-

Ethylene, a gaseous plant hormone comprising two carbon atoms and four hydrogen atoms, plays a pivotal role in plant growth and developmental stages, including seed germination, root elongation, flowering, fruit ripening, and the adaptation to both biotic and abiotic stresses[1]. Ethylene serves as a signal molecule that diffuses rapidly and is perceived by plants, thereby exerting positive or negative effects on them, depending on the plant species, the stage of tissue development, and ethylene concentration. In low concentrations, ethylene promotes plant growth and development. However, excessive exposure to high concentrations of ethylene noticeably inhibits plant growth and development[2,3]. Extensive research on fleshy fruits has revealed that the role of ethylene varies across different stages of development. When exposed to ethylene, immature fruits exhibit auto-inhibition of ethylene synthesis and inability to ripen, a process referred to as system 1 ethylene synthesis. Conversely, applying ethylene to mature fruits triggers auto-catalytic ethylene synthesis and accelerating ripening, a mechanism known as system 2 ethylene synthesis[4,5]. At present, the mechanism by which plants sense the exposure level of ethylene is still unknown. Therefore, the precise regulation of ethylene biosynthesis is of utmost importance. It encompasses the transcriptional and post-translational regulation of the enzymes involved in ethylene synthesis, as well as the transport and conjugation of the essential precursor, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC).

