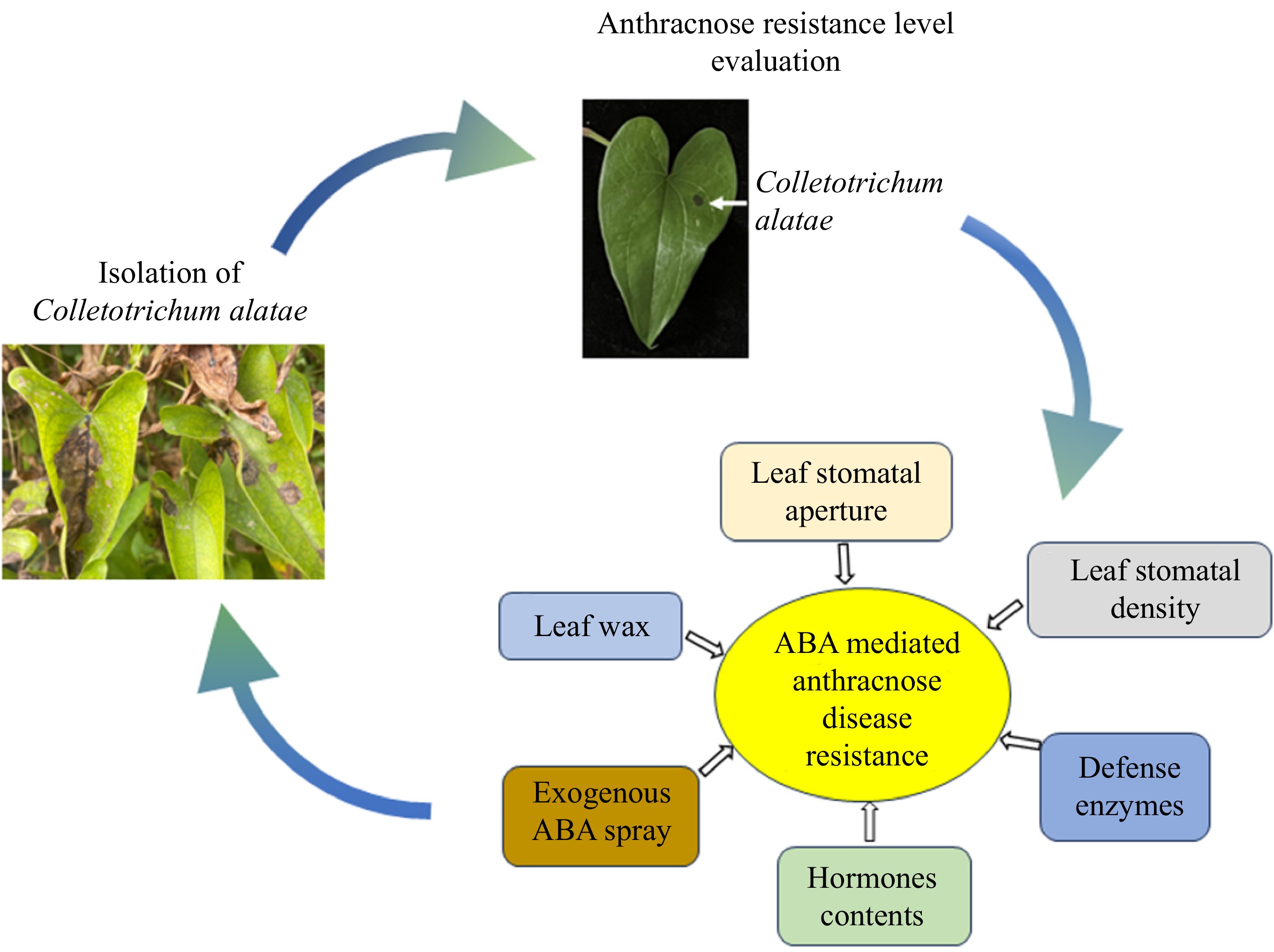

This study aimed to isolate, purify, and identify the pathogenic bacteria causing anthracnose in the greater yam planting in the plantation of Jiangxi Agricultural University (Nanchang, China). Additionally, the study aimed to assess the resistance of greater yam varieties to anthracnose through in vitro inoculation and to explore the physiological correlates associated with varying levels of resistance among the varieties. By comparing and analyzing biochemical and molecular indicators, the study sought to clarify the physiological mechanisms underlying resistance to anthracnose in greater yams. Furthermore, an ABA spray test was conducted to confirm the role of abscisic acid (ABA) in enhancing the resistance of greater yams to anthracnose. The findings of this research not only offer foundational material and theoretical support for breeding greater yams resistant to anthracnose but also serve as a reference for developing biological control strategies. These outcomes are highly significant for the development of anthracnose-resistant greater yam varieties and the advancement of biological control technologies.

-

Forty-six greater yam varieties were collected from Jiangxi, Yunnan, Guangzhou, Fujian, and Sichuan Provinces, China (Supplementary Table S1). Based on the subsequent evaluation of anthracnose resistance levels and the disease index of 46 greater yam varieties, immune variety D28, resistant variety D284, and susceptible variety D404 were selected as representatives for the analysis of stomata, wax, defense enzymes, hormones, and gene expression.

Isolation and identification of the anthracnose pathogen

-

The cultured colonies were retrieved from the incubator, and their morphological traits were examined[24]. On the basis of the observations of the size, color, spore color, and density of the colonies and hyphae in the Petri dishes, strains were preliminarily identified following morphological identification and were further confirmed through multigene sequence analysis. A suitable quantity of hyphae was collected from the colonies at the optimal age using an inoculation needle, and any excess water was absorbed on sterile filter paper. The hyphae were then ground in a mortar, and DNA was extracted using the Fungal DNA Extraction Kit (Sangon Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The PCR primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The purified products were sequenced (Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and Calmodulin (CAL) sequences were used to conduct comparative analyses in the NCBI database.