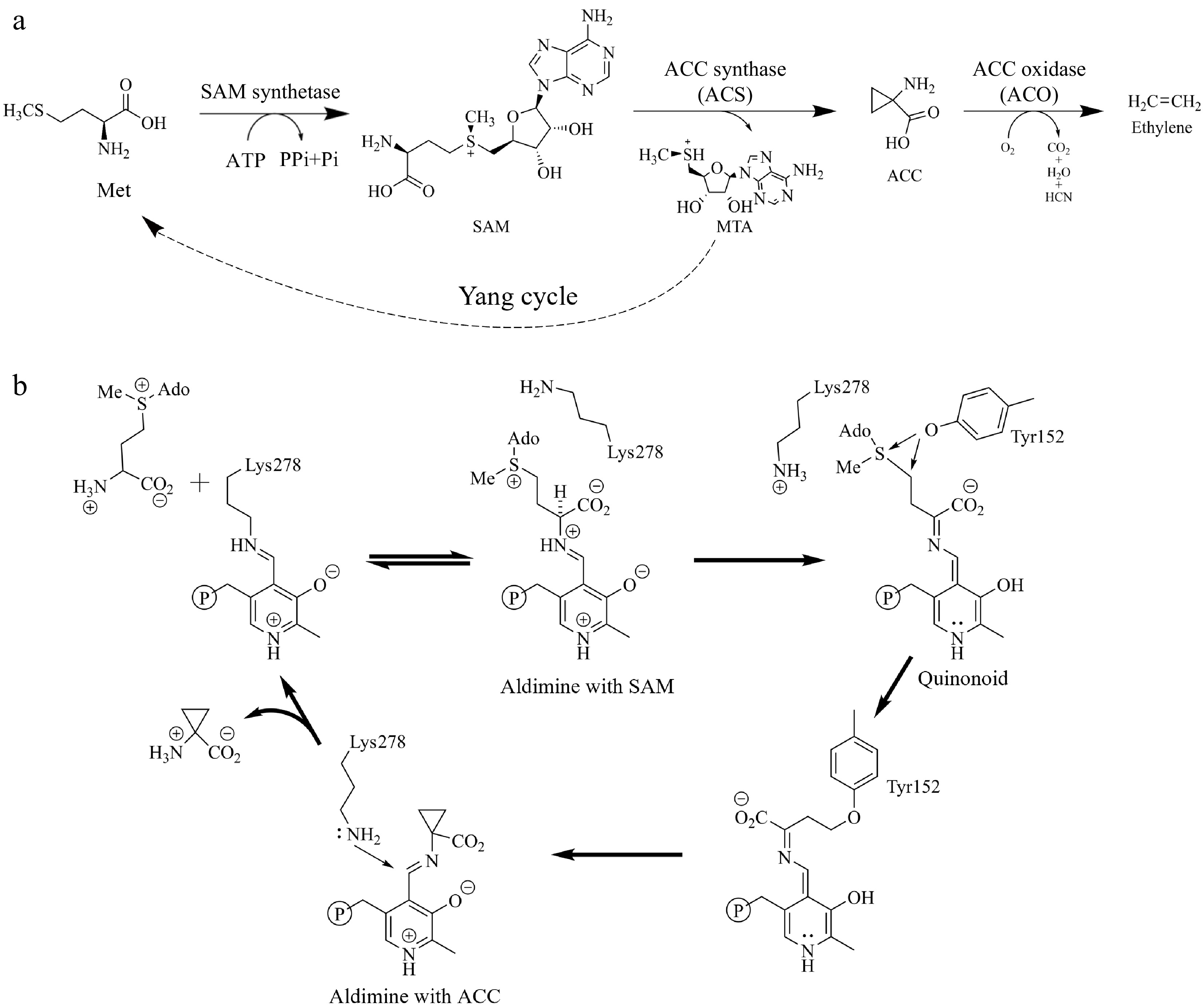

The biosynthetic pathway of ethylene is simple (Fig. 1a). Firstly, methionine (Met) is converted to S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) by SAM synthase. SAM then undergoes catalysis by ACC synthase (ACS) to produce ACC and 5'-methylthioribose (MTA)[6,7]. ACC is a direct precursor and key intermediate in ethylene biosynthesis. ACC is then converted into ethylene, CO2, and cyanide through ACC oxidase (ACO)[8,9]. Among these, the formation of ACC is the rate-limiting step of ethylene biosynthesis. Consequently, the manipulation of the transcription, translation, and protein stability of ACC synthase offers a means to regulate ethylene production in plants. This approach allows for enhanced control over plant development and improved resilience to stress conditions in agricultural production. This review comprehensively summarizes the regulatory mechanisms of the rate-limiting enzyme ACS in plant ethylene biosynthesis and its significant contributions to plant growth, development, and stress response.

Figure 1.

Ethylene biosynthesis pathway. (a) Ethylene biosynthesis starts with methionine (Met) as the primary substrate, followed by the sequential actions of SAM synthetase, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) synthase (ACS), and ACC oxidase (ACO). (b) A putative mechanism for the conversion of SAM to ACC.

-

ACS belongs to the pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent aminotransferase family and requires PLP as a co-factor for its activity[10,11]. The stability of ACC synthase is susceptible to various factors, such as stress and plant hormones. In early studies, ACS was successfully isolated from wounded climacteric mature fruits[12,13]. Although ACS is encoded by a multigene family, its polypeptides are similar in molecular size, varying between 50 and 62 kDa[14]. The members of the ACS gene family in various plants have been identified. For instance, 12 ACS genes were found in Arabidopsis[14], 14 in tomato[15], 13 in pumpkin[16], and 12 in wheat[17]. These ACS genes are expressed in diverse tissues and developmental stages of plants, and their expression is modulated by various signals, including environmental cues and hormonal factors. SlACS1A, SlACS2, SlACS4, and SlACS6 are all expressed during the ripening process of tomato fruits, but they exhibit distinct expression patterns and varying responses to ethylene. Specifically, during fruit ripening, the expression levels of SlACS2 and SlACS4 increase significantly and are responsible for system 2 ethylene synthesis, exhibiting a positive correlation with ethylene production. Conversely, SlACS1a and SlACS6 are thought to participate in system 1 ethylene synthesis, and their expression is under negative regulation by ethylene[18]. In Arabidopsis, the expression of AtACS2, AtACS6, AtACS7, and AtACS9 is distinctly upregulated in hypoxic conditions[19]. AtACS8 is regulated by light exposure and the circadian rhythm[20]. Additionally, AtACS2 and AtACS5 respond to abscisic acid regulation during seedling growth and development[21].

Early studies suggested that ACS functions predominantly in the cytosol. However, recent research has shown that in citrus, CiACS4 interacts with the ethylene-responsive transcription factor CiERF3 in the nucleus and subsequently suppresses the expression of GA20-oxidase genes[22]. The findings indicate that ACS proteins may co-localize in multiple subcellular compartments, which requires further research to determine whether this co-localization is species conserved or depends on tissue specificity or specific physiological conditions.

The structure and catalytic mechanism of ACS

-

Sequence analysis shows that ACS is evolutionarily related to aminotransferase (AATase), and they share common essential active sites, including seven highly conserved boxes and 11 conserved residues[14,23]. By analyzing the crystal structure of apple ACS, key amino acid residues at the active site were identified, including Tyr85, Thr121, Asn202, Asp230, Tyr233, Ser270, Lys273, Arg281, and Arg407[24]. These residues occupy vital positions at the PLP binding site and the homodimer interface and are conserved with chicken mitochondrial AATase[24]. Crystal structure analysis of tomato ACS shows that its monomer comprises two domains, similar to the structure of apple ACS[24]. Further research has elucidated a putative mechanism for the conversion of SAM to ACC (Fig. 1b)[25]. First, the PLP cofactor forms an internal aldimine with the amino acid residue Lys278 of ACS, and then the substrate SAM forms an external aldimine intermediate with the PLP-lysine internal aldimine. Next, Tyr152 catalyzes the breakage of the C-γ–S bond in SAM, resulting in the formation of a covalent intermediate that subsequently undergoes a transition into ACC·aldimine. Ultimately, the unprotonated Lys278 attacks the C4′ position of PLP, leading to the release of ACC[25]. This mechanism is similar to the PLP-dependent catalytic enzymes.

Interestingly, in addition to catalyzing SAM into ACC, genuine ACS proteins in seed plants generally have Cβ-S lyase activity, specifically converting l-cystine into pyruvate[26]. This implies that ACS proteins may have originated from Cβ-S lyases. Pyruvic acid is one of the catalytic products, which is the final product of glycolysis and also the energy substrate of the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle. This indicates that ACS not only plays an important role in ethylene synthesis but may also participate in respiratory and energy metabolic processes. Therefore, the significance of ACS in plant life needs to be further explored. By analyzing the critical sites of the dual enzyme activity of AtACS7, Xu et al. proposed a standard structural model for genuine ACS proteins, encompassing nine conserved ACS domains designated as ACS-motif 1-9. Notably, the second ACS-motif at the N-terminal must harbor a conserved glutamine residue[26]. This study marks a breakthrough in our comprehension of the functions of the ACS gene family and the regulation of ethylene synthesis.

-

As a crucial rate-limiting enzyme in ethylene synthesis, the regulation of ACS activity is the core link in ethylene biosynthesis. ACS is primarily regulated at the transcription level, and, involves post-translational regulation, such as protein turnover mediated by phosphorylation and proteasome-dependent degradation. Additionally, ACS activity is also subject to exogenous regulation by chemical means.

Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of ACS

-

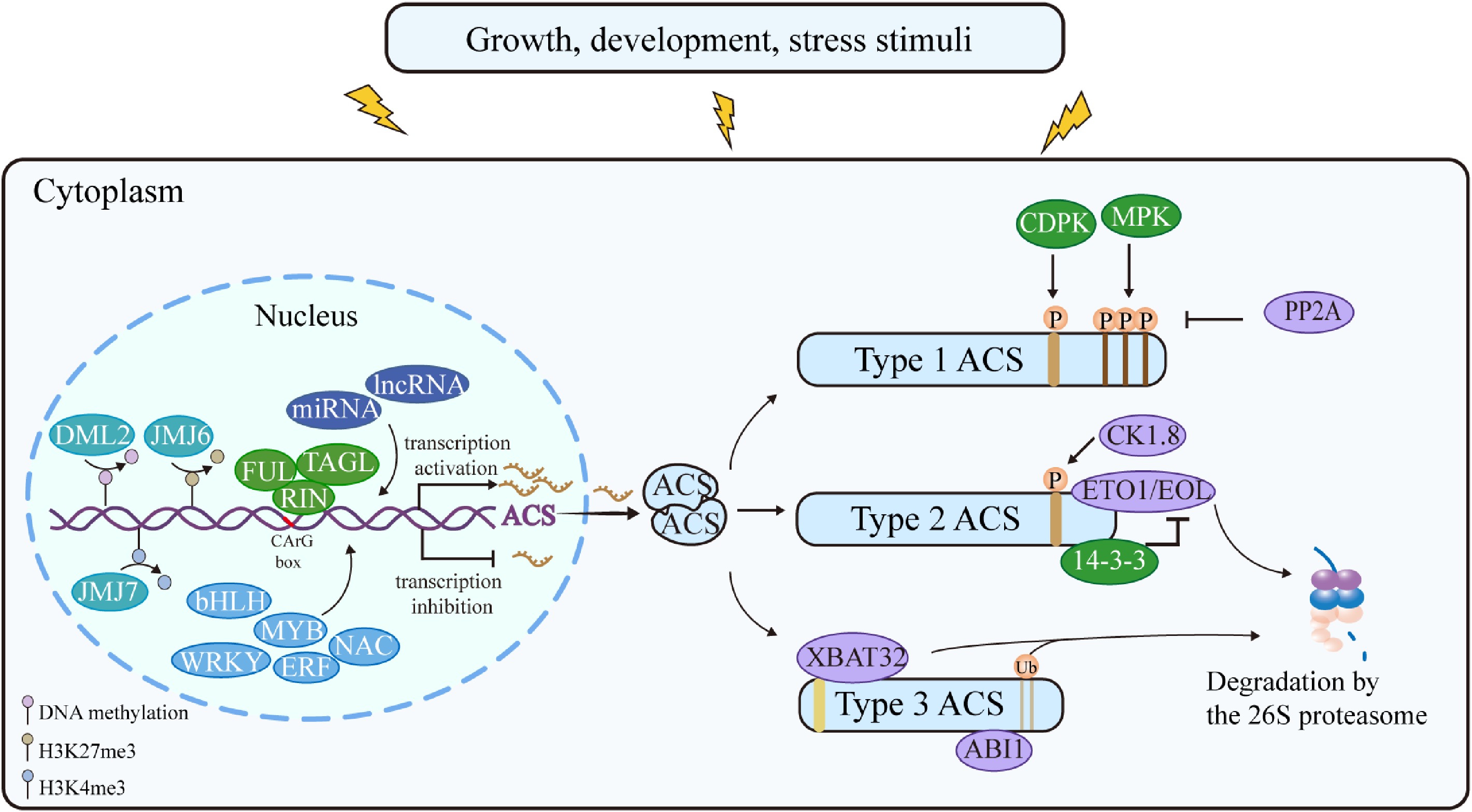

Changes in ACS mRNA levels can significantly impact ethylene biosynthesis, thus the transcriptional regulation of ACS is a crucial aspect in controlling ethylene production. Currently, multiple transcription factor families have been identified that positively or negatively regulate ACS transcription and participate in various developmental processes of plants (Fig. 2). The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors FLOWERING BHLHs (FBHs) are involved in the regulation of the circadian clock and internode maturation in sugarcane by binding to the promoter of ScACS2 and activating its expression[27]. WRKY transcription factors 29 directly interact with the promoters of AtACS5, AtACS6, AtACS8, and AtACS11 to enhance their expression, subsequently modulating the production of basal ethylene and impacting primary root elongation as well as lateral root growth in Arabidopsis[28]. Notably, the MADS-box transcription factor RIPENING INHIBITOR (RIN) is the first to be identified as regulating tomato SlACS2 expression by binding to the CArG site of the promoter[29]. Moreover, it can interact with FRUITFULL1 (FUL1), FUL2, and TOMATO AGAMOUS-LIKE1 (TAGL1) individually, forming complexes that exhibit transcriptional activation functions[30]. Subsequently, a positive feedback loop regulating ACS gene expression in tomato fruits is proposed, involving ethylene transcription factors ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3(EIN3), RIN, and TAGL1. Similarly, in peach and banana fruits, a positive feedback loop involving transcription factors NAC or a MADS/NAC combination is proposed[31]. In addition, when plants perceive stress signals, ACS rapidly responds under the regulation of multiple transcription factors to address the stress