Evaluation of anthracnose resistance in greater yam varieties

-

The anthracnose resistance of greater yam varieties was evaluated through manual in vitro inoculation. Porcelain plates, measuring 40 cm by 60 cm, were initially sprayed with alcohol and then washed with sterile water twice. Absorbent paper was evenly laid at the bottom of the plates to maintain moisture, and a hollow plastic grid frame was placed on top of each plate. Finally, leaves from various greater yam varieties were collected, and inoculated, and their surfaces were scrubbed with 75% alcohol, dried, and then rinsed with sterile water to remove any non-toxic bacteria. A bacterial needle was used to puncture four to five holes on either side of the leaf veins. A blank medium was cut out with a punch (diameter = 5 mm) and placed at the puncture site on the left side of the leaf vein to serve as a control group. Hyphal blocks were taken from the edge of a colony and placed into the puncture wounds on the right side of the leaf veins, corresponding to the treatment group. Cotton balls soaked in 75% alcohol were placed on both the left and right media to prevent external bacterial contamination. Each sample was replicated three times. Finally, the inoculated leaves were placed on a grid shelf within a porcelain dish, covered with plastic wrap, and the dishes were uniformly incubated at a relative humidity of 95%–100% and a temperature of 26 °C.

Measurement of the disease index

-

The inoculated leaves were incubated in an incubator (temperature: 26 °C, humidity: 95%–100%) in the dark for 24 h and then cultured under normal light for 7 d. The cotton was removed after 2 dpi (days post inoculation). Disease assessments were conducted every other day throughout the incubation period. The severity of the disease was categorized into grades 1 through 7 based on the estimated percentage of lesion area observed on the leaves relative to the total leaf surface area (grade 1 = 0.1%–5%; grade 2 = 5.1%–15%; grade 3 = 15.1%–30%; grade 4 = 30.1%–45%; grade 5 = 45.1%–65%; grade 6 = 65.1%–85%; grade 7 = 85.1%–100% in Table 1). The lesion area was calculated by Image J software. The criteria for grading anthracnose resistance in greater yam were based on the numerical rating scale proposed by Williams with slight modifications[25], and the severity index (SI) was calculated using the formula provided therein. The evaluation criteria for the resistance of greater yam to anthracnose are presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Classification criteria for the identification of resistance to anthracnose in Dioscorea alata L.

Grading criteria for resistance Percentage of lesions (%) 1 0.1 < Percentage of lesions ≤ 5 2 5.1 < Percentage of lesions ≤ 15 3 15.1 < Percentage of lesions ≤ 30 4 30.1 < Percentage of lesions ≤ 45 5 45.1 < Percentage of lesions ≤ 65 6 65.1 < Percentage of lesions ≤ 85 7 85.1 < Percentage of lesions ≤ 100 Table 2. Evaluation criteria for the resistance of Dioscorea alata L. to anthracnose disease.

Severity index (SI) Resistance evaluation SI = 0 Immunity (I) 0 < SI ≤ 3 Highly resistant (HR) 3 < SI ≤ 10 Resistant (R) 10 < SI ≤ 30 Susceptible (S) SI > 30 Highly susceptible (HS) In the formula:

$\rm SI = [{\text Ʃ}(s \times n)/N \times S] \times 100 $ SI stands for Severity Index of Disease, s stands for grading criteria for resistance, n stands for the number of infected leaves at this level, N stands for the total number of leaves, S stands for highest level of grading criteria for resistance.

Measurement of leaf stomata

-

Healthy leaves from immune, disease-resistant, and susceptible varieties were selected from the greater yam cultivation in the plantation of Jiangxi Agricultural University (Nanchang, China). The surfaces of the leaves were wiped with distilled water. A leaf of approximately 2 mm × 2 mm in size was excised from the puncture wound area in Group 1 and fixed on a glass slide coated with nail polish. A thin layer of nail polish was then applied to the leaf piece. After 10 min, the leaf epidermis of the leaf was carefully removed using tweezers. The samples were subsequently transferred to fresh, clean slides, covered with coverslips, and observed under a microscope. For each variety, four random fields were selected and replicated to capture images and measure stomatal aperture. Following the manual in vitro inoculation method, leaves from greater yam plants representing the three resistance levels were inoculated with the pathogenic bacteria causing anthracnose. The stomatal aperture was calculated using the formula[12,13]: Stomatal aperture (μm2) = 0.5 height × 0.5 width × 3.14. Stomatal density was determined from the micrographs using the formula: Stomatal density = (Number of visible stomata)/(Square measure).

Scanning electron microscope

-

Two mm × 2 mm tissue sections were taken from greater yam leaves and immersed in a pre-chilled glutaraldehyde fixative solution (2.5% volume fraction, prepared with a 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer at pH 7.1) at 4 °C. Vacuum was applied for approximately 1 h until the sections were fully submerged in the fixative. The samples were allowed to fix at 4 °C for a minimum of 12 h, with a maximum duration not exceeding 4 d. The samples were rinsed twice with phosphate buffer solution (0.1 mol/L, pH 7.1) for 15 min each time. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to a graded ethanol dehydration series: 30%, 40%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100% for 15 min at each concentration. The samples were then dehydrated. After the dehydration process, the samples were dried at the critical point using CO2. A 15-s gold coating was applied using a vacuum ion sputtering instrument. Finally, the samples were examined using a scanning electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 25 kv in high vacuum mode.

Determination of the wax content of leaves

-

For the uniform fragments of the test tube, a clean glass funnel was positioned over a 15 mL test tube. Filter paper was placed inside the funnel, followed by the addition of leaf fragments. Then, 10 mL of chloroform was added for soaking. Once the filtrate had completely drained into the test tube, the funnel was removed, and the filtrate was transferred to a container for weighing. After the chloroform in the small test tubes had completely evaporated, the test tubes were reweighed. The total wax content in the leaves of each variety was determined by subtracting the initial weight of the corresponding empty test tube from the final weight. Each variety was subjected to this process three times to ensure replicability.

Determination of defense enzyme activities

-

POD activity was determined using the guaiacol method[26]. PAL activity was measured using a phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity assay kit (Shanghai Ji Ning Industrial Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). PPO activity was measured with a polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity assay kit (Shanghai Ji Ning Industrial Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The relative value of enzyme activity was calculated by comparing the enzyme activity in the treatment group to that in the control group using the following formula: Relative value of enzyme activity = Enzyme activity of treatment group/Enzyme activity of control group.