process. For instance, in Arabidopsis, AtWRKY33 binds to the W-box present in the promoters of AtACS2 and AtACS6, activating their expression downstream of the mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 and 6 (MPK3/MPK6) cascade, thereby conferring resistance against pathogen attacks[32]. Conversely, the expression of AtACS7 is directly inhibited by AtMYB30, thereby improving the flood tolerance of Arabidopsis plants[33]. PtrERF9 affects ethylene biosynthesis by activating the expression of PtrACS1, contributing to the cold tolerance of trifoliate orange[33].

Figure 2.

Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of ACS. RIN interacts with FUL and TAGL1 separately to bind to the CArG box in the ACS promoter, activating the transcription of ACS. Other transcription factor families, including bHLH, ERF, MYB, NAC, and WRKY, can also regulate transcription by binding to the ACS promoter. The promoter of ACS is also subjected to epigenetic regulation through methylation and histone modification, thereby affecting transcriptional accessibility. ACS has different specific motifs and is subject to different post translation regulation. Type I ACS is phosphorylated by CDPK and MPK, leading to an increased protein stability, while PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation negatively regulates protein stability. CK1.8 enhances the binding of ETO1/EOL by phosphorylating Type II ACS, thereby promoting protein degradation. 14-3-3 proteins protect Type II ACS from degradation by interacting with ACS and promoting the turnover of ETO1/EOL. XBAT32 and ABI1 interact with type III ACS and promote their degradation, respectively.

Furthermore, extensive research in fruit development and ripening has highlighted the pivotal role of epigenetic modifications in regulating the accessibility of ACS transcription, which encompasses both DNA methylation and histone modifications. Studies have shown that DNA demethylase 2 (SlDML2) serves as a key demethylation factor during fruit ripening, participating in the demethylation of the SlACS4 promoter to enhance its expression[34]. Since NAC-NOR directly regulates the expression of SlDML2, it is postulated that the elevated methylation level of the SlACS2 promoter in slnor mutants is associated with the suppression of SlDML2 expression[35]. Additionally, Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation (H3K4me) is a histone modification associated with transcriptional activation[36]. The removal of H3K4me3 mediated by SlJMJ7 directly inhibits the expression of SlACS2, SlACS4, and SlACS8. Furthermore, by demethylating H3K4me3, SlJMJ7 exerts a precise inhibitory effect on SlDML2 expression, ultimately leading to the downregulation of numerous ripening-related genes, including SlACS2 and SlACS4[37]. The trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3, known as H3K27me3, is an epigenetic mechanism for gene silencing[38]. The polycomb repressive complex (PRC) plays a crucial role in ensuring the precise target specificity and effective chromatin binding of H3K27me3[39]. In tomatoes, a PRC component named SlLHP1b inhibits the expression of SlACS2 and SlACS4 by maintaining the H3K27me3 state on their chromatin[40]. Conversely, SlJMJ6, an H3K27me3 demethylase, promotes the expression of SlACS4 by removing H3K27me3, thus facilitating tomato fruit ripening[41].

Plant hormones play a crucial role in regulating ethylene biosynthesis, including auxin, jasmonic acid, brassinosteroids, abscisic acid, and gibberellins. Auxin activates the auxin response factor MdARF5, which binds to the promoters of MdERF2, MdACS3a, and MdACS1, thereby initiating their expression and affecting ethylene biosynthesis[42]. Jasmonic acid promotes ethylene synthesis by enhancing the expression of MdMYC2, which can directly regulate the transcriptional accumulation of MdACS1 transcripts[43]. Remarkably, the application of brassinolide to tomato fruits significantly increases the accumulation of SlACS2 and SlACS4 transcripts, subsequently accelerating fruit ripening[44]. Although it has been well proved that various plant hormones can affect ethylene biosynthesis, it is necessary to further explore the transcription factors involved in hormone response pathways that directly regulate ACS gene expression. This can help us better understand the crosstalk among hormones and provide new strategies for regulating plant development and stress responses.

Recently, several reports have revealed the participation of non-coding RNAs in the post-transcriptional regulation of ACS. The overexpression of Sly-miR1917 results in a significant upregulation of the transcription levels of AtACS2 and AtACS4, thereby promoting elongation of the hypocotyl, accelerating pedicel abscission[45]. Considering that miRNAs participate in regulating various processes, such as plant growth, development, and stress responses, and they display evolutionary conservation among different species, predicting the targeting interactions between miRNAs and TaACS in wheat can provide further insights into the potential functions of TaACS[17,46]. Notably, TaACS10 is concurrently targeted by tae-miR44b, tae-miR404a, and tae-miR9655-3p, suggesting its potential involvement in wheat root development[17]. Additionally, TaACS8, TaACS11, and TaACS12 are recognized by tae-miR2275-3p, implying that they may play crucial roles during early meiosis in wheat[17]. In addition, some lncRNAs have been reported to be involved in the regulation of ACS, among which lncRNA1840 and lncRNA2155 indirectly regulate SlACS2 and SlACS4 during tomato fruit ripening.

Posttranslational regulation of ACS

-

Early studies found that the stability of ACS protein may undergo differential regulation in response to wounding[47]. Besides, the upregulation of ACS activity is insensitive to RNA transcription inhibitors[48,49], implying the existence of post-transcriptional mechanisms that mediate the regulation of ACS activity. Li & Mattoo demonstrated a significant variation in enzymatic activity when the C-terminus of the SlACS2 protein was truncated at varying lengths, suggesting that the non-conservative C-terminal region plays an important role in enzyme function[50].

Based on the specific motifs at the C-terminal of ACS proteins, ACS isozymes are classified into three types (Fig. 2). Type I is characterized by the presence of phosphorylation sites for calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). These phosphorylations impact protein abundance, thereby regulating the production of ethylene[51,52]. Protein sequence analysis has revealed that Arabidopsis AtACS1, AtACS2, and AtACS6, tomato SlACS1a, SlACS1b, SlACS2, SlACS6, and rice OsACS2 are classified as Type I ACS[53]. AtMPK3 and AtMPK6 can phosphorylate AtACS2 and AtACS6, effectively inhibiting the degradation of proteins, thus increasing the cellular production of ethylene[51,54,55]. On the contrary, protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) mediates the dephosphorylation of its C-terminal phosphorylated peptide by interacting with AtACS6 protein, thus negatively regulating the accumulation of AtACS6[56].

Type II ACS isozymes possess targeting sites for CDPKs and E3 ligases, including Arabidopsis AtACS4, AtACS5, AtACS8, and AtACS9, tomato SlACS3, SlACS5, SlACS7, and SlACS8, as well as rice OsACS1[53,57]. These enzymes are recognized by ETHYLENE OVERPRODUCER 1 (ETO1) or ETO1-Like (EOL) due to their TOE motif, and subsequently targeted for ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation[58−60]. Casein kinase 1.8 (Ck1.8) negatively regulates the protein stability of AtACS5 via phosphorylation, demonstrating that phosphorylation of ACS does not always promote the accumulation of ACS proteins. Additionally, the phosphorylation of AtACS5 by CK1.8 strengthens the interaction between AtACS5 and ETO1, thereby further promoting the degradation of AtACS5[61]. Instead, 14-3-3 elevates the stability of AtACS5 via direct interaction, simultaneously enhancing the turnover of ETO1/EOL, thereby protecting AtACS5 from degradation and ultimately affecting the ethylene biosynthesis[62].

For type III ACS, no specific motifs have been found so far, including Arabidopsis AtACS7, tomato SlACS4, rice OsACS3, OsACS4, and OsACS5. It is reported that this type of ACS isoenzyme engages in interaction with a RING-type E3 ligase XBAT32, leading to degradation via the ubiquitination pathway[63]. Recent research has revealed that K285 and K366 serve as the primary ubiquitination sites for AtACS7 in Arabidopsis seedlings, as mutations of these residues to arginine notably impair the proteasome degradation of AtACS7[64]. Nevertheless, further validation is required to determine whether K285 or K366 are the specific target sites of XBAT32. Furthermore, the mutations introduced at K285 and K366 have failed to completely halt the degradation of AtACS7, suggesting the possibility of other ubiquitin-modified residues or alternative degradation pathways being involved in the regulation of AtACS7. Additionally, it has been discovered that the group A PP2Cs family, including ABI1, ABI2, and HAB1, interacts with AtACS7 to modulate its turnover, though the underlying mechanism remains to be elucidated[65].