Determination of defense enzyme-encoding genes

-

The leaves of immune, resistant, and susceptible varieties were collected at 1, 3, and 5 dpi with anthracnose pathogen. RNA was extracted from these leaves using a Promega RNA extraction kit. Following reverse transcription with a kit (Yisheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Real-time PCR was performed using a mixture from Yisheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. in CFX Opus 96 (BIO-RAD Co., Ltd., CV, USA). The qPCR program was as follows: 95 °C for 2 min for initial denaturation, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The expression levels of genes encoding defense enzymes were detected, and the relative gene expression values were calculated using the following formulas. Relative value of gene expression = Gene expression of the treatment group/Gene expression of the control group. For details on primers, refer to Supplementary Table S2.

Determination of hormone content

-

Hormone levels were measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method[27]. Samples were collected at 1, 3, and 5 dpi from immune, resistant, and susceptible greater yam varieties inoculated with anthracnose pathogen. The aim was to determine the variation trend in the content of the hormone indole acetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid-me (JA-me), trans-Zeatin-riboside (ZR), brassinosteroids (BR), N6-isopentenyladenine (iPA), gibberellin 4 (GA4), DL-dihidrozeatin riboside (DHZR), and gibberellin 3 (GA3) over these time points.

The effect of exogenous ABA spraying on the resistance of greater yam

-

Fresh and healthy greater yam leaves from susceptible varieties were cleaned with alcohol, and then sprayed with double-distilled H2O and a solution of 7.58 μmol/L ABA. Following this treatment, the leaves were incubated at a temperature of 26 °C and a humidity of 95%–100% for 24 h. Subsequently, the leaves were inoculated in vitro, and the incidence of leaf disease was observed at 5 dpi.

Data analysis

-

Microsoft Excel 2016 was used for data processing, SPSS 26 software was used for data processing and statistical analysis, the least significant difference (LSD) method was used for significance testing, and GraphPad Prism software was used for graphing.

-

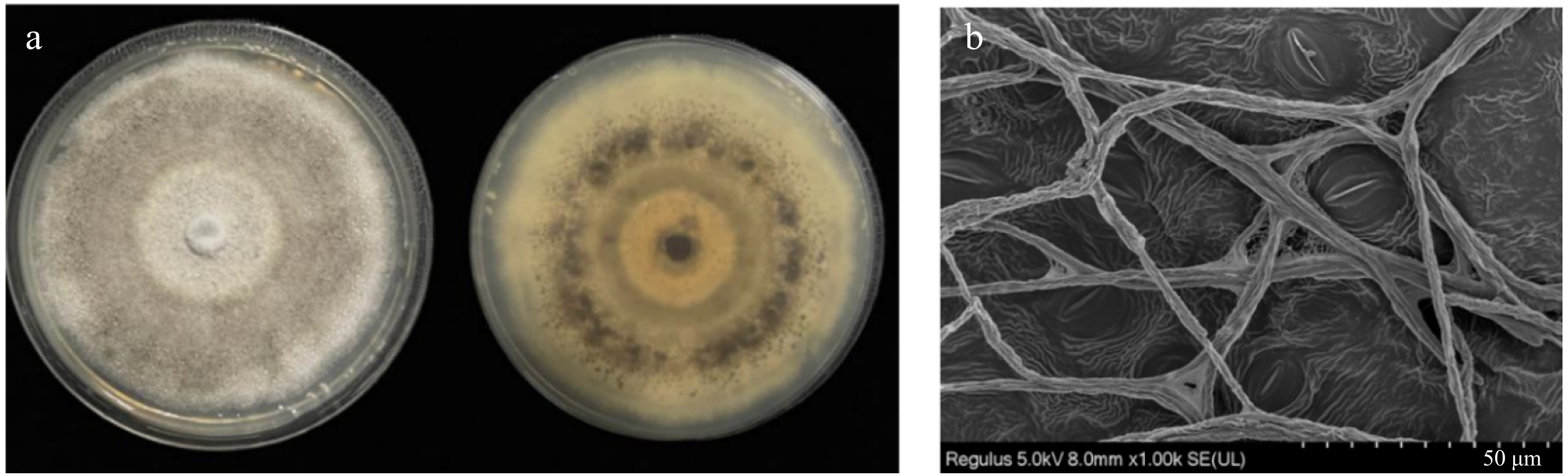

The pathogen was successfully isolated from diseased leaves collected in the field and cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium. Morphological characterization of the anthracnose mycelia was investigated. The cultured colonies were round with isodiametric and radial growth, featuring a smooth surface and well-defined edges. Initially, the hyphae were white, gradually turning dark gray. The aerial hyphae were robust, starting as white, then turning grey, and finally forming a dark gray flocculent structure (Fig. 1a). The mycelia were dense and slender (Fig. 1b), with morphological traits consistent with those of Colletotrichum spp. Additionally, the ITS region of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) from the isolated pathogen was sequenced to identify the strain. The ITS sequence showed over 99% homology with both C. gloeosporioides and C. alatae. To further confirm the type of strain, the rDNA-CAL region was amplified via PCR using the specific primer to obtain a DNA fragment of approximately 700 bp in length (Supplementary Fig. S1). The rDNA CAL sequence shared over 99% homology exclusively with C. alatae. Based on these molecular biology findings, the isolated and purified strain was identified as C. alatae.

Figure 1.

Morphology of isolated strains. (a) Morphology of aerial hyphae; (b) Morphology of mycelia.

Identification of anthracnose resistance in greater yam varieties

-

The resistance levels of greater yam varieties cultivated in the plantation of Jiangxi Agricultural University were evaluated through in vitro inoculation with anthracnose pathogen (Supplementary Fig. S1). Based on the disease index, the resistance levels of the varieties were categorized into five classes: immune, high resistance, resistant, susceptible, and highly susceptible (Table 3). The results revealed significant variation in anthracnose resistance among the varieties. Specifically, immune varieties constituted 16.3% of the total tested varieties, high resistance accounted for 4.65%, resistance for 23.3%, susceptibility for 45.3%, and highly susceptible varieties for 11.6%.

Table 3. Evaluation of anthracnose resistance in different varieties of Dioscorea alata L.

Varieties Disease index Relative disease

resistance indexResistance evaluation Varieties Disease index Relative disease

resistance indexResistance

evaluationD-28 0.00 1.00 I D-279 14.29 ± 1.19 0.80 S D-31 0.00 1.00 I D-13 14.29 ± 0.15 0.80 S D-18 0.00 1.00 I D-14 14.29 ± 0.35 0.80 S D-33 0.00 1.00 I D-15 14.29 ± 0.76 0.80 S D-8 0.00 1.00 I D-41 14.30 ± 0.22 0.80 S D-406 0.00 1.00 I D-401 17.14 ± 5.08 0.76 S D-303 0.00 1.00 I D-419 19.05 ± 1.92 0.73 S D-284 2.38 ± 0.44 0.97 HR D-7 21.43 ± 1.92 0.70 S D-288 2.38 ± 0.06 0.97 HR D-6 23.80 ± 2.86 0.67 S D-29 3.57 ± 0.45 0.95 R D-400 23.81 ± 2.76 0.67 S D-403 4.76 ± 0.75 0.93 R D-36 23.81 ± 1.40 0.67 S D-402 4.76 ± 0.72 0.93 R D-304 28.57 ± 3.17 0.60 S D-297 4.76 ± 1.35 0.93 R D-20 28.57 ± 7.53 0.60 S D-11 4.76 ± 0.18 0.93 R D-264 28.57 ± 6.49 0.60 S D-24 4.76 ± 0.26 0.93 R D-34 28.57 ± 4.74 0.60 S D-5 4.80 ± 1.30 0.93 R D-9 28.57 ± 7.53 0.60 S D-405 5.71 ± 0.52 0.92 R D-4 28.60 ± 2.57 0.60 S D-38 9.52 ± 1.10 0.87 R D-10 35.70 ± 2.04 0.50 HS D-294 9.52 ± 0.43 0.87 R D-274 45.70 ± 2.57 0.36 HS D-1 11.40 ± 0.73 0.84 S D-32 45.70 ± 4.20 0.36 HS D-407 14.29 ± 0.76 0.80 S D-3 57.14 ± 2.64 0.20 HS D-23 14.29 ± 0.15 0.80 S D-306 57.14 ± 2.64 0.20 HS D-2 14.29 ± 0.28 0.80 S D-404 71.43 ± 4.20 0.00 HS Analysis of leaf wax and stomata of resistant and susceptible varieties