Moreover, various hormones such as cytokinins, brassinosteroids, abscisic acid, gibberellic acid, methyl jasmonic acid, and salicylic acid exhibit diverse regulatory effects on the stability of ACS proteins[66,67]. Studies have demonstrated that cytokinins, brassinosteroids, and gibberellic acid promote the accumulation of type I AtACS2 in Arabidopsis seedlings. Furthermore, cytokinins and brassinosteroids enhance the steady-state levels of type II AtACS5 protein in a time-dependent manner[54,59]. The stability of AtACS5 protein also shows a significant increase after 2 h of treatment with abscisic acid, gibberellic acid, methyl jasmonic acid, and salicylic acid[60]. Notably, cytokinin treatment enhances the stability of the myc-AtACS5eto2 protein in myc-AtACS5eto2 transgenic plants. Additionally, treating eto2 etiolated seedlings with cytokinins leads to an increase in ethylene production, albeit to a lesser extent compared to wild-type seedlings[54,59]. Therefore, the regulation of ACS protein stability by cytokinins may be partially independent of the C-terminal domain. Intriguingly, unlike type I and type II ACS, the steady-state levels of type III myc-AtACS7 remain unaffected by any of these plant hormones[60]. In conclusion, the stability of ACS proteins is regulated by the complex interplay of various plant hormones, and the specific regulatory mechanisms underlying these effects still require further exploration.

Other mechanisms in regulating ACS

-

In addition to transcriptional and post-translational regulation, different ACS isoenzymes can form homodimers or heterodimers, which have been demonstrated to influence both enzyme activity and stability[68]. Not all heterodimers formed by ACS possess catalytic activity. Interestingly, intermolecular complementation experiments in E. coli revealed that only those heterodimers formed by members of the same phylogenetic branch of the gene family exhibited functionality[69]. However, AtACS7 of type III is an exception, which can form functional heterodimers with members of the other two branches[69]. This functional heterodimerization not only enhances the isoenzyme diversity of the ACS gene family but also improves the stability of the shorter-lived partner within the heterodimer, thereby playing a more effective regulatory role in the plant lifecycle[67].

For chemical control, aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG), and 2-aminooxyacetic acid (AOA) are the effective inhibitors of ACS. AVG, owing to its structural similarity to SAM, effectively prevents the binding of apple ACS to its substrate[70,71]. The inhibitory mechanism of AOA is speculated to involve its interaction with ACS or irreversible binding to the PLP cofactor, thus reducing the production of ACC[71]. AVG has been commercialized in agriculture, inhibiting the abscission of flowers and fruits while delaying fruit ripening[72,73]. Nevertheless, AVG inhibitors possess a limitation in their lack of specificity, resulting in the potential for unintended inhibition of other PLP-dependent enzymes[74]. Consequently, the further development and application of inhibitors specifically designed to target and inhibit ACS will enable a more refined control over ethylene production, ultimately enhancing the overall quality of agricultural products.

-

When all members of the ACS family in Arabidopsis are simultaneously knocked out, it results in embryonic lethality, clearly demonstrating the indispensability of ethylene for plant survival[75]. By obtaining single and higher-order mutants of ACS, researchers have uncovered that ACS members have unique but overlapping functions throughout the plant lifecycle, encompassing plant growth, flowering, senescence, and stress resistance[75]. The representative roles of ACS in plant life are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. The roles of ACS in plant life.

Biological process Species Gene Function Ref. Vegetative growth Arabidopsis ACS2 Development of lateral root [76] ACS5 Elongation of the hypocotyl [77] ACS7 Development of plant height [78] ACS1 Leaf senescence [80] Citrus ACS4 Development of plant height [22] Maize ACS7 Development of plant height [79] Maize ACS2, ACS6 Leaf senescence [81] Sex determination and flowering Cucumber ACS7 Sex differentiation [83] ACS11 Female flower development [84] Melon ACS2 Sex differentiation [82] ACS11 Female flower development [82,84] Watermelon ACS4 Formation of hermaphroditic flowers [85] Pineapple ACS2 Flowering [86] Oncidium ACS12 Flowering [87] Fruit ripening Apple ACS1 Fruit ripening [89] Citrus ACS Fruit ripening [90] Melon ACS Fruit ripening [92] Tomato ACS2 Fruit ripening [93,94,95] ACS4 Fruit ripening [93,95] Stress response Arabidopsis ACS6, ACS7, ACS8, ACS10, ACS11, ACS12 High temperature stress [97] ACS2, ACS6 Drought [102] ACS11 Boron deficiency [104] ACS2, ACS6, ACS7 Pathogen resistance [107] Rice ACS2, ACS5 High temperature stress [97] ACS1, ACS2 Cr-stress [99] ACS1, ACS5 Flooding [103] ACS1, ACS2 Phosphate deficiency [105] ACS1, ACS2 Pathogen resistance [107,108] Cotton ACS12 High-salt stress [100] Role in plant vegetative growth

-

Recent studies have reported that ACS is extensively involved in the vegetative growth of plants. Overexpression of AtACS2 in Arabidopsis significantly reduced the number of lateral roots[76]. As Arabidopsis seedlings transition from darkness to light, the exposure to light stabilizes the AtACS5 protein, preventing its degradation and consequently enhancing ethylene synthesis, which ultimately facilitates transient elongation of the hypocotyl[77]. Ethylene is closely associated with the division of cambium cells and the development of cell walls. Yang et al. identified an ethylene overproduction mutant, acs7-d, which exhibits defects in cell wall development, leading to dwarfism in the plant[78]. The overexpression of the citrus CiACS4 gene in tobacco and lemon plants leads to a significant elevation in ethylene production, thereby inhibiting gibberellin synthesis and resulting in a notable suppression of plant height growth[22]. The mutation of the ZmACS7 gene in maize causes a marked decrease in plant height and an enlargement in leaf angle, while also exerting a notable influence on root development, flowering time, and the number of leaves[79]. The functional deficiency of AtACS1 in Arabidopsis leads to a diminished accumulation of ACC, consequently reducing chlorophyll loss in leaves and subsequently delaying the process of leaf senescence[80]. The loss of ZmACS2 and ZmACS6 in maize significantly reduced ethylene levels in leaves by 45% and 90% respectively, resulting in leaves sustaining photosynthesis for an extended period and experiencing a substantial delay in senescence[81].

Role in plant sex determination and flowering

-

The ACS gene holds a pivotal role in sex determination and flower development in some vegetable crops. The homologous genes CmACS7 in cucumber, and CsACS2 in melon significantly influence sex differentiation by regulating flower development[82,83]. The orthologous genes CsACS11 and CmACS11 control female flower development and mutation in cucumber and melon, respectively, leading to male infertility[82,84]. Specifically, CitACS4 in watermelon is expressed in the carpel primordia, and the C364W mutation of CitACS4 leads to a decrease in enzyme activity, which results in the formation of hermaphroditic flowers[85]. Early research indicated that minute quantities of ethylene could induce flowering in meristematic tissues. Correspondingly, pineapple AcACS2 is specifically activated in meristematic tissues, facilitating the flowering process[86]. However, excessive ethylene production may also inhibit flowering. In Arabidopsis, ectopic expression of OnACS12 from the Oncidium hybridum is found to result in late flowering and anther indehiscence by affecting the biosynthesis and signal transduction pathways of GA[87]. In addition, following pollination, ACS transiently overexpressed, regulating the senescence of flowers[88]. Notably, reducing the expression of ACS genes significantly decreases ethylene production, thereby effectively delaying flower senescence.

Role in plant fruit ripening

-

The ACS gene family also plays a crucial role in fruit ripening and postharvest storage. Specifically, the apple MdACS1 is highly expressed during fruit ripening and is responsible for the production of ethylene in system 2, while the expression patterns of citrus ACS genes undergo remarkable changes throughout the post-harvest storage[89,90]. In the transcriptome profiling of pear fruits during post-harvest ripening, the expression pattern of ACS genes displays a notable correlation with the process of ripening[91]. The application of NO effectively delayed the ripening of bitter melon fruits, accompanied by significant changes in the expression of ACS genes, indicating that ACS plays a vital role in the ripening process[92]. The study found that the increased expression of SlACS2 and SlACS4 and enzyme doses in tomato significantly promoted the production of ethylene. These genes play a pivotal role in the autocatalytic ethylene production process of system 2[93]. Early research into tomato revealed that silencing SlACS2 and SlACS4 led to a drastic decrease in fruit ethylene production, dropping to merely 0.1% of the wild-type level, which subsequently inhibited the normal ripening process[93]. This demonstrates that SlACS2 and SlACS4 play a crucial role together in ethylene synthesis and fruit ripening. Subsequent studies only observed a moderate reduction in ethylene synthesis in fruits after the mutation of SlACS2[94]. Currently, it is believed that SlACS4 primarily triggers system 2 ethylene synthesis, subsequently prompting the expression of SlACS2 to initiate the ethylene autocatalytic process[95]. Nevertheless, this theory still lacks further experimental evidence. Consequently, further exploration is still needed into the fine regulatory mechanisms of ACS family members in the ethylene biosynthesis process of system 2 in climacteric fruits.