-

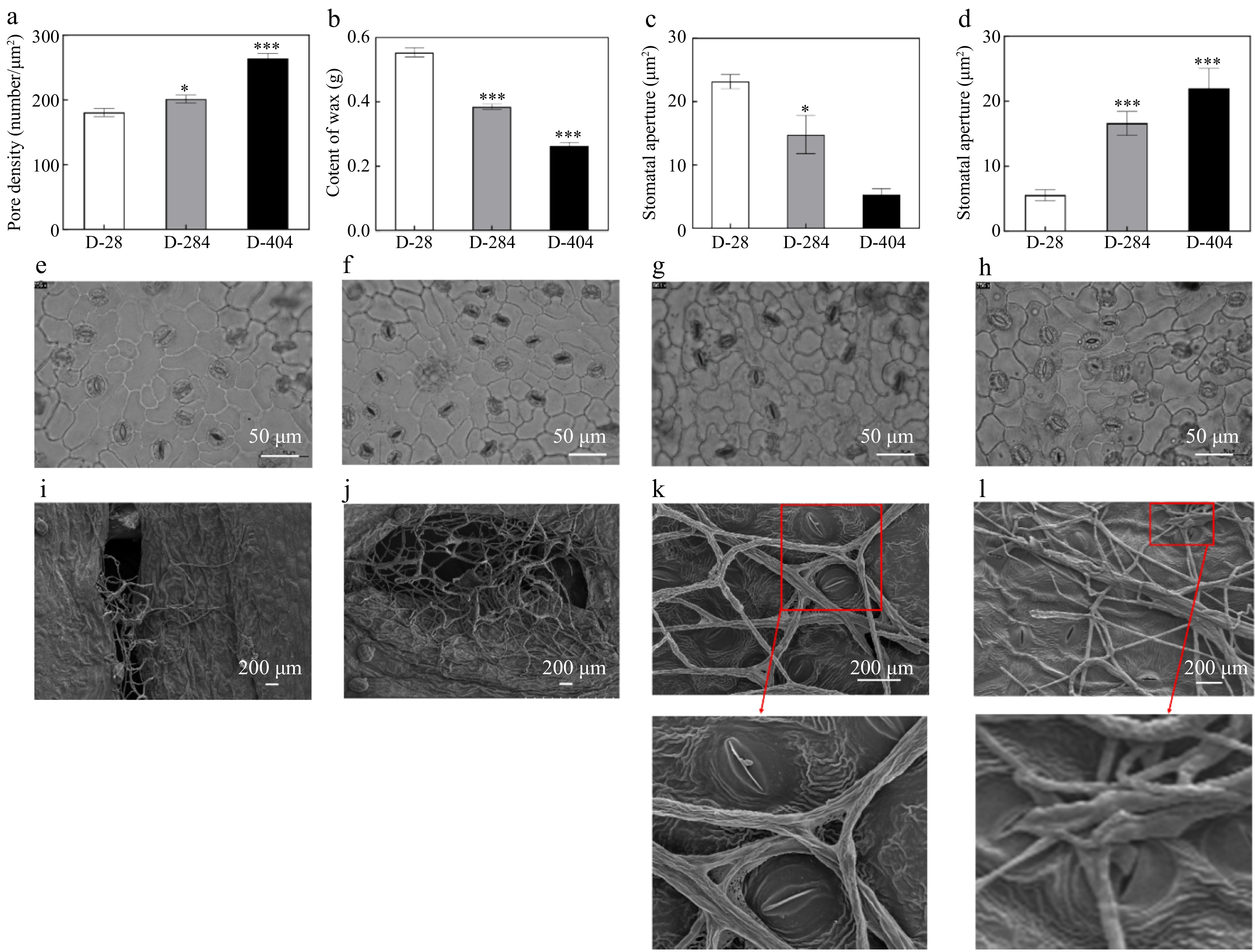

The susceptible variety D-404 and the resistant variety D-284 had relatively high stomatal densities, while the immune variety D-28 had the lowest. The stomatal densities of the susceptible D-404 and resistant D-284 were significantly higher compared to the immune D-28 (Fig. 2a). The immune variety D-28 had the highest wax content at 0.56 ± 0.02 g, followed by the resistant D-284 at 0.385 ± 0.04 g, with the susceptible D-404 having the lowest at 0.270 ± 0.04 g. The wax content in the susceptible variety was significantly lower than that in the immune variety (Fig. 2b). Before inoculation with the anthracnose pathogen, the immune variety D-28 had the largest stomatal opening, and the variety D-404 had the smallest (Fig. 2c). The stomatal microstructure revealed that the most stomata in the leaves of the disease resistant variety D-284 were open, whereas those in the susceptible variety D-404 were predominantly closed (Fig. 2e & f). After inoculation with the anthracnose pathogen, the immune variety D-28 had the smallest stomatal opening, followed by the resistant variety D-284, while the susceptible variety D-404 had the largest stomatal opening (Fig. 2d). The stomatal microstructure of the resistant and sensitive varieties also confirmed the above results. After inoculation, most stomata in the resistant variety D-284 were closed (Fig. 2g & k), whereas most of the leaf stomata of the susceptible variety D-404 were open (Fig. 2h & l). Scanning electron microscopy revealed that anthracnose mycelia grew and enriched more rapidly in the susceptible variety during the early stage of inoculation (Fig. 2i & j), and it was observed that anthracnose mycelia could invade through the stomata of the leaves (Fig. 2k & l).

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of wax contents and stomatal in leaves of different resistant varieties of Dioscorea alata L. (a) Comparison of stomatal density in leaves of different resistant varieties. (b) Comparison of wax content in leaves of different resistant varieties. (c) Comparison of stomatal opening in leaves of different resistant varieties before inoculation. (d) Comparison of stomatal opening of different resistant varieties after inoculation. (e) Microscopic image of stomata before inoculation of resistant variety. (f) Microscopic image of stomata before inoculation of susceptible variety. (g) Microscopic image of stomata after inoculation of resistant variety. (h) Microscopic image of stomata after inoculation of susceptible variety. (i) The mycelia in the inoculation holes of the resistant variety leaves at 1 dpi. (j) The mycelia in the inoculation holes of the susceptible variety leaves at 1 dpi. (k) Stomatal development of resistant variety leaves at 3 dpi. (l) Stomatal development of susceptible variety leaves at 3 dpi. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. TBP groups vs 1 dpi, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

Effects of abscisic acid (ABA) on resistance to anthracnose in greater yam

-

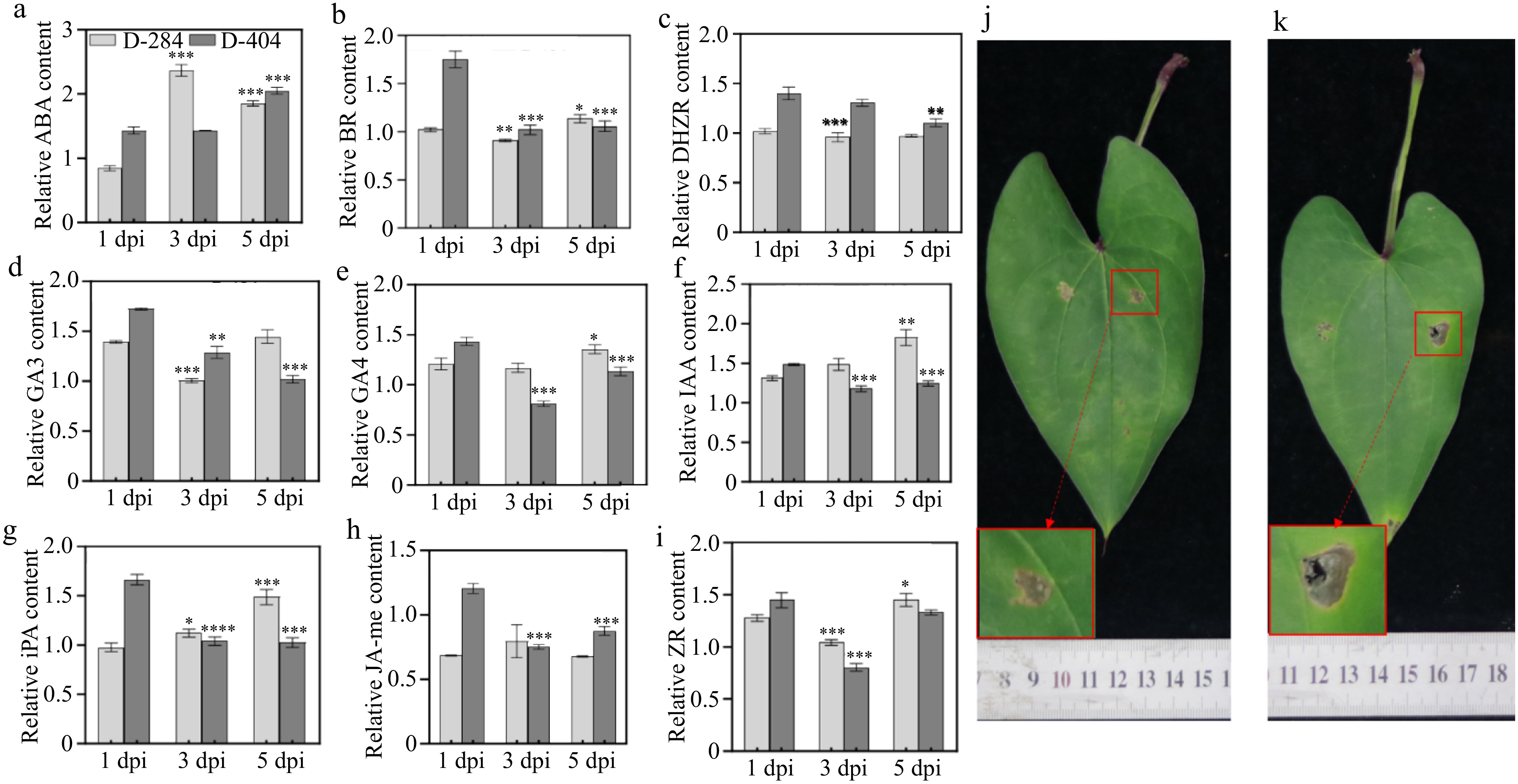

The ABA content in the leaves of the resistant variety D-284 initially increased but then declined over time, reaching a maximum at 3 dpi. In contrast, the ABA content in the susceptible variety D-404 leaves remained relatively stable initially and only increased significantly at 5 dpi (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Comparison of hormones content after anthracnose invasion and disease resistance after exogenous spraying of ABA. (a)−(i) Comparison of hormones content after anthracnose invasion. (j) Phenotype of anthracnose pathogen inoculation after exogenous spraying of ABA in susceptible variety (left of leaf vein: control; right side of leaf vein: inoculation of anthracnose pathogen). (k) Phenotype of anthracnose pathogen inoculation in susceptible variety (left of leaf vein: control; right side of leaf vein: inoculation of anthracnose pathogen). The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. TBP groups vs 1 dpi, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

The content of BR, GA3, and ZR in the leaves of resistant and susceptible varieties exhibited a decreasing trend at 3 dpi (Fig. 3b−d & i). Additionally, the levels of IAA and iPA increased in the leaves of resistant variety, while they decreased in the susceptible variety (Fig. 3f & g). Meanwhile, the concentrations of GA4, DHZR, and JA-me decreased in the susceptible variety, but remained relatively unchanged in the resistant variety (Fig. 3e & h). Hormone content analysis revealed that ABA is rapidly mobilized in the resistant variety infected by pathogens, implying a potential link between ABA and anthracnose resistance in greater yam. To further investigate this, an exogenous ABA spray test was conducted. Compared to the control group without ABA spray, the treatment group with ABA spray exhibited a reduced spread of lesions on the leaves of the susceptible variety D-404, with smaller lesions, and less visible hyphal growth (Fig. 3j & k). This indicates that exogenous ABA application can enhance resistance to anthracnose in greater yam.

Comparative analysis of defense enzymes in resistant and susceptible greater yam varieties after inoculation by anthracnose

-

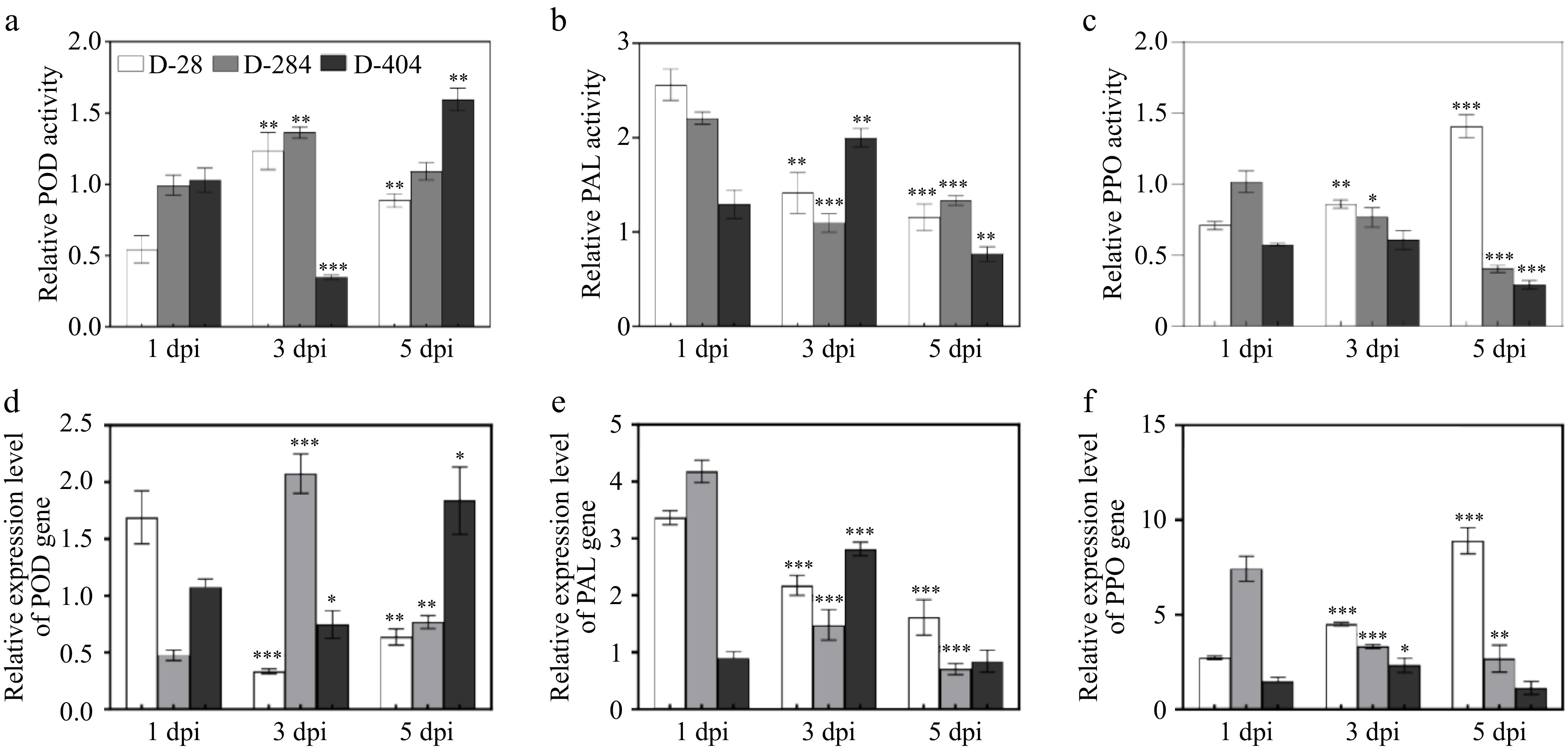

POD activity increased at 3 dpi in both the immune variety D-28 and resistant variety D-284, while in the susceptible variety D-404, it was downregulated at 3 dpi and upregulated at 5 dpi (Fig. 4a). The POD-encoding gene was upregulated at 1 dpi in the immune variety D-28, 3 dpi in the resistant variety D-284, 3 dpi in the resistant variety D-284, and at 5 dpi in the susceptible variety D-404 (Fig. 4d). PAL activity increased at 1 dpi in the immune variety D-28 and the resistant variety D-284, and at 3 dpi in the susceptible variety D-404. The expression of PAL-encoding gene was upregulated at 3 dpi (Fig. 4b), with the increasing trend of PAL gene expression aligning with enzyme activity (Fig. 4e); PPO activity showed little change at 1 and 3 dpi in all varieties. However, the resistant variety D-284 and the susceptible variety D-404 exhibited downregulation at 5 dpi, whereas the immune variety D-28 showed upregulation (Fig. 4c). There was a consistent upregulation trend of PPO-encoding gene in the variety D-28 and the resistant variety D- 284 following inoculation (Fig. 4f).