Role in plant stress response

-

ACS plays multiple roles in plants response to environmental stimuli. To cope with abiotic or biotic stresses, including injury, heat, heavy metal, and pathogen invasion, ACS actively responds to environmental signals by boosting ethylene production. This elevated ethylene level is then detected by ethylene receptors, ultimately triggering defense responses via the ethylene signaling pathway[96]. Comprehensive transcriptome analyses have revealed that AtACS6, AtACS7, AtACS8, AtACS10, AtACS11, and AtACS12 in Arabidopsis, along with OsACS2 and OsACS6 in rice, exhibit marked upregulation under high temperature stress[97,98]. Furthermore, the expressions of OsACS1, OsACS2, OsACO4, and OsACO5 in roots subjected to chromium (Cr) treatment are enhanced[99]. Notably, GhACS1 and GhACS12 in cotton demonstrate significant upregulation in both short- and long-term exposure to high-salt environments[100]. Besides, research has shown that ACC can be used to promote stomatal development in plant leaves, and the endogenous level of ACC depends on the activity of members of the ACS family[101]. Overexpression lines of AtACS2 and AtACS6 increase stomatal density and clustering rate on the leaf epidermis of Arabidopsis by accumulating ACC, and elevate the risk of seedling mortality under exacerbated drought conditions[102]. The expressions of OsACS1 and OsACS5 in rice undergo a notable upregulation in response to hypoxic conditions induced by flooding[103]. When suffering from boron deficiency, the expression of AtACS11 is upregulated to facilitate the increase in ethylene levels, subsequently limiting the elongation of root cells[104]. Similarly, in response to phosphate (Pi) deficiency, rice OsACS1 and OsACS2 demonstrate adaptive reactions mediated by ethylene, which are instrumental in root development[105].

In the context of defending against pathogen invasion, AtACS2, AtACS6, and AtACS7 serve as the key members in enhancing ethylene production in Arabidopsis following infection by fungal pathogens, such as Botrytis cinerea, or bacterial pathogens, like Pseudomonas syringae[106].OsACS1 and OsACS2 are induced following infection by the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae[107]. Overexpression of OsACS2 enhances the levels of pathogen-induced ethylene and defense gene transcripts, as well as resistance to necrotrophic and hemibiotrophic fungal pathogens[108]. In addition, the transcripts of OsACS2 are rapidly upregulated under mechanical injury and infestation by the striped stem borer and brown planthopper, indicating that OsACS2 is involved in pathogen resistance through the regulation of ethylene synthesis[109].

-

Despite the recent identification of the ACS family in numerous plant species and the rapid increase in research exploring their vital roles in plant growth, development, and stress response, our comprehension of the specific regulatory mechanisms of ACS in plant cells remains inadequate. Over the past few years, we have extensively reported on transcription factors that regulate ACS at the mRNA level, as well as complex post-translational regulation controlling ACS protein turnover, and the regulatory roles of protein heterodimers and hormonal factors. However, despite this progress, numerous questions remain unanswered. Are there developmental signals that precisely regulate ACS transcription in plants, and what is the impact of ACS heterodimers on protein turnover and their contribution to enzyme activity? Additionally, the factors that can optimize the enzyme activity of ACS in plants remain elusive. The collaborative regulation mechanisms among different members of the ACS family throughout the plant lifecycle require further exploration. Interestingly, recent studies have uncovered a Cβ-S lyase activity in ACS, but the biological significance and regulatory mechanisms of this activity are almost unknown. Furthermore, whether the Cβ-S lyase activity of ACS is independent or interconnected with its ACC-synthesizing activity demands further investigation. These questions, as promising directions for future research, have the potential to provide novel and exciting insights into the profound significance of ACS in plant life.

This work was supported by grants to Zhu H from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172639).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li J, Zhu H; data collection: Li J, Cheng K, Lu Y, Wen H, Ma L, Zhang C, Suprun AR; draft manuscript preparation: Li J. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li J, Cheng K, Lu Y, Wen H, Ma L, et al. 2025. Regulation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase (ACS) expression and its functions in plant life. Plant Hormones 1: e002 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0002

Regulation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase (ACS) expression and its functions in plant life

- Received: 18 December 2024

- Revised: 13 January 2025

- Accepted: 14 January 2025

- Published online: 24 January 2025

Abstract: Ethylene is a unique plant hormone and plays an important role throughout the entire life cycle of plants. The biosynthetic pathway of ethylene is relatively simple. Under the catalysis of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) synthase (ACS), S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) is transformed into ACC and 5'-methylthioribose (MTA), and subsequently, ACC oxidase (ACO) converts ACC into ethylene. Notably, ACS is the rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of ethylene. Recent molecular and genetic investigations have revealed that ACS undergoes intricate multi-level regulation, encompassing transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms, to maintain the balance of ethylene production, thus facilitating normal plant growth and resilience to environmental stress. This review will discuss the multi-faceted regulatory mechanisms of ACS at the molecular level and explore the pivotal contributions of ACS family members in plant growth, development, and stress response, based on recent research.