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of defense enzymes post anthracnose infection of different resistant varieties of Dioscorea alata L. (a) Relative POD activity of immune variety D-28, resistant variety D-284, and susceptible variety D-404. (b) Relative PAL activity of immune variety D-28, resistant variety D-284, and susceptible variety D-404. (c) Relative PPO activity of immune variety D-28, resistant variety D-284, and susceptible variety D-404. (d) Relative expression level of POD gene of immune variety D-28, resistant variety D-284, and susceptible variety D-404. (e) Relative expression level of PAL gene of immune variety D-28, resistant variety D-284, and susceptible variety D-404. (f) Relative expression level of PPO gene of immune variety D-28, resistant variety D-284, and susceptible variety D-404. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. TBP groups vs 1 dpi, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

-

The yam anthracnose was caused by Colletotrichum spp. The colony characteristics and spore morphology of the anthracnose pathogen isolated in this study align with the reported morphological features of Colletotrichum spp. However, different species in Colletotrichum spp. have similar hyphal structures. So it is difficult to distinguish the species only by morphological characteristics. The ITS sequence is commonly used to identify species of anthracnose pathogens and has been successfully applied to the identification of pathogens from various parasitic plants. For instance, the citrus anthracnose fungus has been identified as C. gloeosporioides by ITS sequence[28]. The anthracnose pathogen isolated from strawberry samples in Zhejiang and Shanghai regions were identified as C. gloeosporioodes, C. fragariae, and C. acutatum also by ITS sequence[29]. The anthracnose pathogens of red pepper were identified as C. gloeosporioides, C. acutatum, C. truncatum, and C. Brevisporum by ITS4 and ITS5 sequence[30]. Although ITS sequence analysis has improved the accuracy of anthracnose pathogen species identification, its limitations are becoming apparent, particularly when differentiating closely related species due to the lack of significant differences in the hypervariable regions of the ITS region. Consequently, researchers have begun to explore other gene sequences with higher interspecies resolution[31]. Actin, CAL, Chitin Synthase 1, Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase, Glutamine Synthetase, ITS, β-Tubulin sequences were used to identify two new anthracnose pathogens from Protea and four previously reported species[32–33]. In this study, traditional morphological identification was complemented by ITS and CAL sequence analysis to identify the pathogenic bacteria. The results showed that the ITS sequence had over 95% homology with sequences associated with C. gloeosporioides and C. alatae. However, the CAL sequence exhibited higher homology with C. alatae. Based on these findings, we conclude that the anthracnose pathogen in greater yam should be identified as C. alatae. It has been reported that anthracnose in yam is mostly caused by C. gloeosporioides[34−41]. C. alatae has only been reported in D. polystachya Turcz, and this study marks the first report of anthracnose caused by this pathogen in greater yam[42].

The breeding of resistant varieties is an economical, safe, and effective approach to controlling plant diseases. Resistant variety resources are essential for developing disease-resistant crop varieties. Consequently, the establishment of an accurate and reliable resistance evaluation system is vital for screening these resources, which in turn greatly enhances the efficiency of breeding for disease resistance[43]. This study used anthracnose pathogenic bacteria isolated in the field to inoculate 46 greater yam varieties from the plantation of Jiangxi Agricultural University in vitro. We assessed their resistance to anthracnose and successfully identified immune, disease-resistant, and susceptible varieties, providing valuable genetic resources for the study of anthracnose resistance in greater yams.

Wax serves as a natural barrier against pathogen infections, and its thickness directly influences the ability of pathogens to invade plant tissues[10,11]. In this study, the waxy content of the leaves in the immune variety D-28 was notably higher than that in the resistant variety D-284 and the susceptible variety D-404. Notably, the susceptible variety D-404 exhibited the lowest waxy content. This finding suggests a strong correlation between leaf wax content and the immunity of greater yam to anthracnose. Furthermore, the stomatal density in the leaves of immune and resistant varieties was generally lower compared to that of susceptible varieties. This further indicates that a lower stomatal density in leaves is associated with increased resistance to anthracnose in greater yam.

Plant hormones play important roles in the plant immune response to pathogens[44−47]. When plants are attacked by pathogens, the phytohormone signaling network is rapidly activated to increase plant disease resistance. These hormonal signals and immune responses enable plants to sustain normal growth and maintain basal defenses against pathogens, conserving energy and resources while enhancing their environmental adaptability[48]. The results of this study revealed that at 3 dpi with the anthracnose pathogen, the ABA content in the leaves of the resistant variety was significantly higher than that in the susceptible variety. This suggests that ABA may play a role in the resistance of greater yam to anthracnose. Furthermore, after exogenous application of ABA, the disease resistance in the leaves of the susceptible greater yam variety was enhanced, with a reduced spread rate of diseased spots compared to the control group. These results further confirm that ABA can improve the resistance of greater yam leaves to anthracnose.

When pathogens infect plants, they usually enter through the stomata and colonize the intercellular spaces. Therefore, regulating the opening and closing of stomata is an important defense mechanism for plants to defend against pathogen infection, multiple pathogens can invade plants through open stomata[49−51]. During pathogen infection, plants can rapidly close their stomata to prevent further pathogen entry. However, the invasion method of C. alatae has not been reported previously. In this study, we observed that the mycelia of C. alatae invade leaves through stomata. It has been reported that the endogenous plant hormone ABA plays a significant role in stomatal movement. When ABA levels are reduced, plants are unable to quickly respond by closing their stomata, which hampers their ability to effectively combat pathogen infection[52]. In this study, we observed that the stomata of the immune variety D-28 and resistant variety D-284 were open when they were not inoculated with the anthracnose pathogen. However, the growth of hyphae from the inoculation sites in the resistant greater yam variety was slow after infection by the anthracnose pathogen, ABA levels in the leaves increased, and the stomata closed. In contrast, the susceptible variety showed faster growth and accumulation of hyphae at the inoculation sites, with most stomata remaining open, allowing hyphae to enter through them. These findings suggest that disease-resistant greater yam varieties combat anthracnose infection by elevating leaf ABA content, which in turn closes the stomata and blocks the invasion of anthracnose pathogenic hyphae.

POD is an oxidoreductase enzyme that is widely present in plants and plays a critical role in plant defense mechanisms. It produces hydrolytic enzymes that defend against pathogens, preventing their establishment within the plant and thereby enhancing disease resistance[15,53]. In this study, after inoculation with the anthracnose pathogen, disease-resistant and immune varieties rapidly increased the expression and activity of the POD gene to effectively combat further pathogen invasion. In contrast, the susceptible variety exhibited a slower response, with a delayed increase in POD activity. PAL is a key enzyme in the synthesis of phenols and acts as the rate-limiting enzyme in the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway. PAL strengthens cell wall structure through lignin synthesis and promotes the production of phenolic compounds by phytoalexins. These compounds can inhibit pathogen growth or trigger plant resistance[54−58]. In this study, after pathogen inoculation, the disease-resistant variety rapidly activated the expression of the PAL-encoding gene and enhanced PAL enzyme activity, thereby bolstering their resistance to pathogens.

-

This study isolated the anthracnose pathogen from the greater yam in the plantation of Jiangxi Agricultural University and identified it as C. alatae, a species not previously reported in greater yams, through morphological, and molecular methods. Resistance evaluation and identification were conducted on 46 greater yam varieties by inoculating with C. alatae. The immune variety D-28, resistant variety D-284, and susceptible variety D-404 were selected for further studies on resistance mechanisms. Compared to the susceptible variety, immune and resistant varieties exhibited lower stomatal densities and higher wax contents. After anthracnose pathogen infection, immune and resistant varieties rapidly accumulated and increased the activities of POD and PAL, as well as the expression levels of their encoding genes. The stomata of the leaves in immune and resistant varieties transitioned from open to closed, while those in the susceptible varieties shifted from closed to open post anthracnose pathogen infection. Moreover, our finding demonstrated for the first time that anthracnose hyphae can invade through leaf stomata and that hyphae in the susceptible variety grow and accumulate more rapidly. The ABA content in the leaves of the resistant variety was significantly higher than that in the susceptible variety at the early stage of inoculation, and exogenous ABA application enhanced the disease resistance of susceptible variety. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that the resistance in resistant greater yam is improved by increasing endogenous ABA content in the leaves, inducing the stomatal closure in the leaves, and preventing the invasion of anthracnose pathogenic hyphae. This study provides foundational materials and theoretical support for the breeding of anthracnose-resistant greater yam and offers insights into the biological control of anthracnose. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of ABA content and stomatal closure by disease-resistant greater yam varieties need to be deeply investigated.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32460767), and the Jiangxi Provincial Key Research and Development Project of China (Grant Nos 20232BBF60007 and 20212BBF61004).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Ren J, Pu J,Zhou Q, Luo S; methodology: Ren J, Pu J, Yu J; software: Sun J; validation: Wang S; formal analysis: Chen A, Shan N; investigation: Ren J, Pu J; resources: Zhou Q, Huang Y; data curation: Ren J; writing—original draft preparation: Ren J, Pu J; writing—review and editing: Zhou Q, Luo S; supervision: Zhou Q, Luo S; project administration: Zhou Q, Luo S; funding acquisition: Zhou Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

accompanies this paper at (https://www.maxapress.com/article/doi/10.48130/tp-0025-0013)

-

Received 22 January 2025; Accepted 21 March 2025; Published online 30 June 2025

-

A new anthracnose pathogen Colletotrichum alatae was isolated.

Lower stomatal density and greater wax content were associated with resistance.

Mycelia invade through their stomata.

Resistant greater yam improve resistance by increasing the endogenous ABA content and reducing the stomatal closure of leaves.

Immune and resistant germplasm were able to rapidly accumulate and increase the activity and expression of their POD and PAL encoding genes.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jing Ren, Junhong Pu

- Supplementary Table S1 Experimental materials and sources.

- Supplementary Table S2 Primers for PCR amplification and RT-qPCR gene expression analysis.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Phenotype of greater yam leaves after inoculation with anthracnose disease.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ren J, Pu J, Yu J, Huang Y, Shan N, et al. 2025. Evaluation of anthracnose-resistant greater yam and the mechanism of abscisic acid-mediated disease resistance. Tropical Plants 4: e021 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0013

Evaluation of anthracnose-resistant greater yam and the mechanism of abscisic acid-mediated disease resistance

- Received: 22 January 2025

- Revised: 11 March 2025

- Accepted: 21 March 2025

- Published online: 30 June 2025

Abstract: The greater yam (Dioscorea alata L.) is a major food crop in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in Africa. However, anthracnose disease, caused by Colletotrichum spp., significantly threatens greater yam production. Identifying anthracnose-resistant greater yam varieties is therefore of great importance. In this study, we evaluated the anthracnose resistance of 46 greater yam varieties using in vitro leaf inoculation with C. alatae isolated and identified at Jiangxi Agricultural University (Nanchang, China). We examined the physiological and biochemical indices, including stomatal density and opening, activities of peroxidase (POD), polyphenol oxidase (PPO), and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), as well as abscisic acid (ABA) levels, in leaves of varieties with different resistance levels. Compared with susceptible varieties, immune and resistant varieties exhibited lower stomatal density and higher leaf wax content. Following infection, immune and resistant varieties rapidly increased POD and PAL activities, along with the expression of their encoding genes. Stomata in immune and resistant varieties closed, whereas those in susceptible varieties opened, facilitating pathogen invasion and resulting in rapid growth and accumulation of anthracnose mycelia in susceptible varieties. Resistant varieties maintained higher leaf ABA levels than the susceptible varieties during the early stages of inoculation. Additionally, the exogenous application of ABA enhanced the resistance of susceptible varieties. Our findings suggest that resistant greater yam varieties may improve resistance by increasing endogenous ABA levels and inducing stomatal closure, thereby hindering the invasion of anthracnose pathogenic mycelia. These results provide important insights for breeding anthracnose-resistant greater yam varieties and developing sustainable disease management strategies.

-

Key words:

- Defense-related enzyme activity /

- Abscisic acid /

- Greater yam /

- Anthracnose resistant